- 1Department of Rehabilitation Medicine of the First Hospital of Lanzhou university, Lanzhou, Gansu, China

- 2The Second Clinical Medical School, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China

Objective: Lower back pain (LBP) is the leading cause of disability worldwide. This study evaluates the pain relief and functional benefits of exercise interventions for affected individuals to inform clinical practice.

Methods: We searched nine electronic databases for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that examined exercise interventions for LBP.

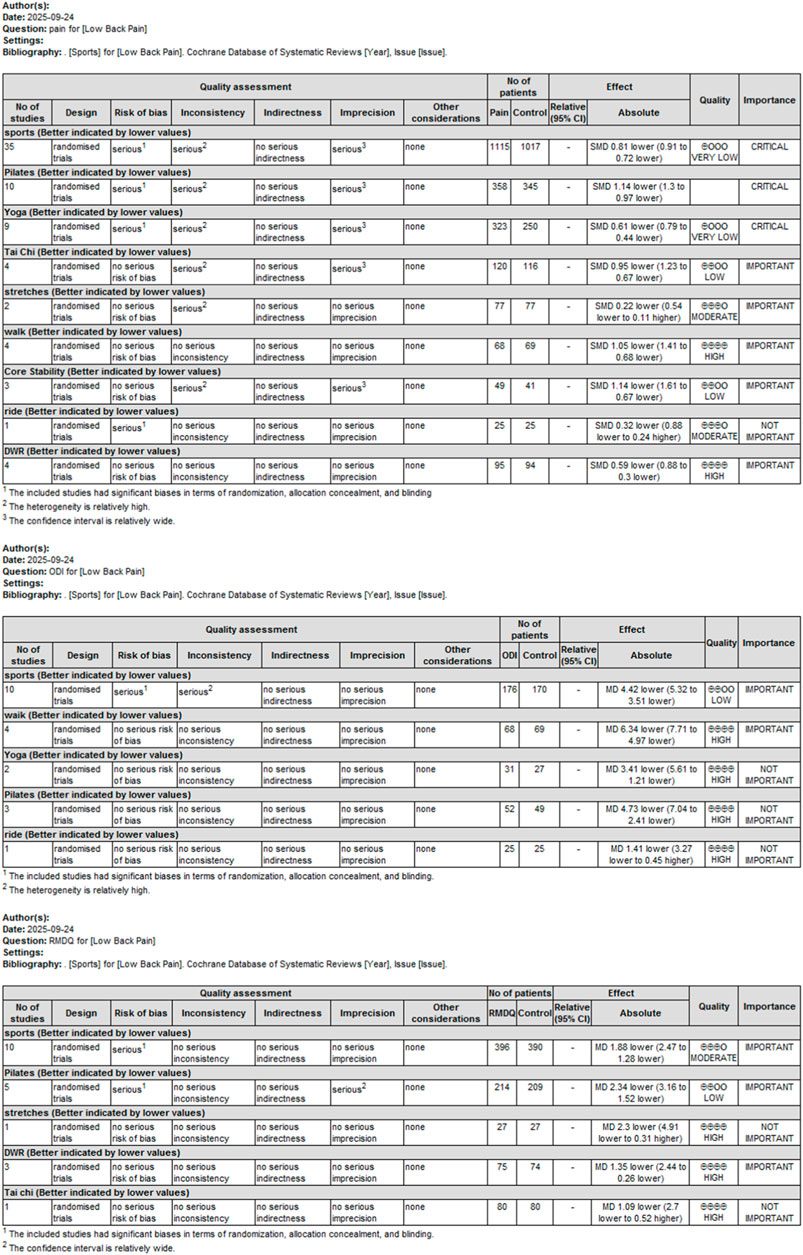

Results: We included 35 RCTs (n = 2,132). Exercise interventions were categorized into eight types: Pilates, yoga, core training, tai chi, walking, stretching, cycling, and deep-water running. Compared to usual care or other types of pain management interventions, exercise interventions demonstrated a significant overall difference in reducing pain (SMD = −0.81, 95% CI −0.91, −0.72; 17.31, P < 0.001). Subgroup analysis revealed that tai chi (SMD = −0.95), walking (MD = −1.05), and Pilates (MD = −1.14) exhibited the most significant analgesic effects. Regarding functional disability improvement, assessment using the Oswestry Disability Index showed significant efficacy for walking (MD = −6.34, P < 0.001), Pilates (MD = −4.73, P < 0.0001), and yoga (MD = −3.41, P = 0.002). However, assessment using the Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) indicated that only Pilates resulted in significant improvement (MD = −2.34, P < 0.001).

Conclusion: Pilates, yoga, and walking reduce pain and improve function in non-specific LBP. Tai chi and core-stability training also achieve significant analgesia. The evidence for stretching and cycling remains inconclusive.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251047326, identifier CRD420251047326.

Introduction

Lower back pain (LBP) has remained the leading cause of disability worldwide for more than three decades (Hartvigsen et al., 2018). According to the 2021 Global Burden of Disease Study, approximately 730 million people currently live with LBP, and this number is projected to exceed 840 million by 2050 (GBD 2021 Low Back Pain Collaborators, 2023). Chronic non-specific LBP (CNSLBP) accounts for more than 85% of cases, and its consequences extend beyond pain and functional impairment to encompass depression, anxiety, sleep disturbance, and diminished work capacity, thereby imposing significant socioeconomic costs on patients, families, and society (GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators, 2020). Despite advances in pharmacological, interventional, and surgical treatment, long-term outcomes remain modest, and such approaches may carry risks of adverse events or high financial burdens. Consequently, safe, cost-effective, and scalable treatment strategies are urgently needed (Oliveira et al., 2018).

Exercise therapy, owing to its non-invasive nature, accessibility, and wide-ranging health benefits, is consistently recommended as a first-line treatment for CNSLBP in major international guidelines (National Guideline C. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines, 2016; Qaseem et al., 2017).

Over the past two decades, a variety of exercise modalities have been investigated, including traditional approaches such as Pilates, yoga, and tai chi, as well as more contemporary forms such as core-stability training, aerobic walking, cycling, stretching, and deep-water running. However, the evidence base for these interventions has evolved unevenly. For example, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that Pilates provides clinically meaningful improvements in both pain and disability compared to minimal interventions (Patti et al., 2024), whereas yoga has also shown consistent, though more modest, benefits in pain reduction and functional outcomes. In contrast, evidence regarding tai chi and aquatic-based exercises remains sparse or inconclusive, and trials investigating aerobic walking or cycling have reported conflicting results (Fransen et al., 2015).

Previous syntheses have consistently confirmed that virtually any structured exercise attenuates pain and disability in adults with LBP (Hayden et al., 2021); nevertheless, the relative merit of competing protocols remains indeterminate. Similarly, Cochrane overviews comparing motor-control, resistance, Pilates, or yoga interventions (Vandestienne et al., 2022; Cai et al., 2022) report overlapping 95% confidence intervals for pain intensity and function but provide no hierarchy of benefit. Consequently, current guidelines (Tomita et al., 2022) issue generic “remain active” recommendations, leaving clinicians without an evidence-based algorithm to match exercise type to patient phenotype. A quantitative comparative synthesis that integrates both direct and indirect randomized evidence is therefore urgently required to clarify which movement strategy, if any, optimizes clinically relevant outcomes in adults with chronic LBP.

Given these limitations, there remains a critical need for an updated and comprehensive synthesis of the comparative efficacy of different exercise modalities. To address this gap, we conducted a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to evaluate and rank nine mainstream exercise interventions for pain and disability outcomes in adults with CNSLBP. Our aim is to provide clinicians with high-quality evidence to guide individualized, evidence-based exercise prescriptions for this prevalent and burdensome condition (Qaseem et al., 2017; Fernández-Rodríguez et al., 2022; Shiri et al., 2018).

Methods

Protocol and registration

The protocol was prospectively registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under ID CRD420251047326. The review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Page et al., 2021) and the Cochrane Handbook.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria comprised the following: (1) Population (P): adults (aged ≥18 and ≤80 years) in the general population diagnosed by a physician or rehabilitation specialist with CNSLBP (lasting ≥12 weeks), without concomitant organic lumbar spine pathology (infection, tumor, fracture, inflammatory spondyloarthritis, cauda equina syndrome, or radicular compression requiring surgical intervention); (2) Interventions (I): a course lasting at least 2 weeks and including at least six supervised or prescribed training sessions encompassing Pilates, yoga, core-stability training, tai chi, walking, stretching, cycling, or deep-water running. (3) Comparisons (C): usual care or other types of pain management interventions. (4) Study design: randomized controlled trials (RCTs). (5) Outcomes (O): pain intensity is assessed using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) or a 0–10 numerical rating scale (NRS). Functional status is evaluated using the Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) or the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI). (6) Language: articles written in English, Chinese, Spanish, French, German, or Portuguese.

Exclusion criteria comprised the following: (1) non-RCT studies; (2) studies with inaccessible full texts; (3) conference abstracts, reviews, animal experiments, or duplicate publications.

Literature search

A comprehensive search was performed across nine Chinese and English databases: CNKI, VIP, Wanfang Data Knowledge Service Platform, SINOMED, PubMed, Web of Science, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, and Embase. The search strategy combined subject terms and free-text words to optimize retrieval efficiency, including keywords such as “walking,” “yoga,” “tai chi,” “Pilates,” “lower back pain,” “core strengthening,” and “deep-water running.” The search timeframe was from the inception of each database to May 2025. Additionally, references of included studies were supplemented for retrieval. The search process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Quality assessment of literature

The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (Version 6.0) was used to evaluate the quality of the RCTs, covering domains including random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, completeness of outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. Each domain was carefully assessed as “high risk of bias,” “some concerns,” or “low risk of bias” based on predefined criteria. Two reviewers independently evaluated the risk of bias for each study; any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (GWB and WPR) independently extracted data from every included RCT. Disagreements were first resolved by re-checking the original publication and, if necessary, adjudication by a third reviewer. Extracted variables comprised bibliographic details, participant characteristics, sample size, mean age, intervention components (type, frequency, intensity, duration, delivery mode, and interveners), follow-up length, outcome measures (VAS, NRS, ODI, RMDQ, etc.), and key results. When primary outcome data (means, standard deviations, or event counts) were missing or presented only in graphs, we attempted to contact the corresponding author by e-mail (up to two reminders at 2 week intervals). Where no response was received, we used established statistical methods (Hozo (2005) for medians/ranges; Wan (2014) for inter-quartile ranges) to estimate missing statistics; all imputations are flagged in the evidence tables and sensitivity analyses were performed to assess their impact.

Data synthesis and analysis

All eligible studies are summarized in Table 1. For analysis, data extracted from included publications were imported into Review Manager (RevMan) 5.4 software. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, where values of 25%, 50%, and 75% indicated low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. A random-effects model was used for data with high heterogeneity; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was applied. For the effects of different exercises on pain and dysfunction, weighted mean differences (WMD) were calculated if outcomes were measured using the same scales or indicators. If different scales or indicators were used across trials, standardized mean differences (SMD) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were applied. Subgroup analyses were performed to explore potential sources of heterogeneity. In stratified meta-analyses, data from the literature were divided into subgroups based on intervention types (Pilates, yoga, core-stability exercises, tai chi, walking, stretching, cycling, and deep-water running). If the combined results showed high heterogeneity, the effect size and 95% CI of each study were reported with a narrative description. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Funnel plots were used to examine the included literature to detect publication bias. Certainty of evidence was rated with the GRADE 4.0 approach. Each outcome started at “high” certainty and was downgraded for risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, or publication bias. Final grades were “high,” “moderate,” “low,” or “very low”.

Results

Search results

A total of 8,445 potential studies were retrieved, with 1,505 duplicate studies excluded. After screening titles and abstracts, 48 studies were selected, of which 14 were excluded due to insufficient raw data and high risk of bias, leaving 35 studies eligible for inclusion (Table 1). The sample sizes of these 35 RCTs ranged from 8 to 127 participants. All 35 studies were published in English.

Research characteristics

Interventions in the experimental groups were categorized into eight types: Pilates (Tottoli et al., 2024; Cruz-Díaz et al., 2017; Miyamoto et al., 2018; Batıbay et al., 2021; Asik and Sahbaz, 2025; Silva et al., 2018; Miyamoto et al., 2013; Mazloum et al., 2018; Natour et al., 2015; Gladwell et al., 2006) (n = 10), yoga (Tekur et al., 2012; Metri et al., 2023; Ulger et al., 2023; Oz and Ulger, 2024; Williams et al., 2005; Nambi et al., 2014; Kuvačić et al., 2018; Saper et al., 2017; Neyaz et al., 2019) ((n = 9), core-stability exercises (Zuo et al., 2024; Zou et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019) (n = 3), tai chi (Zou et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019; Hall et al., 2011; Yan et al., 2022) (n = 4), walking (Raza et al., 2023; Alzahrani et al., 2021; Ahmad et al., 2023; Yilmaz Yelvar et al., 2017) (n = 4), stretching (Prado et al., 2021; Turci et al., 2023) (n = 2), cycling (Elabd and Elabd, 2024) (n = 1), and deep-water running (Carvalho et al., 2020; Nardin et al., 2022; Cuesta-Vargas et al., 2011; Cuesta-Vargas et al., 2012) (n = 4).

Risk of bias

Based on the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool, the studies included mostly showed a low risk of bias in terms of random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, and incomplete outcome data. However, there was a certain degree of uncertainty regarding selective reporting and other biases. Specifically, most studies performed well in random sequence generation and allocation concealment, but uncertainties existed in selective reporting, which might affect the reliability of the study results. Therefore, during the meta-analysis, these potential biases required appropriate adjustment and interpretation. The results of the risk-of-bias assessment are presented in Figures 2, 3.

Publication bias

As shown in Figure 4, the symmetrical funnel plot indicates no evidence of publication bias across the 35 included studies.

Evidence quality

The quality of evidence for the primary outcome (pain) was assessed using the GRADE 4.0 approach. Initially, the evidence started at a high level since all included studies were randomized controlled trials. Subsequently, downgrading factors were examined item by item (Figure 5).

Results of meta-analysis

Pain

A total of 35 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), involving 2,132 participants (1,115 in intervention groups and 1,017 in control groups), were included in the meta-analysis. The overall pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) for pain relief was −0.81 (95% CI: −0.91 to −0.72), indicating a significant analgesic effect of exercise interventions (Z = 17.31, P < 0.001). However, substantial heterogeneity was observed across studies (I2 = 86%, P < 0.001). Pilates (SMD = −1.14; 95% CI −1.30, −0.97), yoga (SMD = −0.61; 95% CI –0.79 to −0.44), tai chi (SMD = −0.95; 95% CI –1.23 to −0.67), and walking (SMD = −1.05; 95% CI –1.41 to −0.68) all demonstrated clinically and statistically significant analgesic effects. Yoga and deep-water running (DWR) produced moderate but significant benefits, whereas stretching and cycling showed no significant effect. Notably, walking demonstrated zero heterogeneity, suggesting highly reproducible benefits. These findings support prioritizing Pilates, core-stability, walking, and tai chi in clinical or community-based exercise prescriptions (Figure 6).

Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)

Ten RCTs examined the effect of exercise on the ODI. The pooled estimate was 9.53 (346 participants) with moderate heterogeneity (P < 0.001; I2 = 59%). Subgroup analyses showed that walking, Pilates, and yoga all significantly reduced ODI scores compared with control. Walking demonstrated the largest effect (MD = –6.34; 95% CI –7.71 to–4.97; P < 0.001). Cycling did not significantly improve disability levels (Figure 7).

Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ)

Overall across 14 randomized trials (786 participants), exercise interventions outperformed control conditions (MD = −1.88, 95% CI –2.47 to −1.28, P < 0.001; I2 = 21%). Pilates yielded the largest and most consistent benefit (five studies, n = 423, MD = −2.34, 95% CI −3.16 to −1.52, I2 = 15%), whereas DWR produced a moderate effect (three studies, n = 149, MD = −1.35, 95% CI −2.44 to −0.26). Stretching and tai chi did not achieve statistical significance. These findings support prioritizing Pilates in exercise prescriptions for this outcome; evidence for other modalities remains inconclusive (Figure 8).

Discussion

This study included 35 randomized controlled trials (n = 2,132), representing the first meta-analysis to compare the short-term efficacy of eight mainstream exercise programs on pain and functional impairment in chronic non-specific low-back pain (CNSLBP). The overall effect size SMD = −0.81 (95% CI −0.91 to −0.72) was not only statistically significant but also exceeded the MCID threshold based on VAS (Logroscino et al., 2005), indicating that the benefits of exercise intervention can be tangibly perceived by patients. At the subgroup level, walking, Pilates, and tai chi ranked the top three in analgesic effects. Notably, walking-related trials exhibited zero heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) and required minimal equipment, space, or specialized expertise, making it readily implementable in primary care, community rehabilitation, and even home settings. Functionally, walking yielded the greatest improvement in ODI (MD −6.34), while Pilates demonstrated the highest effect size on RMDQ (MD −2.34). Both exceeded their respective MCID thresholds (Atipas et al., 2022), indicating substantial relief from patients’ limitations in daily activities like lifting objects, prolonged standing, and bending. Although yoga reduced ODI scores, its lower confidence interval did not reach the MCID threshold, and its lack of procedural standardization suggests that it is better suited as an “enhancement module” within multimodal programs rather than a standalone core intervention. Stretching and cycling showed no clear benefits and should have their recommendation levels downgraded in clinical pathways. In summary, walking, Pilates, and tai chi can be considered first-line exercise prescriptions for LBP and are particularly suitable for resource-limited primary care settings or those requiring individualized rehabilitation.

Although all three top interventions fall under the category of low-impact aerobic exercise, their mechanisms for pain relief and functional recovery do not overlap. Walking induces rhythmic trunk sway, triggering alternating contractions of the lumbar multifidus and erector spinae muscles. This increases local blood flow shear stress, stimulating the release of beta-endorphins and serotonin. Simultaneously, periodic axial loading promotes intervertebral disc fluid exchange and reduces intrafibrous hydrostatic pressure, proving particularly effective for mechanically loaded pain (Ambrose and Golightly, 2015). Pilates emphasizes the triadic coordination of breathing–abdominal-pressure–pelvis, activating the transverse abdominis and diaphragm within a closed kinetic chain to create a pneumatic lumbar-support effect that instantly reduces segmental misalignment. Its movement sequences primarily focus on sagittal plane control, making it most suitable for improving the “lifting objects” and “prolonged standing” items in the ODI (Huxel Bliven and Anderson, 2013). Tai chi combines slow eccentric contractions with focused attention. fMRI studies confirm that it downregulates excitability in the insula-thalamic pain network, offering central analgesia benefits for patients with anxiety or catastrophic thinking (Srivatsa et al., 2018). Therefore, bedside decisions may rapidly triage patients based on pain phenotypes: walking is preferred for those with excessive mechanical load; Pilates is prioritized for segmental instability or early postoperative cases; tai chi is added for those with emotional distress or high fall risk.

Admittedly, the present meta-analysis is constrained by substantial heterogeneity (I2 > 85%) that permeates both the overall pool and the Pilates/yoga strata. This dispersion is neither stochastic nor purely methodological; rather, it stems from three converging layers. At the patient-level, discogenic, facet-joint, and sacroiliac subtypes display up to two-fold differences in segmental stiffness under combined shear–torsional loading, and such mechanical heterogeneity is known to modulate exercise responsiveness independently of symptom duration or body mass index (BMI) (Bisschop et al., 2013). At the trial-level, dosage descriptors (frequency, session length, and axial-load progression) were reported inconsistently, while the interchangeable use of VAS and NRS without study-specific conversion inflated the residual variance by approximately 8%–12%. At the evidence-level, 40% of eligible trials were not pre-registered, and the selective publication of positive findings shifted the pooled mean upward, widening the 95% prediction interval (Hohlfeld et al., 2024). Consequently, the summary effect should be interpreted as an upper-bound estimate of real-world benefit rather than a single “true” value. To mitigate this uncertainty, we recommend initiating a multi-center IPD consortium that integrates three-dimensional data from imaging, biomechanics, and psychology to construct a “pain phenotype-exercise prescription” predictive model. In addition, we recommend conducting a pragmatic stepped-wedge RCT to validate the cost-effectiveness of the two-stage “walking + Pilates” intervention at the community primary care level. Simultaneously, wearable sensors will monitor trunk-tilt angle, step frequency, and electromyography in real time to develop an AI-driven remote supervision platform to enable precise exercise dose titration. The ultimate goal is to advance exercise intervention from “experience-based exercise selection” to “data-driven dose determination,” providing an affordable, sustainable, and replicable precision rehabilitation pathway for LBP (Ganesh et al., 2023).

Conclusion

Building on our results, clinicians should match exercise to the patient with chronic low-back pain: brisk, equipment-free walking—uniformly effective and well tolerated—suits older or deconditioned adults whose pain and disability are most severe; augmenting walking with Pilates best supports those in the chronic stage who need greater core-stability and relapse prevention; tai chi, when supervised, provides a mind–body adjunct for well-coordinated individuals seeking additional analgesic and functional gains. However, many modalities rest on small, short-term trials, dose–response relationships remain undefined, and the influence of pain phenotypes and comorbidities is unknown. Future, large, high-quality randomized control trials should therefore validate understudied options such as cycling, delineate minimal effective and maximal tolerable doses through dose–response modeling, extend follow-up to capture recurrence and quality-of-life trajectories, and integrate imaging with biomechanical markers to clarify mechanisms to advance precision rehabilitation.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

XL: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. WG: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. PW: Data curation, Writing – original draft. JaH: Data curation, Writing – original draft. JnH: Data curation, Writing – original draft. XX: Data curation, Writing – original draft. WC: Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Gansu Western Sports Strong Province Construction Science and Technology Medical Joint Public Relations Project, Gansu Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No.: 21JR1RA065), The First Hospital of Lanzhou University Internal Research Fund (No.: ldyyyn2020-27), and the Gansu Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Gansu Provincial Traditional Chinese Medicine Research Project (No.: GZKP-2023-35).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmad A., Aldabbas M., Tanwar T., Iram I., Veqar Z. (2023). Effect of retro-walking on pain, functional disability, quality of life and sleep problems in patients with chronic low back pain. Physiother. Q. 31, 86–93. doi:10.5114/pq.2023.117448

Alzahrani H., Mackey M., Stamatakis E., Shirley D. (2021). Wearables-based walking program in addition to usual physiotherapy care for the management of patients with low back pain at medium or high risk of chronicity: a pilot randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 16, e0256459. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0256459

Ambrose K. R., Golightly Y. M. (2015). Physical exercise as non-pharmacological treatment of chronic pain: why and when. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 29, 120–130. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2015.04.022

Asik H. K., Sahbaz T. (2025). Preventing chronic low back pain: investigating the role of pilates in subacute management-a randomized controlled trial. Irish J. Med. Sci. 194, 949–956. doi:10.1007/s11845-025-03939-y

Atipas P., Pruksacholavit J., Pukrushpan P., Praneeprachachon P., Honglertnapakul W. (2022). Absence of bilateral multiple cyclovertical muscle insertions in a patient with Pfeiffer syndrome. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 59, e17–e19. doi:10.3928/01913913-20211206-01

Batıbay S., Külcü D. G., Kaleoğlu Ö., Mesci N. (2021). Effect of pilates mat exercise and home exercise programs on pain, functional level, and core muscle thickness in women with chronic low back pain. J. Orthop. Sci. 26, 979–985. doi:10.1016/j.jos.2020.10.026

Bisschop A., van Dieën J. H., Kingma I., van der Veen A. J., Jiya T. U., Mullender M. G., et al. (2013). Torsion biomechanics of the spine following lumbar laminectomy: a human cadaver study. Eur. Spine J. 22, 1785–1793. doi:10.1007/s00586-013-2699-3

Cai Y., Chen T., Liu J., Peng S., Liu H., Lv M., et al. (2022). Orthotopic versus allotopic implantation: Comparison of radiological and pathological characteristics. J. Magn. Reson Imaging 55, 1133–1140. doi:10.1002/jmri.27940

Carvalho R. G. S., Silva M. F., Dias J. M., Olkoski M. M., Dela Bela L. F., Pelegrinelli A. R. M., et al. (2020). Effectiveness of additional deep-water running for disability, lumbar pain intensity, and functional capacity in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomised controlled trial with 3-month follow-up. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 49, 102195. doi:10.1016/j.msksp.2020.102195

Cruz-Díaz D., Bergamin M., Gobbo S., Martínez-Amat A., Hita-Contreras F. (2017). Comparative effects of 12 weeks of equipment based and mat pilates in patients with chronic low back pain on pain, function and transversus abdominis activation. A randomized controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 33, 72–77. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2017.06.004

Cuesta-Vargas A. I., García-Romero J. C., Arroyo-Morales M., Diego-Acosta A. M., Daly D. J. (2011). Exercise, manual therapy, and education with or without high-intensity deep-water running for nonspecific chronic low back pain: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 90(7), 526–534. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e31821a71d0

Cuesta-Vargas A. I., Adams N., Salazar J. A., Belles A., Hazañas S., Arroyo-Morales M. (2012). Deep water running and general practice in primary care for non-specific low back pain versus general practice alone: randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rheumatol. 31, 1073–1078. doi:10.1007/s10067-012-1977-5

Elabd A. M., Elabd O. M. (2024). Effect of aerobic exercises on patients with chronic mechanical low back pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 37, 379–385. doi:10.1016/j.jbmt.2023.12.001

Fernández-Rodríguez R., Álvarez-Bueno C., Cavero-Redondo I., Torres-Costoso A., Pozuelo-Carrascosa D. P., Reina-Gutiérrez S., et al. (2022). Best exercise options for reducing pain and disability in adults with chronic low back pain: pilates, strength, core-based, and mind-body. A network meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 52, 505–521. doi:10.2519/jospt.2022.10671

Fransen M., McConnell S., Harmer A. R., Van der Esch M., Simic M., Bennell K. L. (2015). Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a cochrane systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 49, 1554–1557. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095424

Ganesh G. S., Khan A. R., Das S., Khan A. (2023). Prescription of therapeutic exercise for chronic low back pain management: a narrative review. Bull. Fac. Phys. Ther. 28, 47. doi:10.1186/s43161-023-00156-5

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators (2020). Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 396, 1204–1222. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

GBD 2021 Low Back Pain Collaborators (2023). Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990-2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 5, e316–e329. doi:10.1016/S2665-9913(23)00098-X

Gladwell V., Head S., Haggar M., Beneke R. (2006). Does a program of pilates improve chronic non-specific low back pain? J. Sport Rehabilitation 15, 338–350. doi:10.1123/jsr.15.4.338

Hall A. M., Maher C. G., Lam P., Ferreira M., Latimer J. (2011). Tai chi exercise for treatment of pain and disability in people with persistent low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res. Hob. 63, 1576–1583. doi:10.1002/acr.20594

Hartvigsen J., Hancock M. J., Kongsted A., Louw Q., Ferreira M. L., Genevay S., et al. (2018). What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet 391, 2356–2367. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30480-X

Hayden J. A., Ellis J., Ogilvie R., Malmivaara A., van Tulder M. W. (2021). Exercise therapy for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9, Cd009790. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009790.pub2

Hohlfeld A., Kredo T., Clarke M. (2024). A scoping review of activities intended to reduce publication bias in randomised trials. Syst. Rev. 13, 310. doi:10.1186/s13643-024-02728-5

Hozo S. P., Djulbegovic B., Hozo I. (2005). Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 5, 13. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-5-13

Huxel Bliven K. C., Anderson B. E. (2013). Core stability training for injury prevention. Sports Health 5, 514–522. doi:10.1177/1941738113481200

Kuvačić G., Fratini P., Padulo J., Antonio D. I., De Giorgio A. (2018). Effectiveness of yoga and educational intervention on disability, anxiety, depression, and pain in people with CLBP: a randomized controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 31, 262–267. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.03.008

Liu J., Yeung A., Xiao T., Tian X., Kong Z., Zou L., et al. (2019). Chen-style Tai Chi for individuals (aged 50 years old or above) with chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 517. doi:10.3390/ijerph16030517

Logroscino C. A., Pola E., Pola R., Tamburrelli F. C. (2005). Hydatid cyst of the spine. Lancet Infect. Dis. 5, 732. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70272-3

Mazloum V., Sahebozamani M., Barati A., Nakhaee N., Rabiei P. (2018). The effects of selective pilates versus extension-based exercises on rehabilitation of low back pain. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 22, 999–1003. doi:10.1016/j.jbmt.2017.09.012

Metri K. G., Raghuram N., Narayan M., Sravan K., Sekar S., Bhargav H., et al. (2023). Impact of workplace yoga on pain measures, mental health, sleep quality, and quality of life in female teachers with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a randomized controlled study. Work (Reading, Mass) 76, 521–531. doi:10.3233/WOR-210269

Miyamoto G. C., Costa L. O., Galvanin T., Cabral C. M. (2013). Efficacy of the addition of modified pilates exercises to a minimal intervention in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Phys. Ther. 93, 310–320. doi:10.2522/ptj.20120190

Miyamoto G. C., Franco K. F. M., van Dongen J. M., Franco Y. R. D. S., de Oliveira N. T. B., Amaral D. D. V., et al. (2018). Different doses of Pilates-based exercise therapy for chronic low back pain: a randomised controlled trial with economic evaluation. Br. J. Sports Med. 52, 859–868. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-098825

Nambi G. S., Inbasekaran D., Khuman R., Devi S., Jagannathan K. (2014). Changes in pain intensity and health related quality of life with Iyengar yoga in nonspecific chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled study. Int. J. Yoga 7, 48–53. doi:10.4103/0973-6131.123481

Nardin D. M. K., Stocco M. R., Aguiar A. F., Machado F. A., de Oliveira R. G., Andraus R. A. C. (2022). Effects of photobiomodulation and deep water running in patients with chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 37, 2135–2144. doi:10.1007/s10103-021-03443-6

National Guideline C. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines (2016). Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Natour J., Cazotti Lde A., Ribeiro L. H., Baptista A. S., Jones A. (2015). Pilates improves pain, function and quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 29, 59–68. doi:10.1177/0269215514538981

Neyaz O., Sumila L., Nanda S., Wadhwa S. (2019). Effectiveness of hatha yoga versus conventional therapeutic exercises for chronic nonspecific low-back pain. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 25, 938–945. doi:10.1089/acm.2019.0140

Oliveira C. B., Maher C. G., Pinto R. Z., Traeger A. C., Chenot J. F., et al. (2018). Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview. Eur. Spine J. 27, 2791–2803. doi:10.1007/s00586-018-5673-2

Oz M., Ulger O. (2024). Yoga, physical therapy and home exercise effects on chronic low back pain: pain perception, function, stress, and quality of life in a randomized trial. Percept. Mot. Ski. 131, 2216–2243. doi:10.1177/00315125241292235

Page M. J., McKenzie J. E., Bossuyt P. M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T. C., Mulrow C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj 372, n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71

Patti A., Thornton J. S., Giustino V., Drid P., Paoli A., Schulz J. M., et al. (2024). Effectiveness of pilates exercise on low back pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Disabil. Rehabil. 46, 3535–3548. doi:10.1080/09638288.2023.2251404

Prado É. R. A., Meireles S. M., Carvalho A. C. A., Mazoca M. F., Motta Neto A. D. M., Barboza Da Silva R., et al. (2021). Influence of isostretching on patients with chronic low back pain. A randomized controlled trial. Physiother. Theory Pract. 37, 287–294. doi:10.1080/09593985.2019.1625091

Qaseem A., Wilt T. J., McLean R. M., Forciea M. A., Denberg T. D. (2017). Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American college of physicians. Ann. Intern Med. 166, 514–530. doi:10.7326/M16-2367

Raza T., Riaz S., Ahmad F., Shehzadi I., Ijaz N., Ali S. (2023). Investigating the effects of retro walking on pain, physical function, and flexibility in chronic non-specific low back pain. Iran. Rehabilitation Journal 21, 309–317. doi:10.32598/irj.21.2.1880.1

Saper R. B., Lemaster C., Delitto A., Sherman K. J., Herman P. M., Sadikova E., et al. (2017). Yoga, physical therapy, or education for chronic low back pain: a randomized noninferiority trial. Ann. Intern Med. 167, 85–94. doi:10.7326/M16-2579

Shiri R., Coggon D., Falah-Hassani K. (2018). Exercise for the prevention of low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. Am. J. Epidemiol. 187, 1093–1101. doi:10.1093/aje/kwx337

Silva P. H. B., Silva D. F., Oliveira J. K. S., Oliveira F. B. (2018). The effect of the pilates method on the treatment of chronic low back pain: a clinical, randomized, controlled study. BrJP 1, 21–28. doi:10.5935/2595-0118.20180006

Srivatsa U. N., Danielsen B., Amsterdam E. A., Pezeshkian N., Yang Y., Nordsieck E., et al. (2018). CAABL-AF (California study of ablation for atrial fibrillation): mortality and stroke, 2005 to 2013. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 11, e005739. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.117.005739

Tekur P., Nagarathna R., Chametcha S., Hankey A., Nagendra H. R. (2012). A comprehensive yoga programs improves pain, anxiety and depression in chronic low back pain patients more than exercise: an RCT. Complement. Ther. Med. 20, 107–118. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2011.12.009

Tomita Y., Yamamoto Y., Tsuchiya N., Kanayama H., Eto M., Miyake H., et al. (2022). Avelumab first-line maintenance plus best supportive care (BSC) vs BSC alone for advanced urothelial carcinoma: JAVELIN bladder 100 Japanese subgroup analysis. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 383–395. doi:10.1007/s10147-021-02067-8

Tottoli C. R., Ben J., da Silva E. N., Bosmans J. E., van Tulder M., Carregaro R. L. (2024). Effectiveness of pilates compared with home-based exercises in individuals with chronic non-specific low back pain: randomised controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 38, 1495–1505. doi:10.1177/02692155241277041

Turci A. M., Nogueira C. G., Nogueira Carrer H. C., Chaves T. C. (2023). Self-administered stretching exercises are as effective as motor control exercises for people with chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomised trial. J. Physiother. 69, 93–99. doi:10.1016/j.jphys.2023.02.016

Ulger O., Oz M., Ozel Asliyuce Y. (2023). The effects of yoga and stabilization exercises in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized crossover study. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 37, E59–e68. doi:10.1097/HNP.0000000000000593

Vandestienne M., Joffre J., Lemarié J., Ait-Oufella H. (2022). Role of TREM-1 in cardiovascular diseases. Med. Sci. Paris. 38, 32–37. doi:10.1051/medsci/2021242

Wan X., Wang W., Liu J., Tong T. (2014). Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 14, 135. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-14-135

Williams K. A., Petronis J., Smith D., Goodrich D., Wu J., Ravi N., et al. (2005). Effect of iyengar yoga therapy for chronic low back pain. Pain 115, 107–117. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.016

Yan Z. W., Yang Z., Yang J., Chen Y. F., Zhang X. B., Song C. L. (2022). Tai Chi for spatiotemporal gait features and dynamic balancing capacity in elderly female patients with non-specific low back pain: a six-week randomized controlled trial. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 35, 1311–1319. doi:10.3233/BMR-210247

Yilmaz Yelvar G. D., Çırak Y., Dalkılınç M., Parlak Demir Y., Guner Z., Boydak A. (2017). Is physiotherapy integrated virtual walking effective on pain, function, and kinesiophobia in patients with non-specific low-back pain? Randomised controlled trial. Eur. Spine J. 26, 538–545. doi:10.1007/s00586-016-4892-7

Zou L., Zhang Y., Liu Y., Tian X., Xiao T., Liu X., et al. (2019). The effects of Tai Chi Chuan versus core stability training on lower-limb neuromuscular function in aging individuals with non-specific chronic lower back pain. Medicina (Kaunas) 55, 60. doi:10.3390/medicina55030060

Keywords: low-back pain, exercise intervention, meta-analysis, rehabilitation, pain relief

Citation: Liu X, Gao W, Wu P, Huang J, Han J, Xu X and Chen W (2026) Effects of different exercise interventions on lower back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 16:1694330. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2025.1694330

Received: 28 August 2025; Accepted: 26 November 2025;

Published: 06 January 2026.

Edited by:

Cíntia França, Interactive Technologies Institute (ITI), PortugalReviewed by:

Oleksandr P. Romanchuk, Lesya Ukrainka Volyn National University, UkraineAntonino Patti, University of Palermo, Italy

Copyright © 2026 Liu, Gao, Wu, Huang, Han, Xu and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wanqiang Chen, NTMxNTU1NDNAcXEuY29t

Xingchi Liu

Xingchi Liu Wenbo Gao

Wenbo Gao Peirun Wu

Peirun Wu Jiawang Huang

Jiawang Huang Jingjing Han

Jingjing Han Xiuli Xu

Xiuli Xu Wanqiang Chen

Wanqiang Chen

![Forest plot showing the mean difference between experimental and control groups across various studies on interventions like Pilates, stretches, DWR, and Tai Chi. Each study's mean, standard deviation, and weight are listed, with confidence intervals illustrated by horizontal lines, and diamond shapes represent overall effects. The combined mean difference favors the experimental group with a total mean difference of -1.88, 95% CI [-2.47, -1.28].](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1694330/fphys-16-1694330-HTML/image_m/fphys-16-1694330-g008.jpg)