- School of Public Policy and Administration, Faculty of Liberal Arts & Professional Studies, York University, Toronto, ON, Canada

It is undeniable that forced migration and displacement is a “weapon of war.” To understand the ever-escalating refugee crisis in the world today and how it might be addressed, it is necessary to examine its “root cause(s).” Organized political violence in the form of either war or protracted armed conflict or oppressive dictatorial authoritarianism or totalitarianism are the prime drivers of forced migration and displacement in the world today. The most recent statistics on the world's forcibly displaced demonstrates their direct correlation to war and protracted armed conflict. The vast bulk of the world's forcibly displaced come from war torn countries. What is too often ignored in the academic literature on refugees and forced migration is that civilian non-combatants are often used as “weapons of war.” Mary Kaldor's “new wars” thesis is premised on the notion that wars and protracted armed conflicts defy solution because it is in the interest of the opposing combatants to continue the fighting, consequently, wars are characterized as “endless.” This has obvious implications for the continuous increase in the number of forced migrants in the world today. And, further, the “new wars” thesis postulates that civilian non-combatants are deliberately targeted during protracted armed conflicts or wars. Kelly Greenhill has presented evidence that “coercive engineered migration” is utilized to a State's advantage over another State. The weaponization of civilian non-combatants is a trigger for mass forced migration. Three recent cases dealing with genocide are offered as illustrations: Bosnia; Rwanda; and the Syria Civil War, with the Sieges at Homs and Aleppo. The article concludes with the consideration of the “endless cycle of war” that includes forced migration, smuggling, human trafficking, and other international crimes such as dealing in drugs and arms. All these elements are inter-connected and feed off each other and to be able to break this “endless cycle of war,” there must be a concerted and simultaneous effort to address all these things together. Only by doing so can we ever hope to achieve a “sustainable peace” and thereby end the use and abuse of forced migration and displacement as a “weapon of war.”

Introduction

The relevance and significance of forced migration and displacement as a “weapon of war” is simply undeniable (Cambridge Dictionary, 2022; Weaponize, 2022). A serious examination of this subject is certainly essential to an overall understanding of mass forced displacement. Yet, remarkably, it is too often ignored when considering the field of refugee and forced migration studies. To understand the seemingly ever escalating “refugee crisis” in the world today and how it might be addressed, one must first turn to examining its root cause(s). Organized political violence, whether in the form of either war or protracted armed conflict and either oppressive dictatorial authoritarianism or, worse still, totalitarianism, are the prime drivers of forced migration and displacement in the world today (Oxford Learner's Dictionaries, 2023a,b). It is when a person's most fundamental human rights and dignity are violated and in the process their life, liberty, and security are trampled or threatened will a person seek to find refuge. Refugees are not seeking adventure, an opportunity to better their job prospects or standard of living, or to obtain a better education to enhance or to better their life prospects, rather, they are seeking protection from persecution and affronts to their human dignity. People who are forced to flee their homes do not do so willingly, but because they fear severe harm that can amount to persecution.

Without a proper and accurate diagnosis of the problem, it is virtually impossible to find an appropriate remedy that can result in a viable solution. To resolve the world's refugee crisis, or crises, and in the process save millions of people from untold hardship and misery and possibly even their lives, it is evident that what needs to be done is to address its principal root cause(s), which are war and/or protracted armed conflict (ICRC, 2008, 2022a,b; Amnesty International, 2022). An extraordinary challenge, indeed, but no less so for ending poverty, achieving gender equality, tackling climate change, the provision of quality education for all, reducing inequalities, or achieving any and all of the United Nation's 17 Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 (United Nations, 2022). The key here it seems is whether one believes that it is even possible to do so (Mitchell, 2002; Long, 2014; Time, 2015; Bellamy, 2019; Saeedi, 2020).

Subsections: outline of the argument

War and protracted armed conflict are, of course, synonymous with forced displacement. In fact, war, typically, mass produces refugees. This is so prevalent and fundamental, that is, that extreme organized political violence produces mass forced displacement, that it must be a basic sociological principle. It is self-evident that civilians cannot live within a “war zone” for the obvious reason that they do not know whether they will be able to survive and their existence, shorn of the essentials of life, is made miserable and unbearable, as well as highly stressful and precarious. Accordingly, the first Section of this paper makes the statistical case that the forcibly displaced, especially refugees, are highly correlated to wars and protracted armed conflict. It also considers the scope and nature of forced migration in the world today. The vast bulk of the world's forced migrants come from war torn countries that are characterized by severe loss of life and with physical and mental injuries, the perpetration of serious international crimes, vast destruction of infrastructure and buildings, and mass forced migration or displacement.

The second section of this paper considers whether forced displacement in situations of war or protracted armed conflict is a consequence of the extreme organized political violence or is it deliberate and employed as a “weapon of war” to achieve a military victory. It is important to bear in mind that the so-called “new wars” are described as protracted and/or “endless”. Mary Kaldor points out that a feature of this new warfare is that it is not in the interest of the opposing sides to end the conflict and that, indeed, civilian non-combatants are being deliberately targeted, which is a war crime. This has obvious implications for those who study forced migration and displacement. If wars are “endless” then so too are the mass forced displacements of persons from those States that are embroiled in war and protracted armed conflicts.

Kelly Greenhill has argued that forced migrants are used as “weapons of war”. “Coercive engineered migration”, Greenhill argues, are exercised as a strategy to gain political, military, and economic concessions from their adversaries (Greenhill, 2010). This implies that within a war setting forced migration and displacement are strategically employed to weaken their opponents and to gain the upper hand and to aid in achieving tactical and strategic military victory. Myriad examples are provided of how coercive engineered migrations have been employed by States to advance their interests in different contexts, whether in war or in peace.

When civilian non-combatants are weaponized in the context of war or protracted armed conflict, it is a deliberate effort to gain outright military advantage to obtain, ultimately, military victory. Weaponizing civilian non-combatants will inevitably trigger mass forced displacement. Ultimately, as both Kaldor and Greenhill assert, weaponizing civilian non-combatants perpetuates the political organized violence for the benefit of those engaged in the protracted armed conflict or war (Simeon and van Sliedregt, 2019).

The third section considers three noted recent cases of genocide: the Bosnia Genocide, Rwandan Genocide, and the Syrian Civil War, with the sieges at Homs and Aleppo, which are often described as genocidal. Undoubtedly, genocide is likely the ultimate driver of forced migration. Anyone who knows that they would be subject to murder due to their individual race, ethnicity, religion, or political beliefs will seek asylum elsewhere as soon as possible. While the estimates vary, the Rwandan Genocide saw an estimated 800,000 people killed in about 100 days (University of Minnesota, 2022). Likewise, the Syrian Civil War death tolls vary with estimates ranging from more than 350,000 to over 600,000 people killed over the 11 years of this armed conflict and it has resulted in over 5.6 million people who have fled their country to seek asylum elsewhere (Greenhill, 2012; BBC News, 2021a; Reliefweb, 2022a). All three genocides are known for their brutality and their use of “ethnic cleansing.”

The article concludes with a consideration of the endless cycle of war and protracted armed conflict and the escalating generation of forced migrants. What is called for to break this perpetual cycle of war, forced displacement, smuggling, and in its deviant form, human trafficking, and the illicit arms and drug trades, that are ingrained and integral to the perpetual cycle of war and protracted armed conflict, is to generate a global consensus that prohibits warfare in all its forms and manifestations, while simultaneously eradicating international organized crime and the trafficking in humans, drugs, and arms. This should then all but eradicate the “weaponization” of forced migration and displacement. The use and abuse of refugees and other forced migrants should not be allowed to persist and needs to be drawn to an end. To do so is not an impossibility. But it does require a firm commitment and dedication to the fundamental human right to peace and that organized political violence within and among States is intolerable and a heinous crime in and of itself. With the full realization, acceptance, and practice that the only way to resolve differences between and among States and their societies and peoples is through peaceful means and to the mutual benefit of all. The achievement of such a “sustainable peace” would, of course, require nothing short of a fundamental transformation of the present world order and the basis of the essential transactions in its human relations.

The principal cause of forced migration and displacement in the world today

The fundamental scope and nature of forced migration and displacement

It is absolutely critical to start with a clear understanding of the scope and fundamental nature of forced migration and displacement in the world today (Forced Migration Learning Module, 2022; IFRC, 2022; Reliefweb, 2022b). The situation is far from stable, and it is escalating at a rapid rate year over year. UNHCR's Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2021, states that “above one per cent of the world's population—or 1 in 88 people—were forcibly displaced at the end of 2021. This compares with 1 in 167 at the end of 2012” (UNHCR, 2022a).

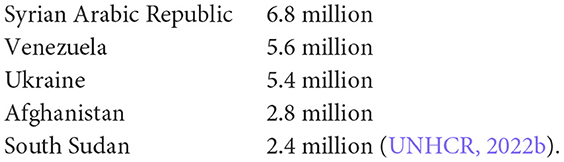

The UNHCR estimates that the total number of persons who are forcibly displaced in the world today stands at more than 103 million (UNHCR, 2022b). This figure, by mid-2022, could be broken down as 53.2 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), 32.5 million refugees, 4.9 million asylum seekers, and 5.3 million people in need of international protection (UNHCR, 2022b). It is also important to note that 72 percent of the world's refugees come from just five countries.

It is also worth noting that the UNHCR estimates that by the end of 2021 that 36.5 million (41%) of the world's forcibly displaced people were children who were below the age of 18 years of age (UNHCR, 2022b). And that fully 74 percent of the world's refugees and others in need of international protection were being hosted in low- and middle-income countries (UNHCR, 2022b).

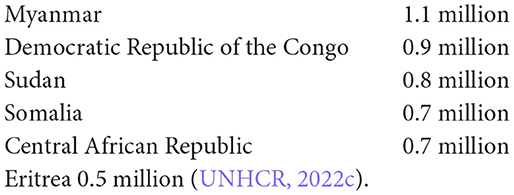

What is equally revealing is the next six source countries for the world's forcibly displaced, according to the UNHCR estimates for the end of 2021, include:

Here again, it is evident that all these countries have been engaged in protracted armed conflict for decades. Hence, the top 11 refugee producing countries in the world account for some 83 percent of the world's refugees (UNHCR, 2022c). These sobering statistics clearly underscore the close relationship between war and asylum.

It stands to reason that no one can be reasonably expected to be able to live within a “conflict zone” or “war zone” without water, food, shelter, medicine, and the other necessities of life. Nonetheless, many people and families are trapped and cannot escape these horrifying conditions. A recent study by the international non-governmental organization, Save the Children, reported that there has been a 20 percent increase of the number of children living in war zones over the last decade (Kamay et al., 2021; Save the Children, 2021).

These statistics, of course, increased significantly following Russia's illegal and unprovoked full invasion of Ukraine that commenced on February 24, 2022 (Jacobson, 2022; Kirby, 2022; Milanovic, 2022; BBC News, 2023).1 The United Nations estimates that there are over 11 million people who have fled their homes as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine: 5.1 million have left Ukraine to go to neighboring countries; and 6.5 million are internally displaced within Ukraine (BBC News, 2022c).

What is evident from these stark statistics is that the bulk of those who are forcibly displaced in the world today come from countries that are torn by protracted armed conflict or war (UNHCR, 2021b). This is most evident from the deadly conflict that is raging in Ukraine but also the protracted armed conflicts in Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan, and the low intensity conflict ongoing in Myanmar. Venezuela is a special case that has faced social, economic, and political upheaval and the serious human rights abuses of the government of Nicolás Maduro and its security forces that has led to people being forced to flee for their lives to other neighboring countries throughout South and Central America and beyond (Human Rights Watch World Report, 2021; United States Institute of Peace, 2022).

UNHCR's Mid-Year Trends report for 2021, stated,

The number of active conflicts reached a record high in 2020, more than at any time since 1945, despite the COVID-19 pandemic and calls from the UN for a global ceasefire. In early 2021, consistent with 2020, most armed conflicts remained internal in their essence. Yet many of these situations have become increasingly internationalized, with interventions from a growing number of regional and global powers (UNHCR, 2021a).

Using the Uppsala Conflict Data Program's definition of war as a “state-based conflict or dyad which reaches at least 1,000 battle-related deaths in a specific calendar year,” the World Population Review identifies 22 states that are at war (World Population Review, 2022). This includes the Russia-Ukraine War that commenced, in its current phase, as already noted, on February 24, 2022 (World Population Review, 2022). All the countries listed in the World Population Review are experiencing mass forced displacements, as one might expect.

The war in Ukraine displays all the elements typically found in war: massive, forced displacement; atrocity crimes or the most serious international crimes; and a tremendous loss of life and destruction of property. The United Nations has estimated that there are more than 11 million people who have been displaced in the Ukraine since Russia's unprovoked invasion of Ukraine (RFE/RL, 2022). The rapidity and the massive numbers of persons displaced in the Ukraine is unprecedented since the end of the Second World War (UNHCR Global Focus, 2023). Human Rights Watch is documenting war crimes that are being perpetrated by Russian military forces in the Ukraine (Gorbunova, 2022; Human Rights Watch, 2022). By mid-February 2023, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights reported that there were 18,955 civilian casualties because of the war in Ukraine, 7,199 killed, and 11,756 injured (United Nations, 2023). The enormous destruction of infrastructure and buildings is in the order of $60 billion as of mid-April 2022, with an estimated loss to its economy in the form of direct and indirect losses of an estimated $560 billion (Falk, 2022; Lawder and Gallagher, 2022; Uren, 2022). Indeed, some have labeled what is happening in the Ukraine is nothing less than genocide (Beauchamp, 2022; Chase, 2022; Gollom, 2022; Krause-Jackson, 2022).

Forced displacement in situations of war or protracted armed conflict: deliberate or consequential?

It is trite to note that there are different types of war (Speier, 1941; Morris, 2017; Simpson, 2017; Frankel, 2022; Modern Warfare, 2022). Indeed, if one looks at the nature of war throughout history one could easily discern that warfare has progressed with technological advancement and ingenuity (Farley, 2016; Barr, 2020). In addition, it is likely fair to say that wars have been always fought brutally with the underlying warriors' ethos of either “kill or be killed” (French, 2001; Lazar, 2022; US Army, 2022).

Kaldor has argued for a “new wars” thesis that is premised on the social relations of warfare that is associated with globalization and the disintegration of states such as the Balkan Wars in the 1990s or in the Great African War, 1998–2003 (Kaldor, 2005). Kaldor describes the “new wars” in the following terms:

… wars that are fought by networks of state and non-state actors, often without uniforms—sometimes they have distinctive signs, like crosses or Ray-Ban sunglasses as in the case of the Croatian militia in Bosnia Herzegovina; wars where battles are rare and where most violence is directed against civilians as a consequence of counter-insurgency tactics or ethnic cleansing; wars where taxation is falling and war finance consists of loot and pillage, illegal trading and other war-generated revenue; wars where the distinctions between combatant and non-combatant, legitimate violence and criminality are all breaking down; wars that exacerbate the disintegration of the state—declines in GDP, loss of tax revenue, loss of legitimacy, etc. Above all, these wars construct new sectarian identities (religious, ethnic, or tribal) that undermine the sense of a shared political community. Indeed, this could be considered the purpose of these wars. They recreate the sense of political community along new divisive lines through the manufacture of fear and hate (Kaldor, 2005, p. 492–493).

The underlying logic of the “new war” thesis and what it means for forced displacement

It is important to emphasize a number of things with respect to Kaldor's “new war” thesis and its implications for forced displacement. Kaldor argues that “new wars” are better characterized by violence directed against civilian non-combatants rather than in battles between combatants, ethnic cleansing, the state's tax revenue is in steep decline and war financing is based on illegal trading and the distinction between legitimate violence and criminality has broken down. What are constructed are new sectarian identities that create a shared sense of community that is “manufactured through fear and hatred” (Kaldor, 2005). Each of these elements are either a direct cause or contribute to people seeking to flee their homes if they happen to be caught in a “war zone” or “area of armed conflict.” The deliberate targeting of civilians is, of course, a war crime. Likewise, ethnic cleansing is either a crime against humanity and/or the crime of genocide (Rikhof, 2022). The deterioration of State services and, especially, the breakdown of law and order and the severe rise in criminality, as a consequence, further contribute to the conditions that lead people to seek refuge elsewhere.

According to Kaldor's “new war” thesis, wars are like a “social condition” or a “mutual enterprise” and that the opposing forces gain by fighting rather than by winning or losing (Kaldor, 2017). She argues that warfare in the post-Cold War era is characterized by the following:

- violence between varying combinations of state and non-state networks;

- fighting in the name of identity politics as opposed to ideology;

- attempts to achieve political, rather than physical, control of the population through fear and terror;

- conflict financed not necessarily through the state, but through other predatory means that seek the continuation of violence (Kaldor, 2012; New Wars, 2022).

Another characteristic of the new wars, according to Kaldor, that is worth emphasizing is that wars are protracted and/or “endless.” She indicates that this is because it is simply not in the interest of the opposing sides to bring the conflict to an end. If war and armed conflicts mass produce forced displacement, that is, refugees and IDPs, then protracted armed conflicts and endless wars will be constantly producing forced displacement and refugees. Witness what is happening in Ukraine, Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Yemen, and other countries that are experiencing seemingly endless wars (Sen Nag, 2019; Russo-Ukraine War, 2022; Sullivan, 2022).

In this regard, it is important to keep in mind Greenhill's work on the use of migration as a “weapon of war.” In her well-known book, Weapons of Mass Migration: Forced Displacement, Coercion, and Foreign Policy, she identifies 50 attempts at what she calls “coercive engineered migration (or migration engineered coercion)” and finds that over half achieved at least some of their objectives (Greenhill, 2010).

In Greenhill's terms, “In coercive engineered migration, by contrast, costs are inflicted through the threat and use of human demographic bombs to achieve political goals that would be utterly unattainable through military means” (Greenhill, 2010).

Greenhill argues that there are two ways in which the would-be coercers can impose costs on their targets:

(1) Through straight forward threats to overwhelm the physical or political capacity of a target state to accommodate an influx;

(2) Through a kind of norms-enhanced political blackmail predicated on exploitation of the heterogeneity of interests that frequently exists in politics (Greenhill, 2010).

Greenhill defines coercive engineered migration as “those cross-border population movements that are deliberately created or manipulated to induce political, military and/or economic concessions from a target state or states” (Greenhill, 2010, p. 13). This is a particular subset of a broader class of events that Greenhill identifies as “strategic engineered migration.” These are then classified according to their objectives as:

Dispossessive engineered migrations

The principal objective is the appropriation of the territory or property of another group or groups of the elimination of the said group(s) as a threat to the ethnopolitical or economic dominance of those engineering the out migration. This type of “strategic engineered migration” includes ethnic cleansing.

Exportive engineered migration

The objective here is to fortify a domestic political position (by expelling political dissidents and other domestic adversaries) or to discomfit or to destabilize foreign governments.

Militarized engineered migrations

These types of migration are conducted usually during an armed conflict to gain military advantage over an adversary or to enhance one's own force structure, via the acquisition of additional personnel or resources (Greenhill, 2010, p. 14).

Greenhill presents a number of examples of “strategic engineered migrations” that include the following:

In 1972 Idi Amin expelled all Asians from Uganda and some 50,000 of those were British passport holders. At the time, Idi Amin was trying to persuade the British government to halt their withdrawal of military assistance to Uganda. Greenhill notes that this was Amin's method of attempting to persuade the British government to maintain its military assistance to Uganda.

In 1981 Haitian refugees were making their way to the United States by boat. To stem the flow of these migrants U.S. President Ronald Reagan, at the time, concluded an agreement with Baby Doc Duvalier, the US-Haiti Interdiction Agreement. Under the agreement all of those intercepted at sea could be returned to Haiti, after an initial screening for an asylum claim. Haiti agreed to keep outflows to a minimum. In return, the US provided financial assistance and more non-immigrant visas. In addition, off the record, it was agreed that the US would deemphasize human rights and would look the other way on graft and corruption in Haiti.

The Cuban Balsero Crisis or the Raft Exodus took place in 1994. Some 35,000 Cubans came to the United States on makeshift rafts. This occurred after rioting took place in Cuba and President Fidel Castro then announced that anyone could leave the country without hinderance. This was the largest exodus from Cuba since 1980 when some 125,000 people, including criminals, left the country after Castro opened the port of Mariel for 5 months (Britannica, 2022b). Naturally, this strained the capacity of the US immigration and resettlement system and its facilities (Britannica, 2022b). The Cuban Balsero Crisis led to US President Bill Clinton, fearing a mass exodus from Cuba, to order that all rafters captured at sea would be taken to the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base.

What can be concluded from these strategic engineered migrations?

All three examples of these strategic engineered migrations, which took place in a non-war setting, are being used by these States to leverage concessions from the target States involved. Idi Amin's expelling of Ugandan Asians to gain concessions from the British government in the form of not ending its military assistance. Given the dire country conditions in Haiti, people were seeking better life opportunities elsewhere. This outflow of migrants, precipitated, at least in part, by government policies, allowed Baby Doc Duvalier to seek to gain US concessions from President Ronald Reagan. In an effort to stem off those who are discontented and opposed to his regime, Fidel Castro allows those persons to flee Cuba and, in return, attempts to persuade its political adversary, the United States, to change its policies toward Cuba. In all three instances, the political leaders in each of these three States used their citizens, the putative refugees, for their own purposes and without due regard to these persons' situations within their own countries. The Idi Amin policy of forcibly expelling Asian Ugandans from their own country is the most blatant example. Use of the fear of mass influxes of asylum seekers to the United Kingdom and the United States and the political consequences of having to deal with such a massive intake of asylum seekers is, undoubtedly, no less a blatant case of “weaponizing asylum seekers” in order to motivate another State to negotiate positive terms in an effort to stem the flow of those seeking asylum in the UK and US.

The general point here is that strategic engineered migrations do not occur only in situations of war or protracted armed conflicts. They can also be used in non-war or non-conflict settings. And more to the point, this also illustrates that strategic engineered migrations are highly likely to be found in situations of war and armed conflict.

Weaponizing civilian non-combatants and the deliberate generation of mass forced migration

Any number of factors could combine that could result in people wanting to move to another location, including, immigrating abroad. Forced migration or displacement is always, of course, beyond the desire or choice of those who are so affected. In situations of war or armed conflict when people are deliberately attacked or forcibly removed from an area as part of a deliberate strategy or campaign to achieve a military victory or to acquire possession and/or to gain control of a territory is clearly contrary to international humanitarian law (ICRC, 2022c; UNHCR, 2022d). When civilian non-combatants are forcibly displaced with the intention of deliberately affecting another State in order to gain military advantage and/or to disadvantage that State then this is clearly an instance where the civilian population is being “weaponized” in the context a war or armed conflict (Amaro, 2021; Poznansky et al., 2022). This is hardly a new tactic in warfare, as evident in the use of civilians, including children, as human shields and who are subjected to rape, and torture as a deliberate and outright effort to win the war or armed conflict (Amnesty International, 2001; Jones, 2013; Sapiezynska, 2021; McKernan, 2022; Physicians for Human Rights, 2022; Schmitt, 2022; The Guardian Staff and Agencies, 2022). It is a means of demoralizing as well as to terrifying the population of a State in an effort to win the war or armed conflict. Such strategies, tactics, and methods are, of course, contrary to international humanitarian law and are, consequently, illegal. Under such circumstances, with the breakdown of law and order and civilians, who are being deliberately targeted for death and torture or extreme abuse and hardship, naturally, they will flee for their lives and seek refuge from the horrors of war and the armed conflict. The “weaponizing of civilian non-combatants” by means of the perpetration of the most serious international crimes is the trigger for the generation of mass forced displacement.

This is most evident when terrorism is employed in situations of war and armed conflict. In fact, terrorism has been found to be most prevalent in situations of war, armed conflict, and oppressive authoritarian regimes (Simeon, 2020). Moreover, terrorism, in these contexts, acts as an accelerant or catalyst to forced displacement or migration (Simeon, 2020). No one, of course, wants to live in a state of terror and, consequently, will seek asylum or refuge elsewhere.

Three cases of genocide: serious international crimes

Extreme organized political violence, in the form of war or protracted armed conflict, is the platform that produces the worst crimes imaginable such as “war crimes,” “crimes against humanity,” and “genocide.” These serious international crimes are the drivers of forced migration. Among all these serious international crimes, perhaps the most heinous is genocide (Amanpour, 2022) which “means any of the following acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group” (Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, 2022).

Three notorious cases of genocide are presented here to illustrate how serious international crimes, deliberately, are intended not only to eradicate groups of people but to instill severe fear and despair so as to induce people to flee their homes and, often, their countries. Consequently, people are forced to flee elsewhere in search of refuge from the serious international crime of genocide. This serves the perpetrators' desire to eradicate a group of people and gain their land, property, and possessions.

Yugoslav Wars 1991–2001—The Bosnia Genocide 1995

Described, at one time, as Europe's deadliest conflict since the end of the Second World War, prior to the present war in Ukraine, the Yugoslav Wars were marked with war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, ethnic cleansing, including large-scale systematic rape. The Bosnian Genocide was the first to be formally classified as such since World War II (Genocide in Bosnia, 2022). The estimate of the number of people killed was about 140,000. The wars in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Kosovo produced about 2.4 million refugees and two million internally displaced people (BBC News, 2022b; The Bosnian Genocide, 2022). The war in Ukraine has easily eclipsed these figures within only the first few months of the war. Genocide is also what has been used to describe what is taking place during the war in Ukraine (Wright, 2022). Sadly, there are too many striking similarities between the Yugoslav Wars and the war in Ukraine.

The Bosnian Genocide refers, more specifically, to the 1995 Srebrenica massacre that led to the killing of more than 8,000 Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) men and boys and the mass expulsion of 25,000–30,000 Bosniak civilians by the Army Republika Srpska (VRS) (The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2022).

In 2005 the US Congress passed a resolution that the Serbian policies of aggression and ethnic cleansing met the terms defining genocide (US Congress, 2022).

In 2016, the Bosnia Serb leader, Radovan Karadzic, the first President of the Republika Srpska, was found guilty of genocide in Srebrenica, war crimes, and crimes against humanity and sentenced to life imprisonment (History, 2009; BBC News, 2016b, 2019, 2022c,d; United Nations, 2019; Kleiderman, 2021).

Rwandan Genocide, 7 April to 15 July 1994

The Rwandan Civil War began in 1990 when the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a rebel group that was composed mostly of Tutsi refugees, invaded Northern Rwanda from its base in Uganda. Neither side was able to gain the upper hand and on August 4, 1993, the government of Rwanda signed the Arusha Accords with the RPF. However, when the President of Rwanda, Juvenal Habyarimana, was assassinated on April 6, 1994, the genocide started the next day (BBC News, 2019).

It has been estimated that up to 1.1 million people were killed in about 100 days that included Tutsi (the minority), some moderate Hutu, and Twa (BBC News, 2022a; Britannica, 2022a; GENOCIDE, 2022). The scale of the brutality of the genocide was alarming, but no country intervened to stop the killing. The slaughter took place with machetes and rifles, and it is estimated that some 250,000–500,000 women were raped during the genocide.

The RPF resumed the civil war and captured the government's territory ending the genocide. The RPF government then launched an offensive into Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) against the genocidaires who had relocated there. This started the First Congo War that resulted in an estimated 200,000 deaths (Des Forges, 1999).

Following the RPF victory, some two million Hutus fled to refugee camps outside the country. The refugee camps were squalid, and many died of disease, epidemics, cholera, and dysentery. The refugee camps were also attacked by the RPF who were targeting the Hutu militia. The refugees fled these camps, and the refugee camps were dismantled (Rwanda, 2022; Rwanda Genocide, 2022).

It has been estimated that as many as 10,000 people were killed per day and that about 70 percent of Tutsi population was killed and over 10 percent of the total Rwandan population (Bhalla, 2019). It is important to note that the UN International Day on the Reflection of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide is held every April 7th, the day that the genocide commenced (United Nations, 2003).

Syria Civil War (Siege of Homs 2011-14, Siege of Aleppo, 2012-16)

The Syrian civil war started with a peaceful protest of young people who took to the streets in the city of Daraa in March 2011 (Clover Films, 2017; BBC News, 2021b; Al Jazeera, 2022). It was part of a broader Arab Spring social media movement that swept North Africa and the Middle East (Stop Genocide Now, 2022a). The multi-sided civil war in Syria is being fought by the Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and various domestic and foreign forces. Iran, Russia, and Hezbollah support President Bashar al-Assad. The United States is leading an international coalition that is supporting the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Turkey has fought the SDF, ISIL [Islamic State of Iraq and Levant], and the Syrian government (Syrian Civil War, 2022).

The Syrian civil war has caused a major refugee crisis with millions of people being forcibly displaced in neighboring countries: Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt. There are an estimated 6.8 million people who have fled the country and another 6.7 million people who are internally displaced (Syria Refugee Crisis Explained, 2021). Again, the war in Ukraine has nearly exceeded these numbers of forcibly displaced in Syria within the first few months of the war.

The Siege of Homs, 2011–2014, lasted for 3 years and ended with the rebels being allowed to leave Homs and the Syrian government forces taking it over (Harding et al., 2012; Siege of Homs, 2016).

The Siege of Aleppo, 2012–2016, lasted for 4 years and ended the same way with the rebels being allowed to leave Aleppo and the Syrian government forces taking it over. Untold atrocities were alleged to have been committed by the Syrian government forces after taking control of the city (BBC News, 2016a; Vox, 2016; Syria, The Battle of Aleppo, 2022).

Moreover, the Syrian civil war has been characterized by mass atrocities that include war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide (Stop Genocide Now, 2022b). Over the course of this 11-year protracted armed conflict there have been an estimated 500,000 people who have been killed (Stop Genocide Now, 2022c).

Summary of these three cases of genocide: Yugoslav wars, Rwanda, and Syria

All are characterized by multiple actors, local and international, that were involved directly or indirectly in the situation of the armed conflicts or wars.

All are known for their brutality and their “atrocity crimes” that were perpetrated in the midst of the civil wars that pitted ethnic and religious groups against each other. The Yugoslav Wars, Rwanda, and Syria are all known for the commission of genocide. All these civil wars are also known for their “ethnic cleansing.”

All have mass produced exceptional numbers of people who are deliberately forcibly displaced, both as refugees and as internally displaced persons (IDPs).

Yugoslav Wars−2.4 million refugees; two million IDPs

Rwanda−1.1 million killed in 100 days and some two million refugees

Syria−6.8 million refugees; 6.7 million IDPs

Ukraine–6.1 million refugees; eight million IDPs (Associated Press, 2022)

All have had a tremendous impact on neighboring countries that not only provide refuge for those fleeing the fighting but more importantly the “atrocity crimes” that are taking place there but that result in serious political repercussions in some instances. Take Zaire, as a case in point, which led to the removal of President Mobutu Sese Seko and the renaming the country back to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (Smith, 2015; Mobutu Sese Seko, 2022).

Concluding reflections

A summary of the main findings

The main findings of this article can be summarized as follows:

It is evident from all the relevant statistics that refugees, and other forced migrants are integrally and causally linked to war and protracted armed conflict. This can be taken as a given—as a self-evident given—or sociological principle. Whenever there is a war or protracted armed conflict there will be mass forced migration and displacement.

The number of the world's forced migrants is escalating at a rapid pace and is at a historic high (UNHCR, 2023). The number of the world's forced migrants has increased to over one percent of the world's population. This does not augur well for the situation of the world's forcibly displaced.

Save the Children has reported that the number of the world's children who live in a war zone has increased by 20 percent over the last decade.

There are 22 States in the world today that are embroiled in war, and all are experiencing mass forced displacement.

In Mary Kalder's “new wars” thesis, she makes the point that as civilian non-combatants are frequently targeted for no good reason and, consequently, this amounts to a war crime. Civilian non-combatants are deliberately targeted to terrorize the population of the State as part of its strategy to achieve military victory.

Civilian non-combatants are “weaponized” in several ways such as rape, torture, and used as human shields. No one wants to be used as a “weapon of war,” so, consequently, this can serve as a trigger for mass forced displacement.

Kelly Greenhill argues that forced migrants can be used by one State against another in the form of human demographic bombs. Forced migrants are deliberately employed by States to further their interests regardless of its impact on the forced migrants' themselves.

Terrorism is most prevalent in situations of extreme organized violence such as wars, protracted armed conflict, and within authoritarian or totalitarian regimes. Terrorism serves as an accelerant or a catalyst for forced migration and displacement.

Genocide is a feature of many wars and protracted armed conflicts. This too can serve as a trigger for forced migration and displacement.

Final thoughts on the use and abuse of forced migrants as “weapons of war”

The mass production of refugees is a characteristic of modern warfare. Intrastate and internationalized armed conflicts tend to predominate, and it is within these types of conflicts that “atrocity crimes,” especially genocide, are most prevalent, given the intensity of the protracted armed conflict.

Dispossessive Engineered Migrations seem to be most evident within protracted armed conflicts. The purpose of the forced displacement is to remove designated groups, whether ethnic, racial, or religious based, away from a particular territory through “ethnic cleansing.” This is also evident with the siege of cities such as Homs and Aleppo in the Syrian civil war.

There are consequences from the mass production of refugees that creates political impacts for the neighboring and other hosting States and the international community as a whole. Consider the so-called refugee crisis that occurred in Europe in 2015 when Syrians on mass moved out of the refugee camps and started making their way to Europe and principally Germany (Betts and Collier, 2017). Likewise, with the Migrant Caravans traveling up through South and Central America to make their way to the US border. Inevitably, these are major political issues for the destination States but all the neighboring States and the States that are en route as well (Clementi, 2022).

There is at present a “perpetual cycle of organized political violence” or war and protracted armed conflict, that mass produces forced migrants, that, in turn, feeds the smuggling and human trafficking industries, which generates massive profits that are used to purchase weapons in the illicit arms trade. Wars and protracted armed conflict also feed the illicit drug trade, the huge profits generated are used to purchase the weapons that perpetuates wars and protracted armed conflicts that, in turn, then generate the mass forced displacement that again feeds the perpetual cycle of war and protracted armed conflict. These are the three most serious international organized crimes: trafficking in drugs, guns, and people (Transnational Organized Crime, 2022). All of these international organized crimes are connected inextricably to this perpetual cycle of war and protracted armed conflict that inevitably produce the “atrocity crimes,” including genocide, that, in turn, produces mass forced displacement that generates massive profits that are used to purchase weapons from the illicit arms trade to perpetuate the endless cycle of war and protracted armed conflict (Simeon, 2022, 2023).

How can this perpetual cycle of organized political violence or war, which produces the “atrocity crimes” and with it the mass production of forced displacement that then feeds international organized crimes, be broken? The short answer is to end wars or protracted armed conflicts. This has been on the public agenda for generations and there appears to be little progress in this regard (Horgan, 2022; United Nations, 2022a,b). What is perhaps needed is a four-pronged approach. To start, everyone must commit to ending war across all states, societies, and demand this from their governments. Secondly, there must be a commitment to eradicate the illicit international drug trade. At the same time, thirdly, there should be a coordinated effort to eradicate the illicit arms trade and, fourthly, human trafficking. This would contribute to bringing an end to the perpetual cycle of organized political violence or war or protracted armed conflict that would then drastically reduce mass forced displacement.2 War or protracted armed conflict is in the interest of a broad number of well entrenched and organized interests politically, economically, and socially. If those embedded and entrenched interests are not addressed in a simultaneous and consistent manner then the possibility of ending armed conflicts or wars will be extremely difficult, if not impossible.

The eradication of war has been on the public agenda since the late 19th Century, if not earlier (Abbs and Petrova, 2022; United Nations, 2022c). Although there has been some progress in this regard with the establishment, first, of the League of Nations following the First World War and the United Nations at the end of the Second World War, war and protracted armed conflict still plagues humankind. What is essential is a broad-based coalition of peace groups and a civilian peace movement that brings about an end to the use of political organized violence for resolving disputes or the blatant grab of territory and the resources of other States. In addition, it is also necessary for the international community to turn its attention in earnest to the three principal organized international crimes: drugs; guns; and human trafficking. All three of these organized international crimes are furthered by war and protracted armed conflict. The profits from the illicit trade in drugs and from human smuggling and trafficking are used, at least in part, to purchase weapons that perpetuate the ongoing wars in the world today.

If the world were to succeed in eradicating war and protracted armed conflict then the use and abuse of refugees as weapons of war would cease. Indeed, the vast majority of refugees in the world would not be produced and, consequently, the total number of refugees in the world would be dramatically reduced. What is required first and foremost is a commitment on everyone's part is to recognize that the “world peace” is possible and that it is not an impossible dream. It must begin with an acceptance that each and every one of us has a fundamental human right to be able to live in peace (Perry et al., 2017; United Nations General Assembly, 2022a). Peace is not only a human right, but it is an essential component of “human dignity” (United Nations, 2017). The exercise and enjoyment of everyone's human rights is premised on there being “peace.” Accordingly, it can be argued that war and protracted armed conflict are a violation of one's fundamental human right to peace and to the enjoyment of all other human rights and human dignity.

The legal use of force can be employed in certain situations such as is in self-defense. The exercise of force in any non-legal manner is a crime and offense against a person's or persons' individual or collective human rights and human dignity. When the “culture of peace” in the world is so accepted and ingrained that it becomes second nature and war, and armed conflict of any kind, will be considered intolerable and seen to be the worst possible serious international crimes (United Nations General Assembly, 2022b). This should then lead to a very different type of society that is premised on the peaceful settlement of disputes that leads to mutually beneficial outcomes for not only the parties involved but society, or the societies so engaged, and the global community as a whole. The achievement of such a “sustainable peace” will necessitate nothing less than the transformation of the world as we know it today (UN Peacebuilding Support Office, 2017; Caparini, 2022; UN Women, 2023). Without war and armed conflicts of any kind, this will go a long way in eradicating forced migration or displacement in the world today. The “weaponization” of forced migrants and/or those forcibly displaced will then become a thing of the past.

At the same time, the three major international criminal networks that prey off wars and armed conflict, those that are engaged in drug, arms, and human smuggling and trafficking, will also need to be addressed. These international criminal networks will need to be countered as it is in their interest to perpetuate wars and armed conflicts because it is “good for business” and supplies them a ready market and supply of forced migrants that they can exploit for profit. The use and abuse of forced migrants in war is matched with the exploitation of those who are forced to flee “war zones” seeking refuge in another State.

What is essential then for achieving a “sustainable peace” is to criminalize and, eventually, to eradicate extreme political violence in the form of war or armed conflict. This will also entail addressing the multi-billion-dollar international criminal organizations that deal in the illicit distribution and sale of drugs, arms, and the trafficking of human beings. Only then can we hope to achieve the vision of a world in perpetual peace that is fully sustainable.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Paul Kirby, “Why has Russia invaded Ukraine and what does Putin want?” BBC News, 17 April 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-56720589 (accessed April 24, 2022); Louis Jacobson, “Russia's Invasion of Ukraine is especially lawless. Could Putin be tried for war crimes?” POLITIFACT, March 1, 2022, https://www.politifact.com/article/2022/mar/02/Russia-invasion-Ukraine-especially-lawless/?utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Twitter#Echobox=1646259611 (accessed May 18, 2022); Marco Milanovic, “ICJ Indicates Provisional Measures Against Russia, in a Near Total Win for Ukraine; Russia Expelled from the Council of Europe,” EJIL: Talk! Blog of the European Journal of International Law, March 16, 2022, https://www.ejiltalk.org/icj-indicates-provisional-measures-against-russia-in-a-near-total-win-for-ukraine-russia-expelled-from-the-council-of-europe/ (accessed May 18, 2022); “Ukraine conflict: What war crimes has Russia been accused of?” BBC News, Russia-Ukraine war, 17 March 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-60690688 (accessed June 13, 2023).

2. ^Of course, this would not end the need for asylum or refugees in the world with those who would be fleeing oppressive authoritarian States and totalitarian States or those who are fleeing gender-based violence in the absence of State protection.

References

Abbs, L., and Petrova, M. G. (2022). How - and When - People Power can Advance Peace in Civil War. United States Institute of Peace. Available online at: https://www.usip.org/publications/2021/07/how-and-when-people-power-can-advance-peace-amid-civil-war (accessed May 24, 2023).

Al Jazeera (2022). “Syria's war explained from the beginning,” in Al Jazeera. Available online at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/4/14/syrias-war-explained-from-the-beginning (accessed May 5, 2022).

Amanpour, C. (2022). “The World's Most Heinous Crime,” in CNN - Scream Bloody Murder. Available online at: https://www.cnn.com/2008/WORLD/europe/11/20/sbm.overview/index.html (accessed May 19, 2022).

Amaro, S. (2021). “Belarus is accused of ‘weaponizing' migrants at the EU's border: Here is what you need to know,” in CNBC. Available online at: https://www.cnbc.com/2021/09/21/why-belarus-is-weaponizing-migrants-at-the-eus-border.html (accessed May 10, 2022).

Amnesty International (2001). Democratic Republic of Congo: Torture – a weapon of war against unarmed civilians, Amnesty International Press Release, London. Available online at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/afr620202001en.pdf (accessed May 9, 2022).

Amnesty International (2022). “Armed Conflict.” Available online at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/armed-conflict/ (accessed June 2, 2022).

Associated Press (2022). “Ukraine war pushes world total of displaced people over 100 million: UN,” in CBC. Available online at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/united-nations-displaced-people-1.6463101 (accessed May 23, 2022).

Barr, B. (2020). “How Has War Changed Since the Cold War,” in History of Yesterday. Available online at: https://historyofyesterday.com/how-has-war-changed-since-the-cold-war-c108c49c7f45 (accessed April 30, 2022).

BBC News (2016a). “Aleppo: Key dates in battle for strategic Syrian city,” in BBC News. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-38294488 (accessed May 5, 2022).

BBC News (2016b). “Radovan Karadzic: Former Bosnia Serb Leader,” in BBC News. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-19960285 (accessed May 5, 2022).

BBC News (2019). “Rwanda genocide: 100 days of slaughter,” in BBC News. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-26875506 (accessed May 4, 2022).

BBC News (2021a). “Why has the Syrian war lasted 11 years?” in BBC News. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-35806229 (accessed May 5, 2022).

BBC News (2021b). Syria War: UN Calculates New Death Toll. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-58664859 (accessed June 3, 2022).

BBC News (2022a). “Rwanda profile - Timeline,” in BBC News. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-14093322 (accessed May 5, 2022).

BBC News (2022b). “Balkans war: a brief guide – War in the former Yugoslavia, 1991 – 1999,” in BBC News. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-17632399 (accessed May 5, 2022).

BBC News (2022c). “How many Ukrainians have fled their homes and where have they gone?” in Russia-Ukraine War. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-60555472 (accessed April 24, 2022).

BBC News (2022d). “Radovan Karadzic sentence increased to life at UN tribunal,” in BBC News. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-47642327 (accessed May 5, 2022).

BBC News (2023). “Ukraine conflict: What war crimes has Russia been accused of?” in BBC News, Russia-Ukraine War. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-60690688 (accessed June 13, 2023).

Beauchamp, Z. (2022). “Is Russia committing genocide in Ukraine?” in Vox. Available online at: https://www.vox.com/23020696/ukraine-russia-genocide-allegations (accessed May 18, 2022).

Betts, A., and Collier, P. (2017). Refuge: Rethinking Refuge Policy in a Changing World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bhalla, N. (2019). “Factbox: Rwanda remembers the 800,000 who were killed on the 25th anniversary of genocide,” in Reuters. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-rwanda-genocide-anniversary-factbox-idUSKCN1RI0FV (accessed June 11, 2023).

Britannica (2022a). Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, “Rwanda genocide of 1994,” in Britannica. Available online at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Rwanda-genocide-of-1994 (accessed May 5, 2022).

Britannica (2022b). Fidel Castro, Political Leader of Cuba. Available online at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Fidel-Castro (accessed May 3, 2022).

Cambridge Dictionary (2022). To Make it Possible to Use Something to Attack a Person or Group. Available online at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/weaponize (accessed May 15, 2022).

Caparini, M. (2022). “Transnational Organized Crime: A Threat to Global Public Goods,” in Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, sipri. Available online at: https://www.sipri.org/commentary/topical-backgrounder/2022/transnational-organized-crime-threat-global-public-goods (accessed May 24, 2023).

Chase, S. (2022). “Parliament votes unanimously to declare Russia's war on Ukraine genocide,” in The Globe & Mail. Available online at: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/politics/article-parliament-declares-russias-war-on-ukraine-amounts-to-genocide/?cid=offsite_paid_searchADA&gclid=Cj0KCQjwspKUBhCvARIsAB2IYus0YTWRwgK22X4bp6XnIjNNhKs-w4TtjYXnEqo3pxGTDJ54SoIpsDsaAqmPEALw_wcB (accessed May 18, 2022).

Clementi, E. H. (2022). Associated Press, “Migrants march from south Mexico as U.S. moves to end the asylum COVID ban,” The Los Angeles Times Available online at: https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2022-04-01/migrants-march-from-south-mexico-as-us-lifts-covid-ban (accessed May 23, 2022).

Clover Films (2017). “The Boy Who Started the Syrian War, “Documentary Film, Clover Films, Al Jazeera. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=njKuK3tw8PQ (accessed May 5, 2022).

Convention on the Prevention Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (2022). Approved and proposed for signature and ratification or accession by General Assembly resolution 260 A (III) of 9 December 1948 Entry into force: 12 January 1951, in accordance with article XIII. Article II, Available online at: https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/documents/atrocity-crimes/Doc.1_Convention%20on%20the%20Prevention%20and%20Punishment%20of%20the%20Crime%20of%20Genocide.pdf (accessed May 4, 2022).

Des Forges, A. (1999). “'Leave No One to Tell the Story:' Genocide in Rwanda,” Human Rights Watch. Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/media_2020/12/rwanda-leave-none-to-tell-the-story.pdf (accessed May 5, 2022).

Falk, T. O. (2022). “How much money has the West spent on the Ukraine war?” in Al Jazeera. Available online at: https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2022/12/27/how-much-money-has-the-west-spent-on-the-ukraine-war (accessed February 20, 2023).

Farley, D. (2016). “Fundamental Changes in Warfare,” in Small Wars Journal Available online at: https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/fundamental-changes-in-warfare (accessed April 30, 2022).

Forced Migration Learning Module (2022). Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health. Available online at: http://www.columbia.edu/itc/hs/pubhealth/modules/forcedMigration/definitions.html (accessed May 8, 2022).

Frankel, J. (2022). “War,” Britannica. Available online at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/war/International-law (accessed April 27, 2022).

French, S. E. (2001). “The Warrior's Code,” in US Naval Academy, Department of Leadership, Ethics, and Law, 2001. Available online at: http://isme.tamu.edu/JSCOPE02/French02.html (accessed May 1, 2022).

GENOCIDE (2022). “Rwandan Genocide,” world without GENOCIDE. Available online at: http://worldwithoutgenocide.org/genocides-and-conflicts/rwandan-genocide (accessed May 4, 2022).

Genocide in Bosnia (2022). Holocaust Museum Houston. Available online at: https://hmh.org/library/research/genocide-in-bosnia-guide/ (accessed May 4, 2022).

Gollom, M. (2022). “Is Russia committing genocide in Ukraine? Proving that would be extremely difficult.” CBC News. Available online at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/genocide-ukraine-russia-1.6418624 (accessed May 18, 2022).

Gorbunova, Y. (2022). “Devastation and Loss in Bucha, Ukraine,” in Human Rights Watch. Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/03/30/devastation-and-loss-bucha-ukraine (accessed May 17, 2022).

Greenhill, K. (2012). “Dead Reckoning: Challenges in Measuring the Human Cost of Conflict,” Reinventing Peace. World Peace Foundation. Available online at: https://sites.tufts.edu/reinventingpeace/2012/02/10/dead-reckoning-challenges-in-measuring-the-human-costs-of-conflict/ (accessed June 13, 2023).

Greenhill, K. M. (2010). Weapons of Mass Migration: Forced Displacement, Coercion, and Foreign Policy. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell Studies in Security Affairs, Cornell University Press).

Harding, L., Mahmoud, M., and Weaver, M. (2012). “Syrian siege of Homs is genocidal, say trapped residents,” The Guardian Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/feb/07/syrian-homs-siege-genocidal-say-residents (accessed May 5, 2022).

History (2009). History.com editors, “Rwandan Genocide,” History. Available online at: https://www.history.com/topics/africa/rwandan-genocide (accessed May 5, 2022).

Horgan, J. (2022). “Will War Ever End?” Scientific American. Available online at: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/will-war-ever-end/ (accessed June 4, 2022).

Human Rights Watch (2022). “Ukraine – Apparent War Crimes in Russian-Controlled Areas,” in Human Rights Watch. Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/04/03/ukraine-apparent-war-crimes-russia-controlled-areas (accessed May 17, 2022).

Human Rights Watch World Report (2021). Venezuela Events of 2020. Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2021/country-chapters/venezuela# (accessed April 24, 2022).

ICRC (2008). “How is the term ‘armed conflict' defined in International Humanitarian Law?” Available online at: https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/resources/documents/article/other/armed-conflict-article-170308.htm (accessed June 2, 2022).

ICRC (2022a). “How Does Law Protect in War?” Declaration of War. Available online at: https://casebook.icrc.org/glossary/declaration-war (accessed June 2, 2022).

ICRC (2022b). “How Does Law Protect in War?” International Armed Conflict. Available online at: https://casebook.icrc.org/glossary/international-armed-conflict (accessed June 3, 2022).

ICRC (2022c). IHL Database, Customary IHL, Rule 129, The Act of Displacement. Available online at: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/customary-ihl/eng/docs/v1_rul_rule129 (accessed May 10, 2022).

IFRC (2022). Migration and Displacement. International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Available online at: https://www.ifrc.org/migration-and-displacement (accessed May 8, 2022).

Jacobson, L. (2022). “Russia's Invasion of Ukraine is especially lawless. Could Putin be tried for war crimes?” in POLITIFACT. Available online at: https://www.politifact.com/article/2022/mar/02/Russia-invasion-Ukraine-especially-lawless/?utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Twitter#Echobox=1646259611 (accessed May 18, 2022).

Jones, S. (2013). “Children in the Syrian War: Tortured on One Side, Recruited on the Other,” in The Atlantic Available online at: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/06/children-in-the-syrian-war-tortured-by-one-side-recruited-by-the-other/276876/ (accessed May 9, 2022).

Kaldor, M. (2005). Old wars, cold wars, new wars, and the war on terror. Int. Politics. 42:491–8. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.ip.8800126

Kaldor, M. (2017). “What are New Wars?” in YouTube. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3BCl4dSR8KA (accessed May 1, 2022).

Kamay, K., Podieh, P., and Salarkia, K. (2021). Stop the War on Children: A Crisis of Recruitment. Available online at: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/pdf/SWOC-5-5th-pp.pdf/ (accessed May 6, 2022).

Kirby, P. (2022). “Why has Russia invaded Ukraine and what does Putin want?” in BBC News. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-56720589 (accessed April 24, 2022).

Kleiderman, A. (2021). “Radovan Karadzic: Ex-Bosnian Serb leader to be sent to UK prison,” BBC News. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-57090123 (accessed May 5, 2022).

Krause-Jackson, F. (2022). “What is or isn't a Genocide? Does Russia's Invasion of Ukraine Qualify?” Bloomberg. Available online at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-04-13/what-is-or-isn-t-a-genocide-is-the-ukraine-war-one-quicktake (accessed May 18, 2022).

Lawder, D., and Gallagher, C. (2022). World Bank estimates physical damage at roughly $60 billion so far,” Reuters. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/world/world-bank-estimates-ukraine-physical-damage-roughly-60-billion-so-far-2022-04-21/ (accessed May 17, 2022).

Lazar, S. (2022). “Associative Duties and the Ethics of Killing in Wars,” in Journal of Practical Ethics. Available online at: https://www.jpe.ox.ac.uk/papers/associative-duties-and-the-ethics-of-killing-in-war/ (accessed May 1, 2022).

Long, H. (2014). “Seven Reasons Why World Peace is Possible,” in Permaculture News Available online at: https://www.permaculturenews.org/2014/09/12/seven-reasons-world-peace-possible/ (accessed June 5, 2022).

McKernan, B. (2022). “Rape as a weapon: huge scale of sexual violence inflicted in Ukraine emerges,” in The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/03/all-wars-are-like-this-used-as-a-weapon-of-war-in-ukraine (accessed May 10, 2022).

Milanovic, M. (2022). “ICJ Indicates Provisional Measures Against Russia, in a Near Total Win for Ukraine; Russia Expelled from the Council of Europe,” in EJIL: Talk! Blog of the European Journal of International Law. Available online at: https://www.ejiltalk.org/icj-indicates-provisional-measures-against-russia-in-a-near-total-win-for-ukraine-russia-expelled-from-the-council-of-europe/ (accessed May 18, 2022).

Mitchell, S. G. (2002). Is World Peace an Impossible Dream? J. Int. Institute. 9. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jii/4750978.0009.302/–is-world-peace-an-impossible-dream?rgn=main;view=fulltext. (accessed June 24, 2023).

Mobutu Sese Seko. (2022) Wikipedia. Available online at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mobutu_Sese_Seko (accessed May 19, 2022)

Modern Warfare (2022). Wikipedia. Available online at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modern_warfare (accessed April 27, 2022).

Morris, I. (2017). “The Age of Modern Warfare,” in Forbes. Available online at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/stratfor/2017/06/15/the-age-of-modern-warfare/?sh=2641563452b2 (accessed April 27, 2022).

New Wars (2022). Wikipedia. Available online at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_wars (accessed May 1, 2022).

Oxford Learner's Dictionaries (2023a). Authoritarianism is defined as “the belief that people should obey authority and rules, even when these are unfair or even when this means the loss of personal freedom. Available online at: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/english/authoritarianism?q=authoritarianism (accessed June 5, 2023).

Oxford Learner's Dictionaries (2023b). Totalitarianism is defined as? “the principles and practices of a political system in which there is only one party, which has complete power and control over the people”. Available online at: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/english/totalitarianism?q=totalitarianism (accessed June 5, 2023).

Perry, D. J., Guillermet Fernández, C., and Puyana, D. F. (2017). “The Right to Peace: From Ratification to Realization,” Health and Human Rights Journal. Available online at: https://www.hhrjournal.org/2017/01/the-right-to-peace-from-ratification-to-realization/#:~:text=Article%201%20of%20the%20resolution,peace%2C%20human%20rights%20and%20development (accessed June 8, 2022).

Physicians for Human Rights (2022). “Investigation and Documentation - Torture as a Weapon of War or Persecution,” in Physicians for Human Rights. Available online at: https://phr.org/issues/torture/prevention/torture-as-a-weapon-of-war-or-persecution/ (accessed May 10, 2022).

Poznansky, M. C., Callahan, M. V., and Hart, J. A. (2022). “Putin weaponizing refugees: NATO must draw redlines and enforce them,” in The Hill. Available online at: https://thehill.com/opinion/international/597652-putin-weaponizing-refugees-nato-must-draw-red-lines-and-enforce-them/ (accessed May 10, 2022).

Reliefweb (2022a). “The world must not grow numb to the suffering of the Syrian people,” OCHA Services, News and Press Release. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/world-must-not-grow-numb-suffering-syrian-people-enar. (access June 3, 2022).

Reliefweb (2022b). “Migration and Forced Displacement: Two Sides of the Same Coin?” reliefweb, OCHA Services, Press Release, Source – Helvetas, Posted. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/migration-and-forced-displacement-two-sides-same-coin (accessed May 8, 2022).

RFE/RL (2022). “UN Estimates that Over 11 Million People Displaced in Ukraine,” RadiofreeEurope, Radioliberty. Available online at: https://www.rferl.org/a/un-says-war-displaced-11-million-in-ukraine/31787195.html#:~:text=Ukrainians%20Displaced%20By%20The%20Russian,have%20crossed%20into%20neighboring%20countries.&text=Only%20refugees%20arriving%20in%20neighboring,move%20to%20countries%20farther%20west (accessed May 16, 2022).

Rikhof, J. (2022). “Ethnic cleansing and exclusion,” in Serious International Crimes, Human Rights, and Forced Migration, Simeon, J. C. (ed). (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2022), 258–278.

Russo-Ukraine War (2022). Wikipedia. Available online at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russo-Ukrainian_War (accessed May 4, 2022).

Rwanda (2022). University of Minnesota, College of Liberal Arts, Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Available online at: https://cla.umn.edu/chgs/holocaust-genocide-education/resource-guides/rwanda (accessed May 5, 2022).

Rwanda Genocide (2022). Wikipedia. Available online at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rwandan_genocide (accessed May 5, 2022).

Saeedi, N. (2020). “World Peace is not only possible but inevitable,” in UNDP Blog. Available online at: https://www.undp.org/blog/world-peace-not-only-possible-inevitable (accessed June 5, 2022).

Sapiezynska, E. (2021). “Weapon of War: Sexual Violence Against Children in Conflict,” Save the Children. Available online at: https://www.savethechildren.net/blog/weapon-war-sexual-violence-against-children-conflict (accessed May 10, 2022).

Save the Children (2021). The number of children living in the deadliest war zones rises nearly 20% to the highest in over a decade – Save the Children. Available online at: https://www.savethechildren.net/news/number-children-living-deadliest-war-zones-rises-nearly-20-highest-over-decade-%E2%80%93-save-children (accessed May 6, 2022).

Schmitt, M. N. (2022). “Ukraine Symposium – Weaponizing Civilians: Human Shields in Ukraine,” in Articles of War, Lieber Institute. Available online at: https://lieber.westpoint.edu/weaponizing-civilians-human-shields-ukraine/ (accessed May 10, 2022).

Sen Nag, O. (2019). “World's Most War-Torn Countries,” in World Facts, WorldAtlas. Available online at: https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-world-s-most-war-torn-countries.html (accessed May 2, 2022).

Siege of Homs (2016). YouTube, WikiAudio Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jeWF0ZDpWdY (accessed May 5, 2022).

Simeon, J. C. (2020). “Introduction: Terrorism, Asylum, and Exclusion from International Protection,” Terrorism and Asylum. (Leiden: Brill Nijhoff), 10.

Simeon, J. C. (2022). “Explicating the interrelationships between and among serious international crimes, human rights and human dignity, and forced migration,” in Serious International Crimes, Human Rights, and Forced Migration. (Abingdon: Rutledge) 347–372.

Simeon, J. C. (2023). “Realizing the Human Right to Peace,” in Peace Magazine, April-June 2023, 18–21. Available online at::///C:/Users/jcsimeon/Downloads/Peace-Magazine-Spring2023-lowres.pdf (accessed May 24, 2023).

Simeon, J. C., and van Sliedregt, E. (2019). “New Wars, Ever Escalating Crises, and Exclusion,” RLI Blog on Refugee Law and Forced Migration. Available online at: https://rli.blogs.sas.ac.uk/2019/04/09/new-wars-ever-escalating-crises-and-exclusion/ (assessed June 13, 2023).

Simpson, E. (2017). Clausewitz's theory of war and victory in contemporary conflict. Parameters. 47:7–18, doi: 10.55540/0031-1723.3100

Smith, D. (2015). “Where Concorde once flew: the story of President Mobutu's ‘African Versailles,”' The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/feb/10/where-concorde-once-flew-the-story-of-president-mobutus-african-versailles (accessed May 5, 2022).

Stop Genocide Now (2022a). “Syria,” Stop Genocide Now. Available online at: https://stopgenocidenow.org/conflicts/syria/ (accessed May 4, 2022).

Stop Genocide Now (2022b). “Syria,” Available online at: https://stopgenocidenow.org/conflicts/syria/ (accessed May 4, 2023).

Stop Genocide Now (2022c). “Syria,” Available online at: https://stopgenocidenow.org/conflicts/syria/ (accessed May 5, 2022).

Sullivan, B. (2022). Russia's at war with Ukraine. Here's how we got here,” in NPR. Available online at: https://www.npr.org/2022/02/12/1080205477/history-ukraine-russia (accessed May 4, 2022).

Syria Refugee Crisis Explained (2021). USA for UNHCR. Available online at: https://www.unrefugees.org/news/syria-refugee-crisis-explained/ (accessed May 5, 2022).

Syria The Battle of Aleppo. (2022). How Does Law Protect in War?, Case Prepared by Eleonora Heim, Masters student at the Universities of Basel and Geneva, under the Supervision of Professor Marco Sassòli and Ms. Yvette Issar, research assistant, both at the University of Geneva. Available online at: https://casebook.icrc.org/case-study/syria-battle-aleppo (accessed May 5, 2022).

Syrian Civil War (2022). Wikipedia. Available online at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syrian_civil_war (accessed May 5, 2022).

The Bosnian Genocide (2022). Montreal Holocaust Museum. Available online at: https://museeholocauste.ca/en/resources-training/the-bosnian-genocide/ (accessed May 4, 2022).

The Guardian Staff Agencies (2022). UK team to investigate sexual violence in Ukraine, says Truss,” The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/29/uk-to-send-investigators-to-ukraine-to-gather-evidence-of-war-crimes-truss-sayshttps://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/29/uk-to-send-investigators-to-ukraine-to-gather-evidence-of-war-crimes-truss-says (accessed May 10, 2022).

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (2022). “Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1992-1995,” in The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Available online at: https://www.ushmm.org/genocide-prevention/countries/bosnia-herzegovina/case-study/background/1992-1995 (accessed May 4, 2022).

Time (2015). “Is World Peace Possible?”. Available online at: https://time.com/3935254/is-world-peace-possible/ (accessed June 5, 2022).

Transnational Organized Crime (2022). “Transnational organized crime: the globalized illegal economy,” Transnational Organized Crime: Let's put them out of business undated. Available online at: https://www.unodc.org/toc/en/crimes/organized-crime.html (accessed May 12, 2022).

UN Peacebuilding Support Office (2017). Policy, Planning and Application Branch, “What Does ‘Sustainable Peace' Mean?” Available online at: https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/Guidance-on-Sustaining-Peace.170117.final_.pdf (accessed February 23, 2023).

UN Women (2023). “Building and Sustaining Peace”. Available online at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/peace-and-security/building-and-sustaining-peace#:~:text=Sustaining%20peace%20should%20be%20broadly,human%20rights%20laws%20and%20standards (accessed February 23, 2023).

UNHCR (2021a). Mid-Year Trends 2021. (Copenhagen, Denmark: UNHCR Global Data Service, 2021), 2. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/618ae4694/mid-year-trends-2021.html (accessed April 27, 2022).

UNHCR (2021b). UNHCR: Conflict, violence, climate change drove displacement higher in first half of 2021. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/news/press/2021/11/618bec6e4/unhcr-conflict-violence-climate-change-drove-displacement-higher-first.html (accessed April 27, 2022).

UNHCR (2022a). Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2021. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/62a9d1494/global-trends-report-2021 (accessed February 20, 2023).

UNHCR (2022b). Refugee Data Finder, Key Indicators. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/ (accessed February 20, 2023).

UNHCR (2022c). Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2021. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/62a9d1494/global-trends-report-2021 (accessed February 20, 2023).

UNHCR (2022d). “Forced and Unlawful Displacement,” in Handbook on the Protection of Internal Displaced Persons, Action Sheet 1, 164–170. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/4794b2d52.pdf (accessed May 10, 2022).

UNHCR (2023). Global Focus, Global Appeal 2023. Available online at: https://reporting.unhcr.org/globalappeal2023#:~:text=117.2%20million%20people%20will%20be,2023%2C%20according%20to%20UNHCR's%20estimations (accessed May 24, 2023).

UNHCR Global Focus (2023). Ukraine, Global Report 2022, Strategy 2023, Situation Analysis, states, “The international armed conflict in the Ukraine has caused forced displacement and suffering on a dramatic scale and has left at least 17.6 million people in urgent need of humanitarian assistance and protection. Available online at: https://reporting.unhcr.org/operational/operations/ukraine#:~:text=The%20international%20armed%20conflict%20in,of%20humanitarian%20assistance%20and%20protection (accessed June 13, 2023).

United Nations (2003). “Outreach Programme on the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda and the United Nations,” in International Day of Reflection, established, December 23, 2003. Available online at: https://www.un.org/en/preventgenocide/rwanda/day-of-reflection.shtml (accessed May 5, 2022).

United Nations (2017). Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948, Article 1 states, “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.”; “Why Peace? Because Dignity,” UAB Institute of Human Rights Blog, The University of Alabama at Birmingham. Available online at: https://sites.uab.edu/humanrights/2017/09/21/why-peace-because-dignity/ (accessed June 8, 2022).