- Department of Burn and Wound Repair Surgery, Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences), Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

This study summarizes the nursing care for a patient with intracerebral hemorrhage complicated with toxic epidermal necrolysis, focusing on infection prevention and control. Advanced health assessment showed that the primary nursing issue was a high risk of infection. Nursing interventions were implemented to prevent and control infection in various systems, emphasizing four key aspects: respiratory management after tracheostomy, lumbar cistern drainage care, skin management, and nutritional support. The patient’s skin healed, infection indicators decreased, and no secondary infections occurred. On the 24th day after admission, the patient was transferred to the neurosurgery department for ventriculoperitoneal shunt surgery. The patient was transferred to a rehabilitation hospital 21 days after surgery.

1 Introduction

Hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage is one of the most common critical diseases, with severe cases often leading to coma. Among elderly patients, pulmonary function decline combined with prolonged bed rest significantly increases the risk of infection. The extensive use of antibiotics to treat these infections frequently leads to adverse drug reactions due to the concurrent administration of multiple antimicrobial agents (1), further compromising immune function. Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is a predominantly drug-induced, life-threatening severe cutaneous adverse reaction (2). Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), the most severe form of SJS, is primarily triggered by medications such as antibiotics, antipyretics/analgesics, sulfonamides, and barbiturates. Clinically, it is characterized by widespread keratinocyte death, presenting with blistering, mucosal sloughing, and epidermal necrosis. The fulminant course of TEN involves extensive skin exfoliation, resulting in substantial protein loss and fluid-electrolyte imbalance. Severe cases may lead to death from secondary infections, with reported mortality rates ranging from 14.8% to 48.0% (3). In patients with TEN, the loss of the skin’s barrier function confers a significant predisposition to secondary infections (4). Sepsis arising from these infections is the leading cause of mortality in severe cases, with mortality rates approaching 50% in the elderly population (5). Therefore, infection prevention and control are critical to improving patients’ outcomes. In October 2024, our department admitted an elderly patient with intracerebral hemorrhage complicated by severe TEN. Through advanced health assessment, a high risk of infection was identified as the primary nursing issue. Based on infection prevention and control across various systems, nursing interventions focused on four key areas: respiratory management after tracheostomy, lumbar cistern drainage care, skin management, and nutritional support. The outcomes were remarkable, the patient’s skin healed, indicators of infection were markedly decreased, and no sign of secondary infection was observed. On the 24th day after admission, the patient was transferred to the neurosurgery department for ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement. Twenty-one days postoperatively, the patient was discharged to a rehabilitation hospital. The detailed nursing process is reported as follows:

2 Case description

2.1 General information

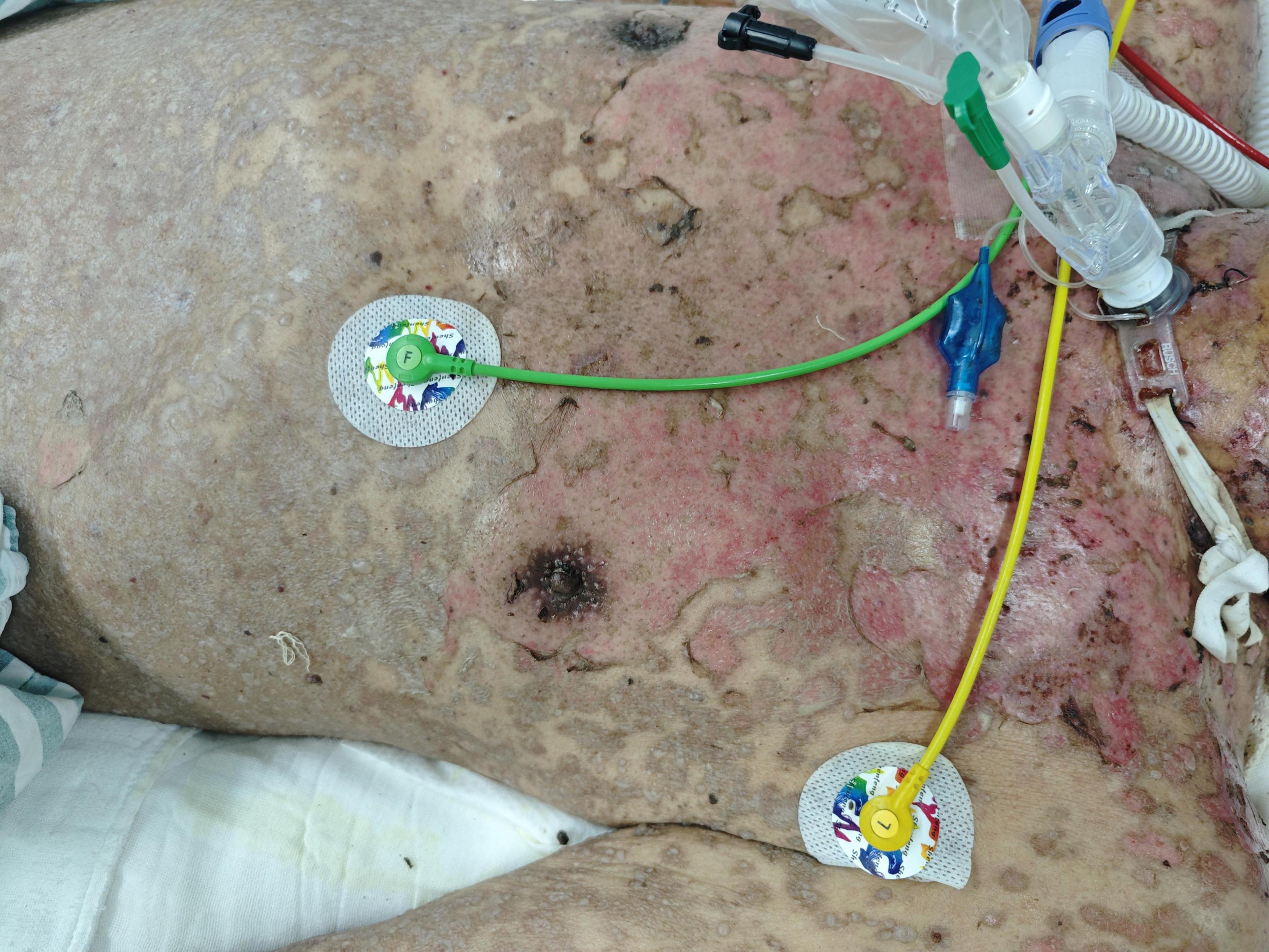

A 69 years-old bedbound male acutely developed an altered level of consciousness on 3 September 2024. Cranial CT at an external hospital revealed intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) with intraventricular extension (IVH). Emergency bilateral external ventricular drain (EVD) placement and intracranial pressure (ICP) monitor insertion were performed. On the afternoon of October 7, multiple erythematous patches emerged on his trunk, managed empirically as allergic dermatitis with dexamethasone and calcium gluconate. That evening, recurrent multifocal ICH with IVH occurred, requiring resuscitation before transfer back to the EICU. From October 9, the cutaneous rash progressed, involving the chest and abdominal regions. He received intravenous dexamethasone 10 mg daily, methylprednisolone 40 mg daily, and a single dose of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) 20 g. While the right abdominal rash improved, lesions on the neck, chest, and back persisted, with epidermal detachment and Nikolsky sign-positive skin sloughing, particularly on the posterior neck and back. He was transferred to our institution on October 18 for specialized management of suspected TEN, a complication arising >1 month post-ICH. Background: Non-contributory birth/origin history. No significant toxicant or occupational dust exposure. Regular lifestyle. No drug allergy history. Negative family history of diabetes, hypertension, or genetic disorders. The family demonstrates full adherence to care protocols. On admission, his vital signs were as follows: temperature 36.4°C, pulse 100 beats/min, respiration 20 breaths/min, and blood pressure 130/67 mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa). Physical examination revealed shallow coma, bilaterally equal and round pupils with a diameter of 1 mm, sluggish light reflexes, and a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of E1V1M4. More than 70% of the patient’s skin exhibited epidermal detachment, most prominently on the head, face, neck, trunk, and upper limbs. There was minimal exudation with no extensive peeling; oral and nasal mucosa were also involved. The lumbar cistern drainage tube demonstrated poor patency, with a low output of daily cerebrospinal fluid. The patient presented with pulmonary infection, characterized by abundant thick sputum. Laboratory tests showed that white blood cell count was 24.70 × 109/L, hemoglobin level was 94 g/L, platelet count was 329 × 109/L, neutrophil ratio was 0.906, partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) was 83.8 mmHg, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) was 41.2 mmHg, pH was 7.445, (1→3)-β-D-glucan level was 883.3 pg/mL, albumin level was 26.6 g/L, D-dimer level was 1,450 ng/mL, and interleukin-6 (IL-6) level was 33.9 pg/mL. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with TEN, hydrocephalus, and pulmonary infection.

2.2 Treatment process and outcomes

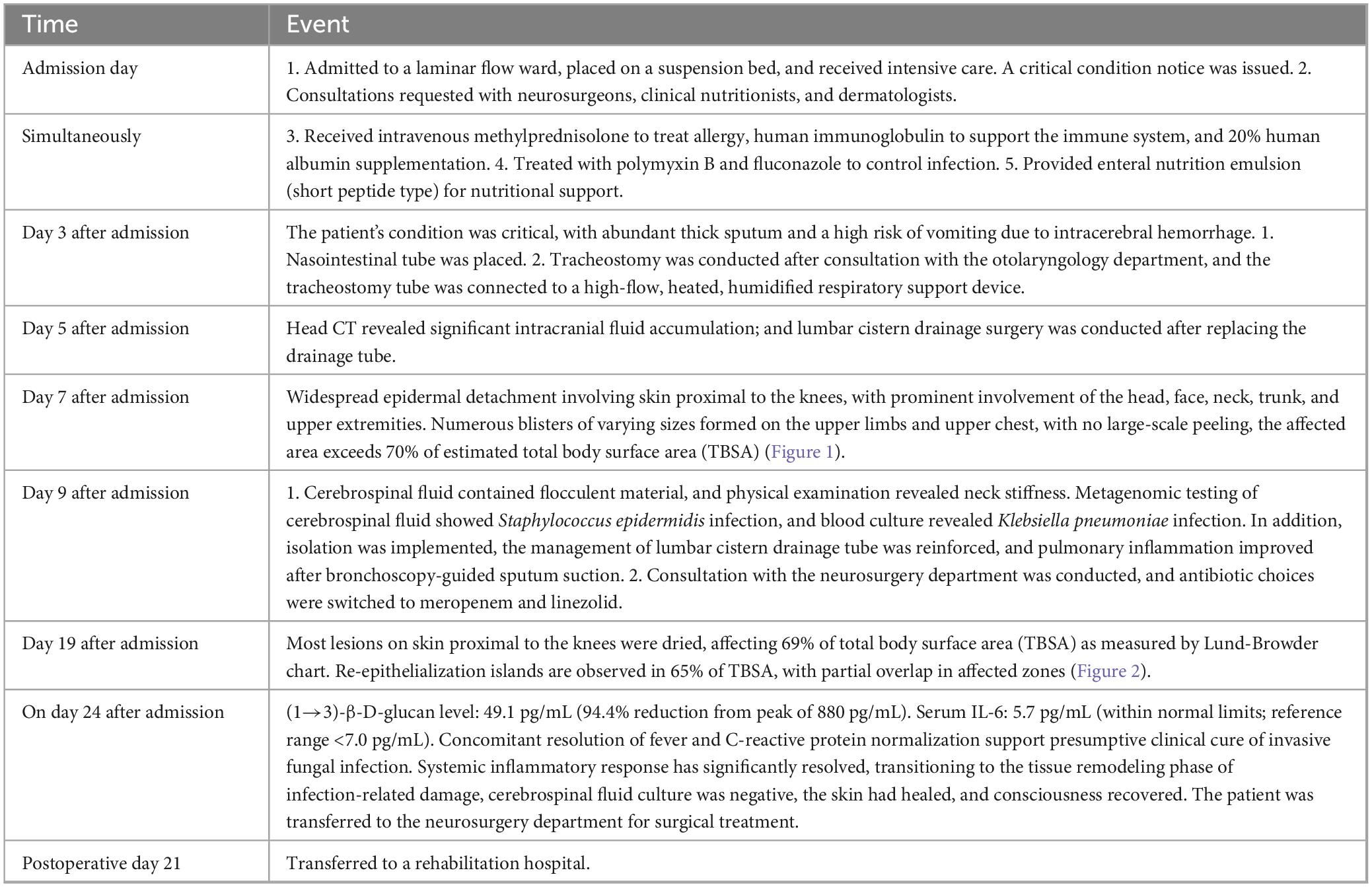

Table 1 details the comprehensive therapeutic course from hospital admission through disease stabilization and skin lesion healing until transfer to a rehabilitation hospital at 21 days post-neurosurgical intervention.

3 Nursing care

3.1 Prevention and control of respiratory infections

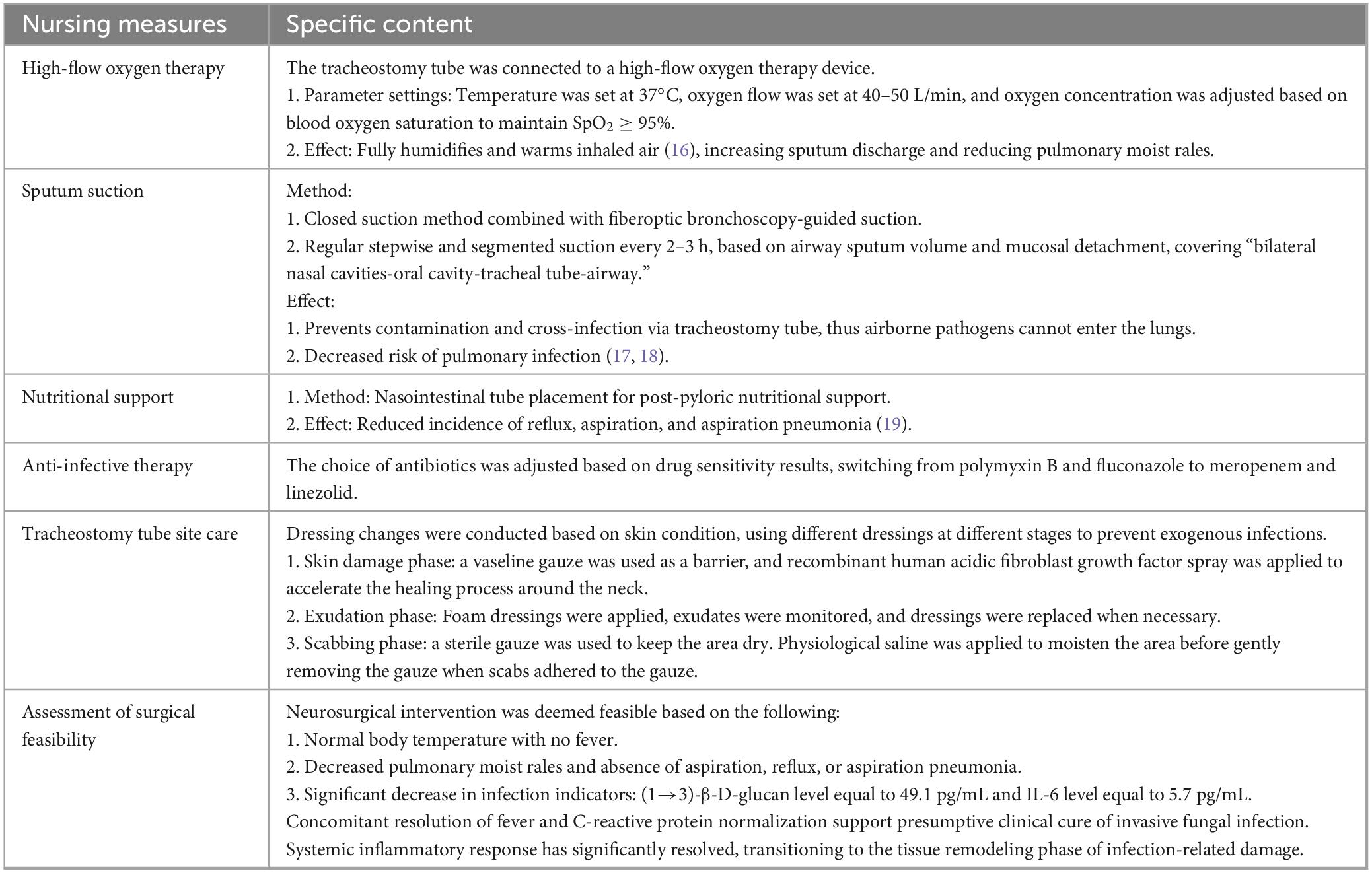

The patient’s condition was critical, with abundant and thick sputum, a history of intracerebral hemorrhage, a prolonged disease course, and a high risk of vomiting. The patient underwent tracheostomy after admission. Postoperatively, the airway was directly exposed to the external environment, compromising its integrity and continuity, which significantly increased the risk of lower respiratory tract infections, mortality, and disability (6). Studies have shown (7) that in patients with severe disease and impaired immune response, the incidence of pulmonary infection following tracheostomy can be as high as 43.6%. Therefore, effective management of the airway is particularly critical after tracheostomy. The key nursing measures are as follows (Table 2).

3.2 Prevention and control of intracranial infection

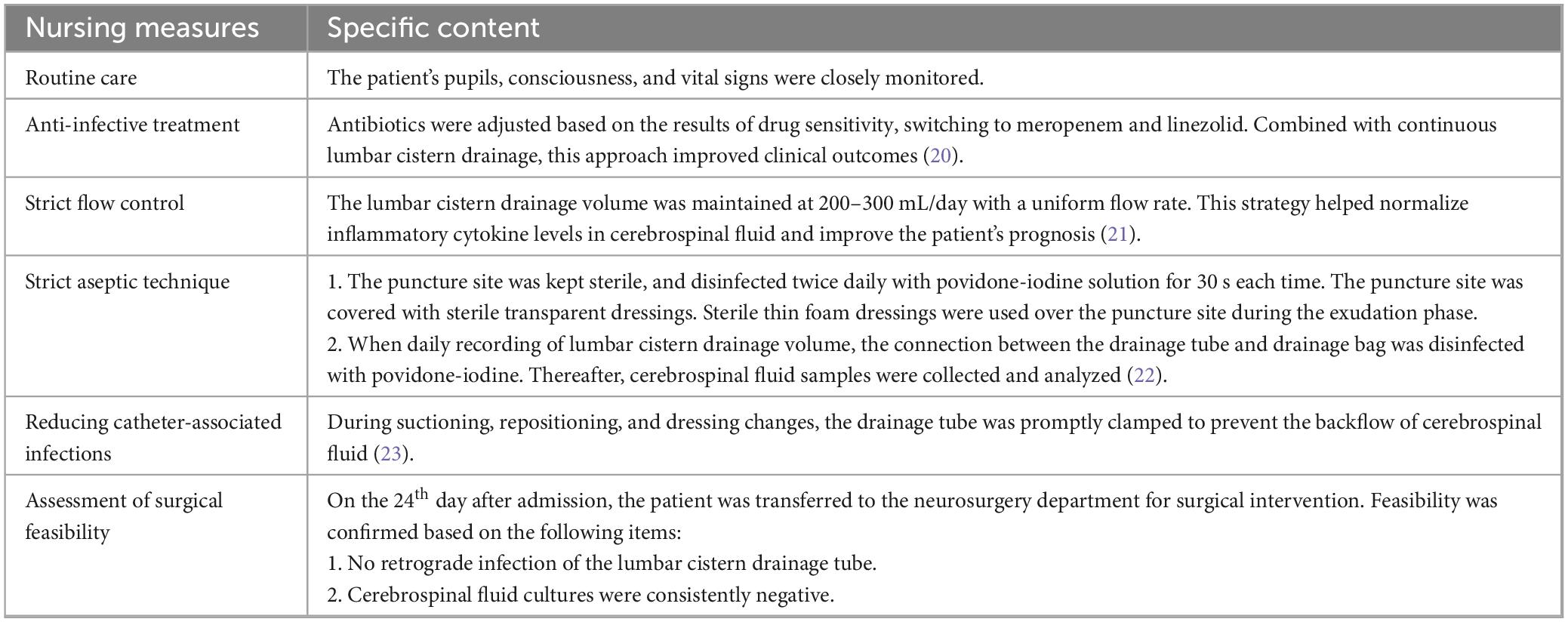

The primary nurse observed white flocculent material in the lumbar cistern drainage fluid on the second day after admission and promptly reported it to the physician. Cerebrospinal fluid was collected for metagenomic testing, which indicated Staphylococcus epidermidis infection. Intracranial infection was suspected after consultation with the attending physician and neurosurgeons. The lumbar cistern drainage puncture tube was replaced, and continuous drainage was maintained, which effectively treated intracranial infection (8). The key nursing measures were as follows (Table 3).

3.3 Prevention and control of skin lesion infection

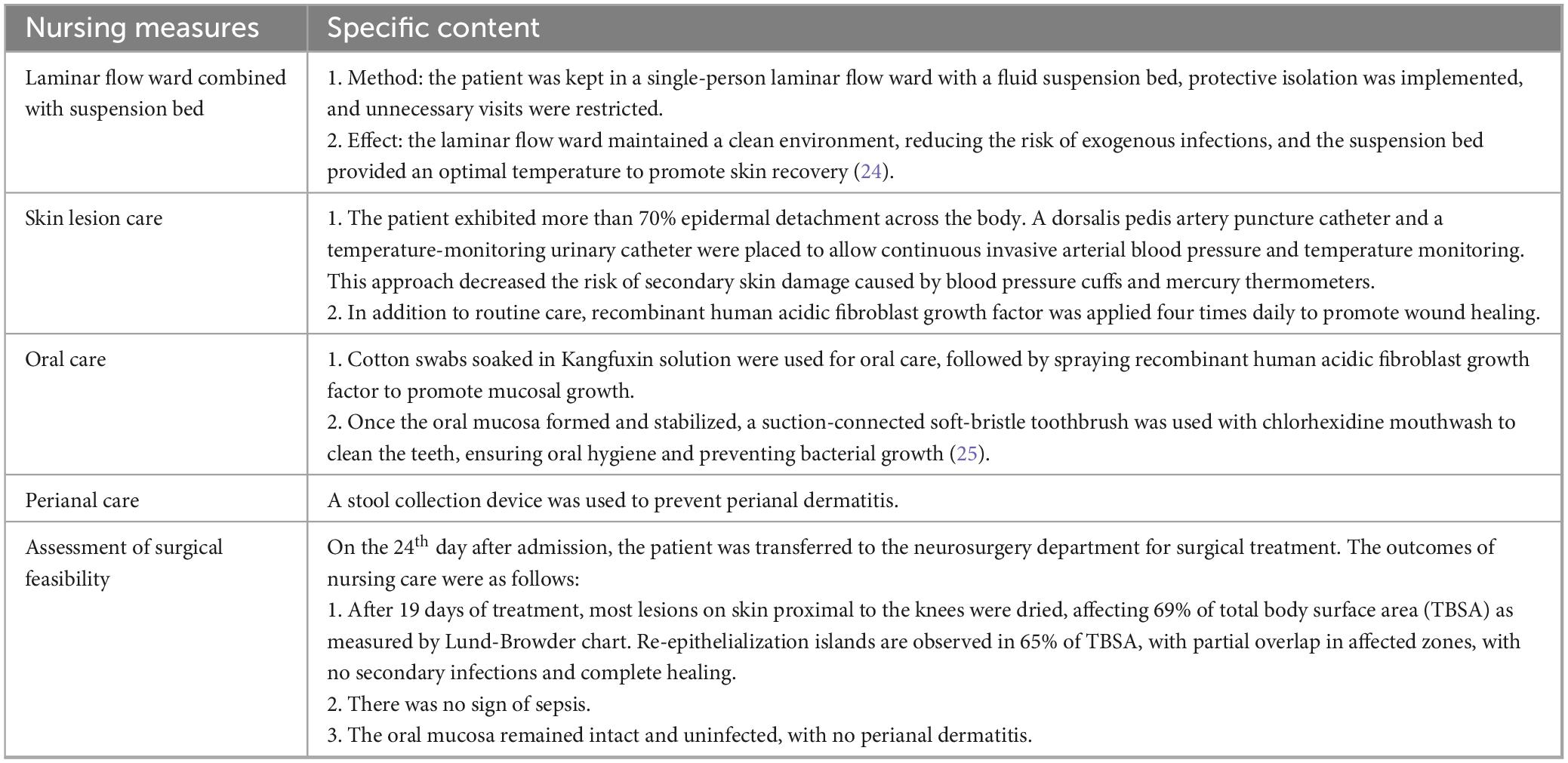

Patients with TEN-type drug eruptions are critically ill, with the rapid onset of extensive epidermal detachment and exfoliation. A larger affected skin area is associated with a higher mortality rate (9). Damage to the skin barrier is a primary source of sepsis and bloodstream infections, directly affecting the length of hospital stay and clinical outcomes (10). The patient in this report exhibited epidermal detachment on more than 70% of the body surface. The management of skin lesions was directly linked to the patient’s prognosis. The key nursing measures were as follows (Table 4).

3.4 Nutritional management

The combined effects of fever, infection, exfoliative dermatitis, and other factors make effective nutritional support critically important for the patient. Concurrently, severe hypoproteinemia may exacerbate cerebral edema, resulting in elevated ICP. For critically ill comatose patients who are unable to eat orally, enteral nutrition support should be prioritized once gastrointestinal function allows, ideally initiated within 24–48 hours of onset (11). Studies have shown (12) that appropriate nutritional support can decrease the risk of postoperative complications among patients with intracerebral hemorrhage and promote immune tolerance and recovery. Moreover, nutritional support plays a vital role in the healing of skin lesions (13). On admission, the patient underwent a nutritional risk screening, which suggested a high risk (NRS2002 score of 5). A nasointestinal tube was placed, and post-pyloric nutritional support was implemented to maintain gastrointestinal function and lower the risk of abdominal distension, nutrient retention, reflux, aspiration, and aspiration pneumonia. Studies have also indicated (8) that the body primarily absorbs proteins in the form of short peptides. Short peptides are short-chain peptides with a size between amino acids and whole proteins. They possess high caloric value, rapid absorption, complete utilization, and no consumption of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Therefore, the clinical nutrition team recommended enteral nutrition emulsion (short peptide type) at 500 mL per bag, three bags per day (1,500 mL total). The initial feeding rate was 20 mL/h and gradually increased to 60 mL/h if tolerated, ensuring adequate nutrition intake. The patient’s skin lesions healed without reflux, aspiration, or aspiration pneumonia. The NRS2002 score improved to 3, and the patient with his nasointestinal tube was transferred to the neurosurgery department for surgical intervention.

4 Discussion

In managing this patient with ICH complicated by TEN, the primary nurse employed advanced health assessment techniques to identify a high risk of infection as the principal nursing diagnosis. This determination was based on the convergence of three pathophysiological vulnerabilities: compromised integumentary barriers due to TEN-induced epidermal detachment, impaired immunological defenses associated with systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and the presence of invasive therapeutic devices, including a tracheostomy and lumbar drain. To mitigate the risk of systemic sepsis, a targeted nursing protocol was implemented across four domains. In respiratory management, high-flow oxygen therapy was used to maintain optimal inspired gas temperature and humidity. A timed, stepwise, segmental suctioning technique was applied to minimize contamination of the tracheostomy tube, reduce cross-infection, and prevent pathogen entry into the lungs. Given the patient’s prolonged bed rest and limited repositioning ability, a bedside nasoenteral tube was inserted for post-pyloric feeding to prevent gastroesophageal reflux and aspiration pneumonia. Antibiotic therapy was escalated from polymyxin B and fluconazole to meropenem and linezolid based on antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Tracheostomy site lesions were managed with phase-specific dressings tailored to denudation, exudation, or crusting phases to prevent exogenous infection. For intracranial infection control, meticulous care of lumbar cisternal drainage was maintained to prevent retrograde infection. In collaboration with neurosurgery and neurology teams, drainage flow was strictly regulated at 200 to 300 mL per day with a uniform velocity, under continuous monitoring of pupils, consciousness, and vital signs. Strict aseptic technique was enforced, and any abnormal drainage prompted immediate specimen collection and clinician notification for dynamic reassessment. In terms of skin management, site- and stage-specific care protocols were applied to all lesions, including those in the oral and perineal regions. To minimize skin trauma while facilitating essential monitoring, a dorsalis pedis arterial catheter and a thermistor-tipped urinary catheter were secured using zero-tension fixation, enabling continuous invasive arterial pressure and core temperature monitoring. A fecal management system was used to prevent perianal dermatitis. Nutritional support was initiated early and progressively increased under the guidance of a dietitian. Administration of 500 mL of short-peptide-based enteral emulsion, given as 1,500 mL per day in three divided doses, provided high-calorie, ATP-sparing nutrition with rapid absorption. Serial NRS-2002 scores improved from 5 to 3. Through synchronized multidisciplinary collaboration and proactive nursing intervention, the patient underwent ventriculoperitoneal shunting on day 24 and was transferred to a rehabilitation facility on day 45 post-admission. This integrated approach enhanced therapeutic efficacy, accelerated recovery, and optimized prognosis.

5 Conclusion

The nursing care of patients with intracerebral hemorrhage complicated with severe TEN-type drug eruptions is highly challenging and demands a high level of precision. Scientific and systematic management plays a major role in the recovery of such patients. To address this, future initiatives should advance toward intelligent nursing systems, such as the development of AI-powered early warning models capable of detecting incipient signs of infection through automated skin imaging analysis, thereby enabling rapid, evidence-based interventions (14). Studies have shown (15) that up to 65% of TEN survivors suffer from the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), including depression and anxiety. Psychological care was not emphasized during the patient’s stay in our department, and family members were only allowed to encourage the patient through video calls. Psychiatry and psychology specialists should evaluate and address the psychological state of such patients and administer medications when necessary. We recommend formal psychiatric evaluation using ICU-specific psychometric scales, supplemented by virtual reality (VR) therapy to alleviate isolation-induced distress, with pharmacotherapy initiated when indicated. Furthermore, consolidating neurocritical and burn care expertise could establish a goal-directed, stepwise care pathway: neuroprotection → systemic inflammation control → wound regeneration → neurological rehabilitation. This integrated approach warrants further investigation as a potential strategy to expand therapeutic windows and improve survival prospects in such critically complex cases.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the ethics review board of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (No. KY2024-1104-01). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

DZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review and editing. QZ: Writing – review and editing. HL: Writing – review and editing. WL: Writing – review and editing. PC: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Mhaidat N, Al-Azzam S, Banat H, Jaber J, Araydah M, Alshogran O, et al. Reporting antimicrobial-related adverse drug events in Jordan: An analysis from the vigibase database. Antibiotics (Basel). (2023) 12:624. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12030624

2. Heuer R, Paulmann M, Annecke T, Behr B, Boch K, Boos A, et al. S3 Guideline: Diagnosis and treatment of epidermal necrolysis (Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis) - part 1: Diagnosis, initial management, and immunomodulating systemic therapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. (2024) 22:1448–66. doi: 10.1111/ddg.15515

3. Paulmann M, Heuer R, Annecke T, Behr B, Boch K, Boos A, et al. S3 Guideline: Diagnosis and treatment of epidermal necrolysis (Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis) - Part 2: Supportive therapy of en in the acute and post-acute stages. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. (2024) 22:1576–93. doi: 10.1111/ddg.15516

4. Zhao L, Liu Y, Jiang Q, Cai L. Nursing care of a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome. Zhonghua Hu Li Za Zhi [Chinese Journal of Nursing]. (2023) 58:1629–34. doi: 10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2023.13.015

5. Charlton OA, Harris V, Phan K, Mewton E, Jackson C, Cooper A. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Steven-Johnson syndrome: a comprehensive review. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). (2020) 9:426–439. doi: 10.1089/wound.2019.0977

6. Han R, Gao X, Gao Y, Zhang J, Ma X, Wang H, et al. Effect of tracheotomy timing on patients receiving mechanical ventilation: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. (2024) 19:e0307267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0307267

7. Li S, Shi S, Yuan C, Lin W, Wang Y, Xie X, et al. Pulmonary infection in non-acute stroke patients undergoing tracheotomy:incidence and influencing factors. J Nursing Sci. (2023) 38:30–43. doi: 10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2023.08.030

8. Wang Y, Li Y, Li Y, Li H, Zhang D. Comparisons between short-peptide formula and intact-protein formula for early enteral nutrition initiation in patients with acute gastrointestinal injury: A single-center retrospective cohort study. Ann Transl Med. (2022) 10:573. doi: 10.21037/atm-22-1837

9. Seminario-Vidal L, Kroshinsky D, Malachowski S, Sun J, Markova A, Beachkofsky T, et al. Society of dermatology hospitalists supportive care guidelines for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2020) 82:1553–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.066

10. Surowiecka A, Barańska-Rybak W, Strużyna J. Multidisciplinary treatment in toxic epidermal necrolysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:2217. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20032217

11. Chen SP, Tan LP, Zhang N. Nursing care of a patient with post-intracerebral hemorrhage surgery complicated by severe exfoliative dermatitis. Zhonghua Hu Li Za Zhi [Chinese Journal of Nursing]. (2016) 51:759–62. doi: 10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2016.06.027

12. Intensive Care Committee of Chinese Nursing Association, Beijing Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Nursing Group. Expert consensus on enteral feeding nursing for patients with severe neurological diseases. Chin J Nursing. (2022) 57:261–4. doi: 10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2022.03.001

13. Hanson L, Bettencourt A. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: A guide for nurses. AACN Adv Crit Care. (2020) 31:281–95. doi: 10.4037/aacnacc2020634

14. Fujimoto A, Iwai Y, Ishikawa T, Shinkuma S, Shido K, Yamasaki K, et al. Deep neural network for early image diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. (2022) 10:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.09.014

15. O’Reilly P, Kennedy C, Meskell P, Coffey A, Delaunois I, Dore L, et al. The psychological impact of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis on patients’ lives: A critically appraised topic. Br J Dermatol. (2020) 183:452–61. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18746

16. Guo R, Sun Z, Wang Y, Wang Y. Application of high-flow humidified oxygen therapy in patients with tracheotomy and non-mechanical ventilation. Chin Crit Care Med. (2021) 33:1133–5. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn121430-20210425-00104

17. Wang S, Lu H, Zhang Y, Ma C, Zeng D, Si Y, et al. Application of timed, step-by-step and segmented sputum suction in airway management of patients with inhalation injury. Chin J Mod Nursing. (2020) 26:4171–5. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn115682-20200507-03183

18. Chen X, Sun X. Clinical application of closed suction combined with fiberoptic bronchoscopy in pulmonary infection after cardiac surgery. Chin J Nosocomiol. (2019) 29:3804–8. doi: 10.11816/cn.ni.2019-191108

19. Blakeman T, Scott J, Yoder M, Capellari E, Strickland S. Aarc clinical practice guidelines: Artificial airway suctioning. Respir Care. (2022) 67:258–71. doi: 10.4187/respcare.09548

20. Zhou M, Liang R, Liao Q, Deng P, Fan W, Li C. Lumbar cistern drainage and gentamicin intrathecal injection in the treatment of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae intracranial infection after intracerebral hemorrhage craniotomy: A case report. Infect Drug Resist. (2022) 15:6975–83. doi: 10.2147/idr.S378753

21. Qian M, Chen X, Zhang L, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Wang X. In situ bone Flap” combined with vascular pedicled mucous flap to reconstruction of skull base defect. World J Clin Cases. (2023) 11:7053–60. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i29.7053

22. Miao X, Luo X, Fu Z, Wang J, Zhao S, Ding L, et al. Prevention strategy for intracranial infection related to external cerebro-spinal fluid drainage tube based on evidence summary. Chin J Infect Control. (2024) 23:1070–6. doi: 10.12138/j.issn.1671-9638.20246123

23. Li Y, Ma Q. Application of individual fine management in patients with lumbar cistern drainage. Chin Nursing Res. (2021) 35:2627–9. doi: 10.12102/j.issn.1009-6493.2021.14.040

24. Cai Z, Xu J, Xu Z. Effects of air-fluidized bed combined with special wound nursing on wound recovery in burn patients after plastic skin grafting. Chin J Aesth Med. (2024) 33:169–72. doi: 10.15909/j.cnki.cn61-1347/r.006421

Keywords: intracerebral hemorrhage, toxic epidermal necrolysis, infection, nursing, lumbar cistern drainage

Citation: Zhang DD, Zhang QP, Li HH, Lai W and Chen PY (2025) Nursing care for a patient with intracerebral hemorrhage complicated with toxic epidermal necrolysis: a case report. Front. Med. 12:1587979. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1587979

Received: 27 March 2025; Accepted: 09 June 2025;

Published: 18 July 2025.

Edited by:

Zhenhua Chen, Jinzhou Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Rohadi Muhammad Rosyidi, University of Mataram, IndonesiaXu Zhang, Zhejiang Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, China

Copyright © 2025 Zhang, Zhang, Li, Lai and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pingyun Chen, MTcxMjkzNTI5MkBxcS5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Doudou Zhang

Doudou Zhang Qiuping Zhang†

Qiuping Zhang† Pingyun Chen

Pingyun Chen