- 1College of Exercise and Health, Shenyang Sport University, Shenyang, China

- 2Sports, Exercise and Brain Sciences Laboratory, Sports Coaching College, Beijing Sport University, Beijing, China

This literature review examines systematically the effects of Stroboscopic Visual Training (SVT) on cognitive function and motor performance in humans with an integrated focus on the underlying neural mechanism. Systematic searches were conducted in major databases, including PubMed and Web of Science, and stringent screening procedures were applied. As a result, 35 high-quality experimental studies were identified and selected for in-depth analysis. The findings indicate that SVT can effectively and significantly enhance the speed of visual information processing and optimize core cognitive functions such as the allocation of attention. In terms of athletic performance, multiple indicators show improvements with enhanced precision in hand-eye coordination and increased motor reaction capabilities. SVT demonstrates consistent and positive effects regardless of athletes’ skill levels. In-depth investigation into its mechanisms reveals that the effects are associated with intermittent visual occlusion, which can induce significant changes in neural plasticity, thereby influencing both cognitive and motor performance. Overall, SVT holds substantial potential as an effective intervention for enhancing cognitive and motor performance. However, current research is limited by insufficient diversity and representativeness in sample selection, a lack of standardized training protocols, and an inadequate exploration of the underlying neural mechanisms. Future studies should aim to optimize experimental design, expand research contexts, and utilize advanced neuroimaging techniques to further elucidate the mechanisms through which SVT exerts its effects. Such efforts will help to unlock the full application value of SVT in fields such as sports training and rehabilitation, providing a more robust scientific foundation for its widespread implementation.

1 Introduction

Vision plays a pivotal role in athletic performance (Bao et al., 2017; Lochhead et al., 2024b). Fine motor actions—such as executing a volleyball spike (Jafarzadehpur et al., 2007; Zhu et al., 2024), hitting a baseball (Higuchi et al., 2018; Klemish et al., 2018), or performing a basketball jump shot (Oudejans et al., 2005; Piras, 2024)—are heavily dependent on accurate visual input (Buscemi et al., 2024; Appelbaum and Erickson, 2018). The link between visual capabilities and motor performance is widely regarded as a critical factor in determining athletic success (Erickson, 2022; Laby and Appelbaum, 2021). In recent years, an increasing body of research has focused on enhancing athletic performance through visual-based interventions (Krigolson et al., 2015; Hadlow et al., 2018; Hülsdünker et al., 2018). Among these, SVT has emerged as a promising and increasingly studied technique within the domain of sports training (Carrolla et al., 2021; Jothi et al., 2025; Smith et al., 2024).

SVT involves the use of stroboscopic eyewear during athletic activities (Das et al., 2023; Lochhead et al., 2024a). By alternating between transparent and opaque phases at adjustable frequencies, these glasses regulate the amount and continuity of visual information available to the athlete, thereby engaging neural circuits involved in visual and cognitive processing (Koppelaar et al., 2019; Wilkins and Appelbaum, 2020; Wilkins and Gray, 2015). This controlled visual disruption compels athletes to make decisions and respond under conditions of intermittent visual input (Braly and DeLucia, 2020; Erickson, 2021; Luo et al., 2025), which is theorized to enhance visual processing efficiency, improve motor performance (Vasile and Stănescu, 2023; 2024), and potentially reduce injury risk (Gokeler et al., 2018; Uzlaşır et al., 2021). According to the “Sports Vision Pyramid” model proposed by Kirschen and Laby (2011) (Figure 1), Attaining “optimal motor performance,” as situated at the apex of the Sports Vision Pyramid, depends on the integrity and efficiency of underlying neuro-visual processing functions at the foundational levels. Although SVT interventions may vary in their implementation, they consistently aim to enhance sport-specific skills and optimize athletic performance by improving visual-perceptual processing (Elliott and Bennett, 2021; Jothi et al., 2025).

Figure 1. The Sports Vision Pyramid: A hierarchical model for athletic performance. The model proposes that on-field visual performance (apex) is built upon the neural integration of visual information (mid-layer), which itself processes inputs from fundamental visual sensory and mechanical skills (base layer).

Despite the demonstrated efficacy of stroboscopic vision in sports training, numerous questions remain unresolved. Indeed, the efficacy of SVT is modulated by multiple variables, including stroboscopic frequency (flashes per unit time), duty cycle (ratio of visual signal duration to cycle time), training duration, task specificity, and motor competence (Stănescu, 2021). However, current literature lacks standardized protocols for implementing and calibrating these variables across training paradigms.

This literature review systematically evaluates the effects of SVT on cognitive functions and motor performance, explores its underlying mechanisms, and analyzes key training parameters—including session frequency, duration, and stroboscopic rate—across various sports contexts and experimental conditions. It is anticipated that the findings from this review will facilitate the effective integration of SVT into athletic training and provide both theoretical insights and practical guidance for future research and performance enhancement.

2 Research methods

2.1 Literature search strategy

The design and reporting of this systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. To ensure comprehensiveness, a systematic search was conducted across multiple authoritative databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Ebsco. The search period ranged from the inception of each database to August 2024.

The search strategy was constructed based on the PICO framework and utilized Boolean operators to combine key terms. For example, the search strategy used in PubMed was as follows: (stroboscop*[Title/Abstract] OR “stroboscopic visual training” [Title/Abstract] OR “stroboscopic training” [Title/Abstract] OR “stroboscopic vision” [Title/Abstract] OR “stroboscopic glasses” [Title/Abstract] OR “shutter glasses” [Title/Abstract] OR “visual occlusion” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“Athletic Performance” [MeSH] OR “Sports” [MeSH] OR “Motor Skills” [MeSH] OR “Cognition” [MeSH] OR “Psychomotor Performance” [MeSH] OR “sports performance” [Title/Abstract] OR “motor performance” [Title/Abstract] OR “cognitive function” [Title/Abstract] OR “sports vision training” [Title/Abstract]).

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria for literature

2.2.1 Inclusion criteria

1. Population: Healthy human participants, with no restrictions on age, sex, or athletic proficiency.

2. Intervention: The primary intervention involved SVT. No restrictions were placed on intervention duration, session length, or stroboscopic frequency to allow for a comprehensive review of all existing protocols.

3. Study Design: Experimental studies, including randomized controlled trials and non-randomized trials.

4. Outcomes: Studies must report at least one objective measure of cognitive function or motor performance.

2.2.2 Exclusion criteria

1. Intervention: Studies that did not implement SVT as an intervention.

2. Animal studies; studies involving clinical populations with known cognitive or motor impairments.

3. Publication Type: Review articles, conference abstracts, commentaries, or duplicate publications.

2.3 Literature screening process and quality assessment

2.3.1 Study selection process

The literature screening process strictly adhered to the PRISMA guidelines, as detailed in Figure 2. The specific steps were as follows: Initially, 1,175 records were identified through database searching. After importing into the EndNote reference management software, 347 duplicate records were removed through both automated and manual processes. Subsequently, the titles and abstracts of the remaining 828 records were independently screened by two reviewers, leading to the exclusion of 562 records that did not meet the inclusion criteria. For the 266 records that passed the initial screening, the full texts were retrieved and reviewed, and then re-screened against the pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. During this full-text screening phase, 81 records were excluded for reasons including inability to retrieve the full text, non-experimental articles, ineligible study populations, interventions not involving SVT, or outcome indicators not meeting the criteria. Ultimately, 35 studies were included for qualitative analysis (Zwierko M. et al., 2023).

2.3.2 Risk of bias assessment

To assess the methodological quality of the included studies, the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool was employed. This assessment was conducted independently by two reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or, if necessary, by consulting a third senior researcher.

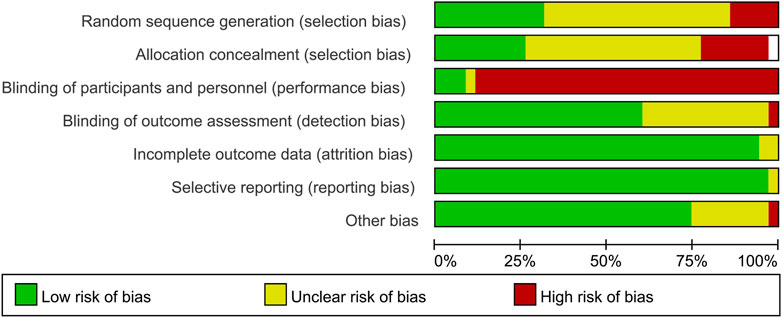

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool, with a summary of the results presented in Figure 3. Overall, the majority of studies demonstrated a low risk of bias in domains related to selection bias, such as random sequence generation and allocation concealment. However, a significant proportion of studies were judged as having a high risk of performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel), which is largely inherent to the nature of the SVT intervention. The risks of detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment) and reporting bias (selective reporting) were most frequently rated as unclear for a majority of the studies. Risks associated with attrition bias and other biases were generally low. This assessment indicates that the core quality of the evidence synthesized in this systematic review is acceptable, despite inherent limitations related to the intervention’s characteristics.

Figure 3. A bar chart summarizing the risk of bias for included studies across seven domains. Each bar represents the percentage of studies judged as low, unclear, or high risk for a specific domain. The majority of studies show low risk in “Random sequence generation”, “Allocation concealment”, “Incomplete outcome data”, and “Other bias”. In contrast, most studies have high risk in “Blinding of participants and personnel”. Judgments for “Blinding of outcome assessment” and “Selective reporting” are predominantly unclear.

3 Results

3.1 Data extraction and synthesis methods

3.1.1 Data extraction

A standardized data extraction form was developed. Two reviewers independently extracted key information from each included study, encompassing: (a) study characteristics (author, year, design); (b) participant profiles (sport, skill level); (c) SVT intervention parameters (frequency, duration, stroboscopic rate, duty cycle); (d) outcome measures related to cognitive function and motor performance; and (e) main findings.

3.1.2 Data categorization and synthesis

The extracted findings were categorized and synthesized by key outcome domains (e.g., information processing speed, visual attention, hand-eye coordination, motor reaction time). Within each domain, studies were systematically compared and contrasted to identify consistent patterns, divergent results, and the strength of the evidence. This narrative summary approach, presented in the following sections and summarized in Tables 1, 2, forms the basis for the conclusions drawn in this review. The conceptual model illustrating the mediating role of cognition (Figure 4) was developed to visually synthesize the central mechanism derived from this analytical process.

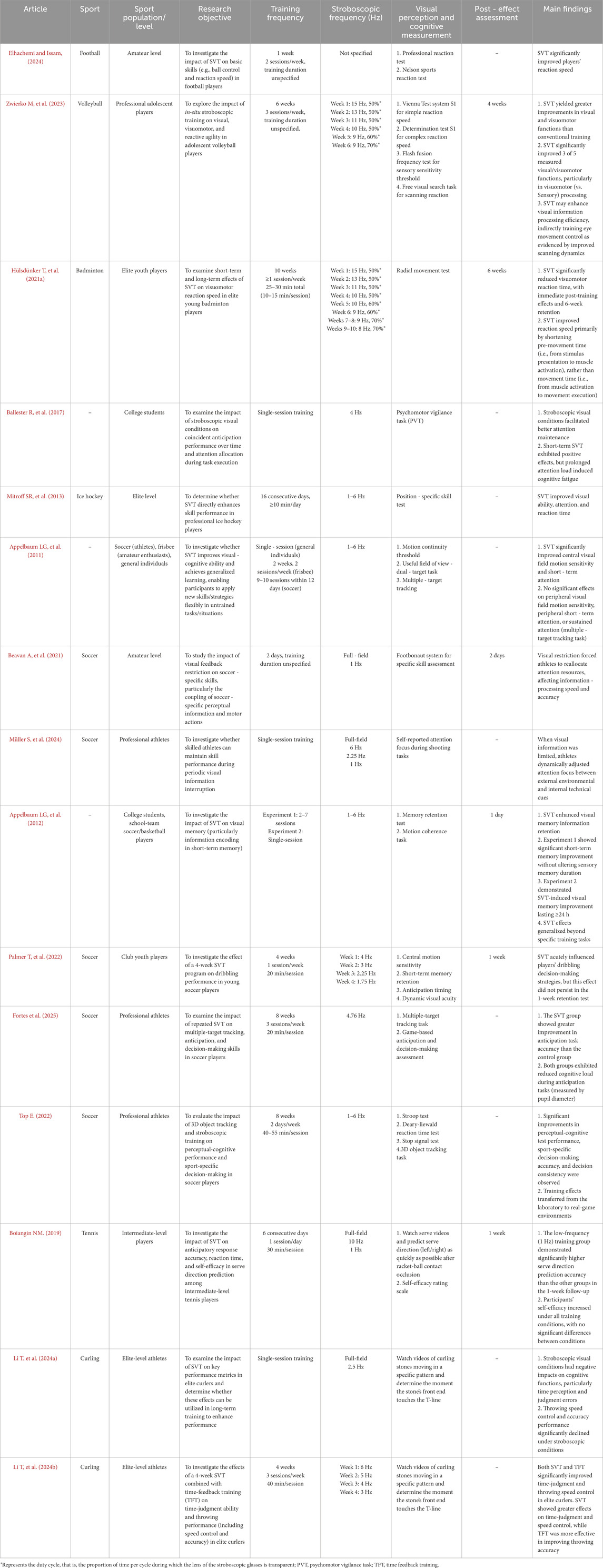

Table 1. Research protocols and main findings of the effects of stroboscopic visual training on cognitive function.

Table 2. Research protocols and main findings on the effects of stroboscopic visual training on motor performance.

Figure 4. The mediating role of cognition between Stroboscopic Visual Training (SVT) and motor performance. The model illustrates how SVT may primarily target cognitive functions, which in turn serve as the mechanism for improving specific motor skills.

3.2 Summary of research protocols

3.2.1 Overview of subjects included in the research

In the reviewed literature, the sample sizes of the included research subjects varied considerably. Most studies reported sample sizes of less than 40. Four studies had over 100 subjects, with two studies featuring 189 participants (Beavan et al., 2021; Fransen et al., 2017). Nine studies included fewer than 20 subjects, and two of them had less than 10 subjects, specifically 3 (Elhachemi and Issam, 2024) and 6 (Wilkins et al., 2018).

Regarding sports specializations, these studies predominantly covered football (9 studies), badminton (1 study), table tennis (1 study), volleyball (2 studies), tennis (2 studies), basketball (1 study), baseball (1 study), softball (1 study), rugby (1 study), ice hockey (1 study), and curling (2 studies).

Concerning the athletic levels of the subjects, the studies included amateurs, professionals, elites, top - level athletes, and university athletes, indicating the widespread application of this technology across different sports levels. Three studies that included subjects of varying sports levels pointed out that lower - level athletes have greater room for improvement (Edgerton, 2018; Ellison et al., 2020), while high - level athletes demonstrate more stable performance under stroboscopic intervention (stronger anti - interference ability) (Jendrusch et al., 2023).

3.2.2 Summary of intervention measures

All studies provided detailed reports on specific intervention measures and collected outcome - measure data at least once before and after the intervention. In terms of the duration of the intervention, there was significant variation. The shortest was a single - session acute training program (n = 16). The remaining studies adopted longitudinal training interventions lasting from several days to weeks. The most common implementation frequency for these interventions was 2–3 times per week, with each session lasting 20–40 min. The duration of the intervention cycle mainly ranged from 4–10 weeks, and the longest training intervention lasted for months, basically covering the entire season of a certain sport.

Regarding the stroboscopic frequency, it mainly ranged from 1–6 Hz, with a duty cycle (the percentage of the on - time in a cycle) ranging from 50% to 70%. For subjects with high - precision requirements and high - level athletes (such as in badminton), the training cycle was longer; and the stroboscopic frequency range could be extended to 8–15 Hz. Most studies conducted tests immediately after the training ended. Thirteen studies also conducted follow-up evaluations at various time points: 10 min (1 study), 1 day (2 studies), 2 days (1 study), 3 days (1 study), 1 week (2 studies), 10 days (1 study), 2 weeks (2 studies), 4 weeks (2 studies), and 6 weeks (1 study) after the intervention.

In summary, the reviewed studies displayed substantial diversity in sample sizes, participant profiles, intervention durations, and stroboscopic parameters. This high degree of variability across protocols highlights a significant challenge in comparing results across studies and underscores the need for standardization in future SVT research.

3.2.3 Summary of measurement results

The most common evaluation outcomes in these studies predominantly focused on behavioral performance related to specific sports stimuli and tasks. Specifically, nine studies employed sport - specific measurement methods, including completing sport - specific action tasks (such as penalty kicks, batting, and softball fielding) or perception - decision tasks based on computer - programmed scenarios (like predicting shooting actions from video clips). Additionally, three studies utilized non - sport - specific general stimulus tasks, with most involving computer - programmed cognitive tasks (such as multiple - object tracking). It is worth noting that some studies (n = 23) incorporated both sport - specific tasks and general stimuli as multi - dimensional outcome measurement indicators in their experimental designs. Moreover, five of the included studies utilized questionnaires to gather subjective evaluation data.

The results of this review support the notion that SVT can enhance skill levels and motor performance by improving human cognitive function (Figure 4). Specifically, 15 studies confirmed the association between the intervention effects of SVT and specific visual cognitive functions (such as visual information processing speed, visual attention, visual memory, and predictive decision - making ability). Twenty studies indicated the correlation between SVT outcomes and sport - specific or overall motor performance indicators (including hand - eye coordination, motor reaction ability, motor control ability, dynamic visual acuity, and multiple - object tracking ability), etc.

3.3 Effects of stroboscopic visual training on cognitive function

The reviewed studies demonstrated that SVT has a significant impact on various domains of cognitive function. A summary of the research protocols and main findings is provided in Table 1.

3.3.1 Information processing speed

Among the three studies focusing on information processing speed, consistent improvements were observed. Football athletes showed enhanced ball control and goalkeepers exhibited faster information-processing speed after SVT (Elhachemi and Issam, 2024). Adolescent volleyball players in the stroboscopic group significantly improved in simple movement time, complex reaction speed, and reactive agility, with benefits largely maintained at a 4-week follow-up (Zwierko M. et al., 2023). A key finding was that the reduction in visual-motor reaction time observed in badminton athletes was primarily driven by a decrease in pre-movement time, rather than the movement execution time itself (Hülsdünker et al., 2021a).

3.3.2 Visual attention

Analysis of four studies on visual attention revealed that SVT can significantly enhance players’ visual perception, attention allocation, and anticipation timing in sport-specific contexts (Ballester et al., 2017), such as ice hockey (Mitroff et al., 2013). However, its effects on peripheral vision and sustained attention were found to be limited (Appelbaum et al., 2011). Under stroboscopic conditions, a decline in passing accuracy was more pronounced among high-skilled athletes compared to their lower-skilled counterparts (Beavan et al., 2021). Conversely, other evidence indicated that skilled athletes can maintain performance by dynamically shifting their attention focus between external environmental and internal technical cues when visual feedback is restricted (Müller S, et al. (2024)).

3.3.3 Visual memory

Emerging research supports the concept of visual memory plasticity, demonstrating that the capacity of visual memory can be modified through targeted training interventions. One study specifically assessed visual memory and found that the stroboscopic group demonstrated superior short-term memory retention under longer stimulus-cue intervals. Notably, this improvement persisted for at least 24 h, suggesting a degree of endurance in the training effects (Appelbaum et al., 2012).

3.3.4 Predictive and decision - making abilities

A growing body of research has investigated the role of SVT in enhancing athletes’ predictive and decision-making abilities. Stroboscopic training was found to influence dribbling performance by reducing the number of ball touches, though this effect on dribbling precision was transient and rebounded after 1 week (Palmer et al., 2022). Participants exhibited reduced cognitive load during predictive tasks following SVT (Fortes et al., 2025). Significant improvements were also reported in perception-cognition test performance, sport-specific decision-making ability, and decision consistency (Top, 2022). In tennis, athletes who underwent low-frequency SVT (1 Hz) exhibited significantly higher accuracy in predicting serve directions (Boiangin, 2019). A single-session intervention on elite curling athletes adversely affected time perception and judgment, but a subsequent 4-week SVT intervention significantly enhanced the athletes’ time judgment and throwing speed control, though not throwing accuracy (Li et al., 2024a; 2024b).

3.4 Effects of stroboscopic visual training on motor performance

Evidence synthesized in this review confirms the beneficial role of SVT across various facets of motor performance, as detailed in Table 2.

3.4.1 Effects of SVT on hand - eye coordination

Hand–eye coordination refers to the ability to direct hand movements based on visual input. In sports, it is primarily associated with ball-catching skills. SVT has been shown to improve performance in both ball-catching and ball-hitting, offering promising potential for skill transfer in training. Long-term stroboscopic visual control training significantly improved the shooting accuracy of elite female basketball athletes (Oudejans, 2012). Collegiate baseball batters in the experimental group exhibited significant improvements in launch angle and hitting distance compared to the placebo group, although these practice-based improvements did not extend to actual in-game performance (Liu et al., 2020). A single-session SVT intervention significantly improved participants’ hand-eye coordination, with enhancement evident immediately after training, as well as at 10-min and 10-day follow-up assessments (Ellison et al., 2020). Long-term stroboscopic training also improved the ability of softball players to field ground balls, with novice players exhibiting greater gains compared to expert athletes (Edgerton, 2018). Tests on tennis players showed that as the stroboscopic frequency decreased and the dark-phase ratio increased, target-hitting accuracy scores declined significantly (Jendrusch et al., 2023).

3.4.2 Motor reaction ability

Motor reaction is a key indicator of motor performance. Wilkins et al. (2018) demonstrated that participants in the stroboscopic group exhibited consistent improvements in visual reaction time in both the post-test and the 4-week retention test, whereas no such improvements were observed in the control group. And long-term stroboscopic intervention significantly improved reaction agility and speed in young volleyball players (Zwierko M. et al., 2024). A single session of SVT increased reaction time across participants with different dribbling abilities, with the most substantial performance decline observed in high-ability players (Fransen et al., 2017). Conversely, a short-term stroboscopic intervention during the pre-game warm-up of elite athletes did not produce any immediate negative effects on visual-motor reaction performance (Strainchamps et al., 2023). The short-term application of stroboscopic glasses during soccer warm-up significantly improved performance in reactive agility tasks involving the ball, and this enhancement was maintained regardless of fatigue status (Zwierko T. et al., 2024).

3.4.3 Postural control ability

SVT promotes rapid neural adjustments and responsiveness, thereby positively contributing to balance training (McCreary et al., 2024). Research indicated that postural stability under stroboscopic visual conditions is comparable to that observed with eyes closed (Kim et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2020). When the somatosensory system was disrupted, stroboscopic glasses significantly altered visual reliance during postural control (Lee et al., 2022). A single stroboscopic session under low-frequency visual conditions significantly influenced postural stability (Jang, 2019). Thirty minutes of balance training with stroboscopic glasses not only enhanced dynamic balance performance but also improved the retention of balance skills, with most gains maintained after 2 weeks (Symeonidou and Ferris, 2022). For older adults, SVT transformed postural sway towards a more closed-loop process and facilitated sensory reweighting, reducing visual dependency (Chen et al., 2025; Tsai et al., 2022).

3.4.4 Dynamic visual acuity and multiple - Object tracking ability

The visual system maintains tracking of a moving object despite trajectory changes or obstructions by analyzing its spatiotemporal characteristics. SVT was found to immediately enhance dynamic visual acuity and improve ball-catching performance during training, although no long-term improvements were observed in follow-up tests conducted 2 weeks later (Holliday, 2013). In multiple-object tracking tasks, performance in the stroboscopic group remained stable regardless of frequency changes, whereas performance in the control group declined as frequency decreased. In multiple-object avoidance tasks, participants in the stroboscopic group demonstrated superior learning effects (Bennett et al., 2018).

4 Discussion

The primary objective of this review was to synthesize the effects of SVT on cognitive function and motor performance. The findings from 35 experimental studies collectively indicate that SVT is an effective intervention for enhancing a range of perceptual-cognitive and motor skills. The core mechanism underlying these improvements appears to be the neural adaptation induced by intermittent visual occlusion, which optimizes the efficiency of the visual and visuomotor systems.

4.1 Integration of key findings and theoretical implications

The consensus across the reviewed literature robustly supports the efficacy of SVT in enhancing fundamental cognitive processes. The pivotal finding that SVT reduces pre-movement time rather than movement execution time (Hülsdünker et al., 2021a) provides a critical mechanistic insight. This strongly suggests that SVT acts predominantly on the central nervous system to accelerate decision-making and motor planning, rather than merely improving the speed of muscular contraction. This central effect provides a parsimonious explanation for its broad transfer to various sports skills, as optimized central processing benefits multiple downstream actions.

Our results align with and extend the “Sports Vision Pyramid” model (Kirschen and Laby, 2011). SVT appears to target the foundational and middle layers of this pyramid—enhancing neural integration and processing of visual information—which in turn supports the attainment of optimal motor performance at the apex. The training challenges the brain to function more efficiently with less reliable visual input, thereby strengthening the neuro-visual foundations upon which sporting excellence is built.

However, the transfer of trained skills to authentic, competitive environments remains a critical consideration for practitioners. As evidenced by studies on baseball batting (Liu et al., 2020) and soccer dribbling (Palmer et al., 2022), improvements in controlled practice settings do not automatically translate to enhanced in-game performance. This underscores the notion that SVT should be viewed as a method to enhance foundational perceptual-cognitive capacities, which must then be strategically integrated into sport-specific, ecologically valid contexts to foster effective skill transfer.

4.2 Neuroplastic mechanisms and neural efficiency

The beneficial effects of SVT are not merely behavioral but are rooted in neuroplastic adaptations. The proposed mechanisms involve neural adaptations within the visuomotor system, including accelerated processing in motion-sensitive regions of the visual cortex (e.g., MT area) and enhanced neural efficiency (Hülsdünker et al., 2019; Wohl et al., 2024). Electrophysiological evidence, such as the reduction in P100 implicit time (Zwierko T. et al., 2023) and changes in N2 component latencies (Hülsdünker et al., 2021b; 2023), confirms that SVT accelerates early-stage visual processing and is associated with improvements in reaction speed.

The intermittent nature of visual input compels the brain to rely more heavily on visual-spatial memory and predictive extrapolation (Smith and Mitroff, 2012; Köster et al., 2023), thereby strengthening these higher-order cognitive pathways. Furthermore, findings of reduced blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal in key brain areas (e.g., left supramarginal gyrus, left inferior parietal lobule, left secondary somatosensory cortex, right superior frontal gyrus, and right supplementary motor area) after training (Wohl et al., 2024) provide support for the concept of neural efficiency—whereby the brain achieves superior performance with less effort or resource allocation after effective training.

4.3 Considerations for different populations and contexts

The effects of SVT are not uniform and are modulated by factors such as athletic proficiency and task demands. The observation that high-skilled athletes experience a more pronounced decline in passing accuracy under stroboscopic conditions (Beavan et al., 2021) suggests a greater dependency on continuous visual feedback to maintain precision at the elite level. However, their ability to maintain shooting accuracy by dynamically shifting attentional focus (Muller et al., 2024) also highlights their superior adaptive capacity.

The application of SVT extends beyond athletic enhancement into rehabilitation (Kroll et al., 2023). Promising evidence shows its utility in improving postural control in older adults by promoting sensory reweighting and reducing visual dependency (Chen et al., 2025; Tsai et al., 2022), and in aiding recovery for individuals with chronic ankle instability or ACL injuries (Avedesian, 2024; Mohess et al., 2024; Wohl et al., 2021). This underscores its potential as a versatile tool for both performance and therapy.

4.4 Limitations of the current body of evidence

Despite the promising evidence, this review highlights several significant limitations in the current literature. The most notable challenge is the lack of standardized training protocols. Substantial variability exists in stroboscopic frequencies, duty cycles, session durations, and intervention lengths across studies. This heterogeneity compromises the ability to compare results directly, establish dose-response relationships, and formulate evidence-based guidelines for practitioners.

Furthermore, the heavy reliance on behavioral outcomes provides limited insight into the underlying neural mechanisms. While a few studies have begun to incorporate neurophysiological measures, the field would greatly benefit from more extensive and multimodal investigations. Many studies are also confined to single-mode stroboscopic interventions, with insufficient exploration of how variables such as athletic level, stroboscopic frequency combinations, and integrated training approaches influence outcomes.

4.5 Implications for training practice

The findings of this systematic review provide clear guidance for the effective and safe application of SVT in athletic contexts. Based on the available evidence, we recommend that practitioners implement a long-term training regimen (≥4 weeks) utilizing a descending stroboscopic frequency paradigm, with a frequency of 2–3 sessions per week and 15 min of effective training time per session. The duty cycle should be appropriately set within the range of 50%–70%.

Training parameters should be individualized according to the specific demands of the sport and the athlete’s proficiency level. For elite athletes or precision-oriented sports (e.g., badminton), the use of relatively higher stroboscopic frequencies (e.g., 8–15 Hz) is recommended. In contrast, for dynamic, open-skill team sports (e.g., soccer) or athletes of moderate proficiency, lower frequencies (e.g., 1–6 Hz) are more suitable, particularly during the initial phases of training.

It is crucial to carefully manage the duty cycle and diligently monitor athletes’ fatigue levels throughout the implementation process. This practice is essential for maximizing training benefits and mitigating potential risks, such as dizziness or mental fatigue.

4.6 Future research directions

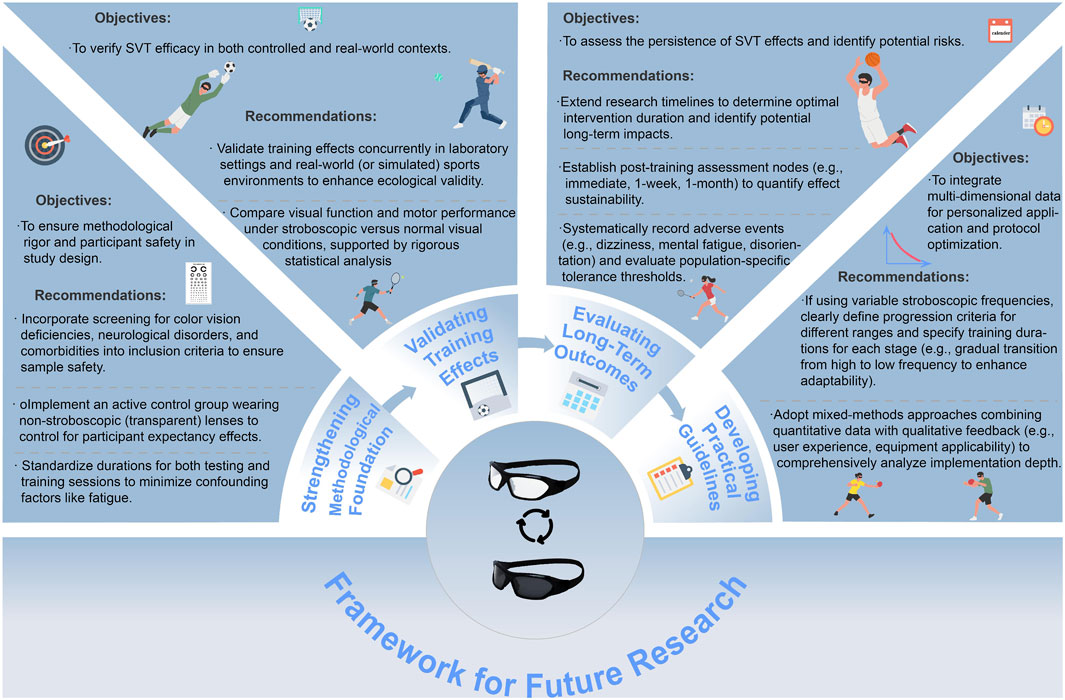

To address these limitations and unlock the full potential of SVT, we propose a comprehensive framework and set of recommendations aimed at enhancing the methodological rigor, ecological validity, and practical applicability of future SVT research, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Proposed framework and recommendations for future research on Stroboscopic Visual Training (SVT). The figure summarizes a comprehensive set of methodological suggestions aimed at enhancing the rigor, ecological validity, safety, and practical application of SVT studies. Key recommendations include improving inclusion criteria, validating effects in real-world settings, implementing rigorous control procedures, standardizing protocols, and expanding research on long-term sustainability and potential adverse effects.

Future studies may integrate portable devices to collect and transmit real-time physiological data—such as heart rate variability, reaction time, and muscle activation—during SVT interventions. By combining these data with individual training outcomes and leveraging big data analytics, researchers can establish a digital and intelligent dose–response model of SVT’s effects on cognitive function and motor performance. Additionally, advanced neuroimaging techniques, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), electroencephalography (EEG), and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), should be employed to investigate, from a multimodal perspective, how SVT influences brain structure and function, and how these neural changes translate into behavioral improvements.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, this systematic review establishes SVT not merely as a visual tool, but as a potent neurocognitive intervention. Its unique value lies in its “top-down” mechanism of action: by challenging the brain with intermittent visual input, SVT directly enhances foundational cognitive processes like information processing speed and attention allocation. These cognitive gains are not the ultimate goal but the critical mediator that drives the improvement of motor performance—from reactive agility to precise hand-eye coordination.

Therefore, the key practical implication of this study is the establishment of a new approach: “training the brain to optimize the body.” In practical application, it is essential to abandon a “one-size-fits-all” method and instead adopt scientifically-designed, individualized training protocols. The future of SVT lies in standardizing these protocols and further elucidating their underlying neural mechanisms, thereby developing it into an indispensable, scientifically-grounded method for enhancing sports performance.

Author contributions

YR: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Data curation. JZ: Investigation, Validation, Writing – review and editing, Formal Analysis. XS: Writing – review and editing, Investigation, Visualization, Resources. FQ: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review and editing. FG: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Funding acquisition, Project administration.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Key Project of Basic Scientific Research of the Liaoning Provincial Department of Education (Grant No. JYTZD2023133), the 2025 Basic Scientific Research Project of Colleges and Universities of Liaoning Provincial Department of Education (No. LJ212510176002), the Project of Basic Scientific Research of the Liaoning Provincial Department of Education (No. LJ212410176029), and the Graduate Student Innovation Practice Funding Program of Shenyang Sport University Graduate School.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Appelbaum L. G., Erickson G. (2018). Sports vision training: a review of the state-of-the-art in digital training techniques. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 11 (1), 160–189. doi:10.1080/1750984X.2016.1266376

Appelbaum L. G., Schroeder J. E., Cain M. S., Mitroff S. R. (2011). Improved visual cognition through stroboscopic training. Front. Psychol. 2, 276–288. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00276

Appelbaum L. G., Cain M. S., Schroeder J. E., Darling E. F., Mitroff S. R. (2012). Stroboscopic visual training improves information encoding in short-term memory. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 74 (8), 1681–1691. doi:10.3758/s13414-012-0344-6

Avedesian J. M. (2024). Think fast, stay healthy? A narrative review of neurocognitive performance and lower extremity injury. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 74, 103186. doi:10.1016/j.msksp.2024.103186

Ballester R., Huertas F., Uji M., Bennett S. J. (2017). Stroboscopic vision and sustained attention during coincidence-anticipation. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 17898. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-18092-5

Bao M., Huang C. B., Wang L., Zhang T., Jiang Y. (2017). Visual information processing and its brain mechanism. Sci. Technol. Rev. 35, 15–20. doi:10.3981/j.issn.1000-7857.2017.19.001

Beavan A., Hanke L., Spielmann J., Skorski S., Mayer J., Meyer T., et al. (2021). The effect of stroboscopic vision on performance in a football specific assessment. Sci. Med. Footb. 5 (4), 317–322. doi:10.1080/24733938.2020.1862420

Bennett S. J., Hayes S. J., Uji M. (2018). Stroboscopic vision when interacting with multiple moving objects: perturbation is not the same as elimination. Front. Psychol. 9, 1290. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01290

Boiangin N. M. (2019). Stroboscopic training effect on anticipating the direction of tennis serves [master's thesis]. Tallahassee, FL: Florida State University.

Braly A. M., DeLucia P. R. (2020). Can stroboscopic training improve judgments of time-to-collision? Hum. Factors 62 (1), 152–165. doi:10.1177/0018720819841938

Buscemi A., Mondelli F., Biagini I., Gueli S., D’Agostino A., Coco M. (2024). Role of sport vision in performance: systematic review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 9 (2), 92. doi:10.3390/jfmk9020092

Carrolla W., Fullerb S., Lawrenceb J. M., Osborne S., Stallcup R., Burch R., et al. (2021). Stroboscopic visual training for coaching practitioners: a comprehensive literature review. Int. J. Kinesiol. Sport. Sci. 9 (4), 49–59. doi:10.7575/aiac.ijkss.v.9n.4p.49

Chen Y. C., Tsai Y. Y., Lin Y. T., Hwang I. S. (2025). Enhancing anticipation control of the posture system in the elderly wearing stroboscopic glasses. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 22 (1), 104. doi:10.1186/s12984-025-01549-4

Das J., Walker R., Barry G., Vitório R., Stuart S., Morris R. (2023). Stroboscopic visual training: the potential for clinical application in neurological populations. PLOS Digit. Health 2 (8), e0000335. doi:10.1371/journal.pdig.0000335

Edgerton L. (2018). The effect of stroboscopic training on the ability to catch and field. Tempe, AZ: Arizona State University.

Elhachemi E. H., Issam H. (2024). Effect of a stroboscopy visual training with senaptec glasses on reaction speed and ball control technique among goalkeepers for the U13 years old. Int. J. Health Sci. 8 (S1), 531–540. doi:10.53730/ijhs.v8nS1.14850

Elliott D., Bennett S. J. (2021). Intermittent vision and goal-directed movement: a review. J. Mot. Behav. 53 (4), 523–543. doi:10.1080/00222895.2020.1793716

Erickson G. B. (2020). Sports Vision: vision care for the enhancement of sports performance. 2nd Edn. St. Louis: Elsevier.

Ellison P., Jones C., Sparks S. A., Murphy P. N., Page R. M., Carnegie E., et al. (2020). The effect of stroboscopic visual training on eye–hand coordination. Sport Sci. Health 16 (3), 401–410. doi:10.1007/s11332-019-00615-4

Erickson G. B. (2022). Sports vision: vision care for the enhancement of sports performance. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Erickson G. B. (2021). Topical review: visual performance assessments for sport. Optom. Vis. Sci. 98 (7), 672–680. doi:10.1097/opx.0000000000001731

Fortes L. S., Faro H., Faubert J., Freitas-Júnior C. G., Lima-Junior D. D., Almeida S. S. (2025). Repeated stroboscopic vision training improves anticipation skill without changing perceptual-cognitive skills in soccer players. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 32 (4), 1123–1137. doi:10.1080/23279095.2023.2243358

Fransen J., Lovell T. W., Bennett K. J., Deprez D., Deconinck F. J., Lenoir M., et al. (2017). The influence of restricted visual feedback on dribbling performance in youth soccer players. Mot. Control 21 (2), 158–167. doi:10.1123/mc.2015-0059

Gokeler A., Seil R., Kerkhoffs G., Verhagen E. (2018). A novel approach to enhance ACL injury prevention programs. J. Exp. Orthop. 5 (1), 22. doi:10.1186/s40634-018-0137-5

Hadlow S. M., Panchuk D., Mann D. L., Portus M. R., Abernethy B. (2018). Modified perceptual training in sport: a new classification framework. J. Sci. Med. Sport 21 (9), 950–958. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2018.01.011

Higuchi T., Nagami T., Nakata H., Kanosue K. (2018). Head-eye movement of collegiate baseball batters during fastball hitting. PLoS ONE 13 (7), e0200443. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200443

Holliday J. (2013) “Effect of stroboscopic vision training on dynamic visual acuity scores: Nike vapor strobe® eyewear,”. Logan, UT: Utah State University. doi:10.26076/201c-8992

Hülsdünker T., Strüder H. K., Mierau A. (2018). The athletes’ visuomotor system–cortical processes contributing to faster visuomotor reactions. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 18 (7), 955–964. doi:10.1080/17461391.2018.1468484

Hülsdünker T., Rentz C., Ruhnow D., Käsbauer H., Strüder H. K., Mierau A. (2019). The effect of 4-week stroboscopic training on visual function and sport-specific visuomotor performance in top-level badminton players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 14 (3), 343–350. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2018-0302

Hülsdünker T., Gunasekara N., Mierau A. (2021a). Short-and long-term stroboscopic training effects on visuomotor performance in elite youth sports. Part 1: reaction and behavior. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 53 (5), 960–972. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000002541

Hülsdünker T., Gunasekara N., Mierau A. (2021b). Short-and long-term stroboscopic training effects on visuomotor performance in elite youth sports. Part 2: Brain–Behavior mechanisms. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 53 (5), 973–985. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000002543

Hülsdünker T., Fontaine G., Mierau A. (2023). Stroboscopic vision prolongs visual motion perception in the central nervous system. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 33 (1), 47–54. doi:10.1111/sms.14239

Jafarzadehpur E., Aazami N., Bolouri B. (2007). Comparison of saccadic eye movements and facility of ocular accommodation in female volleyball players and non-players. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 17 (2), 186–190. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00535.x

Jang J. (2019). Visual reweighting using stroboscopic vision in healthy individuals. Omaha, NE: University of Nebraska at Omaha. (Omaha, NE).

Jendrusch G., Binz N., Platen P. (2023). Einsatz von Shutter-Brillen im Tennis – einfluss von (Bild-)Frequenz und Dunkelphasenanteil auf die Zielschlagpräzision. Optom. Contact Lens 3, 359–367. doi:10.54352/dozv.ROFV4461

Jothi S., Dhakshinamoorthy J., Kothandaraman K. (2025). Effect of stroboscopic visual training in athletes: a systematic review. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 20 (2), 562–573. doi:10.55860/vm1j3k88

Kim K. M., Kim J. S., Grooms D. R. (2017). Stroboscopic vision to induce sensory reweighting during postural control. J. Sport Rehabil. 26 (5), 428–436. doi:10.1123/jsr.2017-0035

Kim K. M., Kim J. S., Oh J., Grooms D. R. (2020). Stroboscopic vision as a dynamic sensory reweighting alternative to the sensory organization test. J. Sport Rehabil. 30 (1), 166–172. doi:10.1123/jsr.2019-0466

Kirschen D. G., Laby D. L. (2011). The role of sports vision in eye care today. Eye Contact Lens 37 (3), 127–130. doi:10.1097/ICL.0b013e3182126a08

Klemish D., Ramger B., Vittetoe K., Reiter J. P., Tokdar S. T., Appelbaum L. G. (2018). Visual abilities distinguish pitchers from hitters in professional baseball. J. Sports Sci. 36 (2), 171–179. doi:10.1080/02640414.2017.1288296

Koppelaar H., Moghadam P. K., Khan K., Kouhkani S., Segers G., van Warmerdam M. (2019). Reaction time improvements by neural bistability. Behav. Sci. 9 (3), 28. doi:10.3390/bs9030028

Köster M., Brzozowska A., Bánki A., Tünte M., Ward E. K., Hoehl S. (2023). Rhythmic visual stimulation as a window into early brain development: a systematic review. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 64, 101315. doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2023.101315

Krigolson O. E., Cheng D., Binsted G. (2015). The role of visual processing in motor learning and control: insights from electroencephalography. Vis. Res. 110, 277–285. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2014.12.024

Kroll M., Preuss J., Ness B. M., Dolny M., Louder T. (2023). Effect of stroboscopic vision on depth jump performance in female NCAA division I volleyball athletes. Sports Biomech. 22 (8), 1016–1026. doi:10.1080/14763141.2020.1773917

Laby D. M., Appelbaum L. G. (2021). Review: vision and On-field performance: a critical review of visual assessment and training studies with athletes. Optom. Vis. Sci. 98 (7), 723–731. doi:10.1097/OPX.0000000000001729

Lee H., Han S., Hopkins J. T. (2022). Altered visual reliance induced by stroboscopic glasses during postural control. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (4), 2076. doi:10.3390/ijerph19042076

Li T., Wang X., Wu Z., Liang Y. (2024a). The effect of stroboscopic vision training on the performance of elite curling athletes. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 31730. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-82685-0

Li T., Zhang C., Wang X., Zhang X., Wu Z., Liang Y. (2024b). The impact of stroboscopic visual conditions on the performance of elite curling athletes. Life 14 (9), 1184. doi:10.3390/life14091184

Liu S., Ferris L. M., Hilbig S., Asamoa E., Port N., Appelbaum L. G. (2020). Dynamic vision training transfers positively to batting performance among collegiate baseball batters. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 52 (7S), 1051. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101759

Lochhead L., Feng J., Laby D. M., Appelbaum L. G. (2024a). Visual performance and sports: a scoping review. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 46 (4), 205–217. doi:10.1123/jsep.2023-0267

Lochhead L., Feng J., Laby D. M., Appelbaum L. G. (2024b). Training vision in athletes to improve sports performance: a systematic review of the literature. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol., 1–23. doi:10.1080/1750984X.2024.2437385

Luo Y., Cao Y., Pan X., Li S., Koh D., Shi Y. (2025). Effects of stroboscopic visual training on reaction time and movement accuracy in collegiate athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 25151. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-10393-4

McCreary M. E., Lapish C. M., Lewis N. M., Swearinger R. D., Ferris D. P., Pliner E. M. (2024). Effects of stroboscopic goggles on standing balance in the spatiotemporal and frequency domains: an exploratory study. J. Appl. Biomech. 40 (6), 462–469. doi:10.1123/jab.2023-0285

Mitroff S. R., Friesen P., Bennett D., Yoo H., Reichow A. W. (2013). Enhancing ice hockey skills through stroboscopic visual training: a pilot study. Athl. Train. Sports Health Care 5 (6), 261–264. doi:10.3928/19425864-20131030-02

Mohess J. S., Lee H., Uzlaşir S., Wikstrom E. A. (2024). The effects of augmenting balance training with stroboscopic goggles on postural control in chronic ankle instability patients: a critically appraised topic. J. Sport Rehabil. 33 (6), 467–472. doi:10.1123/jsr.2023-0412

Müller S., Beseler B., Morris-Binelli K., Mesagno C. (2024). Temporal samples of visual information guides skilled interception. Front. Psychol. 15, 1328991. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1328991

Oudejans R. R. (2012). Effects of visual control training on the shooting performance of elite female basketball players. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 7 (3), 469–480. doi:10.1260/1747-9541.7.3.469

Oudejans R. R., Koedijker J. M., Bleijendaal I., Bakker F. C. (2005). The education of attention in aiming at a far target: training visual control in basketball jump shooting. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 3 (2), 197–221. doi:10.1080/1612197X.2005.9671767

Palmer T., Coutts A. J., Fransen J. (2022). An exploratory study on the effect of a four-week stroboscopic vision training program on soccer dribbling performance. Braz. J. Mot. Behav. 16 (3), 254–265. doi:10.20338/bjmb.v16i3.310

Piras A. (2024). The timing of vision in basketball three-point shots. Front. Psychol. 15, 1458363. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1458363

Smith T. Q., Mitroff S. R. (2012). Stroboscopic training enhances anticipatory timing. J. Exerc. Sci. 5 (4), 344–353. doi:10.70252/OTSW1297

Smith E. M., Sherman D. A., Duncan S., Murray A., Chaput M., Murray A. (2024). Test–retest reliability and visual perturbation performance costs during 2 reactive agility tasks. J. Sport Rehabil. 33, 444–451. doi:10.1123/jsr.2023-0433

Stănescu M. (2021). The effects of using stroboscopic training on sports performance. Discobolul Phys. Educ. Sport Kinetother. J. 60 (2), 118–127. doi:10.35189/dpeskj.2021.60.2.4

Strainchamps P., Ostermann M., Mierau A., Hülsdünker T. (2023). Stroboscopic eyewear applied during Warm-Up does not provide additional benefits to the sport-specific reaction speed in highly trained table tennis athletes. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 18 (10), 1126–1131. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2022-0426

Symeonidou E. R., Ferris D. P. (2022). Intermittent visual occlusions increase balance training effectiveness. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 16, 748930. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2022.748930

Top E. (2022). Üç boyutlu nesne takibi ve stroboskopik antrenmanın profesyonel sporculardaki karar verme ve bilişsel performansa etkisi [master's thesis]. Istanbul: Marmara University. (Turkey).

Tsai Y. Y., Chen Y. C., Zhao C. G., Hwang I. S. (2022). Adaptations of postural sway dynamics and cortical response to unstable stance with stroboscopic vision in older adults. Front. Physiol. 13, 919184. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.919184

Uzlaşır S., Özdıraz K. Y., Dağ O., Tunay V. B. (2021). The effects of stroboscopic balance training on cortical activities in athletes with chronic ankle instability. Phys. Ther. Sport 50, 50–58. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2021.03.014

Vasile A. I., Stănescu M. (2023). Application of strobe training as motor-cognitive strategy in sport climbing. J. Educ. Sci. Psychol. 13 (75), 131–138. doi:10.51865/JESP.2023.1.14

Vasile A. I., Stănescu M. I. (2024). Strobe training as a visual training method that improves performance in climbing. Front. Sports Act. Living 6, 1366448. doi:10.3389/fspor.2024.1366448

Wilkins L., Appelbaum L. G. (2020). An early review of stroboscopic visual training: insights, challenges and accomplishments to guide future studies. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 13 (1), 65–80. doi:10.1080/1750984X.2019.1582081

Wilkins L., Gray R. (2015). Effects of stroboscopic visual training on visual attention, motion perception, and catching performance. Percept. Mot. Ski. 121 (1), 57–79. doi:10.2466/22.25.pms.121c11x0

Wilkins L., Nelson C., Tweddle S. (2018). Stroboscopic visual training: a pilot study with three elite youth football goalkeepers. J. Cogn. Enhanc. 2, 3–11. doi:10.1007/s41465-017-0038-z

Wohl T. R., Criss C R., Grooms D. R. (2021). Visual perturbation to enhance return to sport rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament injury: a clinical commentary. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 16 (2), 552–564. doi:10.26603/001c.21251

Wohl T. R., Criss C. R., Haggerty A. L., Rush J. L., Simon J. E., Grooms D. R. (2024). The impact of visual perturbation neuromuscular training on landing mechanics and neural activity: a pilot study. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 19 (11), 1333–1347. doi:10.26603/001c.123958

Zhu R., Zou D., Wang K., Cao C. (2024). Expert performance in action anticipation: visual search behavior in volleyball spiking defense from different viewing perspectives. Behav. Sci. 14 (3), 163. doi:10.3390/bs14030163

Zwierko M., Jedziniak W., Popowczak M., Rokita A. (2023). Effects of in-situ stroboscopic training on visual, visuomotor and reactive agility in youth volleyball players. PeerJ 11, e15213. doi:10.7717/peerj.15213

Zwierko T., Jedziniak W., Domaradzki J., Zwierko M., Opolska M., Lubiński W. (2023). Electrophysiological evidence of stroboscopic training in elite handball players: visual evoked potentials study. J. Hum. Kinet. 90, 57–69. doi:10.5114/jhk/169443

Zwierko M., Jedziniak W., Popowczak M., Rokita A. (2024). Effects of six-week stroboscopic training program on visuomotor reaction speed in goal-directed movements in young volleyball players: a study focusing on agility performance. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 16 (1), 59. doi:10.1186/s13102-024-00848-y

Keywords: stroboscopic visual training, cognitive function, motor performance, neuroplasticity, sports training

Citation: Ren Y, Zhang J, Sun X, Qi F and Guo F (2025) The effects of stroboscopic visual training on human cognitive function and motor performance: a systematic review. Front. Physiol. 16:1708783. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2025.1708783

Received: 19 September 2025; Accepted: 11 November 2025;

Published: 27 November 2025.

Edited by:

Pedro Alexandre Duarte-Mendes, Polytechnic Institute of Castelo Branco, PortugalReviewed by:

Carlos Farinha, Polytechnic Institute of Castelo Branco, PortugalCarlos Humberto Andrade-Moraes, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Copyright © 2025 Ren, Zhang, Sun, Qi and Guo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Feng Guo, Z3VvZmVuZ19maXJzdEAxNjMuY29t

Yinghui Ren1

Yinghui Ren1 Fengxue Qi

Fengxue Qi Feng Guo

Feng Guo