- 1The PAST Foundation, Columbus, OH, United States

- 2Department of Anthropology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, United States

Wolf’s Europe and the People Without History has significantly influenced anthropology and social science, marking a crucial point in the discipline’s engagement with historical perspectives. However, the conceptual frame employed by Wolf excluded an important aspect of human life from consideration among native peoples of North America – market exchange. My goal in this essay is to reexamine the role of market exchange in Native North America. But rather than rehash the critiques of the substantivist-Marxist-Polanyian frame, I propose the use of an alternative approach drawn from the New Institutional Economics. My goal is to explore the diverse ways in which social institutions (or rules) governed the social construction of private goods, especially the creative ways humans generate institutions to facilitate exchange in the absence of reciprocity, which builds trust by embedded exchange in social relationships. I present ethnohistoric and archeological data from Alaska (Iñupiaq), Arizona (Hohokam), and Illinois (Cahokia) to demonstrate that native peoples engaged in commodity exchange, including market exchange, prior to European contact. Evidence includes detached specialization, patterned diversity/distributional approach (an archeological marker of market exchange), and strategies used to build trust and overcome cooperation problems generated by anti-market behaviors.

Introduction

Wolf’s (1982) Europe and the People Without History is arguably one of the most influential works in Anthropology’s history, appearing when the discipline was rediscovering history (e.g., Comaroff, 1982; Sahlins, 1981). Although informed by Polanyi, it stimulated thinking regarding regional and macro-regional processes, including drilling down on the processual importance of commercialization in pre-modern India, China, and Mesoamerica (Blanton, 1996; Fargher and Blanton, 2021; Feinman and Garraty, 2010; Rezavi, 2015; Skinner, 1964).

Yet, anthropologists have been slower to apply these ideas to other non-Western and pre-colonial societies. As part of broader trends to move beyond the limits of Polanyian concepts (e.g., Blanton and Feinman, 2024), I examine three Native North American cases from the frame of the New Institutional Economics (NIE). NIE is intriguing because it curtailed the undersocialized rational actor employed by neoliberal economists, but avoided the over-socialized approach championed by Polanyi and others. By considering history, bounded rationality, institutions, collective goods, social and legal ties among people, transactions costs, uncertainty, and imperfect competition, it better explains economic processes (e.g., Acheson, 1994).

From this base, I lay out my conceptual frame involving the non-alienation and alienation of private goods, market exchange as a form of commodities exchange, and the mechanisms used to manage and overcome cooperation problems associated with this type of exchange. Then, I present evidence of alienation of goods and market exchange in Native North America.

Conceptual frame

New institutional economics and goods

The NIE made two important contributions that can help anthropologists move beyond Polanyi: (1) a classification of goods based on rivalry and excludability; and (2) recognition that rationality is more complex than depicted in neoclassical theory and avoids Polanyi’s over-socialization [which is attributable to his personal opposition to market in his own life (Blanton and Feinman, 2024)].

Goods classifications

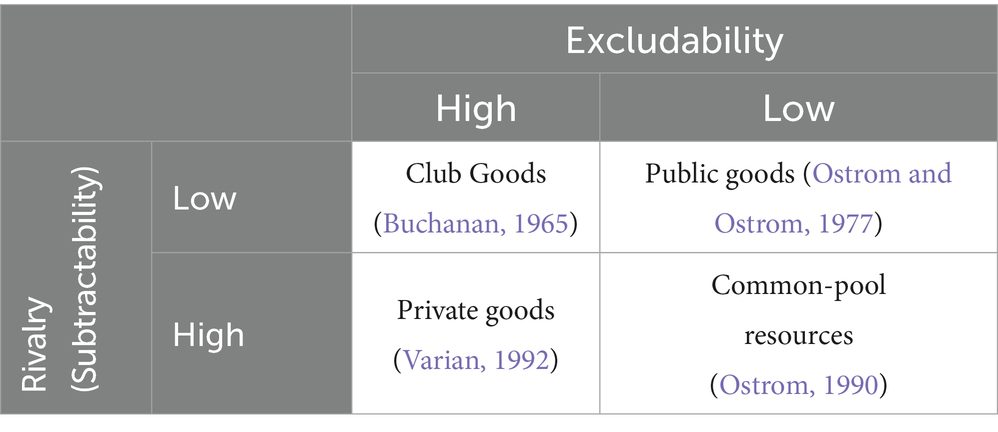

The NIE reevaluated neoclassical economics to improve scholarly understanding of economic transactions. They did this by incorporating the processual impacts of subtractability and excludability (e.g., Ostrom and Ostrom, 1977). Subtractability refers to the extent to which one individual’s consumption of a good reduces the availability of said good for others; and, excludability pertains to the costs associated with preventing other individuals from consuming said good. By crossing these factors, this approach envisions four categories of goods: private, public, club, and common-pool resources (Table 1). Private goods, the focus here, are defined by high subtractability and high excludability: once an individual obtains a private good, it is no longer available to others and it costs comparatively little to prevent others from accessing it. Examples include products like food, pots, and clothing, etc. (Varian, 1992).

Bounded rationality

New Institutional Economics recognized the need to revise neoclassical models because rationality varies among behavioral contexts (Ostrom and Ostrom, 1971). Simon’s (1947, 1955) concept of bounded rationality proved useful, because it recognizes how cognitive limitations and contextual factors shape decision-making. When individuals make decisions, these factors prevent them from achieving the outcomes envisioned by neoclassical models (ibid). Instead of being perfectly rational, individuals operate within the bounds of their limited cognitive resources, available information, and (cultural) constraints (ibid). NIE determined that institutions are necessary to overcome these limits (Ostrom, 2009).

Institutions, defined as formal and informal rules and norms, shape, guide, and constrain decision-making (Blanton and Fargher, 2016; Feinman and Garraty, 2010; Ostrom, 1990, 2009). They help resolve cognitive limitations and cultural constraints by reducing uncertainty, enhancing information processing, simplifying decision-making, facilitating cooperation, preserving historical knowledge, and constraining selfish behavior (Blanton and Fargher, 2016; Ostrom, 1990). With respect to the exchange of private goods, institutions reduce transaction costs (e.g., collecting information, negotiating, and enforcing contracts, etc.) and facilitate exchange by providing rules that enhance transparency and access to information, foster trust and cooperation, reduce the need for monitoring, and increase fairness and equity (Blanton and Fargher, 2016; Ostrom, 2009).

Institutions and the exchange of private goods

Within this frame, I consider all human societies across time and space. I focus on the institutions that govern the exchange of private goods, not on types of cultures. Here, institutions create the social embedding that governs the movement of private goods between individuals (cf. Feinman and Garraty, 2010). They determine the construction of goods as either non-alienable (gifts) or alienable (commodities) and provide the mechanisms that reduce uncertainty, support trust and cooperation, and facilitate exchange. Following Gregory (2015), Mauss (1954), and Polanyi (1957), I categorize these mechanisms broadly as reciprocity and commodities exchange.

Reciprocity

Reciprocity is, “… an exchange of inalienable things between transactors who are in a state of reciprocal dependence” (Gregory, 2015, p. 6; see Mauss, 1954). Inalienable goods (gifts) are tied socially to their owner; thus, the act of giving incurs a debt that comes with a social obligation to repay (Gregory, 2015; Mauss, 1954). This process binds the giver and the receiver/return giver into a social relationship (Gregory, 2015; Mauss, 1954). The emergent social relationship is of central importance and continued exchanges maintain it, which leads to trust and confidence one can depend on their partner (Gregory, 2015; Mauss, 1954; Polanyi, 1957). Reciprocity can take a number of forms, e.g., negative, balanced, competitive, etc. (see Mauss, 1954; Sahlins, 1972 for details).

Given the need to develop and maintain strong social relationships between partners, reciprocal gift exchanges are limited to individuals who are known to each other and who have a history (Mauss, 1954; Sahlins, 1972). Cognitive limitations also set an upper bound on the number of individuals a person can know well enough to form a partnership. Thus, exchange between strangers, or between individuals known to each other but otherwise socially unbound, is limited because these individuals cannot rely on social embedding to reduce transaction costs and solve cooperation problems (Blanton and Fargher, 2016; Geertz, 1979). Accordingly, a different set of social institutions or social embedding is required for exchange to occur.

Commodities exchange

Commodities exchange is the mechanism by which private goods move when reciprocal-exchange relationships are absent (Bohannan, 1955; Sahlins, 1972). It involves the exchange of alienable goods (commodities, services, money) between individuals without entering into a state of reciprocal dependence (Feinman and Garraty, 2010; Gregory, 2015). The social construction of alienable items or commoditization disconnects items from individuals, making them available for “sale” (Gregory, 2015). By “sale,” I mean items move between individuals without incurring responsibility to engage in a future return exchange. Accordingly, commodities exchange is balanced exchange of one species of good for another species of good.

Commodities exchange has many forms, including barter (the direct transfer of commodities for commodities) (Dalton, 1982; Gregory, 2015; Humphrey and Hugh-Jones, 1992), the exchange of money for commodities/commodities for money (Gregory, 2015), and buying/selling economic instruments (e.g., bonds, stocks, futures, commoditized debt, etc.). It may or may not occur in marketplaces. Marketplaces are defined spaces in which face-to-face commodity transactions, called market exchange, occur (Feinman and Garraty, 2010); whereas non-market place transactions include itinerant sales, casual barter, etc. Because commodities exchange involves the transfer of unlike things, “prices” (equivalencies) must be established so exchanges are balanced and no responsibility for future returns is incurred (Humphrey and Hugh-Jones, 1992). This need creates two cooperation dilemmas: (1) agreeing upon price-making mechanisms; and (2) mechanisms to overcome anti-market behaviors (e.g., cheating, peddling fakes, frauds, rotten/shoddy goods, grudges/feuds/ethnic conflicts, biased dispute resolution, price manipulation, free riding to obtain unearned profits, etc.) (the capitalist impulse in Blanton and Feinman, 2024).

(1) Where monetary systems exist, prices are determined based on supply, demand, materials and labor costs, inflationary trends, and taxes/tariffs (Crowson, 1985; see also Feinman and Garraty, 2010). In non-monetary contexts, negotiation (haggling) is a common means for establishing prices or values (Chapman, 1980; Feinman and Garraty, 2010; Nash, 1950; Uchendu, 1967). Prices/values may also be determined by custom or by an authority (Chapman, 1980). In neoclassical theory, price is determined strictly by utility (e.g., Nash, 1950). In the real world, humans are social–emotional creatures who tie other considerations to the determination of an object’s price/value or attempt to free ride to obtain unearned profits (Blanton and Feinman, 2024; Humphrey and Hugh-Jones, 1992; Simon, 1955). Likewise, multiple price-determining mechanisms may operate within the same culture/territory/marketplace depending on the specific commodity, the individuals involved, and/or the timing of the transaction (cf. Chapman, 1980; Humphrey and Hugh-Jones, 1992).

(2) Concentrating commodities exchange in marketplaces offers the opportunity to overcome a range of anti-market cooperation problems, but this requires the creation of trust-building institutions. Blanton and Feinman (2024) identify four principal strategies, variably used, to facilitate cooperation in marketplaces so that market exchange can effectively function, and I add a fifth:

a. Altruistic punishments (benefit the group but are costly for individuals): involves spontaneous joint-enforcement of market institutions by the market crowd to protect joint-benefits.

b. Marketplace governance: involves the emplacement of organizations charged with governing markets and ensuring that rules (institutions) are enforced, especially egalitarianism and neutrality; this may involve state regulation, paragovernmental organizations, religious organizations or individuals, and/or other types of organizations.

c. Synchronization and territorialization: involves the establishment of a specific (permanent) location where exchanges occur (marketplace) and a fixed schedule or calendar for the use of this space; by combining a location with a calendar, marketplaces become information-rich spaces, “…regarding the quantity and quality of goods offered and the constellation of other buyers and sellers in attendance” (Blanton and Feinman, 2024, p. 7; see also Blanton and Fargher, 2016). Gathering large amounts of individuals contributes to transparency regarding quality, honesty, and information needed for price setting.

d. Boundedness and sacrality: involves symbolically or physically marking marketplace as special liminal spaces where a specific set of rules are in place that may contradict everyday cultural institutions. Marketplaces are often tied to other sacred spaces (e.g., temples), and religious figures sometimes serve as marketplace adjudicators, leveraging their moral authority to maintain order and fairness. For instance, in ancient Greece and medieval Europe, markets were frequently associated with religious sites, which helped regulate behavior by promoting moral standards (Blanton and Fargher, 2016). In the Berber Highlands, marketplaces were often overseen by religious figures, who ensured the peace and prosperity of the market through their respected authority (Fogg, 1942). Within these spaces, institutions promoting, “… cooperative, orderly, and egalitarian culture,” the alienability of goods, and the freedom to engage in transactions with strangers or suspend reciprocal relationships are in place (Blanton and Feinman, 2024, p. 7). Accordingly, market exchange can cross-cut ethnic differences and/or hierarchical distinctions (Blanton and Fargher, 2016; Blanton and Feinman, 2024).

e. Camaraderie and liminal identity: involves rapidly building “friendships” among strangers/enemies through feasting, rituals, dancing, and gaming. Feasting enhances trust among participants by creating a sense of community and shared identity (Blanton and Fargher, 2016; Van den Eijnde, 2018). Games, including gambling, provide a structured environment where individuals can engage in competitive yet fair interactions, fostering a sense of mutual respect and trust (Barnes et al., 2017; Joubert and De Beer, 2011; Weiner, 2018). Dancing, especially where groups coordinate complex movements through practice (entrainment), promotes trust and cooperation (Blanton and Fargher, 2016). Accordingly, competitive games, gambling, dancing, and feasting are often part of larger ritual cycles that include market exchange.

A note on assumptions

Neither gifting nor commodity change is (un)natural in any society; the institutions that socially constructed goods as (in)alienable may be present in any society (Feinman and Garraty, 2010; Ziegler, 2012). All forms of exchange are socially embedded – governed by social rules that impose constraints (Blanton and Feinman, 2024; Feinman and Garraty, 2010). I reject the assumption that exchange among strangers was of little importance or imposed by Europeans in non-Western, pre-colonial societies (Blanton and Feinman, 2024; e.g., Dalton, 1982; Sahlins, 1972). Reciprocal gift exchange must be demonstrated in archeological cases and cannot be assumed based on Eurocentric biases. Finally, I reject arguments in which wealthier households are transformed into élites that “monopolized” or “controlled” local and/or non-local exchange just because public architecture (e.g., mounds) is present (e.g., Cobb, 1989; Muller, 1997). Political-economic control by an élite must be demonstrated empirically.

Accordingly, I argue that commodity exchange occurred in a variety of social and cultural settings and is not dependent on influence from capitalist economies (Feinman and Garraty, 2010; e.g., Dalton, 1982). In the following, I use evidence from Indigenous North America to demonstrate this.

Market exchange in indigenous North America

Turning to Native North America, I start with evidence that goods were socially constructed as alienable commodities before European contact. I then consider ethnohistoric and archeological evidence for market exchange of commodities, in Iñupiaq (Alaska), Hohokam (Arizona), and Cahokia (Illinois) by searching for evidence that: (1) goods were produced for exchange by ordinary households (“detached” specialization, Costin, 1991); (2) goods moved across boundaries and were consumed by ordinary households in a diversity of sites (patterned diversity/distributional approach, Hirth, 1998; Kepecs, 1997); and (3) strategies were employed to overcome cooperation problems and support cooperation in marketplaces.

Ethnohistoric evidence of alienable goods

The earliest contacts between Europeans and indigenous peoples of North America, across the length and breadth of the continent, are rife with examples of commodities exchange, in addition to gifting. These contacts occurred prior to the establishment of colonial domination and were carried out during short-term visitors (excepting Cabeza de Vaca).

According to La Florida (1995a, pp. 54–65), First Book shortly after Ponce de Leon failed in 1521, “… a pilot named Miruelo… was driven by a storm upon the coast of La Florida… where the Indians received him peaceably. In the course of… barter… they gave him some trifles of silver and a small quantity of gold… At this same time… two ships… came… upon the cape…named Santa Elena… The Spaniards went ashore… each displaying the things that they had. The Indians gave some fine marten-skins…, some irregular pearls… and a small amount of silver. The Spaniards also gave them their articles of trade….”

In May da Verrazzano (1524) anchored off the coast of Maine and observed, “If we wished at any time to traffick [sic]… they came to the sea shore… from which they lowered down by a cord… whatever they had to barter, … instantly demanding from us that which was to be given in exchange; they took from us only knives, fish hooks and sharpened steel” (da Verrazzano, 1524, p. 50).

Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, lost in Native North America (mostly in Galveston, TX) from 1,527 to 1,537, reported, “And with my trading and merchandize, I went inland… 40 or 50 leagues. The principal goods in my trading were pieces of whelk and their cores and seashells… Thus, this is what I took inland and in exchange and barter… I bought animal skins and red ochre, flints, paste and hard canes… and some tassels…” (Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, 2007, pp. 90–91) [Translated by the author]. He also stated, “… we bought ourselves two dogs and in barter for them we gave some nets, other things, and an animal skin (ibid:119) [Translated by the author]. When Núñez Cabeza de Vaca left Texas, he crossed the southern plains and met bison hunters, “…we called them the people of the Cows, because a great number of cows die near there; and because… they kill many of them… We also wanted to know from where they had gotten their maize and they told us from there, where the sun sets…” (ibid:148–149) [Translated by the author]. He then traveled west (into the greater Southwest), where he noted, “… to me they gave five emeralds made into arrow heads… I asked them from where they had come and they said they bring them from very high mountains that are there in the North and they buy them via barter for papagayo headdresses and feathers and they said that there, there were towns with lots of people and very large houses…” (ibid:152) [Translated by the author]. Here, Núñez Cabeza de Vaca encountered the trade networks that connect the Greater Southwest, including the Pueblos, and bison hunters of the Plains.

During the entrada of de Soto in the Southeast (1539–1,543), the Spaniards came across “… merchants who were accustomed to enter with their merchandize, selling and buying, many leagues into the interior country… It is not to be understood that the merchants went to seek gold or silver but to exchange some articles for others, which was the traffic of the Indians…” (La Florida, 1995b, p. 248, Fourth Book). They also mention finding, “…two Castilian axes for cutting wood, and a rosary of beads of jet and some margaritas of the kind that they carry from here [Spain] to barter with Indians. All this we believe they had obtained from barter with those who went with the Licenciado Ayllón” (Hernández de Biedman, 1995, p. 231).

In 1738, La Vérendrye, “…impressed with Mandan business skill, wrote [they] ‘know well how to profit by [trade] in selling their grains, tobacco, skins, and colored plumes which they know the Assiniboins prized highly’” (Ronda, 1991, p. 181). Lewis and Clark’s expedition reported, “… in late May, 1806… along the Clearwater River [Idaho]… Robert Frazer… encountered a Nez Perce woman. The two soon struck up a trade bargain. Frazer offered an old broken razor in return for two Spanish mill dollars… Along the Columbia, especially at The Dalles [they] saw mountains of dried salmon and heaps of goods ready for exchange” (ibid:177).

In July 1774, Captain Juan Pérez Hernández made first contact with the Haida of the Queen Charlotte Islands. On arrival, “about 200 souls came in these canoes… all around our ship, trading… for which they brought great precaution of mats, skins of various species of animals and fish, reed hats, fur caps and plumage of various types, and especially many bedspreads or woolen fabrics. Our people bought some of everything for clothing, knives and trinkets, various pieces” (Rodríguez, 2024). On August 9, 1774, they made contact on Vancouver Island, “…15 canoes arrived… they… began to trade… otter and other animal hides, painted reed hats with a pear on top of them, and woven of a kind of hemp. Our people traded old rags and limpet shells… and some knives for several of their pieces” (ibid).

In March 1778, Captain Cook arrived in Nootka Sound, “Upon our arrival… [we] immediately discovered a knowledge of traffic, and an inclination for it; and we were convinced afterward, that they had not received this knowledge from a cursory interview with any strangers… it seemed to be an established practice [sic]… in which they were… well skilled” (Hansen, 1993, p. 478). Wike (1951, p. 29) calls this the commercial acumen of Northwest Coast peoples, “… the peculiar characteristic of Northwest Coast commercial relations… came as a result of the fact that there was an indigenous demand for goods to serve as standard media of exchange – not simply for immediate consumption or use in production1. The choice of these goods was based upon already established, valuable native media: copper, native blankets and furs” (ibid: 29).

Kashevarov (1838) made the first intrusion into the interior of NW Alaska. On August 26 (1838), Kashevarov wrote, “… ‘At 3:00 we stopped at two winter sod huts 9 miles [14.5 kilometers] to the east of Cape Krusenstern. Here we found about 10 savages belonging to the Kyktagagmiut [Qikiqtagrunmiut] tribe[.] … From the local savages we purchased several loaches, … crowberries, cloudberries, bog whortleberries, and crowberries’ (VanStone, 1977, p. 62) …. Continuing eastward along the northern shore of Kotzebue Sound the Russians ‘passed some half-dozen sod huts scattered along the coast’ but did not encounter any large parties of Natives. At several of these huts they traded tobacco for fish” (Burch, 2005, p. 16).

Evidence for marketing in indigenous North America

Alaska

Information on market exchange among the Iñupiaq of NW Alaska can be dated to at least 1800, predating substantive contact with Europeans/Americans (Burch, 2005). Von Kotzebue (1821) reached his eponymous sound in 1816 and then returned south; a second Russian expedition reached the Icy Cap around 1820. The British arrived on the NW Coast of Alaska in 1826 (Beechy, 1832; Burch, 2005). They all stayed along the coast (Burch, 2005; VanStone, 1977). According to von Kotzebue (1821, p. 17), “… at the mouth of the [Mackenzie] river… a ship… manned by white men, visited this coast toward the year 1780…” Thus, interior NW Alaska was not reached in any significant way by Europeans until Kashevarov’s 1838 expedition (Burch, 2005).

Previous to this penetration, evidence demonstrates the Iñupiaq constructed goods as both gifts and commodities (Burch, 2005). Their vocabulary included aitchuq- (free gift), atuliq- (loan/gift with reciprocal expectation), pigriaq- (loan without expectation of return), simmiq-(barter – within social group direct exchange), tauqsiq- (offering goods for sale), tunilq-(unsolicited bid for goods), and trade between “trading partners” (niuviq-) (ibid: 20). The private nature of the goods was comprehended because tiglik- (theft) was acknowledged to occur (ibid:20).

Regarding the age of trade fairs, Burch (2005, p. 229) concluded, “… there is good reason to believe that a 19th-century-type system of international relations existed in northwestern Alaska [that was] roughly 800 years old by 1,600.” This conclusion is supported by archeological research. Long-distance trade across the Bering Straits, Alaska, and Western Canada increased at least between 1,400 and 1,500, if not earlier (Hickey, 1979; McCartney and Savelle, 1985), which well precedes Europeans/Americans. Prior to about the 1810s, indirect trade brought some Western goods into NW Alaska from across the Bering straits, through native networks; during the period from the 1810s to the 1820s, direct trade with Europeans/Americans was sporadic and limited to the coast (Burch, 2005). It was only in the 1830s that more sustained interaction occurred (ibid).

Trade fairs (summarized from Burch, 2005) were held annually at a number of locations during July–August, including Point Spencer, Sisualik (Kotzebue Sound), Sulliviak (NW Coast of Alaska), and Niġliq (mouth of Colville River), and lasted weeks. They were called katŋut (peaceful gatherings of people from different nations), niuviġiaq (where trading between partners occurred), or taaqsiġiaq (occasion with buying and selling on the open market). Importantly, these locations and their vicinities became neutral territories (thus, liminal spaces) accessible to all, during the trade fair season. Normally, they were the corporate territory of a particular nation and intruders were harassed or killed.

Although aware of it, Europeans did not reach the Sisualik fair in the early 19th century (Burch, 2005). Burch (2005) estimates that about 1,800 to 2,000+ people from 15 to 20+ nations attended this fair annually before European penetration. The Point Spencer fair was purportedly larger and older than the Sisualik fair (ibid). The fair at Niġliq was a slightly smaller affair, with 400–500 attendees (ibid). Whites began collecting reports on this fair from indigenous people with first hand experiences in the early 1850s (ibid).

Fairgrounds were heavily planned and organized, (ibid). As a European visitor to Sisualik in 1881 observed, “The camp was organized with almost military precision” (Nelson, 1899, p. 261). Just above the high-water mark, 60–70 umiaks formed a line along the coast and 75 yards inland a line of 200 kayaks were arranged parallel to the umiaks (ibid:261). Another 50 yards back, a line of conical lodges paralleled the kayaks (ibid:261). The fairgrounds also included a qargi (community hall) (Burch, 2005). Based on reports from the 1850s on Niġliq, the tents of the two nations that met there were arranged opposite one another on a flat piece of land, forming a demarcated area (fairgrounds), and in this space a qargi was erected (ibid).

Fairs were lively events. When newcomers arrived, dancing and feasting occurred and they preceded any trading (ibid). Sports and games were also plentiful, including wrestling, foot races, jumping, feats of strength and agility, spear-throwing, archery, kayak races, and football (ibid). Trade followed specific institutions, first feasting and dancing occurred, then trade partners got together and exchanged gifts, and, once these obligations had been fulfilled, open-market buying and selling ensued (ibid). Gift exchange between partners (niuviq-) focused on ensuring their needs were met and was strongly reciprocal; whereas, open-market trades were about making a shrewd deal (ibid). Market transactions were either initiated by sellers offering goods (tauqsiq-) and inviting bids (nallit-) or a buyer circulating and asking for something (tunilq-) (ibid). All market transactions involved commodity-commodity exchanges (simmiq-) in which price-making was established through haggling, which could last for hours (ibid). Europeans commented on the Iñupiaq’s obsession with haggling (which drove the Europeans crazy) and their commercial acumen (ibid). Yet, they (e.g., von Kotzebue and Beechey) refused to accept that the Iñupiaq were savvy traders and, without evidence, invented that it had been introduced by the Russians through the Chukchi (ibid) (which became the basis for two centuries of repeating this unfounded assumption – “turtles all the way down”).

Conflicts over trades or other slights often arose and family, kin, and tribe members intervened to keep situations from exploding (ibid). In cases where individuals could not be appeased, they had to take their conflicts outside the fairgrounds, so as not to upset trade (ibid).

Trade fairs moved goods between the coast and the interior. Interior groups acquired seal and whale products, including oils and seal skins for rope, towlines, boot soles, water bags, snowshoe webbing, beluga sinew and blubber, walrus ivory, etc. (ibid). Interior products, including furs (beaver, bear, fox, lynx, marmot, marten, mink, otter, wolf, etc.), caribou and dall sheep products, stone points, chert, graphite, hematite, labret stones, marble, nephrite, finished whetstones, plant products, clothing, musk ox hair, dried fish, and feathers reached coastal groups (ibid).

Southwest

Indigenous trade fairs in the Southwest linked pueblos and nomadic hunters. Among the most famous of these were the Taos and Pecos fairs. The Taos involved a variety of groups, including Apache, Ute, and Comanche tribes, as well as Puebloan peoples (Cunningham and Miller, 1999). The fair was a large, lively event featuring market exchange, horse races, athletic competitions, gambling, feasting, and dancing (ibid). Commodity exchanges involved haggling over goods such as buffalo hides, trade cloth, horses, buckskin, rifles, and captives (ibid). As we saw earlier, Núñez Cabeza de Vaca encountered groups on the plains and in the Southwest that engaged in commerce, which indicates these fairs had great historic depth.

Archeological evidence for market exchange in the Southwest comes from Central Arizona. During the middle Sedentary Period (AD 1000–1,070), a high degree of specialization (defined as production for exchange) in handicrafts emerged at the regional level (e.g., Abbott, 2010; Abbott et al., 2007). Ceramic petrography demonstrated that 90% of ceramics were produced in only five places in the Basin, and archeological analysis shows that these places specialized in certain vessel forms (ibid): (1) potters at the site of Las Colinas, north of the Salt River, produced plainware bowls and jars; (2) potters in sites at the SW end; and (3) NE end of the South Mountains produced large, thick ollas; (4) potters at Snaketown and nearby sites produced decorated red-on-buff bowls and small jars; and (5) potters in the middle Gila River produced plainware bowls and jars (ibid). Production was decentralized (ibid; cf. detached production in Costin, 1991).

In terms of plainwares, the Salt Valley north of the river was supplied by Las Colinas and the Gila Valley potters, while the Salt Valley south of the river was supplied by the middle Gila River producers (ibid). The Scottsdale canal system was supplied by both production areas and thick ollas from the South Mountains reached Las Colinas. At Snaketown, red-on-buff was produced and distributed to every site in the region, large or small, in the same ratio of bowls to jars (ibid).

This horizontal distribution of pottery, along with specialization at the household scale, corresponds with patterned diversity/distributional approach (Hirth, 1998; Kepecs, 1997). Patterned diversity/distributional approach is a recognized archeological marker of market exchange, “… a supplier’s wares can reach sparsely settled, low-demand areas when buyers are drawn from the countryside to a market… [which] creates a homogenizing effect on the distribution of goods…barter between strangers almost certainly characterized the distribution of Hohokam ceramics” (Abbott et al., 2007, pp. 469–470). Access to non-local commodities cross-cut social sectors, indicating they were not monopolized by an “élite” (ibid).

Palo Verde Ruin, 35 km north of the Salt River, offers excellent data on consumption. Here, 200–300 people occupied approximately 50 pithouses at any moment, with a total of about 100 at the site (Abbott, 2010). They acquired pottery from the lower Salt River valley, obsidian from NW and N Arizona, and imported stone bowls, censers, plummets, ground stone axes, stone jewelry, turquoise, shell ornaments, points, argillite, steatite, and galena (ibid). They specialized in the production and export of meat, hides, and sinew from large game and manos and metates (ibid). Additionally, some residents were specialized traders (“middlemen”) who amassed shell artifacts for trade, not consumption (ibid).

Abbott (2010; Abbott et al. 2007) confirms the rise of market exchange was tied to regional integration associated with the expansion of ballcourts and associated rituals over 80,000 km2. At 194 Hohokam sites of all sizes, 238 ballcourts were constructed alongside plazas (ibid). Wilcox (1991) demonstrates that ballgames were tied to a ritual calendar, which would have concentrated large numbers of people (spectators and participants) from diverse settlements at ballcourt sites periodically (Abbott, 2010; Abbott et al., 2007). These large concentrations of people created opportunities for barter of private goods between strangers, in which price was established through haggling (ibid). Plazas probably functioned as marketplaces where face-to-face market exchanges occurred (cf. Feinman and Garraty, 2010). Obsidian, turquoise, argillite, galena, steatite, serpentine, marine shell, tabular knives, manos and metates, meat and hides from big game (including bison from the plains) were imported and distributed across the Hohokam region in both large and small settlements, while cotton and Hohokam-style marine shell bracelets were exported to Chaco and beyond (ibid, Gasser, 1978; Mattson, 2016).

Southeast

Descriptions from early Spanish entradas (see above) indicate that market exchange was likely widespread prior to contact. Archeological research at Cahokia and in its hinterlands demonstrates the specialized production and distribution of chert hoes, fineware pottery, shells, comestible salt, and minerals in the American Bottom and adjacent zones dated to at least the Middle Mississippian, especially the Sterling Phase (A. D. 1,100–1,200):

1. Specialized salt production occurred at the Great Salt Spring in southern Illinois (about 218 km SE of Cahokia) (as well as at other salt springs). Salt production began here about A. D. 800 and continued to contact, but production was most intensive during Cahokia’s hegemony (Muller, 1997). Research demonstrates that at Cahokia’s height, specialists occupied the site seasonally, during the fall to late winter, to produce salt (ibid). They lived in temporary housing on the bluff edge above the spring’s floodplain (ibid). Production at the site was highly specialized with only scant evidence for other activities (ibid). Given both sedentism and the distance from Cahokia and East St. Louis, it is unlikely that people from the American Bottom traveled to the site to produce their own salt. Producers probably came from nearby Mississippian villages, produced massive amounts of salt for exchange during the late winter, and then returned home (cf. ibid).

2. The specialized production of chert hoes is also evident during Cahokia’s hegemony (Cobb, 1989; Koldehoff and Brennan, 2010; Muller, 1997). One of the most important sources for chert hoes was Mill Creek, located about 200 km south of Cahokia. The chert source itself has little evidence of occupation; material was collected, reduced into nodules, and transported to Mississippian settlements within about 10 km of the quarry, where it was worked into finished hoes and other items (Cobb, 1989; Muller, 1997). These sites, which include both large settlements with mounds (e.g., Linn) and smaller sites with and without mounds (e.g., Hale), are distinguished from other Mississippian sites by dense debitage deposits (ibid). Thus, chert working was more intensive at these sites than at typical Mississippian sites. Specialists produced hoes, as well as eccentric forms such as maces, spatulate celts, Duck River style “swords,” and Ramey knives (Cobb, 1989). Large bifaces were also produced by specialists at Crescent (Burlington – 45 km west of Cahokia) and Dover (TN) (Koldehoff and Brennan, 2010). Importantly, this production was decentralized (detached) (Cobb, 1989; Muller, 1997).

3. Specialized shell bead production occurred throughout Cahokia, at East St. Louis, and in neighboring villages. Specialization is evidenced via assemblages of microdrills, microflakes, hammers, anvils, u-shaped and beveled sandstone abraders, and shell debitage (Kozuch, 2022; Skousen, 2020). They occur in a range of contexts, some associated with mounds, large residences (wealthy households?) or communal structures distant from mounds, and ordinary houses in villages (ibid), thus “élite” participation occurred in some cases, but not all (Kozuch, 2022; cf. Skousen, 2020).

4. Specialized production of fineware pottery, including Ramey Incised, Mound Place Incised, Wells Engraved, Kersey Incised, Yankeetown Incised and Early Caddo occurred in several places in the American Bottom, especially Cahokia and East St. Louis. But, workshops have not been located (Wilson, 1999). Petrographic and INAA indicate production in greater Cahokia (Lambert and Ford, 2023; Wilson, 1999).

On the distribution and consumption side, finished Mill Creek hoes were transported in bulk to major centers, where they were amassed unused for future distribution as utilitarian goods (Cobb, 1989). From these centers, Mill Creek hoes were widely distributed across social sectors and geographical territory; rural households throughout Cahokia’s hinterlands were supplied with them. “During the interval from about A. D. 900–1,400, Mill Creek chert… tools or flakes can be found on all categories of Mississippian sites in those regions adjoining and including southern Illinois… utilitarian [hoes] and exotic bifaces, and/or resharpening flakes occur on sites from eastern Oklahoma to Ohio… and from Wisconsin to Mississippi…” (Cobb, 1989). A Mill Creek “sword” was found in a small house in the Hazel site (AR) and Ramey knives occur in a range of households and villages (ibid). At the Schlid site (near Eldred, IL – 106 km north of Cahokia), Ramey knives were recovered from ordinary burials in the village cemetery (Perino, 1962). During the Stirling phase (AD 1100–1,200), fineware is distributed throughout rural areas in Cahokia’s hinterland (Wilson, 1999). At a small Sterling-phase village (Audrey site) near the Schlid site, a Mill Creek hoe, marine shell beads, galena, and a Caddo sherd (made in Texas) were recovered from a residential area (Block 6) (Delaney-Rivera, 2004). The author identifies one structure in this block as “élite” but offers no evidence for this conclusion (ibid). Clearly, these decentralized and homogenous patterns align with patterned diversity/distribution approach (Hirth, 1998; Kepecs, 1997; Abbott et al., 2007).

Plazas had multiple functions in Mississippian settlements, including serving as marketplaces. Mississippian towns and villages generally followed a standardized plan marked by a ring of houses, one or more rows deep, surrounding a plaza-mound complex (Cook, 2011, 2017; Kowalewski and Thompson, 2020). Plaza areas, even in small villages, were comparatively large and accessible. Plazas, in larger settlements, were comparatively more accessible from outside the site and most were not palisaded during the Sterling phase (Kowalewski and Thompson, 2020). Thus, large villages, towns, Cahokia, and East St. Louis probably hosted periodic markets, which is evidenced by the stockpiling of trade goods (e.g., finished hoes/bifaces) at larger sites. Furthermore, given the decentralized nature of distribution, political/religious officials in such sites were positioned to provide market governance and collect market taxes.

Discussion and conclusion

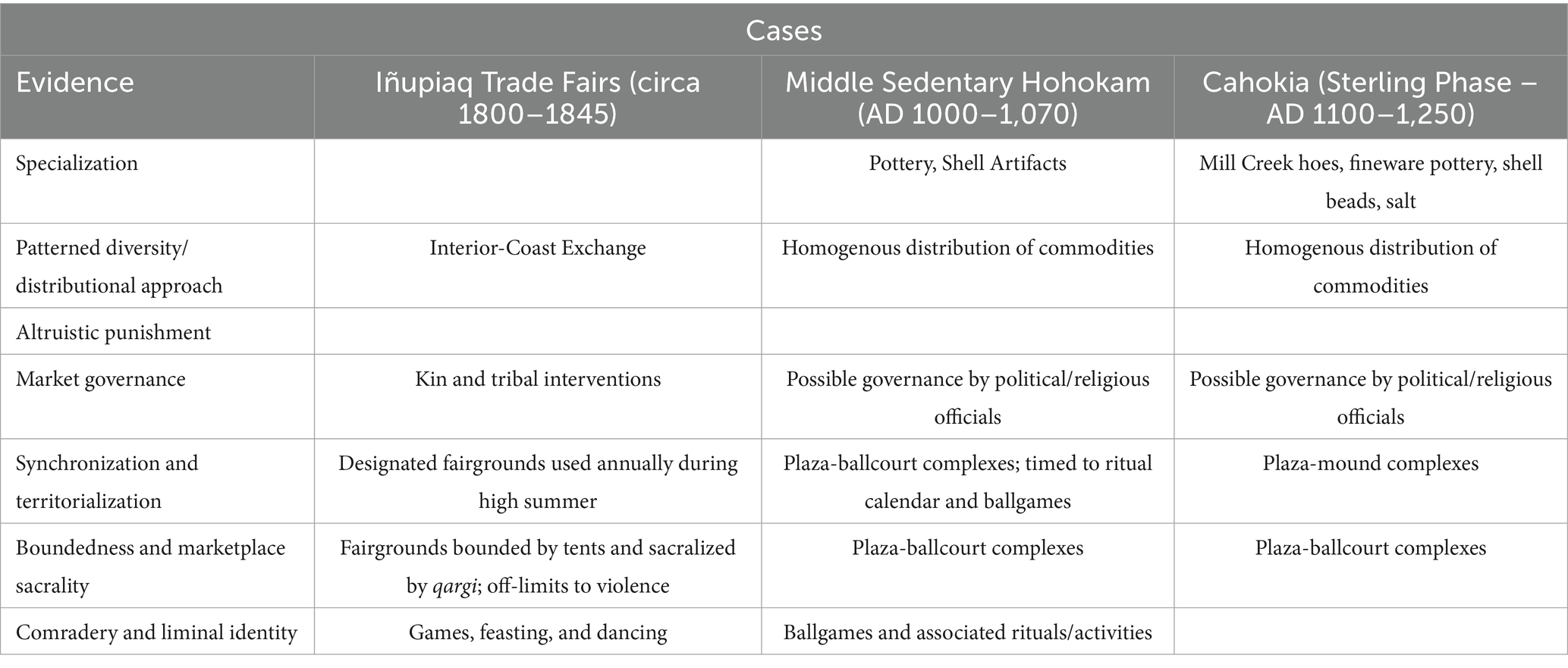

Considering these cases, I see extensive evidence of specialization, patterned diversity/distribution approach, and strategies to overcome cooperation problems and build trust so that commodities exchanges, including market exchange and non-market exchange, could occur (Table 2). In the case of the Iñupiaq, while evidence of specialization is limited, the transfer of coastal goods (e.g., seal and whale oils, seal skins for rope, towlines, boot soles, water bags, snowshoe webbing, beluga sinew and blubber, walrus ivory, etc.) to the interior and interior goods (furs, caribou and dall sheep products, metal, stone points, chert, graphite, hematite, labret stones, marble, nephrite, finished whetstones, plant products, clothing, musk ox hair, dried fish, feathers) to the coast is attested to in the documents and in the archeological record. As a form of marketplace governance, family members, kin, and tribe members were responsible for keeping individuals calm and diffusing conflicts; if they failed, individuals had to settle their conflicts away from the fairgrounds (sacrality of fairgrounds). In terms of synchronization and territorialization, trade fairs occurred year after year at the same location (e.g., Point Spencer, Sisualik, etc.) and the same time (July–August). Camps were formally arranged to create bounded spaces that symbolically marked the boundaries of the fairgrounds and a qargi was erected (sanctification) (e.g., Sisualik, Niġliq). Fairgrounds (market places) and surrounding areas were liminal spaces where violence was taboo, allowing enemy groups to meet peacefully. Finally, games, feasting, and dancing were enacted to create camaraderie and liminal identities of “friendship.”

For Hohokam, specialization and patterned diversity/distributional approach are visible archeologically for a number of commodities, especially ceramics and marine shell artifacts, but also obsidian, turquoise, argillite, galena, etc. Synchronization and territorialization, as well as boundedness and marketplace sacrality were achieved by connecting markets to the ritual calendar and ballgame, which were materialized in the plaza-ballcourt complexes in 194 Hohokam sites. By tying market exchange to ballcourts in large sites with formal spaces (plazas), I infer that political and/or religious officials were positioned to provide marketplace governance. Tying market exchange to ballgames and adjacent plazas placed it within a liminal space where games and associated rituals (including feasting) would have contributed to moral behavior, camaraderie, and liminal identities.

Archeological evidence from Cahokia and its hinterlands provides evidence of the specialized production of Mill Creek hoes, bifaces, and other exotics, bifaces at other chert quarries, fineware pottery, shell beads, and salt, as well as quarrying of minerals (e.g., galena, etc.). These goods are distributed fairly homogeneously across social sectors and the geographic territory of Cahokia’s hinterlands, including reaching small rural villages and hamlets (patterned diversity/distributional approach). Synchronization and territorialization as well as boundedness and marketplace sacrality were embodied in the plaza-mound complex. Plazas offer a fixed location where market exchange could have occurred and the construction of mounds along the edges of plazas demarcated them as distinctive/defined spaces and provided sacrality and liminality. If Sterling-phase plazas functioned as marketplaces, they were optimally, and possibly intentionally, placed for governance by political/religious officials.

If we suspend Eurocentric ideas about native peoples of North America, many of which come from the Contact/Colonial era when they were considered “savages” (by incredibly savage Whites, ironically enough), as well as projecting 20th-century ethnographies back centuries, there is substantial evidence that commodity exchange occurred, including market exchange. Yet, we must also separate commodity exchange mechanisms, especially market exchange, from the “capitalist impulse” and the entangling of the two, which has led to the conclusion that markets are “unnatural” and/or bad (e.g., Sahlins, 2008; cf. Blanton and Fargher, 2016; Blanton and Feinman, 2024; Feinman and Garraty, 2010). Nowhere in the cases presented is it necessary to assume that market exchange was enacted with the goal of maximization, that profit-making is a definitional character of market exchange, that rationalization worthy of homo economicus was present, or that free riding on unearned profits is always an attribute of commodity exchange.

By unburdening market exchange from this cultural baggage, heaped upon it by Western culture (Blanton and Fargher, 2016), and understanding it as a commodity exchange mechanism that moves private goods between individuals without creating reciprocal obligations, we can find much archeological and historical data to support its presence in Native North America. This evidence includes not only the movement of goods across landscapes, but mechanisms of social embedding (institutions) to solve cooperation problems in the absence of reciprocal friendships or in addition to them (cf. Blanton and Feinman, 2024; Feinman and Garraty, 2010). Furthermore, in some cases it may provide a better framework for understanding the movement of goods (both raw materials and handicrafts) than reciprocity or vague notions of “élite” control. This is not to say that other forms of exchange (e.g., reciprocal gifting) were absent. In some instances, “free” gifts were offered as a precursor to various forms of commodities exchange. Finally, incorporating Native North America as another geographical area where market exchange occurred serves to enrich anthropological research on the deep history of markets.

Author contributions

LF-N: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

I thank the section editors, Gary Feinman and Richard Blanton, along with three reviewers, for stimulating me to think deeply about the content of this paper and for suggesting additional references, which significantly improve it. However, all errors or omissions are the sole responsibility of the author.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used to check corresponded between references cited and in-text citations.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Commodity money.

References

Abbott, D. R. (2010). “The rise and demise of marketplace exchange among the prehistoric Hohokam of Arizona” in Archaeological approaches to market exchange in ancient societies. Eds. B. L. Stark and C. P. Garraty (Boulder: Univ. Press Colo.), 61–83.

Abbott, D. R., Smith, A. M., and Gallaga, E. (2007). Ballcourts and ceramics: the case for Hohokam marketplaces in the Arizona desert. Am. Antiq. 72, 461–484. doi: 10.2307/40035856

Acheson, J. M. (1994). “Welcome to Nobel country: a review of institutional economics” in Anthropology and institutional economics, vol. 12. Ed. J. M. Acheson (Lanham: Univ. Press Amer.), 3–42.

Barnes, M., Cousens, L., and MacLean, J. (2017). Trust and collaborative ties in a community sport network. Manag. Sport Leis. 22, 310–324. doi: 10.1080/23750472.2018.1465840

Beechy, F. (1832). Narrative of a voyage to the Pacific and bearing’s strait. Philadelphia: Carey and Lea.

Blanton, R. E. (1996). “The basin of Mexico market system and the growth of empire” in Aztec imperial strategies. Eds. F. F. Berdan, R. E. Blanton, E. Hill Boone, M. G. Hodge, M. E. Smith, and E. Umberger (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks), 47–84.

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2016). How humans cooperate: confronting the challenges of collective action. Boulder: Univ. Press Colo.

Blanton, R. E., and Feinman, G. M. (2024). New views on price-making markets and the capitalist impulse: beyond Polanyi. Front. Hum. Dyn. 6:1339903. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2024.1339903

Bohannan, P. (1955). Some principles of exchange and investment among the Tiv. Am. Anthropol. 57, 60–70. doi: 10.1525/aa.1955.57.1.02a00080

Burch, E. S. (2005). Alliance and conflict: The world system of the Iñupiaq Eskimos. Lincoln: Univ. Neb. Press.

Chapman, A. (1980). Barter as a universal mode of exchange. Homme 20, 33–83. doi: 10.3406/hom.1980.368100

Cobb, C. R. (1989). An appraisal of the role of Mill Creek chert hoes in Mississippian exchange systems. Southeast. Archaeol. 8, 79–92.

Comaroff, J. L. (1982). Dialectical systems, history and anthropology: units of study and questions of theory. J. South. Afr. Stud. 8, 143–172. doi: 10.1080/03057078208708040

Cook, R. A. (2011). Sun watch: Fort ancient development in the Mississippian world. Tuscaloosa: The Uni. of Al. Press.

Cook, R. A. (2017). Continuity and change in the native American Village: Multicultural origins and descendants of the fort ancient culture. Cambridge: Cam. Univ. Press.

Costin, C. L. (1991). Craft specialization: issues in defining, documenting, and explaining the organization of production. Arch. Math. Log. 3, 1–56.

Cunningham, E., and Miller, S. (1999). Trade fairs in Taos: prehistory to 1821. El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro 2 87–102 BLM Santa Fe

da Verrazzano, G. (1524). The voyage of John de Verazzano. Coll. New York Hist. Soc. 2d. Ser. 1, 41–67.

Delaney-Rivera, C. (2004). From edge to frontier: early Mississippian occupation of the lower Illinois River valley. Southeast. Archaeol. 32, 41–56.

Fargher, L. F., and Blanton, R. E. (2021). “Peasants, agricultural intensification, and collective action in premodern states” in Power from below in premodern societies: The dynamics of political complexity in the archaeological record. Eds. T. L. Thurston and M. Fernández-Götz (Cambridge: Cam. Univ. Press), 157–174.

Feinman, G. M., and Garraty, C. P. (2010). Preindustrial markets and marketing: archaeological perspectives. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 39, 167–191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.012809.105118

Gasser, R. E. (1978). Hohokam subsistence: A 2,000 year continuum in the indigenous exploitation of the lower Sonoran Desert. Southwestern Region: USDA Forest Service.

Geertz, C. (1979). Meaning and order in Moroccan society: three essays in cultural analysis. Cambridge: Cam. Univ. Press.

Hansen, D. B. (1993). Captain James Cook's first stop on the northwest coast: by chance or by chart? Pac. Hist. Rev. 62, 475–484. doi: 10.2307/3641108

Hernández de Biedman, L. (1995). “Relation of the island of Florida” in the De Soto chronicles, 2 volume set: The expedition of Hernando de Soto to North America in 1539–1543. Eds. L. A. Clayton, V. J. KnightJr., and E. C. Moore (Tuscaloosa: Univ. Al. Press).

Hickey, C. G. (1979). “The historic Beringian trade network: its nature and origins” in Thule Eskimo Culture: An Anthropological Retrospective. Ed. A. P. McCartney (Ottawa: Arch. Surv. Can., Paper No. 88), 411–434.

Hirth, K. G. (1998). The distributional approach: a new way to identify marketplace exchange in the archaeological record. Curr. Anthropol. 39, 451–476. doi: 10.1086/204759

Humphrey, C., and Hugh-Jones, S. (1992). “Introduction: barter exchange and value” in Barter, exchange and value: an anthropological approach. Eds. C. Humphrey and S. Huge-Jones. (Cambridge: Cam. Univ. Press), 1–20.

Joubert, Y. T., and De Beer, J. J. (2011). Benefits of team sport for organisations. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport, Phys. Educ. Recreation. 33, 59–72.

Kepecs, S. (1997). Native Yucatán and Spanish influence: the archaeology and history of Chikinchel. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 4, 307–329. doi: 10.1007/BF02428066

Koldehoff, B., and Brennan, T. (2010). Exploring Mississippian polity interaction and craft specialization with Ozark chipped-stone resources. Miss. Arch. 71, 131–164.

Kowalewski, S. A., and Thompson, V. D. (2020). Where is the southeastern native American economy? Southeastern Archaeol. 39, 281–308. doi: 10.1080/0734578X.2020.1816599

Kozuch, L. (2022). Shell bead crafting at greater Cahokia. N. Am. Archaeol. 43, 64–94. doi: 10.1177/01976931211048205

La Florida, (1995a). “First book” in The De Soto chronicles, 2 volume set. Eds. L. A. Clayton, V. J. KnightJr., and E. C. Moore (Tuscaloosa: Al. Press).

La Florida, (1995b). “Fourth book” in The De Soto chronicles, 2 volume set. Eds. L. A. Clayton, V. J. KnightJr., and E. C. Moore (Tuscaloosa: Al. Press).

Lambert, S. P., and Ford, P. A. (2023). Understanding the rise of complexity at Cahokia: evidence of nonlocal Caddo ceramic specialists in the east St. Louis precinct. Am. Antiq. 88, 361–385. doi: 10.1017/aaq.2023.28

Mattson, H. V. (2016). Ornaments as socially valuable objects: jewelry and identity in the Chaco and post-Chaco worlds. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 42, 122–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2016.04.001

Mauss, M. (1954). The gift: forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies. New York: Free Press.

McCartney, A. P., and Savelle, J. M. (1985). Thule eskimo whaling in the Central Canadian Arctic. Arc. Anthro. 22, 37–58.

Nelson, E. W. (1899). The Eskimo about Bering Strait. Bur. Amer. Ethno. Ann. Rep. 18. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office).

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cam. Univ. Press.

Ostrom, V., and Ostrom, E. (1971). Public choice: a different approach to the study of public administration. Public Adm. Rev. 31, 203–216. doi: 10.2307/974676

Ostrom, E., and Ostrom, V. (1977). Public economy organization and service delivery. Paper prepared for the “financing the Regional City project” of the metropolitan fund, presented at the University of Michigan, Dearborn, Michigan, October 20, 1977

Perino, G. (1962). Evidence of the old village culture in the lower Illinois River valley. Cent. Stat. Arch. J. 9, 132–135.

Polanyi, K. (1957). “The economy as an instituted process” in Trade and Markets in the Early Empires (New York: Free Press), 243–269.

Rezavi, S. A. N. (2015). Bazars and markets in medieval India. Stud Peoples History 2, 61–70. doi: 10.1177/2348448915574360

Rodríguez, O.G. (2024). The expedition of Juan José Pérez Hernández. Hispanic origins of Oregon. Available online at: https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/hispanicoriginsoregon/chapter/the-expedition-of-juan-jose-perez-hernandez-and-the-haida-tribes/ (Accessed May 05, 2025).

Ronda, J. P. (1991). ‘The great mart of all this country’: Lewis and Clark and Western trade networks. New dimensions in ethnohistory: papers of the second Laurier Conference on Ethnohistory and Ethnology. Eds. B. Gough and L. Christie New (Univ. Ottawa P., Ottawa), 175–189. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv16sxg.12

Sahlins, M. D. (1981). Historical metaphors and mythical realities: Structure in the early history of the Sandwich Islands kingdom. Ann Arbor: Univ. Mich. Press.

Simon, H. A. (1955). A behavioral model of rational choice. Quart. J. Econ. 69, 99–118. doi: 10.2307/1884852

Skinner, G. W. (1964). Marketing and social structure in rural China, part I. J. Asian Stud. 24, 3–43. doi: 10.2307/2050412

Skousen, B. J. (2020). Skilled crafting at Cahokia's fingerhut tract. Southeastern Archaeol. 39, 259–280. doi: 10.1080/0734578X.2020.1782665

Uchendu, V. C. (1967). Some principles of haggling in peasant markets. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 16, 37–50. doi: 10.1086/450268

Van den Eijnde, F. (2018). “Feasting and polis institutions: an introduction” in Feasting and polis institutions. Eds. F. van den Eijnde, J. H. Blok, and R. Strootman (Brill, Leiden), 1–27.

VanStone, J. W. (1977). AF kashevarov's coastal explorations in Northwest Alaska, 1838 : Fieldiana, 69.

von Kotzebue, O. (1821). A voyage of discovery, into the south sea and beering's straits, for the purpose of exploring a north-east passage. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown.

Weiner, R. S. (2018). Sociopolitical, ceremonial, and economic aspects of gambling in ancient North America: a case study of Chaco canyon. Am. Antiq. 83, 34–53. doi: 10.1017/aaq.2017.45

Wike, J.A. (1951). The effect of the maritime fur trade on northwest coast Indian society. PhD Disseration, Columbia University

Wilcox, D. R. (1991). “The Mesoamerican ballgame in the American southwest” in The Mesoamerican ballgame. Eds. V. L. Scarborough and D. R. Wilcox (Tucson: University of Arizona Press), 101–126.

Wilson, G. D. (1999). The production and consumption of Mississippian fineware in the American bottom. Southeast. Archaeol. 18, 98–109.

Keywords: Native North America, private goods, cooperation, Iñupiaq, Hohokam, Cahokia, market exchange

Citation: Fargher-Navarro LF (2025) Europe and the people without market history. Front. Hum. Dyn. 7:1585721. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2025.1585721

Edited by:

Gary M. Feinman, Field Museum of Natural History, United StatesReviewed by:

Jennifer Birch, University of Georgia, United StatesJacob Holland-Lulewicz, The Pennsylvania State University (PSU), United States

Matthew Pailes, University of Oklahoma, United States

Copyright © 2025 Fargher-Navarro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lane F. Fargher-Navarro, bGZhcmdoZXJuYXZhcnJvQHBhc3Rmb3VuZGF0aW9uLmVkdQ==

Lane F. Fargher-Navarro

Lane F. Fargher-Navarro