Introduction

In chickens, the anterior pituitary gland produces the same palette of hormones seen across the vertebrates:

• Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and β-endorphin

• Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

• Growth hormone (GH)

• Luteinizing hormone (LH)

• Prolactin

• Thyrotropin (TSH)

• Neuropeptides, e.g.,

◦ Met-enkephalin

◦ Relaxin 3 (Lv et al., 2022)

This discussion focuses on contributions of the author and his collaborators with comments on what is still not known.

Control of GH release and synthesis

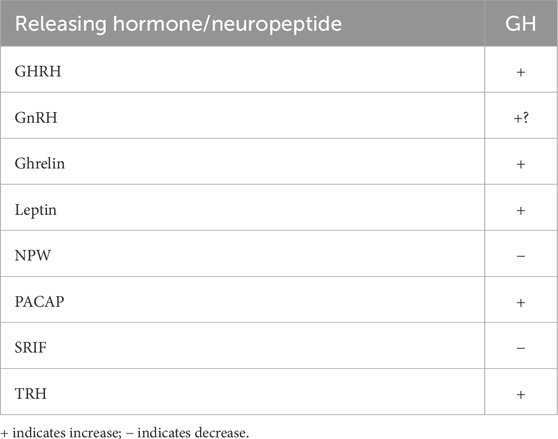

Chicken somatotrophs respond to GH-releasing hormone (GHRH) and some neuropeptides. Intra-cellular concentrations of calcium ions in somatotrophs are increased by GHRH, thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) (3/4 of somatotrophs), pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide (85% of somatotrophs), leptin (51%), gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) (40%), and ghrelin (21%) (Scanes et al., 2007). Table 1 summarizes the neuropeptides that influence the release of GH (reviewed: Scanes, 2022). Some neuropeptides affect the release of more than one hormone. For instance, neuropeptide W decreases the secretion of GH, prolactin, and ACTH in chickens (Bu et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2022). What are still unknown are the following:

• Why there are multiple stimulatory and inhibitory factors?

• How pituitary cells influence the functioning of others?

• What the role of folliculostellate cells is?

These produce growth factors/hormones including annexin 1, fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), leptin, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and these presumably exert paracrine effects (Zhang et al., 2021).

Table 1. Summary of the hypothalamic releasing hormones/neuropeptides influencing the secretion of GH (based on discussions in Scanes, 2022).

GH isoforms

There are multiple forms of GH in the chicken pituitary gland:

• Monomer (40%)

• Glycosylated (16%)

• Dimer (14%)

• 15–16 kDa sub-monomeric isoform (16%) (Luna et al., 2005)

The sub-monomeric isoform of GH predominates in immune tissues (Luna et al., 2005) and retinal ganglion cells in chickens (Baudet et al., 2003).

GH and growth

The hypothalamo-pituitary GH–insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) axis exists in chickens and other birds. GH increases growth in hypophysectomized young chickens (King and Scanes, 1986). Growth is reduced in sex-linked dwarf chickens with a mutation(s) in the GH receptor gene (Burnside et al., 1991). Plasma concentrations of IGF-1 are reduced in hypophysectomized young chickens and restored by GH treatment (Huybrechts et al., 1985). GH increases IGF-1 release from chick hepatocytes (Houston and O’Neill, 1991) and in adult chickens (Radecki et al., 1997). The mechanism for GH’s effect on growth is mediated via Janus kinase (JAK)-2 (Zhou et al., 2005). Studies addressing the question as to whether GH increases growth in intact broilers are at best equivocal (Leung et al., 1986; Vasilatos-Younken et al., 1988; Cogburn et al., 1989; Scanes et al., 1990).

GH and thyroid hormones

GH decreases hepatic deiodination of triiodothyronine (T3) in young chickens (Darras et al., 1992) with optimal circulating concentrations of T3 essential for growth. GH-receptor-deficient dwarf chickens have reduced plasma concentrations of T3 (Scanes et al., 1983).

GH and lipolysis

Mammalian and avian GH stimulates in vitro lipolysis (glycerol release from adipose tissue explants) (Campbell and Scanes, 1985) and inhibits glucagon-induced lipolysis (Campbell and Scanes, 1987). A GH antagonist prevents GH’s effect on lipolysis per se but unexpectedly retains full activity in suppressing glucagon-induced lipolysis (Campbell et al., 1993). Moreover, reptilian, amphibian, and fish GH lacks lipolytic activity but inhibits glucagon-induced lipolysis (Campbell et al., 1991). What are not known are the following:

• Are the effects of GH physiologically relevant?

• Are these direct effects on adipocytes, or are these effects mediated through other cell types present in adipose tissue, such as endothelial cells and macrophages, followed by paracrine effects of cytokines or other neuropeptides?

The lipolytic effect is probably mediated through JAK-2 based on studies in mice (Shi et al., 2014). However, the mechanism for anti-lipolytic effects is yet to be determined.

GH and reproduction

Administration of GH to laying hens increases shell thickness (Donoghue et al., 1990); this may be due to effects on the oviduct. This observation was followed by reports of oviductal and ovarian effects of GH. For instance, GH increases progesterone release from large yellow follicles (Hrabia et al., 2014a). GH decreases mucosal apoptosis in the oviduct but increases the expression of a specific gene (Hrabia et al., 2014b; Socha et al., 2017). Moreover, GH is present in the testes and ovary of chickens (Luna et al., 2014). There are associations between GH polymorphisms and egg production (Su et al., 2014).

Stress and GH

Stress affects GH levels in post-hatch chickens. Plasma concentrations of GH were depressed following challenge with ACTH (Davison et al., 1980). Plasma concentrations of GH are also decreased by epinephrine (Harvey and Scanes, 1978) and morphine (Harvey and Scanes, 1987). Heat stress did not affect plasma concentrations of GH in young chickens but depressed hepatic expression of the GHR (Uyanga et al., 2022). Corticosterone induces somatotrophs in chick embryos (e.g., Bossis and Porter, 2000). Plasma concentrations of GH are increased by nutritional deprivation such as withholding feed or feeding a protein-deficient diet (Buonomo et al., 1982); the latter being presumed to be due to dietary stress depressing negative feedback for T3 and IGF-1.

GH and the brain

Both GH- and prolactin-containing neurons are present within avian brains (Ramesh et al., 2000). Chick embryo retinal ganglion cells express GH (reviewed: Harvey et al., 2003; Harvey et al., 2012). Moreover, GH exerts a neuroprotective role in reducing apoptosis of retinal ganglion cells (Sanders et al., 2005). In vitro, GH depresses apoptosis and expression of caspase-3 and apoptosis-inducing factor-1 in neural retina explants from chick embryos (Harvey et al., 2006). Apoptosis in retinal ganglion cells is increased by antisera to GH in ovo, supporting a role for locally produced GH in regulating retinal apoptosis (Sanders et al., 2005). In an avian model for ischemic stroke, GH exerts a neuroprotective effect on cultured chick embryo hippocampal cells exposed to oxygen–glucose deprivation (Olivares-Hernández et al., 2021). Moreover, GH influences neurite development in the inner ear with increases in extension and branching of neurites in chick embryos (Gabrielpillai et al., 2018). Information on the underlying mechanism(s) for neuronal effects of GH is lacking.

GH and angiogenesis

Chick embryo chorioallantoic membranes (CAMs) are useful for examining the effects of hormones and growth factors on angiogenesis. Clapp et al. (1993) reported that “the 16-kilodalton N-terminal fragment of human prolactin is a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis” using chick embryo CAMs. In contrast, the formation of blood vessels was stimulated by either an anterior pituitary tissue or GH (Gould et al., 1995). The signal transduction mechanism for these effects remains unclear.

Author contributions

CS: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author declares that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Baudet M.-L., Sanders E. J., Harvey S. (2003). Retinal growth hormone in the chick embryo. Endocrinology 144, 5459–5468. doi:10.1210/en.2003-0651

Bossis I., Porter T. E. (2000). Ontogeny of corticosterone-inducible growth hormone-secreting cells during chick embryonic development. Endocrinology 141, 2683–2690. doi:10.1210/endo.141.7.7554

Bu G., Lin D., Cui L., Huang L., Lv C., Huang S., et al. (2016). Characterization of neuropeptide B (NPB), neuropeptide W (NPW), and their receptors in chickens: evidence for NPW being a novel inhibitor of pituitary GH and prolactin secretion. Endocrinology 157, 3562–3576. doi:10.1210/en.2016-1141

Buonomo F. C., Griminger P., Scanes C. G. (1982). Effects of gradation in protein-calorie restriction on the hypothalo-pituitary-gonadal axis in young domestic fowl. Poult. Sci. 61, 800–803. doi:10.3382/ps.0610800

Burnside J., Liou S. S., Cogburn L. A. (1991). Molecular cloning of the chicken growth hormone receptor complementary deoxyribonucleic acid: mutation of the gene in sex-linked dwarf chickens. Endocrinology 128, 3183–3192. doi:10.1210/endo-128-6-3183

Campbell R. M., Scanes C. G. (1985). Lipolytic activity of purified pituitary and bacterially derived growth hormone on chicken adipose tissue in vitro. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 180, 513–517. doi:10.3181/00379727-180-42210

Campbell R. M., Scanes C. G. (1987). Growth hormone inhibition of glucagon and cAMP-induced lipolysis by chicken adipose tissue in vitro. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 184, 456–460. doi:10.3181/00379727-184-42500

Campbell R. M., Kawauchi H., Lewis U. J., Papkoff H., Scanes C. G. (1991). Comparison of lipolytic and antilipolytic activities of lower vertebrate growth hormones on chicken adipose tissue in vitro. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 197, 409–415. doi:10.3181/00379727-197-43275

Campbell R. M., Chen W. Y., Wiehl P., Kelder B., Kopchick J. J., Scanes C. G. (1993). A growth hormone (GH) analog that antagonizes the lipolytic effect but retains full insulin-like (antilipolytic) activity of GH. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 203, 311–316. doi:10.3181/00379727-203-43604

Clapp C., Martial J. A., Guzman R. C., Rentier-Delure F., Weiner R. I. (1993). The 16-kilodalton N-terminal fragment of human prolactin is a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. Endocrinology 133, 1292–1299. doi:10.1210/endo.133.3.7689950

Cogburn L. A., Liou S. S., Rand A. L., McMurtry J. P. (1989). Growth, metabolic and endocrine responses of broiler cockerels given a daily subcutaneous injection of natural or biosynthetic chicken growth hormone. J. Nutr. 119, 1213–1222. doi:10.1093/jn/119.8.1213

Darras V. M., Berghman L. R., Vanderpooten A., Kühn E. R. (1992). Growth hormone acutely decreases type III iodothyronine deiodinase in chicken liver. FEBS Lett. 310, 5–8. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(92)81133-7

Davison T. F., Scanes C. G., Harvey S., Flack I. H. (1980). The effect of an injection of corticotrophin on plasma concentrations of corticosterone, growth hormone and prolactin in two strains of domestic fowl. Br. Poult. Sci. 21, 287–293. doi:10.1080/00071668008416671

Donoghue D. J., Campbell R. M., Scanes C. G. (1990). Effect of biosynthetic chicken growth hormone on egg production in white leghorn hens. Poult. Sci. 69, 1818–1821. doi:10.3382/ps.0691818

Gabrielpillai J., Geissler C., Stock B., Stöver T., Diensthuber M. (2018). Growth hormone promotes neurite growth of spiral ganglion neurons. NeuroReport 29, 637–642. doi:10.1097/WNR.0000000000001011

Gould J., Aramburo C., Capdevielle M., Scanes C. G. (1995). Angiogenic activity of anterior pituitary tissue and growth hormone on the chick embryo chorio-allantoic membrane: a novel action of GH. Life Sci. 56, 587–594. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(94)00491-a

Harvey S., Scanes C. G. (1978). Effect of adrenaline and adrenergic active drugs on growth hormone secretion in immature cockerels. Experientia 34, 1096–1097. doi:10.1007/BF01915371

Harvey S., Scanes C. G. (1987). Opiate inhibition of growth hormone secretion in young chickens. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 65, 34–39. doi:10.1016/0016-6480(87)90219-x

Harvey S., Kakebeeke M., Murphy A. E., Sanders E. J. (2003). Growth hormone in the nervous system: autocrine or paracrine roles in retinal function? Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 81, 371–384. doi:10.1139/y03-034

Harvey S., Baudet M.-L., Sanders E. J. (2006). Growth hormone and cell survival in the neural retina: caspase dependence and independence. Neuroreport 17, 1715–1718. doi:10.1097/01.wnr.0000239952.22578.90

Harvey S., Lin W., Giterman D., El-Abry N., Qiang W., Sanders E. J. (2012). Release of retinal growth hormone in the chick embryo: local regulation? Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 176, 361–366. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2012.01.021

Houston B., O’Neill I. E. (1991). Insulin and growth hormone act synergistically to stimulate insulin-like growth factor-I production by cultured chicken hepatocytes. J. Endocrinol. 128, 389–393. doi:10.1677/joe.0.1280389

Hrabia A., Sechman A., Rzasa J. (2014a). Effect of growth hormone on basal and LH-stimulated steroid secretion by chicken yellow ovarian follicles. An in vitro study. Folia. Biol. (Krakow) 62, 313–319. doi:10.3409/fb62_4.313

Hrabia A., Leśniak-Walentyn A., Sechman A., Gertler A. (2014b). Chicken oviduct-the target tissue for growth hormone action: effect on cell proliferation and apoptosis and on the gene expression of some oviduct-specific proteins. Cell Tissue Res. 357, 363–372. doi:10.1007/s00441-014-1860-6

Huybrechts L. M., King D. B., Lauterio T. J., Marsh J., Scanes C. G. (1985). Plasma concentrations of somatomedin-C in hypophysectomized, dwarf and intact growing domestic fowl as determined by heterologous radioimmunoassay. J. Endocrinol. 104, 233–239. doi:10.1677/joe.0.1040233

King D. B., Scanes C. G. (1986). Effect of mammalian growth hormone and prolactin on the growth of hypophysectomized chickens. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 182, 201–207. doi:10.3181/00379727-182-42328

Leung F. C., Taylor J. E., Wien S., Van Iderstine A. (1986). Purified chicken growth hormone (GH) and a human pancreatic GH-releasing hormone increase body weight gain in chickens. Endocrinology 118, 1961–1965. doi:10.1210/endo-118-5-1961

Liu M., Bu G., Wan Y., Zhang J., Mo C., Li J., et al. (2022). Evidence for neuropeptide W acting as a physiological corticotropin-releasing inhibitory factor in male chickens. Endocrinology 163, bqac073. doi:10.1210/endocr/bqac073

Luna M., Martínez-Moreno C. G., Ahumada-Solórzano M. S., Harvey S., Carranza M., Arámburo C. (2014). Extrapituitary growth hormone in the chicken reproductive system. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 203, 60–68. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.02.021

Luna M., Barraza N., Berumen L., Carranza M., Pedernera E., Harvey S., et al. (2005). Heterogeneity of growth hormone immunoreactivity in lymphoid tissues and changes during ontogeny in domestic fowl. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 144, 28–37. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2005.04.007

Lv C., Zheng H., Jiang B., Ren Q., Zhang J., Zhang X., et al. (2022). Characterization of relaxin 3 and its receptors in chicken: evidence for relaxin 3 acting as a novel pituitary hormone. Front. Physiol. 13, 1010851. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.1010851

Olivares-Hernández J. D., Balderas-Márquez J. E., Carranza M., Luna M., Martínez-Moreno C. G., Arámburo C. (2021). Growth hormone (GH) enhances endogenous mechanisms of neuroprotection and neuroplasticity after oxygen and glucose deprivation injury (ogd) and reoxygenation (ogd/r) in chicken hippocampal cell cultures. Neural Plast. 2021, 9990166. doi:10.1155/2021/9990166

Radecki S. V., McCann-Levorse L., Agarwal S. K., Burnside J., Proudman J. A., Scanes C. G. (1997). Chronic administration of growth hormone (GH) to adult chickens exerts marked effects on circulating concentrations of insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I), IGF binding proteins, hepatic GH regulated gene I, and hepatic GH receptor mRNA. Endocrine 6, 117–124. doi:10.1007/BF02738954

Ramesh R., Kuenzel W. J., Buntin J. D., Proudman J. A. (2000). Identification of growth-hormone- and prolactin-containing neurons within the avian brain. Cell Tissue Res. 299, 371–383. doi:10.1007/s004419900104

Sanders E. J., Parker E., Aramburo C., Harvey S. (2005). Retinal growth hormone is an anti-apoptotic factor in embryonic retinal ganglion cell differentiation. Exp. Eye Res. 81, 551–560. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2005.03.013

Scanes C. G., Marsh J., Decuypere E., Rudas P. (1983). Abnormalities in the plasma concentration of thyroxine, triiodothyronine and growth hormone in sex-linked dwarf and autosomal dwarf white leghorn domestic fowl (Gallus domesticus). J. Endocrinol. 97, 127–135. doi:10.1677/joe.0.0970127

Scanes C. G., Peterla T. A., Kantor S., Ricks C. A. (1990). In vivo effects of biosynthetic chicken growth hormone on broiler-strain chickens. Growth, Dev. Aging 54, 95–106.

Scanes C. G., Glavaski-Joksimovic A., Johannsen S. A., Jeftinija S., Anderson L. L. (2007). Subpopulations of somatotropes with differing intracellular calcium concentration responses to secretagogues. Neuroendocrinol. 85, 221–231. doi:10.1159/000102968

Scanes C. G. (2022). “Pituitary gland,” in Sturkie's Avian Physiology 7th edition. Editors C. G. Scanes, and S. Dridi (New York: Academic Press), 759–814.

Shi S. Y., Luk C. T., Brunt J. J., Sivasubramaniyam T., Lu S. Y., Schroer S. A., et al. (2014). Adipocyte-specific deficiency of janus kinase (JAK) 2 in mice impairs lipolysis and increases body weight, and leads to insulin resistance with ageing. Diabetologia 57, 1016–1026. doi:10.1007/s00125-014-3185-0

Socha J. K., Sechman A., Mika M., Hrabia A. (2017). Effect of growth hormone on steroid concentrations and mRNA expression of their receptor, and selected egg-specific protein genes in the chicken oviduct during pause in laying induced by fasting. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 61, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.domaniend.2017.05.001

Su Y. J., Shu J. T., Zhang M., Zhang X. Y., Shan Y. J., Li G. H., et al. (2014). Association of chicken growth hormone polymorphisms with egg production. Genet. Mol. Res. 13, 4893–4903. doi:10.4238/2014.July.4.3

Uyanga V. A., Zhao J., Wang X., Jiao H., Onagbesan O. M., Lin H. (2022). Dietary L-citrulline modulates the growth performance, amino acid profile, and the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor axis in broilers exposed to high temperature. Front. Physiol. 13, 937443. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.937443

Vasilatos-Younken R., Cravener T. L., Cogburn L. A., Mast M. G., Wellenreiter R. H. (1988). Effect of pattern of administration on the response to exogenous pituitary-derived chicken growth hormone by broiler-strain pullets. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 71, 268–283. doi:10.1016/0016-6480(88)90255-9

Zhang J., Lv C., Mo C., Liu M., Wan Y., Li J., et al. (2021). Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis of chicken anterior pituitary: a bird's-eye view on vertebrate pituitary. Front. Physiol. 12, 562817. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.562817

Keywords: growth hormone, chicken, stress, lipolysis, growth

Citation: Scanes CG (2025) Growth hormone: lessons from chickens. Front. Physiol. 16:1705885. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2025.1705885

Received: 15 September 2025; Accepted: 24 October 2025;

Published: 21 November 2025.

Edited by:

Takeshi Ohkubo, Ibaraki University, JapanReviewed by:

Mohammad Bahry, University of Guelph, CanadaCopyright © 2025 Scanes. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Colin G. Scanes, Y2dzY2FuZXNAaWNsb3VkLmNvbQ==

Colin G. Scanes

Colin G. Scanes