- 1Gender and Women’s Health Unit, Centre for Health Equity, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia

- 2Institute for Research into Superdiversity, Department of Social Policy, Sociology and Criminology, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom

- 3Sociology Department, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

- 4Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey

While much attention is focused on rape as a weapon of war, evidence shows that forced migrant women and girls face increased risks of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV) both during and following forced displacement. In this paper, we argue that gendered forms of structural and symbolic violence enable and compound the harms caused by interpersonal SGBV against forced migrant women and girls. These forms of violence are encountered in multiple contexts, including conflict and post-conflict settings, countries of refuge, and following resettlement. This paper illustrates the consequences of resultant cumulative harms for individuals and communities, and highlights the importance of considering these multiple, intersecting harms for policy and practice.

Introduction

In 2019 the scale of forced displacement reached its highest level globally since records began, with 79.5 million people forcibly displaced, of whom 29.6 million were classified as refugees (UNHCR, 2020). Doctors of the World, the Women’s Refugee Commission (WRC) and many other international organisations have highlighted high levels of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV) experienced by forced migrants during recent conflicts, throughout forced migrant’s flight, in temporary camps, in immigration detention centres, and upon resettlement (WRC, 2016). The full extent of SGBV is unknown however, with incidence under-reported because of a lack of opportunity to report, victim’s lack of confidence in reporting, and fear of punishment due to associated stigma and shame (UN Women, 2013). The experience of SGBV is mentally and physically debilitating and can prevent forced migrants from rebuilding their lives, potentially further exacerbating the socio-economic inequalities that characterise forced migrant’s lives in countries of reception.

Women and girl forced migrants are the most common victims of SGBV but risk of human rights violations, including SGBV, is heightened at the intersections of prejudice and discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity, race, ethnicity, religion, economic status, and disability (Simon-Butler and McSherry, 2018). Forced migrant women with a disability, for example, can be targeted by perpetrators of sexual violence, on the basis that they may be unable to report the violence; lesbian and transgender forced migrant women can be subjected to “corrective rape” (Pittaway and Bartolomei, 2018). Gay, bisexual and transgender men can experience homophobic violence (Moore and Barner, 2017), and heterosexual men and boys may also be subject to sexual violence during forced migration. Some scholars suggest this form of violence aims to “feminise”, and therefore subordinate, not only the sex of male victims, but also the religious, and/or political identity to which the victim belongs while masculinising, and therefore superordinating, both the sex and the ethnic, religious, and/or political identity to which the perpetrator belongs (Skjelsbaek, 2001; Marsh et al., 2006; Freedman, 2007). These forms of gendered violence are important to consider and warrant further dedicated research. This paper focuses on SGBV perpetrated against forced migrant women and girls due to the especially high prevalence of this violence and the greater availability of evidence about SGBV experienced by forced migrant women (Schmiechen, 2003; Freedman, 2007; Freedman, 2016; Ozcurumez et al., 2018).

In this paper, we respond to the question: how do experiences of gendered structural and symbolic violence enable, and compound harms caused by interpersonal SGBV perpetrated against forced migrant women and girls? We explore the nature and consequences of violence in the contexts of conflict, transit, countries of refuge, and resettlement, and demonstrate how different forms of violence interact and accumulate for forced migrant women. We begin by outlining the various contexts in which violence against forced migrant women is perpetrated, and then define the different types of violence being examined. We then consider the nature of violence experienced by women within different contexts of forced migration. We have drawn on interviews conducted with survivors who participated in the Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in the Refugee Crisis: From Displacement to Arrival (SEREDA) project. SEREDA is a four-country study being conducted in the United Kingdom, Turkey, Sweden and Australia investigating forced migrant’s experiences of sexual and gender-based violence. Although SEREDA participants were located in four countries when interviewed, their collective experiences span many more geographical and geopolitical contexts. To supplement these examples, we have also drawn on other literature concerning SGBV in forced migration to illustrate a full picture of SGBV in a global context. We conclude by arguing that examination of SGBV and forced migration must account for different forms, contexts, and interactions of violence in order to fully understand and respond to the multiple forms of violence perpetrated against forced migrant women.

Contexts of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence

Armed conflicts are often prolonged, spread across more than one region, and can involve millions of people on the move. Mass movements of people entail complex journeys and challenges in offering protection to forced migrants (Hynes and Cardozo, 2000; Keygnaert et al., 2012; Simon-Butler and McSherry, 2018). Since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011, for example, over 5.6 million people have been forced to leave their homes and seek safety in neighbouring countries—Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq – and beyond (Ozcurumez et al., 2018).

Forced migrant experiences are complex and experiences of SGBV can be conceptualised as ongoing and multifaceted experiences of trauma. Such an approach is pertinent given Wasco’s (2003) argument that the harm done by sexual assault cannot be understood as a single trauma. Menjivar and Perreira (2019) also argue for the importance of looking at cumulative disadvantage across the migration process, while Cockburn (2019) contends that the line between peace and war is blurred. The continuity between relations and events occurring in peace and war, or pre-war and post-war deems a sharp distinction between these phases meaningless and, Cockburn (2019) argues, gendered phenomena, including gendered violence, persist from one to the next. While, the process of seeking refuge is not linear, and divisions between ‘stages’ of a migration journey are not clean-cut (Gerard and Pickering, 2014), this article is presented under the headings of pre-conflict, conflict, transit, refuge, and resettlement, as a heuristic for organising the material that is included.

The compounding impact of multiple experiences of violence in different forced migrant contexts has been under-researched and under-documented (Ozcurumez et al., 2018). To date, the literature on SGBV associated with forced displacement has predominantly focused on specific acts of interpersonal violence such as rape, domestic violence, human trafficking, and early and forced marriage (Hynes and Cardozo, 2000; Keygnaert et al., 2012; Simon-Butler and McSherry, 2018). Furthermore, much research to date has tended to focus on risks of violence during specific stages of migration processes (Goessmann et al., 2019; Jarallah & Baxter, 2019; Vaughan et al., 2015; Wachter et al., 2017; Wirtz et al., 2014). For example, women’s experiences of war-related rape have been documented in a great many conflicts, including Civil wars in Liberia (Swiss et al., 1998), Syria (Freedman, 2007; Allsopp, 2017), and the DRC (Christian et al., 2011; Freedman, 2016). However, Lokot (2019) and Meger (2016) warn of the over-simplification, sensationalisation, and fetishisation of rape during conflict. Depicting sexual violence during conflict as a discrete phenomenon can render rape outside of war less provocative or ‘apolitical’; push other gendered forms of violence experienced during conflict to the margins; and negate pre-displacement experiences of SGBV. Furthermore, Krause (2015, 2017) argues for recognition of a continuum of violence across settings from conflict to encampment, including during flight, making visible the complex and compounding risks faced by forced migrant women. This paper builds on the concept of a violence continuum by examining the intersecting and cumulative nature of different forms of violence.

Conceptual Framework: Interpersonal, Structural and Symbolic Forms of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence

SGBV is an umbrella term used to cover a spectrum of violence involving a gendered element (Hynes and Cardozo, 2000; Simon-Butler and McSherry, 2018). In this paper, we characterise violence as having three distinct, albeit interlinked, forms: Interpersonal, structural, and symbolic (Montesanti, 2015).

We define interpersonal violence as violence that is perpetrated by individuals; it includes violence perpetrated against family members and intimates, as well as community violence (Montesanti, 2015; World Health Organisation, 2019). Violence perpetrated against family members and intimates includes child maltreatment, intimate partner violence, and elder abuse, while community violence includes assault by strangers and violence against unrelated individuals in public and private settings (Montesanti, 2015; World Health Organisation, 2019). Interpersonal SGBV can be perpetrated against forced migrant women and girls by a range of actors including, but not limited to, government forces, militia, smugglers, traffickers, allies, other forced migrants, members of host communities, friends, family members, and partners and husbands within and between all contexts of forced migration (Canning, 2017).

We define structural violence as forms of violence that are built into the fabric of society and create and maintain inequalities within and between social groups, including on the basis of gender, sexuality, ethnicity, religion, ability, socioeconomic position, and immigration status (Montesanti and Thurston, 2015). Structural violence arises because of differential access to power, and leads to differential access to information, resources, voice, agency, and representation (Jones, 2000; Jones, 2001). It is upheld by institutions (including government and government institutions) through custom, practice, and law, and manifests in access to both material conditions and power (Jones, 2000). Structural violence is often enacted against forced migrants through immigration and asylum policy (Phillimore and Cheung, 2021). It also occurs when institutions fail to respond to forced migrant women’s needs; disrespect and mistreat them; and uphold and reproduce discriminatory sexist, patriarchal and misogynistic norms that sustain female subordination (Marsh et al., 2006; Menendez-Menendez, 2014; Montesanti and Thurston, 2015; Ozcurumez et al., 2018; Ozcurumez et al., 2020).

The Term Symbolic Violence was coined by Pierre Bourdieu (1979) to describe non-physical violence that manifests in power differentials between social groups. We use the term symbolic violence to describe ideologies, words, behaviours and non-verbal communications that produce, reproduce, and legitimise power relations in everyday practices (Montesanti and Thurston, 2015; Thapar-Bjorkert et al., 2016). Symbolic violence underpins views of men’s dominance as part of the “natural order”, and conditions that enable prejudice and discrimination and other more visible forms of violence. Moreover, victims can internalise these power relations and hierarchies, both accepting their domination as legitimate, and normalising the violence being perpetrated against them (Thapar-Bjorkert et al., 2016).

Structural, Symbolic and Interpersonal Violence are dynamically linked through social, political and economic processes that shape the violence that occurs in both private and public spaces and violence that may be perpetrated by different individuals, groups, and institutions (Krause, 2017). For women, or any marginalised group, structural and symbolic violence can create conditions in which interpersonal violence is enabled, or in which women are unable to access the violence prevention and response services they need (Montesanti, 2015; Montesanti and Thurston, 2015). Furthermore, understanding the interconnectedness of different forms of violence is vital to developing more holistic interventions to prevent and respond to violence (Grych and Swan, 2012). Focusing predominantly on interpersonal violence and, by extension, dichotomised notions of “victims” and “perpetrators” locates the problem of violence within individuals who are deemed good or bad, violent or non-violent. In reality, individuals co-construct their behaviours and thoughts under the influence of a range of contextual factors that operate over time and across geographical location (Montesanti and Thurston, 2015; Abo-Zena, 2017). Our conceptualisation of violence thus locates SGBV as underpinned by patriarchy which is conceptualised as being made up of structural and ideological elements. Structurally, the patriarchy organises social institutions and social relationships in a hierarchy that enables men to maintain positions of power and privilege. Ideologically, patriarchy provides ways of creating acceptance of such subordination of women. Understanding SGBV in the context of patriarchal system therefore focuses on social, cultural, political and economic forces (DeKeserdy, 2021).

Methods

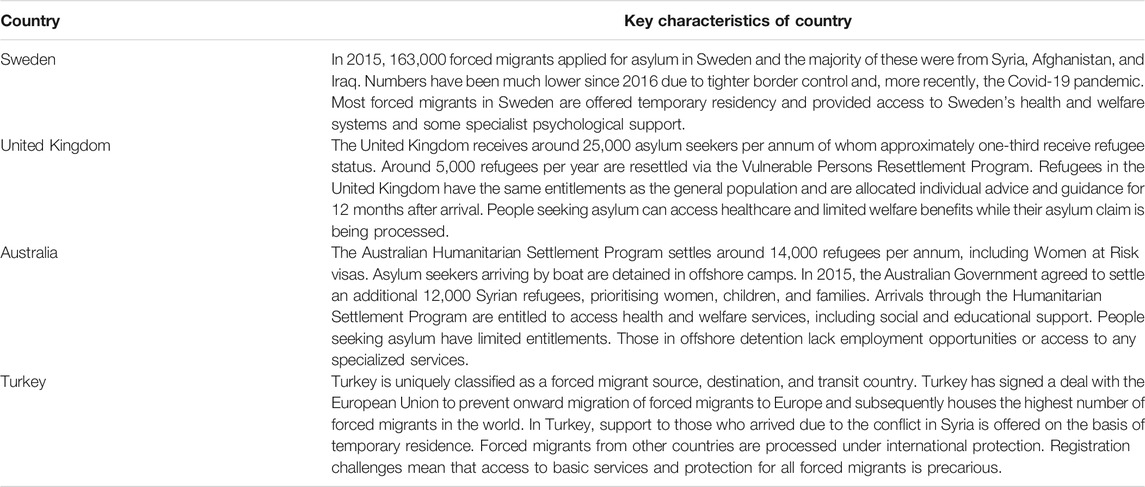

This paper draws upon published research and data collected as part of the SEREDA project, a multi-country study investigating forced migrant’s experiences of SGBV from displacement through to resettlement. Table 1 describes the key characteristics of each of the countries in which data collection for the SEREDA project occurred.

The SEREDA Project adopted a broad definition of forced migrant to include those with official refugee status, those seeking asylum and with recognition of refugee status, and those who migrated through other channels but were nonetheless fleeing from violence or persecution. Some of our participants migrated from countries undergoing conflict through family reunion process, as spouses or prospective spouses. This variability in migration status has important impacts in terms of eligibility for a range of services and rights to access employment and education following arrival in countries of refuge or resettlement.

The SEREDA project undertook interviews conducted with both service providers and with forced migrants (not all of whom were women). The interviews were conducted in Australia, Turkey, Sweden, and the United Kingdom and included interviews with 141 individuals who had undergone forced displacement and were survivors of SGBV. Survivors interviewed represent 22 countries of origin from the MENA region or Sub-Saharan Africa and include ethnic and religious minorities within those countries. 115 of the survivors interviewed are women aged between 20 and 80 years of age. The majority of participants were recruited into the study through partner organisations in each of the respective countries. The women recruited were clients of these services and had disclosed experiences of SGBV to these services. Employers at these services (e.g., social workers) were briefed on the study and provided with information sheets on the study to pass on to the potential participants. Participants who agreed to be contacted by a SEREDA team member subsequently filled out a “Permission to Pass on Contact Details form” which was passed onto the relevant SEREDA team member. Team members then contacted participants to provide them more information on the study. In addition, the study put out a call for respondents via social media, in a range of languages and used a snowballing approach to reach out to further respondents. Verbal consent to participate was provided by participants over the phone, and an interview time and location was determined. Before the interview, the SEREDA team member repeated study information and provided participants with a Plain Language Statement and written consent form. Participants were provided with an opportunity to ask any additional questions before signing the consent form. Verbal consent to record the interview was sought separately. Translated copies of the Information sheets, Plain Language Statements, and Consent Forms were provided when relevant. Interviews were conducted in English, Arabic or Turkish by three members of the SEREDA team, including Author 1. Two of the three team members are native Arabic speakers, and third is a native Turkish speaker. In addition, two of the three team members have lived experience of conflict in the MENA region which contributed to reducing the power hierarchies between the research interviewers and the research participants. We also worked with local community groups who were able to introduce us to trusted interpreters with experiences of working with social researchers who enabled us to interview in other languages including French, Kurdish and Tigrinya. Where relevant, interviews were translated to English by the interviewer for analysis. All interviews were transcribed, and then analysed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Institutional ethics approval was received in each country and included an extensive safety protocol to ensure that participation did not endanger women and that all participants were provided with information about accessing support. A coding framework was developed collaboratively by the study team, based on patterns identified in the empirical material, in which structural and symbolic violence was a recurring theme. The quotes included in this paper were selected due to their illustration of interplay between gendered structural and symbolic violence and interpersonal SGBV. All the women’s names have been changed in this paper, and women were assigned pseudonyms. We have also drawn on additional published evidence on SGBV to supplement our empirical data, and provide a fuller, more holistic picture of SGBV across a greater range of settings in which forced migration occurs.

Findings and Discussion

Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Pre-conflict

Societies and Countries that have experienced political violence or armed conflict tend to show “warning signs” pre-conflict, including economic distress, militarization, and shifts in ideology (Cockburn, 2019). Feminist analysis of pre-conflict settings have highlighted increased economic distress, which is gendered in nature, including high unemployment rates among male breadwinners; increased risk of young men being coerced into crime or militarism; and reduction in welfare spending (Vickers and Yarrow, 1991). There is also often an increase in militarisation in countries and societies that later experience political violence or conflict and can include a growing or strengthened relationship between political elites and military elites. Indeed, during the SEREDA project, a forced migrant woman interviewed in the United Kingdom spoke about her experience of rape by a man in the Algerian military just before conflict erupted. She reflects on the stigma and shame that she experienced following the incident. Her experiences illustrates how symbolic violence deems men (particularly those in the military) “untouchable” while underpinning stigma and shame experienced by victims of rape:

“I was raped in Algeria. I was raped by an animal-like man. I know his name and I know his family. He doesn’t live far away from us. The problem is he has a high rank in the army and so does his father. Everyone there is scared of them because they have high status and they’ve got money. He raped me but when I told my mom, her first reaction was to slap me saying that I brought disgrace to the family. He was the one who raped me, but I became a disgrace to the family. I wanted to report him to the police, but his family have connections, and my family refused that I go speak to his family. My older brother actually talked to him and told him, “Let’s end this issue before it gets big. We don’t mind if you want to marry her.” At that moment I was like. . . a monster has raped me, but they will force me to marry him! When I refused that, my brother locked me up in my room”.

– Samia (Algerian Woman Interviewed in London, United Kingdom)

Cockburn (2019) argues that the third warning sign of impending armed conflict or political violence is a shift towards divisive discourse that is accompanied by increased patriarchal ideology that deepens the differentiation of men and women, masculinity and femininity. This shift occurs in preparation for a narrative (and by extension a reality) where men fight, and women support them. Thus, gender inequality can be exacerbated in pre-conflict settings, and SGBV risks can be heightened during subsequent forced migrant contexts.

Sexual and Gender-Based Violence During Conflict

Worldwide, most forced migrants flee their homes due to violent conflicts in their country of origin (Krause, 2017) and conflict-related sexual violence is increasingly recognised as a contributor to women’s forced migration (Canning, 2017). Risks of SGBV in conflict settings are driven by a combination of gender inequities and interpersonal and structural factors, such as the breakdown of legal structures, social networks, and livelihood options (McAlpine et al., 2016).

Wartime acts of violence are socially and politically constituted. Militaries are patriarchal institutions and frequently employ the systematic and widespread use of different forms of SGBV as a strategic weapon of war (Sokoloff and Dupont, 2005; Krause, 2017). For example, rape during war can occur as a “routine recreational activity” where local women in war-zones are represented as “sexually available” to soldiers (Ozcurumez et al., 2018). Rape during war is also a way in which women’s biological reproductive capacity can be controlled and, through forced pregnancy, can induce women to bear the children of their enemies as a form of domination and control (Freedman, 2007). During the SEREDA project, a forced migrant woman interviewed in Australia reflects on her experience being kidnapped during the Syrian conflict:

“In Syria, we were really exposed to kidnapping and we were exposed to explosions, looting of houses … I was an Arabic teacher and they used to target teachers because they didn’t want schools to stay open, so I was kidnapped three times and I escaped … When we were kidnapped, me and a few other women, there was a pregnant woman with us, she had a miscarriage due to the trauma and fear, so they let her out … The first time I was kidnapped, I would swear to them that I was Christian, and they wouldn’t believe me. They said, ‘if you’re Christian, recite the Lord’s Prayer’ and I wouldn’t be able to say it. From the trauma and fear, I could no longer recite it”.

– Rita (Syrian Woman Interviewed in Melbourne, Australia).

In some cases, early and forced marriage can be seen as a coping and survival strategy for families facing financial hardship due to conflict (Sharma et al., 2020). Conflict can result in increased barriers to education, separation of families, and increased poverty which leads to changes in relationships and marital practices including early marriages (Schlecht et al., 2013). Families may organise early or forced marriages, perceiving that marriage will protect women and girls from the increased risk of sexual violence during conflict (McAlpine et al., 2016). Early marriage can be also perceived to be a means of keeping daughters safe and protecting them from poverty and sexual violence in countries of refuge (Abraham and Tastsoglou, 2016). In some cases, early marriage can also be adopted as a weapon of war (Sharma et al., 2020). Armed groups may force girls to marry combatants, and abduct girls for this purpose (Human Rights Watch, 2012).

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) increases in conflict settings, with pre-existing attitudes supportive of violence against women interacting with war-related psychopathology (Wirtz et al., 2014; World Health Organisation, 2014; Goessmann et al., 2019). Crisis conditions also exacerbate existing hardships which creates opportunities for sex traffickers to profit by exploiting desperation (McAlpine et al., 2016).

Descriptions of SGBV in conflict often ignore however, the global structures of power and inequality that drive violence in countries of conflict. Such representations may reduce SGBV to a problem of the “global south”, which racialises violence against women and renders the violence that occurs in “developed” societies as invisible (Olivius, 2017; Ozcurumez et al., 2018). Racism and Islamophobia can lead to men in conflict zones being represented in global discourse as “violent”, and to diagnoses of violence against women as an expression of religion or culture (Olivius, 2017). This representation not only adopts a colonial, white gaze, in which forced migrants are represented as “other”, but shifts the focus to individual actors, deflecting attention from the patriarchal systems in which violence is taking place (Olivius, 2017; Ozcurumez et al., 2018). Such focus on specific perpetrators across the forced migrant journey masks the intersecting and compounding nature of violence against forced migrant women across temporal and geographical contexts. Racist, Xenophobic, and Islamophobic representations simultaneously exacerbate and normalise the structural and symbolic violence enacted in and by high income countries against forced migrants.

Sexual and Gender-Based Violence During Transit

Individuals are confronted with continuous threats of violence when fleeing conflict and insecurity to seek safety, and the impacts of resultant harms are often gendered (Krause, 2017). Forced migrants can be forced to undertake transactional sex to “pay” for travel documents, border access, or the journey itself (Yazid and Natania, 2017). Threats of SGBV accompany flight by land or sea. For example, multiple studies have described risks for Sudanese women fleeing across the Sahara to Uganda, including being forced to sell sex as currency after being detained and prevented from continuing their journey unless they accede to demands for payment (Nagai et al., 2008; Gerard and Pickering, 2014; Krause, 2015). When travelling by boat, women are frequently given the most precarious positions and may be subject to burns due to being too close to the engine (Gerard and Pickering, 2014). The risks associated with boat travel are determined by the material and social resources that women have access to, highlighting the role that structural inequality plays in exacerbating risks for women (Gerard and Pickering, 2014). A forced migrant woman interviewed in the United Kingdom for the SEREDA project reflects on her experience seeking asylum by boat, emphasising her experience of gendered vulnerability:

“My poor sister was the one who helped me collect the money. She was working, and she also sold all her jewellery and gave me the money, though she needed it. I took the money, and I went with them [smugglers]. We were very crowded on the boat. There was a woman with a baby with us. The baby was tiny; you could barely notice him. He was very small. The rest were men, a lot of men … We spent almost three days at sea. It was an extremely difficult experience. [The journey and being one of the only women on the boat] was difficult for both my mental and physical health”

– Samia (Algerian Woman Interviewed in London, United Kingdom)

For forced migrants attempting to seek safety in the “West”, the Politicisation and Securitisation of borders further enables and exacerbates violence. Borders constitute a mechanism through which State power is performed, exercising control over who enters the country and on what terms (Pickering and Cochrane, 2012). Such bordering has contributed to a political rhetoric in which nations must be “protected” from those deemed “undesirable” and civil and military practices have been introduced that classify and exclude forced migrants and irregular migrants through policies of detention, deterrence, and expulsion (Pickering and Cochrane, 2012). We show in Table 1 that is considerable variation in asylum and refugee arrivals and policy across the four different comparison countries. However, in each country, policy, legislation and anti-immigration ideology intersect in a way that exacerbates the risks and consequences of SGBV. For example, women interviewed for the SEREDA project in the United Kingdom described borders as the most dangerous places because that was where their ‘illegality’ was most visible. Securitised borders increase the likelihood that forced migrants will need to turn to people smugglers or corrupt officials to seek safety, in turn increasing the likelihood that women will be subjected to sexual violence while attempting to cross borders (Freedman, 2016).

Perhaps the most visible example of state violence against forced migrants in transit is the detention of people seeking asylum. In Australia, legislative changes that occurred in 2001 resulted in people arriving by boat being redirected to offshore detention in Papua New Guinea (on the island province Manus) or Nauru (Phillips, 2012). Although onshore, British and American detention centres also place individuals in a transitory state of limbo that prevents or prolongs their settlement. The indefinite nature of detention combined with conditions of overcrowding, inadequate healthcare, and ill-treatment, contributes to physical and mental suffering for people seeking asylum (Gammeltoft-Hansen and Tan, 2017). Detention centres are also plagued with reports of violence, including SGBV (Canning, 2017). Some of the negative consequences of detention are gendered. A 2019 report found that immigration detention processes in the United States routinely inflict abuse and neglect on women and girls. The report illustrated a lack of access to maternal healthcare and reproductive autonomy for women in detention, as well as complaints of sexual abuse and exploitation (Ellman, 2019). Women interviewed in the United Kingdom for SEREDA, also reported SGBV in detention.

The Burden of proof on people seeking asylum to prove they were the victim of persecution in order to access a positive asylum claim, comprises a form of structural violence. Associated procedures place women under pressure to disclose experiences of SGBV in psychologically unsafe environments where they feel shame, are frequently accused of lying, and then offered no psychological support in the aftermath of extremely stressful interviews (Keygnaert et al., 2012). A woman we interviewed in the United Kingdom reflects on the experience of being interviewed while in detention, despite not being physically or mentally well enough to be interviewed, nor being given the appropriate health or psychosocial support:

“I wasn’t prepared for [the interview], I was in detention, I was not mentally fit to talk about my life, I always gave them what I can give them, and they want this huge, like everything about you, and I didn’t understand that. So, I wasn’t prepared for it mentally and I was sick. I had no Haemoglobin. I had endometriosis, I had a lot of issues and I was on my period then, but I felt I could go for the interview I felt that I was strong, but mentally I wasn’t fit, looking back now. I have been told that they were supposed to spot [that I was unwell], but they didn’t … I think they should’ve given me an opportunity when my mind, when I’m settled when I gone for a bit of therapy, I think they should’ve put that into consideration. They should’ve spotted it that I was vulnerable which they spotted but they just refused to be human at that point”

– Chioma (Nigerian Woman living in London but interviewed remotely via Zoom)

Furthermore, the uncertainty associated with waiting for a decision is acknowledged to generate psycho-social distress (Grace et al., 2018). A recent analysis of the United Kingdom’s Survey of New Refugees found that women were more likely than men to still be experiencing the psychological effects of uncertainty 21 months after receiving a positive decision (Phillimore and Cheung, 2021).

Securitised borders mean that marriage is increasingly seen as a pathway to migration and safety due to partner visas being easier to obtain than humanitarian ones in many settings. In Australia, prospective marriage visas enable an Australian citizen or permanent resident to sponsor someone from overseas to come to Australia. However, a woman on a prospective marriage visa who experiences IPV can only access Family Violence Provisions that enable the spouses of Australians access to a pathway to residency after she marries her sponsor (Vaughan et al., 2016; Vaughan et al., 2015). A forced migrant woman interviewed in Turkey reflects on the pressure she felt to stay in a violent relationship out of fear that leaving would negatively impact upon her resettlement prospects:

“A lot of forced migrants are afraid that it [reporting IPV] will affect their resettlement application file. If there’s violence, she can’t go to the third country [because of him]”

– Mariam (Afghan Woman Interviewed in Gaziantep, Turkey).

A similar situation was reported in the United Kingdom, where a woman’s asylum status is dependent on that of her husband, effectively forcing her to stay in a violent relationship or be forced “underground”. Thus, structural violence—securitisation of borders and precarious visa status—can mean that women are pressured to stay in violent relationships and are ineligible to access the welfare services that would enable them to leave, forcing women into a state of desperation, destitution, illegality, or dependency.

Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in Countries of Refuge

With permanent resettlement offered to only a small proportion of the world’s forced migrants, many seek safety—and end up living for many years—in a country neighbouring the conflict they have fled. In both camps and urban settings, they are at high risk of all forms of SGBV (Charles and Denman, 2013; Krause, 2015; Yasmine and Moughalian, 2016).

Forced migrant women are known to experience higher rates of IPV in countries of refuge than they did pre-conflict (UN Women, 2014; Women’s Refugee Commission, 2014). IPV perpetrated against women can take a number of different forms including interfering with women’s physical mobility; access to food and/or shelter; decisions regarding contraceptive choices; or access to economic resources (Yasmine and Moughalian, 2016; Krause, 2017). Social Isolation, financial stress, discrimination, restrictions, and lack of privacy may contribute to tensions within households and may exacerbate men’s use of violence (Women’s Refugee Commission, 2014). Another factor that can contribute to increased risk of IPV in countries of refuge is changing gender relations. As previously described, structural and symbolic gendered violence underpin gender roles in which women are frequently subordinate. In countries of refuge, women can gain responsibilities that they did not have in their country of origin, such as providing financially for their families. At the same time, men can lose their traditional status due to economic, social and political limitations, and legal restrictions. These changed relations can contribute to violent acts against women as men attempt to reassert their prior status as ‘head’ of the household (Nagai et al., 2008). However, even in the case where women may have worked and had financial independence in their country of origin, increased risk of IPV continues to be the case in countries of refuge. Many women interviewed in the SEREDA were employed and had financial independence in their country of origin but were still victims of IPV in countries of refuge. In the quote below, a forced migrant woman in Australia reflects on her increased risk of and exposure to sexual violence while in Turkey, despite the fact that she was also the primary breadwinner in her country of origin, Iraq. In this example, the forced migrant woman was living in an urban setting (as opposed to a camp setting) and structural violence, in the form of her forced migrant status, meant she was unable to report an assault:

“There were problems every day when we were in Turkey. I was exposed to more harm when I was in Turkey because of him. He used to come home drunk every day … All the Iraqi men used to gather at this late-night coffee shop and get drunk together. Usually, when he comes back from these nights out, his friends drop him home at the door. One time, his friend also came inside the house. Both of them were drunk and they came home to continue drinking. When I heard them come in, I grabbed my laptop and went into my room. Then, someone opened the door and I realised that my husband was asleep on the sofa and his friend was tried to come into my room and force himself on me. When he tried to force himself on me, I hit him and hit him but it didn’t make a difference. My kids were in the room and my daughter was awake. I tried to get to the kitchen to get a knife so that I could stab him but I was worried that if I killed him, I would lose my children. So, I kept hitting him with my fists instead. My daughter was awake and saw everything but didn’t know who I was hitting–she thought it was her father. I couldn’t complain about this guy to the Turkish Police because I was on a refugee visa”

– Diyana (Iraqi/Assyrian Woman Interviewed in Melbourne, Australia)

Many forced migrants living in refuge in urban settings are not provided with humanitarian support and are simultaneously excluded from the social welfare system, services and formal work (Gebreyesus et al., 2018). This too can be construed as a form of structural violence causing gendered harms. Lack of access to welfare or work can force women to take informal work which heightens their vulnerability to exploitation and sexual violence by driving them into sex work and/or crowded living conditions which pose additional risks (Gebreyesus et al., 2018). Yasmine and Moughalian (2016) describe the situation in Lebanon, where Syrian women were subject to institutionalised, multi-systemic violence as a result of sexism, classism, and racism. The first challenge for many upon arrival in the country of refuge is securing accommodation. Female-headed forced migrant households are most at risk and may be forced to stay in informal settlements, garages, tents or unfinished buildings (UNHCR, 2014). Some women described being rejected from hospitals while in labour if unable to make payments, or Lebanese hospitals adopting aggressive methods such as holding newborns hostage to enforce payment (Yasmine and Moughalian, 2016). A forced migrant woman interviewed in Turkey reflected on the lack of access to and awareness of services for forced migrant women, particularly those experiencing violence:

“After coming here, my husband beat me. He even broke my nose. My neighbour took me to the hospital while I was unconscious … I was scared, I didn’t know what the rules are here, whether women are protected or not, I had no knowledge; I was in Turkey for a year, I had no information. Nobody gave us any information … Human Rights was a street up, I saw them, there was no interpreter in Human Rights. But there was an interpreter at UNHCR, but no one gave information about women’s rights”

– Mariam (Afghan Woman Interviewed in Gaziantep, Turkey)

Even in refugee camps which are, in theory, designed to meet the needs of forced migrant populations, the administration, built environments, and policies relating to security, healthcare, shelter, food distribution, and sanitation can discriminate against women and can be understood as gendered forms of structural and symbolic violence. For example, there has been a widespread policy in refugee camps that only one ration card is provided per family, and this is most commonly in the name of the male “head of household”. Allocating men as “head of household” can strengthen a man’s control over a woman, which can exacerbate the risk of IPV (Schmiechen, 2003). Similarly design and sanitation policies can also expose women to violence. Latrines, for example, are usually placed far from the shelters in unlit and isolated areas. In refugee camps in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone most sexual attacks on women and girls were reported to occur when they go to the latrine or bathroom (Schmiechen, 2003). More recent reports indicate that this is still the case in many refugee camps, with Rohingya girls and women lacking safe spaces for sanitation in camps in Bangladesh (Bonefeld, 2018). Another study in the Dadaab camp complex in Kenya, suggests that measures to implement more gender-sensitive design have only been partially effective in reducing sexual violence (Aubone and Hernandez, 2013).

In both Urban and refugee camp settings, power imbalances created by structural systems and institutions in countries of refuge also place women at greater risk of coerced transactional sex. Women can be pressured to have sex by those with greater structural power, such as landlords, NGO members, government officials, employers, security forces, and the local police (Anani, 2013; UN Women, 2014; UNHCR, 2014; Yasmine and Moughalian, 2016). These Structural power imbalances also prevent victims from reporting because they fear increased violence and stigmatisation, or because they cannot pay associated reporting fees (Krause, 2017).

Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in Countries of Resettlement

Even for the small proportion of the world’s forced migrants who are resettled in wealthier countries, structural, symbolic and interpersonal SGBV remains a continued threat for women and girls (Buscher, 2017). The lack of access to basic rights and services is not confined to unstable regions or countries of refuge in the “Global South” but is increasingly faced by forced migrants who are resettled in high income countries to find restrictive immigration policies and a lack of social support that threatens their safety (Canning, 2017).

In countries of resettlement, policy, legislation, and anti-immigration ideology intersect in a way that compounds harms to forced migrant women. Rather than alleviating the impacts of previous violence, experiences of resettlement in high income countries often exacerbate the impacts of previous physical and mental injury under the guise of “refugee protection” (Betts, 2009; Canning, 2017). State actions that facilitate suffering, and their inaction in alleviating easily anticipated and avoidable harms, comprise forms of structural violence that exacerbate previous harms forced migrant women have experienced (Phillimore et al., 2021). Such violence includes a lack of social support; inadequate opportunities to learn the host-country language; a lack of employment opportunities; and a lack of financial support or access to childcare. These factors place forced migrants at an increased risk of poverty (Zannettino, 2012). These acts of structural violence have gendered consequences, with forced migrant women being more likely to experience poverty and destitution (Canning, 2017). Interviews conducted for the SEREDA project highlighted how precarious and informal work, and unemployment perpetuate the economic challenges faced by forced migrant women exacerbating their impoverishment in the resettlement period. A woman interviewed in Sweden reflects on going from being financially independent in her country of origin to struggling to make ends meet, with little financial support and few employment opportunities upon arriving in Sweden:

“Anyway, you cannot do anything in that period [waiting for the decision]. You think ‘What will [be] the outcome of that interview? What will I do if it is rejected’ all the time? I have already fled here to avoid prison. You don’t know what happens if I get sent back. You come out of a very active life and live completely isolated here. You receive no economic support. They give you 1800 krona (180 Euro) for a month and expect you to live with it. Or you stay in camps and receive 700 krona. They don’t give you a job, but they give you a work permit. But what are the job opportunities for you? Either you work at the pizzeria or kebab shops that are owned by people from your own country, or you don’t work at all. I couldn’t work because of the language barrier. This process was very difficult for me. You question your own existence. Who am I? What will I do in my future?”

– Zeynep (Turkish Woman Interviewed in Uppsala, Sweden)

Furthermore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, research undertaken in five countries highlighted how many forced migrant SGBV survivors were excluded from social protection mechanisms supporting the general population and unable to access NGO services which had gone online (Pertek et al., 2020; Author 3 et al., 2021).

A lack of social and financial support services for forced migrants, combined with traditional beliefs around gender roles, can place forced migrant women at a greater risk of IPV (Zannettino, 2012). As can be the case in countries of refuge, changed gender roles during resettlement can result in shifts in perceived status, and changes in labour force participation and decision-making roles (Zannettino, 2012; Abraham and Tastsoglou, 2016). Men may subsequently feel that their status within the family is threatened if they cannot provide for their families, and this can be exacerbated if welfare is paid to women rather than to men (Zannettino, 2012). Furthermore, insufficient social and mental health support for forced migrant men means many are unable to access help in dealing with the stress of resettlement. Some forced migrant men use violence against their partners as an attempt to regain the control they feel they have lost inside and outside the home (Zannettino, 2012; Vaughan et al., 2015). A forced migrant woman interviewed in Australia reflects on how power and control was used to assert dominance over her and her children by her perpetrator:

“Once, he tricked us and said he wanted our passports to get us mobile phones so that we could communicate with each other, so I gave him the passports, and then the next day I was speaking to the neighbour … He originally didn’t want to get us phones because he wanted any phone call that I got to go through him so that he would know what was happening. So, then the neighbour asked me ‘why did he take your passport?’ and I told her ‘so that he can get us phones’ and she said ‘you don’t need passports for that–what does your passport have to do with a mobile phone?”

– Rita (Syrian Woman Interviewed in Melbourne, Australia).

As noted earlier, forced migrants are often subjected to interlinked symbolic and structural violence through migration and asylum processes. A woman’s risk of IPV upon resettlement can be further exacerbated by her immigration or visa status (Abraham and Tastsoglou, 2016). In the United Kingdom, women who join their partner on spousal visas are often subject to immigration control for up to 4 years after marriage, during which time many are not permitted to work and cannot access welfare benefits. If they separate from their partner then they will be deported and they struggle to access domestic violence shelters because they have no recourse to public funds, resulting in many women remaining with their abusers. Such insecure immigration status can also be used by perpetrators as a means of control, thus providing the mechanism for IPV (Abraham and Tastsoglou, 2016). Similarly, the asylum system in the United Kingdom requires claims to be made by the so-called “lead applicant” which is invariably a man in mixed gender relationships. Should his case fail, his partner will automatically lose her case too, meaning she may become undocumented, be detained or deported without consideration of the persecution she experienced in her own right.

Forced migrant women who experience IPV during resettlement also face additional and specific barriers to accessing violence services. These include language barriers and limited access to interpreters; feelings of not being culturally safe or represented by existing support systems; fear of engaging with authorities, law enforcement or other “outsiders”; lack of awareness or misconceptions about available services; lack of culturally appropriate services; and fears of ostracism from their communities if they report violence (InTouch, 2010; Kulwicki et al., 2010; Ghafournia, 2011; Zannettino et al., 2013; Murdolo, 2014; Vaughan et al., 2015; Abraham and Tastsoglou, 2016; Block et al., 2021). This means that forced migrant women tend to access services later, if at all, compounding the impact of violence. In the quote below, a survivor interviewed in Australia described her ineligibility to access healthcare services due to her visa status. This is particularly pertinent given that health services often provide an entry point into accessing violence services for forced migrant women (Author 2 et al., 2021):

“There was a time where he attacked me, and I tried to run away from him and I tripped over a dining chair and fell on the dining chair, and my arm went blue and my leg got really swollen and yeh, I showed the police. There was a period of time where I was stuck and I couldn’t go to hospital because I didn’t have a Medicare card or a healthcare card or anything … and those neighbours that helped me, they’re poor and living at home with four kids and aren’t able to support me and my kids as well, and can’t take me to hospital under their name anyway so they would patch me up at home…”

– Rita (Syrian Woman Interviewed in Melbourne, Australia)

If and when women leave violent relationships in the resettlement period, structural violence continues and is often exacerbated. Vaughan et al. (2016) described forced migrant women in Australia leaving the pressured environment at home and entering another pressured environment in short-term accommodation. A survivor interviewed in Australia for the SEREDA project explained the challenges she faced accessing appropriate accommodation for herself and her children:

“They were saying that the government could’ve helped me from the beginning by giving me a commission house or crisis housing … they weren’t able … well, the government were able to but I didn’t allow them because my son was 15 years old so they said to me, we’ll put the son in a different place, and you and your daughter can live in crisis accommodation. I told them that I can’t live without my son, you either put the three of us together … but they said that they’re not able to because crisis accommodation is only for women and for children who are under the age of 15”

– Rita (Syrian Woman Interviewed in Melbourne, Australia)

The domestic violence systems in many countries of resettlement rely on a criminal justice model. However, many forced migrants experiencing domestic violence do not want to engage with the criminal justice system, concerned this might jeopardise other aspects of their social wellbeing, such as their own or their partner’s immigration status, housing, employment, and healthcare which remain insecure (Abraham and Tastsoglou, 2016). Such an approach can have devastating implications for already criminalised communities and populations such as forced migrants, by increasing stigma and in some cases, even jeopardising their right to remain in their new country (Abraham and Tastsoglou, 2016; Vaughan et al., 2015). Criminalising forced migrant men who use violence, while failing to address the structural and symbolic structures and institutions that either abuse women directly, or create the conditions that enable abuse, undermines the prospect of finding sustainable solutions to ending SGBV against forced migrant women. Such an approach also exacerbates racist and Islamophobic narratives often used to depict men in conflict zones as “violent” and subsequently portray violence against women is a “foreign” or “cultural” problem. This portrayal fails to acknowledge the role of structural violence in countries of resettlement in directly perpetrating or indirectly enabling violence against forced migrant women.

Overall, current approaches to addressing SGBV in countries of resettlement do not address the systemic and intersectional nature of violence against women, including its structural and symbolic contributors and enablers (Abraham and Tastsoglou, 2016). A forced migrant woman interviewed in Australia reflected on the hopelessness she feels due to the lack of meaningful action by violence services:

“I’ve talked to a lot of people about family violence, but I feel like I haven’t benefit anything … I’ve actually been worse off by accessing services. My mental health is now worse than it was before because of the lack of action by services around family violence.I feel like there’s no difference, whether I talk or I don’t talk, I lose out. I talk or I don’t talk, I’m stuck in the same spot”

– Diyana (Iraqi/Assyrian Woman Interviewed in Melbourne, Australia)

Conclusion

This paper has examined SGBV experienced by forced migrant women in pre-conflict, conflict, transit, countries of refuge, and resettlement contexts. In each of these settings, we have shown that the protection obligations of States that are signatories to the Refugee Convention, are routinely disregarded by statutory authorities, including in countries with a long history of welcoming forced migrants. In fact, rather than offering support and protection, this article highlights ways that governments facilitate and perpetrate structural violence against forced migrant women through administrative and legal regulations, processes, and organisations. For individual women, the refusal of refuge and withholding of protection makes it more likely that they will experience SGBV, and less likely that they will access support services in the face of SGBV. This creates a compounding and self-perpetuating cycle of violence and keeps these harms hidden from public view.

We have argued here that gendered forms of structural and symbolic violence facilitate and compound harms from interpersonal violence. We have demonstrated that experiences of SGBV are frequently multitudinous and intertwined and the violence and harms experienced accumulate over time and space. Such an approach highlights the full extent of women’s experience which is essential to shape the development of effective policy and practice that can interrupt and ameliorate the continuum of harm experienced by SGBV survivors and maximize women’s potential for recovery.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the sensitive nature of the data means that there are ethical requirements stipulating data cannot be shared. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to JP (email: j.a.phillimore@bham.ac.uk).

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee, University of Birmingham Humanities and Social Sciences Ethics Committee, Swedish Ethical Review Authority, and Bilkent Ethics Committee for Research with Human Participants. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

The paper was originally conceptualised by KB and JP. JH analysed the data and wrote the paper. JH was also involved in data collection. HB, LG, CV, and SO provided feedback on multiple drafts of the paper, along with KB and JP.

Funding

The Sexual and gender based violence in the refugee crisis (SEREDA) Project is funded by Riksbankens Jubileumfond as part of the Europe and Global Challenges Programme and Lansons.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abo-zena, M. M. (2017). Exploring the Interconnected Trauma of Personal, Social, and Structural Stressors: Making "Sense" of Senseless Violence. J. Psychol. 151 (1), 5–20. doi:10.1080/00223980.2016.1241738

Abraham, M., and Tastsoglou, E. (2016). Addressing domestic violence in Canada and the United States: The uneasy co-habitation of women and the state. Curr. Sociol. 64 (4), 568–585. doi:10.1177/0011392116639221

Adele Murdolo, A. (2014). Safe Homes for Immigrant and Refugee Women: Narrating Alternative Histories of the Women's Refuge Movement in Australia. Front. A J. Women Stud. 35 (3), 126–153. doi:10.5250/fronjwomestud.35.3.0126

Allsopp, J. (2017). Agent, victim, soldier, son. A Gendered Approach to the Syrian Refugee Crisis, 155–174. doi:10.4324/9781315529653-10

Anani, G. (2013). Dimensions of Gender-Based Violence Against Syrian Refugees in Lebanon. Forced Migration Rev. 44, 75–78.

Aubone, A., and Hernandez, J. (2013). Assessing Refugee Camp Characteristics and the Occurrence of Sexual Violence: A Preliminary Analysis of the Dadaab Complex. Refugee Surv. Q. 32 (4), 22–40. doi:10.1093/rsq/hdt015

Block, K., Hourani, J., Sullivan, C., and Vaughan, C. (2021). It’s about Building a Network of Support”: Australian Service Provider Experiences Supporting Refugee Survivors of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud., 1–15.

Bonefeld, A. S. (2018). When Going to the Bathroom Takes Courage. UNICEF, 2018. Viewed on 30 September 2021. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/rosa/stories/when-going-bathroom-takes-courage.

Bourdieu, P. (1979). Symbolic Power. Critique Anthropol. 4 (13), 77–85. doi:10.1177/0308275x7900401307

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3 (2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Buscher, D. (2017). “Refugees, Gender and Livelihoods,” in Gender, Violence, Refugees. Editors S. Buckley zistel, and U. Krause (Great Britain: Berghahn books), Vol. 37.

Canning, V. (2017). Gendered harm and structural violence in the British asylum system. London: Routledge.

Charles, L., and Denman, K. (2013). Syrian and Palestinian Syrian Refugees in Lebanon: the Plight of Women and Children. J. Int. Women’s Stud. 14 (5), 96–111.

Christian, M., Safari, O., Ramazani, P., Burnham, G., and Glass, N. (2011). Sexual and gender based violence against men in the Democratic Republic of Congo: effects on survivors, their families and the community. Med. Conflict Survival 27 (4), 227–246. doi:10.1080/13623699.2011.645144

Cockburn, C. (2019). “The Continuum of Violence: A Gender Perspective on War and Peace,” in The Criminology of War. Editor R. Jamieson (London: Routeledge), 357–375.

Dekeserdy, W. S. (2021). Bringing Feminist Sociological Analyses of Patriarchy Back to Forefront of the Study of Woman Abuse. Violence Against Women 27 (5), 621–638.

Ellman, N. (2019). Women’s Health and Rights in Immigration Detention. Centre for American Progress. Viewed on 30 September 2021. Available from: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2019/10/21/475989/womens-health-rights-immigration-detention/.

Freedman, J. (2016). Gender, Violence and Politics in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Oxford: Routledge.

Freedman, J. (2007). Gendering the International Asylum and Refugee Debate. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gammeltoft-hansen, T., and Tan, N. F. (2017). The End of the Deterrence Paradigm? Future Directions for Global Refugee Policy. J. Migration Hum. Security 5 (1), 28–56. doi:10.1177/233150241700500103

Gebreyesus, T., Sultan, Z., Ghebrezghiabher, H. M., Tol, W. A., Winch, P. J., Davidovitch, N., et al. (2018). Life on the margins: the experiences of sexual violence and exploitation among Eritrean asylum-seeking women in Israel. BMC Women's Health 18 (1), 135. doi:10.1186/s12905-018-0624-y

Gerard, A., and Pickering, S. (2014). Gender, Securitization and Transit: Refugee Women and the Journey to the EU. J. Refugee Stud. 27 (3), 338–359. doi:10.1093/jrs/fet019

Ghafournia, N. (2011). Battered at home, played down in policy: Migrant women and domestic violence in Australia. Aggression Violent Behav. 16 (3), 207–213. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2011.02.009

Goessmann, K., Ibrahim, H., Saupe, L. B., Ismail, A. A., and Neuner, F. (2019). The contribution of mental health and gender attitudes to intimate partner violence in the context of war and displacement: Evidence from a multi-informant couple survey in Iraq. Soc. Sci. Med. 237, 112457. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112457

Grace, B. L., Bais, R., and Roth, B. J. (2018). The Violence of Uncertainty - undermining immigrant and Refugee health. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 904–905. doi:10.1056/nejmp1807424

Grych, J., and Swan, S. (2012). Toward a more comprehensive understanding of interpersonal violence: Introduction to the special issue on interconnections among different types of violence. Psychol. Violence 2 (2), 105–110. doi:10.1037/a0027616

Human Rights Watch (2012). No place for children: child recruitment, forced marriage, and attacks on schools in Somalia. Viewed 30 September 2021. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/02/20/no-place-children/child-recruitment-forced-marriage-and-attacks-schools-somalia.

Hynes, M., and Cardozo, B. L. (2000). Observations from the CDC: Sexual Violence against Refugee Women. J. Women's Health Gender-Based Med. 9, 819–823. doi:10.1089/152460900750020847

Intouch (2010). I lived in fear because I knew nothing: barriers to the justice system faced by CALD women experiencing family violence. Viewed 30 September 2021. Available from: https://intouch.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Barriers-Justice-System-Faced-CALD-Women-Report.pdf.

Jarallah, Y., and Baxter, J. (2019). Gender disparities and psychological distress among humanitarian migrants in Australia: a moderating role of migration pathway? Confl Health 13, 13. doi:10.1186/s13031-019-0196-y

Jones, C. (2000). Levels of Racism: A Theoretic Framework and a Gardner’s Tale. Am. J. Public Health 90 (8), 121–125.

Jones, C. P. (2001). Invited Commentary: "Race," Racism, and the Practice of Epidemiology. Am. J. Epidemiol. 154 (4), 299–304. doi:10.1093/aje/154.4.299

Keygnaert, I., Vettenburg, N., and Temmerman, M. (2012). Hidden violence is silent rape: sexual and gender-based violence in refugees, asylum seekers and undocumented migrants in Belgium and the Netherlands. Cult. Health Sex. 14 (5), 505–520. doi:10.1080/13691058.2012.671961

Krause, U. (2017). “Escaping Conflicts and Being Safe? Post-Conflict Refugee Camps and the Continuum of Violence,” in Gender, Violence, Refugees. Editors S. Buckley zistel, and U. Krause (Great Britain: Berghahn books), Vol. 37.

Krause, U. (2015). A Continuum of Violence? Linking Sexual and Gender-based Violence during Conflict, Flight, and Encampment. Refugee Surv. Q. 34 (4), 1–19. doi:10.1093/rsq/hdv014

Kulwicki, A., Aswad, B., Carmona, T., and Ballout, S. (2010). Barriers in the Utilization of Domestic Violence Services Among Arab Immigrant Women: Perceptions of Professionals, Service Providers & Community Leaders. J. Fam. Viol 25 (8), 727–735. doi:10.1007/s10896-010-9330-8

Lokot, M. (2019). Challenging Sensationalism: Narratives on Rape as a Weapon of War in Syria. Int. Crim. L. Rev. 19, 844–871. doi:10.1163/15718123-01906001

Marsh, M., Purdin, S., and Navani, S. (2006). Addressing Sexual Violence in Humanitarian Emergencies. Glob. Public Health 1 (2), 133–146. doi:10.1080/17441690600652787

Mcalpine, A., Hossain, M., and Zimmerman, C. (2016). Sex trafficking and sexual exploitation in settings affected by armed conflicts in Africa, Asia and the Middle East: systematic review. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 16, 34. doi:10.1186/s12914-016-0107-x

Meger, S. (2016). The Fetishization of Sexual Violence in International Security. Int. Stud. Q 60, 149–159. doi:10.1093/isq/sqw003

Menéndez-Menéndez, M. I. (2014). Cultural Industries and Symbolic Violence: Practices and Discourses that Perpetuate Inequality. Proced. - Soc. Behav. Sci. 161, 64–69. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.011

Menjívar, C., and Perreira, K. M. (2019). Undocumented and unaccompanied: children of migration in the European Union and the United States. J. Ethnic Migration Stud. 45 (2), 197–217. doi:10.1080/1369183x.2017.1404255

Montesanti, S. R. (2015). The role of structural and interpersonal violence in the lives of women: a conceptual shift in prevention of gender-based violence. BMC Womens Health 15 (1), 93. doi:10.1186/s12905-015-0247-5

Montesanti, S. R., and Thurston, W. E. (2015). Mapping the role of structural and interpersonal violence in the lives of women: implications for public health interventions and policy. BMC Women's Health 15, 100. doi:10.1186/s12905-015-0256-4

Moore, M. W., and Barner, J. R. (2017). Sexual minorities in conflict zones: A review of the literature. Aggression Violent Behav. 35, 33–37. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2017.06.006

Nagai, M., Karunakara, U., Rowley, E., and Burnham, G. (2008). Violence against refugees, non-refugees and host populations in Southern Sudan and Northern Uganda. Glob. Public Health 3 (3), 249–270. doi:10.1080/17441690701768904

Olivius, E. (2017). “Refugees, Global Governance and the Local Politics of Violence against Women,” in Gender, Violence, Refugees. Editors S. Buckley zistel, and U. Krause (Great Britain: Berghahn books), Vol. 37. doi:10.2307/j.ctvw04h31.8

Ozcurumez, S., Bradby, H., and Akyuz, C. (2018). What is the nature of SGBV? IRiS Working Paper Series, No. 27/2019. Birmingham: Institute for Research into Superdiversity.

Ozcurumez, S., Akyuz, C., and Bradby, H. (2020). The Conceptualization Problem in Research and Responses to sexual and Gender-Based Violence in Forced Migration. J. Gend. Stud. 30 (1), 66–78.

Pertek, S., Phillmore, J., and Mcknight, P. (2020). Forced Migration, SGBV, and COVID-19: Understanding the Impact of COVID-19 on Forced Migrant Survivors of SGBV. Birmingham: University of Birmingham.

Phillimore, J., and Cheung, S. Y. (2021). The Violence of Uncertainty: Empirical Evidence on how Asylum Waiting Time Undermines’ Refugees’ Health. Soc. Sci. Med. 282 (9), 114–154.

Phillimore, J., Pertek, S., Akyuz, S., Darkal, H., Hourani, J., and Mcknight, P. (2021). “We are Forgotten”: Forced Migration, Sexual and Gender-Based Violence, and Coronavirus Disease-2019. Violence Against Women, 1–27.

Phillips, J. (2012). The ‘Pacific Solution’ revisited: a statistical guide to the asylum seeker caseloads on Nauru and Manus Islands. Australia: Parliamentary Library of Australia: Parliament of Australia.

Pickering, S., and Cochrane, B. (2012). Irregular border-crossing deaths and gender: Where, how and why women die crossing borders. Theor. Criminology 17 (1), 27–48. doi:10.1177/1362480612464510

Pittaway, E., and Bartolomei, L. (2018). Enhancing the Protection of Women and Girls through the Global Compact on Refugees. Forced Migration Rev. 57, 77–79.

Schlecht, J., Rowley, E., and Babirye, J. (2013). Early relationships and marriage in conflict and post-conflict settings: vulnerability of youth in Uganda. Reprod. Health Matters 21 (41), 234–242. doi:10.1016/s0968-8080(13)41710-x

Schmiechen, M. M. (2003). Parallel Lives, Uneven Justice: An Analysis of Rights, Protection and Redress for Refugees and Internally Displaced Women in Camps. Saint Louis Univ. Public L. Rev. 22 (2), 473–520.

Sharma, V., Amobi, A., Tewolde, S., Deyessa, N., and Scott, J. (2020). Displacement-related factors influencing marital practices and associated intimate partner violence risk among Somali refugees in Dollo Ado, Ethiopia: a qualitative study. Confl Health 14, 17. doi:10.1186/s13031-020-00267-z

Simon-butler, A., and Mcsherry, B. (2018). Defining Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in the Refugee Context, IRiS Working Paper Series, No. 2/2018. Birmingham: Institute for Research into Superdiversity.

Skjelsbaek, I. (2001). Sexual Violence and War: Mapping Out a Complex Relationship. Eur. J. Int. Relations 7 (2), 211–237.

Sokoloff, N. J., and Dupont, I. (2005). Domestic Violence at the Intersections of Race, Class, and Gender. Violence Against Women 11 (1), 38–64. doi:10.1177/1077801204271476

Swiss, S., Jennings, P. J., Aryee, G. V., Brown, G. H., Jappah-samukai, R. M., Kamara, M. S., et al. (1998). Violence Against Women during the Liberian Civil Conflict. JAMA 279 (8), 625–629. doi:10.1001/jama.279.8.625

Thapar-Björkert, S., Samelius, L., and Sanghera, G. S. (2016). Exploring symbolic violence in the everyday: misrecognition, condescension, consent and complicity. Feminist Rev. 112, 144–162. doi:10.1057/fr.2015.53

UN Women (2013). Gender-based Violence and Child Protection among Syrian Refugees in Jordan, with a focus on Early Marriage. Viewed 30 September 2021. Available from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/39522.

UN Women (2014). ‘We just kept silent’: Gender-based Violence amongst Syrian Refugees in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Viewed 30 September 2021. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/iraq/we-just-keep-silent-gender-based-violence-amongst-syrian-refugees-kurdistan-region-iraq.

UNHCR (2020). Figures at a Glance. Viewed 10 November 2020. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html.

Vaughan, C., Davis, E., Murdolo, A., Chen, J., Murray, L., and Quiazon, R. (2016). Promoting Community-Led Responses to Violence Against Immigrant and Refugee Women in Metropolitan and Regional Australia. The ASPIRE Project: Research report. Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety.

Vaughan, C., Davis, E., Murdolo, A., Chen, J., Murray, L., and Quiazon, R. (2015). Promoting Community-Led Responses to Violence Against Immigrant and Refugee Women in Metropolitan and Regional Australia. The Aspire Project. Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety.

Vickers, J., and Yarrow, G. (1991). Economic Perspectives on Privatization. J. Econ. Perspect. 5 (2), 111–132. doi:10.1257/jep.5.2.111

Wachter, K., Horn, R., Friis, E., Falb, K., Ward, L., Apio, C., et al. (2017). Drivers of Intimate partner Violence Against women in Three Refugee Camps. Violence Against Women 24 (3), 286–306. doi:10.1177/1077801216689163

Wasco, S. M. (2003). Conceptualizing the Harm done by Rape. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 4 (4), 309–322. doi:10.1177/1524838003256560

Wirtz, A. L., Pham, K., Glass, N., Loochkartt, S., Kidane, T., Cuspoca, D., et al. (2014). Gender-based violence in conflict and displacement: qualitative findings from displaced women in Colombia. Confl Health 8 (1), 10. doi:10.1186/1752-1505-8-10

Women's Refugee Commission (2016). Women and Girls in the European Refugee Crisis. Viewed 30 September 2021. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/research-resources/refugee-women-europe/.

Women’s Refugee Commission (2014). Unpacking Gender: The Humanitarian Response to the Syrian Refugee Crisis in Jordan. Viewed 30 September 2021. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/research-resources/unpacking-gender-the-humanitarian-response-to-the-syrian-refugee-crisis-in-jordan/.

World Health Organisation (2019). Definition and Typology of Violence. Viewed 20 March 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/violenceprevention/approach/definition/en/.

World Health Organisation (2014). Fact sheet: Intimate partner violence and sexual violence have serious short- and long-term physical, mental, sexual, and reproductive health problems for survivors. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/112325..

Yasmine, R., and Moughalian, C. (2016). Systemic violence against Syrian refugee women and the myth of effective intrapersonal interventions. Reprod. Health Matters 24 (47), 27–35. doi:10.1016/j.rhm.2016.04.008

Yazid, S., and Natania, A. (2017). Women Refugees: An Imbalance of Protecting and Being Protected. J. Hum. Security 13 (1), 34–42. doi:10.12924/johs2017.13010034

Zannettino, L. (2012). "There is No War Here; it is Only the Relationship that Makes Us Scared". Violence Against Women 18 (7), 807–828. doi:10.1177/1077801212455162

Zannettino, L., Pittaway, E., Eckert, R., Bartolomei, L., Ostapiej-piatowski, B., Allimant, A., et al. (2013). Australian Domestic & Family Violence Clearinghouse.Improving responses to refugees with backgrounds of multiple trauma: Pointers for practioners in domestic and family violence, sexual assault and settlement services. Available at: https://library.bsl.org.au/jspui/bitstream/1/4092/1/Improving%20responses%20to%20refugees%20with%20backgrounds%20of%20multiple%20trauma%20%20pointers%20for%20practitioners%20in%20domestic

Keywords: women, refugee, structural violence, symbolic violence, sexual and gender based violence

Citation: Hourani J, Block K, Phillimore J, Bradby H, Ozcurumez S, Goodson L and Vaughan C (2021) Structural and Symbolic Violence Exacerbates the Risks and Consequences of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence for Forced Migrant Women. Front. Hum. Dyn 3:769611. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2021.769611

Received: 02 September 2021; Accepted: 30 September 2021;

Published: 18 October 2021.

Edited by:

Jane Freedman, Université Paris 8, FranceReviewed by:

Lucy Williams, University of Kent, United KingdomRafaela Hilário Pascoal, University of Palermo, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Hourani, Block, Phillimore, Bradby, Ozcurumez, Goodson and Vaughan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jeanine Hourani, amVhbmluZS5ob3VyYW5pQHVuaW1lbGIuZWR1LmF1

Jeanine Hourani

Jeanine Hourani Karen Block

Karen Block Jenny Phillimore2

Jenny Phillimore2 Hannah Bradby

Hannah Bradby Saime Ozcurumez

Saime Ozcurumez