- Centre for Migration Law, Faculty of Law, Radboud University, Nijmegen, Netherlands

Traveling freely, smoothly and unburdened by excessive formalities and the adjoining right to reside in another EU state for work, leisure or study are the hallmarks of the mobility regime applicable to EU citizens and their family members. Measures taken by the majority of EU states to deal with Covid-19 have severely disrupted EU mobility and led to the reestablishment of internal border controls, the introduction of restrictions to travel and even travel bans. These obstacles to mobility have highlighted the EU economy's reliance on EU migrant labor in several sectors, which was further exacerbated by the introduction of an EU travel ban at the external border. This contribution discusses measures taken by Romania that sought to restrict travel to and from Romania, while simultaneously allowing exceptions for nationals to travel to other EU states as essential workers. The Romanian response is discussed in relation to the wider EU attempts to reply to the proliferation of national measures affecting EU free movement and the functioning of the internal market and as an illustration of the need to ensure that mobility goes hand in hand with protection.

Introduction

The right to free movement is generally understood to be the best known and valued right of EU citizenship. Traveling freely, smoothly and unburdened by excessive formalities and the adjoining right to reside in another EU state for work, leisure or study are the hallmarks of the mobility regime applicable to EU citizens and their family members which sets them apart from nationals of third countries (TCNs). EU citizens can enter other EU states by simply producing a valid ID card or passport and reside there for an initial period of 3 months without meeting further conditions. Working in another EU state is not conditioned by a work permit or quotas and mobile EU workers are entitled to equal treatment with national workers as a matter of EU law (Article 45 TFEU). The abolition of internal border controls within the Schengen area coupled with the precedence given to EU free movement rules by the Schengen Border Code, including when crossing external borders, provide further evidence of the privileged position enjoyed by EU citizens.

Yet, for the best part of 2020, the reestablishment of internal border controls and the introduction of restrictions or outright bans on travel in response to the Covid-19 pandemic have severely affected EU citizens' right to move freely. Reports of EU citizens blocked or stranded at internal Schengen borders as a result of national border closure measures raise questions about the added value of EU citizenship and of the right to free movement in times of crisis. The initial lack of a quick EU response to the proliferation of national restrictive measures raised similar questions. Moreover, the closure of EU internal borders has highlighted the reliance of the EU economy on migrant EU labor, which was further exacerbated by the introduction of an EU travel ban at the external border.

In this contribution, I take Romania as a case study to examine some of the practical implications of the restriction of the right to free movement. Romania has been an EU state since 2007. According to Eurostat (2020), Romanians of working age (20–64) are by far the largest national group among mobile EU citizens, most of which move for labor purposes. Since the start of the pandemic, mobile Romanians have been affected by measures taken at both EU and national levels. Firstly, the contribution sketches the EU response to the proliferation of national measures restricting mobility to show that EU citizens continued to be treated as privileged migrants, although internally this was most visible when moving as EU workers. Secondly, the contribution discusses measures taken by Romanian authorities during the months of March, April, May and June 2020. These measures sought on one hand, to restrict the mobility of Romanian citizens, while on the other hand, they allowed exceptions so that Romanians could be flown via air corridors to work in other EU states as “essential” workers. The later aspect is a practical illustration of EU guidelines that emphasized the need to keep the EU economy going by allowing the mobility EU workers exercising critical occupations, and of their limitations in terms of ensuring that said workers are not abused, exploited or harmed. Seen from this perspective, the Romanian example highlights the need to start an EU-wide conversation on how to better arrange the protection of mobile EU workers and citizens between the national and EU levels.

Eu Citizens During Covid-19: Still Privileged Migrants?

While in the past EU states have made use of existing possibilities to derogate from free movement rules to re-introduce internal border controls, Member State responses to the Covid-19 pandemic have led to an unprecedented closure of internal and EU external borders with a profound impact on the EU systems of free movement and border management (Montaldo, 2020). In the face of mounting national responses derogating from the normally applicable rules with far-reaching consequences for the economy, the EU attempted to come up with an at least coordinated, if not, unified response to mobility into and within the EU.

Generally speaking, the EU response has been questioned for its failure to scrutinize the legality and proportionality of national restrictive measures from the perspective of EU law (Carrera and Chun Luk, 2020). Nevertheless, there was an attempt to do justice to the privileged treatment normally enjoyed by EU citizens and their family members. In relation to the EU external border and travel into the EU+ area, the Member States were called to introduce temporary restrictions for non-essential travel from third-countries between March and June 2020, when the Council recommended the gradual lifting of temporary travel restrictions for selected countries in light of the epidemiological situation (European Commission, 2020a,d). The introduction of restrictions was linked to the obligation for the Member States to admit their own citizens in line with their obligations under international law (European Commission, 2020a, p. 2). Moreover, the Member States were equally instructed to allow entry into the EU+ area and facilitate onward transit for EU citizens and their family members irrespective of nationality and for TCNs holding a residence permit and their dependents who were returning to their Member State of nationality or residence (European Commission, 2020b). EU efforts to facilitate and coordinate policy measures aimed at ensuring that EU citizens can return home are illustrative of its ongoing efforts to develop through legislative measures the EU right to consular protection (Article 20/c TFEU) for EU citizens present in the territory of third countries as an extra source of protection derived from EU citizenship and functioning alongside state nationality (Mantu, 2020).

While EU citizens continued to enjoy privileged treatment in relation to the crossing of the external EU border with a view to return home, their treatment in relation to intra-EU mobility is more problematic. According to Thym (2020) even if restrictive measures, including travel bans, can be justified within the Schengen area under the public health exception as a matter of principle, there is still an obligation for such measures and their practical implementation to comply with relevant EU law and Court of Justice jurisprudence limiting state discretion in this area.

Instead of scrutinizing national measures affecting intra-EU mobility for compliance with EU law standards, the EU response focused on safeguarding economic interests and the functioning of the internal market. The restriction of intra-EU mobility and the EU travel ban for TCNs showed the essential role played by migrant workers in the economy, with several sectors standing to be severely disrupted as a result of the lack of migrant labor (Fasani and Mazza, 2020). The Commission adopted several communications designating workers exercising critical occupations as special categories of persons whose mobility should not be hindered (European Commission, 2020c). EU citizens retained their privileged position in as much as they performed critical and essential work.

“Critical workers” are defined based on the European Skills, Competences, Qualifications and Occupations (ESCO) classification and include a variety of occupations at all levels of skills, from health professionals, to scientists in health-related industries to food manufacturing and processing and related trades maintenance workers or, transport workers. As a novelty, this category of workers in critical occupations breaks through existing divisions in the legal regimes applicable to posted and regular workers. It combines regular mobile workers, frontier workers and posted workers, and in certain circumstances seasonal workers, if performing crucial functions. Agriculture and the food industry proved particularly vulnerable in some EU states, which explains why seasonal workers in agriculture, if performing critical harvesting, planting or tending functions, are assimilated to workers exercising critical occupations (European Commission, 2020c: 9&10). The Commission advised the Member States to create burden-free and fast procedures for border crossings with a regular flow of frontier and posted workers as well as establish specific procedures for seasonal workers (European Commission, 2020c), which several EU states did, including Romania.

Romania: Labor Mobility During Lock-Down

Romania has relied on the special procedures (e.g., air corridors) advised by the European Commission to allow its nationals to work in other EU states as essential workers, mainly in agriculture and the meat industry. An EU state since 2007, Romania is a country of emigration, with an estimated 3 million Romanians having left the country to work abroad relying on their EU right to free movement. Italy, Spain, Germany, France and UK are main destinations. Covid-19 related measures adopted in these countries had an impact on mobile Romanians. For example, the Italian lock down measures had negative consequences for Romanian workers some of which lost their jobs. During early March, Romanian authorities started to repatriate Romanians from Italy and press releases issued by the Romanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs around this time confirm that many were Romanians who had lost their jobs and who lacked financials means to return home. Likewise, Romanians who were in transit or on vacation were unable to leave Italy since commercial flights between Italy and Romania were suspended by Romanian authorities in February 2020 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2020a). Romanian truck drivers and road travelers got blocked in Austria and Hungary, as a result of national quarantine or lock down measures requiring the intervention of Romanian authorities to negotiate bilateral solutions with their EU counterparts (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2020b).

At the same time, Romanian media circulated stories about Romanians dying of Covid-19 in Italy. Fear of a mass exodus of Romanians returning from Italy and bringing with them the virus started to influence public opinion leading to a wave of hate toward them (Udisteanu, 2020). The deteriorating healthcare situation, the unpreparedness of the national healthcare system and the fear of returning Romanians all played a part in the decision of the Romanian President to declare a national state of emergency for 30 days as of 16 March 2020 (Decret al Preşedintelui României nr. 195), which was extended for another 30 days until the 15th of May. The state of emergency allowed for an unprecedented restriction of rights and liberties, including freedom of movement, the right to private and family life, the inviolability of domicile, the right to education, freedom of association, the right to private property, the right to strike and economic freedom. Other envisaged measures included isolation and quarantine for persons coming from high risk areas, gradual closure of border crossings, restriction or prohibition of road, rail, maritime, water and air travel.

During the state of emergency, the Minister of Internal Affairs issued 12 military ordinances (MO) containing measures for preventing the spread of Covid-19 that affected all persons entering or leaving Romania. Commercial flights to and from most EU countries were suspended; later this extended partly to international road traffic (Military Ordinance no. 1 of 18 March 2020; Military Ordinance no. 4 of 29 March 2020). The entry through border crossing points of foreigners and stateless persons was prohibited except if they transited Romania through corridors organized by agreement with neighboring countries. In line with the EU position, exceptions were introduced for certain categories of TCNs and stateless persons (Military Ordinance no. 2 of 21 March 2020). On the 24th of March, Romania entered a lock down and the military was called to support police and Gendarmerie personnel in enforcing the new restrictions. Movement outside one's home or household was prohibited, with some exceptions, such as working, and buying food. Likewise, home isolation or institutional quarantine (in case of symptoms) was introduced for all persons entering Romania (Military Ordinance no. 3 of 24 March 2020).

At the height of the national lock down, the Romanian authorities decided to allow the transport of seasonal workers from Romania to other states with the approval of the competent authorities of the country of destination via irregular flights (charters), including toward EU states with whom international air and road transport of persons was suspended (Military Ordinance no. 7 of 4 April 2020). Days later Romanian media showed chaotic images of about 1,800 Romanians amassed in the parking lot of the regional airport in Cluj-Napoca without any respect for social distancing measures waiting to be flown to Germany where they were eagerly awaited to start picking asparagus and strawberries. In light of this public embarrassment, Military Ordinance no. 8 of 9 April introduced the obligation to obtain the approval of the Romanian authorities for the transport of seasonal workers from Romania to another state via charters but failed to detail the procedure itself.

Quarantine measures for persons entering Romania, partial closure of border crossing points and of international road, rail, maritime and air travel remained applicable after 15 May 2020 when Romania entered a state of alert (Decision no 24 from 14.05.2020 and its annexes; Decision no. 476 from 16.06.2020 and its annexes). During the months of May and June 2020, the exceptions for critical seasonal workers were maintained and, gradually, expanded due to an improved epidemiological situation in Romania and elsewhere. These exceptions follow EU guidelines as well as an economic logic. Concerning the transportation of seasonal workers more requirements were introduced, e.g., to operate such a charter flight, the authorizations of Romanian Civil Aeronautical Authority and of the competent authorities in the destination state are needed (Article 10 Decision no. 24 from 14.05.2020). A further exception was introduced for charter flights repatriating Romanian citizens and for charter flights transporting international transport workers in line with EU guidelines [Annex 3 to C(2020) 1897 from 23.03.2020].

Although international road transport for persons to and from several EU states was suspended until 1 June 2020, an exception was introduced for the benefit of workers with a valid contract, persons holding a residence permit from those states or persons returning to Romania from the state where they worked or lived (Article 11 Decision no. 24 from 14.05.2020). Occasional road transport was allowed for the above categories provided that: all necessary authorizations for all transited states were present, the Romanian authorities were informed about the future travel and the transport company, the recruitment agency and the transported persons comply with health and safety measures (incl. social distancing) during travel. From the legal text it is unclear if this provision concerns seasonal workers or it applies to all workers; the exception concerning chapter flights is clearly about seasonal workers. As of the 1st June 2020, the Romanian government started to relax travel restrictions and opened up international travel by rail, road (Decision no. 26, 28.05.2020) and, for some EU countries, air travel as of 15 June 2020 coupled with lifting off quarantine/isolation measures for persons traveling from those countries (Decision no. 29 from 13.06.2020). The possibility to reintroduce restrictions to travel and quarantine measures remains an option linked to the evolution of the epidemiological situation.

Economy V. Protection

The Romanian case offers an opportunity to study the interaction between the EU level response that emphasized the need to keep the EU economy going despite the closure of borders, and national measures that were concerned primarily with preventing the spread of Covid-19. The decision of the Romanian authorities to open air corridors for seasonal workers should be understood in light of the number of Romanians who have returned from abroad as a result of Covid-19 measures taken by other EU states. In a video conference held in May 2020 the Romanian prime minister stated that since 23 February 2020, when the government started to monitor the situation more closely, about 1,279,000 Romanians had entered mainly from European states badly hit by the pandemic (Italy, Spain, Germany, France and UK) and that according to estimates about 300,000–350,000 would be looking for a job in Romania (Agerpres, 2020a). He equally confirmed that the decision to close the borders was linked with fears that the large Romanian diaspora would return en masse due to economic hardship in their host states. At the same time, the national lock down had an important economic impact with more than 1 million Romanians benefiting from technical unemployment payments in April 2020 (Radioa Europa Libera, 2020a) and a national labor market that was contracting; unemployment is expected to reach 6.5% in 2020 as opposed to 3.9% in 2019 (Radio Europa Libera, 2020b). The expectation of Romanian authorities and other experts was that the majority of the 1.3 million Romanians had returned “home” temporarily, to weather the crisis, and, when possible, they would leave again (Dobreanu, 2020).

Initially, the Romanian government showed no interest in safeguarding the health and safety of those Romanians whom it allowed to leave the country. At first, recruitment companies were not required to announce Romanian authorities about the number of workers who had been recruited as seasonal workers, nor to attest to their state of health or provide information as to where exactly they would work in other EU states. No provisions were made to deal with seasonal workers upon their return to Romania, who at that point in time should have been placed in quarantine, nor was it clear what should happen to them if contracting the virus. A parliamentary inquiry into the incident at the Cluj-Napoca airport confirmed that at the time there was a legislative void concerning the mobility of seasonal workers (Agerpres, 2020b). While later measures introduced more requirements for transportation, it was unclear how compliance was monitored.

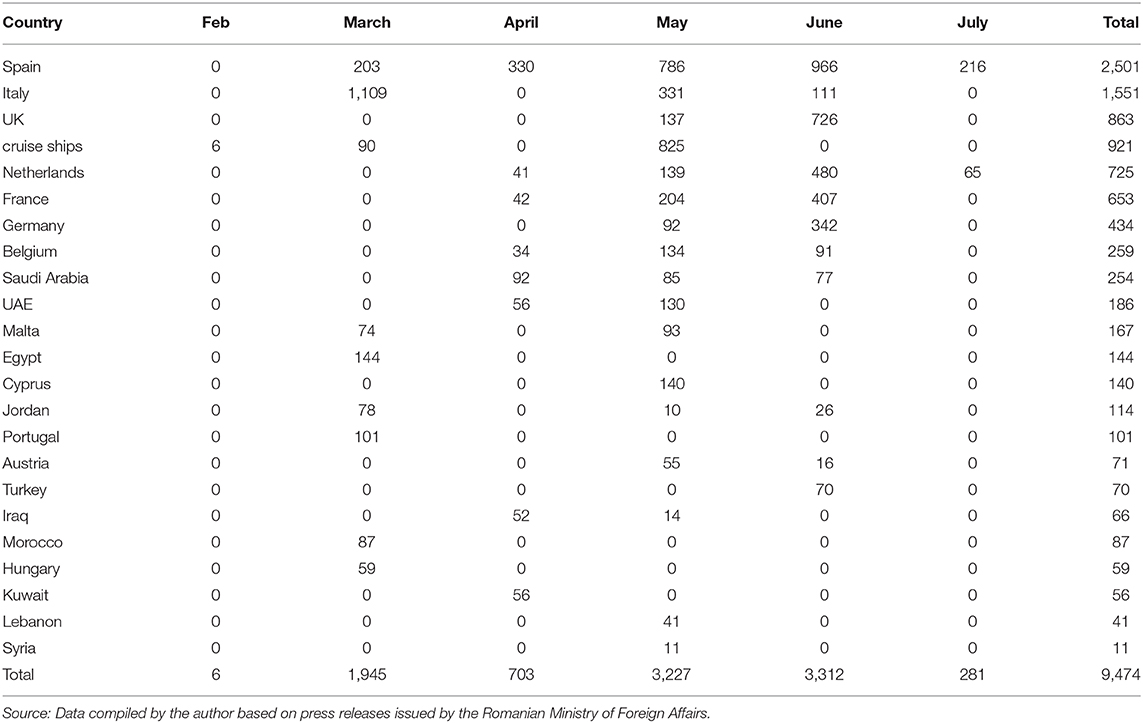

This disinterest in ensuring migrant workers' safety during travel and safe work conditions came at a high price for Romanian authorities when it came to the repatriation of Romanian nationals. The general policy on repatriation is that only Romanians who find themselves abroad temporarily are to be repatriated and only as a last resource. Data on repatriation compiled based on press releases issued by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs shows a big jump in numbers during the months of May and June for Germany, UK and the Netherlands (see Table 1). This is linked with the opening of air corridors from Romania to those countries for seasonal workers as media reports and the press releases confirm that among those repatriated were seasonal workers.

The EU advised relaxation of restrictions for critical workers ended up highlighting the poor working and living conditions of seasonal workers that place them at a higher risk of contracting the virus. Romanian seasonal workers are known to have contracted Covid-19 while at work in the Netherlands (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2020c), Germany (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2020d) and the UK (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2020e). Concerning Germany, a number of distressing incidents were reported where the much-needed Romanian seasonal workers were left on the street without any money or a return ticket by their employers because they had complained about work conditions (Kühnel, 2020). The Romanian Ombudsman officially raised questions with the relevant German authorities about the measures taken to safeguard the health and safety of migrant Romanian workers during travel from Romania to Germany and while there, and required an EU intervention (Avocatul Poporului, 2020). The Romanian authorities were eventually forced to take a stand and engage in bilateral talks with their German counterparts on how to ensure safety and appropriate working conditions for Romanian workers.

The treatment and lack of protection experienced by Romanian workers during the pandemic had visible effects at the EU level. The European Parliament (2020) adopted a Resolution on seasonal workers and the Commission published guidelines to highlight their vulnerability to precarious working and living conditions and issues relating to occupational safety and health conditions (European Commission, 2020e). Yet, the guidelines limit themselves to remind the Member States of their many obligations toward seasonal workers stemming from several EU legislative measures and stress the need to strengthen field inspections, enforce existing rules and better inform migrants of their rights. They do not explain why the existing legislative framework failed to provide protection, nor do they propose actions to remedy failures in protection brought to light by the Covid-19 crisis going beyond requesting the Member States to comply with existing obligations. As such, they are illustrative of a structural weakness in EU's mobility framework since reliance on national authorities' cooperation, preparedness and willingness to enforce existing rules has not always been sufficient to ensure the protection of the rights of mobile EU citizens, workers or otherwise (Valcke, 2019). The need to issue these guidelines highlights the failure to make migrant workers' vulnerability – which was known to both national and EU institutions – a key issue when designing policy solutions to keep the EU internal market going.

Conclusions

The examination of EU and national measures shows that in terms of mobility EU citizens remain a privileged group even in times of crisis. While the external border was in principle “closed” to TCNs, EU citizens, EU residents and their dependents were nonetheless exempted for the purpose of returning home. The right to be repatriated is normally associated with state nationality, but the crisis revealed its EU dimension since EU citizenship became another source of protection alongside state nationality. In relation to intra-EU mobility, EU institutions did not seek to challenge the imposition of national travel bans or the closure of internal borders. Rather, the priority was on safeguarding the EU's economy, parts of which are dependent on migrant EU workers. However, the EU's clear standpoint on the need to ensure the mobility of EU workers in critical occupations in light of the consequences of a complete standstill for the internal market, was not matched by convincing EU efforts to ensure that said workers are not abused, exploited or harmed.

The Romanian case offers food for thought on how to juggle economic interests, safety and healthcare concerns in a multilevel system of mobility governance. Faced with the possible return of its migration diaspora, the Romanian government sought to rely on border closure and quarantine/isolation to control and, maybe more importantly, dissuade mobility. The later aspect sits uncomfortably with the EU response to Covid-19 that emphasized EU nationals' right to return to the state of nationality as an important aspect of the governance of EU citizenship and of its mobility regime. Romania's approach to mobility during Covid-19 can be summed up as “discouraging return while encouraging emigration” and without safeguarding rights or ensuring protection. For Romanian nationals holding EU citizenship has clear advantages even in times of crisis since, as migration scholars and politicians alike know very well, borders can never be hermeneutically sealed off. Since legal privilege does not seem to automatically translate into protection for EU migrant workers, the argument put forward is that the Romanian case illustrates the limitations of an EU approach that emphasizes a primarily economic reading of EU mobility, that treats mobile EU citizens as economic actors but lacks a well-functioning framework to ensure protection. For EU institutions, it is a good reminder that enforceable mobility rights must be accompanied by enforceable workers' rights as a matter of normalcy.

Author's Note

Due to the measures taken by several EU states to deal with the effects of Covid-19, EU free movement has been severely disrupted as a result of the reestablishment of internal border controls, the introduction of restrictions to travel and even travel bans by some EU states. The (initial) lack of an EU response and the proliferation of national measures affecting free movement can be interpreted as the reassertion of national citizenship and the limited reach of EU citizenship. Likewise, the Commission's guidelines on dealing with Covid-19 and its insistence on the need to ensure mobility for essential workers as part of ensuring the survival of the internal market point toward the assertion of a primarily economic reading of mobility. This perspective on EU citizenship is discussed alongside policy measures aimed at facilitating and coordinating the repatriation of EU citizens stranded in or out of the EU due to the closure of internal borders and restrictions to international travel. Measures taken by Romania that sought to restrict the mobility of its citizens while simultaneously opening up airbridges so that Romanians could go work in other EU states illustrate some of the contradictions inherent in the EU response.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Agerpres (2020a). VIDEO Orban. Din 23 Februarie s-au Întors în Tară 1.279.000 de Cetăteni Români, 2020-05-04. Available online at: https://www.agerpres.ro/politica/2020/05/04/video-orban-din-23-februarie-s-au-intors-in-tara-1-279-000-de-cetateni-romani--498675 (accessed October 26, 2020).

Agerpres (2020b). Comisia de Anchetă/Oprea, Despre plecarea la Cules de Sparanghel a Românilor în Starea de Urgentă: A Fost un Vid Legislative. 2020-09-02. Available online at: https://www.agerpres.ro/viata-parlamentara/2020/09/02/comisia-de-ancheta-oprea-despre-plecarea-la-cules-de-sparanghel-a-romanilor-in-starea-de-urgenta-a-fost-un-vid-legislativ--566324 (accessed October 26, 2020).

Avocatul Poporului (2020). Solicitare Adresată Ministrului Federal al Muncii şi Afacerilor Sociale din Republica Federală Germania Privind Siguransa Sanitară a Muncitorilor Români Sezonieri, 22 Aprilie 2020. Available online at: https://avp.ro/index.php/2020/10/22/postare-4/ (accessed October 25, 2020).

Carrera, S., and Chun Luk, N. (2020). In the Name of COVID-19: An Assessment of the Schengen Internal Border Controls and Travel Restrictions in the EU. Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs, Directorate-General for Internal Policies, PE 659.506 - September 2020.

Decret al Preşedintelui României nr. 195/16 Martie 2020 privind instituirea stării de urgentă pe teritoriul României intrare în vigoare la data de 16 martie 2020 data publicării în MO nr. 212, partea I (Presidential Decree no 195 from 16 March concerning the state of emergency in Romania, Official Bulletin no. 212, 16 March 2020).

Dobreanu, C. (2020). Ce Perspective Sunt Pentru Românii Rămaşi fără Locuri de Muncă. Piaţa Muncii nu are în Acest Moment 300.000 de Posturi Disponibile'. Available online at: https://romania.europalibera.org/a/ce-perspective-sunt-pentru-romanii-ramasi-fara-locuri-de-munca-piata-muncii-nu-are-300-000-de-posturi-disponibile-/30597729.html (accessed August 13, 2020).

European Commission (2020a). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council, COVID-19: Temporary Restriction on Non-Essential Travel to the EU. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission (2020b). Communication From the Commission, COVID-19: Guidance on the Implementation of the Temporary Restriction on Non-essential Travel to the EU, on the Facilitation of Transit Arrangements for the Repatriation of EU Citizens, and on the Effects on visa Policy. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission (2020c). Communication from the Commission. Guidelines Concerning the Exercise of the Free Movement of Workers During COVID-19 Outbreak. 2020/C 102 I/03. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission (2020d). Communication from the Commission, COVID-19: Towards a Phased and Coordinated Approach for Restoring Freedom of Movement and Lifting Internal Border Controls. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission (2020e). Communication from the Commission, Guidelines on Seasonal Workers in the EU in the Context of the COVID-19 Outbreak. Brussel: European Commission.

European Parliament (2020). Bold Measures Needed to Protect Cross-border and Seasonal Workers in EU, MEPs Say. European Parliament. Available online at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20200615IPR81233/bold-measures-needed-to-protect-cross-border-and-seasonal-workers-meps-say (accessed October 26, 2020).

Eurostat (2020). EU Citizens Living in Another Member State - Statistical Overview. Eurostat. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statisticsexplained/index.php/EU_citizens_living_in_another_Member_State_-_statistical_overview#Key_messages (accessed November 12, 2020).

Fasani, F., and Mazza, J. (2020). Immigrant Key Workers: Their Contribution to Europe's COVID-19 Response. IZA Policy Paper No. 155. Available online at: http://ftp.iza.org/pp155.pdf (accessed August 13, 2020).

Kühnel, A. (2020). Sezonierii Români: Nu Toti Sunt Bineveniti în Germania Deutsche Welle. Available online at: https://p.dw.com/p/3cNpY (accessed August 10, 2020).

Mantu, S. (2020). “EU citizenship and EU territory. unsettling the national, embedding the supranational,” in EU Citizenship and Free Movement Rights. Taking Supranational Citizenship Seriously, eds S. Mantu, P. E. Minderhoud, and E. Guild (Leiden: Brill), 410–434. doi: 10.1163/9789004411784_019

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2020a). Press Releases Regarding the Situation of Romanian Citizens in Italy in the Context of Measures Adopted to Manage and Prevent the Spread of COVID-19 Infection. Press Release from 11.03.2020. Available online at: http://www.mae.ro/node/51878 (accessed August 14, 2020).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2020b). Approaches of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to Facilitate the Return to the Country of Romanian Freight Carriers. Press Release from 14.03.2020. Available online at: http://www.mae.ro/node/51944 (accessed August 14, 2020).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2020c). Press Release. Release from 21.05.2020. Available online at: http://www.mae.gov.ro/node/52578 (accessed November 26, 2020).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2020d). Press Releases. Press Release from 18.06.2020. Available online at: http://www.mae.ro/node/52863 (accessed August 14, 2020).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2020e). Press releases - 28 Other Romanian Citizens Tested Positive for COVID-19 Infection in the United Kingdom. Press Release from 21.07.2020. Available online at: http://www.mae.ro/node/53170 (accessed August 14, 2020).

Montaldo, S. (2020). The COVID-19 Emergency and the Reintroduction of Internal Border Controls in the Schengen Area: Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste. European Forum. 25 April 2020. pp 1-19.

Radio Europa Libera (2020b). Comisia Europeană: Scădere de 6% în România a Economiei. Şomajul va Ajunge la 6.5%. Radio Europa Libera. Available online at: https://romania.europalibera.org/a/comisia-europeanbrevea-scadere-de-6-în-romania-a-economiei-somajul-va-ajunge-la-6-5-/30596130.html (accessed August 11, 2020).

Radioa Europa Libera (2020a). Coronavirus în România. Violeta Alexandru: Şomajul Tehnic se Poate Prelungi Şi După 15 Mai. Radioa Europa Libera. Available online at: https://romania.europalibera.org/a/coronavirus-Înromânia-violeta-alexandru-.omajul-tehnic-se-poate-prelungi-.i-dupa-15-mai/30589311.html (accessed August 13, 2020).

Thym, D. (2020). Travel Bans in Europe. A legal appraisal (Part I and II). Odysseus Blog. Available online at: http://eumigrationlawblog.eu/travel-bans-in-europe-a-legal-appraisal-part-i/ (accessed October 26, 2020).

Udisteanu, A. (2020). Poveştile Românilor Întorşi Acasă. Available online at: https://recorder.ro/povestile-romanilor-intorsi-acasa/ (accessed August 13, 2020).

Keywords: mobility, repatriation, Romania, seasonal workers, critical occupations, air corridors

Citation: Mantu S (2020) EU Citizenship, Free Movement, and Covid-19 in Romania. Front. Hum. Dyn. 2:594987. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2020.594987

Received: 14 August 2020; Accepted: 16 November 2020;

Published: 09 December 2020.

Edited by:

Iris Goldner Lang, University of Zagreb, CroatiaReviewed by:

Mislav Mataija, European Commission Headquarters, BelgiumMartijn Van Den Brink, University of Oxford, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2020 Mantu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sandra Mantu, cy5tYW50dUBqdXIucnUubmw=

Sandra Mantu

Sandra Mantu