- 1Key Laboratory of Ecological Adaptive Evolution and Conservation on Animals-Plants in Southwest Mountain Ecosystem of Yunnan Province Higher Institutes College, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, China

- 2School of Life Sciences, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, China

- 3Key Laboratory of Yunnan Province for Biomass Energy and Environment Biotechnology, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, China

Introduction: To investigate the capacity of Tupaia belangeri to withstand high-temperature environments and its adaptability to global warming trends, while examining evidence for the species’ tropical origins through thermal neutral zone analysis.

Methods: This study subjected T. belangeri, a representative mammal of the Oriental realm, to a temperature of 35 °C for 28 days to induce thermal acclimation. Body temperature (Tb) and basal metabolic rate (BMR) were measured at ambient temperatures (Ta) of 20 °C, 25 °C, 30 °C, 32.5 °C, 35 °C, and 37.5 °C, with thermal conductance (C) subsequently calculated. Latitudinal distributions and thermal neutral zone (TNZ) of 90 small mammals were compared against both normal-temperature and high-temperature acclimated T. belangeri.

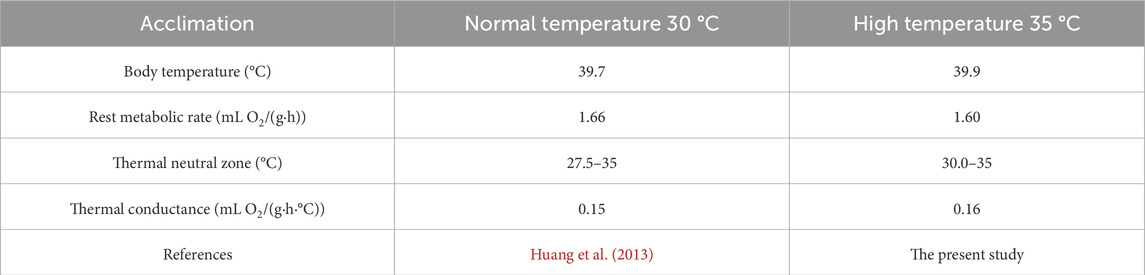

Results: Results indicated that Tb increased with rising ambient temperature, averaging 39.9 °C ± 0.16 °C within the TNZ. BMR showed no significant difference within the 30 °C–35 °C range. The mean BMR was 1.60 ± 0.025 mL O2/(g·h), indicating TNZ convergence at 30 °C–35 °C under high-temperature conditions. The mean C values within this range were 0.16 ± 0.0052mL O2/(g·h· °C). Compared to previous data on normal-temperature acclimation from our laboratory, high-temperature acclimated animals exhibited elevated Tb, reduced BMR, a narrowed TNZ with an increased lower thermal neutral zone (LTNZ), and heightened C values. The TNZ of both acclimation groups in within the tropical high-temperature ranges.

Discussion: These findings collectively indicated that T. belangeri adapts to thermal stress through increased Tb, reduced metabolic rate, enhanced heat dissipation capacity, and a shift of the TNZ towards higher temperatures. Additionally, the TNZ of T. belangeri exhibited minimal fluctuations when subjected to high-temperature stress, indicating a strong adaptive capacity to warmer environments. Furthermore, the TNZ of T. belangeri is situated within the tropical high-temperature range, providing physiological evidence of its tropical origin based on the characteristics of the TNZ.

1 Introduction

Global warming has resulted in an increase in the frequency of high-temperature events, posing significant challenges to the survival and adaptability of several animal species. Research indicates an approximate 1.1 °C rise in mean global surface temperature over the past 50 years, with projections suggesting an additional increase of 1.5 °C–4.5 °C by the end of the century (Zhao et al., 2024). This rapid climatic shift compels small mammals to maintain energy balance and thermal stability through adjustments in thermoregulation, heat production capacity, or habitat selection (Chen et al., 2022). Environmental temperature profoundly influences both the physiological and morphological characteristics of small mammals, simultaneously regulating their energy management (Bi et al., 2018). In response to changes in environmental temperature, different taxa employ distinct adaptive strategies to cope with environmental fluctuations and ensure their survival (Hua et al., 2010). Notably, under conditions of high-temperature acclimation, Cricetulus barabensis increases its body mass (Zhang et al., 2025), while CD-1 mice exhibit a reduction in mass following thermal exposure (Bridges et al., 2012).

As a fundamental research area within physiological ecology, thermoregulation elucidates the critical relationship between environmental temperature and body temperature in small mammals. Research indicates that organisms exchange energy with their environment through several heat transfer mechanisms, including radiation, conduction, convection, and evaporation (Adam et al., 2017). For small mammals, the ability to maintain a consistently high body temperature is a key determinant of their survival range and geographical distribution (Zhu et al., 2008). For example, exposure to cold induces the proliferation of brown adipose tissue (BAT) in Lasiopodomys brandtii, enhancing thermogenic capacity through the activation of uncoupling protein (UCP), which increase energy expenditure during cold stress (Hou et al., 1999). Conversely, in response to thermal challenges, mammals typically maintain heat balance by reducing metabolic rates, enhancing heat dissipation efficiency, or employing behavioral adaptations. Desert rodents exemplify this strategy through nocturnal locomotion and reduced activity to minimize heat accumulation (Salaün et al., 2024). Additionally, Meriones unguiculatus significantly lowers its body temperature below control levels by actively suppressing metabolic heat production, thereby reducing both energy expenditure and water loss (Guo et al., 2020).

Basal metabolic rate (BMR) represents the energy expenditure required to sustain basic life functions in mammals and serves as a critical indicator of their capacity for environmental adaptation. Importantly, BMR levels are regulated by the thermal neutral zone (TNZ) (Feng et al., 2022), that is defined as the range of environmental temperatures within which mammals can maintain their body temperature without incurring additional energy costs. The width of the TNZ reflects the species’ ability to adapt to temperature. When environmental temperatures exceed the boundaries of the TNZ, mammals must engage in behavioral or physiological thermoregulation to maintain homeostasis (McAllister et al., 2009). Thermal conductance (C), a principal determinant of heat exchange between animals and their environment, is influenced by morphological factors such as body conformation, pelage density, and circulatory efficiency. These factors constitute a key component of energetic expenditure (Naya et al., 2013). For example, Ochotona curzoniae, which inhabits high-altitude environments, achieves enhanced thermal insulation through reduced C values (Zhu et al., 2022).

Tupaia belangeri, a small mammal endemic to the Oriental realm and belonging to the family Tupaiidae within the order Scandentia, primarily inhabits warm, humid broadleaf forests and mixed coniferous-broadleaf ecosystems. Its distribution encompasses Southeast Asia, India, Nepal, and Myanmar, with populations in China concentrated in Yunnan, southwestern Sichuan, southwestern Guizhou, southern Guangxi, and Hainan Island. Yunnan, Sichuan, and Guizhou represent the northern limits of this species’ distribution; it is hypothesized that this limitation is linked to its tropical origin and limited adaptability to low-temperature environments (Bremer et al., 2011). Previous research has demonstrated that Tupaia belangeri, which has expanded into the Hengduan Mountains, exhibits physiological adaptability by combining transitional traits of tropical animals with specific adaptations to the region. For example, low temperatures increase its metabolic rate; however, the extent of non-shivering thermogenesis enhancement diminishes with prolonged cold acclimation, which contrasts with the adaptations observed in northern small mammals (Zhang et al., 2012). Furthermore, its weight regulation differs from that of sympatric rodent species: under winter or cold conditions, it gains weight through a unique adaptive strategy (Feng et al., 2022). However, given the accelerating global warming and rising temperatures, a critical question arises: can T. belangeri, a species of tropical origin, adapt to thermal stress within its colonized habitat in the Hengduan Mountains? This adaptive capacity fundamentally depends on thermoregulatory competence and the efficacy of body mass regulation. Currently, no conclusive evidence exists regarding the precise mechanisms or extent of high-temperature adaptation in this species. Consequently, this study investigated T. belangeri specimens from Tuanjie Village, Kunming, analyzing changes in Tb, BMR and C values under high-temperature acclimation conditions. Through a comparative assessment of TNZ dynamics, we examined the coping mechanisms and adaptive capacity of this species in high-temperature environments under global warming scenarios, while also verifying the possibility of its tropical origin from the perspective of TNZ. We predict that heat-stressed T. belangeri will exhibit: elevated Tb, reduced BMR, a migration of TNZ towards higher temperature ranges, and increased C, which can provide evidence supporting the tropical origin of T. belangeri in terms of thermal neutrality.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Animal collection

Experimental T. belangeri specimens were captured in Tuanjie Village, Kunming (average temperature: 14.9 °C; coordinates: 102°10′–102°40′E, 24°23′–25°03′N; terrain: north-high, south-low; altitude: 2,202 m) using rat cages. Following disinfection and defleaing, the animals were transported to the animal facility at Yunnan Normal University for individual housing under controlled conditions (temperature: 30 °C ± 1 °C; photoperiod: 12L: 12D). The subjects were provided ad libitum access to standardized feed (from Kunming Medical University) and water. All specimens were adults in a non-reproductive phase. Based on previous research indicating that the TNZ of T. belangeri spans 27.5 °C–35.0 °C; therefore, The acclimation temperature for high-temperature exposure in this study was set to 35 °C. Animals (n = 42, ♀:♂ = 18:24) underwent a 28-day acclimation period at 35 °C with a 12L:12D photoperiod. Post-acclimation measurements included Tb, RMR, and calculated C values. All procedures complied with the regulations of the Medical Bioethics Committee of Yunnan Normal University (ethical approval: 13-0901-011).

2.2 Latitudinal coordinates and TNZ data sourcing for small mammals

The dataset for this study, which focuses on small mammals and T. belangeri, includes latitudinal coordinates and thermal neutral zones for species ranging from tropical to temperate environments, as detailed in Table 1. The dataset comprises a total of 91 species, spanning from Gerbillus pusillus, which has the lowest latitudinal coordinates, to Sorex minutus, which has the highest latitudinal coordinates.

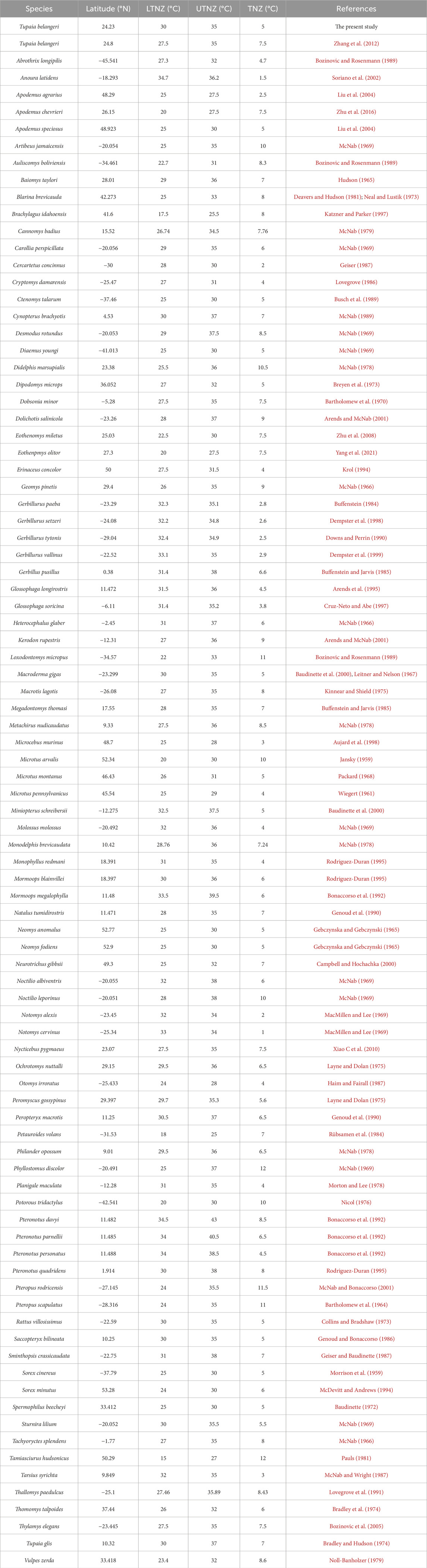

Table 1. Latitudinal coordinates and thermal neutral zones of small mammals and Tupaia belangeri across different latitudinal regions.

2.3 Determination of Tb, BMR and C values

Body mass, Tb, and BMR were measured in seven specimens across ambient temperatures of 20 °C, 25 °C, 30 °C, 32.5 °C, 35 °C, and 37.5 °C. Mass determination was conducted using an analytical balance (AB204-S, Mettler Toledo, Switzerland; accuracy ±0.01 g). Body temperature was recorded after each metabolic rate test at each temperature. Rectal temperature of animals was measured, using a digital thermometer (XGN-1000T, Beijing Yezhiheng Technology Co. Ltd.; accuracy ±0.1 °C). The probe of the thermometer was inserted 3 cm into the rectum and a reading was taken after 30 s. BMR measurements utilized a small-mammal metabolic system (PRO-MRMR-8, Able Systems International Inc.). Following a fasting period of 2–4 h, the animals were placed in metabolic chambers with an airflow rate of 2 L/min under thermoneutral conditions. After more than 30 min of acclimation to a resting state, data were recorded at 5-min intervals for a duration of 60 min (Zhu et al., 2008). Post-experiment, two consecutive stable minimum values were selected for RMR calculation. The C value was derived using McNab’s equation: C = BMR/(Tb - Ta) (McNab, 2009), where Tb denotes body temperature and Ta denotes ambient temperature.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS v26.0 software package. Prior to all statistical analyses, the data were tested for normality and homogeneity of variance using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Levene tests, respectively. Differences between sexes for the physiological indices of T. belangeri were not significant; therefore, all data were combined and analyzed collectively. Tb was assessed using a one-way ANOVA, while RMR and C values were analyzed using ANCOVA, with body mass as a covariate. A linear regression was employed to model the correlation between TNZ and latitudinal coordinates, as well as the relationships between Ta and Tb, RMR, and C values. Results was expressed as mean ± standard error (SE), with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Body temperature

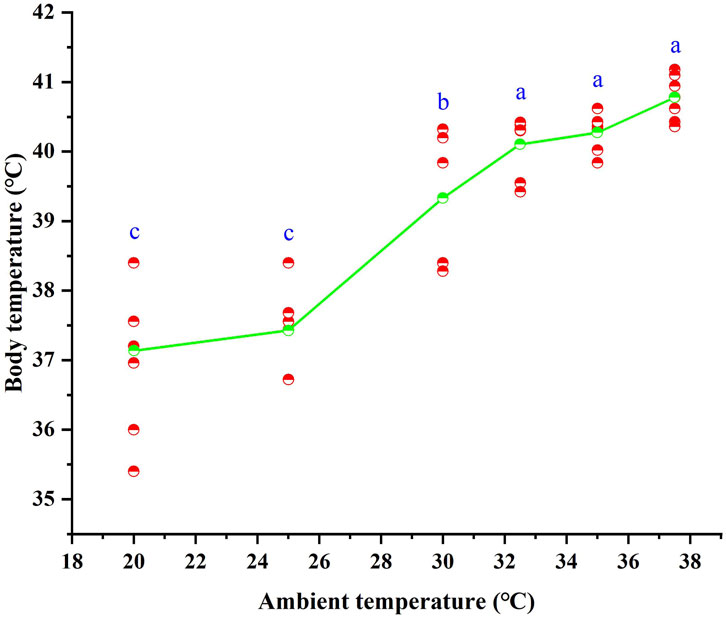

Following 28 days of high-temperature acclimation, the Tb of T. belangeri ranged from 35.4 °C to 41.18 °C. An ANOVA revealed significant positive correlation between Tb of T. belangeri and the ambient temperature ranging from 20 °C to 37.5 °C. Tb increased with rising ambient temperature, and the linear regression equation relating Tb to Ta was expressed as Tb = 32.259 + 0.23*Ta (R2 = 0.789, F = 149.852, p < 0.01), (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Body temperature of Tupaia belangeri at varying ambient temperatures. Different letters (a, b and c) indicate statistically significant differences in body temperature data between groups (p < 0.05), and the same letter represents no significant difference; the scatter points are individual measured values, and the green line show the mean fitted trend.

3.2 Resting metabolic rate (RMR) and TNZ

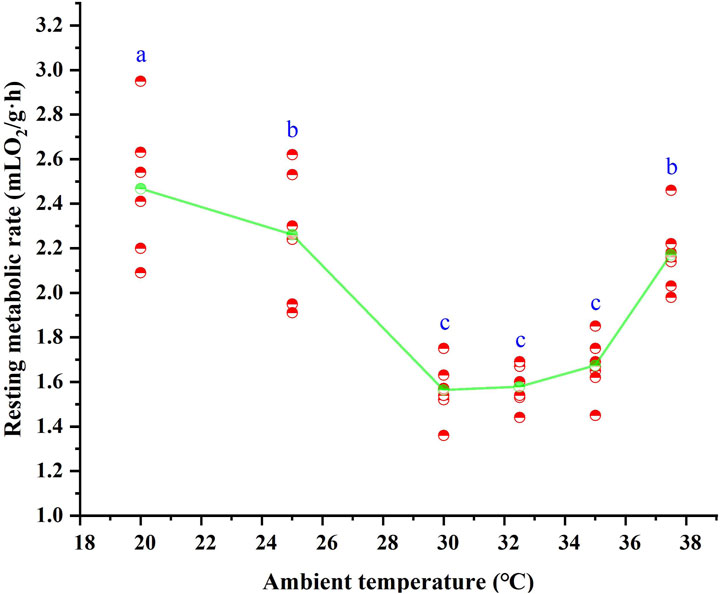

Following 28 days of high-temperature acclimation, the RMR of T. belangeri showed a highly significant variation in response to ambient temperature (F = 31.848, p < 0.01). RMR increased as ambient temperature decreased below 30 °C (Figure 2), revealing a linear relationship with temperature. The regression equation for RMR as a function of ambient temperature in the 20 °C–30 °C range was RMR = 4.349–0.09*Ta (r2 = 0.692, F = 42.673, p < 0.01). Above 35 °C, RMR also increased with rising temperature (Figure 2), with a linear regression described by RMR = −5.291 + 0.199*Ta (r2 = 0.789, F = 44.974, p < 0.01) across the 35 °C–35.7 °C range. ANOVA revealed that RMR remained stable between 30 °C and 35 °C (F = 2.058, p > 0.05), representing the BMR with a mean of 1.60 ± 0.025 mL O2/(g·h). This value differed significantly from RMR at 25 °C and 37.5 °C (p < 0.05), defining the thermal neutral zone (TNZ) as 30 °C–35 °C. The mean body temperature within the TNZ was 39.9 °C ± 0.16 °C.

Figure 2. Resting metabolic rate of Tupaia belangeri at varying ambient temperatures. Different letters (a, b and c) indicate statistically significant differences in resting metabolic rate data between groups (p < 0.05), and the same letter represents no significant difference; the scatter points are individual measured values, and the green line show the mean fitted trend.

3.3 C values

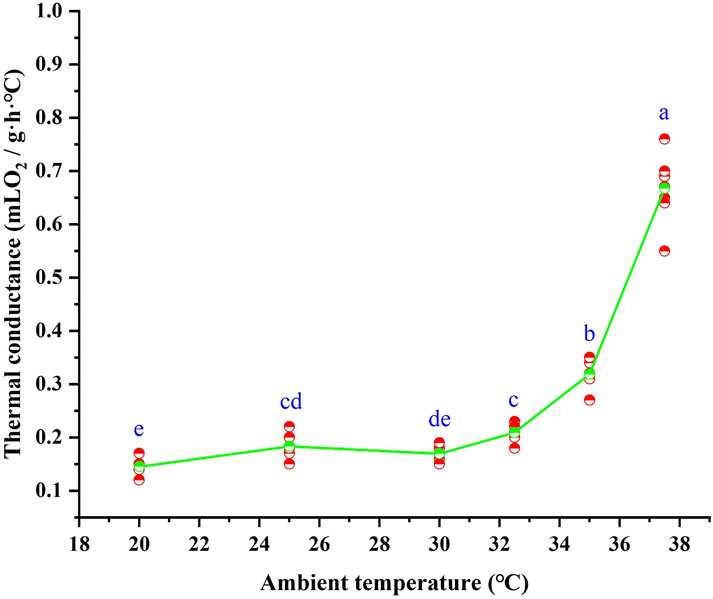

Following 28 days of high-temperature acclimation, the C values of T. belangeri varied significantly with ambient temperature (F = 279.642, p < 0.01). The C values were lowest below the LTNZ, where they remained relatively stable. Within the TNZ, C values increased with rising ambient temperature, averaging 0.16 ± 0.0052 mL O2/(g·h· °C). This relationship was described by the linear regression equation C = −0.740 + 0.03*Ta (R2 = 0.866, F = 122.403, p < 0.01). Beyond the upper thermal neutral zone (UTNZ), C values increased sharply with further elevation in ambient temperature (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Thermal conductance of Tupaia belangeri at varying ambient temperatures. Different letters (a, b, c, d and e) indicate statistically significant differences in thermal conductance data between groups (p < 0.05), and the same letter represents no significant difference; the scatter points are individual measured values, and the green line show the mean fitted trend.

3.4 Relationship between TNZ and latitude coordinates

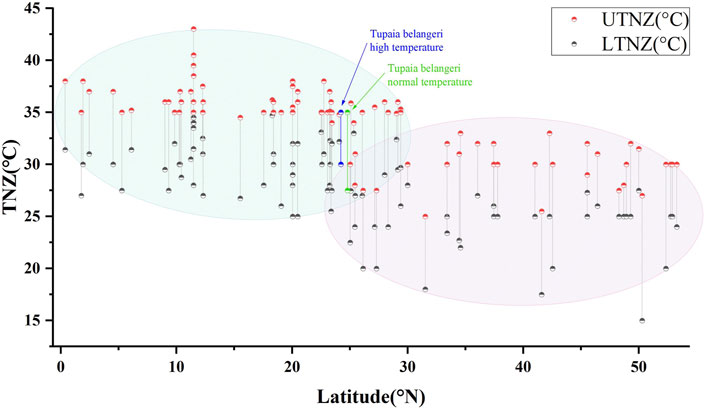

Comparative analysis of thermal neutral zones for the 91 small mammal species along latitudinal gradients, including TNZ data for T. belangeri under normothermic and high temperature acclimation conditions, revealed significant correlations between latitudinal distribution and TNZ boundaries. The LTNZ of small mammals exhibited a strong correlation with latitude (R2 = 0.365, F = 51.78, p < 0.01), as did the UTNZ (R2 = 0.537, F = 104.398, p < 0.01). Collectively, these findings show that small mammal thermal neutral zones are significantly dependent on latitude, with low-latitude species displaying higher TNZ ranges than their high-latitude counterparts (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Relationship between the TNZ and latitudinal coordinates in Tupaia belangeri and 90 small mammal species.

4 Discussion

Faced with environmental changes, animals maintain energy homeostasis by modulating physiological and ecological traits (Stawski and Simmonds, 2021). Body temperature is central to energy regulation and serves as a key physiological marker in animal energetics research (Ayres, 2020). For instance, rats adapted to extreme cold actively reduce their body temperature to minimize heat production at −30 °C (Yin et al., 2009), while Phodopus roborovskii elevates its body temperature through increased non-shivering thermogenesis in cold environments (Bao et al., 2001). Previous studies have shown that T. belangeri regulates energy by lowering its body temperature under cold stress (Zhang et al., 2001). In our study, the body temperature of T. belangeri increased with ambient temperature (20 °C–37.5 °C) following high-temperature acclimation (Figure 4), consistent with findings in Tupaia glis (Bradly et al., 1974) and Crocidura suaveolens (Wang et al., 2010). This would that species within the family Tupaiidae exhibit common physiological characteristics and unique body temperature regulation patterns in response to varying ambient temperatures. Additionally, the body temperature of T. belangeri was lower at normothermia (39.7 °C) compared to after high-temperature acclimation (39.9 °C) (Table 2). This pattern is supported by findings in blackline hamsters (Zhao et al., 2018) and long-clawed gerbils (Guo et al., 2020), where thermal acclimation leads to an elevation in body temperature. Interestingly, this contrasts with the response of desert rodents like Gerbillus pusillus, which maintain lower body temperatures to minimize water loss (Buffenstein and Jarvis, 1985). These findings corroborate the results of our study and suggest that such physiological adjustments may represent an adaptive mechanism for high-temperature environments. By moderately increasing body temperature, animals can reduce their resting metabolic rate while enhancing thermal conductance, thereby decreasing the energy expenditure required to maintain a constant internal temperature and optimizing energy allocation. Furthermore, a suitable rise in body temperature can minimize the thermal gradient between the body and the external environment, effectively promoting heat dissipation and reducing heat production (Vejmělka et al., 2021). This strategy facilitates a balance between heat production and dissipation, thus preventing metabolic overload under high-temperature stress. Our results indicate that T. belangeri enhances heat dissipation by elevating body temperature to maintain thermal equilibrium. This adaptive response may represent an evolutionary strategy for coping with prolonged exposure to high-temperature conditions.

Table 2. Physiological indices of Tupaia belangeri under normal temperature and high-temperature acclimation.

RMR serves as a crucial indicator of energy expenditure in animals, influenced by several factors including temperature, food availability, and activity levels (such as exercise, reproductive behaviors, and stress responses) (Terblanche et al., 2007; Rising et al., 2015). Importantly, RMR plays a pivotal role in processes of environmental adaptation (Feierabend and Kielland, 2015). Research shows that cold-exposed C. barabensis exhibit elevated RMR and non-shivering thermogenesis compared to controls maintained at normal temperatures (Chen et al., 2014). Similarly, high-altitude Lberomys cabrerae maintain stable body temperatures through increased RMR (Castellanos-Frias et al., 2015), while cold-acclimated P. roborovskii show enhanced RMR and non-shivering thermogenesis capacity (Chi and Wang, 2011). Our findings indicate that T. belangeri, when exposed to thermal acclimation, exhibited a reduced RMR compared to laboratory measurements taken at normal temperatures. This pattern mirrors those observed in high-temperature-acclimated rodents from the Hengduan Mountains region, that include to Eothenomys miletus, Eothenpmys olitor, and Apodemus chevrieri (Geng and Zhu, 2024), suggesting a convergent evolutionary adaptation. In contrast, temperate rodents like Microtus arvalis often increase RMR under thermal stress to sustain thermogenesis (Jansky, 1959). The observed reduction in RMR likely represents an adaptive response to thermal stress, serving as a crucial strategy for minimizing heat production in warmer environments (Speers-Roesch et al., 2018). For T. belangeri, lower metabolic rates would help to prevent overheating while facilitating energy reallocation to essential functions such as foraging and reproduction. Additionally, reduced energy expenditure allows animals to maintain lower basal metabolic costs, thereby decreasing the time required for foraging. This adaptive strategy provides dual survival benefits by simultaneously reducing the risk of predation and offering a survival advantage during periods of food scarcity (Mónus and Barta, 2016; Shiratsuru et al., 2021). Tupaia belangeri exhibited an efficient energy adaptation strategy in response to warmer environmental by lowering its energy consumption. This approach reflects a highly effective mechanism for coping with climate change.

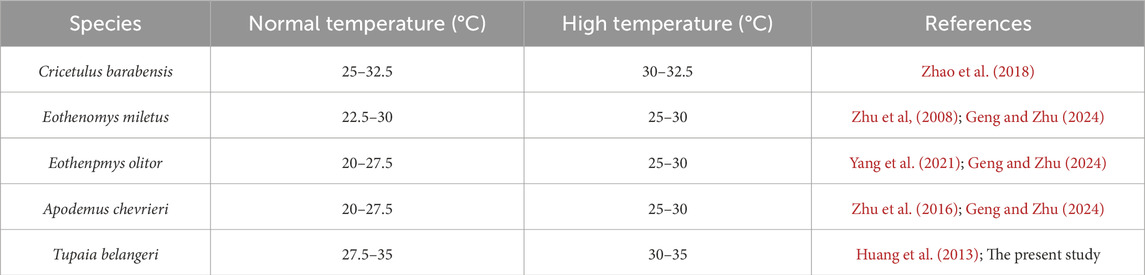

TNZ is a specific range of ambient temperatures within which animals maintain thermoregulation by regulating heat loss, without relying on metabolic heat production or evaporative heat dissipation (Kingma et al., 2014). Although multiple factors influence the TNZ, environmental temperature is a critical determinant (Yang et al., 2021). For the same species, the TNZ shifts with changes in environmental temperature: LTNZ decreases and the width of the TNZ increases in cold environments, whereas the LTNZ rises and the TNZ narrows in warm environments (Zhu et al., 2016). For instance, the species Dipus sagitta exhibits a narrow TNZ around 30 °C in spring, the widest TNZ and highest heat resistance in summer, and a gradual shift to lower temperatures in autumn (Bao et al., 2000). Across species, the TNZ correlates with altitude, temperature, and other environmental factors (Zhu et al., 2022). Our study shows that T. belangeri has a TNZ of 30 °C–35 °C under moderate to high temperatures. Previous laboratory research on T. belangeri indicates that high-temperature acclimation narrows the TNZ by elevating the lower critical temperature while maintaining the upper critical temperature. The reduction in TNZ during heat exposure is partly attributed to a decreased metabolic rate (Zhao et al., 2010; Scholander et al., 1950). The upward shift in the critical temperature of the TNZ suggests that thermal acclimation enhances T. belangeri’s temperature tolerance to higher ranges, thereby reducing energy costs for thermoregulation in warmer environments, improving heat resistance, and increasing survival rates. For small mammals, adjusting the TNZ is a crucial strategy for adapting to climate change (Zhao et al., 2018).

By integrating findings from relevant high-temperature acclimation researches conducted in our laboratory on other five small mammal species, we observed that high-temperature acclimation resulted in a narrowing of the TNZ and an increase in the LTNZ across all five species (Table 3). This suggests that high-temperature exposure causes the TNZ to become more specialized in these animals. In comparison, we found that the change in TNZ width for T. belangeri was smaller than that of C. barabensis, indicating that T. belangeri exhibits greater adaptability to high temperatures than northern species. Furthermore, the temperature range of critical temperature drift within the TNZ of T. belangeri is limited, which further suggests that it possesses strong thermal adaptation and does not require significant adjustments to its physiological functions in response to thermal changes.

Table 3. Comparison of the thermal neutral zone in related species under normal temperature and high-temperature acclimation.

The origin and distribution patterns of T. belangeri remain subjects of ongoing debate; however, existing evidence supports a tropical-to-temperate dispersal trajectory (Roberts et al., 2011). Previous laboratory researches utilizing adaptive thermogenesis measurements and molecular ecological analyses have consistently indicated a south-to-north expansion pattern for this species, providing compelling support for its tropical origins (Fu et al., 2018; Jia et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2014). Our study compares the latitudes of regions inhabited by 90 small mammal species with the TNZ of T. belangeri under both normal and high-temperature acclimation. The findings reveal a correlation between TNZ and habitat latitude: high-latitude small mammals exhibit thermal neutral zones at higher temperature ranges than their low-latitude counterparts. Additionally, both the normal and high-temperature acclimated TNZ of T. belangeri is with the tropical high-temperature zones (Figure 2). The TNZ response to heat exposure reflects the species’ adaptive potential to extreme temperatures, which is crucial for determining whether it originated from tropical environments exposed to prolonged high-temperature stress (Wang et al., 2021). The TNZ of T. belangeri under heat exposure is still located in the tropical high temperature zone and the UTNZ remains unchanged, a characteristic feature of tropical species. This suggests that T. belangeri likely migrated from tropical areas to its current distribution, specifically from south to north, and may have developed adaptive physiological mechanisms to the high-temperature tropical environment over an extended evolutionary history. Its effective acclimation to high temperatures results as robust evidence for the likely tropical origin of T. belangeri.

Thermal conductance plays a pivotal role in the energy balance of small mammals, serving as one of the most critical factors influencing their energy expenditure (Naya et al., 2013). Environmental temperature profoundly affects thermal conductance: it decreases at low temperatures and increases at high temperatures, allowing animals to dissipate excess heat and maintain thermal stability along with a constant body temperature (Schmidt-Nielsen, 1997). For instance, Phodopus sungorus captured at low altitudes exhibit higher thermal conductance (Geiser et al., 2016). Small mammals struggle to adapt to fluctuating environmental temperatures by altering fur thickness, making adjustments in thermal conductance values essential (Yang et al., 2021). In our study, the C values remained relatively stable below the TNZ, while values above 30 °C increased with rising ambient temperatures. This thermal strategy reflects two possible adaptations: at lower temperatures, T. belangeri shows effective thermal insulation and heat dissipation blocking, which allows it to minimize energy expenditure for thermoregulation. However, in high-temperature environments, the reduced temperature difference between the body surface and the environment results in weaker heat dissipation capacity, preventing the timely release of metabolic heat and resulting in elevated body temperatures. This mechanism would partly explain why T. belangeri’s body temperature increases with ambient temperature during heat exposure. Compared to previous laboratory findings, the elevated thermal conductance values observed in our study indicate an active thermoregulatory response in T. belangeri, which enhances surface heat exchange to mitigate internal heat accumulation. This pattern has also been observed in the Hengduan Mountain small mammals E. miletus and A. chevrieri (Geng and Zhu, 2024), whereas arctic species like Sorex cinereus prioritize thermal insulation (Morrison et al., 1959). Additionally, this response is particularly significant for small mammals, which possess a high surface area-to-volume ratio that facilitates heat loss through their body surfaces (McNab, 2002). The increase in thermal conductance suggests that T. belangeri may adapt to global warming by improving surface heat dissipation, alleviating internal heat buildup, maintaining thermal equilibrium, and permitting a moderate rise in body temperature.

5 Conclusion

High-temperature acclimation enables T. belangeri to adapt to warmer environments by increasing body temperature to reduce the difference with ambient temperature, reducing RMR to decrease heat production capacity, enhancing heat conduction to improve heat dissipation capacity, and shifting the lower critical point of the TNZ. These adaptive strategies likely contribute to T. belangeri maintaining its internal thermal balance and improving its survival prospects in high-temperature environments. By comparing variations in the characteristics of the TNZ, it is observed that there has been no change in the UTNZ, suggesting a degree of adaptability to high temperatures. In addition, its TNZ is situated within tropical high-temperature regions, which further supports regarding tropical origins from the aspect of the TNZ.

Given its demonstrated thermal plasticity, we hypothesize that T. belangeri may expand its geographic range toward higher latitudes as global warming increases temperatures in temperate regions. Its stable UTNZ and efficient metabolic downregulation under heat stress would allow it to colonize areas previously too cool for sustained survival, potentially reaching beyond its current northern limit in the Hengduan Mountains. This expansion could lead to ecological competition with native temperate small mammals. Tupaia belangeri’s superior heat tolerance might allow it to outcompete these species in warmer microhabitats, altering community structures.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: Physiological analysis data to this submission can be found online at https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Physiological_data_of_high-temperature_domestication_experiment_of_Tupaia_belangeri_xlsx/29312960?file=55359788.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by All animal procedures were within the rules of Animals Care and Use Committee of School of Life Science, Yunnan Normal University. This study was approved by the Committee (13-0901-011). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

DL: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. WZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was financially supported by the National Natural Scientific Foundation of China (32160254) and Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (202401AS070039).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adam F., José Pedro S., do A., Kelly J., M Henry H., Paul J. (2017). Thermoregulatory performance and habitat selection of the eastern box turtle (Terrapene carolina carolina). Conserv. Physiol. 5 (1), cox070. doi:10.1093/conphys/cox070

Arends A., McNab B. K. (2001). The comparative energetics of ‘caviomorph’rodents. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A:Mol. Integr. Physiol. 130 (1), 105–122. doi:10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00371-3

Arends A., Bonaccorso F. J., Genoud M. (1995). Basal rates of metabolism of nectarivorous bats (Phyllostomidae) from a semiarid thorn forest in Venezuela. J. Mammal. 76 (3), 947–956. doi:10.2307/1382765

Aujard F., Perret M. (1998). Age-related effects on reproductive function and sexual competition in the male prosimian primate, Microcebus murinus. Physiol. Behav. 64 (4), 513–519. doi:10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00087-0

Ayres J. S. (2020). The biology of physiological health. Cell 181 (2), 250–269. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.036

Bao W. D., Wang D. H., Wang Z. W., Zhou Y. L., Wang L. M. (2000). Seasonal variation of resting metabolic rate of Dipus sagitta in Kubuqi sandy land of Ordos Plateau. Curr. Zool. 66 (2), 146–152. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-5507.2000.02.004

Bao W. D., Wang D. H., Wang Z. W., Zhou Y. L., Wang L. M. (2001). Seasonal variation of non shivering heat production of four rodents in Kubuqi sandy land, Inner Mongolia. J. Mammal. 21 (2), 101–106. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-1050.2001.02.004

Bartholomew G. A., Leitner P., Nelson J. E. (1964). Body temperature, oxygen consumption, and heart rate in three species of Australian flying foxes. Physiol. Zool. 37 (2), 179–198. doi:10.1086/physzool.37.2.30152330

Bartholomew G. A., Dawson W. R., Lasiewski R. C. (1970). Thermoregulation and heterothermy in some of the smaller flying foxes (Megachiroptera) of New Guinea. J. Comp. Physiol. A 70 (2), 196–209. doi:10.1007/bf00297716

Baudinette R. V. (1972). The physiological ecology of a burrowing rodent, Spermophilus beecheyi. Irvine: Univ. Calif.

Baudinette R. V., Churchill S. K., Christian K. A., Nelson J. E., Hudson P. J. (2000). Energy, water balance and the roost microenvironment in three Australian cave-dwelling bats (Microchiroptera). J. Comp. Physiol. 170 (5-6), 439–446. doi:10.1007/s003600000121

Bi Z. Q., Wen J., Shi L. L., Tan S., Xu X. M., Zhao Z. J. (2018). Effects of temperature and high-fat diet on metabolic thermogenesis andbody fat content in Striped hamsters. J. Mammal. 38 (4), 384–392. doi:10.16829/j.slxb.150159

Bonaccorso F. J., Arends A., Genoud M., Cantoni D., Morton T. (1992). Thermal ecology of moustached and ghost-faced bats (Mormoopidae) in Venezuela. J. Mammal. 73 (2), 365–378. doi:10.2307/1382071

Bozinovic F., Rosenmann M. (1989). Maximum metabolic rate of rodents: physiological and ecological consequences on distributional limits. Funct. Ecol. 3 (2), 173–181. doi:10.2307/2389298

Bozinovic F., RuÍz G., CortÉs A., Rosenmann M. (2005). Energética, termorregulación y sopor en la yaca Thylamys elegans (Didelphidae). Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 78 (2), 199–206. doi:10.4067/S0716-078X2005000200003

Bradley S. R., Hudson J. W. (1974). Temperature regulation in the tree shrew Tupaia glis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 48 (1), 55–60. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(74)90852-4

Bradley W. G., Miller J. S., Yousef M. K. (1974). Thermoregulatory patterns in pocket gophers: desert and mountain. Physiol. Zool. 47 (3), 172–179. doi:10.1086/physzool.47.3.30157854

Bremer C. M., Sominskaya I., Skrastina D., Pumpens P., Wahed A. A. E., Beutling U., et al. (2011). N-terminal myristoylation-dependent masking of neutralizing epitopes in the preS1 attachment site of hepatitis B virus. J. Hepatol. 55 (1), 29–37. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2010.10.019

Breyen L. J., Bradley W. G., Yousef M. K. (1973). Physiological and ecological studies on the chisel-toothed kangaroo rat, Dipodomys microps. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol. 44 (2), 543–555. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(73)90507-0

Bridges T. M., Tulapurkar M. E., Shah N. G., Singh I. S., Hasday J. D. (2012). Tolerance for chronic heat exposure is greater in female than male mice. Int. J. Hyperth. 28 (8), 747–755. doi:10.3109/02656736.2012.734425

Buffenstein R. (1984). The importance of microhabitat in thermoregulation and thermal conductance in two Namib rodents—a crevice dweller, Aethomys namaquensis, and a burrow dweller, Gerbillurus paeba. J. Therm. Biol. 9 (4), 235–241. doi:10.1016/0306-4565(84)90002-0

Buffenstein R., Jarvis J. U. (1985). Thermoregulation and metabolism in the smallest African gerbil, Gerbillus pusillus. J. Zool. 205 (1), 107–121. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1985.tb05616.x

Busch C., Malizia A. I., Scaglia O. A., Reig O. A. (1989). Spatial distribution and attributes of a population of Ctenomys talarum (Rodentia: Octodontidae). J. Mammal. 70 (1), 204–208. doi:10.2307/1381691

Campbell K. L., Hochachka P. W. (2000). Thermal biology and metabolism of the American shrew-mole, Neurotrichus gibbsii. J. Mammal. 81 (2), 578–585. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2000)081<0578:TBAMOT>2.0.CO;2

Castellanos-Frias E., Garcia-Perea R., Gisbert J., Bozinovic F., Virgós E. (2015). Intraspecific variation in the energetics of the Cabrera vole. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A:Mol. Integr. Physiol. 190 (8), 32–38. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.08.011

Chen K. X., Wang C. M., Wang G. Y., Zhao Z. J. (2014). Energy budget, oxidative stress and antioxidant in striped hamster acclimated to moderate cold and warm temperatures. J. Therm. Biol. 44 (6), 35–40. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2014.06.005

Chen H. B., Zhang H., Jia T., Wang Z. K., Zhu W. L. (2022). Roles of leptin on energy balance and thermoregulation in Eothenomys miletus. Front. Physiol. 13, 1054107. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.1054107

Chi Q. S., Wang D. H. (2011). Thermal physiology and energetics in male desert hamsters (Phodopus roborovskii) during cold acclimation. J. Comp. Physiol. B 181 (1), 91–103. doi:10.1007/s00360-010-0506-6

Collins B. G., Bradshaw S. D. (1973). Studies on the metabolism, thermoregulation, and evaporative water losses of two species of Australian rats, Rattus villosissimus and Rattus rattus. Physiol. Zool. 46 (1), 1–21. doi:10.1086/physzool.46.1.30152512

Cruz-Neto A. P., Abe A. S. (1997). Metabolic rate and thermoregulation in the nectarivorous bat, Glossophaga soricina (Chiroptera, Phyllostomatidae). Rev. Bras. Biol. 57 (2), 203–209.

Deavers D. R., Hudson J. W. (1981). Temperature regulation in two rodents (Clethrionomys gapperi and Peromyscus leucopus) and a shrew (Blarina brevicauda) inhabiting the same environment. Physiol. Zool. 54 (1), 94–108. doi:10.1086/physzool.54.1.30155808

Dempster E. R., Perrin M. R., Downs C. T., Griffin M. (1998). Gerbillurus setzeri. Mamm. Species (598), 1–4. doi:10.2307/3504394

Dempsters E. R., Perrin M. R., Downs C. T. (1999). Gerbillurus vallinus. Mamm. Species 605, 1–4. doi:10.2307/3504512

Downs C. T., Perrin M. R. (1990). Field water-turnover rates of three Gerbillurus species. J. Arid. Environ. 19 (2), 199–208. doi:10.1016/S0140-1963(18)30818-8

Feierabend D., Kielland K. (2015). Seasonal effects of habitat on sources and rates of snowshoe hare predation in Alaskan boreal forests. PLoS One 10 (12), e0143543. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143543

Feng J. H., Jia T., Wang Z. K., Zhu W. L. (2022). Differences of energy adaptation strategies in Tupaia belangeri between Pianma and Tengchong region by metabolomics of liver: role of warmer temperature. Front. Physiol. 13, 1068636. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.1068636

Fu J. H., Wang X., Zhu W. L., Gao W. R., Wang Z. K. (2018). Genetic variation of different populations in tree shrews (Tupaia belangeri) based on mtDNA cytochrome oxidase subunit I gene. Acta. Theriologica. Sinica. 38 (2), 183–191. doi:10.16829/j.slxb.20180301

Gębczyńska Z., Gębczyński M. (1965). Oxygen consumption in two species of water-shrews. Acta Theriol. 10 (13), 209–214. doi:10.4098/AT.arch.65-13

Geiser F. (1987). Hibernation and daily torpor in two pygmy possums (Cercartetus spp., Marsupialia). Physiol. Zool. 60 (1), 93–102. doi:10.1086/physzool.60.1.30158631

Geiser F., Baudinette R. V. (1987). Seasonality of torpor and thermoregulation in three dasyurid marsupials. J. Comp. Physiol. B 157 (3), 335–344. doi:10.1007/BF00693360

Geiser F., Gasch K., Bieber C., Stalder G. L., Gerritsmann H., Ruf T. (2016). Basking hamsters reduce resting metabolism, body temperature and energy costs during rewarming from torpor. J. Exp. Biol. 219 (14), 2166–2172. doi:10.1242/jeb.137828

Geng Y., Zhu W. L. (2024). Comparative study of thermoregulatory and thermogenic characteristics of three sympatric rodent species: the impact of high-temperature acclimation. Indian J. Anim. Res. 58 (12), 0367–6722. doi:10.18805/IJAR.BF-1840

Genoud M., Bonaccorso F. J. (1986). Temperature regulation, rate of metabolism, and roost temperature in the greater white-lined bat Saccopteryx bilineata (Emballonuridae). Physiol. Zool. 59 (1), 49–54. doi:10.1086/physzool.59.1.30156089

Genoud M., Bonaccorso F. J., Anends A. (1990). Rate of metabolism and temperature regulation in two small tropical insectivorous bats (Peropteryx macrotis and Natalus tumidirostris). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol. 97 (2), 229–234. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(90)90177-T

Guo Y. Y., Hao S., Zhang M., Zhang X., Wang D. (2020). Aquaporins, evaporative water loss and thermoregulation in heat-acclimated Mongolian gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus). J. Therm. Biol. 91, 102641. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2020.102641

Haim A., Fairall N. (1987). Bioenergetics of an herbivorous rodent Otomys irroratus. Physiol. Zool. 60 (3), 305–309. doi:10.1086/physzool.60.3.30162283

Hou J. J., Li Q. F., Huang C. X. (1999). Mechanisms of adaptive thermogenesis in brandt's voles (Microtus brandti) during cold exposure. Curr. Zool. 65 (2), 143–147. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-5507.1999.02.004

Hua Y., Zhang W., Xu Y. C. (2010). Seasonal variation of pelage characteristics in siberian weasel (Mustela sibirica) of Xiaoxing’anling area Heilongjiang, China. Acta. Theriologica. Sinica. 30 (1), 110–114.

Huang C. M., Zhang L., Zhu W. L., Yang S. C., Yu T. T., Wang Z. K. (2013). Thermoregulation and thermogenesis characteristics of Tupaia belangeri in Kunming and Luquan, Yunnan. Sichuan J. Zool. 32 (5), 670–675. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-7083.2013.05.005

Hudson J. W. (1965). Temperature regulation and torpidity in the pygmy mouse, Baiomys taylori. Physiol. Zool. 38 (3), 243–254. doi:10.1086/physzool.38.3.30152836

Jansky L. (1959). Working oxygen consumption in two species of wild rodents (Microtus arvalis, Clethrionomys glareolus). Physiol 8, 472–478. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1973.tb01115.x

Jia T., Yang X. M., Li Z. H., Zhu W. L., Xiao C. H., Liu C. Y., et al. (2008). Taxonomic significance of Tupaia belangeri from Luquan district, Kunming, China based on cyt b gene sequences. Chin. J. Zool. (04), 26–33. doi:10.3969/j.issn.0250-3263.2008.04.005

Katzner T. E., Parker K. L. (1997). Vegetative characteristics and size of home ranges used by pygmy rabbits (Brachylagus idahoensis) during winter. J. Mammal. 78 (4), 1063–1072. doi:10.2307/1383049

Kingma B. R., Frijns A. J., Schellen L., van Marken Lichtenbelt W. D. (2014). Beyond the classic thermoneutral zone: including thermal comfort. Temperature 1 (2), 142–149. doi:10.4161/temp.29702

Kinnear A., Shield J. W. (1975). Metabolism and temperature regulation in marsupials. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol. 52 (1), 235–245. doi:10.1016/S0300-9629(75)80159-9

Król E. (1994). Metabolism and thermoregulation in the eastern hedgehog Erinaceus concolor. J. Comp. Physiol. B 164, 503–507. doi:10.1007/BF00714589

Layne J. N., Dolan P. G. (1975). Thermoregulation, metabolism, and water economy in the golden mouse (Ochrotomys nuttalli). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol. 52 (1), 153–163. doi:10.1016/S0300-9629(75)80146-0

Leitner P., Nelson J. E. (1967). Body temperature, oxygen consumption and heart rate in the Australian false vampire bat, Macroderma gigas. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 21 (1), 65–74. doi:10.1016/0010-406X(67)90115-6

Liu X., Wei F., Li M., Jiang X., Feng Z., Hu J. (2004). Molecular phylogeny and taxonomy of wood mice (genus Apodemus Kaup, 1829) based on complete mtDNA cytochrome b sequences, with emphasis on Chinese species. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 33 (1), 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2004.05.011

Lovegrove B. G. (1986). The metabolism of social subterranean rodents: adaptation to aridity. Oecologia 69, 551–555. doi:10.1007/BF00410361

Lovegrove B. G., Heldmaier G., Knight M. (1991). Seasonal and circadian energetic patterns in an arboreal rodent, Thallomys paedulcus, and a burrow-dwelling rodent, Aethomys namaquensis, from the Kalahari Desert. J. Therm. Biol. 16 (4), 119–209. doi:10.1016/0306-4565(91)90026-X

MacMillen R. E., Lee A. K. (1969). Water metabolism of Australian hopping mice. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 28 (2), 493–514. doi:10.1016/0010-406X(69)92086-6

McAllister E. J., Dhurandhar N. V., Keith S. W., Aronne L. J., Barger J., Baskin M., et al. (2009). Ten putative contributors to the obesity epidemic. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 49 (10), 868–913. doi:10.1080/10408390903372599

McDevitt R. M., Andrews J. F. (1994). The importance of nest utilization as a behavioural thermoregulatory strategy in Sorex minutus the pygmy shrew. J. Therm. Biol. 19 (2), 97–102. doi:10.1016/0306-4565(94)90056-6

McNab B. K. (1966). The metabolism of fossorial rodents: a study of convergence. Ecology 47 (5), 712–733. doi:10.2307/1934259

McNab B. K. (1969). The economics of temperature regulation in neotropical bats. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 31 (2), 227–268. doi:10.1016/0010-406X(69)91651-X

McNab B. K. (1978). The comparative energetics of neotropical marsupials. J. Comp. Physiol. 125, 115–128. doi:10.1007/BF00686747

McNab B. K. (1979). The influence of body size on the energetics and distribution of fossorial and burrowing mammals. Ecology 60 (5), 1010–1021. doi:10.2307/1936869

McNab B. K. (1989). Temperature regulation and rate of metabolism in three Bornean bats. J. Mammal. 70 (1), 153–161. doi:10.2307/1381678

McNab B. K. (2002). The physiological ecology of vertebrates: a view from energetics. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

McNab B. K. (2009). Ecological factors affect the level and scaling of avian BMR. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 152 (1), 22–45. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.08.021

McNab B. K., Bonaccorso F. J. (2001). The metabolism of New Guinean pteropodid bats. J. Comp. Physiol. B 171, 201–214. doi:10.1007/s003600000163

McNab B. K., Wright P. C. (1987). Temperature regulation and oxygen consumption in the Philippine tarsier Tarsius syrichta. Physiol. Zool. 60 (5), 596–600. doi:10.1086/physzool.60.5.30156133

Mónus F., Barta Z. (2016). Is foraging time limited during winter? A feeding experiment with tree sparrows under different predation risk. Ethology 122 (1), 20–29. doi:10.1111/eth.12439

Morrison P., Ryser F. A., Dawe A. R. (1959). Studies on the physiology of the masked shrew Sorex cinereus. Physiol. Zool. 32 (4), 256–271. doi:10.1086/physzool.32.4.30155403

Morton S. R., Lee A. K. (1978). Thermoregulation and metabolism in Planigale maculata (Marsupialia: Dasyuridae). J. Therm. Biol. 3 (3), 117–120. doi:10.1016/0306-4565(78)90003-7

Naya D. E., Spangenberg L., Naya H., Bozinovic F. (2013). Thermal conductance and basal metabolic rate are part of a coordinated system for heat transfer regulation. Proc. R. Soc. B 280 (1767), 20131629. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.1629

Neal C. M., Lustick S. I. (1973). Energetics and evaporative water loss in the short-tailed shrew Blarina brevicauda. Physiol. Zool. 46 (3), 180–185. doi:10.1086/physzool.46.3.30155600

Nicol S. C. (1976). Oxygen consumption and nitrogen metabolism in the potoroo, Potorous tridactylus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol. 55 (3), 215–218. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(76)90134-1

Noll-Banholzer U. (1979). Body temperature, oxygen consumption, evaporative water loss and heart rate in the fennec. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol. 62 (3), 585–592. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(79)90108-7

Packard G. C. (1968). Oxygen consumption of Microtus montanus in relation to ambient temperature. J. Mammal. 49 (2), 215–220. doi:10.2307/1377977

Pauls R. W. (1981). Energetics of the red squirrel: a laboratory study of the effects of temperature, seasonal acclimatization, use of the nest and exercise. J. Therm. Biol. 6 (2), 79–86. doi:10.1016/0306-4565(81)90057-7

Rising R., Whyte K., Albu J., Pi-Sunyer X. (2015). Evaluation of a new whole room indirect calorimeter specific for measurement of resting metabolic rate. Nutr. Metab. 12 (1), 46–55. doi:10.1186/s12986-015-0043-0

Roberts T. E., Lanier H. C., Sargis E. J., Olson L. E. (2011). Molecular phylogeny of treeshrews (Mammalia: Scandentia) and the timescale of diversification in Southeast Asia. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 60 (3), 358–372. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.04.021

Rodríguez-Durán A. (1995). Metabolic rates and thermal conductance in four species of neotropical bats roosting in hot caves. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol. 110 (4), 347–355. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(94)00174-R

Rübsamen K., Hume I. D., Foley W. J., Rübsamen U. (1984). Implications of the large surface area to body mass ratio on the heat balance of the greater glider (Petauroides volans: Marsupialia). J. Comp. Physiol. B 154, 105–111. doi:10.1007/BF00683223

Salaün C., Courvalet M., Rousseau L., Cailleux K., Breton J., Bôle-Feysot C., et al. (2024). Sex-dependent circadian alterations of both central and peripheral clock genes expression and gut–microbiota composition during activity-based anorexia in mice. Biol. Sex. Differ. 15 (1), 6. doi:10.1186/s13293-023-00576-x

Schmidt-Nielsen K. (1997). Animal physiology: adaptation and environment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 169–214. doi:10.1017/9780511801822

Scholander P. F., Hock R., Walters V., Johnson F., Irving L. (1950). Heat regulation in some arctic and tropical mammals and birds. Biol. Bull-Us 99 (2), 237–258. doi:10.2307/1538741

Shiratsuru S., Majchrzak Y. N., Peers M. J., Studd E. K., Menzies A. K., Derbyshire R., et al. (2021). Food availability and long-term predation risk interactively affect antipredator response. Ecology 102 (9), e03456. doi:10.1002/ecy.3456

Soriano P. J., Ruiz A., Arends A. (2002). Physiological responses to ambient temperature manipulation by three species of bats from Andean cloud forests. J. Mammal. 83 (2), 445–457. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2002)083<0445:PRTATM>2.0.CO;2

Speers-Roesch B., Norin T., Driedzic W. R. (2018). The benefit of being still: energy savings during winter dormancy in fish come from inactivity and the cold, not from metabolic rate depression. Proc. R. Soc. B 285 (1886), 20181593. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.1593

Stawski C., Simmonds E. G. (2021). Contrasting physiological responses to habitat degradation in two arboreal mammals. Iscience 24 (12), 103453. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.103453

Terblanche J. S., Janion C., Chown S. L. (2007). Variation in scorpion metabolic rate and rate–temperature relationships: implications for the fundamental equation of the metabolic theory of ecology. J. Evol. Biol. 20 (4), 1602–1612. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2007.01322.x

Vejmělka F., Okrouhlík J., Lövy M., Šaffa G., Nevo E., Bennett N. C., et al. (2021). Heat dissipation in subterranean rodents: the role of body region and social organisation. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 2029. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-81404-3

Wang Z. Y., Guan S. J., Yang M., Peng X., Zhao Y. (2010). The metabolic thermogenesis and thermoregulation of Lesser white toothed shrew (Crocidura suaveolens). Acta. Theriologica. Sinica. 30 (2), 195–199.

Wang D. H., Zhao Z. J., Zhang X. Y., Zhang Z. Q., Xu D. L., Xing X., et al. (2021). Research advances and prespectives in mammal physiological ecology in China. J. Mammal. 41 (5), 19. doi:10.16829/j.slxb.150558

Wiegert R. G. (1961). Respiratory energy loss and activity patterns in the meadow vole, Microtus pennsylvanicus pennsylvanicus. Ecology 42 (2), 245–253. doi:10.2307/1932076

Xiao C., Wang Z., Zhu W., Chu Y., Liu C., Jia T., et al. (2010). Energy metabolism and thermoregulation in pygmy lorises (Nycticebus pygmaeus) from Yunnan Daweishan Nature Reserve. Acta Ecol. Sin. 30 (3), 129–134. doi:10.1016/j.chnaes.2010.04.002

Yang Y. Z., Jia T., Zhang H., Wang Z. K., Zhu W. L. (2021). Seasonal variations of thermoregulation and thermal neutral zone shift in eothenomys olitor. J. Biol. 38 (6), 41–44. doi:10.3969/j.issn.2095-1736.2021.06.041

Yin X. H., Yang C. J., Wang C., Yin Z. W., Yang Y. J., Jiang P., et al. (2009). Impact of hypothermia on coagulation function in rats. Chin. J. Public Health. 25 (8), 957. doi:10.11847/zgggws2009-25-08-33

Zhang L., Wang R., Yang F., Xie J., Wang Z. K., Gong Z. D., et al. (2009). Thermogenesis characteristics of cold adaptation of liver in Tupaia belangeri. Chin. J. Zool. 44 (04), 47–57. doi:10.3969/j.issn.0250-3263.2009.04.008

Zhang L., Liu P. F., Zhu W. L., Cai J. H., Wang Z. K. (2012). Variations in thermal physiology and energetics of the tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri) in response to cold acclimation. J. Comp. Physiol. B 182, 167–176. doi:10.1007/s00360-011-0606-y

Zhang K. Y., Zhou J., Cao J., Zhao Z. J. (2025). The impact of heat dissipation capacity on the energy metabolism of Striped hamsters. Acta Ecol. Sin. 45 (04), 1763–1774. doi:10.20103/j.stxb.202406151389

Zhang W. X., Wang Z. K., Nian Y. K., Xu W. J., Yao Z. (2001). Effects of cold acclimation on thermogenic capacity of Tupaia belangeri. Zool Res. 22 (4), 387–391. doi:10.3321/j.issn:0254-5853.2001.04.006

Zhao Z. J., Cao J., Liu Z. C., Wang G. Y., Li L. S. (2010). Seasonal regulations of resting metabolic rate and thermogenesis in striped hamster (Cricetulus barabensis). J. Therm. Biol. 35 (8), 401–405. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2010.08.005

Zhao Z. J., Chi Q. S., Liu Q. S., Zheng W. H., Liu J. S., Wang D. H. (2018). The shift of thermoneutral zone in striped hamster acclimated to different temperatures. PLoS One 9 (1), e84396. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084396

Zhao Z. C., Luo Y., Huang J. B. (2024). Global warming and China warming. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 20 (6), 808–812.

Zhu W. L., Jia T., Lian X., Wang Z. K. (2008). Evaporative water loss and energy metabolic in two small mammals, voles (Eothenomys miletus) and mice (Apodemus chevrieri), in Hengduan mountains region. J. Therm. Biol. 33 (6), 324–331. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2008.04.002

Zhu W. L., Jia T., Cai J. H., Wang Z. K. (2014). Study on genetic diversity of mitochondrial cytochrome b gene and D-loop gene in Tupaia belangeri from Yunnan Province. Chin. J. Zool. 31 (06), 11–14+21. doi:10.3969/j.issn.2095-1736.2014.06.011

Zhu W. L., Sun S. R., Chen J. L., Cai J. H., Zhang H., Meng L. H., et al. (2016). Seasonal variations of thermomoneutral zone and evaporativewater loss in Apodemus chevrieri. J. Biol. 33 (1), 57–61. doi:10.3969/j.issn.2095-1736.2016.01.057

Keywords: Tupaiidae, thermoregulation, rest metabolic rate, thermal neutral zone, thermal conductance, tropical origin

Citation: Liu D and Zhu W (2025) Physiological adaptation strategies for thermoregulation in Tupaia belangeri under high-temperature environment challenge. Front. Physiol. 16:1651991. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2025.1651991

Received: 23 June 2025; Accepted: 07 August 2025;

Published: 28 August 2025.

Edited by:

Fernando Hinostroza, Universidad Católica del Maule, ChileReviewed by:

Artur Antunes Navarro Valgas, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, BrazilLuis Pastenes, Catholic University of the Maule, Chile

Copyright © 2025 Liu and Zhu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wanlong Zhu, endsXzgzMDdAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Dongjie Liu

Dongjie Liu Wanlong Zhu

Wanlong Zhu