- 1School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- 2Department of Linguistics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

This study examined how heritage children's experiences with the heritage language (HL) in the country of residence (e.g., children's generation, their HL use and richness) and the country of origin (e.g., visits to and from the homeland) may change as a function of the migration generation heritage children belong to, and how this may in turn differentially influence HL outcomes. Fifty-eight Greek-English-speaking bilingual children of Greek heritage residing in Western Canada and New York City participated in the study. They belonged to three different generations of migration: a group of second-generation heritage speakers, which were children of first-generation parents; a group of mixed-generation heritage children of first- and second-generation parents; and of third-generation heritage children with second-generation parents. They were tested on a picture-naming task targeting HL vocabulary and on an elicitation task targeting syntax- and discourse-conditioned subject placement. Children's performance on both tasks was predicted by their generation status, with the third generation having significantly lower accuracy than the second and the mixed generations. HL use significantly predicted language outcomes across generations. However, visits to and from the country of origin also mattered. This study shows that HL use in the country of residence is important for HL development, but that it changes as a function of the child's generation. At the same time, the finding that the most vulnerable domains (vocabulary and discourse-conditioned subject placement) benefited from visits to the country of origin highlights the importance of both diversity of and exposure to a variety spoken by more speakers and in different contexts for HL maintenance.

1. Individual differences in heritage language development

Migration waves for work and/or study between countries within the Global North (Wallerstein, 1974) throughout the last two centuries have led to an increase in communities who relocate from their country of origin to a new country of residence, where usually the societal language spoken is different from the one spoken in the country of origin. Recently arrived, first-generation migrants gradually become bilingual speakers, if they are not already prior to migration. In the new country of residence, the language spoken in the country of origin becomes the minority heritage language (HL) within the family and the immediate community (Grosjean, 2010; Montrul, 2015; Montrul and Polinsky, 2021). Once settled, the HL is passed on to consecutive generations of heritage speakers with different degrees of success. For all migration generations, exposure to the minority heritage language takes place from birth, and to the dominant societal language either from birth or early on via dominant language education and immersion to the wider community (Montrul and Polinsky, 2021). Given its minority status, HL learning in the country of residence takes place under pressure from the dominant, societal language. HL learning usually involves reduced exposure to the HL compared to the societal language, fewer opportunities to practice the HL with a limited number of speakers, who may be heritage speakers of the language themselves or second language learners of the HL, and in a limited number of settings (e.g., community schools, immediate family, and community). These conditions for language learning are responsible for the large variation in heritage speakers' experience with the HL and lead to variable HL proficiency and outcomes.

Studies to date have examined the sources of individual differences in heritage speakers primarily related to child-external variables in the context of the country of residence. For example, how much heritage children use the HL language within the family and the wider community, what opportunities they have to carry out different activities in the HL in diverse contexts or with different HL speakers, or whether they attend HL schools, what are also known in the literature as proximal variables that may influence HL outcomes (Paradis, 2023).

Two related issues have received less attention, at least in experimental quantitative approaches to HL development. The first one relates to how the child's HL experience changes as a function of the generation they belong to. In the context of the present study, the immigration generation that the child belongs to is taken to be a distal factor (Paradis, 2023) in that it can affect the quantity and the quality of input the child receives, which may in turn affect HL outcomes. The second issue focuses on the relative impact of proximal factors on HL outcomes related to the country of origin. The latter can be operationalized as the frequency and length of visits that heritage speakers make to the country of origin or visits from relatives from the country of origin.

The present study seeks to enrich our understanding of how proximal and distal factors interact and ultimately modulate HL outcomes by examining which proximal factors related both to the host and the home country may change as a function of generation, and how these, in turn, may differentially influence HL outcomes. In this respect, we revisited the Greek heritage speakers growing up in North America (New York City and Western Canada) that were examined in previous studies (Daskalaki et al., 2019, 2020, 2022), and asked how children's HL experiences may change as a function of the migration generation they belong to, and how this may differentially affect their language outcomes.

1.1. Heritage language experiences in the country of residence

Most studies to date have focused on how proximal factors related to the country of residence may affect HL acquisition. These include HL input quantity and quality, such early and current HL input and use, diversity of HL activities and timing of exposure to the majority language. Specifically, the relative amount of HL input that the child receives at the time of testing is a particularly strong indicator of HL outcomes across domains, e.g., vocabulary (Hoff and Core, 2013; Gagarina and Klassert, 2018; Czapka et al., 2021), morphosyntax (Gagarina and Klassert, 2018; Chondrogianni and Schwartz, 2020) or syntax-discourse phenomena (Jia and Paradis, 2015), although these domains may be differentially affected. For example, vocabulary has been shown to be more sensitive to input reduction compared to morphosyntax (Armon-Lotem et al., 2021; Gordon and Meir, 2023). Discourse-conditioned word orders have been shown to be more vulnerable compared to syntactically-conditioned word orders (e.g., Argyri and Sorace, 2007; Daskalaki et al., 2019, 2020).

The HL input received in early childhood has also been shown to have long-lasting effects, suggesting that early exposure might be critical for HL acquisition, especially for structures that are early acquired. For instance, Chondrogianni and Schwartz (2020), in their study of school-aged Greek heritage children, found that the amount of HL input that children had received before the age of 3 affected their sensitivity to case cues at the time of testing. Similarly, Andreou et al. (2021) and Torregrossa et al. (2023a,b), in their studies of school-aged Italian heritage children found that children's accurate production of Italian complement clauses (an early acquired structure) was affected by the amount of HL received between 0 and 3 years.

A factor that affects how much input heritage children receive in the early years is the age of consistent exposure to the majority language, also coined as Age of Onset (AoO). This is because children with an older AoO have longer to consolidate the development of structures in their HL due to longer exclusive exposure to the HL. Better HL outcomes as a function of delayed AoO to the majority language have been reported for vocabulary (Gollan et al., 2015; Armon-Lotem et al., 2021; Czapka et al., 2021) and morphosyntax (Janssen et al., 2014; Albirini, 2018; Gagarina and Klassert, 2018; Soto-Corominas et al., 2021; see though Makrodimitris and Schulz, 2021; Torregrossa et al., 2023b, for no effects of AoO on HL outcomes).

Finally, HL richness, above and beyond HL quantity, may also be relevant for children's HL development (Kupisch and Rothman, 2016; Blom and Soderstrom, 2020). HL richness may be operationalized in terms of the number of HL interlocutors interacting with the child (Gollan et al., 2015), the frequency in which the child engages with HL sources, such as books and media (Jia and Paradis, 2015), and the type and length of HL instruction (Armstrong and Montrul, 2022; Torregrossa et al., 2023a). For instance, Gollan et al. (2015) found that Hebrew-English children's ability to name objects in a Hebrew picture-naming task correlated positively with the number of different Hebrew interlocutors.

Importantly, even though both input quantity and quality/richness matter for HL acquisition, qualitative aspects may prove to be more relevant for structures and vocabulary items that are less frequent in colloquial registers. Torregrossa et al. (2023b), in their study of heritage Portuguese in Germany, found that formal instruction and number of HL speakers, rather than home language use, were predictive of children's performance in late acquired complex syntactic structures. Similarly, Hulsen (2000) found that HL use outside the home, rather than home language use, were predictive of Dutch immigrants' vocabulary, presumably because language use outside the home entails language use in a diversity of contexts and with a diversity of speakers.

In the present study, we examined the predictive strengths of these different variables associated with the country of residence, along with the ones related with the country of origin, to which we turn in the next section.

1.2. Heritage language experiences related to the country of origin

How proximal factors related to the country of origin modulate HL outcomes has received less attention in the HL acquisition literature. What we operationalize as proximal factors related to the country of origin in this study are the number and duration of short visits to the country of origin primarily for leisure, what has been coined in the literature as “diaspora tourism” (Holsey, 2004), as well as visits from relatives from the country of origin to the country of residence. Recent studies have showcased the socio-cultural benefits of diaspora tourism on different generation of immigrants and especially on children of migrant parents, highlighting how short trips to the homeland boost transnational attachments and emotional ties with the ancestral home (Ruting, 2012; Huang et al., 2016). For second- and third-generation children, however, their variable HL proficiency may act as a constraint to their transnational activities (Levitt and Waters, 2002). In this respect, short visits of heritage speakers to the country of origin and of relatives from the country of origin could counteract the process of HL decline across generations, as they can be both seen as a proxy of naturalistic exposure to the variety spoken in the country of origin, from a variety of speakers, in a variety of contexts (Montrul, 2015). The importance of exposure to diverse sources of input from a variety of speakers and in varied contexts has been shown for both monolingual (Huttenlocher et al., 2010) and bilingual (minority) language development (Fishman et al., 1971; Gathercole and Thomas, 2009; Gollan et al., 2015), as this diversity increases the range of syntactic structures in the input and enhances the functional significance of the language (Unsworth et al., 2019).

Evidence for heritage language reversal after re-immersion in the country of origin has been reported in two lines of bilingualism research. The first one relates to studies on first-generation bilingual adult speakers who are re-exposed to the heritage language through short-term visits (between 2 and 6 weeks per year) to the home country, either for study or for leisure (Chamorro et al., 2016; Genevska-Hanke, 2017; Gargiulo and van de Weijer, 2020; Casado et al., 2023). These studies have shown that the heritage language can be re-activated even after short re-immersion, leading to improved performance on structures that were vulnerable prior to re-immersion.

The second line of research comes from studies on returnee children and adults, namely heritage speakers who returned from the country of residence to the country of origin as children and adolescents (Flores et al., 2017, 2022; Flores, 2019; Kubota et al., 2020, 2021) or as adults (Genevska-Hanke, 2017; Köpke and Genevska-Hanke, 2018). This line of research examines whether heritage language reversal is possible after re-immersion to the country of origin and how long it takes (Flores and Snape, 2021; Montrul, 2023). Importantly, regardless of whether these speakers were born in the country of origin before moving to the country of residence, in most cases, HL acquisition occurred under reduced input conditions in the minority setting and under pressure from the majority language in the country of residence for an extended period. Studies with returnees have shown that re-immersion to the country of origin leads to improved performance on a range of structures in the heritage language, after short-term re-immersion, and to monolingual-like performance after long-term re-immersion. This is particularly the case for returnees who were re-immersed to the country of origin as children and/or who had delayed AoO to the societal language in the country of residence (e.g., Flores and Rato, 2016; Flores and Snape, 2021; Montrul, 2023).

What is more, short- or long-term re-exposure to the native variety in the country of origin does not affect all language domains equally. Numerous studies have shown that structures that are more sensitive to input fluctuations, e.g., vocabulary (Casado et al., 2023; Gordon and Meir, 2023), as well as structures at the syntax-discourse interface, which may be more vulnerable to crosslinguistic pressure or influence (CLI) from the dominant language, may be more vulnerable in minority/heritage language acquisition contexts compared to syntactically conditioned structures (Argyri and Sorace, 2007; Daskalaki et al., 2019, 2020). Whether or not these structures are equally re-activated after re-immersion in the country of origin seems to be a function of the length of re-immersion and the experimental task. For example, Antonova-Unlu et al. (2021) showed that adult Turkish-German returnees who returned to Turkey after puberty and were tested 8 years after residing in the country of origin performed differently from the monolinguals in a sentence completion task and on a grammaticality judgment task that targeted case marking on direct specific objects, an interface structure that requires the co-ordination of morphology and discourse, whereas they did not differ on the non-interface structure. Conversely, Chamorro et al. (2016) showed that a group of adult Spanish-English bilingual speakers residing in the UK and tested after being re-exposed to Spanish after a 2-week visit to Spain behaved native-like in their processing of pronoun resolution in Spanish and only displayed delayed sensitivity to pronoun bias compared to the monolingual group. More monolingual-like pronominal antecedent processing was also reported in a timed reading task with Italian-Swedish bilingual speakers who were residing in Sweden and returned to Italy for their summer holidays (Gargiulo and van de Weijer, 2020). These late bilingual attriters (they had migrated to Sweden as adults) were tested on pronominal antecedent preferences before and after spending ~1 month in Italy. They displayed more monolingual-like Italian performance after the short re-immersion to the Italian context compared to their performance prior the short visit.

In a similar vein, a recent study tested first-generation Polish-English adult immigrants before re-immersion in the L1 (Polish) after short trips to Poland (on average ~3 months) and 7 days after L1 re-immersion on a picture-naming task (Casado et al., 2023). These were compared to a group of Polish-English bilinguals living in Poland. The authors found that the bilingual participants had faster naming latencies after L1 re-immersion compared to during L2 immersion, but only for high frequency words. Importantly, there were no significant differences between the migrant group residing in the UK and the control group in Poland. The authors attribute these results to the fact that most of their participants maintained close ties with their native country by retaining close ties with the Polish community in the UK.

Studies targeting HL vocabulary re-activation with long-term returnees have shown that they have improved vocabulary skills compared to heritage speakers (Treffers-Daller et al., 2016; Flores et al., 2022) even within 1 year after return to the country of origin. What is more, a study by Kubota et al. (2021) showed that Japanese-English bilingual returnee children who were more dominant in their L2 (English) and less dominant in their heritage language (Japanese) benefited the most in their lexical diversity from the shift in language environment after a year of immersion in Japanese and were able to catch up to their peers who were already dominant in Japanese or balanced in their two languages after 1 year of re-immersion (Kubota et al., 2021).

To our knowledge, no study to date has examined the effect of short-term visits to and from the country of origin on outcomes in child HL development. Following Montrul (2015), we take visits to and from the country of origin to be a proxy of cumulative exposure to the native variety spoken in the country of origin. At the same time, short-term visits provide heritage speakers with more opportunities to practice their heritage language in more contexts and with a variety of speakers. In this respect, visits to and from the country of origin can also be perceived as a marker of HL richness, where more opportunities to hear and practice the HL are provided.

1.3. Migration generation modulates heritage language experience and outcomes

As Montrul (2022, p. 42) observes, comparisons between first- and second-generation immigrants allow us to trace continuity and discontinuity in language transmission patterns between generations, and to understand the language-external factors driving these changes. Sociolinguistic and ethnographic studies have shown that the language practices of heritage communities, summarized as proximal factors above, may change as a function of the generation they belong to (Fishman, 2012). For example, the first generation may acquire some proficiency in the majority language, but prefers to speak the native minority language, especially at home. Their children (second-generation migrants) born and raised in the host country may retain facility in their parents' spoken language. They are generally fluent in the majority language and often prefer it over their parents' language, with some even conversing with parents in the majority language (e.g., Nakamura Lopez, 1996). By the third generation, monolingualism in the majority language is the prevalent pattern and knowledge of the ancestral mother tongue is fragmentary at best (Soehl, 2016).

More quantitative, experimental studies have also shown that linguistic outcomes change across generations, although this change is not wholesale across all language domains. In her seminal work with first-, second- and third-generation Mexican-American adult immigrants, Silva-Corvalán (1994) reported a gradual decline of licit post-verbal subjects across generations, which she linked to loss of pragmatic constraints. Several other studies have reported a gradual change of grammatical forms and functions across a range of linguistic phenomena and languages with adult immigrants. For example, Irizarri Van Suchtelen (2016) reported lower performance of Dutch gender in first- vs. second-generation immigrants in Chile. Pascual y Cabo (2020) also found that child and adult heritage speakers significantly omitted the preposition “a” with Spanish psych verbs, whereas this was less widespread in first-generation speakers. Phenomena also at the syntax-discourse interface, such as null and overt pronouns have been shown to be particularly vulnerable across generations, albeit with mixed results as to the level of affectedness of these structures across languages (see Montrul, 2022 for a review of relevant studies). For example, Daskalaki et al. (2020) showed that second generation adult heritage speakers differed from first-generation heritage speakers on subject placement in a syntactically-conditioned context such as embedded interrogatives (EI), as in DhenNEG thimame1SG tiCOMP efaghe3SG iDEF.FEM Maria “I don't remember what Maria ate,” compared to a discourse-conditioned context, such as an answer to a wide focus (WF) question, as in Q: “What happened with Mario's toy?” A: ToCL.NEUT.ACC pire3SG oDEF.MASC Marios “Marios took it” (see also examples 1 and 2 in Section 2.3.2.2.2 for more detail). Daskalaki et al. (2022) also reported that third-generation children differed from mixed- and second-generation children on subject placement in EI, whereas all three generations differed from each other on the type of object pronominal forms used in the WF condition. In the domain of vocabulary, Hulsen (2000) tested three generations of Dutch heritage speakers in New Zealand on a picture-naming (production) and on a picture-matching (comprehension) task targeting cognate and non-cognate words of different frequency. Hulsen (2000) reported that participants accuracy and latencies on a picture-naming task decreased as a function of generation and cognate status. That is, the three generations did not differ from each other on cognate words between Dutch (heritage) and English (societal language) but had lower accuracy on non-cognate words, especially the low-frequency ones, confirming the cognate facilitation effect with adult heritage bilingual speakers (Costa et al., 2000).

Despite these well-documented effects of generation on language shift in ethnographic studies and in experimental studies with child and adult immigrants, very few studies have examined how specific proximal factors change as a function of generation and how they affect different linguistic properties. Hulsen (2000), for instance, compared the language practices and self-rated proficiency of three generations of adult Dutch immigrants in New Zealand. She found that first-generation Dutch immigrant adults give themselves a higher L1 proficiency ranking, have more L1 contacts in the country of origin, and use their L1 more often than second- and third-generation immigrants. Both L1 use and generation, emerged as significant predictors of HSs' productive and receptive vocabulary knowledge; performance increased with L1 use, but both performance and L1 use declined across the three generations. When these heritage speakers were examined as a group regardless of generation, Hulsen (2000) reported moderate positive correlations between naming accuracy and latencies and how often these heritage speakers maintained contact with Dutch speakers living in the Netherlands regardless of the word's cognate status or frequency. These results suggest that the migrants who had more extensive contact with their home country exhibited higher naming accuracy and faster naming latencies compared with the migrants with less contact with native speakers living in the Netherlands.

Similarly, Daskalaki et al. (2020) showed that changes to parental input quality as a function of generation, where second-generation parents produced significantly more preverbal subjects compared to the first- -generation parents in contexts where post-verbal subjects were highly preferred. Importantly, the pattern was passed on to their children with third generation children (whose parents were second generation) using a higher rate of illicit preverbal subjects than mixed generation children (whose one parent was first- and the other parent was second-generation).

In the present study, we will contribute to this line of research by examining the association between generation, proximal factors, and HL outcomes in a group of Greek immigrant children in North America. A novelty of our study also lies in investigating the proximal factors related to the country of residence and the country of origin separately.

2. Present study

The present study had two main goals. The first one was to investigate how various proximal variables related to children's exposure to the heritage language both in the country of residence and the country origin may change as a function of the generation they belong to. Second, we wanted to investigate how heritage children's performance on vocabulary and subject placement domains is affected by proximal externals factors as a function of generation. Specifically, we asked the following research questions:

1. Do proximal variables in heritage children change as a function of generation?

2. Are there differences between second-, mixed- and third-generation children in terms of vocabulary and subject placement?

3. How is this performance affected by proximal external factors as a function of generation?

To test subject placement, we focused on two contexts (following Daskalaki et al., 2019, 2020): embedded interrogatives (EI), a narrow syntactic context, where post-verbal subjects are required and wide focus (WF), a syntax-discourse context, where post-verbal subjects are merely preferred and not disallowed.

2.1. Open questions

In our previous studies, we showed that heritage children as a single group performed worse on subject placement in the WF condition than the EI condition, and that the two conditions were differentially affected by current amount of HL use (Daskalaki et al., 2019). We also reported that the third-generation children had lower accuracy than the mixed generation children on WF and on EI, and that they both differed from their monolingual peers (Daskalaki et al., 2020).1

What we have not yet examined in our studies is the interplay between generation and proximal factors, and how proximal factors may differentially modulate performance across generations. Furthermore, our studies so far have focused on grammatical domains, whereas other domains that are also susceptible to variable input, such as vocabulary, have not been examined. For those reasons, in the present study, we revisited the two subject placement conditions we examined in Daskalaki et al. (2019, 2020), but this time we investigated whether the two conditions differed as a function of generation by including a group of second-generation heritage children, same as the one in Daskalaki et al. (2022). We also extended our investigation to another domain, that of lexical accuracy by introducing a picture-naming task that measures children's expressive vocabulary in the heritage language. In the present study, we also divided the proximal variables related to HL experience into the ones that are associated with the country of residence, such as heritage children's early and current amount to heritage Greek, AoO to the societal language, and HL Richness, and into the ones associated with the home country, such as visits of children to and of relatives from the country of origin. As a last step, we asked how the factors that may change as a function of generation may also differentially affect children's language across the three generations.

2.2. Predictions

Regarding RQ1, we expected proximal related to HL use and experience to change as a function of generation (e.g., early and current HL use, HL richness, visits to and from the country of origin; Hulsen, 2000), but not necessarily AoO, since the timing of schooling is the same across migration groups (and also given our selection criteria that did not include children exposed to English after the age of 4 years).

Regarding RQ2, and similarly to previous studies, we predicted that the third generation would differ from the other two on both subject placement conditions, but the differences to be more pronounced for the syntax-discourse (WF) condition. We also expected differences between the second and the mixed generations at least on the syntax-discourse (WF) condition, which is the one more vulnerable given its interface status and also more susceptible to crosslinguistic influence from English. Additionally, if lexical access and retrieval of words as measured by the lexical task also changes as function of generation, we also expected the three generations to differ from each other on picture-naming accuracy (see Hulsen, 2000). Similarly to previous studies on single word picture-naming, we expected cognates between Greek and English to have higher accuracy than non-cognates, as the morphophonological and semantic similarity of cognate words has been shown to increase word retrieval and articulation. We also expected high frequency words to elicit higher accuracy than lower frequency words. However, given the frequency corpus that we used derived from written corpora, we were cautious with our interpretation of any potential lack of lemma frequency effects in our study.

Finally, we expected factors that change as a function of generation to differentially affect HL outcomes. In the context of the linguistic phenomena we targeted in the present study, we took visits to and from the country of origin to provide opportunities for contact from more speakers and in a diversity of context. For vocabulary, re-immersion in the country of origin may provide heritage speakers with more opportunities to hear and produce words that may not be used as frequently in the country of residence due to the restricted contexts of use and speakers (Gollan et al., 2015; Casado et al., 2023). For subject placement, visits to and from the country of origin may indicate contact with the variety where VS is highly preferred (see Daskalaki et al., 2019, 2020, 2022 for monolingual speakers' performance tested in Greece). This (re-)immersion into this variety could potentially boost heritage children's production of VS over SV structures, even in contexts that are vulnerable to CLI and more likely to give rise to SV (e.g., WF condition). Finally, it may be the case that visits to Greece facilitate conditions that are susceptible to input effects and/or to CLI more than visits of relatives from Greece. This might be because, when relatives visit from Greece, the HL interaction continues to take place in the country of residence and under pressure from the majority societal language, and in more limited contexts compared to the ones in the country of origin.

2.3. Method

2.3.1. Participants

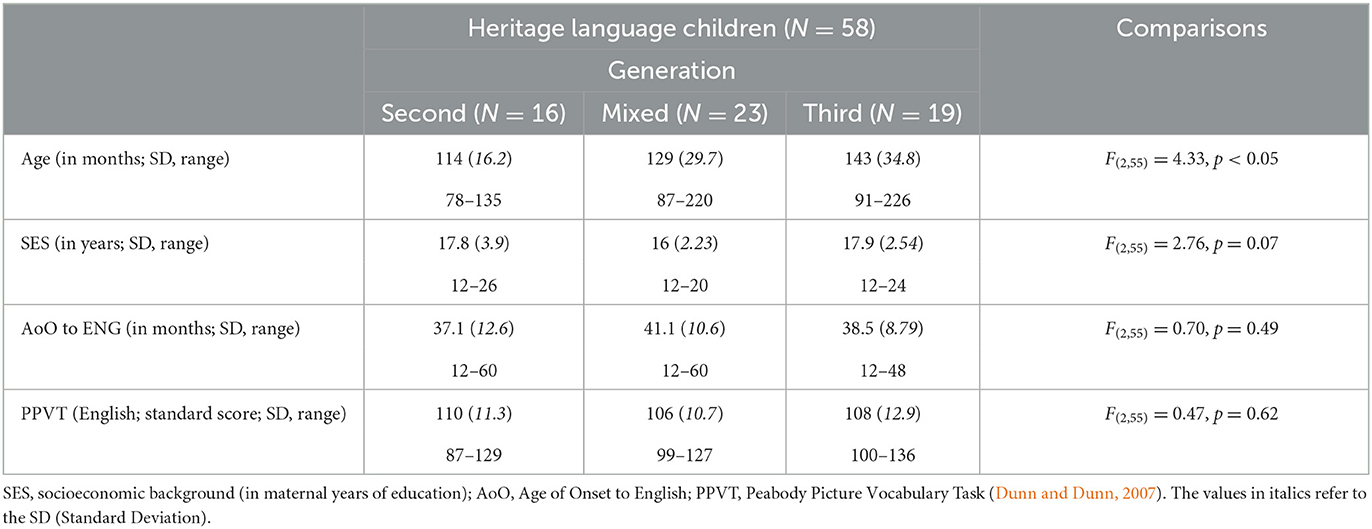

To answer our research questions, we collected data from two groups of speakers of Greek. There were 58 heritage language children and adolescents from North America aged between 6;5 to 18;8 years old.2 They were raised either in Western Canada (WC; N = 30) or in New York City (NYC; N = 28) and belonged to three different generations of immigration. There were 16 second generation children (whose both parents were first-generation immigrants), 23 mixed generation children (whose one parent was a first-generation immigrant, and the other parent was a second-generation immigrant), and 19 third generation children (whose both parents were second-generation immigrants). Independently of generation and city/country of residency, all heritage language children had attended a mainstream English school and a Heritage Greek Language school for 4 h per week. Children who had immigrated after the age of four (two children), children who used a third language at home (two children), and children who were discontinued due to poor performance/responsiveness during the sessions (eight third generation children) were excluded from the study. The three immigration generations did not differ in their knowledge of English, as evidenced by their standard scores on the PPVT (Table 1). However, the second-generation children were younger than the third-generation children (p < 0.01), whereas the mixed and the second generations did not differ from each other (p = 0.12). The mixed-generation children had marginally lower SES than their second- (p = 0.07) and significantly lower than their third-generation peers (p < 0.05). The final numbers of participants along with their biographical characteristics (per group and generation) are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Participants' mean age, Age of Onset (AoO) to English, socioeconomic level (SES), and English proficiency (PPVT).

2.3.2. Materials

2.3.2.1. Background measures

2.3.2.1.1. Parental questionnaire

To collect information about our participants' biographical characteristics and language practices, we used Daskalaki et al.'s (2019) parental questionnaire (ALEQ_Heritage), which is an adaptation of Paradis (2011) original ALEQ (Alberta Language and Environment Questionnaire). The questionnaire was administered to parents through face-to-face interviews. It included questions concerning the children's place and date of birth, generation, type of schooling, and socio-economic status (SES). In addition, it included questions concerning heritage language children's experience with Greek and English, such as their Age of Onset to the societal language English (AoO), their relative use of Greek at home (current HL use), their visits to and from Greece in the past 4 years prior to testing, and their experience with Greek media, books, and extracurricular activities (HL Richness). For AoO, we used the children's age of enrolment in an English-speaking school (nursery or primary school). The amount of GR use at home corresponded to the mean proportion of the amount of Greek that children received from and directed to other family members (parents, grandparents, siblings), at the time of testing. It was calculated on a scale from 0 (=mostly English; Greek almost never) to 4 (=mostly Greek; English almost never). Additionally, we calculated Greek language input in early childhood (before the age of 4 years), using the same questions and scale, as above. As for the richness of GR use, it corresponded to the mean proportion of the frequency of Greek language activities, including reading Greek books, watching Greek TV shows, and attending Greek extracurricular activities, such as Greek dance lessons. It was calculated on a scale from 0 to 2 (0 = almost never; 1 = at least once per week; 2 = everyday). We also calculated children's number of visits to the heritage country and the number of visits by relatives from the heritage country to Canada or NYC in the past 4 years prior to testing by summing up the duration of visits in weeks over that 4-year period.

2.3.2.1.2. English proficiency

To assess children's proficiency in English, we used the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Task (PPVT−4th edition; Dunn and Dunn, 2007). This is a receptive vocabulary task standardized with North American children. In this task, heritage language children were presented with a panel of four pictures and were asked to choose the picture that corresponded to the word spoken by the experimenter. Raw scores were converted into standard scores (Table 1). All heritage language children met monolingual age-appropriate norms. There were no differences between generations in the children's proficiency in English.

2.3.2.2. Experimental measures

2.3.2.2.1. Picture-naming task

To assess children's expressive vocabulary in Greek, we used a picture naming task developed by Vogindroukas et al. (2009). In this task, which was the only available vocabulary task standardized with monolingual Greek-speaking children, children were presented with a total of 50 black-and-white flashcards and were asked to name the object depicted on the flashcard. The flashcards targeted nouns of increasing difficulty, ranging from items that are likely to be used in the context of a home/school conversation, such as klidhi “key” (Item 1) and fidhi “snake” (item 2), to more specialized items, such as dhoksari “bow” (item 49) and trulos “dome” (item 50). Twelve items in the task consisted of cognate words between Greek and English (see Supplementary Table 2). The decision to classify words as cognates between Greek and English was based on psycholinguistic (phonological or orthographic resemblance between the Greek and the English word) rather etymological criteria, as the latter may not be immediately obvious to the lay participant and especially to children, as suggested by Carroll (1992). Given the oral nature of the task, we relied specifically on phonological similarity between the Greek and the English words. We also checked for the items' lemma frequency using the Hellenic National Corpus (HNC; ILSP, 2021).3 According to this corpus, cognate words had on average lower accuracy than non-cognate words (cognates: mean = 0.004%, SD = 0.0031, range = 0.002% −0.0091%; non-cognates: mean = 0.010%, SD = 0.016, range = 0.002–0.06%).

The scoring of the picture naming task followed the vocabulary scoring conventions developed by Haman et al. (2015). Correct responses were given a value of “1,” and included target forms, as well as regional variants and synonyms (e.g., chrisafika instead of kosmimata “jewelry”). Erroneous responses were given a value of “0” and consisted primarily of no responses. There was also a very small rate of erroneous responses involving semantic deviations (e.g., eklisia “church” instead of trulos “dome”), innovations (e.g., to spiti tu fos “the house of light” instead of faros “lighthouse”), and words with English roots and Greek suffixes (e.g., i kasta instead of o epidhesmos/jipsos “the cast”). Mispronunciations (e.g., /helikoptero/instead of/elikoptero/”helicopter”) and incorrect inflections (e.g., wrong grammatical gender) were disregarded and the response was coded as correct. There was no discontinue rule and all items were administered.

2.3.2.2.2. Subject placement elicitation task

To test subject placement in discourse-pragmatic and narrow syntactic contexts, we used Daskalaki et al.'s (2019) elicited production task (adapted from Argyri and Sorace, 2007). In this task, participants were shown pictures on a laptop screen and were subsequently asked a question that prompted the target structure. There was a total of four conditions, targeting subject/object form and placement. Only two of these conditions were analyzed for purposes of the present study: The wide focus condition (WF)—a discourse-pragmatic condition, where subjects are preferably post-verbal—and the embedded interrogative condition (EI)—a narrow syntactic condition, where subjects are obligatorily post-verbal in Greek.

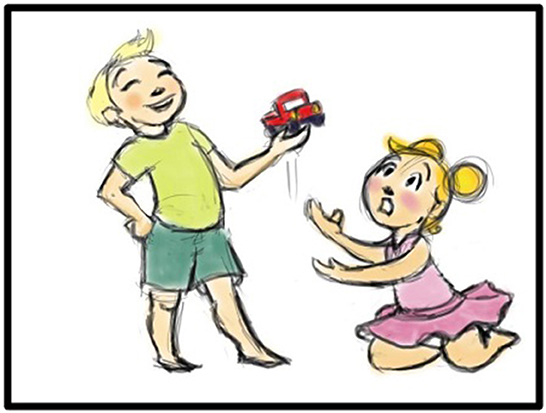

In the WF condition, participants were presented with pictures depicting two animated characters (e.g., a boy playing with a truck and a girl, Eleni, looking clearly upset; Figure 1). After introducing the characters and the situation, the experimenter would ask a wide focus question, such as ti ejine to fortigho tis Elenis? “what happened with Eleni's truck?” The felicitous response in the monolingual Greek variety involves a post-verbal subject (1).

1. a. Experimenter: To aghori lejete Jianis ke to koritsi Eleni. I Eleni epeze me ena fortigho. Ti ejine to fortigho tis Elenis? “The boy's name is Janis and the girl's name is Eleni. Eleni was playing with a truck. What happened with Eleni's truck?”

b. Expected Response: To pire (V) o Jianis (S)

it.Obj.Cl took.3SG the Jianis.NOM

“Jianis took it.”

Figure 1. Sample picture for the Wide Focus (WF) condition. Reproduced with permission from Daskalaki et al. (2019).

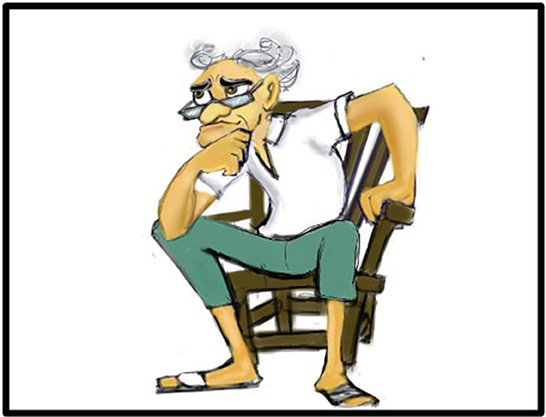

In the EI condition (Figure 2), participants were presented with the picture of a grandparent, who complained about forgetting his or her grandchild's activities. Participants were then prompted to complete an embedded interrogative (i jiajia/o papus den thimate “Grandpa/grandmother doesn't remember....”), which in the monolingual Greek variety requires a post-verbal subject (2).

2. a. Experimenter: O egonos mu, mu ipe ti djiavase, ala dhen thimame tora. Ti dhen thimate o papus? Ksekina tin apandisi su me to dhen thimate. “My grandson told me what he read, but I don't remember now.

What doesn't the grandfather remember? Start your answer with he doesn't remember…”

b. Expected Answer: dhen thimate ti dhiavase (V) o egonos tu (S)

NEG remember.3SG what read.3SG the grandson.NOM his.POSS

“He doesn't remember what his grandson read”.

Figure 2. Sample picture for the embedded interrogatives condition. Reproduced with permission from Daskalaki et al. (2019).

There were eight items per condition resulting in 32 items overall. In both conditions reported in this study (EI and WF), responses with post-verbal subjects were coded as correct and were given a value of “1,” whereas responses with preverbal subjects were coded as incorrect and were given a value of “0.” Incomprehensible responses, responses that did not represent the target structure, and responses with missing verbs or English verbs were coded as “NA” and were excluded from calculation. This amounted to 3.6% of the total data (2.4% in EI; 1.2% in WF).

2.3.2.3. Procedure

Children were tested in person either in their Greek school or at their home by a Greek-English bilingual speaker. All tasks except for the ALEQ were video-/audio-recorded. Testing lasted ~1 h.

2.3.2.4. Data analysis

Data analysis was carried out using the R statistical software (version 4.0.2; R Core Team, 2021). To answer research question 1, namely how proximal factors change as a function of Generation, we ran mixed effects linear regression models with the proximal variables as the dependent variables, Generation as the predictor variable, and participants as the random effects. To answer research question 2, namely whether heritage children's accuracy on vocabulary, EI and WF changes as a function of Generation, we ran two mixed-effects regression models with vocabulary (Model 1) or syntactic condition (Model 2) as the dependent variables and Generation as the between-participants fixed effect. In the vocabulary model, we added cognate status (cognates/non-cognates) and HNC lemma frequency as the within-participants fixed effects. In the syntax model, Condition (EI, WF) was the within-participants fixed effect. Given that there were differences between generations in SES and Age, we also added Age and SES as covariates to the models. To answer research question 3, namely how children accuracy is affected by proximal external factors as a function of Generation, we first ran non-parametric Spearman rho ranked correlations to check for collinearity between the proximal variables. We then ran stepwise regression models to identify the (set of) proximal variables that best predict the linguistic outcomes in our study. In the vocabulary model, we checked for interactions between cognates/frequency and Generation. Given that the cognates had overall lower frequency than non-cognates according to the HNC corpus, and the cognates were considerably fewer than the non-cognates in the study, we did not explore the interaction between cognate status and frequency to minimize any biases related to differences in sample size in the analysis. In the syntax model, we checked for the interaction between Condition (EI, WF) and Generation. For the proximal factors that were included in the final model with Generation, we checked for both main effects and interactions and only kept the model with interaction if it significantly improved the fit.

All linear and logistic mixed-effects models were run using the lmer package (Bates et al., 2015). We also used the lmerTest package to calculate the p-values for the linear regression models. Across all analyses, the maximum random effect structure was included, that is random effects and intercepts by-subject and by-item, to the extent that this was possible. When the models did not converge, models with by-subject random intercepts only were run. After the random-effects structure was established, we followed backwards selection of the fixed effects. At each step, the reduced model was compared to the previous model using a log likelihood ratio test with the anova function, and the reduced model was retained when it did not entail a significant loss of model fit. We also used jtools (Lüdecke, 2021) to summarize and compare model outputs and visualize model coefficient during the analysis. All continuous predictors were centered using the scale function from the “base” package. To establish the random effect structure and the optimal model, we followed the same procedures as the ones for the fixed effects. We also checked for collinearity among the proximal variables and the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for the variables in each model using the car package (Fox and Weisberg, 2019). A VIF close to 1 shows low chance of collinearity among factors, and a VIF below five indicates moderately correlated variables. Visualizations of the groups' accuracy on the different conditions were obtained using the “ggplot2” package (Wickham, 2016), whereas interactions between variables were depicted using the “sjPlot” package in R (Lüdecke, 2021). All data and analyses can be found on OSF (https://osf.io/fscgv/?view_only=5959931d27f74a099b91031d8df7bd71).

3. Results

3.1. How proximal variables change as a function of generation

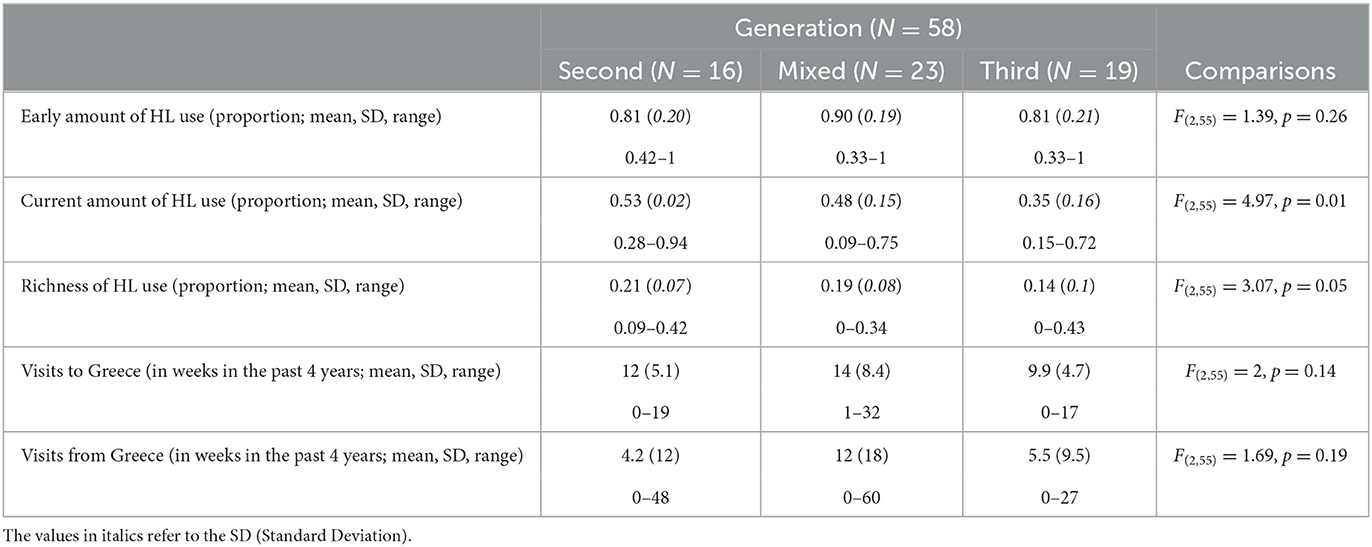

To answer the first research question about how proximal variables change as a function of the child's generation, we first calculated children's mean early and current amount of HL use, their richness of HL use, their mean visits to the HL, and their mean AoO to English in months for each generation separately (Table 2).

Table 2. Mean (SD, range) early and current amount of heritage language (HL) use (Greek), richness of HL use and visits to and from the country of origin (in weeks) as a function of generation.

How much Greek was used in the family in the early years did not change as a function of Generation, and it remained high across the three generations (~84% across the three generations). There were also no differences between groups in the duration of visits from relatives from Greece to the country of residence. However, the third generation had significantly fewer HL Richness activities than the second generation (E = −0.07, SE = 0.03, t = −2.43, p < 0.05), whereas there were no differences between the second and the mixed generations in HL Richness (E = −0.04, SE = 0.03, t = −1.63, p = 0.11). The three generations also differed in their current HL use, with the third were using the HL significantly less than the second (E = −0.18, SE = 0.06, t = −2.98, p < 0.01) and the mixed generation (E = −0.13, SE = 0.05, t = −2.38, p < 0.05), whereas the second and the mixed generations did not differ from each other (E = −0.05, SE = 0.06, t = −0.84, p = 0.41). The third generation also differed from the mixed generation in how much time they spent in Greece over the past 4 years (E = −4.05, SE = 2.02, t = −2, p = 0.05).

3.2. Changes to heritage children's lexical and syntactic accuracy as a function of generation

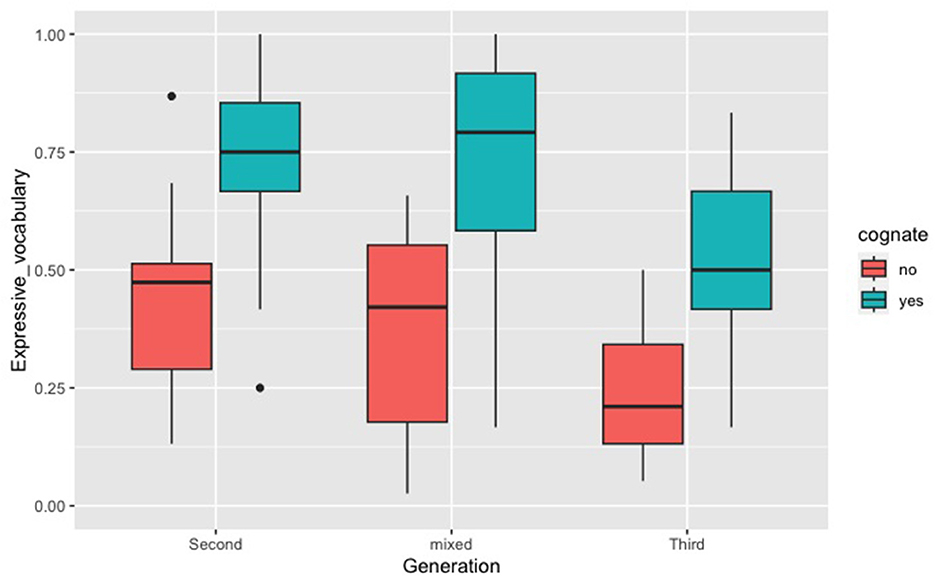

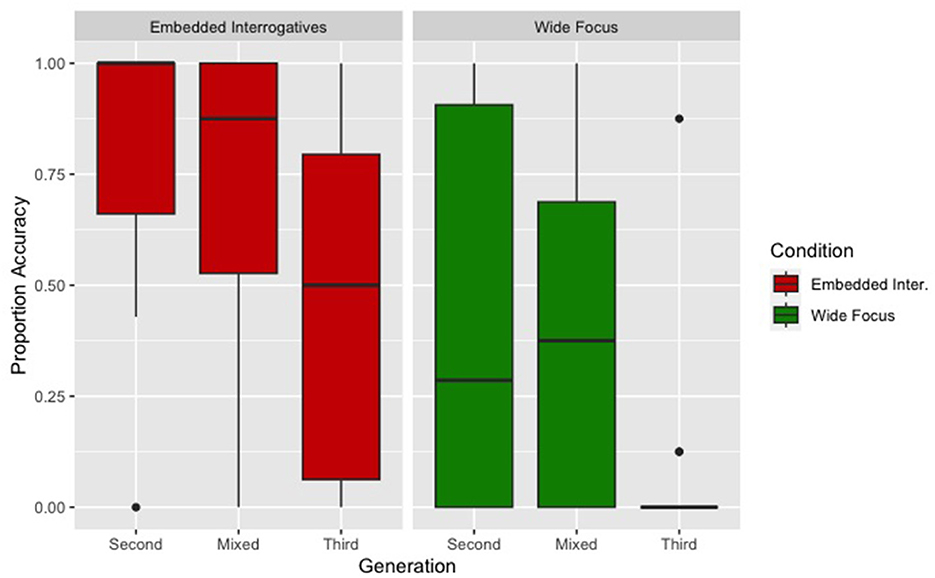

To answer research 2, namely whether there were differences in children's accuracy as a function of generation, we first calculated children's mean overall accuracy on the picture naming task (expressive vocabulary) for cognates and non-cognates separately and on the two syntactic conditions (EI, WF) of the subject placement elicitation task.4 Figures 3, 4 present children's accuracy on the picture-naming and the subject placement tasks across generations.

Figure 3. Heritage children's accuracy on the picture-naming task as a function of cognate status and generation.

Figure 4. Heritage children's accuracy on the subject placement task as a function of cognate status and generation.

To investigate whether the three generations differed from each other on vocabulary and syntax respectively, we ran two separate mixed-effects regression analyses. The first one examined differences among generations in terms of vocabulary; the second analysis investigated differences among the three generations in subject placement in the EI and the WF condition. Since the three generations differed in age, we added Age and SES as covariates in the model.

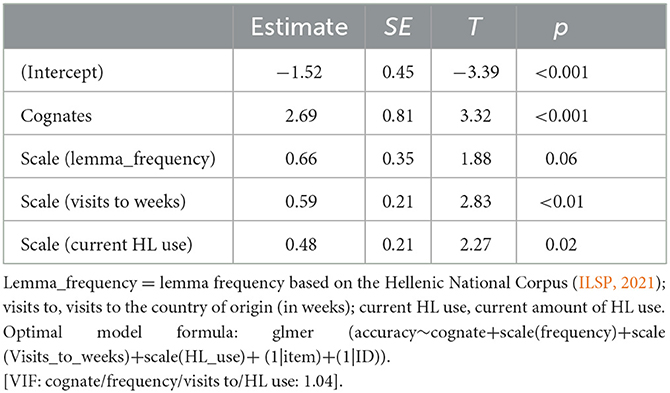

For vocabulary, the analysis revealed that the second and the mixed generations did not differ from each other in vocabulary size (E = −0.58, SE = 0.52, t = −0.95, p = 0.34), whereas the second (E = −1.65, SE = 0.53, t = −3.1, p < 0.01) generation and the mixed generations (E = −1.15, SE = 0.51, t = −2.22, p < 0.05) differed from the third. Cognate words had lower accuracy than non-cognate words (E = 2.68, SE = 0.81, t = 3.32, p < 0.001), and more frequent words elicited higher accuracy than words with lower frequency (E = 0.66, SE = 0.35, t = 1.89, p = 0.06). The inclusion of Age or SES did not significantly improve the model, and they were therefore excluded from the optimal model (fixed and random effects in optimal model formula: glmer (accuracy~Generation+cognate+scale (frequency) + (1|item) + (1|ID)). (VIF: Generation: 1; cognate/frequency: 1.04).

The optimal model for subject placement included the main effect of Generation, as the second and mixed generations did not differ from each other, whereas the third generation differed from both the second and the mixed generations (third vs. mixed: E = −2.86, SE = 0.96, t = −2.97, p < 0.01; Table 3). There was an interaction between Condition and the third generation, because it has significantly lower accuracy on the WF condition compared to the other two generations. For all groups of children, performance improved as a function of Age.5

3.3. Effect of proximal factors on vocabulary and syntax as a function of generation

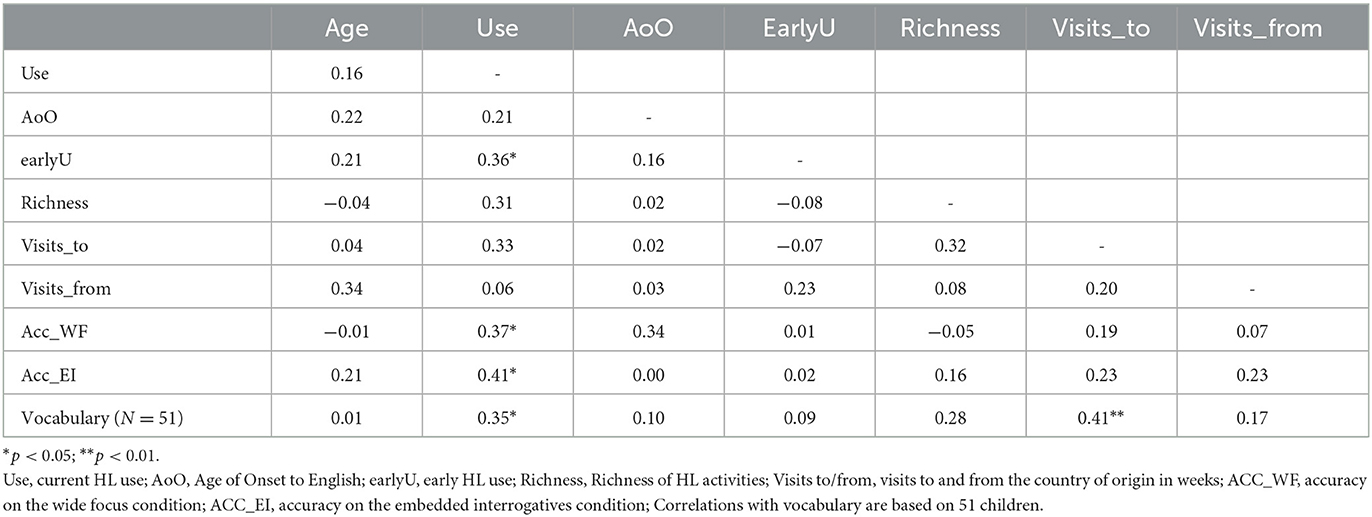

To examine how children's accuracy on the different tasks is modulated by proximal factors (RQ3), we first ran a correlation analysis to check for significant relationships between the background and the dependent variables. The results from the correlation analysis between the internal, the proximal factors and the linguistic measures are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Correlations between proximal variables and accuracy on the picture-naming and the subject placement tasks.

The correlation analysis revealed that children's current HL use and their visits to Greece had weak to moderate correlations with expressive vocabulary, embedded interrogatives, and wide focus structures.

3.3.1. Vocabulary

To investigate which combination of proximal variables affects children's accuracy as a function of generation (RQ3), we entered the proximal variables in Table 2 in a stepwise fashion into the model and checked for main effects when they were entered on their own and with interactions with Generations.6 The model with HL use and with visits to the homeland without Generation was the best fit to the data [Table 5; = 7.98, p < 0.05]. Given that Generation is a significant factor when proximal variables are not entered into the model (see also Table 3 under RQ1 for differences between the generations, when these variables are not included), this suggests that these two variables explain the variance driven by generational differences (and HL use also decreases as a function of Generation, as we show in Table 2). As one reviewer pointed out, one may assume that more visits to GR and more HL use would lead to a steeper increase in accuracy for non-cognates vs. cognates. Although this is a valid prediction, in our study, there was no interaction between cognate status and HL use (E = −0.19, SE = 0.15, p < 0.19) or visits to the homeland (E = −0.09, SE = 0.15, p = 0.52), and the model with the interaction was not significantly better than the model without [ = 2.23, p = 0.33]. For that reason, the simpler model without the interaction was retained.

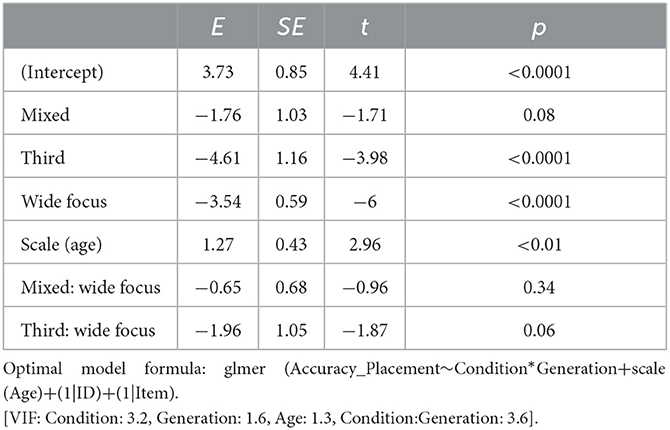

Table 5. Optimal model for accuracy on the picture-naming task as a function of HL use and visits to the homeland.

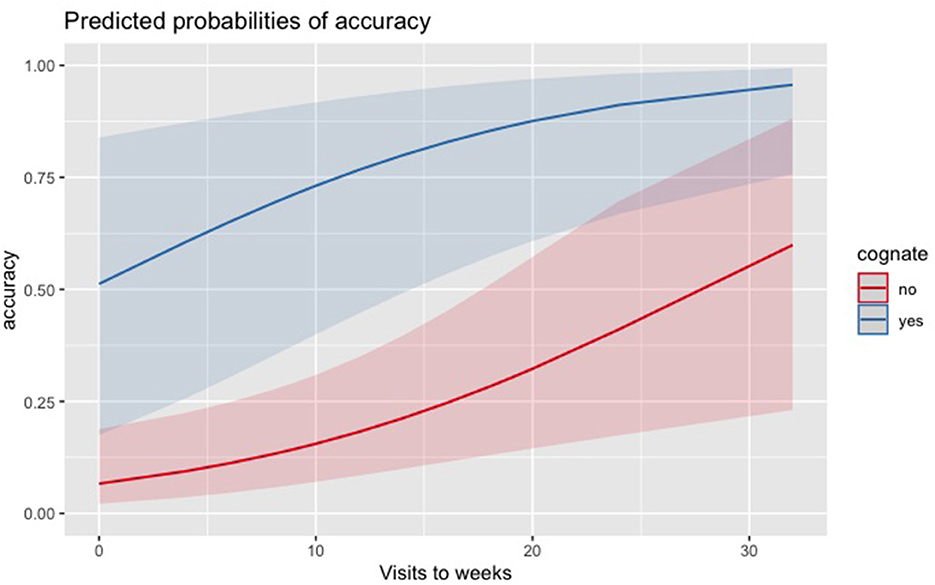

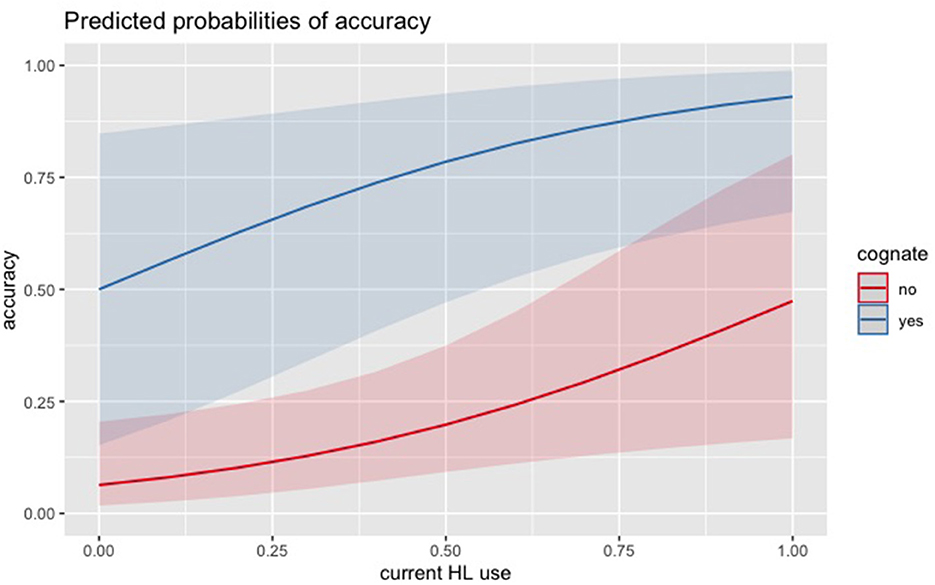

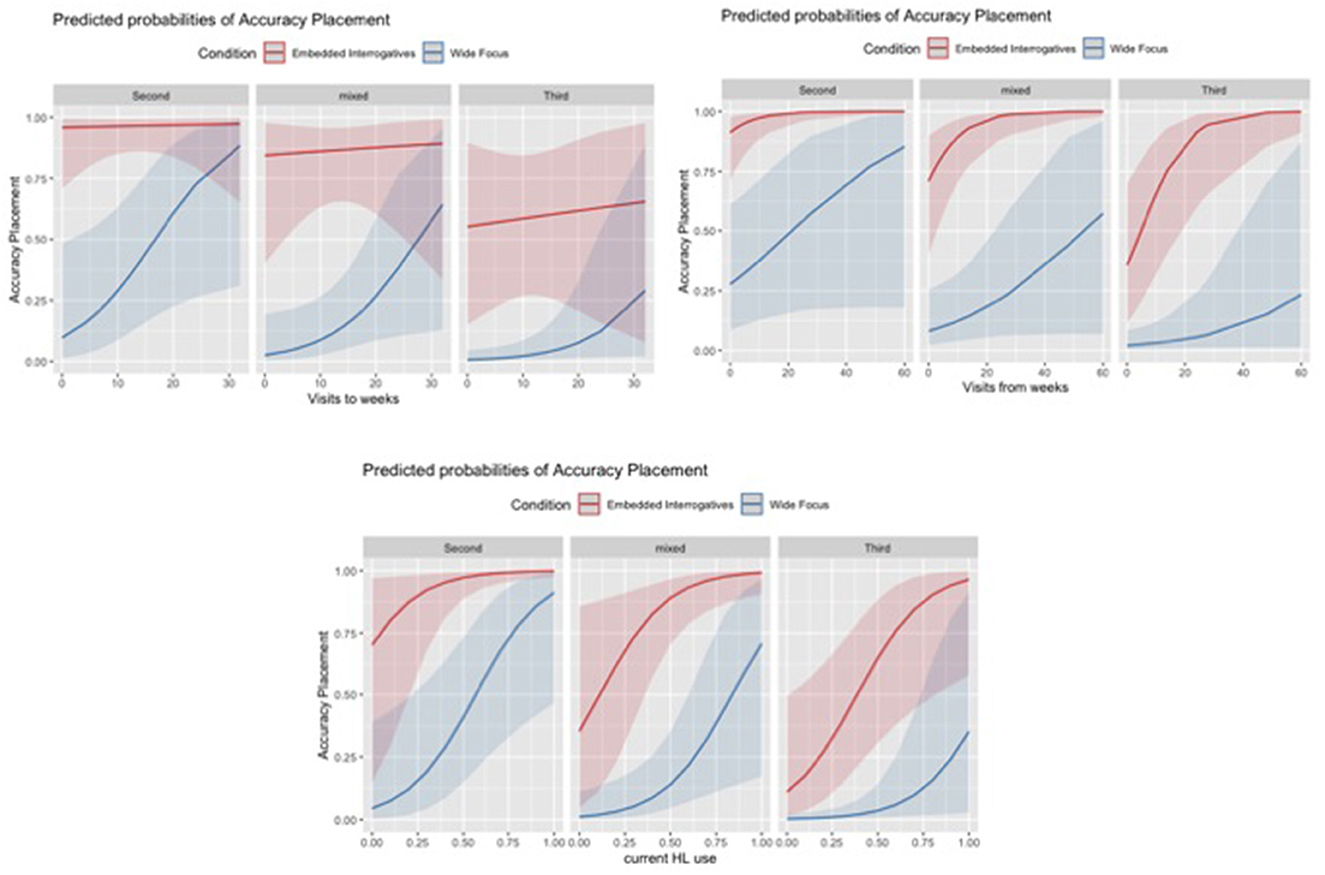

Figures 5, 6 present the relationship between heritage children's performance on the picture-naming task, their visits to Greece and their current HL use. These figures were generated based on the optimal model reported in Table 5 using sjPlot. According to the optimal model reported in Table 5, both variables (HL use and visits to the homeland) increase children's performance by the same amount (~½ a point), hence the visual overlap in Figures 5, 6 in the way the two variables modulate HL vocabulary accuracy. After checking for collinearity, the two variables were only weakly correlated (rho 0.33, Table 4) and the VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) of the individual variables in the model was low (cognate/frequency/Visits to HL in weeks/current_HL_use: 1.04).

Figure 5. Heritage children's accuracy on the vocabulary task as a function of the word's cognate status and visits to Greece.

Figure 6. Heritage children's accuracy on the vocabulary task as a function of the word's cognate status and amount of current HL use.

3.3.2. Subject placement

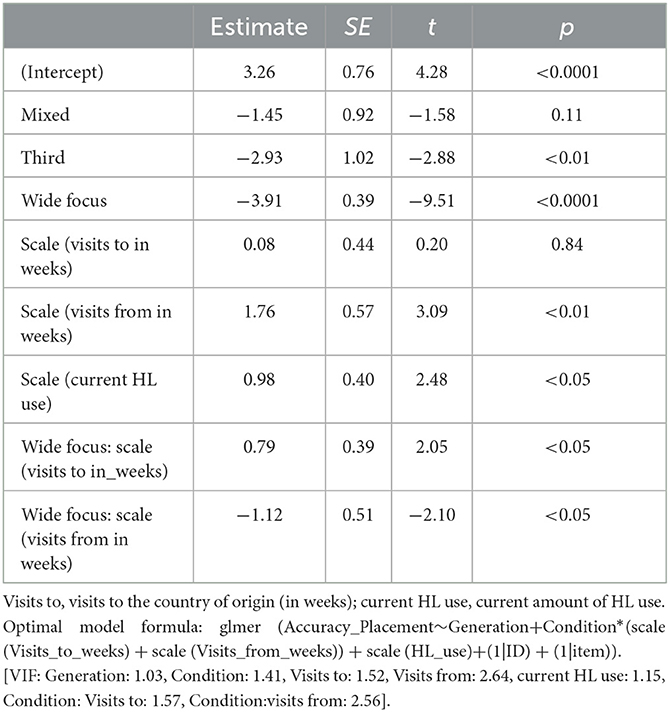

The fixed effects that were entered in the model as predictors for the two syntactic structures (EI and WF) were current amount of HL use, visits to and from the country of origin. Because we had established in our previous research (e.g., see Daskalaki et al., 2019) that the two conditions may be differentially affected by internal and proximal variables, we entered into the models the interactions between Condition (EI, WF) and the various continuous predictors. The model without the interaction with Generation did not differ from the one with the interaction, hence we decided to keep the simple model. The optimal model is presented in Table 6. This model included a simple main effect of current HL use, and interactions between the visits to and from Greece and Condition. The model with the interactions with visits was better than the one without [ = 9.45, p < 0.001].

Table 6. Optimal model for accuracy on the subject placement task as a function of the proximal variables and generation.

This model confirmed what had been established on the model without the proximal factors (Table 3). Namely that children's overall accuracy was lower for the third compared to the second and the mixed generations, and that the WF condition elicited significantly fewer VS responses compared to the EI condition. In terms of proximal factors, children's performance on both conditions improved with more HL use in the country of residence. However, there were interesting interactions between visits to and from the country of origin and the syntactic condition. Specifically, although visits of relatives from Greece generally facilitated children's performance, this was particularly the case for the EI and less for the WF condition. Conversely, visits to Greece boosted performance on the WF condition only, as the significant interaction between visits to Greece and Condition suggests. Figure 7 presents the effects of HL use, as well as visits to and from the country of origin.

Figure 7. Heritage children's accuracy on the subject placement task as a function of the child's generation, visits to and from the country of origin, and HL use in the country of residence.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we set out to investigate how proximal factors related to Greek heritage children's experiences with the HL may change as a function of the generation they belong to. We also examined how these factors may (differentially) affect HL outcomes. We investigated language domains that have been shown to be differentially affected by variable input: syntactically-conditioned structures, such as embedded interrogatives, which are less susceptible to cross-linguistic influence (CLI) from the societal language and input effects vs. discourse-conditioned structures (WF) and expressive vocabulary, which have been shown to be more vulnerable in heritage language acquisition (see Daskalaki et al., 2019, 2022 for the syntactic phenomena; Hulsen, 2000; Gordon and Meir, 2023 for lexical production). Ours is one of the few studies to investigate the effects of heritage speakers' generation not only on a range of different language domains but also on proximal factors associated with the country of residence or origin that have been shown to affect HL outcomes.

4.1. HL experience and abilities change as a function of the migration generation

In our study, we found that early HL use in the preschool years and the age in which exposure to the societal language (English AoO) started were similar across generations. Importantly, heritage children's exposure to the HL in the early (preschool) years remained high (~84% across generations). This indicates that heritage parents regardless of migration generation were keen to preserve the HL in the home, at least up until entry to formal mainstream education in the societal language, confirming that the timing of language shift and ultimately dominance in heritage children coincides with onset of formal school entry (Montrul, 2015). However, HL use practices during primary and later school years changed as a function of the child's generation, and significantly reduced by the third generation. Specifically, heritage children's amount of HL use at the time of testing, when children were in mainstream majority language education, and HL richness were significantly different in the case of the third generation compared with the second and the mixed generations, which did not differ from each other. This decrease in current HL use and richness as a function of generation aligns with findings from ethnographic, sociolinguistic, and other quantitative heritage studies that have independently documented that the minority language is used less across generation (e.g., Hulsen, 2000; Fishman, 2012; Montrul, 2015). Incidentally, children's visits to the country of origin also significantly differed between the third and the mixed generation, and there were also numerical differences between the third and the second generation. Fewer visits by third-generation children to the country of origin have been independently reported in ethnographic studies on diaspora tourism as a sign of decline in the strength of the transnational ties (Holsey, 2004), partly related to the language constraints imposed by the third-generation children's limited HL proficiency (Levitt and Waters, 2002).

In terms of linguistic abilities, we found an overall cross-generational decline, in line with existing cross-generational studies with adults (e.g., Silva-Corvalán, 1994) and children (Daskalaki et al., 2022). Specifically, the second and mixed generations did not differ from each other on subject placement in EI, and both generations differed from the third. Importantly, children's performance on the WF condition decreased as a function of generation, extending prior results reported by Daskalaki et al. (2020, 2022) to second-generation children. Differences between generations were also found in the lexical domain, with the third generation having significantly lower performance than the other two generations, who did not differ from each other. Cognate words had higher production accuracy across generations compared to non-cognate words, even though they had overall lower frequency compared to the HNC (Supplementary Table 2), and overall children performed better on higher frequency words across generations. These results are partly in line with the ones on the picture-naming production task by Hulsen (2000), who found that both the second- and the third-generation adult speakers had compromised expressive lexical skills and did not remember many of the words in the experiment compared to the first-generation speakers. In our study, we found that third-generation children's productive lexical skills were significantly compromised compared to the second and mixed generations.

Although it was not possible to directly compare accuracy between the lexical and the syntactic domains as they involved different tasks, it is clear that, all things being equal within generations, linguistic abilities do not develop simultaneously across all language domains (in line with results reported in Armon-Lotem et al., 2021; Gordon and Meir, 2023). For all generations, lexical abilities remained low, averaging at 50% for the second and mixed generation and at just over 25% for the third generation. This is in stark contrast with the generally high performance on the EI condition, which also changed less as a function of generation compared with the WF condition, where accuracy was below 50% across generations and almost at floor levels for the third generation. Our results show that syntactically-conditioned structures (VS in EI is the only grammatical option) are not only acquired better than other more pragmatically-conditioned structures (SV in WF is dispreferred but not ungrammatical), but also that they are less susceptible to language change across generations compared to structures at the syntax-discourse interface. The difference between the conditions was evidenced in the interaction we found between WF and the third-generation children who showed a significant drop in performance on that condition compared to the other two generations. Children's expressive vocabulary skills also seemed to be particularly sensitive to the restricted context within which HL acquisition takes place, as heritage children's overall low production accuracy across generations shows, and to ultimately decline as a function of generation. In the next section, we discuss the proximal factors that modulate performance on these linguistic domains.

4.2. What factors modulate HL performance across generations

One of the main contributions of our study was the examination of which proximal factors modulated HL outcomes on the two language domains that we targeted, and whether these effects changed as a function of generation. In our study, we did not find effects of AoO on HL outcomes in line with (Makrodimitris and Schulz, 2021; Torregrossa et al., 2023b), but in contrast to what has been reported in other previous studies (Albirini, 2018; Armon-Lotem et al., 2021). This lack of AoO effect could be possibly because of the small variance in children's AoO across generations (AoO <4 years was a participant selection criterion in our study). Importantly, this variable did not change as a function of generation, as all children were exposed to English upon (pre-)school entry. Correlation analyses also showed a weak relationship between HL richness and HL outcomes, but these did not survive the regression models (Jia and Paradis, 2015 for different results; but see Gollan et al., 2015). This was possibly because HL richness, operationalized as mean frequency of reading, watching/listening to TV/radio and interacting with Greek-speaking friends, was very low across the different generations in our study.

We now focus on the factors that explained most or part of the variance in our study. As mentioned, a novel aspect of our study is that it focuses not only on proximal factors in the country of residence but also on proximal factors related to the country of origin. We take the distinction between country of residence and country of origin to indicate significant increases not only in the amount of input that heritage children receive during these short-term visits to the home country, but importantly, significant changes in the quality of input they receive during these visits from native speakers who speak the variety in the country of origin and in the diversity of contexts within which the HL is spoken. In the context of the linguistic phenomena we targeted in the present study, we took visits to and from the country of origin to indicate contact with the variety where VS is highly preferred (see Daskalaki et al., 2019, 2020, 2022 for monolingual Greek speakers' performance on these structures). Overall, we expected sustained language use in the country of residence to predict HL development (Daskalaki et al., 2019; Chondrogianni and Schwartz, 2020). We also hypothesized that (re-)immersion in the variety spoken in the homeland could potentially boost heritage children's performance. For vocabulary, we hypothesized that re-immersion in the country of origin may provide heritage speakers with more opportunities to hear and produce words that may not be used as frequently in the country of residence due to the restricted contexts of use and speakers (Gollan et al., 2015; Casado et al., 2023). We also expected HL words that are used relatively infrequently in the country of residence for an extended period (i.e., while immersed in the English environment) and may not be as easily accessed during HL word production, may benefit from re-immersion in the country of origin (Baus et al., 2013) and may be boosted cumulatively after short re-exposure. For subject placement, we postulated that (re-)immersion in the country of origin may boost production of VS over SV structures, even in contexts that are vulnerable to cross-linguistic influence and more likely to give rise to SV (e.g., WF condition). Finally, we postulated that visits to Greece facilitate structures that are susceptible to input effects (e.g., vocabulary) and/or to CLI (e.g., WF) more than visits from Greece. This might be because, when relatives visit from Greece, the HL interaction continues to take place in the country of residence and under pressure of the majority societal language, and in more limited contexts compared to the ones in the country of origin.

Our results partly confirmed our predictions. For vocabulary, current HL use was a significant predictor when entered into the model separately. However, when visits to the country of origin was entered into the model, they explained more of the variance than HL use (Table 5). This might be because having more opportunities to hear and produce lexical items that are of low frequency and more likely to be used in contexts related to the country of origin or used outside the home context (e.g., trulos “dome”) triggered improved performance. We also found a general facilitation of visits on cognates and non-cognates, meaning that both word types benefited from naturalistic exposure to native and diverse input at the country of origin. The fact that the effect of HL use was reduced when visits were entered into the model, and, in turn, the effect of Generation was overtaken by the effect of HL use indicates the relationship between distal and proximal variables in our study, and how distal variables (in this case Generation) may affect proximal variables (HL use) to determine HL outcomes.

In the subject placement task, we found interesting interactions between visits to and from the country of origin and the two syntactic structures. Visits to the country of origin did not give rise to an overall facilitation effect, probably because performance on the EI was already high. However, there was an interaction with the WF condition, suggesting that it was the structure more susceptible to CLI that was facilitated by the exposure to the variety spoken in the country of origin. This means that contact with the variety where VS is highly preferred and produced by more speakers and in more diverse contexts may potentially boost VS production, even in the third generation where VS production is generally low, and SV is quite prominent.

The finding that frequent, short-term visits to the home country give rise to improved performance on lexical and syntactic domains is in line with two emerging areas of bilingualism research. Adult studies that examine how even short re-immersion in the home country can reverse (temporary) attrition effects (Chamorro et al., 2016; Genevska-Hanke, 2017; Casado et al., 2023), and studies with child and adult returnees (Köpke and Genevska-Hanke, 2018; Kubota et al., 2020; Flores and Snape, 2021) that show that long-term immersion can trigger heritage language reversal. In our study, we found that expressive vocabulary and the vulnerable interface condition (WF) benefited more by naturalistic exposure to an input where VS is highly frequent. Naturalistic exposure to a VS variety is particularly important in the context of our study because the syntactic structures that we targeted, and especially the WF condition, are not explicitly taught in heritage Greek classrooms (Montrul and Bowles, 2009; Potowski et al., 2009). However, given that the children in our study returned to their country of residence (US or Canada), where English is the dominant language, we can only hypothesize that any long-term benefits of these short-term visits gradually fade away. Although our study is the first to show that HL outcomes in heritage children are modulated by the length and frequency of these short-visits over time, more research is needed to fully understand the immediate and long-term effects of short-term visits on these vulnerable structures with child heritage speakers using designs similar to those found in studies with bilingual adults (Chamorro et al., 2016; Genevska-Hanke, 2017; Casado et al., 2023).

Interestingly, visits from the country of origin boosted performance on the subject placement task, but this was the case for the EI condition only. The interaction with the WF condition and the negative co-efficient suggests that visits from the country of residence did not suffice to counteract effects related to majority language use in the country of residence on HL learning.

Finally, although proximal variables either related to the country of origin or the country of residence decreased as a function of Generation, they continued to affect the three generations of children in similar ways, hence the lack of interaction between generation and proximal factors in our study. That is, lower HL use explained lower performance across the tasks and generations. As children's HL use and exposure to the HL via visits increased, their HL performance increased as well. However, it should be noted that similar levels of HL proximal factors (e.g., 50% HL use) did not give rise to the same levels of accuracy within each generation nor within the same language domain, as the effect plots indicate. The differential effects of proximal factors on language outcomes is in line with findings in the bilingualism literature that the relationship between proximal variables and linguistic performance is not a linear one (e.g., Chondrogianni and Marinis, 2011; Montrul, 2023; Paradis, 2023). Across generations, similar amounts of HL exposure or input did not necessarily lead to the same levels of performance, as shown especially in the case of the third generation. Furthermore, quantity and quality of input interact with grammatical knowledge to differentially affect language outcomes (Chondrogianni and Marinis, 2011; Montrul, 2023; Paradis, 2023). As Montrul (2023) puts it, the same amount and quality of input may be sufficient to develop some aspects of the grammar but not others. This is shown in our study both within the grammatical domain when comparing WF vs. EI structures, and with the juxtaposition of the different syntactic domains and children's expressive vocabulary.

4.3. Limitations and future research

In our study, the participants in the three generations differed in terms of age, with the third generation having older children than the other two generations. To ensure that differences among the generations was not due to differences in age, we entered age as a covariate in the models. Our results showed that age had a positive effect, at least in the syntactic domain. We were, thus, able to establish that performance on the different linguistic structures continues to improve as a function of age across generations (bar the WF condition in the third generation where performance was low overall; for more information about the effect of age in this population see Daskalaki et al., 2022). Additionally, due to a technical glitch, data from seven children were lost in the item analysis of the vocabulary task (the overall vocabulary scores were retained). Despite this, the general profile of the participants and the group comparisons did not change in comparison to the larger group of children in the syntax task, whose data was complete (Compare Table 1 in the main text and in the Supplementary material). The larger set of children in the syntax task also allowed us to have sufficient power in the sample given the design of the task and the number of conditions and items, and to compare these results to approximately the same number of children reported in our previous studies (Daskalaki et al., 2019, 2022). Furthermore, we took care to analyze the two tasks separately in this study, and no direct comparisons were made between the two tasks.

In terms of operationalization of the different variables, in the present study, we took short-term visits to and from the country of origin to be an accumulation of input quantity and quality of the variety spoken in the country of origin over short periods of time in the last 4 years prior to testing. This investigation of short-term re-immersion to the home country is different from existing studies with adult returnees or short re-immersion where they tested participants before and immediately after re-immersion (Chamorro et al., 2016; Genevska-Hanke, 2017; Casado et al., 2023). Another related issue is that we did not examine how the onset of the visits might relate to the child's chronological age in line with what has been pursued in studies with returnees controlled for the timing of testing after re-immersion (e.g., incubation period; Flores, 2020; Kubota et al., 2020, 2021). For example, it could the case that younger heritage children who are still in the process of acquiring the heritage language within a biologically more favorable window for language learning could benefit more from visits to the homeland compared to older children, who may have already stabilized in their HL learning, especially in relation to syntax. At the same time, one could also argue that older heritage children may be better at picking up structures, and especially vocabulary, than younger children due to the already larger vocabulary in their dominant language and stronger cognitive abilities than younger children (Golberg et al., 2008; Paradis, 2011). These are important questions for future studies to address. In the context of our study, given that short visits to and from the home country predicted HL outcomes, we can suggest that these short accumulations of input are important for HL development and, in conjunction with more institutional support and stronger HL social networks in the country of residence, could perhaps reverse or slow down HL loss. This is corroborated by our finding that even the third-generation children benefited from these short-term visits to the country of origin in their production of vulnerable structures (expressive vocabulary and wide focus).

Another point that merits future investigation that we have already raised in previous papers (Chondrogianni and Schwartz, 2020; Daskalaki et al., 2022) is how linguistic overlap and distance between the heritage and the dominant languages may change the nature of the results. As one reviser points out, it could be the case that heritage speakers' performance would be boosted if both languages used the same word order patterns as a means of marking information structure. Crosslinguistic studies with different pairs of languages that differ or overlap to different degrees in this respect would be more than welcome in this field of research.

Finally, given that our study was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, we did not consider at the time the extent to which digital technologies were used by participants, and how these may have affected HL outcomes. This is an important factor because studies have shown that the use of digital technologies in the home and school setting can make minority language learning much more dynamic and interactive, increasing the potential of intergenerational language transmission in heritage communities (e.g., Sun et al., 2023). Future studies could investigate this aspect of HL experience more and, especially, how it works in tandem with visits to the home country to boost HL development and transmission.

5. Concluding remarks

Despite the above limitations, our study is the first one to experimentally show the significance of native input in the country of origin for HL outcomes in the country of residence in three generations of HL children. Specifically, we showed that proximal factors related to HL use, especially those in later childhood, change as a function of the child's migration generation, and that these factors in turn influence HL outcomes, albeit differentially. A novel aspect of the study lies in that, although proximal factors related to the country of residence are important for HL development, short-term visits to and from the country of origin are also predictive of HL outcomes, at least for the structures that we tested in this context. These were structures that were less likely to be targeted in educational contexts (in the case of the two syntactic conditions) or frequently encountered in naturalistic settings in the country of residence (e.g., the low frequency words in the vocabulary task). These results reinforce current research findings with bilingual adults on the benefits of short-term re-immersion and extend them to child heritage language development contexts. Our study also raises important implications for the nature of the structured support needed through education and targeted interventions (Muāgututi'a, 2018), and the significance of broader social networks in the country of residence as a means to counteract a decline in the HL experience across heritage speaker generations.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: https://osf.io/fscgv/?view_only=5959931d27f74a099b91031d8df7bd71.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Graduate Center, City University of New York IRB; Department of Linguistics, University of Alberta IRB. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions