- Department of Sociology and Behavioral Sciences, De La Salle University, Manila, Philippines

This study delves into the experiences of armed conflict and displacement among civilians, who evacuated from the Islamic City of Marawi to nearby cities and municipalities in Northern Mindanao, as well as other parts of the Philippines, to escape the clashes between ISIS-affiliated extremists and security forces in 2017. Drawing upon in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with survivors of armed conflict and duty-bearers, such as government employees, staff of non-government organizations (NGOs), doctors, faculty members and administrators of educational institutions, and volunteers who aided in relief efforts, this research identifies the safety and security issues and vulnerabilities confronting internally displaced people (IDPs) from Marawi City, who are predominantly racial, ethnic, and religious minorities. This study investigates the trends in and risks for gender-based violence among women and girls and men and boys in conflict zones and the challenges in the promotion of their safety and well-being. This paper examines the dynamics of gender-based violence and the respondents’ experiences of private, community-based, and state-sponsored violence in conflict zones and the risk of further violence upon their return to Marawi City. This research also examines the experiences of militarization among IDPs and their views of Martial Law, which was declared in Mindanao on the first day of the Marawi Siege in May 2017. This study illuminates the nuances in the experiences of IDPs living in traditional evacuation centers and alternative home-based evacuation arrangements, their service needs, and the support systems and interventions available to them. The researcher highlights the links between racial, ethnic, gender, and social class inequality in the Philippines and the vulnerability of IDPs, given their dismal living conditions and the absence of normalization in their lives due to the prolonged siege. This paper highlights the intersections between private and public violence, the human rights issues confronting IDPs from Marawi City, and the local and international responses to their situation.

1 Introduction

On 23 May 2017, just 3 days before the beginning of Ramadan, fighting broke out in the Islamic City of Marawi, the capital of Lanao del Sur province, located in the southern Philippines, as the military launched operations against “high value targets” from two local extremist groups, namely the Abu Sayyaf and the Maute group (Dizon, 2017; Maitem, 2017; Marcelo, 2017). The Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG), whose name has been translated to “Father of the Swordsman” and “Bearer of the Sword, is a militant organization fighting for a sovereign Islamic state and based primarily in the neighboring islands of Basilan, Sulu, and Tawi-Tawi, also located in the southern Philippines (Abuza, 2005; Banlaoi, 2006; Banlaoi, 2010; Atkinson, 2012). The group gained notoriety from the mid-1990s onward on account of its involvement in kidnapping, bombing, and extortion activities, all of which have victimized Filipinos and foreign nationals alike (Alberto and Guinto, 2008; BBC News, 2013; Chambers, 2013; Al Jazeera, 2014; Associated Press and Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2014; Fonbuena, 2014; The Straits Times, 2018). Meanwhile, the Maute group, originally named Dawlah Islamiyah (Islamic State), is a recently formed extremist group that claimed responsibility for several kidnapping-for-ransom and bombing incidents in Lanao del Sur from 2015 onward, around the time the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), also known as the Islamic State (IS), started to become more visible in mass media and news sources (Fonbuena, 2017a; Francisco, 2017; Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium. 2017; Unson, 2017). Both Islamist militant organizations have pledged their allegiance to ISIS and, in turn, received support from foreign jihadists.

As the fighting intensified, reports surfaced about the takeover of the Amai Pakpak Medical Center by armed men, who attempted to do the same at Camp Ranaw, a military camp. In addition, the Marawi City Jail and Dansalan College were set on fire (CNN Philippines, 2017; Marcelo, 2017). The turn of events prompted President Rodrigo Duterte to declare Martial Law in Mindanao, citing rebellion as the main reason (Diola, 2017; Fonbuena and Bueza, 2017; PhilStar.com, 2017). Ten days after the conflict started in Marawi, about 175 people, including 120 extremists, 36 soldiers, and 19 civilians, were confirmed dead on account of military-initiated airstrikes intended to attack members of the Maute group, as well as one “friendly fire” or “fog of war” incident (Placido, 2017a; Guardian, 2017; Umel, 2017). These figures have risen since the time of the reports.

The Marawi Siege lasted for 5 months. A ceasefire was declared on 23 October 2017 (Amnesty International, 2017; Bueza, 2017). However, thousands of residents were still not permitted to return to their homes (Aben, 2018; Fonbuena, 2017b). As of 7 June 2017, at least 222,108 people from Marawi had been displaced by the siege, according to estimates of the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD, cited in Rappler.Com, 2017). By mid-June of the same year, the number of displaced people had increased to 324,406 individuals, or 66,738 families, hailing from Marawi City, as well as the nearby municipality of Marantao, located in Lanao del Sur (Placido, 2017b; Viray, 2017). As of August 2017, an estimated 359,680 people had been displaced by the Marawi Siege (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2017).

To avoid being caught in the crossfire, numerous civilians immediately fled Marawi City and evacuated to other cities and municipalities in Northern Mindanao and the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), now known as the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (BARMM); some of the areas to which people relocated included: Iligan City; Cagayan de Oro City; the municipalities of Balo-i and Kauswagan, located in Lanao del Norte province; and the municipalities of Saguiaran, Marantao, and Kapatagan, located in Lanao del Sur province. Some families also transferred to other provinces in Central, South-Central, and Southern Mindanao, such as Bukidnon, Cotabato, and Davao (Estremera, 2017; Gajunera, 2017; Lagsa, 2017; MindaNews, 2017). Braving the distance and the longer journey involved, others, albeit in smaller numbers, relocated to highly urbanized cities in Central and Eastern Visayas, such as Cebu City, Dumaguete City, Tacloban City, and Catbalogan City (SunStar Philippines, 2017a; Bajenting, 2017; SunStar Philippines, 2017b; Featuresdesk, 2017; MindaNews, 2017; Padayhag, 2017). Some headed north and moved to Metro Manila, the capital of the Philippines, and provinces in Central Luzon, such as Pangasinan and Zambales (MindaNews, 2017; Aben, 2018). Government reports indicated that people who had been displaced by the Marawi Siege were scattered across at least 87 evacuation centers in the country, as of July 2017 (Cabato, 2017). This number did not include those who opted for home-based evacuation arrangements, such as renting a room or residing with relatives. Years after the siege, over 120,000 people remain displaced, staying at transitory sites or other temporary housing; many have been unable to return home (Aben, 2018; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR], 2020; Westerman, 2020).

Concerns have surfaced about the socio-economic, health care, and housing needs of the survivors of the Marawi Siege, and the impact of the prolonged siege on their well-being. For instance, internally displaced people (IDPs) in evacuation centers frequently called attention to the insufficient provisions and relief aid from the government (Morella and Agence France-Presse, 2017). As of December 2017, the Department of Health (DOH) reported that 86 people had already died in evacuation centers (Cepeda, 2017). Meanwhile, for those in home-based evacuation centers, living with family members and relatives in cramped spaces was a common concern (Estremera, 2017; Padayhag, 2017). Mental health issues, such as schizophrenia and trauma, have also emerged as an urgent issue (ABS-CBN News, 2017; Cabato, 2017; Nawal, 2017; Santos, 2017). Reports subsequently surfaced about the experience of violence against women and girls, as well as the backlash experienced by survivors, during the prolonged stays of IDPs in evacuation centers (Beltran, 2019).

It is thus crucial to shed light on the narratives of armed conflict and displacement experienced by people who survived the Marawi Siege. It is equally important to delve into the safety and security issues and risks they face as IDPs and their service needs, as well as the available support systems and interventions—or lack thereof—in response to their plight.

This study examines the experiences of armed conflict and displacement among community residents who evacuated from the Islamic City of Marawi to nearby cities and municipalities in Lanao del Norte province, to escape the clashes between security forces and extremist groups in the area. This study also identifies the safety and security issues and vulnerabilities confronting internally displaced people from Marawi City. This research illuminates their heightened risk for gender-based violence and militarization in conflict zones, and their views about Martial Law; this study provides empirical evidence about the experiences and effects of militarization on underrepresented racial, ethnic, and minority groups in conflict zones in the southern Philippines. Finally, this research determines the service needs of IDPs from Marawi City and the support systems and interventions available to them, as well as their unmet needs.

This study seeks to answer the following questions:

(1) What are the socio-demographic characteristics of internally displaced people (IDPs) from Marawi City?

(2) What were their pathways to evacuation?

(3) What are the security and safety issues confronting them?

a. What are their specific experiences of and risks concerning gender-based violence and militarization in a conflict zone?

b. How do they frame the declaration of Martial Law throughout Mindanao?

(4) What are their service needs as internally displaced people?

a. What are the support systems and interventions available to them?

b. What are their unmet needs?

2 Materials and Methods

This study utilized descriptive, qualitative research. A descriptive study was used to explore the experiences and risks of gender-based violence and militarization among different groups of civilians who resided and/or worked in Marawi City prior to the siege. A qualitative approach was utilized to flesh out the nuances in the narratives of armed conflict and displacement among IDPs and their views on the imposition of Martial Law in Mindanao.

Key informant interviews (KIIs) were conducted with individuals who experienced being displaced due to the Marawi Siege and/or acted as duty-bearers in assisting and serving IDPs during or in the aftermath of the Marawi Siege. A total of 29 people participated in the interviews. About 25 informants identified as displaced people, be it in terms of their residence, their place of employment, or both. Of this, 13 were also duty-bearers, in that they provided various services to fellow IDPs despite their own concerns regarding their displacement from their homes and/or workplaces or sources of livelihood. Meanwhile, four informants were exclusively duty-bearers, occupying such positions as directors or consultants of non-government organizations, and administrative staff, who were tasked to oversee the needs of students who evacuated to and temporarily resided in their campus during the weeks after the siege. The interviews examined the informants’ firsthand experiences of displacement and gendered violence during the Marawi Siege, as well as their coping mechanisms and strategies. In the case of duty-bearers, the interviews focused on the interventions and services they provided to individuals who had been displaced by the siege, as well as their experiences. The interviews also delved into the informants’ views on militarization and the imposition of Martial Law in Mindanao (see Supplementary Appendix SA—Key Informant Interview Questions).

Focus group discussions (FGDs) were also conducted with parents and youth, who were residing in traditional evacuation centers and home-based evacuation communities at the time of the research. Separate FGDs were conducted with women/girls and men/boys. A total of 120 IDPs, including 56 youth and 64 parents, participated in the FGDs. Of this, 68 people, including 34 youth and 34 parents, resided in traditional evacuation centers, while 52 people, including 22 youth and 30 parents, resided in home-based evacuation communities. The FGDs examined the informants’ firsthand experiences of displacement due to the siege and their living conditions and service needs while living in traditional or home-based evacuation centers. The FGDs also explored the views and understandings of IDPs on the extent of gender-based violence in conflict zones and the direct experiences of the participants with perpetrators of violent acts, depending on their situation. The FGDs delved into the informants’ views on militarization and the imposition of Martial Law in Mindanao (see Supplementary Appendix SB—Focus Group Discussion Questions).

The researcher also engaged in field observation during her visits to the traditional evacuation center, to home-based evacuation communities, and to the state universities where some informants worked and/or studied. The researcher also observed the security protocols and procedures followed at security checkpoints. Some of her observations are discussed in the results.

Informed consent was sought from and established with all informants. For youth informants who were under 18 at the time of the FGDs, the researcher also required that a proxy consent form be signed by their parent or guardian for them to participate in the FGDs. The names and other identifying information of the informants was kept confidential.

The participants in the KIIs were selected based on the referrals provided by the researcher’s personal contacts from the cities of Marawi and Iligan. The informants were identified through snowball sampling. The researcher first approached informants with whom she had more contact after meeting them in academic conferences, consultancy projects, and community service involving the Muslim community, be it in Metro Manila or in different parts of Mindanao. Additional informants were identified based on the referrals of individuals who participated in the interviews. The majority of the interviews were conducted in locations to which people had evacuated, such as Iligan City and the municipality of Balo-i, Lanao del Norte. One interview took place at Marawi City, which enabled the researcher to observe and witness the educational and work environment and the safety and security issues of people at the height of the siege.

The researcher’s goal was to interview only 20 to 25 informants and thus exceeded her target, for which she stopped conducting interviews upon noticing similar trends in the narratives disclosed by the informants. None of the individuals approached by the researcher declined to participate in the study. That said, the researcher was unable to interview survivors of gender-based violence at the traditional evacuation center. The protocol for conducting interviews with survivors of GBV at the evacuation center involved coordinating with duty-bearers from the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) and identifying informants based on officially reported cases. No cases of gendered violence had been reported yet during the data collection period; this was confirmed by ECOWEB, an NGO that was then serving IDPs at the evacuation center.

The FGD sites were identified in coordination with ECOWEB, an NGO that provided programs and services for IDPs in both traditional and home-based evacuation arrangements. After some interview participants helped connect the researcher with staff from the said NGO, FGDs were scheduled with displaced parents and youth in two of its service areas, including a traditional evacuation center and in a home-based evacuation community in Iligan City. The FGD participants at the home-based evacuation community were identified by the NGO staff deployed in the area. Meanwhile, the FGD participants at the traditional evacuation center were identified by staff from the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) deployed onsite, in coordination with ECOWEB; in addition, ECOWEB staff accompanied the researcher in conducting the FGDs.

The researcher acknowledged the possible impacts of her positionality on her data collection, given her status as a middle-class educated woman working at a university in Metro Manila. At the same time, her cultural background as a woman of Waray and Visayan descent and thus her affiliation with minority ethnolinguistic groups, as well as her ability to speak some languages spoken by Christianized and Islamized ethnic groups in the southern Philippines, helped her build rapport with the informants. Given her support for interfaith dialogue and her involvement with the Muslim community in Manila and the southern Philippines, the informants readily opened up to her once they learned about her previous research on internally displaced persons in another conflict zone in the southern Philippines.

2.1 Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework for this study is based on Juergensmeyer’s (2017) cultural perspective on religious extremism, which asserts that contemporary acts of religious violence are often justified by the historical precedent of religion’s violent past, and stem from a combination of forces that are particular to each moment of history—namely, the cultural contexts of the groups concerned and global social and political changes that characterize the present times. This framework underscores the distinctive world views and moral justifications of religious militant activists, and the ideas and communities of support behind acts of violence, rather than the so-called “terrorists” who commit them (Juergensmeyer, 2017). Using this framework as a point of reference, the researcher examined the social, economic, and political factors in Philippine society that contributed to the Muslim separatist movement and armed conflict in the southern Philippines and the ongoing trends that pose as risk factors in fostering the growth of Islamist militancy and extremist violence in the name of religion in the southern Philippines.

The researcher also utilized Crenshaw’s (1991) intersectionality theory in examining the experiences of displacement and the risk of gender-based violence and militarization among survivors of the Marawi Siege. An intersectional perspective highlights the extent to gender intersects with other markers of difference, such as race and ethnicity, nationality, social class, religion, sexuality, age, and dis/ability. Because people may be privileged on the basis of certain social locating factors yet marginalized on the basis of other statuses, this impacts their lived experiences of gendered violence, their treatment by society, their vulnerability to victimization and violence, and their access to safety nets (Davis, 1983; Davis, 1984; Lerner, 1986; Collins, 1990; Radford and Stanko, 1996; hooks, 2000; Rothenberg, 2006). Their overlapping social positions also affect the responses of the police, the state, professionals, and the voluntary sector (Collins, 1990; Barbee and Little, 1993; Hester et al., 1996; Richie, 1996; Green, 1999; Disch., 2009; Sabo, 2009; United Nations Development Fund for Women [United Nations Development Fund for Women, 2003). Applying intersectionality theory to the situation of the informants in this study, the researcher examined how multiple, interrelated inequalities stemming from their gender, ethnic and religious identity, nationality, social class, and age, among other social locating factors, influenced their experiences of gender-based violence and militarization and their access to resources and support systems in the face of displacement.

2.2 Definition of Terms

It is necessary to define some key terms that are used throughout this article. In brief, gender is defined as the social and cultural construction of behaviors, roles, identities, and statuses associated with masculinity and femininity (Lorber, 2005; West and Zimmerman, 1987). Violence pertains to physical, written, or verbal actions that inflict, threaten, or cause injury that may be physical, psychological, material, or social in nature (Jackman, 2002; World Health Organization, 2006; World Health Organization and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2010). Gender-based violence comprises harmful act/s directed against individuals or groups on the basis of their gender (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights [OHCHR], 2014).

Meanwhile, intersectionality refers to interconnected hierarchies relating to gender, sexuality, social class, and race and ethnicity, among others (Crenshaw, 1991). An intersectional approach considers people’s multifaceted identities and social positions within the matrix of privilege and domination and examines how these shape their lived experiences, social opportunities, and vulnerabilities (Davis, 1983; Collins, 1990; hooks, 2000).

For the purposes of this article, militarism is defined as a perspective that holds that civilian populations depend on—and should therefore submit to—the goals, needs, and culture of its military. Aligned with militarism is the practice of militarization, a methodical process that facilitates people’s and/or entities’ control by the military or reliance on militaristic approaches and views for their well-being (Enloe, 2000).

3 Results

To contextualize the safety and security issues confronting people displaced by the Marawi Siege, it is necessary to examine the deeper roots of the armed conflict in the island group of Mindanao, located in the southern Philippines. This section delves into the underlying social, economic, and political factors leading to the Muslim separatist movement in the Philippines and its implications for the long-standing armed conflict in selected regions of Mindanao. Against this backdrop, the researcher examines the pathways to evacuation of the survivors of the Marawi Siege, their security and safety issues, their views regarding the imposition of Martial Law in Mindanao, and the service needs they face as IDPs.

3.1 Contextualizing Armed Conflict in Mindanao: Muslim Separatism and the Emergence of Armed Conflict and Extremism

The armed conflict in Marawi cannot be isolated from the long-standing complex history of Muslim separatism and armed struggle. This, in turn, stems from deep-seated conflicts between the Moro people and the Philippine colonial and postwar administrations, particularly as it relates to the right to self-determination of the Muslim community. These factors have had implications for the rise of militancy and extremism in the country (David, 2004; Gutierrez and Borras, 2004; Abinales and Amoroso, 2005; Bacani, 2005; Quimpo, 2008).

The literature indicates that the Bangsamoro (“separate nation”) struggle for autonomy, self-determination, and recognition as a citizenry separate from but equal to other Filipinos, is better understood in the context of their Filipino and Islamic heritage, as compared to the ideology of Islam and its general religious and social principles and institutions. Although they constitute the second largest religious community in the Philippines, which is a predominantly Catholic nation due to its history of colonialism, Filipino Muslims make up only 5% of the population, and are concentrated in the southern part of Mindanao, where Islam was first introduced in the late 13th to 15th centuries (Iacovou, 2000; Asian Development Bank, 2002; Bacani, 2005; Ty, 2010). Muslims remained a minority in the Philippines, due to the impediments posed by the Spanish colonization, for which the spread of Islam was halted and confined to southern Mindanao (Lapidus, 1988). For centuries, the Muslims in what is now known as the southern Philippines constituted independent sultanates, fiercely resisting Spanish conquest, as opposed to the leaders of other widely scattered settlements known as barangays (villages), whom the Spaniards cowed into submission by force, persuasion, or gift-giving.

Despite their resistance to the Spanish colonization, the Muslim community gradually fell under the sovereignty of the United States, which subsequently colonized the Philippines (Majul, 1985; Bacani, 2005; McKenna, 2021). Viewing the Muslims as similar to Native Americans, the American colonial government sent some of its best Native American warriors to fight the Muslims. Often, individual Muslim families took it upon themselves to fight American troops. However, since influential sultans and other leaders were given gifts, salaries, and similar incentives, there was no united action against the Americans. The Americans’ superiority in weapons also helped them gain sovereignty over the Muslim groups and incorporate them into the American colony of the Philippines (Majul, 1985). Unlike the Spaniards, the Americans did not encourage Christian-Muslim tensions. American official policy did not support attempts to convert Muslims and thus did not interfere with their religious life (Majul, 1985; McKenna, 2021). Ironically, Muslim leaders generally shied away from the nationalist movement for an independent Philippines. Many who had initially resisted the Americans opted for a government under American “protectors,” framing this setup as preferable to subordination under a government run by Christian Filipinos.

When the United States made the Muslims part of a newly independent Philippines in 1946, many Muslims felt betrayed, as they did not consider themselves Filipinos. They disputed their inclusion into the Philippine nation, especially since they identified with a distinct religious and cultural identity, which they had retained (Iacovou, 2000). As such, most Muslim leaders wished to form an independent state. The impact of long-standing institutionalized discrimination and neglect dating back to the Spanish colonial era was not lost on the Muslim community, which experienced economic setbacks and low literacy levels, compounded by pervasive unemployment and the decline in peace and order (Concepcion et al., 2003; Atkinson, 2012; Bacani, 2005). The tendency of Filipino national leaders in Manila to treating Muslims and their lands in a manner that was reminiscent of the approach utilized by the Spanish and American authorities had done to Filipinos during colonialism—a practice that could be considered internal colonialism—fueled more resentment and animosity. Given the fragmentation of Philippine culture, government programs that were implemented to integrate Muslims into the national fabric and mainstream society were met with corresponding initiatives centered on Islamic revivalism (Majul, 1985; Abinales and Amoroso, 2005).

A national separatist movement among Muslims emerged during the late 1960s. The education of young Muslims in academic institutions in Manila under government scholarships, as well as in Islamic institutions under foreign scholarships in the 1950s and 1960s, helped make this possible, since it fostered changes in Muslims’ awareness of themselves as a people and in their knowledge of Islam. The principal leaders of the movement were young men, who belonged to non-elite Muslim families and who had attended universities in Manila on government scholarships intended to integrate Muslims into the Philippine nation. The leaders eventually gained popular support because established Muslim leaders had failed to effectively prevent the large-scale migration of Christian settlers to Mindanao—a move that was sponsored by the Philippine government and led to the displacement of Muslims and lumads (indigenous people) from their land (Majul, 1985; Abinales and Amoroso, 2005; McKenna, 2021). When the separatist movement gained traction, certain established elites, who had opposed the separatist rebellion and collaborated with the state during the 1960s, now joined the rebel leaders, who had been exiled overseas, and attempted to gain control of the movement (Majul, 1985; Abinales and Amoroso, 2005; Bacani, 2005). Events in the late 1960s and early 1970s further alienated the Muslim community and led some of its members to arm themselves. These included: the Philippine military’s massacre of 30 or so Muslim trainees, who had launched a mutiny in 1968 on the island of Jabidah, due to unpaid services while training for covert operations to invade Sabah; conflicts and clashes between Muslims and Christians; and the gradual loss of Muslim communal lands to Christian settlers (Iacovou, 2000; Concepcion et al., 2003; HURIGHTS Osaka, 2008; Uy, 2008; Gloria, 2018).

Following the September 1972 declaration of Martial Law by then-President Ferdinand E. Marcos, the authoritarian government attempted to disarm Muslims, who feared retaliation by the military and attacks by armed groups consisting of Christians. This, in turn, led to open rebellion. At the forefront of armed struggle was the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), whose founders were among those Muslim youth trained abroad and whose formation was partly motivated by the Jabidah massacre of 1968, in which only one trainee survived (May 1992; Abinales and Amoroso, 2005; Uy, 2008; McKenna, 2021). Led by Nur Misuari, the MNLF originally fought for Mindanao independence under a secular regime, on the grounds that it was only through a free and independent state that Muslims could free themselves from corrupt leaders and fully implement Islamic institutions (May 1992; Mercado, 1992). In the 1970s, however, the Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC) in Libya, which had served as the patron of the MNLF, persuaded Misuari to negotiate and settle for autonomy, as opposed to its initial separatist agenda. This resulted in the 1976 Tripoli Agreement between the Marcos government and the MNLF, which called a ceasefire and the granting of autonomy—that is, based on a Philippine constitutional framework—to 13 out of 23 provinces in Mindanao, the Sulu Archipelago, and Palawan, where large numbers of Muslims lived (Mastura, 1992; May 1992; Shahar, 2000; McKenna, 2021).

However, the Muslim community complained that the peace agreement, which called for the establishment of a Muslim Autonomous Region, was never genuinely implemented by the Marcos administration (Mercado, 1992; Concepcion et al., 2003). Clashes recurred before the end of 1977, with the rebellion continuing throughout the latter half of the Marcos regime and even during the subsequent presidential administrations (May 1992; Abinales and Amoroso, 2005; Abinales, 2008). The Aquino administration resumed peace talks with the MNLF and, in conjunction with the 1986 Constitution, mandated the creation of an autonomous region in Muslim Mindanao (Madale, 1992; Mastura, 1992; May 1992). Yet during the referendum conducted in November 1989, very few provinces, namely Maguindanao, Lanao del Sur, Basilan, Sulu, and Tawi-Tawi, voted in favor of their inclusion in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao; the remaining provinces, as indicated in the Tripoli Agreement, opted out of autonomy (Mercado, 1992). The subsequent administration of President Fidel Ramos continued peace negotiations with the MNLF, referring to the terms of the Tripoli Agreement, and the enactment of the Final Peace Agreement (May 1992; Abinales and Amoroso, 2005). In 1996, the MNLF signed a peace agreement with the government and made concessions in favor of the autonomy of selected provinces in Mindanao (McKenna, 1998; Abinales and Amoroso, 2005; Abinales, 2008; McKenna, 2021).

Due to more militant demands, splinter groups subsequently emerged within the Muslim separatist movement. One such group was the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), established in 1978 by Salamat Hashim, who served as the Vice-Chairman of the MNLF Central Committee and sought to take over the organization due to disagreements with Misuari’s leadership and negotiations with the government in favor of autonomy, as opposed to the original bid for independence, for Muslim regions in the Philippines. After being expelled by Misuari’s loyal followers, Hashim thus declared independence and transferred his base of operations to Cairo, Egypt (McKenna, 1998; Yegar, 2002; Abinales and Amoroso, 2005).

The Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) emerged as another breakaway faction in 1991, although other sources claim it was established several years prior, 5 following the disagreement of young Islamist cadres with its predecessors in the separatist movement (McKenna, 1998; Banlaoi, 2010; BBC News, 2012). The Maute group was established as another splinter group in 2012 (Francisco, 2017; Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium. 2017; Unson, 2017). Its activities are also rooted in criminality and extortion activities, similar to those of the ASG (Hincks, 2017; Jones, 2017; Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium. 2017; Unson, 2017). Sources reveal that Marawi was being eyed as a potential wilaya (province) of ISIS, but differ in their assessment of whether Isnilon Hapilon, who was the head of the Abu Sayyaf group for a time and pledged support to ISIS in 2014, would have been the governor of the said province, had he not been killed (Hincks, 2017; The Manila Times, 2017). The emergence of these groups illustrate the trend towards the Islamization of the Moro identity, which marks a critical shift within the Muslim community in the Philippines, and the formalization of the already existing Islamist trend within some sub-groups within the MNLF and the MILF. The nationalist essence of the earlier separatist groups was incorporated into the struggles of the Abu Sayyaf and Maute groups for the Islamization of the Moro community, contributing to the operational transformation of the Muslim separatist movement (McKenna, 1998; Iacovou, 2000; Banlaoi, 2010; Hart, 2019).

The historical experiences of social, economic, and political oppression at the expense of the Muslim/Moro community in the Philippines continues to have long-term consequences for the growth of militancy and the intensification of armed conflict in selected regions of Mindanao. Despite the peace agreements formed between former separatist groups and the Philippine government, there remains dissatisfaction regarding the implementation of social policies and interventions to promote autonomy and stability in regions with predominantly Muslim populations (Abinales and Quimpo, 2008; Hutchcroft, 2016). Structural inequality has led to the intensification of armed conflict in selected regions of Mindanao, in that militant and Islamist groups, which emerged as breakaway factions of former separatist groups (Lara and Schoofs, 2013; National Law Enforcement Coordinating Committee Subcomittee on Organized Crime, 2015; National Law Enforcement Coordinating Committee Subcomittee on Organized Crime, 2016), promote violent extremism in the name of religion, as a response to deep-seated inequities and long-standing tensions between Muslim ethnic groups and the government in a predominantly Christian society.

These complex social and historical forces that contributed to separatism and armed conflict in the southern Philippines inform the experiences of people displaced by the conflict in Marawi, in an effort to avoid the clashes between the Philippine military and the Maute group and ISIS forces. This will be discussed in more detail in the succeeding sections.

3.2 Demographic Profile of the Informants

The majority (22 out of 29) of the interview participants were women; a small number (n = 7) were men. The informants were aged 22–65 years old; the median age was 36.

In terms of civil status, 16 informants identified as single, 12 were married, and one was divorced.1 Less than half of the informants (n = 11) had children; the average number of children was two. Two of the women informants were pregnant at the time of the interviews.

With respect to their religion, 19 informants identified as Muslims, while 10 informants identified as Christians. In terms of their racial and ethnic background, they belonged to minority communities, including groups affiliated with both Islam and Christianity.2 The majority (n = 15) identified as Maranao, an Islamized ethnic group, whose ancestors had historically embraced Islam. Meanwhile, nine informants belonged to ethnolinguistic groups whose ancestors had historically converted to Christianity, such as: Visayan (n = 8) and Waray (n = 1). Five informants were of mixed descent. Of this, four traced their roots to both Islamized and Christianized ethnic/ethnolinguistic groups, in that one was of Maranao and Tagalog descent, another of Maranao and Visayan descent, and two of Maranao and Waray descent; meanwhile, one identified with two Christianized ethnolinguistic groups, being of Ilocano and Visayan descent (see Table 1—Racial and Ethnic Background of Interview Participants).

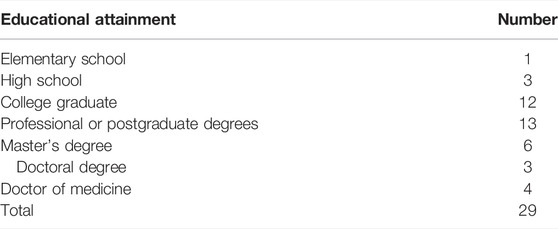

The educational attainment of the interview participants was diverse (see Table 2—Educational Attainment of Interview Participants). The majority (n = 13) had completed professional or postgraduate degrees; of this, four had obtained a medical degree and were licensed physicians, while nine had obtained master’s degrees or doctorates in such fields as biology, education, English language studies, Filipino or Philippine studies, psychology, and sociology. In addition, 12 informants were college graduates. Three informants had a high school education, and one informant had an elementary school education.

Meanwhile, the FGD participants were predominantly Muslims, of Maranao descent. A smaller number identified as Christians, of Visayan descent. They were predominantly from low-income and working-class backgrounds. With the exception of some youth and young adults who were either studying or pursuing professional degrees, the majority of the FGD participants had limited educational attainment.

3.3 Pathways to Evacuation and Concerns of IDPs From Marawi

The interviews and FGDs revealed that there were two common pathways to evacuation among people displaced by the Marawi Siege, namely: traditional evacuation centers and home-based evacuation arrangements. The former involved being registered on the official list of the DSWD pertaining to IDPs residing in evacuation centers. The latter involved residing with in-laws, relatives, and/or friends in other cities and municipalities, as well as renting an apartment or a hotel room, albeit with many other relatives, depending on the informants’ situation.

3.3.1 Traditional Evacuation Centers: Experiences of IDPs

None of the interview participants resided in a traditional evacuation center at the time of the data collection for this research. The researcher was unable to conduct one-on-one interviews at the evacuation center with individuals who had survived gender-based violence due to the siege. The protocol for conducting interviews with IDPs who identified as GBV survivors involved coordinating with duty-bearers at the evacuation center and identifying informants based on officially reported cases. No cases of gendered violence at the evacuation center had been reported yet, as of the data collection period; this was confirmed by staff of the NGO that offered programs and services for IDPs at the facility. That said, some of the IDPs residing at the traditional evacuation center disclosed their own accounts of gendered violence, particularly that perpetuated by extremist fighters at the height of the siege and by duty-bearers such as military and police forces during the implementation of tighter security restrictions and protocols as a result of the declaration of Martial Law in Mindanao; this will be discussed in more detail in the succeeding sections.

As for the FGD participants at the traditional evacuation center, they revealed that they, along with their family members, ended up at the facility under varied circumstances. More than two-thirds of them stated that they had been referred to the center by duty-bearers from the DSWD, Red Cross, or other deputized agencies with which they had inquired, and by civilians who had seen them around after they had evacuated to Iligan City—an intense, harrowing journey that compelled them to travel through different municipalities, to the extent of walking long distances, in most cases, if they were unable to get a ride, especially during the mass exodus of people from Marawi when the siege broke out. A young adult man acknowledged the assistance of some civilians in the barangay (village) of Tambacan in Iligan: “There were people in Tambacan, and they brought us here.” Meanwhile, a middle-aged Muslim woman of Maranao descent highlighted the assistance of some residents of Iligan despite their differences in terms of religion: “We walked toward the plaza. We were told by some kind-hearted Christians, “Go to the evacuation center.” This is what they referred us to.”

Two FGD participants at the traditional evacuation center admitted that they had initially considered alternative evacuation arrangements. One of the mothers stated that she and her family wanted to stay at a state university in Iligan that was serving IDPs, but learned that it only accepted students, and ended up at the traditional evacuation center after they happened to pass by the facility. Another mother mentioned that she and her family members first went to a home-based evacuation community that turned out to be full, for which they looked for another place to stay.

In some cases, the evacuation center became an ad-hoc meeting place for family members. For instance, a young Maranao man, who took part in the FGD with male youth at the traditional evacuation center, disclosed that he and his family members had gotten separated while fleeing the conflict in Marawi, and only reunited at the facility. A Visayan adolescent girl also related how she was then working Camp Ranaw when the siege broke out and stayed with her neighbor, until she was brought to the evacuation center roughly a month after her parents’ arrival in Iligan City.

3.3.2 Home-Based Evacuation Communities: Experiences of IDPs

Nearly two-thirds of the interview participants (18 people) had been displaced by the Marawi Siege and were residing in home-based evacuation communities at the time of the data collection. The only exceptions to this trend were the duty-bearers (4 people) who were living and working in Iligan and were not directly impacted nor economically displaced as a result of the conflict.

About 12 out of the 18 interview participants had evacuated to Iligan City, which is about 45 min to an hour away from Marawi City. They had experienced either the loss of or heavy damage to their homes due to air strikes, or were compelled to leave the cottages, apartments, or rooms they rented when the siege broke out. At the time of the interviews, three informants were renting an apartment with their family members, in-laws, and/or relatives in Iligan. Meanwhile, two informants were living in the offices in which they worked. Furthermore, seven informants were living with relatives, friends, churchmates, or colleagues in the area.

By and large, the informants who identified as home-based IDPs in Iligan expressed their gratitude for the generosity of their in-laws, relatives, friends, and members of other significant networks, who had taken them in without hesitation. Yet nearly half of them disclosed the tradeoffs of their living situation. Aside from acknowledging the limitations brought about by their status as “just living with others,” these informants also commonly asserted: “It is different living in your own house.” One informant, who was pregnant, shared that three-fourths of her family’s home in Marawi had been destroyed—shortly after its renovation, at that. While she remained very grateful for the support of her in-laws, with whom she and her immediate family members resided, she admitted that she and her young children had to adjust to living with limited resources—a far cry from their more comfortable lifestyle prior to the siege. She disclosed that they had to get used to wearing the same clothing repeatedly or managing with just one pair of shoes or even just slippers, and that her younger children still could not grasp the reality that their home had been bombed about 2 weeks after the conflict escalated.

Another informant also acknowledged that she and her young children, including an infant, had to make many sacrifices on account of their living situation, as they shared an apartment with at least 15 other relatives. Because she was employed, in that she worked as a guidance counsellor in a school and attended to traumatized children in evacuation centers, while her other relatives did not have steady work, she was expected to take care of many of their basic needs and cover the bulk of their living expenses.

An informant, whose family had lost their home due to the air strikes in Marawi, recognized that they were fortunate to find an apartment to rent immediately—a far cry from the experiences of her fellow Muslim IDPs. Yet she had to take on additional family-related responsibilities, while her parents and her siblings were still adjusting to the impact of the siege on their living situation.

The researcher was also able to interview five members of a multi-generational family residing in Balo-i, Lanao del Norte province, which is about a 30-min drive from Marawi City. These informants, who were related to one another as immediate, blended, and extended family members, were home-based evacuees, living near a traditional evacuation center. At the time of the interviews, their household consisted of an elderly married couple, two of the mother’s daughters from her previous marriage to her late first husband, and the husband and four children of the younger of the two sisters. Their neighborhood in Marawi was part of an area known as the Ground Zero of the siege; as recalled by the older of the two sisters: “Only a wall separated us from the conflict. There were so many dead bodies on the streets.” They had to walk a considerable distance before they were able to obtain a ride to Balo-i by contracting with motorcycle drivers who agreed to drive them for a fee. Their home was heavily damaged by the air strikes, as well as the clearing operations conducted by the military and the police.

The older sister, who was then 33 years old, had just been released from prison, where she spent nearly a decade for drug charges, less than 2 months before the siege; she had made the trip all the way from Mandaluyong City, a city in Metro Manila where the main penitentiary for women was located, only to come home to a conflict zone. Given her limited resources after being incarcerated for drug charges for nearly a decade and after being displaced by the Marawi Siege, she was as vulnerable and as indigent as she could get. She had lost most of her belongings, such as beaded handicrafts and clothes that she had purchased and saved while serving her sentence, with the intention of selling them to augment her income upon returning to free society. She admitted that she briefly considered staying at the nearby traditional evacuation center, but expressed her fears about the rapid spread of diseases and her concerns about the health and safety of her 63-year-old mother, her 65-year-old step-father, and her four young nieces and nephew, who were between the ages of five to 11 years old at the time of the interviews. The younger sister, who was then 29 years old and 5 months pregnant, and her husband, who was 44 years old, also decided to avoid the traditional evacuation center, so as not to jeopardize the health of their young children and their unborn child. Thus, their entire family opted for home-based evacuation and shared a single room in the compound owned by the family of origin of the younger sister’s husband.

About seven informants did not need housing arrangements, since they resided in other municipalities or cities in Northern Mindanao or had family members living in these areas, and/or resided in a different house, apartment, or room in such locations as Iligan City, Cagayan de Oro City, Balo-i, Lanao del Norte, and other nearby cities or municipalities prior to the Marawi Siege. For them, economic displacement was a more significant issue, in that they faced additional constraints and safety risks in reporting to work in Marawi. One informant, who resided in Balo-i, but worked in Iligan, mentioned that she and her husband served as hosts to IDPs and that their displaced relatives still relied on them as a support system.

As for the home-based IDPs who took part in the FGDs with the parents and the youth, more than two-thirds of them disclosed that they ended up in the home-based evacuation community in Iligan through their ties to members of their significant networks, such as immediate and extended family members and friends living in the area. The fathers commonly stated that they were living with relatives. One of the mothers similarly asserted: “Wherever your relatives are, that’s where you live.” At least seven people, primarily adolescent and young adult women, also stated that they were renting a house or room in the community. One of the considerations that emerged was the receptivity of the community toward IDPs. Two Muslim-Maranao mothers acknowledged that the community opened its doors to evacuees, although the residents were predominantly Christian, for which they did not experience discrimination, as compared to Muslim IDPs residing in other areas with predominantly Christian residents. One of the Maranao fathers also recognized the empathy of the residents, who had ended up in the community after losing their homes to due to Typhoon Sendong (international name: Washi), a strong typhoon that struck several areas in Northern Mindanao, particularly the cities of Iligan, Cagayan de Oro, in December 2011. He claimed: “The way they treat us is fine. They experienced Sendong,” for which he concluded that the community residents could thus relate to the ordeal of displacement.

That said, two of the mothers who participated in the FGD with home-based IDPs disclosed that other community residents subsequently considered or ended up living at a nearby gym that served as an evacuation center. One of the mothers disclosed that she and her family initially considered residing there, but were unable to do so because it was full. In addition, another mother disclosed during the e FGD that she, like some residents, transferred from one place to another.

3.3.3 Impact of Cultural Norms on the Living Situation of IDPs

The accounts of IDPs and duty-bearers alike revealed the role of ethnic cultural norms, as well as the kinship obligations that come with it, in determining the residence of IDPs in traditional evacuation center or home-based evacuation arrangements. Most of the informants are of Maranao descent or identify as “culturally Maranao” in the sense of having assimilated to the Maranao way of life. They emphasized the belief and practice of marhatabat (honor or pride) in their ethnic group and its implications for their expected responses to displacement due to the Marawi Siege. The need to maintain honor and dignity—not only on an individual level, but also and more importantly on a familial or clan-based level—is of utmost importance, even in the face of conflict. This informed the decision of many Maranao IDPs to opt for home-based evacuation arrangements and to pursue such measures as living with relatives and other significant networks, renting a hotel room, a house, or an apartment, and other similar arrangements, if at all possible. It is also customary for Maranao people to take in any relatives who need a place to stay, as part of kinship obligations and the broader cultural practice of protecting the honor of one’s family and clan. As such, in the Maranao community, it is seen as shameful to let one’s relatives live in an evacuation center, as it is an affront to the cultural value of marhatabat, which is not limited to the individual and extends to their family or clan. One-third (five) of the interviewees of Maranao descent emphasized this cultural value. In the words of one informant: “If you have a relative living in an evacuation center, you are expected to take them in. Otherwise, people look at you as having failed in your obligations as a relative.”

More than one-third of the informants confirmed that the observance of marhatabat in the Maranao community accounted for the comparatively lower numbers of residents in traditional evacuation centers, as compared to home-based evacuation communities. In a similar vein, more than half of the duty-bearers confirmed during the interviews that those residing in traditional evacuation centers had nowhere to go, lacked support systems, and/or were more indigent than those in home-based evacuation arrangements. In any case, the informants asserted that the comparatively lower numbers of people who were staying in traditional evacuation centers after fleeing the conflict in Marawi—in contrast to the congested evacuation centers in other conflict zones in Mindanao—did not mean that IDPs from Marawi did not need as much assistance from the government and other entities providing services to IDPs. They reiterated that cultural norms and dynamics in the Maranao community informed the living situation of people displaced by the Marawi Siege.

3.4 Security and Safety Issues Encountered by IDPs From Marawi: Gender-Based Violence

The narratives of all the informants, who had been displaced from their homes and/or places of employment due to the Marawi Siege, illuminated common themes in the security and safety issues they encountered while evacuating to avoid the crossfire between the military and extremist forces, and while dealing with prolonged displacement. Gender-based violence was a primary issue, with implications for their security and safety throughout the siege.

As displaced people, the informants were vulnerable to public acts of violence at the height of the siege. They related their firsthand experiences of gendered violence—or the threat thereof—in the context of public settings, in the form of community-based violence and state-sponsored violence in times of armed conflict. The perpetrators included extremist fighters belonging to the Maute group and ISIS, military and law enforcement personnel, and in some cases, community residents. In contrast, acts of violence that occurred within the private sphere, such as personal violence, were not discussed as much during the interviews and FGDs; this is not to say that IDPs discounted this possibility, as some of them recognized and hinted that stressors, such as the ordeal of displacement, limited socioeconomic resources, the lack of privacy, and the risks associated with people’s living conditions, could trigger conflicts between intimate partners, family members, and other significant networks.

The vulnerability of the IDPs to gender-based violence was amplified by structural inequalities affecting ethnic and religious minority groups in an underserved region in the southern Philippines that had historically received limited public attention and institutional support. Their access to resources and services varied according to their racial, ethnic, and religious identity and social class, relative to their educational attainment and occupation; those from low-income or working-class communities were especially vulnerable, given their limited support systems and safety nets. Intersectionality was apparent in their experiences of gender-based violence, mainly in public settings. Their accounts reveal their experiences of and risk for violence on account of the links between their gender and other social locating factors, such as their race and ethnicity, religion, social class, and age, in the context of a postcolonial nation where the dominant culture often framed them as the “other.”

3.4.1 Women’s and Girls’ Experiences of and Risks for Gendered Violence

The women and girl informants narrated multiple experiences of and risks for gender-based violence during the Marawi Siege. The intersection of their gender with other social locating factors, such as their religion, ethnic background, social class, and nationality, shaped their specific experiences of and risks for gendered violence. The violence they encountered—or the threat thereof—could be categorized as state-sponsored violence, defined as violence condoned by or perpetuated by the state wherever it occurs, and community-based violence, defined as violence that is entrenched in communities.

The violence of armed conflict was a primary form of gendered violence endured by the women and girl informants in this study. The accounts of all the informants who were displaced by the siege illustrate this reality. The majority of the women and girls, who participated in the interviews and the FGDs, were living and/or worked in Marawi. Some were given only 5 hours to evacuate their communities. Others left their homes 3 days later, when the security forces instructed them to evacuate before they would start using tear gas to ward off their adversaries. For those who resided at the area known as the Ground Zero of the siege, it was common to be trapped there for several days, until they managed to leave. Walking long distances, if only to evacuate to safety, was common those who did not have their own vehicles, for which it can be inferred that those from low-income communities were hit hard.

About one-third—that is, 8 out of 21—of the women interviewees and more than half of the participants in the FGDs with mothers and female youth, had encountered ISIS fighters, whom they often described as young men and even teenagers. One of the mothers at the traditional evacuation center related how she and her companions had seen ISIS fighters riding the armored car of a government-owned bank, from which the vehicle had presumably been hijacked. A teenage girl at the evacuation center recalled: “They (ISIS members) looked at people so fiercely. They were about 15–17 years old.” Meanwhile, an adolescent girl at the home-based evacuation community related how ISIS fighters “tried to escape using our place,” from which it can be inferred that insurgents attempted to use their residence and/or community to elude the military forces.

A middle-aged Muslim woman informant, who was of Maranao and Visayan descent and was married, with six children, recounted during the interview that how they were stopped by ISIS fighters at gunpoint while they were evacuating; her husband, a police officer, was not with them. She had to recite Islamic teachings to avoid being shot. She and her children were ordered to lie face-down on the ground, and that one soldier was shot several feet from them. She still attended to gendered caregiving responsibilities throughout their ordeal, and helped her children, especially the younger ones, stay calm in the face of grave danger. She also experienced being harassed and verbally abused at gunpoint by military personnel when they were rescued at a gasoline station where she and others had hidden. She reported that some Islamophobic soldiers singled her out and demeaned her by referring to her attire as her “costume,” simply because she was wearing a long, black dress, consistent with the practice of Muslim women who had completed hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca).

Meanwhile, a Christian woman informant of Visayan descent, who taught at a state university in Marawi and lived in a dormitory on campus, shared that she and fellow residents pooled their funds and rented two jeepneys, which were typically used as a form of public transportation, in order to travel to Iligan City. She mentioned that two Muslim-Maranao residents at their dormitory had planned to join them, but prioritized the evacuation of Christian residents such as herself, since they were among primary targets of extremist forces on account of their religion. She and her companions wore long-sleeved clothing and kombong (local parlance for head scarf), so as to blend in with Muslimah (Muslim women) residents and thus protect themselves while evacuating. Her experience illustrates her firsthand encounters with multiple threats and vulnerabilities, particularly the danger of being discovered and attacked by extremist forces, the risk of getting hit by stray bullets during the clashes between insurgents and the military, and the strain of evacuation with minimal food and water and a long commute to contend with—at least five times the usual travel time, at that—due to the heavy traffic caused by the mass exodus from Marawi. All these security and safety issues constituted forms of state-sponsored gendered violence to which she was exposed.

Some women experienced secondary violence or the threat thereof. Their exposure to and risk of violence was linked to their ties with family members, relatives, and other significant networks. Four interview participants and at least three FGD participants—all women—disclosed how they were instrumental in securing the safety of their family members, relatives, colleagues, and even acquaintances, particularly those who belonged to vulnerable population groups, such as children, the elderly, and specific groups of men, such as those who could be held hostage and/or forced to fight alongside insurgents, and those affiliated with law enforcement. This shows that some of the security and safety risks confronting women and the responsibilities they undertake in times of armed conflict, overlap with internalized expectations surrounding gendered relational behaviors, identities, and caretaking roles in the context of familial and work-related responsibilities, regardless of their civil status.

During the FGD with mothers at the traditional evacuation center, a Maranao woman related how she immediately attended to her children to ensure their safety when they evacuated to Iligan. As she stated: “I prioritized my children. Material possessions can be replaced, but that is not the case with children. We were not able to bring anything because we thought the conflict would only last for two to 3 days.”

A middle-aged Maranao woman, who worked as an administrator at a state university, related how she and her husband, who also worked there, were stranded on campus when the siege broke out. She immediately called her daughters and instructed them to hide and protect her sons that night. When she and her husband went to rescue their children and her elderly mother from their home in Marawi, they saw ISIS fighters patrolling their street. She cautioned her husband against leaving their vehicle and guarded her teenage sons, in particular, because of the high risk of them being taken and forced to join insurgents because of their gender and age. She also looked out for her daughters when ISIS fighters stopped their vehicle to tell them to fix their hijab.

Meanwhile, a Maranao woman informant, who was single and in her mid-30s and worked for the city government of Marawi, related how she had to ensure the safety of all employees in the office, including the mayor, who was a highly valued target, and her older sister, who was part of his staff and was 8 months pregnant. Some ISIS fighters—one of whom turned out to be a distant relative—while she was driving home the following day. She also had to oversee the immediate evacuation of her family members to Iligan.

A Maranao woman informant, who was a home-based IDP and pregnant at the time of the FGD, shared that she had to outwit ISIS members, who had surrounded her home, by distracting them, luring them to her store, and offering them provisions, despite the dangers that she herself faced, if only to ensure that her husband would not be taken and forced to fight with them. Her response illustrates her gendered relational responsibilities as a woman and a wife, even during her close encounters with extremists:

“My husband was inside the house. He could not go out—he is a motorcycle driver for hire. Members of ISIS said he was their enemy. So he asked us to rescue him. Even if I was pregnant, I went with them. If my husband would die, I would die with him, too…We opened the store, so we wouldn’t be noticed…We got whatever we could get…Some ISIS members asked for what we had in stock. Others asked, do you have socks? I gave them our stocks (of provisions) with my eyes closed. They might kill us.

It is said they kill the men who do not join them. When we left, I said (to her husband), “I am more of a man than you are.” ISIS fighters told us not to go back anymore.”

A 30-year-old Maranao woman informant, who also resided at the home-based evacuation community, likewise shared during the FGD that she helped outwit and disarm an ISIS member, who had escaped and ended up at their family compound, located at the “war zone,” a term often used by IDPs to refer to the Ground Zero of the siege. Despite being trapped in their community for 3 days at the height of the siege, with no food, electricity, and water, she and her companions strategically negotiated with the said escapee. She revealed: “ISIS members pass through our area itself. Some make the rounds there. There was even an ISIS member who had escaped and passed through our house. When he was about to enter our compound, we blocked him. They (others in their family compound) scared him off by saying there were soldiers in there. He stripped off his clothes and laid down his weapons.”

Meanwhile, a Maranao woman informant, who participated in the FGD with women IDPs, claimed that she and her companions helped hide three police officers at the height of the siege. As she recalled: “We hid three police officers and made them wear the clothing of tabligh (Muslim men who serve as missionaries).” It can be inferred that they were exposed to armed conflict and extremist violence, but still helped rescue other vulnerable civilians.

In a similar vein, a Maranao woman informant in her early 30s, who worked as a doctor at the Amai Pakpak Medical Center, disclosed the risks that she and her colleagues faced when insurgents entered the hospital when the conflict broke out. A team of doctors, nurses, and other medical staff were ordered to perform surgery on an injured ISIS fighter, which readily posed security risks. Given the risk of extremist violence against men, she and her women colleagues were also instructed to hide all the men working at the hospital, particularly those who identified as Christians and/or members of Christianized ethnolinguistic groups, due to the risk of attacks confronting the latter on account of the intersection of their gender, religion, and racial and ethnic background.

The narratives of IDPs from Marawi also reveal certain acts that constitute community-based violence. At least six women informants—including those from Islamized and Christianized ethnic/ethnolinguistic groups—disclosed during the interviews that the shared spaces of women and men in traditional evacuation centers are a taboo in the Maranao community, which is highly protective of women and girls. Some of them noted that such living conditions could leave women and girls vulnerable to sexual harassment and other forms of victimization on account of their gender. A report that subsequently surfaced regarding the experience of sexual violence of a displaced young woman at an evacuation center in the aftermath of the Marawi siege only confirms that the informants’ concerns are justified (Beltran, 2019).

None of the informants disclosed incidents of domestic violence. One factor to consider is the role of cultural dynamics that impact people’s inclination to disclose or withhold information regarding such experiences. At least four interview participants mentioned that Maranao culture is generally averse toward the reporting cases of domestic violence to outsiders, given the preference for settling marital disputes internally and limiting interventions to the families of the spouses. It can be inferred that these trends most likely informed the non-disclosure of incidents of personal violence.

This is not to say that acts of personal violence, such as that perpetuated by intimate partners did not occur during or in the aftermath of the Marawi Siege. Indeed, some NGO staff members disclosed that reports of domestic violence experienced by some IDPs at the traditional evacuation center were being investigated at the time of the data collection. They likewise revealed that the incidences of intimate partner violence, which victimized women, were often related to the economic difficulties of IDPs and the frustrations resulting from the inability of couples to engage in sexual activity due to the lack of privacy in the evacuation center.

3.4.2 Men’s Experiences of and Risks for Gendered Violence

The men informants who took part in this study also shared their experiences of and risks for gender-based violence, as revealed in the interviews and FGDs. The risk of gendered violence while evacuating from the site/s of the conflict and other forms of violence while in displacement were dominant themes in their narratives.

During the FGDs, the majority of the men informants, be these parents or youth, articulated the multiple security and safety risks they encountered while evacuating. A Maranao adolescent boy, who participated in the FGD with IDP youth at the traditional evacuation center, related how the clashes between the insurgents and the military left him stranded at the provincial capitol of Lanao del Sur, which is located at the Marawi City center and therefore comprised the Ground Zero of the siege. He consequently had to walk for long distances to get away from the conflict. As he recalled: “We were trapped in the Capitol for 3 days. Then we passed through a small opening. Then we walked to Iligan.”

Violence perpetuated by extremist groups was a common security and safety risk among the men informants and thus a form of gendered violence against them. Similar to the situation of the women informants, the men who took part in this study had their share of encounters with insurgents. Two out of four of the men interviewees, who were living and/or working in Marawi before the siege, and more than half of the fathers and the teenage boys and young men, who took part in the FGDs, had also encountered ISIS fighters. A young Maranao man, who also a home-based evacuee, shared that he was among those who had received anonymous text messages that informed them of the arrival of insurgents in their community in Marawi: “We once received text messages stating that they were coming here. The Maranao people started panicking.” In a similar vein, a middle-aged Maranao man, who participated in the FGD for home-based IDP fathers in Iligan, claimed that ISIS fighters arrived in the different barangays after conflict first erupted in the barangay of Basak Malutlut in Marawi. Another home-based IDP father, who also self-identified as Maranao, mentioned that extremists infiltrated communities in that they “blended in with those wearing tabligh attire,” Meanwhile, a Maranao young man at the home-based evacuation community described his firsthand encounters with ISIS and the restrictions enforced: “ISIS members told me that cigarettes and shorts were not allowed.”

The men informants’ narratives illustrate that abduction, recruitment, forced membership, and murder are among the security and safety risks that men encountered at the hands of extremist fighters and thus constitute specific forms of gendered violence against them in times of armed conflict. During the interviews and the FGDs. some women and girl informants confirmed that these trends affected displaced men.

The majority of the teenage boys and young men, who participated in the FGDs at the home-based evacuation community, disclosed that ISIS fighters were actively recruiting members, and that men were at a greater risk of being taken. At the same time, they differed in their accounts regarding the use of force by ISIS. One informant claimed: “They didn’t threaten us. They would just talk to you.” Yet another young man reported: “Members of ISIS went from one house to another and asked about who among the men could fight (note: along with them). I decided to evacuate my nephews first.” Another young man at the same home-based evacuation community, disclosed that ISIS also recruited detainees in exchange for their release: “Those in jail were told, “Join us, so you can be free.””

The home-based IDP family residing in Balo-i, Lanao del Norte province, experienced the abduction of one of its male members. According to the older of the two sisters who were interviewed, men—even those who identified as Maranao—were vulnerable to being taken and forced to fight alongside the rebels. She reported that ISIS fighters took her brother-in-law shortly after the siege broke out; fortunately, the mayor negotiated on his behalf, for which her brother-in-law was released. A woman who participated in the FGD with mothers at the home-based evacuation community, also shared that her cousin, a Muslim-Maranao man who worked in law enforcement, was held hostage by ISIS, but was released. She recalled: “He was told, “So you’re a police officer, after all,” and made to strip off his uniform. Only his boxer shorts and undershirt were left. Their firearms were taken from them.”

The risk of murders and attacks also impacted men during the Marawi Siege. At least two-thirds of the interview participants and more than half of the participants in the FGDs with the youth and parents claimed that men were at a greater risk of being killed as a result of the conflict. One of the mothers, who also took part in the FGD with home-based IDPs, noted “According to news reports, most of those who die are men, really.” Another mother added: “They really kill the Christians. Some are Maranao, too.”

The accounts of some informants also illustrate that Christian men, seen as the religious “other” by extremists, were at a greater risk of being killed on account of the links between their gender and religion. For instance, a teenage boy, who participated in the FGD with male youth at the traditional evacuation center, disclosed that some men working as security guards in their community sought refuge with them when the Marawi Siege broke out. As he recalled: “There were some security guards at the pawnshop who ran to us. They were Christians.”

The experience of a young Muslim-Maranao man, who was in his early 20s and had just relocated to the traditional evacuation center in Iligan, likewise attests to the risk of murder among Christian men. He once worked as a private security guard in the nearby municipality of Marantao and was among the last to evacuate after the Marawi Siege broke out. He disclosed this colleague and best friend, who belonged to an ethnolinguistic group affiliated with Christianity, was shot dead by ISIS fighters—right next to him, at that—for being unable to recite the Sura-al-Fatihah, a central Islamic prayer. He recalled: “I told them to take me, too, but they refused. I wish I could forget about that experience.” His story confirms the vulnerability of certain groups of men to violence in times of armed conflict due to the links between their gender and religion.

The interviews and FGDs also revealed common themes in men’s gendered safety and security issues, such as harassment and intimidation by military personnel at checkpoints and punitive treatment by police officers in the event of legal infractions. Muslim men or men belonging to Islamized ethnic groups, particularly those wearing clothing that represented their religious identity, such as that associated with tabligh, were at a greater risk for mistreatment, which illustrates their vulnerability due to the intersection of their gender, religion, and race and ethnicity, in the context of a postcolonial nation that has historically treated Muslims as the “other.” For instance, a middle-aged Maranao man, who participated in the FGD with fathers at the home-based evacuation community, related his experience of being profiled at the onset of the siege: “I was made to stand beside the pictures of those who were “wanted” (note: members of the Maute group). This was on the first day (of the conflict).” In a similar vein, the 65-year-old Maranao patriarch of the home-based IDP family that was interviewed, disclosed that he was stopped and harassed by military personnel on the suspicion of being an ISIS supporter, simply for wearing the traditional clothing of Muslims. It can be inferred that the link between their gender, race and ethnicity, and religion led both men to be singled out for arbitrary reasons.

During the FGDs with male youth at both the traditional evacuation center and the home-based evacuation community, at least six teenage boys/young adult men also shared that they experienced maltreatment on the part of law enforcement personnel. These informants were arrested for missing curfew and humiliated by having their names published or having them walk around the town proper and/or hit by the police before being made to spend the night in a holding cell. They disclosed that there was a Php 300 fine for those who missed their curfew. They were also ordered to engage in community service before being released.

For instance, two adolescent men at the evacuation center related how they and their two friends had run-ins with law enforcement upon missing their curfew and were thus detained, although they were not made to pay the fine imposed on people for missing the curfew. As one of the youth informants revealed:

“We were caught smoking. We were not able to go inside by 8p.m. (note: the time of the curfew). We got caught and spent the night in a police precinct. That prison was so small and there were 17 of us. Someone spilled water on us…We were made to clean up. There was a fine, but we didn’t pay.”