- 1Department of Christian Archaeology and Byzantine Art History, University of Marburg, Marburg, Germany

- 2ArchDepth Research Group, Bonn Center for Dependency and Slavery Studies, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany

This article reconsiders the nature of marketplace exchange in premodern economies by comparing two distinct cases: the monetized system of the Byzantine Empire and the exchange networks of the prehispanic central Andes. We compare these two contrasting cases to explore the applicability of a spectrum-based approach to markets. Drawing on theories from institutional economics, economic anthropology, and political economy, the paper challenges the traditional market/non-market dichotomy that has long dominated the field. By adopting a comparative and interdisciplinary methodology, we argue for a more flexible and integrated framework that recognizes the diversity and embeddedness of exchange systems across cultures. Using archaeological and historical evidence, we examine how coin-based markets in Byzantium coexisted with legal institutions and state infrastructure, while Andean exchange, though largely lacking formal currency or marketplaces, often relied on socially embedded networks. Our study demonstrates that market-like behavior does not require monetization or formal institutions and that both regions offer valuable insights into the resilience and variability of preindustrial markets and economic systems. This analysis contributes to broader debates in economic archaeology and history by reframing what constitutes a “market” and advocating for a spectrum-based understanding of exchange mechanisms across time and space.

1 Introduction

Marketplace exchange, encompassing the buying, selling, and trading of goods and services, has been a central feature of human societies throughout history. From ancient bazaars to modern globalized markets, these hubs have facilitated economic activity, cultural exchange, and social interaction. However, the study of premodern marketplace exchange is fraught with theoretical complexities, often polarized between views emphasizing market importance for economic development and those prioritizing non-market factors like redistribution and reciprocity (Polanyi, 1957; Temin, 2012; Earle, 2017). As Feinman and Garraty (2010) highlight, there is “little agreement concerning their history and diversity,” and different academic disciplines often approach these exchange systems from “diametrically opposed perspectives that impede cross-disciplinary dialog.” Smit (2022) further notes that archaeologists have historically been reluctant to fully engage with market studies, often due to the enduring legacy of the formalist-substantivist debate.

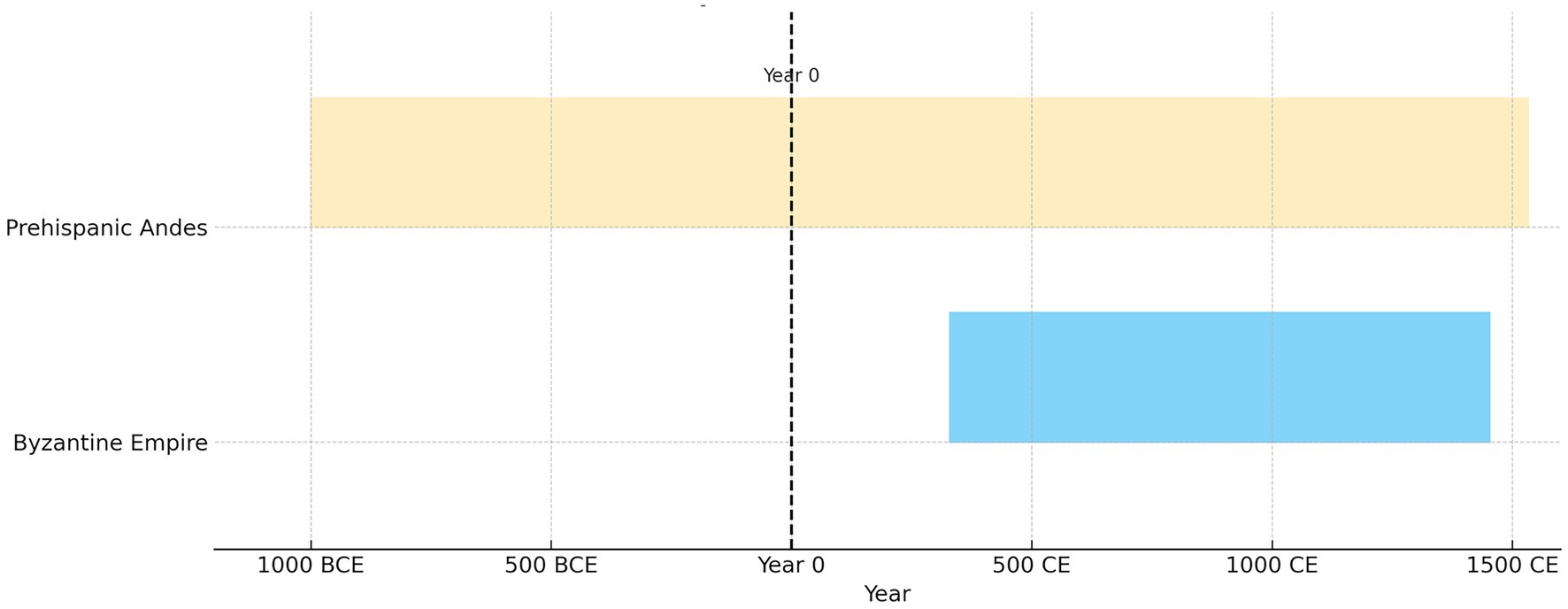

This article aims to transcend these theoretical divides by undertaking a comparative analysis of marketplace exchange in two distinct historical contexts: the Byzantine Empire and the prehispanic central Andes (Figures 1, 2). These regions offer contrasting case studies: the Byzantine economy is generally understood to have possessed a developed monetary system and sophisticated markets, while the prehispanic Andes has historically been characterized by an “anti-market mentality” (Cook, 1966), favoring interpretations of exchange based on barter and social embeddedness (Stanish, 2010; Stanish and Coben, 2013). Recent scholarship, however, suggests a more nuanced view for both regions, challenging the “oversimplified ‘market/no-market dichotomy’” (Feinman and Garraty, 2010; Wilk, 2018).

Figure 1. Map showing the Byzantine world (Eastern Mediterranean and surrounding regions) and the central prehispanic Andes.

Figure 2. Timeline considered for the comparative analysis of markets between Byzantium and the prehispanic Andes.

In the broader field of comparative economic history, archaeological and historical evidence attests to the presence of marketplaces and trade in regions such as ancient Egypt (James, 1984; Moreno García, 2021), while premodern China—from the Han Dynasty through the Late Imperial period—exhibited significant economic activity beyond centralized governmental control (Loewe, 2005, 2006; Blanton and Fargher, 2008; Feinman et al., 2019; Blanton and Feinman, 2025). Preindustrial economies, as de Pleijt and van Zanden (2024) demonstrate for Europe, also experienced varied growth patterns, from stagnation to significant increases in living standards, further underscoring their inherent diversity (see also Blanton and Fargher, 2016).

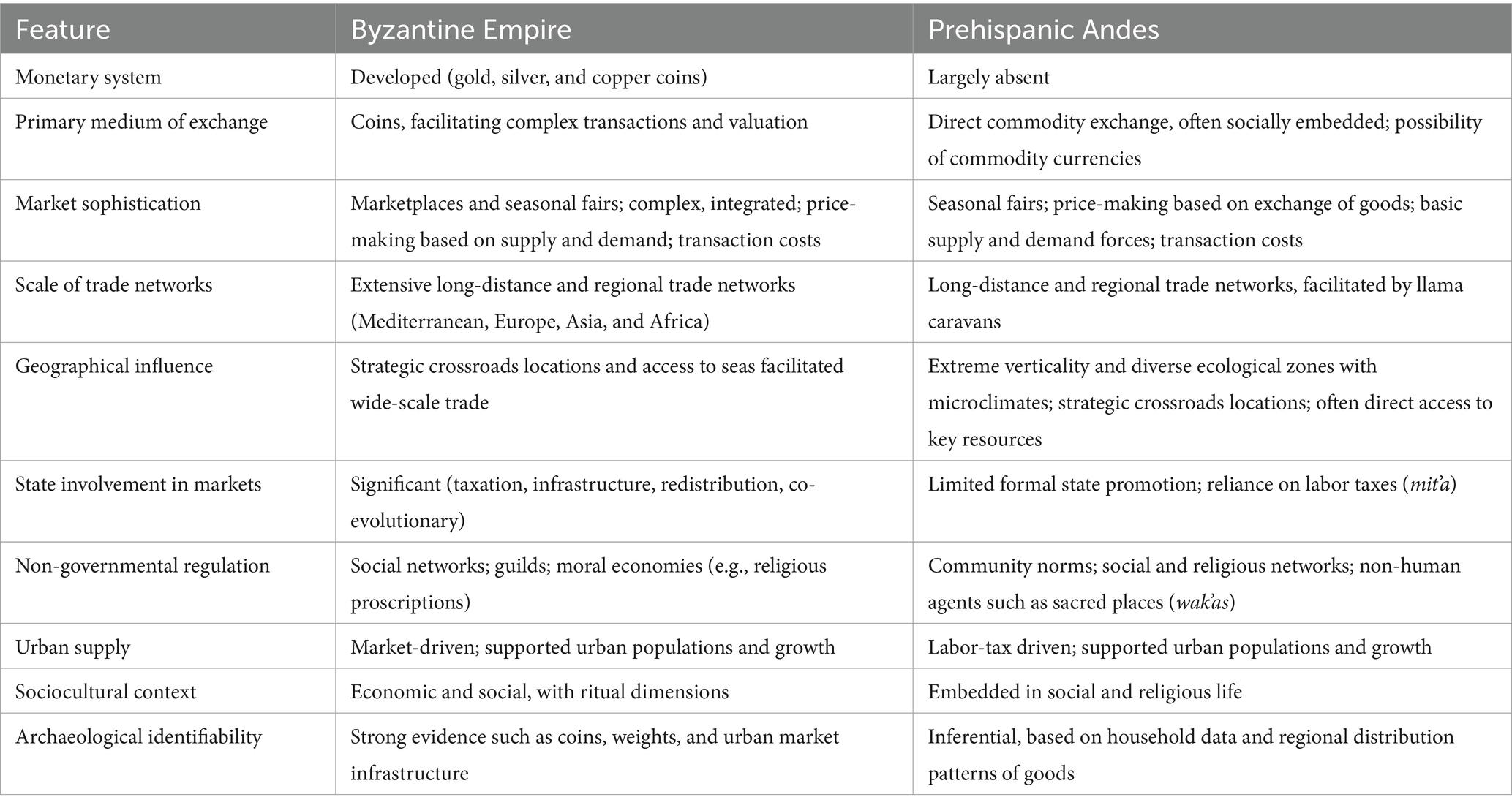

The explicit comparison between the Byzantine Empire and the prehispanic central Andes is crucial for illuminating the diverse manifestations of marketplace exchange across vastly different historical and cultural settings (Table 1). While these two regions present a stark contrast in terms of monetary systems, state structures, and geographical contexts, the goal of this cross-regional, cross-cultural analysis is not to force a false equivalence. Instead, by examining such contrasting cases, we aim to test the robustness of theoretical frameworks, highlight the spectrum of market exchange and integration, and uncover underlying mechanisms that shaped economic behavior. This comparative approach allows us to move beyond Eurocentric or regional biases, revealing the challenges and values of identifying and interpreting market phenomena in contexts where direct parallels are scarce.

Our key research questions guiding this comparative study are:

1. How persistent was marketplace exchange in premodern history?

2. Did markets and modes of exchange evolve differently over time, and why?

3. What constitutes a market?

4. What evidence exists for the presence of prehistoric and historic marketplaces?

5. How can markets be identified in the archaeological record?

6. What factors contributed to the existence and persistence of marketplace exchange in these regions, and what types of goods were exchanged?

By examining archaeological evidence, historical records, and economic systems through a comparative lens, and integrating insights from various theoretical frameworks, this research seeks to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and sociocultural significance of marketplace exchange. We aim to provide a holistic understanding of how market dynamics shaped economic institutions and social relationships over time, ultimately contributing to an interdisciplinary dialog on the historical evolution of marketplace exchange.

2 Theoretical approaches to marketplace exchange

The concept of the “market” is multifaceted and subject to varied interpretations across academic disciplines. For our analysis, it is crucial to clarify key terms and theoretical approaches. A market is generally defined as an abstract organization where goods, services, labor, land, capital, and/or information are exchanged based on supply and demand dynamics, not necessarily requiring a physical location or monetary system (Pryor, 1977; Garraty, 2010). A marketplace refers to a specific physical location for such exchanges, often providing additional socioeconomic purposes. In addition, a marketplace serves as a valuable source of information about prevailing market conditions (e.g., Blanton and Fargher, 2016, p. 73). Market exchange is conceptualized as economic transactions where the forces of supply and demand are visible and where prices and exchange equivalencies were not fixed but negotiated, context-dependent, and often shaped by local norms and power relations. In some cases, marketplaces were interlinked across regions, while in others they functioned as interstitial spaces—often emerging along the boundaries of competing polities (Blanton, 2013). Finally, barter markets involve direct exchange of commodities and services without the use of a medium of exchange (currency) (Hirth, 1998; Garraty, 2010).

Historically, the formalist-substantivist debate has dominated discussions on premodern markets. Formalists, following classical/neoclassical traditions, seek a unified theory of rational economic behavior, positing an innate human tendency for market exchange. Substantivists, notably Polanyi (1957), argue that a “market mentality” is a product of modern capitalism, viewing non-Western economies as embedded in deeper social, political, and religious institutions. Polanyi’s skepticism about competitive market exchange in premodern economies rested on three arguments: (1) the absence of factor markets for land and labor, (2) inherent social antagonisms in market bargaining, and (3) technical inefficiency of primitive communications hindering price information flow (Garraty, 2010; Isaac, 2022). Feinman and Garraty (2010) critically assess Polanyi’s influence, arguing that his narrow definition of market exchange and the “false metric” of comparing ancient economies to an idealized, self-regulating modern Western market have “underplayed the importance of markets in history.” As a recent review highlights, the critiques of Polanyi’s work underscore that his framework “circumvents the role of diachronic processes” and that new evidence reveals “new pathways to comprehend the sources of variation” in market history (Blanton and Feinman, 2024).

To move beyond this impasse, we draw upon additional theoretical frameworks. Economic Anthropology, New Economic Sociology (NES), and New Institutional Economics (NIE) offer alternative paradigms that emphasize the role of social networks, trust, and institutions in shaping economic behavior (Granovetter, 1985; North, 1990; Busse, 2022; Stanley, 2025). These perspectives challenge the notion of markets as purely rational or disembedded spheres and instead highlight how economic transactions are shaped by obligations, norms, and political authority. Mosse (2013) emphasizes that institutions themselves are not static structures but the outcome of negotiated practices, shaped by cultural logics, actor networks, and moral reasoning. His work underscores how development interventions—and by extension economic processes—operate through complex assemblages rather than through formal models alone. The concept of “calculative agency” (Callon, 1998), while rooted in formalist reasoning, is shown to be culturally bounded and morally constrained in many contexts (Garraty, 2010). In premodern economies, information flows were often slow-moving and highly localized, responding only to major shifts in supply and demand due to limited communication infrastructure (Garraty, 2010; Earle, 2017).

Economic anthropology has increasingly engaged with contemporary capitalist systems using tools from sociology and social philosophy to reframe the economy as a culturally and morally constituted domain (Lindh de Montoya, 2000; Plattner, 1989). Within this framework, the concept of the “moral economy” has gained renewed traction. The concept of the moral economy challenges assumptions that economic behavior is primarily driven by rational calculation or market incentives. Rather than existing outside or before the market, moral economies are co-constitutive of economic life. They shape what kinds of transactions are acceptable, who is permitted to trade with whom, and what values—monetary or otherwise—are assigned to goods and services. In this context, norms refer to culturally embedded expectations about fairness, reciprocity, and appropriate conduct, while institutions refer to the formal (codified) or informal (customary) rules that structure and enforce economic behavior. A moral economy is therefore not just a set of shared values, it is an institutional framework designed to safeguard collective benefit. Such frameworks may be upheld through state authority or through “paragovernance” mechanisms—non-state systems of rule enforcement and dispute resolution (Blanton, 2013).

Importantly, recent theorists such as Carrier (2017) and Muriel (2022) reject the earlier tendency to treat moral economies as nostalgic or premodern remnants. Instead, they emphasize the political and performative nature of moral claims in economic contexts. Moral economies are not static ethical orders but dynamic arenas where values are contested, enforced, or strategically deployed (Graeber, 2001). This perspective underscores how actors may invoke moral reasoning to justify or resist particular forms of economic change, making moral economy a powerful lens for analyzing how social order is maintained or challenged through economic activity. Economic life is not merely transactional, but also profoundly shaped by systems of meaning, belief, and social reproduction. Coleman (2022), for example, highlights how religion, ritual, and rationality intersect in economic practice, revealing that decisions around exchange often draw on cosmological and moral logics. Similarly, Colloredo-Mansfeld and Delgaty (2022) suggest that consumption itself is a socially meaningful act, one that reinforces group identity, moral obligation, and symbolic hierarchies. Consumption can also serve as a marker of exclusion, hierarchy, or antagonism. Political symbols (e.g., partisan clothing), and sumptuary laws restricting access to certain goods, illustrate how consumption may enforce boundaries as much as it fosters solidarity. These insights show that moral economies are not peripheral to economic systems, they are constitutive of how value is created, interpreted, and distributed.

Institutional economics further highlights the role of formal and informal institutions in shaping economic outcomes (North, 1990). “Formal institutions” refer to codified and enforceable rules established by an authority, such as a state. These can include property rights, contract law, trade and monetary regulation, and infrastructural investment. “Informal institutions” include norms governing reciprocity, fairness, and social obligation that are not legally codified, yet they function as durable, institutionalized expectations that shape behavior and structure relationships. In this way, the moral economy intersects productively with institutional economics and economic anthropology, offering a conceptual bridge between embedded social practice and broader economic organization.

Newman (1983) provides a comparative study of how legal systems regulate economic life in preindustrial societies, underscoring the diversity of “rules of the game.” The very concept of “property,” as Sneath (2022) argues, is not a universal given but a socially constructed relationship that varies across time and place. Political economy brings attention to the interplay of power and economy, particularly the ways in which states mediate, facilitate, or suppress market activity (Hirth, 1996; Laiou, 2002a). Blanton and Fargher (2010) explore how premodern political leaders influenced market development through administrative and ideological means. Robotham (2022) emphasizes the centrality of production and surplus extraction in political economy, situating exchange and distribution within broader relations of power. Production itself, as Prentice (2022) notes, involves not just making things but also creating people and social relations through labor.

Finally, development economics offers macro-level tools to analyze long-term patterns in economic growth and institutional evolution. It provides comparative insights into how economies functioned, focusing on developmental variation rather than essential differences (Laiou, 2002b; de Pleijt and van Zanden, 2024). Together, these theoretical approaches provide a robust framework for analyzing marketplace exchange in historical and cross-cultural perspective, bridging traditional divides and capturing the complexity of economic life.

3 Methodological approaches and interdisciplinary integration

Understanding premodern marketplace exchange necessitates a robust methodological toolkit capable of addressing the inherent challenges of archaeological data. As Smit (2022) emphasizes, archaeologists have developed various frameworks to interpret the role of markets in the material record, moving beyond simple binary evaluations of presence or absence. Among these, configurational approaches focus on identifying direct physical evidence of market spaces through the classification of architecture and layout within archaeological sites, often informed by ethnohistoric analogs. This may include large open plazas, stone alignments suggesting stalls, or chemical residues indicating intensive food preparation or craft activity (Stark and Garraty, 2010; Smit, 2022). However, these public spaces often served multiple functions, complicating interpretations, and preservation issues mean that such physical traces can be ephemeral (Feinman and Garraty, 2010).

Distributional approaches, on the other hand, analyze artifact assemblages at points of consumption to detect patterns suggestive of market exchange. The principle here is that markets, by ensuring relatively equitable access to goods, should generate more homogeneous distributions of certain artifacts across social groups, such as pottery or lithics (Hirth, 1998; Smit, 2022). In contrast, redistributive systems are more likely to produce uneven patterns, with some groups receiving more or different items due to their social status. Extending this idea, regional production-distribution models assess how goods were produced and disseminated across a wider landscape.

Yet, many of these approaches face the persistent challenge of equifinality, which is the possibility that different economic mechanisms yield similar material outcomes (Stark and Garraty, 2010; Smit, 2022). For instance, homogeneous artifact distribution might result not from market exchange but from household-level self-sufficiency or an exceptionally efficient redistribution network. Similarly, public architectural features could signal market activity, or equally serve ceremonial or social functions. To overcome these ambiguities, archaeologists advocate for a multiscalar approach, integrating evidence across household, community, regional, and interregional levels. Combining architectural, artifactual, chemical, and textual data helps triangulate interpretations, enhancing analytical robustness (Feinman and Garraty, 2010; Hirth, 2010). For example, while chemical analysis of soil might suggest zones of high activity, only in concert with structural evidence, artifact types, and possibly written records can this be confidently linked to market transactions rather than, say, feasting or ritual.

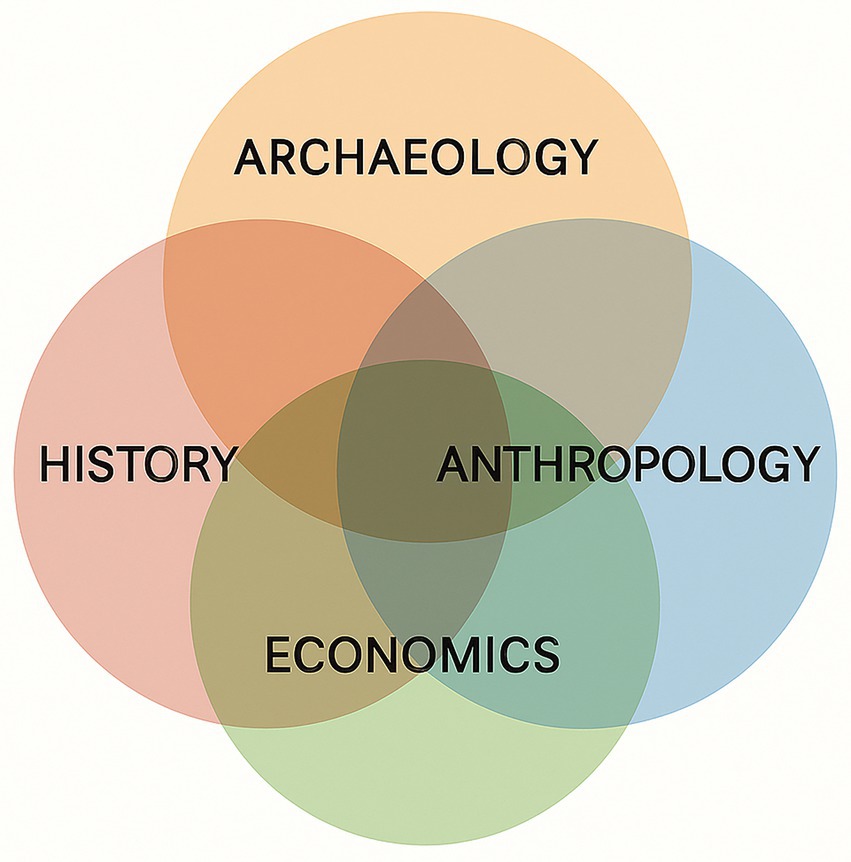

An interdisciplinary strategy is essential for advancing our understanding of ancient market systems (Figure 3). Archaeology contributes tangible data—artifacts, settlement patterns, and site organization—offering a long-term, diachronic view of economic change. History complements this with textual sources such as chronicles, administrative records, and legal documents that reveal economic practices, institutional arrangements, and political intentions. In contexts like Byzantium, written accounts clarify the operations of monetary systems, trade regulation, and state involvement in commerce.

Anthropology brings valuable theoretical models, including substantivism, cultural economics, and new economic sociology, which contextualize economic behaviors within social and symbolic structures. Ethnographic studies of traditional markets provide analogies for interpreting ephemeral archaeological evidence, including transaction rituals, bargaining strategies, and the role of social ties in economic exchanges. Gudeman (2022) underscores that local economies often rest on a socially embedded base of shared material interests distinct from formal market behavior.

Economics contributes models of market operation—supply and demand, transaction costs, network efficiency—and tools for evaluating the effectiveness of institutions and the structure of exchange systems. These theoretical lenses support comparative assessments of how different societies organized production, facilitated distribution, and integrated markets within broader political and ecological frameworks. By synthesizing data and insights from these disciplines, scholars can move beyond the limitations of single-method approaches. Cross-referencing and triangulating evidence mitigate the risks of equifinality and enrich our understanding of the diversity, complexity, and resilience of premodern economic systems.

4 Case studies

4.1 The Byzantine Empire (500–1500 CE)

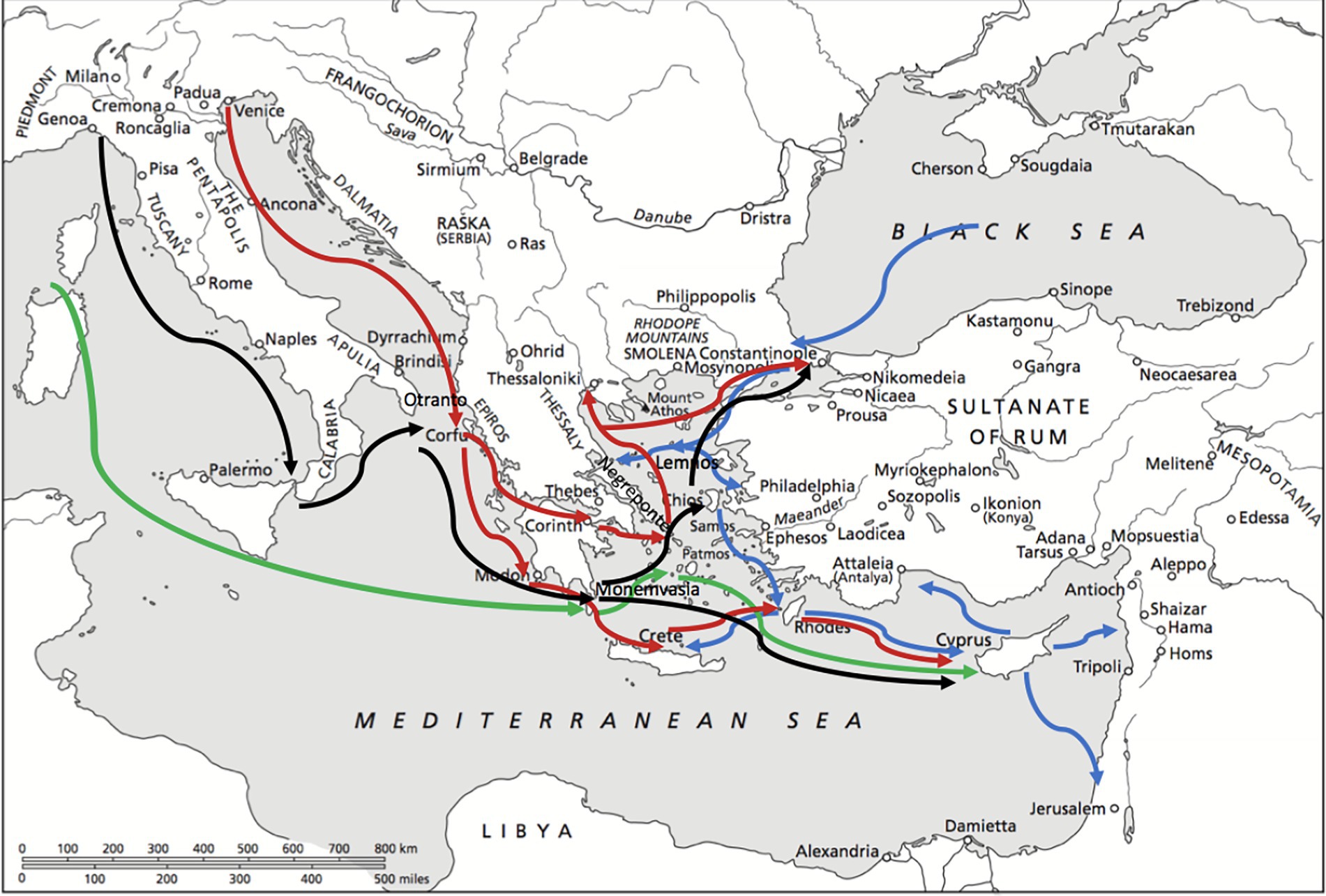

The Byzantine Empire offers compelling evidence for the existence and operation of complex market systems. Scholars such as Lopez (1951, 1959), Oikonomides (1986, 1996), Laiou (1995), Jacoby (2013, 2015), and Morrisson (2012a, 2016) have highlighted the empire’s developed monetary infrastructure, comprising gold, silver, and copper coinage (Figure 4). This enabled diverse forms of exchange and supported extensive trade networks (Figure 5), making it easier to assign value to goods and services and to engage in transactions structured around supply and demand dynamics. Importantly, money played roles that extended beyond state administration, indicating its essential function in private economic life (Lopez, 1951, 1959; Oikonomides, 1986; Ragkou, 2020; Rosenswig, 2024a, 2024b).

Figure 5. The major sea routes in the Eastern Mediterranean. In blue the sea routes connecting the Black Sea, the Aegean and the Holy Lands; in green the main pilgrim route from the West; in red the main routes followed by the Venetians; in black the main routes followed by the Genoese (Ragkou, 2020).

Byzantine economic historiography has often been shaped by the formalist–substantivist divide. One scholarly perspective underscores the relevance of markets and monetization, arguing that the Byzantine economy can be studied using macroeconomic frameworks appropriate for its developmental stage. This view emphasizes urban–rural reciprocity and sectors of production that met urban demand (Laiou, 2002c; Morrisson, 2002; Morrisson, 2012a; Morrisson, 2012b; Oikonomides, 2002; Carrié, 2012; Jacoby, 2015). A contrasting interpretation views non-market factors—such as state control and social structures—as dominant in resource distribution. Proponents of this view characterize cities as consumption centers and argue that money primarily served state purposes (Grierson, 1959; Patlagean, 1977, 1993; Hendy, 1985, 1988). Recent scholarship, however, increasingly acknowledges that market and non-market exchanges coexisted and interacted in context-dependent ways (Harvey, 1990; Laiou, 2002c; Durak, 2022).

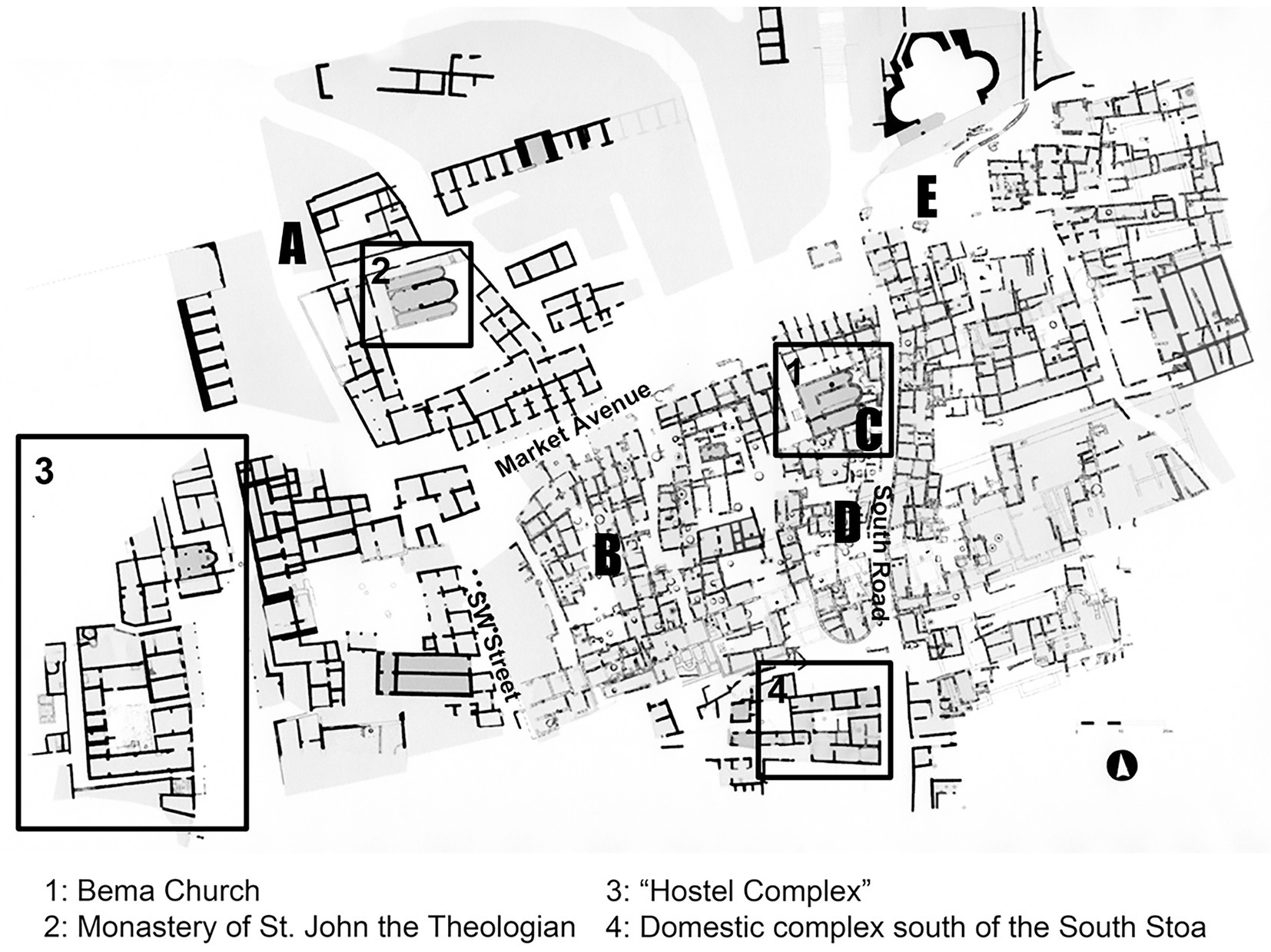

Archaeological investigations have substantially deepened our understanding of Byzantine market activity. Urban excavations in cities like Thessaloniki and Corinth have uncovered agora market spaces, commercial buildings, hoards of coins, and standardized weights—all indicative of structured market transactions (Figure 6) (Scranton, 1957; Sanders, 2002; Bakirtzis, 2003; Morrisson, 2012b; Laiou, 2017; Ragkou, 2020). The Roman Forum area of Corinth, for example, contained workshops producing pottery, glass, and metal goods, functioning as a hub of both production and trade (Sanders, 2002; Ragkou, 2018, 2020). Landscape surveys synthesize evidence of periodic fairs and seasonal trade events in rural areas, as indicated by patterns of settlement clustering and refuse deposits (Ragkou, 2018). Moreover, infrastructural elements such as road networks, harbor installations, and waystations—like those recorded in the Tabula Peutingeriana—highlight the logistical underpinnings of market connectivity across local and imperial scales (Sanders and Whitbread, 1990; Ragkou, 2020).

Figure 6. Urban market infrastructure in Byzantine Corinth. The map highlights key economic and religious features of the lower city, including major churches and associated workshop areas (e.g., metallurgy, wine presses, olive presses). Kiln locations noted: (A) St. John’s Kiln, (B) Agora SC Kiln, (C) Agora SC Kiln, (D) South Stoa Kiln, (E) Agora NE Kiln. This spatial arrangement underscores the integration of craft production and commerce around sacred spaces in Byzantine urban life (Ragkou, 2020).

The work of Athanasios Vionis has been particularly influential in illuminating the economic life of the Byzantine provinces. Drawing on ceramic analysis and settlement studies conducted across Boeotia, the Cyclades, Cyprus, and Sagalassos in Asia Minor, Vionis (2010, 2012, 2017, 2018) and Papantoniou and Vionis (2017) demonstrates that economic activity was not confined to Constantinople but extended robustly into the rural hinterlands. His use of landscape archaeology, especially in Boeotia and Cyprus, integrates GIS and intensive survey methods to map networks of villages, market towns, and sacred centers. This body of work dismantles the traditional urban/rural dichotomy, revealing the central role of rural landscapes in facilitating regional economic integration.

Complementing this, Beate Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ine Jacobs have provided crucial insights from both rural and urban perspectives in Asia Minor. Böhlendorf-Arslan’s (2019, 2020, 2021) analyses of settlements like Boğazköy/Ḫattuša and Assos trace how rural production was embedded in broader trade systems, with ceramics and imported goods serving as evidence of interconnected economies. Her work on the Southern Troad and Black Sea regions expands our view of peripheral participation in imperial commerce. Meanwhile, Jacobs (2012, 2013a, 2013b) has explored cities such as Sagalassos and Aphrodisias, illustrating how shifts in urban vitality, civic architecture, and religious functions influenced market space organization.

Legal and textual evidence reveals the institutional foundations underpinning Byzantine markets. Maniatis (2003, 2016) demonstrates that, while the state maintained a monopoly over coinage and established key legal norms, commodity prices were generally shaped by market forces, with limited direct intervention. Legal frameworks allowed for considerable contractual flexibility and even encouraged strategic negotiation, provided the principle of the “just price” was upheld. The just price refers to the state’s regulatory focus on preventing exploitation and ensuring fairness in commercial transactions, rather than imposing rigid price controls. Market principles—such as supply, demand, and scarcity—were well understood, and excessive regulation was typically avoided to prevent shortages or the emergence of underground markets.

The institutional environment broadly supported private property, voluntary exchange, and entrepreneurial initiative (Maniatis, 2016). Property rights were legally protected, enabling owners to sell, lease, or bequeath assets at their discretion (Leidholm, 2023). The state’s primary economic functions centered on maintaining order, upholding contracts, and investing in infrastructure, rather than directing production or controlling prices (Laiou and Morrisson, 2007). The role of guilds has often been misunderstood: Maniatis (2003, 2016) clarifies that they were not universally present nor did they exercise monopoly pricing power. Instead, guilds operated mainly in the capital and promoted intra-guild competition, for example through the “one-man one-trade” policy (Maniatis, 2003), which meant that a person could not participate in more than one guild. The just price doctrine, explained above, was applied narrowly—primarily to non-commercial immovable assets—while most commercial transactions remained governed by negotiation and prevailing market conditions. Efforts to cap interest rates frequently failed to align with economic realities, occasionally resulting in capital shortages or legal circumvention. Thus, the Byzantine institutional framework facilitated a dynamic market environment in which private initiative and contractual freedom prevailed, with the state acting primarily as a guarantor of order and fairness rather than as a central planner.

Distributional evidence supports the prevalence of market activity. The widespread use of coinage across social groups and territories indicates deep market penetration (Stark and Garraty, 2010). Surviving weights and balances, often artistically crafted, suggest the normalization of commercial measurement tools. Geography further reinforced Byzantium’s economic vitality; situated at the nexus of Europe, Asia, and Africa, it controlled key trade corridors. Archaeological studies (Mango, 2009; Ragkou, 2020; Vasilescu, 2022) detail intricate trade networks, including a prominent north–south axis linking the Mediterranean with Northern Europe. These findings illustrate that political institutions and market mechanisms could evolve cooperatively, as noted by Garraty (2010).

Finally, urban provisioning highlights the economic interdependence between cities and their rural surroundings. The collective volume Feeding the Byzantine City, edited by Vroom (2020), brings together archaeological case studies that document the supply systems of Byzantine urban centers from ca. 500–1500 CE. Drawing on ceramic, botanical, and zooarchaeological data, contributors demonstrate how urban demand shaped rural production, trade routes, and storage infrastructure across regions such as the Balkans and the Black Sea region, Greece, and Asia Minor (Vroom, 2020). These findings underscore the role of cities not only as consumption hubs but also as drivers of integrated regional economies. Rather than being isolated or passive, urban centers actively influenced patterns of production, distribution, and market behavior.

4.2 The prehispanic central Andes (1000 BCE–1532 CE)

The study of prehispanic central Andean economies has historically been characterized by an “anti-market mentality” (Cook, 1966), largely influenced by substantivist scholars like Murra (1995) who downplayed the role of markets. This perspective emphasized non-market factors such as redistribution and reciprocity as dominant forms of exchange, deeply embedded in social, institutional, political, ideological, and religious factors. Feinman and Garraty (2010) specifically note that the “Inca economy, with greater evidence for state storage and labor tribute, has been presented as a nonmarket contrast to that of the Aztec,” but caution that “the possibility and the extent of marketplace exchange in the Andean world has been too readily discounted and remains to be deciphered” (see also LeVine, 1992). Stanish (2010) further argues that the Inca’s (1400–1532 CE) reliance on a corvée labor-tax system (mit’a) rather than price-fixing markets led to higher “transaction costs” for urban provisioning, thereby limiting the size of their urban centers compared to market-based economies.

Prehispanic Andean economies were largely governed by socially embedded commodity exchanges, reciprocity, and corvée labor, although other forms of exchange were also practiced. Exchange was a social act, not merely an economic transaction (Sanchez, 2022). However, recent scholarship suggests that markets may have played a more significant role than previously thought, albeit based on barter or direct exchange rather than currency (Stanish and Coben, 2013). Regarding the Incas, data from household excavations in Peru’s upper Mantaro valley suggest that marketing was a strong possibility (D’Altroy and Earle, 1985; D’Altroy, 2002; Hutson, 2021). The absence of a formal currency meant that commodities and services were exchanged directly. Without a standardized medium of exchange, establishing consistent pricing could have been challenging. By “consistent pricing,” we mean regionally recognized rates of exchange that were intelligible within particular periods, markets, and/or social contexts rather than invariable state- or empire-wide prices. Nevertheless, relatively consistent equivalencies could exist in the form of commodity currencies. Examples of this can be seen in the economies of the Classic Maya (250–900 CE; Baron, 2018) and the Aztecs (1325–1521 CE; Berdan, 2023) in Mesoamerica. In the prehispanic Andes, coca (Mayer, 2002) and metal “axe-money” (Montalvo-Puente et al., 2023), for instance, have been proposed as commodity currencies. Recent scholarship also highlights the existence of weight and measurement systems involving balance scales for goods such as metals, cotton, and coca in the coastal regions of the Inca Empire (Dalton, 2024; Covey and Dalton, 2025). This paper’s spectrum-based approach aims to cover these various aspects of exchange and monetization.

The unique Andean geography, characterized by diverse ecological zones according to different altitudes, profoundly influenced economic and agricultural opportunities and constraints (Pulgar Vidal, 1981; Brush, 1982; Sandweiss and Richardson III, 2008; Mader, 2019a). Murra (1972) concept of the “vertical archipelago” describes how societies structured exchange across altitudinal zones to maximize ecological complementarity. This verticality, also called “vertical control” (Murra, 1972), allowed communities to directly access products from various ecological niches, reducing the need for extensive market-based exchange, especially for staple goods. Archaeological evidence increasingly points to complex patterns of interaction, also between Andean and Amazonian societies, suggesting flows of goods, ideas, people, animals across diverse regions and microclimates (Wilkinson, 2018; Pearce et al., 2020; Clasby and Nesbitt, 2021; Politis and Tissera, 2023).

Identifying archaeological evidence for marketplaces in the Andes poses significant challenges due to their multifunctional and transitory nature, often leaving few distinct remains (Feinman and Garraty, 2010; Smit, 2022). In this context, the configurational approach—which relies on identifying physical markers such as plazas—is often inconclusive, while the distributional approach—assessing artifact frequency and diversity across households—is complicated by confounding factors, since similar goods may be acquired for social or cultural reasons unrelated to market participation (Stark and Garraty, 2010; Smit, 2022). A common archaeological approach is to begin by examining households and their supply (Hirth, 1998; Burger, 2013; Narotzky, 2022), which aligns with the “regional production-distribution approach” (Stark and Garraty, 2010) for evaluating market dissemination. Hirth (2010) emphasizes the household as the fundamental unit of analysis for understanding market origins and organization, as households actively engage in diverse production and exchange activities to supply themselves. The debate on Andean markets often boils down to definitions and the available archaeological data, with different understandings of whether or not institutionalized market structures existed.

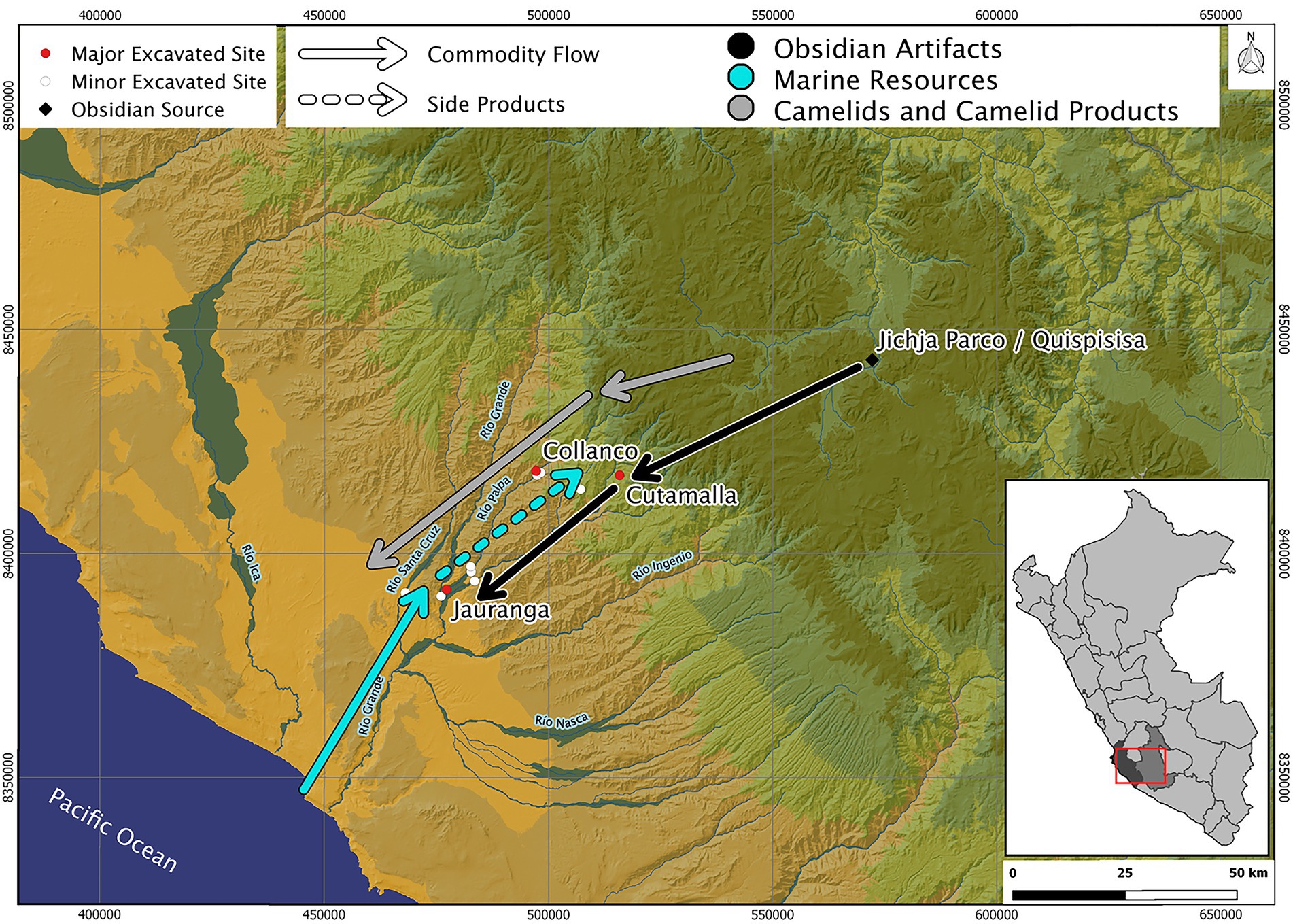

Recently, the model of “economic directness” was introduced to overcome the market/non-market dichotomy in the Andean context, reshaping our understanding of prehispanic exchange (Mader et al., 2023a). Economic directness originated from archaeoeconomic research on the Paracas culture (800–200 BCE) in southern Peru (Mader, 2019a, 2019b). This model, based on archaeological evidence from large-scale surveys and excavations in the Palpa valleys in the western Andes, including settlement patterns and the distribution of obsidian artifacts, malacological material, and camelid remains, reveals a system of direct access to resources and direct exchange across diverse ecological tiers (Figure 7). The model emphasizes decentralized, direct resource procurement and redistribution through regional centers and socially embedded exchange mechanisms. Economic directness is characterized by down-the-line exchange networks, reduced transaction costs, llama caravan transport, unbalanced commodity flows, and basic forces of supply and demand—with a major locus of consumption on the Pacific coast and procurement and production in the highlands. Down-the-line trade and llama caravans can include several stages of direct exchange. Nevertheless, these transactions incur lower costs than the use of standardized forms of currency. A dense, continuous settlement pattern stretching from coastal regions to the highland puna, developed in response to demographic growth (Soßna, 2015). The economic directness model shows how the dense and continuous settlement along the western Andean slopes allowed Paracas communities direct access to diverse resources such as marine products, camelids, lithic materials, and agricultural goods. This configuration reduced transaction costs, as most daily necessities could be obtained within the same socioeconomic system.

Figure 7. Distribution and flows of key resources during the Paracas period (800–200 BCE) in the Palpa valleys of southern Peru (Mader, 2019a; Mader et al., 2023a).

Archaeological evidence further reveals asymmetrical commodity flows across the Andes: highland resources such as obsidian and camelid products appear in large quantities on the coast, while coastal goods like sea shells are far less common in highland contexts (Mader, 2019a; Mader, 2019b; Mader et al., 2018, 2022, 2023a). The highlands were not simply extraction zones, they also hosted strategic, regional centers for the coordination of production and distribution of raw materials and finished goods. In terms of consumption, coastal commodities did not play a significant role in the highlands. Coastal settlements emerged as primary hubs of consumption of all kinds of goods and social power, as indicated by higher proportions of fine-ware ceramics and more elaborate mortuary contexts—markers associated with elite status. This trade pattern reflects market-like exchange in terms of economic transfers that moved goods across ecological zones, although there is no straightforward evidence of physical marketplaces.

The features of economic directness became especially pronounced during the Late Paracas phase (370–200 BCE), amid significant demographic growth, climatic fluctuations, and growing social complexity in the region (Mächtle and Eitel, 2013; Fehren-Schmitz et al., 2014; Schittek et al., 2015; Soßna, 2015). Developed through an archaeoeconomic lens, this model draws on abundant material evidence related to everyday life to trace patterns of production, exchange, consumption, and inequality (Feinman, 2008). Economic directness diverges from traditional Andean models, such as verticality (Murra, 1972), circuit mobility (Núñez and Dillehay, 1995), and transhumance (Lynch, 2022), though it shares components with them, such as vertical resource exploitation and caravan transport.

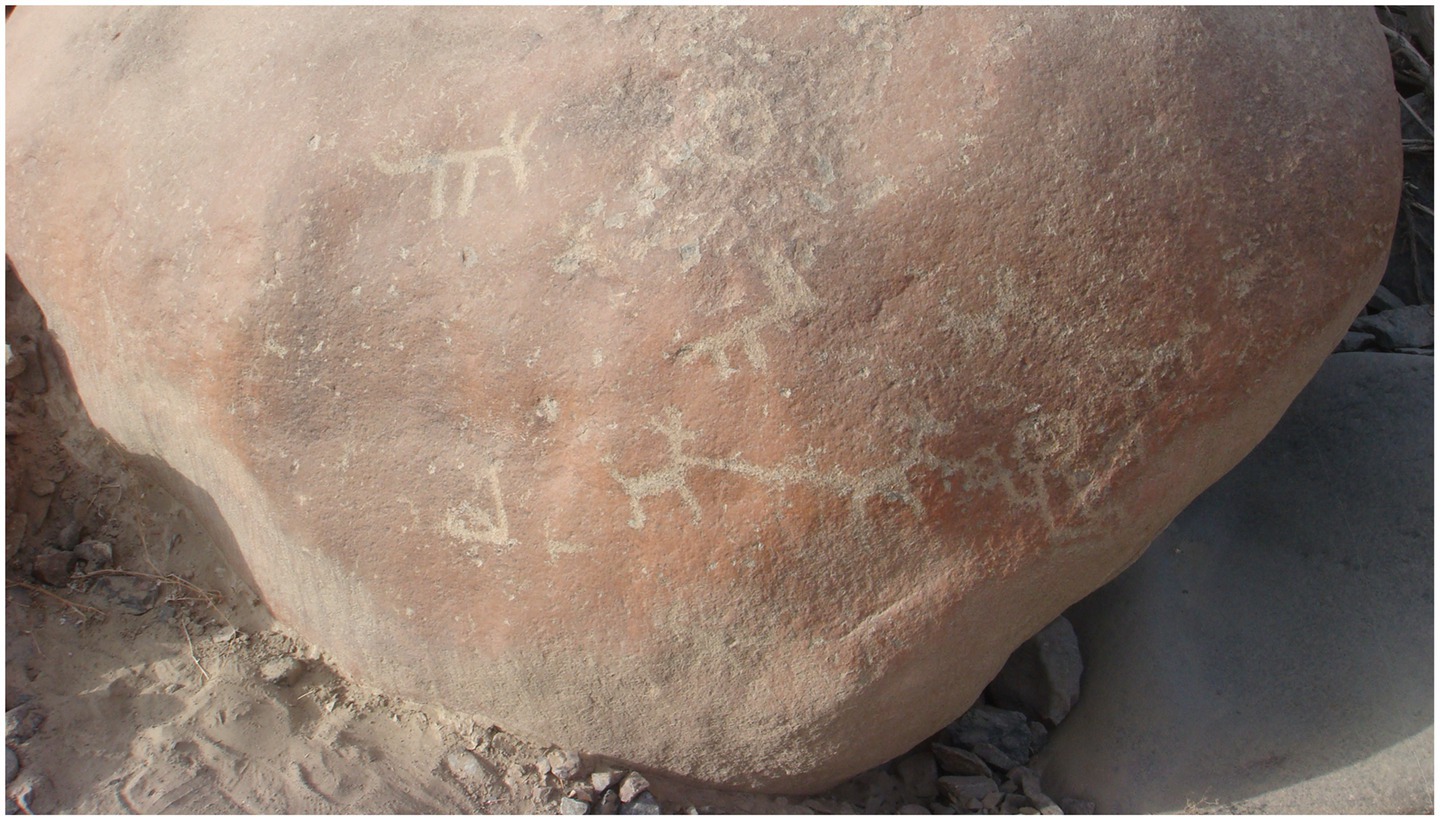

Archaeological findings across the Andes show that complex exchange systems could arise in the absence of formal market institutions or centralized political control. Strategic junction sites or nodes such as Chavín de Huántar (1000–500 BCE) show material flows of prestige goods, ceramics, lithics, and foodstuffs, which speak to both long-distance and regional interaction networks (Figure 8; Browman, 1981; Burger, 2008; Matsumoto et al., 2018; Nielsen et al., 2019; Burger and Nesbitt, 2023; Mader et al., 2023b). These networks were often structured around reciprocity, seasonal fairs, and ceremonial events, in which exchange was mediated by social ties rather than formal market institutions. However, basic supply and demand forces also shaped these Andean economies, as reflected in the spatial pattern of the Paracas, for instance: coastal settlements had a high consumption of goods, while highland regions focused on procurement and production, as explained in more detail above (Mader, 2019a; Mader et al., 2023a). The use of llama (Lama glama) caravans facilitated interregional transport and exchange, enabling non-monetary economies to achieve broad territorial integration (Figure 9; Berenguer, 2004; Mader et al., 2018, 2022; Alaica et al., 2022; Siveroni, 2022). Overall, the Andean case demonstrates that sophisticated economic behavior—including specialization, trade, and surplus distribution—can emerge through varied institutional forms. Concepts like economic directness enrich this view, providing a model that bridges environmental adaptation, demographic trends, and cultural and socioeconomic practices. Such findings challenge linear narratives of economic development and invite a broader theorization of what constitutes a market in ancient contexts.

Figure 8. Sea shells were key mediums of exchange in the prehispanic Andes. This assemblage of two necklaces, one bracelet, and additional beads was excavated at the Paracas site of Jauranga in southern Peru (Photographs taken by Manuel Gorriti; Mader, 2019a).

Figure 9. Petroglyph of a llama caravan at the prehispanic site of Quebrada de la Viuda in the Palpa valley. Quebrada de la Viuda was a strategic junction site connected to a vertical trade route (Mader et al., 2022).

5 Comparative analysis

Comparing the Byzantine Empire with the prehispanic central Andes reveals both striking contrasts and intriguing parallels in marketplace exchange (Table 1). This comparison underscores the value of adopting multiscalar, cross-disciplinary approaches to understand economic systems in diverse historical contexts (Feinman and Garraty, 2010; Earle, 2017).

One of the most fundamental differences lies in the medium of exchange. Byzantium operated with a sophisticated monetary system involving gold, silver, and copper coins, which facilitated complex transactions, enabled greater specialization, and simplified valuation. This infrastructure supported a more flexible and responsive market, integrating local and international exchanges. In contrast, the Andean world relied primarily on direct exchange, which restricted price-setting mechanisms and necessitated more direct, socially embedded exchanges. This divergence shaped not only the operational logic of each economy but also the institutional tools they employed for economic integration. Yet, while the presence of money accelerated commercial sophistication in Byzantium, the Andean case challenges assumptions that complex markets require a formal currency, showing that systems of value, obligation, and reciprocity can sustain substantial exchange. In terms of market sophistication, Byzantine markets were dynamic, legally institutionalized, and capable of responding to supply and demand shifts. They were embedded within a broader macroeconomic system that featured property rights, legal contracts, and infrastructural support. In contrast, while some Andean exchanges mirrored market functions, they remained rooted in ceremonial cycles and social relationships and obligations rather than formal legal structures. Periodic fairs tied to ritual calendars exemplify how markets often coincided with ceremonial gatherings, reinforcing their embeddedness in broader social life. Both cases show that markets can emerge from legal frameworks and from deeply rooted social practices, with varying degrees of formalization.

Trade networks also reflect significant contrasts. The Byzantine Empire, strategically located at the intersection of Europe, Asia, and Africa, maintained vast trade networks enhanced by monetary circulation and infrastructure such as roads and ports. Goods like pottery, glass, and metals moved over long distances, integrating the empire economically and culturally (Mango, 2009; Ragkou, 2020). The widespread circulation of coinage, standardized weights and balances, urban marketplaces, and written legal frameworks regulating exchange provide direct archaeological and textual evidence (Laiou, 2002c; Maniatis, 2003, 2016; Morrisson, 2012b) that Byzantine exchange was more commercialized than what is currently documented in the Andes.

In the Andes, trade networks functioned despite the dramatic altitudinal differences and the lack of a common currency. Yet these very geographical features prompted the development of vertical mobility and complementarity, a pattern whereby communities accessed resources from different ecological zones through colonization, reciprocity, tribute, or direct procurement and exchange rather than formal markets (Murra, 1972; Mader, 2019a; Mader et al., 2023a; Beresford-Jones et al., 2023). Although long-distance exchanges did occur—such as the movement of obsidian, marine shells, or metal goods—these were often facilitated through llama caravans, regional centers, and periodic fairs rather than sustained commercial integration. Thus, while Byzantium benefited from horizontal commercial flows across distances, Andean systems also created vertical links that were equally vital for economic coherence, albeit through different (institutional) pathways.

State involvement in economic life also varied. The Byzantine state took an active role in shaping the economy through taxation, legal regulation, and the construction of infrastructure, yet generally avoided micromanaging prices or suppressing private enterprise. Rather than suppressing markets, political elites often facilitated commerce and profited from its expansion (Feinman and Garraty, 2010). In contrast, Andean state structures—particularly under the Inca—relied heavily on labor taxation and centralized redistribution, deliberately sidestepping market mechanisms. As Stanish (2010) notes, Inca rulers avoided encouraging widespread market participation, favoring bureaucratic control over exchange. The Byzantine example suggests a co-evolution of political and market institutions, whereas the Andean case illustrates the possibility of economic complexity emerging through deliberate state suppression of market logic.

However, both systems reveal the importance of nongovernmental forms of regulation. In Byzantium, guilds, social norms, and legal traditions helped enforce standards and reduce market risk. Similarly, in the prehispanic Andes, local community norms and ceremonial cycles provided a framework for regulating exchange. Periodic rural fairs, linked to ritual calendars, offered trusted venues where people from different regions could engage in exchange, protected by mutual obligations and long-standing relationships (Hartmann, 1971). Such bottom-up mechanisms are echoed in comparative cases like the Hohokam, where shared rituals and social trust enabled market-like exchanges in the absence of centralized political oversight (Abbott, 2010; Garraty, 2010). Theories of moral economy, as advanced by Carrier (2022) and Muriel (2022), help explain how economic behavior was structured around shared values and social expectations in both contexts. These insights challenge the notion that only formal institutions can stabilize exchange, highlighting how moral norms and trust networks can ensure economic order across very different material and political settings.

We acknowledge that our comparison largely juxtaposes an empire (Byzantium) with the multi-polity landscapes of the prehispanic central Andes. Some of the observed differences in economic practice reflect this sociopolitical disparity. In both cases, however, fairs and ritual gatherings likely provided the temporal and social frameworks for structuring exchange. In Byzantium, seasonal and religious festivals may have coincided with periodic markets, integrating regional economies. Similarly, in the Andes, ritual calendars and fairs may have synchronized long-distance interactions, established inter-polity conventions, and mitigated the risks of transporting goods via llama caravans across mountainous terrain (Blanton, 2013).

Finally, the archaeological identifiability of marketplaces varies between these regions. In Byzantium, the widespread presence of coins, standardized weights, urban agoras, and commercial facilities allows for more direct identification of market activities through configurational and distributional approaches (Mango, 2009; Morrisson, 2012a). In the Andes, evidence is more inferential. We also recognize that some contrasts reflect differences in the robustness of the evidence, such as textual versus archaeological evidence and the amount of data, rather than differences in practice. This asymmetry underscores the value of diverse archaeological methods for reconstructing exchange. For example, the absence of direct written sources or monetary artifacts requires archaeologists to rely on household-level data, the spatial distribution of artifacts, and regional production and consumption patterns to reconstruct exchange networks (Stark and Garraty, 2010; Hutson, 2021). Hirth (2010) emphasizes the need to assess variability in market structures rather than simply proving their existence. Provenance analyses, isotopic studies, and spatial modeling increasingly allow scholars to trace exchange pathways and identify patterns of interaction across ecological zones. These methodological differences underscore the challenge of applying uniform criteria across culturally and materially diverse societies, reminding us that the visibility of markets is not solely a matter of their intensity but also of how we choose to detect them.

Taken together, the comparative study of Byzantine and Andean economies reveals that while the presence or absence of monetary systems and formal institutions shaped how markets functioned, both regions demonstrate that exchange systems can be socially embedded, politically inflected, and materially visible in distinct yet revealing ways. The contrast between monetized, legally codified markets and socially-embedded, ritualized exchange challenges any singular model of economic development, encouraging instead a pluralist approach that takes seriously the diverse pathways through which societies organize trade and value.

6 Discussion

Our comparative analysis reveals that marketplace exchange in premodern history was persistent but highly diverse in its manifestations and underlying mechanisms. The Byzantine Empire exemplifies a complex, monetized economy with sophisticated markets, while the prehispanic Andes demonstrate that significant trade could occur through direct exchange, deeply embedded in social and cultural practices, without a formal currency. Ethnographic evidence from north-east Nepal, for instance, also suggests that price-making mechanisms, if understood as standards of equivalency, are possible in the absence of a currency (Humphrey, 1985). Therefore in both direct and currency-based exchange, prices can be determined by numerous negotiations between participants, supply and demand forces, and the desire to achieve a satisfactory return on goods (Fauvelle, 2025).

This study contributes to broader discussions on the nature of trade, commerce, and economic systems in premodern economies in several key ways. One central contribution is the bridging of theoretical divides. By examining both formalist and substantivist arguments through concrete case studies, we show that neither framework fully captures the intricacy of historical exchange. A more productive approach is interdisciplinary, accounting for institutional, political, cultural, and geographical variables. Markets, as Feinman and Garraty (2010) and Hirth (2010) emphasize, are always embedded in wider social systems. The distinction lies in degrees of formality and integration, not in absolute categories. Economic anthropology, as argued by Carrier (2022), offers a holistic framework for navigating these complexities.

Another insight lies in the role of money and transaction costs in shaping economic systems (Fauvelle, 2025). The presence of money in Byzantium enabled market expansion, economic specialization, and broader integration, while its absence in the Andes constrained exchange to more immediate, socially embedded relationships. Stanish (2010) argues that the lack of market pricing in the Inca Empire contributed to higher transaction costs in urban provisioning and potentially limited city growth compared to market-oriented societies, such as the Aztecs. However, it is important to note that our analysis does not generalize from the Incas to the prehispanic Andes more broadly. The Inca Empire was rather unique in that it was an extremely extractive, expansionist, and war-centered economy. Concepts such as “moneystuff” and the distinction between special-purpose and general-purpose money (Isaac, 2022) are helpful in explaining how different monetary forms influence the unification or fragmentation of economic space.

While we emphasize throughout that market-like behavior does not necessitate formal institutions, it is important to recognize that markets themselves may nonetheless function as institutions—albeit often in informal ways and not organized by central authorities. Especially in the absence of legal codification or state enforcement, the stability of exchange can emerge through informal mechanisms such as shared norms, repeated practices, and socially embedded expectations. In this sense, many of the mechanisms observed in the Andean context—such as seasonal fairs and direct exchange—can be understood as constituting informal institutional frameworks. Similarly, in certain rural or peripheral Byzantine settings where formal market infrastructure was less prominent, informal arrangements may have structured exchange in consistent, predictable ways. This perspective reinforces our broader argument that economic organization in premodern societies operated along a spectrum and that market phenomena need not be confined to narrowly defined institutional categories.

This analysis also rethinks the relationship between markets and states. The Byzantine example illustrates how states can actively support market infrastructure without resorting to overregulation. In contrast, market activity in other contexts—such as among the Hohokam (Abbott, 2010)—emerged from the bottom up, with traders and communities structuring exchange through trust and shared norms rather than state coercion. Blanton and Fargher’s (2010) findings suggest that collective action in governance correlates with the presence of market systems. It challenges older views of a fundamental antagonism between political authority and market expansion (Garraty, 2010; Robotham, 2022), and suggests a more dynamic spectrum of interaction.

A further contribution of this study is its emphasis on the methodological challenges and opportunities of identifying market systems archaeologically. The absence of standardized indicators, particularly in non-monetary economies like the Andes, complicates analysis. However, as Stark and Garraty (2010), Hirth (2010), and Smit (2022) argue, flexible methods—ranging from spatial distribution and configurational analysis to chemical and provenance studies—can reveal market structures even in the absence of coinage or formal marketplaces. Hirth’s (2010) focus on the household as the basic analytical unit is especially valuable, as household decisions about supply shape patterns of production and exchange. This insight is echoed in Narotzky’s (2022) notion of provisioning as a dynamic intersection of social and material relations.

The concept of economic directness (Mader et al., 2023a), developed through research on the Paracas culture in southern Peru, offers an important model for interpreting non-monetized economies. It foregrounds direct access to resources, down-the-line exchanges, and reduced transaction costs within decentralized systems of mobility and settlement. While developed in the context of the Andes, this model may also apply to other premodern settings, including the Byzantine provinces. In rural regions of Byzantium where formal market structures and widespread coin use were limited, communities may have engaged in economically direct practices—accessing nearby resources and exchanging goods through kinship and local norms rather than formal institutions. This suggests that economic directness and monetized market systems could coexist within a single polity, shaped by geography, demography, and institutional variability. Future research could explore how patterns of economic directness intersected with broader market integration across Byzantine territories.

Taken together, these findings suggest a potential framework for future comparative research. Rather than forcing past economies into rigid categories, scholars can use this kind of analysis to map economies along a spectrum—from highly institutionalized, monetized systems with formal market regulation to decentralized, embedded systems characterized by economic directness. This comparative typology encourages more flexible interpretations of archaeological and historical evidence and opens the door to recognizing hybrid forms of exchange. By synthesizing variables such as mobility, transaction cost, state involvement, and social embeddedness, this model can serve as a productive tool for analyzing a broad range of premodern economic systems worldwide.

Ultimately, the persistence of exchange across both regions, despite radically different institutional, political, and cultural environments, reveals that market activity is a deeply human phenomenon. The economic backbones of these societies were shaped not by a single universal model, but by a dynamic interplay of contextual factors. This study invites scholars to move beyond rigid economic categories and toward a more nuanced, pluralist understanding of how human communities organize production, distribution, and value across time and space.

7 Conclusion

This study examines two contrasting preindustrial economic systems: the monetized, institutionally complex Byzantine Empire and the largely non-monetary, socially embedded economies of the prehispanic Andes. We deliberately choose these two systems to highlight how a spectrum-based approach can assess market-like behavior in different sociopolitical settings. Through this comparison, we demonstrate that markets are not monolithic entities, but historically contingent phenomena shaped by diverse institutional, cultural, and material conditions. Rather than imposing rigid theoretical categories, our analysis underscores the value of interdisciplinary approaches in illuminating the multifaceted nature of ancient exchange. Drawing on insights from archaeology, history, economic anthropology, and development economics, we show that both formalized and informal market practices were central to how premodern societies organized production and distribution.

The Byzantine example illustrates how state-supported monetary systems could foster market integration and specialization, while the Andean case emphasizes resilience and cohesion through ecological complementarity and reciprocal exchange. Both challenge teleological assumptions about what constitutes a “developed” market and reveal that political authority and market activity are not necessarily in opposition but can be mutually reinforcing or independently coexisting depending on context. Methodologically, this research underscores the critical need for multiscalar, context-sensitive archaeological approaches that integrate evidence from households, settlement patterns, and material flows. The “economic directness” model, derived from Andean studies, offers a valuable new lens for interpreting non-monetized economies, with potential applicability not only to the Andes but also to rural Byzantine contexts and other diverse premodern societies. This comparative framework, which positions economies along a spectrum from highly institutionalized market systems to decentralized, economically direct networks, serves as a robust model for analyzing economic diversity across world regions. Such an approach encourages more flexible interpretations of archaeological and historical evidence and opens the door to recognizing hybrid forms of exchange.

Moving forward, interdisciplinary research will continue to enrich our understanding of the past, inform contemporary policy debates, and inspire new avenues for scholarship. Future studies could deepen this comparative framework by exploring micro-level mechanisms of exchange in the Andes, mapping non-governmental regulation in both regions, and examining the long-term trajectories of market forms across diverse cultural landscapes. Leveraging new archaeological methods—such as advanced compositional analysis, GIS, and spatial modeling—will be essential for unraveling the nuanced roles of households, production networks, and social relations in shaping economic behavior. Ultimately, by recognizing the manifold ways exchange is expressed across time and space, we not only enhance our understanding of the past but also gain fresh perspectives on the possibilities for organizing economic life in the present and future.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

KR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. KR’s and CM’s research was supported by the DFG Research Training Group “Archaeology of Pre-Modern Economies,” project number: 215677325. CM’s work was also supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) within the framework of the German Excellence Strategy-Cluster of Excellence, Bonn Center for Dependency and Slavery Studies (BCDSS), EXC 2036/1-2020, project number: 390683433. This publication was financed by the Open Access Publishing Fund of the University of Marburg.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the topic editors, Gary M. Feinman and Richard E. Blanton, for inviting us to participate in this special issue. We also thank Jonas Bens for inspiring discussions on preindustrial economies.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbott, D. R. (2010). “The rise and demise of marketplace exchange among the prehistoric Hohokam of Arizona” in Archaeological approaches to market exchange in ancient societies. eds. C. P. Garraty and B. L. Stark (Boulder: University Press of Colorado), 61–83.

Alaica, A. K., González La Rosa, L. M., Muro Ynoñán, L. A., Gordon, G., and Knudson, K. J. (2022). “Camelid caravans and middle horizon Exchange networks: insights from the late Moche Jequetepeque valley of northern Peru” in Caravans in socio-cultural perspective: Past and present. eds. P. B. Clarkson and C. M. Santoro (London: Routledge), 122–144.

Bakirtzis, C. (2003). The urban continuity and size of late byzantine Thessalonike. Dumbarton Oaks Pap. 57, 35–64. doi: 10.2307/1291875

Baron, J. P. (2018). Making money in Mesoamerica: currency production and procurement in the classic Maya financial system. Econ. Anthropol. 5, 210–223. doi: 10.1002/sea2.12118

Berenguer, J. (2004). Caravanas, interacción y cambio en el desierto de Atacama. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones Sirawi.

Beresford-Jones, D. G., Mader, C., Lane, K. J., Cadwallader, L., Gräfingholt, B., Chauca, G., et al. (2023). Beyond Inca roads: archaeological mobilities from the high Andes to the Pacific in southern Peru. Antiquity 97, 194–212. doi: 10.15184/aqy.2022.168

Blanton, R. E. (2013). “Cooperation and the moral economy of the marketplace” in Merchants, markets, and exchange in the pre-Columbian world. eds. K. G. Hirth and J. Pillsbury (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection), 23–48.

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2008). Collective action in the formation of pre-modern states. New York: Springer.

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2010). “Evaluating causal factors in market development in premodern states: a comparative study, with critical comments on the history of ideas about markets” in Archaeological approaches to market exchange in ancient societies. eds. C. P. Garraty and B. L. Stark (Boulder: University Press of Colorado), 207–226.

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2016). How humans cooperate: confronting the challenge of collective action. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

Blanton, R. E., and Feinman, G. M. (2024). New views on price-making markets and the capitalist impulse: beyond Polanyi. Front. Hum. Dyn. 6:1339903. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2024.1339903

Blanton, R. E., and Feinman, G. M. (2025). Food, markets, and governance: a new lens on the emergence of collective institutions. Front. Hum. Dyn. 7:1627513. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2025.1627513

Böhlendorf-Arslan, B. (2019). Die Oberstadt von Ḫattuša: Die mittelbyzantinische Siedlung in Boğazköy. Fallstudie zum Alltagsleben in einem anatolischen Dorf zwischen dem 10. und 12. Jahrhundert. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Böhlendorf-Arslan, B. (2020). “Changes in the settlements and economy of the southern Troad” in Transformations of City and countryside in the byzantine period. eds. B. Böhlendorf-Arslan and R. Schick (Mainz: Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums), 55–66.

Böhlendorf-Arslan, B. (2021). “Transformation von Stadtbild und urbaner Lebenswelt: Assos in der Spätantike und in frühbyzantinischer Zeit” in Veränderungen von Stadtbild und urbaner Lebenswelt in spätantiker und frühbyzantinischer Zeit: Assos im Spiegel städtischer Zentren Westkleinasiens. ed. B. Böhlendorf-Arslan (Mainz: Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums), 23–90.

Browman, D. L. (1981). New light on Andean Tiwanaku: a detailed reconstruction of Tiwanaku's early commercial and religious empire illuminates the processes by which states evolve. Am. Sci. 69, 408–419.

Brush, S. B. (1982). The natural and human environment of the central Andes. Mt. Res. Dev. 2, 19–38. doi: 10.2307/3672931

Burger, R. L. (2008). “Chavín de Huántar and its sphere of influence” in The handbook of south American archaeology. eds. H. Silverman and W. H. Isbell (New York: Springer), 681–703.

Burger, R. L. (2013). “In the realm of the Incas: an archaeological reconsideration of household exchange, long-distance trade and marketplaces in the pre-Hispanic central Andes” in Merchants, markets, and exchange in the pre-Columbian world. eds. K. G. Hirth and J. Pillsbury (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection), 321–336.

Burger, R. L., and Nesbitt, J. (Eds.) (2023). Reconsidering the Chavín phenomenon in the twenty-first century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Busse, M. (2022). “Markets” in A handbook of economic anthropology. ed. J. G. Carrier. 3rd ed (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 136–147.

Callon, M. (1998). “The embeddedness of economic markets in economics” in The Laws of the markets. ed. M. Callon (Oxford: Blackwell), 1–57.

Carrié, J.-M. (2012). “Were late roman and byzantine economies market economies? A comparative look at historiography” in Trade and Markets in Byzantium. ed. C. Morrisson (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection), 13–26.

Carrier, J. G. (2017). Moral economy: what’s in a name. Anthropol. Theory 18, 18–35. doi: 10.1177/1463499617735259

Carrier, J. G. (2022). “Introducing economic anthropology” in A handbook of economic anthropology. ed. J. G. Carrier. 3rd ed (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 1–8.

Clasby, R., and Nesbitt, J. (Eds.) (2021). The archaeology of the upper Amazon: Complexity and interaction in the Andean tropical Forest. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Coleman, S. (2022). “Ritual, rationality and intersections between economy and religion” in A handbook of economic anthropology. ed. J. G. Carrier. 3rd ed (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 204–215.

Colloredo-Mansfeld, R., and Delgaty, A. C. (2022). “Consumption” in A handbook of economic anthropology. ed. J. G. Carrier. 3rd ed (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 149–161.

Cook, S. (1966). The obsolete “anti-market” mentality: a critique of the substantive approach to economic anthropology. Am. Anthropol. 68, 323–345. doi: 10.1525/aa.1966.68.2.02a00010

Covey, R. A., and Dalton, J. A. (2025). Economies of the Inca world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

D’Altroy, T. N., and Earle, T. K. (1985). Staple finance, wealth finance, and storage in the Inka political economy. Curr. Anthropol. 26, 187–206. doi: 10.1086/203249

Dalton, J. A. (2024). The use of balances in late Andean prehistory (ad 1200–1650). Camb. Archaeol. J. 34, 737–756. doi: 10.1017/S0959774324000076

de Pleijt, A. M., and van Zanden, J. L. (2024). “Preindustrial economic growth: ca. 1270–1820” in Handbook of Cliometrics. eds. C. Diebolt and M. Haupert (Cham: Springer Nature), 681–697.

Durak, K. (2022). The use of non-commercial networks for the study of Byzantium’s foreign trade: The case of byzantine-Islamic commerce in the early middle ages. In: Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Byzantine Studies: Plenary Sessions, Venice and Padua, 22 August 2022, Venice, Venice University Press. Vol. 1, 422–451.

Fauvelle, M. (2025). The trade theory of money: external exchange and the origins of money. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 32:23. doi: 10.1007/s10816-025-09694-9

Fehren-Schmitz, L., Haak, W., Mächtle, B., Masch, F., Llamas, B., Tomasto, E., et al. (2014). Climate change underlies global demographic, genetic, and cultural transitions in pre-Columbian southern Peru. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 9443–9448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403466111

Feinman, G. M. (2008). “Economic archaeology” in Encyclopedia of archaeology. ed. D. M. Pearsall (New York: Academic Press), 1114–1120.

Feinman, G. M., Fang, H., and Nicholas, L. (2019). “Political unification, economic synchronization, and demographic growth: long-term settlement pattern shifts in eastern Shandong” in Weights and marketplaces from the bronze age to the early modern period. eds. L. Rahmstorf and E. Stratford (Kiel: Wachholtz), 355–376.

Feinman, G. M., and Garraty, C. P. (2010). Preindustrial markets and marketing: archaeological perspectives. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 39, 167–191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.012809.105118

Garraty, C. P. (2010). “Investigating market exchange in ancient societies: a theoretical review” in Archaeological approaches to market exchange in ancient societies. eds. C. P. Garraty and B. L. Stark (Boulder: University Press of Colorado), 3–32.

Graeber, D. (2001). Toward an anthropological theory of value: The false coin of our own dreams. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 91, 481–510. doi: 10.1086/228311

Grierson, P. (1959). Commerce in the dark ages: a critique of the evidence. Trans. R. Hist. Soc. IX, 123–140.

Gudeman, S. (2022). “Community and economy: economy's base” in A handbook of economic anthropology. ed. J. G. Carrier. 3rd ed (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 45–55.

Hartmann, R. (1971). Mercados y ferias prehispánicas en el área andina. Bol. Acad. Nac. Hist. 54, 214–235.

Harvey, A. (1990). Economic expansion in the Byzantine Empire, 900–1200. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hendy, M. F. (1985). Studies in the byzantine monetary economy c. 300–1450. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hendy, M. F. (1988). From public to private: the Western barbarian coinages as a mirror of the disintegration of late Roman state structures. Viator 19, 29–78. doi: 10.1484/J.VIATOR.2.301364

Hirth, K. G. (1996). Political economy and archaeology: perspectives on ancient Mesoamerican states. J. Archaeol. Res. 4, 151–180. doi: 10.1007/BF02229196

Hirth, K. G. (1998). The distributional approach: a new way to identify marketplace exchange in the archaeological record. Curr. Anthropol. 39, 451–476. doi: 10.1086/204759

Hirth, K. G. (2010). “Finding the mark in the marketplace: the organization, development, and archaeological identification of market systems” in Archaeological approaches to market exchange in ancient societies. eds. C. P. Garraty and B. L. Stark (Boulder: University Press of Colorado), 227–247.

Hutson, S. R. (2021). Distributional heuristics in unlikely places: incipient markets and hidden commerce. Archeol. Pap. Am. Anthropol. Assoc. 32, 95–108. doi: 10.1111/apaa.12146

Isaac, B. L. (2022). “Polanyi and social economy” in A handbook of economic anthropology. ed. J. G. Carrier. 3rd ed (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 24–34.

Jacobs, I. (2012). The creation of the late antique city: Constantinople and Asia minor during the 'Theodosian renaissance'. Byzantion 82, 113–164.

Jacobs, I. (2013a). Aesthetic maintenance of civic space: The ‘classical’ City from the 4th to the 7th C. AD. Leuven: Peeters.

Jacobs, I. (2013b). Five centuries of glory: the North–south colonnaded street of Sagalassos in the first and the sixth century A.D. Ist Mitt. 63, 219–266. doi: 10.34780/k4acmk57

Jacoby, D. (2013). “Rural exploitation and market economy in the late medieval Peloponnese” in Viewing the Morea: Land and people in the late medieval Peloponnese. ed. S. E. J. Gerstel (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection), 213–276.

Jacoby, D. (2015). “The economy of Latin Greece” in A companion to Latin Greece. eds. I. N. Tsougarakis and P. Lock (Leiden: Brill), 185–216.

James, T. G. H. (1984). Pharaoh’s people: Scenes from life in Imperial Egypt. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Laiou, A. E. (1995). “Byzantium and the commercial revolution” in Europa medievale e mondo bizantino. eds. G. Arnaldi and G. Cavallo (Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana), 239–253.

Laiou, A. E. (2002a). “The byzantine economy: an overview” in The economic history of Byzantium: From the seventh through the fifteenth century. ed. A. E. Laiou, vol. 3 (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection), 687–712.

Laiou, A. E. (2002b). “The byzantine economy in the Mediterranean context” in The economic history of Byzantium: From the seventh through the fifteenth century. ed. A. E. Laiou, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection), 3–38.

Laiou, A. E. (2002c). “Exchange and trade” in The economic history of Byzantium: From the seventh through the fifteenth century. ed. A. E. Laiou, vol. 2 (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection), 563–650.

Laiou, A. E. (2017). “Thessaloniki and Macedonia in the byzantine period” in Byzantine Macedonia: Identity, image and history. eds. J. Koder and V. Stanković (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill), 29–53.

Laiou, A. E., and Morrisson, C. (2007). The byzantine economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leidholm, N. (2023). “Governing the byzantine empire: politics and administration, ca. 850–1204” in How medieval Europe was ruled. eds. C. Raffensperger and C. Raffensperger (London and New York: Routledge), 107–125.

Lindh de Montoya, M. (2000). Finding new directions in economic anthropology. Econ. Sociol. Eur. Electron. Newsletter 1, 17–23.

Loewe, M. (2005). Everyday life in early Imperial China during the Han period, 202 BC–AD 220. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

Loewe, M. (2006). The government of the Qin and Han empires: 221 BCE–220 CE. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

Lopez, R. S. (1951). The dollar of the middle ages. J. Econ. Hist. 11, 209–234. doi: 10.1017/S0022050700084746

Lopez, R. S. (1959). The role of trade in the economic readjustment of Byzantium in the seventh century. Dumbarton Oaks Pap. 13, 67–85. doi: 10.2307/1291129

Lynch, T. F. (2022). “Reflection on the history of the study of transhumance, culture change, trails, and roads in the south-central Andes” in Caravans in socio-cultural perspective: past and present. eds. P. B. Clarkson and C. M. Santoro (London: Routledge), 71–84.

Mächtle, B., and Eitel, B. (2013). Fragile landscapes, fragile civilizations: how climate determined societies in the pre-Columbian south Peruvian Andes. Catena 103, 62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.catena.2012.01.012

Mader, C. (2019a). Sea shells in the mountains and Llamas on the coast: the economy of the Paracas culture (800 to 200 BC) in southern Peru. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Mader, C. (2019b). “The economic organisation of the Paracas culture (800–200 BC) in southern Peru” in Excavated worlds: 40 years of archaeological research on four continents (Bonn: German Archaeological Institute), 64–73.

Mader, C., Hölzl, S., Heck, K., Reindel, M., and Isla, J. (2018). The llama’s share: highland origins of camelids during the late Paracas period (370 to 200 BCE) in South Peru demonstrated by strontium isotope analysis. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 20, 257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2018.04.032

Mader, C., Reindel, M., and Isla, J. (2022). “Camelids as cargo animals by the Paracas culture (800–200 BC) in the Palpa valleys of southern Peru” in Caravans in socio-cultural perspective: Past and present. eds. P. B. Clarkson and C. M. Santoro (London: Routledge), 174–192.

Mader, C., Reindel, M., and Isla, J. (2023a). Economic directness in the western Andes: a new model of socioeconomic organization for the Paracas culture in the first millennium BC. Lat. Am. Antiq. 34, 385–403. doi: 10.1017/laq.2022.40

Mader, C., Reindel, M., Isla, J., Behl, M., Meister, J., and Hölzl, S. (2023b). In the land of the apu: Cerro Llamocca as a sacred mountain and central place in the pre-Columbian Andes of southern Peru. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 49:104045. doi: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2023.104045

Mango, M. M. (Ed.) (2009). Byzantine trade, 4th–12th centuries: The archaeology of local, regional and international exchange. Papers of the thirty-eighth spring symposium of byzantine studies. Farnham: St John’s College, University of Oxford.

Maniatis, G. C. (2003). Price formation in the Byzantine economy tenth to fifteenth centuries. Byzantion 73, 401–444.