- Department of Geriatrics, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China

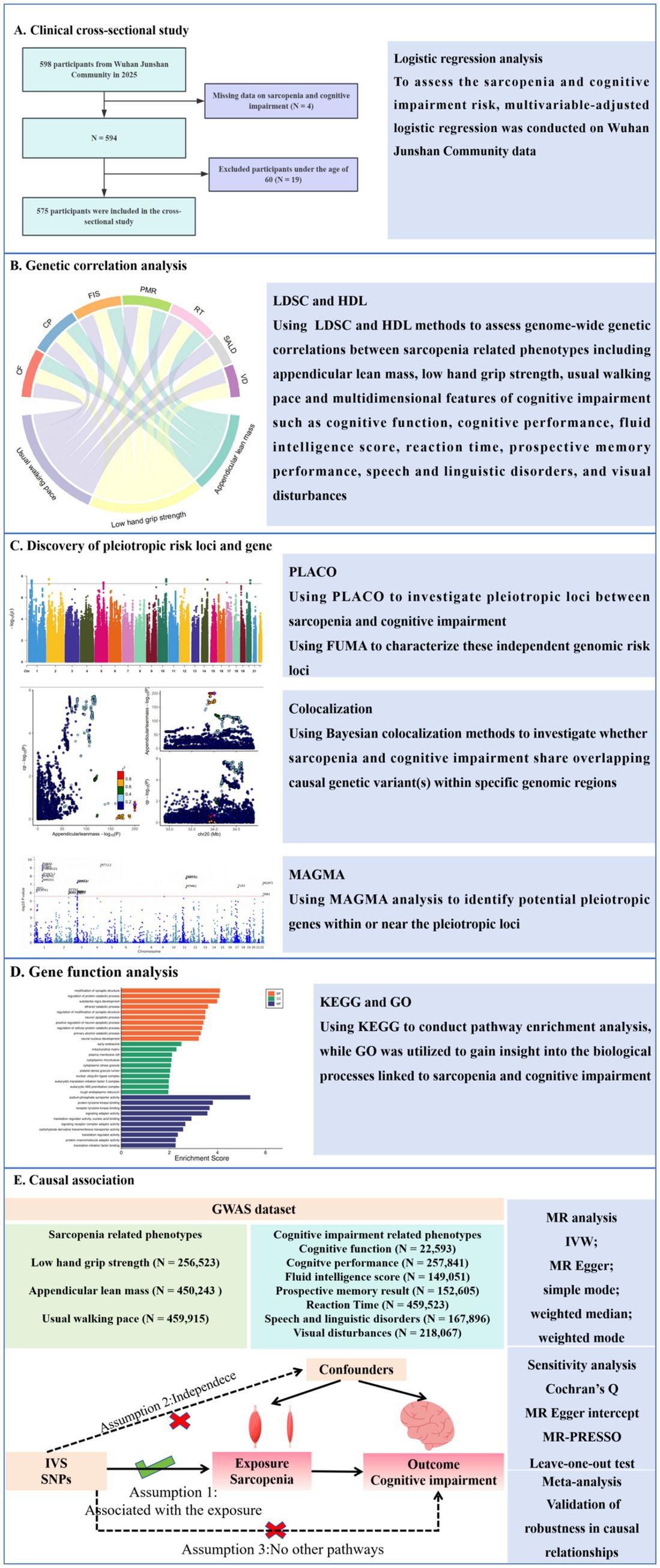

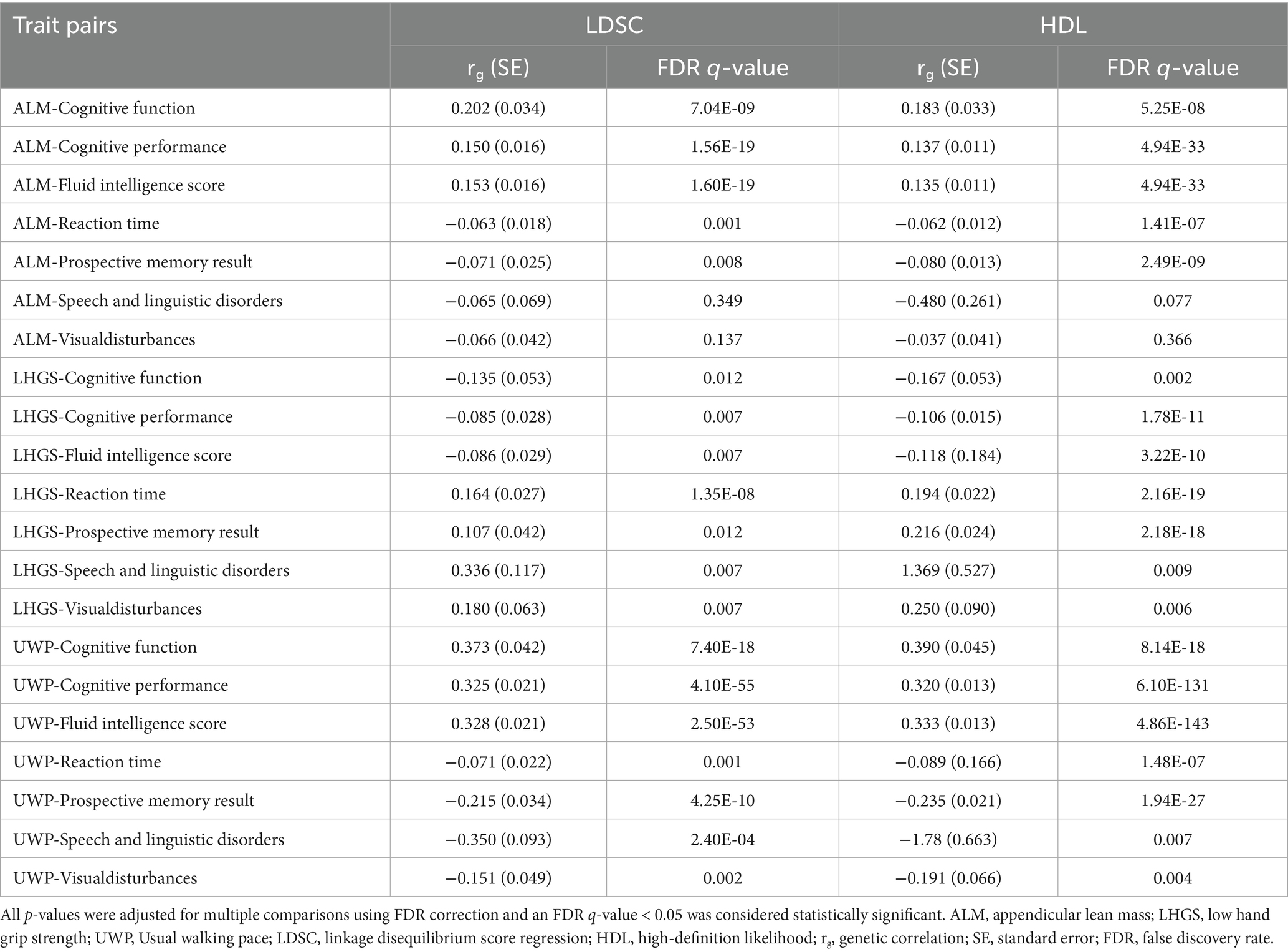

Objective: To comprehensively investigate the relationship between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment by examining their clinical associations, shared genetic architecture, and potential causal links, using a multidimensional approach.

Methods: To assess the sarcopenia and cognitive impairment risk, multivariable-adjusted logistic regression was conducted on Wuhan Junshan Community data. Utilizing large-scale GWAS summary statistics, we identified potential genetic overlaps between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment. Cross-trait pleiotropic analyses were conducted to uncover shared genetic loci and pleiotropic genes between these conditions. Comprehensive functional annotation and tissue-specific expression analyses were then performed to characterize the biological roles of these shared genetic factors. Finally, we employed Mendelian randomization (MR) approaches to examine potential causal relationships between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment.

Results: In this study, we recruited 575 participants for this observational study. Multivariable-adjusted logistic regression revealed a significant positive association between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment risk (OR = 3.26, 95% CI: 1.65 to 6.42). Genomic analysis revealed that there was a significant genetic correlation between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment, and 19 pairs of significantly correlated trait combinations were identified. Pleiotropic analysis revealed 79 risk loci and 428 pleiotropic genes such as FoxO3 and SLC39A8, which were enriched in neurodegenerative pathway and FoxO signaling pathway. MR analysis showed that appendicular lean mass and usual walking pace had potential causal protective effects on cognitive function, while low hand grip strength had the opposite effect.

Conclusion: This study provides evidence for both clinical and genetic links between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment, uncovering their potential biological mechanisms.

Introduction

Sarcopenia (characterized by progressive loss of muscle mass and function) and cognitive impairment demonstrate significant comorbidity in the elderly population, forming a vicious cycle that not only accelerates physical functional decline but also substantially impairs quality of life (Yuan and Larsson, 2023; Cipolli et al., 2023). Epidemiological studies reveal that sarcopenic patients have a 20.5% increased relative risk of developing mild cognitive impairment (MCI) compared to the general elderly population, with a significantly higher probability of progression to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Yang et al., 2023; Beeri et al., 2021). Notably, this association exhibits distinct bidirectional characteristics: patients with MCI experience an annual muscle mass loss rate 1.5 times higher than age-matched healthy controls, accompanied by more pronounced declines in muscle strength (Deng et al., 2021).

Against the backdrop of global population aging, the comorbidity of sarcopenia and cognitive impairment has emerged as a critical public health challenge requiring urgent attention. Current epidemiological data reveal a 14.2% prevalence of comorbid sarcopenia and cognitive impairment in adults aged 65 years and older (Zengarini et al., 2019). More alarmingly, the synergistic effects of these conditions demonstrate a remarkable multiplicative impact: clinical research data show that compared to patients with only cognitive impairment or sarcopenia, those with comorbid sarcopenia and cognitive impairment exhibit a greater mortality risk (OR = 2.12, 95% CI: 1.05–4.13) (Zengarini et al., 2019). These findings underscore the substantial burden this comorbidity places on healthcare systems. Although the association between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment has been widely explored, there is still insufficient high-quality evidence for the specific population of elderly people aged 60 and above in real community environments, and further supplementation is urgently needed.

The close association between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment may stem from shared pathophysiological mechanisms (Sui et al., 2020). The upregulation of chronic inflammatory mediators (IL-6, TNF-α) coordinately induces proteolytic muscle breakdown and hippocampal neurotoxicity (Sharma and Dabur, 2020; Swardfager et al., 2010). Insulin resistance exerts dual detrimental effects by impairing cerebral glucose metabolism and suppressing muscle protein synthesis (Umegaki et al., 2017). Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to oxidative stress, manifested by decreased NAD + levels and reduced respiratory chain complex activity, ultimately contributing to both muscle atrophy and neuronal damage (Arosio et al., 2023). Gut microbiota dysbiosis influences systemic function through the gut-brain-muscle axis, altering barrier permeability (Ticinesi et al., 2019). The decline in muscle-derived irisin and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) disrupts the critical cross-talk between muscle and nervous system, leading to impaired neuromuscular signaling pathways (Lee et al., 2023). Lifestyle factors are also likely to mediate the association between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment (Sui et al., 2020). Specifically, sedentary habits and poor nutrition could enhance chronic low-grade inflammation, which have been shown to promote muscle wasting and exacerbate neurodegeneration (Mo et al., 2023; Diniz et al., 2024). These pathogenic mechanisms interact synergistically, forming a vicious cycle that accelerates the progressive decline of both muscular and cognitive functions. Notably, single-disease interventions (cognitive training or resistance exercise) may demonstrate limited effectiveness in comorbid conditions (Casas-Herrero et al., 2022), highlighting the necessity to investigate the deeper shared pathological pathways.

To establish clinical context for sarcopenia-cognitive interactions, we first conducted an observational study in Wuhan Junshan Community (2025) that systematically evaluated the relationship between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment. Building on these clinical findings, we then investigated the shared genetic architecture between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment. Although genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have independently identified sarcopenia-associated genes (MYH1 and MYH2, which encode myosin) (Kedlian et al., 2024) and cognitive impairment risk loci (APOE and CLU, neurodegeneration-related genes) (Bellenguez et al., 2022), the shared genetic architecture between these two disorders remains to be elucidated, with several critical research gaps persisting: (1) whether cross-phenotype pleiotropic genetic variants exist; (2) how these shared genetic factors mediate the coordinated decline of the neuromuscular system through specific molecular pathways; and (3) whether their genetic correlations exhibit tissue-specific expression patterns. Elucidating these mechanisms will provide molecular targets for developing precision intervention strategies targeting the “muscle-brain axis.” The study flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

Materials and methods

Clinical study

The data were obtained from Wuhan Junshan Community in 2025. This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College Affiliated Union Hospital of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (0256–01). This study excluded individuals under the age of 60 and those lacking assessment of sarcopenia and cognitive impairment, and ultimately included 575 participants. Baseline characteristics in study population were summarized based on cognitive impairment status. Data were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and percentages (%) for categorical variables. The t-test or Mann–Whitney U test and the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test were used for continuous and categorical variables, respectively, to analyze differences in baseline characteristics between non-cognitive impairment and cognitive impairment individuals. Multivariable-adjusted logistic regression analysis was used to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for cognitive impairment to sarcopenia after adjusting for confounding factors.

Source of GWAS data

The open GWAS database established by the MRC Integrated Epidemiology Unit (IEU) provided the majority of the summary-level data used in this investigation (Hemani et al., 2018). Data for sarcopenia related phenotypes including appendicular lean mass (ALM), low hand grip strength (LHGS), usual walking pace (UWP) and multidimensional features of cognitive impairment such as cognitive function (CF), cognitive performance (CP), fluid intelligence score (FIS), reaction time (RT), prospective memory result (PMR), speech and linguistic disorders (SALD), and visual disturbances (VD) were derived from European ancestry (Supplementary Table 1 contains the complete phenotypic descriptions), with no sample overlap between the datasets of the pairwise traits.

Genetic correlation analysis

To investigate shared genetic architecture, we employed linkage disequilibrium score regression (LDSC) (Bulik-Sullivan et al., 2015) and high-definition likelihood (HDL) (Ning et al., 2020) methods to assess genome-wide genetic correlations between sarcopenia related phenotypes and multidimensional features of cognitive impairment. LDSC calculates SNP-specific linkage disequilibrium (LD) scores by summing squared correlations (r2) with neighboring variants within a 1-centimorgan window using reference panels (1,000 Genomes Project) (Abecasis et al., 2012), then estimates heritability through χ2 statistic regression while controlling for confounding biases. HDL enhances this approach by incorporating haplotype-level information from high-resolution references (UK Biobank) (Bycroft et al., 2018) within a likelihood framework, improving precision (30–50% efficiency gains) through refined modeling of regional LD complexity. Both methods were applied to quality-controlled HapMap3 SNPs (Duan et al., 2008), with HDL providing complementary validation of LDSC results in examining shared genetic architecture between these traits. To account for multiple hypothesis testing, we implemented Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) (Robertson et al., 2023) control, considering results with q-values below 0.05 as statistically significant.

Discovery of pleiotropic risk loci

Pleiotropic analysis under composite null hypothesis (PLACO) (Ray and Chatterjee, 2020) was employed to investigate shared genetic loci between sarcopenia-related traits and cognitive impairment measures using GWAS association statistics. Genome-wide significant pleiotropic variants were identified as single nucleotide variants (SNVs) meeting the rigorous PLACO significance criterion of p < 5 × 10−8. For comprehensive functional characterization of these independent genomic risk loci, we conducted subsequent bioinformatic analyses utilizing the Functional Mapping and Annotation (FUMA) platform (Watanabe et al., 2017).

Colocalization analysis

We performed genetic colocalization analysis to investigate whether sarcopenia and cognitive impairment share overlapping causal genetic variant(s) within specific genomic regions, thereby strengthening evidence for their biological linkage. Using Bayesian colocalization methods (Giambartolomei et al., 2014), we analyzed GWAS summary statistics for sarcopenia-related traits and multidimensional features of cognitive impairment. The analysis evaluated five competing hypotheses: the null hypothesis (H0) of no association with either trait; H1 (association with sarcopenia only); H2 (association with cognitive impairment only); H3 (independent associations for both traits); and H4 (shared causal variant). Loci demonstrating colocalization were identified when the posterior probability for H4 (PP4) exceeded our threshold of 0.75, indicating strong evidence that both traits are driven by the same underlying genetic variant(s) in these genomic regions.

Identification of pleiotropic gene and additional tissue specific analysis

To identify potential pleiotropic genes within or near the pleiotropic loci, we performed gene-level multi-marker analysis of genomic annotation (MAGMA) (De Leeuw et al., 2015) using our PLACO results, which provided biological insights into the pleiotropic SNPs. The MAGMA analysis p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using false discovery rate (FDR) correction, accounting for the number of genes tested per trait, with an FDR q-value threshold of < 0.05 defining statistical significance. The MAGMA analysis was conducted within the FUMA framework (Watanabe et al., 2017).

Pathway enrichment analysis was performed using the KEGG Orthology-Based Annotation System (version 3.0) (Bu et al., 2021), a comprehensive resource from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. To elucidate the biological mechanisms underlying sarcopenia and cognitive impairment, we employed Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis.

MR analysis and meta-analysis

MR represents an established epidemiological approach that leverages genetic variants (single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) as instrumental variables to infer causal relationships between exposures and outcomes (Liu et al., 2022). During the clumping procedure, we applied stringent thresholds for linkage disequilibrium (r2 < 0.001) and physical distance (>10 Mb) using the European population reference data from the 1,000 Genomes Project for LD calculation (Clarke et al., 2012). In our Mendelian randomization analysis, sarcopenia served as the exposure variable, with a stringent genome-wide significance threshold of p < 5 × 10−8 applied for instrumental variable selection (Chen et al., 2021).

To ensure the robustness of our MR causal estimates, we conducted comprehensive sensitivity analyses employing multiple methodological approaches (Burgess et al., 2017). The effect estimates were meta-analyzed using a DerSimonian-Laird random-effects model, with between-study heterogeneity evaluated through Cochran’s Q statistic (Bowden et al., 2018).

In MR studies, the inverse-variance weighted (IVW) estimates may be susceptible to bias from horizontal pleiotropy. To address this potential limitation, we implemented multiple pleiotropy-robust sensitivity analyses, including MR-Egger regression to assess and account for directional pleiotropic effects among the instrumental variables (Bowden et al., 2015). Statistical evidence of directional pleiotropy among the instrumental variables (IVs) was considered significant when the MR-Egger intercept term yielded a p-value < 0.05. Conversely, the absence of significant horizontal pleiotropy was concluded when the intercept p-value exceeded 0.05, indicating that the selected IVs satisfied the key MR assumption of no unbalanced pleiotropy. Prior to conducting each Mendelian randomization analysis, we implemented the MR-Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier (MR-PRESSO) method to identify and remove potential outlier variants that could distort causal estimates (Yeung et al., 2019). To verify robustness, we conducted leave-one-out sensitivity analyses.

To enhance statistical power, we performed a meta-analysis of multiple MR results. All analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.0).

Results

Characteristics of participants

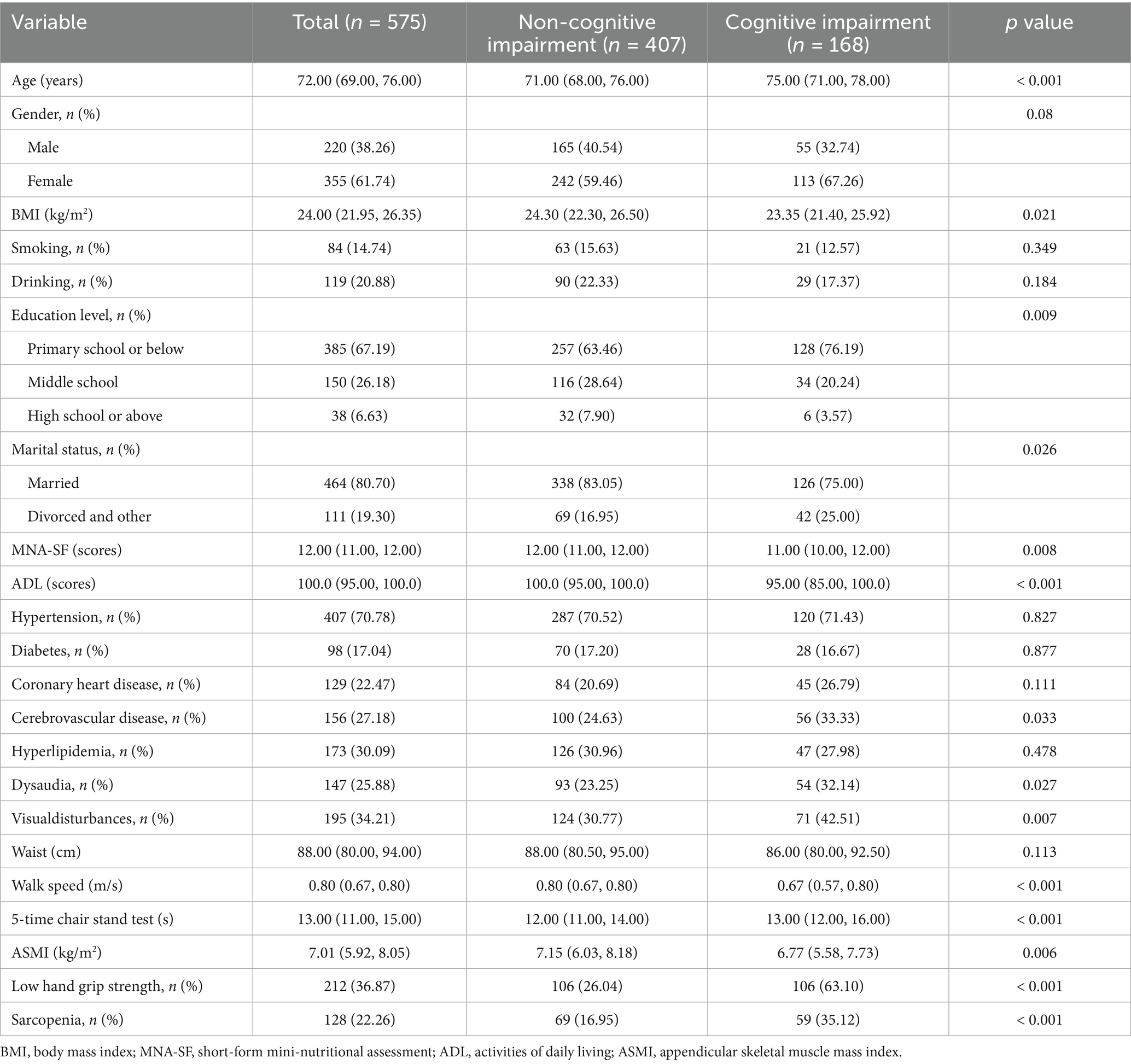

A total of 575 older adults were included in the cross-sectional analyses. The characteristics of the participants were shown in Table 1 according to cognitive impairment status. The prevalence of cognitive impairment was 29.2% among old people. Compared with those without cognitive impairment, individuals with cognitive impairment were more likely to be older (age: 75.0 vs. 71.0 years), slimmer (BMI: 23.35 vs. 24.30 kg/m2), higher risk of malnutrition (MNA-SF score: 11.00 vs. 12.00), lower levels of daily activities (ADL score: 95.00 vs. 100.0) and with educational background of primary school or below (76.19% vs. 63.46%). With regard to comorbidity, sarcopenic individuals were more likely to suffer from cerebrovascular disease (33.33% vs. 24.63%), dysaudia(32.14% vs. 23.25%), visualdisturbance (42.51% vs. 30.77%). The marital status of patients with cognitive impairment is mostly divorced or other (25.00% vs. 16.95%). Besides, patients with cognitive impairment have lower muscle mass (ASMI:6.77 vs. 7.15 kg/m2), slower walking speed (0.67 vs. 0.80 m/s), and longer time of 5-time chair stand test (13.00 vs. 12.00 s). The prevalence of sarcopenia (35.12% vs. 16.19%) is higher in cognitive impairment.

Clinical association between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment

The results of a multivariate regression analysis on the relationship between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment are shown in Table 2. The OR (95% CI) for cognitive impairment in sarcopenia old adults was 2.65 (95% CI: 1.76 to 3.99). The sarcopenia was significantly associated with cognitive impairment after adjusting for age, gender, BMI, education level, marital status, MNA-SF scores, ADL scores, cerebrovascular disease, dysaudia, visualdisturbances (OR = 3.26, 95% CI: 1.65 to 6.42, p < 0.001). We found similar results in the regression analysis of the relationship between low grip strength, low muscle mass and cognitive impairment (p < 0.05).

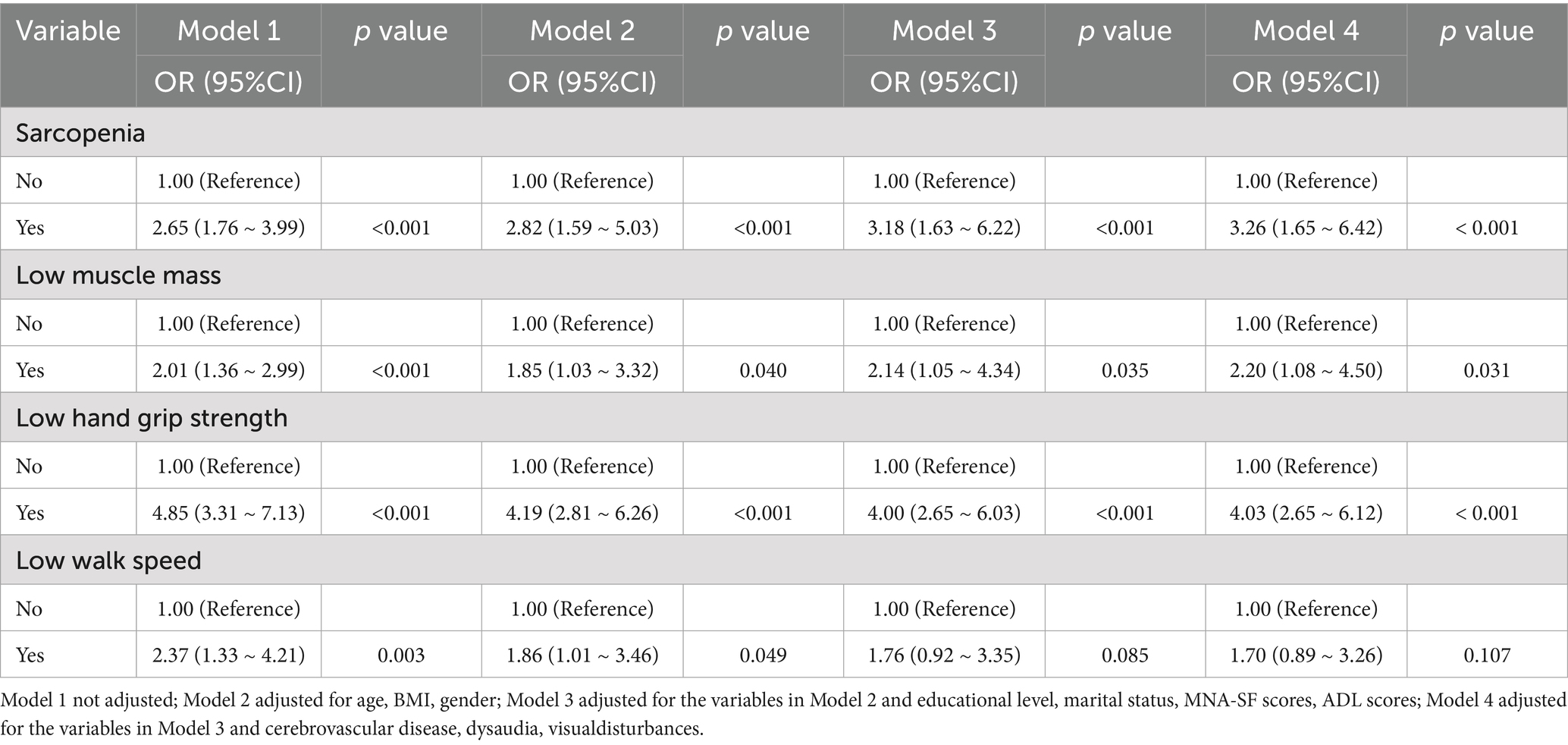

Genetic correlation between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment

Using LDSC analysis, we identified 19 trait pairs showing significant genetic correlations between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment phenotypes (FDR-adjusted p < 0.05). These findings demonstrate high consistency with results obtained from the HDL approach, further validating the existence of significant shared genetic architecture between these two phenotypes. Both ALM and UWP exhibited significant positive genetic correlations with cognitive function, cognitive performance, and fluid intelligence scores. Significant negative genetic correlations were observed between ALM/UWP and both reaction time and prospective memory performance. UWP additionally showed significant negative genetic associations with speech and linguistic disorders as well as visual disturbances. In contrast, LHGS displayed an inverse pattern, showing negative genetic correlations with cognitive function, cognitive performance and fluid intelligence scores, but positive correlations with reaction time, prospective memory performance, speech and linguistic disorders, and visual disturbances (Table 3; Supplementary Figure 1).

Identification of pairwise pleiotropic loci and genes

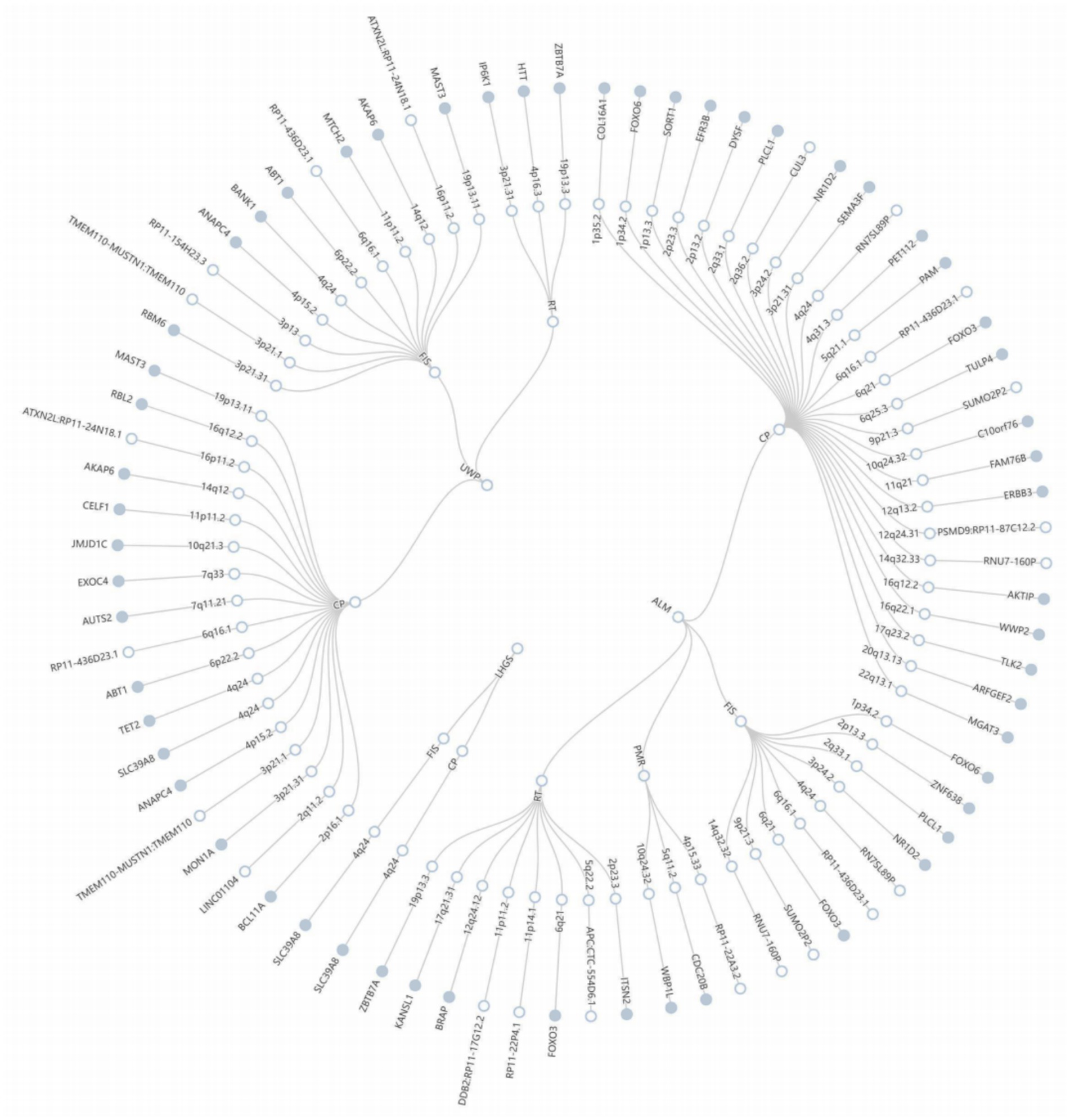

Building upon the evidence of shared genetic architecture between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment revealed through LDSC and HDL analyses, we employed the PLACO framework to detect genomic loci exhibiting pleiotropic effects across both conditions (Supplementary Figure 2). The QQ plots revealed close alignment between the observed and expected distributions of test statistics, providing no evidence for population stratification or other technical artifacts in our analyses (Supplementary Figure 3). The FUMA analysis identified 79 genome-wide significant pleiotropic risk loci (PPLACO < 5 × 10−8), distributed across 49 distinct chromosomal regions, demonstrating shared genetic influences between the studied phenotypes (Figure 2; Supplementary Table 2). Colocalization analysis revealed no shared genetic causal loci between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment (Supplementary Table 3). Through MAGMA, we identified 45 recurrent pleiotropic genes showing consistent associations across multiple trait pairs. Notably, RP11-436D23.1 emerged as the most prominent pleiotropic gene, associated with four trait pairs, followed by FOXO3 and SLC39A8 (each linked to three pairs). Additional significant pleiotropic genes included FOXO6, PLCL1, NR1D2, ZBTB7A, ANAPC4, ABT1, AKAP6, and MAST3 (all associated with two trait pairs).

Figure 2. The circular diagram presents pleiotropic loci and genes identified by PLACO. Note: Shared genes identified by MAGMA analysis are highlighted in blue. ALM, appendicular lean mass; LHGS, low hand grip strength; UWP, Usual walking pace.

Pleiotropic gene enrichment analysis

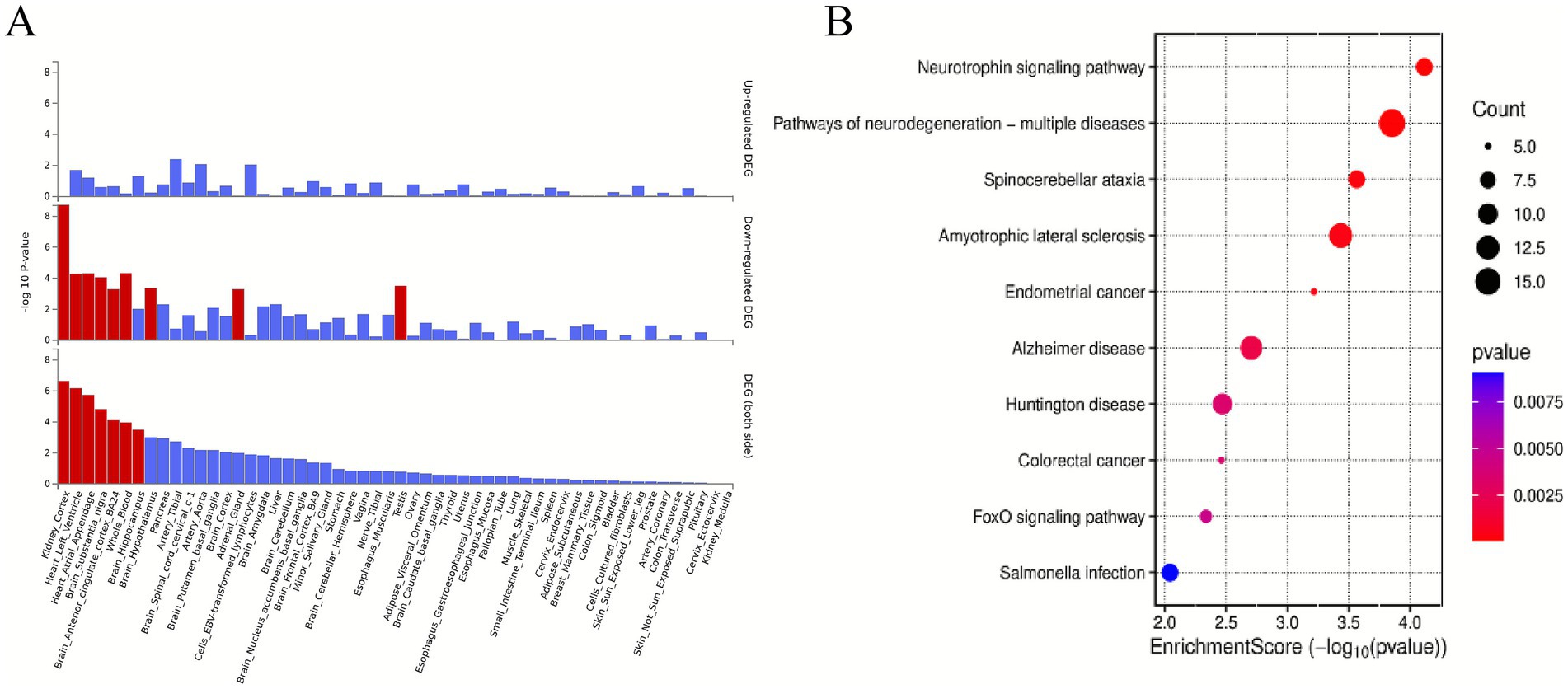

Integrative analysis using both PLACO and MAGMA approaches revealed a total of 428 statistically significant pleiotropic genes (FDR < 0.05) associated with both sarcopenia and cognitive impairment phenotypes (Supplementary Figure 4; Supplementary Table 4). The pleiotropic genes exhibited tissue-specific expression patterns across multiple organs, such as kidneys, heart, brain, and blood (Figure 3A). GO enrichment analysis of the 428 pleiotropic genes revealed significant overrepresentation in several key biological processes including modification of synaptic structure (p = 7.94 × 10−5), regulation of protein catabolism (p = 8.36 × 10−5), substantia nigra development (p = 0.0001), ethanol catabolism (p = 0.0002), and neuronal apoptosis (p = 0.0003) (Supplementary Table 5). The KEGG pathway analysis demonstrated significant enrichment for genes involved in neurotrophin signaling pathway (p = 7.64 × 10−5), pathways of neurodegeneration-multiple diseases (p = 0.0001), spinocerebellar ataxia (p = 0.0003), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (p = 0.0004), endometrial cancer (p = 0.0006), alzheimer disease (p = 0.002), huntington disease (p = 0.003), colorectal cancer (p = 0.003), FoxO signaling pathway (p = 0.0046) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Enrichment analysis. (A) Enrichment analysis revealed differentially expressed pleiotropic genes in 54 GTEx tissues. Red bars denote significant enrichments (Bonferroni-adjusted). (B) Top 10 significant types of pathways in terms of the GO and KEGG enrichment analyses. 54 GTEx tissues, 54 Genotype-Tissue Expression tissues; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; GO, Gene Ontology, KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

Causal effect of sarcopenia on cognitive impairment

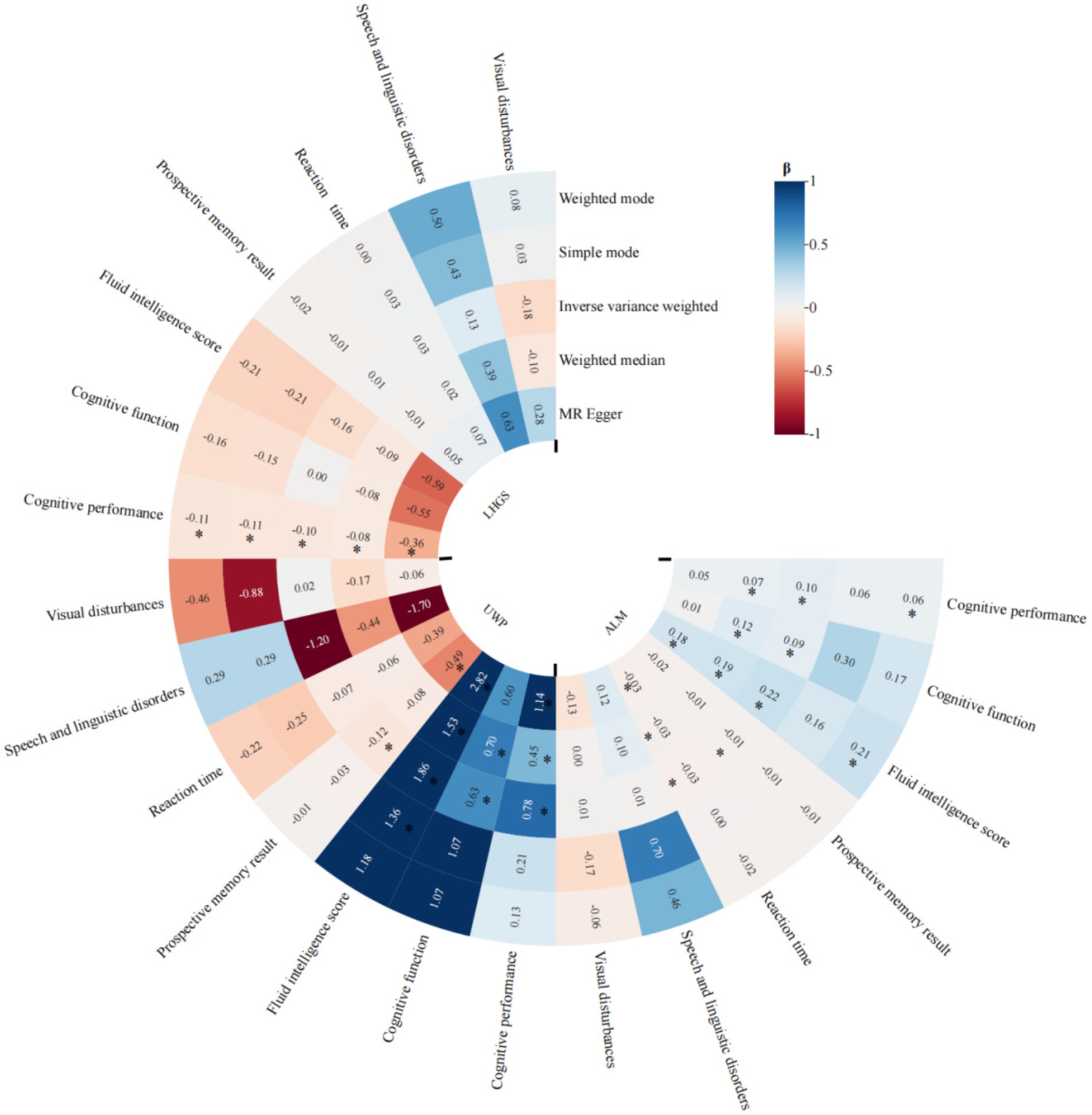

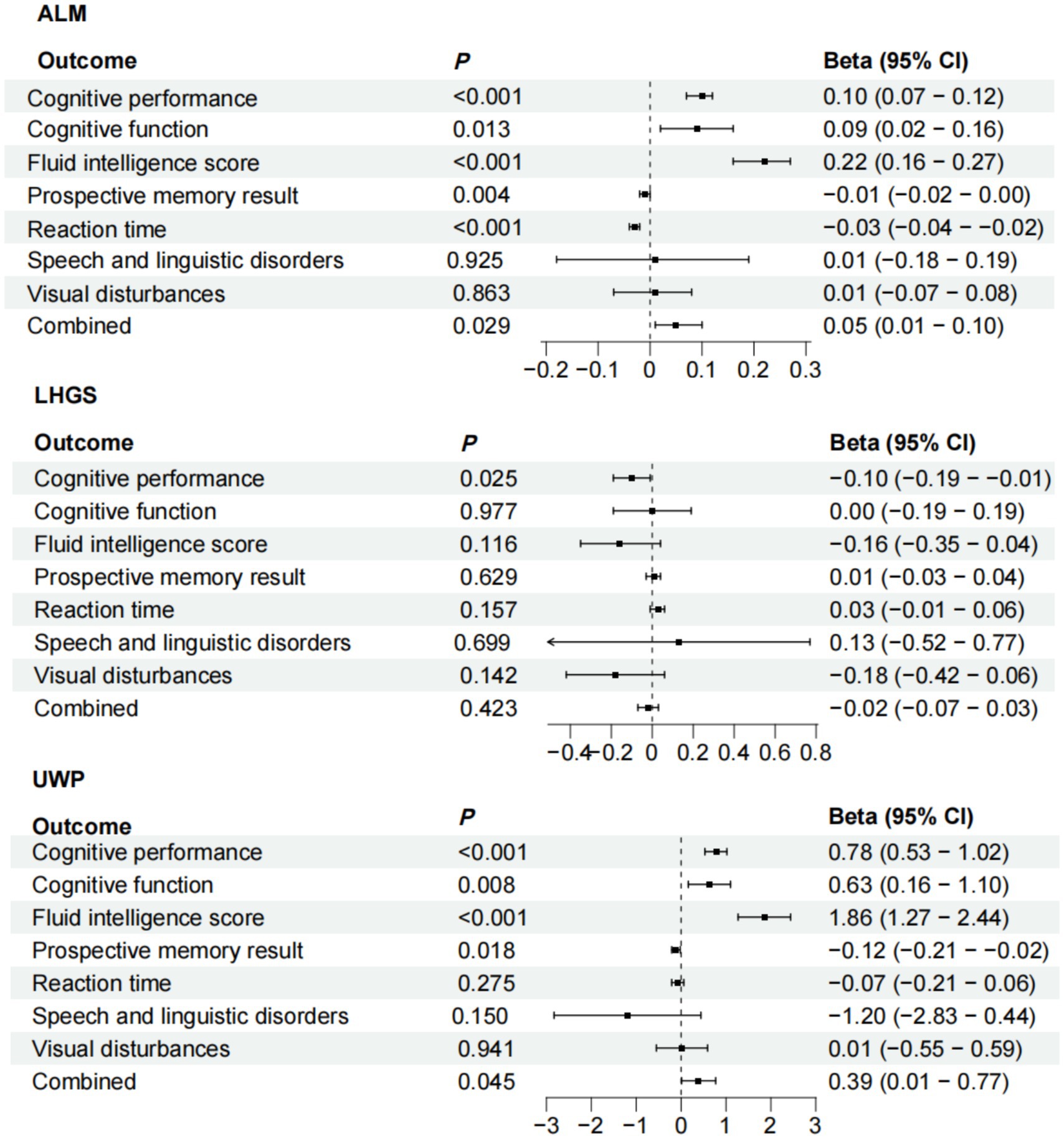

To strengthen our causal inference, we conducted comprehensive MR analyses examining the directional relationships between sarcopenia-related traits and cognitive domains. The IVW method revealed statistically significant causal associations of appendicular lean mass (ALM) with multiple cognitive measures including cognitive performance (p < 0.001), improved global cognitive function (p = 0.013), fluid intelligence scores (p < 0.001), reaction time (p = 0.004), and prospective memory performance (p < 0.001). Our analysis revealed that LHGS exhibited a causal link exclusively with cognitive performance (p = 0.025), with no significant associations detected for other cognitive impairment related traits. We also found potential causal relationship between the usual walking pace with cognitive performance (p < 0.001), cognitive function (p = 0.008), fluid intelligence score (p < 0.001), and reaction time (p = 0.018) (Figure 4). The meta-analyzed effect sizes demonstrated strong concordance with the primary MR findings across all examined traits, with the exception of LHGS which showed divergent results (Figure 5). We obtained similar results in the replicative cohort (Supplementary Figures 5, 6). All sensitivity results of MR are summarised in Supplementary Figures 7–9.

Figure 4. MR results of the causal effect of sarcopenia-related traits on 7 cognitive impairment outcomes. Date of ALM from ebi-a-GCST90000025, LHGS from ebi-a-GCST90007526, UWP from ukb-b-4711. And the cutoff level of LHGS was male < 30 kg, female < 20 kg by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP). MR: mendelian randomization; ALM, appendicular lean mass; LHGS, low hand grip strength; UWP, usual walking pace; EWGSOP, European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People; β: beta values; * means p < 0.05.

Figure 5. Meta-analysis of the causal associations between sarcopenia-related traits and 7 cognitive impairment outcomes. Date of ALM from ebi-a-GCST90000025, UWP from ukb-b-4711, LHGS from ebi-a-GCST90007526. And the cutoff level of LHGS was male < 30 kg, female < 20 kg by the EWGSOP. ALM, appendicular lean mass; LHGS, low hand grip strength; UWP, usual walking pace; EWGSOP, European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People.

Discussion

Clinical research results indicate that sarcopenia is significantly associated with cognitive impairment. Through an integrative multi-method genomic approach, we comprehensively examined both the shared genetic basis and putative causal associations between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment leveraging large-scale GWAS datasets. Our findings provide robust evidence for significant genetic correlations, pleiotropic mechanisms and causal relationships underlying these two conditions, shedding light on their interconnected biological pathways and potential clinical implications.

The present study demonstrates a robust association between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults. This association remained significant when examining individual components of sarcopenia (low grip strength and low muscle mass), reinforcing the link between muscle health and cognitive function. These results align with existing biological evidence suggesting shared pathways between muscle degeneration and cognitive decline, including chronic inflammation, metabolic dysregulation, and reduced neurotrophic support (Sui et al., 2020).

Through LDSC and HDL analysis, we found that there were 19 pairs of traits with significant genetic correlation between sarcopenia related phenotypes and cognitive impairment related traits. ALM and UWP were positively correlated with cognitive function, cognitive performance, and fluid intelligence, but negatively correlated with reaction time and prospective memory, suggesting that muscle mass and motor ability may have a protective effect on cognition. Conversely, our analyses revealed an inverse association between LHGS and cognitive function, while demonstrating positive associations with prolonged reaction time and increased risk of language disorders. This difference may reflect the difference in neuromuscular regulation mechanism between grip strength and other muscle phenotypes. In addition, the negative correlation of UWP with language disorders and visual abnormalities further supports the association between motor function and specific cognitive domains such as language and visual processing (Camargo et al., 2016). These results are consistent with epidemiological studies, that is, the decline of physical activity including slow walking speed is often accompanied by cognitive impairment (Wang et al., 2022), and the change of grip strength may more reflect the neurodegenerative process such as motor neuron or cerebellar dysfunction (Fellows et al., 2001).

By PLACO and MAGMA analysis, we identified 79 pleiotropic loci and 428 pleiotropic genes, among which FoxO3, SLC39A8 and RP11-436D23.1 were repeated in multiple trait pairs. FoxO3 is a key gene in the regulation of aging and oxidative stress (Cao et al., 2023). Previous studies have confirmed its role in muscle atrophy and neurodegenerative diseases (Aucello et al., 2009). SLC39A8 is involved in zinc ion transport. Abnormal zinc metabolism is associated with cognitive impairment and sarcopenia (Nebert and Liu, 2019). The enrichment analysis of these genes further revealed the common biological processes such as synaptic structure regulation, neuronal apoptosis and substantia nigra development, suggesting that neural plasticity and neuroprotective mechanisms may be the core link between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment (Ceccarelli and Solerte, 2025).

KEGG pathway analysis showed that pleiotropic genes were significantly enriched in neurotrophic factor signaling pathway, neurodegenerative disease pathways including Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease and FoxO signaling pathway. FoxO pathway plays an important role in muscle protein metabolism and neuron survival, which may affect muscle and brain function by regulating autophagy, inflammatory response and other mechanisms (Penniman et al., 2023; Asadi et al., 2025). In addition, the enrichment of genes related to ethanol metabolism suggests that lifestyle factors such as alcohol intake may aggravate the risk of comorbidity through epigenetic modification (Fernandez-Solà et al., 2007; Peng et al., 2020).

MR analysis showed that ALM and UWP had potential causal protective effects on cognitive impairment related traits including cognitive function, fluid intelligence, while LHGS was only related to cognitive performance. This result supports that muscle mass rather than pure grip strength has an independent impact on cognitive health, which may be related to muscle factors secreted by muscle such as irisin promoting neurogenesis through the blood–brain barrier (Wang et al., 2025). The causal effect of UWP is particularly significant because it comprehensively reflects muscle function, cardiopulmonary endurance and nervous system integration ability (Lin et al., 2024; Zukowski et al., 2024).

However, colocation analysis found no shared causal genetic loci, suggesting that the association between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment may be mediated by pleiotropic genes rather than direct causal mutations. This finding suggests that our treatment for common pathways such as FoxO or neurotrophic factor signaling may improve muscle and cognitive function at the same time, but simply improving grip strength may not delay cognitive decline (Goh et al., 2024; Sajan et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2025).

This study has the following limitations: firstly, the data are mainly based on the European population and need to be verified in other ethnic groups. Secondly, the functional mechanism of pleiotropic genes such as non-coding RNA RP11-436D23.1 is not clear. Thirdly, MR analysis cannot completely exclude potential confounding factors such as vascular risk or chronic inflammation. Finally, we did not explore whether diet quality, physical activity, and energy balance interact with genetic susceptibility affecting muscle and cognitive function.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence for both clinical links between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment. In addition, this study confirmed the shared genetic basis of sarcopenia and cognitive impairment through genetic analysis, and pleiotropic genes and neurodegenerative pathways are the core mechanisms of their association. Appendicular lean mass and walking pace may have a causal protective effect on cognitive function, while the effect of grip strength is more complex. In-depth research on the combined effects of genetics and lifestyle on sarcopenia and cognitive impairment might offer new insights into the treatment for sarcopenia and cognitive impairment.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: ieu open gwas.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Union Hospital Tongji Medical College Huazhong University of Science and Technology. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

KZ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. SH: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Formal analysis. ML: Investigation, Data curation, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. YZ: Software, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. WL: Visualization, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Validation. BL: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Software, Validation, Supervision. PH: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2025.1708170/full#supplementary-material

References

Abecasis, G. R., Auton, A., Brooks, L. D., DePristo, M. A., Durbin, R. M., Handsaker, R. E., et al. (2012). An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature 491, 56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632

Arosio, B., Calvani, R., Ferri, E., Coelho-Junior, H. J., Carandina, A., Campanelli, F., et al. (2023). Sarcopenia and cognitive decline in older adults: targeting the muscle-brain axis. Nutrients 15:1853. doi: 10.3390/nu15081853

Asadi, Y., Moundounga, R. K., Chakroborty, A., Pokokiri, A., and Wang, H. (2025). FOXOs and their roles in acute and chronic neurological disorders. Front. Mol. Biosci. 12:1538472. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2025.1538472

Aucello, M., Dobrowolny, G., and MUSARò, A. (2009). Localized accumulation of oxidative stress causes muscle atrophy through activation of an autophagic pathway. Autophagy 5, 527–529. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.4.7962

Beeri, M. S., Leugrans, S. E., Delbono, O., Bennett, D. A., and Buchman, A. S. (2021). Sarcopenia is associated with incident Alzheimer's dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and cognitive decline. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 69, 1826–1835. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17206

Bellenguez, C., KüçüKALI, F., Jansen, I. E., Kleineidam, L., Moreno-Grau, S., Amin, N., et al. (2022). New insights into the genetic etiology of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. Nat. Genet. 54, 412–436. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01024-z

Bowden, J., Davey Smith, G., and Burgess, S. (2015). Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through egger regression. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 512–525. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv080

Bowden, J., Hemani, G., and Davey Smith, G. (2018). Invited commentary: detecting individual and global horizontal pleiotropy in Mendelian randomization-a job for the humble heterogeneity statistic? Am. J. Epidemiol. 187, 2681–2685. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy185

Bu, D., Luo, H., Huo, P., Wang, Z., Zhang, S., He, Z., et al. (2021). KOBAS-i: intelligent prioritization and exploratory visualization of biological functions for gene enrichment analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W317–w325. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab447

Bulik-Sullivan, B. K., Loh, P. R., Finucane, H. K., Ripke, S., Yang, J., Patterson, N., et al. (2015). LD score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 47, 291–295. doi: 10.1038/ng.3211

Burgess, S., Bowden, J., Fall, T., Ingelsson, E., and Thompson, SG. (2017). Sensitivity analyses for robust causal inference from Mendelian randomization analyses with multiple genetic variants. Epidemiology 28, 30–42. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000559

Bycroft, C., Freeman, C., Petkova, D., Band, G., Elliott, L. T., Sharp, K., et al. (2018). The UK biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 562, 203–209. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z

Camargo, E. C., Weinstein, G., Beiser, A. S., Tan, Z. S., DeCarli, C., Kelly-Hayes, M., et al. (2016). Association of Physical Function with clinical and subclinical brain disease: the Framingham offspring study. J Alzheimer's Dis 53, 1597–1608. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160229

Cao, G., Lin, M., Gu, W., Su, Z., Duan, Y., Song, W., et al. (2023). The rules and regulatory mechanisms of FOXO3 on inflammation, metabolism, cell death and aging in hosts. Life Sci. 328:121877. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121877

Casas-Herrero, Á., Sáez De Asteasu, M. L., Antón-Rodrigo, I., Sánchez-Sánchez, J. L., Montero-Odasso, M., Marín-Epelde, I., et al. (2022). Effects of Vivifrail multicomponent intervention on functional capacity: a multicentre, randomized controlled trial. J. Cachexia. Sarcopenia Muscle 13, 884–893. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12925

Ceccarelli, D., and Solerte, S. B. (2025). Unravelling shared pathways linking metabolic syndrome, mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and sarcopenia. Meta 15:159. doi: 10.3390/metabo15030159

Chen, X., Kong, J., Pan, J., Huang, K., Zhou, W., Diao, X., et al. (2021). Kidney damage causally affects the brain cortical structure: a Mendelian randomization study. EBioMedicine 72:103592. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103592

Cipolli, G. C., DE ASSUMPçãO, D., Borim, F. S. A., Aprahamian, I., da Silva Falcão, D. V., Cachioni, M., et al. (2023). Cognitive impairment predicts sarcopenia 9 years later among older adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 24, 1207–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2023.05.008

Clarke, L., Zheng-Bradley, X., Smith, R., Kulesha, E., Xiao, C., Toneva, I., et al. (2012). The 1000 genomes project: data management and community access. Nat. Methods 9, 459–462. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1974

De Leeuw, C. A., Mooij, J. M., Heskes, T., and Posthuma, D. (2015). Magma: generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 11:e1004219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004219

Deng, Y., Zhao, S., Cheng, G., Yang, J., Li, B., Xu, K., et al. (2021). The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment among Chinese people: a meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology 55, 79–91. doi: 10.1159/000512597

Diniz, D. G., Bento-Torres, J., Da Costa, V. O., Carvalho, J. P. R., Tomás, A. M., de Galdino Oliveira, T. C., et al. (2024). The hidden dangers of sedentary living: insights into molecular, cellular, and systemic mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25:757. doi: 10.3390/ijms251910757

Duan, S., Zhang, W., Cox, N. J., and Dolan, M. E. (2008). FstSNP-HapMap3: a database of SNPs with high population differentiation for HapMap3. Bioinformation 3, 139–141. doi: 10.6026/97320630003139

Fellows, S. J., Ernst, J., Schwarz, M., Töpper, R., and Noth, J. (2001). Precision grip deficits in cerebellar disorders in man. Clin. Neurophysiol. 112, 1793–1802. doi: 10.1016/S1388-2457(01)00623-X

Fernandez-Solà, J., Preedy, V. R., Lang, C. H., Gonzalez-Reimers, E., Arno, M., Lin, J. C., et al. (2007). Molecular and cellular events in alcohol-induced muscle disease. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 31, 1953–1962. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00530.x

Giambartolomei, C., Vukcevic, D., Schadt, E. E., Franke, L., Hingorani, A. D., Wallace, C., et al. (2014). Bayesian test for colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004383

Goh, K. Y., Lee, W. X., Choy, S. M., Priyadarshini, G. K., Chua, K., Tan, Q. H., et al. (2024). FOXO-regulated DEAF1 controls muscle regeneration through autophagy. Autophagy 20, 2632–2654. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2024.2374693

Hemani, G., Zheng, J., Elsworth, B., Wade, K. H., Haberland, V., Baird, D., et al. (2018). The MR-base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. eLife 7:34408. doi: 10.7554/eLife.34408

Kedlian, V. R., Wang, Y., Liu, T., Chen, X., Bolt, L., Tudor, C., et al. (2024). Human skeletal muscle aging atlas. Nat. Aging 4, 727–744. doi: 10.1038/s43587-024-00613-3

Lee, H., Kim, S. Y., and Lim, Y. (2023). Annona muricata extract supplementation contributes to improve aberrant multi-organ energy metabolism via muscle-brain connectivity in diabetic mice. Nutrients 15:2559. doi: 10.3390/nu15112559

Lin, W. S., Hsu, N. W., Yang, S. H., Chen, Y. T., Tsai, C. C., and Pan, P. J. (2024). Predicting sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults through comprehensive physical fitness tests. BMC Geriatr. 24:932. doi: 10.1186/s12877-024-05528-7

Liu, Y., Xu, H., Zhao, Z., Dong, Y., Wang, X., and Niu, J. (2022). No evidence for a causal link between Helicobacter pylori infection and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Front. Microbiol. 13:1018322. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1018322

Mo, Y., Zhou, Y., Chan, H., Evans, C., and Maddocks, M. (2023). The association between sedentary behaviour and sarcopenia in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 23:877. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-04489-7

Nebert, D. W., and Liu, Z. (2019). SLC39A8 gene encoding a metal ion transporter: discovery and bench to bedside. Hum. Genom. 13:51. doi: 10.1186/s40246-019-0233-3

Ning, Z., Pawitan, Y., and Shen, X. (2020). High-definition likelihood inference of genetic correlations across human complex traits. Nat. Genet. 52, 859–864. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0653-y

Peng, B., Yang, Q., Joshi, R. B., Liu, Y., Akbar, M., Song, B. J., et al. (2020). Role of alcohol drinking in Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:2316. doi: 10.3390/ijms21072316

Penniman, C. M., Bhardwaj, G., Nowers, C. J., Brown, C. U., Junck, T. L., Boyer, C. K., et al. (2023). Loss of FoxOs in muscle increases strength and mitochondrial function during aging. J. Cachexia. Sarcopenia Muscle 14, 243–259. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.13124

Ray, D., and Chatterjee, N. (2020). A powerful method for pleiotropic analysis under composite null hypothesis identifies novel shared loci between type 2 diabetes and prostate cancer. PLoS Genet. 16:e1009218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009218

Robertson, D. S., Wason, J. M. S., and Ramdas, A. (2023). Online multiple hypothesis testing. Stat. Sci. 38, 557–575. doi: 10.1214/23-STS901

Sajan, M., Hansen, B., Ivey, R. 3RD, Sajan, J., Ari, C., Song, S., et al. (2016). Brain insulin signaling is increased in insulin-resistant states and decreases in FOXOs and PGC-1α and increases in Aβ1-40/42 and phospho-tau may abet Alzheimer development. Diabetes 65, 1892–1903. doi: 10.2337/db15-1428

Sharma, B., and Dabur, R. (2020). Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in regulation of skeletal muscle metabolism: a systematic review. Curr. Med. Chem. 27, 2161–2188. doi: 10.2174/0929867326666181129095309

Sui, S. X., Williams, L. J., Holloway-Kew, K. L., Hyde, N. K., and Pasco, J. A. (2020). Skeletal muscle health and cognitive function: a narrative review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22:255. doi: 10.3390/ijms22010255

Swardfager, W., LANCTôT, K., Rothenburg, L., Wong, A., Cappell, J., and Herrmann, N. (2010). A meta-analysis of cytokines in Alzheimer's disease. Biol. Psychiatry 68, 930–941. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.012

Ticinesi, A., Tana, C., and Nouvenne, A. (2019). The intestinal microbiome and its relevance for functionality in older persons. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 22, 4–12. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000521

Umegaki, H., Makino, T., Uemura, K., Shimada, H., Hayashi, T., Cheng, X. W., et al. (2017). The associations among insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, physical performance, diabetes mellitus, and cognitive function in relatively healthy older adults with subtle cognitive dysfunction. Front. Aging Neurosci. 9:72. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00072

Wang, X., Li, D., Li, X. Y., Lu, W., Ding, H., Qi, C., et al. (2025). Lecithin alleviates memory deficits and muscle attenuation in Chinese older adults and SAMP8 mice. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.). 12:e2405222. doi: 10.1002/advs.202405222

Wang, H., Zhang, H., Chen, Y., Cai, M., Guo, C., and Chen, P. (2022). Association between walking speed and cognitive domain functions in Chinese suburban-dwelling older adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14:935291. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.935291

Watanabe, K., Taskesen, E., VAN Bochoven, A., and Posthuma, D. (2017). Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat. Commun. 8:1826. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01261-5

Yang, Y., Xiao, M., Leng, L., Jiang, S., Feng, L., Pan, G., et al. (2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and correlation of mild cognitive impairment in sarcopenia. J. Cachexia. Sarcopenia Muscle 14, 45–56. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.13143

Yang, G., Yang, W., and Kiarasi, F. (2025). Polyphenol-based nutritional strategies combined with exercise for brain function and glioma control: focus on epigenetic modifications, cognitive function, learning and memory processes. Food Sci. Nutr. 13:e70758. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.70758

Yeung, C. H. C., Au Yeung, S. L., Fong, S. S. M., and Schooling, C. M. (2019). Lean mass, grip strength and risk of type 2 diabetes: a bi-directional Mendelian randomisation study. Diabetologia 62, 789–799. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-4826-0

Yuan, S., and Larsson, S. C. (2023). Epidemiology of sarcopenia: prevalence, risk factors, and consequences. Metabolism 144:155533. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2023.155533

Zengarini, E., Giacconi, R., Mancinelli, L., Riccardi, G. R., Castellani, D., Vetrano, D. L., et al. (2019). Prognosis and interplay of cognitive impairment and sarcopenia in older adults discharged from acute care hospitals. J. Clin. Med. 8:1693. doi: 10.3390/jcm8101693

Zukowski, L. A., Fino, P. C., Levin, I., Hsieh, K. L., Lockhart, S. N., Miller, M. E., et al. (2024). Age and beta amyloid deposition impact gait speed, stride length, and gait smoothness while transitioning from an even to an uneven walking surface in older adults. Hum. Mov. Sci. 93:103175. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2023.103175

Keywords: sarcopenia, cognitive impairment, genetic correlation, pleiotropic analysis, Mendelian randomization

Citation: Zhang K, Huang S, Liu M, Zhang Y, Li W, Luo B and He P (2025) Sarcopenia and cognitive impairment: a multidimensional study of clinical associations, shared genetics, and causal links. Front. Aging Neurosci. 17:1708170. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2025.1708170

Edited by:

Gilmara Gomes de Assis, Escola de Esporte e Lazer, Instituto Politécnico de Viana do Castelo, PortugalReviewed by:

Ciro Gaona, Alzheimer's Foundation of Venezuela, VenezuelaRoberto Cannataro, Magna Græcia University, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Zhang, Huang, Liu, Zhang, Li, Luo and He. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ping He, cGluZ2hlQGh1c3QuZWR1LmNu

Kemeng Zhang

Kemeng Zhang Sui Huang

Sui Huang Mengchen Liu

Mengchen Liu Ping He

Ping He