- Dallaire Institute for Children, Peace & Security, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada

Children are disproportionately impacted in fragile and conflict environments. Through a critical analysis of the ways in which violence is normalized and inherently gendered, this article explores the typology of violence embedded in fragile and conflict environments, the disproportionate impact of forced migration on children affected by conflict, how these interconnected forms of violence are gendered, and the importance of participatory and collective child protection and violence prevention action. Concluding with a discussion of the gaps in peace and security frameworks, the author identifies opportunities to strengthen child protection and recruitment prevention from a gender transformative perspective.

Introduction

Children are disproportionately impacted in fragile and conflict environments. Exposed to inadequate social protections and elevated risks for violence, children “bear the burden” of violence (WHO, 2014, p.9). While childhood is defined and understood differently, both regionally and culturally, for the purpose of this paper a child is defined as “every human being below the age of eighteen” based on the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). The use of the age of eighteen is also based on the special population status afforded to children in international law in relation to armed conflict and forced migration.

It is estimated that by 2030, over half of the world’s poor will be living in fragile and conflict environments, environments compounded by intensifying conflicts, inequitable climate change impacts, and unstable governance (World Bank, 2020). Today, global peacefulness continues to deteriorate with new and emerging tensions and threats to peace, such as a rise in terrorism and a growing recognition of the diverse health and socio-economic impacts of the global pandemic (Institute for Economics and Peace, 2020; OECD, 2020). These tensions and threats disproportionately harm marginalized communities, and in particular children within fragile and conflict environments (The Fund for Peace, 2020; World Bank, 2020). The complexities of these systematic problems and the lack of global leadership prioritizing the rights of children, lay the groundwork for multi-generational and disastrous impacts.

Forced displacement and migration are interwoven into the fabric of fragile and conflict environments. Understanding the relationship between forced migration and children affected by armed conflict requires a critical analysis that explores the ways in which violence is normalized and inherently gendered. Furthermore, our ability to create sustainable peace is predicated on the prioritization of children. The inclusion of children in the design and implementation of creative peace solutions–solutions that recognize the ways in which violence and peace are gendered–are essential to broader peace and security. This article will explore the typology of violence embedded in fragile and conflict environments, the disproportionate impact of forced migration on children affected by conflict, how these interconnected forms of violence are gendered, and the importance of participatory and preventative action. As Michel Chikwanine, a well-known human rights activist and former child soldier, recently stated: “we are witnessing a breakdown in humanity … and there is a cost of not doing something”.

Children and Violence–Setting the Context

Violence has significant and long-term consequences for millions of people around the world. It is estimated that in 2019 violence cost the global community $14.5 trillion in purchasing power parity (PPP) (Institute for Economics and Peace, 2020). The costs range from direct and visible consequences such as loss of life, destroyed infrastructure, and strains on health care systems, to indirect consequences such as the long-term impacts of disruptions to education and the toxic influence of the normalization of violence. While violence remains a global pandemic, the intensity and pervasiveness of the violence experienced in conflict and fragile environments, and particularly the violence experienced by children affected by armed conflict, is devastating.

The World Health Organization (2002) defines violence as: “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation” (p.5). From this perspective the WHO (2002) describes a typology of violence as occurring within three main categories: self-directed, interpersonal, and collective, where collective encompasses social, political and economic factors. The WHO (2002) typology offers important insights into how violence can be organized as harm to self, harm to others and harm to communities, however, focusing on trauma and the “results” of violence fail to consider the social norms of violence (Chaudhry, 2017; Denov and Akesson, 2017; Baillie Abidi, 2018). In order to address the roots and complexities of violence within fragile and conflict environments, a typology that brings further attention and analysis to how violence becomes normalized is required.

Johan Galtung (1969), Galtung (1996) articulated violence as a triangle of three interrelated types: direct, structural and cultural; direct being physical or visible violence such as punching or name calling; structural being systems of exploitation or marginalization such as sexism; and cultural as the normalizations of violence that enable direct and structural violence to occur, such as religious teachings that promote sex and gender-based violence. The violence triangle encourages a deep analysis of visible violence to examine where rules are formed, how leadership and decision making occurs, and how normative frameworks are designed and maintained over time. This kind of deep analysis is necessary when examining children’s experiences living in fragile and conflict environments, given the long-lasting impacts of colonization and the deeply penetrating structural and cultural violence impacting children (Chaudhry, 2017; Denov and Akesson, 2017; Kindersley and Rolandsen, 2019). As expressed in Sustainable Development Goal #16, “conflict, insecurity, weak institutions and limited access to justice remain a great threat to sustainable development” (UN General Assembly, 2015). These elements allude to the structural violence that as Chaudhry (2017) argues, both predate and live on after conflict. Therefore, violence transformation requires more than a recognition of and response to the consequences of violence, it requires an “understanding of how violence is learned and becomes embedded in society” (Baillie Abidi, 2018, p. 87). In this regard, Galtung’s (1969), Galtung’s (1996) violence triangle offers an interesting lens from which to further consider the intersections between conflict and fragile environments, children affected by armed conflict, forced displacement and migration, and the gendered realities of these intersecting forms of violence.

Children and Armed Conflict

Fragile and conflict environments often lack protective factors to ensure children’s health and safety, resulting in compounding and intersecting types of violence. During armed conflict children are exposed to, endure, and in some cases carry out extreme forms of violence. According to the United Nations Report of the Secretary-General on Children and Armed Conflict (2020), 24,422 grave violations were committed against children in 2019, an increase of 1,241 from the previous year, and these acts were largely inflicted by non-state actors. Grave violations against children include: killing and maiming, recruitment and use as soldiers, attacks on schools or hospitals, rape or other sexual violence, abduction, and the denial of humanitarian access (UN Security Council, 1999). While the number of grave violations occurring is alarming, it is important to recognize that challenges of underreporting, combined with the high verification threshold employed by the UN, results in significant underrepresentation of the violence experienced by children in armed conflict. The underrepresentation is particularly relevant for girls affected by armed conflict due to the perverse existence of sex and gender-based violence (Mazurana and Carlson, 2006; Denov and Ricard-Guay, 2013; Johnson and Walsh, 2020; Szabo and Edwards, 2020). Johnson and Walsh (2020) argue: “because of inherent male-centric understandings of conflict, girls and their unique experiences are often neglected or silenced in research, policy, and practice” (p.52). The gaps in research and policy exploring girls lived experiences, and particularly the experiences of girls recruited and used in violence, illustrates the inequitable gendered realities of conflict environments. Given contemporary armed conflict and the resulting consequences are changing (Whitman and Baillie Abidi, 2020), and that State-based conflict is at an all-time high (Palik, et al., 2020), a comprehensive understanding of the gendered impacts of violence on children in armed conflict is greatly needed.

Monitoring direct violence against children, as the UN annual report on the six grave violations is primarily designed to do, helps to paint a picture of the consequences and the significance of the issue of children affected by armed conflict. However, privileging the study of direct violence to the exclusion of a systematic analysis of the impacts and consequences of structural and cultural violence, fails to recognize how violence is influenced by deeply rooted relational, social and environmental factors (Galtung, 1969; Galtung, 1996). For example, the gap between the least and most peaceful or fragile countries in the world continues to widen, indicating a cautionary trend in growing global structural instability (Institute for Economics and Peace, 2020; OECD, 2020). Similarly, the rise in military spending combined with a decline in attitudes of positive peace are indicators of eroding peacefulness (Institute for Economics and Peace, 2020). According to the Institute for Economics and Peace (2020) “if the fall in Positive Peace continues, and the attitudes, institutions and structures that build and sustain peaceful societies are not supported and strengthened, it seems likely that the overall deterioration in peacefulness will continue in the years to come” (p.7).

From a structural violence perspective, the six grave violations interconnect with other forms of violence such as trafficking in persons and child labor, as the same factors that make children vulnerable to grave violations, enable other forms of violence against children to occur (O’Neil, 2018; Szabo and Edwards, 2020). The lasting impacts of colonization are a common link between these interconnecting forms of violence for children affected by armed conflict (Chaudhry, 2017). The resulting systems and structures that fail to recognize and protect children’s rights are demonstrations of structural violence. For example, when “a girl or boy who has been a commander of an armed group is considered an ‘ex-combatant’ rather than a child victim of a human rights violation” social injustice or structural violence occurs (Maguire, 2012, p.4). When children engaged in armed conflict are socially excluded due to their age, race, gender, or affiliation, structural violence occurs (Pepper, 2017). Furthermore, when systems and procedures designed to uphold children’s rights, fail to recognize sex and gender-based vulnerabilities, boys and girls can face enhanced risks for further manifestations of violence and a resulting failure to meet their basic needs. As a result of sex and gender-based structural violence, girls, and particularly girls in conflict environments who are experiencing broader and significant fragility issues, are at higher risk for extreme exploitation and abuse (OECD Development Policy Papers, 2019; Szabo and Edwards, 2020). In fact, “the most dangerous places for girls to live are countries affected by conflict” (Szabo and Edwards, 2020, p.27).

The structural frameworks that make children vulnerable to violence, such as differentiated access to health, education and social services, or the inequitable support afforded to children engaged in violence based on where they live or which armed group they are connected with, needs to be exposed and challenged. As Lederach (2005) stated: “breaking violence requires that people embrace a more fundamental truth: Who we have been, are, and will be emerges and shapes itself in a context of relational interdependency” (p.35). These relations are often built on foundations of gender, class and racial inequity. These relations are also built on age-based inequities. Children’s experiences, vulnerabilities and capabilities are shaped by many factors, but their “age is an important and underrecognized vector of oppression” (Pepper, 2017, p.84). Understanding how inequitable global systems influence peace and peacelessness, particularly in relation to children affected by conflict, are essential for transformative change. Moreover, understanding sex and gender-based structural inequities is essential in our collective efforts to increase child protection and reduce violence against children in conflict environments.

Armed conflict destroys much more than the physical aspects of our lives. The structural and cultural violence that establishes the conditions for armed conflict to occur and be sustained, can lead to the destruction of the social fabric of safety and protection, peace and solidarity. Graça Machel (1996) in their seminal report on the Impact of Armed Conflict on Children, stated:

These statistics [on children affected by armed conflict] are shocking enough, but more chilling is the conclusion to be drawn from them: more and more of the world is being sucked into a desolate moral vacuum. This is a space devoid of the most basic human values; a space in which children are slaughtered, raped, and maimed; a space in which children are exploited as soldiers; a space in which children are starved and exposed to extreme brutality. Such unregulated terror and violence speak of deliberate victimization. There are few further depths to which humanity can sink.

Machel’s statement speaks to the normalization of violence and that as a global community we have normalized children’s participation in violence–a stark example of cultural violence. Wessells (2006) extensive study with over four hundred children who were recruited and used as soldiers shares the same perspective and cautions against the militarization of young people as this approach can orient children toward violence instead of peace.

The links between the recruitment and use of children as soldiers and sustained conflict is undertheorized (Johnson et al., 2018; Whitman and Baillie Abidi, 2020). However, the relational disruptions that result from armed conflict have far reaching impacts for children, their families and their communities (Hettitantri and Hadley, 2017; O’Neil, 2018; UN SRSG on Violence Against Children, 2020; Whitman and Baillie Abidi, 2020). Collectively we are connected in a complex web of relations, where ideologies, normative frameworks and cultures are becoming immersed in the language of hate and deficiency instead of empathy, growth and solidarity. Lederach (2005) argues: “the quality of our life is dependent on the quality of life of others … the well-being of our grandchildren is directly tied to the well-being of our enemy’s grandchildren” (p.35). This relational understanding of the interconnections of our global systems is necessary to transform cultural violence, because if we do not “reduce the involvement of children in armed conflict today, we will only create more leaders that have been educated in violence for tomorrow” (Whitman and Baillie Abidi, 2020, p.36).

Boys and girls living in fragile and conflict environments, and particularly those who are recruited and used as soldiers, are exposed to and survive countless forms of violence. The power differential between adults and children often results in an increased risk for exploitation and abuse in conflict contexts, particularly for girls who endure elevated levels of gender discrimination and typically less opportunities for equality (Mazurana and Carlson, 2006; OECD Development Policy Papers, 2019; Johnson and Walsh, 2020). From a cultural perspective, sex and gender-based violence is so deeply engrained within religious and cultural normative frameworks that it remains embedded in social structures (Galtung, 1996). The combination of sex, gender, age, race, ability, class, and other identities such as group affiliation, can result in multiple levels of social exclusion for children. Understanding children and armed conflict from a direct, structural and cultural violence lens provides an analysis and critique of the systems that enable violence to occur and the diverse ways in which violence impacts children.

Children, Armed Conflict and Forced Migration

The conditions and drivers of forced displacement are extremely complex and constantly evolving. Increasing levels of violence and armed conflict and the resulting negative impacts on social systems have and continue to fuel the intensity of the forced migration crisis (Gieseken, 2017; Machel, 1996; O’Neil, 2018; World Bank Group, 2020). Dubbed the Decade of Displacement, over 100 million people were forcibly displaced between 2010–2019 (United Nations Human HCR, 2020). Today, 1 in every 97 people are forcibly displaced for increasing and often unpredictable lengths of time (United Nations HCR, 2020). Within this forced movement, children are among the most affected and at the greatest risk of multiple forms of violence (United Nations HCR, 2020).

Of the nearly 80 million people forcibly displaced today, 68% are from five conflict affected or fragile environments: Syria, Venezuela, Afghanistan, South Sudan and Myanmar (United Nations Human HCR, 2020). Further, 40% of those displaced are children - those under the age of eighteen (United Nations Human HCR, 2020). And alarmingly, in conflict affected countries such as Afghanistan and Somalia, children make up over 60% of those displaced (United Nations Human HCR, 2020). Given that half of the world’s poorest people will be living in fragile and conflict affected communities by 2030, and that forced migration is both a consequence of and directly influencing conflict, there is a great need to understand how these factors come together to impact peace and security (World Bank Group, 2019; OECD, 2020). As we approach the 70th anniversary of the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, and the 60th anniversary of the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, much work needs to be done to better understand the interconnections between forced displacement and conflict environments in order to enhance protective factors for children and prevent further escalations of violence.

The erosion of the social safety nets designed to protect children are glaringly apparent within the context of armed conflict and forced displacement. Whether children are forcibly displaced within or beyond their country of origin, the consequences are substantial (Dona and Veale, 2011; United Nations HCR, 2020). These consequences can range from increased risks for sexual abuse and exploitation, including trafficking in persons, to family separation, injury or loss of life (United Nations HCR, 2020). The recruitment and use of children in violence offers an illustration of the intricate connections between conflict and forced displacement (Machel, 1996; Achvarina and Reich, 2006; Dona and Veale, 2011). While some children recruited and used in conflict remain with their families or in their home communities, the majority endure the varied impacts of being forcibly removed from all they know. At the same time, it is equally important to highlight that children who are forced to remain in conflict affected areas, for instance children who are detained, or children who are forcibly confined, such as those in Gaza, are also exposed to and impacted by extreme and intersecting forms of violence. In essence, children face distinct barriers that need to be further explored when examining forced displacement and armed conflict.

From an economic perspective, the costs associated with forced displacement are the most significant costs of armed conflict today (Institute for Economics and Peace, 2020). In 2019, these costs surpassed $333 billion (Institute for Economics and Peace, 2020). Unfortunately, there is limited research exploring forced migration and children affected by conflict, and the analyses of forced migration costs lack particular attention to the specific experiences of, and impacts on, children (O’Connell Davidson and Farrow, 2007; United Nations HCR, 2020). Forced migration is often further compounded by multiple mediating factors such as climate crisis impacts. For example, recent floods in South Sudan resulted in the displacement of children who were already displaced by the protracted conflict in the region, adding to the complexity of children’s forced migration experiences (Cazabat et al., 2020). These complexities are further convoluted when we consider the relationality of forced migration and that the root causes have deep ties to colonization (Kindersley and Rolandsen, 2019).

From a structural perspective, migration has historically been framed in relation to the causes, such as poverty, where non-governmental organizations played a key role in supporting those directly affected (Zetter, 2017). Over the past few decades there has been a transition toward increased politicization of the polices, laws and practices that shape migration and the deep contradictions of governments championing humanitarian agendas for those affected by armed conflict but simultaneously enforcing laws and policies to exclude (Zetter, 2017; Navarro Vigil and Baillie Abidi, 2018). Dona and Veale (2011) argue that the nation (“community of belonging”) and the state (“legal, political and administrative apparatus”) are often incongruous and these contradictions form the root causes of many conflicts where rights are protected inequitably depending on whether the individual satisfies the qualifications of belonging, i.e., by race, religion, etc. In this regard, children forcibly displaced by conflict can experience a depreciation of their rights depending on where they fall in relation to nation vs. state alignment (O’Connell Davidson and Farrow, 2007; Onopajo, 2020). For example, children formerly recruited and used as soldiers are increasingly being viewed from a securitized perspective and in some cases being denied refugee status due to the perceived threat to the state (Achvarina and Reich, 2006; Dona and Veale, 2011). The precarity of the protection of the rights of children engaged in violence is directly tied to elements of structural violence that enforce discriminatory rules and practices and deny children protection based on politicized priorities instead of respect for their rights. This is particularly alarming given the recruitment of children by non-state armed groups is rising (O’Neill, 2018). In this way Dona and Veale (2011) further argue:

Our analysis has shown the existence of divergent discourses of children as both a product of and a threat to nation-state formation and maintenance. Orphans, separated children, unaccompanied minors, genocide survivors, or refugee children are visible mainly as a “product” of the system of nation-states, and are treated as its victims. Adolescents, former child soldiers, or street youth are visible but repeatedly perceived as a ‘threat’ to national and international unity and belonging (p.1280).

The toxicity of this structural violence is seen throughout history. For example, in post genocide Rwanda support and services were offered to child genocide survivor returnees but not to children associated with the violence or children of families accused of violence (Dona and Veale, 2011). Furthermore, the stigma for former child soldiers, and particularly for girls who were recruited and used as soldiers, often manifests in the lack of protection and inequitable application of the rules and laws designed to protect children (Child Soldiers International, 2017). Children who are forcibly displaced by conflict often “discover that the basic principles enshrined in the Convention (Convention on the Rights of the Child) do not necessarily translate into practice for them” (Dona and Veale, 2011, p.1287). Dr Benyam Dawit Mezmur, African Committee Expert on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, recently stated: “there are countless examples of where the ‘war on terror’ undermines the Children and Armed Conflict agenda, left, right and center.” The discriminatory application of children’s rights in the context of fragile and conflict environments is a stark example of structural violence.

Children’s experiences of forced displacement and migration are also shaped by cultural violence, including deep patriarchal influences. Gender inequalities are exacerbated in fragile contexts and the consequences of violence associated with armed conflict and forced migration are always gendered (Machel, 1996; Cockburn, 2013; World Bank Group, 2020). These gendered power dynamics manifest in the disproportionate distribution of resources, participation and power (OECD Development Policy Papers, 2019). For instance, the narrative of children recruited and used as soldiers almost exclusively focuses on boys, resulting in the invisibility of girls, leaving gaps in our understanding of the types and consequences of these intersecting forms of violence (Stromme Sapiezynska et al., 2020). The lack of a comprehensive gendered understanding of conflict in relation to children’s lived experiences, adds to the challenges of seeing and knowing why, how, and when violations against girls take place, particularly given the often privates spaces where sex and gender-based violence occurs (Stromme Sapiezynska et al., 2020). Private and public manifestations of violence against girls are tied together and linked to aspects of agency, power and social norms. For example, when exploring how and why girls become engaged in violence, many girls in contexts such as Colombia and Nepal cite domestic violence as a reason for joining armed groups (O’Neil, 2018; Kindersley and Rolandsen, 2019). The invisibility of girls’ lived experiences, the gendered realities of violence, and sustained sex and gender-based violence are as problematic in domestic contexts as during the complexities of forced migration.

While children experience many consequences of armed conflict and forced migration, the widespread use of sexual violence during crises disturbingly illustrates all three forms of violence: direct, structural and cultural. The UN (2017) defines conflict-related sexual violence as “rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, forced pregnancy, forced abortion, enforced sterilization, forced marriage, and any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity that perpetuated against women, men, girls or boys that is directly or indirectly linked to conflict.” The focus on direct violence, as depicted in the UN definition, allows us to have common terminology to name acts of sexual violence. However, the definition fails to address the structural and cultural forms of violence that enable these acts to occur in the first place.

There is growing recognition of the significant and systematic use of conflict-related sexual violence, as evidenced in UN Security Council Resolutions such as 1325 (2000) and 1820 (2008), and yet limited action focuses on conflict-related sexual violence perpetrated on children. Furthermore, while conflict-related sexual violence impacts boys and girls, girls are disproportionately impacted due to deep rooted sex and gender-based violence (Machel, 1996; Szabo and Edwards, 2020). Societal rules that discriminate based on sex and gender provide the context for violence to be normalized. For example, in South Sudan, early and forced marriage, domestic violence and sexual exploitation and abuse continue to impact peace processes and fail to foster communities where girls and women feel safe (UNSG, 2017). Gerecke, (2010) argues: “wartime sexual violence is caused by gender inequalities and skewed gender norms … ethnic norms act upon such inequalities and lead to sexual violence: women come to represent the honor of their community and shaming them becomes a strategic rational act of war”. The shaming and targeting of girls and women are both a driver and consequence of forced displacement and migration. While sex and gender-based violence is legitimized in most cultures and exist consciously and unconsciously in the spaces where rules, practices and norms are created and enforced, the normalization of this form of violence is nested deep within fragile and conflict environments (OECD, 2020).

Forced migration within fragile and conflict environments is fraught with cultural violence. The process of othering those forced to flee persecution has led to the notion of the dangerous other (Navarro Vigil and Baillie Abidi, 2018). As the notion of the dangerous other becomes institutionalized within laws and policies, structural violence flourishes. It is also important to highlight that the power differential between displaced persons is magnified in the case of forcibly displaced children, a relational and structural element that requires significant attention (Clark-Kazak, 2012). Valencia Arias (2012) stated: “This permanent state of confrontation leads to children and young people internalizing violent modes of resolving differences and conflicts as natural” (p.12). The normalization of violence becomes so deeply engrained in practice and perspective that safety and security become an unfamiliar experience and “little by little, make them [children] accustomed to living with conflict, where anyone could be the enemy and where they are constantly adrift, physically and morally, feeling insecure and fearful in their own homes, in their own land” (Valencia Arias, 2012, p.12). For children forced to migrate, perspectives on safety and security are further compounded by changing environments, communities and supports and the precarity that accompanies forced displacement. These practices and perspectives are also influenced by the interwoven relationship between vulnerability and resiliency (Navarro Vigil and Baillie Abidi, 2018). Transforming violence in complex and conflict contexts requires a critical gender and cultural violence analysis of the interconnections between forced displacement and armed conflict, with a particular focus on children, both boys and girls.

Protection, Prevention and Participation

The United Nations declared 2001–2010 as the International Decade for a Culture of Peace and Non-violence for the Children of the World in order to enhance protection for society’s most vulnerable and to build a global collective oriented toward transformative change. A Culture of Peace was defined as:

A set of values, attitudes and behaviors that reflect and inspire social interaction and sharing based on the principles of freedom, justice and democracy, all human rights, tolerance and solidarity, that reject violence and endeavor to prevent conflicts by tackling their root causes to solve problems through dialogue and negotiation and that guarantee the full exercise of all rights and the means to participate fully in the development process of their society (UNESCO, 1998).

This vision of a Culture of Peace was intended to build community dialogue and an increased sense of collective responsibility for children and the future of humanity. From this perspective, eight domains of action were identified (UN, 1998): 1) “foster a culture of peace through education; 2) promote sustainable economic and social development; 3) promote respect for all human rights; 4) ensure equality between women and men; 5) foster democratic participation; 6) advance understanding, tolerance and solidarity; 7) support participatory communication and the free flow of information and knowledge; and 8) promote international peace and security.” Twenty years later, the global community must ask if we have advanced toward a Culture of Peace or if the decrease in peacefulness and the rise in fragility are calling on all of us to reimagine how children are protected, how violence is prevented, and how children can be engaged differently to build more peaceful communities.

Protection

Many frameworks exist aiming to protect children affected by armed conflict. For instance, International Humanitarian Law affords protection to children forced to migrate in contexts of armed conflict (Gieseken, 2017). Within International Humanitarian Law there are four main areas of protection: the prohibition of the recruitment and use of children as soldiers; the responsibility to safeguard education during armed conflict; standards and rules regarding how children are to be treated while in detention; and rules to standardize the treatment of unaccompanied children (ICRC, 1949). International Human Rights Law, particularly the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), also affords special protections for children affected by armed conflict and emphasizes above all else that actions must always take into consideration the best interest of the child (United Nations, 1989). The African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child is another example of a protection framework that articulates special protection for children affected by armed conflict (OAU, 1990). The protection frameworks exist, the question is are they working.

In addition to, and complimentary to the hard laws that protect children, there are political frameworks that seek to enhance protections for children affected by armed conflict. The Paris Commitments to Protect Children Unlawfully Recruited or Used by Armed Forces or Armed Groups (“The Paris Principles”) addresses the issue of the recruitment and use of children and identifies particular vulnerabilities for girls and internally displaced children (UNICEF, 2007). The Safe Schools Declaration focuses on the protection of education from military use or attack, including protection for students, teachers and educational facilities (The Global Coalition to Protection Education from Attack, 2015). Additionally, the Vancouver Principles on Peacekeeping and the Prevention of the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers focuses on the role of the security sector to protect children from being recruited or used in violence (Government of Canada, 2017).

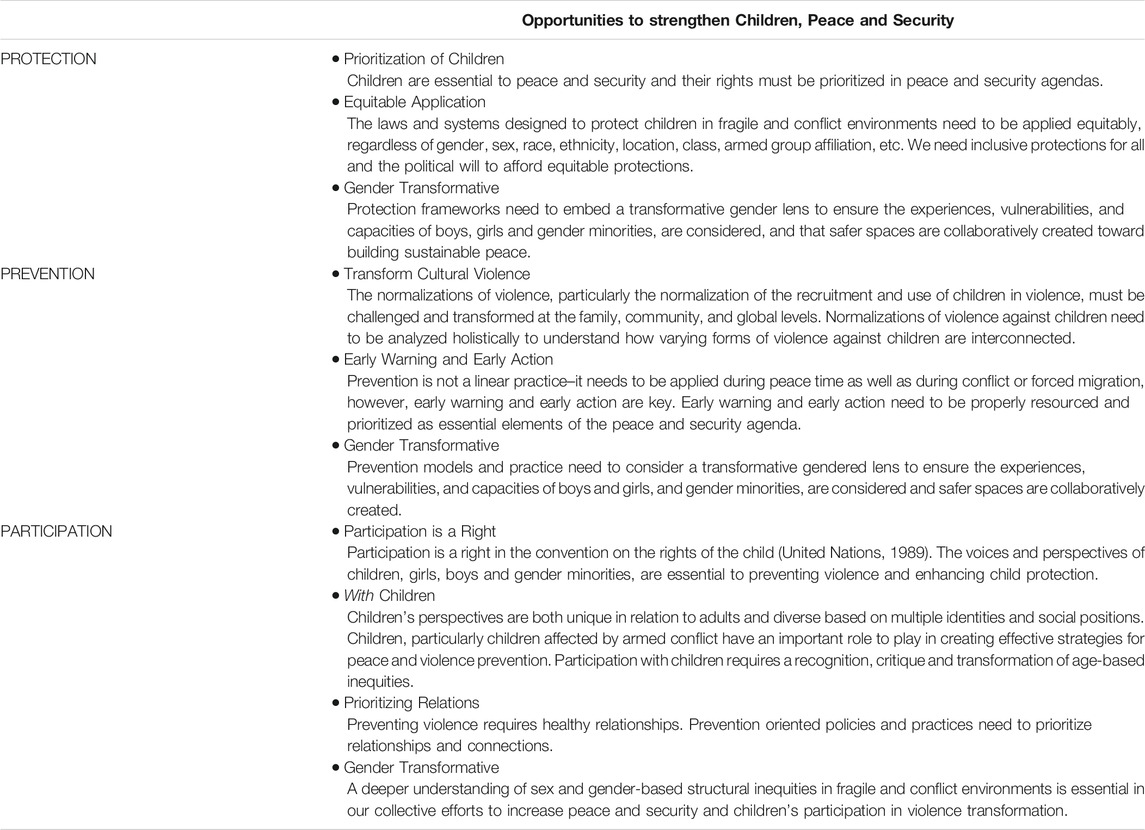

While many international frameworks focus on the protection of children, children are typically categorized as special populations in need of special protections, all of which are captured in specialized laws, policies and commitments as opposed to being fundamental to overall peace and security instruments. For instance, Palik’s et al. (2020) extensive analysis of global conflict trends and the Institute for Economics and Peace (2020) Global Peace Index, fail to consider children in their analysis and neglect to recognize the importance of children in relation to overall peace and security. These kinds of shortcomings illustrate why there has been a need to create specialized frameworks and political commitments focused on children. Understanding the strategic significance of children in relation to long term peace and security requires the protection of children’s rights to be centralized as a foundational indicator for global peace (Table 1: Opportunities to Strengthen Children, Peace and Security).

TABLE 1. Opportunities to Strengthen Children, Peace and Security. The following table offers a summary of the opportunities to strengthen child protection and recruitment prevention from a gender transformative perspective.

Over time protection frameworks have been critiqued, and in some cases enhanced to consider additional lenses of vulnerability and resiliency, in order to improve equitable application. Understanding the diverse ways in which violence impacts children from direct, structural and cultural violence lenses, including the barriers experienced by children affected by armed conflict and forced migration, is essential. The laws and systems designed to protect children in fragile and conflict environments need to be applied equitably, regardless of gender, sex, race, ethnicity, class, location, armed group affiliation, etc. We need inclusive protections for all and the political will to afford equitable protections (Table 1: Opportunities to Strengthen Children, Peace and Security).

Equitable application of child protection frameworks require a gender transformative approach. International legal frameworks and child protection instruments are often written in gender neutral ways, failing to consider how violence is a gendered experience with gendered consequences, as illustrated, for example, by the unique experiences and roles performed by girls recruited and used as soldiers (Leibig, 2005). The Convention on the Rights of the Child originally excluded considerations for gendered experiences or sex and gender-based violence. Similarly, the Optional Protocol on the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict (OPAC) was written with gender-neutral language, neglecting the gendered realities of boys’ and girls’ experiences in conflict (Leibig, 2005). Brown et al. (2019) argue that “a gender unaware approach, in a context with gender inequality, will likely be gender unequal, increasing the marginalization and vulnerability of groups who have less power and influence” (p.1). For instance, it was not until the Foca case at the International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia (ICTY) that systemic sexual violence and crimes against humanity specifically against women and girls was considered. Protective frameworks that endorse structural violence, implicitly or explicitly, sustain violence and today more than ever, we need inclusive protections for all. Protection frameworks need to embed a transformative gender lens to ensure the experiences, vulnerabilities, and capacities of boys, girls, and gender minorities, are considered, and that safer spaces are collaboratively created toward building sustainable peace (Table 1: Opportunities to Strengthen Children, Peace and Security).

Prevention

Prevention is hard work–work that must be sustained in peace time as well as during armed conflict and forced migration (Whitman and Baillie Abidi, 2020). Understanding the risk factors or vulnerabilities for violence against children in fragile and conflict contexts, as well as understanding the protective factors which reduce children’s exposure to and experience of violence, are essential in the creation of prevention-oriented laws, policies, practices, and norms. For prevention to truly be effective, normalizations of violence, and particularly normalizations of violence against children, must be challenged and transformed (Table 1: Opportunities to Strengthen Children, Peace and Security). Whitman and Baillie Abidi (2020) argue: “Deep-rooted attitudes and behaviors must change with respect to violence against children. This applies to norms around discipline and the use of violence in communities, schools, and families, as well as a need to build upon positive social norms to overcome entrenched beliefs that condone violence against children” (p.29).

While protective frameworks evolve toward inclusivity and a more concentrated focus on prevention, and while ratification and endorsement continue to grow, implementation of the laws and political commitments designed to protect children are often lacking (Montenegro Oporto, 2020). Alarmingly, the application of these protections appear to be predicated on which label a child is associated with and where the child is coming from. In many cases the label of internally displaced or unaccompanied child results in an affinity for protection and support, while the label of child soldier or terrorist almost guarantees a reduced level of protection in most States (O’Neil, 2018). The inconsistent application of law, policy and practice demonstrate how structural violence functions to disproportionately impact children, and particularly children recruited and used in violence. These demonstrations of structural violence are built upon cultural violence that affords differing value of life to children based on centuries of sustained discrimination. Article 19 of the CRC (United Nations, 1989) exposes how normalizations of violence against children are global and pervasive:

Violence against children is widespread and extremely damaging. Much violence is hidden behind closed doors, including in the family home, schools, care homes, detention centers and other institutions. However, in many States, laws prohibiting violence are non-existent or inadequate. In the majority of countries, children can be hit by adults as a form of ‘discipline’–an act that would be treated as a criminal offense if committed against an adult.

The evolution of the protections for children in conflict, and the extensive gaps in implementation, offer insight into the functionality of direct and structural violence and exposes how instruments designed to protect children need to further consider how cultural violence influences and infuses within the progressive approaches to violence reduction. Thus, in order to truly protect children, violence prevention must be prioritized. In this regard, early warning and early action in relation to conflict prevention is critical to disrupt and transform cycles of violence (Palik et al., 2020; Whitman and Baillie Abidi, 2020). Prevention efforts must move upstream to enable early warning and early action if sustainable peace is to be realized. Prevention needs to be properly resourced and prioritized as an essential element of the peace and security agenda (Table 1: Opportunities to Strengthen Children, Peace and Security).

Equally essential to effective prevention-oriented approaches is the inclusion of a transformative gendered lens. Peace and security are influenced by inequitable global systems and the failure to recognize these inequities will hinder our collective ability toward preventing violence against children. Preventing violence, including sex and gender-based violence, in fragile and conflict contexts requires a transformative gender analysis to ensure that the diverse experiences of boys, girls and gender minorities are recognized (Table 1: Opportunities to Strengthen Children, Peace and Security).

Participation

Participation is a right in the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, 1989). The voices and perspectives of children, girls, boys and gender minorities, are essential to preventing violence and enhancing child protection (Table 1: Opportunities to Strengthen Children, Peace and Security). Machel (1996) stated:

Children can help. In a world of diversity and disparity, children are a unifying force capable of bringing people to common ethical grounds. Children’s needs and aspirations cut across all ideologies and cultures. The needs of all children are the same: nutritious food, adequate health care, a decent education, shelter and a secure and loving family. Children are both our reason to struggle to eliminate the worst aspects of warfare, and our best hope for succeeding at it (Machel, 1996).

Preventing future escalations of violence, including forced displacement and migration, requires new and innovative strategies toward peace that explore how to enhance prevention and protection mechanisms for and most importantly, with children (Table 1: Opportunities to Strengthen Children, Peace and Security). Aubrey Seader, a young arts-based peacebuilder, recently stated that “kids know the most about what they are going through, and they know the most about their needs.” Children have a role to play as peacebuilders and their participation in the design and implementation of peacebuilding is essential (Baillie Abidi, 2018; O’Neil, 2018; Pruitt, 2020; Toh, 2002).

Violence transformation requires collaboration and participation within a relational framework where everyone is seen and appreciated as connected to one another. Children are integral in a relational framework for peace as their perspectives and lived experiences are both heterogenous and unique in relation to adults. Lederach (2006) argues that a relational approach to conflict or violence transformation requires not just an understanding of how conflict evolves, but an emotional and relational approach to the practice of peacebuilding. A relational and systems approach to violence transformation embraces the importance of relationships as key to finding peaceful solutions together (Lederach, 2006). Understanding possibilities for peace within fragile and conflict environments requires the participation of children as quintessential to building communities where children have opportunity to thrive, learn and participate (Table 1: Opportunities to Strengthen Children, Peace and Security).

In order for protection mechanisms to be effective, girls need to be engaged in the process (Pruitt, 2020; Szabo and Edwards, 2020). A deeper understanding of sex and gender-based structural inequities in fragile and conflict environments is necessary to increase children’s participation in violence transformation (Table 1: Opportunities to Strengthen Children, Peace and Security). Brown et al. (2019) argue: “proactive effort is needed to reach out to, partner with, and listen to the voices of vulnerable and marginalized gender groups with an inclusive and intersectional perspective” (p.2). Children, and particularly girls and gender minority children, have unique needs and capacities which must be considered (Mcguire, 2012; Pruitt, 2020). In this regard, we need a collective transition from a gender unaware approach which lacks appreciation for the unique needs and experiences of different genders, toward a gender transformative approach where gender power dynamics are recognized and challenged (Brown et al., 2019). A gender transformative approach exposes the structural and cultural violence that seeks to sustain inequitable social norms and champions the creation of safe spaces where approaches are “proactively (re)designed” by, for and with girls and gender minorities (Brown et al., 2019). How adults work with children to transform violence is as important as what area of focus is being considered (Lenz, 2017).

Conclusion

Violence disproportionately impacts children in fragile and conflict environments. Given fragility and conflict, including forced displacement and migration, are projected to intensify over the next decade, children will continue to be exposed to multi, intersecting, and emerging forms of violence. The direct manifestations of these emerging tensions are the result of systemic and cultural violence. Thus, in order to break cycles of violence and to disrupt normalizations of violence against children, collaborative attention and preventative action is required.

Protecting the future requires the engagement of young people. Children, boys and girls, have a right to participate in building protective frameworks and peaceful communities. Violence transformation also requires an understanding of the gendered dynamics of children’s experiences in armed conflict and forced displacement. Understanding gendered power dynamics involves recognizing the dynamics between men, women, boys, and girls and the social norms and rules that shape these relations. Gender inequality is systemic and deeply compounds the experiences of girls and gender minority children in conflict and fragile environments. We have much to learn about how gender influences vulnerabilities, resiliencies and protections, especially in relation to the links between children affected by armed conflict and forced displacement.

Our collective ability to protect children, and to prevent violence, relies on a relational framework where the rights and participation of children are recognized as integral to creating sustainable peace. Understanding the experiences of children in fragile and conflict environments from a direct, structural and cultural violence lens provides insight into the systems and normative frameworks that sustain violence against children. In order to achieve and peace and security, a global transformation toward inclusive child protection, holistic violence prevention, and genuine child participation in peace processes must be realized.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

CBA is the sole author of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Achvarina, V., and Reich, S. (2006). No place to hide: refugees, displaced persons, and the recruitment of child soldiers. Int. Secur. 31 (1), 127–164. doi:10.1162/isec.2006.31.1.127

Baillie Abidi, C. (2018). Pedagogies for building cultures of peace: challenging constructions of an enemy. New York, New York: Brill/Sense Publishing, 154.

Brown, S., Budimir, M., Sneddon, A., Lau, D., Shakya, P., and Crawford, U. S. (2019). Gender transformative early warning systems: experiences from Nepal and Peru. Rugby, United Kingdom: Practical Action, 54.

Cazabat, C., Desai, B., and Wesolek, P. (2020). Internal displacement index report 2020. Geneva, SW: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 23.

Chaudhry, L. (2017). “Raising the dead and cultivating resilience,” in Children affected by armed conflict: theory, method, and practice. Editors M. Denov, and B. Akesson (New York, NY: Columbia University Press), 23–42.

Child Soldiers International (2017). “What the girls say: improving practices for the demobilisation and reintegration of girls associated with armed forces and armed groups,” in Democratic republic of Congo. London, United Kingdom: Child Soldiers International, 83.

Clark-Kazak, C. (2012). Challenging some assumptions of “refugee youth”. Forced Migr. Rev. 40. 13–14. https://www.fmreview.org/young-and-out-of-place/clarkkazak.

Cockburn, C. (2013). “Gender relations as causal in militarization and war: a feminist standpoint,” in Making gender, making war: violence, military and peacekeeping practices. Editors A. Kronsell, and E. Svedberg (New York, NY: Routledge), 19–34.

Denov, M., and Akesson, B. (2017). “Approaches to studying children affected by armed conflict: reflections on theory, method and practice,” in Children affected by armed conflict: theory, method, and practice. Editors M. Denov, and B. Akesson New York, NY: Columbia University Press), 1–17.

Denov, M., and Ricard-Guay, A. (2013). Girl soldiers: towards a gendered understanding of wartime recruitment, participation, and demobilisation. Gend. Dev. 21 (3), 473–488. doi:10.1080/13552074.2013.846605

Dona, G., and Veale, A. (2011). Divergent discourses, children and forced migration. J. Ethnic Migrat. Stud. 37 (8), 1273–1289. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2011.590929

Galtung, J. (1996). Peace by peaceful means: peace and conflict, development and civilization. Oslo, Norway: International Peace Research Institute, 280.

Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, peace and peace research. J. Peace Res. 6 (3), 167–191. doi:10.1177/002234336900600301

Gerecke, M. (2010). Explaining sexual violence in conict situations. Gender, war, and militarism: feminist perspectives. Westport, CT: Praeger Security International, 138–156.

Gieseken, H. (2017). The protection of migrants under international humanitarian law. Int. Rev. Red Cross 99 (1), 121–152. doi:10.1017/S1816383118000103

Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack (2015). Safe schools declaration. Geneva, SW: Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack, 38.

Government of Canada (2017). Vancouver principles on the prevention of the recruitment of child soldiers. Ottawa, CA: Government of Canada, 48.

Hettitantri, N., and Hadley, F. (2017). “Young children’s experiences of connectedness and belonging in postconflict Sri Lanka,” in Children affected by armed conflict: theory, method, and practice. Editors M. Denov, and B. Akesson (New York, NY: Columbia University Press), 43–65.

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) (1949). Geneva convention relative to the protection of civilian persons in time of war (fourth geneva convention). Available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b36d2.html (Accessed August 12, 1949).

Johnson, D., and Walsh, A. (2020). Gender, peacekeeping, and child soldiers: training and research in implementation of the vancouver Principles. Allons-Y 4, 51. doi:10.15273/allons-y.v4i0.10083

Johnson, D., Whitman, S., and Sparwosser Soroka, H. (2018). Prevent to protect: early warning, child soldiers, and the case of Syria. Glob. Responsib. Prot. 10, 239–259. doi:10.1163/1875984X-01001012

Kindersley, N., and Rolandsen, O. (2019). Who are the civilians in the wars in South Sudan. Secur. Dialog. 50, 1–15. doi:10.1177/0967010619863262

Lederach, J. P. (2006). Defining conflict transformation. Peacework 33 (368), 26–27. doi:10.1093/0195174542.001.0001

Leibig, A. (2005). Girl child soldiers in Northern Uganda: do current legal frameworks offer sufficient protection. J. Int. Hum. Rights 3, 1–17. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/230965137.pdf.

Lenz, J. (2017). “Armed with resilience: tapping into the experiences and survival skills of formerly abducted girl child soldiers in Northern Uganda,” in Children affected by armed conflict: theory, method, and practice. Editors M. Denov, and B. Akesson (New York, NY: Columbia University Press), 112–128.

Maguire, S. (2012). Putting adolescents and youth at the centre. Forced Migr. Rev. 40, 4–5. https://www.fmreview.org/young-and-out-of-place/maguire.

Mazurana, D., and Carlson, K. (2006). “The girl child and armed conflict: recognizing and addressing grave violations of girl’s human rights,” in Expert group meeting on elimination of all forms of discrimination and violence against the girl child, Florences, Italy, September 25–28, 2006 (Florence, Italy: UN Division for the Advancement of Women). Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/girl-child-and-armed-conflict-recognizing-and-addressing-grave-violations-girls-human (Accessed September, 1 2006).

Montenegro Oporto (2020). Is the gender-based approach helpful? Pending challenges after 25 years of gender equity policies. La Paz, Bolivia: Practical Action, 45.Google Scholar

Navarro Vigil, Y., and Baillie Abidi, C. (2018). “We” the refugees: reflections on refugee labels and identities. Refuge 34 (2), 52–60. doi:10.7202/1055576ar.A

OECD Development Policy Papers (2019). Engaging with men and masculinities in fragile and conflict-affected settings. Available at: https://ideas.repec.org/p/oec/dcdaab/17-en.html (Accessed March 15, 2019).

Onapajo, H. (2020). Children in Boko Haram conflict: the neglected facet of a decade of terror in Nigeria. Afr. Secur. 13 (2), 195–211. doi:10.1080/19392206.2020.1770919

Organization of African Unity (OAU) (1990). African charter on the rights and Welfare of the child. Available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b38c18.html (Accessed July, 11 1990).

O’Connell Davidson, J., and Farrow, C. (2007). Child migration and the construction of vulnerability. Sweden: Save the Children, 69.

O’Neil, S. (2018). “Trajectories of children into and out of non-state armed groups,” in Cradled by conflict: child involvement with armed groups in contemporary conflict. Editors S. O'Neil, and K. van Broeckhoven (New York, NY: United Nations University), 17–36.

Palik, J, Rustad, S. A., and Methi, F. (2020). Conflict trends: a global overview, 1946-2019. Oslo, Norway: PRIO.

Pepper, M. (2017). “Contending with violence and discrimination: using a social exclusion lens to understand the realities of Burmese Muslim refugee children in Thailand,” in Children affected by armed conflict: theory, method, and practice. Editors M. Denov, and B. Akesson (New York, NY: Columbia University Press), 66–88.

Pruitt, L. (2020). Rethinking youth bulge theory in policy and scholarship: incorporating critical gender analysis. Int. Aff. 96 (3), 711–728. doi:10.1093/ia/iiaa012

Security Council (1999). Security Council distr. GENERAL S/RES/1261. Available at: https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/ (Accessed August, 30 1999)

Stromme Sapiezynska, A. E, Knag Fylkesnes, G., Salarkia, K., and Edwards, J. (2020). Stop the war on children 2020: gender matters. London, United Kingdom: Save The Children, 52.

Szabo, G., and Edwards, J. (2020). The global girlhood report 2020: how covid-19 is putting progress in peril. London, United Kingdom: Save The Children, 39.

The Fund for Peace (2020). Fragile states Index annual report 2020. Washington, DC: The Fund for Peace, 123.

Toh, S.-H. (2002). Peace building and peace education: local experiences, global reflections. Prospects 32 (1), 87–93. doi:10.1023/A:1019704712232

UN General Assembly (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Available at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (Accessed December 28, 2020).

UN Security Council (1999). Security Council resolution 1261. Available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3b00f22d10.html (Accessed August 25, 1999).

UN Security Council (2000). Security Council resolution 1325. Available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3b00f4672e.html (Accessed October 30, 2000).

UN Security Council (2008). Security Council resolution 1820. Available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/485bbca72.html (Accessed June 19, 2008).

UN SRSG on Violence Against Children (2020). Six steps to take to end violence against children. Available at: https://violenceagainstchildren.un.org/six_steps_to_end_vac_viewpoint (Accessed October 23, 2014).

United Nations (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. Available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b38f0.html (Accessed November 20, 1989).

United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) (2007). The Paris principles. Principles and guidelines on children associated with armed forces or armed groups. Available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/465198442.html (Accessed February, 2007).

United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (1998). International decade for a culture of peace and non-violence for the children of the world (2001-2010): resolution. Geneva, SW: UN, 52.

UNSG (2020). Children and armed conflict: report of the secretary-general from the united nations. New York, NY: United Nations, 38.

UNSG (2017). Report of the secretary-general on conflict-related sexual violence. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/events/elimination-of-sexual-violence-in-conflict/pdf/1494280398.pdf (Accessed June 03, 2017).

Valencia Arias, A. (2012). From rural Colombia to urban alienation. Forced Migr. Rev. 40, 12. https://www.fmreview.org/young-and-out-of-place/arias.

Wessells, M. (2006). Child soldiers: from violence to protection. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 302.

Whitman, S., and Baillie Abidi, C. (2020). Preventing recruitment to improve protection of children. Allons-Y 4, 24–36. doi:10.15273/allons-y.v4i0.10081

Whitman, S. (2018). “Sexual violence in conflict: understanding the experiences of child soliders,” in Female child soldiering, gender violence, and feminist theologies. Editor S. Willauck (Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan), 27–42.

World Bank Group (2020). Strategy for fragility, conflict and violence 2020-2025. Washington, DC: World Bank, 19.

World Bank (2020). Violence without borders: the internationalization of crime and conflict. Washington, DC: The World Bank, 125.

World Health Organization (2002). World report on violence and health. Geneva, SW: World Health Organization, 22.

Keywords: children affected by armed conflict, girls and boys, forced displacement and migration, sex and gender-based violence, prevention, protection, participation

Citation: Baillie Abidi C (2021) Prevention, Protection and Participation: Children Affected by Armed Conflict. Front. Hum. Dyn 3:624133. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2021.624133

Received: 30 October 2020; Accepted: 15 January 2021;

Published: 25 February 2021.

Edited by:

Evangelia Tastsoglou, Saint Mary’s University, CanadaReviewed by:

Katharine Donato, Georgetown University, United StatesCheran Rudhramoorthy, University of Windsor, Canada

Copyright © 2021 Baillie Abidi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Catherine Baillie Abidi, Y2F0aGVyaW5lQGRhbGxhaXJlaW5zdGl0dXRlLm9yZw==

Catherine Baillie Abidi

Catherine Baillie Abidi