- 1Faculty of Philosophy, Institute for Media Research, University of Rostock, Rostock, Germany

- 2Faculty of Architecture and Design, Hochschule Wismar University of Applied Sciences Technology, Business and Design, Wismar, Germany

The representation of mental illness is part of many video games; however, it is often accompanied by stigmatization of and discrimination against those who are affected. Recently, a more positive approach has been found, including a dimensional representation of mental disorders such as depression or anxiety, especially in games developed by independent developers. The study examined the most popular video games of 2018 and 2019 based on their representation of mental illness in a mixed-methods approach. A quantitative coding process examining general aspects of the games, the characters affected, and the illness representation is followed by a qualitative video game analysis of the games in the sample with a dimensional representation of mental illness. It was found that 16 of the 74 games examined included characters who were affected by mental illnesses. For the most part, mental illness is an essential aspect of the games analyzed in the sample represented by the main characters. However, the depiction of mental illness often lacks depth and dimensionality. Two examples in the study offer a dimensional representation that includes mental illness as characters, as part of the environment and atmosphere, and provides illness-related advice as part of the gameplay. These findings can be helpful for developing games with the potential to reduce discrimination and stigmatization of mental illness and those affected in the future by pointing out aspects leading to a more dimensional and empathetic portrayal of mental illness in existing games. Additionally, the category system used in this study is adaptable to future qualitative research on mental illness representation in video games.

1. Introduction

Mental illness (MI) affects approximately every eighth person worldwide (World Health Organization, 2022). What distinguishes it from most physical disorders is that it is, in many cases, invisible. For instance, depression or anxiety are hardly recognizable based on a person's outward appearance (Lindsey, 2014). Therefore, those affected often experience a paucity of empathy, acceptance, or even discrimination from members of society. Comprehensive knowledge of MI is essential for identifying certain disorders, preventing risk factors and causes, and being informed about the available sources for professional help and mental health information (Jorm, 2000). The media is a highly significant source of illness-related knowledge. However, representations of MI and those affected are often negative and incorrect, which negatively affects the attitudes and beliefs of the general public (Edney, 2004). Negative depictions might cause prejudices against people who are affected, resulting in social isolation and disadvantages within the job field or social life and negatively influencing the willingness for early detection and treatment regarding mental health problems (Scherr, 2019). With ~3.2 billion people worldwide using video games (Newzoo, 2022), they belong to the most impactful types of digital media. The aspect of interactivity that allows players to actively participate and affect the content and the dynamic of its unfolding (Ryan, 2001; Neitzel, 2012) distinguishes video games from most other audiovisual media. Therefore, players are not merely passive spectators of what is happening to the characters in the game but instead take on their roles, interact with them, or even impact their fate. However, video games are not free from negative portrayals that misrepresent reality and contribute to the stereotypization, stigmatization, and discrimination of MI and those affected.

2. Current research

In plenty of games, characters affected by MI are depicted as violent, dangerous, and aggressive. Often, they are antagonists or side characters who harm protagonists (Morris and Forrest, 2013; Shapiro and Rotter, 2016; Ferrari et al., 2019). Many games do not depict them as individual human beings but as representatives of the illness within the game, considering them untrustworthy and their illness-related experience irrelevant (Lindsey, 2014). Another preconception often reproduced within games is the assumption that those affected are lonely and helpless, with little to no hope for recovery (Ferrari et al., 2019). Mental health institutions are frequently used as settings in horror games, evoking a dark, horrifying, and discomforting atmosphere. An abandoned asylum as the game environment is usually an indicator for players to be on guard. Psychiatric interventions, in general, are hardly ever part of games. The few exceptions, including medical treatment, portray them as expensive and ineffective (Morris and Forrest, 2013; Ferrari et al., 2019; Dunlap and Kowert, 2021b; Buday et al., 2022).

However, not all games dealing with MI reproduce stereotypes and stigmatization. Especially in recent years, an increasing number of games representing MI have taken a much more positive approach. One example is Hellblade: Senua's Sacrifice (2017), an action-adventure published in 2017. The game centers around a young woman in the eighth century suffering from psychosis. Aside from the negative and disturbing aspects of the illness, there is also a more positive perspective. Several times throughout the game, Senua's hallucinations are a gift, aiding the players in solving puzzles and making progress. Furthermore, at the very beginning of the game and on the website of the development studio, content warnings, as well as references to sources of illness-related information and aid organizations, can be found. In the development process of the game, people affected by psychosis and medical professionals were consulted (Fordham and Ball, 2019; Anderson, 2020).

Working with experts on mental health, such as medical professionals, scholars, and people affected, can be a valuable source for portraying MI in a realistic and empathetic way. Game designers might also use their own experience of suffering from mental disorders. Such expertise can provide accurate illness-related information, legitimize those portrayals, and initiate innovative games by cooperating with different fields (game industry, medicine, and academia) based on mutual interests (Schlote and Major, 2021). Games developed by independent studios often include progressive and more positive representations of MI. On the one hand, they are not affected by the pressure to design games for the mainstream market, leading to more creative freedom. Therefore, they are free to tackle serious and sensitive topics. On the other hand, they have considerably lower budgets than big studios and do not reach a broader audience in most cases. Hence, more elaborate productions are hardly possible, or they heavily rely on funding (Fordham and Ball, 2019; Runzheimer, 2020).

3. Dimensional model for MI representation in video games

Dunlap and Kowert developed a category system for representing mental illness in digital games. They identified three dimensions: First, the decorative representation, where MI is not essential to the characters, the story, or the game's environment. There are general references to the illness as having mere decorative aspects carrying little to no significance. In those cases, references to the illness do not contribute to the development of the story or the characters. Removing those references would not alter the overall story. For example, the name of a character indicates that they are “crazy ”or “ill.” The defining representation treats MI as essential to the game without exploring it beyond the surface. A psychiatric hospital becoming a horror game setting to create an unsettling atmosphere or an illness as the primary explanation of a character's backstory or motivations are examples of this lack of dimensionality. Lastly, the dimensional representation includes depth and dimensionality, examining MI from several perspectives. The experience of being affected by MI is recreated authentically, for example, using sound, visual effects, and game mechanics to simulate symptoms and create an empathetic link between the player and the character affected (Dunlap, 2018; Dunlap and Kowert, 2021a,b).

The current study evaluates the most popular video games of 2018 and 2019 according to the Internet Movie Database (IMDb) regarding the portrayal of MI. It discusses how MI can be represented not only through the characters affected but also as a part of the game environment, atmosphere, and gameplay, without any stigmatization. The questions focused on in this study are as follows:

Q1: How is MI represented in video games?

Q2: How is MI implemented in different elements of the game (character, environment, and gameplay)?

Q3: How might players benefit from the representation of MI in video games?

4. Method and sample

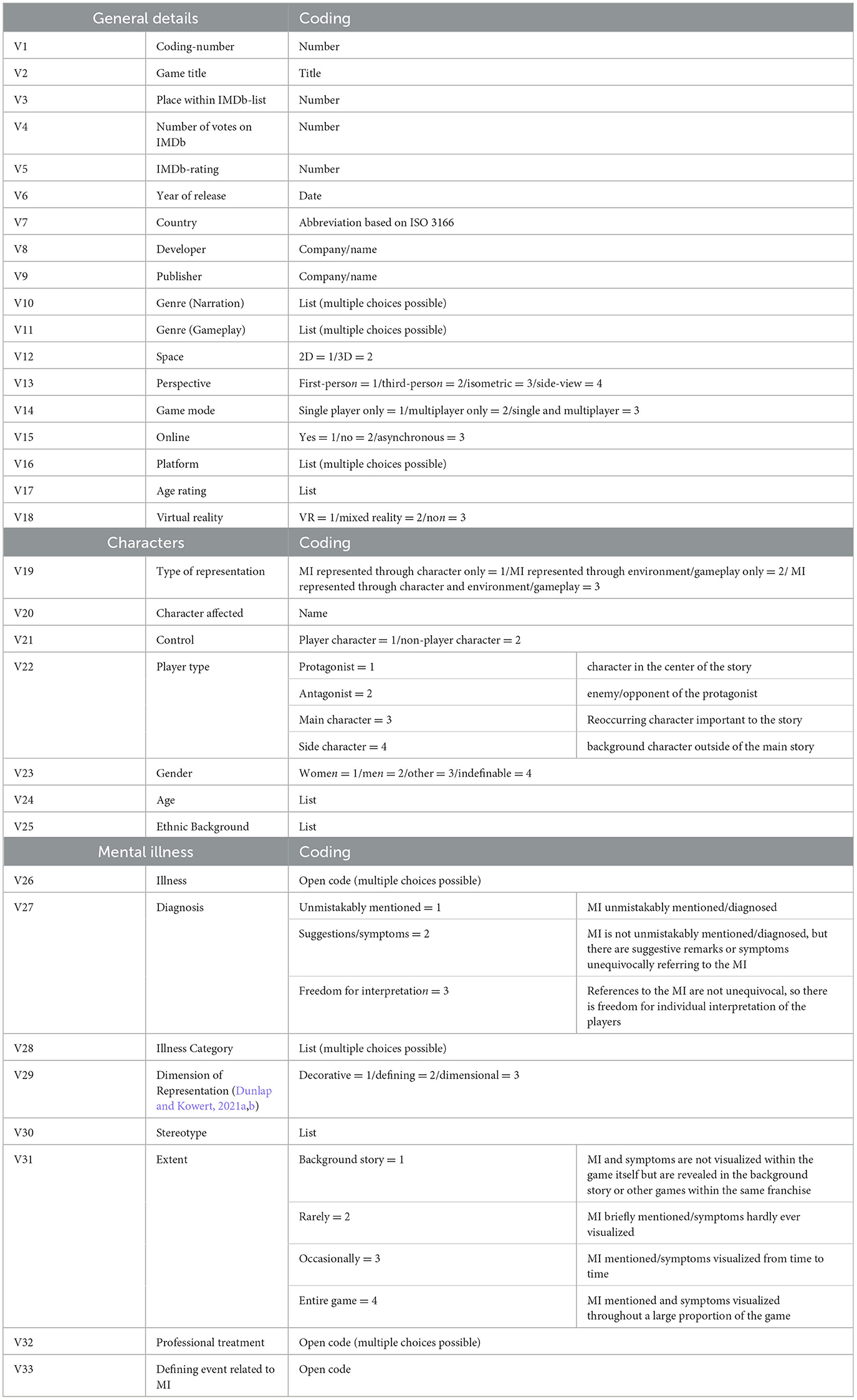

The sample consists of the most popular video games published in 2018 and 2019, according to the Internet Movie Database (IMDb). As the leading platform for user ratings on audiovisual media, IMDb is a relevant source of the popularity of games, since an overview of the sales figures or the number of players was unavailable. The search was limited to games developed in 2018 and 2019, with a minimum of 250 user ratings on the platform. Therefore, lesser-known games with a high rating score were excluded. These search criteria led to 74 games that were examined based on whether they dealt with MI. For each game, a search of the title in combination with MI-related terms (e.g., “mental health,” “addiction,” “depression,” and “madness”) was performed. User-created game wikis, the websites of the games, and YouTube videos served as sources for further information on the representation of MI within those games. Games dealing with MI were analyzed based on the coding process by Prommer and Linke (2017). This method allows a comprehensible and verifiable thematic structuring of the content. A coding book is created beforehand, including categories (themes or thematic structures; e.g., the type of character) and codes (corresponding manifestations of the categories; e.g., protagonist, antagonist, and side character). For some codes, rules and textual examples are applied within the coding book to ensure coherent coding. There can also be open categories, where the corresponding codes are not defined beforehand but worked out in an inductive process based on the similarities of the findings. The coding in this contribution focuses on information on general details of the games, the characters affected by MI, and the mental illness in question (Table 1).

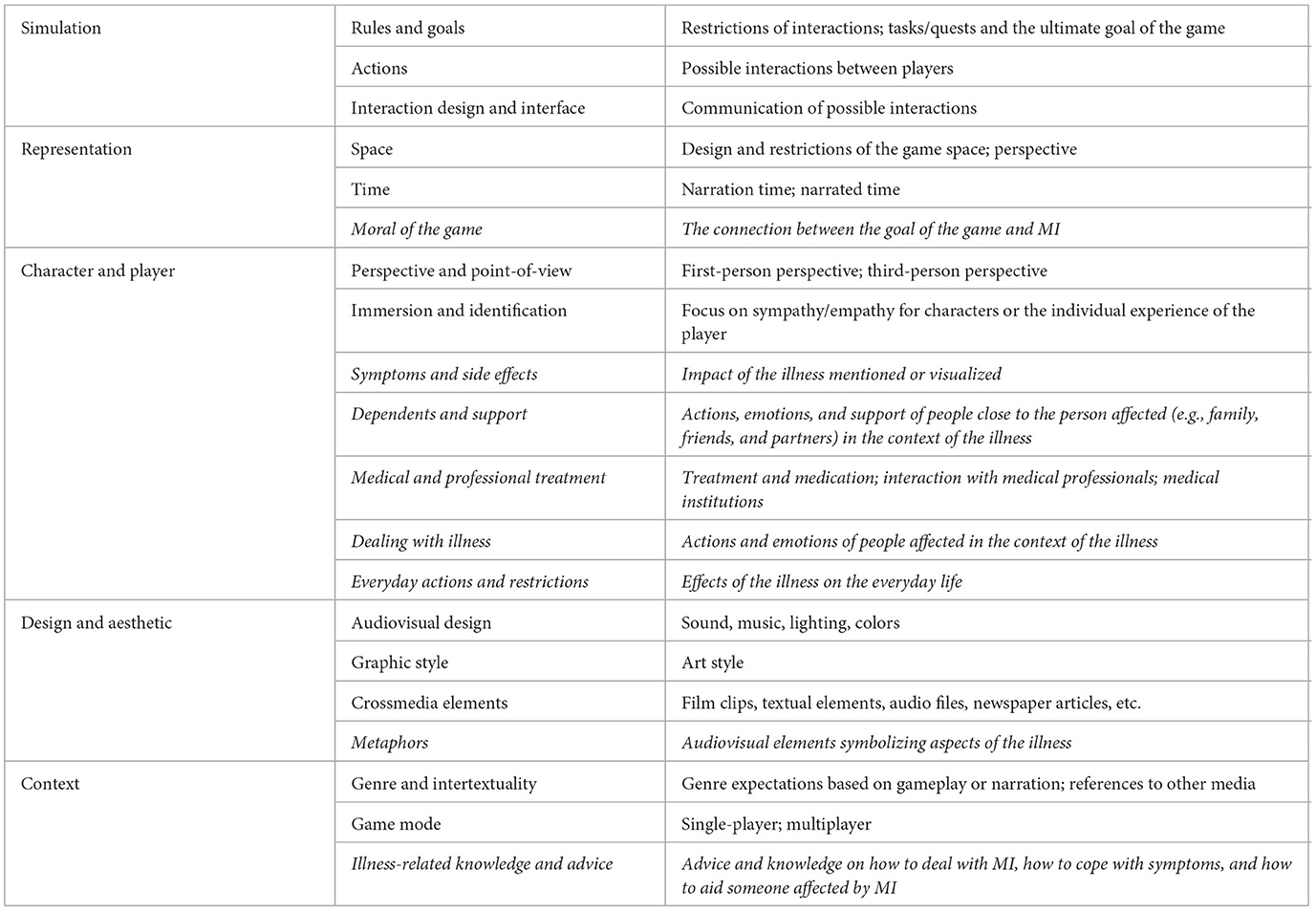

The following step includes a video game analysis, examining games dealing with MI in depth and from different perspectives. The sample of this qualitative examination depends on the dimensional model by Dunlap and Kowert: Only games including a dimensional representation of MI were considered in the analysis. Similar to the method of movie and television analyses, video game analysis includes the content's description, analysis, interpretation, and evaluation. There are five elements: Simulation layer (ludic layer; intervention of the player), representation layer (narrative layer; what is depicted/narrated and how), characters and players, media design and aesthetic, and context. The focussed elements and categories depend on the individual research questions (Eichner, 2017). Beyond the given categories, the analysis includes additional illness-related categories in the context of MI. Therefore, the category list (Table 2) is adaptable for future qualitative analysis of the representation of MI in video games.

Table 2. Video game analysis (Eichner, 2017) and additional MI-related categories.

5. Results

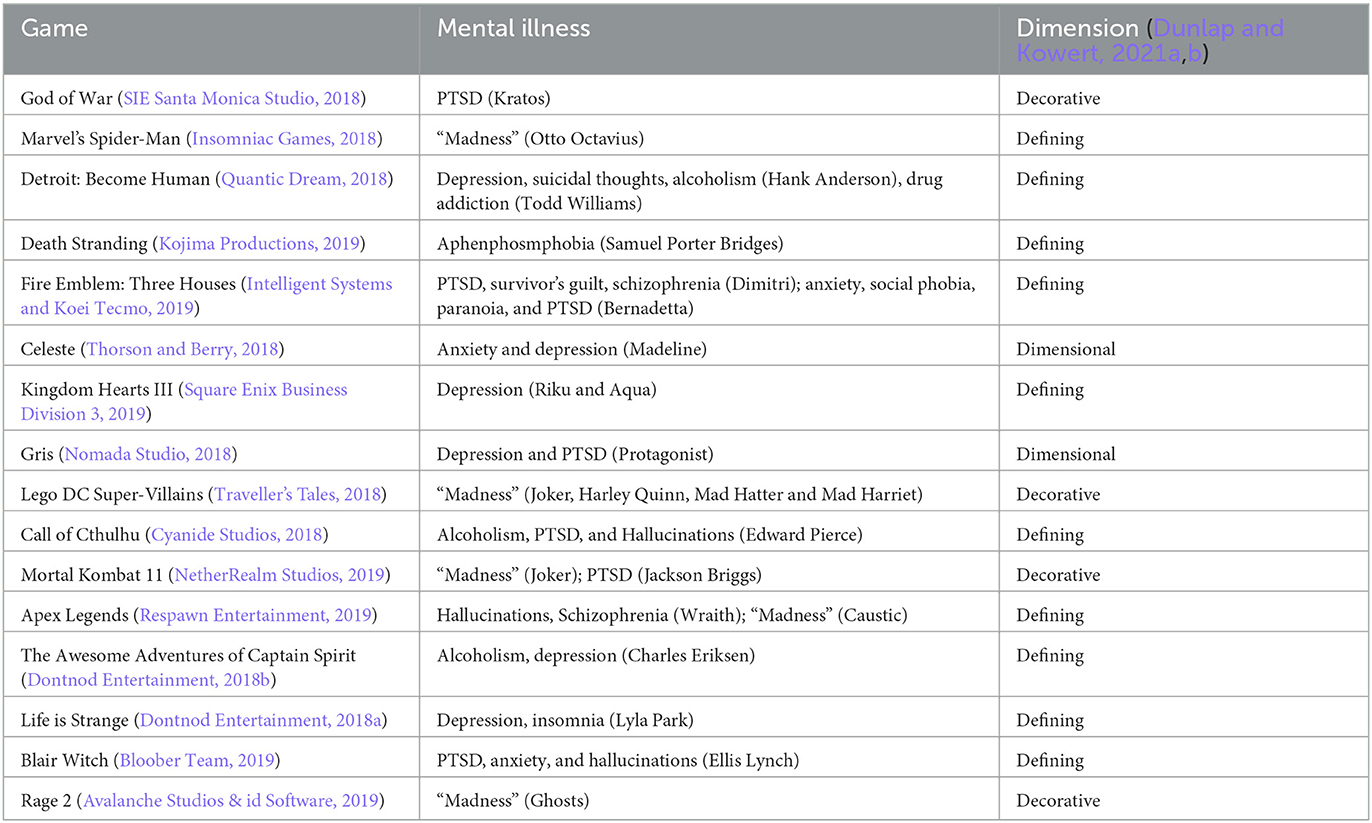

A total of 16 of the 74 games, hence every fourth game, dealt with MI. Within those games, there are 24 characters affected by MI. One character appears in two individual games, and one is a homogeneous group of characters. The majority of the characters affected by MI in the sample are playable. Of these characters, half assume central roles, one-third are protagonists, and three function as side characters and antagonists. Therefore, characters affected by MI in the games analyzed play an essential role in the game. However, they are not in the center of the story for the most part. Neurotic and stress disorders, such as anxiety (n = 3) and post-traumatic stress disorder (n = 6), as well as affective disorders, such as depression (n = 7), occur most frequently. However, almost one-third of the mental illnesses identified in the sample could not be categorized. Within the context of those games, those characters are affected by “madness.” In every fourth game analyzed, not only the characters but also the environment and the gameplay represented the illness. Most games (n = 19) do not include any form of professional treatment. Three games occur in a mental hospital; two address medication, and one mentions a character in therapy. In the context of the category system of Dunlap and Kowert, most games (n = 10) include a defining representation of MI. Table 3 lists all games and characters affected by MI in the sample.

Two games include a dimensional representation of MI: Celeste (2018) and Gris (2018), both published by independent game developers. Celeste is a single-player platform game following a young woman called Madeline, who suffers from depression and anxiety. She is on a quest to climb a mountain called Celeste to overcome her struggles. In Gris, a single-player platform adventure game, the player takes on the role of a nameless female protagonist dealing with trauma and grief after losing a loved one, as well as with post-traumatic stress disorder or depression. The game does not include spoken or written words. Instead, the entire story unfolds through visuals and music. Hence, there is much space left for individual interpretations.

The following results are limited to the findings essential to MI representation. Each layer of the video game analysis is part of the results as follows: The section on characters includes the layers of Character and Player, focusing on the characters personifying the illness, and the Representation layer, dealing with the connection between the primary goal of both games and MI. The Design and Aesthetic layer is part of the section on environment and atmosphere, as the design of the game world and the atmosphere surrounding it symbolize the illness-related experience. The section on mechanics includes the Context layer, including illness-related knowledge and advice in Celeste, and also mentions the Simulation layer, as overcoming obstacles in Jump'n'Run games is related to illness-related experiences.

5.1. Mental illness in characters

Both games represent MI through the antagonists. In Celeste, Badeline, a doppelganger or shadow of hers, represents Madeline's depression and anxiety. Their outer appearances only differ in terms of hair and eye colors. Badeline appears several times throughout the game, trying to keep Madeline from reaching the mountaintop. She does so by attacking and discouraging her and leaving obstacles in her way. Madeline herself is aware of the fact that the illness is a part of her. She expresses her insecurities and self-doubts: “But I can't escape myself. I'm literally fighting myself the entire way. Maybe this is all pointless” (Thorson and Berry, 2018). Hence, fighting Badeline feels like fighting against herself, which is not the solution to her suffering. However, later on, both work together and become stronger by combining their abilities. Through their teamwork, they eventually reach the top of Celeste. This transformation from antagonism to cooperation reflects the primary goal of the game in the context of MI: To not defeat Badeline, hence the illness, but rather to learn how to accept and live with it, as both are a part of her.

In Gris, a shape-shifting shadow represents the MI in question. It appears as a bird, a serpent, and the protagonist herself. As a bird, the shadow appears harmless, simply getting in the player's way. It attempts to push the protagonist back to keep the player from making progress in the game. As a serpent, however, the shadow threatens the protagonist's life. It chases her and attempts to devour her. Instead of giving up, the protagonist is able to take advantage of those disruptions, using them for her own progress. For instance, the pushing back by the bird-shaped shadow can help her reach platforms further away. When taking over the shape of the protagonist, the shadow reveals that it is an ever-present part of her. However, even though it seems inescapable and undefeatable, in the end, she can leave it behind and move on with her life.

In both games, the antagonists representing MI turn out to be not entirely evil but rather a part of the protagonists themselves. Both examples are portrayed as shadows of the character affected. On the one hand, a shadow symbolizes darkness and negativity. The illness is taking over a person's mind and removing all light, hence the positive emotions, leaving them with negativity. On the other hand, a shadow constantly follows a person and would not be visible if there was no light source. The shadow metaphor indicates that someone living with MI does not only experience negative feelings but can also have happiness in their lives as well.

5.2. Mental illness in the environment and atmosphere

Both games represent MI as part of the environment and atmosphere. In Celeste, Madeline's panic attacks become visual. The environment surrounding her and those immediately next to her disappears. The screen is overtaken by darkness, only disrupted by strands of Badeline's purple hair. An alteration of music and the controller vibrating evoke a feeling of discomfort. This intense sensation might give players a slight impression of the overwhelming and frightening feeling of a panic attack. In those moments, Madeline has the feeling of being transported to a place far away. Everything around her becomes blacked out as she can only focus on her panic attack. She expresses her discomfort to Theo, a friend she met on her journey, claiming she cannot breathe.

In Gris, this can be found throughout the game, as each level represents a stage of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. With each level, there is a shift in the landscape and the addition of a new color. At the beginning of the game, the protagonist arrives in a gray landscape full of ruins, where she also loses her voice. This place, with its absence of color, represents denial. The following level represents anger, occurring within a desert and adding red. Bargaining is situated in a forest, hence associated with the color green. Depression takes place in a deep sea and adds blue to the color palette of the game. The last color, yellow, is added in the acceptance stage. The protagonist moves through a setting that resembles a starry sky, where she finally regains her voice and can leave the whole place behind. The shift of the environment from the blooming forest to the dark, deep ocean symbolizes that grief and dealing with MI are not linear processes. People affected do not get better with each step. There might always be a new low, even after a phase of improvement. However, the end of the game encourages players to hope for better days instead of losing faith after a stage of depression. Similarly, in Celeste, when Madeline is close to the mountain top for the first time, she falls down. However, instead of giving up, she continues climbing up once again and eventually achieves her goal.

5.3. Mental illness in mechanics

Celeste not only gives an impression of what a panic attack might feel like, but also offers advice on how to deal with one. This advice does not only address people affected but also players in general who might witness a panic attack. The former is part of the gameplay in the form of a mini-game. Her friend Theo tries to help her overcome the panic attack by introducing her to a breathing technique. He asks her to imagine a feather in front of her, which she has to keep floating in the air with steady breaths. This method is supposed to help her relax and calm down. The mini-game includes a feather that the players must keep within a small, selected area. Concentration is required to keep the feather steady for a certain amount of time to complete this mini-game successfully. Players who suffer from panic attacks can adopt this method in real life. Besides that, the way Theo acts in this situation and supports Madeline is a positive example of how to aid somebody else experiencing a panic attack. Furthermore, it is essential to mention that the gameplay mechanics in both games focus on obstacles in the way and how to overcome them, which is a metaphor for dealing with MI.

6. Discussion and theoretical implication

The games in the qualitative analysis represent MI as the antagonist. At first glance, this reproduces existing negative portrayals of MI and those affected as dangerous and evil. However, in both games, the antagonists are revealed to be part of the protagonists themselves and end up supporting them to make progress in the game. In the end, both Celeste and Gris provide examples of MI representation where neither the characters affected nor the antagonists representing the illness are entirely evil or dangerous per se. Moreover, both protagonists can fight for themselves instead of being lonely, helpless, and needing rescue from others. This more positive perspective, similar to the example of the hallucinations in Hellblade, might contribute to overcoming stereotypical depictions in video games.

In contrast to abandoned psychological institutions as settings of horror games evoking negative attitudes toward professional medical treatment of MI, both games in the qualitative analysis offer a more positive approach, representing MI as part of the environment and atmosphere of the games. Celeste offers an immersive audiovisual experience of a panic attack's overbearing and terrifying sensation through the music, the interface, and the character's surroundings. Gris leads the player through the various stages of grief, each with a unique setting and atmosphere. This journey proves that grief and dealing with MI are not linear, with the person affected constantly improving. The examples in this study make illness-related experiences more understandable and empathically available for people unaffected by MI. Additionally, both games' outcomes disprove the common stereotypical notion that people affected by MI have little hope for recovery. Representing illness-related experiences through environmental and atmospheric elements might benefit the education of illness-related knowledge and lead to more empathy toward those affected.

The mini-game, including the feather as a breathing technique in Celeste, serves as a way to represent MI or, rather, cope with it as part of the gameplay. The game advises using this technique when experiencing a panic attack and demonstrates and manifests it due to the mini-game aspect. Implementing this advice in the gameplay might increase the chances of players remembering it when they experience a panic attack themselves in real life or witness someone else who could benefit from it. For future research, players affected by MI should be consulted to validate the effectiveness of the advice on mental health found in video games.

Both examples in this study are games developed by independent game studios; however, they have had substantial commercial success, reaching a broad audience of players. For example, no mental health professionals or similar experts were part of the development process in Celeste. However, the developer herself said in an interview that she is affected by anxiety and depression. Since MI is not supposed to be the game's main focus, the developers decided against consulting mental health professionals in the development process. Instead, they used their first-hand experience of being affected (Grayson, 2018). In Gris, however, the developers did consult a psychiatrist to discuss the topics of grief and depression within the game (Sanchez, 2019). Therefore, the dimensional representation of MI in both games lacking any stereotypization or stigmatization might be due to the expertise on the topic, whether through professional knowledge or first-hand experience.

Based on these findings, some significant aspects for the development of games including MI can be drawn that overcome stereotypical and stigmatizing representations and might be beneficial for those affected:

1. Representing MI through utterly evil characters with the ultimate goal of defeating them should be avoided. Characters affected learning how to accept their condition and not considering it their enemy should be portrayed instead.

2. Solely depicting negative effects and struggles deprived of MI should be resisted. Insights on positive symptoms (e.g., the beauty of some hallucinations in Hellblade) might lead to a more dimensional representation.

3. Representing illness-related experiences and emotions through the environment and atmosphere of the game might lead to more empathy for those affected.

4. Including advice for people affected by MI to adapt in real life (e.g., the feather mini-game as a breathing technique in Celeste) or positive examples of supporting those affected might be beneficial.

5. Expertise in MI (e.g., own experience, people affected, or mental health professionals) should be consulted during the development process.

7. Conclusion and limitations

In conclusion, MI can be a defining element in many video games dealing with such. However, their representation often lacks depth. For example, of the 24 affected game characters in this analysis, only two were represented beyond the surface and from multiple perspectives. Video games do have the potential to be beneficial for people affected by MI or those who are not. For those affected, it might provide opportunities to identify with game characters that have to deal with the same condition without being associated with negative stereotypes and stigmatization. Moreover, game elements such as the feather mini-game in Celeste offer advice that players might adapt to real life. In addition, representing MI not only through characters but also as part of the environment and gameplay might lead to people being more sympathetic about what it feels like to live with such disorders and how to interact respectfully with those affected. Experts in MI should be consulted in the development process to provide progressive and dimensional representations. This contribution provides aspects for consideration when representing MI in video games to provide more dimensional and empathetic portrayals beyond reproducing stigmatizing and stereotyping images of those affected. Additionally, the illness-related category system for this study's qualitative video game analysis is adaptable for further research on MI representation in video games.

However, this study focuses on viral games within a limited period. More recent games should be considered for future research, as the video game market is ever-expanding and evolving. The sample is also limited in terms of popularity. There could be more progressive and destigmatizing representations from other independent developers that are lesser known. Hence, future research should focus more on examining less popular games. Nonetheless, the games analyzed in this study are significant examples of dimensional representations of MI suitable as models for the development of games in the future.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

University of Rostock has established an institutional membership agreement for open access publishing with Frontiers.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anderson, S. L. (2020). Portraying mental illness in video games: exploratory case studies for improving interactive depictions. Loading 21, 20–33. doi: 10.7202/1071449ar

Avalanche Studios & id Software (2019). Rage 2 [Video game]. Stockholm; Richardson, TX: Bethesda Softworks.

Buday, J., Neumann, M., Heidingerova, J., Michalec, J., Podgorná, G., Mareš, et al. (2022). Depictions of mental illness and psychiatry in popular video games over the last 20 years. Front. Psychiatry. 13, 7992. doi: 10.3389./fpsyt.2022.967992

Dontnod Entertainment. (2018b). The Awesome Adventures of Captain Spirit [Video game]. Paris: Square Enix.

Dunlap, K. (2018). Representation of mental illness in video games. Proceedings of the 2018 Connected Learning Summit, 77-86.

Dunlap, K., and Kowert, R. (2021a). Mental health in 3D: a dimensional model of mental illness representation in digital games. Loading 24, 122–133. doi: 10.7202/1084842ar

Dunlap, K., and Kowert, R. (2021b). The monstrosity of stigma: mental health representation in video games. Proceedings from the 17th annual Tampere University Game Research Lab spring Seminar, April.

Edney, D. (2004). Mass Media and Mental Illness: A Literature Review. Canadian Mental Health Association. Available online at: https://ontario.cmha.ca/wp-content/files/2012/07/mass_media.pdf (accessed March 06, 2023).

Eichner, S. (2017). “Videospielanalyse,” in Qualitative Medienforschung: ein Handbuch, ed. L. Mikos and C. Wegener (Konstanz: UVK Verlagsgesellschaft mbH), 524-533.

Ferrari, M., McIlwaine, S. V., Jordan, G., Shah, J. L., Lal, S., and Iyer, S. N. (2019). gaming with stigma: analysis of messages about mental illnesses in video games. JMIR Mental Health 5, 1–14. doi: 10.2196/12418

Fordham, J., and Ball, C. (2019). Framing mental health within digital games: an exploratory case study of hellblade. JMIR Mental Health 6, 4. doi: 10.2196/12432

Grayson, N. (2018). Celeste Taught Fans And Its Own Creator To Take Better Care of Themselves. Kotaku. Available online at: https://kotaku.com/celeste-taught-fans-and-its-own-creator-to-take-better-1825305692 (accessed December 29, 2022).

Insomniac Games. (2018). Marvel's Spider-Man [Video game]. Burbank, CA: Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Intelligent Systems and Koei Tecmo. (2019). Fire Emblem: Three Houses [Video game]. Kyōto: Nintendo.

Jorm, A. (2000). Mental health literacy: public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry 5, 396–401. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.5.396

Lindsey, P. (2014). Gaming's Favorite Villain is Mental Illness, and this Needs to Stop. Polygon. Available online at: https://www.polygon.com/2014/7/21/5923095/mental-health-gaming-silent-hill (accessed December 29, 2022).

Morris, G., and Forrest, R. (2013). Wham, Sock, Kapow! Can Batman defeat his biggest foe yet and combat mental health discrimination? An exploration of the video games industry and its potential for health promotion. J. Psychiatric Mental Health Nurs. 20, 752–760. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12055

Neitzel, B. (2012). “Involvierungsstrategien des computerspiels,” in Theorien des Computerspiels zur Einführung, ed. M. Hagner, I, Kerner and D. Thomä (Hamburg: Junius Verlag), 75-103.

NetherRealm Studios. (2019). Mortal Kombat 11 [Video game]. Chicago, IL: Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment.

Newzoo (2022). Global Games Market Report. Available online at: https://newzoo.com/global-games-market-reports?utm_campaign=GGMR%202022andutm_source=ppcandutm_content=product%20pageandutm_term=newzoo%20gaming%20report%202022andutm_campaign=Games+Market+Report+Product+Pageandutm_source=adwordsandutm_medium=ppcandhsa_acc=3787860576andhsa_cam=17123497160andhsa_grp=140070146110andhsa_ad=595876740380andhsa_src=gandhsa_tgt=kwd-1677030942239andhsa_kw=newzoo%20gaming%20report%202022andhsa_mt=bandhsa_net=adwordsandhsa_ver=3andgclid=CjwKCAiAqt-dBhBcEiwATw-ggIGfieDmF3K9rs1hSK68GgXfzc9VqEYXlY1HXA2rlW2hz7-e5uOfZBoCNOQQAvD_BwE (accessed January 13, 2023).

Prommer, E., and Linke, C. (2017). “Codierung,” in Qualitative Medienforschung: ein Handbuch, ed. L. Mikos and C. Wegener (Konstanz: UVK Verlagsgesellschaft mbH), 447-457.

Runzheimer, B. (2020). “First person mental illness: digitale geisteskrankheit als immersive selbsterfahrung,“ in Krankheit in Digitalen Spielen: Interdisziplinäre Betrachtungen, eds A. Görgen and S. H. Simond (Bielefeld: transcript Verlag),145–162.

Ryan, M. (2001). Beyond myth and metaphor—The case of narrative in digital media. Int. J. Comp. Game Res. 1, 1–17. Available online at: https://gamestudies.org/0101/ryan/

Sanchez, A. (2019). Recovering Hearts: The Games Challenging Mental Health Stigmas. EGM. Available online at: https://egmnow.com/recovering-hearts-the-games-challenging-mental-health-stigmas/ (accessed January 09, 2023).

Scherr, S. (2019). “Psychische Krankheiten in der Gesellschaft und in den Medien,” in Handbuch der Gesundheitskommunikation, ed. C. Rossmann and M. Hastall (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien), 579-589.

Schlote, E., and Major, A. (2021). Playing with mental issues—Entertaining video games as a means for mental health education? Dig. Cult. Edu. 2, 94–110. Available online at: https://www.digitalcultureandeducation.com/volume-13-2

Shapiro, S., and Rotter, M. (2016). Graphic depictions: portrayals of mental illness in video games. J. Forens. Sci. 6, 1592–1595. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.13214

SIE Santa Monica Studio. (2018). God of War [Video game]. Los Angeles, CA: Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Traveller's Tales. (2018). Lego DC Super-Villains [Video game]. Knutsford: Warner Bros Interactive Entertainment.

World Health Organization (2022). Mental Disorders. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders (accessed January 13, 2023).

Keywords: video games, mental illness, representation, stigmatization, independent developers, depression, anxiety, dimensional representation

Citation: Kasdorf R (2023) Representation of mental illness in video games beyond stigmatization. Front. Hum. Dyn. 5:1155821. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2023.1155821

Received: 31 January 2023; Accepted: 04 August 2023;

Published: 01 September 2023.

Edited by:

Marko Siitonen, University of Jyväskylä, FinlandCopyright © 2023 Kasdorf. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ruth Kasdorf, cnV0aC5rYXNkb3JmQHVuaS1yb3N0b2NrLmRl

Ruth Kasdorf

Ruth Kasdorf