Abstract

The convergence of IoT sensing, edge computing, and machine learning is revolutionizing precision livestock farming. Yet bioacoustic data streams remain underexploited due to computational-complexity and ecological-validity challenges. We present one of the most comprehensive bovine vocalization datasets to date-569 expertly curated clips spanning 48 behavioral classes, recorded across three commercial dairy farms using multi-microphone arrays and expanded to 2,900 samples through domain-informed data augmentation. This FAIR-compliant resource addresses key Big Data challenges: volume (90 h of raw recordings, 65.6 GB), variety (multi-farm, multi-zone acoustic environments), velocity (real-time processing requirements), and veracity (noise-robust feature-extraction pipelines). A modular data-processing workflow combines denoising implemented both in iZotope RX 11 for quality control and an equivalent open-source Python pipeline using noisereduce, multi-modal synchronization (audio-video alignment), and standardized feature engineering (24 acoustic descriptors via Praat, librosa, and openSMILE) to enable scalable welfare monitoring. Preliminary machine-learning benchmarks reveal distinct class-wise acoustic signatures across estrus detection, distress classification, and maternal-communication recognition. The dataset's ecological realism-embracing authentic barn acoustics rather than controlled conditions-ensures deployment-ready model development. This work establishes the foundation for animal-centered AI, where bioacoustic streams enable continuous, non-invasive welfare assessment at industrial scale. By releasing a Zenodo-hosted, FAIR-compliant dataset (restricted access) and an open-source preprocessing pipeline on GitHub, together with comprehensive metadata schemas, we advance reproducible research at the intersection of Big Data analytics, sustainable agriculture, and precision livestock management. The framework directly supports UN SDG 9, demonstrating how data science can transform traditional farming into intelligent, welfare-optimized production systems capable of meeting global food demands while maintaining ethical animal-care standards.

1 Introduction

The exponential growth of agricultural data—projected to surpass 5.1 exabytes by 2025—positions precision livestock farming at the intersection of IoT sensing, edge computing, and machine learning analytics (Scoop Market Research, 2025; Precision Business Insights, 2024). Within this evolving digital ecosystem, bioacoustic data streams stand out as a particularly complex and information-rich modality. These continuous, high-frequency temporal signals demand specialized preprocessing pipelines, robust feature engineering, and scalable analysis frameworks to unlock actionable insights. Building on this context, the rapid growth of digital agriculture has further highlighted the transformative potential of big data and machine learning in reshaping livestock farming into a more sustainable, welfare-centered, and efficient sector. Among various sensing modalities, bioacoustics has emerged as a powerful yet underutilized channel of information, offering non-invasive insights into animal health, behavior, and emotional state. In particular, cattle vocalizations carry rich indicators of social interaction, estrus, maternal care, hunger, stress, and pain, positioning them as promising biomarkers for welfare monitoring and automated farm management systems. Harnessing these signals, however, requires curated datasets that faithfully capture the acoustic, behavioral, and environmental realities of commercial farming contexts.

The lack of large, annotated datasets remains one of the most significant bottlenecks in bovine bioacoustics research (Kate and Neethirajan, 2025). Traditional acoustic analysis methods involving manual spectrogram generation and feature extraction are informative but not scalable to the data volumes required for robust AI training, underscoring the critical need for comprehensive, FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable)-compliant datasets that capture ecological validity while supporting big data analytics. Importantly, FAIR principles do not require that all data be fully open; rather, they emphasize transparent, machine-readable access conditions that can accommodate justified restrictions such as farm confidentiality (Martorana et al., 2022; Karakoltzidis et al., 2024).

Despite increasing interest, existing bovine vocalization corpora remain limited in scale, scope, and reproducibility. Most prior datasets have been collected from small cohorts under controlled or homogeneous conditions, focusing primarily on a narrow set of call types such as estrus calls or distress vocalizations. For instance, the “BovineTalk” dataset reported over a thousand vocalizations but from only 20 cows in isolation, thereby excluding environmental noise and behavioral diversity. Similarly, physiological studies linking calls to cortisol or estrus relied on restricted conditions, limiting generalizability to commercial barns. These constraints hinder the development of machine learning models that can generalize across diverse farm environments, rare behaviors, and variable acoustic conditions. Furthermore, multimodal integration of audio with video or ethological annotations is rarely implemented, restricting opportunities to contextualize vocalizations with corresponding behaviors.

In addition to limited behavioral coverage, many existing datasets deliberately exclude background noise to ensure clean acoustic signals. While this simplifies analysis, it reduces ecological validity, as commercial dairy barns are acoustically complex environments containing mechanical noise, overlapping calls, and human activity. Models trained on clean laboratory recordings often fail when deployed in real-world farms, where vocal signals are embedded within heterogeneous soundscapes. There is therefore an urgent need for datasets that reflect the acoustic reality of farming environments, balancing signal clarity with ecological authenticity.

To address these gaps, we introduce a novel bovine vocalization dataset that combines scale, behavioral diversity, and ecological realism with rigorous annotation and metadata standards. The corpus comprises 569 curated clips spanning 48 behavioral classes, recorded across three commercial dairy farms in Atlantic Canada using a multi-microphone, multimodal design. By capturing audio simultaneously from multiple barn zones—feeding alleys, drinking troughs, milking parlors, and resting pens–and pairing these recordings with video observations and detailed ethological notes, the dataset provides a comprehensive representation of the acoustic and behavioral ecology of dairy cattle. Unlike earlier collections that prioritized controlled conditions, this resource embraces the complexity of barn environments, including background machinery, overlapping calls, and routine human activity, thereby enhancing its value for developing robust, field-ready analytical models.

A key contribution of this dataset lies in its ethology-driven annotation scheme, which organizes vocalizations into nine main categories and 48 sub-types covering maternal, social, reproductive, feeding, drinking, handling, distress, environmental, and non-vocal events. Each clip is annotated with behavioral context, emotional valence, and confidence scores, enabling analyses that extend beyond acoustics to questions of welfare, motivation, and social interaction. This structure aligns with contemporary animal welfare frameworks that emphasize emotional valence and arousal, while also providing machine-readable descriptors suitable for computational modeling. Equally important is the dataset's adherence to FAIR principles. Metadata tables document recording context, equipment, clip features, and preprocessing parameters in a transparent and reproducible manner. The inclusion of acoustic features extracted with standardized pipelines (Praat, librosa, openSMILE) ensures interoperability with other livestock bioacoustic resources and facilitates downstream applications ranging from supervised classification to exploratory behavioral analysis.

Together, these elements establish this corpus as the most comprehensive and ecologically valid dataset of bovine vocalizations to date. It provides not only a foundation for advancing machine learning approaches to livestock sound analysis, but also a benchmark resource for researchers in animal behavior, welfare science, and precision livestock management. To support reproducible reuse, the curated clips and associated metadata are deposited under restricted access in a Zenodo repository with a persistent DOI, while the full preprocessing and feature extraction pipeline is released as open-source code on GitHub.

In addition to its methodological and scientific contributions, this dataset holds direct significance for the emerging field of precision livestock farming. By enabling the detection and interpretation of vocal cues linked to health, reproduction, and welfare, it opens pathways for non-invasive monitoring systems that can assist farmers in real time. Early detection of estrus, distress, or discomfort through automated vocal analysis could enhance reproductive management, reduce disease risks, and improve overall herd wellbeing. Beyond cattle, the dataset also contributes to the broader movement in animal-centered AI, where bioacoustic data are increasingly leveraged to give “digital voices” to non-human species. Recent work on AI-assisted behavioral monitoring in sheep and goats, for example, has demonstrated how vocal and behavioral traits can be mapped to welfare-relevant states using machine learning (Emsen et al., 2025). Our bovine vocalization dataset extends this line of work to dairy cattle, providing a complementary resource within a growing ecosystem of AI tools that integrate vocalization analysis with computer vision and wearable sensor data across ruminant species.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the novelty of the dataset, situating it in relation to previous studies. Section 3 describes the data collection protocols, including recording sites, equipment, and multimodal capture methods. Section 4 outlines the preprocessing pipeline, covering noise profiling, filtering, denoising, segmentation, and annotation. Section 5 details dataset creation, including feature extraction, biological interpretation, metadata design, and preliminary analyses. Finally, Section 6 presents the discussion of significance and limitations, and Section 7 concludes the paper highlighting its potential as a benchmark for both animal welfare science and big data applications in agriculture. Building on these motivations, the next section outlines the novelty of our dataset in relation to existing bovine vocalization corpora.

2 Dataset novelty

2.1 Scale and diversity of recordings

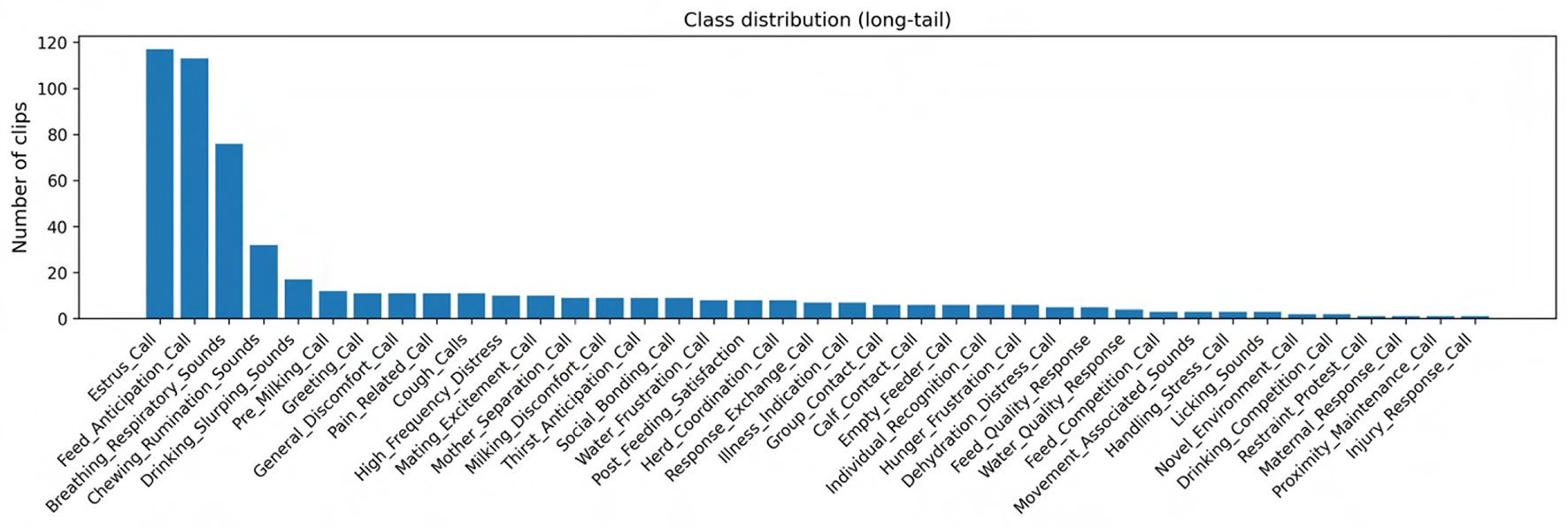

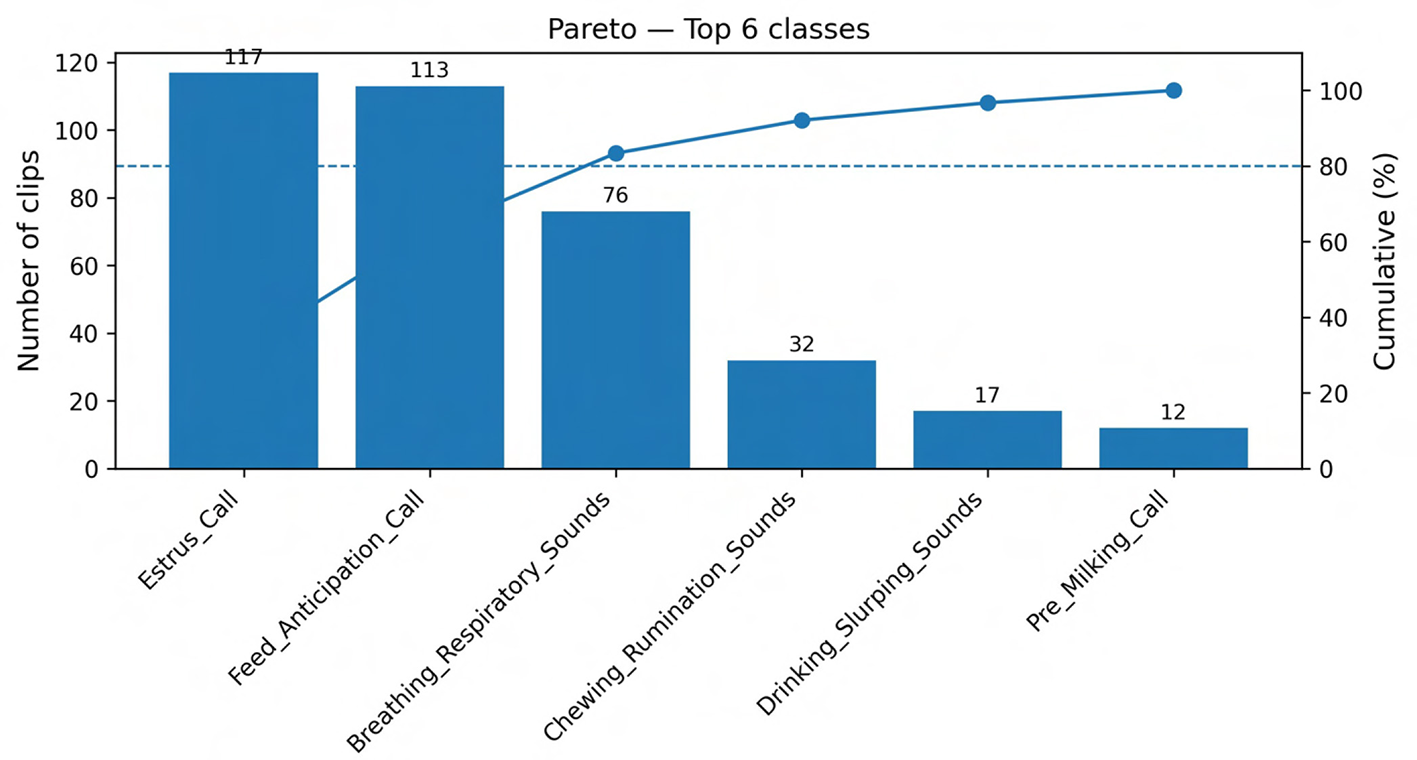

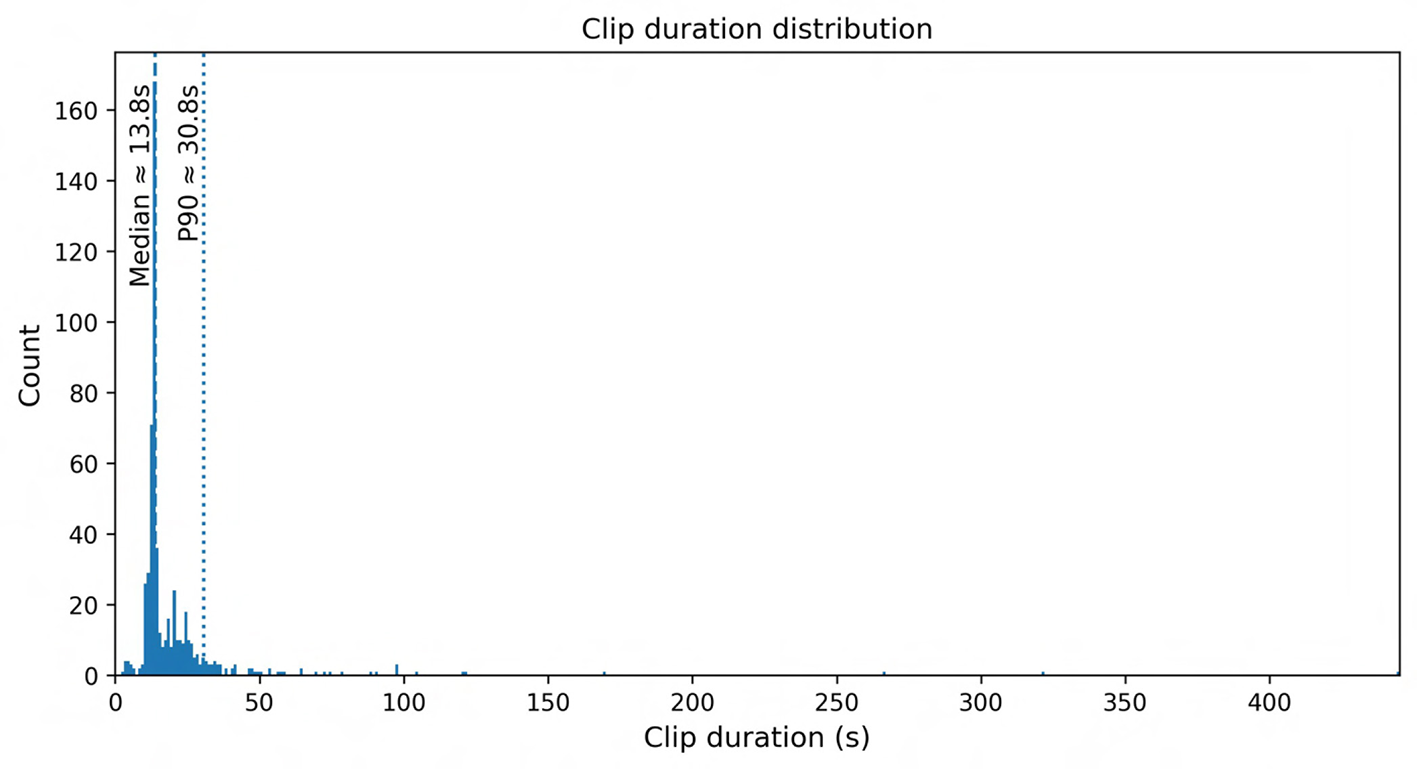

This work presents one of the most comprehensive bovine vocalization datasets to date. The corpus comprises 569 clips covering 48 behavioral labels (classes) and has a mean clip duration of ~ 21 s (median ~ 13.8 s; range 2.8–445 s). Analysis shows a long tailed distribution: the largest classes, Estrus_Call (117 clips) and Feed_Anticipation_Call (113 clips), account for 40% of the data, whereas many categories contain fewer than ten samples, reflecting the rare and spontaneous nature of some behaviors. Clip durations are short enough to facilitate fine grained acoustic analysis yet long enough to capture the full vocalization plus context. A detailed breakdown of the dataset composition is provided in Supplementary Table S1, which reports clip counts and total duration by main category, subcategory, farm, barn zone, and microphone. The underlying metadata and acoustic feature tables are distributed with the Zenodo record described in the Data Availability Statement, enabling other researchers to subset the corpus by behavioral class, recording context, or equipment configuration for targeted analyses.

Most published bovine call datasets are smaller both in scale and scope. For example, the “BovineTalk” study isolated 20 multiparous cows for 240 min post milking and obtained 1,144 vocalizations (952 high frequency and 192 low frequency) (Gavojdian et al., 2024); the authors noted that calls were recorded under identical conditions and excluded noise. Another study analyzed 12 Holstein heifers and reported that vocalization rate peaked one interval before estrus climax and was higher during natural than induced estrus (Röttgen et al., 2018). (Yoshihara and Oya 2021) recorded 290 calls from 32 cows across four physiological states (feed anticipation, estrus, communication and parturition) and showed that call intensity, pitch and formant values reflected changes in salivary cortisol. (Katz 2020) captured 333 high frequency calls from 13 heifers and demonstrated that cows maintain individual vocal cues across contexts. Compared with these studies, our dataset contains both high and low frequency calls across positive and negative contexts, includes a richer set of behavioral classes (maternal, social, estrus, feeding, drinking, handling, distress, environmental and non vocal), and encompasses multiple farms and barn zones. This breadth enables analyses of behavioral diversity and cross context variation not previously possible.

Beyond scale and diversity, novelty also arises from the recording design, which is detailed in the next subsection.

2.2 Multi-microphone setup and multimodal synchronization

Recordings were collected from three commercial Holstein-Friesian dairy farms in Sussex County, New Brunswick, Canada over three consecutive days (5–7 May 2025), with one farm recorded per day between 9:00 am and 6:00 pm (Table 1). Across these sites, 65 raw audio files were obtained, representing a total of ~90 h of recordings (65.57 GB; mean file duration ~ 1 h 24 m, mean file size ~1.0 GB).

Table 1

| Farm ID | Herd size (Holstein/others) | Barn zones monitored | Microphones | Recorders | Raw files (n) | Total duration (h) | Total size (GB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farm 1 | 57 Holstein | Feeding, drinking, milking, resting | Sennheiser MKH 416; RØDE NTG-2 | Zoom F6; Zoom H4n Pro | 21 | ~30 h | ~21.5 |

| Farm 2 | 207 Holstein/Jersey mix | Feeding, drinking, resting, milking | Sennheiser MKH 416; Zoom H4n Pro | Zoom F6; Zoom H4n Pro | 21 | ~29 h | ~22.0 |

| Farm 3 | 160 Holstein | Feeding, resting, drinking | Wildlife bioacoustics recorder; RØDE NTG-2 | Zoom F6; Zoom H4n Pro | 23 | ~31 h | ~22.1 |

| Total | 424 cows | All zones (feeding, drinking, milking, resting) | Multiple (MKH 416, NTG-2, Bioacoustics) | Zoom F6; H4n Pro; | 65 | 90 h 2 m | 65.6 |

Overview of recording sites and microphone-recorder setup.

Bold values indicate the total of all rows in the table.

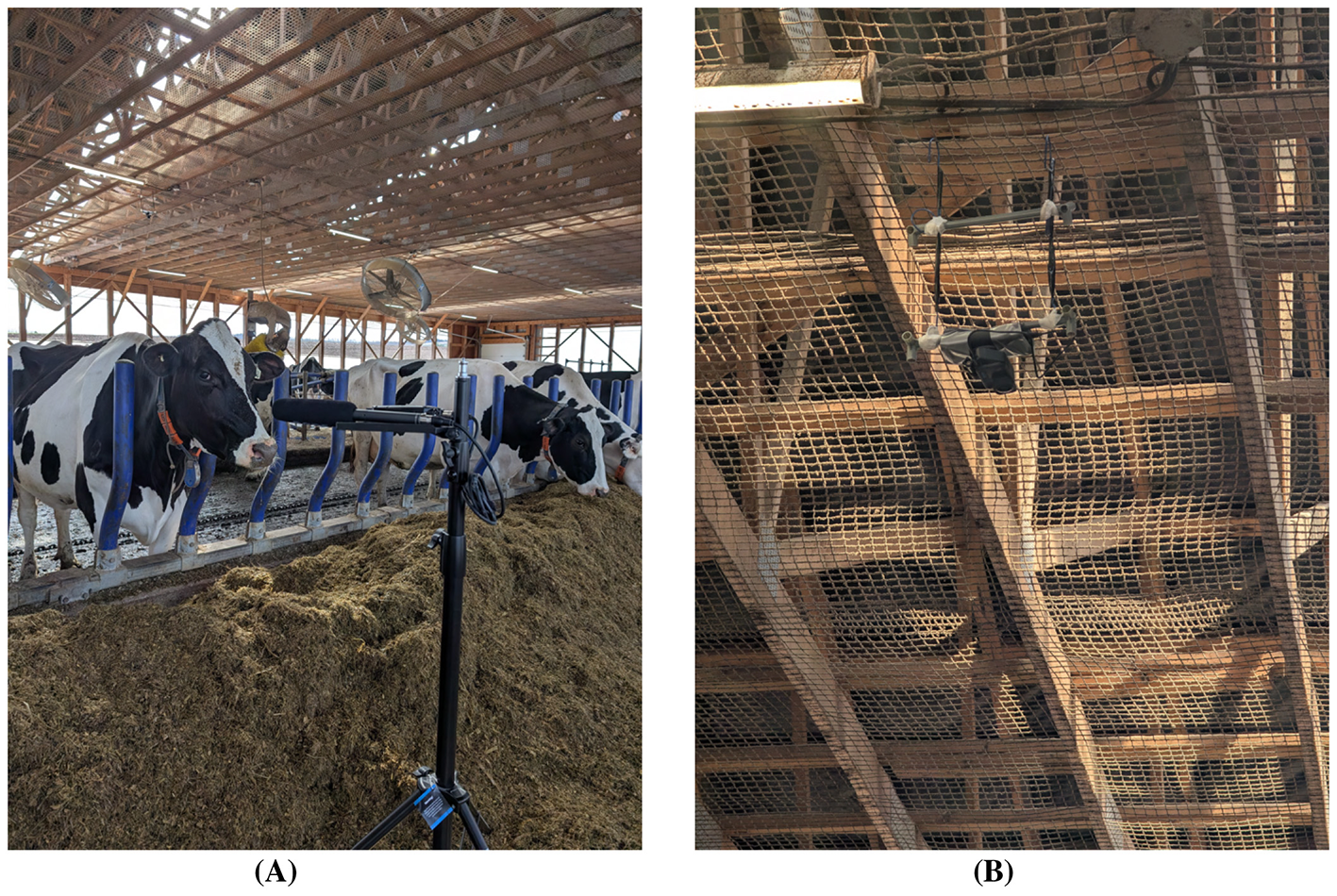

The dataset captures four primary behavioral contexts—drinking, feeding, milking, and resting—within commercial barn environments. These settings included natural background sounds such as clanging metal gates, fans, tractors idling, overlapping vocalizations, and other routine noises. A representative example of the feeding-zone deployment is shown in Figure 1, where a shotgun microphone is co-located with a ceiling-mounted action camera to achieve synchronized audio-video capture of cow behavior at the feed trough. By integrating multiple farms and barn zones, the corpus reflects the true acoustic diversity of commercial dairy environments rather than controlled or laboratory conditions.

Figure 1

Multimicrophone and video setup used for synchronized multimodal recording in dairy barns. (A) Directional RØDE NTG-2 shotgun microphone connected to a Zoom H4n Pro portable recorder, deployed in the feeding section of farm. The setup was mounted on a stable tripod oriented toward the feed trough to capture high-fidelity vocalizations while rejecting off-axis barn noise. (B) Ceiling-mounted GoPro action camera positioned directly above the same zone in same farm to capture continuous 4K video of feeding behavior. The spatial alignment of microphone and camera ensured accurate cross-referencing between audio and behavioral context during manual annotation and ethological validation. (A) Feeding zone microphone setup. (B) Feeding zone camera setup.

The novelty of this corpus lies in its multimicrophone, multi-sensor design. Unlike earlier bovine vocalization studies that relied on a single microphone or controlled settings, the present dataset integrates recordings from multiple farms, barn zones, and equipment types. Directional shotgun microphones (Sennheiser MKH 416, RØDE NTG-2) provided close-range, high signal-to-noise vocalizations, while portable recorders (Zoom H4n Pro, Zoom F6) and an autonomous Wildlife Bioacoustics logger captured longer-duration ambient soundscapes.

This design ensured that both focal vocal events (e.g., estrus calls, feeding anticipation) and background acoustic context (e.g., overlapping moos, barn machinery, human activity) were represented. The inclusion of video recordings from multiple GoPro cameras added a complementary visual dimension, enabling cross-referencing of acoustic events with behavioral context. Together, this multimodal, multi-sensor strategy produces a holistic, reproducible dataset that captures the acoustic reality of commercial dairy environments at unprecedented scale and resolution. This design also supports downstream statistical analyses that explicitly account for farm, barn zone, and microphone as potential sources of variance (Section 5.6), enabling users to quantify how much of the acoustic variability arises from environmental and equipment factors vs. behavioral class.

2.3 Environmental noise profiling

Dairy barns are acoustically challenging, with persistent machinery noise (milking robots, feeders, tractors), metal gate clanging, hoof impacts, people talking, urination, and wind. To enable robust vocalization extraction, separate noise recordings from each zone and analyzed using the Welch method with a 16,384-sample FFT window. The resulting noise inventory (Table 4) summarizes the spectral range and amplitude of different noise sources. Drinking noise exhibited low frequencies around 20 Hz and broad high-frequency peaks up to 1,029 Hz; the mean peak amplitude across samples was ~−40 dB. Feeding noise (mix of hisses, horns, and gate impacts) had low frequencies from 30 Hz and high-frequency components up to ~567 Hz with similar amplitude. Milking noise from robotic equipment was dominated by low frequencies near 12 Hz and high frequencies up to ~300 Hz and was louder (mean amplitude ~−22 dB). Resting noise (urination and human speech) spanned 12–493 Hz with mean amplitude ~−21 dB. These profiles informed the design of a band-pass filter (150–800 Hz) to remove low-frequency machinery noise and high-frequency electrical hiss while preserving the vocalization band. By providing a quantitative noise inventory, our dataset allows researchers to reproduce the preprocessing pipeline and evaluate the robustness of acoustic features against background noise.

2.4 Annotation scheme and ethological foundation

A key novelty of the dataset is its detailed annotation scheme (Table 2) informed by ethological principles and welfare protocols. The annotation system organizes vocalizations into nine main categories:

Maternal & calf communication - includes calls such as Mother_Separation_Call (low frequency plaintive call when a cow is separated from her calf), Calf_Contact_Call (high frequency squeal when a calf seeks contact), and Maternal_Response_Call (mother cow responding back to her calves).

Social recognition & interaction - encompasses affiliative calls like Greeting_Moo, Group_Contact_Call, Response_Exchange_Call, Herd_Coordination_Call and Social_Bonding, reflecting social hierarchy and cohesion.

Estrus & mating behavior - includes Estrus_Call, characterized by loud high frequency bellowing signaling sexual receptivity; Mating_Excitement_Call; and Mounting_Associated_Call.

Feeding & hunger related - covers Feed_Anticipation_Call (calls before feeding), Feeding_Fustration_Call, and Chewing_Rumination_Sounds (non vocal chewing noises).

Water & thirst related - includes Drinking_Slurping_Sounds, Water_Anticipation_Call and Hydration_Distress.

Distress & pain - covers High_Frequency_Distress (intense distress vocalizations), Frustration_Call, Injury_Pain_Moo, Sneeze, Cough and Burp.

Environmental & situational - includes vocal responses to environmental stimuli like Weather_Response_Call, Transportation_Stress_Call and Confinement_Protest_Call.

Non vocal sounds - comprises non vocal behaviors such as Breathing_Respiratory_Sounds and Licking_Sounds.

Table 2

| Acoustic feature | Biological interpretation | Example call types |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental frequency (F0: mean, min, max) | Determined by vocal fold tension, length, and mass; high F0 reflects arousal, distress, or estrus, while low F0 indicates calm affiliative contact. | Estrus_Call, High_Frequency_Distress, low-frequency moos (contact) |

| Formant frequencies (F1, F2) | Resonances of the vocal tract linked to mouth opening, tongue/lip position, and body-size cues; larger F1–F2 separation often accompanies noisier or less harmonic structure. | Water_Slurping_Sounds, harmonic moo (stable formants) |

| Duration & timing (Start, End, Duration) | Persistence of calling; shorter calls often reflect neutral/positive states, whereas longer calls are associated with higher arousal or separation. | Mother_Separation_Call (long, low intensity); Feed_Anticipation_Call (short bursts) |

| Energy measures (RMS, intensity, time to peak) | Reflect call forcefulness and emotional valence; high RMS and fast time-to-peak indicate urgency, while low intensity with long duration suggests persistent, subdued calls. | Aggressive_Bellow, Frustration_Call; calf contact moo (low intensity) |

| Spectral centroid, bandwidth, roll-off, Zero-Crossing Rate (ZCR) | Differentiate harmonic vs. noisy events; high centroid/ZCR imply noisy or aperiodic content, low centroid indicates harmonic structure. | Sneezes, burps (high centroid, high ZCR); harmonic moo (low centroid, low ZCR) |

| Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs) | Capture global spectral shape and timbre; useful for subtle distinctions between similar call types, with MFCC-based estrus detection reported at >90% accuracy. | Feed_Anticipation_Call vs. Feeding_Frustration_Call |

| Voiced ratio | Proportion of voiced vs. unvoiced frames; distress calls tend to include more unvoiced segments, whereas nasal moos are almost fully voiced. | High-frequency distress calls (more unvoiced); nasal moos (fully voiced) |

Mapping of acoustic features to biological interpretation and representative call types in the dataset.

Each sub category is accompanied by a concise description (e.g., Estrus_Call is a prolonged high frequency call emitted by a receptive female; Feed_Anticipation_Call is a rhythmic moo produced when cows expect feeding). The categories deliberately span positive and negative welfare states in line with welfare science. Prior research supports this ethological structuring: high frequency calls with the mouth open are associated with distress or long distance communication, whereas low frequency calls with the mouth closed occur in calm social contexts (Jobarteh et al., 2024). Vocalization rates also provide behavioral cues—for example, (Röttgen et al. 2018) found that call rate peaks before estrus climax, and (Yoshihara and Oya 2021) linked increased formant frequencies to elevated cortisol during parturition. By capturing a wide range of vocal types and non vocal sounds, our annotation scheme enables analysis of both emotional valence and arousal, as recommended in contemporary animal welfare frameworks.

2.5 Rich metadata and FAIR compliance

The dataset is accompanied by a comprehensive metadata table (Table 7) describing each clip. Key fields include the unique file name, recording date, farm identifier, barn zone, microphone model, duration, pitch statistics (mean, minimum and maximum), and formant frequencies (F1 and F2), along with categorical annotations such as main category, subcategory, emotional context, confidence score, and textual description. Feature definitions follow acoustic and ethological conventions–for example, pitch relates to laryngeal tension and arousal, formant spacing reflects vocal tract length, and energy measures indicate call strength.

The metadata structure aligns with the FAANG (Functional Annotation of Animal Genomes) guidelines for animal metadata and adheres to the FAIR principles (Harrison et al., 2018). These principles ensure that datasets are described with rich metadata, use community standards, and are stored in formats that facilitate long-term reuse across research communities. Applying FAIR to bioacoustic corpora enhances transparency, reproducibility, and integration with other animal genomics and welfare datasets (Harrison et al., 2018).

Overall, the dataset's novelty lies in its scale, diversity, multi-microphone design, multimodal referencing, detailed ethology-driven annotation scheme, and metadata structure that complies with international standards. Compared with previous bovine vocalization studies that focused on small cohorts or narrow behavioral contexts, this corpus offers a more holistic and reproducible resource for advancing machine learning and welfare research in dairy cattle. Having established the dataset's scope and comparative novelty, we now describe the data collection process, including recording sites, equipment, and behavioral context capture.

3 Data collection

3.1 Recording sites

Data were collected from three commercial dairy farms in Sussex County, New Brunswick, coded FARM1-FARM3, all of which operated free-stall barns (Table 1). Farm 1 housed 57 Holstein cows, Farm 2 housed 207 cows in a mixed Holstein-Jersey herd, and Farm 3 housed 160 Holstein cows. Recording took place during sequential site visits (5–7 May 2025), ensuring coverage across farms under comparable seasonal conditions.

Each barn was divided into four monitored zones—drinking troughs, feeding alleys, milking parlor, and resting pens. Within each zone, microphones were installed at fixed mounting locations (for example above or beside water bowls, near feed mangers, or along the fronts of resting stalls) chosen to coincide with areas where cows repeatedly congregate. Rather than enforcing a single, fixed source-microphone distance, this design reflected how animals naturally move through these spaces. As cows approached, fed, drank, queued for milking, or lay down, their vocalizations were typically produced within a practical distance range of approximately 0.5–3 m from the nearest microphone, depending on their momentary position and orientation. This zone-based layout enabled simultaneous, zone-specific recording and provided systematic contrasts between different acoustic environments such as feeding areas, milking stations, and resting pens.

In addition, manual observation logs were maintained throughout, noting events such as feeding schedules, veterinary visits, or machinery maintenance. These logs ensured that contextual events were linked to the acoustic data, creating a diverse soundscape that is representative of everyday husbandry practices in Atlantic Canadian dairy barns.

To capture these environments effectively, a multimicrophone hardware setup was deployed, as described below.

3.2 Recording hardware and microphone placement

To ensure representative acoustic coverage, a multimicrophone array was deployed, combining directional shotgun microphones with portable recorders and one autonomous bioacoustics logger:

Sennheiser MKH 416—hypercardioid interference-tube shotgun microphone, widely used in film and wildlife recording. Its strong side rejection allowed capture of subtle vocal nuances despite barn noise (Sennheiser, 2023).

– Paired with Zoom F6—six-channel portable recorder powered via phantom supply. The F6 supported 32-bit float recording, dual A/D converters, and ultra-low-noise preamps, preventing clipping even during high-intensity calls (Zoom, 2023).

RØDE NTG-2—supercardioid shotgun microphone, battery/phantom powered, valued for affordability and portability, suited for close-range recordings in drinking and milking contexts (RØDE, 2023).

– Paired with Zoom H4n Pro—four-track handheld recorder powered by two internal AA rechargeable batteries. The H4n Pro included built-in X/Y stereo microphones, dual XLR inputs, and 24-bit recording with maximum SPL handling of 140 dB (Zoom, 2022). Two such RØDE NTG-2 + H4n Pro pairs were deployed for zone-specific coverage.

Wildlife Bioacoustics autonomous recorder—a single passive logger programmed for scheduled monitoring, especially in resting areas. It operated continuously on four AAA rechargeable batteries, enabling long-duration capture without human presence (Wildlife Acoustics, 2023).

File characteristics: Zoom F6 recordings were largest on average (~1.7 GB, mean peak amplitude −43.7 dB, 20–1,029 Hz range), followed by Zoom H4n Pro (~1.6 GB, −30.5 dB, 20–820 Hz). The autonomous logger produced smaller files (~308 MB, −20.1 dB, 12–893 Hz). By context, the drinking zone generated the largest raw data volume (~3.65 GB), followed by feeding (~1.7 GB), milking (~762 MB), and resting (~450 MB).

Cameras: Five fixed GoPro action cameras were installed above barn zones, recording continuously at 4K/30 fps with wide-angle lenses to cover feeding alleys, resting pens, drinking troughs, and the milking parlor. Cameras were synchronized with audio via a shared timecode feed.

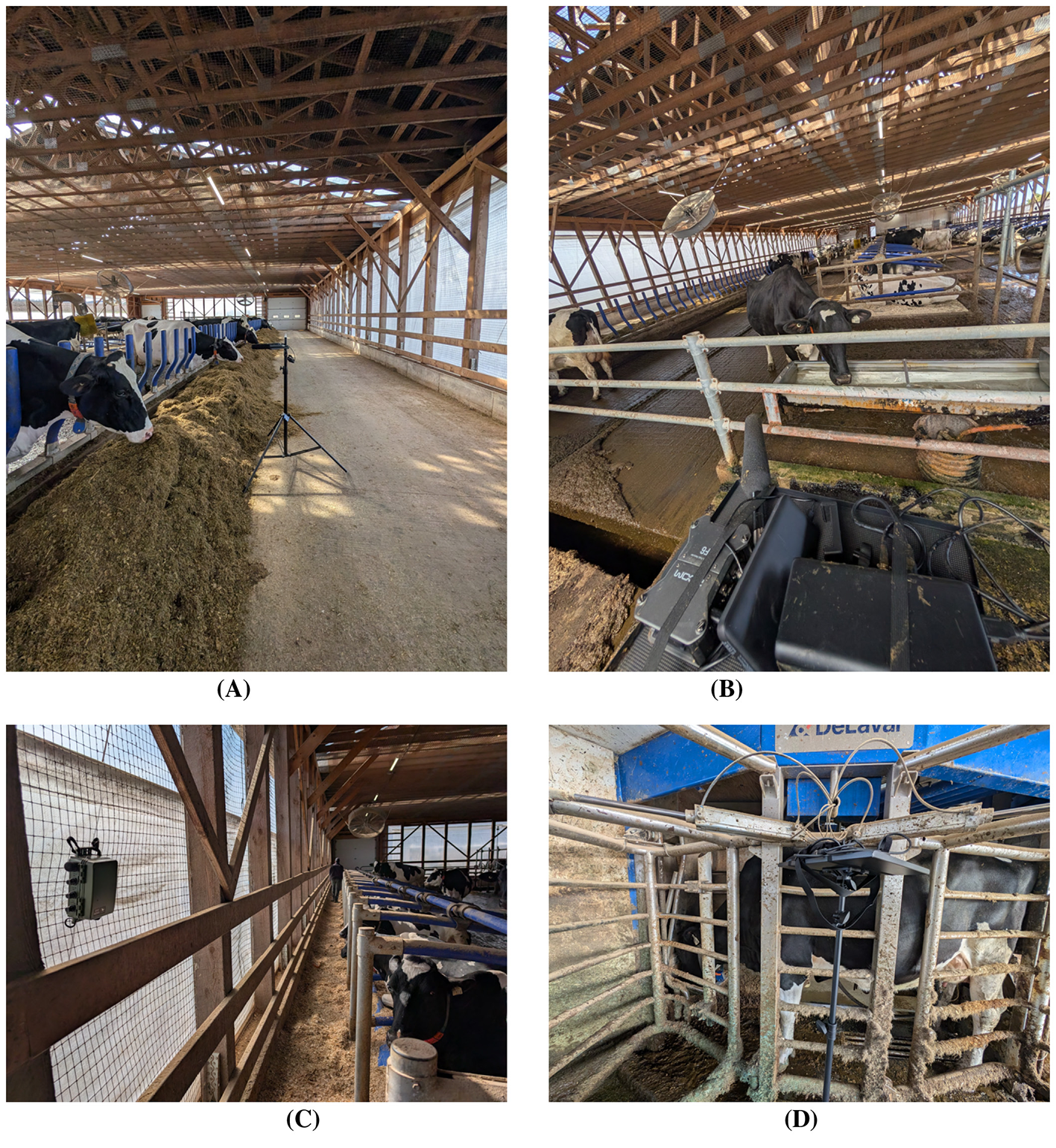

Placement strategy: Microphones were mounted on adjustable stands ~ 1 m above cow head height, oriented toward the zone center. This prevented contact with animals, minimized wall reflections, and ensured zone-specific capture. Cables were routed along beams and tripods stands and shielded to prevent chewing. The multimicrophone array (Figure 2) enabled concurrent multi-zone recording and cross-comparison of calls across environments.

Figure 2

Microphone setups across barn zones at Farm 1. (A) RØDE NTG-2 shotgun microphone positioned along the feeding alley to capture close-range vocalizations during feeding activity while minimizing side reflections. (B) Sennheiser MKH 416 directional microphone placed near the drinking trough to record high-clarity vocal and non-vocal events amid tractors and metallic noise. (C) Autonomous Wildlife Bioacoustics recorder installed in the resting zone to capture low-frequency moos and background group vocalizations without human presence. (D) RØDE NTG-2 with Zoom H4n Pro handheld recorder positioned near the milking station to document vocal and non-vocal sounds associated with handling and milking routines.

This combination of hardware provided complementary perspectives: phantom-powered Sennheiser + Zoom F6 setups for high-fidelity focal recording, AA-powered RØDE + Zoom H4n Pro pairs for flexible mobile coverage, and the AAA-powered Wildlife Acoustics logger for unattended long-term monitoring. Together with parallel video capture, the setup preserved both individual-level vocal features and group-level acoustic context, forming a robust foundation for behavioral and machine-learning analyses.

The full microphone and recorder specifications, including deployment zones, recording durations, file sizes, and frequency ranges for each configuration, are summarized in Table 3. Because cows moved freely within these monitored zones, the effective source-microphone distance varied naturally from call to call. In practice, vocalizations were usually produced when cows were at, or passing through, the focal locations (feed rail, water bowl, parlor entry, stall front), leading to a typical distance range of around 0.5-3 m from the microphone. This variability was intentional: the aim was to reproduce the acoustic conditions under which real farm monitoring systems would operate, rather than forcing a laboratory-style fixed geometry.

Table 3

| Microphone / Recorder | Key specifications | Deployment zone(s) | Rationale in barn context | Avg. size (MB) | Avg. duration | Peak (dB) | Freq. range (Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sennheiser MKH 416 (shotgun) + Zoom F6 | Hypercardioid, interference tube; 40–20,000 Hz; paired with 32-bit float recorder | Feeding alleys, resting areas | Extremely directional; avoids barn noise and prevents clipping during loud moos | ~1,738 | ~1 h 28 m | –43.7 | 20–1,029 |

| RØDE NTG-2 (shotgun) + Zoom H4n Pro | Supercardioid; 20–20,000 Hz; paired with 24-bit recorder | Drinking troughs, milking parlor | Affordable, portable; good for close-up calls with reduced side interference | ~1,555 | ~1 h 25 m | –30.5 | 20–820 |

| Zoom H4n Pro (built-in XY + XLR inputs) | Handheld, stereo + external inputs; 24-bit/96 kHz | Feeding and milking | Mobile capture, flexible for focal recording | – | – | – | – |

| Zoom F6 (standalone channels) | 6-channel, 32-bit float, dual A/D converters | Feeding/resting | Long sessions with wide dynamic range | – | – | – | – |

| Wildlife Acoustics logger | Passive autonomous system; duty-cycled | Resting pens, background | Continuous scheduled monitoring without human presence | ~308 | ~1 h 15 m | –20.1 | 12–893 |

Microphone and recorder setup used for barn vocalization recordings.

The directional characteristics of the MKH 416 and NTG-2 partially compensate for distance-related attenuation by preferentially capturing sounds within their frontal pickup patterns and suppressing much of the off-axis machinery and barn noise. At the analysis stage, our feature extraction pipeline includes amplitude normalization and z-score standardization, which reduces the influence of absolute intensity differences arising from distance variation. Moreover, the majority of the 24 acoustic features used in subsequent models–such as fundamental frequency, formant ratios, spectral centroid, and MFCCs–describe the shape and structure of the signal rather than its absolute amplitude, and are therefore relatively robust to moderate changes in distance.

Together, the zone-based, fixed microphone positions and distance-robust feature design ensure that the dataset captures realistic variability in recording conditions while remaining suitable for machine-learning applications.

3.3 Behavioral context capture

Audio alone rarely conveys the full meaning of vocalizations. To provide behavioral context, the project implemented a multimodal capture protocol. Behavioral video was recorded using the fixed GoPro cameras described above, and three researchers maintained manual notes documenting the time of day, weather conditions, feeding schedules, milking events, and notable social interactions or stressors between cows. The annotation framework was informed by Tinbergen's four questions (Bateson and Laland, 2013), which remain central in animal behavior research. In the context of cow vocalization, these can be adapted as follows:

Function (adaptive value): What role does a call serve in daily life? For example, does it facilitate feeding coordination, signal distress, or attract social attention?

Phylogeny (evolutionary background): How do vocal traits in dairy cattle relate to those seen in other bovids or domesticated species?

Mechanism (causation): What immediate physiological or environmental factors trigger a vocalization (e.g., hunger, pain, separation, handling, or barn noise)?

Ontogeny (development): How does vocal behavior vary with age, parity, or experience (e.g., heifers vs multiparous cows)?

By linking proximate mechanisms (physiology, environment) with ultimate functions (communication, adaptation), this framework strengthens interpretation of the dataset beyond acoustics alone. For instance, high-frequency open-mouth calls may be tied to immediate arousal or stress, while also serving long-term communicative roles within the herd (Jobarteh et al., 2024).

Audio-video alignment was performed manually. Instead of using automated synchronization hardware, researchers cross-referenced the timestamps of audio recordings with video footage and their own observation logs. This practical approach enabled vocal events to be matched with visible behaviors (such as feeding, resting, or responding to handling) without specialized tools.

3.4 File handling and storage

Field data were initially stored on the internal memory cards of the Zoom recorders and GoPro cameras. To prevent overwriting or accidental data loss, recordings from each farm were transferred immediately after the day's data collection. Files were copied to a secure laptop on-site and then uploaded to a shared Dropbox repository, ensuring both immediate backup and remote accessibility. Audio recordings were saved in WAV format (44.1 or 48 kHz, 24-bit depth) and named according to a structured convention: FarmID - MicrophonePlacement - BarnZone - Date - Time. Video files were stored in MP4 format with matching time stamps to maintain cross-referencing with audio.

To safeguard data integrity, the raw original files remain archived in Dropbox. For subsequent analysis steps such as preprocessing, cleaning, and segmentation, working copies were downloaded and processed locally, ensuring that the original dataset was preserved without modification. Metadata spreadsheets were updated during each transfer to log file names, times, equipment used, and backup status. This multi-stage handling approach–memory card → laptop → cloud backup → working copies–provided a robust and traceable workflow that minimized the risk of data loss and maintained strict separation between raw and processed datasets.

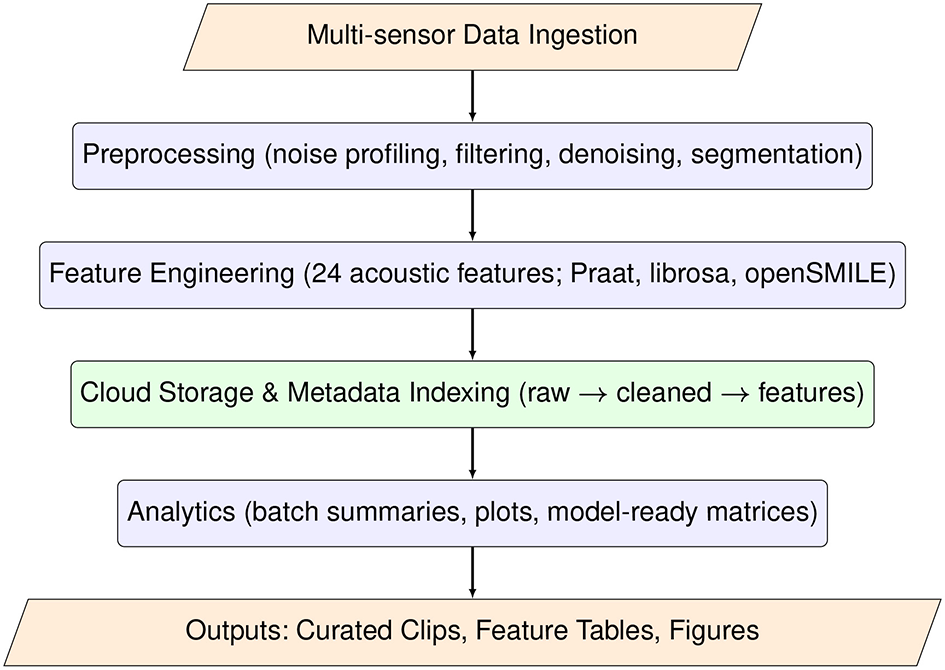

3.5 Data processing workflow

To efficiently manage and analyse the ~ 90 h of multimodal recordings (65 raw files; 65.6 GB), a modular and reproducible data processing workflow was established in alignment with FAIR and FAANG principles. Rather than a fully distributed computing system, this workflow is best understood as a set of clearly defined batch-processing stages that can be scaled to distributed or cloud-based frameworks in future work. The workflow (Figure 3) integrates five sequential stages, from ingestion to analytics, ensuring traceable and scalable processing of livestock bioacoustic data.

Figure 3

Modular data processing workflow for the bovine bioacoustics dataset, showing the sequential stages of data ingestion, preprocessing (filtering and denoising), manual segmentation, acoustic feature engineering, storage and metadata indexing, and downstream analytics and machine-learning.

Processing was performed on a workstation equipped with an Intel Core i9-12900K processor (16 cores, 24 threads), 64 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU (24 GB VRAM). Primary storage consisted of a 4 TB NVMe SSD, with continuous cloud backup to a 2 TB Dropbox repository for redundancy and remote access. All core steps were implemented in Python 3.10 using open-source libraries, ensuring that the workflow can be replicated without access to proprietary software. The workflow comprises the following components:

Data ingestion—Multi-sensor audio and video streams from the three farms were organized using a structured, time-stamped file-naming convention encoding farm, barn zone, date, time, and device ID. Raw WAV files (44.1/48 kHz, 24-bit) were ingested via Python scripts that used librosa for audio input/output and pandas for logging file-level metadata. This automated ingestion step standardized file formats, checked for corrupted or incomplete recordings, and populated metadata tables for downstream processing.

Preprocessing—Raw recordings were processed in batches following the standardized steps outlined in Sections 4.1-4.4, including spectral noise profiling, band-pass filtering, adaptive denoising, manual segmentation, and acoustic verification. Batch preprocessing was implemented in Python 3.10 to standardize signal quality across the heterogeneous barn environments. We applied a fourth-order Butterworth band-pass filter (50–1,800 Hz) using scipy.signal to isolate the frequency range relevant for bovine vocalizations and attenuate low-frequency machinery noise and high-frequency artifacts. Spectral gating-based denoising was then performed with the noisereduce library to suppress non-stationary background noise while preserving vocal structure. In parallel, manual segmentation was carried out in Raven Lite 2.0, using the spectrogram and synchronized video to identify individual vocalization events and exclude purely mechanical or non-vocal sounds.

Feature engineering—for each segmented clip, we derived a 24-dimensional acoustic feature vector designed to capture the key temporal, voicing, spectral, and cepstral properties of cattle vocalizations. Core source-related features (fundamental frequency, formant frequencies, intensity, and harmonic-to-noise ratio) were extracted using Parselmouth, a Python interface to Praat. Complementary spectral descriptors such as spectral centroid, bandwidth, roll-off, root-mean-square (RMS) energy, and zero-crossing rate, along with Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs), were computed using librosa (version 0.10.1). For cross-validation and extended feature sets, we additionally used openSMILE (version 2.3.0).

Storage and metadata indexing—Cleaned audio clips, feature tables, and contextual metadata were stored in a structured directory hierarchy that clearly separated raw and processed data and supported long-term reuse. Original recordings were archived in a /raw folder, denoised and filtered clips were stored under /processed, per-clip feature tables were saved in /features, contextual and schema information in /metadata, and annotation files (e.g., labels, time boundaries) in /annotations. This layout ensured that every processed object could be traced back to its raw source file and associated metadata.

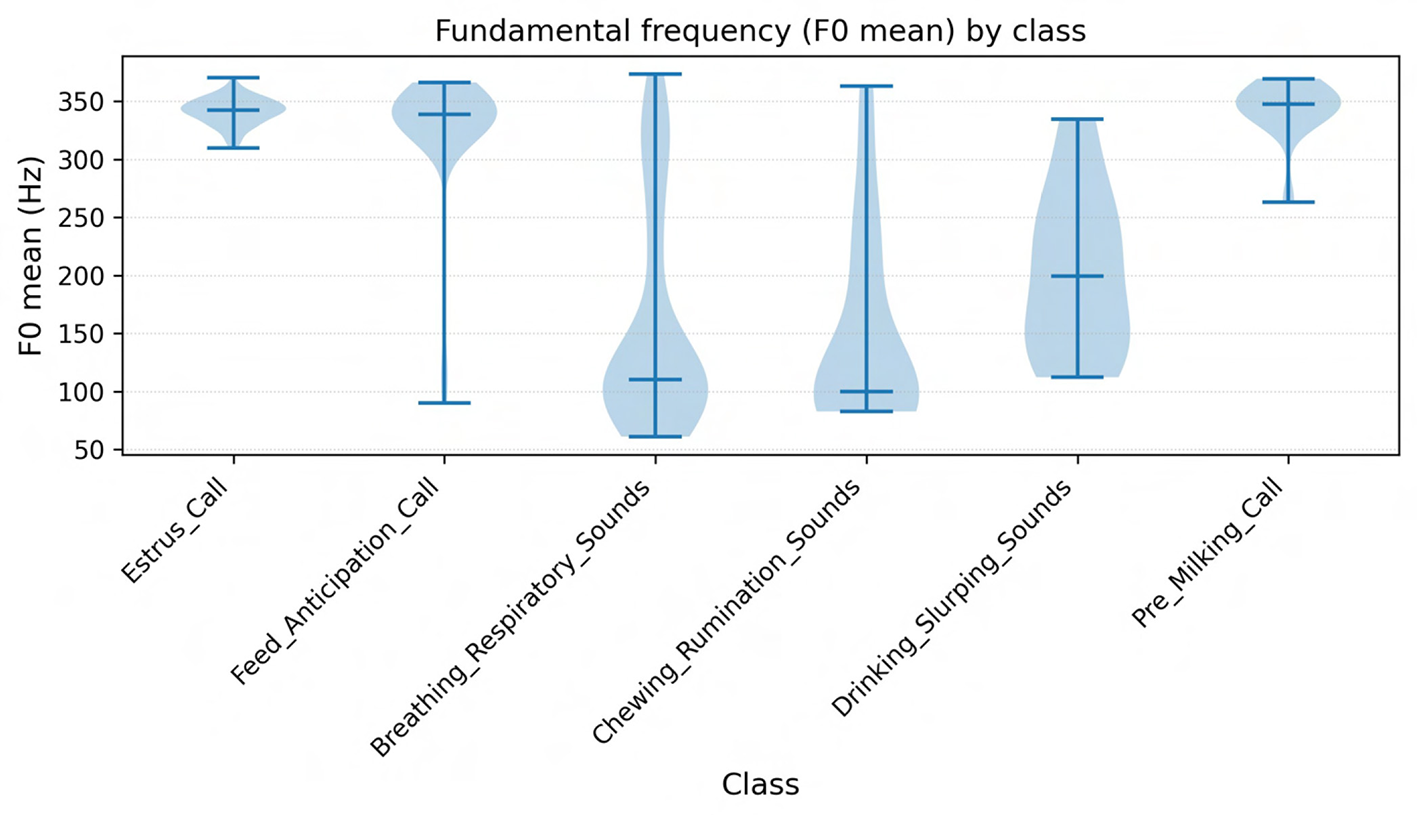

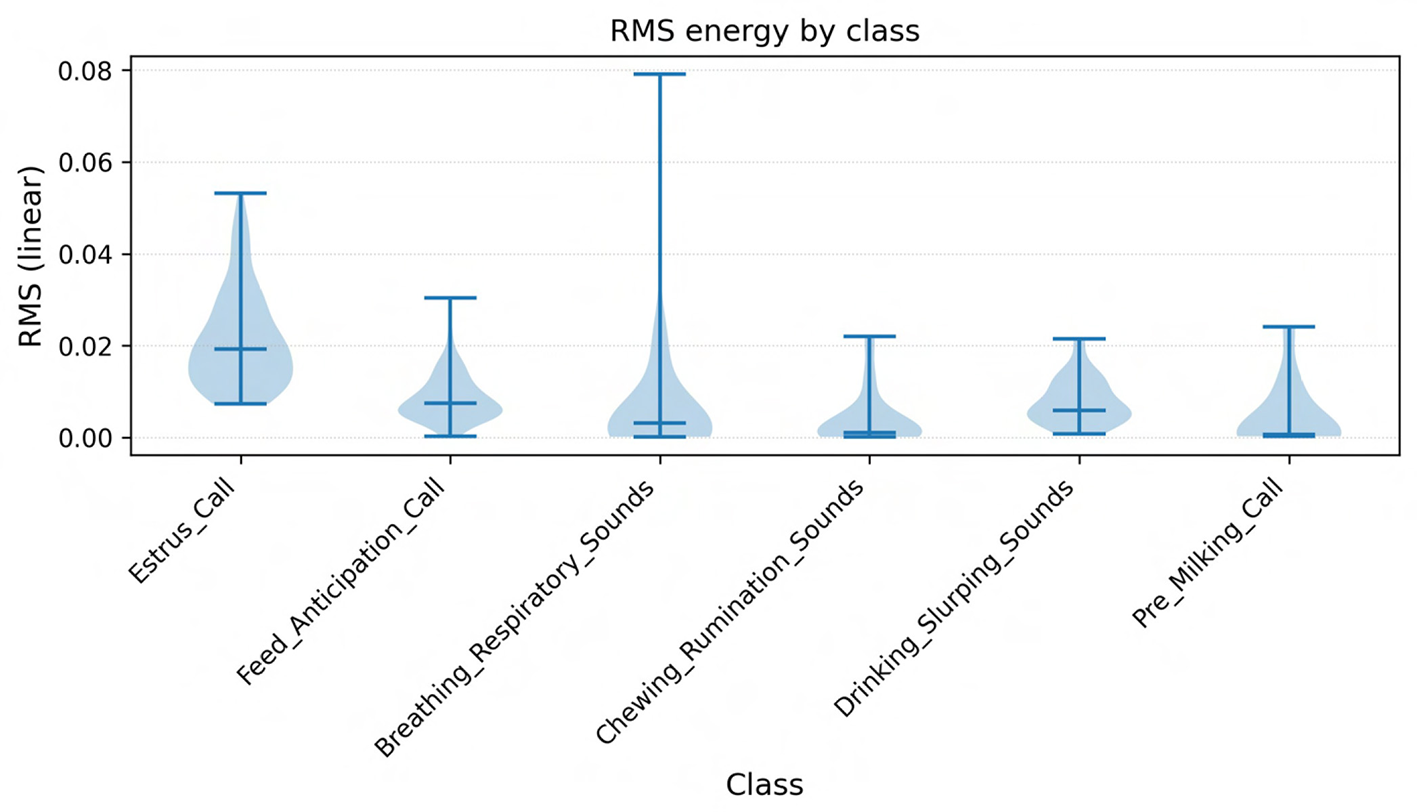

Analytics and output generation—Aggregated feature tables were analyzed using pandas and scipy.stats to perform descriptive statistics and inferential tests, including Kruskal-Wallis tests and Dunn's post-hoc comparisons. Visualizations such as violin plots, spectrogram panels, and Pareto charts were generated with matplotlib and seaborn to characterize class-wise distributions and dataset structure. Machine-learning models were trained and evaluated using scikit-learn (version 1.3.0) and PyTorch (version 2.0), enabling both classical and deep-learning approaches to be applied to the same standardized feature sets.

3.5.1 Scalability considerations

Although all analyses in this study were conducted on a single workstation, the modular design of the workflow facilitates future scaling. Ingestion, preprocessing, and feature extraction stages can be parallelised using frameworks such as Apache Spark or Dask; storage can be migrated to cloud object stores such as Amazon S3 or Google Cloud Storage for multi-site deployments; and the entire pipeline can be containerised using Docker to support reproducible execution across different computing environments.

With raw recordings secured across farms and barn zones, the following Section 4 details the preprocessing pipeline applied to enhance signal quality and prepare clips for segmentation and annotation.

3.6 Ethical approvals

All experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Dalhousie University Animal Ethics Committee (Protocol No. 2024–026). Data collection involved no physical interaction with animals, and all participating farm owners were fully informed of the study's objectives and provided written consent. In accordance with institutional and national ethical standards, data were obtained solely through passive audio, image, and video recordings.

4 Data preprocessing

4.1 Noise profiling

Noise spectral profiling was carried out as the first stage of preprocessing, since raw barn recordings contained a wide range of background sounds from machinery, metal gates, hoof impacts, people, and other animals. This process involved analyzing background noise patterns in terms of frequency (Hz) and amplitude (dB) in order to distinguish cow vocalizations from environmental sources. Noise-only segments were extracted from the recordings for each barn zone and analyzed using Audacity with the Welch spectrum function, configured with a 16,384-point FFT window, 50% overlap, and a logarithmic frequency axis. The Welch method was chosen because it averages overlapping segments, giving smoother spectra and suppressing transient spikes. Alternative methods such as Bartlett (less smoothing), Blackman-Harris (suited for controlled studio audio), and Hanning (unstable under noisy barn conditions) were considered, but Welch proved to be the most reliable for real-world farm recordings. The analysis revealed distinct noise signatures for different barn zones.

Drinking areas were dominated by metallic clanging of bowls, splashing at troughs, and bowel noise, with frequency peaks extending up to around 1029 Hz and mean amplitudes of approximately -60 dB.

Feeding zones produced a mixture of metallic impacts, compressed air hisses, and horn-like sounds, spanning 30–300 Hz with variable amplitudes.

Milking parlors were characterized by robotic systems, pumps, and vacuum lines, which generated relatively narrow frequency bands around 100–200 Hz but at higher amplitudes between -10 and -36 dB.

Resting areas contained low-frequency components between 25–80 Hz from urination, rumination, and equipment hum, combined with higher-frequency sounds such as people talking.

In addition, microphone hiss was consistently detected below 50 Hz across all farms and zones.

These findings were consistent with the expectation that barn-specific activities and equipment each contribute distinctive background noise signatures that overlap with the vocal frequency space of cows.

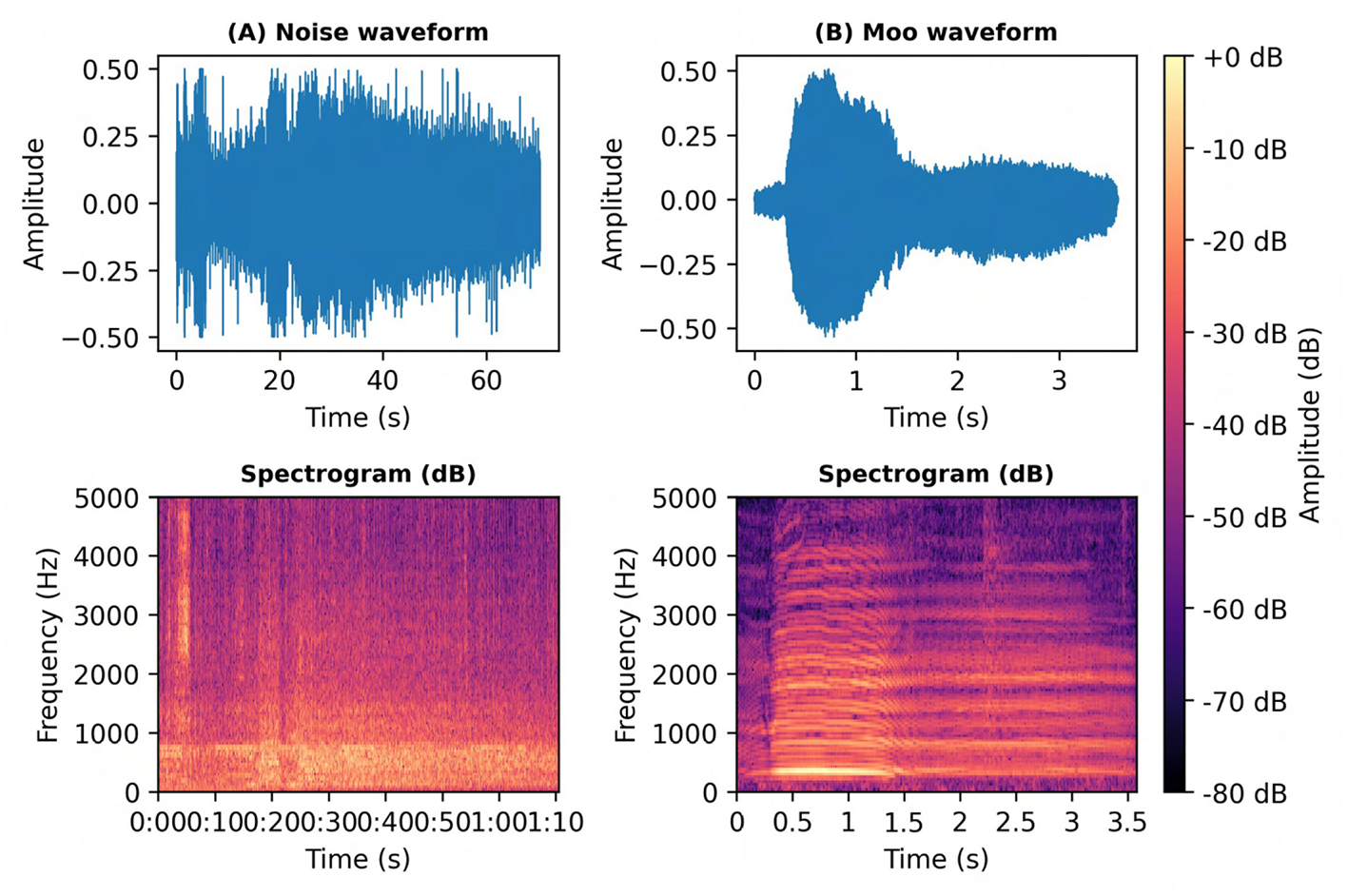

The profiles are summarized in Table 4, which presents the farm-wise and barn-zone-wise distribution of noise sources, frequency ranges, amplitudes, and the microphones used. This information directly informed the design of the filtering pipeline applied in subsequent preprocessing, where band-pass filtering was configured to retain the main vocal range (~ 100–1,800 Hz) while attenuating machinery hum, human speech, and high-frequency hiss. A representative spectrogram and waveform comparison (Figure 4) contrasts a cow vocalization with a noise-only segment, illustrating the necessity of noise profiling before segmentation and feature extraction. These zone-specific spectral noise profiles then directly informed the parameter choices for band-pass filtering and spectral denoising in the subsequent preprocessing stages (Sections 4.2–4.4).

Table 4

| Day | Farm | Category | Noise source | Low frequency | High frequency | Peak amplitude | Microphone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Farm 1 | Drinking | Metallic plates | 190 Hz | 655 Hz | −60.5 dB | Zoom F6 |

| Day 1 | Farm 1 | Feeding | Bowel movement | 229 Hz | 567 Hz | −54.8 dB | Zoom H4n |

| Day 1 | Farm 1 | Milking | Robotic milking system | 106 Hz | 127 Hz | −32.2 dB | Zoom H4n |

| Day 1 | Farm 1 | Resting | Tractor | 103 Hz | 120 Hz | −1.8 dB | Bioacoustics |

| Day 2 | Farm 2 | Drinking | Birds chirping | 421 Hz | 579 Hz | −25.7 dB | Zoom H4n |

| Day 2 | Farm 2 | Feeding | Metal plates | 164 Hz | 283 Hz | −58.2 dB | Zoom F6 |

| Day 2 | Farm 2 | Milking | Robotic milking system | 217 Hz | 301 Hz | −25.7 dB | Zoom H4n |

| Day 2 | Farm 2 | Resting | Microphone hiss | 12 Hz | 19 Hz | −13.9 dB | Bioacoustics |

| Day 3 | Farm 3 | Drinking | Hiss + urination sound | 91 Hz | 146 Hz | −24.6 dB | Zoom H4n |

| Day 3 | Farm 3 | Feeding | Hiss + tractor horn | 30 Hz | 72 Hz | −14.2 dB | Zoom F6 |

| Day 3 | Farm 3 | Milking | People talk + milking system | 100 Hz | 130 Hz | −5.4 dB | Bioacoustics |

| Day 3 | Farm 3 | Resting | Hiss | 25 Hz | 38 Hz | −20.3 dB | Zoom H4n |

Farm-wise noise spectral profiles across barn zones.

Figure 4

Comparison of barn noise and cow vocalization spectrograms. (A) Waveform and spectrogram of a barn noise segment dominated by broadband mechanical and environmental energy. (B) Waveform and spectrogram of a cow “moo” call recorded in the same acoustic environment, showing harmonic stacks and formant bands with periodic energy peaks. Spectrograms were computed using short-time Fourier transform and displayed in decibel scale relative to the maximum amplitude to enable direct visual comparison of spectral structure and signal clarity.

4.2 Band pass filtering

Based on the results of the noise spectral profiling and the known frequency ranges of bovine vocalizations, a fourth-order Butterworth band-pass filter was applied with cut-off frequencies set at 50 Hz and 1,800 Hz. This frequency range was selected to retain the majority of bovine vocal energy–where the fundamental frequency typically lies between 100 and 300 Hz and harmonics extend up to approximately 1,000 Hz–while attenuating low-frequency machinery hum below 50 Hz and high-frequency electrical hiss above 1,800 Hz. Previous studies have reported comparable ranges, noting that cattle vocalizations commonly exhibit fundamental frequencies between 80 and 180 Hz for cows and calves, with energy extending up to 1 kHz or higher in certain contexts (de la Torre et al., 2015; Briefer, 2012; Lenner et al., 2025). The Butterworth filter was chosen due to its maximally flat frequency response in the passband, which avoids distortion of harmonic structure and preserves acoustic fidelity. Its use is well established in acoustic and bioacoustic research as a robust method for isolating biologically relevant frequency bands (MacCallum et al., 2011; Simmons et al., 2022). To eliminate phase shifts that might affect later acoustic feature extraction, such as pitch contour or spectral energy analysis, filtering was implemented using zero-phase forward-backward filtering with the butter and filtfilt functions from Python's scipy.signal library.

This filtering step plays a critical role in the preprocessing pipeline. By suppressing spectral energy outside the vocalization band, it reduces broadband interference and makes the harmonic patterns of vocalizations stand out more clearly in spectrograms. This is particularly important in barn environments where background noise from ventilation systems, metallic clanging, and robotic milking machinery often overlaps with vocal frequencies in the 50–1,800 Hz range. While some overlap remains, the band-pass filtering substantially improves the signal-to-noise ratio, emphasizing the stable formants of cow vocalizations, which are most prominent between 200 and 400 Hz (Watts and Stookey, 2000; Green et al., 2019).

The filtering process also generates two outputs. First, spectrogram data are exported as a CSV file, providing frequency bins over time in tabular form, which enables automated detection of vocal events such as moos, sneezes, or coughs without continuous manual listening. Second, filtered WAV audio files are produced, which present reduced background hiss and rumble and therefore facilitate cleaner listening and manual annotation. Together, these outputs provide both a human-audible and machine-readable foundation for subsequent stages of analysis.

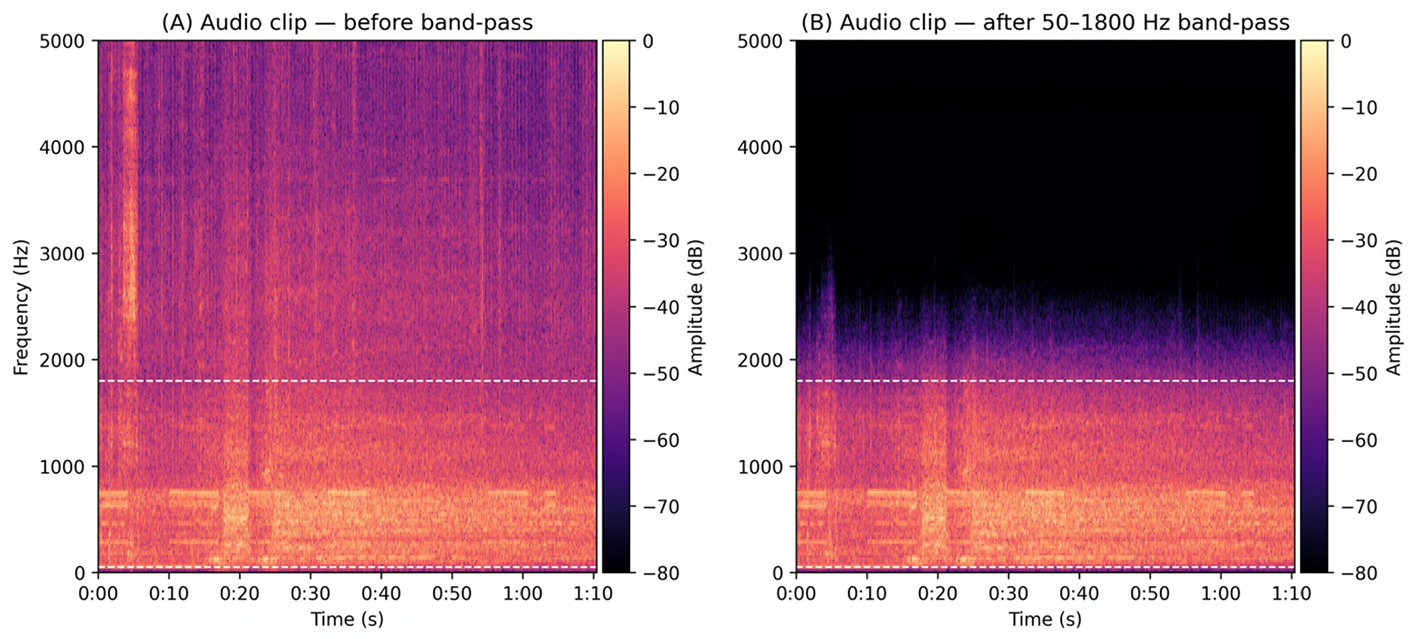

Although this step does not entirely eliminate overlapping barn noise within the vocalization band, it substantially improves clarity and prepares the audio for further visualization, labeling, and feature extraction. A side-by-side comparison of pre- and post-filtering spectrograms (Figure 5) illustrates the suppression of broadband noise while preserving the harmonic structure of cow calls.

Figure 5

Effect of band-pass filtering on an audio clip. (A) Spectrogram of the unfiltered signal showing broadband energy, including low-frequency hum and high-frequency hiss. (B) Spectrogram after 50–1,800 Hz band-pass filtering, with clear attenuation of energy below 50 Hz and above 1.8 kHz while preserving in-band harmonic structure. Dashed lines mark the passband; both panels share identical time and frequency axes (displayed to 5 kHz) and a common dB color scale for direct visual comparison.

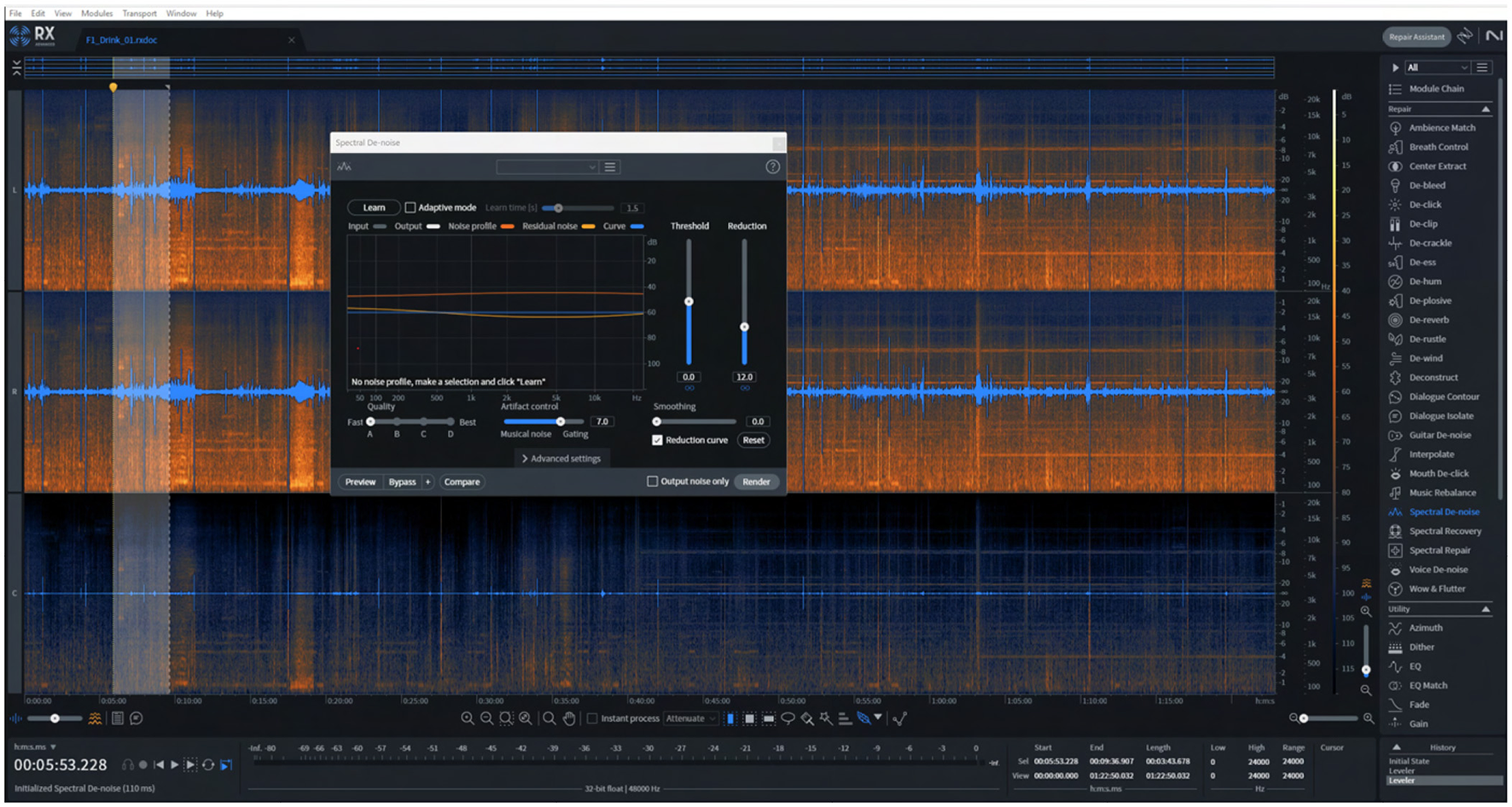

4.3 Noise reduction in iZotope RX 11

Following band-pass filtering, additional noise suppression was carried out using iZotope RX 11 (iZotope Inc., Cambridge, MA), a professional-grade audio restoration suite that offers fine-grained spectral editing, adaptive noise learning, and fault repair modules. Although iZotope RX is not yet cited in published bioacoustic studies, its functionality parallels classical spectral denoising and repair techniques long used in animal sound research (e.g. spectral subtraction, MMSE spectral estimators, wavelet denoising) (Xie et al., 2021; Brown et al., 2017; Juodakis and Marsland, 2022). More recently, methods such as Biodenoising adopt high-quality pre-denoising (often via speech-based or spectral tools) as pseudo-clean references for training animal-specific models, which further validates the use of advanced denoising tools upstream. RX 11 was chosen because it allows the user to visually inspect the time-frequency structure, select noise-only regions, build adaptive noise profiles, and non-destructively subtract noise while preserving the vocal harmonics of interest. This flexibility is especially useful in barn settings, where noise is heterogeneous (e.g. ventilation hum, mechanical clanks, electrical hiss) and overlaps in frequency with vocal energy.

We implemented a multi-stage noise reduction pipeline consisting of the following steps:

Gain normalization and DC offset removal to standardize amplitude baselines across recordings.

Spectral De-noise to compute adaptive noise estimates from silent (non-vocal) segments and subtract them from the signal.

Spectral Repair to mitigate transient artifacts (e.g., gate slams or rapid mechanical clicks) by interpolating across missing time-frequency bins.

De-clip and De-crackle modules to correct occasional saturation and impulsive noise events.

EQ Match to smooth the overall frequency response and compensate for microphone coloration, resulting in a more natural tonal balance.

This pipeline produced a notable improvement in signal-to-noise ratio, such that cow vocalizations became more distinct in spectrograms, with cleaner harmonic continuity and fewer artifact interruptions. The enhanced clarity aids both manual annotation and downstream segmentation or feature extraction. A screenshot of the RX 11 interface showing a spectral editing session (Figure 6) visually demonstrates how noise is isolated and removed while maintaining vocal structure. Although the approach does not fully eliminate overlapping noise within the vocal band, it significantly reduces interference and lays the foundation for robust event detection and feature analysis.

Figure 6

Spectral denoising of a cow vocalization in iZotope RX. Screenshot from iZotope RX (Spectral Denoise module) showing the noise-reduction workflow applied to raw barn audio prior to feature extraction. The (upper panel) displays the original spectrogram with broadband background noise typical of fan and machinery hum, while the (lower panel) shows the cleaned signal after adaptive spectral subtraction. Noise profile estimation was performed using a noise-only segment, and attenuation settings were tuned to preserve vocal harmonics while suppressing stationary low-frequency noise and high-frequency hiss. This preprocessing step enhanced signal-to-noise ratio and ensured clearer spectral features for subsequent analysis.

Because iZotope RX 11 is proprietary software, we implemented a fully open-source Python pipeline that closely approximates this multi-stage workflow and can be executed without commercial tools. Starting from the band-pass filtered audio described in Section 4.2, the Python script performs:

Gain normalization and DC-offset removal: Audio is loaded, the mean is subtracted to remove DC offset, and levels are peak- or loudness-normalized to a consistent, non-clipping range.

Broadband spectral de-noising: Non-stationary spectral gating with noisereduce attenuates barn background noise, using noise-only segments when available or adaptive noise estimation otherwise, with moderate reduction strength to preserve vocal harmonics.

Spectral repair of transient artifact: Short broadband transients (e.g. metallic hits, clicks) are detected in the STFT domain librosa and locally attenuated or smoothed in the time-frequency representation.

Optional de-clip and de-crackle: Clipped peaks are reconstructed by interpolation between unclipped neighbors, and fine impulsive crackle is reduced using simple median-style filtering, applied only when clear recording faults are present.

Spectral envelope / EQ matching: Average magnitude spectra of each clip are matched to a neutral reference using a frequency-wise gain curve numpy, scipy.signal, reducing microphone- and placement-dependent coloration.

This five-step workflow provides a transparent, fully reproducible alternative to the RX 11 chain; although the Python implementation follows the same processing philosophy and sequence, individual output waveforms will not match RX 11 results sample-for-sample and may differ slightly in residual noise and timbre. The complete Python implementation and configuration details for this pipeline are available in the GitHub repository referenced in the Data Availability Statement.

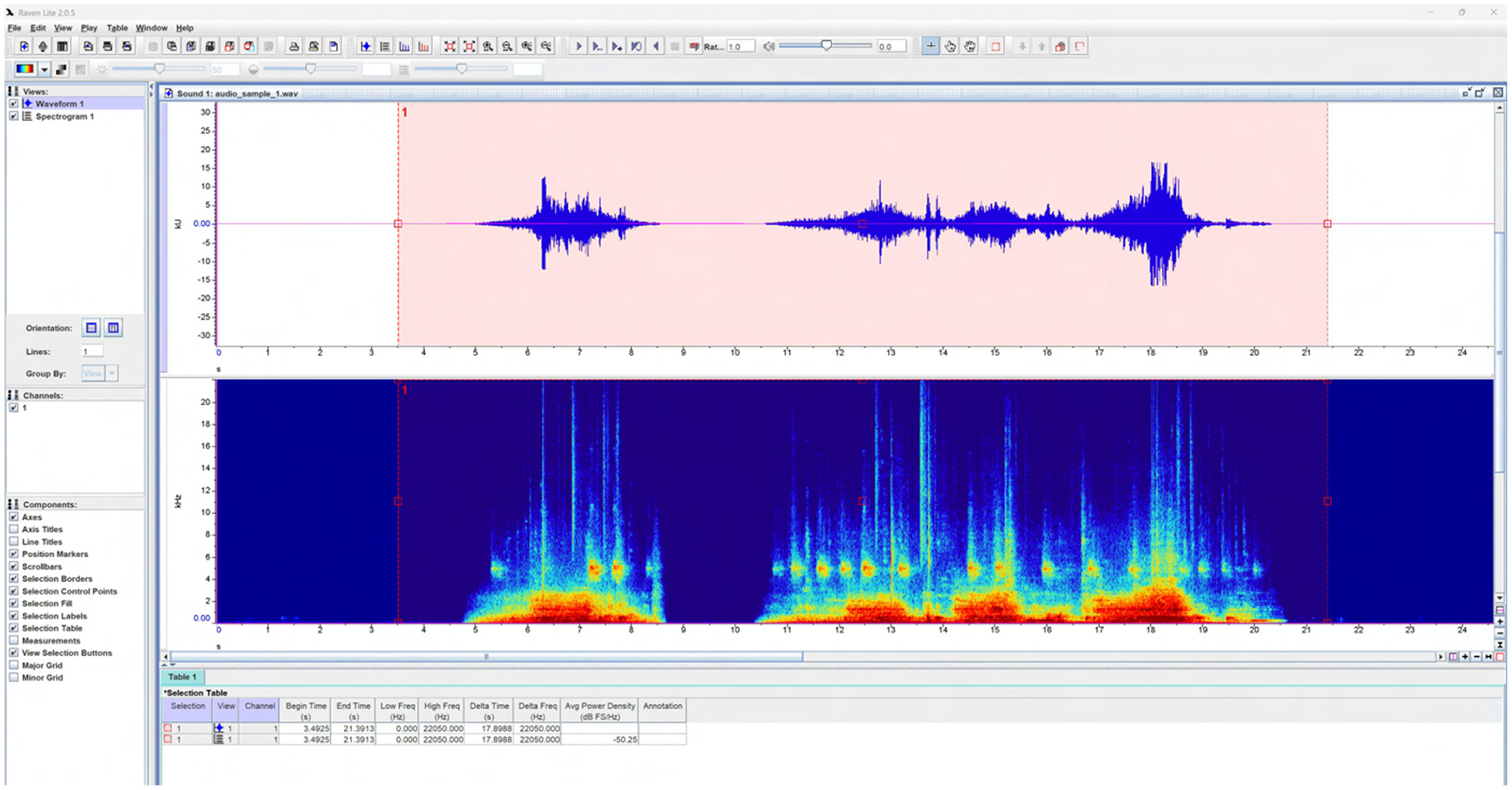

4.4 Segmentation with Raven lite and acoustic inspection in Praat

After denoising in iZotope RX 11, we segmented the continuous recordings into individual vocalizations using Raven Lite (Version 2.0). Raven Lite is a free audio analysis tool developed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and widely applied in ecological and behavioral bioacoustic studies (Dugan et al., 2016). Raven Lite was selected because it provides real-time waveform and spectrogram visualization with straightforward selection tools for manual clipping and export, and it is freely available and widely used in bioacoustic workflows. Although it lacks automated detection and batch-processing features available in Raven Pro, it was well-suited for the context-aware, manual segmentation required in this study.

We configured Raven Lite to display a short-time Fourier transform (STFT) spectrogram with a 1,024-point window, 50% overlap, and a Hamming window (Figure 7) which strikes a practical balance between time and frequency resolution for cattle calls. Candidate events were identified by visually scanning the spectrogram for harmonic stacks or broadband bursts and confirming each event by listening. Each clip was then extracted with start-end markers, and 2–3 s of padding were included on either side to preserve contextual cues (e.g., pre-onset inhalation, resonance tails). Onset was marked where amplitude rose above the noise floor and the first harmonic band became visible; offset was marked where energy returned to baseline–criteria consistent with common bioacoustic segmentation practice in livestock vocal studies (Meen et al., 2015).

Figure 7

Annotation of cow vocalizations using Raven Lite. Screenshot from Raven Lite showing manual annotation of vocalization segments on the spectrogram view. Each selection box corresponds to an identified call event, with start and end times marked based on visible harmonic onset and offset boundaries. This visual verification ensured accurate segmentation of vocalizations and exclusion of mechanical or environmental noise. Annotated time-frequency regions were later used as reference intervals for automated feature extraction and labeling in Python.

To maintain traceability, each selection was exported as a new WAV file and named with a structured convention encoding farm, zone, date, time, microphone, and a provisional class placeholder. Approximately 569 clips were extracted from 90 h of recordings. To reduce subjectivity, an independent second annotator cross-checked a subset of clips for boundary placement and completeness (inter-observer calibration), and we adopted a conservative policy of retaining extra seconds of context when uncertain.

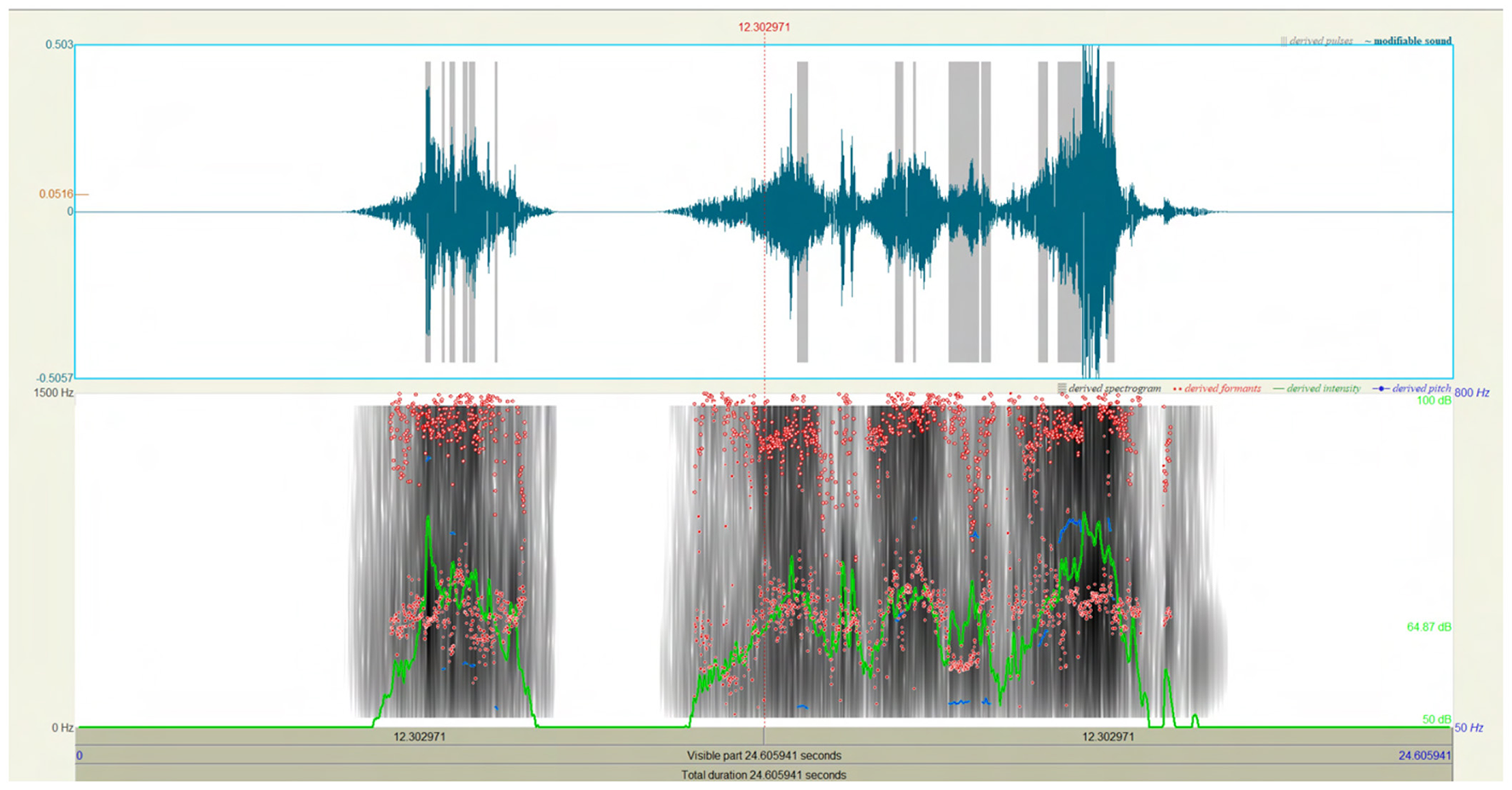

Following clipping, we performed acoustic inspection in Praat (Boersma, 2011) to verify segmentation boundaries and confirm that selections represented bona fide vocalizations rather than residual noise or mechanical transients (Green et al., 2019). In Praat (Figure 8), we inspected pitch contours (F0) and formant tracks (F1, F2) alongside intensity envelopes to check that harmonic structure was continuous within marked boundaries and aligned with cattle-vocal production expectations reported in prior work. We then bridged Praat to Python via Parselmouth (Jadoul et al., 2018) for scripted extraction of Praat-native measures (e.g., pitch range, formants, harmonic-to-noise ratio), and complemented these with librosa features (e.g., spectral centroid, bandwidth, roll-off, zero-crossing rate) for machine-readable descriptors used later in modeling. This combination ensured consistency between human-verified boundaries and algorithmic features.

Figure 8

Acoustic inspection and feature verification in Praat. Screenshot from Praat showing waveform, spectrogram, pitch contour (F0), formant tracks (F1-F2), and intensity envelope for a representative cow vocalization. Visual inspection in Praat was used to verify segmentation boundaries and confirm that selections represented bona fide vocal events rather than background transients. Continuous harmonic structure and expected formant trajectories were checked against known patterns of bovine vocal production, ensuring that annotated clips reflected valid call behavior prior to automated feature extraction and modeling.

Raven Lite's strengths at this stage are its stability, clear spectrogram interface, and low operational overhead for manual, context-aware segmentation; limitations include the lack of batch annotation and advanced detectors, which exist in Raven Pro and in research code. As the dataset expands, we anticipate scaling via semi-automated detectors (e.g., HMM/ML pipelines or Raven Pro's detection tooling) as demonstrated in related cattle-vocal detection studies. For the present work, however, manual segmentation with conservative padding and cross-validation produced a high-confidence corpus appropriate for downstream feature extraction and analysis.

To quantify how consistently this annotation protocol could be applied by independent observers, we conducted an inter-annotator agreement study on a stratified subset of clips, as described in Section 4.5.

4.5 Inter-annotator agreement and reliability

To assess the reliability of the behavioral and acoustic labels applied to the curated clips, we conducted an inter-annotator agreement study on a stratified subset of 150 audio clips. The subset was sampled to cover all nine main behavioral categories used in this study and the full set of 48 sub-categories, ensuring representation across diverse vocal types and barn contexts. Each clip in this subset was independently annotated by two trained observers following the same guidelines as described in Section 4.6, including assignment of a main category, sub-category, and associated contextual notes.

Agreement statistics were computed in Python using pandas and the cohen_kappa_score function from scikit-learn for nominal labels. A summary of inter-annotator reliability for both main and sub-category labels is provided in Table 5. The For the main behavioral categories (9 classes), direct comparison between Annotator 1 and Annotator 2 yielded a Cohen's κ of 0.884 with 90.0% raw agreement across the 150 clips, indicating high consistency in assigning broad behavioral classes. For the more fine-grained sub-categories (48 classes), inter-rater agreement remained substantial, with κ =0.699 and 71.3% raw agreement.

Table 5

| Comparison | Label level | Clips | Cohen's κ | Percent agreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annotator 1 vs Annotator 2 | Main category (9 classes) | 150 | 0.884 | 90.0% |

| Annotator 1 vs Annotator 2 | Sub-category (48 classes) | 150 | 0.699 | 71.3% |

| Final labels vs Annotator 1 | Main category | 150 | 0.930 | 94.0% |

| Final labels vs Annotator 2 | Main category | 150 | 0.954 | 96.0% |

| Final labels vs Annotator 1 | Sub-category | 150 | 0.832 | 84.0% |

| Final labels vs Annotator 2 | Sub-category | 150 | 0.860 | 86.7% |

Inter-annotator agreement for main and sub-category labels (150 clips).

We also evaluated agreement between each annotator and the final consensus labels, which represent the adjudicated “gold-standard” annotations used in the released dataset. Consensus labels (“Main Category final” and “Sub Category final”) were derived through joint review by both annotators and the lead investigator, with reference to spectrograms, waveform envelopes, metadata, and co-recorded video where available. For main categories, agreement between the final labels and Annotator 1 was κ = 0.930 (94.0% agreement), and between the final labels and Annotator 2 was κ =0.954 (96.0% agreement). The top confusing pairs are shown in Supplementary Figures S1, S2. These reliability outcomes confirm that the finalized labels provide a stable ground truth for subsequent first-level annotation and downstream behavioral analyses.

4.6 First level annotation

Each segmented clip was subjected to a first-level annotation by two researchers, who assigned multiple labels reflecting call type, emotional context, and confidence, as well as a behavioral summary. Specifically, for each clip the annotator recorded:

The main category and subcategory according to the scheme defined in Section 2.4, grounded in ethological typologies of vocalizing behavior;

An emotional context label (distress, pain, anticipation, hunger), reflecting the putative affective state at the time of vocalization;

A confidence score (1 = low to 10 = high) indicating the annotator's certainty in their labeling;

A textual description summarizing observable behavioral cues or situational context (e.g. “calf standing near water trough,” “cow waiting at feed gate,” “walking past milking parlor”).

Onset and offset boundaries were further refined within Praat to exploit its high-precision time measurement and pitch/formant display capabilities, allowing annotators to fine-tune temporal limits of calls. The annotation guidelines drew from ethological principles: calls were to be linked to proximate stimuli (e.g. feeding, separation, disturbance) and considered in light of possible ultimate functions (e.g. contact, distress, solicitation). In ambiguous cases or overlapping calls, the label “Unknown” was assigned for later review rather than forcing a classification. Annotators also consulted manual notes and co-recorded video when available to confirm behavioral context (for instance, verifying whether a cow was feeding vs. showing frustration). The output of this stage is a curated set of labeled audio clips, each with category, emotional valence, confidence, and behavioral description, ready for downstream feature extraction and statistical modeling.

In determining the type of call, annotators relied on the spectro-temporal shape (e.g. harmonic stacks, frequency modulation, call duration), amplitude envelope, and context. For example, low-frequency calls with stable harmonics might be assigned to contact or low-arousal categories, whereas calls with abrupt onset, rapid modulation, or high spectral energy could indicate agitation or alarm calls. This practice aligns with literature on cattle vocalization as communicative signals bearing information about motivation or affect (Green et al., 2018) and more broadly on vocal behavior as an “ethotransmitter” in mammals (Brudzynski, 2013). In recent machine-learning work (e.g. Gavojdian et al., 2024, “BovineTalk”), cattle calls are classified into low-frequency (LF) and high-frequency (HF) types—often mapping LF to close-contact or neutral states and HF to more urgent or negative states—which lends empirical precedent to our annotation categories.

In summary, the preprocessing pipeline we employed—spanning quantitative noise profiling, targeted filtering, professional denoising, careful segmentation, and this rigorous, context-aware annotation—addresses the challenges of noisy barn environments and produces a high-quality, well-documented corpus of vocalizations. This corpus forms a robust foundation for feature extraction and subsequent machine learning or statistical modeling. After preprocessing and initial annotation, we proceeded to compile the dataset through feature extraction, biological interpretation, metadata compilation, and exploratory analysis.

5 Dataset creation

5.1 Acoustic feature extraction

Once the segmented clips had undergone first-level annotation, we extracted a comprehensive suite of 24 acoustic features to characterize each vocalization, as summarized in Table 6. Feature computation was carried out using a combination of Praat, Parselmouth, librosa, and openSMILE, representing both traditional phonetic tools and modern signal-processing libraries. The features spanned temporal, spectral, and cepstral domains, with the aim of capturing both biologically interpretable measures and machine-readable descriptors commonly employed in animal bioacoustic research (Meen et al., 2015; de la Torre et al., 2015).

Temporal metrics included onset time, offset time, and call duration. Duration has been repeatedly linked to arousal and motivational state: shorter calls are more often associated with neutral or positive contexts, while longer calls typically reflect higher arousal or negative states (Brudzynski, 2013).

Signal quality was quantified using signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), allowing assessment of how clearly the vocalization emerged from the barn environment. High-SNR clips ensure more reliable feature measurement and downstream modeling.

Fundamental frequency (F0) was measured using Praat's autocorrelation method, with statistics for mean, minimum, and maximum F0 calculated for each clip. Cattle vocalizations generally fall between 50 and 1,250 Hz, with typical averages of 120–180 Hz. High-frequency calls near 150 Hz have been linked to separation distress, whereas low-frequency nasal calls around 80 Hz are associated with close contact and calming social functions (Watts and Stookey, 2000; Green et al., 2018; Gavojdian et al., 2024).

Intensity statistics (minimum and maximum dB) captured variation between quiet and forceful calls. In line with previous findings, higher-intensity calls often indicate urgency or frustration, while lower intensities correspond to calm affiliative contexts (Watts and Stookey, 2000).

Formant frequencies (F1, F2) were estimated using Praat's Burg method. Formants represent resonances of the vocal tract and provide cues to body size and vocal tract shape (Fitch and Hauser, 2003). In cattle, F1 and F2 have been documented in ranges between ~ 228 and 3,181 Hz, with average call durations of ~ 1.2 s (de la Torre et al., 2015).

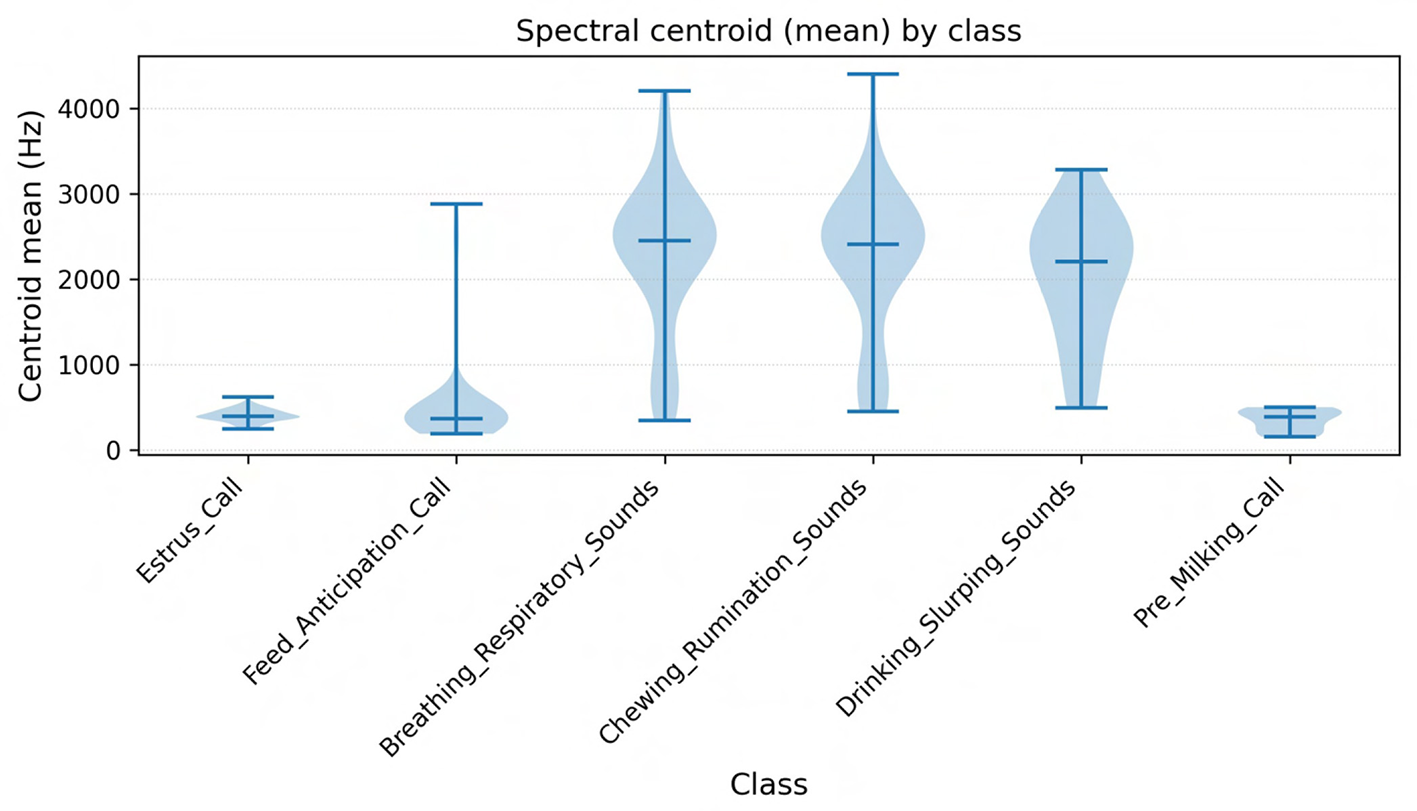

Band-level metrics were extracted using librosa, including bandwidth, RMS energy (mean and standard deviation), spectral centroid, spectral bandwidth, spectral roll-off (85/95), zero-crossing rate (ZCR, mean and standard deviation), and time to peak energy. These descriptors summarize the energy distribution and noisiness of the call. For example, high spectral centroid values correspond to brighter, noisier events (e.g., metallic barn sounds, snorts), whereas lower centroid values are characteristic of harmonic moos.

Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) (first 13 coefficients: mean and standard deviation) were computed using librosa and openSMILE. MFCCs provide a compact representation of vocal timbre and are widely used in classification of animal calls, including cattle vocalizations (Schrader and Hammerschmidt, 1997; Sattar, 2022).

Finally, the voiced ratio was calculated, representing the proportion of frames classified as voiced vs. unvoiced. High-frequency distress calls often exhibit more unvoiced frames due to glottal widening and turbulent airflow, while nasal low-frequency moos are typically fully voiced (Briefer, 2012).

Table 6

| Feature | Description | Extraction tool / method |

|---|---|---|

| Start time, end time, duration | Temporal metrics providing call timing and length. Duration has been linked to arousal and behavioral state: shorter calls often reflect neutral/positive states, longer calls higher arousal. | Praat / parselmouth |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Measures clarity of the call relative to barn noise; ensures robust downstream feature reliability. | Custom script (waveform-based) |

| Fundamental frequency (F0: mean, min, max) | Pitch contour statistics; cattle vocal range ~50–1250 Hz. High frequencies linked to distress/separation, low nasal calls (~80 Hz) to close contact. | Praat autocorrelation / Parselmouth |

| Intensity (min, max, mean dB) | Energy levels of the vocalization; high intensity = urgency/frustration, low intensity = calm contact. | Praat / Parselmouth |

| Formants (F1, F2) | Resonant vocal tract frequencies; provide cues to body size and vocal configuration. | Praat Burg method |

| Spectral centroid | Center of mass of spectrum; high values = bright/noisy, low values = harmonic moos. | librosa |

| Spectral bandwidth | Spread of spectral energy around the centroid. | librosa |

| Spectral Roll-off (85%, 95%) | Frequency below which 85% or 95% of spectral energy is contained. | librosa |

| Zero crossing rate (mean, std) | Rate of waveform sign changes; indicates noisiness/aperiodicity. | librosa |

| RMS energy (mean, std) | Root mean square energy; reflects call strength and stability. | librosa |

| Time to peak energy | Time taken for a call to reach maximum energy; a dynamic marker of urgency. | librosa / scipy |

| Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs 1–13: mean, std) | Cepstral features capturing vocal timbre; widely used in vocal classification. | librosa / openSMILE |

| Voiced ratio | Proportion of voiced vs. unvoiced frames; distress calls often more voiceless, nasal moos nearly fully voiced. | Praat / Parselmouth |

Acoustic feature set extracted from segmented cattle vocalizations.

All features were extracted at a sampling rate of 16 kHz (down-sampled from 44.1/48 kHz), which preserved the relevant bovine vocal bandwidth while reducing computational load.

Beyond numerical computation, these features hold biological meaning, which we interpret in the next subsection.

5.2 Biological interpretation of acoustic features

The selected features were chosen not only for their statistical utility in machine learning, but also for their biological interpretability. This dual emphasis ensures that computational models remain grounded in the mechanisms of cattle vocal production and their ethological significance.

Fundamental frequency (F0) is primarily determined by the length, tension, and mass of the vocal folds (Brudzynski, 2010). Increases in F0 are commonly associated with heightened arousal, separation distress, or estrus, while lower F0 is characteristic of calm affiliative calls (Green et al., 2018; Röttgen et al., 2018). In our dataset, calls labeled Estrus_Call and High_Frequency_Distress exhibited both elevated maximum F0 and greater F0 variability, consistent with reports that female cattle emit higher-pitched calls during estrus or when separated from their calves. Conversely, low-frequency nasal moos, typically around 80-120 Hz, were more often associated with affiliative or contact-seeking contexts, echoing findings from maternal-offspring communication studies (de la Torre et al., 2015).

Formant frequencies (F1, F2) reflect vocal tract resonances and convey information about articulatory configuration and body size (Fitch and Hauser, 2003). Lower formant values are linked to mouth opening and longer vocal tract length, while higher formants reflect tongue and lip positioning. In our data, Water_Slurping_Sounds displayed broad bandwidths and high F1-F2 separation, capturing their noisy, non-harmonic structure, whereas harmonic moos showed tighter clustering of F1 and F2 bands. This observation is consistent with earlier descriptions of formant dynamics in cattle vocalizations (Watts and Stookey, 2000).

Energy-based measures (RMS energy, intensity, and time to peak) further captured the dynamic and affective force of vocalizations. High RMS energy and short time-to-peak values were prominent in Frustration_Calls and Aggressive_Bellows, reflecting abrupt, high-force emissions. By contrast, Mother_Separation_Calls were lower in intensity but longer in duration, representing persistent vocal efforts at lower force levels, in line with observations of separation calls in cow-calf pairs (Green et al., 2019).

Spectral descriptors provided a robust means of distinguishing harmonic from noisy events. Spectral centroid and roll-off values differentiated stable harmonic moos from broadband, non-vocal sounds such as sneezes, coughs, or burps. These non-vocal events showed elevated centroid and zero-crossing rate values, indicating their noisy and aperiodic character (Meen et al., 2015).

Finally, Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) encoded global spectral shape and proved particularly useful for distinguishing subtle differences between similar categories such as Feed_Anticipation_Call and Feeding_Frustration_Call. This aligns with recent applications of MFCCs in livestock monitoring, where cepstral analysis has been shown to detect estrus events with accuracies exceeding 90% (Sattar, 2022; Gavojdian et al., 2024).

Taken together, these feature-behavior associations reinforce that the dataset is not only suitable for computational modeling, but also biologically meaningful. By anchoring machine-readable features to established ethological frameworks (Tinbergen's four questions; Dugatkin, 2020), the approach ensures that downstream classification and prediction retain relevance to animal welfare science and practical dairy farm monitoring.

To ensure each feature and annotation is transparent and reusable, we compiled a structured metadata schema.

5.3 Metadata compilation and schema