- 1Institute for Transfusion Medicine and Gene Therapy, Medical Center — University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany

- 2Center for Chronic Immunodeficiency (CCI), Faculty of Medicine, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany

- 3Ph.D. Program, Faculty of Biology, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is one of the most common hemoglobinopathies. Due to its high prevalence, with about 20 million affected individuals worldwide, the development of novel effective treatments is highly warranted. While transplantation of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) is the standard curative treatment approach, a variety of gene transfer and genome editing strategies have demonstrated their potential to provide a prospective cure for SCD patients. Several stratagems employing CRISPR-Cas nucleases or base editors aim at reactivation of γ-globin expression to replace the faulty β-globin chain. The fetal hemoglobin (HbF), consisting of two α-globin and two γ-globin chains, can compensate for defective adult hemoglobin (HbA) and reverse the sickling of hemoglobin-S (HbS). Both disruption of cis-regulatory elements that are involved in inhibiting γ-globin expression, such as BCL11A or LRF binding sites in the γ-globin gene promoters (HBG1/2), or the lineage-specific disruption of BCL11A to reduce its expression in human erythroblasts, have been demonstrated to reestablish HbF expression. Alternatively, the point mutation in the HBB gene has been corrected using homology-directed repair (HDR)-based methodologies. In general, genome editing has shown promising results not only in preclinical animal models but also in clinical trials, both in terms of efficacy and safety. This review provides a brief update on the recent clinical advances in the genome editing space to offer cure for SCD patients, discusses open questions with regard to off-target effects induced by the employed genome editors, and gives an outlook of forthcoming developments.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is one of the most common hemoglobinopathies, which comprises a group of disorders that are characterized by faulty hemoglobin production (1, 2). Hemoglobin, a two-way respiratory carrier in red blood cells (RBCs), is responsible for transporting oxygen to tissues and returning carbon dioxide to the lung. This tetrameric metalloprotein is composed of two α-subunits, two non-α-subunits, hem groups, and four iron atoms, giving hemoglobin the capacity for binding oxygen (3). For congenital forms of anemia, SCD and thalassemia have the highest incidence (4). According to the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), approximately 20 million people worldwide, including 52,000 people in Europe and 100,000 Americans, are affected by SCD. These patients suffer from anemia as well as progressive and fatal cardiovascular, renal, and eye complications due to the abnormal sickling shape of the RBCs that causes clogging of capillaries (1, 2). To alleviate morbidity, current treatment options include regular blood transfusions and the application of drugs that prevent vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC) or that reduce erythrocyte sickling. Still, life expectancy is reduced due to progressive organ dysfunction (1, 2). The only approved curative option for SCD is allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation, which requires the availability of “healthy” blood stem cells of siblings or non-related donors with matched human leukocyte antigen (HLA). Unfortunately, the difficulty of finding suitable donors early in childhood and the high risk of graft-vs.-host-disease limit the option of bone marrow transplantation for SCD patients (5, 6). One way to overcome this limitation is the use of autologous HSCs that are corrected ex vivo using gene therapy strategies to restore functional hemoglobin expression. Because of its genetics, SCD represents an ideal target for gene therapy in general and for genome editing in particular.

Hemoglobin expression

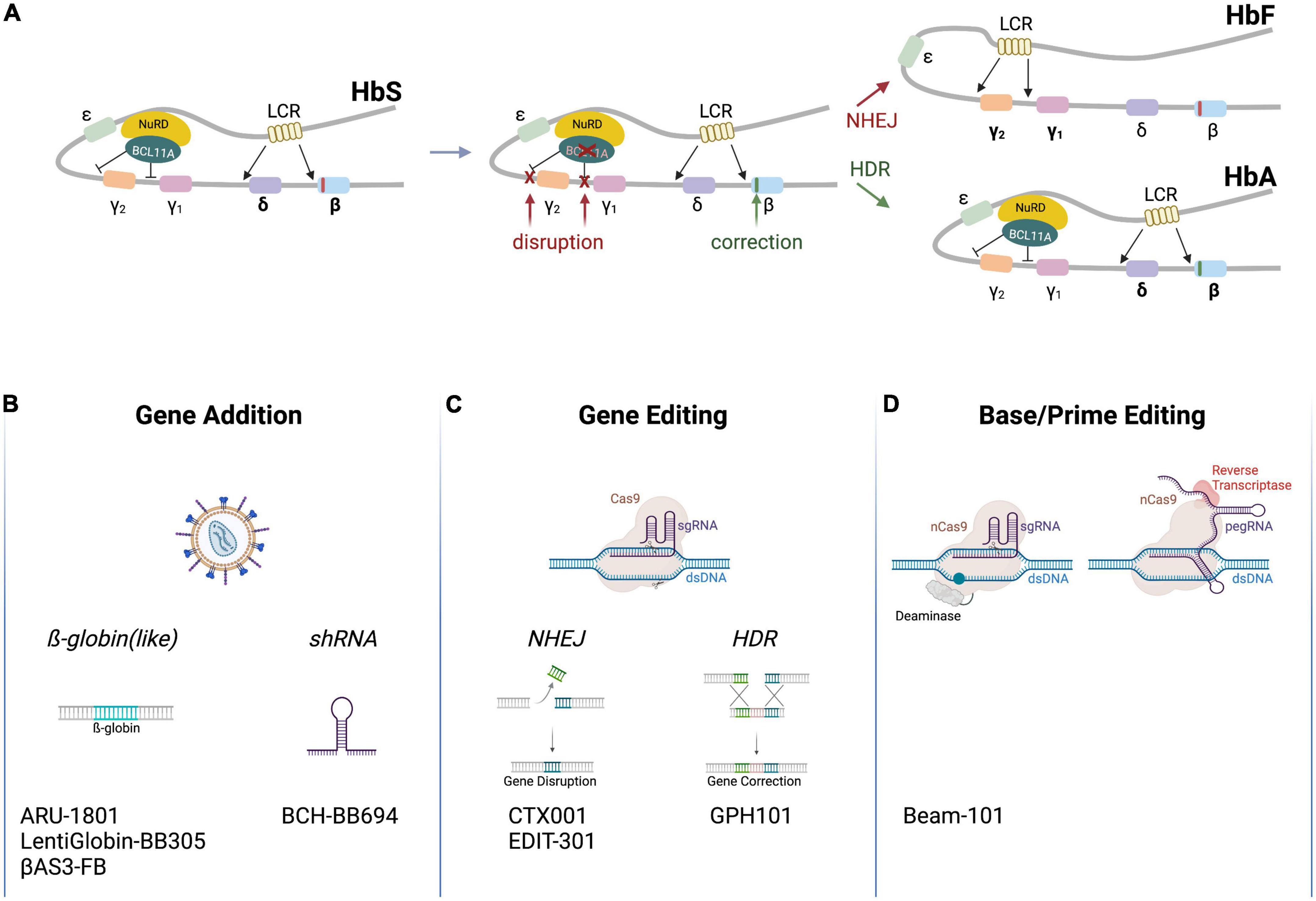

The two non-α-subunits of hemoglobin are encoded by five different genes located within the β-globin locus on chromosome 11 (Figure 1A). The respective genes, HBE (coding for ε-globin), HBG2 and HBG1 (γ-globin), HBD (δ-globin) and HBB (β-globin), are expressed in a developmental stage-specific manner in erythroid cells (7). A single locus control region (LCR) and specific enhancers are responsible for their sequential activation during development. In the early stage embryonic yolk sac, HBE is expressed. Later, hematopoiesis shifts to the liver and the HBG1/HBG2 genes (which are the result of a gene duplication and produce proteins that only differ in one amino acid) are activated to produce fetal hemoglobin (HbF, α2γ2). Shortly after birth, hematopoiesis relocates to the bone marrow, and HBD and HBB are expressed, leading to an almost complete replacement of HbF by adult hemoglobin HbA (>95% α2β2, 1.5–3.5% α2δ2; with 0.6–1% HbF persisting) (8). The γ-globin to β-globin switch is mediated by different transcription factors that repress HBG1/HBG2 expression, such as BCL11A and LRF (9, 10). Worthy of note, healthy individuals with a benign genetic condition called hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HPFH) exhibit persistent production of functional HbF even after birth. The molecular basis of HPFH are large deletions in the HBD and HBB genes, which increase interactions between the LCR and the HBG1/HBG2 promoters (11), or alternatively mutations in the cis-regulatory elements of the HBG genes, which are bound by the transcriptional repressors BCL11A and LRF (9, 10). If these repressors can no longer bind to the said cis-regulatory elements, HBG expression—and hence HbF production—persists (12).

Figure 1. Schematic of clinical genome editing approaches for SCD. (A) The β-globin locus. The locus encompasses HBE (encoding ε-globin), HBG2 and HBG1 (γ-globin), HBD (δ-globin) and HBB (β-globin). A locus control region (LCR) and various factors (depicted are BCL11A and NuRD) regulate developmental stage-specific expression of the hemoglobin genes. A point mutation in HBB (red box) leads to expression of HbS. Therapeutic gene editing strategies aim at correcting HBB via HDR (green box) or at disrupting cis-regulatory elements in the HBG2/HBG1 promoters or in BCL11A via NHEJ to re-activate γ-globin expression (red Xs), resulting in the expression of HbA (α2β2) or HbF (α2γ2), respectively. (B–D) Platform technologies used for the treatment of SCD. Clinically employed are (A) lentiviral vectors to transfer β-globin like genes or an shRNA targeting BCL11A mRNA, (B) genome editors to disrupt cis-regulatory elements by NHEJ or correct HBB by HDR, or (C) base and prime editors to disrupt cis-regulatory elements or off-set the mutation in HBB. The respective autologous, genome-engineered cell products are listed on the bottom (Created with BioRender.com).

Sickle cell disease arises as a result of a homozygous mutation in the HBB gene, in which a single point mutation leads to a codon change from gAg to gTg, resulting in a valine to glutamic acid substitution on the protein level (2). This swap in position six affects the hydrophobic characteristics of hemoglobin, converting HbA into the so-called sickle hemoglobin (HbS, α2βS2)—a term deduced from the sickle-like shape of the RBCs upon polymerization of HbS into fibers under deoxygenated conditions. The kinetic of hemoglobin polymerization is sensitive to the concentration of the HbS. Of note in this context, SCD patients with HPFH mutations present with mild clinical manifestations because HBG reactivation enables the formation of α2γ2 and α2γβS on top of α2βS2. Furthermore, the glutamine at position 87 (Q87) of γ-globin was shown to inhibit HbS polymerization and increase HbS solubility under deoxygenated conditions, so adding to the anti-sickling activity.

Gene therapy for SCD

The earliest attempts to genetically treat SCD were based on lentiviral (LV) transfer of a functional HBB copy to autologous HSCs (13). Bluebird Bio initiated first phase I/II gene therapy clinical trials in 2013 in France with seven patients (4 transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia, TDT, 3 SCD; HGB-205, NCT02151526) and in 2014 in the U.S. with 50 SCD patients (HGB-206, NCT02140554). The clinical product, LentiGlobin BB305 (Figure 1B), entails autologous HSCs transduced with an LV that encodes an anti-sickling variant of β-globin, known as βA-T87Q (mimicking the inhibitory effect of HbF on HbS polymerization). The recently published results confirmed stable βA-T87Q expression upon engraftment as well as reduced hemolysis, absence of VOC, and transfusion-independency (13, 14). A phase III clinical study (NCT04293185) with 35 SCD patients as well as a long-term follow-up study (NCT04628585) were opened in 2020. Based on these pivotal studies (15, 16), BB305 received marketing authorization from the EMA (17) and the FDA (18) under the trade name Zynteglo® for the treatment of transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia (TDT). Of note, two patients from the phase I/II BB305 study (NCT02140554) were diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) 2 years post-infusion (19), but AML development was not linked to insertional mutagenesis. The chosen conditioning regimen and/or the proliferative stress on HSCs upon switching from homeostatic to regenerative hematopoiesis might have played a role in AML induction and/or progression (14, 19).

Because high HbF expression ameliorates symptoms associated with SCD (20), efforts to develop LV-based approaches to increase γ-globin expression have been undertaken. This includes an LV expressing a γ-globinG16D variant that was shown to have increased affinity to α-globin (21). Clinical data (NCT02186418) showed long-lasting engraftment with potentially curative HbF levels (21). The Boston Children’s Hospital initiated a phase I clinical study with 10 patients in 2018 (NCT03282656) using autologous HSCs that were transduced with an LV (BCH-BB694) encoding a short-hairpin micro-RNA (shmiR) targeting the BCL11A mRNA (22). The six patients with long-term follow-up (7–29 months) showed high levels of HbF, mild clinical disease manifestation and no SAEs, prompting a phase II trial (NCT05353647) with 25 participants in 2022. Despite these successes, the high manufacturing costs of LV vectors (23), their potential of instigating abnormally spliced transcripts (24), as well as the risk of genotoxicity due to semi-random integration (25), limit the application of LV-based therapies.

Genome editing to treat SCD

Genome editing enables the site-specific modification of the human genome in order to correct or offset mutations underlying genetic disorders (26). Genome modification typically ensues from DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) that are introduced by programmable designer nucleases, such as zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) (27), transcription activator-like effector (TALE) nucleases (TALENs) (28, 29), or the CRISPR-Cas system (30). Other than the entirely protein-based ZFNs and TALENs, CRISPR-Cas nucleases contain an engineered guide (gRNA) that is complementary to the desired target sequence and that directs the Cas protein to the chosen genomic locus to induce a DSB (Figure 1C). Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and HDR are the two major repair pathways triggered by DSB formation (31). NHEJ is a fast but error-prone pathway, leading to insertions and deletions at the break site. NHEJ is hence typically employed to disrupt genes or cis-regulatory elements with high efficacy, reaching editing frequencies of over 90% in HSCs (26). In contrast, HDR is a slow but precise DNA repair pathway that uses a co-introduced DNA fragment as a template to correct disease underlying mutations inter alia. In HSCs, the HDR template is typically delivered by vectors based on adeno-associated virus (AAV) (32) or in the form of single-stranded or double-stranded oligonucleotides (ODNs) (33). However, because HDR is restricted to the S/G2 phase of the cell cycle, achieving gene targeting frequencies that exceed 20% in mainly quiescent long-term repopulating HSCs remains challenging (34).

Due to the genotoxic potential arising from DSB formation (see below), alternative platforms to edit the genome have been sought for Figure 1D. Such strategies are mostly based on CRISPR-Cas nickases that cleave only one DNA strand (35–37). This family includes base editors (BEs) (38, 39) and prime editors (PEs) (40). A Cas9 nuclease is converted to a Cas9 nickase by introducing mutations in one of the two catalytic domains of Cas9 (36). BEs were developed by fusing a deaminase domain to a Cas nickase (38). There are two types of BEs: cytosine base editors (CBEs) convert a C•G base pair (bp) into a T•A while adenine base editors (ABEs) convert an A•T to a G•C bp. BEs can be employed to correct point mutations, to introduce stop codons, or to disrupt cis-regulatory elements. PEs consist of a Cas9 nickase coupled to an engineered reverse transcriptase, which transcribes a section of the pegRNA (prime editing gRNA) into DNA to introduce the desired changes, such as base conversions or insertions/deletions of up to 80 bp (40).

Genome editing clinical trials for SCD

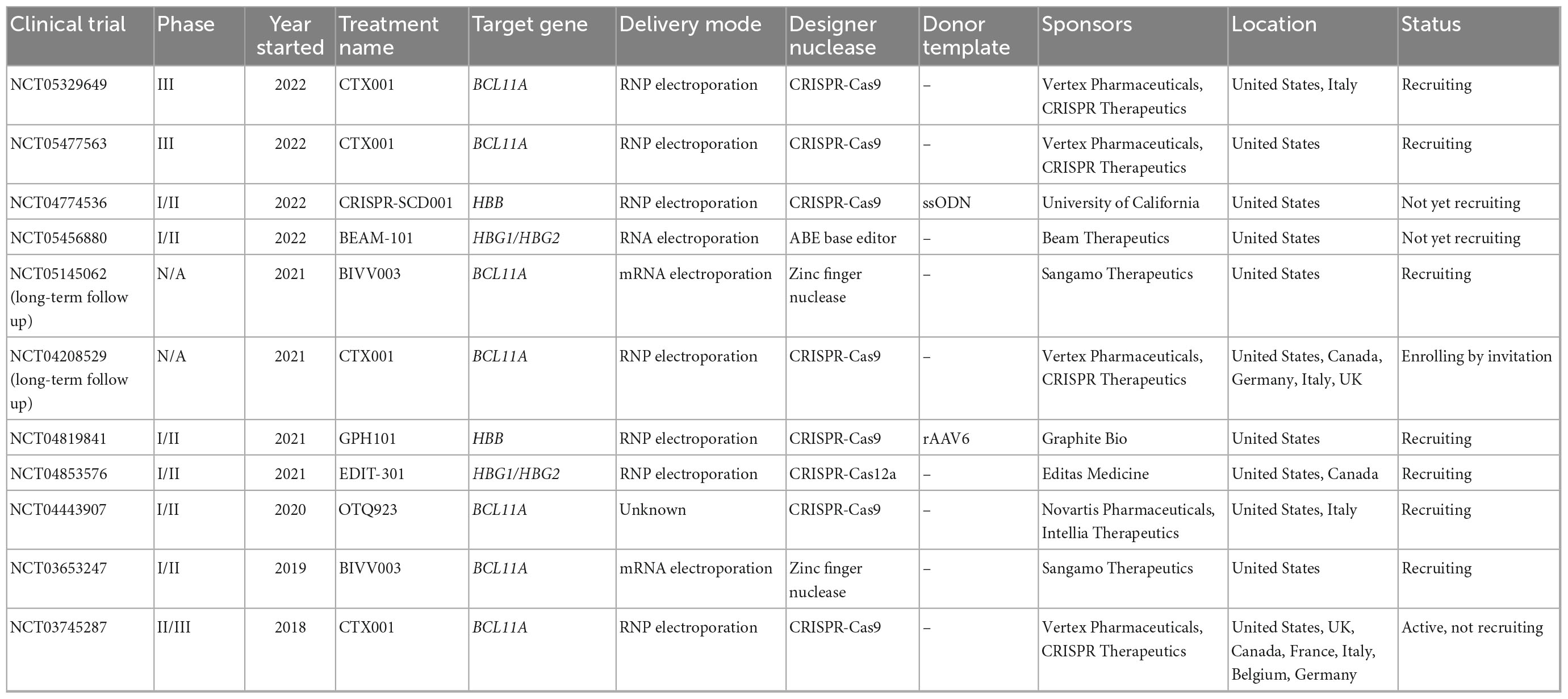

In the last 4 years, seven clinical trials using gene editing technologies to treat SCD have been initiated (Table 1). In all of them the editing agents are delivered ex vivo to autologous HSCs. Five of these therapeutic approaches attempt to reactivate γ-globin expression, either by preventing BCL11A expression in the erythroid lineage through disruption of enhancer elements or by mutating the BCL11A binding sites in the HBG promoters (Figure 1A). Two alternative approaches aim to correct the disease-causing mutation in the HBB locus using HDR (Figure 1A).

The most advanced product, CTX001, was developed by CRISPR Therapeutics and Vertex Pharmaceuticals. It is currently being tested in CLIMB-121, a phase II/III clinical trial (NCT03745287) that was started in 2018 with 45 SCD patients. CTX001 is administered as an autologous HSC product edited with CRISPR-Cas9 to disrupt the lineage-specific enhancer in the BCL11A gene. This alteration reduces BCL11A expression in erythroid cells, which in turn reactivates γ-globin expression. Published clinical data from the first two patients (one SCD and one TDT patient) demonstrated a high level of edited alleles in the stem cell compartment (69% and 80%). At 15 months post-transplantation, HbF levels in the SCD patient rose from 9.1 to 43.2%, while HbS levels were reduced from 74.1 to 52.3%. Patients were reported to be transfusion-independent and free of VOC. A recent update from infusion of CTX001 in 44 TDT and 31 SCD patients confirmed the overall positive response: All patients presented a sustained increase in HbF (39.6–49.6%), improvement in mean total Hb level (>11 g/dl) after 3 months, as well as elimination of VOC. Bone marrow analyses (>12 months follow-up) confirmed durable effects of this therapy over time with > 80% edited alleles. On the other hand, several severe adverse events (SAEs) were observed in patients upon infusion of the edited cells, such as VOC liver disease, sepsis, cholelithiasis, and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). Non-serious lymphopenia was also reported, most likely due to a delay in lymphocyte recovery (41, 42).

In 2019, Sangamo Therapeutics started a phase I/II clinical trial (NCT03653247) for eight SCD patients to assess the safety and efficacy of BIVV003, ex vivo manufactured autologous HSCs that were edited with ZFN technology to disrupt the BCL11A erythroid-specific enhancer. Data from week 26 post-transplantation of four patients showed increased HbF levels (14–39%) and F-cells raised to 48–94%. VOC was reported in one patient with a low level of HbF (14%). BIVV003 was well tolerated without the need for transfusions post-transplantation in all four patients (43). Besides adverse events related to plerixafor-based mobilization of CD34+ cells and busulfan conditioning, no SAEs related to the treatment were reported (43).

Conversely, it was reported that editing of the BCL11A erythroid enhancer can result in reduced erythroid output, which was not observed when the binding site of BCL11A in the HBG promoters was disrupted (44). Editas Medicine initiated in 2021 the phase I/II RUBY clinical trial (NCT04853576) with almost 40 participants to evaluate the efficacy and safety of EDIT-301, a product based on autologous HSCs in which the HBG1/2 promoter regions are disrupted using CRISPR-Cas12a. In preclinical mouse models, long-term engraftment of HBG1/2-edited HSCs was observed. The ∼90% edited target alleles went along with a high-level of HbF induction in cells from healthy donors (43%) and SCD patients (54%) with no detectable off-target effects (16, 44).

The 2021 initiated CEDAR trial (NCT04819841) is a phase I/II clinical study sponsored by Graphite Bio. As opposed to the previously described products, GPH101 is based on HDR and relies on a high-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9 system in combination with an AAV6-based HDR template. The goal is to correct the SCD-underlying point mutation in HBB. In preclinical mouse studies, almost 20% of HSCs harbored a corrected HBB locus (32), resulting in 90% of RBCs with normal HbA. The preclinical safety data revealed no evidence of abnormal hematopoiesis as well as absence of detectable off-target activity or chromosomal translocations. Graphite Bio recently announced the enrollment of the first patient, with up to 15 patients following at multiple sites in the U.S. Initial data from the CEDAR trial are expected for mid 2023.

Beam Therapeutics started a phase I/II clinical trial with 15 enrolled SCD patients in 2022 (NCT05456880). In BEAM-101, γ-globin expression is activated through a base swap in the HBG1/2 promoters using base editing to generate an HPFH genotype variant in autologous HSCs. Based on preclinical mouse data, > 90% of target sites in xenotransplanted HSCs were stably edited, resulting in high levels of γ-globin expression (>65% HbF) (45). Furthermore, an investigational new drug application was filed for BEAM-102, which was designed to change the point mutation in HBB from gTg to gCg. The result is a switch from glutamic acid to alanine in position 6, which converts HbS into a better tolerated HbG-Makassar (46).

Technical challenges of ex vivo genome editing approaches in HSCs are similar to those in LV-based approaches and comprise to reach a sufficient number of mobilized CD34 + cells as a starting material, sufficient editing efficacy in the LT-HSC compartment, a lower level of engraftment of ex vivo edited cells along with reduced stemness of edited HSCs (47–49).

Off-target effects

Similar to insertional mutagenesis associated with integrating vector systems, inadvertent on-target and off-target effects evoked by the genome editing tools represent a major concern when applied in patient cells, particularly in highly proliferating multipotent stem cells. On the one hand, cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases can trigger undesired effects on the target chromosome (50, 51), such as large deletions and inversions (52–54), chromosomal truncations (55), chromothripsis (56), aneuploidy (57), loss of heterozygosity (58), and loss of imprinting (58). On the other hand, unintentional activity at so-called off-target sites, that is sequences with high homology to the intended target site, triggers NHEJ-mediated insertion/deletion mutations at off-target sites and, potentially, comparable structural aberrations as described for the on-target site. Moreover, concomitant insertions of DSBs at multiple sites in the genome elicit translocations between those cleaved sites (54, 59). Several methods to predict or detect off-target activity and/or gross chromosomal rearrangements have been developed. They include deep sequencing of in silico predicted off-target sites as well as experimental procedures that detect off-target activity in vitro and in cell-based systems. Commonly used in vitro methods include CIRCLE-Seq (60), ONE-Seq (61) and NucleaSeq (62), while GUIDE-Seq (63), DISCOVER-Seq (64) and CAST-Seq (54) are prevalently used cell-based approaches. Noteworthy, CAST-Seq not only nominates off-target sites but also detects chromosomal rearrangements at the on-target site as well as induced chromosomal translocations with off-target sites (54).

The gene-edited products that are currently employed in clinical trials typically underwent several genotoxicity tests as part of the preclinical risk assessment. For instance, off-target activities of the CRISPR-Cas nucleases used in CTX001 and GPH101 were profiled by GUIDE-Seq, CIRCLE-Seq, and targeted amplicon next-generation sequencing (Amp-Seq) of in silico predicted off-target sites. Similarly, the safety of EDIT301 was investigated with GUIDE-Seq and Amp-Seq of in silico predicted off-target sites. Given that translocations are a hallmark of leukemic cells (65, 66) and since they can be rather frequent outcomes of genome editing (54, 59, 67, 68), there is a growing interest in detecting gross structural rearrangements, such as large chromosomal deletions, inversions, truncations, and translocations, too. To our knowledge, many of the above-mentioned products did not undergo a genome-wide and sensitive analysis of induced chromosomal rearrangements. Against the backdrop of the high sequence similarities within the β-globin locus (HBG1 vs. HBG2 or HBB vs. HBD), the potential for off-target editing as well as homology-mediated recombination between two respective paralogous genes is high (69). Indeed, rearrangements between HBB and HBD were confirmed in HBB-edited cell, in addition to translocations between HBB and an off-target site (54, 70, 71). In addition, CRISPR-Cas nucleases targeting either HBB, HBD or HBG1/HBG2 can lead to complete loss of the distal chromosome 11p arm in HSCs (58). Furthermore, the simultaneous disruption of the BCL11 binding sites in HBG1 and HBG2 was reported to result in deletion of the 4.9 kb region between the two target sites, eliminating HBG2 in 5–30% of cells (72–74).

To avoid this loss of the HBG2 gene, BEs were employed to introduce HPFH-like mutations in the HBG1/HBG2 promoters (75). Because single-strand nicks are repaired by the high-fidelity base-excision repair pathway, BEs have been claimed to reduce on-target and off-target effects (36). However, recent data demonstrated deletion of a 4.9 kb region after base editing of the HBG1/HBG2 promoters, indicating that also base editing can induce structural variations (76). Furthermore, bystander editing effects (77) and gRNA-independent off-target activities on both DNA and RNA (78, 79) have been described for both ABEs and CBEs. Hence, additional efforts are needed to characterize BE-associated off-target effects as well as to identify gross chromosomal rearrangements triggered by editing tools in HSCs of SCD (and TDT) patients. This also includes the evaluation of the biological long-term effects of genotoxicity in transplanted patients as well as the development of strategies to mitigate the observed off-target effects.

Future developments for SCD-directed genome editing

Genotoxic conditioning regimens still pose a major barrier to the adoption of autologous HSC transplantation in SCD (80, 81). To overcome this problem, Beam Therapeutic, among others, is developing a new approach termed “engineered stem cell antibody paired evasion,” in which a BE-introduced epitope switch in CD117 enables those CD117-edited HSCs to selectively escape CD117-directed antibody-based conditioning. Such a strategy can be easily applied to BEAM-101 by targeting CD117 and the HBG1/2 promoters simultaneously (82).

Are there additional transcription factors that could be targeted to upregulate γ-globin expression? MYB is a transcription factor that regulates fetal hemoglobin expression at multiple levels, including upregulation of BCL11A expression (83). ATF4 is further upstream and regulates the expression of MYB. It has been recently shown that knockout of ATF4 lowered MYB—and hence BCL11A—expression, and could thus potentially re-activate γ-globin expression (84). However, it must be noted that MYB and ATF4 have multiple functions outside of HbF regulation in non-erythroid cells (85, 86), highlighting the need to identify erythroid-specific regulation.

Given the constraints of off-target effects associated with all genome editing platforms, the question is whether alternatives to genome editing are available. Several studies deciphered the epigenetic regulation of the β-globin locus during development, including the interaction between epigenetic and transcriptional regulation leading to repression of γ-globin expression (87, 88). This knowledge opened up the idea to modify the epigenome in a targeted fashion for the treatment of SCD. While epigenetic approaches to promote γ-globin re-expression were described before (89, 90), more specific approaches are needed for clinical translation. Designer epigenome modifiers based on the TALE or CRISPR-dCas9 platforms create an opportunity to manipulate the epigenetic marks specifically and without the necessity to induce breaks in the genome (91, 92), e.g., by rewriting the epigenetic code in order to re-activate HBG expression or to silence BCL11A in a lineage-specific manner. Epigenome modifiers might therefore have less deleterious effects in a cell. On the other hand, the challenge of maintaining long-lasting effects over several cell cycles and throughout lineage differentiation has not been solved yet and it will be interesting to see whether the potential of designer epigenome modifiers can be harnessed for the treatment of SCD in the near future (93, 94).

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the writing and proofreading of the manuscript.

Funding

This research projects on hemoglobinopathies were supported by the European Commission (HORIZON-RIA EDITSCD grant no. 101057659 to TC) and the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD fellowship grant no. 91764871 to PZ). We further acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Freiburg.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the members of our department for thriving discussions on the presented topic.

Conflict of interest

TC had a sponsored research collaboration with Cellectis and was an advisor to Bird B., Cimeio Therapeutics, Excision BioTherapeutics, and Novo Nordisk. He holds several patents in the field, including patents on CAST-Seq (US11319580B2) and epigenome modifiers (US11072782B2).

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Kohne E. Hemoglobinopathies: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. (2011) 108:532–40. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0532

2. Brandow A, Liem R. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of sickle cell disease. J Hematol Oncol. (2022) 15:20. doi: 10.1186/s13045-022-01237-z

3. Marengo-Rowe A. Structure-function relations of human hemoglobins. Proc. (2006) 19:239–45. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2006.11928171

4. Anurogo D, Yuli Prasetyo Budi N, Thi Ngo M, Huang Y, Pawitan J. Cell and gene therapy for anemia: hematopoietic stem cells and gene editing. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:6275. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126275

5. Bolanos-Meade J, Cooke K, Gamper C, Ali S, Ambinder R, Borrello I, et al. Effect of increased dose of total body irradiation on graft failure associated with HLA-haploidentical transplantation in patients with severe haemoglobinopathies: a prospective clinical trial. Lancet Haematol. (2019) 6:e183–93. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30031-6

6. Eapen M, Brazauskas R, Walters M, Bernaudin F, Bo-Subait K, Fitzhugh C, et al. Effect of donor type and conditioning regimen intensity on allogeneic transplantation outcomes in patients with sickle cell disease: a retrospective multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Haematol. (2019) 6:e585–96. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30154-1

7. Wilber A, Nienhuis A, Persons D. Transcriptional regulation of fetal to adult hemoglobin switching: new therapeutic opportunities. Blood. (2011) 117:3945–53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-316893

8. Liang S, Moghimi B, Yang T, Strouboulis J, Bungert J. Locus control region mediated regulation of adult beta-globin gene expression. J Cell Biochem. (2008) 105:9–16. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21820

9. Sankaran V, Menne T, Xu J, Akie T, Lettre G, Van Handel B, et al. Human fetal hemoglobin expression is regulated by the developmental stage-specific repressor BCL11A. Science. (2008) 322:1839–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1165409

10. Martyn G, Wienert B, Yang L, Shah M, Norton L, Burdach J, et al. Natural regulatory mutations elevate the fetal globin gene via disruption of BCL11A or ZBTB7A binding. Nat Genet. (2018) 50:498–503. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0085-0

11. Steinberg M. Fetal hemoglobin in sickle hemoglobinopathies: high hbf genotypes and phenotypes. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:3782. doi: 10.3390/jcm9113782

12. Lamsfus-Calle A, Daniel-Moreno A, Antony J, Epting T, Heumos L, Baskaran P, et al. Comparative targeting analysis of KLF1, BCL11A, and HBG1/2 in CD34(+) HSPCs by CRISPR/Cas9 for the induction of fetal hemoglobin. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:10133. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66309-x

13. Kanter J, Walters M, Krishnamurti L, Mapara M, Kwiatkowski J, Rifkin-Zenenberg S, et al. Biologic and clinical efficacy of lentiglobin for sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. (2022) 386:617–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2117175

14. Magrin E, Semeraro M, Hebert N, Joseph L, Magnani A, Chalumeau A, et al. Long-term outcomes of lentiviral gene therapy for the beta-hemoglobinopathies: the HGB-205 trial. Nat Med. (2022) 28:81–8. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01650-w

15. Locatelli F, Thompson A, Kwiatkowski J, Porter J, Thrasher A, Hongeng S, et al. Betibeglogene autotemcel gene therapy for non-beta(0)/beta(0) genotype beta-thalassemia. N Engl J Med. (2022) 386:415–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2113206

16. Schneiderman J, Thompson A, Walters M, Kwiatkowski J, Kulozik A, Sauer M, et al. Interim results from the phase 3 hgb-207 (northstar-2) and hgb-212 (northstar-3) studies of betibeglogene autotemcel gene therapy (lentiglobin) for the treatment of transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2020) 26:S87–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.12.588

17. European Medicines Agency. Zynteglo. (2019). Available online at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/zynteglo#overview-section (accessed September 1, 2022).

18. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Cell-Based Gene Therapy to Treat Adult and Pediatric Patients With Beta-Thalassemia Who Require Regular Blood Transfusions. (2022). Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-cell-based-gene-therapy-treat-adult-and-pediatric-patients-beta-thalassemia-who (accessed September 1, 2022).

19. Jones R, DeBaun M. Leukemia after gene therapy for sickle cell disease: insertional mutagenesis, busulfan, both, or neither. Blood. (2021) 138:942–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021011488

20. Adekile A. The genetic and clinical significance of fetal hemoglobin expression in sickle cell disease. Med Princ Pract. (2021) 30:201–11. doi: 10.1159/000511342

21. Grimley M, Asnani M, Shrestha A, Felker S, Lutzko C, Arumugam P, et al. Early results from a phase 1/2 study of aru-1801 gene therapy for sickle cell disease (SCD): manufacturing process enhancements improve efficacy of a modified gamma globin lentivirus vector and reduced intensity conditioning transplant. Blood. (2020) 136(Suppl. 1):20–1. doi: 10.1182/blood-2020-140963

22. Esrick E, Lehmann L, Biffi A, Achebe M, Brendel C, Ciuculescu M, et al. Post-transcriptional genetic silencing of BCL11A to treat sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. (2021) 384:205–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2029392

23. Coquerelle S, Ghardallou M, Rais S, Taupin P, Touzot F, Boquet L, et al. Innovative curative treatment of beta thalassemia: cost-efficacy analysis of gene therapy versus allogenic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Hum Gene Ther. (2019) 30:753–61. doi: 10.1089/hum.2018.178

24. Cheng Y, Kang X, Chan P, Ye Z, Chan C, Jin D. Aberrant splicing events caused by insertion of genes of interest into expression vectors. Int J Biol Sci. (2022) 18:4914–31. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.72408

25. Cavazzana M, Bushman F, Miccio A, Andre-Schmutz I, Six E. Gene therapy targeting haematopoietic stem cells for inherited diseases: progress and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2019) 18:447–62. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0020-9

26. Cornu T, Mussolino C, Cathomen T. Refining strategies to translate genome editing to the clinic. Nat Med. (2017) 23:415–23. doi: 10.1038/nm.4313

27. Carroll D. Genome engineering with zinc-finger nucleases. Genetics. (2011) 188:773–82. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.131433

28. Mussolino C, Cathomen T. TALE nucleases: tailored genome engineering made easy. Curr Opin Biotechnol. (2012) 23:644–50. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.01.013

29. Joung J, Sander J. TALENs: a widely applicable technology for targeted genome editing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2013) 14:49–55. doi: 10.1038/nrm3486

30. Ran F, Hsu P, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott D, Zhang F. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc. (2013) 8:2281–308. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143

31. Carusillo A, Mussolino C. DNA damage: from threat to treatment. Cells. (2020) 9:1665. doi: 10.3390/cells9071665

32. Lattanzi A, Camarena J, Lahiri P, Segal H, Srifa W, Vakulskas C, et al. Development of beta-globin gene correction in human hematopoietic stem cells as a potential durable treatment for sickle cell disease. Sci Transl Med. (2021) 13:eabf2444. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abf2444

33. DeWitt M, Magis W, Bray N, Wang T, Berman J, Urbinati F, et al. Selection-free genome editing of the sickle mutation in human adult hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Sci Transl Med. (2016) 8:360ra134. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf9336

34. Salisbury-Ruf C, Larochelle A. Advances and obstacles in homology-mediated gene editing of hematopoietic stem cells. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:513. doi: 10.3390/jcm10030513

35. Mali P, Aach J, Stranges P, Esvelt K, Moosburner M, Kosuri S, et al. CAS9 transcriptional activators for target specificity screening and paired nickases for cooperative genome engineering. Nat Biotechnol. (2013) 31:833–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2675

36. Ran F, Hsu P, Lin C, Gootenberg J, Konermann S, Trevino A, et al. Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell. (2013) 154:1380–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021

37. Shen B, Zhang W, Zhang J, Zhou J, Wang J, Chen L, et al. Efficient genome modification by CRISPR-Cas9 nickase with minimal off-target effects. Nat Methods. (2014) 11:399–402. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2857

38. Komor A, Kim Y, Packer M, Zuris J, Liu D. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature. (2016) 533:420–4. doi: 10.1038/nature17946

39. Gaudelli N, Komor A, Rees H, Packer M, Badran A, Bryson D, et al. Programmable base editing of A*T to G*C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature. (2017) 551:464–71. doi: 10.1038/nature24644

40. Anzalone A, Randolph P, Davis J, Sousa A, Koblan L, Levy J, et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature. (2019) 576:149–57. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1711-4

41. Frangoul H, Altshuler D, Cappellini M, Chen Y, Domm J, Eustace B, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia. N Engl J Med. (2021) 384:252–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2031054

42. Grupp S, Bloberger N, Campbell C, Carroll C, Hankins J, Ho T, et al. CTX001 for sickle cell disease: safety and efficacy results from the ongoing climb SCD-121 study of autologous CRISPR-Cas9-modified CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. HemaSphere. (2021) 5:365.

43. Alavi A, Krishnamurti L, Abedi M, Galeon I, Reiner D, Smith S, et al. Preliminary safety and efficacy results from precizn-1: an ongoing phase 1/2 study on zinc finger nuclease-modified autologous CD34+ HSPCS for sickle cell disease (SCD). Blood. (2021) 138(Suppl. 1):2930. doi: 10.1182/blood-2021-151650

44. Heath J, de Dreuzy E, Sanchez M, Haskett S, Wang T, Sousa P, et al. editors. PS1518: Genome editing of HBG1/2 promoter leads to robust HbF induction in vivo, while editing of BCL11A erythroid enhancer results in defects. HemaSphere. (2019) 3:699–700. doi: 10.1097/01.HS9.0000564332.87522.af

45. Gaudelli N. Applied base editing to treat beta hemoglobinopathies. (2021). Available online at: https://beamtx.com/science/posters-and-presentations/ (accessed September 1, 2022).

46. Chu S, Ortega M, Feliciano P, Winton V, Xu C, Haupt D, et al. Conversion of HbS to Hb G-makassar by adenine base editing is compatible with normal hemoglobin function. Blood. (2021) 138(Suppl. 1):951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2021-150922

47. Morgan R, Gray D, Lomova A, Kohn D. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy: progress and lessons learned. Cell Stem Cell. (2017) 21:574–90. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.10.010

48. Zonari E, Desantis G, Petrillo C, Boccalatte F, Lidonnici M, Kajaste-Rudnitski A, et al. Efficient ex vivo engineering and expansion of highly purified human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell populations for gene therapy. Stem Cell Rep. (2017) 8:977–90. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.02.010

49. Wilkinson A, Igarashi K, Nakauchi H. Haematopoietic stem cell self-renewal in vivo and ex vivo. Nat Rev Genet. (2020) 21:541–54. doi: 10.1038/s41576-020-0241-0

50. Boutin J, Cappellen D, Rosier J, Amintas S, Dabernat S, Bedel A, et al. ON-target adverse events of CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease: more chaotic than expected. CRISPR J. (2022) 5:19–30. doi: 10.1089/crispr.2021.0120

51. Amendola M, Brusson M, Miccio A. CRISPRthripsis: the risk of CRISPR/Cas9-induced chromothripsis in gene therapy. Stem Cells Transl Med. (2022) 11:1003–9. doi: 10.1093/stcltm/szac064

52. Kosicki M, Tomberg K, Bradley A. Repair of double-strand breaks induced by CRISPR-Cas9 leads to large deletions and complex rearrangements. Nat Biotechnol. (2018) 36:765–71. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4192

53. Adikusuma F, Piltz S, Corbett M, Turvey M, McColl S, Helbig K, et al. Large deletions induced by Cas9 cleavage. Nature. (2018) 560:E8–9. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0380-z

54. Turchiano G, Andrieux G, Klermund J, Blattner G, Pennucci V, El Gaz M, et al. Quantitative evaluation of chromosomal rearrangements in gene-edited human stem cells by CAST-Seq. Cell Stem Cell (2021) 28:1136–47e5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.02.002

55. Cullot G, Boutin J, Toutain J, Prat F, Pennamen P, Rooryck C, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing induces megabase-scale chromosomal truncations. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:1136. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09006-2

56. Leibowitz M, Papathanasiou S, Doerfler P, Blaine L, Sun L, Yao Y, et al. Chromothripsis as an on-target consequence of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Nat Genet. (2021) 53:895–905. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00838-7

57. Nahmad A, Reuveni E, Goldschmidt E, Tenne T, Liberman M, Horovitz-Fried M, et al. Frequent aneuploidy in primary human T cells after CRISPR-Cas9 cleavage. Nat Biotechnol. (2022) 40:1807–13. doi: 10.1038/s41587-022-01377-0

58. Boutin J, Rosier J, Cappellen D, Prat F, Toutain J, Pennamen P, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 globin editing can induce megabase-scale copy-neutral losses of heterozygosity in hematopoietic cells. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:4922. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25190-6

59. Samuelson C, Radtke S, Zhu H, Llewellyn M, Fields E, Cook S, et al. Multiplex CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in hematopoietic stem cells for fetal hemoglobin reinduction generates chromosomal translocations. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. (2021) 23:507–23. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2021.10.008

60. Tsai S, Nguyen N, Malagon-Lopez J, Topkar V, Aryee M, Joung J. CIRCLE-seq: a highly sensitive in vitro screen for genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease off-targets. Nat Methods. (2017) 14:607–14. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4278

61. Petri K, Kim D, Sasaki K, Canver M, Wang X, Shah H, et al. Global-scale CRISPR gene editor specificity profiling by ONE-seq identifies population-specific, variant off-target effects. Biorxiv. [Preprint]. (2021). doi: 10.1101/2021.04.05.438458

62. Jones S Jr., Hawkins J, Johnson N, Jung C, Hu K, Rybarski J, et al. Massively parallel kinetic profiling of natural and engineered CRISPR nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. (2021) 39:84–93. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0646-5

63. Tsai S, Zheng Z, Nguyen N, Liebers M, Topkar V, Thapar V, et al. GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. (2015) 33:187–97. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3117

64. Wienert B, Wyman S, Richardson C, Yeh C, Akcakaya P, Porritt M, et al. Unbiased detection of CRISPR off-targets in vivo using DISCOVER-Seq. Science. (2019) 364:286–9. doi: 10.1126/science.aav9023

65. Teachey D, Pui C. Comparative features and outcomes between paediatric T-cell and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. (2019) 20:e142–54. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30031-2

66. Kayser S, Levis M. Clinical implications of molecular markers in acute myeloid leukemia. Eur J Haematol. (2019) 102:20–35. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13172

67. Frock R, Hu J, Meyers R, Ho Y, Kii E, Alt F. Genome-wide detection of DNA double-stranded breaks induced by engineered nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. (2015) 33:179–86. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3101

68. Bothmer A, Gareau K, Abdulkerim H, Buquicchio F, Cohen L, Viswanathan R, et al. Detection and modulation of DNA translocations during multi-gene genome editing in T cells. CRISPR J. (2020) 3:177–87. doi: 10.1089/crispr.2019.0074

69. Long J, Hoban M, Cooper A, Kaufman M, Kuo C, Campo-Fernandez B, et al. Characterization of gene alterations following editing of the beta-globin gene locus in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Mol Ther. (2018) 26:468–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.11.001

70. Hoban M, Cost G, Mendel M, Romero Z, Kaufman M, Joglekar A, et al. Correction of the sickle cell disease mutation in human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Blood. (2015) 125:2597–604. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-615948

71. Hoban M, Lumaquin D, Kuo C, Romero Z, Long J, Ho M, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated correction of the sickle mutation in human CD34+ cells. Mol Ther. (2016) 24:1561–9. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.148

72. Metais J, Doerfler P, Mayuranathan T, Bauer D, Fowler S, Hsieh M, et al. Genome editing of HBG1 and HBG2 to induce fetal hemoglobin. Blood Adv. (2019) 3:3379–92. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000820

73. Li C, Psatha N, Sova P, Gil S, Wang H, Kim J, et al. Reactivation of gamma-globin in adult beta-YAC mice after ex vivo and in vivo hematopoietic stem cell genome editing. Blood. (2018) 131:2915–28. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-03-838540

74. Weber L, Frati G, Felix T, Hardouin G, Casini A, Wollenschlaeger C, et al. Editing a gamma-globin repressor binding site restores fetal hemoglobin synthesis and corrects the sickle cell disease phenotype. Sci Adv. (2020) 6:eaay9392. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aay9392

75. Ravi N, Wienert B, Wyman S, Bell H, George A, Mahalingam G, et al. Identification of novel HPFH-like mutations by CRISPR base editing that elevate the expression of fetal hemoglobin. Elife. (2022) 11:e65421. doi: 10.7554/eLife.65421

76. Antoniou P, Hardouin G, Martinucci P, Frati G, Felix T, Chalumeau A, et al. Base-editing-mediated dissection of a gamma-globin cis-regulatory element for the therapeutic reactivation of fetal hemoglobin expression. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:6618. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34493-1

77. Chu S, Packer M, Rees H, Lam D, Yu Y, Marshall J, et al. Rationally designed base editors for precise editing of the sickle cell disease mutation. CRISPR J. (2021) 4:169–77. doi: 10.1089/crispr.2020.0144

78. Zuo E, Sun Y, Wei W, Yuan T, Ying W, Sun H, et al. Cytosine base editor generates substantial off-target single-nucleotide variants in mouse embryos. Science. (2019) 364:289–92. doi: 10.1126/science.aav9973

79. Grunewald J, Zhou R, Garcia S, Iyer S, Lareau C, Aryee M, et al. Transcriptome-wide off-target RNA editing induced by CRISPR-guided DNA base editors. Nature. (2019) 569:433–7. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1161-z

80. Cavazzana M, Mavilio F. Gene therapy for hemoglobinopathies. Hum Gene Ther. (2018) 29:1106–13. doi: 10.1089/hum.2018.122

81. Cavazzana M, Ribeil J, Lagresle-Peyrou C, Andre-Schmutz I. Gene therapy with hematopoietic stem cells: the diseased bone marrow’s point of view. Stem Cells Dev. (2017) 26:71–6. doi: 10.1089/scd.2016.0230

82. Gaudelli N. Non-genotoxic antibody-based conditioning paired with multi-plex base edited HSCs for the potential treatment of sickle cell disease. (2022). Available online at: https://beamtx.com/science/posters-and-presentations/ (accessed September 1, 2022).

83. Antoniani C, Romano O, Miccio A. Concise review: epigenetic regulation of hematopoiesis: biological insights and therapeutic applications. Stem Cells Transl Med. (2017) 6:2106–14. doi: 10.1002/sctm.17-0192

84. Boontanrart M, Schroder M, Stehli G, Banovic M, Wyman S, Lew R, et al. ATF4 regulates MYB to increase gamma-globin in response to loss of beta-globin. Cell Rep. (2020) 32:107993. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107993

85. Ameri K, Harris A. Activating transcription factor 4. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. (2008) 40:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.01.020

86. Greig K, Carotta S, Nutt S. Critical roles for c-myb in hematopoietic progenitor cells. Semin Immunol. (2008) 20:247–56. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2008.05.003

87. Van der Ploeg L, Flavell R. DNA methylation in the human γδβ-globin locus in erythroid and nonerythroid tissues. Cell. (1980) 19:947–58. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90086-0

88. Busslinger M, Hurst J, Flavell R. DNA methylation and the regulation of globin gene expression. Cell. (1983) 34:197–206. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90150-2

89. Holshouser S, Cafiero R, Robinson M, Kirkpatrick J, Casero R Jr, Hyacinth H, et al. Epigenetic reexpression of hemoglobin f using reversible lsd1 inhibitors: potential therapies for sickle cell disease. ACS Omega. (2020) 5:14750–8. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c01585

90. Starlard-Davenport A, Fitzgerald A, Pace B. Exploring epigenetic and microRNA approaches for gamma-globin gene regulation. Exp Biol Med. (2021) 246:2347–57. doi: 10.1177/15353702211028195

91. Hilton I, D’Ippolito A, Vockley C, Thakore P, Crawford G, Reddy T, et al. Epigenome editing by a CRISPR-Cas9-based acetyltransferase activates genes from promoters and enhancers. Nat Biotechnol. (2015) 33:510–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3199

92. Mlambo T, Nitsch S, Hildenbeutel M, Romito M, Muller M, Bossen C, et al. Designer epigenome modifiers enable robust and sustained gene silencing in clinically relevant human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. (2018) 46:4456–68. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky171

93. Huerne K, Palmour N, Wu A, Beck S, Berner A, Siebert R, et al. Auditing the editor: a review of key translational issues in epigenetic editing. CRISPR J. (2022) 5:203–12. doi: 10.1089/crispr.2021.0094

Keywords: base editing, clinical trial, CRISPR-Cas, γ-globin, gene editing, HBB gene, HbF

Citation: Zarghamian P, Klermund J and Cathomen T (2023) Clinical genome editing to treat sickle cell disease—A brief update. Front. Med. 9:1065377. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.1065377

Received: 09 October 2022; Accepted: 14 December 2022;

Published: 09 January 2023.

Edited by:

Robert W. Maitta, Case Western Reserve University, United StatesReviewed by:

Ciaran Michael Lee, University College Cork, IrelandAlireza Paikari, Baylor College of Medicine, United States

Copyright © 2023 Zarghamian, Klermund and Cathomen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Toni Cathomen,  dG9uaS5jYXRob21lbkB1bmlrbGluaWstZnJlaWJ1cmcuZGU=

dG9uaS5jYXRob21lbkB1bmlrbGluaWstZnJlaWJ1cmcuZGU=

†ORCID: Julia Klermund, orcid.org/0000-0001-6069-8189

Parinaz Zarghamian

Parinaz Zarghamian Julia Klermund1,2†

Julia Klermund1,2† Toni Cathomen

Toni Cathomen