- Department of Social Sciences, School of Social Sciences and Languages, VIT University, Vellore, India

Introduction: Social mobility is among the debated topics by researchers and policymakers today. This paper offers a comprehensive literature review in relation to sustainable social mobility among Indigenous communities.

Methods: This study employed bibliometric analysis using the Scopus database and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis, or PRISMA, flowchart. A total of 628 publications between 2001 and 2023 were analyzed using the keywords associated with social sustainability, mobility, and Indigenous communities.

Results: Research output has increased significantly since 2011. The countries with such outputs are mostly the United Kingdom, Italy, and the United States. The most-cited article was titled “Sustainable development: Meaning, history, principles, pillars, and implications for human action: Literature review.”

Discussion: The research reveals emerging trends and gaps in the literature on sustainable social mobility. It mainly focuses on how environmental sustainability, digital technologies, and other methodologies help to understand social mobility. Of course, the study also showed interest in community projects and local knowledge that can support sustainable development and social mobility for Indigenous communities.

1 Introduction

Indigenous communities worldwide face unprecedented challenges in achieving sustainable social mobility. These communities represent some of the most marginalized populations globally, with limited access to education, employment, and socioeconomic advancement opportunities (United Nations, 2021). These communities experience unique barriers that intersect with economic disadvantage, cultural preservation needs, geographic isolation, and historical discrimination, creating complex obstacles to upward social mobility (Anderson et al., 2016). Therefore, this study employs bibliometric analysis to examine the current research landscape on sustainable social mobility in Indigenous communities. Current studies emphasized that sustainable social mobility is influenced not only by income levels and quality of life but also by access to education and levels of social equity (Friedman et al., 2017). Sustainable social mobility refers to the process by which individuals advance through social hierarchies in a manner that is sustainable, fair, and accessible (Corak, 2020). In this era of growing inequality, sustainable social mobility is becoming an increasingly pressing issue (Chetty et al., 2017). Indigenous peoples represent approximately 476 million individuals worldwide, constituting less than 5% of the global population while accounting for 15% of the world’s extremely poor (United Nations, 2021). Despite their numerical minority status, Indigenous communities are the guardians of 80% of the world’s biodiversity and occupy 22% of global land area, making their sustainable social mobility critical for both social justice and environmental sustainability (Anderson et al., 2016).

Understanding how social mobility and sustainability intersect is important in contemporary social science, reflecting the dynamic interaction between social sustainability and the capacity, ability, or even level at which a social entity or its members can move within a social hierarchy. Furthermore, the limited representation of Indigenous voices in mainstream social mobility research perpetuates colonial research practices and fails to capture Indigenous-defined pathways to social advancement (Tuhiwai Smith et al., 2016; Watene, 2023). Several significant drivers of sustainable social mobility exist, particularly those affecting Indigenous communities. According to Richards and Scott (2009), education was identified as a main driver of social mobility, providing the necessary skills and knowledge to improve one’s socioeconomic status. Therefore, access to quality education is considered an essential factor for sustainable social mobility (UNESCO, 2020). However, educational pathways for Indigenous communities often require culturally responsive approaches that integrate traditional knowledge systems with contemporary learning frameworks (Simpson et al., 2021).

Social capital plays a significant role in social mobility outcomes. People with strong social networks have a higher likelihood of obtaining beneficial opportunities for enhanced social mobility (Alesina et al., 2021). Yet, Indigenous communities face unique challenges in building social capital across cultural boundaries while maintaining cultural integrity (Reid et al., 2020). This problem is compounded by institutional discrimination that creates systemic barriers specifically affecting Indigenous populations’ access to economic opportunities and social services (Smith, 1999; Langton et al., 2005). Thus, digital technologies reshape the work environment, creating immediate requirements for basic skills in all workplace areas (Malin, 1990). For Indigenous communities, digital inclusion presents both opportunities for connection and risks of cultural commodification (Kirmayer et al. 2011). Finally, Environmental sustainability is crucial because the same conditions causing environmental degradation and climate change equally affect disadvantaged communities unevenly and restrain them from pulling themselves up through their bootstraps regarding social mobility opportunities (IPCC, 2022). Indigenous communities are particularly vulnerable to environmental changes that threaten traditional livelihoods and force difficult choices between cultural preservation and economic adaptation (Greenwood et al. 2015).

A bibliometric analysis is undertaken in this research to pinpoint the research landscape for sustainable social mobility by pointing out the current trend, critical contributors, and influential key publications. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying research gaps and understanding how Indigenous perspectives have been integrated—or excluded—from mainstream academic discourse on social mobility (Wilson, 2008; Battiste, 2013). The bibliometric analysis will focus on key aspects, including publication trends over time, leading authors and institutions, most-cited papers, and thematic clusters within sustainable social mobility among Indigenous communities.

The paper concludes a bibliometric analysis on sustainable social mobility of Indigenous communities by distilling the existing literature into categories, ones that give insights to brighten up the present state of the research. The result is a general overview for academic discourse, which contributes to practical recommendations for stakeholders in developing initiatives for sustainable social mobility on behalf of Indigenous communities. Focusing on sustainable social mobility becomes a reality by the increasing recognition of achieving a balance between economic progress and social equity with environmental stewardship, especially for the marginalized, such as Indigenous communities. By doing so, the conclusions of this study will gain relevance for policy makers, researchers, and practitioners in making sustainable social mobility among Indigenous populations as effective as possible. Further studies can consider these emerging trends in the literature and the gaps identified by this study in making evidence-based policies and interventions. The bibliometric approach used in this paper also underlines the utility of quantitative analysis while mapping complex, interdisciplinary fields such as sustainable social mobility. The work in this area is intensely relevant because the world continues to grapple with issues of inequality, environmental sustainability, and social justice in finding paths toward a more equitable and sustainable future for all-though especially for historically marginalized communities.

2 Literature review

2.1 Theoretical foundations: cultural continuity and collective welfare

Indigenous conceptualizations of mobility are fundamentally distinct from Western mobility theories. Previous mobility theories emphasized individual mobility, education, and economic progress (Breen and Jonsson, 2005). Indigenous theories emphasized collective welfare, cultural continuity, and group economic progress (King et al., 2009). This distinction is observed consistently among Indigenous populations globally. New Zealand’s Māori society is a fine illustration of mobility in terms of cultural adaptability and group progress over individual achievement (Walter and Suina, 2018). North American Indigenous communities integrate cultural concepts into development planning, avoiding exclusive dependence on economic indicators (Cornell and Kalt, 2007). Australian Aboriginal communities demonstrate that culturally designed programs work relatively better than imposed programs (Langton et al. 2005).

Scandinavian Sami communities also attest to such tendencies with self-determination growth that preserves customary approaches while embracing modern possibilities, (Richmond and Cook 2016). Canadian Indigenous initiatives demonstrate stronger outcomes with cultural continuity alongside economic development, (Simpson 2017). Such international outcomes attest to community control being at the center of sustainable Indigenous upward mobility. Indigenous life worlds are characterized by holistic worldviews that integrate spiritual, cultural, economic, and environmental dimensions in ways that fundamentally differ from Western individualistic frameworks (Cajete, 2000). These life worlds emphasize reciprocal relationships with land, intergenerational responsibility, and collective decision-making processes that prioritize community wellbeing over individual advancement (Deloria, 1999). Understanding these distinct ontological foundations is essential for developing culturally appropriate social mobility frameworks.

2.2 Education systems: integrating traditional knowledge and contemporary learning

Education pathways are the primary drivers of Indigenous social mobility globally. Mainstream school systems continued to struggle with integrating Indigenous pedagogy (Quilaqueo and Torres, 2024). Culturally responsive school programs consistently outperform mainstream approaches in diverse global settings. The results are spread across the different continents. Australian Aboriginal children studying in Aboriginal schools excel academically without losing their culture (Brayboy, 2005). Canadian Aboriginal students in education who match their backgrounds graduate 35% higher than the general education (Toulouse, 2016). The initiatives are capable of blending Indigenous knowledge into modern curricula (Richards and Scott, 2009).

Language maintenance emerged as a key factor in academic achievement. Cross-cultural studies present strong evidence connecting Indigenous language maintenance with sustained social mobility (McCarty et al., 2015). Latin American policies of bilingualism in Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador guarantee Indigenous students’ access to tertiary education while preserving cultural identity (López Sichra, 2009). African contexts validate the same trends. Culturally-based school programs that have been adopted by Kenyan and Tanzanian Maasai cultures are more productive than conventional schooling systems (Homewood et al., 2009). Arctic Inuit schooling systems validate the impact of integrating Indigenous knowledge on schooling and cultural transmission (Keskitalo et al., 2013).

2.3 Geographic barriers: infrastructure and technological solutions

Geographic remoteness poses significant obstacles to Indigenous mobility across all continents. The problems seem very uniform around the globe. Canadian Arctic societies face gigantic educational, healthcare, and employment obstacles (Ford et al., 2016). Up to 40% of household spending was allocated to transportation, significantly limiting mobility opportunities (Southcott, 2018). Amazonian research describes concurrent infrastructure deficits within riverine Indigenous populations, namely digital connectivity and transport (Walker et al., 2013). Concurrent problems within North Scandinavian research are encountered by Sami reindeer herders balancing traditional livelihood sources and exposure to modern services (Harder et al., 2012).

Technology offers solutions to geographical constraints. Studies in Alaska indicate that the availability of high-speed internet is linked to improved education and economic opportunities for the Indigenous people (Townsend et al., 2013). Studies in Australia corroborate that investment in telecommunications infrastructure for remote Aboriginal communities improves access to education and health (Durie, 2001). Pacific Island nations possess unique cultures that are susceptible to geographical isolation and climate change. Sea levels rise and changed patterns of precipitation force Indigenous people to adopt adaptation mechanisms that reconcile economic and cultural integrity requirements (Bals et al., 2011). These indicate the place of infrastructure in facilitating Indigenous upward mobility while being sensitive to cultural concerns.

2.4 Economic development: traditional knowledge and modern markets

Indigenous communities worldwide demonstrated resourcefulness in developing economically sustainable livelihoods that do not compromise their cultural values. Inuit societies in the Arctic region can integrate traditional subsistence livelihoods and contemporary economic livelihoods (Pearce et al., 2010). The integrated livelihood systems are socially progressive but culturally enriching. The same adaptations are also shared by African pastoral societies. Maasai societies in Kenya and Tanzania blend customary pastoral living with modern conservation methods, which are more economically and environmentally rewarding compared to customary development methods (Homewood et al., 2009). The Tuareg societies of the Sahel also have adaptive mobility methods that blend local custom and climate adaptation methods (Roncoli et al., 2001).

Cultural tourism is also a great economic potential for Indigenous people across the globe. New Zealand has Māori-owned enterprises that are economically profiting while maintaining cultural identity at the same time (Taylor, 2001). Maya communities in Mexico and Guatemala establish successful eco-cultural tourist models that gain economic and cultural advantages (Malin, 1990). Traditional ecological knowledge is the foundation of sustainable economic growth. International studies have established that Indigenous methods of environmental management have economically sustainable options that are not incompatible with cultural values (Berkes and Turner, 2006). Such tendencies position traditional systems of knowledge at the center of sustainable social development for Indigenous societies.

2.5 Self-determination: governance and community control

Self-determination was the key prerequisite for Indigenous long-term social mobility. Canadian First Nations with self-government institutions are far more economically advanced and socially affluent than federally governed ones (Cornell and Kalt, 2007). Norwegian, Swedish, and Finnish Sami parliaments in Scandinavia have greater Indigenous involvement in decision-making, which translates to greater cultural preservation and economic success (Josefsen, 2007). New Zealand co-management Māori natural resource policies result in better environmental and economic outcomes (Coulthard, 2014).

Cross-cultural data from comparative international studies validate strong positive correlations between Indigenous measures of self-determination and international social mobility (Anaya, 2004). Cross-cultural studies in Africa, Asia, and the Americas document similar trends associating the power of self-governance with improved community outcomes (Rodríguez-Piñero, 2005). Latin American Indigenous movements are a testimony to the significance of political autonomy. Political organization among Bolivian Indians is a testimony that bottom-up development programs produce more productive results than those beginning from the top. These results validate bottom-up control as the most significant variable for attaining sustainable social mobility results.

2.6 Health disparities: challenges to social progress

Health inequities also robbed Indigenous people of significant social mobility opportunities all over the world. Foreign research still documents elevated levels of chronic disease, mental illness, and lower life expectancy among Indigenous individuals relative to non-Indigenous individuals (King et al., 2009). Australian evidence also validates close associations between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health status and possible social mobility, through intergenerational cycles of disadvantage (Priest et al., 2011). American evidence also validates the same, and the Indigenous people have been found to experience severe health inequities, limiting education and economic opportunities (Gracey and King, 2009).

Circumpolar North studies indicate Inuit communities are confronted with endemic health problems with respect to environmental contamination and dietary deviation from traditional diets, and they require new approaches integrating traditional and Western medicine (Bals et al., 2011). African Indigenous communities experience health disparities concerning marginalization and limited access to health care. Cultural healing models provide solutions to health inequalities. Empirical evidence from New Zealand shows that Indigenous curing-based Māori healthcare models that integrate evidence-based medical practice are better than traditional healthcare delivery (Durie, 2001). This presents the need for health equity for every universal Indigenous social mobility program.

2.7 Environmental challenges: climate adaptation and cultural preservation

Climate change and environmental degradation affected Indigenous individuals worldwide disproportionately, tackling social mobility concerns while undermining traditional livelihood mechanisms (Ford et al., 2016). Pacific Island studies consider sea-level increase and altered precipitation patterns that compel Indigenous individuals to employ adaptation mechanisms that are economic in character but maintain cultural identity (Bals et al., 2011). Arctic science documents climate change impacts on subsistence hunting, gathering, and fishing and compels Indigenous people to develop new economic activities while ensuring cultural relations with the environment (Pearce et al., 2015). African Sahel science documents Tuareg and other pastoralist communities adopting new mobility regimes integrating traditional and climate adaptation technology (Roncoli et al., 2001).

Indigenous knowledge systems contribute to climate adaptation policy-making in a bid to counter sustainable social mobility plans. International studies show that Indigenous ecological knowledge contains sustainable environmental management alternatives that are economically appropriate but still founded on cultural values (Berkes and Turner, 2006). Asian Indigenous people also share the same challenges. Himalayan people modify their customary agriculture systems to accommodate changing climatic patterns without compromising their cultural identity and reaching the global market. These changes demonstrate the convergence of Indigenous social development and environmental sustainability.

2.8 Digital technology: opportunities and barriers to access

Digital technologies provide opportunities and challenges for Indigenous social mobility across the world. The literature showed that internet access and digital literacy were key drivers of education and economic opportunities, especially for Indigenous individuals living in remote locations (McCarty et al., 2015). Northern Canadian research has indicated that Indigenous groups with access to high-speed internet have higher engagement in distance education and online economic markets (Walter and Andersen, 2013). Digital divide concerns are best felt, however, by Indigenous groups worldwide. Research in Australia illustrates high percentages of access barriers to digital technology among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, including infrastructural, economic, and cultural appropriateness concerns (Radoll, 2005).

United States statistics validate these trends, and rural Indigenous communities have long broadband and digital literacy gaps relative to national benchmarks (Strover, 2001). The African Indigenous community also suffers similarly, with infrastructure and finance gaps limiting the use of digital technology. Indigenous groups are a good example of innovation in the application of digital technology for cultural preservation and social mobility goals. Research in Alaska records Inuit groups using digital media for purposes of cultural preservation and bridging as well as for education and economic development (Searles, 2010). This highlights the capability of digital technology and underscores culturally adapted strategies for implementation. But effective integration of Indigenous views necessitates going beyond the use of technology to the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge systems, which have served communities through periods of environmental transition over thousands of years. Indigenous livelihood diversification experiences in response to climate change are of value that Western research methods cannot substitute, representing comprehensive knowledge about adaptive processes that balance preservation with economic stability.

2.9 Future directions and research gaps

The existing literature was dominated by significant gaps in a comprehensive understanding of Indigenous sustainable social mobility. Most research is from English-speaking developed countries with limited voices of Indigenous people of Africa, Asia, and Latin America (Smith, 1999). Most research applies Western research methods with limited use of Indigenous research methods and community-based participatory research (Wilson, 2008).

Future studies require more geographic diversity, more Indigenous researcher participation, and more studies that prioritize Indigenous epistemologies alongside traditional social mobility topics (Tuhiwai Smith et al., 2016). Longitudinal studies of Indigenous social mobility patterns spanning generations are a critical research area, as this limitation hinders determinants of long-term sustainability (Walter and Andersen, 2013). The convergence of cultural heritage preservation, economic growth, and ecological sustainability in Indigenous social mobility models requires more theoretical and empirical articulation (Pierotti and Wildcat, 2000). A consideration of successful projects undertaken by Indigenous communities in various global settings yields critical insights for policy development and community intervention program design (Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development, 2007). These gaps call for more culturally responsive and inclusive research designs that have more focus on Indigenous experience and voice in charting sustainable paths to social mobility. Closing these gaps will advance Indigenous social mobility knowledge and enable more effective policy and intervention design.

3 Problem statement

Although awareness of Indigenous peoples’ distinct challenges in achieving sustainable social mobility has increased, the research landscape remains fragmented across various fields without systematic integration. Existing literature has limited bibliometric analysis that explicitly charts research trends, delineates knowledge gaps, and indicates collaboration patterns in research on Indigenous sustainable social mobility. Such disjointedness impedes evidence-based policy and intervention development specific to Indigenous contexts. The lack of systematic knowledge mapping denies researchers and policymakers insight into the state of research and a foundation upon which to build. Thus, there is a need for extensive bibliometric analysis to synthesize the existing literature, uncover emerging themes, and inform future research directions in Indigenous sustainable social mobility.

4 Research questions

4.1 What are the publication trends and research evolution patterns of sustainable social mobility literature on Indigenous communities during 2001–2023?

4.2 What authors, institutions, and nations display the highest research productivity and citation influence in Indigenous sustainable social mobility studies?

4.3 What are the dominant thematic clusters and new conceptualizations in the literature on Indigenous sustainable social mobility as revealed through keyword co-occurrence analysis?

4.4 What are Indigenous sustainable social mobility research’s main publication venues, and what are the citation influence patterns?

5 Objectives

5.1 To examine temporal publication trends and research development pathways in Indigenous sustainable social mobility studies from 2001 to 2023 with comprehensive bibliometric indicators.

5.2 To determine and rank the most influential authors, institutions, and nations publishing Indigenous sustainable social mobility research based on citation and productivity.

5.3 To identify thematic structure and conceptual development in Indigenous sustainable social mobility studies through systematic keyword co-occurrence and clustering analysis.

5.4 To determine top-notch publication channels and analyze journal citation networks that facilitate the dissemination of knowledge in Indigenous sustainable social mobility research.

6 Materials and methods

6.1 Data acquisition and refinement

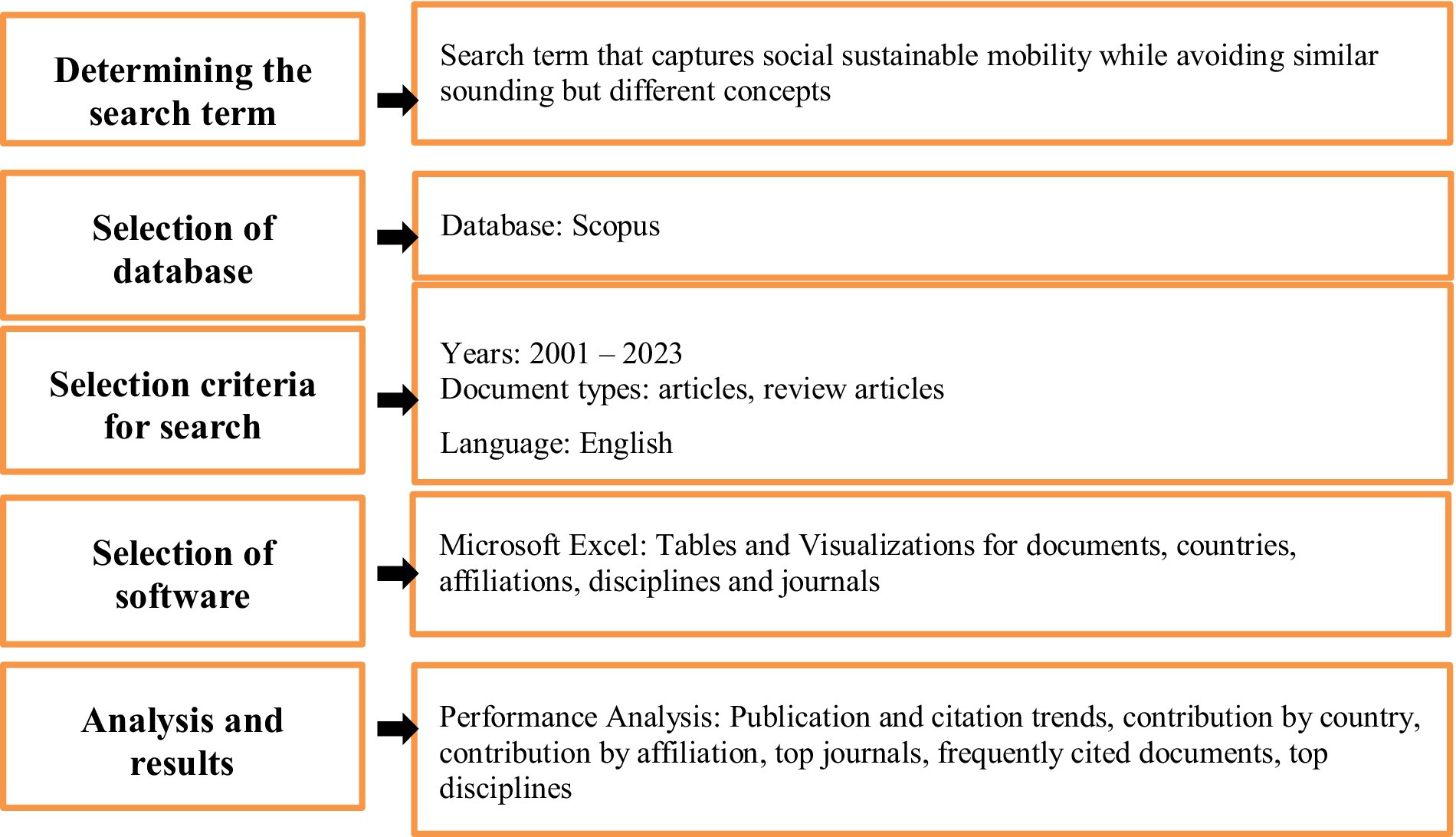

The methodology for the bibliometric analysis followed systematic acquisition and refinement of data. The Scopus database was selected based on the comprehensive coverage with a well-constructed search string to provide 2,234 initial documents relevant to sustainable social mobility.

6.2 Database selection

The Scopus database was selected due to its comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed literature across different disciplines.

6.2.1 Search strategy

Search terms were applied: (“Social sustainability” AND (“social mobility” OR “livelihood” OR “socio economic” OR “rural” OR “Indigenous” OR “Community” OR “Marginal*” or “Alien*” OR “Social Inclusion” OR “Equity” OR “Inequality” OR “Discrimination”)).

Search Parameters:

• Database: Scopus.

• Period: 2001–2023.

• Initial yield: 2,234 records.

A total of very high inclusion and exclusion criteria was adopted. The articles were selected from peer-reviewed journals that were written in the English language, while conference papers and book chapters were excluded from the analysis. This narrowed the number of publications to 628 related reports.

6.2.2 Inclusion/exclusion criteria

6.2.2.1 Inclusion

• Peer-reviewed journal articles: Guaranteed high quality in terms of rigorous evaluation.

• English language reports: Selected to maintain consistency of the analysis and avoid translation biases.

6.2.2.2 Exclusion

• Conference papers: Excluded for focusing only on more developed research outputs.

• Book chapters: Excluded on the grounds of document type consistency and quality of peer review.

6.2.3 Final document selection

Included Documents: 628 possible sources of literature. A PRISMA-type flow diagram was employed to visually represent the process adopted to ensure transparency and reproducibility. Data analysis techniques include bibliometric analysis through VOS viewer software, co-authorship analysis to trace collaboration networks, citation analysis to identify influential pieces, and keyword co-occurrence mapping to identify thematic clusters.

6.2.4 Selection process visualization

Utilized a flowchart (Figure 1), PRISMA-type that visually illustrates the selection process.

• The flowchart describes each stage of the selection process, including identification and final inclusion.

• This was to ensure transparency and reproducibility of the method of selection.

Publication and citation trends and contributions by country and institution were monitored. Also, the top journals and most frequently cited documents were identified.

PRISMA-inspired flowchart (Figure 1) illustrating the systematic selection process for bibliometric analysis of sustainable social mobility literature in Indigenous communities. The diagram shows the progressive filtering from initial database search (n = 2,234) through inclusion/exclusion criteria application to final document selection (n = 628). Each stage includes a specific number of records identified, screened, assessed for eligibility, and ultimately included in the quantitative synthesis. This transparent methodology ensures reproducibility and minimizes selection bias in the bibliometric analysis.

7 Data analysis methods

7.1 Bibliometric analysis framework

• Software: VOS viewer v1.6.18 with association strength normalization.

• Thresholds: Minimum 3 co-occurrences for meaningful pattern detection.

• Approach: Multi-dimensional network analysis to map intellectual landscapes.

7.1.1 Co-authorship network mapping

• Individual Level: Author collaboration patterns (min: 2 documents, 5 citations).

• Institutional Level: Inter-organizational research partnerships.

• Country Level: International knowledge exchange networks.

• Output: Collaboration webs revealing knowledge flow pathways.

7.1.2 Citation impact analysis

• Document Analysis: Most influential publications and citation trajectories.

• Author Networks: Knowledge gatekeepers and research leaders’ identification.

• Journal Patterns: Publication venue influence and cross-referencing.

• Output: Citation pathways mapping theoretical foundations.

7.1.3 Keyword co-occurrence mapping

• Author Keywords: Researcher-defined conceptual focus areas.

• Index Keywords: Database-assigned thematic classifications.

• Clustering: Automated thematic grouping (min: 3 occurrences).

• Output: Conceptual DNA revealing research frontiers and evolution.

7.1.4 Research performance analytics

• Temporal Analysis: 23-year publication trajectory mapping (2001–2023).

• Geographic Distribution: Country-wise research output and influence.

• Journal Ranking: Publication venue prominence and specialization.

• Output: Field growth dynamics and knowledge hub identification.

7.1.5 Bibliographic coupling analysis

• Document Coupling: Shared reference pattern analysis using Jaccard index.

• Author Coupling: Similar citation behavior identification.

• Journal Coupling: Cross-publication relationship mapping.

• Output: Invisible intellectual connections and research relatedness.

7.1.6 Network visualization strategy

• Node Sizing: Proportional to research impact and frequency.

• Link Thickness: Relationship strength representation.

• Color Coding: Temporal progression (blue-yellow chronology).

• Output: Dynamic knowledge architectures for pattern interpretation.

8 Results

8.1 Knowledge maps and research clusters

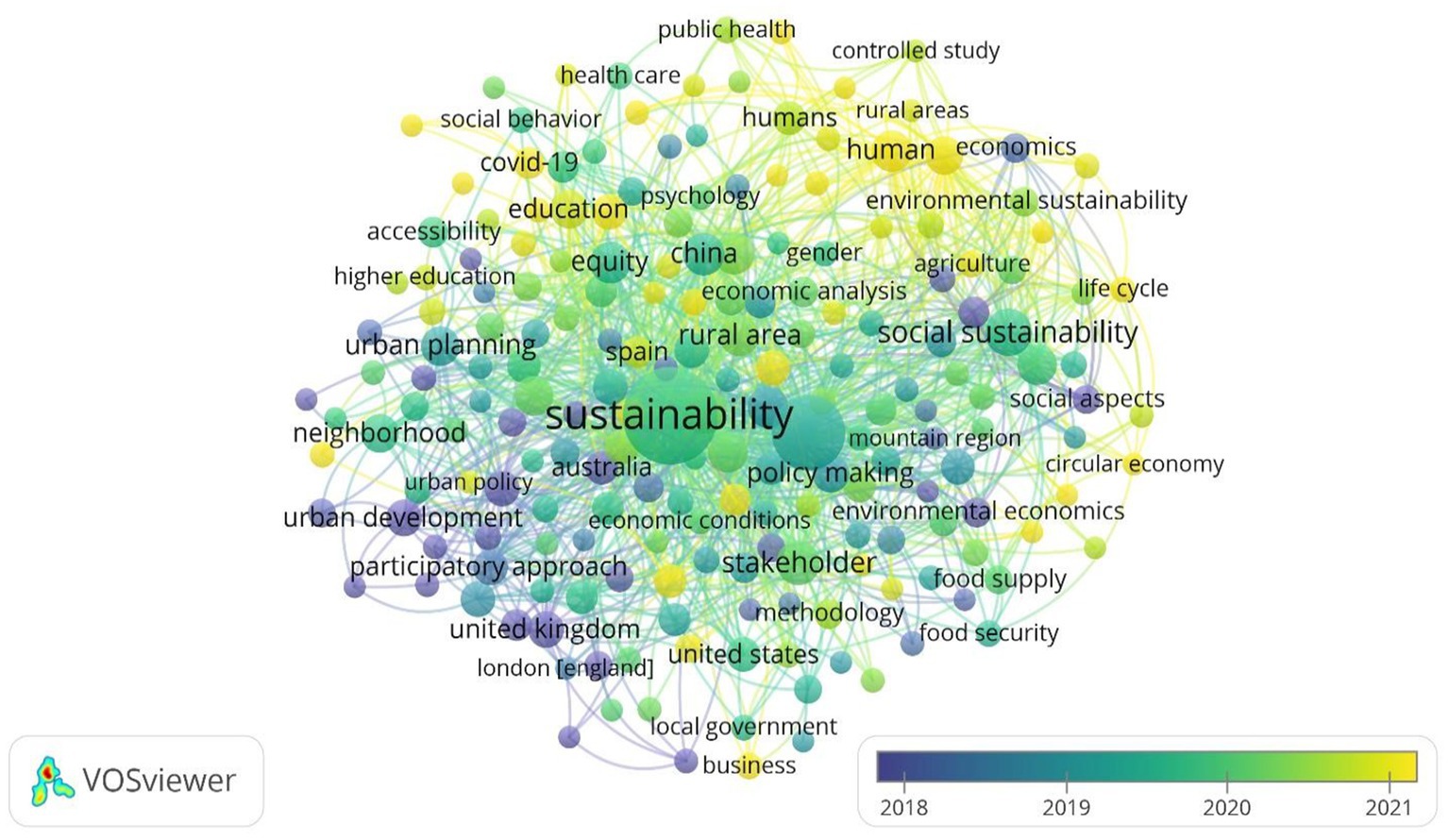

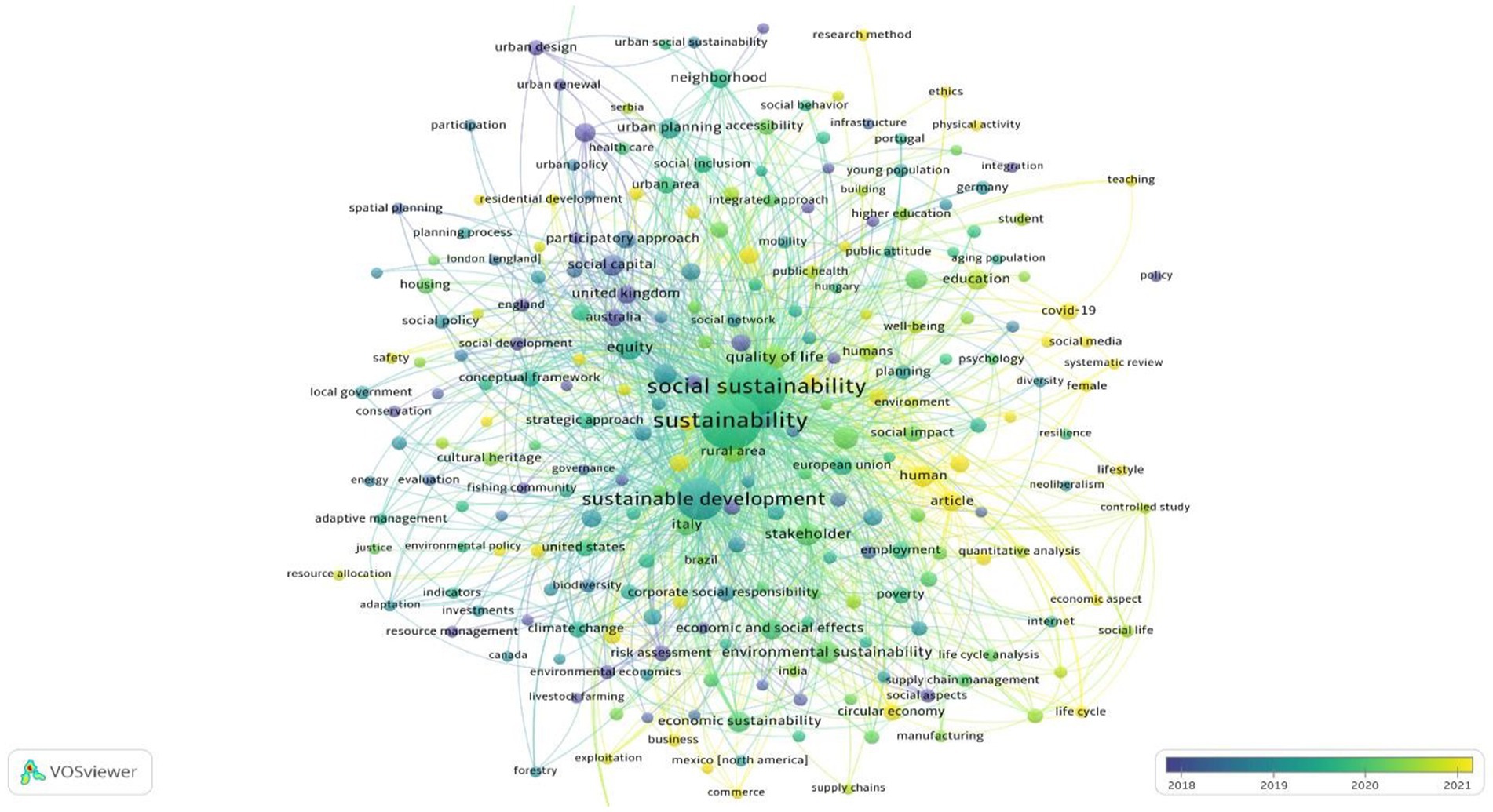

The analysis demonstrated how research on Indigenous social mobility has increased over time. Figure 2 indicates the central research themes, with “social sustainability” and “sustainable development” at the core. The map indicates five central areas of research that emerged between 2018 and 2021, illustrating how the field progressed from rudimentary sustainability concepts to targeted Indigenous research.

Figure 2. Keyword co-occurrence network map showing thematic clusters (co-occurrence of all keywords).

The keyword network indicates where Indigenous rights converge with environmental care, social justice, and community development. Terms such as “participatory approach,” “stakeholder engagement,” and “local government” are prevalent, indicating increasing focus on community-led processes that consider Indigenous voices and traditional knowledge.

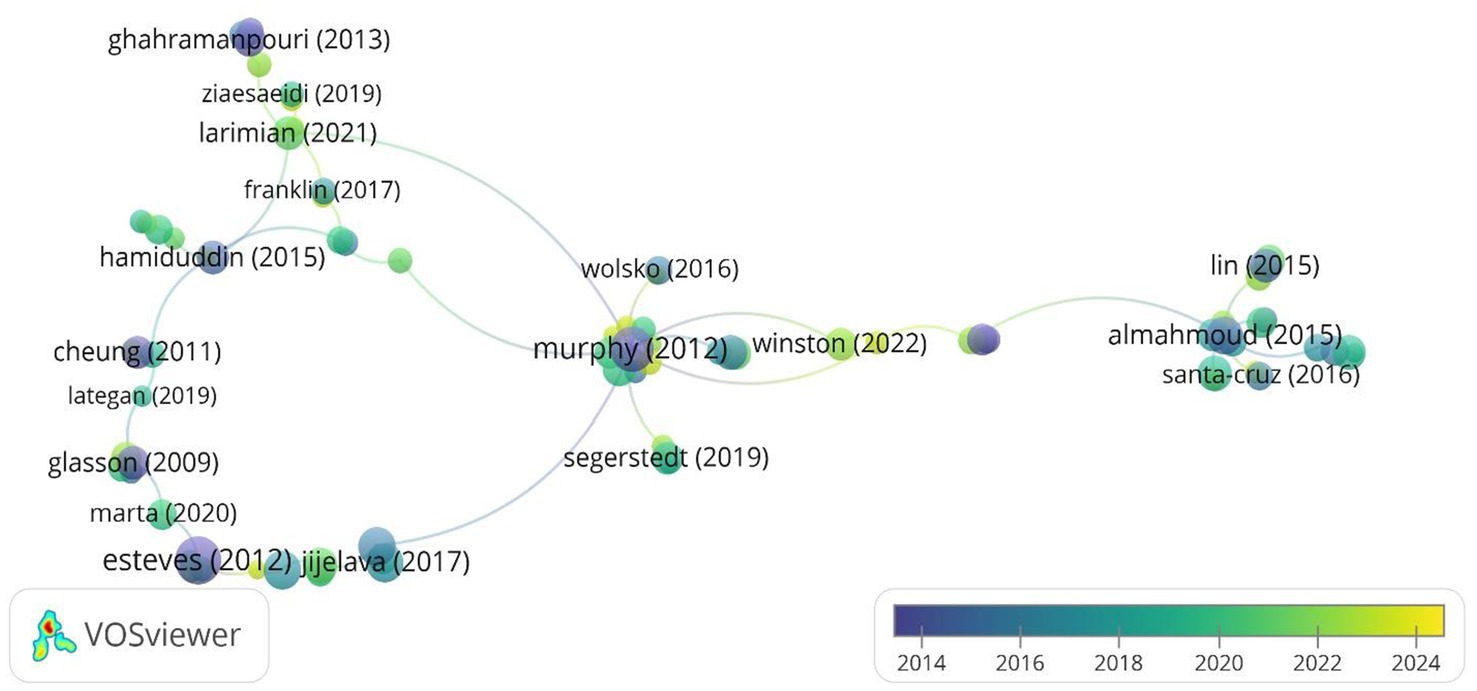

8.2 Citation patterns and key studies

Figure 3 indicates which studies are the most critical in Indigenous mobility studies. Critical works by Segerstedt and Abrahamsson (2019) have high citation counts, bridging earlier sustainability studies and new Indigenous-studies. This trend indicates how knowledge accumulates around certain theories, catering to the needs of Indigenous communities.

The timeline (2014–2024) indicates that research evolved from broad sustainability concepts to methods that are respectful of Indigenous societies and modes of governing. Research that came out after 2020 is more interconnected, implying greater collaboration as well as enhanced methodologies for researching Indigenous social mobility issues.

8.3 Global research hotspots

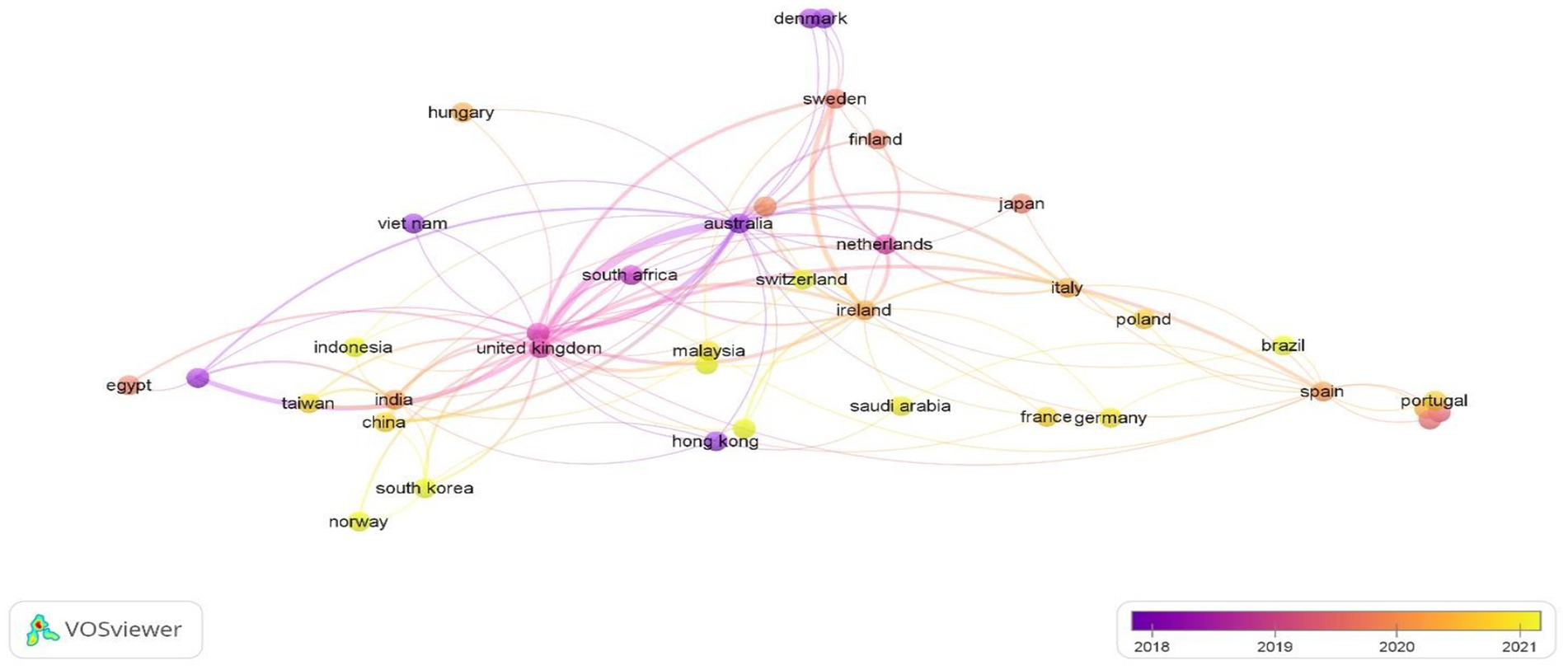

Figure 4 indicates obvious differences in where Indigenous mobility research occurs. Wealthy nations such as Australia, Canada, and Sweden dominate research, but research from Brazil, Mexico, and African nations is increasing. This trend indicates both who possesses resources to conduct research and where Indigenous mobility studies are most needed.

The collaboration map indicates Northern European universities collaborating with Indigenous-majority school regions. This implies useful partnerships, but the superiority of Western partners poses questions regarding who should conduct Indigenous research.

8.4 Cross-field connections

Figure 5 illustrates how various fields intersect in this subject matter. Phrases such as “environmental sustainability,” “social aspects,” “human economics,” and “circular economy” blend with Indigenous-specific concepts. This indicates the extent to which conventional academic divides are dissolving to address intricate mobility issues confronting Indigenous peoples.

Terms such as “mountain region,” “rural areas,” and “agriculture” occur together with “urban planning” and “policy making.” This indicates that researchers recognize that Indigenous peoples reside in numerous various locations and share different types of relations with traditional lands and contemporary cities.

8.5 Temporal research evolution and publication momentum

Table 1 depicts a dramatic acceleration of indigenous social mobility studies, shifting from intermittent scholarly interest to consistent scholarly momentum. The discipline witnessed a revolutionary transformation in three stages: foundational period (2001–2010) with negligible output averaging 5 publications per year, followed by academic awakening (2011–2018) with gradual increases, and culminating in a research explosion (2019–2023) where publications almost doubled to 44–48 per year. This 80% boost in recent times coincides with global crises—climate change, COVID-19, and social justice movements—that revealed Indigenous vulnerabilities while also expanding Indigenous voices in the academy. The high, consistent output from 2020 to 2023, in the face of global disruption, indicates that Indigenous social mobility has moved beyond niche scholarly interest to critical research priority, indicating intellectual maturity and institutional acceptability within sustainability science.

8.6 New research directions

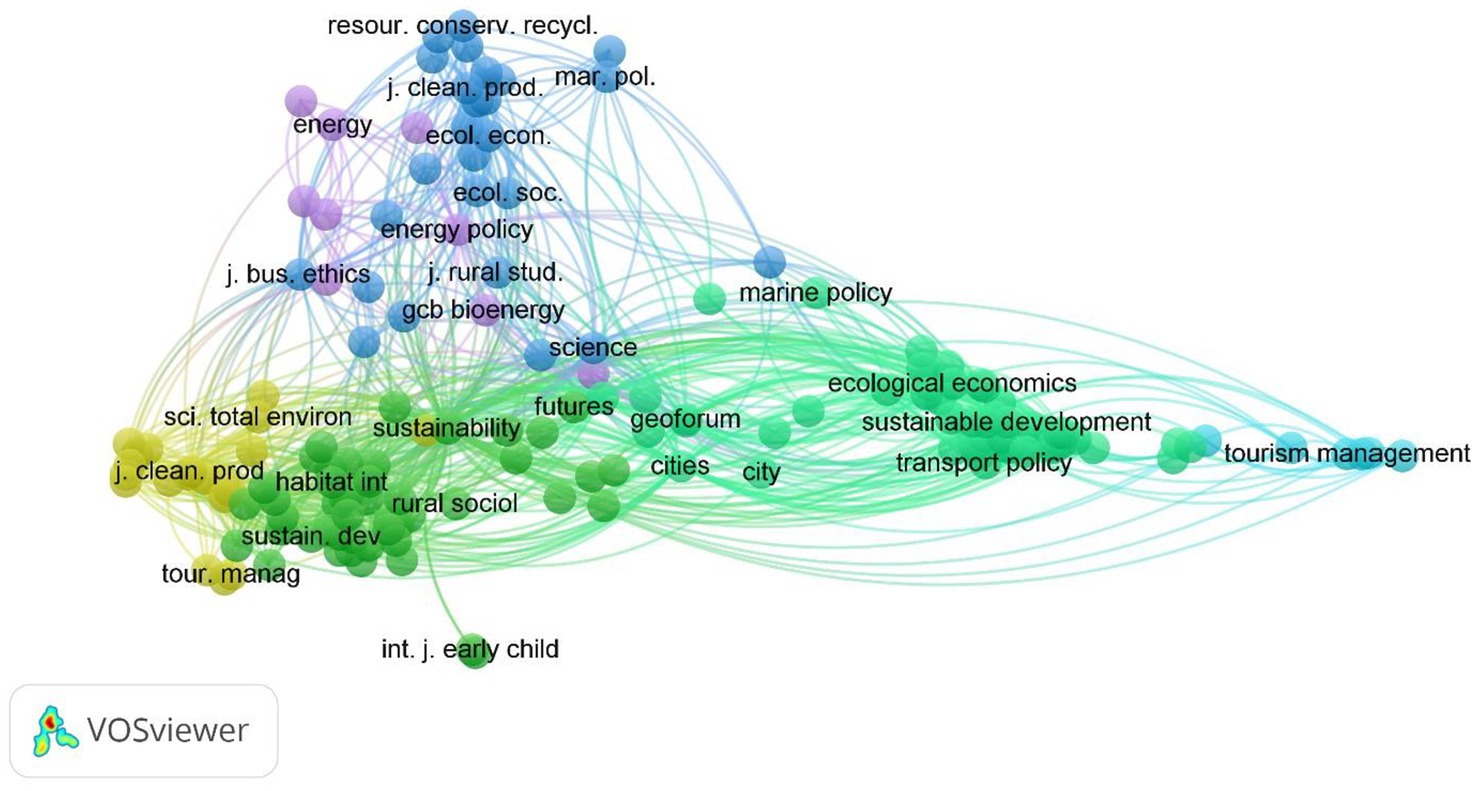

Figure 6 indicates the theories that guide contemporary Indigenous mobility scholarship. The network illustrates how ecological economics, sustainable development theory, and social justice concepts work together to form new strategies for Indigenous experiences. The emphasis on “tourism management,” “transport policy,” and “marine policy” reflects increased concern with how Indigenous communities engage with natural resources and economic growth.

Citation patterns indicate increasing recognition of Indigenous knowledge as valid science. Science is shifting away from pulling out information to collaborating with Indigenous communities as equal stakeholders and responding to real mobility issues.

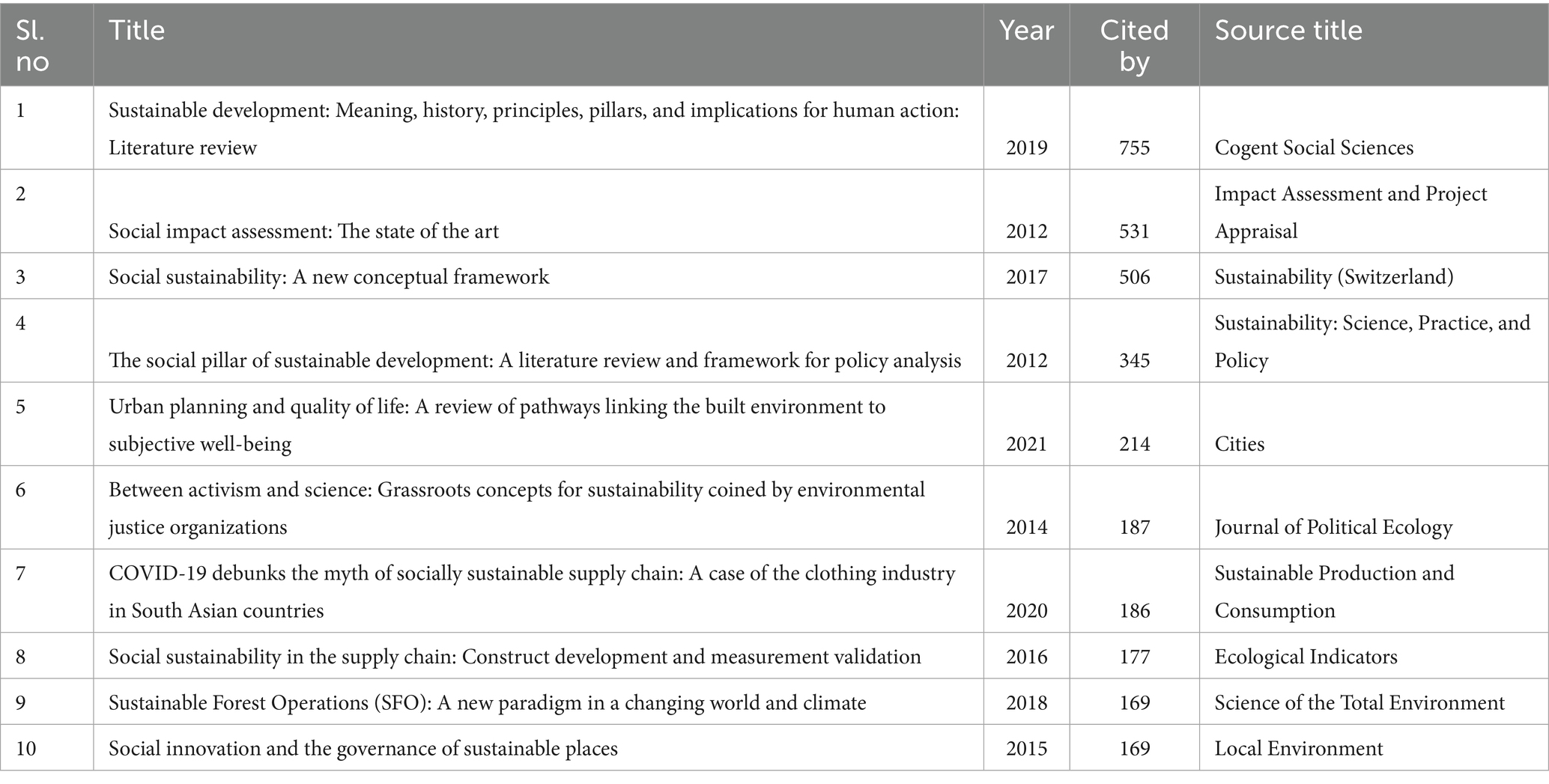

8.7 Publication trends and scholarly impact

The examination of the frequency of publication and citation rates indicates growing academic interest in Indigenous social mobility questions. Table 2 illustrates that seminal research on sustainable development and social sustainability remains in evidential dialog with current Indigenous-centered research, with more recent publications exhibiting rising specificity to Indigenous issues and contexts.

The most cited publications range from general sustainability frameworks (755 citations for sustainable development literature reviews) to individual case studies that target Indigenous experience with social impact assessment and community-based policy development. This hierarchy of citation implies that the discipline is moving from theory building toward applied studies that benefit Indigenous peoples directly.

8.8 Methodological innovation and research approaches

The bibliometric data points to a large-scale methodological breakthrough in the study of Indigenous social mobility. The salience of “participatory approach” and “stakeholder engagement” across keyword networks suggests increasing trends toward community-based participatory research approaches that make Indigenous communities research partners, not objects.

This methodological shift is part of larger decolonization processes in academic research, focusing on Indigenous self-determination in knowledge production and making research contributions respond to community-stated priorities, not external academic goals.

8.9 Research gaps and critical insights

Notwithstanding increasing scholarly interest, there are a few gaps that stand out in this bibliometric analysis. The lack of Indigenous authors among highly-cited papers points to persistent issues of academic access and visibility for Indigenous scholars. Also, the geographic focus of research in some areas is reflective of major knowledge gaps concerning Indigenous experiences of mobility in Africa, Asia, and other areas with large Indigenous populations.

The discussion also indicates scant integration with modern mobility theory and Indigenous knowledge systems, leaving room for further culturally-informed theoretical development that appreciates Indigenous thought while meeting contemporary mobility needs.

8.10 Implications for future research

This bibliometric exercise illustrates that sustainable social mobility studies in Indigenous settings are an emerging, fast-growing multidisciplinary field with great scope for theoretical contribution as well as real-world impact. The field is marked by enhanced methodological sophistication, a trend toward rising international collaboration, and widening acceptance of Indigenous knowledge systems as valid scientific paradigms.

Future research priorities must focus on Indigenous-led research, construct culturally suitable theoretical models, and establish long-term collaborative arrangements between academia and Indigenous societies to guarantee that research results directly benefit Indigenous social mobility initiatives and self-determination agendas.

9 Discussion

This analysis illuminates the complex interface between cultural factors and Indigenous social mobility. Based on a bibliometric analysis, the research related to sustainable social mobility reveals that this is highly interdisciplinary work that was drawn from collaboration among several academic departments and even corporate bodies, recommending a multifaceted solution toward tackling sustainable social mobility-both in sociology, economics, environmental studies, and so on. This also demonstrated the evolution of research themes over time, supporting the increasing emphasis on social aspects of sustainability and participatory approaches. This is paralleled by an increasing recognition of the complex interplay between social, economic, and environmental factors in achieving sustainable social mobility.

The steady growth in publications post-2010 suggests the increased academic interest in this field, perhaps because of the growing concern with inequality and sustainability of social and economic systems that currently exist (Piketty, 2014). The study encompasses topics like education, inequalities, and policy, for instance. In recent years, researchers have been interested more in sustainable development goals, which go to show that research into social mobility is in step with broader sustainability agendas (United Nations, 2015). The preponderance of prominence of certain journals and authors within this field suggests that economic perspectives have dominated, but social and environmental concerns are increasingly integrated. Yet closer analysis of the research finds one area that falls short-inadequate integration of Indigenous voices. Studies come primarily from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada, which raises questions about generalizability into a more global context, including Indigenous communities outside of these nations. This geographic bias might limit understanding of how social mobility and sustainability are experienced in different cultural contexts. The future of research should target a wide range of views, especially from Indigenous scholars and community members, to make the discourse on social mobility a reflection of their reality and aspirations.

The key takeaways of findings are policies that facilitate economic advancements and cultural preservation and engagement, perhaps making environments where Indigenous identities can thrive well together with social mobility (Narayan et al., 2018). In the context of culture, pressures of traditionalism against the Modernization of society often significantly influence educational attainments and employment opportunities for Indigenous people. This calls for a more nuanced approach to sustainable social mobility. As the discipline continues to evolve, collaboration between researchers, policymakers, practitioners, and Indigenous people becomes crucial in establishing equitable pathways for social advancement, honoring cultural heritage.

10 Conclusion

This study offers a comprehensive overview of sustainable social mobility research. In doing this, it focuses on the significance this has for Indigenous societies. The bibliometric analysis shows the importance of the field, as well as its interrelation with broader debates on sustainability and social justice. The findings demonstrated that the research was highly interdisciplinary, while distinct views are required on top of a growingly strengthened focus on social aspects within the sustainability discourse. Major findings support the urgent need for approaches focused on social mobility that incorporate economic, social, and environmental aspects, particularly when addressing Indigenous populations. Critically, Indigenous viewpoints and traditional ecological knowledge need to be at the heart of exploring livelihood diversification strategies in the face of climate change, since Indigenous people have centuries of experience in adaptive management of resources and sustainable mobility practices. This blending of Indigenous experiences guarantees more inclusive and culture-oriented methods of exploring sustainable social mobility research.

Future research should embrace more Indigenous voices and perspectives, broaden its geographical diversity, and interdisciplinary collaboration should be promoted, and bridge the gap between theoretical academic research and practical policy implementation should be bridged much better. There is a particular imperative for more diverse viewpoints from developing countries because issues of social mobility and sustainability may present differently (Narayan et al., 2018). Relatedly, whereas the economic aspects of sustainable social mobility have received considerable attention, there is scope for further research combining sociological, environmental, and policy perspectives on this issue (Cajete, 2000). This study, however, only included publications in the English language and focused on just one database. Future bibliography analyses may cover multiple databases and include non-English publications to provide a complete overview of the area. Nonetheless, as can be seen from this analysis, it provides important insights for those working to create sustainable social mobility. It underlines the need for holistic, culturally sensitive approaches toward understanding the complex interplay of social, economic, and environmental factors to engage in truly equitable social advancement for Indigenous peoples.

Because of these ideas on sustainable social mobility, it is only fitting for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to engage with indigenous communities to create equitable pathways that honor their cultural heritage and promote social advancement. This collaborative approach toward research and policy design should help ensure that future research and policies are not only academically rigorous but also practically relevant and culturally appropriate. This can further the field’s contributions toward broader goals of social justice and sustainable development by addressing gaps in current research and fostering more inclusive dialog.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found: Scopus.

Author contributions

NR: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JB: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alesina, A., Hohmann, S., Michalopoulos, S., and Papaioannou, E. (2021). Intergenerational mobility in Africa. Econometrica 89, 1–35. doi: 10.3982/ECTA17018

Anaya, S. J. (2004). Indigenous peoples in international law, New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press.

Anderson, I., Robson, B., Connolly, M., Al-Yaman, F., Bjertness, E., King, A., et al. (2016). Indigenous and tribal peoples' health (the lancet–Lowitja Institute global collaboration): a population study. Lancet 388, 131–157. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00345-7

Bals, M., Turi, A. L., Skre, I., and Kvernmo, S. (2011). The relationship between internalizing and externalizing symptoms and cultural resilience factors in indigenous Sami youth from Arctic Norway. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 70, 37–45. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v70i1.17790

Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Saskatoon, SK, Canada: Purich Publishing.

Berkes, F., and Turner, N. J. (2006). Knowledge, learning and the evolution of conservation practice for social-ecological system resilience. Hum. Ecol. 34, 479–494. doi: 10.1007/s10745-006-9008-2

Brayboy, B. M. J. (2005). Toward a tribal critical race theory in education. Urban Rev. 37, 425–446. doi: 10.1007/s11256-005-0018-y

Breen, R., and Jonsson, J. O. (2005). Inequality of opportunity in comparative perspective: recent research on educational attainment and social mobility. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 31, 223–243. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.31.041304.122232

Cajete, G. (2000). Native science: natural laws of interdependence. Santa Fe, NM, USA: Clear Light Publishers.

Chetty, R., Grusky, D., Hell, M., Hendren, N., Manduca, R., and Narang, J. (2017). The fading American dream: trends in absolute income mobility since 1940. Science 356, 398–406. doi: 10.1126/science.aal4617

Corak, M. (2020). The Canadian geography of intergenerational income mobility. Econ. J. 130, 2134–2174. doi: 10.1093/ej/uez019

Cornell, S., and Kalt, J. P. (2007). “Two approaches to the development of native nations: one works, the other doesn't” in Rebuilding native nations: strategies for governance and development, Ed. M. Jorgensen. (Tucson, AZ, USA: University of Arizona Press), 3–33.

Coulthard, G. S. (2014). Red skin, white masks: rejecting the colonial politics of recognition. Minneapolis, MN, USA: University of Minnesota Press.

Deloria, V. (1999). Spirit and reason: the vine Deloria Jr. reader. Golden, CO, USA: Fulcrum Publishing.

Durie, M. (2001). Mauri Ora: the dynamics of Māori health. Melbourne, VIC, Australia: Oxford University Press.

Ford, J. D., Cameron, L., Rubis, J., Maillet, M., Nakashima, D., Willox, A. C., et al. (2016). Including indigenous knowledge and experience in IPCC assessment reports. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 349–353. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2954

Friedman, S., Laurison, D., and Macmillan, L. (2017). Social mobility, the class pay gap and intergenerational worklessness: New insights from the Labour Force Survey. Social Mobility Commission, London, UK.

Gracey, M., and King, M. (2009). Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. Lancet 374, 65–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60914-4

Greenwood, M., de Leeuw, S., Lindsay, N. M., and Reading, C. (2015). Determinants of indigenous peoples' health in Canada: beyond the social. Toronto, ON, Canada: Canadian Scholars' Press.

Harder, H. G., Rash, J., Holyk, T., Jovel, E., and Harder, K. (2012). Indigenous youth suicide: a systematic review of the literature. Pimatisiwin 10, 125–142.

Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development (2007). The state of the native nations: conditions under U.S. policies of self-determination. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press.

Homewood, K., Kristjanson, P., and Chenevix Trench, P. (2009). Staying Maasai? Livelihoods, conservation and development in east African rangelands. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

IPCC (2022). Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Josefsen, E. (2007). The Saami and the national parliaments: Channels for political influence. In Parliament and Democracy in the Twenty-First Century: A Guide to Good Practice, Eds. Inter-Parliamentary Union & United Nations Development Programme (pp. 183-193). Geneva, Switzerland: Inter-Parliamentary Union.

Keskitalo, J. H., Määttä, K., and Uusiautti, S. (2013). Sami education. In Indigenous Education Around the World, Eds. R. Barnhardt and A. Kawagley. (pp. 101-118). London, UK: Routledge.

King, M., Smith, A., and Gracey, M. (2009). Indigenous health part 2: the underlying causes of the health gap. Lancet 374, 76–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60827-8

Kirmayer, L. J., Dandeneau, S., Marshall, E., Phillips, M. K., and Williamson, K. J. (2011). Rethinking resilience from indigenous perspectives. Can. J. Psychiatry 56, 84–91. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600203

Langton, M., Rhea, Z. M., and Palmer, L. (2005). Community-oriented protected areas for indigenous peoples and local communities. J. Polit. Ecol. 12, 23–50. doi: 10.2458/v12i1.21672

López Sichra, L. E. (2009). Intercultural bilingual education among indigenous peoples in Latin America. In Social Justice Through Multilingual Education, Eds. T. Skutnabb-Kangas, R. Phillipson, A. K. Mohanty and M. Panda. (pp. 295-309). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Malin, M. (1990). The visibility and invisibility of aboriginal students in an urban classroom. Austr. J. Educ. 34, 312–329. doi: 10.1177/000494419003400307

McCarty, T. L., Nicholas, S. E., and Wyman, L. T. (2015). 50 years later and counting: native American language education and the promise of the native American languages act. J. Am. Indian Educ. 57, 87–103.

Mensah, J., and Justice, S. (2019). Sustainable development: meaning, history, principles, pillars, and implications for human action: literature review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 5:1653531. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2019.1653531

Narayan, A., Van der Weide, R., Cojocaru, A., Lakner, C., Redaelli, S., Mahler, D. G., et al. (2018). Fair progress? Economic mobility across generations around the world. Washington, DC, USA: World Bank Publications.

Pearce, T., Ford, J. D., Laidler, G. J., Smit, B., Duerden, F., Allarut, M., et al. (2010). Inuit vulnerability and adaptive capacity to climate change in Uunartoq and Kangiqsujuaq, Nunavik. Polar Record 46, 157–177. doi: 10.1017/S0032247409008602

Pearce, T., Ford, J. D., Willox, A. C., and Smit, B. (2015). Inuit traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), subsistence hunting and adaptation to climate change in the Canadian Arctic. Arctic 68, 233–245. doi: 10.14430/arctic4479

Pierotti, R., and Wildcat, D. (2000). Traditional ecological knowledge: the third alternative. Ecol. Appl. 10, 1333–1340. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[1333:TEKTTA]2.0.CO;2

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press.

Priest, N., Paradies, Y., Gunthorpe, W., Cairney, S., and Sayers, S. (2011). Racism as a determinant of social and emotional wellbeing for aboriginal Australian youth. Med. J. Aust. 194, 546–550. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03099.x

Quilaqueo, D., and Torres, H. (2024). School contextualization with indigenous group’s socio-educational methods and pedagogies. Front. Educ. 9:1425464. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1425464

Radoll, P. J. (2005). Indigenous Australians and the digital divide. Canberra, ACT, Australia: AIATSIS Research Publications.

Reid, A. J., Eckert, L. E., Lane, J. F., Young, N., Hinch, S. G., Darimont, C. T., et al. (2020). “Two-eyed seeing”: an indigenous framework to transform fisheries research and management. Fish Fish. 22, 243–261. doi: 10.1111/faf.12516

Richards, J., and Scott, M. (2009). Aboriginal education: strengthening the foundations. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Canadian Policy Research Networks.

Richmond, C. A., and Cook, C. (2016). Creating conditions for Canadian aboriginal health equity: the promise of healthy public policy. Public Health Rev. 37:2. doi: 10.1186/s40985-016-0016-5

Rodríguez-Piñero, L. (2005). Indigenous peoples, postcolonialism, and international law: the ILO regime (1919–1989). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Roncoli, C., Ingram, K., and Kirshen, P. (2001). The costs and risks of coping with drought: livelihood impacts and farmers' responses in Burkina Faso. Clim. Res. 19, 119–132. doi: 10.3354/cr019119

Searles, E. (2010). Placing identity: town, land, and authenticity in Nunavut, Canada. Acta Borealia 27, 151–166. doi: 10.1080/08003831.2010.527531

Segerstedt, E., and Abrahamsson, L. (2019). Diversity of livelihoods and social sustainability in established mining communities. Extractive Indust. Soc. 6, 610–619. doi: 10.1016/j.exis.2019.03.008

Simpson, A. (2017). As we have always done: Indigenous freedom through radical resistance. Minneapolis, MN, USA: University of Minnesota Press.

Simpson, L. B., Walters, K. L., and Simoni, J. M. (2021). Decolonizing research paradigms: community-based participatory research and postcolonial feminist evaluation. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 27, 456–467. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000446

Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. London, UK: Zed Books.

Southcott, C. (2018). Northern communities working together: the social economy of Canada's north. Toronto, ON, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

Strover, S. (2001). Rural internet connectivity. Telecommun. Policy 25, 331–347. doi: 10.1016/S0308-5961(01)00008-8

Taylor, J. P. (2001). Authenticity and sincerity in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 28, 7–26. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(00)00004-9

Toulouse, P. R. (2016). What matters in indigenous education: implementing a vision committed to holism, diversity and engagement. Toronto, ON, Canada: Ontario Ministry of Education.

Townsend, L., Sathiaseelan, A., Fairhurst, G., and Wallace, C. (2013). Enhanced broadband access as a solution to the social and economic problems of the rural digital divide. Local Econ. 28, 580–595. doi: 10.1177/0269094213496974

Tuhiwai Smith, L., Maxwell, T. K., Puke, H., and Temara, P. (2016). Indigenous knowledge, methodology and mayhem: what is the role of methodology in producing indigenous insights? Qual. Res. 22, 96–110. doi: 10.1177/1468794115596501

UNESCO (2020). Global education monitoring report 2020: inclusion and education: all means all. Paris, France: UNESCO Publishing.

United Nations (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York, NY, USA: United Nations.

United Nations (2021). State of the world’s indigenous peoples: rights to lands, territories and resources. New York, NY, USA: United Nations Publications.

Walker, R., Hassall, J., Chaplin, S., Congues, J., Bajraktari, D., and Mason, D. (2013). Health care access and indigenous people in remote communities. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 72:21544. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21544

Walter, M., and Andersen, C. (2013). Indigenous statistics: a quantitative research methodology. Walnut Creek, CA, USA: Left Coast Press.

Walter, M., and Suina, M. (2018). Indigenous data, Indigenous methodologies and Indigenous data sovereignty. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 22, 233–243. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2018.1531228

Watene, K. (2023). Indigenous data sovereignty and the ethics of research collaboration. J. Appl. Philos. 40, 123–145. doi: 10.1111/japp.12595

Keywords: bibliometric analysis, sustainable social mobility, social equity, research trends, Indigenous communities

Citation: Ramaprabha N and Balamurugan J (2025) Sustainable social mobility among Indigenous communities: a bibliometric analysis. Front. Hum. Dyn. 7:1538673. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2025.1538673

Edited by:

Omololu Michael Fagbadebo, Durban University of Technology, South AfricaReviewed by:

Ngambouk Vitalis Pemunta, University of Gothenburg, SwedenMonica Adele Orisadare, Obafemi Awolowo University, Nigeria

Copyright © 2025 Ramaprabha and Balamurugan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: J. Balamurugan, YmFsYW11cnVnYW4uakB2aXQuYWMuaW4=

N. Ramaprabha

N. Ramaprabha J. Balamurugan

J. Balamurugan