- 1Hotchkiss Brain Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

- 2Libin Cardiovascular Research Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

- 3Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

- 4Department of Biomedical Sciences, Grand Valley State University, Allendale, MI, USA

Over the past decade, second messenger communication has emerged as one of the intriguing topics in the field of vasomotor control. Of particular interest has been the idea of second messenger flux from smooth muscle to endothelium initiating a feedback response that attenuates constriction. Mechanistic details of the precise signaling cascade have until recently remained elusive. In this perspective, we introduce readers to how myoendothelial gap junctions could enable sufficient inositol trisphosphate flux to initiate endothelial Ca2+ events that activate Ca2+ sensitive K+ channels. The resulting hyperpolarizing current would in turn spread back through the same myoendothelial gap junctions to moderate smooth muscle depolarization and constriction. In discussing this defined feedback mechanism, this brief manuscript will stress the importance of microdomains and of discrete cellular signaling.

Introduction

To optimize blood flow delivery to active tissue, tone in arteriole networks is modified by prevailing mechanical and chemical stimuli. These stimuli affect tone by altering smooth muscle contractility through changes in the phosphorylation state of the 20-kDa regulatory light chain of myosin II (MLC20). The proximate regulators of MLC20 are myosin light chain- kinase (MLCK) and phosphatase (MLCP), which are in turn controlled by membrane potential (VM) and second messenger signaling. When stimuli alter endothelial VM, charge moves to smooth muscle through gap junctions (Emerson and Segal, 2000; Berman et al., 2002; de Wit et al., 2006; Haddock et al., 2006) to elicit vasomotor responses (Little et al., 1995; Li and Simard, 2001; Hill et al., 2002). While ionic movement, albeit cations, or anions, through myoendothelial gap junctions (MEGJ) is responsible for the endothelial-dependent hyperpolarization of smooth muscle (Bartlett and Segal, 2000; Emerson and Segal, 2000; Coleman et al., 2001; Budel et al., 2003; Dora et al., 2003; Diep et al., 2005; Domeier and Segal, 2007; Tran et al., 2009), studies have also pointed to the possibility of second messengers flux influencing arterial tone (Dora et al., 1997; Uhrenholt et al., 2007). In this regard, initial work centered on the moderation of vessel constriction through the bulk movement of Ca2+ and/or IP3 from smooth muscle to endothelium (Dora et al., 1997; Yashiro and Duling, 2000; Lamboley et al., 2005; Isakson et al., 2007). More recently, studies have focused on discrete second messenger movements from smooth muscle to elicit localized Ca2+ events in the endothelium (Uhrenholt et al., 2006, 2007; Tallini et al., 2007). This brief review will focus on the nature of second messenger communication and how such movements could elicit “myoendothelial feedback responses.”

Initial Observations of Myoendothelial Feedback

The functional relevance of myoendothelial feedback was first reported in the context of conducted responses. These vasomotor responses are elicited by discrete agonist-induced changes in VM that travel along the vessel wall (Bartlett and Segal, 2000; Emerson and Segal, 2000; Coleman et al., 2001; Budel et al., 2003; Dora et al., 2003; Diep et al., 2005; Domeier and Segal, 2007; Tran et al., 2009). What intrigued investigators was the inability of smooth muscle agonists, purported to constrict via depolarization, to spread beyond the application site (Dora et al., 1997; Yashiro and Duling, 2000, 2003). This lack of intercellular conduction was attributed to a myoendothelial feedback response that sequentially involved: (1) bulk Ca2+ flux across MEGJs from depolarized smooth muscle; (2) global elevation of endothelial [Ca2+]; (3) activation of the dilatory effectors (nitric oxide release Dora et al., 1997) or SK/IK channels (Yashiro and Duling, 2000, 2003); (4) redistribution of charge to counter the initial smooth muscle response. While intriguing, recent studies have shown that discrete smooth muscle stimuli fail to elicit conduction due to an inability to initiate depolarization (see Tran et al., 2009; Tran and Welsh, 2009 for details). In light of this finding and a range of biophysical limitations, the vascular field could have dismissed the idea of myoendothelial feedback. Investigators instead revised the concept taking into account new structural information and the ability to measure discrete endothelial Ca2+ events.

Structural Composition of Myoendothelial Contact Sites

Endothelial Projections

Resistance arteries are comprised of a single endothelial layer surrounded by one or more smooth muscle layers. The internal elastic lamina (IEL) is a layer of collagen and elastin separating these two cell types. The thickness of the IEL was thought to preclude direct contact between endothelium and smooth muscle. Work over the last decade, however, have revealed the presence of “holes” in the IEL, regions devoid of elastin (Sandow et al., 2002, 2006, 2009; Ledoux et al., 2008b). These regions contain thin endothelial projections that extend through the IEL and make contact with the overlying smooth muscle (Sandow et al., 2002, 2006, 2009). While the process by which they are formed remains elusive, endothelial projections appear to retain structures such as endoplasmic reticulum (ER), caveoli, and trafficking vesicles. More importantly, the proteins essential to controlling resistance vessel tone are preserved. These proteins will be discussed below.

Gap Junctions

Gap junctions are comprised of two docking hemichannels (connexons) that enable the movement of charge (anions and cations) and small metabolites/molecules among neighboring cells (Revel and Karnovsky, 1967). Each connexon is an oligomer of six connexin (Cx) subunits (Caspar et al., 1977; Makowski et al., 1977), each of which possess four hydrophobic membrane-spanning domains, two conserved extracellular domains and three variable intracellular domains. Connexins retain distinct molecular properties and varying connexon composition alters the specific permeability of gap junction channels (Bruzzone et al., 1996; Willecke et al., 2002; Saez et al., 2005). This is exemplified by the ability of Cx40 to enable passive diffusion of IP3 a key second messenger (Sneyd et al., 1998; Kanaporis et al., 2011). Among the 21 members of the Cx family, Cx37, Cx40, Cx43, and Cx45 are typically observed in vascular cells (Little et al., 1995; Li and Simard, 2001; Hill et al., 2002). Immunohistochemical evidence suggests that Cx expression in the endothelium is substantively higher than in the smooth muscle (Sandow and Hill, 2000; Sandow et al., 2003). Consistent with this view, coupling resistance among endothelial cells (1.5–3.0 MΩ) (Lidington et al., 2000) was 30 fold lower than among smooth muscle cells (Yamamoto et al., 2001). Interestingly, myoendothelial coupling is orders of magnitude greater than smooth muscle cells (>1800 MΩ) (Yamamoto et al., 2001). This high resistivity is in agreement with the immunohistochemical evidence demonstrating few Cx37 and Cx40 expressed in IEL “holes” (Sandow et al., 2006). Although MEGJs are present in endothelial projections passing through the IEL, not all IEL holes possess endothelial projections. Indeed, as vessel size increases, the incidence of MEGJs appears to decrease (Sandow and Hill, 2000; Sandow et al., 2009) indicative of myoendothelial feedback playing a greater role in small resistance arterioles. As these MEGJs are sparsely distributed, the channels stimulated by transiting second messengers must be very close to MEGJs.

IP3 Receptors

The three isoforms of IP3R (i.e., IP3R1, IP3R2, IP3R3) are widely expressed and uniquely distributing in a range of cells. In whole mesenteric arteries, all 3 isoforms have been detected, with IP3R1 and IP3R2 appearing to be heavily expressed in endothelial cells (Ledoux et al., 2008b; Sandow et al., 2009). These receptors are important in vascular tone development, as they are involved in regulating intracellular [Ca2+]. IP3 binds to the IP3Rs and lowers the affinity of the stimulatory site for Ca2+, thereby promoting channel opening and release of Ca2+ (Bootman et al., 1995; Chalmers et al., 2007). In the presence of IP3, these receptors are activated by intracellular [Ca2+] of ~300 nM. Functional studies demonstrate that IP3Rs on the ER play an important role in myoendothelial feedback as impairing ER Ca2+ mobilization and inhibition of IP3Rs augmented agonist-induced contraction (Nausch et al., 2012; Tran et al., 2012). The original model for myoendothelial feedback required the flux of second messengers across the MEGJs from the contracting smooth muscle. Given that MEGJ communication is minimal, bulk diffusion of Ca2+ alone is unlikely to elevate endothelial [Ca2+] (Dora et al., 1997; Kansui et al., 2008). If IP3 were to cross the MEGJs to elicit a change in endothelial [Ca2+], the IP3Rs would have to localize near the myoendothelial contact site in order to elicit a response. Past immunohistochemistry studies support the view that a close spatial relationship between IP3Rs and MEGJ proteins (i.e., Cx37 and Cx40) does indeed exist (Ledoux et al., 2008b; Sandow et al., 2009; Nausch et al., 2012; Tran et al., 2012). Localization of IP3Rs within the endothelial projections place these receptors in an ideal position to respond when a small quanta of IP3 crosses the MEGJs from contracting smooth muscle. Subsequent release of Ca2+ from the ER causes a discrete rise in endothelial [Ca2+]. In order for a discrete rise in [Ca2+] to influence global [Ca2+], that Ca2+ must be able to affect neighboring Ca2+ sensitive ion channels.

Calcium Activated K+ channels

The likely candidates for discrete activation by Ca2+ are the calcium activated K+ channels. Within this family of channels, the SK and IK channels are purported to be the most important in terms of myoendothelial feedback. To date, three members of the SK channel family have been identified (i.e., KCa2.1–2.3). Due to high degree of similarity with other SK channels, the previously identified IK or KCa3.1 channel is often viewed as the fourth member of the SK family. Both KCa3.1 and KCa2.3 channels are predominantly expressed in the endothelial cells (Nilius and Droogmans, 2001; Taylor et al., 2003; Sandow et al., 2006). Both KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 channels lack voltage sensitivity (Ledoux et al., 2008a); they are instead gated by nanomolar intracellular [Ca2+] (i.e., EC50 300–500 nM) via coupling of calmodulin to the carboxy-terminus acting as Ca2+ sensor (Bond et al., 1999; Schumacher et al., 2001). In order to be involved in myoendothelial feedback, these channels must be localized within endothelial projections where the discrete ER Ca2+ release occurs which is also near the MEGJ. In fact, immunohistochemistry has repeatedly shown KCa3.1 channels are expressed in close proximity to MEGJs (Sandow and Hill, 2000; Sandow et al., 2002, 2004, 2006; Haddock et al., 2006; Dora et al., 2008; Tran et al., 2012). However, the KCa2.3 channels appear to be more diffusely distributed (Sandow and Hill, 2000; Sandow et al., 2002, 2006, 2009). Further support for the KCa3.1 channel was the functional evidence showing TRAM34, a KCa3.1 channel blocker, but not apamin, a KCa2.x channel blocker, inhibit myoendothelial feedback (Nausch et al., 2012; Tran et al., 2012). Thus, the KCa3.1 channel appears to be localized within the endothelial projection where it can be involved in myoendothelial feedback. Activation of endothelial KCa3.1 channels leads to hyperpolarization and mediates relaxation via transmission of hyperpolarizing current through MEGJs.

Current Perspective

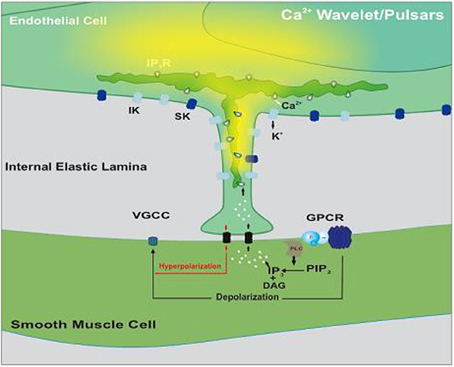

The original view of myoendothelial feedback has been adapted and applied to a setting where constrictor agonists are globally applied to induce a depolarization-dependent constriction (Figure 1). The extent of that depolarization, and thereby constriction, is reduced by negative myoendothelial feedback (Tran et al., 2012). This feedback involves the generation of Ca2+ wavelets and/or perhaps Ca2+ pulsars within or near endothelial projections (Nausch et al., 2012; Tran et al., 2012). Irrespective of whether Ca2+ wavelets are kinetically distinct from Ca2+ pulsars, both events are spatially and temporally discrete, sensitive to IP3R blockade and strikingly distinct from the global elevations of endothelial [Ca2+], reported in previous studies (Dora et al., 1997; Yashiro and Duling, 2000; Lamboley et al., 2005). The distinct characteristics of the Ca2+ wavelets are consistent with the focal nature of IP3R expression within or near the endothelial projections. Local elevations in Ca2+ activate KCa3.1 and perhaps KCa2.3 channels expressed near the endothelial projections to elicit hyperpolarization.

Figure 1. Illustrative diagram of the myoendothelial feedback pathway. Smooth muscle agonists activate G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) initiating IP3 production via phospholipase C (PLC). This second messenger crosses myoendothelial gap junctions and triggers Ca2+ release via IP3Rs positioned on the endoplasmic reticulum. As Ca2+ wavelets/pulsars spread, they activate intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (IK) channels within or near the endothelial projection. The resulting hyperpolarization conducts back to smooth muscle where it sequentially attenuates depolarization, Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated Ca2+ (VGCC) and arterial constriction. Modified from Tran et al. (2012).

Limitations

Recent observations on myoendothelial feedback have provided mechanistic insights into this process. This perspective is, however, built on measurements that assess the outcome of second messenger flux and not transcellular flux itself. This is due to the absence of techniques to directly evaluate IP3 movement. It should also be recognized that the structural requisites for myoendothelial feedback might not be present in all resistance arteries. As such, caution should be applied when extending current findings beyond the vascular beds of skeletal muscle or the mesentery.

Conclusions

In summary, our understanding of the role myoendothelial feedback plays in vascular function has undergone considerable refinement over the past decade. Starting from the unlikely model of bulk Ca2+ flux (Dora et al., 1997; Yashiro and Duling, 2000, 2003), the field has progressed to a more discrete model involving specific channels and receptors positioned in close proximity to one another (Tran et al., 2012). The discrete character of this response was highlighted herein to provide a framework to evaluate other vascular functions that might be impacted by myoendothelial feedback (i.e., angiogenesis). At the same time, this work has implications for our understanding of vascular pathologies like hypertension where conduction along the endothelium is reduced (Kurjiaka, 2004; Kurjiaka et al., 2005). As conduction relies on communication through MEGJs, this apparent decline in MEGJ might be accompanied by a reduction in myoendothelial feedback, which could contribute to the increased constriction observed in the hypertensive vasculature. In any case, further work is required to better understand the functional implications of myoendothelial feedback for the resistance vasculature.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research [MOP-69088 to Donald G. Welsh]. Cam Ha T. Tran holds a postdoctoral fellowship from Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions.

References

Bartlett, I. S., and Segal, S. S. (2000). Resolution of smooth muscle and endothelial pathways for conduction along hamster cheek pouch arterioles. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 278, H604–H612.

Berman, R. S., Martin, P. E., Evans, W. H., and Griffith, T. M. (2002). Relative contributions of NO and gap junctional communication to endothelium-dependent relaxations of rabbit resistance arteries vary with vessel size. Microvasc. Res. 63, 115–128. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2001.2352

Bond, C. T., Maylie, J., and Adelman, J. P. (1999). Small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 868, 370–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11298.x

Bootman, M. D., Missiaen, L., Parys, J. B., De, S. H., and Casteels, R. (1995). Control of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-induced Ca2+ release by cytosolic Ca2+. Biochem. J. 306(Pt 2), 445–451.

Bruzzone, R., White, T. W., and Paul, D. L. (1996). Connections with connexins: the molecular basis of direct intercellular signaling. Eur. J. Biochem. 238, 1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0001q.x

Budel, S., Bartlett, I. S., and Segal, S. S. (2003). Homocellular conduction along endothelium and smooth muscle of arterioles in hamster cheek pouch: unmasking an NO wave. Circ. Res. 93, 61–68. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000080318.81205.FD

Caspar, D. L., Goodenough, D. A., Makowski, L., and Phillips, W. C. (1977). Gap junction structures. I. Correlated electron microscopy and x-ray diffraction. J. Cell Biol. 74, 605–628. doi: 10.1083/jcb.74.2.605

Chalmers, S., Olson, M. L., MacMillan, D., Rainbow, R. D., and McCarron, J. G. (2007). Ion channels in smooth muscle: regulation by the sarcoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. Cell Calcium 42, 447–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.05.010

Coleman, H. A., Tare, M., and Parkington, H. C. (2001). EDHF is not K+ but may be due to spread of current from the endothelium in guinea pig arterioles. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 280, H2478–H2483.

de Wit, C., Hoepfl, B., and Wolfle, S. E. (2006). Endothelial mediators and communication through vascular gap junctions. Biol. Chem. 387, 3–9. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.002

Diep, H. K., Vigmond, E. J., Segal, S. S., and Welsh, D. G. (2005). Defining electrical communication in skeletal muscle resistance arteries: a computational approach. J. Physiol. 568, 267–281. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.090233

Domeier, T. L., and Segal, S. S. (2007). Electromechanical and pharmacomechanical signalling pathways for conducted vasodilatation along endothelium of hamster feed arteries. J. Physiol. 579, 175–186. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124529

Dora, K. A., Doyle, M. P., and Duling, B. R. (1997). Elevation of intracellular calcium in smooth muscle causes endothelial cell generation of NO in arterioles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 6529–6534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6529

Dora, K. A., Gallagher, N. T., McNeish, A., and Garland, C. J. (2008). Modulation of endothelial cell KCa3.1 channels during endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor signaling in mesenteric resistance arteries. Circ. Res. 102, 1247–1255. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.172379

Dora, K. A., Sandow, S. L., Gallagher, N. T., Takano, H., Rummery, N. M., Hill, C. E., et al. (2003). Myoendothelial gap junctions may provide the pathway for EDHF in mouse mesenteric artery. J. Vasc. Res. 40, 480–490. doi: 10.1159/000074549

Emerson, G. G., and Segal, S. S. (2000). Electrical coupling between endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells in hamster feed arteries: role in vasomotor control. Circ. Res. 87, 474–479. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.6.474

Haddock, R. E., Grayson, T. H., Brackenbury, T. D., Meaney, K. R., Neylon, C. B., Sandow, S. L., et al. (2006). Endothelial coordination of cerebral vasomotion via myoendothelial gap junctions containing connexins 37 and 40. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 291, H2047–H2056. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00484.2006

Hill, C. E., Rummery, N., Hickey, H., and Sandow, S. L. (2002). Heterogeneity in the distribution of vascular gap junctions and connexins: implications for function. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 29, 620–625. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03699.x

Isakson, B. E., Ramos, S. I., and Duling, B. R. (2007). Ca2+ and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-mediated signaling across the myoendothelial junction. Circ. Res. 100, 246–254. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000257744.23795.93

Kanaporis, G., Brink, P. R., and Valiunas, V. (2011). Gap junction permeability: selectivity for anionic and cationic probes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 300, C600–C609. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00316.2010

Kansui, Y., Garland, C. J., and Dora, K. A. (2008). Enhanced spontaneous Ca2+ events in endothelial cells reflect signalling through myoendothelial gap junctions in pressurized mesenteric arteries. Cell Calcium 44, 135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.11.012

Kurjiaka, D. T. (2004). The conduction of dilation along an arteriole is diminished in the cremaster muscle of hypertensive hamsters. J. Vasc. Res. 41, 517–524. doi: 10.1159/000081808

Kurjiaka, D. T., Bender, S. B., Nye, D. D., Wiehler, W. B., and Welsh, D. G. (2005). Hypertension attenuates cell-to-cell communication in hamster retractor muscle feed arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 288, H861–H870. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00729.2004

Lamboley, M., Pittet, P., Koenigsberger, M., Sauser, R., Beny, J. L., and Meister, J. J. (2005). Evidence for signaling via gap junctions from smooth muscle to endothelial cells in rat mesenteric arteries: possible implication of a second messenger. Cell Calcium 37, 311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.11.004

Ledoux, J., Bonev, A. D., and Nelson, M. T. (2008a). Ca2+-activated K+ channels in murine endothelial cells: block by intracellular calcium and magnesium. J. Gen. Physiol. 131, 125–135. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709875

Ledoux, J., Taylor, M. S., Bonev, A. D., Hannah, R. M., Solodushko, V., Shui, B., et al. (2008b). Functional architecture of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate signaling in restricted spaces of myoendothelial projections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 9627–9632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801963105

Li, X., and Simard, J. M. (2001). Connexin45 gap junction channels in rat cerebral vascular smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 281, H1890–H1898.

Lidington, D., Ouellette, Y., and Tyml, K. (2000). Endotoxin increases intercellular resistance in microvascular endothelial cells by a tyrosine kinase pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 185, 117–125. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200010)185:1%3C117::AID-JCP11%3E3.0.CO;2-7

Little, T. L., Beyer, E. C., and Duling, B. R. (1995). Connexin 43 and connexin 40 gap junctional proteins are present in arteriolar smooth muscle and endothelium in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. 268, H729–H739.

Makowski, L., Caspar, D. L., Phillips, W. C., and Goodenough, D. A. (1977). Gap junction structures. II. Analysis of the x-ray diffraction data. J. Cell Biol. 74, 629–645. doi: 10.1083/jcb.74.2.629

Nausch, L. W., Bonev, A. D., Heppner, T. J., Tallini, Y., Kotlikoff, M. I., and Nelson, M. T. (2012). Sympathetic nerve stimulation induces local endothelial Ca2+ signals to oppose vasoconstriction of mouse mesenteric arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 302, H594–H602. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00773.2011

Nilius, B., and Droogmans, G. (2001). Ion channels and their functional role in vascular endothelium. Physiol. Rev. 81, 1415–1459.

Revel, J. P., and Karnovsky, M. J. (1967). Hexagonal array of subunits in intercellular junctions of the mouse heart and liver. J. Cell Biol. 33, C7–C12. doi: 10.1083/jcb.33.3.C7

Saez, J. C., Retamal, M. A., Basilio, D., Bukauskas, F. F., and Bennett, M. V. (2005). Connexin-based gap junction hemichannels: gating mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1711, 215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.01.014

Sandow, S. L., Goto, K., Rummery, N. M., and Hill, C. E. (2004). Developmental changes in myoendothelial gap junction mediated vasodilator activity in the rat saphenous artery. J. Physiol. 556, 875–886. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058669

Sandow, S. L., Haddock, R. E., Hill, C. E., Chadha, P. S., Kerr, P. M., Welsh, D. G., et al. (2009). What's where and why at a vascular myoendothelial microdomain signalling complex. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 36, 67–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.05076.x

Sandow, S. L., and Hill, C. E. (2000). Incidence of myoendothelial gap junctions in the proximal and distal mesenteric arteries of the rat is suggestive of a role in endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated responses. Circ. Res. 86, 341–346. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.86.3.341

Sandow, S. L., Looft-Wilson, R., Doran, B., Grayson, T. H., Segal, S. S., and Hill, C. E. (2003). Expression of homocellular and heterocellular gap junctions in hamster arterioles and feed arteries. Cardiovasc. Res. 60, 643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.09.017

Sandow, S. L., Neylon, C. B., Chen, M. X., and Garland, C. J. (2006). Spatial separation of endothelial small- and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (K(Ca)) and connexins: possible relationship to vasodilator function? J. Anat. 209, 689–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00647.x

Sandow, S. L., Tare, M., Coleman, H. A., Hill, C. E., and Parkington, H. C. (2002). Involvement of myoendothelial gap junctions in the actions of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Circ. Res. 90, 1108–1113. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000019756.88731.83

Schumacher, M. A., Rivard, A. F., Bachinger, H. P., and Adelman, J. P. (2001). Structure of the gating domain of a Ca2+-activated K+ channel complexed with Ca2+/calmodulin. Nature 410, 1120–1124. doi: 10.1038/35074145

Sneyd, J., Wilkins, M., Strahonja, A., and Sanderson, M. J. (1998). Calcium waves and oscillations driven by an intercellular gradient of inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate. Biophys. Chem. 72, 101–109. doi: 10.1016/S0301-4622(98)00126-4

Tallini, Y. N., Brekke, J. F., Shui, B., Doran, R., Hwang, S. M., Nakai, J., et al. (2007). Propagated endothelial Ca2+ waves and arteriolar dilation in vivo: measurements in Cx40BAC GCaMP2 transgenic mice. Circ. Res. 101, 1300–1309. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.149484

Taylor, M. S., Bonev, A. D., Gross, T. P., Eckman, D. M., Brayden, J. E., Bond, C. T., et al. (2003). Altered expression of small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SK3) channels modulates arterial tone and blood pressure. Circ. Res. 93, 124–131. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000081980.63146.69

Tran, C. H., Taylor, M. S., Plane, F., Nagaraja, S., Tsoukias, N. M., Solodushko, V., et al. (2012). Endothelial Ca2+ wavelets and the induction of myoendothelial feedback. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 302, C1226–C1242. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00418.2011

Tran, C. H., Vigmond, E. J., Plane, F., and Welsh, D. G. (2009). Mechanistic basis of differential conduction in skeletal muscle arteries. J. Physiol. 587, 1301–1318. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.166017

Tran, C. H., and Welsh, D. G. (2009). Current perspective on differential communication in small resistance arteries. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 87, 21–28. doi: 10.1139/Y08-104

Uhrenholt, T. R., Domeier, T. L., and Segal, S. S. (2006). Resolution of Ca2+ dynamics underlying conducted vasodilation: The Ca2+ wave. FASEB J. 20:A277.

Uhrenholt, T. R., Domeier, T. L., and Segal, S. S. (2007). Propagation of calcium waves along endothelium of hamster feed arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 292, H1634–H1640. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00605.2006

Willecke, K., Eiberger, J., Degen, J., Eckardt, D., Romualdi, A., Guldenagel, M., et al. (2002). Structural and functional diversity of connexin genes in the mouse and human genome. Biol. Chem. 383, 725–737. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.076

Yamamoto, Y., Klemm, M. F., Edwards, F. R., and Suzuki, H. (2001). Intercellular electrical communication among smooth muscle and endothelial cells in guinea-pig mesenteric arterioles. J. Physiol. 535, 181–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00181.x

Yashiro, Y., and Duling, B. R. (2000). Integrated Ca2+ signaling between smooth muscle and endothelium of resistance vessels. Circ. Res. 87, 1048–1054. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.11.1048

Keywords: gap junctions, calcium wavelets, constriction, inositol trisphosphate, potassium channels

Citation: Tran CHT, Kurjiaka DT and Welsh DG (2014) Emerging trend in second messenger communication and myoendothelial feedback. Front. Physiol. 5:243. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00243

Received: 01 April 2014; Accepted: 11 June 2014;

Published online: 30 June 2014.

Edited by:

Thomas Rich, University of South Alabama College of Medicine, USAReviewed by:

Jonathan Ledoux, Montreal Heart Institute, CanadaWenkuan Xin, University of South Carolina, USA

Kyle Adam Morrow, University of South Alabama Center for Lung Biology, USA

Copyright © 2014 Tran, Kurjiaka and Welsh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Donald G. Welsh, Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, GAA-14, Health Research Innovation Center, 3280 Hospital Dr. N.W., Calgary, AB T2N-4N1, Canada e-mail:ZHdlbHNoQHVjYWxnYXJ5LmNh

Cam Ha T. Tran

Cam Ha T. Tran David T. Kurjiaka

David T. Kurjiaka Donald G. Welsh

Donald G. Welsh