- 1Laboratorio de Cirurgia Cardiovascular e Fisiopatologia da Circulação (LIM-11), Instituto do Coração (InCor), Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

- 2Department of Surgery, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

- 3Department of Laboratory Medicine, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

- 4Department of Anesthesiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

- 5Department of Internal Medicine, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

Successful organ transplantation depends on several factors, including donor and recipient sex and age. Experimental data show that donor inflammatory status can be influenced by sex hormones, and, after brain death, there are significant differences in organ quality. Sex hormones also influence the immune system during different life stages, for example, during menopause there is a significant reduction in estrogen levels. Thus, the primary aim of this study is to evaluate the steroid profile of human donors after brain death. We performed a retrospective observational case-control study and selected samples from living (LD) and brain-dead (BD) donors from the TransplantLines Biobank and Cohort Study. Donors were stratified by age as Young (Y) from 20–40 years and Old (O), older than 55 years. Serum steroidal hormones from one hundred donors were analysed through LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry). In BD-females, cortisol and estradiol decreased significantly (p = 0.0001) in both age groups when compared to LD. However, an increase in progesterone was seen after BD for older donors (p = 0.0001). In BD-males, cortisol decreased significantly in both age (p = 0.0001) groups when compared to LD. For testosterone, the results were similar as BD decreased the steroid levels (p = 0.0001) compared to LD in both age groups. In conclusion, our results indicate that steroid hormone levels decrease after brain death.

Introduction

Clinical evidence suggests that successful organ transplantation depends on several factors, including donor and recipient sex and age (Chambers et al., 2021). Studies have shown that sex-mismatched transplants, particularly female-to-male combinations, are associated with worse outcomes in several organs (Tan et al., 2012; Khush et al., 2012; Coffman et al., 2023). Indeed, a growing body of evidence highlights the role of female sex hormones in the immunological response, a key factor in graft quality and transplant outcomes.

Experimental evidence shows that organ inflammatory status can be influenced by sex hormones (Bonnano Abib et al., 2020) and after brain death induction, females present higher lung (Breithaupt-Faloppa et al., 2016; Ricardo-da-Silva et al., 2021a; Simão et al., 2016; Ricardo-da-Silva et al., 2024; Vidal-Dos-Santos et al., 2025), heart (Ricardo-da-Silva et al., 2020), kidney (Ricardo-da-Silva et al., 2021b) and intestinal (Ferreira et al., 2018) inflammation compared to controls. Additionally, comparing brain dead males and females, a worse inflammatory profile was seen in the females (Breithaupt-Faloppa et al., 2016; Simão et al., 2016; Vidal-Dos-Santos et al., 2025; Correia et al., 2019). These differences could be associated with the acute reduction in female (Breithaupt-Faloppa et al., 2016; Simão et al., 2016) and male sex hormones (Vidal-Dos-Santos et al., 2025) highlighting the impact of hormonal status on the quality of organs from brain-dead donors.

Furthermore, sex hormones also influence immune senescence during different life stages (Khan and Ansar, 2016). Donors have been getting older, and the relevance of age has become more impactful (Dayoub et al., 2018). For instance, menopause results in a significant reduction in estrogen levels (Baker and Benayoun, 2023) and these hormonal changes, along with differences in sex-specific antigens and immune responses, may affect transplant outcomes.

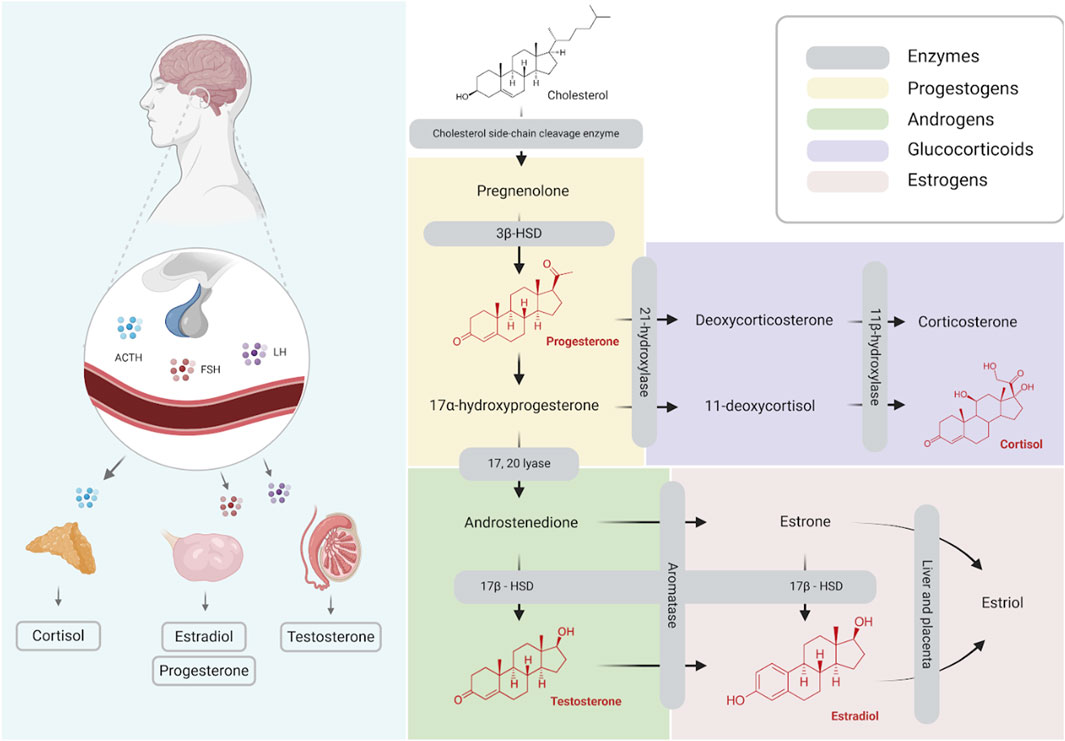

Thus, the primary aim of this study is to evaluate the effects of brain death in the steroid profile of human donors (Figure 1, Steroidal Cascade).

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of steroid hormones synthesis (Created with BioRender.com).

Methods

Study design/statement of ethics

This study was designed as a retrospective observational case-control study and used samples from brain-death (BD) transplant donors included in the TransplantLines Biobank and Cohort Study (NCT identifier NCT03272841). It was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University Medical Center Groningen, Netherlands (UMCG; METc 2014/077), and for which informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Patient samples

The hormones evaluated were estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4) in females; testosterone (T) in males and cortisol (Cort) in both groups. The control groups were living donors (LD). The blood samples were obtained from TransplantLines biobank, which collects biological material and medical data from patients before and after organ transplantation, as well as from potential organ donors, both living and deceased. The samples used here were stored at −80 °C (slow freezing trajectory) and aliquots were thawed for the hormone quantifications.

Both sex groups were stratified into young (Y) and old (O). Donors aged 20–40 years were considered Young (Y) and older than 55 years were considered Old (O).

Analysis

Donor serum was used to measure the steroids via liquid chromatography in combination with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) requiring three different assays. T and P4 were analyzed in 200 µL of serum as previously described (van der Veen et al., 2019). Cort was analyzed in 200 µL of serum as previously described (Werumeus et al., 2016). E2 was analyzed using 200 µL serum as follows: 100 µL [13C3]-estradiol was added, 500 µL methanol and the samples were mixed for 10 minutes and centrifuged afterwards. The supernatant was extracted using an Oasis MAX µElution Plate 30 µm and eluted with 40 µL methanol. This was evaporated and dissolved again in 110 µL 50% MeOH/H2O (v/v %). Fifty microliters were injected on a Waters ACQUITY 2D-UPLC system in combination with a XEVO TQ Absolute mass spectrometer. E2 was analyzed in negative ion mode using 271.1 > 145 as quantifier, and 271.1 > 183 as qualifier. For [13C3]-estradiol 274.1 > 148 was used as a quantifier and 274.1 > 186 as qualifier. All samples were analyzed in one batch for each analysis.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism (Version 10.01; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, United States). Data normality distribution was analysed by Shapiro-Wilk test. Age and BD time were expressed as mean and standard deviation, while hormonal data were expressed as median and interquartile variation. Hormonal data were submitted to rank transformation and analysed by two-way analysis of variance followed by the Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli test for multiple comparisons.

Results

A total of 100 patients was selected for the study (50 females and 50 males). Among the BD donors, 21 were females and 19 were males. In the control group (Living donors, LD), 29 were females and 31 were males. In females, the most frequent cause of death was bleeding (13 of 21), however, for males, (9 of 19) it was trauma related. Main characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

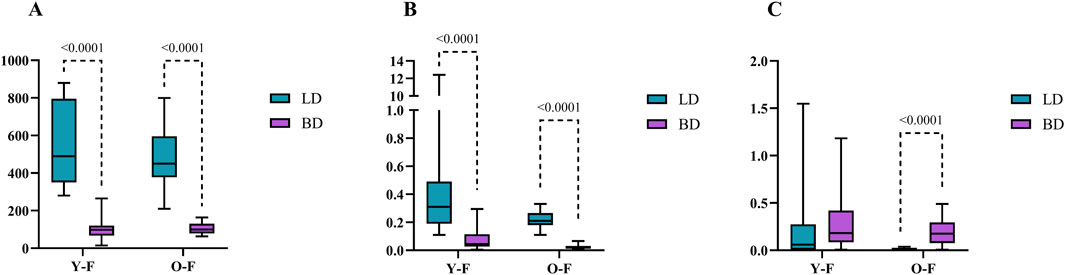

In females, cortisol was only altered by BD occurrence (p = 0.0001) with decreased values after BD in both Y [98.25 nmol/L (120.82–66.69)] and O [99.45 nmol/L (130.32–78.99)] groups, when compared to LD in Y [489.4 nmol/L (795.8–350.5)] and O [450.2 (595.1–378.3)] (Figure 2A). Regarding estradiol, values were altered by BD (p = 0.0001) and age (p = 0.0036). In this sense, estradiol decreased significantly under both BD groups, Y [0.045 nmol/L (0.114–0.026) and O [0.018 nmol/L (0.031–0.013)], when compared to LD groups, Y [0.310 nmol/L (0.490–0.190)] and O [0.210 nmol/L (0.265–0.180)] (Figure 2B). Progesterone values were also altered by BD (p = 0.0001) and age (p = 0.0538), but an increase in progesterone was seen after BD for the O group [0.177 nmol/L (0.295–0.076)] in comparison to respective LD [0.012 nmol/L (0.019–0.005)], which was also observed between the Y groups, BD [0.181 nmol/L (0.419–0.085)] and LD [m0.059 nmol/L (0.274–0.005)] (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Serum concentrations of cortisol (A) estradiol (B) and progesterone (C) in female donors (nmol/L). Data were expressed as median with min and max. Y-F, Young females; O-F, Old females; BD, brain dead donors and LD, living donors.

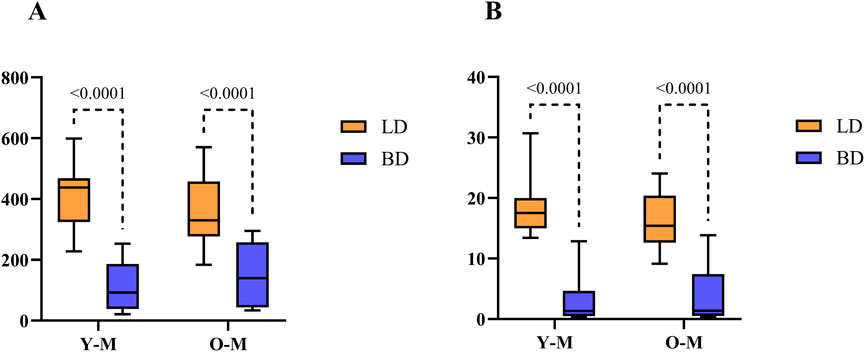

As shown in Figure 3A, cortisol was also only altered in males by the occurrence of BD (p < 0.0001), whose values were decreased significantly in both Y [92.32 nmol/L (186.48–38.22)] and O [139,98 nmol/L (257.52–43.42)] groups when compared to LD, Y [437.7 nmol/L (468.3–324.1)] and O [329.75 nmol/L (457.95–277.12)]. Figure 3B shows that for testosterone, the results were in line with the steroid levels, as BD values were decreased in Y [1.32 nmol/L (4.64–0.49)] and O [1.37 nmol/L (7.40–0.51)] when compared to LD in both age groups, Y [17.51 nmol/L (19.97–14.98)] and O [15.41 nmol/L (20.38–12.61)] (p = 0.0001).

Figure 3. Hormonal quantification of cortisol (A) and testosterone (B) in males (nmol/L). Data were expressed as median with min and max. Y-M, Young males; O-M, Old males; BD, brain dead donors and LD, living donors.

Discussion

Our study presents a cohort of BD donors’ hormonal profiles in the Netherlands. Overall, there is a significant decrease in steroid hormones after BD when compared to living donors. Past experimental findings indicate that BD is associated with an acute reduction in hormone levels (Breithaupt-Faloppa et al., 2016; Simão et al., 2016; Vidal-Dos-Santos et al., 2025; Ricardo-da-Silva et al., 2020). As known, hypothalamus and pituitary failure create important hormonal and metabolic imbalances. A longer period of BD may lead to lower levels of steroid hormones due to peripheral consumption of circulating hormones. This pattern is observed for cortisol, estradiol, and testosterone.

We stratified the data by sex and observed that both females and males exhibit this hormonal decline. Regarding age, although older females already present lower hormone levels, a further decrease is still observed. Menopause is a physiological process that occurs between the ages of 45 and 55, during which women experience a decline in mature follicles and estrogen-producing units (Pea et al., 2025). Estrogens exert negative feedback on the production and release of follicle-stimulating hormones (FSH). As a result, perimenopausal women often present elevated FSH levels, which may lead to an abnormally high maturity rate of developing follicles. In contrast, luteinizing hormone (LH) levels generally remain within the normal range (Larsson-Cohn, 1985).

One important variable to be considered within the groups is the donor’s cause of death. The different aetiologies of BD, whether slow or fast, lead to varying degrees of organ-specific injury (Vidal-Dos-Santos et al., 2025; Rebolledo et al., 2016; van Zanden et al., 2020). This factor must be considered when evaluating steroid hormone behaviour because regional blood flow in the hypothalamus during BD suggests that there may be minimal and slow flow sufficient to maintain the integrity of part of the hypothalamus, enabling at least some hormone transport (Arita et al., 1993). For instance, Arita et al. (1993) observed severe hypocortisolism in only 23% of BD cases. Although in our study the cause of death did not appear to influence hormonal status, this remains a key factor to consider.

The effects of steroids are modulated by stress, which provides energy through cholesterol and other lipid derivatives, promoting 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity. In hemorrhagic shock, increased secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) may stimulate cortisol production. It is known that adrenal androgens can be aromatized into estrogens (Christeff et al., 1988). Unlike brain-dead patients, male patients in shock also show elevated estradiol levels and reduced testosterone levels (Christeff et al., 1988). Furthermore, decreased serum testosterone in critically ill males and postmenopausal women have been linked to reduced 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity and/or increased aromatization (Spratt et al., 1993). These factors contribute to the reduced testosterone levels observed in males after BD.

It is relevant to consider the half-life of the primary analysed steroids. Progesterone has a half-life of approximately 5 minutes in the body (Taraborrelli, 2015), testosterone remains in circulation for 60–80 min (Hellman and Rosenfeld, 1974), and cortisol has a reported half-life of 76.5 min (Hindmarsh and Charmandari, 2015). Estradiol, when administered orally at a dose of 4 mg, has a mean half-life of 13.5 ± 4.4 h (Kuhnz et al., 1993). Hormonal differences may result from metabolism: progesterone is rapidly reduced into other steroid precursors, while estradiol is synthesized later from testosterone and estrone (Figure1). It is possible that during stress of the BD onset, the adrenal glands synthesize great amounts of allopregnanolone (Purdy et al., 1991), which would be converted to progesterone.

Our initial data support previous observations from experimental studies; however, studies with larger populations are needed to validate these findings. Further studies assessing different age groups, particularly among women, are necessary to determine the variation in hormone levels throughout life. Unfortunately, interfering variables such as hormone therapy and medication intake, which could influence final donor serum concentrations, are not available for evaluation in this study. One important variable to be considered within the groups is the donor’s cause of death.

In conclusion, our results suggest that steroid hormone levels decrease after BD. Future studies evaluating the hormonal profiles of donors may provide greater insight into donor management and organ quality.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board of the University Medical Center Groningen, Netherlands (UMCG; METc 2014/077). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The human samples used in this study were acquired from a by-product of routine care or industry. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

Md: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis, Data curation. FR-d-S: Writing – review and editing, Investigation, Visualization, Validation, Methodology. MV-d-S: Visualization, Methodology, Writing – review and editing, Investigation. MV: Validation, Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Data curation, Methodology. PO: Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Methodology, Validation. GN-M: Investigation, Visualization, Validation, Writing – review and editing. CC: Writing – review and editing, Validation, Investigation, Visualization. SB: Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Methodology, Resources, Validation. LM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Data curation, Formal Analysis. HL: Investigation, Supervision, Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review and editing. AB-F: Supervision, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Validation, Conceptualization, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Grant 88887.511368/2020–00, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior–CAPES and 88887.716771/2022–00 from Program CAPES-PRINT. Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - CAPES.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Arita K., Uozumi T., Oki S., Kurisu K., Ohtani M., Mikami T. (1993). The function of the hypothalamo-pituitary axis in brain dead patients. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 123 (1-2), 64–75. doi:10.1007/BF01476288

Baker C., Benayoun B. A. (2023). Menopause is more than just loss of fertility. Public Policy Aging Rep. 33 (4), 113–119. doi:10.1093/ppar/prad023

Bonnano Abib A. L. O., Correia C. J., Armstrong-Jr R., Ricardo-da-Silva F. Y., Ferreira S. G., Vidal-Dos-Santos M., et al. (2020). The influence of female sex hormones on lung inflammation after brain death - an experimental study. Transpl. Int. 33 (3), 279–287. doi:10.1111/tri.13550

Breithaupt-Faloppa A. C., Ferreira S. G., Kudo G. K., Armstrong R., Tavares-de-Lima W., da Silva L. F., et al. (2016). Sex-related differences in lung inflammation after brain death. J. Surg. Res. 200 (2), 714–721. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2015.09.018

Chambers D. C., Perch M., Zuckermann A., Cherikh W. S., Harhay M. O., Hayes D., et al. (2021). The international thoracic organ transplant registry of the international society for heart and lung transplantation: thirty-eighth adult lung transplantation report - 2021; focus on recipient characteristics. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 40 (10), 1060–1072. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2021.07.021

Christeff N., Benassayag C., Carli-Vielle C., Carli A., Nunez E. A. (1988). Elevated oestrogen and reduced testosterone levels in the serum of Male septic shock patients. J. Steroid Biochem. 29 (4), 435–440. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(88)90254-3

Coffman D., Jay C. L., Sharda B., Garner M., Farney A. C., Orlando G., et al. (2023). Influence of donor and recipient sex on outcomes following simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation in the new millennium: single-center experience and review of the literature. Clin. Transpl. 37 (1), e14864. doi:10.1111/ctr.14864

Correia C. J., Armstrong R. Jr, Carvalho P. O., Simas R., Sanchez D. C. J., Breithaupt-Faloppa A. C., et al. (2019). Hypertonic saline solution reduces microcirculatory dysfunction and inflammation in a rat model of brain death. Shock 51 (4), 495–501. doi:10.1097/SHK.0000000000001169

Dayoub J. C., Cortese F., Anžič A., Grum T., de Magalhães J. P. (2018). The effects of donor age on organ transplants: a review and implications for aging research. Exp. Gerontol. 110, 230–240. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2018.06.019

Ferreira S. G., Armstrong-Jr R., Kudo G. K., de Jesus Correia C., Dos Reis S. T., Sannomiya P., et al. (2018). Differential effects of brain death on rat microcirculation and intestinal inflammation: female versus Male. Inflammation 41 (4), 1488–1497. doi:10.1007/s10753-018-0794-7

Hellman L., Rosenfeld R. S. (1974). Metabolism of testosterone-1,2-3H in man. Distribution of the major 17-ketosteroid metabolites in plasma: relation to thyroid states. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 38 (3), 424–435. doi:10.1210/jcem-38-3-424

Hindmarsh P. C., Charmandari E. (2015). Variation in absorption and half-life of hydrocortisone influence plasma cortisol concentrations. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf) 82 (4), 557–561. doi:10.1111/cen.12653

Khan D., Ansar A. S. (2016). The immune system is a natural target for estrogen action: opposing effects of estrogen in two prototypical autoimmune diseases. Front. Immunol. 6, 635. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00635

Khush K. K., Kubo J. T., Desai M. (2012). Influence of donor and recipient sex mismatch on heart transplant outcomes: analysis of the international society for heart and lung transplantation registry. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 31 (5), 459–466. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2012.02.005

Kuhnz W., Gansau C., Mahler M. (1993). Pharmacokinetics of estradiol, free and total estrone, in young women following single intravenous and oral administration of 17 beta-estradiol. Arzneimittelforschung 43 (9), 966–973.

Larsson-Cohn U. (1985). Some aspects of the endocrinology of the climacterium. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. Suppl. 132, 13–14. doi:10.3109/00016348509157021

Peacock K., Carlson K., Ketvertis K. M. (2025). “Menopause. 2023 Dec 21,” in StatPearls (Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing).

Purdy R. H., Morrow A. L., Moore P. H., Paul S. M. (1991). Stress-induced elevations of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptoractive steroids in the rat brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88, 4553–4557. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.10.4553

Rebolledo R. A., Hoeksma D., Hottenrott C. M., Bodar Y. J., Ottens P. J., Wiersema-Buist J., et al. (2016). Slow induction of brain death leads to decreased renal function and increased hepatic apoptosis in rats. J. Transl. Med. 14 (1), 141. doi:10.1186/s12967-016-0890-0

Ricardo-da-Silva F. Y., Correia C. J., Vidal-Dos-Santos M., da Anunciação L. F., Coutinho E., Silva R. S., et al. (2020). Treatment with 17β-estradiol protects donor heart against brain death effects in female rat. Transpl. Int. 33 (10), 1312–1321. doi:10.1111/tri.13687

Ricardo-da-Silva F. Y., Armstrong-Jr R., Vidal-Dos-Santos M., Correia C. J., Coutinho E., Silva R. D. S., et al. (2021a). Long-term lung inflammation is reduced by estradiol treatment in brain dead female rats. Clin. (Sao Paulo) 76, e3042. doi:10.6061/clinics/2021/e3042

Ricardo-da-Silva F. Y., Vidal-Dos-Santos M., Correia C. J., Anunciação L. F., Coutinho E., Silva R. D. S., et al. (2021b). Protective role of 17β-estradiol treatment in renal injury on female rats submitted to brain death. Ann. Transl. Med. 9 (14), 1125. doi:10.21037/atm-21-1408

Ricardo-da-Silva F. Y., Armstrong-Jr R., Ramos M. M. A., Vidal-Dos-Santos M., Jesus Correia C., Ottens P. J., et al. (2024). Male versus female inflammatory response after brain death model followed by ex vivo lung perfusion. Biol. Sex. Differ. 15 (1), 11. doi:10.1186/s13293-024-00581-8

Simão R. R., Ferreira S. G., Kudo G. K., Armstrong J. R., Silva L. F., Sannomiya P., et al. (2016). Sex differences on solid organ histological characteristics after brain death1. Acta Cir. Bras. 31 (4), 278–285. doi:10.1590/S0102-865020160040000009

Spratt D. I., Longcope C., Cox P. M., Bigos S. T., Wilbur-Welling C. (1993). Differential changes in serum concentrations of androgens and estrogens (in relation with cortisol) in postmenopausal women with acute illness. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 76 (6), 1542–1547. doi:10.1210/jcem.76.6.8501162

Tan J. C., Kim J. P., Chertow G. M., Grumet F. C., Desai M. (2012). Donor-recipient sex mismatch in kidney transplantation. Gend. Med. 9 (5), 335–347.e2. doi:10.1016/j.genm.2012.07.004

Taraborrelli S. (2015). Physiology, production and action of progesterone. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 94 (Suppl. 161), 8–16. doi:10.1111/aogs.12771

van der Veen A., van Faassen M., de Jong W. H. A., van Beek A. P., Dijck-Brouwer D. A. J., Kema I. P. (2019). Development and validation of a LC-MS/MS method for the establishment of reference intervals and biological variation for five plasma steroid hormones. Clin. Biochem. 68, 15–23. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2019.03.013

van Zanden J. E., Rebolledo R. A., Hoeksma D., Bubberman J. M., Burgerhof J. G., Breedijk A., et al. (2020). Rat donor lung quality deteriorates more after fast than slow brain death induction. PLoS One 15 (11), e0242827. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0242827

Vidal-Dos-Santos M., Armstrong-Jr R., van Zil M., Ricardo-da-Silva F. Y., da Anunciação L. F., de Assis Ramos M. M., et al. (2025). Sex differences in kidney and lung status in an animal model of brain death. Clin. (Sao Paulo) 80, 100623. doi:10.1016/j.clinsp.2025.100623

Keywords: hormones, brain death, estradiol, progesterone, cortisol, testosterone, sex, age

Citation: de Assis Ramos MM, Ricardo-da-Silva FY, Vidal-dos-Santos M, Vos MJ, Ottens PJ, Nieuwenhuijs-Moeke GJ, Correia CJ, Bakker SJL, Moreira LFP, Leuvenink H, Breithaupt-Faloppa AC and for TransplantLines investigators (2025) Evaluation of donor’s hormonal profile according to sex and age. Front. Physiol. 16:1676624. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2025.1676624

Received: 30 July 2025; Accepted: 15 October 2025;

Published: 19 November 2025.

Edited by:

Christina Maria Pabelick, Mayo Clinic, United StatesReviewed by:

Sara Assadiasl, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, IranMuhammad Adil Malik, Central South University, China

Copyright © 2025 de Assis Ramos, Ricardo-da-Silva, Vidal-dos-Santos, Vos, Ottens, Nieuwenhuijs-Moeke, Correia, Bakker, Moreira, Leuvenink, Breithaupt-Faloppa and for TransplantLines investigators. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: A. C. Breithaupt-Faloppa, YW5hLmJyZWl0aGF1cHRAaGMuZm0udXNwLmJy

M. M. de Assis Ramos

M. M. de Assis Ramos F. Y. Ricardo-da-Silva

F. Y. Ricardo-da-Silva M. Vidal-dos-Santos

M. Vidal-dos-Santos M. J. Vos

M. J. Vos P. J. Ottens2

P. J. Ottens2 C. J. Correia

C. J. Correia S. J. L. Bakker

S. J. L. Bakker L. F. P. Moreira

L. F. P. Moreira H. Leuvenink

H. Leuvenink A. C. Breithaupt-Faloppa

A. C. Breithaupt-Faloppa