- Hubei Provincial Key Laboratory of Occurrence and Intervention of Rheumatic Diseases, Hubei Provincial Clinical Medical Research Center for Nephropathy, Minda Hospital of Hubei Minzu University, Hubei Minzu University, Enshi, China

Objective: Abdominal pregnancy is a special type of ectopic pregnancy that require careful evaluation for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management. Detailed clinical presentations, surgical procedures, and histopathological examinations of five cases of abdominal pregnancy are described. Relevant literature is also reviewed to contextualize the findings. These cases highlight the critical importance of precise diagnosis and timely intervention in the management of abdominal pregnancy. This study aims to provide an overview of the diagnosis, treatment, and management strategies of abdominal pregnancy through the presentation of five rare cases.

1 Introduction

Ectopic pregnancy occurs in 1–2% of pregnancies worldwide and represents a significant gynecological emergency (1). Abdominal pregnancy, a rare subtype constituting under 1% of ectopic case (2), involves embryonic implantation at extrauterine abdominal sites such as the omentum, major vessels, pouch of Douglas, and peritoneal surface (3–5). Due to nonspecific clinical presentations and diverse implantation locations, these cases frequently evade timely diagnosis. We present five surgically managed abdominal pregnancies at distinct anatomical sites, all demonstrating favorable postoperative outcomes.

2 Case presentation

2.1 Example 1

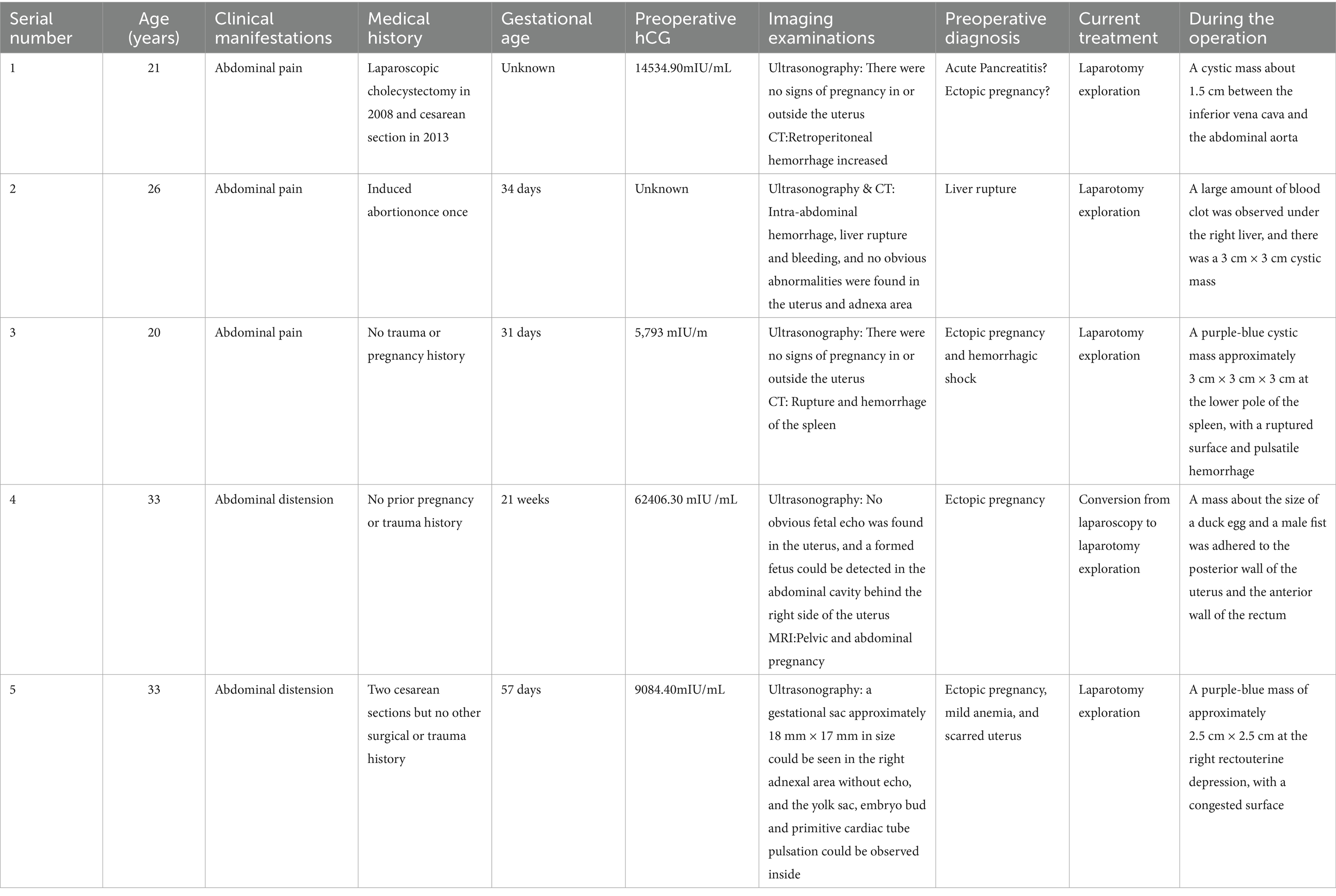

A 21-year-old female presented to the emergency department with a 1-day history of upper abdominal pain localized below the xiphoid process, which began after dinner and was accompanied by nausea and vomiting of gastric contents. CT imaging revealed acute pancreatitis with pancreatic head hemorrhage, pseudocyst formation, postoperative gallbladder changes, extrahepatic bile duct dilation, and bilateral kidney stones. Laboratory tests showed elevated hCG (14,534.90 mIU/mL) with normal blood amylase (22.0 U/L) and elevated urinary amylase (422.2 U/L). Ultrasound demonstrated normal uterine size with endometrial changes but no intra-or extrauterine pregnancy signs. Initial differential diagnoses included acute pancreatitis and ectopic pregnancy, prompting admission to hepatobiliary-pancreatic surgery. The patient had undergone laparoscopic cholecystectomy in 2008 and cesarean section in 2013. Despite 2 days of conservative management including fasting, gastrointestinal decompression, antibiotics, and pancreatic secretion suppression, follow-up CT showed progressive retroperitoneal hemorrhage of unclear origin. Emergency laparotomy revealed no uterine or adnexal abnormalities but identified a right retroperitoneal hematoma and a 1.5 cm cystic mass between the inferior vena cava and abdominal aorta containing white flocculent material. Histopathological examination confirmed ruptured retroperitoneal ectopic pregnancy. The patient achieved normalized hCG levels by postoperative day 21 and was discharged following full recovery (see Figures 1–3).

Figure 1. CT images of (A) Retroperitoneal pregnancy of the first patient, (B) hepatic pregnancy of the second patient, and (C) splenic pregnancy of the third patient.

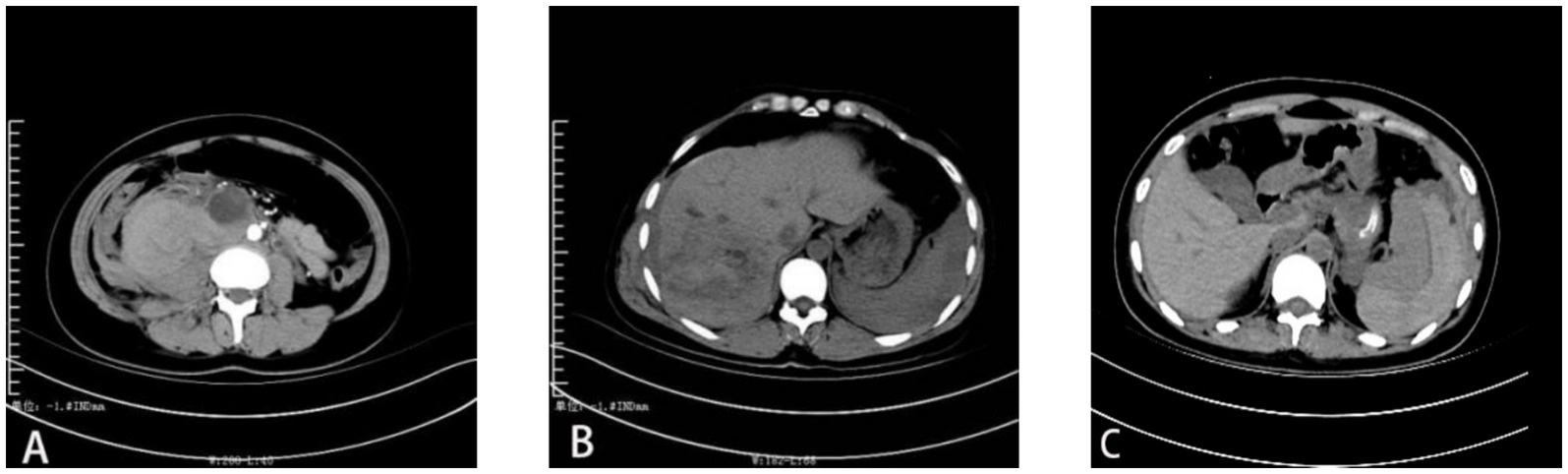

Figure 2. MRI images of Douglas pouch pregnancy of the fourth patient. The three pictures (A–C) show different sections of the lesion area of the fourth patient.

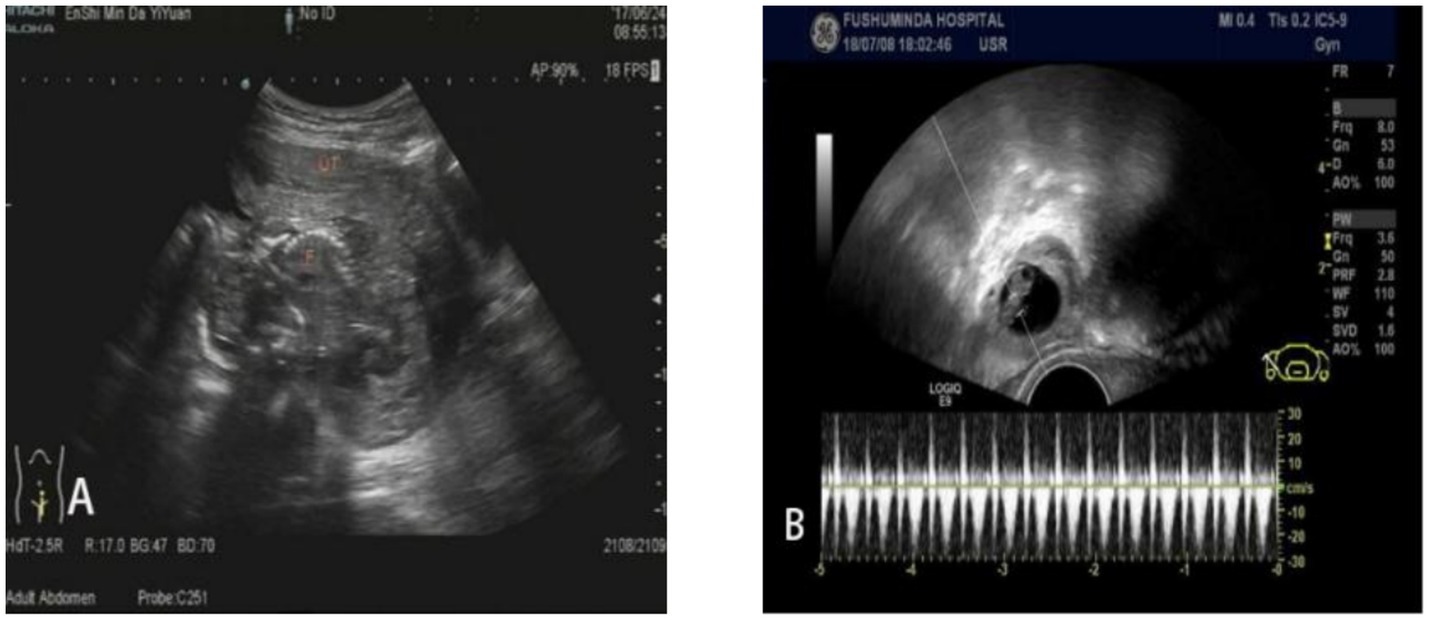

Figure 3. Ultrasonography images of Douglas pouch pregnancy of the fifth patient. The two pictures (A) and (B) show different sections of the lesion area of the fifth patient.

2.2 Example 2

A 26-year-old female presented to the emergency department with right upper abdominal pain persisting for 1 h following a traffic accident. She reported profuse sweating and localized pain at the injury site. Her medical history included one induced abortion, with her last menstrual period occurring 34 days prior. Physical examination revealed hypotension (90/60 mmHg), pallor, diffuse abdominal tenderness with rebound tenderness, and diminished bowel sounds. Abdominal ultrasonography and CT demonstrated intra-abdominal hemorrhage and hepatic rupture, while the uterus and adnexa appeared normal. Diagnostic paracentesis yielded non-coagulated blood, confirming the diagnosis of liver rupture and necessitating emergency laparotomy. Intraoperative findings included 2,000 mL of hemoperitoneum, substantial clotting beneath the right hepatic lobe, and a 3 cm × 3 cm cystic lesion exhibiting villous tissue and a gestational sac with active hemorrhage. Urine pregnancy testing and serum hCG quantification (5,271 mIU/mL) supported the provisional diagnosis of ruptured hepatic pregnancy. The lesion and adjacent hepatic tissue were excised for histopathological evaluation, which confirmed hemorrhagic rupture of ectopic hepatic pregnancy. The patient achieved biochemical resolution (normalized hCG) by postoperative day 18 and was subsequently discharged.

2.3 Example 3

A 20-year-old female presented to the emergency department with 1 day of generalized abdominal distension and pain, accompanied by cessation of flatus and bowel movements, followed by a syncopal episode. Initial evaluation suggested intestinal obstruction or intra-abdominal hemorrhage as potential causes of abdominal pain, prompting admission to general surgery. The patient reported no history of trauma or pregnancy, with her last menstrual period occurring 31 days prior. Physical examination revealed blood pressure of 100/60 mmHg, diffuse abdominal tenderness with guarding and rebound tenderness, diminished bowel sounds, and no palpable masses. A positive urine pregnancy test prompted further evaluation, revealing hemoglobin of 91 g/L and serum hCG of 5,793 U/L. Pelvic ultrasonography demonstrated fluid accumulation with normal uterine dimensions and no intrauterine or adnexal gestational findings. Diagnostic paracentesis yielded 4 mL of non-clotting blood, while abdominal CT identified splenic rupture with active hemorrhage. The patient underwent emergency laparotomy, which revealed significant hemoperitoneum with no uterine or adnexal pathology. Exploration identified active bleeding from a 3 cm3 purple-blue cystic lesion at the splenic lower pole, confirmed as the source of hemorrhage. Splenectomy was performed, with subsequent pathological examination of the resected specimen demonstrating chorionic villi and confirming splenic ectopic pregnancy with rupture. Postoperative hCG levels normalized within 10 days, and the patient was discharged following an uncomplicated recovery.

2.4 Example 4

A 33-year-old female admitted with a 21 + 3-week history of amenorrhea, persistent abdominal distension for over half a month, and right lower abdominal heaviness for 4 days. Her symptoms began with unexplained abdominal distension and constipation accompanied by flatulence, which persisted for 6 days despite fluid replacement and laxative treatment at a local clinic. The right lower abdominal discomfort occurred without vaginal bleeding or discharge, prompting referral to our hospital. Ultrasound examination revealed no intrauterine fetal echo but detected a formed fetus with cardiac activity and movement in the abdominal cavity posterior to the right uterus. The patient had no prior pregnancy or trauma history before her last menstrual period 21 + 3 weeks earlier. Physical examination showed a blood pressure of 106/67 mmHg, pallor, lower abdominal fullness, and right lower abdominal tenderness, with the uterine fundus at umbilical level and the fetus displaced toward the right lower quadrant. Laboratory tests indicated severe anemia (hemoglobin 63 g/L) and elevated hCG (62,406.30 mIU/mL). MRI confirmed abdominal pregnancy with minimal uterine and pelvic effusion and a sacral canal cyst. Diagnosed with abdominal pregnancy and anemia, she received leukocyte-depleted red blood cell transfusion and underwent exploratory laparotomy. Intraoperative findings included 500 mL of non-coagulated blood and a duck egg-sized mass adherent to the uterine posterior wall and rectal fascia. The amniotic sac contained a 10 cm fetus, and the placenta was attached to the right broad ligament posterior leaf. Both ovaries appeared normal, though the fallopian tubes showed irregular thickening with fimbrial adhesions to the ipsilateral ovaries. The final diagnosis was Douglas pouch pregnancy. Postoperative hCG normalized by day 13, and the patient was discharged following an uncomplicated recovery.

2.5 Example 5

A 33-year-old female admitted to a local hospital with a 41-day history of amenorrhea, 8 days of paroxysmal lower abdominal distension, and 1 day of symptom exacerbation. Serum hCG levels were elevated, and ultrasonography revealed abnormal echoes in the right adnexal region with pelvic effusion. A posterior vaginal fornix puncture yielded 4 mL of dark red, non-clotted blood, prompting emergency laparoscopic exploration. Intraoperative findings included slight thickening and bluish-purple discoloration of the right fallopian tube ampulla without rupture or visible villous tissue. Postoperative treatment with methotrexate (MTX), mifepristone, and traditional Chinese medicine failed to control rising hCG levels, necessitating transfer to our institution. Outpatient ultrasonography demonstrated an 18 × 17 mm anechoic gestational sac in the right adnexa containing a yolk sac, embryonic bud, and primitive cardiac pulsation, leading to admission for suspected ectopic pregnancy. The patient had two prior cesarean deliveries but no other surgical or trauma history, with her last menstrual period occurring 57 days before presentation. Physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 91/62 mmHg, fresh laparoscopic scars with intact sutures in the lower abdomen, and no tenderness or rebound tenderness. Serum hCG measured 9084.40 mIU/mL, supporting diagnoses of ectopic pregnancy, mild anemia, and scarred uterus. Repeat laparoscopic exploration showed normal uterine and left adnexal anatomy, while the right fallopian tube ampulla remained thickened and bluish-purple without rupture or active bleeding. A 25 mm× 25 mm purple-blue mass with surface congestion was identified in the right rectouterine pouch, prompting conversion to laparotomy for embryo removal. Gross examination revealed villi and decidual-like tissue, confirmed by pathological analysis showing trophoblasts, blood clots, and chorionic villi. Despite suboptimal hCG decline, the patient requested discharge on postoperative day 5 after acknowledging the risks (see Table 1).

3 Discussion

Risk factors for abdominal pregnancy encompass congenital reproductive system malformations, prior ectopic pregnancy, previous fallopian tube surgery, uterine rupture, endometriosis, and pelvic inflammatory disease (6, 7).

In early abdominal pregnancy with an intact gestational sac, symptoms often remain nonspecific. Clinical detection typically occurs incidentally during evaluation for intra-abdominal hemorrhage. Previous studies describe presentations including lower abdominal pain, amenorrhea, and vaginal bleeding (8), with some cases exhibiting nausea and vomiting. Without prompt intervention, this condition may progress to life-threatening hemorrhage, demonstrating approximately eightfold higher mortality than tubal pregnancy (6). Clinicians evaluating abdominal pain patients, particularly those with relevant risk factors, should maintain high suspicion for ectopic pregnancy.

Diagnosing abdominal pregnancy typically requires imaging and pathological examination. Ultrasonography detects the presence of yolk sacs, embryos, and vascular pulsation, while CT and MRI intraoperatively localize the implantation site and assess spatial relationships between the gestational sac and adjacent structure (9, 10). Additionally, because of MRI clearly demonstrates the endometrium-myometrium border and the relationship between the endometrial cavity and the gestational sac (11). It can distinguish abdominal pregnancy from other types of ectopic pregnancies. Gerli et al. (12) established ultrasound diagnostic criteria: (a) absence of intrauterine gestational sac, (b) no definitive tubal dilation or complex adnexal mass, (c) peritoneal separation or intestinal encasement of the gestational sac, and (d) sac mobility with fluctuance upon transvaginal probe pressure. When ectopic pregnancy is suspected but pelvic ultrasound proves inconclusive, the examination should extend to abdominal scanning to identify potential hemorrhage sites or extrauterine implantation. In emergent cases requiring laparotomy or laparoscopy, pathological confirmation of chorionic villi provides definitive diagnosis. The principal diagnostic challenge involves promptly considering abdominal pregnancy in acute abdominal presentations with elevated hCG but no evident intrauterine or tubal implantation. Such cases warrant expanded imaging evaluation of rare sites including retroperitoneum, spleen, and liver. CT or MRI precisely maps the gestational sac location preoperatively; when uncertainty persists, surgical exploration with intraoperative ultrasound guidance optimizes localization. Inadequate assessment risks inappropriate management with consequent life-threatening complications and increased healthcare costs.

The management of abdominal pregnancy involves both pharmacological and surgical interventions. Given the invasive nature of placental tissue and the anatomical complexity of gestational sac localization near vascular structures, multidisciplinary consultation is critical for determining an appropriate treatment strategy. Methotrexate (MTX) remains the primary pharmacological option, acting through gestational trophoblast cells proliferation inhibition, villous destruction, and subsequent embryonic tissue necrosis and absorption. MTX may be administered via ultrasound-guided or laparoscopic intragestational sac injection or as systemic therapy perioperatively (13). Huang et al. (14) documented successful CT-guided local MTX injection in two cases, though drug therapy is contraindicated in patients with unstable gestational sacs, gestational age exceeding 11 weeks, significant hemorrhage, or MTX intolerance (15). Most patients failing conservative management ultimately require surgical intervention, as optimal drug regimens remain undefined. Surgical approaches typically involve laparotomy, occasionally requiring collaborative efforts between surgical and radiological teams (3, 16) to identify bleeding sites and facilitate gestational sac removal. Laparoscopic techniques, while offering advantages such as minimal invasiveness and faster recovery (17), demand substantial surgical expertise in retroperitoneal anatomy and may necessitate conversion to laparotomy in cases of undetected gestational sacs or major vascular injury. However, laparoscopic surgery is safer and leads to greater patient satisfaction compared to laparotomy (18). Recent advancements in laparoscopic technology have established it as the preferred exploratory method. Notably, Le et al. (19) reported successful expectant management, underscoring the importance of individualized treatment strategies incorporating gestational parameters, sac characteristics, adjacent organ involvement, clinical presentation, hCG levels, fetal viability, and patient preferences. Early diagnosis and intervention significantly reduce maternal morbidity and improve clinical outcomes.

All five patients presented with abdominal pain but were ultimately diagnosed with abdominal pregnancy during surgical exploration. Surgical intervention was necessary to promptly control hemorrhage and prevent complications. Laparotomy not only confirmed the diagnosis but also facilitated subsequent treatment planning. Postoperative hCG monitoring proved essential for assessing treatment efficacy and determining the need for chemotherapy.

4 Conclusion

The clinical implications of this case are noteworthy. Physicians evaluating patients with abdominal pain and abnormal hCG levels should maintain a high index of suspicion for abdominal pregnancy, particularly when supported by relevant medical history. Imaging modalities such as CT and ultrasonography play a pivotal role in establishing the diagnosis. Postoperative surveillance remains critical for patient recovery and complication prevention, where early intervention and surgical expertise significantly influence outcomes. Further investigation into optimized diagnostic approaches and therapeutic protocols for abdominal pregnancy will enhance clinical management strategies.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Minda Hospital of Hubei Minzu University, Hubei, China. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual (s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

Author contributions

WY: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. JH: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. YW: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. HX: Resources, Writing – review & editing. DZ: Supervision, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by a grant from the Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 2023AFD070) and Enshi Prefecture Science and Technology Plan Project (No. D20220024).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Chang, J, Elam-Evans, LD, Berg, CJ, Herndon, J, Flowers, L, Seed, KA, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality surveillance–United States, 1991–1999. MMWR Surveill Summ. (2003) 52:1–8.

2. Rohilla, M, Joshi, B, Jain, V, Neetimala,, and Gainder, S. Advanced abdominal pregnancy: a search for consensus. Review of literature along with case report. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2018) 298:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00404-018-4743-3

3. Chen, Y, Peng, P, Li, C, Teng, L, Liu, X, Liu, J, et al. Abdominal pregnancy: a case report and review of 17 cases. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2023) 307:263–74. doi: 10.1007/s00404-022-06570-9

4. Yang, M, Cidan, L, and Zhang, D. Retroperitoneal ectopic pregnancy: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2017) 17:358. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1542-y

5. Abdullah, L, Alsulaiman, SS, Hassan, M, Ibrahim, HS, Alshamali, N, and Nizami, S. Abdominal pregnancy: a case report. Ann Med Surg. (2023) 85:302–5. doi: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000000245

6. Sato, H, Mizuno, Y, Matsuzaka, S, Horiuchi, T, Kanbayashi, S, Masuda, M, et al. Abdominal pregnancy implanted on surface of pedunculated subserosal uterine leiomyoma: a case report. Case Rep Womens Health. (2019) 24:e00149. doi: 10.1016/j.crwh.2019.e00149

7. Yoder, N, Tal, R, and Martin, JR. Abdominal ectopic pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and single embryo transfer: a case report and systematic review. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. (2016) 14:69. doi: 10.1186/s12958-016-0201-x

8. Varma, R, Mascarenhas, L, and James, D. Successful outcome of advanced abdominal pregnancy with exclusive omental insertion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. (2003) 21:192–4. doi: 10.1002/uog.25

9. Si, MJ, Gui, S, Fan, Q, Han, HX, Zhao, QQ, Li, ZX, et al. Role of MRI in the early diagnosis of tubal ectopic pregnancy. Eur Radiol. (2016) 26:1971–80. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3987-6

10. Teng, HC, Kumar, G, and Ramli, NM. A viable secondary intra-abdominal pregnancy resulting from rupture of uterine scar: role of MRI. Br J Radiol. (2007) 80:e134–6. doi: 10.1259/bjr/67136731

11. Ntafam, CN, Sanusi-Musa, I, and Harris, RD. Intramural ectopic pregnancy: an individual patient data systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X. (2024) 21:100272. doi: 10.1016/j.eurox.2023.100272

12. Gerli, S, Rossetti, D, Baiocchi, G, Clerici, G, Unfer, V, and Renzo, GCD. Early ultrasonographic diagnosis and laparoscopic treatment of abdominal pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (2004) 113:103–5. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(03)00366-X

13. Python, JL, Wakefield, BW, Kondo, KL, Bang, TJ, Stamm, ER, and Hurt, KJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous Management of Splenic Ectopic Pregnancy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. (2016) 23:997–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2016.05.004

14. Huang, X, Zhong, R, Tan, X, Zeng, L, Jiang, K, Mei, S, et al. Conservative management of retroperitoneal ectopic pregnancy by computed tomographic-guided methotrexate injection in the gestational sac: 2 case reports and literature review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. (2019) 26:1187–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.12.016

15. Ansong, E, Illahi, GS, Shen, L, and Wu, X. Analyzing the clinical significance of postoperative methotrexate in the management of early abdominal pregnancy: analysis of 10 cases. Ginekol Pol. (2019) 90:438–43. doi: 10.5603/GP.2019.0078

16. Le, MT, Huynh, MH, Cao, CH, Hoang, YM, Le, KC, and Dang, VQ. Retroperitoneal ectopic pregnancy after in vitro fertilization/embryo transfer in patient with previous bilateral salpingectomy: a case report. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2020) 150:418–9. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13136

17. Hajji, A, Toumi, D, Laakom, O, Cherif, O, and Faleh, R. Early primary abdominal pregnancy: diagnosis and management. A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. (2020) 73:303–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.07.048

18. Di Lorenzo, G, Romano, F, Mirenda, G, Cracco, F, Buonomo, F, Stabile, G, et al. "Nerve-sparing" laparoscopic treatment of parametrial ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. (2021) 116:1197–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.05.106

Keywords: abdominal pregnancy, therapy, diagnosis, hCG, ultrasonography

Citation: Yang W, Huang J, Wang Y, Xiang H and Zhu D (2025) Abdominal pregnancy: a report of five cases and literature review. Front. Med. 12:1638015. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1638015

Edited by:

Guglielmo Stabile, Institute for Maternal and Child Health Burlo Garofolo (IRCCS), ItalyReviewed by:

Stefania Carlucci, Institute for Maternal and Child Health Burlo Garofolo (IRCCS), ItalyFrancesco Cracco, Sacro Cuore Don Calabria Hospital (IRCCS), Italy

Copyright © 2025 Yang, Huang, Wang, Xiang and Zhu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daiyu Zhu, MjAwNTA1MkBoYm16dS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Wenxuan Yang

Wenxuan Yang Jianfeng Huang†

Jianfeng Huang† Yuqing Wang

Yuqing Wang