- 1Independent Researcher, Padua, Italy

- 2Department of Political Science, Law and International Studies (SPGI) and Human Rights Centre “Antonio Papisca”, University of Padova, Padua, Italy

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugee (UNHCR) data, approximately 8 million people, mostly women and children, entered and registered in Europe since the beginning of the war on the 24th of February, 2022. It is well-known that human trafficking tends to increase during conflicts and humanitarian crises due to the spread of impunity, destruction of institutions, and breakdown of law. The EU and many international organizations have warned those fleeing Ukraine about the high risk of trafficking and adopted policies to prevent and detect trafficking. The EU anti-trafficking coordinator along with other EU agencies have developed the Common Anti-Trafficking Plan to specifically address this risk and support the potential victims fleeing the war in Ukraine meeting one of the goals set in the 10 Point Action Plan issued by the European Council in March to better coordinate EU actions for people leaving Ukraine. Among other goals, the 10 Point Action Plan aims to improve early identification of the victims of human trafficking as provided by the 2021–2025 Strategy on Combatting Trafficking and the 2011 Anti-trafficking Directive. This paper investigates the actions which the Italian government has put in place to detect and prevent the trafficking of women among the Ukrainians fleeing the war from the beginning of the conflict until September 2022, with a focus on the identification process. More specifically we explored the perceptions of front-line workers and street-level bureaucrats at the Slovenian and Austrian borders, where Ukrainians cross to enter Italy. Through interviews we collected data to shed light on the identification procedures adopted. The need to learn more about the current war in Ukraine corroborates this study. The proposed qualitative analysis has identified three main findings: (1) conflicts create increased opportunities for trafficking that in the case of Ukraine are greater due to the scale of those fleeing; (2) temporary Italian residence permit reveals some criticalities that could lead to greater vulnerability; (3) gaps in the identification process can increase the risks of trafficking, especially in the absence of longer-term assistance programs.

1. Introduction

The lives of people across Ukraine have been profoundly impacted by the humanitarian crisis brought on by the invasion by the Russian armed forces on February 24, 2022. The latest updated information published by UNHCR (2023) indicates that 8,104,606 refugees from Ukraine were recorded across Europe with 4,881,590 displaced persons from Ukraine registered for Temporary Protection or similar national protection schemes in Europe. At this time, it is worth noting that an individual may have multiple registrations in two or more EU countries; incomplete registrations for various reasons; or applicants registrations who have moved onward beyond Europe, as specified by the UNHCR.

On 25 February, 2022, the Italian Council of Ministers issued a state of emergency declaration. The act ensures the Italian state's contribution to Civil Protection initiatives in order to support the affected population. Achieved through different means that include extraordinary and urgent interventions to ensure that assistance in Italy is given to those fleeing the conflict (UNHCR, 2022b).

Of those who fled Ukraine, an estimated 90 percent are women and children as most men aged between 18 and 60 are required to stay behind under martial law. Based on current data from the International Organization for Migration (IOM, 2022), 60 percent of those fleeing from Ukraine were female and 40 percent male. Registration included 159,968 who came to Italy and 149,672 who registered for temporary protection or similar protection schemes (IOM, 2022).

Since the earliest stages of the conflict, large groups of Ukrainians entered Italy. By 21 March 2022 there were already 59,589 people, of which 30,499 were women, 5,213 were men, and 23,877 were children (ISTAT, 2022; Wisthaler and Signori, 2022). Involving “female” immigration from a conflict area that embodies the traits of a “real war,” according to the common political narratives, made the arrival of these foreigners strongly accepted. In other words, Italy has shown a favorable response toward Ukrainians fleeing the war. This diversity has resulted in very different treatment in Italy compared to other foreigners coming from war-torn areas on the humanitarian level (Schiavone, 2022).

As of 1st of January, 2021, according to a National Statistic Institute (ISTAT) survey, 235,953 Ukrainians were present in Italy, of whom 183,053 were women (ISTAT, 2021). Among the people of Ukrainian origin residing in Italy, women were traditionally employed in domestic and care work and have always made up the large majority: in 2021 Ukrainians represented the the 14,1% of the foreign domestic workers in Italy, only after the Romanians (De Luca et al., 2022). It is well known that Ukrainian women are among the most exploited for domestic and care work in Italy, but the identification of the victims is notoriously difficult (Palumbo, 2017) and the situations do not always fall under the Italian criminal law on human trafficking, slavery, and severe forms of labor exploitation. Ukrainian women within the Italian labor market seems to be welcomed, buthis evidence does not prevent concern on the part of those who work in direct contact with vulnerable groups and the victims of both severe labor and sexual exploitation. Even employment rankings suggest that, toward this nationality, there is no opposition to their increase presence but rather a concern on the part of those who work in direct contact with foreigners belonging to vulnerable groups due to possible trafficking or other serious forms of labor and/or sexual exploitation. It is not corroborated by conmsolidated data, but there seems to be a widespread international alarm about this scenario. In this situation a correct and prompt identification process plays a key role in protecting migrants human rights. In this study, we investigate the actions put in place by the Italian government to detect and prevent the trafficking of Ukrainian women and the perceptions of front-line workers and street-level bureaucrats involved in the operations at the borders between Slovenia and Italy and between Austria and Italy, where Ukrainians cross to enter Italy between the beginning of the war and September 2022. We use data collected through seven interviews conducted among stakeholders working for International Organizations, civil society organizations, and NGOs to shed light on the reality of the Italian identification mechanism in these specific border areas.

This article is based on the results of various studies carried out by the two authors in recent years on the relationship between vulnerability and severe exploitation, the trafficking process, with particular attention to identifying the procedures adopted for migrant women arriving in Italy (Degani and Cimino, 2020). To this, a research activity was added that focuses not only on secondary sources concerning this humanitarian crisis and the policy to deal with assistance in Italy as receiving society (scientific research, statistical documents, articles published in international and national newspapers), but also on the use of primary sources drawn from in-depth interviews with stakeholders working at the Italy borders. We interviewed all the organizations which were working at the entry points dedicated to the identification of presumed, at risk or current women victims of trafficking arriving from Ukrainia. It resulted in seven street-level bureaucrats (Lipsky, 1980) working for four organizations involved in the early screening of Ukrainians arriving at the border. We performed seven interviews based on the number of organizations involved in the process of early identification of presumed, potential or current victims of trafficking. Seven might seem a low number, but we interviewed all the front-line workers aimed at spotting trafficking indicators, so this number covers the entire territory. The current reality of the war in Ukraine and the need to produce insights about it, corroborate this research study.

The article is organized as follows: the next paragraph briefly presents state-of-the art literature and discusses the importance of correct and prompt identification when working with people at risk of being exploited. A general early warning of specific risks that women face due to their different vulnerabilities and protection needs is highlighted. Paragraph third offers some insights about “female” dimension of this war and the most relevance literature on the matter. The fourth paragraph introduces the challenge of correct and prompt identification, underlying the importance of bottom-up human rights based efforts in seeking effective responses in terms of the practices and procedures adopted. The fifth paragraph critically presents the EU Temporary Directive and its transposition and implementation in Italy that constitutes the basis for temporary protection. The sixth paragraph provides an overview of the reception system for Ukranians in Italy. The following section is conceived as a methodological note that introduces the exploratory research “in the field” and our focus on the identification process at the Italian borders, showing the need for data. We then present our findings which highlight the gaps in the identification process. The nineth paragraph discusses the evidences presented in the paper and the research results. In the conclusion, we introduce some open questions for further research which consider the difficulties in realizing more appropriate interventions against human trafficking.

2. Relevant literature and theoretical background

The short time span of the war in Ukraine makes the research and analysis of the associated risks of human trafficking and severe exploitation understandably limited with extensive gray literature and policy documents produced at international level by International Government Organizations (IGO) and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO). However, the article by Cockbain and Sidebottom (2022) is an interesting exception. It collects data and evidence gathered through a roundtable with particular focus on the UK's response to people fleeing from the Ukraine in relation to trafficking and exploitation that confirms the need for further research on the matter.

Extensive gray literature however provides insights and information. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime report on December 2022 (UNODC, 2022) illustrates the trafficking and smuggling risks associated with the large number of people in need of protection and assistance while escaping after the end of February 2022. According to UN agencies, the number of Ukrainian people requiring humanitarian aid is about 17.7 million, while 5.6 million people are internally displaced and 5.2 million are returnees from other parts of Ukraine and from abroad. Risks involve the refugees determination to flee and travel onwards as quickly as possible; the large numbers of unregistered individuals offering help, transportation and accommodation, and perhaps with a small number who intend to traffic people on the move. Data from the UN's Office on Drugs and Crime shows that in 2018, Ukrainian victims were trafficked to 29 countries. More than half were identified in Russia and a quarter in Poland, which has taken the largest number of Ukrainians since the war began. The situation has reportedly improved since the beginning of the war as announced by UNHCR already in April 2022 (UNHCR, 2022a).

A report of European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA) and other organizations recognizes diverse risks in relation to “different vulnerabilities and protection needs,” underlining that many people use messaging apps and social media (particularly Viber, Telegram and Facebook) to seek support and assistance (EUAA, IOM, and OECD, 2022). The Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe (2022) has issued a short document listing recommendations of the Special Representative and Coordinator for Combating Trafficking in Human Beings (SR/CTHB) on the need to enhance anti-trafficking prevention amid mass migration flows. The recommendations, based on a real action-oriented approach, indicates many useful procedures and measures to reduce the risk of trafficking for people who flee Ukraine.

In addition, Frontex and Europol are also working on preventing and combating human trafficking in the context of this humanitarian crisis. Frontex (2022) has adopted proactive measures to prevent, identify and tackle human trafficking involving first and second line investigating officers. Europol (2022) released an Early Warning Notification in which it urged EU countries receiving forcibly displaced Ukrainians to remain alert for indications or attempts to recruit potential victims of trafficking in human beings.

A targeted review of reports and statements by NGOs that work in fighting human trafficking to provide migrant support and assistance in war or humanitarian crisis contexts has been undertaken. The range of materials produced is very articulated. The rapid assessment of risks and gaps in the anti-trafficking response written by La Strada with Freedom Fund (Hoff and de Volder, 2022), confirms “traditional” concerns in the identification process, highlighting many shortcomings in current anti-trafficking responses. The authors conducted research on a very limited number of concrete cases between February and May 2022. Their findings relate to the limited information available early on to quantify the scale of the problem even if the risks are clear and are likely to increase (Hoff and de Volder, 2022).

The most relevant warning came from Robert Biedron, chair of the Women's Rights Committee (FEMM), during a joint hearing with the LIBE Committee held on 29 November 2022 where he affirmed that “Hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian women have been victims of human trafficking. This was the case before the war: the phenomenon of women victims of trafficking coming from Eastern European countries became evident after the fall of the iron curtain (Kligman and Limoncelli, 2005). The war has only made it worse and the risks are further increased by traffickers who are increasingly recruiting via online platforms. In the same debate, Valiant Richey stated that instances of rape of Ukrainian women rose by 260% since the start of the war, according to OSCE (Bauer-Babef, 2022). A study of Thomson Reuters Foundation found that, since the war started, Ukrainians have increasingly been targeted for sexual exploitation, both on the ground and online (Fischer, 2022).

Human trafficking is an issue worth discussing in the context of displacement through armed conflict with particular attention toward vulnerability and gender. For many scholars the so-called “nexus” between conflict and trafficking still remains under-scrutinized and difficult to verify in terms of empirical research (Muraszkiewicz et al., 2020). Moreover, as many scholars have highlighted, the inclusion of women in the register of human trafficking may have serious consequences (Mullally, 2014). Clearly, in the migration context, violations of women's migrant rights may be instrumentalized by Governments, so as to legitimize criminal law, limiting the possibility for migrants to move and cross countries on the basis of legal paths. The “continuum of violence” that often characterizes women's experiences in fleeing their country does not fit easily in refugee law texts and even in “trafficking schemes” victims seem to follow stereotypical profiles and portrayals.

The structural violence in their everyday life is exacerbated in repressive policing of dictatorial regimes and in situations of armed conflict. Both scenarios stress the close links between human trafficking, sexual and gender-based violence and criminal activities as the current crisis in Ukraine reveals. Therein, severe exploitation (Cockbain and Sidebottom, 2022) solicits concerted efforts to better understand the problem and foster context-appropriate solutions and responses. Clearly the number of victims of human trafficking in conflict and humanitarian crisis remains unknown due to difficulties in collecting data and to ineffective research methods (Weitzer, 2014). But effective research and analysis are fundamental to collect evidence-based prevention and protection responses to human trafficking and to combat severe exploitation crimes, bringing perpetrators to justice. Scholars, policymakers, academics and civil society recognize that conflict increases the numbers of economic migrants, refugees and displaced persons, and aggravates poverty, determining structural economic changes in conflict zones that can generate new vulnerabilities and corruption amongst other issues, making conflict-afflicted areas a fertile ground for human trafficking. Such situations make people particularly vulnerable to exploitation, not only once they have arrived at a destination, but also en route as they are approached by people looking to exploit them (Healy, 2015). The UNODC thematic report on Countering Trafficking in Persons in UNODC (2018) is a comprehensive guide to integrate the fight against human trafficking devoted to addressing work in the field of United Nations entities and other actors, including NGOs, that support research activities and information-gathering “by ensuring that phenomena related to trafficking, including conflict-related sexual violence, gender-based violence and grave violations against children, are flagged as relevant to counter-trafficking efforts” (UNODC, 2018). The paper re-proposes indicators as tool that street-level bureaucrats and others who engage directly with vulnerable individuals or potential victims of trafficking could use, especially if they are tailored to a specific context. This essay also shows that conflict increases the risk of human trafficking. Based on these considerations the war in Ukraine can also lead to situations of subjugation and exploitation particularly among women and children.

To date, the most significant document on this matter is still the 2018 report of former UN Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons, especially women and children, Giammarinaro (UN HRC, 2018) on the gender dimension of human trafficking in conflict and post-conflict and the nexus with conflict-related sexual violence linked to women, peace and security agenda of the Security Council. In this document, the Special Rapporteur recognizes that, in order to ensure more efficient anti-trafficking responses, a human rights-based approach to trafficking in persons should be mainstreamed into all pillars of the women, peace and security agenda. The report addresses issues of trafficking in situations of armed conflict, updating important international agenda contents prepared by the Special Rapporteur to the Human Rights Council (A/HRC/29/38) on the links between trafficking in persons and conflict from three perspectives: (a) trafficking of persons fleeing conflict, addressing the particular situation of those internally displaced by conflict and of refugees and asylum seekers fleeing conflict; (b) trafficking during conflict for military service and for purposes of sexual and labor exploitation; and (c) trafficking in post-conflict situations, including trafficking and peacekeeper involvement. In 2016, the Special Rapporteur raised the above-mentioned issues at the Security Council open debate on the theme of “Conflict-related sexual violence: responding to human trafficking in situations of conflict-related sexual violence of 2016” presenting her first thematic report on Trafficking in persons in conflict and post-conflict situations: protecting victims of trafficking and people at risk of trafficking, especially women and children (UN HRC, 2016). Her documents brought the issue into the spotlight, creating a stir among the international community to pay attention to it.

The 2017 report (A/72/164), written with the Special Rapporteur on the sale and sexual exploitation of children, provided a study on their vulnerabilities in situations of armed conflict and humanitarian crisis. The theme of trafficking in conflict and humanitarian crises is currently the focus of an upcoming project addressed by the Special Rapporteur, Mullally, to realize a thematic cluster.

As regard as humanitarian emergency and wars, there is also a specific female dimension that in these last decades many scholars had deeply analyzed.

3. The “female” dimension of this war

When war breaks out people, especially girls and women, are displaced. In times of armed conflict, women often take the responsibility and risk of getting their families and themselves out of harm's way to any safe place; even in the context of war, women can play different roles (Manchanda, 2004; Stern and Nystrand, 2006; Sylvester, 2010). Wars and humanitarian political crises always generate gender dynamics, reflecting sexist social norms where: men are expected to fight; women are forced to flee and do not have the same resources, authority, or political rights to satisfy their personal needs. Evidently, this conflict has severely impacted community security, social cohesion, and the resilience of local communities. Contemporary armed conflicts are predominantly internal, with regional and sub-regional dimensions, even if the Ukraine war is clearly an international conflict with many critical elements that tend to generate global rebounds.

As in other current conflicts, civilians and women are disproportionately the victims affected by different forms of gender based violence due to their sex and social status (Heineman, 2011).

Military institutions continue to strongly reflect and embody practices of masculinity in opposition to the notion of femininity (Gardam and Jarvis, 2001; Goldstein, 2001; Buchowska, 2016; Dolgopol, 2016) even if contemporary warfare involves women as combatants much more than before. In present-day armed conflicts, women are still overwhelmingly affected by the multitude of consequences that hostilities create, and it has generally been proven that the experiences of women and men in armed conflicts differ considerably (Gardam and Jarvis, 2001; Buchowska, 2016) due to the gender-based dynamics of the conflicts. The prevalence of sexual violence, is, however, merely one aspect of the distinctive impact of conflict on women. Although a range of factors influence the way individual women experience armed conflict, the endemic gender discrimination that exists in all societies is a common theme. In particular, violence against women and sexual assaults occur in all contemporary armed conflicts (United Nations Review, 2010; Bernard and Durham, 2014; Cohen and Nordås, 2014). They take many forms and are frequently perpetrated simultaneously (Gardam and Jarvis, 2001; Moser and Clare, 2001; Spiegel, 2004; Alawemo and Muterera, 2010). Among many trafficking is one of the main issue of concern and sexual violence—especially in the form of rape—is the most common and predominant form of serious law violations against women (Cohen and Nordås, 2014).

The UN Security Council recognized under Resolution 1325 and in the subsequent resolutions that women are negatively impacted in different ways by economic disadvantages and many forms of gender-based violence that occur in armed conflict (UNSC, 2000). War ordinarily results in economic disruptions in society, which impacts women negatively (Rehn and Sirleaf, 2002). Although women are not vulnerable as such, they are often at risk in conflict situations. Their general condition of powerlessness compared with men, exacerbates the social effects of wartime (Hynes, 2004; Plümper and Neumayer, 2006). In all conflicts, the suffering of women reveals specificities. However, they should not be perceived as a homogenous group due to the differences in needs, level of possibile vulnerabilities and more in general situations they experience. All these mechanisms need to be considered and analyzed through an intersectional lens avoiding to repropose in anti-trafficking discourses rethorical essentialist perspectives and responses that deny women agency and situational vulnerability.

However, the factors that significantly influence women's situation during warfare are those under which women live normally in times of peace (Gardam and Charlesworth, 2000; Gardam, 2013; Buchowska, 2016). This condition is also reflected in the migration processes related to war. Even if, during the conflict, women take over jobs in a plurality of sectors, these positions are very uncertain, and they return to the tasks traditionally associated with housekeeping and care work, generating no income (Gardam and Jarvis, 2000, 2001; CEDAW Committee, 2013; UNHCR, 2022c).

Widespread violence and the difficulties to maintain basic elements of state of law that generally flourish during wartime are often accompanied by a social status decline, during and after conflict (Hynes, 2004; ICRC, 2015), that can favor situations of severe exploitation and human trafficking.

4. Identification challenges within the trafficking process

The importance of an early and proper identification of the victims of trafficking is evident, particularly in the context of mixed flows, where migrants and those fleeing from conflicts, are more vulnerable. When victims are misidentified as illegal or undocumented migrants, generally, they cannot benefit from even the minimal protection afforded to trafficked persons or those at risk of exploitation (Gallagher, 2010; p. 279).

Despite the importance of the identification process, academic materials on the issue are still lacking, and are almost entirely focused on sex trafficking. Lutenco (2012) analyses the identification process on the basis of three essential elements: (1) the procedure by which specific facts are established about the person; (2) comparison of facts within the definition of victim of human trafficking and (3) decision to either grant or deny the status of victim. These elements result in the application of a set of indicators to a factual situation to make a decision. States are encouraged to follow different international indicators developed, among other, by ILO (2009), IOM, UNHCR and UNODC.

In 2017, for the first time, a European member state (Italy), together with the UNHCR, released guidelines for the identification of human trafficking among asylum seekers. In this document, the identification of victims is a multi-phase process aimed at detecting conditions of exploitation through ‘trafficking indicators' in order adequately protect victims (UNHCR and Commissione Nazionale per il diritto di asilo, 2017).

Despite a general agreement among the states, the practical approach at times denies commitments to early identification based on a human rights-centered approach as appropriate strategy in dealing with trafficked persons. The complexity and extreme variability of the phenomenon continue to pose challenges (Bhabha and Alfirev, 2009; Macy and Graham, 2012).

To date there is no defined, universally accepted identification procedure. According to the ‘Recommended Principles and Guidelines on human rights and human trafficking' (UN OHCHR, 2002) there are three main phases: (1) prior to interviewing there is a preliminary screening; (2) a phase that provides information to the person on the protection system; (3) and ‘formal identification' consisting of a set of questions to the person on recruitment, transit and exploitation phases. Only trained professionals can implement the last phase as established by the EU Anti-trafficking Directive 2011/36.

The IOM (2007) “Handbook on Direct Assistance for Victims of Trafficking” lists a set of indicators, that encourage adaptation based on specific contexts. Recently IOM (2016) has reviewed and integrated into the identification process the procedures and indicators, adding specific reference to female victims.

With regard to the identification process of potential, possible, presumed, victims of trafficking, the 2005 Council of Europe (CoE) (Council of Europe, 2005) Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings transposed into Italian Law under n. 108/2010 fills the gap of the Palermo Protocol to the UN Convention on organized crime adopted in 2000, representing a revolution in terms of victim protection and “[p]erhaps the most important of all victim protection provisions is the one relating to identification” (Gallagher, 2006). The Convention in the Explanatory Report (2005) asserts that “[t]o protect and assist trafficking victims it is of paramount importance to identify them correctly” (point 127). Even EU Directive 2011/36 on preventing and combating trafficking in human beings and protecting its victims, implemented in Italy through legislative decree n. 24/2014, defines the paramount importance of early identification procedure in terms of victim protection. From then onwards, States Parties must have trained and qualified staff at the borders to pre-identify victims in all situations where trafficking may be detected early. Following the 2021–2025 Strategy on Combatting Trafficking in Human Beings (European Commission, 2021) and the 2011 Anti-trafficking Directive, the Commission issued the Anti-Trafficking Plan to address the risks of trafficking in human beings and support potential victims among those fleeing the war in Ukraine. In the plan, the need for early and prompt identification of presumed, potential or actual victims of trafficking adopting a gender-sensitive approach is reiterated, together with the recommendation to provide immediate support, assistance and protection measures set forth in the EU Anti-trafficking Directive. Moreover, the Plan states the essentiality to find valuable solutions for the victims' long-term needs, to support them in rebuilding their life in the new country.

In Italy, victim identification procedures of trafficking have been activated and carried out in many different circumstances thanks to the consolidation of multi-agency working among different individuals. This reality does not prevent possible criticalities, but from 2011 onwards, the identification of potential victims of trafficking and exploitation even among asylum seekers and refugees has become an increasingly important issue, seeing the significant mixed migration flows in Italy (Degani and De Stefani, 2020). In other words, the Italian system, despite some shortcomings, generally speaking, complies with important protection standards of trafficked persons.

5. On the EU temporary directive: transposition and implementation in Italy

Although both in the EU Temporary Directive and its transposition in the Italian legislation, there is no mention of the identification and assistance of vulnerable migrants, among which potential, presumed, actual victims of trafficking, it is important to analyse these documents because they are part of the policy framework of the article.

Following the proposal of the European Commission, on March 4, 2022, the Council of the European Union, through Decision 2022/382, decided to activate for the first time Directive 2001/55/EC on minimum standards for giving temporary protection in the event of a mass influx of displaced persons and on measures promoting a balance of efforts between Member States in receiving such persons and bearing the consequences thereof. This aims to cope with the massive displacement of Ukrainians fleeing the war as of February 24, 2022. The Council Decision 2022/382 establishing the existence of a mass influx of displaced persons from Ukraine within the meaning of Article 5 of Directive 2001/55/EC, and having the effect of introducing temporary protection, enforced on March 4, 2022, was implemented by the Italian government through the Decree of the President of the Council of Ministers (DPCM) issued on March 28, 2022. Temporary protection under Directive 2001/55/EC is an exceptional procedure that guarantees, “in the event of a mass influx or imminent mass influx of displaced persons from third countries who are unable to return to their country of origin, immediate and temporary protection to such persons; this is also guaranteed if there is a risk that the asylum system will be unable to process this influx without adverse effects on its efficient operation, in the interests of the persons concerned and other persons requesting protection” (Art. 2).

The activation of temporary protection is conditional on the EU Council, acting on a proposal from the Commission, ascertaining, by a decision adopted by a qualified majority, the existence of a mass influx of displaced persons (Art. 5 co. 1 of the Directive 2001/55/EC). It is, therefore, an instrument of “solidarity” that at the European level has erga omnes effects as it binds all EU member states to apply the Decision's provisions.

Italy implemented the Directive 2001/55/EC on temporary protection with a DPCM on the basis of the provisions of Article 20 of Legislative Decree 286/98 (Consolidated Immigration Act) and Article 3 of Legislative Decree 85 of April 7, 2003, which constitute the internal transposition rule of Directive 2001/55/EC. The categories of persons to whom temporary protection is to be applied are explicitly stated in the decision by which the EU Council activates the protection itself. The Directive 2001/55/EC allows member states to decide, individually or collectively, to admit to temporary protection for additional categories of displaced persons and if they have fled for the same reasons and from the same country or region of origin. Indeed, beyond the contents of the implementing decision, Member States have a certain margin of discretion in the sense that they can admit to temporary protection other categories of displaced persons in addition to those provided for the “natural” beficiaries.

Article 2 of Decision No. 382 of the Council of the European Union and Article 1 of the ad hoc national DPCM (28.3.2022) stipulated that temporary protection applies in summary to Ukrainian nationals residing in Ukraine before February 24, 2022.

Finally, according to the Council Decision 2022/382, temporary protection also applies to those who cannot safely return to their countries of origin, third country nationals, and stateless persons who can prove that they were lawfully residing in Ukraine before February 24, 2022. To prove such conditions they will have to provide valid permanent residence permits. By the Prime Minister's Decree of March 28, 2022, the Italian government decided not to grant temporary protection to stateless persons and third-country nationals other than Ukrainians who were lawfully residing in Ukraine before February 24, 2022, people who fled Ukraine not long before February 24, 2022 as tensions escalated, or those who were in the territory of the Union (e.g., on vacation or for work purposes) close to that date and who cannot return to Ukraine because of the armed conflict. Therefore, Italy does not grant temporary protection to these individuals, without hindering other possibilities foreseen by the law to obtain other forms of protection.

In terms of benefits granted to beneficiaries of temporary protection, the Directive 2001/55/EC stipulates that member states must guarantee the displaced person the following: (1) a residence permit allowing him or her to reside within the territory of the member state in which he or she is, for the duration of the protection itself; (2) the right to engage in any activity as an employed or self-employed person, to participate in activities in the field of vocational training and practical experience in the workplace; (3) the right to have access, if a minor, to the educational system; (4) the right to be “adequately housed” or to receive, if necessary, the means to obtain housing; (5) the right to receive social assistance and medical care in case of insufficient resources; and (6) the right to receive specific medical care in case of special needs.

Displaced persons from Ukraine, even if they do not hold residence permits for asylum seekers or international protection (Art. 5 quater, para. 7, Decree Law No. 14/2022), have the right to access various forms of housing in all types of facilities in Italy for international protection seekers as well as in private housing (Bassoli and Campomori, 2022). In this case, forms of economic subsistence are provided for no more than 90 days until December 31, 2022. The contribution amounts to 300 euros per month for adults and to 150 for each minor for guardians or custodians of minors under the age of 18. Health care is ensured on the national territory through the National Health Service and the assignment of a doctor and/or a pediatrician.

6. The Italian reception system for Ukrainians between new provisions and criticalities

Hosting scheme and the assistance system are also important in analyzing the risks of severe exploitation. According to data available from government sources, as of Febraury 2023, 169,837 Ukrainians had been registered at the Italian borders. Of these, 122,372 are adults, and 49,172 are minors. Among the adults, 91,288 are women, and 31,088 are men (Civil Protection Department, Presidency of the Council of Ministers, 2022).

To harmonize the standard response to the emergency within the country, the Civil Protection Department has prepared the Plan for the Reception and Assistance to the Population from Ukraine (Civil Protection Department, Presidency of the Council of Ministers, 2022a). This supplemented the document on the First Operational Directions for the Planning and Management of the Reception and Assistance of People Fleeing War (Civil Protection Department, Presidency of the Council of Ministers, 2022b). With the operative procedures issued on May 9, 2022, the Plan for the Reception and Assistance to the Population from Ukraine was integrated with measures for widespread reception. It was to be implemented through third-sector and social/private entities in Italy that play an important role in managing assistance services for migrants.

According to political-administrative authorities which design and implement public policy, border police, UNHCR representatives, and Civil Protection volunteers should carry out entry monitoring activities at national borders to intercept the flow of Ukrainian citizens entering Italy and verify their actual needs for support and assistance. Once they reach the transit and first reception areas (established in each autonomous region and province), those who do not already have independent accommodation with relatives or acquaintances should receive basic necessities and suitable accommodations, available within the reception system.

Regional authorities and the commissioners coordinate the organization of assistance and reception activities based on the principle of subsidiarity- operating in conjunction with third-sector entities and, if present, local representatives of the Ukrainian community (Schiavone, 2022). The above-mentioned structure should constantly update the assistance it provides to the Ukrainian population in the national territory, as defined in the first operational indications.

The Italian Reception and Integration System (Sistema Accoglienza Integrazione; SAI), offers homestay situations that can be incorporated into the framework of the Emergency Reception Centers (Centri di accoglienza straordinaria; CAS). According to the Reception and Integration System (based on Decree–Law no. 130 of October 21, 2020 enacted as Law no. 173 of December 18, 2020), access to the SAI's integrated reception services can be provided to refugees, asylum seekers, unaccompanied foreign minors, and foreigners entrusted to the social services upon reaching majority age. Moreover, the SAI can also accommodate victims with special-protection residence permit (recipients of social protection for trafficking and severe exploitation and victims of domestic violence). The multi-level governance approach implemented at the national level should potentially help in identifying possible conditions of vulnerability and situations of subjugations. The SAI system has centrally defined quality standards and national coordination. However, the implementation is managed by the local authorities voluntarily, leaving wide solutions in terms of implementation and the activation of homestay assistance and accommodation. The management of the reception facilities is delegated to third-sector organizations that work in the reception and integration processes within the SAIs, currently strongly involved in supporting Ukrainians. The CAS, managed by the prefectures (the representative body of the Ministry of Interior on local territories), are located in various territories, according to a binding decision of the government and the reception activities, are also delegated to third-sector organizations or even to private organizations. The expected quality standards are much lower than the SAI system, and the provisions migrants are offered are limited to lodging, food, health assistance, and judicial support. Identifying situations of severe exploitation and trafficking in these contexts poses challenges due to the rough relationship between operators and people in need of assistance.

As of 15 February, 2023, about 11,149 Ukrainians were in CAS, while 2,402 were sheltered in the SAI. Finally, 3,266 people were in hotels because there were no more available places in the centers, while 2,162 occupied places in the diffused reception system (Redattore Sociale, 2023). To date, the number of Ukrainians that have been intercepted and entered into contact with the Anti-trafficking system after 24 February of last year are currently 19, while the toll-free number set up by the Department for Equal Opportunities received 58 calls in that period. This tool, which is very useful for the identification of victims, can be used for anonymous calls 24/7. Open to everyone, it can be used, not only by potential victims of trafficking or exploitation, but also by private citizens, law enforcement agencies, representatives of public or private bodies, and members of professional associations in the working environment who may be aware of exploitation or abuse cases and wish to report or have information on these issues. Its operators are linguistic-cultural mediators who speak Albanian, Romanian, Russian, Moldovan, Ukrainian, and Polish, to help potential victims express themselves in their mother tongue.

7. Methodological notes

This is an exploratory study investigating the actions put in place by the Italian government to detect and prevent the trafficking of women among Ukrainians fleeing the war, and the perceptions of frontline workers and street-level bureaucrats involved in the operations at the borders between Slovenia and Italy (Fernetti), and between Austria and Italy (Ugovizza) where Ukrainians cross to enter Italy between the beginning of the war and September 2022. The study narrates the mechanisms put in place in Italy to detect presumed, potential or current victims of trafficking between the beginning of the war until September 2022, as we interviewed all the organizations working on this topic and physically present at the borders. At the time of the research, there were no other organizations working on the identification of presumed, at risk or current victims of trafficking others than those we interviewed.

The research question of the study is, “What actions and projects were implemented by the Italian government to address the increased risk of trafficking and severe forms of exploitation of Ukrainian women fleeing the war?” Our research question is a what question (Blaikie and Priest, 2019) because it requires a descriptive answer, which will describe the characteristics of the reality of the Italian identification system.

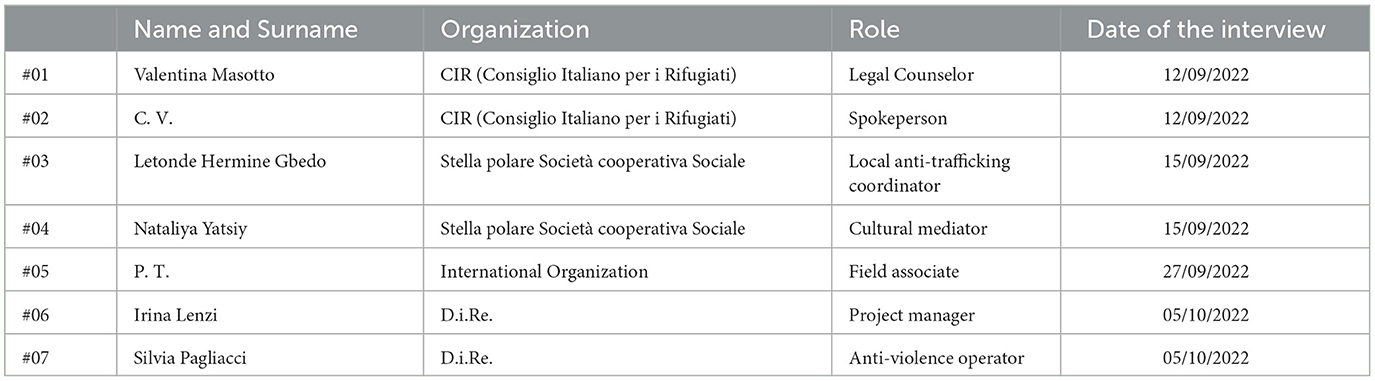

To answer the research question, we interviewed between September and October 2022 all the organizations which were working at the entry points dedicated to the identification of presumed, at risk or current women victims of trafficking arriving from Ukrainia. It resulted in seven street-level bureaucrats (Lipsky, 1980) working for four organizations involved in the early screening of Ukrainians arriving at the border. We decided to perform seven interviews based on the number of organizations involved in the process of early identification of presumed, potential or current victims of trafficking. Seven might seem a low number, but we interviewed all the front-line workers aimed at spotting trafficking indicators, so this number covers the entire territory. Table 1 shows the characteristics of each interviewee, including the role and the organization where they worked.

After transcribing the interviews, we coded and analyzed the data using the NVivo software. We performed a thematic analysis (Boyatzis, 1998) to accurately identified the relationships among identified themes and we formalized these relationships in theoretical propositions. The themes (family codes) were generated both inductively (from the data) and deductively (from the theory and policy framework described previously). Two themes were identified: (1) the perception of the risk for trafficking and severe forms of exploitation, and (2) the risk factors and improvements that could be implemented to guarantee better prevention of the phenomenon.

Given the aim of the study, we adopted a descriptive approach to the analysis, which involves “a descriptive use of the thematic coding […] to describe the phenomenon” (Boyatzis, 1998; p. 129). To ensure the codes' and themes' validity, we performed a Constant Comparison of the codes (Strauss and Corbin, 1990), which is the analytic process of comparing different pieces of data for similarities and differences. The Constant Comparison is a sort of within-code comparison that applies every time a segment of data is coded. Every segment coded with the same code revealed different aspects of the same theme and permitted to better detail the code and to check its internal validity.

We did a triangulation of data and methodologies to ensure validity of the study results by analyzing public policies on the topic through a critical framework analysis (Verloo, 2007; Dombos et al., 2012) declined from a gender-based perspective.

8. On the identification process at the Italian borders: findings

The data analysis showed interesting findings related to the research question. It is important to note that the prompt identification and referral of trafficking victims (potential, possible, presumed or actual adults and minors) at sea, land and airport borders is one of the actions expressly established in the new Italian Anti-Trafficking Plan 2022-2025 (Department of Equal Opportunity. Presidency of the Council of Ministers, 2022). With reference to the “Victim Protection and Assistance” area of intervention, the Plan envisages specific action aimed at ensuring the early identification of trafficking victims (adults and minors) arriving in Italy and the immediate activation of referral mechanisms, through the implementation of effective procedures for the early identification of trafficking victims at all relevant borders, the establishment of very first reception facilities dedicated to pre-identified victims as well as their transfer to anti-trafficking projects.

In this perspective, mutual knowledge of the different procedures applied at border locations and the protection mechanisms provided by the anti-trafficking system, the sharing of good practices and the exchange of information among the different actors involved and institutional referrers also becomes increasingly important.

At the borders between Slovenia and Italy (Fernetti) and between Austria and Italy (Ugovizza), the UNHCR and the United Nations children's Fund (UNICEF), together with other actors, established two hubs, the so-called “Blue Dots,” which offer safe spaces, immediate support, and services to all persons, women, men, and children of all nationalities fleeing from Ukraine. Many actors operate in the Blue Dots, and each of them has its own unique role, although they are all requested to cooperate and work together. At the Blue Dots work the following organizations: the Civil Protection Department, Police, Border Police, UNHCR, UNICEF, Save the Children, ARCI (Italian Cultural and Recreational Association, which deals with migrants' job rights), D.i.R.E. (Women Network Against Violence), and the anti-trafficking local network represented by the social cooperative Stella Polare. The following services are offered at the Blue Dots: informative and confidential one-on-one counseling on services available in Italy, emotional support and counseling, a safe space for children to play, a space to relax and feel safe; support with legal questions and the regularization of the territory; free clothes; and basic needs items.

The interviewees worked for the totality of the organizations involved in the early identification of presumed, potential or actual victims of trafficking: an international organization, Stella Polare, D.i.R.E., CIR (the Italian Consortium for Refugees). The main findings were related to the assessment of the project implemented and its results, and the risk factors observed by the street-level bureaucrats. Two themes were identified: (1) the perception of the risk for trafficking and severe forms of exploitation, and (2) the risk factors and improvements that could be implemented to guarantee better prevention of the phenomenon.

First, all the respondents agreed that it is still too early to tell if the implemented projects to prevent and contrast human trafficking and severe forms of exploitation were effective since the migration flows are changing quickly in their composition, routes, and numbers. Moreover, the participants underlined the peculiarity of the situation where women often try to stop and stay at the Blue Dots for as little time as possible. In such cases, the outreach activities are very hard to conduct. Irina Lenzi, the D.i.R.E. project manager (#06), explained:

“People in transit stop at the border from 15 minutes to maximum 1 hour and a half, and the situation and the people traveling together with the woman do not make the setting ideal to share a traumatic story.”

However, it was acknowledged that the system at the border, aimed at giving first assistance to first arrivals Ukrainians, screening vulnerabilities mainly related to gender-based violence as well as preventing human trafficking and exploitation, was welcomed, as were the opinions of the participants about it.

Moreover, Letonde Hermine Gebdo (#03) explained that

“The constant warnings and the attention on the phenomenon given by the EU institutions, and the sensibilization campaigns were useful to raise awareness on the risk of trafficking for Ukrainian refugees among the front-line workers, but it might be too early to find actual victims, and there is the possi'bility that the traffickers are using different routes.”

Despite the warnings launched by the OO.II and European institutions about the risk of trafficking for Ukrainian women and children already discussed in the previous paragraphs (European Commission, 2022; European Parliament, 2022; European Union, 2022), and the importance for a prompt and early identification of potential, presumed, actual victims of trafficking seth forth in the main documents on the topics and addressed in the third paragraph of this article, the Italian Plan for Ukrainians' reception and assistance (Civil Protection Department, Presidency of the Council of Ministers, 2022b) does not mention the risk and, therefore, does not foresee any action to prevent it. This absence meant that the Italian Government did not place funds for the identification of victims and the prevention of human trafficking and exploitation at the borders but, despite this, civil societies organizations and International Organizations joined forces and designed interventions in this sense finding financial means elsewhere.

When questioned about the perception of the risk by the concerned people, the participants responded that the women did not have a sense of the risk, mostly because they were very focused on the atrocities of the conflict and the relatives they had left behind to fight. Nataliya Yatsiy (#04), cultural mediator for the anti-trafficking project at Fernetti Blue Dot, maintains:

“These women are fleeing the war and they do not think about the possibility that they could find themselves in even worst situations than the war, such as being exploited. They are focused on the atrocities they have suffered during the war, the relatives they have left behind in Ukraine.”

P.T, field associate working in an International Organization (#05), pointed out that “the arriving female migrants are interested above all on the information about the satisfaction of basic needs, like accommodation, economic support, and so on.”

Another relevant finding from the data was related to the reception of the Ukrainians fleeing the war. European citizens opened their doors to host them. The same was in Italy, but there was no monitoring system except for Trieste, where the local municipality was in charge for the coordination. Valentina Masotti from CIR (#01) told that they developed a project to monitor the private receptions too, in order to monitor and support private hosts also to help them to spot vulnerabilities and trafficking indicators. However, Silvia Pagliacci, anti-violence operator for D.i.Re (#07) pointed out that at the beginning of the arrivals, it was very common to see scams related to rental apartments which then resulted to be situations at risk for exploitment.

P. T. (#05), declared that:

“There should be more knowledge about the reception happening outside the governmental reception centers: private families, acquaintances, etc… in these situations there is still a gap in terms of vulnerabilities and particular needs, therefore the trafficking and exploitation risk is higher than in the governmental centers.”

Labor exploitation of Ukrainian women, especially in the care sector, was also addressed. However, identifying the victims is difficult because of the predominance of Eastern European women employed (Triandafyllidou, 2016; Palumbo, 2017) and the literature on the topic is scarce.

A relevant point was made by the local anti-trafficking organization, which explained how they did not receive any extra funding from the government's Department of Equal Opportunity1 to implement their project of identification and prevention of human trafficking among Ukrainian women and children at the borders. The paradox of a tremendous and constant warning from EU institutions on the risk of trafficking did not inspire any concrete action from the government in terms of a effcetive reception plan or an anti-trafficking funding system.

Generally, all the participants agreed on the importance of the Blue Dots. The improvement suggested and encouraged by all interviewees was related to the extension of the services to refugees arriving from all countries, regardless of their nationality. More specifically, P. T. argumented:

Some of the projects implemented for the Ukrainian asylum seekers might be adopted also for asylum seekers coming from the Balkan route. In particular, rising awareness of the risk of trafficking and exploitation would be of tremendous importance.

9. Discussion

A humanitarian crisis such as the current one brings with it other crises. The war is an ongoing humanitarian crisis given the continuing of violence, destruction of infrastructure and services that directly impact the well-being of human lives. Among them is the risk of ending up in circuits of severe exploitation. In recent months, newspapers and media have chronicled the organization of the reception and assistance system, representing how much solidarity has been created around this war. It is precisely this solidarity that is causing Ukrainian women and children to be received directly at the border, and from there, sorted into reception centers, private or public, but all checked and registered with local authorities. However, the exodus of millions crossing the border in a few months is critical to monitor, as criminal organizations and individuals can take advantage of the situation. Among the many NGOs in Romania and Poland, some have been denouncing the risk that women and girls fleeing war may become victims of sex trafficking (Action Aid, 2022a).

In Italy, there are the first potential “traps” on social networks for unsafe housing and “risky” jobs (Slight, 2022). The interviews conducted point to the lack of internal attention to this, and the interviews with the identified stakeholders point to the lack of specific attention to this issue at the borders. The Department for Equal Opportunity of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers has therefore, at the onset of the war, signaled to anti-trafficking projects the need to carefully consider reports about Ukrainian persons who may require special attention. In the context of migration, vulnerability is often used to categorize migrants into specific groups based on precise characteristics (Turner, 2019; Sözer, 2020). The IOM's Glossary on Migration has defined vulnerability in terms of risk (Sironi et al., 2019) as “the limited capacity to avoid, resist, cope with, or recover from harm. This limited capacity is the result of the unique interaction of individual, household, community, and structural characteristics and conditions,” and a vulnerable group as “Depending on the context, any group or sector of society […] that is at higher risk of being subjected to discriminatory practices, violence, social disadvantage, or economic hardship than other groups within the State. These groups are also at higher risk in periods of conflicts, crisis or disasters” (Sironi et al., 2019). These definitions find condensation in the notion of “migrants in vulnerable situations” referring to persons compelled to leave their country of origin, and in need of protection, a condition that many women outside Ukraine are experiencing during this period.

The extreme fragility and pressing economic needs of Ukrainian women attract the interest of criminal exploitation networks, which have been very active since the onset of the refugee emergency. In addition, it seems that these networks operating at the transit points at the borders of Poland and Romania try to exploit women through social media, contacting them on various platforms, offering accommodation, free transportation, and jobs in European countries (Fitzgerald, 2022; Sleigh for the Huff Post, 2022), including Italy. Proposals for car passage by private individuals who show up at the border's first reception centers are not tracked by any international organization, and this alerts the operators (Action Aid, 2022a). Despite this, the findings of the study showed that the perception of the risk among Ukrainian women fleeing war is very limited.

Humanitarian workers have collected fraud and attempted violence reports against single women who have accepted to cross the border with alleged benefactors. In addition, trauma, shame, and language difficulties make reporting of these incidents of violence difficult. Women's specialist support services are pillars in preventing violence and protecting women, but many persons “at risk” of exploitation are unaware that they are in danger (Action Aid, 2022b) even if there is currently little reliable data on the nature and extent of trafficking and exploitation linked to the war in Ukraine.

Three weeks after the EU's decision to implement for the first time Directive No. 55 of 2001 on the “granting of temporary protection” for Ukrainians fleeing war, with the DPCM of March 28, 2022, Italy introduced significant innovations in Ukrainians' access to protection and reception.

The set of reception and assistance interventions for displaced persons from Ukraine implemented by Italy may appear to comply with Directive 2001/55/EC because, if we consider all the tools available, including the subsistence allowance, as of September 8, 2022, 81% of the registered displaced people have received some form of public assistance (according to Civil Protection Department data, 124,327 forms of support were provided for 153,664 temporarily protected persons).

Although, the modest sum of money granted and limited to only three months (300 euros per month for adults and 150 for minors) cannot be considered a measure corresponding to what is required by Directive 2001/55/EC, as it is not enough for housing or the partial cost of hospitality from other sources their own resources (individuals, entities, associations, and the Ukrainian community residing in Italy).

Family-based homestay accommodation has been adopted as public policy (Bassoli and Campomori, 2022). Under the label of “widespread reception,” the Civil Protection Department issued a call in April to allocate of about 15,000 places (domestic reception in more than 4,000 places and apartments managed by third-sector entities through agreements with municipalities). Displaced Ukrainians were allowed to seek independent accommodation and receive a monetary contribution directly. In the exceptionality of the circumstances, therefore, the solidaristic impulse of the population (and of Ukrainians already in Italy) has ensured a response to the vast majority of arrivals. Ukrainians were transported by private car or train instead of publicly–owned or under government management–owned facilities. As the interviews showed, the intention to channel arrivals into organic, organized, and sustainable forms of reception and perhaps even more controllable has been too slow and this has led to numerous problems which increase the risk of severe exploitation.

The accommodation and assistance system in Italy potentially offers sufficient information to women who arrive in Italy and immediately reports their arrival to the authorities upon entering the country. This administrative procedure should prevent and protect those who flee Ukraine from situations of subjugation, fraud, severe exploitation, and violence, at least those who benefit of conventional and controlled forms of hospitality.

However, in the last few months, many suspicious ads on social media pages and proposals for work (in the reproductive/domestic/care sector offering housing and hospitality for single women without children) dedicated to Ukrainian communities have emerged. All of which raise concerns about the risk of exploitation. Ukrainian women in Italy traditionally work in these sectors despite the risks of severe exploitation in agricultural and sexual activities. Third sectors organizations have worked for many years in south Italy with communities of Ukrainian women employed in agriculture to protect and guarantee their rights. Recently, they have been working to protect women and children from Ukraine, monitoring and mapping the risks to which they are exposed in Italy. The Ministry of Family and Equal Opportunities and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation convened the Working Group on Minors, together with the Italian Department for Civil Protection (DCP) and with the participation of the UNHCR, UNICEF, and IOM, to assess needs and coordinate concrete actions concerning the specific situation of Ukrainian minors and adoptees.

To protect people fleeing the war and in line with the EU Solidarity Platform, the EU Anti-trafficking Coordinator adopted the Common Anti-Trafficking Plan (EU Anti-trafficking Coordinator Solidarity Platform, 2022), which met one of the goals set in the 10 Point Action Plan issued by the European Council in March (European Council, 2022), to respond to the crisis. In this document the threat of trafficking in persons is considered “high and imminent.” Based on this policy, the Italian anti-trafficking system received an early warning from the central government to monitor situations involving women and children in particular—but also young men—arriving from Ukraine. UNICEF (2022) and UNODC (2022) underlined the urgent need to pay attention to these targets of the population due to previous implications of the trafficking of Ukrainians (in Russia, Poland, and Germany), which points to the presence of organized crime sexual and labor exploitation (UNODC, 2022). In some cases, as Save the Children denounced (Ferrari and Coppola, 2022), women with children who arrived in Italy relying on unqualified individuals were forced to pay for accommodation and keep children from going to school. At the very least, these situations are currently being investigated. Today, every Ukrainian woman is under acute stress, and nothing seems as dangerous and traumatic as war. The reality of family members separated from each otheris true for millions of refugees. Husbands and adult sons must in the war-conflicted country while their wives, mothers, daughters, sisters, and young girls flee to safer places. The heavier responsibilities emphasize the importance of a mother's role when a nation is at war. Women are torn between womanhood and heroism. Their emotions can trigger a various physical symptoms, making them vulnerable in these situations (Reynolds, 2022).

10. Conclusion

Trafficking and severe exploitation are associated with all conflicts (UN HRC, 2016). It is not due to an eventuality but a systematic interconnection with the causes and consequences of any conflict. War is a propagator of vulnerability, resulting in gender-based violence, trafficking, or other forms of severe exploitation. Women are especially at risk, not because they are inherently weak or vulnerable, but because they hold a subordinate position in power hierarchies. Moreover, vulnerability depends on intersectional factors that interact with gender, including nationality, ethnic or geographic origin, and social status. All these vulnerability factors exacerbate and contribute to a risky situation during a conflict. Conflict brings the crisis of the rule of law, the malfunctioning of institutions, and impunity (Giammarinaro, 2022).

In terms of human rights protection, prompt identification proves to be a crucial indicator of the efforts to fight trafficking together with the quality of reception, that needs to be organized considering individual situations of vulnerability and the risk of subjugation that can arise both during the identification process and in the context of assistance. As many volunteers and others involved in reception have observed, slowness and bureaucratic constraints continue to burden the implementation of the provisions for Ukrainians (Ambrosini, 2022). The fact that civil registration, health cards, employment service records, etc., have been enabled with immediate effect can be welcomed as extraordinary; however, in practice, this has not always been the case. The reception in private homes is advancing slowly and lacks adequate assessment about trafficking and exploitation. Currently, the supportive mobilization that has taken place in recent months has to be reconsidered. Clearly, assistence outside the systems that are truly capable of evaluating the real conditions of people can lead to a lack of protection against severe exploitation. The idea and the phenomenon of the co-production of public services, understood as the involvement of citizens interacting with state actors in policy delivery, are in line with the New Public Governance (NPG) perspective, which emphasizes inter-organizational relationships, networks, and participatory governance (Sorrentino et al., 2018) shifting the more traditional paradigma in Public Adminsitration studies of New Public Management (NPM) (Ostrom et al., 1978). Deregulated reception is not always positive, and the instruments of homestay generally present different outcomes in the implementation of provisions (Bassoli and Campomori, 2022) due to the spontaneous—not professional—character of this kind of hospitality.

Voluntary reception within private homes is unsustainable in relation to vulnerability. It may not even offer guarantees to Ukrainian women regarding severe exploitation. However, national gorvernment and local administrations should prevent situations involving the prostitution of Ukrainian women and their exploitation in the domestic-care sector by offering all the necessary resources for them to live with dignity in a foreign country and make it possible for them to return home as soon as possible if safe conditions permit.

We argue herein is that conflicts tend to exacerbate and compound opportunities for trafficking and severe exploitation, especially for women. These conditions, in the case of the Ukraine war, are exacerbated by the scale of those fleeing, especially women. The paper examines the criticalities of the Italian temporary residence permit based on EU responses to Ukrainian displaced persons and gaps in identifying vulnerable individuals at the borders first of all, and also in the framework of accommodation systems. In fact, the system that set in place at the Italian borders and the arrival mode of these forcibly displaced persons obviously make the identification process of potential cases of trafficking particularly challenging. Reception becomes a fundamental area within which to develop monitoring actions, both in terms of prevention and protection, in situations of serious exploitation that may involve the most vulnerable categories/groups. Moreover, risks of trafficking and severe exploitation may be prolonged due to the absence of longer-term programs on Ukrainians into EU countries and the need for these people to live outside their country.

Data availability statement

Some of the datasets presented in this study are not readily available as they were sourced from institutions working at different levels in the area of migration. Queries regarding the datasets or interviews should be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent for the publication of any potentially identifiable data or images was provided by all participants whose details are included in the manuscript. No direct or indirect identifiers have been included in reference to the interviewee who asked to remain anonymous.

Author contributions

FC and PD contributed to conception and design of the study. Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version for publication.

Funding

The publication of this article was funded by Department of Political Science, Law and International Studies (SPGI) University of Padova, Italy.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^DEO disburses funding for the implementation of projects for the assistance and protection of victims of trafficking in Italy.

References

Action Aid (2022a). Ukraine Crisis: How we're working with partners. Available online at: https://actionaid.org/news/2022/ukraine-crisis-how-were-working-partners (accessed 13 April 2022).

Action Aid (2022b). Gender based violence in Ukraine: The tip of the iceberg. Available online at: https://actionaid.org/opinions/2022/gender-based-violence-ukraine-tip-iceberg (accessed 17 June 2022).

Alawemo, O., and Muterera, J. (2010). The impact of armed conflict on women: Perspectives from Nigerian women. OIDA International Journal of Sustainable Development. 2, 81–86. Available online at: http://www.ssrn.com/link/OIDA-Intl-Journal-Sustainable-Dev.html (accessed June 16, 2023).

Ambrosini, M. (2022). “L'accoglienza dei rifugiati ucraini: eccezione o premessa di una nuova politica dell'asilo?,” in Dossier Statistico Immigrazione 2022, Centro Studi e Ricerche IDOS in collaboration with Centro Studi Confronti (Rome: Istituto di Studi Politici “S. Pio V”).

Bassoli, M., and Campomori, F. (2022). A policy-oriented approach to co-production. The case of homestay accommodation for refugees and asylum seekers. Public Manag. Rev. 3, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/14720222121978

Bauer-Babef, C. (2022). Trafficking and sexual exploitation of Ukrainian refugees on the rise, Euractiv, 20 November 2022. Availble online at: https://www.euractiv.com/section/europe-s-east/news/trafficking-and-sexual-exploitation-of-ukrainian-refugees-on-the-rise/ (accessed June 16, 2023).

Bernard, V., and Durham, H. (2014). Sexual violence in armed conflict: from breaking the silence to breaking the cycle. Int. Rev. Red Cross. 96, 427–434. doi: 10.1017/S1816383115000442

Bhabha, J., and Alfirev, C. (2009). The Identification and Referral of Trafficked Persons to Procedures for Determining International Protection Needs (A Report commissioned by the United High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) No. PPLAS/2009/03). Availble online at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4ad317bc2.html (accessed June 16, 2023).

Boyatzis, E. R. (1998). Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. (London – New Dehli: Sage Publications) Availble online at: https://books.google.it/books?id=_rfClWRhIKAC (accessed June 16, 2023).

Buchowska, N. (2016). Violated or protected. Women's rights in armed conflicts after the Second World War. Int. Comp. Jurisprud. 2, 72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.icj.12002

CEDAW Committee (2013). CEDAW/C/GC/30. General recommendation No. 30 on women in conflict prevention, conflict and post-conflict situation. Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women. Available online at: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/CEDAW/GComments/CEDAW.C.CG.30.pdf (accessed October 18, 2013).

Civil Protection Department Presidency of the Council of Ministers. (2022). Piano Nazionale per l'Accoglienza e l'Assistenza alla Popolazione Proveniente dall'Ucraina. Available online at: https://emergenze.protezionecivile.gov.it/it/pagina-base/il-sistema-di-accoglienza-e-assistenza-alla-popolazione-ucraina (accessed June 16, 2023).

Civil Protection Department Presidency of the Council of Ministers. (2022a). Ukraine Emergency. Cross-Border Entry Dashboard. Available online at: https://mappe.protezionecivile.gov.it/en/emergencies-dashboards/ukraine-maps-and-dashboards/cross-border-entry (accessed January 08, 2023).

Civil Protection Department Presidency of the Council of Ministers. (2022b). Prime Indicazioni Operative per l'Accoglienza e l'Assistenza Alla Popolazione proveniente dall'Ucraina 21 Marzo 2022. Available online at: https://emergenze.protezionecivile.gov.it/static/f9b01e2938be5fdab1f730abb8a034bf/crisi-ucraina-prime-indicazioni-operative-21-marzo-2022.pdf (accessed January 08, 2023).

Cockbain, E., and Sidebottom, A. (2022). War, displacement, and human trafficking and exploitation: findings from an evidence-gathering roundtable in response to the War in Ukraine. J. Human Traffick. 4, 1–30. doi: 10.1080/23320222128242

Cohen, D. K., and Nordås, R. (2014). Sexual violence in armed conflict: introducing the SVAC dataset, 1989–2009. J. Peace Res. 51, 418–428. doi: 10.1177/0022343314523028

Council of Europe (2005). Explanatory Report to the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (CETS No. 197). no. 197. Available online at: http://www.conventions.coe.int/Treaty/EN/Reports/Html/197.htm

De Luca, Tronchin, M., and Di Pasquale, G. E. (2022). Rapporto Annuale sul Lavoro Domestico. Available online at: https://www.osservatoriolavorodomestico.it/rapporto-annuale

Degani, P., and Cimino, F. (2020). On the severe forms of labour exploitation of migrant women in italy: an intersectional policy analysis. Rivista Italiana di Politiche Pub. 3, 337–370. doi: 10.1483/98733

Degani, P., and De Stefani, P. (2020). Addressing migrant women's intersecting vulnerabilities: refugee protection, anti-trafficking and anti-violence referral patterns in Italy. Peace Human Rights Govern. 4, 113–52. doi: 10.14658/pupj-phrg-2020-1-5

Department of Equal Opportunity. Presidency of the Council of Ministers (2022). Piano Nazionale Anti-Tratta 2022–2025. Available online at: https://www.pariopportunita.gov.it/it/politiche-e-attivita/tratta-degli-esseri-umani-e-grave-sfruttamento/piano-nazionale-d-azione-contro-la-tratta-e-il-grave-sfruttamento-degli-esseri-umani-2022-2025/ (accessed June 16, 2023).

Dolgopol, U. (2016). “The construction of knowledge about women, war and access to justice, in Imagining Law: Essays” in Conversation with Judith Gardam, eds. S. Dale, and P. Babie. (University of Adelaide Press: JSTOR), 133–152. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.20851./j.ctt1sq5x0z.10 (accessed August 28, 2022).

Dombos, T., Krizsan, A., Verloo, M., and Zentai, V. (2012). Critical Frame Analysis: A Comparative Methodology for the'Quality in Gender+ Equality Policies'(QUING) Project.

EU Anti-trafficking Coordinator Solidarity Platform Directorate-General for Migration Home Affairs. (2022). Anti-Trafficking Plan to address the risks of trafficking in human beings and support potential victims among those fleeing the war in Ukraine. Available online at: https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/news/anti-trafficking-plan-protect-people-fleeing-war-ukraine-2022-05-11_en (accessed January 08, 2023).

EUAA IOM OECD. (2022). Forced displacement from and within Ukraine: Profiles, experiences, and aspirations of affected populations. Available online at: https://euaa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/2022-11/2022_11_09_Forced_Displacement_Ukraine_Joint_Report_EUAA_IOM_OECD_0.pdf (accessed June 16, 2023).