- 1Department of Physiology, Weill Bugando School of Medicine, Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences, Mwanza, Tanzania

- 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Weill Bugando School of Medicine, Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences, Mwanza, Tanzania

- 3Department of Pharmacology, Weill Bugando School of Medicine, Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences, Mwanza, Tanzania

- 4Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Weill Bugando School of Medicine, Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences, Mwanza, Tanzania

- 5Department of Internal Medicine, Weill Bugando School of Medicine, Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences, Mwanza, Tanzania

Background: Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a frequent finding in men living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (MLWH) and this remains a major concern because of its negative impact on the quality of life of those affected. There is limited data about the magnitude of ED and associated factors among MLWH in Tanzania. Thus this study was aimed to determine the prevalence of ED and associated factors among newly diagnosed antiretroviral therapy (ART)-naive MLWH in Mwanza, Northwestern Tanzania.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted among 373 newly diagnosed ART-naïve MLWH attending voluntary counseling and testing centers of four selected hospitals in Mwanza region who were consecutively enrolled and subjected to thorough clinical and general physical examination, including anthropometric measurements. A pre-structured questionnaire was used to collect socio-demographic characteristics and clinical data. ED was assessed using the International Index of Erectile Function–5. Serum total testosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone and estradiol were estimated. Data were entered in Microsoft Excel, cleaned and analyzed using STATA version 15.

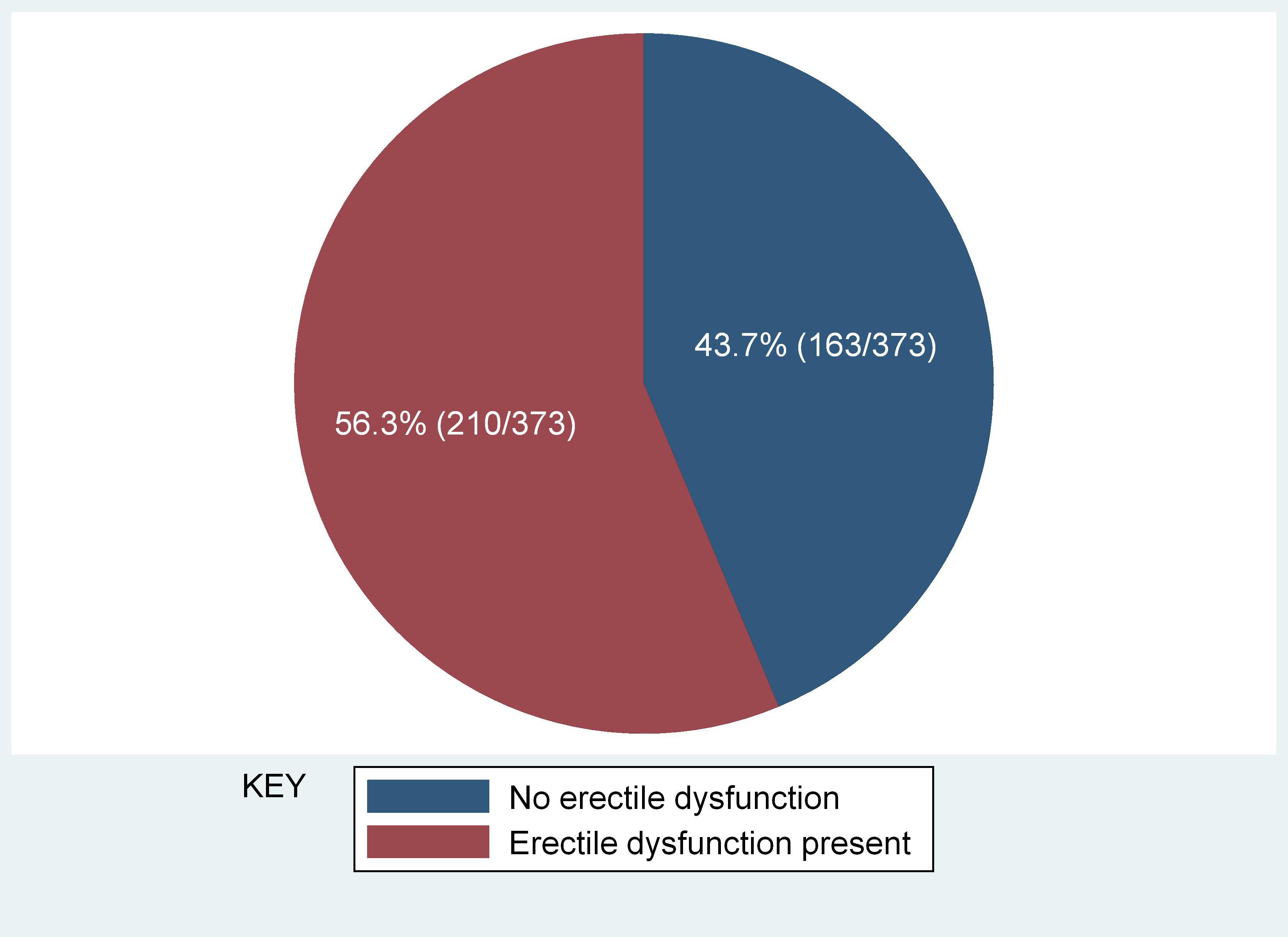

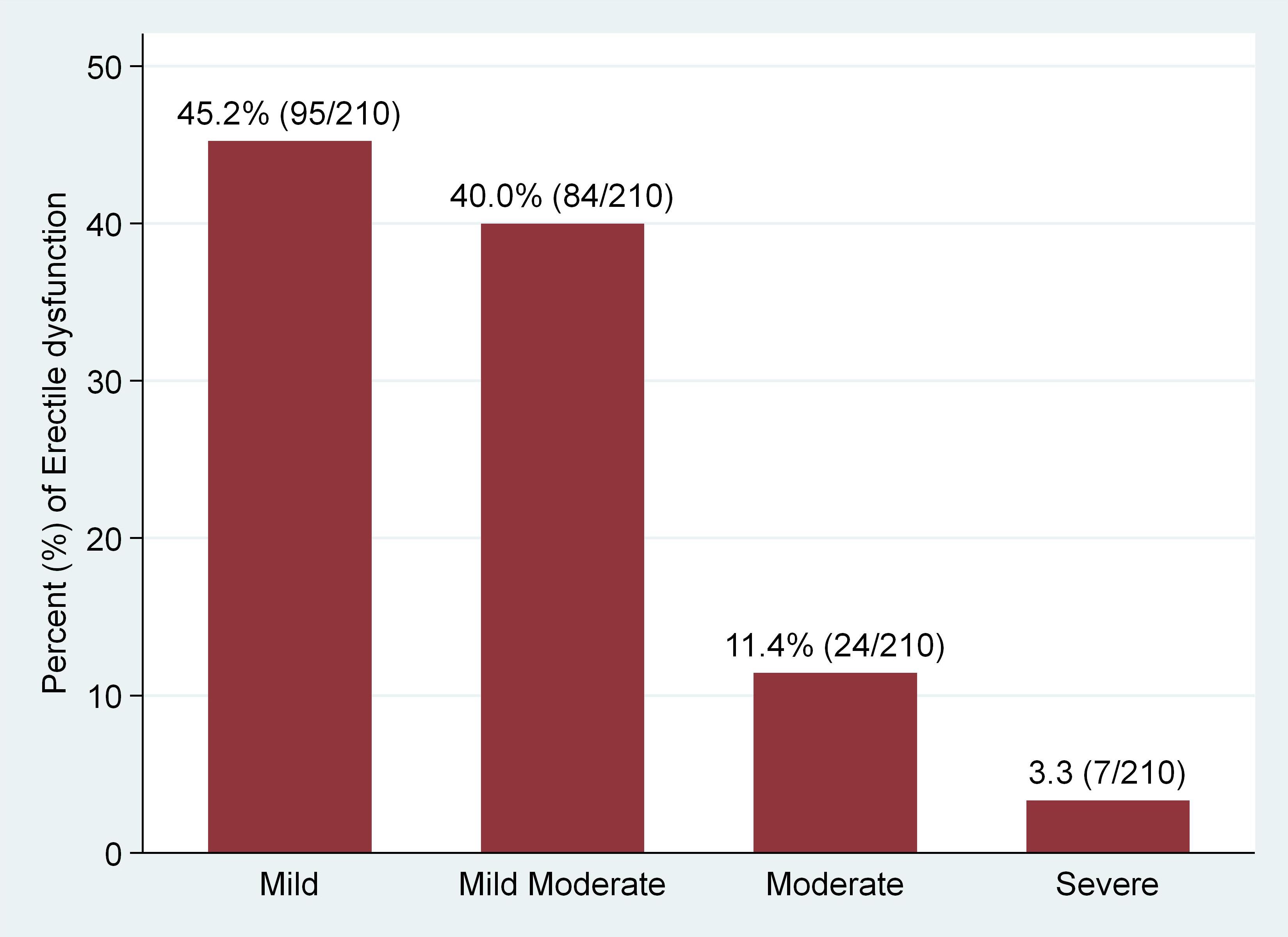

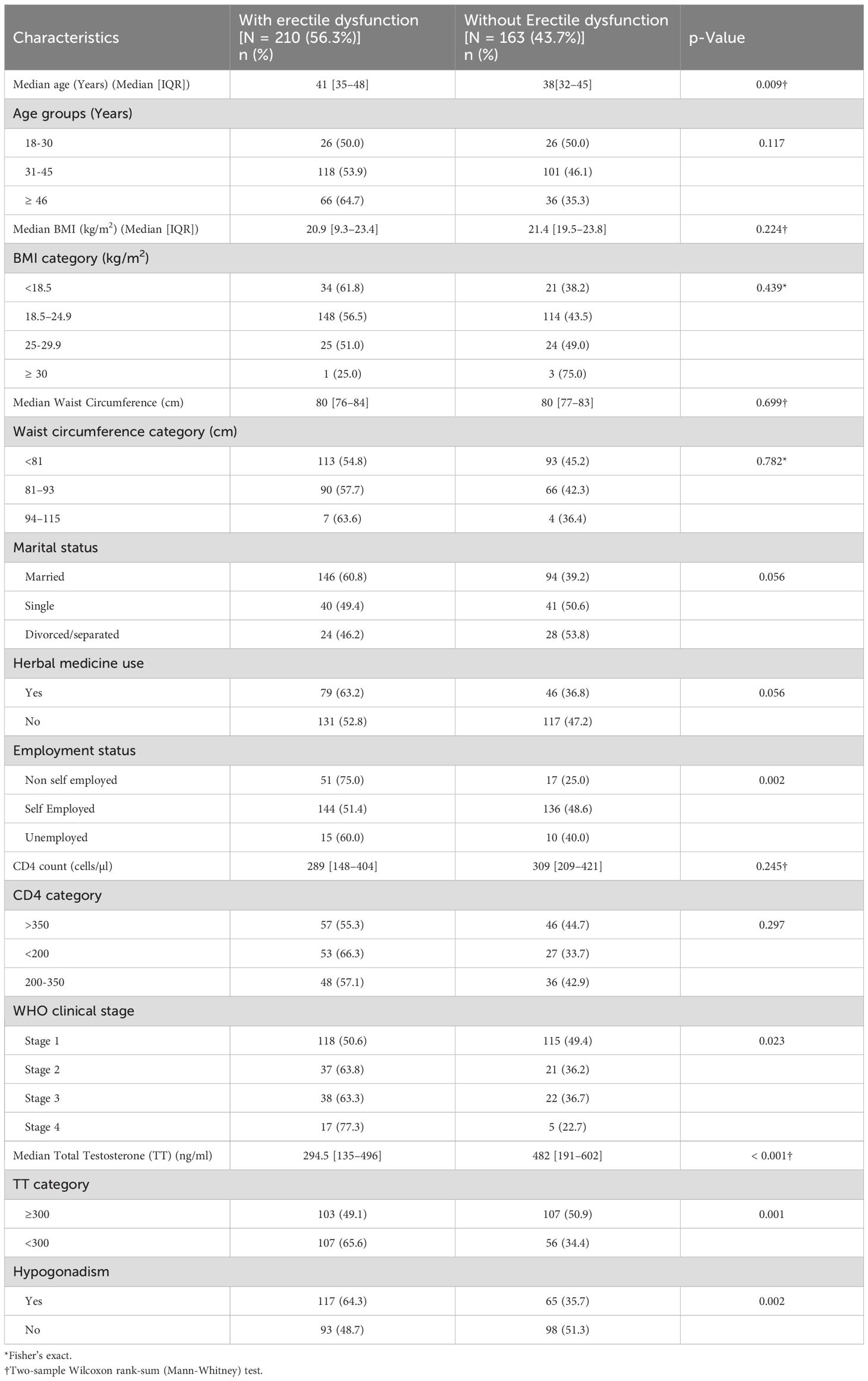

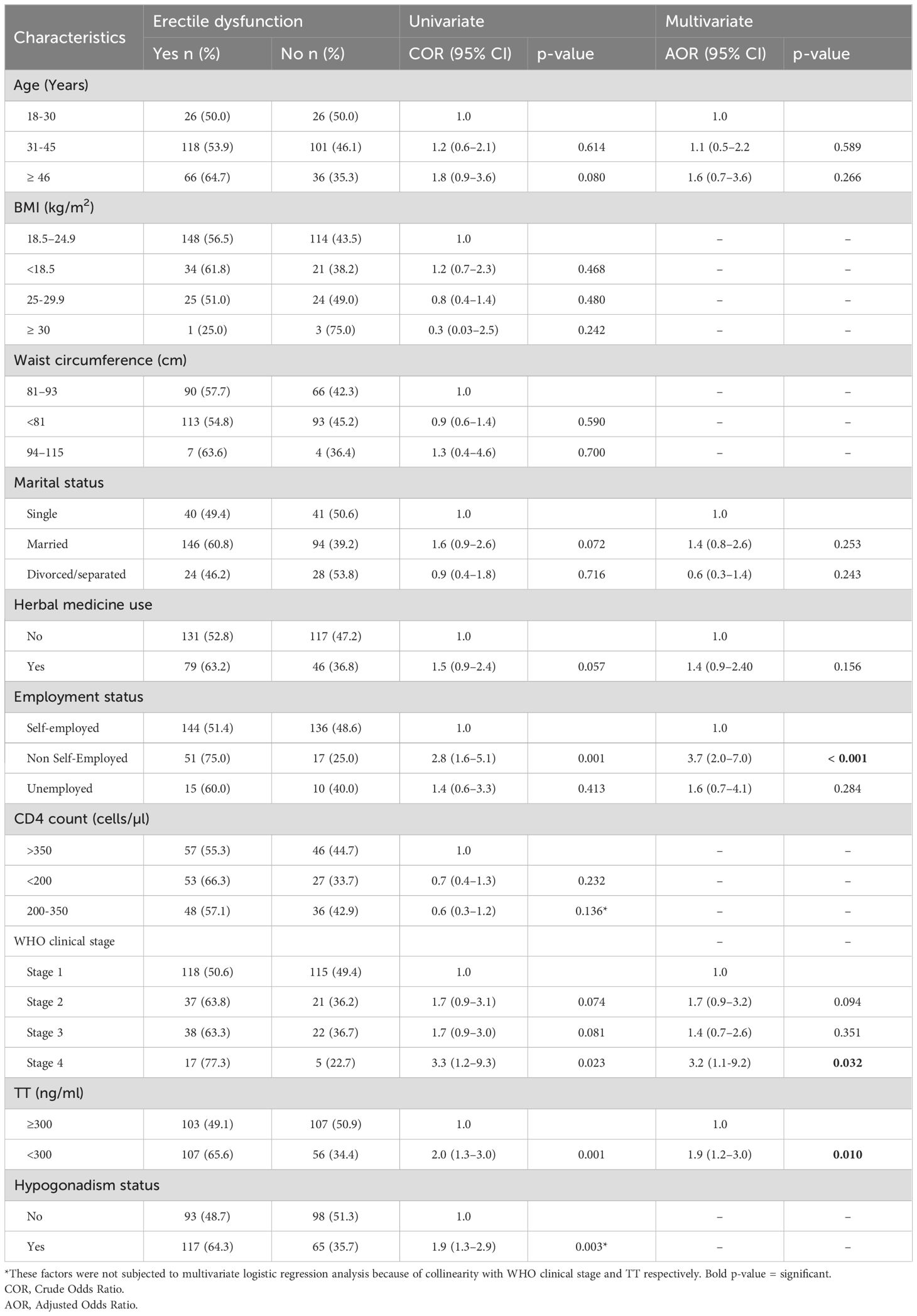

Results: Of the 373 analyzed participants with a median age of 40 [IQR: 33–46] years, ED was found in 56.3% (95% CI 51.2%–61.3%), whereas the majority presented with mild (45.2%) to mild-moderate (40.0%) ED. The median testosterone was significantly lower in men with ED as compared with men without (294.5 [135–469] versus 482 [191–602] ng/ml; p<0.001). In a multivariate logistic regression analysis, ED showed significant association with World Health Organization (WHO) clinical stage 4 for HIV infection (AOR 3.2; 95% CI 1.1–9.2; p=0.032), low testosterone level (AOR 1.9; 95% CI 1.2–3.0; p=0.010), and being non-self-employed (AOR 3.7; 95% CI 2.0–7.0; p<0.001).

Conclusion: ED was found in more than half of ART naïve MLWH. The majority had a mild to mild-moderate ED. There was a significant association between ED and WHO clinical stage 4 for HIV infection, low testosterone level, and being non-self-employed. This finding emphasizes the need to routinely screen for early detection and management of ED in care and treatment center (CTC) clinics.

Introduction

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is defined as the inability to achieve or maintain a satisfactory penile erection during sexual intercourse (1, 2). The main causes of ED are categorized as either psychogenic (depression, stress and anxiety) or organic (hormonal, neurological, vascular and tissue problems) (3). Hypogonadism is one of the cause of ED, so ED can be caused by any category of hypogonadism including that which occur due to aging (4, 5), non-infectious conditions (obesity, diabetes, hypertension, cancers, malnutrition among others) (4, 6–9), anemia (4, 7), common acute and chronic illnesses (10), weight loss (11), invasion of the glands by pathogens (Hepatitis virus, Cytomegalovirus, HIV among others) (2, 12), cigarette smoking, using drugs, such as opiates, megestrol acetate, methadone (4, 13, 14) and steroids (15), hyperprolactinemia as well as primary and secondary hypogonadism (12, 16, 17). Some of the herbal medicines are known to possess antifertility properties through various mechanisms including inhibiting 5-alpha reductase, a factor that converts testosterone into dihydrotestosterone, reducing gonadotropins and testosterone secretion, increasing the testosterone affinity for sex specific proteins among others (18). Since traditional herbal medicine and complementary alternative medicine are commonly used by treatment naïve HIV patients (19, 20), they can therefore be one of the cofactors for hypogonadism.

The prevalence of ED is higher in men living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (MLWH) than in the general population reaching to 74% in some studies (21). The pathogenesis of ED in these patient is not clear. Hypogonadism is one of the most frequent endocrine disorders in HIV infected men. Low levels of testosterone leads to reduced sexual desire and ED, however some studies have reported poor relationship of testosterone to these sexual function parameters (22, 23). Further, antiretroviral therapy (ART) had been implicated as the cause of sexual problems including erectile dysfunction (24–26) but with contradicting results in other studies (21, 27, 28). In addition, psychological (depression) or neurological (infection, dementia) problems often cause ED (3, 29–33).

Even though ED is more prevalent in MLWH than in the general population, little consideration has been given worldwide to the diagnosis and management of ED among MLWH, and Tanzania inclusive. There is paucity of evidence on the magnitude and factors associated with ED in MLWH in Tanzania. This study is aimed to determine the prevalence of ED and its associated factors among newly diagnosed MLWH, in Mwanza, Northwestern Tanzania.

Materials and methods

Study design, setting and period

A hospital-based, multi-center, cross-sectional study involving newly diagnosed HIV positive males was conducted at Voluntary Counseling and Testing (VCT) centers at Sekou-Toure Regional Referral Hospital (STRRH), Bugando Medical Centre (BMC), Nyamagana District Hospital (NDH) and Magu District Hospital (MDH), Mwanza, Tanzania from January 2020 and August 2022.

Study population and eligibility criteria

All newly diagnosed HIV positive (diagnosed as per WHO guidelines 2015) males aged 18 years and above who attended the VCTs during the study period were included in the study. Patients with previous history of gonadal dysfunction, taking drugs known to affect hormone levels (i.e. androgens, sex steroids, dehydroepiandrosterone, antiandrogens, anabolic agents, GnRH agonists and psycholeptic agents), having chronic liver disease, coinfection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) chronic kidney injury, tuberculosis and Diabetes mellitus (DM) that could serve as confounders were excluded from this study.

Sample size and sampling procedure

Sample size for this study was calculated using Kish-Leslie formula (1965) (34)

Where:

n = minimum sample size

Zσ = Z score level of significance (1.96)

P = Prevalence from previous study

ϵ = Precision of the study (set at 5% or 0.05)

Using the prevalence of ED of 37.8% from a study done in Nigeria (35) gave the minimum sample size of 361 participants. A total of 388 participants were enrolled in this study in order to take care of non-response. However, 373 participants were included in the final analysis. Fifteen (3.9%) participants were excluded as they had not completed the IIEF-5 questionnaire for erectile dysfunction. A convenient sampling technique was used to enroll study participants, where subjects were recruited as they were coming at each hospital until the sample size for the study was attained. At the completion of data collection the distribution of participants was: STRRH 105 (28.1%), BMC 110 (29.5%), NDH 132 (35.4%), and MDH 26 (7.0%).

Data collection and laboratory procedure

All participants were evaluated clinically by comprehensive history taking and a general physical examination including anthropometric measurements such as waist circumference (WC) and body mass index (BMI). Socio-demographic data including age, employment status, marital status and herbal medicine use status (whether they used any herbal medicine within the past six months or not) were collected using a pre-structured questionnaire. Height was measured in the upright standing position using a calibrated stadiometer. Body weight was measured with minimal clothing by using a standard calibrated weighing scale, and BMI was then calculated by the formula: weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. WC was measured at the approximate midpoint between the lower margin of the last palpable rib and the top of the iliac crest using flexible plastic tape and was calculated as an average of 3 measurements. Anthropometric parameters were measured by a single trained research assistant at each hospital.

ED was studied by using the validated Swahili translated 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) questionnaire (36–40). The items in the IIEF-5 questionnaire focus on erectile function and intercourse satisfaction (36, 41). All responses to the IIEF-5 questions were rated on a 5-point scale, with a score of 1 representing the worst and 5 the best response. ED was classified into five severity levels as follows: 1-7: Severe ED, 8-11: Moderate ED, 12-16: Mild-moderate ED, 17-21: Mild ED and 22-25: No ED.

Five milliliters (mls) of venous blood sample was collected from each of the study participants between 8.00 AM and 11.00 AM and serum was harvested. The serum was used for the estimation of total testosterone (TT) hormone, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH) and estradiol levels. The serum samples were stored at -20°C for not more than 30 days until analyzed.

The hormonal tests were done using chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) techniques. The CLIA kits were sourced from the Snibe Co., Ltd, Shnzhen, China. Serum hormones (TT, FSH, LH and estradiol) were estimated using the fully-automated chemiluminescence immunoassay analyzer model Maglumi 2000 (Snibe Diagnostic, China) following CLIA principles and the kit manufacturer’s instructions. The CD4+ count was assessed by flow cytometry (Roche diagnostics).

Hypogonadism was defined as a serum TT level of<300ng/dl or a serum TT level of ≥300 ng/dl with high FSH (>12 mlU/L) or LH (>12 mlU/L) level (42). Eugonadism was defined as normal TT and normal FSH and LH levels. Compensatory hypogonadism was defined as normal TT but high FSH or LH levels. Primary hypogonadism was defined as low TT levels with high FSH and LH, while secondary hypogonadism was defined as low TT with low or normal FSH or LH (42, 43).

Data analysis

Data were cleaned and checked for completeness and consistency and then corrected. The data were coded and entered into Microsoft Excel and then transported to STATA software, version 15 (Texas, USA) for analysis. For descriptive statistics results were expressed in tables, bar graphs and pie charts. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages while continuous variables were summarized using median with interquartile range (IQR). Graphical distribution plots and Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of data distribution. The associations between categorical variables and ED were determined using a Pearson’s Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. To assess the significance of difference when comparing various patient characteristics (Age, BMI, Waist circumference, CD4 cell count and TT) between participants with ED and those without ED we used Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Univariate followed by multivariate logistic regression models were used to determine risk factors for ED whereby factors with a p value less than 0.2 in the univariate were subjected to multivariate logistic regression analysis. In all analyses, the statistical significance was set at a p-value of less than 0.05.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the Joint Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences and Bugando Medical Center (CUHAS/BMC) research ethics and review committee with ethical clearance certificate number CREC/407/2019. Permission to carry out the study was also sought from the appropriate hospital authorities. The study participants provided written informed consent before participating in the study. No information was shared with any third party, and numbers were used in the questionnaires instead of personal identifiers. The copies of the hormone assay results report were shared to the clinicians, and all participants diagnosed with hypogonadism and ED were advised to report to the clinicians for advice and further management.

Results

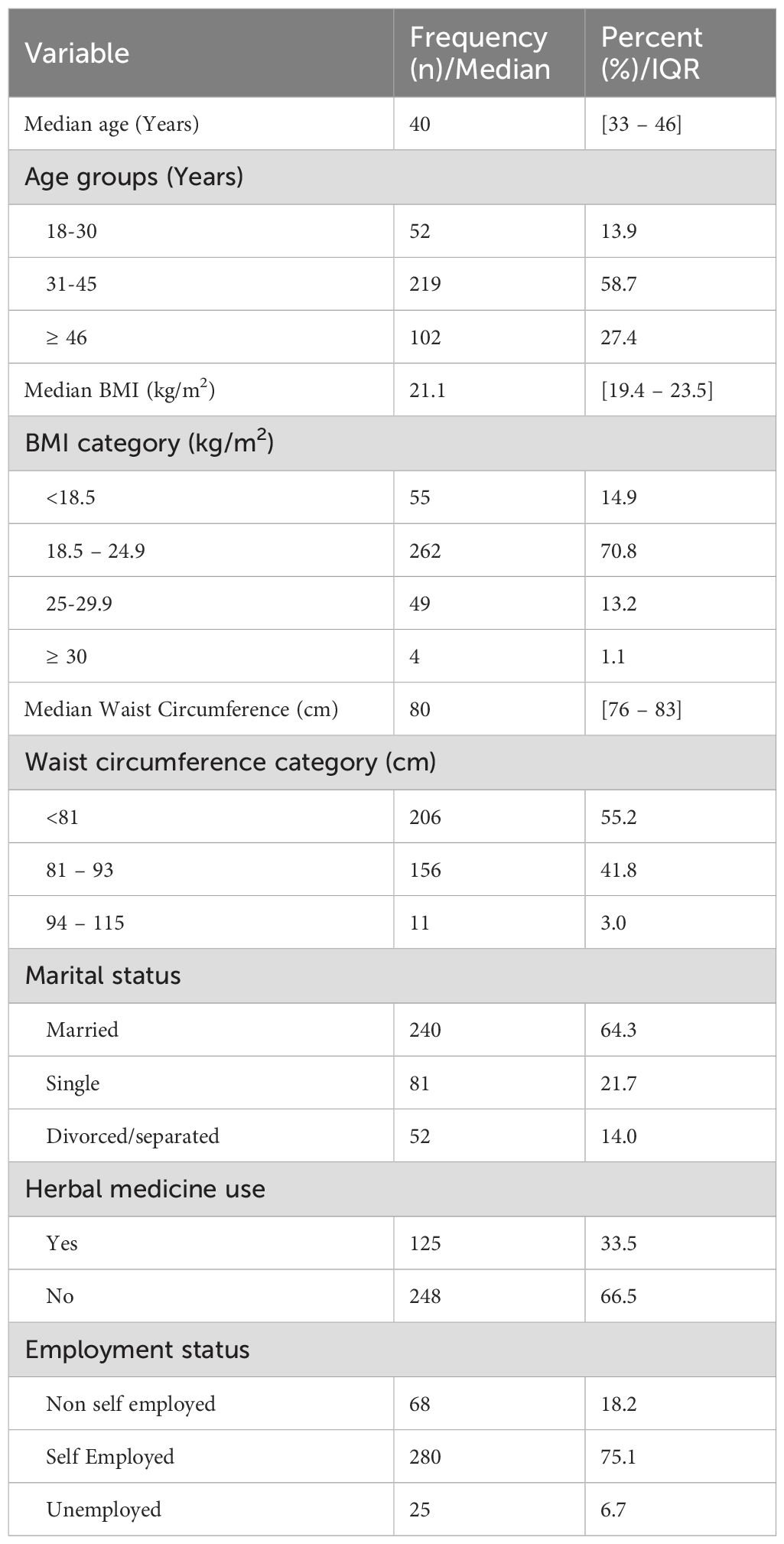

A total of 388 participants were enrolled in this study, however, the final analysis included 373 newly diagnosed ART naïve MLWH with a median age [IQR] of 40 [33–46] years. Fifteen participants were excluded from the final analysis as they did not complete the IIEF-5 questionnaire for ED assessment. Of the 373 participants, 35% (132/373) were from NDH, 29% (110/373), 28% (105/373) and 7.0% (26/373) from BMC, STRR and MDH respectively. The majority (58.7%, 219/373) of participants were in the age range 31–45 years, were married (64.3%, 240/373) and reported to have not used herbal medicine in the past six months (66.5%, 248/373). The median BMI and WC of the study participants were 21.1 [19.4–23.5] kg/m2 and 80 [76–83] cm respectively. About three-quarter of participants had BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 (normal), more than fifty percent had a WC of less than 81 cm (lower) and three-quarters, 75.1% (280/373) were self-employed (Table 1).

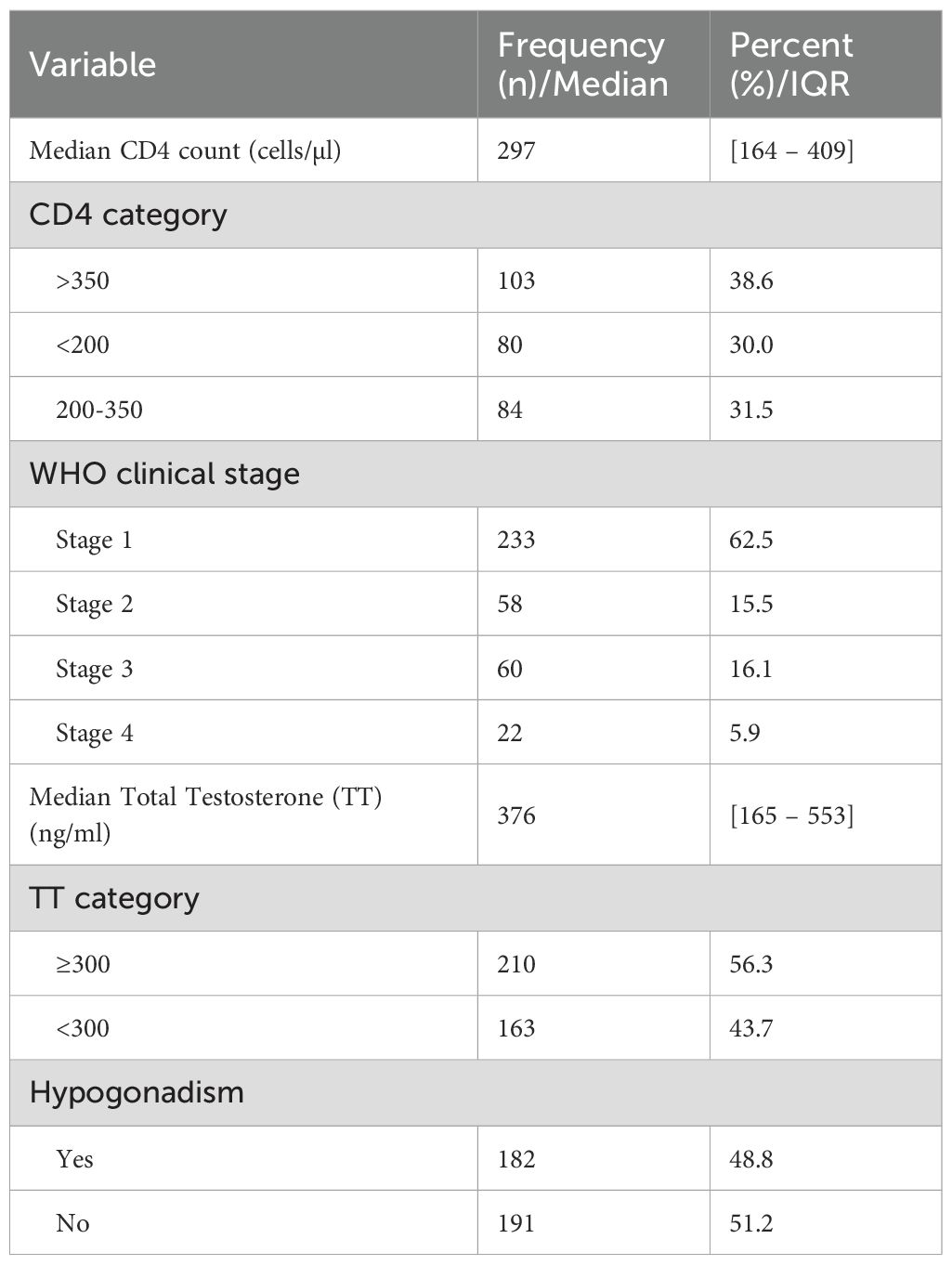

Clinical characteristics of study participants

Among 267 study participants who had CD4+ data, the median CD4+ count was 297 [164.0–409]. The majority, 62.5% (233/376) of the study participants were grouped in stage one of the disease according to World Health Organization HIV staging. The median testosterone was 376 [165–553] and the majority (56.3%, 210/373) had testosterone levels above normal. Hypogonadism was present in nearly half (48.8%, 182/373) of study participants (Table 2).

Prevalence of erectile dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction (ED) was found in 56.3% (95% CI 52.1%–61.3%)) of the study participants (Figure 1). Severe ED was observed in 7/210 (3.3%), moderate in 24/210 (11.4%), mild-moderate 84/210 (40.0%), and mild in 95/210 (45.2%) of the participants with ED, respectively (Figure 2). The median [IQR] of age was significantly higher among men with ED (41.0 [35–48] years) as compared with men without (38.0 [32-45] years) (p = 0.009) (Two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) while the median [IQR] of serum TT level was significantly lower among men with ED as compared to men without (294.5 [135–469] versus 482 [191–602] ng/ml; p< 0.001) (Two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) test). The median BMI, Waist circumference and CD4 count did not differ significantly between the two groups (Table 3).

Table 3. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants according to the erectile function status (N = 373).

Factors associated with erectile dysfunction among study participants

In the univariate analysis the independent variables associated with ED were non-self-employment status (COR 2.8; 95% CI 1.6–5.1; p = 0.001)), WHO clinical stage 4 of HIV infection (COR 3.3; 95% CI 1.2–9.3; p = 0.023)), low testosterone level (< 300) (COR 2.0; 95% CI 1.3–3.0; p = 0.001) and hypogonadism (COR 1.9; 95% CI 1.3–2.9; p = 0.003). Following multivariate logistic regression analysis, newly diagnosed ART naïve MLWH who were non-self-employed (AOR 3.7; 95% CI 2.0–7.0; p< 0.001) were four times more likely to develop ED as compared to self-employed MLWH, newly diagnosed ART naïve MLWH in WHO clinical stage 4 for HIV infection (AOR 3.2; 95% CI 1.1–9.2; p = 0.032) were three times more likely to develop ED as compared to those in WHO clinical stage 1 for HIV infection and newly diagnosed ART naïve MLWH with low testosterone level (< 300) (AOR 1.9; 95% CI 1.2–3.0; p = 0.010) were two times more likely to develop ED as compared to those with normal and above testosterone level. Univariate analysis, CD4+ count (COR 0.6; 95% CI 0.3–1.2; p = 0.136), and hypogonadism (COR 1.9; 95% CI 1.3–2.9; p = 0.003) were not subjected to multivariate logistic regression analysis due to collinearity with WHO clinical stage and Testosterone (TT) respectively (Table 4).

Table 4. Factors associated with erectile dysfunction among newly diagnosed ART naive HIV-infected males (Univariate and multivariate logistic regression).

Discussion

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a global public health concern owing to its negative impact on the well-being of individuals, families, and communities. In this study, the prevalence of ED among ART naïve MLWH was found to be 56.3% (95% CI 52.1%–61.3%). This prevalence is notably higher than the prevalence rate (29.7%) among adult men in the general population (44) but lower than the prevalence rate (74.6%) reported among MLWH from Northern Tanzania (45). This finding is similar to the report by Falade et al. in Nigeria (46), Moreno-perez et al. in Spain (2) and Crum cianflone et al. in the US (28) which reported the prevalence of 57%, 53.4% and 61.2% respectively. On the other hand, our finding was higher than 37.8% and 21.6% rates reported by Adebimpe et al. in Ogbomoso, Southwest Nigeria (35) and Gomes and Brites in Brazil (3) respectively. The variation in these prevalence rates could be attributed to the differences in the research instruments used in assessing ED, characteristics of the study populations as well as sociocultural and geographical differences. Hypogonadism is one of the major cause of erectile dysfunction and report from previous studies have shown the existence of racial/ethnic variations in sex/gonadal hormone which may be due to genetic factors, socio-demographic factors, cultural factors, and/or environmental factors/dietary variations (5, 47–50). Also different tools may be defining ED differently and this might affect the results by either under reporting or over reporting ED cases leading to variations in the finding between different studies (51). For example in a current study, International Index of Erectile Function-5 (IIEF-5) questionnaire with five scored questions (ED: total score< 22). was used but the previous study by Gomes and Brites (3) in Brazil used IIEF-15 questionnaire which have 15 questions (ED: total score< 26) and Adebimpe et al. (35) in Nigeria used just a pre-tested semi structured questionnaire with unscored questions about erectile function.

Regarding categories of ED according to severity among participants, of the 210 subjects with ED in our study, 95 (45.2%) were mild ED, 84 (40.0%) were mild to moderate ED, 24 (11.4%) were moderate ED and 7 (3.3%) had severe ED. A closely similar pattern was reported by Mbwambo et al. in Northern Tanzania (45) and Falade et al. in North central Nigeria (46) where mild, mild-moderate, moderate and severe ED in Tanzania were found in 37.7%, 26.2%, 5.7% and 4.9% patients respectively and in 64.9%, 24%, 8.2% and 2.9% patients respectively in Nigeria. However, in Brazil, Gomes and Brites (3) found that only 13.7% of participants had a mild presentation of ED, while the remaining 86.3% of the study subjects presented with severe ED. Also, in a study done by Enoma et al. in Malaysia (52), ED was almost evenly distributed across all severity grades with severe (24.1%), moderate (19.1%), mild to moderate (20.9%), and mild (18.3%). This variation in the pattern of ED could be due to the use of different patient group, with distinct epidemiological, social and clinical characteristics as different patient group may differ in terms of various factors such as age, comorbid conditions (such as Diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases), ART and other drug status, and life style habits of which have been also shown to have effect on gonadal hormone and erectile function (53–58). However, this requires further research for confirmation.

The risk factors for ED include vascular diseases, hypertension and obesity which are typically more common in the elderly population (59). Several studies have found a significant association between older age and the prevalence of ED (2, 16, 28, 35, 45), however, that was not detected in the current study. The study sample was relatively young (median age 40 [33–46] years) with the majority (58.7%) in the age range of 31 to 45 years. Furthermore, as most of the studies that report a significant association with age, involved HIV patients who were on ART, our study consisted of newly diagnosed ART naïve HIV males. Thus the previously reported relation of ED with young age and the association of ART with ED especially when the regimens contain protease inhibitors (21, 60, 61), could explain the observed discrepancy in this study. However, studies by Gomes and colleague (3) and Shindel et al. (30) among young HIV patients on ART (mean age 44 and 42 years, respectively) showed similar results but both studies included patients with comorbid conditions (Diabetes mellitus, Chronic pulmonary diseases, Hypertension) while Shindel et al. also included HIV-negative subjects in their study.

In our study, no significant association was found between marital status and ED. This finding corresponds to the reports by Gomez et al. (3) in Brazil, Mbwambo et al. (45) in Northern Tanzania, and Falade et al. (46) in Nigeria, and although is in contrast of those other studies which showed significant association between marital status and ED (58, 62–64). The finding from most previous studies with a significant association between marital status and ED indicated that single or divorced men were significantly associated with severe to moderate ED (62–64). Divorce/separation can involve significant changes in a person’s lifestyle, financial status, social connections and intimacy, which can negatively impact physical health including sexual health (62, 65). On the other hand, a study done in Thailand found that married men rate their sexual abilities better than single, divorced, separated, and widowed males (66). The variations in the findings could be due to differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between study groups, as our study involved men living with HIV which is similar for most of previous studies reporting no significant associations and there were a low number of divorced/separated men among our study participants.

In this study, an association between herbal medicine use and ED was not observed. In a previous report, herbal medicine use was found to be significantly associated with hypogonadism in newly diagnosed ART naïve HIV-infected males (67). As hypogonadism is reported to be one of the factors causing ED (22), a positive association between herbal medicine use and ED was anticipated. The lack of such an association between herbal medicine use and ED in this study could be attributed to the small number of participants who reported to use herbal medicine. The higher rate of participants not using herbal medicine recorded in our study could be due to regional variations and the fact that patients with debilitating/systemic diseases were excluded from the study.

Findings of the present study show that employment status is significantly associated with ED and this is in support of the findings of previous studies (3, 58). This finding suggests that the development of ED is prone to be affected by employment status. Particularly, non-self-employed men were 3.7 times more likely to develop ED as compared to self-employed men. This finding could be attributed to financial instability (financial insecurity) leading to stress and anxiety related disorders causing ED.

A statistically significant association was also found between WHO clinical stage (that determines the clinical progression of the disease) and ED whereby MLWH in WHO clinical stage 4 for HIV infection were three times more likely to develop ED as compared to those in stage 1. HIV infection causes impaired immunity with an associated decrease in CD4+ count leading to comorbid conditions, hence poor health status. This observation may be explained by the link between poor health status and impaired gonadal function (6, 68). This finding is in support of the reports by Crum-Cianflone et al., which showed that a higher CD4 count was protective against ED but contrary to the findings by Mbwambo et al. which showed a lack of association between CD4 and ED. This difference could be attributed to the variation in the clinical characteristics of study participants, such as ethnicity, ART status and the prevalence of hypogonadism. Studies have shown racial/ethnic variation in infection acquisition and CD4 cell count as well as viral load and therefore these might reflect the WHO clinical stage for HIV infection in different populations (69–72).

Furthermore, this study shows that nearly half of the study participants had hypogonadism. Several studies have also demonstrated an association between HIV and low serum testosterone (28, 73, 74). Contrary to the previous studies by De Vincentis et al. (23) and Mbwambo et al. (45), the current study revealed a significant association between ED and low testosterone. This discrepancy could be due to variation in the number of participants with low testosterone levels. HIV can cause low testosterone, although currently, the relationship between HIV and testosterone is a controversial one, as other studies have found normal testosterone levels in MLWH (68, 75).

Strengths and limitations

Limitations of this study include determination of ED only through self-report while it is recommended to establish ED diagnosis after a complete physical and psychological evaluation to determine vasculogenic or psychogenic factors (76, 77). However, ED in this study was determined using a validated IIF-5 questionnaire which is an internationally certified tool for assessing ED. The convenient sampling technique used in this study makes it prone to estimation bias and poor generalizability, however, this study was a multicenter study allowing generalization of the results. Measurement of gonadal hormones (TT, LH, FSH and estradiol) and socio-economic (employment) status allows assessment of both organic and psychological factors related to ED respectively. Also this study is limited by the use of TT to diagnose hypogonadism which can underestimate the prevalence of biochemical hypogonadism due to the possible rise in serum sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) in HIV patients. Measurement of SHBG has been highly recommended, in addition to LH and TT in these patients (78, 79). Another limitation of this study is that, testosterone levels were determined using an immune-assay technique, whereas mass-spectroscopy is often considered “gold-standard” but is not commonly used because it is expensive and not widely available. However, the immuno-chemiluminescence assay used in the determination of the gonadal hormone values in this study is internationally certified and widely used in clinical practice to diagnose and guide treatment in patients with gonadal dysfunction.

In addition, this study is limited by failure to rule out factors that may also cause erectile dysfunction (by affecting neuron functions) such as hypertension, other sexually transmitted infections like syphilis, gonorrhea and chlamydia. Further in the current study, we did not include other factors such as alcohol use, cigarette smoking and education status of which other studies have shown there is an association between them and ED (2, 16, 28, 46).

This was the first study on ED in HIV patients in Northwestern Tanzania, and provides information on risk factors and magnitude of ED in our setting. Also this study being done among newly diagnosed ART-naïve HIV males allows observation of the impact of chronic inflammation of the virus itself rather than the role of ART which was not distinguished in most of the previous studies. Further studies are required to compare ED between men who are HIV positive and those who are HIV negative and follow-up studies to compare before and after initiation of ARTs.

Conclusion

Slightly more than half of ART naïve MLWH were found to have ED with the majority presenting with a mild to mild-moderate form of ED. There was a significant association of ED with WHO clinical stage 4 for HIV infection, lower testosterone level, and being non self-employed. The results of this study emphasizes the need to include ED screening as part of the overall care of MLWH in CTC clinics as well as to strengthen the HIV screening program for early diagnosis and treatment to mitigate most of the observed risk factors for ED.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Joint Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences and Bugando Medical Center (CUHAS/BMC) research ethics and review committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SI: Data curation, Validation, Project administration, Conceptualization, Visualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. HD: Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision, Conceptualization. KM: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. BK: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. SK: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology, Visualization. DM: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of VCT centers and CTC clinics at BMC, STRRH, NDH, IDH and MDH for their valuable assistance during data collection; and laboratory technicians of the CUHAS multipurpose Laboratory and BMC Central Laboratory for their assistance in laboratory sample processing and analysis. The authors also wish to express their gratitude to all HIV-infected men who agreed to participate in this study. This work was supported by Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences as part of PhD study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Cohan P and Korenman SG. Erectile dysfunction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2001) 86:2391–4. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7576

2. Perez I, Moreno T, Navarro F, Santos J, and Palacios R. Prevalence and factors associated with erectile dysfunction in a cohort of HIV-infected patients. Int J STD AIDS. (2013) 24:712–5. doi: 10.1177/0956462413482423

3. Gomes TV and Brites C. Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in HIV-infected patients in Salvador, Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis. (2019) 23:464–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2019.08.006

4. Faramarzia H, Marzban M, AminiLari M, and Shams M. Hypogonadism and associated factors in patients with HIV infection based on total and free testosterone. Shiraz E-Medical J. (2014) 15:1–7. doi: 10.17795/semj19734

5. Klein RS, Lo Y, Santoro N, and Dobs AS. Androgen levels in older men who have or who are at risk of acquiring HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. (2005) 41:1794–803. doi: 10.1086/498311

6. De Vincentis S, Decaroli MC, Fanelli F, Diazzi C, Mezzullo M, Morini F, et al. Health status is related to testosterone, estrone and body fat: moving to functional hypogonadism in adult men with HIV. Eur J Endocrinol. (2021) 184:107–22. doi: 10.1530/EJE-20-0855

7. Roberson DW and Kosko DA. Men living with HIV and experiencing sexual dysfunction: an analysis of treatment options. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. (2013) 24:S135–S45. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.08.010

8. Blick G. Optimal diagnostic measures and thresholds for hypogonadism in men with HIV/AIDS: comparison between 2 transdermal testosterone replacement therapy gels. Postgrad Med. (2013) 125:30–9. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2013.03.2639

9. Engelson ES, Rabkin JG, Rabkin R, and Kotler DP. Effects of testosterone upon body composition. JAIDS J Acquired Immune Def Syndromes. (1996) 11:510,1. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199604150-00012

10. Grinspoon SK and Bilezikian JP. HIV disease and the endocrine system. N Engl J Med. (1992) 327:1360–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199211053271906

11. Rietschel P, Corcoran C, Stanley T, Basgoz N, Klibanski A, and Grinspoon S. Prevalence of hypogonadism among men with weight loss related to human immunodeficiency virus infection who were receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. (2000) 31:1240–4. doi: 10.1086/317457

12. Staiman VR and Lowe FC. Urologic problems in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Sci World J. (2004) 4:427. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2004.84

13. Amini Lari M, Parsa N, Marzban M, Shams M, and Faramarzi H. Depression, testosterone concentration, sexual dysfunction and methadone use among men with hypogonadism and HIV infection. AIDS Behav. (2012) 16:2236–43. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0234-x

14. Hart TA, Moskowitz D, Cox C, Li X, Ostrow DG, Stall RD, et al. The cumulative effects of medication use, drug use, and smoking on erectile dysfunction among men who have sex with men. J Sex Med. (2012) 9:1106–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02648.x

15. Laudat A, Blum L, Guéchot J, Picard O, Cabane J, Imbert JC, et al. Changes in systemic gonadal and adrenal steroids in asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus-infected men: relationship with the CD4 cell counts. Eur J Endocrinol. (1995) 133:418–24. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1330418

16. Fumaz CR, Ayestaran A, Perez-Alvarez N, Muñoz-Moreno JA, Ferrer MJ, Negredo E, et al. Clinical and emotional factors related to erectile dysfunction in HIV-infected men. Am J Men’s Health. (2017) 11:647–53. doi: 10.1177/1557988316669041

17. de Tubino Scanavino M and Abdo CHN. Sexual dysfunctions among people living with AIDS in Brazil. Clinics. (2010) 65:511–9. doi: 10.1590/51807-593220010000500009

18. Roozbeh N, Rostami S, and Abdi F. A review on herbal medicine with fertility and infertility characteristics in males. Iranian J Obstetrics Gynecol Infertil. (2016) 19:18–32. doi: 10.22038/ijogi.2016.7278

19. Kimambo SJ. 252 Acceptance of and adherence to anti-retroviral therapy in Tanzania: the influence of lipodystrophy and of traditional medicine. JAIDS J Acquired Immune Def Syndromes. (2009) 51. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000351207.62305.78

20. Peltzer K, Preez NF-D, Ramlagan S, and Fomundam H. Use of traditional complementary and alternative medicine for HIV patients in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Public Health. (2008) 8:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-255

21. Ende AR, Re VL III, DiNubile MJ, and Mounzer K. Erectile dysfunction in an urban HIV-positive population. AIDS Patient Care STDs. (2006) 20:75–8. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.75

22. Crum NF, Furtek KJ, Olson PE, Amling CL, and Wallace MR. A review of hypogonadism and erectile dysfunction among HIV-infected men during the pre-and post-HAART eras: diagnosis, pathogenesis, and management. AIDS Patient Care STDs. (2005) 19:655–71. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.655

23. De Vincentis S, Decaroli M, Diazzi C, Morini F, Bertani D, Fanelli F, et al eds. Testosterone (T) is poorly related to sexual desire and Erectile Dysfunction (ED) in Young/Middle Aged Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-Infected Men. In: Endocrine Abstracts. Bioscientifica Ltd.

24. Asboe D, Catalan J, Mandalia S, Dedes N, Florence E, Schrooten W, et al. Sexual dysfunction in HIV-positive men is multi-factorial: a study of prevalence and associated factors. AIDS Care. (2007) 19:955–65. doi: 10.1080/09540120701209847

25. Collazos J, Martínez E, Mayo J, and Ibarra S. Sexual dysfunction in HIV-infected patients treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. JAIDS J Acquired Immune Def Syndromes. (2002) 31:322–6. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200211010-00008

26. Zhang H, Dornadula G, Beumont M, Livornese L, Van Uitert B, Henning K, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in the semen of men receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. (1998) 339:1803–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812173392502

27. Cove J and Petrak J. Factors associated with sexual problems in HIV-positive gay men. Int J STD AIDS. (2004) 15:732–6. doi: 10.1258/0956462042395221

28. Crum-Cianflone NF, Bavaro M, Hale B, Amling C, Truett A, Brandt C, et al. Erectile dysfunction and hypogonadism among men with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs. (2007) 21:9–19. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0071

29. Driemeier M, de Andrade SMO, Pontes ERJC, Paniago AMM, and da Cunha RV. Vulnerability to AIDS among the elderly in an urban center in central Brazil. Clinics. (2012) 67:19–25. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2012(01)04

30. Shindel AW, Horberg MA, Smith JF, and Breyer BN. Sexual dysfunction, HIV, and AIDS in men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDs. (2011) 25:341–9. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0059

31. Catalan J and Meadows J. Sexual dysfunction in gay and bisexual men with HIV infection: evaluation, treatment and implications. AIDS Care. (2000) 12:279–86. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042927

32. van Griensven F, Thienkrua W, Sukwicha W, Wimonsate W, Chaikummao S, Varangrat A, et al. Sex frequency and sex planning among men who have sex with men in Bangkok, Thailand: implications for pre-and post-exposure prophylaxis against HIV infection. J Int AIDS Soc. (2010) 13:13–. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-13

33. De Ryck I, Van Laeken D, Apers L, and Colebunders R. Erectile dysfunction, testosterone deficiency, and risk of coronary heart disease in a cohort of men living with HIV in Belgium. J Sex Med. (2013) 10:1816–22. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12175

34. Singh AS and Masuku MB. Sampling techniques & determination of sample size in applied statistics research: An overview. Int J Econ Commerce Manage. (2014) 2:1–22.

35. Adebimpe W, Omobuwa O, and Adeoye O. Prevalence and predictors of erectile dysfunctions among men on antiretroviral therapy in south−western Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res. (2015) 5:279–83.

36. Rosen RC, Cappelleri J, Smith M, Lipsky J, and Pena B. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. (1999) 11:319. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900472

37. Cappelleri JC, Rosen RC, Smith MD, Mishra A, and Osterloh IH. Diagnostic evaluation of the erectile function domain of the International Index of Erectile Function. Urology. (1999) 54:346–51. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)00099-0

38. Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, and Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. (1997) 49:822–30. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00238-0

39. Rosen R and Cappelleri J. The sexual health inventory for men (IIEF-5): reply to Vroege. Int J Impot Res. (2000) 12:342–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900615

40. Pallangyo P, Nicholaus P, Kisenge P, Mayala H, Swai N, and Janabi M. A community-based study on prevalence and correlates of erectile dysfunction among Kinondoni District Residents, Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. Reprod Health. (2016) 13:140. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0249-2

41. Rhoden E, Telöken C, Sogari P, and Souto CV. The use of the simplified International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool to study the prevalence of erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. (2002) 14:245. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900859

42. Rochira V, Zirilli L, Orlando G, Santi D, Brigante G, Diazzi C, et al. Premature decline of serum total testosterone in HIV-infected men in the HAART-era. PLoS One. (2011) 6:e28512. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028512

43. Bajaj S, Pathak Y, Varma S, and Verma S. Metabolic status and hypogonadism in human immunodeficiency virus-infected males. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. (2017) 21:684. doi: 10.4103/ijem.IJEM_127_17

44. Nyalile KB, Mushi EH, Moshi E, Leyaro BJ, Msuya SE, and Mbwambo O. Prevalence and factors associated with erectile dysfunction among adult men in Moshi municipal, Tanzania: community-based study. Basic Clin Androl. (2020) 30:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12610-020-00118-0

45. Mbwambo OJ, Lyatuu M, Ngocho G, Abdallah K, Godfrey P, Ngowi BN, et al. The high burden of erectile dysfunction among men living with HIV in northern Tanzania: a call for evidence-based interventions. Front Urol. (2023) 3:1238293. doi: 10.3389/fruro.2023.1238293

46. Falade O, Kofoworade AY, Ojedokun SA, Amoko A, Alabi KM, and Odeigah LO. Prevalence and pattern of erectile dysfunction among people living with HIV/AIDS in a tertiary hospital in north-central Nigeria. Int J Trop Dis Health. (2023) 44:9–16. doi: 10.9734/ijtdh/2023/v44i31391

47. Punjani N, Nayan M, Jarvi K, Lo K, Lau S, and Grober ED. The effect of ethnicity on semen analysis and hormones in the infertile patient. Can Urol Assoc J. (2020) 14:31. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.5897

48. Hu H, Odedina FT, Reams RR, Lissaker CT, and Xu X. Racial differences in age-related variations of testosterone levels among US males: potential implications for prostate cancer and personalized medication. J Racial Ethnic Health Disparities. (2015) 2:69–76. doi: 10.1007/s40615-014-0049-8

49. Richard A, Rohrmann S, Zhang L, Eichholzer M, Basaria S, Selvin E, et al. Racial variation in sex steroid hormone concentration in black and white men: a meta-analysis. Andrology. (2014) 2:428–35. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-2927.2014.00206.x

50. Ahn J, Schumacher FR, Berndt SI, Pfeiffer R, Albanes D, Andriole GL, et al. Quantitative trait loci predicting circulating sex steroid hormones in men from the NCI-Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium (BPC3). Hum Mol Genet. (2009) 18:3749–57. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp302

51. De Boer B, Bots M, Lycklama A, Nijeholt A, Moors J, Pieters H, et al. Impact of various questionnaires on the prevalence of erectile dysfunction. The ENIGMA-study. Int J Impot Res. (2004) 16:214–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901053

52. Enoma A, Ching SM, Hoo FK, and Omar SFS. Prevalence and factors associated with erectile dysfunction in male patients with human immunodeficiency virus in a teaching hospital in West Malaysia. Med J Malaysia. (2017) 72:186–9. doi: 10.5555/20183035810

53. Mazzilli F. Erectile dysfunction: causes, diagnosis and treatment: an update. MDPI;. (2022) p:6429. doi: 10.3390/jcm11216429

54. Nicolosi A, Moreira ED Jr., Shirai M, Tambi MIBM, and Glasser DB. Epidemiology of erectile dysfunction in four countries: cross-national study of the prevalence and correlates of erectile dysfunction. Urology. (2003) 61:201–6. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(02)02102-7

55. Gandaglia G, Briganti A, Jackson G, Kloner RA, Montorsi F, Montorsi P, et al. A systematic review of the association between erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular disease. Eur Urol. (2014) 65:968–78. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.08.023

56. Fedele D, Coscelli C, Santeusanio F, Bortolotti A, Chatenoud L, Colli E, et al. Erectile dysfunction in diabetic subjects in Italy. Gruppo Italiano Studio Deficit Erettile nei Diabetici. Diabetes Care. (1998) 21:1973–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.11.1973

57. Rastrelli G, Corona G, Mannucci E, and Maggi M. Vascular and chronological age in men with erectile dysfunction: a longitudinal study. J Sex Med. (2016) 13:200–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2015.11.014

58. Mark R, Huri HZ, and Razack AHA. Demographic, clinical and lifestyle predictors for severity of erectile dysfunction and biomarkers level in Malaysian patients. Braz J Pharm Sci. (2018) 54:e17552. doi: 10.1590/s2175-97902018000317552

59. Gareri P, Castagna A, Francomano D, Cerminara G, and De Fazio P. Erectile dysfunction in the elderly: an old widespread issue with novel treatment perspectives. Int J Endocrinol. (2014) 2014:878670. doi: 10.1155/2014/878670

60. Guaraldi G, Luzi K, Murri R, Granata A, Paola MD, Orlando G, et al. Sexual dysfunction in HIV-infected men: role of antiretroviral therapy, hypogonadism and lipodystrophy. Antiviral Ther. (2007) 12:1059–66. doi: 10.1177/135965350701200713

61. Schrooten W, Colebunders R, Youle M, Molenberghs G, Dedes N, Koitz G, et al. Sexual dysfunction associated with protease inhibitor containing highly active antiretroviral treatment. Aids. (2001) 15:1019–23.

62. Rezali MS, Mohamad Anuar MF, Abd Razak MA, Chong ZL, Shaharudin AB, Kassim MSA, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of moderate to severe erectile dysfunction among adult men in Malaysia. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:21483. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-48778-y

63. Calzo JP, Austin SB, Charlton BM, Missmer SA, Kathrins M, Gaskins AJ, et al. Erectile dysfunction in a sample of sexually active young adult men from a US cohort: demographic, metabolic and mental health correlates. J Urol. (2021) 205:539–44. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001367

64. Chew K-K, Stuckey B, Bremner A, Earle C, and Jamrozik K. Male erectile dysfunction: Its prevalence in Western Australia and associated sociodemographic factors. J Sex Med. (2008) 5:60–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00548.x

65. Pellón-Elexpuru I, Van Dijk R, van der Valk I, Martínez-Pampliega A, Molleda A, and Cormenzana S. Divorce and physical health: A three-level meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. (2024) 352:117005. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2024.117005

66. Kongkanand A and Group TEDES. Prevalence of erectile dysfunction in Thailand. Int J Androl. (2000) 23:77–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.2000.00022.x

67. Iddi S, Dika H, Kidenya B, and Kalluvya S. Prevalence of hypogonadism and associated risk factors among newly diagnosed ART naïve HIV-infected males in mwanza, Tanzania. Int J Endocrinol. (2024) 2024:9679935. doi: 10.1155/2024/9679935

68. Rochira V, Diazzi C, Santi D, Brigante G, Ansaloni A, Decaroli MC, et al. Low testosterone is associated with poor health status in men with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a retrospective study. Andrology. (2015) 3:298–308. doi: 10.1111/andr.310

69. Swindells S, Cobos DG, Lee N, Lien EA, Fitzgerald AP, Pauls JS, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in CD4 T cell count and viral load at presentation for medical care and in follow-up after HIV-1 infection. AIDS. (2002) 16:1832–4. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200209060-00020

70. Achhra AC and Amin J. Race and CD4+ T-cell count in HIV prognosis and treatment. Future Virol. (2012) 7:193–203. doi: 10.2217/fvl.11.143

71. Avendano EE, Blackmon SA, Nirmala N, Chan CW, Morin RA, Balaji S, et al. Race, ethnicity and risk for colonisation and infection with key bacterial pathogens: a scoping review. BMJ Global Health. (2025) 10:1–13. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2024-017404

72. Nadimpalli ML, Chan CW, Doron S, Jacque B, and Bascom-Slack C. 17157 Racial/ethnic disparities in antibiotic-resistant infections: Knowledge gaps and opportunities for educational interventions. J Clin Trans Sci. (2021) 5:77. doi: 10.1017/cts.2021.601

73. Scanavino MDT. Sexual dysfunctions of HIV-positive men: associated factors, pathophysiology issues, and clinical management. Adv Urol. (2011) 2011:854792. doi: 10.1155/2011/854792

74. De Vincentis S, Tartaro G, Rochira V, and Santi D. HIV and sexual dysfunction in men. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:1088. doi: 10.3390/jcm10051088

75. Monroe AK, Dobs AS, Palella FJ, Kingsley LA, Witt MD, and Brown TT. Morning free and total testosterone in HIV-infected men: implications for the assessment of hypogonadism. AIDS Res Ther. (2014) 11:1–5. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-11-6

76. Cavallini G. Resolution of erectile dysfunction after an andrological visit in a selected population of patients affected by psychogenic erectile dysfunction. Asian J Androl. (2017) 19:219–22. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.172646

77. Kellesarian SV, Kellesarian TV, Ros Malignaggi V, Al-Askar M, Ghanem A, Malmstrom H, et al. Association between periodontal disease and erectile dysfunction: a systematic review. Am J Men’s Health. (2018) 12:338–46. doi: 10.1177/1557988316639050

78. De Vincentis S, Decaroli MC, Fanelli F, Diazzi C, Mezzullo M, Tartaro G, et al. Primary, secondary and compensated male biochemical hypogonadism in people living with HIV (PLWH): relevance of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) measurement and comparison between liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and chemiluminescent immunoassay for sex steroids assay. Aging Male. (2022) 25:41–53. doi: 10.1080/13685538.2022.2039116

Keywords: HIV, antiretroviral naïve males, erectile dysfunction, associated factors, Tanzania

Citation: Iddi S, Matovelo D, Marwa KJ, Kidenya BR, Dika H and Kalluvya SE (2025) Prevalence of erectile dysfunction and associated factors among newly diagnosed ART naïve men living with HIV: a cross sectional study in Mwanza, Northwestern Tanzania. Front. Urol. 5:1657553. doi: 10.3389/fruro.2025.1657553

Received: 01 July 2025; Accepted: 29 August 2025;

Published: 16 September 2025.

Edited by:

Diego Ripamonti, Papa Giovanni XXIII Hospital, ItalyReviewed by:

Mohammed Abu El-Hamd, Sohag University, EgyptJerman Dereje, Haramaya University, Ethiopia

Copyright © 2025 Iddi, Matovelo, Marwa, Kidenya, Dika and Kalluvya. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shabani Iddi, c2hhYnNpenlhMjAwN0B5YWhvby5jby51aw==

Shabani Iddi

Shabani Iddi Dismas Matovelo2

Dismas Matovelo2 Benson R. Kidenya

Benson R. Kidenya Haruna Dika

Haruna Dika Samuel E. Kalluvya

Samuel E. Kalluvya