- 1Independent Researcher, Aberdeen, United Kingdom

- 2Boldswitch, Abuja, Nigeria

Introduction: Identity is the cornerstone of trust in modern society, yet current systems remain fragmented, document-based, and restricted by national boundaries. Physical passports, national identity cards, and paper records continue to define global mobility and access to services, despite being vulnerable to fraud, inefficiency, and exclusion. In today’s hyperconnected world, human mobility and digital finance have outgrown the boundaries of national identity systems. A traveller can fly from Kigali to London, study in Dubai, and work remotely for a company in Singapore, yet must repeatedly prove who they are through different passports, bank documents, and local IDs. This fragmentation slows innovation, increases compliance costs, and excludes millions who live or work across borders.

Methods: This paper argues for the establishment of a universal digital identity (UDI) hosted on a decentralised blockchain network. Under this model, each individual undergoes a one-time biometric enrolment capturing face, fingerprint, and voice data secured through cryptographic hashing and immutably stored on a blockchain ledger. A unique digital identity number (UDIN) is then generated, enabling retrieval of identity records worldwide by authorised institutions. Verification may occur in two ways: by presenting the UDIN or by frictionless biometric authentication, such as smiling at a camera or placing a finger on a scanner, instantly confirming identity against the blockchain.

Results: This system eliminates the need for physical documents, reduces fraud, lowers compliance costs, and enhances global mobility and inclusion. With one ID recognised globally, a person can open a bank account in any country, cross borders securely, and interact in the global economy without friction, paperwork, or repeated verification.

Discussion: The paper sets out the vision, necessity, operational framework, and implications of a blockchain-based UDI, arguing that such a transformation is both inevitable and essential for the future of the digital economy. The Universal Digital Identity (UDI) envisions a world where a single, verifiable digital credential enables seamless travel, banking, and access to services anywhere on the planet.

1 Introduction

Identity lies at the heart of human interaction, governance, and participation in economic systems. It determines who is entitled to rights, who can access services, and who is excluded. The simple but fundamental question “Who are you?” shapes outcomes in legal, political, and financial contexts (Clarke, 1994). In ancient societies, identity was verified through witnesses, seals, or reputation. Over time, documents such as birth certificates, travel passes, and eventually passports emerged as instruments of trust. In the modern era, nation-states have constructed complex systems of identification tied to citizenship, residency, and territorial authority.

Despite their historical significance, current identity systems are increasingly misaligned with the dynamics of globalisation and digitisation. Passports and national IDs remain rooted in territorial sovereignty, while human mobility, digital commerce, and financial interactions now occur across borders in real time (ICAO, 2015; World Bank, 2018). A traveler still needs to carry a physical passport, a migrant must repeatedly re-establish their identity in each new jurisdiction, and an individual seeking to open a bank account abroad faces lengthy document verification processes (Scott, 2019). These frictions slow down global mobility, increase compliance costs, and often exclude vulnerable populations from essential services (World Economic Forum, 2018).

Moreover, reliance on physical documents and centralised registries makes identity systems vulnerable to fraud, loss, and forgery. Stolen passports fuel black markets. Fake identity cards undermine elections. Forged documents enable money laundering and terrorism financing. Border checkpoints routinely identify compromised travel documents using INTERPOL’s Stolen and Lost Travel Documents (SLTD) database. In 2021, border and airline checks generated 1.7 billion queries resulting in 146,000 positive matches (“hits”) on reported-lost or stolen documents; more recent summaries indicate over 232,000 positive matches in 2023 as usage expanded. These figures evidence a persistent, global problem that credential-based verification seeks to reduce., creating risks for both security and trust.

At the same time, identity exclusion remains a pressing challenge. According to the World Bank’s Identification for Development (ID4D) initiative, nearly one billion people worldwide lack any form of government recognised ID. Without identification, individuals are unable to open bank accounts, enrol in schools, receive healthcare, or vote. This exclusion perpetuates cycles of poverty and marginalisation, particularly in developing countries.

Digital identity has become a cornerstone of the modern digital economy, underpinning access to financial services, healthcare, e-government platforms, and cross-border mobility. Yet, despite its importance, identity systems remain fragmented, centralised, and prone to exclusion. For example, while the European Union is developing the EU Digital Identity Wallet, and India has scaled its Aadhaar system, many regions in Africa and Latin America still lack interoperable frameworks that can serve citizens beyond national boundaries. This creates barriers for migrants, students, and global workers who require reliable identity verification across jurisdictions (Zhang and Chen, 2025).

Blockchain technology offers a promising pathway to resolve these challenges by enabling decentralised, tamper-proof, and globally verifiable digital identities. Unlike traditional systems, blockchain-based models allow individuals to maintain greater control over their personal data, while ensuring interoperability across borders (Tapscott and Tapscott, 2016; Hussain and Adeyemi, 2025). By aligning with international standards and regulatory sandboxes, such models could advance the vision of a Universal Digital Identity that enhances financial inclusion, improves trust in online transactions, and supports the growth of global digital commerce.

The digital economy magnifies these challenges. Financial technology platforms, e-commerce ecosystems, and global supply chains demand instant, reliable verification of identity. Yet existing methods uploading scans of documents, waiting days for verification, or relying on outdated KYC (Know Your Customer) processes are slow and inefficient. The mismatch between borderless digital transactions and bounded national identity systems is now a structural barrier to growth, inclusion, and security.

Blockchain technology provides an opportunity to reimagine identity as a universal, portable, and secure construct (Nakamoto, 2008; Xie et al., 2019). With its decentralised trust architecture, blockchain eliminates the need for central authorities to verify identity records. Its immutability ensures that identity records cannot be forged or tampered with, while cryptographic mechanisms enable privacy-preserving verification. When combined with biometric authentication face, fingerprint, and voice recognition (Jain et al., 2011) the result is a framework where identity is verified once and recognised everywhere.

This paper advances the case for a Universal Digital Identity (UDI), hosted on a decentralised blockchain network. Under this model, individuals undergo a one-time biometric enrolment process, during which their facial, fingerprint, and voice data are captured, encrypted, and hashed on the blockchain. A Universal Digital Identity Number (UDIN) is then generated. Thereafter, individuals can authenticate themselves either by presenting their UDIN or by direct biometric recognition such as walking up to an automated immigration gate, smiling at the camera, and being instantly recognised and cleared.

The vision is to replace the need for physical documents with frictionless digital verification. The contribution of this paper is fourfold:

1. To articulate the necessity of a universal, blockchain-based digital identity.

2. To outline a conceptual framework for how such a system could operate.

3. To analyse the benefits and risks of implementation.

4. To argue that the adoption of a UDI is not merely a possibility, but an inevitable evolution in the digital era.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 reviews the current literature on identity systems, digital identity initiatives, and blockchain as a trust infrastructure. Section 3 presents the proposed framework for a blockchain-based UDI. Section 4 discusses governance and policy considerations, while Section 5 examines benefits and implications. Section 6 considers challenges and limitations, and Section 7 argues for the inevitability of such a transformation. Section 8 concludes with a call for further research and global dialogue.

2 Literature review

2.1 Historical evolution of identity

The history of identity verification reflects broader changes in social organisation. In ancient societies, trust was personal: identity was vouched for by witnesses or community reputation. Seals and signet rings served as early forms of authentication. With the rise of states, written documents emerged as instruments of authority. Passports, which date back to the medieval period, allowed rulers to certify travellers legitimacy. Over centuries, identity became increasingly formalised, culminating in modern systems of national registration, passports, and civil registries.

The 20th century institutionalised identity as a cornerstone of nation-state governance. Birth certificates, driver’s licenses, and social security numbers became universal tools of administration. Yet, even as these systems expanded, they remained tied to geography and citizenship. Identity was something issued by the state, valid primarily within its jurisdiction, and requiring constant renewal or replacement when lost.

2.2 Modern limitations of document-based identity

Despite advances in security features such as biometrics and chips in e-passports, document-based identity faces three enduring limitations.

First, fragmentation undermines universality. Each nation has its own systems, standards, and registries, creating inefficiencies in cross-border recognition. A passport issued in one country may be accepted in another, but only after manual inspection and verification.

Second, vulnerability persists despite technology. Forged passports, counterfeit IDs, and stolen documents remain widespread. Even biometric passports can be cloned or exploited if underlying registries are compromised.

Third, exclusion leaves millions without any recognised identity. Marginalised populations, particularly in rural areas of developing nations, remain outside formal systems. Without identity, they are effectively invisible in the eyes of the state, excluded from rights and services.

2.3 Rise of digital identity initiatives

In response, governments and private actors have experimented with digital identity systems. National projects such as India’s Aadhaar, Estonia’s e-ID, and the European Union’s Digital Identity Wallet demonstrate the potential of biometrics and cryptography in identity management (Gelb and Clark, 2013; European Commission, 2021). These systems allow citizens to authenticate themselves digitally, often through mobile devices.

Yet, they share a common limitation: they are nationally bounded. Aadhaar is valid in India but not in the UK. Estonia’s e-ID is highly advanced but applies only to its citizens and e-residents. The EU’s efforts at harmonisation remain regional. No initiative has yet succeeded in creating a truly global identity that can be recognised across jurisdictions.

2.4 Blockchain as a foundation for universal identity

Blockchain’s unique characteristics position it as an ideal infrastructure for identity (Narula et al., 2018; Dunphy and Petitcolas, 2018). Its decentralisation removes reliance on a single authority. Its immutability ensures records cannot be altered or forged. Its cryptographic transparency allows verification without revealing raw data.

By storing encrypted biometric hashes on blockchain, identity can become both portable and secure. Verification requires only biometric authentication face, fingerprint, or voice which is matched against blockchain records in real time. This eliminates the need for physical documents while reducing fraud.

2.5 Gaps in current approaches

While the literature recognises the promise of digital identity, gaps remain. Existing digital ID systems are national or regional, not global. Efforts to establish self-sovereign identity frameworks, while innovative, often lack government adoption (Zwitter et al., 2020). Most importantly, the integration of blockchain with biometric authentication has not yet been realised at a universal scale.

This paper seeks to bridge that gap by proposing a conceptual framework for a global, blockchain-based identity system, one that is verified once and recognised everywhere, capable of replacing passports, ID cards, and multiple local credentials.

2.6 Decentralised vs. centralised approaches

Existing literature identifies two dominant paradigms in digital identity: centralised national ID systems and decentralised blockchain-based models. Centralised systems, such as Aadhaar in India, have achieved impressive scale but raise concerns about surveillance, data privacy, and vulnerability to single points of failure. In contrast, decentralised approaches emphasise self-sovereign identity (SSI), giving individuals ownership of credentials that can be verified without reliance on a single authority (Tobin and Reed, 2017; Sovrin Foundation, 2018).

Recent studies highlight that hybrid models combining state oversight with decentralised verification layers may offer the most practical path forward (Osei and Kamau, 2025). These models enable governments to retain regulatory oversight while ensuring that users benefit from the portability and security of blockchain. However, challenges remain in achieving interoperability across systems, especially when cross-border migration is considered. Scholars argue that interoperability requires global governance frameworks and technical standards that go beyond local solutions (Singh and Rao, 2025).

2.7 Comparative frameworks

Beyond national e-ID schemes, a growing ecosystem of decentralised identity standards exists. The W3C Decentralized Identifiers (W3C, 2019) (DID) Core specification and W3C Verifiable Credentials (W3C, 2022) (VC) provide the most widely recognised model for self-sovereign identity (Allen, 2016). Building on these, initiatives such as OIDC4VC (OpenID Foundation, 2023), Hyperledger Aries/Indy (Hyperledger Foundation, 2021; Dunphy and Petitcolas, 2018), and the Decentralized Identity Foundation (DIF, 2022) protocols enable secure credential exchange and interoperability. In Europe, the EUDI Wallet (eIDAS 2.0) (European Commission, 2024/2025) establishes a legal and technical framework for digital identity (European Commission, 2024; European Commission, 2025), while biometric-centric models such as Worldcoin’s World ID (Worldcoin Foundation, 2023) illustrate emerging approaches to large-scale biometric credentialing. Comparing the proposed UDI to these initiatives highlights both alignment, e.g., shared reliance on verifiable credentials and divergence, notably in scope (global portability) and biometric integration.

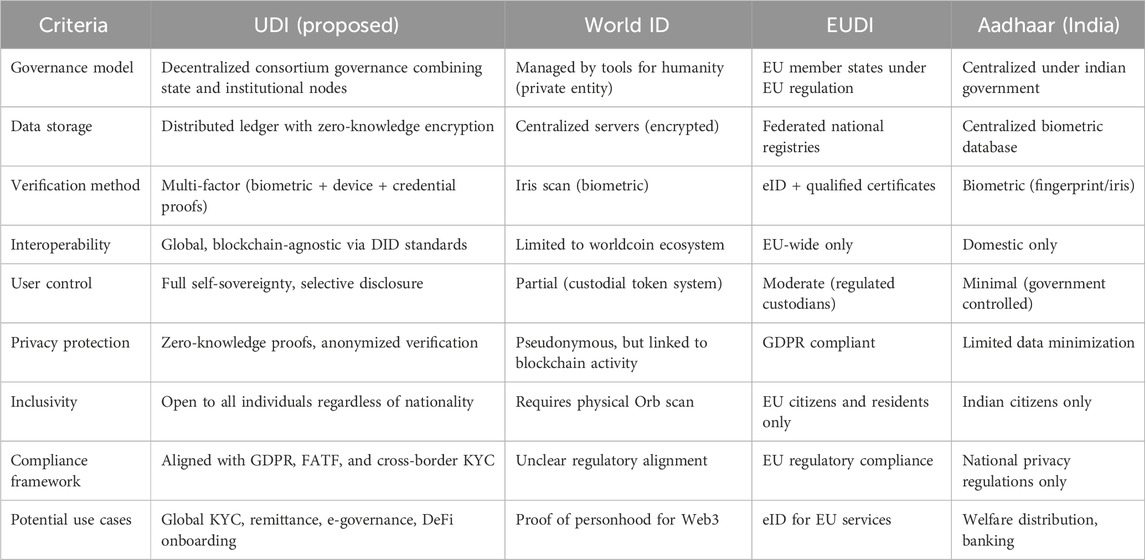

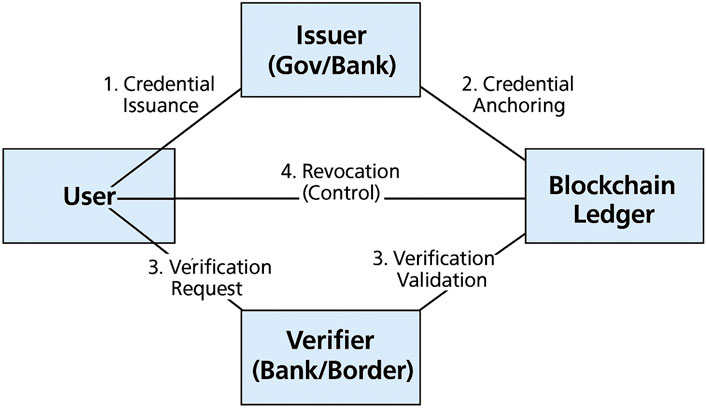

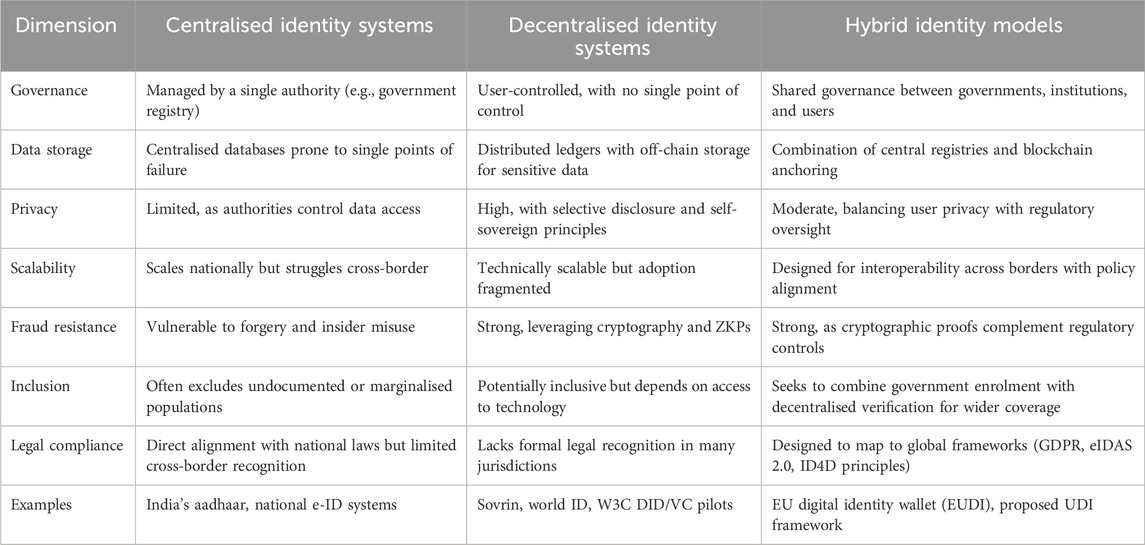

To contextualize the proposed Universal Digital Identity (UDI) framework, this section compares it with existing digital identity models including World ID, European Digital Identity (EUDI), and Aadhaar (India). While each system contributes meaningfully to digital verification, most remain geographically limited, centralized, or lack full interoperability. The UDI framework aims to integrate the strengths of these systems while overcoming their limitations through a decentralized, privacy preserving, and cross-border architecture. (See Tables 1, 2 for comparative frameworks; Figure 1 illustrates the blockchain identity protocol).

Table 2. Table provides a comparative overview of centralised, decentralised, and hybrid identity models, highlighting their governance, privacy, and compliance trade-offs.

2.8 Summary

Compared with existing frameworks, the proposed UDI system introduces a global interoperability layer that blends blockchain decentralization with legal recognizability and privacy preserving authentication. Unlike World ID and EUDI, which operate within specific ecosystems or regions, UDI emphasizes universal adoption and transparent governance. This comparative analysis reinforces UDI’s novelty as a hybrid framework capable of harmonizing identity, compliance, and cross-border usability.

3 The proposed framework

The Universal Digital Identity (UDI) system envisions a single, secure, and globally recognised digital credential, hosted on a decentralised blockchain. Its foundation is a one-time enrolment process followed by lifelong authentication, enabled by a combination of biometric recognition and cryptographic validation. This section outlines the architecture, processes, and real-world use cases of the proposed system.

3.1 Enrolment: one-time global verification

The cornerstone of the UDI is the enrolment process, which occurs only once in an individual’s lifetime. Unlike current identity systems where citizens repeatedly apply for documents, renew credentials, and undergo verification for each service, the UDI requires a single comprehensive verification event.

Age threshold and biometric maturity:

To ensure reliability and consistency, initial enrolment into the Universal Digital Identity (UDI) system is recommended from the age of 16 years, when the majority of biometric traits, including facial structure, fingerprints, and voice timbre, have reached long-term stability (Jain et al., 2011). Prior to this age, individuals may be issued a temporary dependent identity linked to a parent or guardian’s verified record. Upon reaching the age threshold, the dependent identity transitions to a full UDI through a standard enrolment process.

This approach ensures inclusivity for minors and refugees while maintaining biometric accuracy. The system also includes a ten-year renewal cycle, allowing biometric templates to be refreshed to reflect natural changes over time without altering the core Universal Digital Identity Number (UDIN).

During enrolment, multiple biometric modalities are captured simultaneously:

1. Facial Recognition–High-resolution scans of facial vectors are recorded. Unlike photographs, which can be forged, facial vectors are mathematical representations of unique features, resistant to manipulation.

2. Fingerprint Scanning–Prints are captured using secure, tamper-proof devices. Fingerprints remain among the most reliable identifiers due to their permanence.

3. Voice Recognition–Vocal samples provide an additional layer of biometric assurance, resistant to duplication when combined with liveness detection (e.g., requiring the user to speak random prompts).

Additionally, during enrolment, a high-resolution selfie photo is captured and securely stored as part of the encrypted biometric package.

This image serves as a visual reference for human-verifiable authentication at border gates, financial institutions, or aid agencies and complements algorithmic verification during biometric queries.

These biometric datasets are immediately processed using encryption algorithms and hashing functions. Importantly, raw biometric data never leaves the enrolment device; instead, a secure mathematical hash is created. This ensures that even if blockchain records are exposed, the underlying biometric templates remain unreconstructable and private.

Enrolment is carried out by accredited authorities government agencies, international organisations, or certified third party centres under strict governance protocols. Upon successful enrolment, the system generates a Universal Digital Identity Number (UDIN), a globally unique alphanumeric code tied to the individual’s blockchain record.

3.2 Blockchain registration: immutable trust

Once biometric data is encrypted, it is written to a blockchain ledger. Unlike centralised databases that are vulnerable to single points of failure or corruption, the blockchain provides distributed trust across multiple nodes maintained by governments, financial institutions, and global organisations.

Each blockchain record contains:

• The UDIN, serving as the universal reference code.

• Encrypted biometric hashes, representing the individual’s face, fingerprint, and voice templates.

• Metadata, including enrolment timestamp, issuing authority, and compliance status.

The blockchain operates as a permissioned consortium network, meaning only accredited institutions can operate nodes and validate transactions. This hybrid model combines the resilience of decentralisation with the accountability of regulated participation.

The immutability of the ledger ensures that once an identity is recorded, it cannot be altered or forged. Updates, such as changes in citizenship or legal status, can be appended to the record but never overwrite the original enrolment, preserving a permanent, auditable history of identity.

3.3 Verification and authentication: UDIN or biometric presence

Authentication within the UDI framework occurs in two complementary ways:

1. By UDIN–An individual provides their Universal Digital Identity Number to a verifying institution (e.g., a bank, hospital, or employer). The institution queries the blockchain to retrieve the encrypted record and conducts a live biometric match. For example, a customer opening an account in a foreign bank provides their UDIN; the bank scans their fingerprint and instantly matches it against the blockchain record.

2. By Direct Biometric Recognition–In many contexts, no UDIN input is needed. Instead, the individual’s biometrics serve as the key to the blockchain. Consider an automated immigration gate: a traveler simply walks up, smiles at the camera, and within seconds, the system captures their live facial vectors, queries the blockchain, and confirms identity. Similarly, in healthcare, a patient could place a finger on a scanner to access medical records, without presenting any number or card.

This dual capability ensures flexibility: the UDIN acts as a universal reference number when required, but in most daily interactions, the body itself is the password. For in-person verification, the stored selfie photo retrieved alongside encrypted biometric templates allows human officers such as immigration or banking officials to visually confirm that the individual matches the blockchain-linked record. This dual-mode verification (machine and human) strengthens trust and prevents identity spoofing in critical contexts like border control or humanitarian assistance. The act of being present smiling, speaking, or placing a finger becomes sufficient proof of identity.

3.4 Privacy and access control

A global identity system must guarantee privacy as rigorously as it guarantees security. In the UDI framework, privacy is ensured through several mechanisms:

• Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs) – These cryptographic protocols allow a verifier to confirm that an individual’s biometric matches the blockchain record without actually revealing the stored data.

• Selective Disclosure–Individuals can authorise institutions to access only the minimum required information. For instance, an age-restricted venue might verify that someone is over 18 without accessing their full identity record.

• Tiered Access Rights–Governments, banks, healthcare providers, and employers have different permission levels, ensuring no single entity can see or use all identity data.

Through these mechanisms, the UDI framework balances the need for universal trust with the individual’s right to privacy and autonomy.

A core concern in digital identity research is linkability: the risk that a universal identifier such as the UDIN could be used across domains, enabling surveillance and correlation of user activities (Zwitter et al., 2020). To mitigate this, future iterations should adopt pairwise pseudonymous identifiers derived from a master credential, as recommended by the W3C DID specification. Similarly, the permanent storage of biometric-derived hashes on-chain raises revocation and erasure challenges inconsistent with privacy-by-design principles (GDPR Articles 16–18). Best practices from Hyperledger Indy/Aries and DIF emphasise off-chain storage of biometrics with only revocable proofs anchored on-chain. Zero-knowledge proofs and selective disclosure schemes (Li et al., 2025) should be detailed to demonstrate unlinkability and compliance with minimisation. Incorporating these mechanisms would align the framework with privacy-by-design standards and strengthen its defensibility.

3.5 Technical architecture

The technical design of the UDI comprises three interconnected layers:

1. Enrollment Layer–Devices and protocols for capturing biometrics and generating encrypted hashes.

2. Blockchain Ledger Layer–A distributed, permissioned network maintaining immutable identity records.

3. Verification Layer–Interfaces for institutions and individuals, enabling authentication through UDIN or biometrics.

Off-chain storage is used for non-essential data, ensuring blockchain scalability. For example, documents such as academic certificates or driver’s licenses could be stored in encrypted repositories, linked to the blockchain identity via hashes.

3.5.1 Standards and interop

The wallet and credential layer follow W3C DID and Verifiable Credentials profiles, enabling cross-domain verification. Within the EU, alignment with the EU Digital Identity (EUDI) Wallet legal framework (Regulation (EU) 2024/1183 and 2025 implementing acts) allows mutual recognition of certified wallets, while other regions can interoperate via trust framework gateways and mapped assurance levels (European Commission, 2024; European Commission, 2025).

3.5.2 Protocol and system architecture

To illustrate the operational flow of the Universal Digital Identity (UDI), we present a specification-level protocol that maps the key interactions between users, issuers, verifiers, and the blockchain ledger. This protocol demonstrates how enrolment, credential issuance, verification, and revocation are managed within the system:

1. Identity Registration: The individual undergoes biometric capture and KYC verification with an authorised issuer (e.g., government agency or bank).

2. Credential Issuance and Anchoring: A cryptographic credential is created and anchored immutably on the blockchain ledger.

3. Wallet Control: The credential is stored in the individual’s digital wallet, giving them the ability to selectively disclose attributes.

4. Verification: When requested, the user authenticates via UDIN or biometric presence; the verifier checks credential validity against the blockchain.

5. Revocation and Updates: Individuals and issuers can revoke or append new credentials while preserving the immutable audit trail.

The diagram below illustrates the lifecycle of identity management in the UDI framework, showing how registration, credential issuance, blockchain anchoring, verification, and revocation interact across system participants.

3.6 Illustrative scenarios

To demonstrate usability, consider the following real-world scenarios:

• Immigration Control–A traveler approaches an automatic border gate. No passport is required. The camera scans their face, queries the blockchain, and authenticates them instantly. Security officers no longer inspect documents; instead, the blockchain ledger provides tamper-proof trust.

• Banking Access–A customer in a foreign country walks into a bank branch. Instead of presenting documents, they place their thumb on a scanner. The system retrieves their blockchain identity and verifies them in seconds. Account opening takes minutes, not weeks.

• Healthcare–A patient visits a hospital abroad. By simply scanning their fingerprint, their verified identity is retrieved, and linked medical records (if authorised) are accessed. Treatment is provided without administrative delays.

• E-Commerce–A consumer purchasing high-value goods online authorises payment by face scan through their device. The merchant verifies identity via blockchain, eliminating fraud while maintaining a seamless experience.

• Humanitarian Response–A refugee displaced by conflict, who has lost all documents, proves identity at a relief camp through biometric authentication. Aid workers retrieve their blockchain record, ensuring access to assistance, education, and future services.

3.7 Advantages of the framework

A universal, blockchain-anchored identity reduces repeated KYC frictions by allowing relying parties to verify a cryptographic credential rather than re-collecting documents at every touchpoint. Financial institutions benefit from faster onboarding and lower compliance overheads, while individuals experience materially shorter wait times and fewer identity failures in cross-border scenarios (World Bank, 2025). In public administration, verifiable credentials support near-instant entitlement checks and eligibility confirmations without exposing raw personal data, improving both service quality and auditability. Critically, the portability of credentials across jurisdictions directly addresses the needs of ∼304 million international migrants in 2024 (UN DESA, 2024/2025), many of whom must repeatedly re-establish identity. Compared with document checks at borders, credential validation against INTERPOL-integrated watchlists and national systems provides a more consistent fraud-detection surface, especially when combined with biometric liveness and revocation mechanisms (INTERPOL, 2024; EC, 2024/2025). Finally, selective-disclosure and zero-knowledge proof patterns enable “minimum-necessary” checks, improving privacy outcomes over conventional document sharing (Li et al., 2025).

3.8 Ethical design principles

To prevent misuse, the UDI must be built on ethical foundations:

• Consent–Enrolment and data sharing must require informed consent from individuals.

• Inclusion–Enrolment centres must be globally accessible, ensuring no one is excluded by geography or poverty.

• Accountability–Institutions misusing the system must face global sanctions.

• Transparency–Governance processes must be open, with mechanisms for appeal and redress.

3.9 Limitations and future work: towards empirical validation

While this paper sets out a conceptual framework, further validation is required. Future research should conduct protocol-level specifications with formal threat modelling, scalability benchmarks, and cost analyses. For instance, stress-testing enrolment throughput using simulated biometric capture pipelines (Jain et al., 2011) and benchmarking transaction latency against Layer-2 or permissioned blockchain platforms (Kshetri, 2021) would enable empirical evaluation of performance and security. Such assessments are necessary to substantiate claims relating to privacy, portability, unlinkability, fraud prevention, scalability, and cost-efficiency.

3.10 Summary

The proposed UDI framework transforms identity from a fragmented, document-based model into a universal, biometric, and blockchain-secured construct. By combining one-time enrolment, immutable blockchain storage, and frictionless verification via UDIN or direct biometric presence it ensures that identity is verified once and recognised everywhere. This framework lays the foundation for reimagining global mobility, finance, and social inclusion in the digital age.

4 Governance and policy considerations

While the technical feasibility of a blockchain-based Universal Digital Identity (UDI) is increasingly clear, the success of such a system ultimately depends on governance and policy frameworks. Identity is not merely a technical construct but also a political and legal one, deeply tied to questions of sovereignty, citizenship, and rights. A universal identity must therefore be supported by structures that ensure legitimacy, accountability, and ethical oversight. This section outlines key governance dimensions, including international oversight, national participation, legal harmonisation, and ethical safeguards.

4.1 International oversight

A truly universal identity system requires global coordination. Just as the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) sets standards for passports and airline safety, an intergovernmental body must oversee the UDI framework (ICAO, 2015). Such a body could operate under the auspices of the United Nations or as a new international consortium with participation from governments, international organisations, and accredited private actors (Lundqvist, 2017).

The functions of this international body would include:

• Standardisation–Defining protocols for biometric enrolment, blockchain consensus mechanisms, and verification processes.

• Certification–Accrediting enrolment authorities, ensuring that biometric capture devices and software meet global security standards.

• Interoperability–Ensuring that different national systems and blockchain implementations are compatible with the universal standard.

• Audit and Oversight–Monitoring compliance, preventing abuse, and maintaining trust in the system.

Without such global governance, the UDI risks becoming fragmented, with competing systems that replicate the inefficiencies of current passport and ID frameworks.

4.2 National sovereignty and participation

Although the UDI is universal in vision, it cannot bypass the sovereignty of states. National governments remain central to identity issuance and recognition. The challenge, therefore, is to design a system that balances global interoperability with national control.

In practice, this would mean:

• National Enrolment–Each government retains authority over enrolling its citizens and residents into the UDI system. Local agencies, under international certification, would conduct biometric verification.

• Legal Anchoring–National legislation would formally recognise the UDI as equivalent to, or a supplement to, existing passports and ID cards.

• Shared Governance–Governments would operate nodes in the blockchain network, ensuring that control is distributed rather than centralised in any single actor.

This hybrid model respects national sovereignty while ensuring that the resulting identity is universally recognised.

4.3 Comparative models of global governance

The world has seen successful examples of international governance frameworks that balance national authority with global interoperability. Three models are instructive:

1. ICAO and Passports–The ICAO sets global standards for machine-readable passports and biometric e-passports. Each state issues its own passport, but all comply with ICAO standards, enabling global recognition. A similar model could apply to the UDI, where states enrol identities but to a universal standard.

2. SWIFT in Banking–The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) provides a secure messaging system for international payments. While privately run, it is governed by banks and regulators globally. The UDI could adopt a consortium model where governments and key institutions jointly manage the blockchain network.

3. ICANN and the Internet–The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) manages domain names and IP addresses globally. Its multi-stakeholder governance incorporating governments, private actors, and civil society offers a precedent for distributed, non-state-centric oversight.

These models demonstrate that global coordination in technical and political domains is both possible and sustainable. The UDI could draw elements from each, creating a hybrid governance model suited to identity.

4.4 Legal harmonisation and data protection

One of the greatest challenges to a universal identity is the diversity of legal frameworks. Data protection laws vary widely: the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) emphasises strict privacy rights, while other regions have less developed protections. For the UDI to function, legal harmonisation is essential.

Key policy requirements include:

• Consent Frameworks–Individuals must provide informed consent for enrolment and for each instance of data use.

• Data Minimisation–Only essential biometric data should be stored, with zero-knowledge proofs enabling verification without exposure.

• Right to Redress–Individuals must have access to appeals processes if their identity is misused or their access denied.

• Cross-Border Recognition–Treaties or international agreements would formalise the recognition of the UDI across jurisdictions.

The legal design must ensure that the UDI is both effective and rights-respecting, preventing the emergence of a global surveillance tool.

The proposed design must explicitly align with regulatory frameworks. Under GDPR, biometric data constitutes “special category data” (Article 9), requiring strict safeguards. Article 16 ensures a right to rectification; Articles 17–18 enshrine rights to erasure and restriction, posing challenges for immutable blockchain records. These can be reconciled by anchoring only revocable proofs on-chain and keeping biometric templates in controlled, erasable off-chain environments. Similarly, the EUDI Wallet (eIDAS 2.0) mandates user control, consent, and selective disclosure, principles compatible with zero-knowledge proof mechanisms. The World Bank ID4D Principles require accessibility for those unwilling or unable to provide biometrics, suggesting fallback enrolment modalities. Explicit mapping of these requirements to the proposed UDI framework ensures compliance, strengthens legitimacy, and addresses potential human rights critiques.

4.5 Ethical safeguards

The ethical stakes of a universal identity system are high. Without safeguards, the UDI could become a mechanism of exclusion or authoritarian control. Ethical governance must therefore be embedded at every stage.

Principles include:

1. Inclusion–Enrolment centres must be accessible globally, including rural and marginalised populations. Special provisions should be made for refugees, stateless persons, and those historically excluded from identity systems.

2. Developmental Consideration–The framework recognises that biometric characteristics evolve with age. Enrolment from age 16 ensures physical and biometric maturity, while younger individuals may receive temporary dependent IDs. Periodic renewal every 10 years allows for secure biometric updates without loss of continuity, ensuring fairness and lifelong identity integrity.

3. Non-Discrimination–Identity verification must not be used to deny services based on race, religion, gender, or political affiliation.

4. Transparency–System governance, algorithms, and verification processes must be open to scrutiny.

5. Accountability–Institutions misusing the system should face sanctions, both nationally and internationally.

6. Human Oversight–Automated verification systems must include avenues for human review, preventing wrongful exclusions caused by technical errors.

By embedding these ethical safeguards, the UDI can advance human dignity rather than undermine it.

4.6 Public-private collaboration

Governments alone cannot deliver a universal identity system. The private sector particularly financial institutions, technology companies, and telecommunications providers plays a critical role. A successful governance model must therefore embrace public-private partnerships.

• Banks and Fintechs–As major consumers of identity verification for KYC compliance, they provide practical insights and help ensure adoption.

• Technology Firms–Providers of biometric hardware and blockchain infrastructure ensure technical robustness.

• Civil Society–Advocacy groups and NGOs must be included to safeguard rights and represent excluded populations.

Such collaboration ensures that the system is not only technically sound but also socially legitimate.

4.7 Risks of poor governance

If governance is weak, the risks are profound:

• Surveillance and Authoritarianism–Governments could use the UDI for mass tracking of citizens.

• Exclusion–Populations lacking access to enrolment infrastructure could be permanently excluded.

• Fragmentation–Competing systems could emerge, undermining universality.

• Loss of Trust–A single large-scale breach or misuse could delegitimise the entire system.

These risks underscore the importance of governance being built into the UDI from its inception, rather than as an afterthought.

4.8 Summary

Governance and policy considerations are as critical as technical design in the development of a blockchain-based Universal Digital Identity. A hybrid model, balancing international oversight with national sovereignty, is essential. Legal harmonisation, ethical safeguards, and public-private collaboration must underpin the system to prevent misuse and ensure legitimacy. Comparative governance models ICAO, SWIFT, ICANN demonstrate that global coordination is achievable. Without such frameworks, the UDI risks replicating the very inefficiencies and exclusions it seeks to solve.

5 Benefits and implications

The adoption of a blockchain-based Universal Digital Identity (UDI) has transformative potential across multiple domains, including governance, finance, individual empowerment, and global security. Beyond technical efficiency, the UDI carries profound social, economic, and political implications. This section examines the key benefits from the perspectives of governments, financial institutions, individuals, and the global system at large.

5.1 Benefits for governments

5.1.1 Streamlined immigration and border control

The UDI would revolutionise border management. Instead of relying on passports and visas, immigration systems could authenticate travelers instantly by scanning their faces or fingerprints. A traveler walking up to an automatic gate could simply smile at a camera; the system would verify their identity against the blockchain and clear them within seconds. This eliminates document inspection bottlenecks, reduces fraud, and accelerates throughput at busy airports and land borders.

5.1.2 Fraud prevention and national security

Fraudulent documents are a persistent problem for governments, enabling human trafficking, terrorism, and money laundering. With immutable blockchain records and biometric authentication, the risk of document fraud is significantly reduced through immutable credential anchoring, biometric liveness detection, and continuous revocation checks; residual risks persist at device and operator layers and require ongoing governance and auditing (INTERPOL, 2025). Each identity is anchored to unique biological markers, making impersonation nearly impossible.

5.1.3 Efficient public service delivery

Government services such as issuing licenses, disbursing welfare, or providing healthcare depend on accurate identification. The UDI would simplify these processes by allowing agencies to verify beneficiaries instantly. Fraudulent claims for social benefits could be reduced, while administrative efficiency increases.

5.1.4 Population management and planning

A universal identity system provides reliable demographic data, aiding in national planning and development. Accurate identity records can inform policy in education, healthcare, and infrastructure by giving governments clear insight into population size and distribution.

5.2 Benefits for financial institutions

5.2.1 Simplified know your customer (KYC) processes

Banks and financial service providers spend billions annually on KYC and anti-money laundering compliance. The UDI would replace repetitive document checks with instant biometric authentication. A customer in one country could open a bank account abroad within minutes by presenting their UDIN or scanning their fingerprint.

5.2.2 Reduced costs and risks

By eliminating document forgery and streamlining verification, banks reduce both operational costs and regulatory risks. Compliance becomes easier, as regulators can trust that each verified customer record corresponds to a tamper-proof blockchain identity.

5.2.3 Enabling cross-border finance

Currently, cross-border financial interactions are slowed by the lack of harmonised identity standards. A universal identity would allow financial institutions to operate seamlessly across jurisdictions. A migrant worker could open accounts, transfer funds, and build credit histories across multiple countries without re-verifying their identity each time.

5.2.4 Trust in digital banking and fintech

As financial services move increasingly online, establishing trust is critical. Biometric authentication linked to immutable blockchain records provides a higher level of assurance than current document-upload methods. This builds confidence for both institutions and customers, expanding the reach of digital banking.

5.3 Benefits for individuals

5.3.1 Frictionless global mobility

For individuals, the most visible benefit is freedom from physical documents. No more passports, ID cards, or repeated paperwork. Traveling abroad becomes as simple as passing through a gate and allowing the system to recognise you. This frictionless mobility enhances convenience, reduces stress, and aligns identity with the speed of modern life.

5.3.2 Inclusion for the unbanked and undocumented

Perhaps the most transformative impact is on inclusion. Nearly one billion people worldwide lack formal identity, barring them from basic services. By providing accessible enrolment centres and recognising identity at a global level, the UDI can integrate marginalised populations into financial, educational, and healthcare systems. For refugees and displaced persons, the UDI ensures continuity of identity even when physical documents are lost.

5.3.3 Enhanced privacy and control

Contrary to fears of surveillance, the UDI can enhance privacy by allowing individuals to selectively disclose information. A young adult entering an age-restricted venue need not reveal their name or address only proof that they are over the required age. Through cryptographic techniques such as zero-knowledge proofs, individuals control what is shared and with whom.

5.3.4 Portability and permanence

Identity is tied to the individual, not to a document. A lost passport or stolen ID card no longer jeopardises access to services. A person’s face, fingerprint, or voice remains with them always, providing a permanent anchor for their identity across borders and contexts.

5.4 Benefits for global security and trust

5.4.1 Countering identity theft and cybercrime

Identity theft is a growing global threat, costing billions annually in financial losses. By linking identity to immutable blockchain records and real-time biometric checks, the UDI system drastically reduces the potential for impersonation or stolen credentials.

5.4.2 Strengthening global cooperation

Shared identity infrastructure promotes cooperation between states. Just as ICAO standards unified passports, the UDI provides a universal trust layer. This fosters stronger collaboration in security, trade, and humanitarian response.

5.4.3 Resilience against systemic shocks

In times of crisis pandemics, wars, natural disasters identity systems are often disrupted. The blockchain-based UDI is decentralised and resilient, ensuring continuity of recognition even if national systems collapse. For displaced populations, this resilience is life-saving.

5.5 Wider socio-economic implications

5.5.1 Acceleration of global commerce

E-commerce, digital services, and international trade all rely on trust in identity. A universal identity system reduces friction in online transactions, enabling faster, more secure global commerce. Sellers can authenticate buyers instantly, reducing fraud while enhancing consumer confidence.

5.5.2 Empowering digital citizenship

The UDI redefines what it means to be a global citizen. Beyond national affiliations, individuals carry a secure, portable identity that grants them recognition anywhere in the world. This has profound implications for rights, mobility, and human dignity.

5.5.3 Redefining identity as a global public good

Identity becomes not a privilege granted by states but a global public good, accessible to all. This shifts the philosophical foundation of identity from citizenship to personhood, ensuring universal recognition of human beings regardless of geography or political status.

5.6 Summary

The Universal Digital Identity offers benefits that extend far beyond convenience. Governments gain efficiency and security. Financial institutions reduce costs and risks. Individuals enjoy frictionless mobility, enhanced inclusion, and greater privacy. Globally, the system strengthens trust, resilience, and cooperation. The implications are transformative: identity ceases to be a fragmented, document-based construct and becomes a universal, permanent, and secure feature of human existence.

6 Challenges and limitations

While the vision of a blockchain-based Universal Digital Identity (UDI) is compelling, its implementation faces significant challenges. These obstacles are not merely technical but also legal, ethical, political, and social. For the UDI to succeed, these issues must be addressed systematically, with proactive strategies to mitigate risks.

6.1 Technical challenges

6.1.1 Scalability and infrastructure

A global identity system would need to accommodate billions of individuals, each with multiple biometric templates and associated metadata. Public blockchains, in their current form, face scalability constraints in terms of transaction throughput and storage. Recording and verifying biometric hashes on a global scale would require innovations in layer-2 scaling solutions, sharding, and off-chain storage.

Furthermore, maintaining low-latency verification where an immigration gate or banking terminal must authenticate a person within seconds demands highly optimised infrastructure. If systems are slow or unreliable, adoption will falter.

6.1.2 Biometric accuracy and spoofing

Biometric technologies, while advanced, are not infallible. False positives and false negatives occur, particularly under poor environmental conditions (e.g., low lighting for facial recognition) (Parker and Boyne, 2020). Additionally, spoofing attacks such as masks, photos, or synthetic voice recordings pose risks. While liveness detection can mitigate these, ensuring robustness at a global scale is a formidable challenge.

6.1.3 Energy consumption

Some blockchain consensus mechanisms, particularly proof-of-work, consume vast amounts of energy. A global UDI system based on such models would be environmentally unsustainable. Transitioning to energy-efficient consensus algorithms such as proof-of-stake or delegated Byzantine fault tolerance is essential.

6.2 Legal and jurisdictional barriers

6.2.1 Sovereignty and recognition

Identity is traditionally the prerogative of the state. Convincing governments to cede partial control to an international blockchain framework poses political challenges. Some states may resist, fearing loss of sovereignty or control over their citizens. Without widespread recognition, the system risks fragmentation.

6.2.2 Data protection laws

Different jurisdictions impose varying standards for data protection. The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) mandates strict privacy rights, while many developing countries lack comprehensive data protection frameworks (United Nations and World Bank, 2018). Harmonising these differences to allow global recognition of blockchain-based identities is legally complex.

6.2.3 Liability and accountability

In the event of identity errors or system failures, questions of liability arise. If a person is wrongly denied entry at a border, or misidentified in a financial transaction, who bears responsibility the enrolling authority, the blockchain consortium, or the verifying institution? Without clear legal frameworks, disputes could undermine trust in the system.

6.3 Ethical and human rights concerns

6.3.1 Risk of surveillance

A universal identity system could, if misused, become the foundation for mass surveillance. Authoritarian regimes might exploit the system to track individuals, monitor dissent, or restrict freedoms. The very features that make the UDI secure immutability, universality, and biometric linkage could be weaponised against human rights.

6.3.2 Digital exclusion

Populations without access to biometric enrolment centres, smartphones, or internet connectivity risk being excluded. If the UDI becomes the prerequisite for accessing services, those unable to enrol may face even greater marginalisation.

6.3.3 Consent and autonomy

Biometric enrolment must be voluntary and informed. Yet in contexts of poverty or coercion, individuals may feel compelled to surrender their data. Ensuring meaningful consent across diverse cultural and socio-economic contexts is ethically challenging.

6.3.4 Algorithmic bias

Biometric systems have documented biases, particularly in facial recognition accuracy across different ethnicities and genders. If uncorrected, these biases could result in systematic exclusion or misidentification of marginalised groups, reinforcing existing inequalities.

6.4 Accessibility and equity

6.4.1 Infrastructure gaps

In many parts of the world, particularly in rural Africa, Asia, and Latin America, infrastructure for biometric enrolment is limited. Electricity, internet connectivity, and secure devices are not universally available. A global identity system must therefore include strategies for low-resource settings, such as offline verification tools and mobile enrolment units.

6.4.2 Cost of implementation

Establishing enrolment centres, developing blockchain infrastructure, and training personnel will require significant investment. For low-income countries, participation may be financially burdensome without international support. Ensuring equitable access requires global funding mechanisms, potentially underpinned by development banks or donor coalitions.

6.5 Trust and adoption

6.5.1 Institutional resistance

Governments, banks, and corporations may resist adoption if they perceive a loss of control or profit. Legacy systems create vested interests, and shifting to a new paradigm requires overcoming institutional inertia.

6.5.2 Public perception

Individuals may be reluctant to trust a global identity system, particularly given concerns about surveillance and privacy. Building public confidence requires transparent governance, public education campaigns, and demonstrable safeguards.

6.5.3 Risk of fragmentation

If multiple competing systems emerge each promoted by different governments or corporations the universality of identity will be lost. Interoperability standards must therefore be established early to prevent fragmentation.

6.6 Security risks

6.6.1 Cybersecurity threats

Although blockchain itself is secure, peripheral systems enrolment devices, verification terminals, and user interfaces are vulnerable to hacking. A compromised enrolment device could inject fraudulent identities, undermining trust in the system.

6.6.2 Insider threats

Even in permissioned blockchain networks, insiders with privileged access may misuse data. Strict audit trails, role-based access controls, and accountability mechanisms are essential.

6.6.3 Future-proofing against quantum computing

Quantum computing poses a long-term risk to current cryptographic algorithms. A global identity system must be designed with post-quantum cryptography in mind to ensure resilience over decades.

6.7 Summary

The challenges facing a blockchain-based UDI are profound but not insurmountable. Technical hurdles such as scalability, biometric spoofing, and energy use require innovation. Legal and political barriers demand international treaties and harmonisation. Ethical risks surveillance, exclusion, bias must be mitigated through design and governance. Accessibility and equity issues call for global solidarity in funding and infrastructure.

In short, the UDI is feasible but contingent upon careful, inclusive, and rights-based implementation. Recognising and addressing these challenges is essential to ensuring that the system fulfils its promise of universality, security, and inclusion, rather than replicating existing inequalities or creating new forms of control.

7 Why this future is inevitable

The vision of a Universal Digital Identity (UDI) hosted on a blockchain is not speculative fantasy; it is a logical progression of technological, social, and economic trends. Several converging forces make this transformation unavoidable.

7.1 Globalisation and mobility

Human mobility has reached unprecedented levels, with international travel, migration, and cross-border commerce continuing to grow. Yet identity systems remain nationally bounded. The tension between borderless movement and border-bound identity creates inefficiencies, insecurity, and exclusion. Just as the rise of global aviation demanded standardised passports, the rise of global mobility in the digital age demands a universal identity.

7.2 Digital finance and E-commerce

The financial system is rapidly digitising. Cryptocurrencies, mobile payments, and online banking all rely on trust in identity. Current verification methods scanned documents, email-based authentication, or local databases are inadequate in a borderless financial ecosystem. A blockchain-based UDI provides the trust infrastructure necessary for digital commerce to function at scale.

7.3 Technological convergence

Biometrics, artificial intelligence, and blockchain have reached maturity simultaneously. Biometric systems are now widely deployed, from smartphone authentication to national ID programs. Blockchain has demonstrated its capacity to provide secure, immutable, and decentralised record-keeping. Artificial intelligence enhances biometric recognition accuracy and fraud detection. Together, these technologies make a universal identity both feasible and desirable.

7.4 Lessons from history

History demonstrates that infrastructures of trust evolve in response to societal needs. The printing press enabled passports and standardised records. The telegraph and postal systems enabled global financial exchanges. The internet created digital communication across borders. A universal identity system is the next step in this lineage a global standard for trust in the digital age.

7.5 The inevitability of standardisation

Whenever global systems emerge, standardisation follows. Aviation, telecommunications, the internet, and financial transactions all transitioned from fragmented local systems to global standards. Identity will follow the same trajectory. Competing frameworks may arise initially, but eventually, efficiency and necessity will drive consolidation into a universally recognised standard.

In this sense, the UDI is not a question of if but when. The convergence of technology, globalisation, and human necessity ensures that a blockchain-based universal identity is the natural next stage in the evolution of human society.

8 Conclusion and future research

This paper has set out the vision for a blockchain-based Universal Digital Identity: a single, globally recognised credential verified once and recognised everywhere. By combining biometric authentication with blockchain immutability, the UDI offers a secure, portable, and inclusive alternative to fragmented national systems. Verification can occur either by presenting a Universal Digital Identity Number (UDIN) or through frictionless biometric recognition, such as facial or fingerprint scans.

This study highlights the potential of blockchain-based frameworks in shaping a borderless digital identity system. By addressing challenges in interoperability, privacy, and governance, blockchain can enable new standards of trust that extend beyond national jurisdictions. Such systems are particularly relevant for global populations who are traditionally excluded from mainstream identity verification, including migrants, refugees, and the underbanked.

Moving forward, future research should focus on testing hybrid models within regulatory sandboxes, conducting cross-border pilot programs, and developing frameworks for privacy-preserving data sharing. In doing so, policymakers and technologists can ensure that Universal Digital Identity is not just a theoretical construct, but a practical tool for enhancing inclusion and economic growth in the digital age (Li et al., 2025; Osei and Kamau, 2025).

The potential benefits are profound. Governments would achieve more efficient border control and service delivery. Financial institutions would reduce compliance costs and expand cross-border access. Individuals would gain frictionless mobility, enhanced inclusion, and permanent recognition, regardless of geography. Globally, the UDI would strengthen trust, resilience, and cooperation.

Yet the challenges are equally significant. Technical issues such as scalability and biometric spoofing must be resolved. Legal and jurisdictional conflicts over sovereignty and data protection require harmonisation. Ethical risks surveillance, exclusion, and algorithmic bias must be mitigated through governance, transparency, and oversight. Ensuring equity for marginalised populations is essential to avoid deepening existing inequalities.

Future research must focus on:

1. Pilot Programs–Testing UDI frameworks in regional or sectoral contexts (e.g., cross-border banking in Africa or refugee identity systems under UN agencies).

2. Post-Quantum Security–Developing cryptographic methods resilient to future threats.

3. Governance Models–Exploring hybrid approaches that balance international oversight with national sovereignty.

4. Ethical Design–Embedding human rights principles, fairness, and inclusion into technical and policy design.

5. Economic Analysis–Assessing the cost-benefit impacts of UDI adoption on governments, institutions, and individuals.

The future of identity is digital, borderless, and inevitable. The blockchain-based UDI is not merely a technological innovation but a societal necessity. It redefines identity as a global public good anchored not in documents or geography, but in the individual themselves.

The lifecycle management of biometric data, including enrolment from age 16 and scheduled ten-year renewals, ensures that the Universal Digital Identity remains both technically resilient and biologically adaptive, reflecting natural human development while preserving global continuity.

In time, carrying a physical passport will seem as archaic as traveling with handwritten letters of introduction. The act of being oneself smiling at a camera, pressing a finger, or speaking a phrase will be sufficient proof of identity. The UDI represents not only a new technology but a new chapter in the human story: the universal recognition of personhood in a connected world.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

GA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Visualization.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author is a founder of Boldswitch, a fintech company.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allen, C. (2016). “The path to self-sovereign identity,” in CoinDesk. Available online at: https://www.coindesk.com/path-self-sovereign-identity (Accessed August 18, 2025).

Clarke, R. (1994). Human identification in information systems: management challenges and public policy issues. Inf. Technol. and People 7 (4), 6–37. doi:10.1108/09593849410077779

Decentralized Identity Foundation (DIF) (2022). Specifications and working groups. Available online at: https://identity.foundation/ (Accessed September 30, 2025).

Dunphy, P., and Petitcolas, F. A. P. (2018). A first look at identity management schemes on the blockchain. IEEE Secur. and Priv. 16 (4), 20–29. doi:10.1109/MSP.2018.3111247

European Commission (2021). Proposal for a European digital identity framework. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1183 establishing a framework for a european digital identity (EUDI wallet). Official J. Eur. Union, L.

European Commission (2025). Implementing acts for the European digital identity wallet. Brussels: European Commission.

Gelb, A., and Clark, J. (2013). Identification for development: the biometrics revolution. Washington, DC: Centre for Global Development. Centre for Global Development Working Paper 315.

Hussain, M., and Adeyemi, K. (2025). Interoperability in decentralised identity systems: a cross-border framework. Front. Blockchain.

Hyperledger Foundation (2021). Hyperledger aries framework. San Francisco: Linux Foundation. Available online at: https://www.hyperledger.org/ (Accessed September 30, 2025).

International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) (2015). Machine readable travel documents (doc 9303). Montréal: ICAO.

INTERPOL (2025). Lost and stolen travel documents database annual summary 2025. Lyon: INTERPOL General.

Kshetri, N. (2021). Blockchain and digital identity: opportunities and challenges. IT Prof. 23 (1), 12–18. doi:10.1109/MITP.2020.3041980

Li, X., Zhao, Y., and Kumar, R. (2025). Privacy-preserving mechanisms in blockchain digital ID. IEEE Access 13.

Lundqvist, T. (2017). Blockchain, digital identity and the future of financial services. J. Payments Strategy and Syst. 11 (3), 278–286.

Nakamoto, S. (2008). Bitcoin: a peer-to-peer electronic cash system. Available online at: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf (Accessed August 18, 2025).

Narula, R., Hardjono, T., and Pentland, A. (2018). Towards a unified digital identity system. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

OpenID Foundation (2023). OpenID for verifiable credentials (OIDC4VC). Available online at: https://openid.net/specs/ (Accessed September 30, 2025).

Osei, F., and Kamau, P. (2025). Decentralised identity and the future of African FinTech. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 72.

Parker, M. J., and Boyne, J. (2020). Ethical considerations in biometric identity management. AI and Soc. 35 (2), 355–368. doi:10.1007/s00146-019-00887-9

Scott, D. (2019). Digital identity and financial inclusion: impacts, opportunities, and risks. Washington, DC: World Bank. World Bank ID4D Working Paper.

Singh, A., and Rao, D. (2025). Digital identity for migrants: a blockchain approach to inclusive finance. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 33 (2).

Tapscott, D., and Tapscott, A. (2016). Blockchain revolution: how the technology behind bitcoin is changing money, business, and the world. New York: Penguin.

Tobin, A., and Reed, D. (2017). he inevitable rise of self-sovereign identity. Utah: Sovrin Foundation Press.

United Nations and World Bank (2018). Principles on identification for sustainable development: toward the digital age. Washington, DC: World Bank.

W3C (2019). Verifiable credentials data model 1.0. World Wide Web Consort. Recomm. Available online at: https://www.w3.org/TR/vc-data-model/ (Accessed September 30, 2025). Available online at: https://www.w3.org/TR/did-core/.

W3C (2022). Decentralized identifiers (DID) v1.0. World Wide Web Consort. Recomm. Available online at: https://www.w3.org/TR/did-core/ (Accessed September 30, 2025). Available online at: https://www.w3.org/TR/vc-data-model-2.0/.

World Bank (2018). The state of identification systems worldwide: a country-by-country overview. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank (2025). ID4D global dataset. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online at: https://id4d.worldbank.org/ (Accessed September 30, 2025).

World Economic Forum (2018). Identity in a digital world: a new chapter in the social contract. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

Worldcoin Foundation (2023). World ID: a global identity protocol. Worldcoin White Paper. Available online at: https://worldcoin.org/ (Accessed September 30, 2025).

Xie, J., Tang, H., Huang, T., and Yu, F. R. (2019). A survey of blockchain for digital identity management. IEEE Commun. Surv. and Tutorials 21 (3), 2794–2833. doi:10.1109/COMST.2019.2897106

Zhang, Y., and Chen, L. (2025). Blockchain-based universal digital identity: opportunities and challenges. Financ. Innov. 11 (1).

Keywords: Universal Digital Identity, blockchain, self-sovereign identity, cross-border verification, digital finance, biometric authentication, decentralized identity, global identity

Citation: Akhison G (2025) Towards a Universal Digital Identity: a blockchain-based framework for borderless verification. Front. Blockchain 8:1688287. doi: 10.3389/fbloc.2025.1688287

Received: 18 August 2025; Accepted: 29 October 2025;

Published: 26 November 2025.

Edited by:

Carlo Campajola, University College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Ingrid Vasiliu Feltes, University of Miami, United StatesAbylay Satybaldy, Exponential Science, Cayman Islands

Copyright © 2025 Akhison. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Glad Akhison, Z2xhZGFraGlzb25AYm9sZHN3aXRjaC5uZw==

Glad Akhison

Glad Akhison