Abstract

Cannabinoid subtype 1 receptors (CB1Rs) are an important class of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) belonging to the endocannabinoid system. CB1Rs play a crucial modulatory role in the functioning of other neurotransmitter systems and are involved in a wide range of physiological functions and dysfunctions; thus, they are considered one of the most important targets for drug development, as well as diagnostic purposes. Despite this, only a few molecules targeting this receptor are available on the pharmaceutical market, thus emphasizing the need to gain a deeper understanding of the complex activation pathways of CB1Rs and how they regulate diseases. As part of this review, we provide an overview of pharmacological and imaging tools useful for detecting CB1Rs. Herein, we summarize the derivations of cannabinoids and terpenoids with fluorescent compounds, radiotracers, or photochromic motifs. CB1Rs’ molecular probes may be used in vitro and, in some cases, in vivo for investigating and exploring the roles of CB1Rs together with the starting point for the development of CB1R-targeted drugs.

1 Introduction

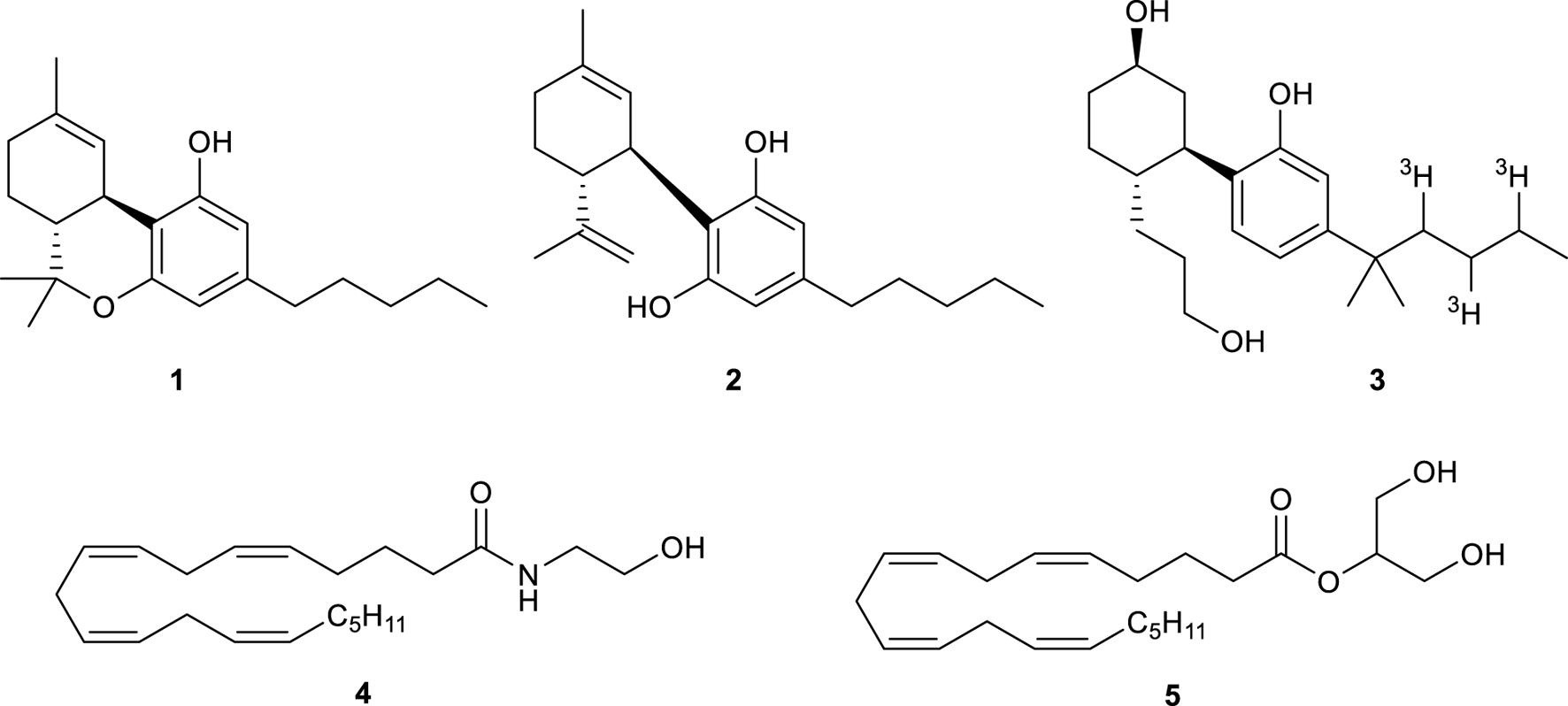

Since the dawn of civilization, Cannabis sativa L. has been used in a multitude of different ways for many purposes, from a recreational drug to medical uses, as well as for industrial goals including food, textile, paper, building, and energy industries, which have proven hemp to be an attractive solution for synthetic economies. (Abedi and Sahari, 2014; Alexander, 2016; Appendino, 2020; Finnan and Styles, 2013; Garcia-et al., 1998; Rehman et al., 2013). Recently, several studies have demonstrated that cannabis has positive effects on a wide range of health conditions (Campos et al., 2016). These outcomes are attributed to the active compounds found in the plant, thus prompting further research in the isolation and study of these secondary metabolites. Since the late 1960s, several compounds known to be present in cannabis have been isolated and characterized, including the psychoactive cannabinoid Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC or Δ9-THC, 1, Figure 1) and the non-euphoric cannabidiol (CBD, 2, Figure 1) (Iversen, 2018; Sholler et al., 2020). These compounds are now referred to as “major cannabinoids”, including other important ones like cannabigerol (CBG), cannabichromene (CBC), and cannabinol (CBN) (Pollastro et al., 2018; Anokwuru et al., 2022; Maioli et al., 2022). The two major phytocannabinoids THC and CBD already reached the approval by FDA for commercialization in different forms: Sativex®, a combination of THC and CBD, is used to treat spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis, and CBD has also been developed as a single active pharmaceutical ingredient known as Epidiolex®, drug of choice for the treatment of certain rare genetic forms of epilepsy. Additionally, the main phytocannabinoids are still being studied for their potential in treating various pathologies (mainly inflammatory diseases) both in vivo and in vitro (Baratta et al., 2022), as well as some of their derivatives, most notably the aminocannabinoquinone VCE-004.8, which has been granted orphan drug status by the FDA and EMA for the treatment of scleroderma (Caprioglio et al., 2021). More recently, Cannabis sativa showed to have a neuroprotective effect, resultant from its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties (Viana et al., 2022), while phytocannabinoids have been demonstrated to have potential anti-cancer properties. They induce cell death, inhibit cell migration and proliferation, decrease angiogenesis, and inhibit the invasiveness of cancer cells of, e.g., the lung, prostate, skin, breast, or brain (Hinz and Ramer, 2019; Kovalchuk and Kovalchuk, 2020; Tomko et al., 2020). Despite the very large number of phytocannabinoids isolated from cannabis (more than 150 different compounds) (Hanuš et al., 2016), the main biological activities observed during the study of this plant are to be attributed to these compounds which occur in considerably greater quantities compared to the so-called minor cannabinoids, regardless of the chemotype of the plant (Caprioglio et al., 2022).

FIGURE 1

Structure of Δ9-THC (1), CBD (2), tritiated CP 55,940 (3), AEA (4), and 2-AG (5).

In humans, the biological pathway regulated by cannabinoids is called endocannabinoid system (ECS). ECS is composed of two types of receptors, the CB1R and cannabinoid 2 receptor (CB2R), as well as enzymes that break down and synthesize their endogenous ligands (referred to as endocannabinoids) (De Petrocellis and Di Marzo, 2009). The CB1R was identified and characterized in the rat brain in 1988 and its location was confirmed using tritiated CP 55,940 (3, Figure 1) in 1990 (Herkenham et al., 1990). In 1992, the receptor was cloned and the DNA that encodes GPCRs was found (Matsuda et al., 1990). The CB2 receptor was instead discovered in 1993 and was found to be predominantly expressed in macrophages in the spleen (Munro et al., 1993). Once CB1R and CB2R have been discovered, anandamide (AEA, 4) and 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG, 5) were found to be the endogenous ligands that interact with these receptors (Figure 1) (Di Marzo et al., 2004).

As a regulator of a wide range of physiological processes, the ECS plays an important role in many disorders (Bisogno and Di Marzo, 2010). To gain a broader view of the ECS, it would be extremely valuable to develop high-sensitivity and high-throughput analytical tools. The use of small molecule probes might provide information regarding the spatial and temporal dynamics of cannabinoid receptor expression, as it has been demonstrated in recent years for some specific classes of enzymes (Chang et al., 2009; 2012; Tully and Cravatt, 2010). As a consequence, the development of small molecule probes that can recognize cannabinoid receptors is currently in the spotlight, since they may complement, and in some cases eliminate, some of the limitations of available antibodies (Grimsey et al., 2008). The purpose of this review is to provide an overview of the recent development of CB1R-specific probes: we will examine the various types of probes currently in use, describe how the chemistry of these molecules affects the effectiveness of these drugs, and examine where new probes and drugs may be developed in the future.

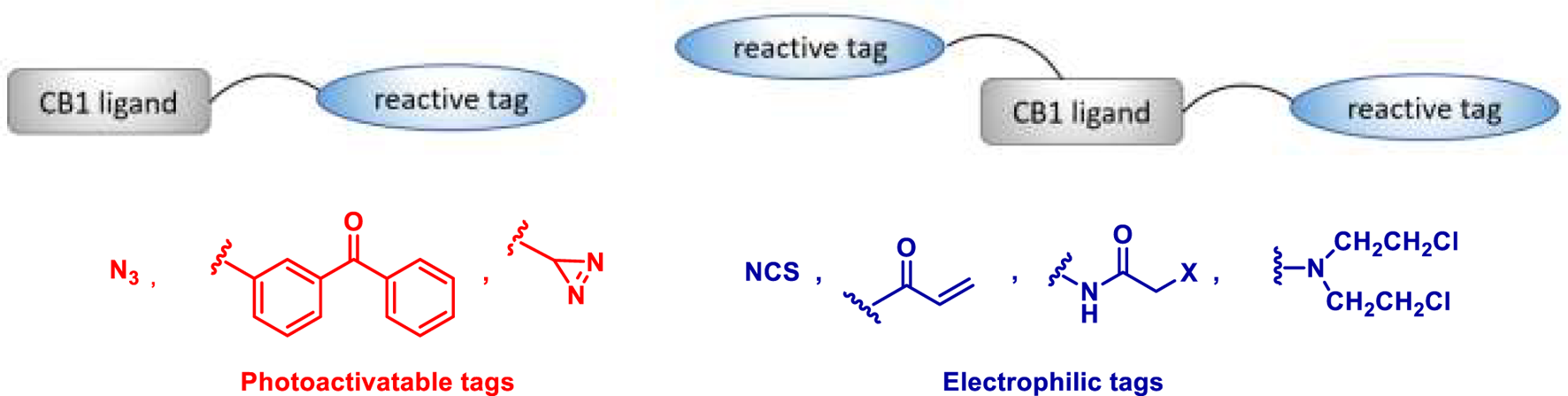

2 Covalent probes for CB1R

Covalent chemical probes have found widespread use as research tools and clinical agents. Their use ranges from probes that are metabolically incorporated into proteins, to probes for photoaffinity labelling of targets and electrophilic probes for activity-based protein profiling. In the contest of the CB1Rs, covalent probes have been designed by incorporating a reactive tag into a CB1R ligand such as 1 or 4 (Figure 2). One type of reactive tag is a chemically inert group (e.g., azides, benzophenones, or diazirine) which, upon UV irradiation, is converted into a highly reactive species able to react with any amino acid residue situated in its immediate environment. Alternatively, the reactive tag can be an electrophilic group (e.g., isothiocyanates, Michael acceptors, haloacetamides, or nitrogen mustards) able to target nucleophilic amino acids (e.g., lysine, histidine, and cysteine) situated at or near the binding site. When two reactive tags are attached to the ligands, then the corresponding bifunctionalized probes can potentially interact at two distinct sites within the CB1R-binding domains. In this section, we reviewed the covalent probes for the CB1Rs, classifying them as photoactivatable, electrophilic, and bifunctional probes.

FIGURE 2

General structures for covalent probes of CB1Rs.

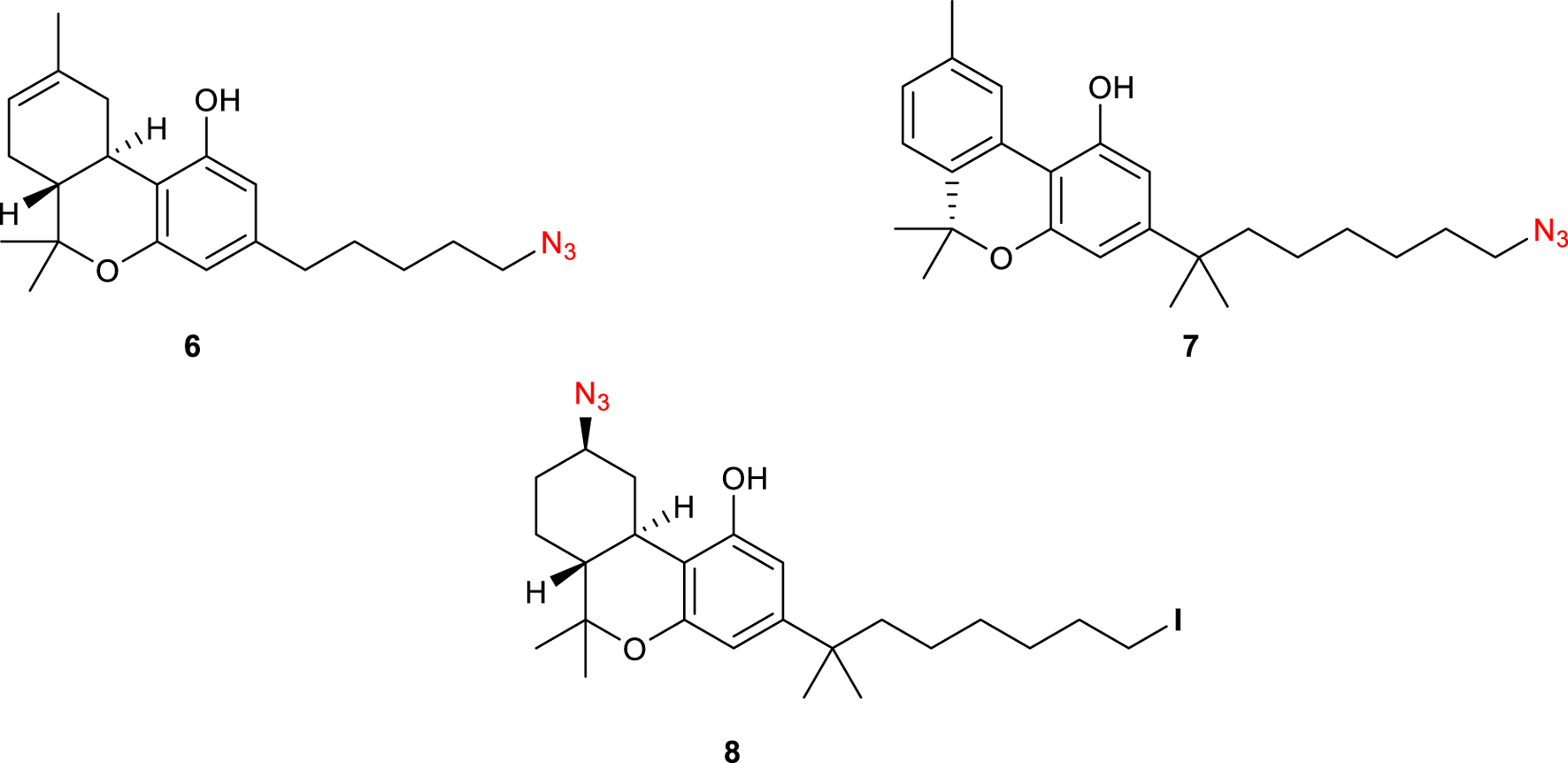

2.1 Photoactivatable probes

Photoaffinity probes (PAPs) are composed of a target-specific ligand and a photoactivatable functional group. When bound to the corresponding target proteins and activated with wavelength-specific light, PAPs generate highly reactive chemical species that covalently cross-link proximal amino acid residues. This process is better known as PAL (photo-affinity labelling) and is widely employed to identify cellular targets of biologically active molecules (Sumranjit and Chung, 2013). Many photoactivatable probes have been developed for CB1R, with 5′-Azido-Δ8-THC or AM91 6 (Figure 3), reported by Charalambous et al., being the first example of this kind (Charalambous et al., 1992). This ligand, with an aliphatic azido group attached to the terminal carbon of the alkyl side chain, showed a higher affinity for rat CB1R (rCB1R, Ki = 19 nM) over its parent prototype (−)-Δ8-THC (Ki = 35 nM). Moreover, equilibration of rat forebrain membranes with a 1 µM concentration of this compound, followed by UV-irradiation and washing to remove the unbound 6, resulted in an 85% decrease in the number of CB1R-binding sites of [3H]-CP 55,940, the standard radiolabeled CB1-agonist. Later on, the same group found that 7′-Azido-1′,1′-dimethylheptyl-Δ8-THC 7 (Figure 3) has a markedly improved binding affinity (Ki rCB1R = 0.4 nM) (Picone et al., 2002). Receptor binding studies revealed that 7 was effective at reducing the binding of [3H]-CP 55,940 by ca. 75% at 1 nM ligand concentration. This improvement was attributed to the lengthening of the C-3 alkyl side chain as well as the addition of the geminal dimethyl group. It must be noted that the photoreactive tag could also be installed in another region of the ligand, as reported for AM869 8 (Ki = 0.67 nM), although it showed limited selectivity between the two CBR-subtypes (Khanolkar et al., 2000).

FIGURE 3

Structure of photoactivatable probes AM91 (6), 7′-Azido-1′,1′-dimethylheptyl-Δ8-THC (7) and AM869 (8).

With the successful incorporation of the azido group as the reactive tag, a series of photoactivable probes radiolabeled have been designed by decorating the scaffold with 125I (Figure 4). Interestingly, while AM1708 9 showed a similar affinity for CB1R (Ki = 0.72 nM) to that of 8, compound 6-125I (10) displayed a high affinity for CB1R sites in both brain (Kd = 5.60 p.m.) and whole cell (Kd = 9.38 p.m.) systems.

FIGURE 4

Structures of photoactivatable probes AM 1708 (9), 6-125I (10), and AM993 (11).

Continuing this modification at C-3 position of Δ8-THC, compound AM993 11 bearing an adamantyl group with a photoactivatable azido-group was synthesized (Figure 4) (Ogawa et al., 2015). This compound was found to act as an agonist of CB1R (EC50 = 2.4 nM) whereas showing a negligible response at CB2R; moreover, it showed high affinity to CB1R with 2-fold and 6-fold selectivity over human and mouse CB2R (Ki CB1R = 4.4 nM). Covalent labelling yielded a 67% decrease in CB1R [3H]-CP 55,940 binding.

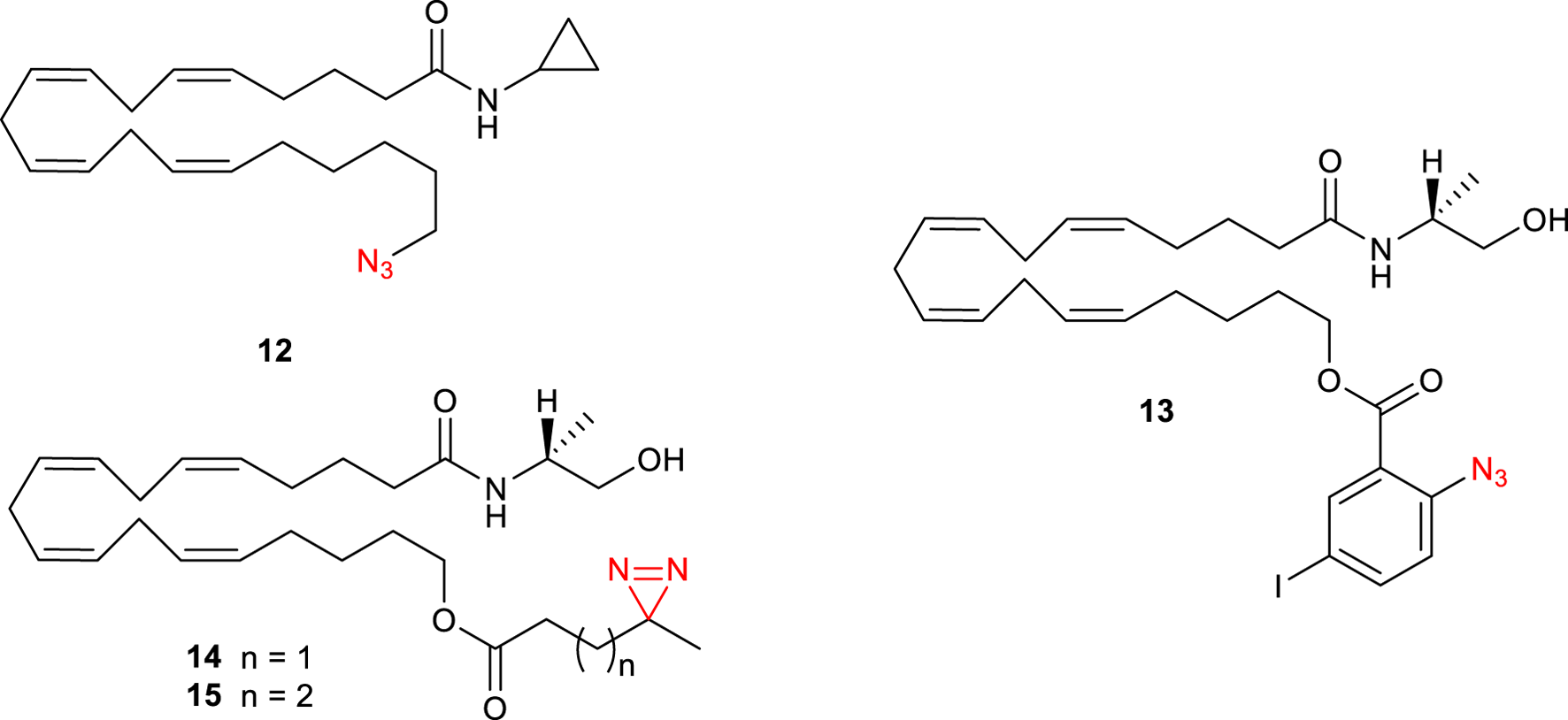

Since anandamide (4) is an endogenous polyunsaturated long-chain fatty acid agonist of CB1Rs, photolabeling probes based on this endocannabinoid have been designed (Li et al., 2005). Specifically, AM3661 12 (Figure 5) showed to possess CB1R-selectivity with a Ki value of 0.9 nM. Photolabeling experiments revealed a 68% reduction in [3H]-CP 55,940 (3) binding and therefore indicate that this ligand could be a useful probe for CB1R. Based on these results, Balas et al. synthesized a photoactivatable aryl azide probe 13 (Figure 5) (Balas et al., 2006). This compound showed a decreased affinity to human CB1R (hCB1R, Ki = 0.9 µM) when compared with the endogenous anandamide ligand (Ki = 0.07). These results suggest its potential use as a tool for the discovery of new potential endocannabinoid receptors. The same group further synthesized other anandamide-based photoaffinity probes (14-15, Figure 5) by replacing the 2-azido-5-idobenzoate group with short diazirine containing alkyl chains (Balas et al., 2009); however, no further studies on CB1Rs have been conducted with these compounds.

FIGURE 5

Structure of photoactivatable probes AM3661 (12) and the other anandamide-based photoaffinity probes 13-15.

2.2 Electrophilic probes

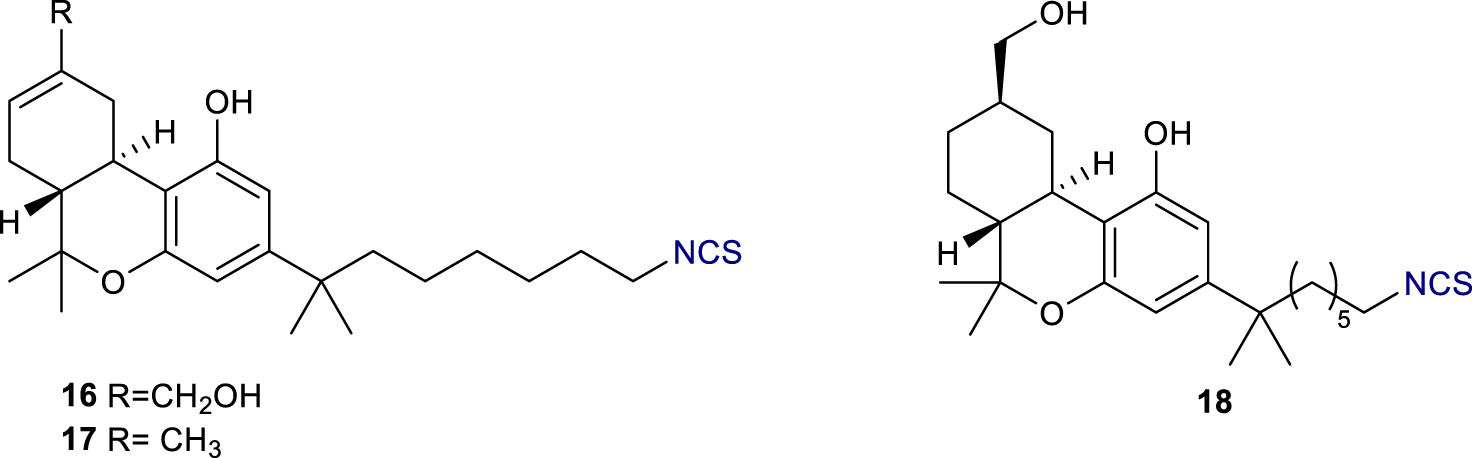

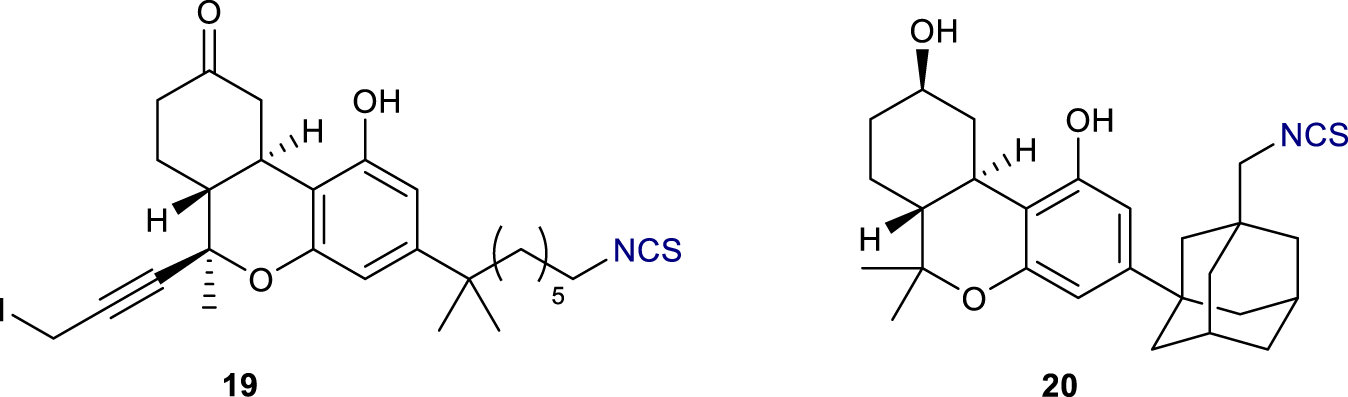

Electrophilic probes containing reactive tags are able to target nucleophilic amino acids present in the proximity of the binding site of the protein of interest. The targeted amino acids are usually cysteine, lysine, and histidine (all containing a nucleophile in the side chain), whereas the reactive tags are usually isothiocyanates or other electrophiles. These tags are often easy to install, thus many electrophilic probes for CB1Rs have been developed in the last decades. The first elecrophilic probes, reported by the Makriyannis group, were based on THC derivatives (Morse et al., 1995). (−)-11-OH-7′-NCS-1,1′-dimethylheptyl-Δ8-THC or AM708 16 and the analogue 17 bearing a methyl group instead of the hydroxymethyl at position 11 (Figure 6) exhibited potent binding at CB1R with similar IC50 values and comparable [3H]-CP 55,940 (3) displacement at 83%. Notably, the analogue of 16 in which the alkene has been reduced (compound AM841, 18) showed to behave as a highly potent hCB1R agonist (Ki = 9.05nM; EC50 = 0.94 nM) (Picone et al., 2005). Moreover, based on ligand-assisted protein structure analysis (LAPS), they identify a cysteine residue, C6.47 (355), within the transmembrane helix 6 of CB1R, as the key site for the covalent binding of 18. The ligand-receptor interaction was abolished when either C6.47 (355) was mutated to weaker or non-nucleophilic amino acid residues or the electrophilic isothiocyanate group on 18 was exchanged with non-electrophilic substituents.

FIGURE 6

Structures of electrophilic probes AM 708 (16), 17, and AM841 (18).

Another electrophilic probe based on a modification of THC has been reported by Chu et al. (Figure 7) (Chu et al., 2003). In this case, AM960 19, containing a propargyl iodide, displayed successful binding at rCB1R by occupying 50% of sites at 25 nM. In a similar fashion to AM993 11 (vide supra), the adamantyl C-3 derivative AM994 20 (Figure 7) showed high affinity to rCB1R (Ki = 3.0 nM) with 3- and 10-fold selectivity over human and mouse CB2R respectively; moreover, it displayed a 63% decrease in [3H]-CP 55,940 (3) binding at 30 nM.

FIGURE 7

Structure of electrophilic probes AM960 (19) and AM 994 (20).

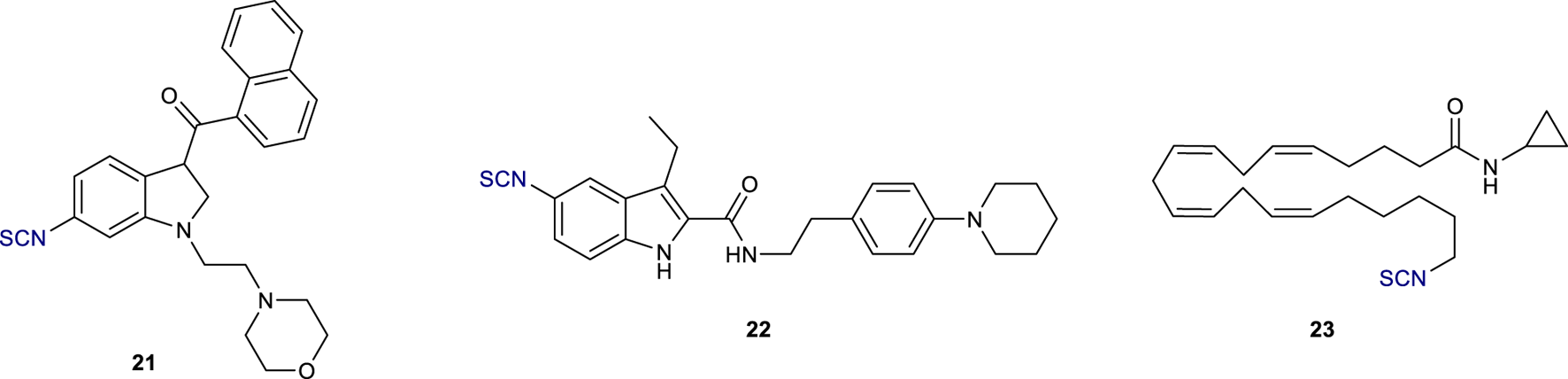

In 1996, a series of (aminoalkyl)indole isothiocyanates were reported as potential electrophilic affinity ligands (Yamada et al., 1996). Among them, compound 21 (Figure 8) showed to be a potent rCB1R agonist (EC50 = 1.1 µM); equilibration of rat brain membranes with 1 µM concentration of this compound resulted in a 70% loss of the specific binding of [3H]CP-55,940. More recently, Kulkarni et al. described the synthesis of the first electrophilic ligands designed to bind irreversibly to the CB1R allosteric site (Kulkarni et al., 2016). GAT100 22 (Figure 8) emerged as the most potent negative allosteric modulator (NAM) without significant inverse agonist activity; preincubation of HEK-293 cells with 100 nM concentration of 22 increased the specific binding of [3H]CP-55,940 at CB1R by over 2-fold. This novel covalent probe can therefore serve as a useful tool to elucidate CB1R allosteric ligand-binding motifs and to modulate the negative side effects of CB1R activation.

FIGURE 8

Structure of electrophilic probes 21, GAT100 (22), and AM 3677 (23).

Anandamide analogues with a reactive isothiocyanate functionality at the end of the hydrophobic tail were also reported as CB1R electrophilic probes (Janero et al., 2015); between them, AM3677 23 (Figure 8) exhibited high selectivity for rCB1R with a Ki value of 1.3 nM. LAPS studies demonstrated that this compound reacts with a cysteine residue located in transmembrane helix 6 of h CB1R, C6.47 (355), the same previously found in the ligand-binding profile of AM841 18. These data, therefore, confirmed the key role of this amino acid residue for receptor-ligand labelling in CB1R.

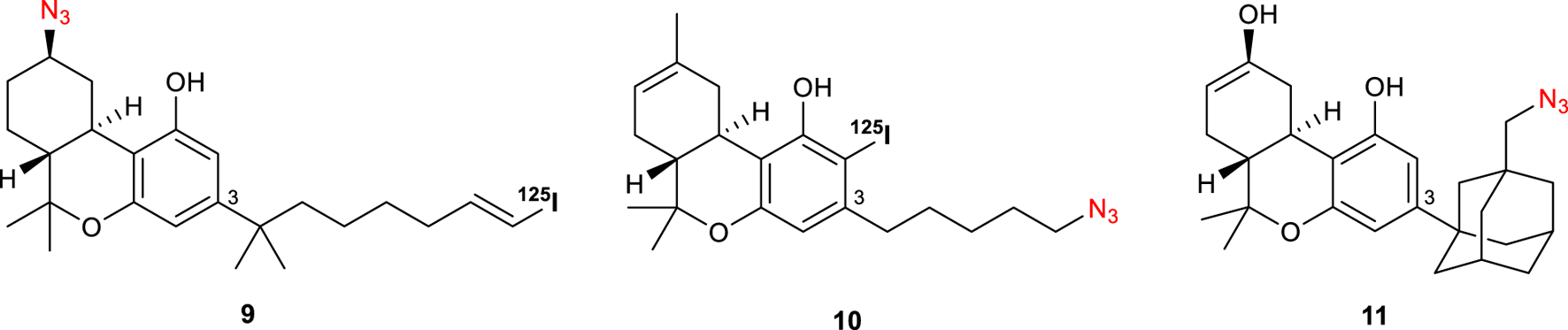

2.3 Bifunctional probes

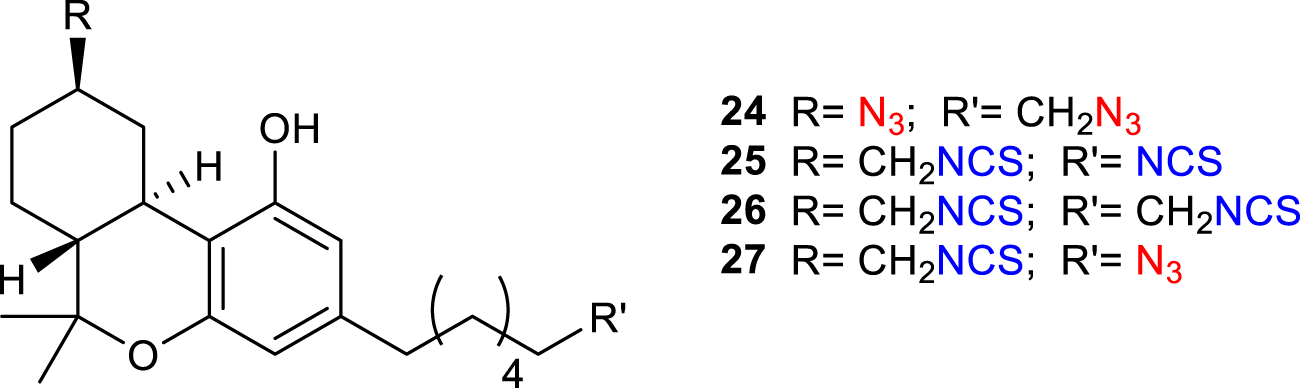

Bifunctional probes containing two electrophilic or two photoactivatable moieties (homobifunctional probes) or both of them (heterobifunctional probes) display the possibility to combine multiple imaging techniques creating a higher spatial resolution. AM859 24 (Figure 9) features two azide functionalities and showed excellent affinity to CB1R (Ki = 1.60 nM) despite being no selective between CB1- and CB2-receptors (Hamilton et al., 2021). Similarly, AM5823 25 (Makriyannis, 2014) and AM4099 26 (Zhou et al., 2017) are examples of homobifunctional probes containing two isothiocyanate groups, with the latter, reported by Zhou et al., showing a high affinity for hCB2R agonist, although no CB1R data of this molecule have been reported. AM5822 27 is instead a heterobifunctional ligand also containing an azide moiety for light activation (Makriyannis, 2014). Although most of these studies are preliminary, the potential of bifunctional probes to image the receptor at higher spatial resolution is becoming of growing interest.

FIGURE 9

Structure of bifunctional probes AM859 (24), AM5823 (25), AM4099 (26) and AM5822 (27).

3 Fluorescent probes

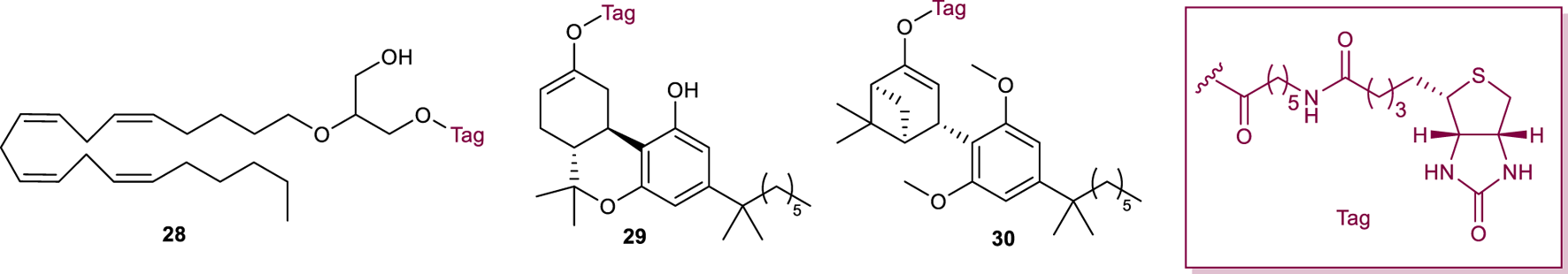

Fluorescently tagged small molecules have been widely used in the past decade as biological imaging tools as they offer the advantage to allow real-time monitoring of ligand-receptor interactions with high spatio-temporal precision (Briddon et al., 2011). Conjugation of a pharmacophore with a non-peptidic fluorescent tag can detrimentally change ligand-receptor affinity and therefore, a linker is generally required to separate the two entities (Stoddart et al., 2015). The composition and length of this linker (generally PEG or methylene chain), as well as the choice of the fluorophore, can also affect the physicochemical and photophysical properties of the resulting fluorescent conjugate; therefore, the development of fluorescently labelled ligands is particularly challenging. Within recent years, a plethora of fluorescent ligands targeting CB1R has been reported, mainly using biotin as target for the fluorophore. The addition of biotin to a ligand via a linker can, provide fluorescence, once the compound has docked with the target receptor, using fluorescent avidin conjugates. The biotinylated 2-AGE analogue 28 (Figure 10), showed moderate affinity to both human CB1R and was selected for in vitro imaging of CB1R (Martín-Couce et al., 2011). Biotinylated probes 29 and 30 (Figure 10), where the synthetic cannabinoid agonists HU210 and HU308, respectively, were conjugated to biotin via the free hydroxyl group, have also been successfully used for the visualization of CB1R in neurons and in different immune cell (Martín-Couce et al., 2012). However, biotin probes require a two-step labelling process and additional steps to block endogenous biotin. This does not make them suitable for flow cytometry clinical routine or tissue staining.

FIGURE 10

Structure of fluorescent probes 28-30.

To avoid these drawbacks, the cannabinoid agonist HU210 was coupled to the fluorescent tag Alexa Fluor 488 via a hexyl amide linker, generating the first fluorescent probe (31, Figure 11) with high affinity for CB1R (Ki CB1R = 27 nM) and selectivity over CB2R (Martín-Fontecha et al., 2018). The use of this ligand as a chemical tool for the identification of functional CB1R in human monocytes, T cells, and B cells was validated by multiplexed flow cytometry. This probe showed to be also suitable for the direct visualization of CB1R in tonsil tissues, allowing the in vivo identification of tonsil CB1R-expressing T and B cells.

FIGURE 11

Structure of fluorescent probes 31-32.

Chromenopyrazole compounds, containing a similar THC structure, were also used as scaffolds for the conjugation with different fluorophores (BODIPY-630/650, BODIPY-FL, and Cy5) generating fluorescent ligands that have been shown to have high affinity to cannabinoid reports (Figure 11). However, these compounds (i.e., Cy-chromenylpyrazole 32) showed higher affinity to CB2R over CB1R (pKi hCB1R = 5.26; pKi hCB2R = 7.83) (Singh et al., 2019).

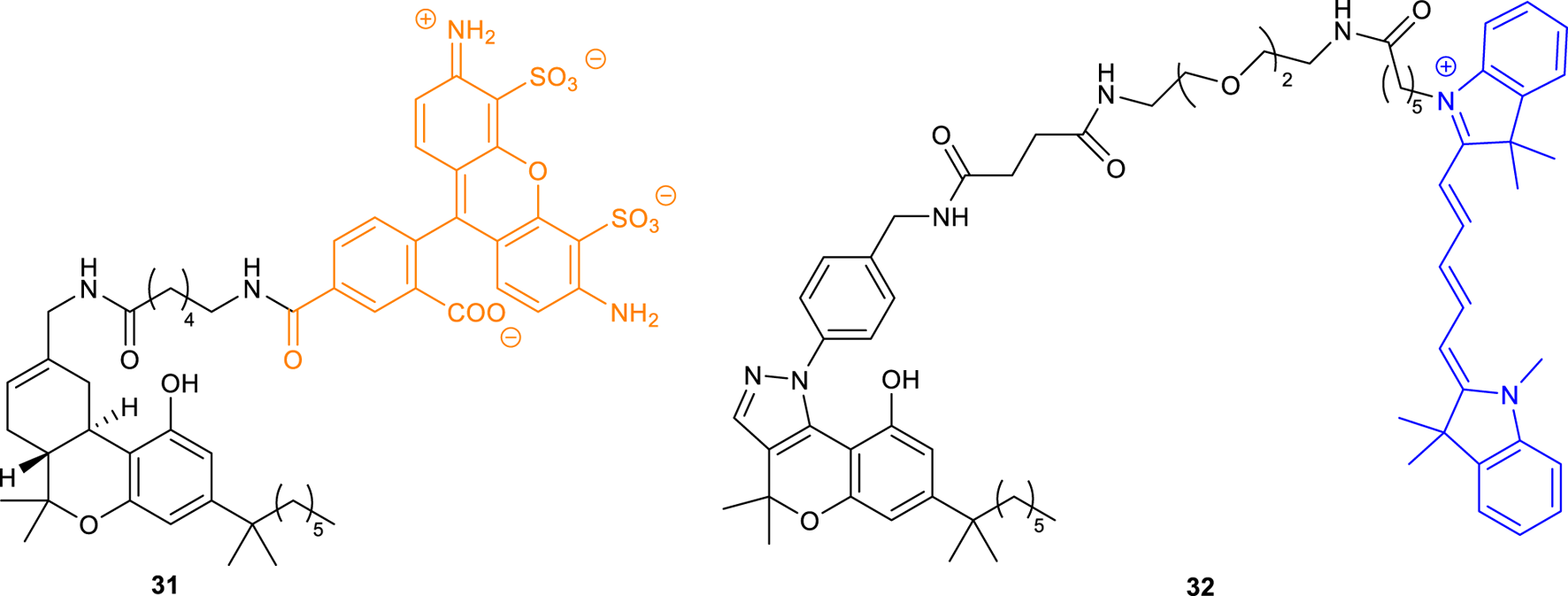

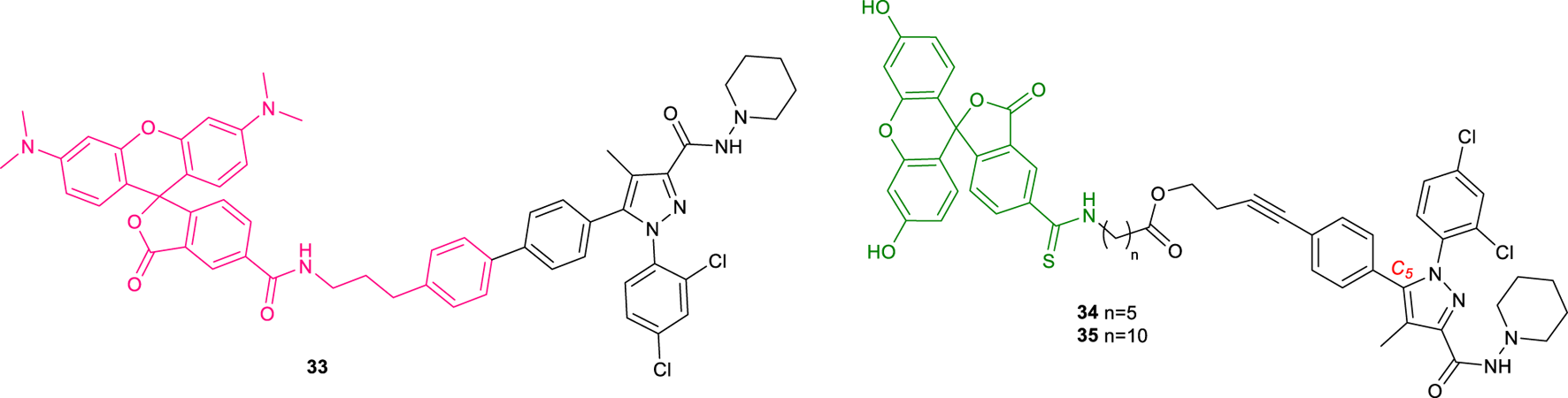

T117, a novel diarylpyrazole fluorescent ligand (33, Figure 12), was first reported by Daly et al. and derived by conjugation of the potent CB1R inverse agonist AM251, with a fluorescent tetramethylrhodamine group (5-TAMA) (Davenport and Daly, 2010). In ligand binding studies, AM251 competed with [3H]CP 55,940-labelled membranes to give a Ki of 0.8 nM. The addition of the 5-TAMA group significantly reduced the binding affinity of T117, providing only 10% displacement of [3H]CP 55,940 at 1 µM. However, at a lower concentration (0.3 µM), binding of T1117 to wild-type (WT) mouse mesenteric artery was observed, using 543 nm excitation (590 nm emission). This ligand also displayed binding to cannabinoid-like (GPR55) receptors through Ca++ response in HEK-293 cells. Nevertheless, a conflicting study proved that T1117 binds endogenous and recombinant CB1Rs with nanomolar affinity (Kd = 460 nM). Moreover, T1117 binding to CB1R is sensitive to the allosteric ligand ORG27569 and thus it is applicable to the discovery of new allosteric drugs (Bruno et al., 2014). In 2009 a study carried out by Grant and co-workers focused on the CB1R inverse agonist SR141716A, established the C5 position of its central pyrazole ring as the optimal site for fluorescent moiety linkage (Grant et al., 2019). Thus, CB1R fluorescent probes (34-35, Figure 12) based on C5 conjugation of two SR141716A analogues with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), were prepared. The affinity of the fluorescent probes 34 and 35 was then determined through radioligand competition binding assays at hCB1R. The affinity of the 17-atom linker congener 35 (Ki = 2.1 μM) was modest; however, compound 34 bearing a 12-atom linker was found to display a useful level of affinity for CB1R (Ki = 260 nM).

FIGURE 12

Structure of fluorescent probes 33-35.

4 18F-labeled PET ligands

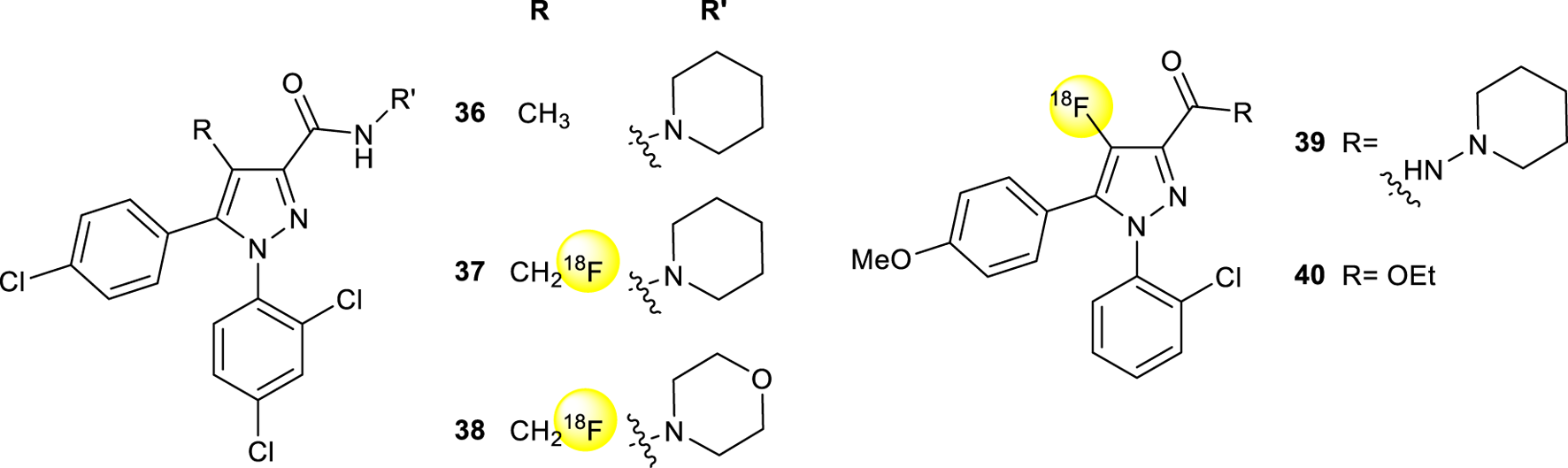

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a nuclear imaging technique that employs gamma rays to provide three-dimensional images that give information about the functioning of specific organs. PET is based on the detection of picomolar amounts of biological substances labeled with a short-lived positron-emitting radionuclide (tracer) sparing the biological system. This technique shows the advantage of being non-invasive, functional, and extremely sensitive (Li and Conti, 2010). Moreover, the PET probes have the same chemical structure as biomolecules and drugs, without altering their biological activity. 18F has a short half-life (109.8 min), making it the ideal radionuclide for routine PET imaging (Damont et al., 2013). Thanks to its exceptional sensitivity, PET is well suitable to measure relatively low concentrations of enzymes and receptors also in vivo considering that most neuroreceptor populations in the human brain are expressed in a range between 10–8 and 10–12 M (Lopresti et al., 2023). The first selective CB1R antagonist was rimonabant (36) (Rinaldi-Carmona et al., 1994), approved in Europe in 2006, to treat obesity but withdrawn from sale 2 years later by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) due to its manifest secondary effects and not being approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, some of its analogs have been synthesized and labeled with [18F] for PET imaging. Analogs of rimonabant showed activities on different and important biological targets, which makes them attractive for the development of new PET tracers (Gomes et al., 2020). In particular, two radiotracers [18F]SR144385 (37) and [18F]SR147963 (38, Figure 13) showed an appropriate regional brain distribution for cannabinoid receptors with a target ratio of 1.7 for [18F]SR147963 and 2.5 for [18F] SR144385 at 60 and 90 min post-injection, respectively (Mathews et al., 2000). Similar structures have been reported by Horti et al. in which the synthesis of two radiolabeled compounds named [18F]NIDA-42033 (39) and its ethyl ester derivative 40 have been described (Figure 13) (Katoch-Rouse and Horti, 2003). The radiochemical yields were in the range of 1%–6% and sufficient quantities with specific radioactivity greater than 2,500 mCi = mmol and radiochemical purity >95%.

FIGURE 13

Structure of rimonabant (36) and 18F radiolabeled pyrazole derivatives 37-40.

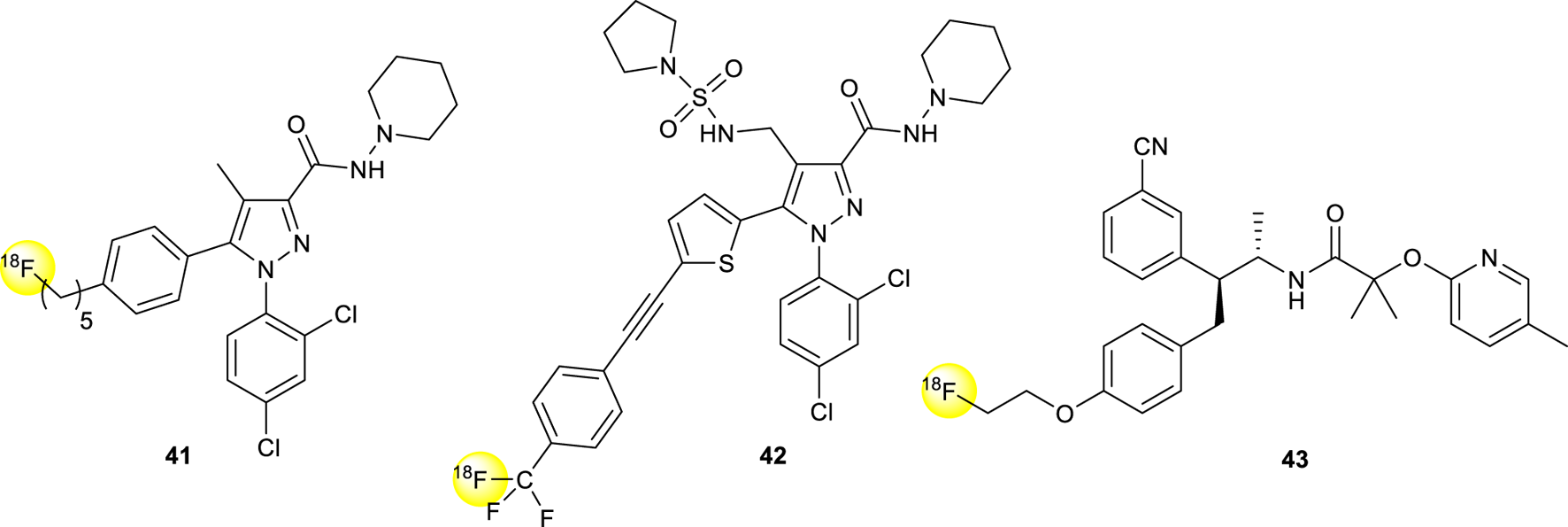

Another derivative named [18F]-O1302 (41, Figure 14) having a short carbon chain at the para position of the phenyl group ending with a [18F], showed high binding affinity (Ki 0.91 nM) and moderate lipophilicity after evaluation in mice (Mathews et al., 2000; Tobiishi et al., 2007).

FIGURE 14

Structure of 18F radiolabeled pyrazole derivatives 41-43.

The [18F] isotope-labeled CB1R inverse agonist DBPR211 (42, Figure 14) was synthesized, radiolabeled with halex exchange reaction, and analyzed for positron emission tomography scanning studies (Chang et al., 2019). After the purification, the compound was intravenously injected in mice showing a distribution percentage over 90-min scans among five regions of interest, including brain, heart, liver, thigh muscle, and kidney, lower than 1%, justifying itself as a peripherally CB1R antagonist.

[18F]MK-9470 (43, Figure 14) is a recent selective, high-affinity, inverse agonist (human IC50, 0.7 nM) for the cannabinoid CB1R developed for the imaging of the human brain (Burns et al., 2007). Autoradiographic studies in the rhesus monkey brain showed high specific binding in the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, caudate/putamen, hippocampus, substantia nigra, and globus pallidus. Positron emission tomography (PET) images in rhesus monkeys exhibited high brain uptake.

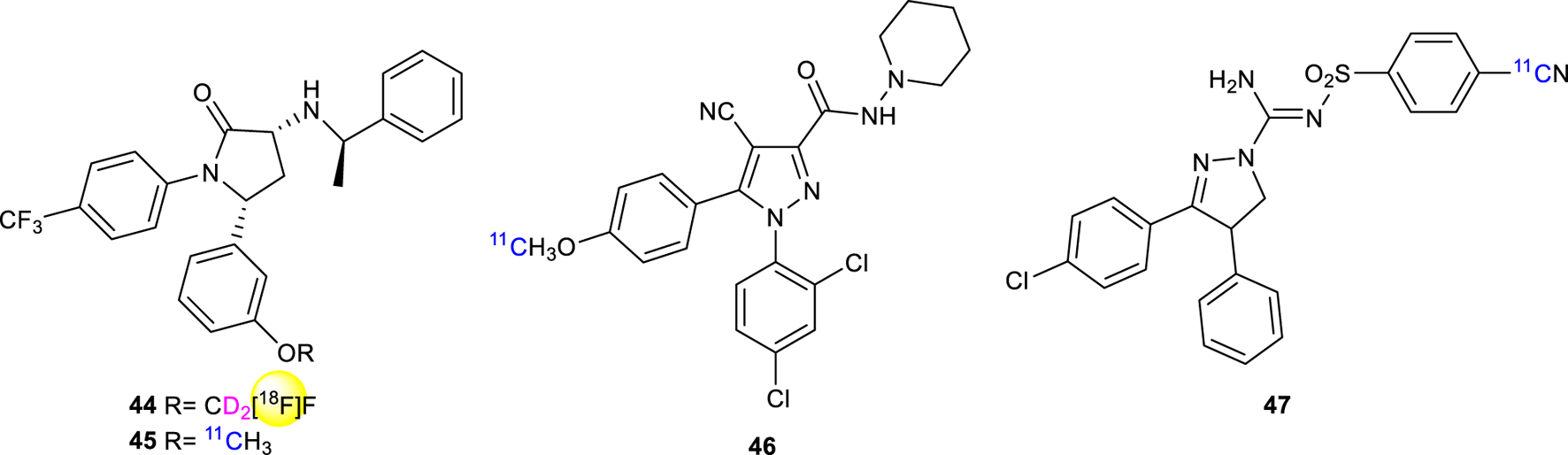

Donohue in 2008 (Donohue et al., 2008a) described the synthesis of [18F]FMPEP-d2 (44, Figure 15) having a superior performance of tracing compared with [11C]MePPEP (45, Figure 15), due to greater precision and accuracy in detecting significant differences in CB1R tracer uptake (Terry et al., 2010). 44 has been used to study abnormal levels of CB1R binding in alcohol abuse (Hirvonen et al., 2013) or neurological disorders (e.g., schizophrenia) (Jenko et al., 2012). In preclinical and clinical studies [18F]FMPEP-d2 has been used to image CB1R expression in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease (Takkinen et al., 2018).

FIGURE 15

Structure of 18F radiolabeled ligand 44 and 11C radiolabeled ligands 45-47.

5 11C-labeled PET ligands

11C-labeled ligands offer certain advantages compared to 18F-labeled compounds. The shorter half-life of 11C enables more syntheses to be carried out in a shorter period of time, using the same hot-cell. Additionally, the lower radiation-absorbed doses permit more PET scans to be conducted on each subject. However, the shorter half-life of 11C can create challenges in accurately quantifying radioligand kinetics or concentrations in plasma and the brain, especially when they are low. Today, 11C-OMAR (46, Figure 15) represents the most studied and promising CB1R radiolabeling agent for PET (Horti et al., 2006). In 2008 Donohue discovered and labeled 3,4-diarylpyrazoline derivatives as candidate radioligands for in vivo Imaging of Cannabinoid Subtype-1 using [11C]cyanide ion as labeling agent and evaluated as PET radioligands in cynomolgus monkeys (Donohue et al., 2008b). Compound 47 ((−)-3-(4-chlorophenyl)-N′-[(4-cyanophenyl)sulfonyl]-4-phenyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazole-1-carboxamidine) 11C-SD5024 (Figure 15) was found to get high-affinity and selectivity for binding to CB1R. The same compound has been studied for the kinetics in humans and evaluated in seven healthy subjects with compartmental modeling (Tsujikawa et al., 2014). The compound showed a Ki = 0.47 nM at an intermediate level among the five CB1R ligands and a lipophilicity of 3.79, which is appropriate for brain imaging together with a peak brain uptake of 1.5–3 standardized uptake value, slightly higher than that of 11C-OMAR.

The synthesis of [11C]MePPEP (45, Figure 15), a CB1R mixed inverse agonist and antagonist, has been first reported in 2008 to ameliorate previous CB1R ligands (Donohue et al., 2008b). The compound showed fairly high lipophilicity (LogD7.4 = 4.8) but still preserving high selectivity and affinity for the CB1R. It readily entered the monkey brain within 20 min displaying stable measurements of distribution volume within 90 min (Yasuno et al., 2008).

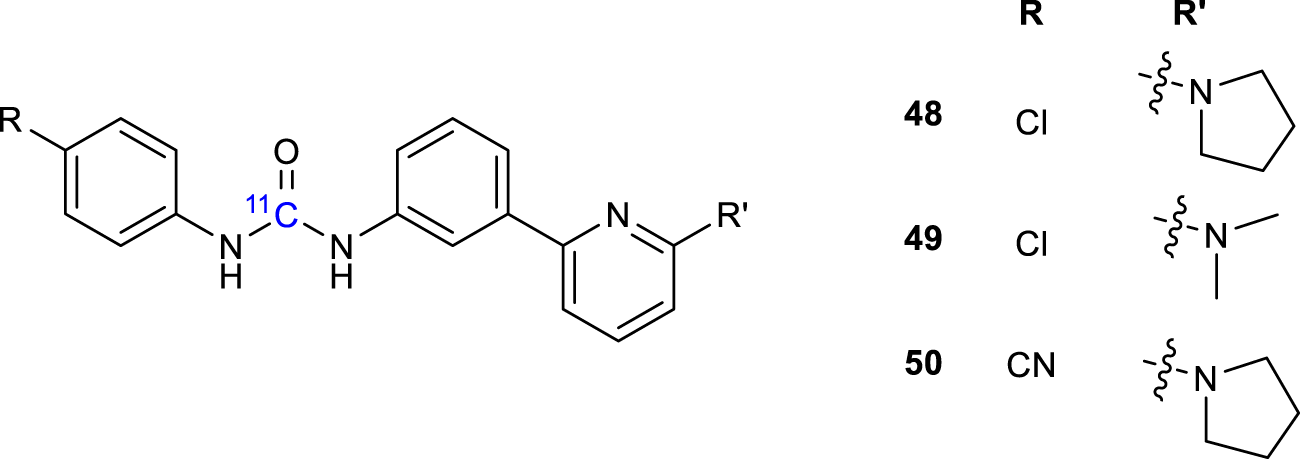

PSNCBAM-1 (1-(4-Chlorophenyl)-3-(3-(6-(pyrrolidin-1-yl) pyridin-2-yl)phenyl)urea) (48, Figure 16) was developed as a potent allosteric antagonist for CB1, able to reduce the appetite and body weight of rats. Other Several analogs were synthesized and radiolabeled using [11C]COCl2 and evaluated as PET ligands for CB1R imaging using in vitro and in vivo techniques (49-50, Figure 16) (Yamasaki et al., 2017). In particular, compound 49 showed a strong binding affinity for peripheral CB1R in an in vitro binding assay. PET imaging with showed considerable binding to peripheral CB1R in the mouse brown adipose tissue (BAT), suggesting that 49 is a promising PET imaging agent for further evaluating pathophysiological and biological processes mediated by peripheral CB1R.

FIGURE 16

Structure of 11C radiolabeled ligands 48-50.

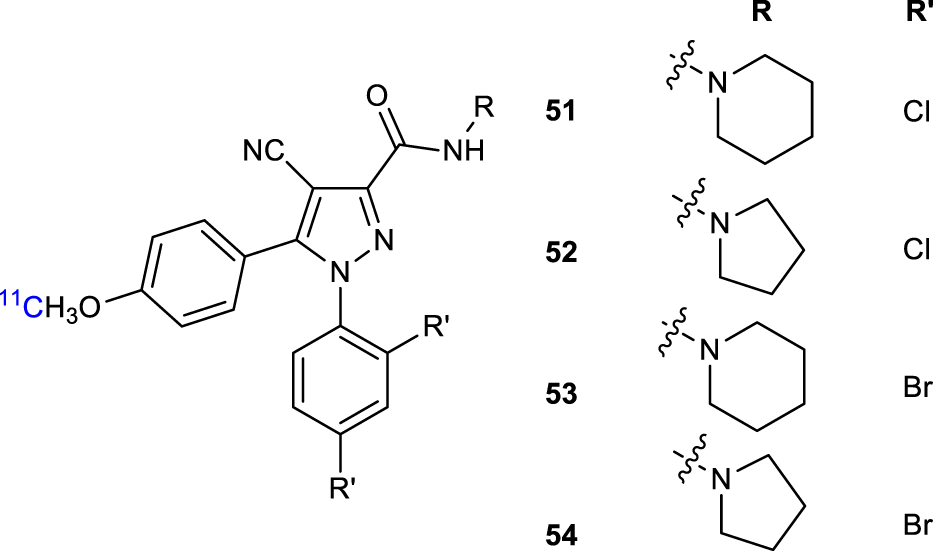

Gao et al. reported an alternative synthetic route to PET CB1R radioligands [11C]OMAR analogs (51-53, Figure 17) that were prepared in high overall chemical yields (Gao et al., 2012). The radiosynthesis was employed at the oxygen position of the precursor the O-[11C]methylation radiolabeling. Radiolabeling procedures incorporated efficiently [11C]CH3O with [11C]CH3OTf. The target tracers were isolated and purified in high radiochemical yields, short overall synthesis time, and high specific activity making them the potential preclinical and clinical PET agents in animals and humans.

FIGURE 17

Structure of 11C radiolabeled ligands 51-54.

6 Conclusion

In Table 1 are summarised the CB1R binding of the probes reported in this review. As a result of the important repercussions in ECS modulation, targeting this system is currently one of the major trends in drug discovery. If we take in consideration CB1R only, this receptor can be exploited to treat a variety of pathologies, including neurological disorders (i.e., Huntington’s disease, multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease) (McCaw et al., 2004; Pertwee, 2006; Pertwee, 2007; Liu et al., 2015), as well as peripheral disorders that involve energy metabolism, food intake, and obesity (DiPatrizio, 2021; Hijová, 2022). In addition to controlling liver and kidney function, it also controls bone remodeling, skeletal mass, and elongation under normal and pathophysiological conditions (Tam et al., 2018).

TABLE 1

| Ligand | Probe | CB1R binding | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| AM91 (6) | PA | Ki (rCB1R) = 19 nM | pCB |

| (7) | PA | Ki (rCB1R) = 0.4 nM | pCB |

| AM869 (8) | PA | Ki (rCB1R) = 0.67 nM | pCB |

| AM1708 (9) | PA | Ki (rCB1R) = 0.72 nM | pCB |

| (10) | PA | Kd (mCB1R) = 5.60 P.m.; 9.38 p.m. | pCB |

| AM993 (11) | PA | Ki (rCB1R) = 4.4 nM | pCB |

| AM3661 (12) | PA | Ki (rCB1R) = 0.9 nM | eCB |

| (13) | PA | Ki (hCB1R) = 0.9 µM | eCB |

| (14,15) | PA | eCB | |

| AM708 (16) | EP | IC50 (rCB1R) = 1.6 nM | pCB |

| (17) | EP | IC50 (rCB1R) = 660 p.m. | pCB |

| AM841 (18) | EP | Ki (hCB1R) = 9.05nM; EC50 = 0.94 nM | pCB |

| AM960 (19) | EP | IC50 (rCB1R) = 25 nM | pCB |

| AM994 (20) | EP | Ki (rCB1R) = 3.0 nM; EC50 = 0.8 nM | pCB |

| (21) | EP | EC50 (rCB1R) = 1.1 µM | synth |

| GAT100 (22) | EP | EC50 (rCB1R) = 2.09 nM | synth |

| AM3677 (23) | EP | Ki (hCB1R) = 1.3 nM | eCB |

| AM859 (24) | BP | Ki (hCB1R) = 1.60 nM | pCB |

| AM5823 (25) | BP | pCB | |

| AM4099 (26) | BP | Ki (hCB1R) = 12.6 nM | pCB |

| AM5822 (27) | BP | pCB | |

| (28) | FP | Ki (hCB1R) = 221 nM | eCB |

| (29) | FP | Ki (hCB1R) = 2.4 nM | pCB |

| (30) | FP | pCB | |

| (31) | FP | Ki (hCB1R) = 27 nM | pCB |

| (32) | FP | Ki (hCB1R) = 5.26 nM | pCB |

| T117 (33) | FP | Kd (hCB1R) = 460 nM | pCB |

| (34) | FP | Ki (hCB1R) = 260 nM | pCB |

| (35) | FP | Ki (hCB1R) = 2.1 µM | pCB |

| (36-38) | PET | Ki (hCB1R) = 5.6 nM; IC50 = 14 nM; IC50 = 120 nM | synth |

| (41) | PET | Ki (rCB1R) = 0.9 nM | synth |

| (43) | PET | Ki (hCB1R) = 2.2 nM; IC50 = 0.7 nM | synth |

| (44, 45) | PET | Kb (hCB1R) = 0.574 nM | synth |

| (46) | PET | Ki (hCB1R) = 11 nM | synth |

| (47) | PET | Ki (hCB1R) = 0.47 nM | synth |

| (48-50) | PET | Ki (rCB1R) = 0.7 µM; Ki (rCB1R) = 14.4 µM | synth |

| (51-53) | PET | Ki (hCB1R) = 11 nM; Ki (hCB1R) = 2 nM; Ki (hCB1R) = 4.7 nM | synth |

Summary of the CB1R binding of the probes reported in this review.

PA, photoactivatable; EP, electrophilic; pCB, phytocannabinoids derivatives; eCB, endocannabinoids analogues; synth, synthetic cannabinoids derivatives; BP, bifunctional probes; FP, fluorescent probes; AG, 2-arachidonoylglycerol; PET, positron emission tomography.

A significant amount of information has been accumulated in the literature concerning the in vivo and in vitro pharmacology of the CB1R over the past decades, revealing new insights into pathways controlled and the roles of receptors, enzymes, and ligands. This knowledge has, however, made a complete transition into drug development in only a few cases (i.e., Sativex) (Namdar et al., 2020).

In order to develop novel therapeutic and diagnostic tools, it is necessary to understand the functions and molecular mechanisms associated with CB1R modulation; to this aim, several molecular probes that utilize multiple interaction mechanisms (i.e., fluorescence, PET) have been developed in the past 30 years. These results demonstrate the great interest in this biological target: the development of new selective probes is therefore essential to obtaining new results that can lead to the introduction of new CB1R-based drugs on the market.

Statements

Author contributions

Conceptualization, DC, VF, and DI; validation, DC, VF, and DI; formal analysis, AA; investigation, AA, VF, and DI; resources, AA, DC, VF, and DI; writing—original draft preparation, VF and DI; writing—review and editing, AA, DC, VF, and DI; supervision, AM, LP, and DP; project administration, DC, VF, and DI; funding acquisition, DC and AM. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Research on phytocannabinoids at the laboratories of Novara was funded by MIUR Italy (PRIN2017, Project 2017WN73PL, bioactivity-directed exploration of the phytocannabinoid chemical space).

Conflict of interest

The authors DC, DI, and VF declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. AM was employed by Plantachem SRL, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abedi E. Sahari M. A. (2014). Long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acid sources and evaluation of their nutritional and functional properties. Food Sci. Nutr.2, 443–463. 10.1002/fsn3.121

2

Alexander S. P. H. (2016). Therapeutic potential of cannabis-related drugs. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry64, 157–166. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.07.001

3

Anokwuru C. P. Makolo F. L. Sandasi M. Tankeu S. Y. Elisha I. L. Agoni C. et al (2022). Cannabigerol: A bibliometric overview and review of research on an important phytocannabinoid. Phytochem. Rev.21, 1523–1547. 10.1007/s11101-021-09794-w

4

Appendino G. (2020). The early history of cannabinoid research. Rend. Fis. Acc. Lincei31, 919–929. 10.1007/s12210-020-00956-0

5

Balas L. Cascio M. G. Marzo V. D. Durand T. (2006). Synthesis of a potential photoactivatable anandamide analog. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.16, 3765–3768. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.04.059

6

Balas L. Durand T. Saha S. Johnson I. Mukhopadhyay S. (2009). Total synthesis of photoactivatable or fluorescent anandamide probes: Novel bioactive compounds with angiogenic activity. J. Med. Chem.52, 1005–1017. 10.1021/jm8011382

7

Baratta F. Pignata I. Ravetto Enri L. Brusa P. (2022). Cannabis for medical use: Analysis of recent clinical trials in view of current legislation. Front. Pharmacol.13, 888903. 10.3389/fphar.2022.888903

8

Bisogno T. Di Marzo V. (2010). Cannabinoid receptors and endocannabinoids: Role in neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative disorders. CNSNDDT9, 564–573. 10.2174/187152710793361568

9

Briddon S. J. Kellam B. Hill S. J. (2011). “Design and use of fluorescent ligands to study ligand–receptor interactions in single living cells,” in Receptor signal transduction protocols methods in molecular biology. Editors Willars,G. B.ChallissR. A. J. (Totowa, NJ: Humana Press), 211–236. 10.1007/978-1-61779-126-0_11

10

Bruno A. Lembo F. Novellino E. Stornaiuolo M. Marinelli L. (2014). Beyond radio-displacement techniques for identification of CB1 ligands: The first application of a fluorescence-quenching assay. Sci. Rep.4, 3757. 10.1038/srep03757

11

Burns H. D. Van Laere K. Sanabria-Bohórquez S. Hamill T. G. Bormans G. Eng W. et al (2007). [ 18 F]MK-9470, a positron emission tomography (PET) tracer for in vivo human PET brain imaging of the cannabinoid-1 receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.104, 9800–9805. 10.1073/pnas.0703472104

12

Campos A. C. Fogaça M. V. Sonego A. B. Guimarães F. S. (2016). Cannabidiol, neuroprotection and neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacol. Res.112, 119–127. 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.01.033

13

Caprioglio D. Amin H. I. M. Taglialatela-Scafati O. Muñoz E. Appendino G. (2022). Minor phytocannabinoids: A misleading name but a promising opportunity for biomedical research. Biomolecules12, 1084. 10.3390/biom12081084

14

Caprioglio D. Mattoteia D. Taglialatela-Scafati O. Muñoz E. Appendino G. (2021). Cannabinoquinones: Synthesis and biological profile. Biomolecules11, 991. 10.3390/biom11070991

15

Chang C.-P. Huang H.-L. Huang J.-K. Hung M.-S. Wu C.-H. Song J.-S. et al (2019). Fluorine-18 isotope labeling for positron emission tomography imaging. Direct evidence for DBPR211 as a peripherally restricted CB1 inverse agonist. Bioorg. Med. Chem.27, 216–223. 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.11.043

16

Chang J. W. Moellering R. E. Cravatt B. F. (2012). An activity-based imaging probe for the integral membrane hydrolase KIAA1363. Angew. Chem.124, 990–994. 10.1002/ange.201107236

17

Chang P. V. Chen X. Smyrniotis C. Xenakis A. Hu T. Bertozzi C. R. et al (2009). Metabolic labeling of sialic acids in living animals with alkynyl sugars. Angew. Chem.121, 4090–4093. 10.1002/ange.200806319

18

Charalambous A. Yan G. Houston D. B. Howlett A. C. Compton D. R. Martin B. R. et al (1992). 5’-Azido-.DELTA.8-THC: A novel photoaffinity label for the cannabinoid receptor. J. Med. Chem.35, 3076–3079. 10.1021/jm00094a023

19

Chu C. Ramamurthy A. Makriyannis A. Tius M. A. (2003). Synthesis of covalent probes for the radiolabeling of the cannabinoid receptor. J. Org. Chem.68, 55–61. 10.1021/jo0264978

20

Damont A. Roeda D. Dollé F. (2013). The potential of carbon-11 and fluorine-18 chemistry: Illustration through the development of positron emission tomography radioligands targeting the translocator protein 18 kDa: Carbon-11/fluorine-18 chemistry devoted to the preparation of TSPO 18 kDa PET-radioligands. J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm.56, 96–104. 10.1002/jlcr.2992

21

Davenport A. P. Daly C. (2010). Editorial: Editorial. Br. J. Pharmacol.159, 735–737. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00685.x

22

De Petrocellis L. Di Marzo V. (2009). An introduction to the endocannabinoid system: From the early to the latest concepts. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism23, 1–15. 10.1016/j.beem.2008.10.013

23

Di Marzo V. Bifulco M. Petrocellis L. D. (2004). The endocannabinoid system and its therapeutic exploitation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.3, 771–784. 10.1038/nrd1495

24

DiPatrizio N. V. (2021). Endocannabinoids and the gut-brain control of food intake and obesity. Nutrients13, 1214. 10.3390/nu13041214

25

Donohue S. R. Krushinski J. H. Pike V. W. Chernet E. Phebus L. Chesterfield A. K. et al (2008a). Synthesis, ex vivo evaluation, and radiolabeling of potent 1,5-Diphenylpyrrolidin-2-one cannabinoid subtype-1 receptor ligands as candidates for in vivo imaging. J. Med. Chem.51, 5833–5842. 10.1021/jm800416m

26

Donohue S. R. Pike V. W. Finnema S. J. Truong P. Andersson J. Gulyás B. et al (2008b). Discovery and labeling of high-affinity 3,4-diarylpyrazolines as candidate radioligands for in vivo imaging of cannabinoid subtype-1 (CB 1) receptors. J. Med. Chem.51, 5608–5616. 10.1021/jm800329z

27

Finnan J. Styles D. (2013). Hemp: A more sustainable annual energy crop for climate and energy policy. Energy Policy58, 152–162. 10.1016/j.enpol.2013.02.046

28

Gao M. Wang M. Zheng Q.-H. (2012). A new high-yield synthetic route to PET CB1 radioligands [11C]OMAR and its analogs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.22, 3704–3709. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.04.030

29

Garcia- C. JaldonDupeyre D. Vignon M. R. (1998). Fibres from semi-retted hemp bundles by steam explosion treatment. Biomass Bioenergy14, 251–260. 10.1016/S0961-9534(97)10039-3

30

Gomes P. M. O. Silva A. M. S. Silva V. L. M. (2020). Pyrazoles as key scaffolds for the development of fluorine-18-labeled radiotracers for positron emission tomography (PET). Molecules25, 1722. 10.3390/molecules25071722

31

Grant P. S. Kahlcke N. Govindpani K. Hunter M. MacDonald C. Brimble M. A. et al (2019). Divalent cannabinoid-1 receptor ligands: A linker attachment point survey of SR141716A for development of high-affinity CB1R molecular probes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.29, 126644. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.126644

32

Grimsey N. L. Goodfellow C. E. Scotter E. L. Dowie M. J. Glass M. Graham E. S. (2008). Specific detection of CB1 receptors; cannabinoid CB1 receptor antibodies are not all created equal. J. Neurosci. Methods171, 78–86. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.02.014

33

Hamilton A. J. Payne A. D. Mocerino M. Gunosewoyo H. (2021). Imaging cannabinoid receptors: A brief collection of covalent and fluorescent probes for CB. Aust. J. Chem.74, 416–432. 10.1071/CH21007

34

Hanuš L. O. Meyer S. M. Muñoz E. Taglialatela-Scafati O. Appendino G. (2016). Phytocannabinoids: A unified critical inventory. Nat. Prod. Rep.33, 1357–1392. 10.1039/C6NP00074F

35

Herkenham M. Lynn A. B. Little M. D. Johnson M. R. Melvin L. S. de Costa B. R. et al (1990). Cannabinoid receptor localization in brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.87, 1932–1936. 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1932

36

Hijová E. (2022). Synbiotic supplements in the prevention of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Metabolites12, 313. 10.3390/metabo12040313

37

Hinz B. Ramer R. (2019). Anti-tumour actions of cannabinoids: Anti-tumour actions of cannabinoids. Br. J. Pharmacol.176, 1384–1394. 10.1111/bph.14426

38

Hirvonen J. Zanotti-Fregonara P. Umhau J. C. George D. T. Rallis-Frutos D. Lyoo C. H. et al (2013). Reduced cannabinoid CB1 receptor binding in alcohol dependence measured with positron emission tomography. Mol. Psychiatry18, 916–921. 10.1038/mp.2012.100

39

Horti A. G. Fan H. Kuwabara H. Hilton J. Ravert H. T. Holt D. P. et al (2006). 11C-JHU75528: A radiotracer for PET imaging of CB1 cannabinoid receptors. J. Nucl. Med.47, 1689–1696.

40

Iversen L. (2018). The pharmacology of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Oxf. Univ. Press. 10.1093/oso/9780190846848.003.0002

41

Janero D. R. Yaddanapudi S. Zvonok N. Subramanian K. V. Shukla V. G. Stahl E. et al (2015). Molecular-interaction and signaling profiles of AM3677, a novel covalent agonist selective for the cannabinoid 1 receptor. ACS Chem. Neurosci.6, 1400–1410. 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00090

42

Jenko K. J. Hirvonen J. Henter I. D. Anderson K. B. Zoghbi S. S. Hyde T. M. et al (2012). Binding of a tritiated inverse agonist to cannabinoid CB1 receptors is increased in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Res.141, 185–188. 10.1016/j.schres.2012.07.021

43

Katoch-Rouse R. Horti A. G. (2003). Synthesis ofN-(piperidin-1-yl)-5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1-(2-chlorophenyl)-4-[18F]fluoro-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide by nucleophilic [18F] fluorination: A PET radiotracer for studying CB1 cannabinoid receptors. J. Label. Cpd. Radiopharm.46, 93–98. 10.1002/jlcr.647

44

Khanolkar A. D. Palmer S. L. Makriyannis A. (2000). Molecular probes for the cannabinoid receptors. Chem. Phys. Lipids108, 37–52. 10.1016/S0009-3084(00)00186-9

45

Kovalchuk O. Kovalchuk I. (2020). Cannabinoids as anticancer therapeutic agents. Cell Cycle19, 961–989. 10.1080/15384101.2020.1742952

46

Kulkarni P. M. Kulkarni A. R. Korde A. Tichkule R. B. Laprairie R. B. Denovan-Wright E. M. et al (2016). Novel electrophilic and photoaffinity covalent probes for mapping the cannabinoid 1 receptor allosteric site(s). J. Med. Chem.59, 44–60. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01303

47

Li C. Xu W. Vadivel S. K. Fan P. Makriyannis A. (2005). High affinity electrophilic and photoactivatable covalent endocannabinoid probes for the CB1 receptor. J. Med. Chem.48, 6423–6429. 10.1021/jm050272i

48

Li Z. Conti P. S. (2010). Radiopharmaceutical chemistry for positron emission tomography. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.62, 1031–1051. 10.1016/j.addr.2010.09.007

49

Liu C. S. Chau S. A. Ruthirakuhan M. Lanctôt K. L. Herrmann N. (2015). Cannabinoids for the treatment of agitation and aggression in alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drugs29, 615–623. 10.1007/s40263-015-0270-y

50

Lopresti B. J. Royse S. K. Mathis C. A. Tollefson S. A. Narendran R. (2023). Beyond monoamines: I. Novel targets and radiotracers for positron emission tomography imaging in psychiatric disorders. J. Neurochem.164, 364–400. 10.1111/jnc.15615

51

Maioli C. Mattoteia D. Amin H. I. M. Minassi A. Caprioglio D. (2022). Cannabinol: History, syntheses, and biological profile of the greatest “minor” cannabinoid. Plants11, 2896. 10.3390/plants11212896

52

Makriyannis A. (2014). 2012 division of medicinal chemistry award address. Trekking the cannabinoid road: A personal perspective. J. Med. Chem.57, 3891–3911. 10.1021/jm500220s

53

Martín-Couce L. Martín-Fontecha M. Capolicchio S. López-Rodríguez M. L. Ortega-Gutiérrez S. (2011). Development of endocannabinoid-based chemical probes for the study of cannabinoid receptors. J. Med. Chem.54, 5265–5269. 10.1021/jm2004392

54

Martín-Couce L. Martín-Fontecha M. Palomares Ó. Mestre L. Cordomí A. Hernangomez M. et al (2012). Chemical probes for the recognition of cannabinoid receptors in native systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.51, 6896–6899. 10.1002/anie.201200467

55

Martín-Fontecha M. Angelina A. Rückert B. Rueda-Zubiaurre A. Martín-Cruz L. van de Veen W. et al (2018). A fluorescent probe to unravel functional features of cannabinoid receptor CB 1 in human blood and tonsil immune system cells. Bioconjugate Chem.29, 382–389. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.7b00680

56

Mathews W. B. Scheffel U. Finley P. Ravert H. T. Frank R. A. Rinaldi-Carmona M. et al (2000). Biodistribution of [18f] SR144385 and [18f] SR147963: Selective radioligands for positron emission tomographic studies of brain cannabinoid receptors. Nucl. Med. Biol.27, 757–762. 10.1016/S0969-8051(00)00152-9

57

Matsuda L. A. Lolait S. J. Brownstein M. J. Young A. C. Bonner T. I. (1990). Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature346, 561–564. 10.1038/346561a0

58

McCaw E. A. Hu H. Gomez G. T. Hebb A. L. O. Kelly M. E. M. Denovan-Wright E. M. (2004). Structure, expression and regulation of the cannabinoid receptor gene (CB1) in Huntington’s disease transgenic mice. Eur. J. Biochem.271, 4909–4920. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04460.x

59

Morse K. L. Fournier D. J. Li X. Grzybowska J. Makriyannis A. (1995). A novel electrophilic high affinity irreversible probe for the cannabinoid receptor. Life Sci.56, 1957–1962. 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00176-7

60

Munro S. Thomas K. L. Abu-Shaar M. (1993). Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature365, 61–65. 10.1038/365061a0

61

Namdar D. Anis O. Poulin P. Koltai H. (2020). Chronological review and rational and future prospects of cannabis-based drug development. Molecules25, 4821. 10.3390/molecules25204821

62

Ogawa G. Tius M. A. Zhou H. Nikas S. P. Halikhedkar A. Mallipeddi S. et al (2015). 3′-Functionalized adamantyl cannabinoid receptor probes. J. Med. Chem.58, 3104–3116. 10.1021/jm501960u

63

Pertwee R. G. (2006). Cannabinoid pharmacology: The first 66 years: Cannabinoid pharmacology. Br. J. Pharmacol.147, S163–S171. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706406

64

Pertwee R. G. (2007). Cannabinoids and multiple sclerosis. Mol. Neurobiol.36, 45–59. 10.1007/s12035-007-0005-2

65

Picone R. P. Fournier D. J. Makriyannis A. (2002). Ligand based structural studies of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor: Ligand based structural studies of CB1. J. Peptide Res.60, 348–356. 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2002.21069.x

66

Picone R. P. Khanolkar A. D. Xu W. Ayotte L. A. Thakur G. A. Hurst D. P. et al (2005). (-)-7′-Isothiocyanato-11-hydroxy-1′,1′-dimethylheptylhexahydrocannabinol (AM841), a high-affinity electrophilic ligand, interacts covalently with a cysteine in helix six and activates the CB1 cannabinoid receptor. Mol. Pharmacol.68, 1623–1635. 10.1124/mol.105.014407

67

Pollastro F. Caprioglio D. Del Prete D. Rogati F. Minassi A. Taglialatela-Scafati O. et al (2018). Cannabichromene. Nat. Product. Commun.13, 1934578X1801300. 10.1177/1934578X1801300922

68

Rehman M. S. U. Rashid N. Saif A. Mahmood T. Han J.-I. (2013). Potential of bioenergy production from industrial hemp (cannabis sativa): Pakistan perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.18, 154–164. 10.1016/j.rser.2012.10.019

69

Rinaldi-Carmona M. Barth F. Héaulme M. Shire D. Calandra B. Congy C. et al (1994). SR141716A, a potent and selective antagonist of the brain cannabinoid receptor. FEBS Lett.350, 240–244. 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00773-X

70

Sholler D. J. Schoene L. Spindle T. R. (2020). Therapeutic efficacy of cannabidiol (CBD): A review of the evidence from clinical trials and human laboratory studies. Curr. Addict. Rep.7, 405–412. 10.1007/s40429-020-00326-8

71

Singh S. Oyagawa C. R. M. Macdonald C. Grimsey N. L. Glass M. Vernall A. J. (2019). Chromenopyrazole-based high affinity, selective fluorescent ligands for cannabinoid type 2 receptor. ACS Med. Chem. Lett.10, 209–214. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00597

72

Stoddart L. A. Kilpatrick L. E. Briddon S. J. Hill S. J. (2015). Probing the pharmacology of G protein-coupled receptors with fluorescent ligands. Neuropharmacology98, 48–57. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.04.033

73

Sumranjit J. Chung S. (2013). Recent advances in target characterization and identification by photoaffinity probes. Molecules18, 10425–10451. 10.3390/molecules180910425

74

Takkinen J. S. López-Picón F. R. Kirjavainen A. K. Pihlaja R. Snellman A. Ishizu T. et al (2018). [18F]FMPEP-d2 PET imaging shows age- and genotype-dependent impairments in the availability of cannabinoid receptor 1 in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging69, 199–208. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.05.013

75

Tam J. Hinden L. Drori A. Udi S. Azar S. Baraghithy S. (2018). The therapeutic potential of targeting the peripheral endocannabinoid/CB 1 receptor system. Eur. J. Intern. Med.49, 23–29. 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.01.009

76

Terry G. E. Hirvonen J. Liow J.-S. Zoghbi S. S. Gladding R. Tauscher J. T. et al (2010). Imaging and quantitation of cannabinoid CB 1 receptors in human and monkey brains using 18 F-labeled inverse agonist radioligands. J. Nucl. Med.51, 112–120. 10.2967/jnumed.109.067074

77

Tobiishi S. Sasada T. Nojiri Y. Yamamoto F. Mukai T. Ishiwata K. et al (2007). Methoxy- and fluorine-substituted analogs of O-1302: Synthesis and in vitro binding affinity for the CB1 cannabinoid receptor. Chem. Pharm. Bull.55, 1213–1217. 10.1248/cpb.55.1213

78

Tomko A. M. Whynot E. G. Ellis L. D. Dupré D. J. (2020). Anti-cancer potential of cannabinoids, terpenes, and flavonoids present in cannabis. Cancers12, 1985. 10.3390/cancers12071985

79

Tsujikawa T. Zoghbi S. S. Hong J. Donohue S. R. Jenko K. J. Gladding R. L. et al (2014). In vitro and in vivo evaluation of 11C-SD5024, a novel PET radioligand for human brain imaging of cannabinoid CB1 receptors. NeuroImage84, 733–741. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.09.043

80

Tully S. E. Cravatt B. F. (2010). Activity-based probes that target functional subclasses of phospholipases in proteomes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.132, 3264–3265. 10.1021/ja1000505

81

Viana M. D. B. Aquino P. E. A. D. Estadella D. Ribeiro D. A. Viana G. S. D. B. (2022). Cannabis sativa and cannabidiol: A therapeutic strategy for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases?Med. Cannabis Cannabinoids5, 207–219. 10.1159/000527335

82

Yamada K. Rice K. C. Flippen-Anderson J. L. Eissenstat M. A. Ward S. J. Johnson M. R. et al (1996). Aminoalkyl)indole isothiocyanates as potential electrophilic affinity ligands for the brain cannabinoid receptor. J. Med. Chem.39, 1967–1974. 10.1021/jm950932r

83

Yamasaki T. Fujinaga M. Shimoda Y. Mori W. Zhang Y. Wakizaka H. et al (2017). Radiosynthesis and evaluation of new PET ligands for peripheral cannabinoid receptor type 1 imaging. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.27, 4114–4117. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.07.040

84

Yasuno F. Brown A. K. Zoghbi S. S. Krushinski J. H. Chernet E. Tauscher J. et al (2008). The PET radioligand [11C]MePPEP binds reversibly and with high specific signal to cannabinoid CB1 receptors in nonhuman primate brain. Neuropsychopharmacol33, 259–269. 10.1038/sj.npp.1301402

85

Zhou H. Peng Y. Halikhedkar A. Fan P. Janero D. R. Thakur G. A. et al (2017). Human cannabinoid receptor 2 ligand-interaction motif: Transmembrane helix 2 cysteine, C2.59(89), as determinant of classical cannabinoid agonist activity and binding pose. ACS Chem. Neurosci.8, 1338–1347. 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00003

Summary

Keywords

cannabinoids, CB1R, photoactivatable probes, fluorescent probes, PET imaging

Citation

Amenta A, Caprioglio D, Minassi A, Panza L, Passarella D, Fasano V and Imperio D (2023) Recent advances in the development of CB1R selective probes. Front. Nat. Produc. 2:1196321. doi: 10.3389/fntpr.2023.1196321

Received

29 March 2023

Accepted

07 July 2023

Published

18 July 2023

Volume

2 - 2023

Edited by

Eng Shi Ong, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore

Reviewed by

Yang Qu, University of New Brunswick Fredericton, Canada

Benita Wiatrak, Wroclaw Medical University, Poland

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Amenta, Caprioglio, Minassi, Panza, Passarella, Fasano and Imperio.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Valerio Fasano, valerio.fasano@unimi.it; Daniela Imperio, daniela.imperio@uniupo.it

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.