- Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Institute for Psychology, Writing Center, Paderborn University, Paderborn, Germany

Building on and methodologically extending conceptual metaphor theory, the article examines how personal agency as a discursively produced sociopsychological phenomenon can be studied in elicited metaphors through a discourse-analytical approach. More concretely, the study illustrates how early-career researchers experience and express their agency in research writing through personal metaphors of academic writing such as riding a roller coaster or baking a wedding cake. A two-step discursive analysis adapts Hopper and Thompson's multidimensional approach to linguistic transitivity to study agency in language. The analytical approach involves both an in-depth parametrized analysis of all metaphors in the sample and a qualitative cross-analysis of the data. The results show that the participants' metaphors reflect both nuanced personal experiences and cultural expectations of academic writing, the writer, and the text. This emphasizes that research writing is not only a highly subjective practice but also one that is socially and culturally influenced. The article argues that research on agency thus needs elaborate methodological tools to trace discursive and sociopsychological trajectories of complex socio-cognitive practices like academic writing. This has implications not only for the nexus of research writing, identity, and academic enculturation but also for other fields focusing on agency in language.

1 Introduction

Ah, the ups and downs of research writing! When researchers talk about their personal experience with academic writing in informal settings like conference coffee breaks or after meeting for a joint writing session, many compare their writing process to riding a roller coaster. The same image has been used by one of the participants in the present study. When asked to render her personal metaphor for academic writing, the early-career researcher completed the prompt “Academic writing is like …” like this:

A roller coaster ride. I associate academic writing with a multitude of activities and feelings that follow one another and that sometimes represent quite an up and down. From the idea for a text to the research, possibly the data generation, then the writing itself, the revision steps, possibly the cooperation with others, the presentation at congresses, the submission to journals, the waiting for feedback, the tension, the ups and downs of the feelings when [the paper is] being accepted or rejected, the feeling of being downhearted when receiving criticism, the reluctance and the agony when incorporating the criticism, the joy when it is done and one notices above all how the text becomes better and gains [from the criticism]. Finally, the euphoria when one reads one's article in print. (15)

This metaphorical description speaks about how different moments in the becoming of an academic text are characterized by a sequence of emotions evoked by the writer's own and other persons' stances toward each other, the evolving text, and the surrounding activities. One question that comes to mind when reading this personal description of an academic writing process is just how much power and freedom of action the speaking person appears to have as a writer. This leads to the more general questions that I address in this article: How can conceptualizations of agency in the context of a given sociopsychological activity be studied in personal metaphors? And, more specifically, focusing on academic writing as one such activity: How do early-career research writers experience agency in writing?

My focus is twofold, involving both a thematic and a methodological level. On a thematic level, the present study is concerned with personal experiences of agency in the exemplary area of academic writing. For researchers, especially in the early stages of their academic careers, academic writing is a key activity for professional success. It is the central means for communicating research findings to others and participating in disciplinary discourses. Research writing is subject to gatekeeping mechanisms and power relations in academic communities and regularly challenges the social rights and duties of writers. Characterized by asymmetric power relations and often happening under precarious circumstances, the writer-researchers' agency is challenged and contested in the process of their academic enculturation (Karsten, 2023; Muir and Solli, 2022). In this vein, academic writing is closely linked to personal development and creating not only text but also oneself as a scholar (Kamler and Thomson, 2014). The possibilities for identity development and learning in and through writing include what Lee (2010, p. 17) has called “being rhetorical,” that is, the quality of actively addressing one's work to a community of academic or professional peers. Thus, early-career academics' writing practices are an outstanding arena to study processes of social identity construction and, particularly, the sociopsychological phenomenon of agency.

On a methodological level, I present a discourse analytical approach to studying agency in elicited metaphors. In educational contexts, metaphor analysis is a widespread approach to studying sociopsychological phenomena involved in academic and professional development and disciplinary enculturation. While the literature on the doctoral journey emphasizes that academic writing is one of the key activities in which becoming a researcher unfolds (e.g., Barnacle and Dall'Alba, 2014; Kamler and Thomson, 2014), the number of metaphor studies dealing with academic writing and other literacy processes is relatively small and almost exclusively focuses on student writers. Like most metaphor analyses in educational studies, metaphor research on academic literacy practices generally builds on conceptual metaphor theory (CMT; seminally, Lakoff and Johnson, 1980), focusing on which metaphors are used to conceptualize the relevant processes. Extending this focus, I illustrate a more discourse analytical approach that attends to the sophisticated ways in which individual researchers (re)construct agency in and through metaphors. Zooming in on a finer-grained level of linguistic analysis gives insights into how exactly participants (re)construct their experience with a particular social practice, academic writing, through metaphor, addressing their felt power to act and, not least, their sense of self as research writers.

The article starts with a discussion of the theoretical node of agency in language. My focus lies on a discourse analytical perspective largely motivated by works in anthropological linguistics, which understands personal agency as a discursively produced sociopsychological phenomenon. A structured framework that has proven useful for an in-depth analysis of agency in discursive material are the holistic linguistic parameters of transitivity formulated by Hopper and Thompson (1980) presented subsequently. In the next step, the function and status of metaphor in relation to thought and action as formulated by CMT and successional research threads are discussed. For the present study, the issue of personal experience and its (re)construction in metaphorical utterances is central. To tackle this (re)construction, a discourse analytical approach is called for and subsequently spelled out in the context of a study of 24 early-career researchers' metaphors of academic writing. This study comprises both a parametrized analysis of all metaphors in the sample (consisting of a personal metaphor plus an explanatory text each) and findings from a recursive cross-analysis that revealed three thematic complexes in the sample: the varying degrees of writer's agency, the role of others for agency, and collective voices, cultures, and norms. The article closes with a discussion of the main results and the implications they have for understanding research writing, identity, and personal agency in academic enculturation, as well as with a methodological reflection on studying agency through metaphor, which extends beyond the thematic focus on academic writing.

2 Language and agency—A discourse analytical perspective

2.1 Agency as discursively (re)constructed

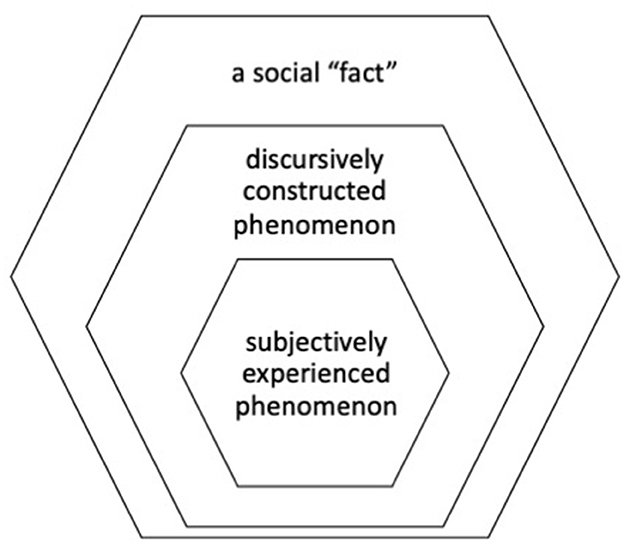

Agency is a sociocultural phenomenon. In the social sciences, there is no straightforward definition of agency but a tendency to understand agency as deliberate action and as making active decisions within social relations. Working from the mappings by Helfferich (2012) and Emirbayer and Mische (1998), three levels of understanding agency in the social sciences can be determined: agency seen as a social “fact,” agency seen as discursively constructed, and agency seen as a subjectively experienced phenomenon (see Figure 1).

The middle level of this field is central for a linguistically interested understanding of agency as a sociopsychological phenomenon, as it puts forward a conceptualization of agency as the discursively (re)constructed and socially assigned power to act. Accordingly, fields like linguistic anthropology claim that agency needs to be studied in relation to language as social action, stressing “how important it is for scholars interested in agency to look closely at language and linguistic form” (Ahearn, 2001, p. 109). In the following, I rely on a distinction introduced by Duranti (2005):

[T]here are two basic dimensions of agency in language: performance and encoding. … [T]he two dimensions are in fact mutually constitutive, that is, it is usually the case that performance—the enacting of agency, its coming into being—relies on and simultaneously affects the encoding—how human action is depicted through linguistic means. Conversely, encoding always serves performative functions, albeit in different ways and with varying degrees of effectiveness. By describing agentive relationships among different entities (e.g., participants in a speech event, characters in a story) and affective and epistemic stances toward individuals and events, speakers routinely participate in the construction of certain types of beings, including moral types, and certain types of social realities in which those beings can exist and make sense of each other's actions. (Duranti, 2005, p. 454–55)

Analyses of agency in language can thus focus more on the performative aspects of agency: how speakers enact their social capacity to act through the way they talk. Or they can focus more on the way in which speakers position themselves and others to have a certain degree of agency, that is, how they (re)present actions and relations in and through their utterances. These tendencies involved in agency as a discursive phenomenon also transcend into the psychological level of experiencing agency and the sociological level of “having” agency. Due to my thematic focus, my focus lies more on questions of encoding—specifically on how early-career researchers (re)present agency in academic writing in and through their personal metaphors. However, I also draw on aspects of performance in terms of how the early-career writers enact agency through the way they voice and address their personal metaphors.

2.2 Studying agency through Hopper and Thompson's parameters of transitivity

Focusing on agency in language draws attention to how exactly an event (be it real or imaginary) and its entities are discursively (re)constructed: what action qualities the constructed event exhibits and how the characteristics of and relations between participants of the event are depicted. Duranti (2005, p. 459–60) argues that all languages have ways of representing agency and that there are several possibilities in each language to both encode or perform and mitigate agency. Hopper and Thompson (1980) formulated an analytical framework concerned with linguistic transitivity that offers an exceptionally rich and detailed account of linguistic strategies to encode and mitigate agency in the morphosyntactic and semantic-pragmatic domain. In traditional grammar, transitivity was initially understood primarily as a syntactic structure comprising a subject of action and an object of action (usually marked in the nominative and accusative case; see Kittilä, 2002, 2010). A simple example is the sentence “The girl was singing a beautiful song,” which is understood as a transitive clause in traditional grammar with “the girl” being the subject and “a beautiful song” the object, compared to the sentence “The girl was singing beautifully,” where there is no grammatical object; therefore, the clause is considered intransitive. Whereas traditional grammar focuses on the grammatical structures of the respective clause and not on its discursive meaning, semantic and pragmatic definitions of transitivity have become more widespread in the past decades (Kittilä, 2010). Until today, Hopper and Thompson's parametrized scheme to determine the transitivity of an utterance, which combines syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic aspects in its understanding of transitivity, is the most important multidimensional approach to analyzing the transitivity of linguistic utterances. It conceptualizes how the transitivity of an utterance provides fundamental information about the effectiveness of an event as it is linguistically constructed in terms of the amount of energy that is transferred from an actor to an object of action.

Hopper and Thompson's scheme is usually used to analyze how different languages construct transitive semantics linguistically and to identify patterns across languages. Their work also provides a promising basis for metaphor studies from a cognitive-linguistically and discursively oriented perspective (Scharlau et al., 2019, 2021; Karsten et al., 2022).

Hopper and Thompson (1980) list 10 parameters to determine the transitivity of an utterance:

1. Participants: subject (A) and 0-n objects (O, IO)

2. Kinesis: event or state

3. Aspect: telic or non-telic

4. Punctuality: punctual or extended

5. Volitionality: deliberately or not

6. Affirmation: affirmative or negated

7. Mode: realis or irrealis

8. Agency of A: human or other living being or thing

9. Affectedness of O: energy transferred or not

10. Individuation of O: singular or mass noun

These parameters, described in more detail in Section 4.2, refer to the action itself as it is constructed in the utterance, the subject or agent performing the action, or the object or patient of the action. Each parameter is to be thought of as a continuum with two poles, one of which is associated with a low degree of transitivity and the other with a high degree of transitivity. The respective ratings of each parameter are usually summed up to determine the overall transitivity of the utterance. In the present study, I use Hopper and Thompson's scheme to perform an in-depth discursive analysis of the action qualities of personal metaphorical conceptualizations of research writing as they are produced by individual members of a social community, extending previous studies on academic writing and reading, which work based on generalized transitivity features of conceptual metaphors found in a larger body of material (Scharlau et al., 2019, 2021). This means that I take into account how the syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic qualities of each individual linguistic construction are deployed—consciously or unconsciously—to construct the characteristics of an event and thus understand how the personal experience of agency is depicted by the individual participants.

Before presenting my empirical study and illustrating how agency constructions can be studied through transitivity analysis at an individual level, it is helpful to take a theoretical and methodological look at how metaphor analysis typically has been used to study sociopsychological phenomena like professional identity development, agency, and learning.

3 Metaphor as a window to personal experience?

3.1 Conceptual metaphor theory

CMT, introduced by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson in 1980, has been seminal in conceptualizing metaphor not as a mere rhetorical or poetic device but as a central mechanism of human thought and language. CMT holds that the use of metaphors is a common everyday procedure that helps people make sense of complex and more abstract states or events (target domain) in terms of simpler and experience-based states or events (source domain). As we have seen, research writing can be conceptualized as, for example, A ROLLER-COASTER RIDE. However, it can also be conceptualized as the CONSTRUCTION OF A BUILDING as in the following personal metaphor from my sample:

The construction of a building.

– For both, one starts with a scaffold [framework] (outline).

– [One] completes individual building blocks little by little.

– One needs a plan/idea of the result.

– At the end one makes the finishing touches and embellishes. …

– When it's done, one wants to show it off to other people and be proud of it. … (2)

Depending on the choice of source domain, certain characteristics of the target domain are highlighted (e.g., the processual nature and emotional oscillations vs. the step-by-step advancement and working toward a final result), while other characteristics of the target domain are hidden (e.g., neither of the two metaphors presented so far particularly refers to the role that other authors' texts play in writing).

As part of a cognitive linguistic framework, CMT holds that metaphors work on a conceptual level. According to CMT, metaphor is not a punctual discursive strategy of individual speakers but structures all thinking, speaking, and acting—mostly in an integral, matter-of-course fashion that goes largely unnoticed by speakers. Lakoff and Johnson (1980) argue that conventionalized linguistic expressions such as “I've never won an argument with him” and “You disagree? Okay, shoot!” reflect relatively stable conceptual metaphors that structure human thought (here: ARGUMENT IS WAR; cf. Lakoff and Johnson, 1980, p. 4). A central tenet of CMT is that conceptual metaphors are based on primary metaphors directly tied to human experience (Grady, 1997, 2005; Lakoff and Johnson, 1980). According to the primary metaphor theory, conceptual metaphors like GOOD IS UP rely on the basic embodied experiences of individuals in the physical world. Gibbs (2003, p. 2) formulates what he calls the “embodiment premise” as follows:

People's subjective, felt experiences of their bodies in action provides part of the fundamental grounding for language and thought. … We must not assume cognition to be purely internal, symbolic, computational, and disembodied, but seek out the gross and detailed ways that language and thought are inextricably shaped by embodied action.

While traditional CMT works from an implied generality of human experience due to humans' specific embodied ways of being in the world, more recent cognition-oriented approaches in metaphor research focus more specifically on the particular interaction of co-actors and their contexts as a source of metaphoricity (e.g., Jensen and Greve, 2019). Similarly, discourse-oriented and usage-based approaches in metaphor research criticize that the foundational accounts of CMT study conceptual metaphors in a traditional linguistic fashion through analyzing decontextualized examples and relying on the introspection of linguists, such as in the examples given earlier (Hampe, 2017). As one proponent of this critique puts it, “[t]raditional researchers in conceptual metaphor theory fail to notice some essential aspects of metaphor and cannot account for phenomena that can only be accounted for if we investigate metaphors in real discourse” (Kövecses, 2010, p. 664).

3.2 Studying sociopsychological phenomena through metaphor: identity, learning, and literacy

From early on, CMT has investigated the metaphorical conceptualization of typical psychological phenomena, for example, emotions (Kövecses, 2000), the self (Lakoff and Johnson, 1999), morality (Johnson, 1993), or psychoanalytic concepts (Borbely, 2004; see Gibbs, 2011, p. 533). Therefore, it is not surprising that metaphor analysis has become a widespread methodological tool in studies of educational practice, the field of teacher training being an especially rich area for metaphor studies (see Saban, 2006). Many studies in this field focus on metaphorical conceptualizations of teaching and learning and how they change during professional development and academic enculturation (e.g., Leavy et al., 2007; Martinez et al., 2001; Wegner and Nückles, 2015a,b; Wegner et al., 2020). Some of these studies specifically attend to the sociopsychological processes of professional identity development and learning and how they present themselves by or can be fostered through metaphors. Beauchamp and Thomas (2009) highlight several studies that focus on teachers' professional identity and its development through metaphor. Thomas and Beauchamp's (2011) own study compared new teachers' metaphors they used to describe their professional identities immediately following graduation with those in their first year of teaching. Their findings suggest that whereas new teachers first see themselves as ready for their teaching tasks, they later struggle to develop a professional identity. Hunt's (2006) reflective study highlights how focusing on metaphors in reflective practice can serve as a tool to accomplish the passage from more intuitive preprofessional knowledge into professional practice. In these contexts, metaphors are often used to examine those “aspects of identity that are difficult to articulate” (Thomas and Beauchamp, 2011, p. 763). The reported exemplary studies from the field of teacher training and higher education teaching and learning thus bear a resemblance to my present research insofar as the development of professional or academic identity is interwoven with the experience and (re)construction of personal agency in the respective community and its central practices as, for example, Lea and Street (2006) and Lillis (2003) have argued for thes development of academic literacies. An explicit focus on agency in the area of metaphor research in the field of teacher training can be found in the approach of Beauchamp and Thomas (2009), when they argue that “[w]hat may result from a teacher's realization of his or her identity, in performance within teaching contexts, is a sense of agency, of empowerment to move ideas forward, to reach goals or even to transform the context. It is apparent that a heightened awareness of one's identity may lead to a strong sense of agency” (p. 183).

In the context of metaphor analysis as a way to study professional development and enculturation, there is a growing field of studies on students' and teachers' metaphors of academic literacy practices, reviewed largely by Wan and Turner (2018). Analyses focusing on metaphors of academic literacy practice include higher education reading, writing, or both. Armstrong (2008) investigated first-year college students' conceptualizations of academic literacy and how those conceptualizations changed over the course of their initial college literacy experience in a developmental reading and writing class. She worked on the basis of both spontaneously produced metaphorical expressions and elicited metaphors. Paulson and Armstrong (2011) explored the metaphors related to reading, writing, and learning that students enrolled in a university reading and writing course produced in response to prompts similar to those used in the present study. Wan (2015) worked with metaphors elicited in group discussions of English as a second language graduate students on their writing beliefs and the relationship between academic writing and critical thinking. More recently, Rismondo and Unterpertinger (2021) investigated university students' understanding of the role knowledge plays in their writing processes in an exploratory analysis of semistructured focus group interviews.

Even though the personally felt and socially assigned power to act plays a central role in a social identity construction, only a few metaphor studies on higher education reading or writing deal with issues of agency in an explicit fashion. Exceptions are the studies by Paulson and Theado (2015), Scharlau et al. (2019), Scharlau et al. (2021), and Karsten et al. (2022). Paulson and Theado (2015) hold that agency is a central aspect of students' identity and learning, especially in self-regulated learning. They also argue that higher education instructors play a key role in shaping their students' conceptualizations through their “teacher-talk” and, specifically, the metaphors used in this classroom talk. Scharlau and colleagues' studies on university students' conceptual metaphors of writing (Scharlau et al., 2021) and reading (Scharlau et al., 2019) interpret Hopper and Thompson's model of transitivity in terms of writer's agency (Karsten et al., 2022), focusing on the question of how writers or readers were represented as actors (or non-actors) through the different conceptual metaphors in the respective samples.

Overall, there is a striking sparsity of metaphor research with more advanced students or even early-career research writers—if not in the role of university teachers. One notable exception is the study of Simpson (2009), who studied the metaphors for academic writing of seven postgraduate students with a special focus on how these students see themselves as writers and thus on how personal metaphors of academic writing give “insight into writers' writer-identities” (Simpson, 2009, p. 193). He highlights that writer identity is informed by higher education writing as a social practice with a dominant epistemological and ideological framework.

The majority of the cited studies were carried out as thematic analyses working on the level of generalized conceptual metaphors, many of them relying on the analytical approach described by Cameron and Low (1999) and Wan and Turner (2018):

The essence of the approach is a systematic generalization of the informants' metaphorical language to infer underlying conceptual metaphors and ultimately enabling researchers to gain insight into participants' thought patterns and understandings of a given topic. This analytical procedure contains three steps: (a) collecting informants' metaphorical linguistic expression (MLE) of the topic; (b) generalizing from MLEs to the conceptual metaphors they exemplify and (c) using the results to suggest the understanding or thought patterns which construct or constrain people's beliefs or actions (see Cameron and Low, 1999, p. 8). (Wan and Turner, 2018, p. 302)

While this approach is coherent with traditional CMT methodology as it has been described earlier, it can be criticized for the same shortcoming of disregarding situated aspects of metaphorical conceptualizations of a given sociopsychological practice. This gave rise to my interest in early-career researchers' individual encodings and performances of agency in writing through metaphor.

3.3 Personal experience in metaphors: the need for a discourse analytical lens

As argued earlier, CMT works from an implied generality of the human experience of being in the world and tends to see linguistic expression as a “symptom” of and “window” to conceptual thought. When metaphor-based studies in psychology or education elicit metaphors from a group of subjects (e.g., students or teachers) and then analyze these metaphors only or primarily on the conceptual level, these analyses work from the same implicit assumption of universality.

Recent trends in metaphor research suggest that the stable interindividual linguistic expressions that CMT has interpreted as evidence for conceptual metaphor can also be interpreted in terms of shared discursive practices in cultural communities (Hampe, 2017). Single situated discourse events rely heavily on more momentary and often interpersonal metaphorical mappings next to the more stable typical metaphors from socially shared practices. This is in line with more recent usage-based accounts in linguistics (cf., e.g., Bybee, 2010; Langacker, 2000; Tomasello, 2003), which stress that culture—in terms of both experiences of the social lived-in world and culturally typical ways of speaking about this world—influences how individuals conceptualize a state or event (e.g., Sinha and Jensen de Lopez, 2000; for conceptual metaphor: Caballero and Ibarretxe-Antuñano, 2009; Ibarretxe-Antuñano, 2013). Regarding metaphoricity, this view is backed up by several empirical studies. The various research examples rendered by Hampe (2017, p. 6) nicely illustrate that source domains for metaphorical mapping are much more variegated between different discourse communities than CMT suggests and that contextual factors of the usage situation influence the choice of source domains, making metaphorical mapping a much more context-bound, personal, and less static phenomenon than suggested by CMT.

The personal experience of agency, just as the experience of other sociopsychological phenomena, is a multifaceted phenomenon deeply dependent not only on “direct” interpersonal relations but also on shared discursive ways of encoding and performing the respective phenomenon. The positioning of oneself and others in and through language is the central mechanism that informs subjective experiences of sociopsychological phenomena such as agency in sociocultural contexts. This will be mirrored in metaphorical mappings that involve senses of agency as well.

4 A study of early-career researchers' metaphors of academic writing

4.1 Participants, material, and analytical procedure

The corpus I analyze here contains 24 metaphors plus explanatory texts produced by 24 early-career academics from two German universities. The data was collected at the end of two writing group events for women early-career researchers, one organized in person in September 2017 and one held in a synchronous digital form in September 2020, each lasting several days. Data collection was limited to these groups to allow for a first exploratory analysis of this specific participant group. The writing groups provided the participants with extended time for working on their academic writing projects, interspersed with short inputs, writing prompts, and reflection tasks. This means that issues of academic enculturation and the participants' personal development as research writers were already in focus. At the same time, there was no extended input regarding “good” writing practices or strategies to produce successful academic texts, which could have influenced the metaphorical conceptualizations too much. Because of the exploratory nature of the study, the corpus was not based on any further theoretically or methodologically informed sampling strategies. Participation in the metaphor study was voluntary. Because I was part of the organization team of the writing groups, demographic information was only collected for the participants of these groups, not for the individual study participants to facilitate an unbiased and anonymous collection of the personal metaphors. There were 14 participants in the in-person writing group in 2017 (of whom 11 contributed a personal metaphor) and 24 participants in the digital writing group in 2020 (of whom 13 participated in the online collection of personal metaphors). All writing group participants self-identified as women. In both groups, roughly half of the participants had an institutional or topic-related affiliation with the humanities, while the other half came from the social and natural sciences and mathematical or technical disciplines. Many of the participants were doing research in interdisciplinary projects. The groups consisted of both PhD and postdoctoral researchers (three postdoctoral researchers in the in-person group and four in the digital group). All participants had a native or near-native language proficiency in German (two speakers of German as a second language in the in-person writing group and three speakers of German as a second language in the digital group).

To collect the study data, participants were asked to write down their personal metaphors of academic writing as well as a short text (usually comprising several sentences) that explained the metaphor. Participants received the following prompts:

1. Academic writing is like ...

2. In what way is academic writing like the metaphor you have chosen?

The participants' answers were collected in German anonymously in a pen-and-paper version (for the in-person group) and via an online survey system (for the digital writing group). All metaphors and explanatory texts were translated into English for publication (for the complete corpus in both languages, see the Supplementary material to this article). The English versions are translated close to the originals to preserve as much of the original wording and grammar as possible, at times assisted by comments on the specific German formulation in square brackets.

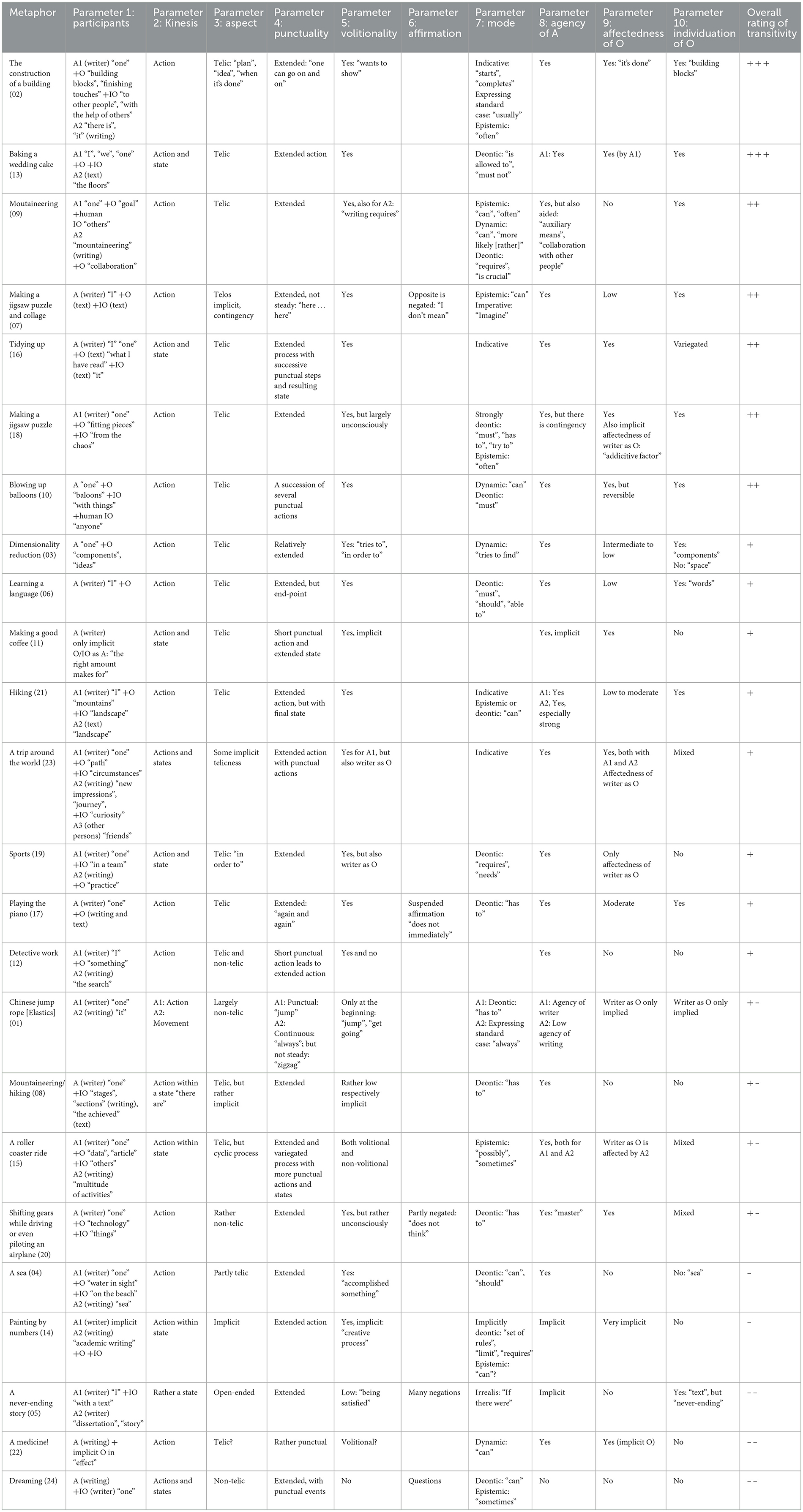

Due to the small corpus size and the theory-based discursive focus of the analysis, a purely qualitative approach was chosen. Analysis was done in several steps. First, I carried out a systematic transitivity analysis for all 24 texts, drawing on the parameters of Hopper and Thompson (1980). Parameters were determined manually, analyzing the metaphorical texts piece by piece. Due to the exploratory character of the analysis and the move toward a more discursive rather than thematic analysis, no intra- or interrater reliability was assessed.1 In this first analytical step, the metaphors were also rated by overall transitivity bearing on the scrutinized coding by transitivity parameters. Table 1 renders the results of the systematic transitivity analysis, including all metaphors listed from high to low overall transitivity, as well as the detailed ratings for the single parameters. This first step was followed by an in-depth qualitative characterization of the writing scenes. In this second step, I wrote individual memos in the style of thick descriptions for all the texts based on my close and recursive reading. I focused specifically on questions of voice, positioning, and addressivity, that is, how strongly a text appeared to be directed at a reader or audience. A third step was the recursive cross-analysis of the whole sample. I reread the material several times and searched for thematic and structural patterns across metaphors concerning the encodings and performances of agency. The findings from this step were systematized into three topic areas (degrees of agency of the writer, the role of others, and collective voices, cultures, and norms). The results from this recursive cross-analysis are presented in Section 4.3.

4.2 Results of the transitivity analysis

As indicated, I used the parametrized transitivity scheme by Hopper and Thompson (1980) to perform an in-depth analysis of the personal experience of agency in research writing, focusing in detail on the discursive encoding and performance of action qualities in the individual metaphorical conceptualizations of academic writing. Table 1 renders the complete results of this analysis for all 24 metaphors and explanatory texts in the sample, analyzing each metaphor parameter by parameter, ordered from high to low overall transitivity. In the following, I illustrate how this analysis was done and give examples to make my analytical findings transparent.

4.2.1 Participants

This first parameter comprises the agent or subject (A) of an activity and any number of direct (O) or indirect objects (IO) the activity might have. Constructions with A and O imply a stronger degree of transitivity than clauses with A and IO but no O, whereas constructions with only an A point toward an intransitive conceptualization of a scene. In the analysis, I focused specifically on (re)constructions of the writer, of writing (in terms of the writing process), and of the text (in terms of the product of writing) and the semantic roles they were assigned. Consider the following example:

Making a jigsaw puzzle. One must try—from the chaos of ideas, thoughts, insights, representations, problems and questions from the mountains of different literature and what goes through one's head (often of unclear origin)—to find or produce and assemble fitting pieces in writing/through writing. (18)

Here, there is a not further specified impersonal agent (A) “one” that is associated with the writer, and the direct object (O) “fitting pieces,” associated with parts of the text, which need to be taken from an assemblage of indirect objects (IO) “from the chaos of ideas, thoughts, insights …” that, in turn, can be interpreted as the multitude of information or ideas that the writer chooses from. In terms of grammatical participants, transitivity is rather high in this example.

4.2.2 Kinesis

The second parameter determines whether the scene in question is conceptualized as an event, activity, or movement or as a state. Events are rather transitive, whereas states are intransitive. The following example exhibits both cases:

Tidying up. It is like tidying up, because I arrange what I have read and put it in a new order that is logical for me. After that, everything is beautiful and one likes to look at it. (16)

In the first sentence, “because I arrange what I have read and put it in a new order” clearly involves activity and movement, and kinesis is relatively high. In turn, the second sentence, “everything is beautiful,” describes a state with no kinesis.

4.2.3 Aspect

The aspect of a scene determines how much an activity is oriented toward an endpoint. Telic actions that are completed and have a clear endpoint exhibit stronger transitivity than atelic actions. In the following example, there are several indicators for telicity:

The construction of a building. … [One] completes individual building blocks little by little. … One needs a plan/idea of the result. … When it's done, one wants to show it off to other people & be proud of it. (02)

Here, it becomes obvious that transitivity is as much a matter of semantics as it is of syntax. In the example, telicity is implied not so much in the verb forms as in the semantics of “completes,” “a plan/idea of the result,” and “When it's done.”

4.2.4 Punctuality

This fourth parameter distinguishes between punctual actions with no transitional phase between inception and completion and extended, ongoing actions. Punctual actions hint toward a higher degree of transitivity than extended actions. The following example exhibits both punctual and non-punctual aspects:

Detective work. I observe something that astonishes me and makes me wonder “Why is that [actually the case]?”, and then the search for the answer already begins. (12)

The first part of the example presents several punctual events in succession: “I observe something,” “[it] astonishes me,” “[it] makes me wonder.” The latter part, “the search for the answer already begins,” in turn, depicts the initial phase of an ongoing action that is not completed.

4.2.5 Volitionality

The fifth parameter makes a distinction between deliberate, volitional actions, which typically imply a higher degree of transitivity because the agent is conceptualized to be acting on purpose, and unintentional actions. The following example constructs images of more and less volitional actions:

A trip around the world. … influenced by … new impressions, one adapts the further journey again and again to the new circumstances/the new self [new I], constantly redesigns the path/destinations. The journey is stimulating and exciting. (23)

The clause “one adapts the further journey again and again” is a volitional activity of the writing agent, whereas in the clause “The journey is stimulating and exciting,” the writer is implied as a receiver of impressions that the writing journey gives yet by means of semantics not in a volitional manner because “the journey” is not an animated participant acting purposefully.

4.2.6 Affirmation

This parameter delineates affirmative, more transitive conceptualizations from negated, less transitive ones. An interesting example in the present material produces an intermediate effect:

Playing the piano. Like playing the piano, one has to learn academic writing. … One does not immediately write the ‘perfect' text (the performing of the piano piece at a concert), but first ‘practices' and revises the text again and again until one has the final product (the concert performance, so to say). … (17)

The construction “One does not immediately write the ‘perfect' text” suspends the general affirmation that, in the end, the “concert performance” or “final product” can be reached. Thus, the transitivity it exhibits is weaker than, for example, the one produced by the last clause, “one has the final product.”

4.2.7 Mode

For their seventh parameter, Hopper and Thompson only differentiate between realis and irrealis. However, for analyzing writers' agency, distinguishing between different qualities both within the realis (marked by, e.g., sometimes, often, always) and the irrealis (modality in the narrower sense) is advised. For the latter case, the differentiation between deontic (expressing grades of permission or obligation), dynamic (expressing grades of ability), and epistemic (expressing the speaker's estimation of likelihood) modality can serve as an analytical point of reference (Traugott, 2011). The following example displays several different modal qualities:

Mountaineering. … Spontaneously, I associate (academic) writing with mountaineering. One has a goal in front of oneself, but often one can only reach it “with difficulty” and with a lot of effort in several stages. … Mountaineering is a discipline that requires collaboration; similarly, writing often requires collaboration. Through support from others (e.g., writing consultation, exchanges among colleagues about contents [topics], etc.) one is more likely to reach [rather reaches] one's goal. … the use of auxiliary means [aids, tools] is crucial. … (09)

There are several markers for epistemic modality (“can,” “often”), dynamic modality (“can,” “more likely to reach [rather reaches]”), and deontic modality (“requires,” “is crucial”) in this example. These markers all express the conditioned nature of the respective action, which is thus less strongly conceptualized as real or happening “in any case”. The effect is a less transitive impression of the scenes in question than if they were rendered without modal markers.

4.2.8 Agency of A

This parameter makes a distinction between humans or other living beings as actors and things as actors. Hopper and Thompson use the notion of agency as a more or less pronounced inherent characteristic of actors. Animated agents are considered to possess more agency and thus exhibit a stronger transitive effect on the scene than inanimate agents. Consider the first metaphor in the present sample:

Chinese jump rope [Elastics].... because sometimes one just has to “jump” (i.e. get going, even if one is not perfectly prepared) & because it goes always back/forth or to and fro (zigzag). (01)

There is a clear difference in transitivity between the first clause, “one just has to ‘jump',” involving a human actor, and the second clause, “it goes always back/forth …,” where the activity itself is rendered as a syntactic agent.

4.2.9 Affectedness of O

The two last parameters, finally, put the object of the action, the patient, in focus. Affectedness of O describes whether energy is transferred to the object by an action or not. In the former case, the depicted scene is more transitive than in the latter case. Consider the example “Writing is like blowing up balloons,” where the activity is (re)constructed as transferring energy and affecting the objects, but in a reversible fashion:

Blowing up balloons. … one has to expand it and sort of “blow it up” to get the finished product. One has to surround it with more and more [things] so that, in the end, one gets a finished “big” product. But sometimes one has to let some of the air out again. … (10)

Expanding a balloon/text affects and changes the object, but these changes are depicted as reversible because it is also possible to “let some of the air out again” without affecting the balloon/text too much. Transitivity is thus quite high in this example in terms of affectedness of O but not maximal.

4.2.10 Individuation of O

The last parameter concerns the degree to which an action's object or patient is concrete, singular, countable, definite, animate, or even human vs. abstract, plural, a mass, non-referential, or inanimate. Individuated objects of the first sort are more subjected to transitive actions than objects of the non-individuated latter sort. An example:

Dimensionality reduction, i.e. in a mathematical sense the projection of high dimensional vector spaces into low dimensional vector spaces. One tries to find in the high-dimensional space of all knowledge and all previous studies the components that are relevant for one's own research project, in order to end up with a low-dimensional space that is clear [lit. “overviewish”] enough to grasp the topic, and to finally put one's own ideas into a one-dimensional form, the text. (03)

This metaphor exhibits both individuated objects (“components”) and non-individuated ones (“space”). However, because even the individuated objects in this example are abstract, overall transitivity in terms of an individuation of O is rather low.

4.3 Results from the recursive cross-analysis

4.3.1 Degrees of agency of the writer

Building on the parametrized findings from the transitivity analysis of all metaphors in the sample, a subsequent recursive cross-analysis of all metaphors and explanatory texts revealed three central topic areas. The first topic area is concerned with the varying degrees of agency that are attributed to the acting persons in the different metaphorical (re)constructions and how this variety is produced. Overall, the early-career researchers produced metaphors with traits of intermediate to high agency of the acting person. Only a few metaphors were assigned the maximum ratings of very high and very low transitivity. The two instances of very highly transitive metaphors were “The construction of a building” (02) and “Baking a wedding cake” (13; see the following discussion). There is no metaphor in which the writing person has no agency at all. As I show below, even highly intransitive metaphors use strategies to put the writer in a more agentive position. This overall picture suggests that agency in writing is experienced in very nuanced ways, neither as a strong power to act freely nor as a powerful activity to which writers are subjected.

Regarding the (re)construction of the writer's stance and the related agency patterns, two larger groups of metaphors could be identified. The first group consists of metaphors, in which writing is presented as an artisanal activity, where the writer has considerable capacity to shape both process and product. Most of these artisanal metaphors exhibit a relatively high overall degree of agency of the writer and elaborate conceptualizations of variegated events or states within one metaphorical scene. A specifically articulate example follows:

Baking a wedding cake. The baking of a wedding cake is a task that takes several days. Here I imagine a very pompous, elaborate in detail and multi-level cake. The floors reflect the individual areas of a paper/proposal. First, we have the second floor, which is the foundation. … The discussion/interpretation is the decoration of the cake. Here one is allowed to be a little more creative (13)

Further examples with these traits are as follows:

Making a jigsaw puzzle. One must try—from the chaos of ideas, thoughts, … and questions from the mountains of different literature and what goes through one's head (often of unclear origin)—to find or produce and assemble fitting pieces in writing/through writing. What the overall picture of the puzzle is, what fits and what doesn't, one often only sees at the end or when one has come a good bit further. (18)

Like shifting gears while driving or even piloting an airplane. ... there are quite a few things one has to pay attention to at the same time and therefore prepare oneself beforehand. (20)

In the second group of metaphors, the activity of writing and the text are often characterized as something large—more like a medium than like an object that could be handled. At the same time, most of these metaphors in the second group exhibit a relatively low level of agency of the writer, as the acting person is (re)constructed to have less capacity to shape the process. In the following example, this is particularly striking:

A sea. It [=the sea] is or can be often restless [un-calm] when it is windy. And so academic writing is also often restless [un-calm], because one does not know in which direction one should swim now and if the waves are very high, one can “swim” or “write” on one spot (04)

In such cases, the writer's agency is still given in that the acting person has to invest energy to move and can decide on a goal to move toward. But foremost, the indirect object of the writing activity, “the sea,” in this case, is presented as an acting entity with its own power of movement, here conceptualized in terms of very high waves and restlessness.

There is variegation within both groups. One especially graphic case of variegation within the group of writing as a larger object or medium metaphors are three instances of the conceptual metaphor WRITING IS HIKING OR MOUNTAINEERING. In all three cases, the process of writing is conceptualized as a large object or medium, as the hike itself. However, the degrees of agency assigned to the writer differ. Compare the following:

There are easier stages + more difficult stages one has to go through in both activities. (08)

When hiking as when writing, I climb mountains and cross valleys, sometimes this is easier, sometimes this is more difficult. (21)

There are stages that are easy (although they require “many meters of altitude”), other stages/routes are stony, exhausting and difficult to manage. … In addition to collaboration with other persons, the use of auxiliary means [aids, tools] is crucial. (09)

In the first example (08), the writer is forced to go through easier and more difficult stages of the writing process in terms of different phases of a hike, as indicated by the deontic modality marker “has to.” The second example projects less agency to the activity of writing and more agency to the writer, in that the writer's activity is presented in the indicative. Metaphor (09), even though it affirms that the process requires activity from the acting person, talks about “auxiliary means,” that is, objects that the hiking resp. writing person handles, and of purposeful “collaboration with other persons.” Both the objects and the interaction with others are used to “manage” the process. Thus, this third HIKING metaphor produces an impression of a very high agency of the acting person.

Concerning the metaphors that exhibit very low agency features, different strategies can be identified to either mitigate the power that is acting on the writer or to strengthen the writer's stance. For example, in “A medicine! It can effect something!” (22), the dynamic modality marker “can” reduces the power of the “effect”. A very interesting case is the following metaphor, where the participant-writer's voice can be heard in the form of questions posed to an unspecified addressee:

Dreaming. Sometimes dreams appear quite clear in their narration, vivid, involving and convincing. The next moment, however, everything can be quite blurry and confused. When does it begin, when does it end? Some dreams, like writing moments, stay kept in one's memory long and accurately, even come back again and again in variation. Others evaporate, fade away, fall into oblivion. Dreams are as creative as writing. Isn't writing also (as beautiful as) dreaming—isn't dreaming also writing (in one's mind)? (24)

The first questions—“When does it begin, when does it end?”—seem to construct the writer's self-addressed rumination when “everything [is] quite blurry and confused.” Even while being subjected to the power of the dream, the writing person is constructed to be a thinking and reflecting subject. The second combination of questions—“Isn't writing also (as beautiful as) dreaming—isn't dreaming also writing (in one's mind)?”—elevates the writer's agency even more. These questions appear after an explicit comparison between writing and dreaming: “Dreams are as creative as writing.” Therefore, and from the framing as typical rhetorical questions, Isn't X also Y?, it is probable that these latter questions are more overtly directed at a projected reader of the metaphorical text. With this move, the speaking person is not the writer-as-depicted-in-the-metaphor anymore. We can now hear the voice of the participant-writer, most probably addressing the researcher-reader.

4.3.2 The role of others

As becomes clear from the previous argument, the stance of the writing person as it is (re)constructed in and through the metaphors is intricately linked to other persons that are addressed, referred to, or implied in the texts. The role that other people play in a complex social practice as research writing is central for characterizing the degrees and qualities of agency that the participants assign to the writer in their (re)constructions of academic writing. The animateness of the “receivers” of an action is a crucial facet of the transitive semantics of an event (see Hopper and Thompson's 10th parameter). Furthermore, both more cognitive-psychologically and more socioculturally oriented models of the writing process and its development within enculturation (e.g., Prior and Bilbro, 2012) and expertization (e.g., Kellogg and Whiteford, 2009) stress the role that conceptualizations of addressees play for professionalizing writing (seminal: Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987; Kellogg, 2008).

In the material, however, there are only a few metaphors, where others, as the audience or readers of a piece of writing, are explicitly mentioned. For example:

Blowing up balloons. It reminds me of blowing up balloons because one often thinks one can make a whole big paper out of a very small beginning. … But sometimes one has to let some of the air out again because … the balloon has gotten too big to put in anyone's hand. (10)

Here, the other in question is a relatively “simple” receiver of an object created by the acting person. In other metaphors, others are, for example, conceptualized as spectators of the writing process or as offering help during the process, but they do not interfere in the activity itself:

A trip around the world. It starts with anticipation and curiosity about new and unknown things. … The reactions of friends are ambivalent: some think one is crazy, others admire one, some doubt, some have confidence. (23)

Spontaneously, I associate (academic) writing with mountaineering. … Through support from others (e.g., writing consultation, exchanges among colleagues about contents [topics], etc.) one is more likely to reach [rather reaches] one's goal. (09)

Whereas in the first example, the other persons have thoughts and opinions about the writing they witness (conceptualized as TRAVELING), the other persons in the second example are more active agents who talk with the writer about the writing process (conceptualized, quite similarly, as MOUNTAINEERING).

There is only one metaphor in the sample, where other people play an active role in writing:

Sports. … Moreover, academic writing is exhausting—one needs regular breaks, just like in sports, and both can be done in a team as well as alone. (19)

But even though semantically the activity of others is high, because the other persons function as co-authors, the linguistic realization projects a conceptualization of these co-authors that is rather low in agency: passive voice (“be done”), dynamic modality (“can”), and indirect object (“in a team”).

There are instances in the material where others are completely omitted linguistically and only implied by ways of conceptualization:

Painting by numbers. For me, academic writing is a very creative process that requires many search movements, but is framed by a set of rules that can help, but also limit. (14)

Here, others could be imagined to take part in the scene in terms of formulating, explicitly or implicitly, the “set of rules” that helps and constrains writers. In this vein, the role of others in the writing process is closely related to collective voices and norms as identified in the third topic area—however, typically, this role is rather alluded to or implied and not spelled out.

4.3.3 Collective voices, cultures, and norms

In the third topic area, the implication of a community of others, which typically does not get referred to explicitly, is central. Overall, and contrary to students (cf. Scharlau et al., 2021), the early-career academics in my sample used much more personal conceptual metaphors than culturally typical ones, like WRITING IS LIKE SWIMMING or WRITING IS LIKE A JOURNEY. I hypothesize that this is linked to their greater personal experience with academic writing. Early-career researchers probably tend to conceptualize agency-as-experienced rather than agency-as-idealized in their metaphors of writing. An example of a rather personal conceptualization follows:

A never-ending story. A lot of [very, very much] time passes before I am halfway satisfied with a text. If there were no deadlines, I don't know if I would have ever handed in one or the other text. Since—seen in this way—the dissertation has no deadline either, it is something like a never-ending story for me. (05)

Even though there were relatively many personal, non-conventionalized metaphorical conceptualizations, a number of what could be called “disciplinary metaphors” feature in the corpus. In these cases, writing is understood or conceptualized via other complex scientific concepts and not—contrary to a central tenet of CMT—via simpler everyday concepts or even primary metaphors. These disciplinary metaphors require a transfer of knowledge from one area of expertise to another. Consider the following and most striking example from the corpus:

Dimensionality reduction, i.e. in a mathematical sense the projection of high dimensional vector spaces into low dimensional vector spaces. One tries to find in the high-dimensional space of all knowledge and all previous studies the components that are relevant for one's own research project, in order to end up with a low-dimensional space that is clear [lit. “overviewish”] enough to grasp the topic, and to finally put one's own ideas into a one-dimensional form, the text. (03)

There were further metaphors that used a semiprofessional activity, that is, an activity in which one needs some knowledge as a cultural insider, as their source domain:

Playing the piano. Like playing the piano, one has to learn academic writing then practice it again and again. This also applies to the texts one writes. One does not immediately write the “perfect” text (the performing of the piano piece at a concert), but first “practices” and revises the text again and again until one has the final product (the concert performance, so to say). (17)

Sports. Just like sports—especially if one has not done any for a while—academic writing is hard to get started with. Both require a relatively large amount of practice, or at least regular practice, in order to become better and more confident at it. With regular practice, something like fun sets in, and it takes less effort … one usually feels better afterwards—one clears [gets cleared] one's head and, in the best case (at least on good days), one is proud of oneself. … (19)

Whereas the first example could also have been formulated by a person who has no experience with playing the piano, the second text has clear markers of an own experience with or insider knowledge of the source domain. The phrase “especially if one has not done any for a while” is presented as a personal aside (Hyland, 2005), and the phrases “something like fun sets in” and “one usually feels better afterwards” contain modality markers (the hedge “something” and the epistemic marker “usually”) that indicate meta-communicative hints toward how appropriate or how typical the encodings of the source domain experience are.

While I have argued that many participants chose personal over culturally typical metaphors and thus conceptualize agency-in-writing-as-experienced rather than agency-in-writing-as-idealized, many metaphors still reflect norms and the ways “things have to be.” This is especially visible in the deontic modality markers that were used, as in the following example:

Learning a language. … As a beginner, I must first learn the basic rules of academic writing until I am able to write a coherent, generally understandable text. An academic text itself should, in turn, derive the overarching theme in the same way from the basic concepts. (06)

Sometimes, a collective voice is explicitly cited and utters the disciplinary or academic norm of how scientific texts or writing should be:

Making a good coffee. The coffee powder is representative for the content input e.g. from literature or own collected data. Too much of a good thing makes the coffee too strong—there is too much talk or even “rambling” [too much is talked or even “rambled”] around the topic. Too little of it and the text is inconclusive or too superficial, which is comparable to a watery coffee. Only the right amount makes for a coherent, concise text—and a tasty coffee experience. (11)

Here, not only the norms or objectives of good academic writing themselves are named: “content input … from literature or own collected data,” “conclusive,” not “superficial,” and “a coherent, concise text.” Also, the ways of how to achieve this are indicated in terms of “the right amount” and “too much” or “too little.”

Collective voices become most graspable when focusing on the question of who is speaking and from what position, that is, the participant's stance or perspective on the writing scene as constructed in the metaphorical text. This means that a distinction has to be made between the participant-writer as the producer of the personal metaphor and the writer-as-acting-character of the writing scene that is depicted. There is a strong tendency in the sample to generalize the first-person perspective. In the German original texts, participants use the pronoun man (one) conspicuously often to speak about the writer in terms of the acting character of the scene. However, there are also many instances where the participants' first-person stance is explicitly marked with ich (I, me). Some metaphors exhibit both forms, as in the following examples:

Learning a language. One starts with the basics and works one's way through to the details and challenges. … As a beginner, I must first learn the basic rules of academic writing until I am able to write a coherent, generally understandable text. (06)

Tidying up. It is like tidying up, because I arrange what I have read and put it in a new order that is logical for me. After that, everything is beautiful and one likes to look at it. (16)

In these cases, the tension between subjectivity and collectivity of the first-person perspective in terms of “I” vs. “one,” as it is constructed in the texts, is graspable. The participant-writers associate themselves more or less directly with the writers-as-acting-characters. When they say “I,” they seem to project their very own subjective experience as writers, while when they say “one,” they appear to associate themselves with the generalized academic writer that is a typification of their own and others' experiences as academic writers.

The more subjective first-person perspective often goes together with a more or less clear addressing or including of the projected reader of the personal metaphor. Consider the following example:

Making a jigsaw puzzle and collage. … It's like “Now I have got something here” and “Now I have got something here, too”—“Oh, and here is something I can think of” = > Imagine doing a puzzle or collage from top, left to bottom right = > no way! (07)

This example exhibits a first-person pronoun to mark the writer's stance, for example, “Now I have got …”. This subjective first-person perspective is realized within instances of constructed speech that project the writer-as-acting-character's voiced utterances. Note that there is also an implied reader of the text, as can be seen in the imperative form “Imagine doing a puzzle …” and in the openly voiced form “no way!” The latter is not only framed as an exclamation of the speaking person (not the writer-as-acting-character) but, as such, can also be read as a more direct address of a projected reader.

Finally, they following example illustrates yet another way in which the first-person perspective and a marked address of a projected reader are realized:

The baking of a wedding cake is a task that takes several days. Here I imagine a very pompous, elaborate in detail and multi-level cake. The floors reflect the individual areas of a paper/proposal. First, we have the second floor, which is the foundation. … In general, one must not change much about the recipe (ingredients, baking time, resting time) to make the cake taste good. (13)

In this example, the expression “First, we have the second floor …” is striking. This is an inclusive “we” involving the projected reader, but it is also a typical generic form of baking recipes. As such, it not only speaks of a strong first-person perspective of the participant-writer, which involves a commonality with the addressee of the personal metaphor, but it also maps a typical relationship between text producers and receivers of cooking or baking recipes, which involves a certain form of perspective-taking and textual voice that is necessary to “teach” the right performance of the food preparation task—all of which is mapped onto explaining personal experience of academic writing to a researcher-reader.

5 Discussion: why academic writing is and is not like a roller-coaster ride

5.1 Summary of the main analytical findings

Looking at the overall tendency in the material, it is striking that early-career research writers use more personal conceptual metaphors for academic writing than relying on culturally typical source domains. Compared to samples of students' metaphors of academic writing and other related literacy practices (e.g., Scharlau et al., 2019, 2021), early-career researchers tend to conceptualize agency in writing as experienced rather than agency as idealized when they are asked to give their personal metaphors of academic writing. In the context of this observation, making a distinction between the study participants as the producers of their personal metaphors and the writers-as-acting-characters in the writing scenes depicted in these metaphors is crucial. As I have pointed out in the analysis, there is a strong tendency in the sample to generalize the first-person perspective, that is, to speak about writing from the perspective of a generalized or prototypical writer. In some cases, the early-career researchers use “I” in the explanatory texts to their metaphors, which may well project their own subjective experience as writers. But strikingly often, the participants use “one” when they speak about writing from the perspective of the writer. This suggests that in conceptualizing their personal experience with writing, early-career academics associate themselves with the position of a generalized academic writer—a position that most likely typifies their own and others' experiences in research writing and typical ways of speaking about writing in academia. Consequently, even though the metaphors in the sample draw on personal and relatively unstandardized source domains, they do not (re)construct purely individual experiences of the respective writers. Rather, their personal experiences of research writing seem to be saturated with cultural expectations and images of how writing typically is or should be.

Despite the tendency to generalize personal experience in metaphorical descriptions, agency in writing seems to be experienced in nuanced ways according to the heterogeneity of my material. Overall, the writers neither represent themselves to have a strong power to act freely nor do they (re)construct the writing process as a mechanism to which they are subjected completely. Rather, they often present research writing as an activity where the acting person has considerable capacity to shape both process and product, for example, as an artisanal or athletic activity. At the same time, writing and the text are often characterized as something large in the sample—rather like a medium or a contextual constellation than like smaller objects that could be handled easily. So, when, in many cases, writing is presented as an entity that can exhibit force on the writing person or as a situational constellation that calls for certain possibilities for action and restricts others, it is conceptualized as at least partly subjected to forces and circumstances that lie outside of the individual writer.

Interestingly, there are only a few instances where others, as the audience or reader(s) of a piece of writing, are explicitly mentioned as stakeholders that make claims or state expectations. Rather, the role of others in the writing process is associated with more generalized norms, expectations, and preconditions concerning writing. In a few instances, a collective voice is explicitly cited in a participant's personal metaphor and utters the disciplinary or academic norm of how scientific texts or writing should look. But generally, as with the writer's perspective, others' perspectives appear almost exclusively in a generalized, typified fashion. This observation fits nicely with the idea that academic professional development is about “becoming rhetorical” in the sense that Lee (2010) has coined: Academic writing is not so much about addressing concrete single readers as it is about developing as a writer to become understandable to others in the same social sphere.

5.2 Writing, identity, and agency: from voice to voices in writing

In writing studies, the issue of agency in writing has also been a longstanding focus of interest, albeit mostly with a different terminology. There, agency is often discussed under the headings of voice(s) and identity, especially concerning writers' development and enculturation into their respective communities of practice (Ivanič, 1998; Matsuda, 2015). The concept of agency surfaces mostly in terms of having a deliberate choice and making active decisions about one's writing and text within social relations. For example, Scott (1999, drawing on Kress, 1996) indicates that “agency in writing now connotes a social-individual engaged in remaking what is socially made (i.e., forms and meanings)—a remaking which is inevitably a transforming (even if only in small ways) of the writer's subjectivity” (p. 180). Such a view resonates well with my findings that research writers deal with socially shaped circumstances, saturated with collective norms and generalized expectations, and therefore present writing as an entity that exhibits force on the writing person or as a situational constellation that enables and restricts possibilities for action. However, writing studies seem to focus on textual decisions mostly. They interpret agency as “the author's ability to take on a position of their own” (Hutchings, 2014, p. 316), as expressing their voice in relation to others' voices in their text, or, as Tardy (2006, p. 63) puts it, “the way in which student-writers may appropriate the multiple texts that they encounter in their lives.” Extending this view, the present material suggests that issues of agency and voice in writing are not restricted to textual decisions. Many metaphors and explanatory texts focus more holistically on the process or activity of writing than on the shaping of the textual product alone. The material suggests that having agency in writing, thus, is not confined to having textual choice but permeates writing practice as a whole.

One facet of this change of perspective—from individual text production to the larger social practice of research writing—is to understand academic enculturation as a sociopsychological and discursive process taking place in and through language. This process involves both writing and talking and the complex interplay of these modes (see, e.g., Dysthe, 1996). Personal and collective voices transcend language modes in complex dialogical interactions (Karsten, 2024); they come from talking about writing and enter the individual socio-cognitive process of writing, or they come from others' texts and enter the way scholars talk and write about their research fields. These transmodal, transpersonal, and transsituational “wanderings” of voices do not take place on a thematic or content level; they happen in discourse, as discourse. One facet of these to-and-fro shiftings involves the multiple and variable encodings and performances of agency in writing as they have become apparent in the present material. Seen like this, academic writing is indeed like a roller-coaster ride—and researchers of writing and agency need elaborate methodological tools to trace its ever-shifting discursive and sociopsychological trajectories.

5.3 Metaphors and agency: methodological considerations

Even though there have been early claims in anthropological linguistics that the study of literacy practices is “[a]nother field of scholarship well situated to make significant contributions to our understanding of language and agency” (Ahearn, 2001, p. 127), writing has been rather neglected in research on agency in language so far. The present study thus not only proposes a way to develop metaphor research into a more discourse-analytical direction suitable for grasping agency as the discursively (re)constructed and socially assigned power to act. It also contributes to intertwining the fields of discourse and writing studies more tightly.

One sphere of interest that can profit from such an interdisciplinary approach is the nexus between the social and the personal in the study of agency. My analysis has shown that personal metaphors elicited from individual persons reflect both cultural views of the state or event in question and the subjective experience made in the respective cultural contexts and interactions. As Thomas and Beauchamp (2011) observe, “[o]ur experience with eliciting metaphors … showed us that although metaphors can provide insight into ways in which people conceptualize experience, they are also culturally bound, which can limit meaning and interpretation, rendering the accompanying explanation crucial” (p. 763, emphasis added). Future research could move beyond the exploratory character of the present study and focus more directly on how each metaphorical (re)construction in a given sample is connected to the person who has produced the text and their specific biographical experiences in disciplinary, cultural, and other contexts. This could be done, for example, through interviews, ethnographic methods, and/or larger mixed-method designs that assess demographic information and link to the metaphors produced. Such research could investigate how cultural experiences with metaphor as a poetic or rhetoric device might influence how a personal metaphor is framed. Also, through linking person and metaphorical (re)construction, collective voices and disciplinary norms could be more directly identified in both one-time and longitudinal study designs. Finally, and extending this last consideration, future research could focus on selected disciplinary or other academic contexts and investigate personal experiences of agency in research writing in a given social sphere in more detail, providing richer insight into the nexus of situated experience and cultural practice of research writing. For presumably, elicited personal metaphors accompanied by individual explanations will be less “objectivized” (Karsten and Bertau, 2019) than conceptual metaphors methodologically inferred from decontextualized and depersonalized examples of “naturally” occurring talk and text—they are closer to lived personal experience in the social world. In this vein, metaphor analysis can be a methodology to grasp aspects of lived personal experience that are (almost) beyond words, only barely conceivable and “objectifiable.” But to do so, it needs to take the specific situated and contextualized voiced forms of personal metaphors into account.

Author's note

The preprint can be found here: https://digital.ub.uni-paderborn.de/hs/content/titleinfo/7922976 (https://doi.org/10.17619/UNIPB/1-2267).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because data were collected in an anonymized form. At the time of data collection, no ethical approval was required for this type of data. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Part of this research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation): TRR 318/1 2021 – 438445824.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note