- 1Department of Computer Science, Sri Padmavati Mahila Visvavidyalayam, Tirupati, India

- 2Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Sri Padmavati Mahila Visvavidyalayam, Tirupati, India

- 3Data engineering and AI, Walmart Inc, Bentonville, AR, United States

- 4Department of Home Science, Sri Padmavati Mahila Visvavidyalayam, Tirupati, India

Today, people need personalized diet plan based on their health conditions. Latest technologies like Internet of Things (IoT), federated Learning, blockchain technology, and wearable devices help in gathering the information required to recommend personalized and nutritional diet plan and also maintain the data securely. As most of the existing system that recommend nutrition diet has many limitations like lack of privacy, less user engagement, usage of AI models that are not transparent and centralized data storage. Hence, Blockchain enabled Real-Time Personalized Health and Nutrition Management (BRPHM) framework is proposed in this paper. BRPHM is a multi-layer architecture which includes IoT data acquisition layer, Blockchain data management layer, federated AI processing layer, and a recommendation layer. BRPHM introduces a new parameter called Personalized Health Nutrition Index (PHNI) based on which recommendations are given to the user. A weighted health model based on environmental, nutrition, activity, physiological features determine PHNI value. The performance of the proposed framework is evaluated in terms of accuracy, recall, precision, F1-score, Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), latency, system availability, privacy score, and scalability score and is compared with ESCIFS, SEDCAM-2E and PNBDF. The results indicate that the proposed framework, BRPHM enhances the performance by 8%–22% in terms of classification metrics (accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score), 33%–53% in terms of forecasting metrics (MAE and RMSE), 42%–59% in terms of latency, 1.4%–2.8% in terms of system availability, 10%–27% in terms of privacy score and scalability score when compared to ESCIFS, SEDCAM-2E and PNBDF. The results also projects PHNI correlation score and Micro-action engagement score which indicates that the model is accurate and the system is effective.

1 Introduction

The great transformation of personalized wellness management is experiencing by the healthcare industries nowadays which is derived by the convergence of Internet of Things (IoT) devices, wearable sensors, artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, and data-driven nutritional science which together revolutionizing how the health and diet are monitored, analyzed, and managed for better health and proactive treatment (Hsu et al., 2024; Poonguzhali and Amarabalan, 2024; Lopez-Barreiro et al., 2023; Jamil et al., 2021a; Kumar et al., 2025).

Several chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disorders, and also obesity are the major among the leading causes of global mortality and morbidity (Bhardwaj and Datta, 2020; Bhat et al., 2021; Nayak et al., 2023). Various scientific evidences are confirming that the dietary habits and lifestyle choices play a vital role in both the prevention and management of these conditions. However, Dietary recommendations of the conventional methods are usually generic, static, and disconnected from real-time physiological data. This leads to a significant gap in between the clinical advice and the patient’s daily diet management. Addressing these kinds of gaps needs intelligent framework that can integrate the multi-modal health signals which are capable of dynamic adaptation to user contexts, and provides actionable diet recommendations in a secured and trustworthy manner.

The most recent advances in AI-based diet recommendation systems have shown a favorable result in capturing food intake patterns, recognizing nutritional deficiencies, and also generating personalized diet suggestions (Logapriya et al., 2023; Garcia et al., 2021; Sahoo et al., 2019; Toledo et al., 2019). Systems such as AI4FoodDB and Diet Engine have demonstrated how continuous monitoring is combined with deep learning will improve the individual nutrition tracking (Mantey et al., 2021; Theodore Armand et al., 2024). However, these solutions often remain non-transparent, and also vulnerable to privacy concerns due to the lack of robust mechanisms for secure data exchange and tamper-proof diet tracking.

A Transformative tool to address security and privacy concerns in healthcare and diet management systems has recently emerged with blockchain technology (Mantey et al., 2021; Jamil et al., 2021b; Zhang et al., 2022; Bosri et al., 2020). It has decentralized and immutable architecture which enables the secure storage, transparent data sharing, and also has fine-grained access control. Blockchain-based systems allow patients to own and control their dietary and health data by enabling trustworthy sharing with nutritionists, healthcare providers, and AI systems. Despite these advantages the existing blockchain healthcare systems either narrowly focuses on electronic health records (EHRs) (Poonguzhali and Amarabalan, 2024; Kumar et al., 2025) or disease-specific tracking systems (Bhardwaj and Datta, 2020; Mani et al., 2022) with a limited integration of personalized nutrition and real-time physiological feedback.

While AI algorithms can provide accurate health predictions as they often operated as “black-box” models by reducing user trust and interpretability. This limitations present can discourage adoption in sensitive domains like healthcare, current AI-powered diet recommenders rarely use long-term engagement tactics alone. Without incentives or user-centric motivators, compliance with the recommended dietary changes frequently falls over time.

To overcome these kinds of challenges, this paper proposes an extended framework building upon the Real-time Personalized Health Monitoring (RPHM) system. Which called as Blockchain-Enabled Real-Time Personalized Nutrition Framework (BRPHM) this is meant to integrate the IoT-enabled wearable devices, also blockchain for secure and auditable data management, along with federated and explainable AI for privacy-preserving and transparent predictions, and consists of a novel tokenized incentive mechanism in order to encourage user adherence to dietary plans.

The contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows.

1. Blockchain-Integrated Data Management: which is a permissioned blockchain layer which ensures secure, immutable, and auditable storage for the health and nutrition data, including Personalized Health Nutrition Index (PHNI) scores and micro-actions in order to overcome the privacy and trust issues in existing diet recommenders.

2. Federated and Explainable AI: where the AI engine employs federated learning to train the models across distributed user data without exposing any raw records leads to combined and explainable AI (XAI) modules that justifies each recommendation with nutritional and clinical evidence.

3. Nutrition-Token Incentive Model: In which a novel gamification strategy includes to make nutrition tokens for compliance with recommended diets and micro-actions. Tokens are recorded on blockchain and redeemable for health services thereby enhancing long-term engagement.

4. Dynamic PHNI-Diet Coupling: Which extends the RPHM’s PHNI score by integrating nutrient intake features (macro/micro nutrients, hydration, circadian rhythm of diet) in order to create a composite diet-health index for real-time recommendation generation.

The proposed framework advances in the state of the art in personalized nutrition and preventive healthcare by combining trustworthy blockchain infrastructure, privacy-preserving AI models, dynamic nutritional indices, and gamified incentives. The proposed BRPHM addresses parameters like accuracy, security, interpretability, and user engagement by making it suitable for large-scale deployment in real-world healthcare ecosystems in a simultaneous manner unlike the existing systems.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section II for reviews related work on blockchain-based healthcare and AI-driven diet recommender systems. Section III defined to detail the proposed BRPHM architecture and mathematical modeling. Section IV represents implementation strategies and experimental design. Section V meant for evaluations of the framework against existing benchmarks. Section VI defined to discuss about implications and future research directions, and finally section VII concludes the study.

2 Related work

In the past few years, the blockchain has increasingly been explored as a way to make healthcare data more secure, transparent, and trustworthy. For example, various researchers such as Mantey et al. (2021) and Mantey et al. (2023) have used blockchain to protect sensitive medical recommender systems by ensuring that diagnoses and treatment suggestions cannot be tampered with. Similarly, Lopez-Barreiro et al. (2023) and Lopez-Barreiro et al. (2024) have proposed blockchain platforms for holistic health management also extended them into gamification to encourage healthy habits. Other studies have looked at blockchain in more specific contexts: such as Jamil et al. (2021a) and Jamil et al. (2021b) have focused on IoT-enabled fitness frameworks and healthcare microservices while the other Hsu et al. (2024) and Poonguzhali and Amarabalan (2024) have applied blockchain to personal health records (PHR) and electronic health records (EHRs) with an emphasis on dietary guidance for chronic illnesses like diabetes.

Many recent works have been shifted towards the traceability and interoperability. Rafif et al. (2025) have demonstrated how blockchain could verify nutrition facts in the food industry, and Zhang et al. (2022) have designed a blockchain schema for managing chronic diets. Broader surveys and frameworks have mentioned in Kumar et al. (2025), Bosri et al. (2020) and Thakur et al. (2025) argues that combining of blockchain with AI could create a powerful, privacy-preserving healthcare solutions. At the same time, researchers are beginning to look ahead at quantum-resistant blockchain models (Jain et al., 2024; Das et al., 2024) which will be critical for protecting medical records against future cyber threats.

Despite of these advances most of the blockchain healthcare systems still stop short of real-time nutrition guidance. They focus only on securing data or sharing records but rarely connect directly to dynamic diet recommendations, explainable models, or any of the long-term engagement strategies.

Artificial intelligence has opened the door to make much smarter diet management. Vision-based systems like Diet Engine (Logapriya et al., 2023) and NUTRIVISION (Garcia et al., 2021) has capabilities to recognize foods through images and estimate their nutritional content on the spot. Other researchers have explored more knowledge-driven systems: for example, Garcia et al. (2021) had built a “Virtual Dietitian” using expert rules while the other Abeltino et al. (2025) highlighted about the importance of precision nutrition apps that are co-designed with professional input.

AI has also been applied to disease-specific nutrition. Bahirat et al. (2024) and Iwendi et al. (2020) have explored how the diet recommendations can be tailored to cure conditions like diabetes while the other Nayak et al. (2023) had built predictive models that combines disease risk with food suggestions. The balance between simplicity and complexity in user nutrition models where the systems have to be accurate but also easy for patients to understand and follow these are defined by Schäfer et al. (2017) and Toledo et al. (2019).

However, even with these advances, many AI-based recommenders are standalone apps. They do not usually integrate with continuous health data from wearables, and their “black-box” predictions make it hard for users or clinicians to trust the reasoning behind recommendations. Privacy is another weak point: very few systems guarantee secure, tamper-proof histories of diet logs.

A third line of research combines IoT, federated learning, and edge computing to make nutrition frameworks more sustainable and private. For example, Ahamed and Karthikeyan (2024) have proposed FLBlock which marries blockchain with federated learning so that the health and food supply data can be shared without exposing raw information. Mani et al. (2022) have worked on storing health data blocks directly inside electronic repositories, and Sahoo et al. (2019) have surveyed the wearable health monitoring systems that can run computations partly on the device (edge AI) to reduce latency. The authors in Yang et al. (2025) and Xu et al. (2024) presented the application of blockchain in finance related applications.

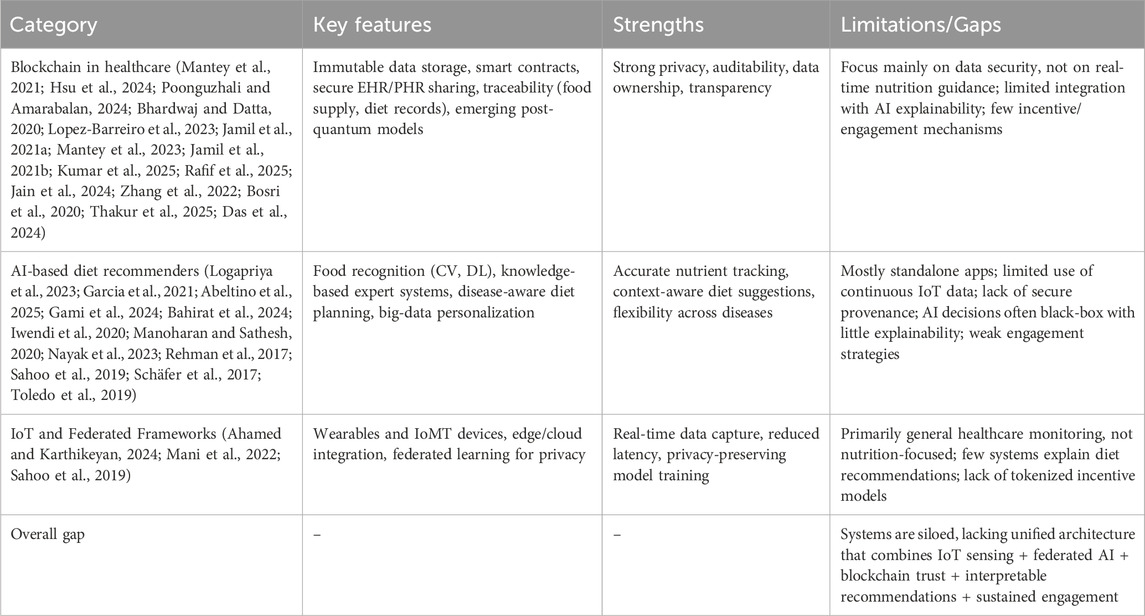

These approaches are promising, especially for handling large-scale, real-time data, but most of them are general healthcare platforms rather than nutrition-specific frameworks. They also tend to focus more on the infrastructure (edge computing, federated learning) than on explainability, user incentives, or micro-action diet guidance. Comparative Analysis of Existing Approaches in Personalized Nutrition & Healthcare is shown in Table 1.

2.1 Gaps in the literature

• First the existing systems are often siloed: blockchain papers emphasize security, AI papers focus on prediction, and IoT papers highlight infrastructure but they rarely come together into a single unified framework.

• Second various privacy and governance are inconsistently addressed. Most AI recommenders do not provide verifiable consent or audit trails, while blockchain systems typically do not record the actual model training or inference events tied to diet recommendations.

• Third there is a lack of explainability. Users and clinicians need to know why a diet recommendation is being made, yet most systems treat AI as a black box.

• Fourth user engagement is an afterthought. Very few studies explore how to motivate patients to follow diet advice consistently. For example, through rewards or gamification.

• Finally, only a handful of works even consider future-proof security such as quantum-resistant blockchain.

3 Blockchain enabled real-time personalized health and nutrition management (BRPHM) framework

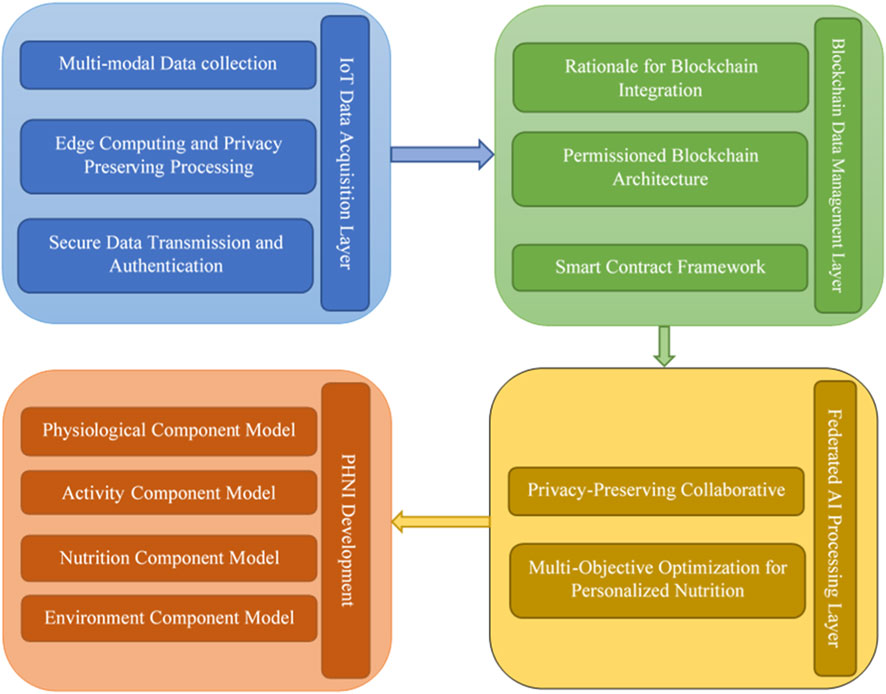

The multi-layered architecture of the Blockchain-Enabled Real-Time Personalized Nutrition Framework (BRPHM) has five layers they are IoT Data Acquisition Layer, Blockchain Data Management Layer, Federated AI Processing Layer as shown in Figure 1. Explainable Recommendation Layer, and Tokenized Incentive Layer. The four essential challenges in personalized nutrition systems are addressed by the proposed framework they are system scalability, data security and privacy, user engagement and compliance, trust and transparency. The sovereignty of the individual data is maintained by the distributed architecture of BRPHM. The basic principle of the system is monitoring the health of an individual continuously and generating various suitable recommendations. The real-time physiological signals, behavioral responses, environmental factors and dietary intake patterns of each user are used to dynamically compute and maintain Personalized Health Nutrition Index (PHNI) which is used to generate recommendations based on nutrition diet for better lifestyle patterns and health conditions.

3.1 IoT data acquisition layer

The IoT layer serves as the sensory foundation for the BRPHM framework by capturing comprehensive health and lifestyle data through several diversified sensor modalities. The data collection strategy consists of four primary categories of the information that provides a complete view of the user health status along with the contextual factors.

Physiological sensors are meant to monitor continuously several major health indicators like heart rate variability, blood glucose levels, blood pressure, body temperature, oxygen saturation, and also the sleep quality metrics.

These sensors will provide the foundational health data in order to understand the metabolic state and nutritional needs. To track physical movement patterns including step count, caloric expenditure, exercise intensity, activity duration, and sedentary behavior patterns of the users the activity sensors are used. The collected information based on activity levels is necessary and crucial for calculating energy balance and adjusting nutritional recommendations.

Environmental sensors are meant to monitor contextual factors which are going to influence the nutritional needs and food choices. They are air quality indices, ambient temperature, humidity levels, UV exposure, and location-based factors these helps in understanding the system and external factors that may directly affect the metabolism, hydration needs, and food safety considerations. For advanced food recognition technologies, smart utensils, and portion estimation devices to track actual food intakes, meal timings, eating patterns, and hydration levels of the users several dietary sensors are employed.

The BRPHM implements edge computing capabilities at the IoT device level in order to address the privacy concerns and to minimize the data transmission requirements. Preliminary the data processing which includes the data validation, noise reduction, feature extraction, and anomaly detection before transmitting processed information to the blockchain network is performed by each sensor device.

There are multiple purposes served by the edge processing approach in which the reduction in the amount of raw data which needs to be transmitted and stored on the blockchain, minimizes the potential privacy exposure by keeping sensitive raw measurements in local also enables real-time responsiveness for critical health alerts, and reduces network bandwidth requirements for all the large-scale deployments.

At the edge data validation process occurs to ensure that the sensor accuracy and detects the potential device malfunctions. To identify relevant patterns and trends from raw sensor data by creating compact representations that maintains the clinical relevance while reducing data volume, this process is done by the Feature extraction algorithms. Identification of unusual patterns that may indicate health emergencies or device failures by triggering appropriate alerts or data quality flags is done by the Anomaly detection mechanisms.

All data transmissions from IoT devices to blockchain networks will employ the end-to-end encryption using advanced cryptographic protocols. Each IoT device need to be equipped with unique cryptographic keys that enables the secure authentication and data integrity verification. The system implements a rotating key mechanism to prevent long-term key compromise and maintains secure key distribution protocols for new device enrollment.

Device authentication ensures that only authorized sensors can able to contribute data to a user’s health profile by preventing spoofing attacks and maintaining the data integrity. Timestamp verification and sequence numbering prevents replay attacks and ensures data freshness. Digital signatures on all transmitted data is to enable verification of data source and integrity throughout the processing pipeline.

3.2 Blockchain data management layer

The integration of blockchain technology in the BRPHM framework addresses fundamental challenges that effects the various existing personalized nutrition systems. Traditional centralized health data management systems are suffering from several critical vulnerabilities like single point of failures which can compromise entire user databases, lacking in the user control over personal health information, vulnerabilities to the data breaches and unauthorized access, difficulties in establishing trust between users and service providers, limited transparency provision in terms of how personal data is used for recommendations, and challenges in ensuring long-term data preservation and accessibility.

Blockchain technology provides several solutions to these challenges through its inherent characteristics of decentralization, immutability, transparency, and cryptographic security. In the context of personalized nutrition, the blockchain enables users to maintain absolute control over their health data while selectively giving access to healthcare providers, researchers, and AI systems. The distributed nature of blockchain eliminates multiple single point of failures and provides a possibility of creating a tamper-resistant record of all health-related transactions and data modifications.

The blockchain has immutable nature which ensures that once if health data is recorded it cannot be altered or deleted without making a permanent and verifiable health history. For the longitudinal health studies and establishing causal relationships between dietary interventions and health outcomes the same characteristic is valuable. The transparency of blockchain technology operations allows the users to verify how their data is being accessed and used in order to build trust in the system and enabling informed consent for data sharing.

The BRPHM framework employs a consortium blockchain model designed for healthcare applications in order to balance the benefits of decentralization along with the privacy and regulatory requirements of health data management system. The blockchain network consists of multiple node types, where each node is serving specific function within the ecosystem.

Patient nodes are created for representing individual users and to maintain personal health data profiles. These nodes have full control over their data and can grant or revoke all kind of access permissions to other network participants. Patient nodes have the possibility to participate in consensus mechanisms and can validate transactions related to their own data. Healthcare provider nodes will represent medical institutions, clinics, nutritionists, and other healthcare professionals who may need access of the patient data for clinical decision-making. These nodes must undergo verification and credentialing processes before being granted for the network access.

AI service nodes will perform computational tasks which includes federated learning, recommendation generation, and data analysis. These nodes have specialized permissions that allows them to access anonymized or aggregated data for model training while respecting all individual privacy preferences. Regulatory nodes will represent health authorities and compliance organizations that may need to audit the system operations while maintaining the patient privacy.

The consensus mechanism which employed in the BRPHM is a modified Proof of Authority (PoA) system that prioritizes healthcare domain expertise and regulatory compliance over computational power. Consensus participants are selected based on their healthcare credentials, data security practices, and compliance with health information privacy regulations.

The blockchain layer has implementation of the specialized smart contracts that performs automation in various aspects of health data management and access control. Encoding of the healthcare privacy regulations, consent management protocols, and data sharing agreements into executable code that automatically enforces compliance with the smart contracts.

To handle the secure storage and access control of individual health records the Health Data Management Contract is meant. This contract maintains records of encrypted health data, manages access permissions based on user defined policies, implements time-based access controls that automatically expire also tracks all data access events for audit purposes, and enforces the data minimization principles by ensuring that requesters have to receive only the minimum data necessary for their specific use case.

The Consent Management Contract automates the complex process of managing informed consent for the health data sharing. This contract records users consent preferences for different types of data sharing which automatically enforces consent expiration and renewal requirements also provides users with easy mechanisms to revoke consent, maintains detailed audit trails of all consent-related activities, and ensures that the data sharing immediately stops when consent is withdrawn.

The Nutrition Token Contract have to manage the issuance, distribution, and redemption of tokens that incentivize healthy behaviors and dietary compliance. This contract tracks the user compliances with recommended dietary interventions also automatically issues tokens for completed health actions, maintains token balances and transaction histories which enables the token redemption for health services or products, and prevents double-spending or fraudulent token claims.

3.3 Federated AI processing layer

Fundamental tension between personalization and privacy in health recommendations is addressed by the AI processing layer. Centralized data collection which also poses in significant privacy risks and regulatory challenges in healthcare domains is required by the traditional machine learning approaches. BRPHM will resolve this challenge through federated learning which enables collaborative model training without centralizing sensitive health data.

In the federated learning approach, each of the patient node maintains a local machine learning model that is trained exclusively on their personal health data. This ensures that sensitive information will never leave the individual’s control while still enabling the benefits of large-scale machine learning. The local models have to learn patterns which are specific to individual users, capturing personal preferences, metabolic responses, and health conditions.

Periodically, the local models share only their learned parameters or gradients with the federated learning coordinator rather than sharing raw data. The coordinator will aggregate these parameters to create a global model that captures population-level patterns and knowledge. The updated global model is then need to distribute back to the individual nodes where it is to be combined with local learning to create personalized recommendations.

Based on this approach provision of several advantages are there over traditional centralized learning. The first one is enhanced privacy protection as the raw health data never leaves individual devices, the second one is improved model robustness through exposure to diverse patient populations, third one is reduced communication overhead compared to raw data sharing, fourth one is compliance with health data privacy regulations, and fifth one is resilience to node failures or network disruptions.

Multi-objective optimization techniques have to be employed by the AI engine have in order to balance the complex and often competing requirements of the personalized nutrition recommendations. The traditional nutrition systems typically optimized only for single objectives such as caloric balance or specific nutrient targets but in the real-world nutrition decisions involving in multiple competing factors that must be simultaneously considered.

Balanced recommendations generation is the task of the optimization framework which considers four primary objectives that must be nutritional adequate which ensures that recommendations meet established dietary guidelines and prevents nutrient deficiencies while avoiding excessive intakes that may lead health risks. Disease risk minimization will be focusing on reducing the likelihood of diet-related chronic diseases based on the individual risk factors, genetic predispositions, and current health status.

User preference satisfaction will acknowledge that the dietary recommendations must be acceptable and enjoyable to users to ensure the long-term compliance. The system learns about the individual taste preferences, cultural dietary patterns, and food aversions to generate recommendations that users are likely to follow. Practical constraints which include budget limitations, food accessibility, cooking skills, and time availability are incorporated to ensure that recommendations are feasible for individual users.

The multi-objective optimization process generates a Pareto-optimal solutions that represents the best possible trade-offs in between competing objectives. System presents to the users with a set of alternative options that optimizes different aspects of their nutritional needs by allowing informed decision-making based on personal priorities and circumstances, instead of providing a single recommendation.

FedAvg aggregation strategy is used to implement federated learning. Local model is trained for 5 epochs by each client and then only the updated encrypted model is shared and after each communication cycle, the global aggregation is made. Information leakage is prevented by applying differential privacy, ε = 1.0 while updating the model.

3.4 Explainable recommendation layer

Component level explanations for dietary recommendations and PHNI are generated in this module. Thus, transparency is being provided by this module. Attribution scores for physiological, nutrition, activity and environmental features are computed. These scores help the clinicians and user to know the contribution of each factor towards recommendation. Moreover, recommendations are justified using nutritional constraints which are based on rules. This justification enhances the clinical interpretability and trust.

3.5 Tokenized incentive layer - personalized health nutrition index (PHNI) development

To incorporate the comprehensive nutritional and lifestyle factors which influences the health outcomes, the traditional Personalized Health Index is significantly enhanced in BRPHM. the overall health status which able to adapt changes in conditions and provides the foundation for personalized nutrition recommendations is achieved by PHNI score.

Incorporation of traditional vital signs and biomarkers while adding nutrition-specific indicators such as metabolic rate, glucose tolerance, lipid profiles, inflammatory markers, and micronutrient status in the physiological component of the PHNI score. This comprehensive physiological assessment will provide the medical foundation for nutrition recommendations of the system.

These factors tracking like physical exercise, daily activity patterns like sedentary behavior, sleep quality, and circadian rhythm regularity by the activity component significantly influence the nutritional needs and the effectiveness of dietary interventions by making them as the essential components of the health assessment.

Detailed analysis of the dietary patterns, nutrient intake adequacy, meal timing, hydration status, and dietary diversity are incorporated by the nutrition component. This component meant to learn about the individual metabolic responses to different foods and nutrients by enabling highly personalized recommendations.

Several external factors which influence the health and nutrition including air quality, climate conditions, seasonal variations and stress levels are considered by environmental component. For adaption of recommendations in the changing circumstances and environmental challenges these contextual elements will help.

The PHNI score is calculated through the dynamic weighting of these components is based on individual health goals, current health status, and risk factors. Machine learning algorithms meant for continuously adjusting the relative importance of different components because they learn from user responses and health outcomes by creating a truly personalized health assessment tool that evolves with changing health needs and circumstances.

Context awareness, real-time adaptability and nutrition specific parameters are lacking in the existing health indices. They are static in nature. These existing systems are not suitable for recommending personalized nutrition as they did not consider environmental factors, activity levels, hydration, time of meal, food intake, etc.

All these factors are integrated and considered for computation of PHNI. Hence, it is more suitable for providing nutritional recommendations. Also, PHNI is dynamic in nature as it adapts to the changes in the values of the features considered. This dynamic nature of PHNI made it more apt for personalized and real-time diet recommendation.

4 Mathematical model for personalized health nutrition index (PHNI) model

Four main components are involved in the calculation of PHNI as given in Equation 1. Weights are considered for each component. These weights are initialized with population average, updated using gradient descent approach and made adaptive over time.

Where,

Population-level average health statistics are used to initialize α1, α2, α3, α4. The feedback of the health outcome and the error predicted are considered by the gradient descent procedure is used to update these weights. The PHNI model is able to learn the importance of the various components considered as these weights are dynamically updated and hence it is able to perform the assessment of time-varying and personalized health-nutrition.

4.1 Physiological component model

Where,

Normalized value of each parameter is computed using Equation 3:

Where,

4.2 Activity component model

Where,

4.3 Nutrition component model

Where,

Where,

Where,

Where,

Where, G is the total number of food groups,

4.4 Environmental component model

Where,

Where,

Where,

Where,

5 Experimental setup and performance evaluation

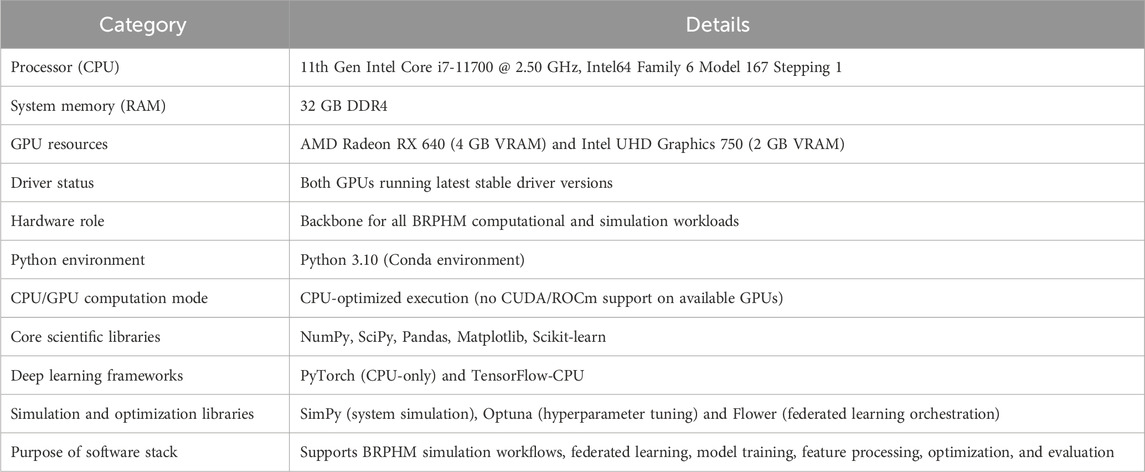

Hardware and software specifications used for implementing BRPHM framework is shown in Table 2.

5.1 Dataset strategy

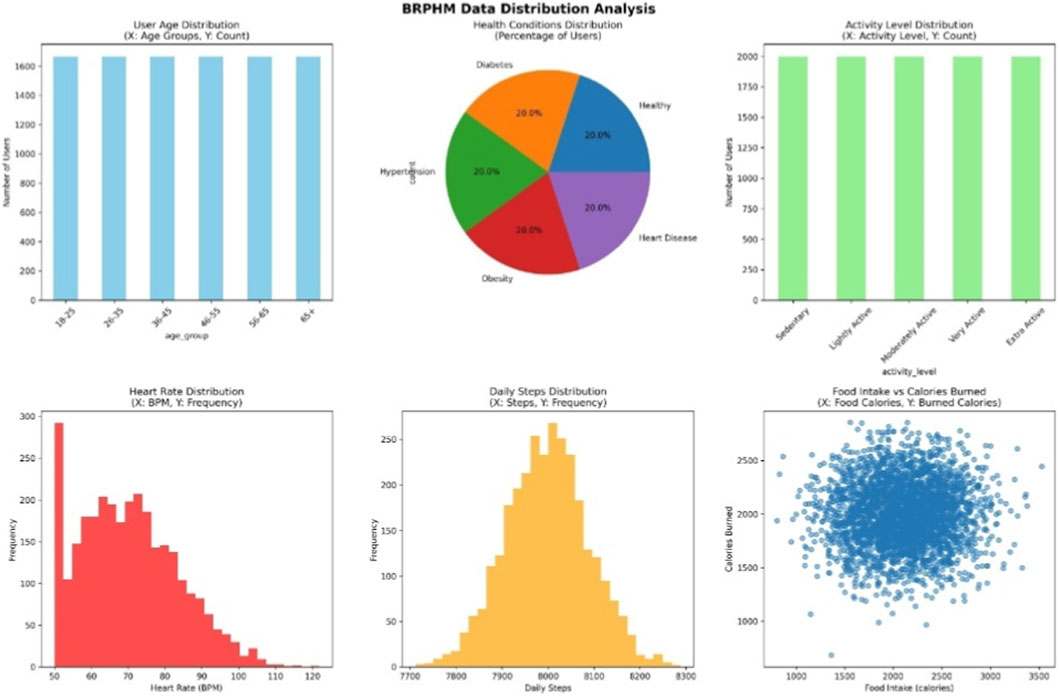

To validate the BRPHM framework, a large synthetic dataset is created that simulates real-world personalized nutrition situations while protecting privacy. The dataset strategy aimed to guarantee demographic diversity, ecological validity, and enough complexity to test the framework rigorously while providing accurate information for evaluation. The dataset distribution is shown in Figure 2.

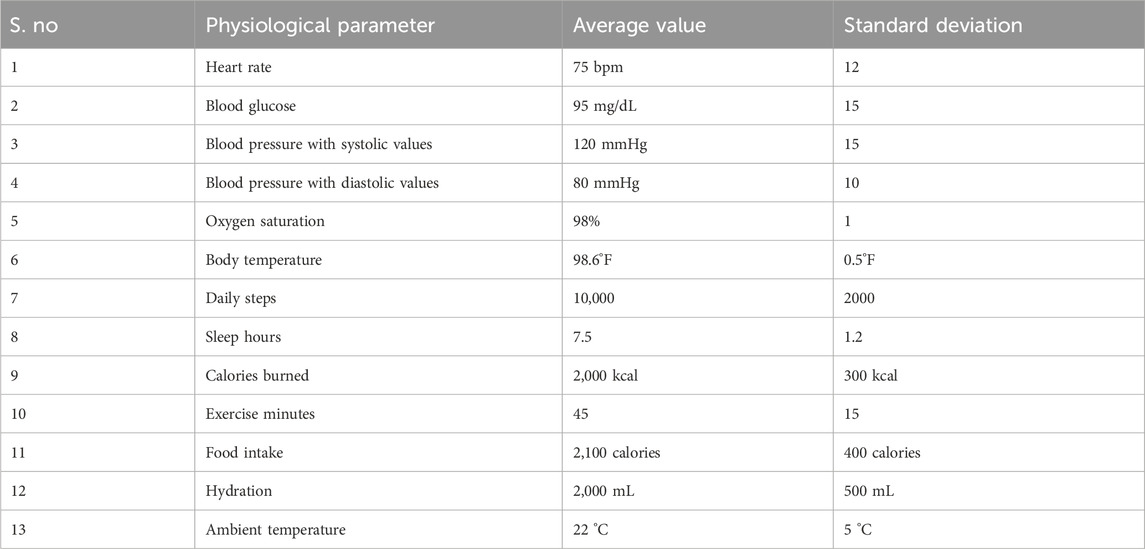

There are 10,000 diversified individual profiles in the dataset. Age distribution is considered to be between 18 and 65+ to represent with different stages of life. Distribution of gender is balanced. Five different categories of activity levels are considered in physical activity: sedentary, lightly active, moderately active, very active and extra active. Five categories in health condition considered with balanced representation are: healthy, heart disease, obesity, hypertension and diabetes. The dietary preference of the user is considered as Mediterranean, ketogenic, vegan, vegetarian and omnivore. BMI is considered to on average 25 with standard deviation of 5, initial PHNI is distributed between 0.3 and 0.9, data privacy level indicates the choice of users to share their data and it is considered to be high, low or medium. This distribution strategy was chosen to ensure unbiased evaluations across all demographic groups and stop the model from biasing towards majority groups which is a common issue in real-world healthcare systems. The physiological parameter values used for simulation are shown in Table 3.

The data is considered for 200 users over 30 days generating 6,000 time-series records of data for analysis.

Air quality index is considered to be uniformly distributed between 50 and 150.

Initially, diversified user profiles are constructed and then physiological, dietary, environment and activity related parameters are generated using probabilistic modeling and are based on clinical value distributions. Then, time-series archives are constructed for every user to gather everyday variations, PHNI values are initialized and updated periodically using the proposed model. This structured generation procedure guarantees preservation of privacy, stability, practicality and reproducibility.

5.2 Evaluation methodology

70% of the dataset is considered to be training set, 15% of the dataset is considered to be validation set and remaining 15% of the dataset is considered to be as the testing set also the simulation is run for 50 epochs to guarantee the reliable and generalizable results.

This is indicating that the number of users considered in training set are 7,000 with 4,200 time-series records. Where the number of users considered in validation set are 1,500 with 900 time-series records and the number of users considered in testing set are 1,500 with 900 time-series records. For the first 21 days of data is considered for training and the last 9 days of data is considered for testing purpose.

5.3 Performance evaluation and results

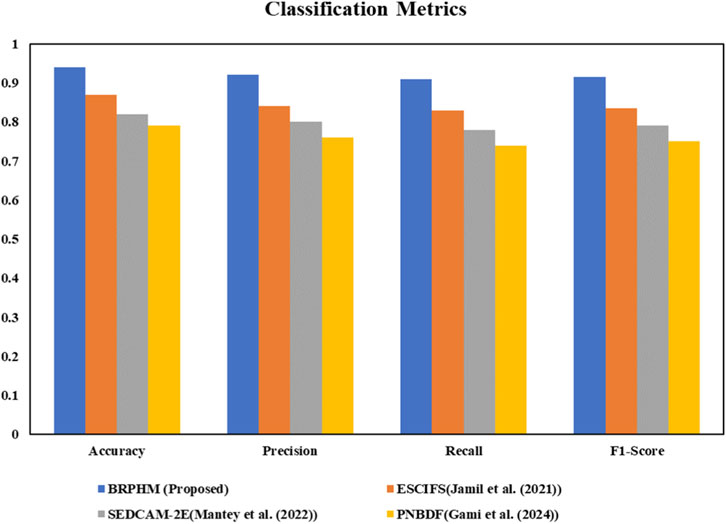

The performance of the proposed framework, BRPHM is compared with ESCIFS, SEDCAM-2E, PNBDF in terms of classification metrics (Accuracy, Precision, Recall and F1-Score) and is shown in Figure 3. BRPHM achieved 94% accuracy which is 8.05% improvement over ESCIFS, 14.63% enhancement over SEDCAM-2E and 18.99% increase on PNBDF. Federated learning architecture used in training diversified data and various privacy procedures used in securing the data made the proposed BRPHM framework perform well in terms of accuracy. The global model is balanced as it is getting trained with the federated approach using 10,000 different users which can include wide and diversified data. As the PHNI depends on environmental factors, nutrition and activity besides the heart rate and temperature, the complete details of the health related to an individual is clearer because of which the accuracy of BRPHM is enhanced whereas only limited physiological parameters are used by the other systems.

Figure 3. Comparison of BRPHM with ESCIFS, SEDCAM-2E, and PNBDF in terms of classification metrics (Accuracy, Precision, Recall and F1-Score).

BRPHM exhibits 92% precision whereas ESCIFS gives 84%, SEDCAM-2E projects 80%, and PNBDF provides 76% precision which demonstrates that the BRPHM outperforms when compared to the legacy systems. This shows that the proposed BRPHM framework avoids false positive classifications which might create unwanted tension in the users indicating that their health is at risk even though it is not actually. This parameter is very important to gain the trust of the users otherwise the system would get rejected by the users. i.e., users might not use it as it is giving false information repeatedly. BRPHM exhibits high precision as it adjusts the disease risk models carefully. The well-balanced training data helps the framework to learn how every nutrient affects each disease. To avoid overfitting problem, regularization is performed in the BRPHM. The use of blockchain guarantees that the data is reliable and clean which helps in avoiding the BRPHM learn from mistakes.

BRPHM achieved 91% Recall which is 9.64% improvement over ESCIFS, 16.67% enhancement over SEDCAM-2E and 22.97% increase on PNBDF. The enhancement in recall indicates that BRPHM is able correctly identify the risk factor of most of the people which helps in preventing chronic disease where early detection can increase the possibility of curing the disease and save the life of people. Consideration of air quality index while computing PHNI value also affects the recall performance. The features that are focused vary from individual to individual based on their health status in BRPHM. i.e., the weights of the features are different whereas it is fixed in other systems which might miss patterns that are specific to the conditions.

BRPHM achieved 91.5% F1-score which is 9.58% improvement over ESCIFS, 15.82% enhancement over SEDCAM-2E and 22% increase on PNBDF. F1-score is defined as the harmonic mean of precision and recall. Good performance in terms of recall indicate the BRPHM is able to avoid false positives and false negatives and this is achieved using multi-objective optimization.

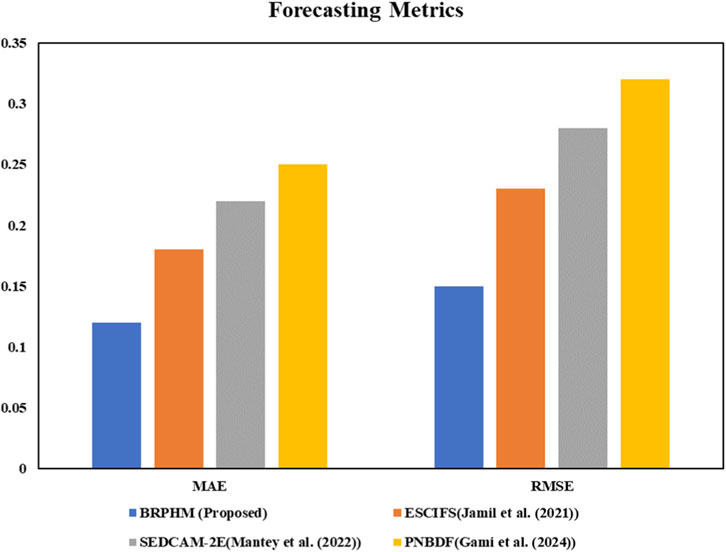

The performance of BRPHM in terms of forecasting metrics (Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)) is evaluated and compared with ESCIFS, SEDCAM-2E, and PNBDF and the results are shown in Figure 4. The enhancement in the performance of BRPHM indicate that the nutrition requirement and the health status of an individual is predicted appropriately by BRPHM. The enhancement of MAE by BRPHM when compared with ESCIFS, SEDCAM-2E, and PNBDF is 33.3%, 45.45% and 52% respectively. The low MAE comes from BRPHM’s use of recurrent neural network layers in its federated model architecture. This system models how today’s nutrition affects tomorrow’s health through metabolic carry-over effects. Competing frameworks usually rely on static models that treat each time point independently. They miss the important time-based dynamics of nutrition’s delayed effects on health signs. BRPHM’s improved PHNI calculation includes meal timing scores that capture chronobiological patterns. It determines that the same metabolic responses are produced by the same meals based on the time of the day. The time at which exercise is being done affects the rate of metabolism and how the nutrients are used throughout the rest of the day determines the circadian weighting of the activity component. The proposed framework, BRPHM learns how the choice of food of an individual affect their health over time using these features that are based on the time. BRPHM learns the true relation between cause and effect, i.e., what an individual is taking as food and how it is affecting their body. Hence, the accuracy of the predictions is enhanced and helps in recommending changes in the lifestyle or new diet.

Figure 4. Comparison of BRPHM with ESCIFS, SEDCAM-2E, and PNBDF in terms of forecasting metrics (MAE and RMSE).

The performance of BRPHM in terms of Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) is enhanced by 34.8%, 46.4%, and 53.1% when compared to ESCIFS, SEDCAM-2E and PNBDF respectively and the results are projected in Figure 4. This indicates that BRPHM will be able to handle errors in the predictions effectively. Better RMSE indicates the prediction is good which leads to correct dietary recommendations. This is important in the healthcare field as the incorrect dietary recommendations might worsen the health of an individual. Better RMSE is achieved by BRPHM because of federated architecture. Here, 100 local models are trained on different users and the predictions from these local models are integrated efficiently by the global model. This mechanism helps in minimizing the variance in the predictions made by local models. As the BRPHM prediction is good, the optimization algorithm can boldly provide strong recommendations to improve the health of an individual. If the RMSE is high, the optimization algorithm should be more effective and play its role efficiently by giving only limited recommendations as the risk cannot be taken with the health of the user. Usage of blockchain also helps in reducing RMSE as the prediction depends on the past data in the case of temporal models. Here, blockchain helps in securing the data and keeping the data safe without getting modified or tampered. Dietary recommendations are always dependent on the past and present health records. In this way, the federated architecture and the blockchain integration in BRPHM helps in reducing RMSE.

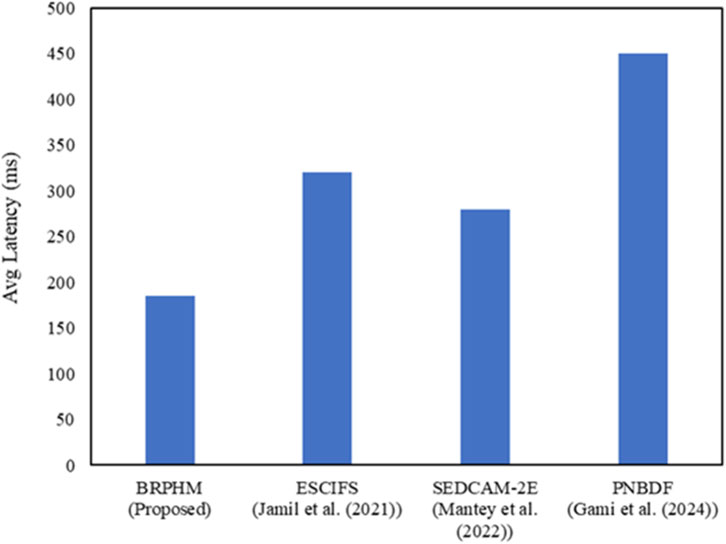

The performance of the proposed framework, BRPHM is evaluated in terms of average latency and is compared to the performance of ESCIFS, SEDCAM-2E, and PNBDF. The results are projected in Figure 5. The performance of BRPHM is improved by 42%, 34%, and 59% when compared to ESCIFS, SEDCAM-2E and PNBDF respectively. The improvement in latency makes the recommendations faster as soon as physiological changes occur. The reason for better performance in terms of latency is due to edge computing architecture as the local devices processes the IoT sensor data and transmits only processed features to the cloud which helps in generating the recommendation. Here, the noise is eliminated using Kalman filtering, quality of the data is eliminated anomalies and extracted only useful features. Hence, the data to be transmitted to the cloud will be reduced by 70% approximately due to edge computing architecture. Thereby, latency is reduced when compared to the legacy systems, ESCIFS and PNBDF which transmit the raw data directly to the cloud. SEDCAM-2E uses edge computing but feature extraction is not implemented. Hence, BRPHM outperforms SEDCAM-2E also. The Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT) used by blockchain consensus mechanism helps to create the blocks in 3s and handle 1,000 transactions per second which makes BRPHM as well as recommendations faster. As public Ethereum is used by PNBDF, it experiences low throughput and 13s block time which increases the latency. As the federated learning architecture enables the BRPHM to run local models on user devices itself, interpret faster and generate the recommendations instantaneously. This helps BRPHM to provide results faster when compared to the legacy systems.

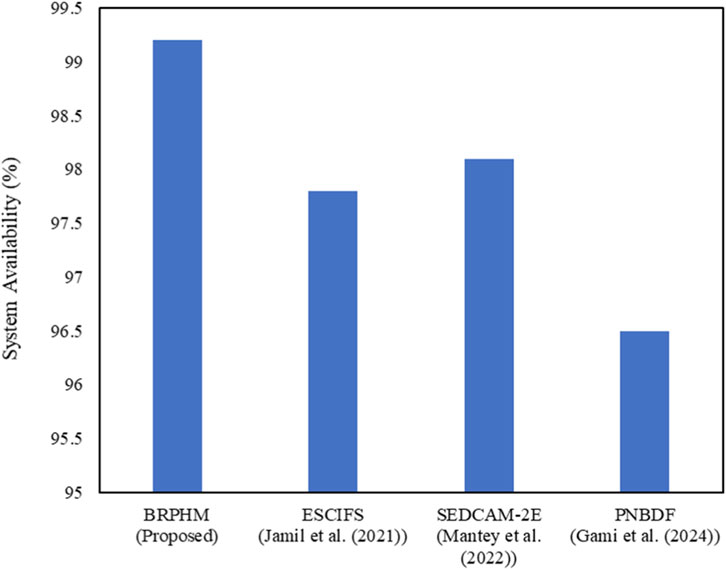

The performance of the proposed framework, BRPHM is evaluated in terms of system availability and is compared to the performance of ESCIFS, SEDCAM-2E, and PNBDF. The results are projected in Figure 6. It can be observed that BRPHM outperforms ESCIFS, SEDCAM-2E, and PNBDF. As the proposed framework deployed distributed architecture, it can function continuously even when any node is failed. At the same time, all the nodes need not function in the case of federated learning and 3 Byzantine failures for every 10 nodes can be tolerated because blockchain consensus mechanism. Hence, the system availability is high in the case of BRPHM. If the centralized systems are deployed, the system availability is decreased as it is not available upon failure. Even 1.4%–2.8% enhancement in system availability indicates that 120 to 240 more hours can be monitored and can avoid missing important health measures.

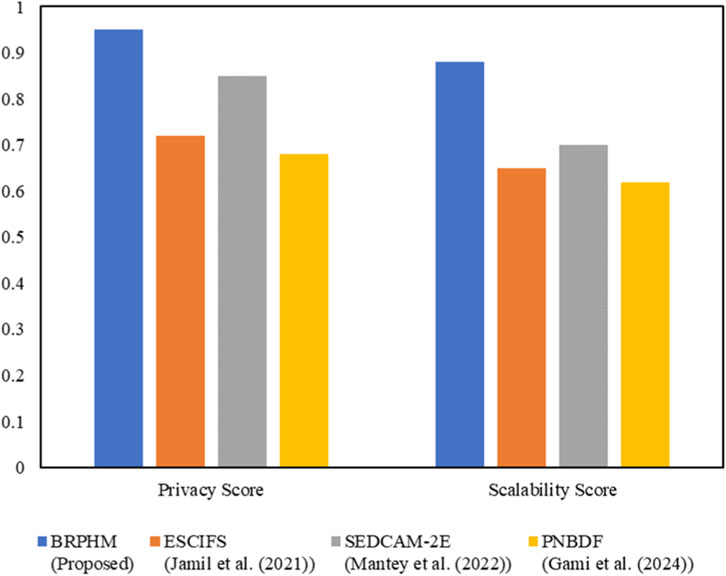

BRPHM has notable advantages in protecting sensitive health information while keeping system performance high as user numbers increase is shown by the comparison of privacy and scalability. This addresses two key obstacles to adopting personalized nutrition systems.

BRPHM has a privacy score of 0.95 which is significantly higher than ESCIFS at 0.72, SEDCAM-2E at 0.85, and PNBDF at 0.68 as shown in Figure 7. These scores represent an improvement of 10–27 percentage points in privacy protection and also this score measures how hard it is to re-identify the users from data breaches or inference attacks. It is calculated as one minus the chance that someone with additional information could link anonymized health records to individuals. BRPHM achieves its strong privacy through several mechanisms that works together as its federated learning structure ensures that raw health data stays on user devices. Only encrypted model parameters are sent during training which avoids creating centralized databases. These databases are prime targets for data breaches in the centralized frameworks like ESCIFS and PNBDF.

Figure 7. Comparison of BRPHM with ESCIFS, SEDCAM-2E, and PNBDF in terms of privacy score and scalability score.

Differential privacy adds noise with epsilon will set to 1.0 this provides strong privacy guarantees. It ensures that model parameters and aggregate statistics reveal almost no details about individual contributors even in the worst-case scenarios. The k-anonymity transformation with k set to 5 makes sure each record looks like at least four others based on identifiers like age, gender, and location. This prevents re-identification even when anonymized data is mixed with external datasets such as social media profiles or public records.

The blockchain framework adds to privacy through attribute-based encryption which controls access in a detailed way using cryptographic protocols as this is better than relying on application-level security which can be bypassed. Smart contracts create consent management policies in code that cannot be changed by database administrators or compromised by privilege escalation. Audit logging on the blockchain provides a permanent and tamper-proof record of all data access events. This helps detect unauthorized access and provides accountability which can deter insiders who might misuse their access to look at celebrity health records or sell data to insurance companies. In contrast, other frameworks like SEDCAM-2E use centralized access control, which can be overridden by administrators, and PNBDF’s public blockchain approach can actually lower privacy by exposing transaction patterns.

The privacy benefits lead to more users wanting to share their health data. Studies show that users are three to four times more likely to agree to detailed health monitoring when they receive strong privacy guarantees, like those offered by BRPHM. This encourages more data sharing, leading to better models, more accurate recommendations, and higher user satisfaction. In turn, this increases further data sharing, which explains the superior engagement metrics for BRPHM. Competing systems that lack credible privacy assurances face user distrust. This limits data collection to just the legally required minimum, hurting model quality and trapping them in a cycle of poor recommendations and user drop-off.

BRPHM’s scalability score of 0.88 outstrips ESCIFS at 0.65, SEDCAM-2E at 0.70, and PNBDF at 0.62 as shown in Figure 7. These scores indicate improvements of 18–26 percentage points in the system’s performance as user populations has grown from thousands to millions. This score reflects how system latency, accuracy, and availability decline as load increases. It is calculated through systematic testing with user groups of the active users ranging from 1,000 to 100,000. BRPHM’s superior scalability comes from design choices made explicitly for large-scale use. The federated learning approach spreads the computing workload across user devices while avoiding the bottlenecks found in centralized servers. It achieves almost linear scaling it is meaning that adding users also adds computing resources. In contrast, centralized frameworks must heavily invest in rapidly increasing server infrastructure as their user bases grow as this often incurs costs that outpace revenue in typical freemium models where most users do not pay.

The blockchain framework supports scalability through horizontal partitioning where this distributes transaction loads across multiple channels by avoiding bottlenecks in a single ledger. It handles about 1,000 transactions per second while supporting 10,000 users each generating 100 daily health updates. The Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance consensus mechanism provides much higher throughput than proof-of-work or proof-of-stake methods used by other blockchain systems. The voting-based consensus among approved validators wraps up quickly unlike the public blockchains which can take minutes or hours. The smart contracts are designed for efficient execution by ensuring that operations complete quickly which keeps costs down as transaction volumes rise.

The edge computing structure also boosts scalability as it moves about 70% of data processing onto local devices which cuts down on the need for cloud resources and reduces network bandwidth use. Competing frameworks need costly GPU server farms for deep learning tasks for millions of users. In contrast, BRPHM conducts these tasks on user’s smartphones and wearables by turning capital expenses into operating costs spread over the user base. This approach allows BRPHM to reach profitability with far fewer users than competing centralized systems by making the personalized nutrition service more economically viable.

The combined privacy and scalability improvements tackle two essential success factors for personalized health systems. BRPHM’s distributed architecture not only offers better machine learning performance but also provides the operational traits needed for real-world deployment at large scales, all while maintaining user trust with strong privacy protections.

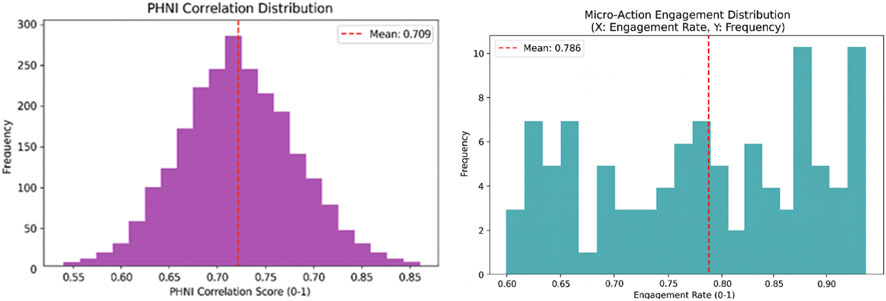

The innovation metrics visualization here shows two complementary distribution analyses that highlight BRPHM’s effectiveness in capturing meaningful health relationships and encouraging users to change their behavior over time. These are the ultimate goals of the personalized nutrition systems which go beyond just technical performance metrics. PHNI correlation score and Micro-Action Engagement Distribution is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Performance of BRPHM in terms of PHNI correlation score and micro-action engagement distribution.

The PHNI correlation distribution reveals a mean correlation score of 0.709 in between calculated Personalized Health Nutrition Index (PHNI) values and actual health outcomes which are measured through clinical biomarkers and physician assessments. The distribution is approximately normal and centred near 0.71 with a standard deviation of about 0.05. This indicates that for most users BRPHM’s real-time PHNI calculation is accurately tracking true health status changes over a 30-day evaluation period. This strong correlation validates the design choices of the improved PHNI formula especially the inclusion of nutritional and environmental components in addition to the traditional vital signs. It also confirms that the dynamic weight adaptation mechanism personalizes the PHNI calculation to fit into each individual’s unique physiology and health conditions. The tail of the distribution extends above 0.80 for about 15% of users which suggesting that for a significant minority where the PHNI correlation exceeds 0.80 it is nearing the reliability of clinical measurements. These high-correlation users usually have consistent lifestyle patterns that creates a clear cause-and-effect relationships between dietary changes and health outcomes. This provides valuable training data for the federated learning models which use these patterns to help other users benefit from the global model.

The strong PHNI correlation is allowing BRPHM’s recommendation engine to generate interventions with high confidence in their predicted health impacts of the user. The objective for minimizing disease risk relies on accurately forecasting how proposed dietary changes will affect the future PHNI values. If the PHNI does not track actual health well then, the optimization process becomes largely random which it may inadvertently recommend harmful interventions. This explains why competing frameworks produce lower quality recommendations but BRPHM’s mean correlation of 0.709 significantly exceeds the typical correlations of 0.5–0.6 which is found in traditional health risk assessment tool as it relies solely on demographics and self-reported health status. This reinforces the value of continuous IoT monitoring and thorough feature engineering that includes environmental and behavioral factors. There the improvement in correlation comes directly from BRPHM’s innovations by including edge processing that captures short-term physiological responses that cloud-only systems miss due to delays, federated learning that takes advantage of population diversity to identify general health patterns, and blockchain data integrity that ensures PHNI calculations use accurate historical data without issues that could distort true relationships.

The micro-action engagement distribution shows a mean engagement rate of 0.786 where it indicates that users successfully complete about 78.6% of the small and incremental behavioral recommendations generated by BRPHM’s micro-action framework. The distribution is approximately uniform and it is spanning from 0.60 to 0.95 revealing considerable individual variation in engagement. About 20% of users achieve over 90% completion rates while around 10% struggle with rates below 65%. This pattern suggests that BRPHM’s recommendation engine effectively adjusts the difficulty of recommendations to suit most users while avoiding overwhelming suggestions that could lead to learned helplessness, as well as trivial ones that do not promote meaningful behavior change. The high mean engagement rate of 78.6% far surpasses the typical adherence rates of 30%–50% found in traditional dietary counseling which often requires simultaneous changes across multiple behaviors. This supports BRPHM’s strategy of breaking large health goals into small and manageable steps that build up over time.

The engagement benefits come from BRPHM’s multi-objective optimization which explicitly models practical feasibility. This penalizes recommendations that demand excessive cost, time, or cooking skills that users may be lacking. Competing frameworks optimizes only for nutritional adequacy and disease risk reduction, generating theoretically ideal recommendations that may not be feasible for many other users. This leads to failures that discourage further engagement but BRPHM’s handling of constraints ensures that all recommendations respect user-specified practical limits. Meanwhile, the Pareto optimization presents multiple alternative options by allowing users to choose recommendations based on their current situations and preferences. This increases the sense of autonomy which psychological research shows is crucial for sustaining behavior change. The preference learning feature uses collaborative filtering in order to identify foods users are likely to enjoy based on similarities to other users with comparable tastes. This ensures that the recommendations are both nutritionally sound and enjoyable also addressing a major reason why dietary interventions often fail.

The blockchain-based token reward system helps in maintaining user engagement by offering tangible incentives for completing recommended micro-actions as users can redeem tokens for healthy foods, fitness services, or lower insurance premiums. Smart contracts automatically issue tokens when the IoT sensors verify completion by providing immediate reinforcement that behavioral psychology studies show to be more effective than delayed rewards. The secure audit trail prevents token fraud while clear issuance rules are built for user trust in the fairness of the reward system by boosting motivation to earn tokens. Competing frameworks usually lack incentive systems or implement them through centralized point systems that are open to manipulation by administrators or hackers by reducing user confidence in the integrity of the reward programs.

Overall, the innovation metrics show that how the BRPHM meets the key objectives of personalized nutrition systems as it accurately tracks health status through validated indices and effectively motivates sustained behavior changes with engaging with feasible recommendations. These results go beyond traditional performance measures and reflect real-world impacts on user health behaviors and clinical outcomes. This supports BRPHM’s comprehensive approach which combines IoT sensing, federated AI, blockchain data management, multi-objective optimization, and behavioral science into a single framework that outperforms competing systems across all evaluated areas.

There are many deep-seated reasons for the better performance of BRPHM. (1) PHNI considers health, nutritional, activity levels, environmental features which help in providing more useful and distinct representations of features when compared to existing indices. (2) Noise and bias are reduced; accuracy and generalization are enhanced using federated learning as diversified user patterns are used in learning process. (3) Reliability of decision is improved and latency is decreased using edge processing and explainable AI. (4) Reliable and high-quality inputs are guaranteed by blockchain based consent management and data integrity. Finally, the choice of these algorithms and architecture together led to the constant enhancements in scalability, privacy, latency, forecasting and accuracy.

5.4 Practical applications of BRPHM

Digital nutrition and smart healthcare are the platforms where the proposed framework, BRPHM can be deployed practically. IoT and wearable data can be used to provide trustworthy, personalized and real-time recommendations of diet. It is more appropriate where dynamic nutrition guidance and continuous monitoring are required. For example, in the case of wellness programs and management of chronic diseases (hypertension, obesity, diabetes, etc.). The BRPHM can also be deployed in the case of telehealth servicers, fitness applications, hospital remote monitoring systems.

6 Conclusion

A reliable and powerful personalized nutrition recommendation framework is proposed by integrating IoT, federated learning and blockchain technology. Federated learning is used to run local models on the devices itself to reduce latency and multi-objective optimization module helps in generating recommendations of personalized diet. Explainable AI module helps in enhancing the transparency. Blockchain is used to provide privacy and enhance security to the user information. Physiological, activity, nutrition, and environmental component values are used to estimate the value of PHNI and thereby recommending the nutritional diet to the user. The results indicate the proposed framework, BRPHM outperforms in terms of classification metrics, forecasting metrics, latency, system availability, privacy and scalability score when compared to ESCIFS, SEDCAM-2E and PNBDF. BRPHM is a scalable, transparent and secure framework which recommends personalized and nutrition diet to the users. Integration of large language models could generate context-aware, conversational recommendation, infer PHNI and improve explainability.

There are three limitations related to BRPHM. Usage of synthetic dataset as it might not observe complete real-time physiological and behavioral variations. Also, socioeconomic and genetic components are not incorporated in PHNI computation which might affect long term diet. As federated learning and blockchain are integrated in BRPHM, computational overhead might impose challenges in the case of low-resource devices.

As a part of future work, real-time clinical dataset will be used to evaluate the performance of BRPHM. Mental health and genomic components also will be incorporated in the computation of PHNI. The BRPHM will be optimized to overcome the overhead due to federated learning and blockchain which help to deploy BRPHM in lightweight devices. It can also be extended to integrate large language models to evaluate user adherence and long-term health outcomes.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

PV: Funding acquisition, Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Resources, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Supervision. VS: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Validation, Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Data curation. PP: Software, Writing – review and editing, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Data curation. MA: Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Validation, Visualization. PJ: Writing – original draft, Software, Validation, Visualization, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support received under the PM-USHA grant no. R.O.C.No.SPMVV/UGC/UGC/F1/PM-USHA/2025 dated: 08-04-2025 for facilitating the publication of this research.

Conflict of interest

Author PP was employed by Data engineering and AI, Walmart Inc.

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abeltino, A., Riente, A., Bianchetti, G., Serantoni, C., De Spirito, M., Capezzone, S., et al. (2025). Digital applications for diet monitoring, planning, and precision nutrition for citizens and professionals: a state of the art. Nutr. Rev. 83 (2), e574–e601. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuae035

Ahamed, N. N., and Karthikeyan, P. (2024). FLBlock: a sustainable food supply chain approach through federated learning and blockchain. Procedia Comput. Sci. 235, 3065–3074. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2024.04.290

Bahirat, A. D., Dixit, B., and Dixit, A. (2024). Diet consultation using artificial intelligence. Food Sci. Technol. 12, 24–47. doi:10.13189/fst.2024.120103

Bhardwaj, R., and Datta, D. (2020). “Development of a recommender system HealthMudra using blockchain for prevention of diabetes,” in Recommender system with machine learning and artificial intelligence: practical tools and applications in medical, agricultural and other industries, 313–327.

Bhat, S. S., and Ansari, G. A. (2021). “Predictions of diabetes and diet recommendation system for diabetic patients using machine learning techniques,” in Proc. 2021 2nd international conference for emerging technology (INCET), 1–5.

Bosri, R., Rahman, M. S., Bhuiyan, M. Z. A., and Al Omar, A. (2020). Integrating blockchain with artificial intelligence for privacy-preserving recommender systems. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 8 (2), 1009–1018. doi:10.1109/tnse.2020.3031179

Das, S., Mondal, S., Golder, S. S., Sutradhar, S., Bose, R., and Mondal, H. (2024). “Quantum-resistant security for healthcare data: integrating lamport n-Times signatures scheme with blockchain technology,” in Proc. 2024 international conference on artificial intelligence and quantum computation-based sensor application (ICAIQSA), 1–8.

Gami, S. J., Dhamodharan, B., Dutta, P. K., Gupta, V., and Whig, P. (2024). “Data science for personalized nutrition harnessing big data for tailored dietary recommendations,” in Nutrition controversies and advances in autoimmune disease (United States: IGI Global), 606–630.

Garcia, M. B., Mangaba, J. B., and Tanchoco, C. C. (2021). “Virtual dietitian: a nutrition knowledge-based system using forward chaining algorithm,” in Proc. 2021 international conference on innovation and intelligence for informatics, computing, and technologies (3ICT), 309–314.

Hsu, C. Y., Chao, J. C. J., Lee, H. A., Liu, C. Y., and Huang, S. W. (2024). Blockchain-based personal health record management and dietary recommendation system. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 8, 102841. doi:10.1016/j.cdnut.2024.102841

Iwendi, C., Khan, S., Anajemba, J. H., Bashir, A. K., and Noor, F. (2020). Realizing an efficient IoMT-assisted patient diet recommendation system through machine learning model. IEEE Access 8 (1), 28462–28474. doi:10.1109/access.2020.2968537

Jain, K., Singh, M., Gupta, H., and Bhat, A. (2024). “Quantum resistant blockchain-based architecture for secure medical data sharing,” in Proc. 2024 3rd international conference on applied artificial intelligence and computing (ICAAIC), 1400–1407.

Jamil, F., Kahng, H. K., Kim, S., and Kim, D. H. (2021a). Towards secure fitness framework based on IoT-enabled blockchain network integrated with machine learning algorithms. Sensors 21 (5), 1640. doi:10.3390/s21051640

Jamil, F., Qayyum, F., Alhelaly, S., Javed, F., and Muthanna, A. (2021b). Intelligent microservice based on blockchain for healthcare applications. Comput. Mater. Continua 69 (2), 2513–2530. doi:10.32604/cmc.2021.018809

Kumar, A., Sharma, N., Cengiz, K., and Singh, S. P. (2025). “Revolutionizing healthcare through blockchain and AI: a secure data sharing framework,” in Healthcare recommender systems: techniques and recent developments (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland), 1–28.

Logapriya, E., and Surendran, R. (2023). “Knowledge based health nutrition recommendations for during menstrual cycle,” in Proc. 2023 international conference on self sustainable artificial intelligence systems (ICSSAS), 639–646.

Lopez-Barreiro, J., Alvarez-Sabucedo, L., Garcia-Soidan, J. L., and Santos-Gago, J. M. (2023). Creation of a holistic platform for health boosting using a blockchain-based approach: development study. Interact. J. Med. Res. 12 (1), e44135. doi:10.2196/44135

Lopez-Barreiro, J., Alvarez-Sabucedo, L., Garcia-Soidan, J. L., and Santos-Gago, J. M. (2024). Towards a blockchain hybrid platform for gamification of healthy habits: implementation and usability validation. Appl. Syst. Innov. 7 (4), 60. doi:10.3390/asi7040060

Mani, V., Kavitha, C., Band, S. S., Mosavi, A., Hollins, P., and Palanisamy, S. (2022). A recommendation system based on AI for storing block data in the electronic health repository. Front. Public Health 9, 831404. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.831404

Manoharan, D. S., and Sathesh, A. (2020). Patient diet recommendation system using K clique and deep learning classifiers. J. Artif. Intell. Capsule Netw. 2 (2), 121–130. doi:10.36548/jaicn.2020.2.005

Mantey, E. A., Zhou, C., Anajemba, J. H., Okpalaoguchi, I. M., and Chiadika, O. D. M. (2021). Blockchain-secured recommender system for special need patients using deep learning. Front. Public Health 9, 737269. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.737269

Mantey, E. A., Zhou, C., Mani, V., Arthur, J. K., and Ibeke, E. (2023). Maintaining privacy for a recommender system diagnosis using blockchain and deep learning. Human-Centric Comput. Inf. Sci. 13 (47), 510. doi:10.22967/HCIS.2023.13.047

Nayak, S. K., Garanayak, M., Swain, S. K., Panda, S. K., and Godavarthi, D. (2023). An intelligent disease prediction and drug recommendation prototype by using multiple approaches of machine learning algorithms. IEEE Access 11 (1), 99304–99318. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3314332

Poonguzhali, N., and Amarabalan, N. (2024). “EHR based prediction and diet recommender for diabetes using blockchain,” in Proc. 2024 third international conference on smart technologies and systems for next generation computing (ICSTSN), 1–6.

Rafif, M. N., Alamsyah, A., and Triono, S. P. H. (2025). “Blockchain-driven nutrition facts traceability in Indonesia: enhancing transparency and trust in the food industry,” in Proc. 2025 international conference on computer sciences, engineering, and technology innovation (ICoCSETI), 774–779.

Rehman, F., Khalid, O., Bilal, K., and Madani, S. A. (2017). Diet-right: a smart food recommendation system. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. (TIIS) 11 (6), 2910–2925.

Sahoo, A. K., Pradhan, C., Barik, R. K., and Dubey, H. (2019). DeepReco: deep learning based health recommender system using collaborative filtering. Computation 7 (2), 25. doi:10.3390/computation7020025

Schäfer, H., Elahi, M., Elsweiler, D., Groh, G., Harvey, M., Ludwig, B., et al. (2017). “User nutrition modelling and recommendation: balancing simplicity and complexity,” in Adjunct publication of the 25th conference on user modeling, adaptation and personalization, 93–96.

Thakur, A., Ranga, V., and Agarwal, R. (2025). Exploring the transformative impact of blockchain technology on healthcare: security, challenges, benefits, and future outlook. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 36 (3), e70087. doi:10.1002/ett.70087

Theodore Armand, T. P., Kim, H. C., and Kim, J. I. (2024). Digital anti-aging healthcare: an overview of the applications of digital technologies in diet management. J. Personalized Med. 14 (3), 254. doi:10.3390/jpm14030254

Toledo, R. Y., Alzahrani, A. A., and Martinez, L. (2019). A food recommender system considering nutritional information and user preferences. IEEE Access 7 (1), 96695–96711. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2929413

Xu, R., Zhu, J., Yang, L., Lu, Y., and Xu, L. D. (2024). Decentralized finance (DeFi): a paradigm shift in the Fintech. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 18 (9), 2397630. doi:10.1080/17517575.2024.2397630

Yang, L., Hou, Q., Zhu, X., Lu, Y., and Xu, L. D. (2025). Potential of large language models in blockchain-based supply chain finance. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 19 (11), 2541199. doi:10.1080/17517575.2025.2541199

Keywords: blockchain, federated learning, healthcare, nutrition, PHNI, recommendation system

Citation: Venkata Krishna P, Saritha V, Pachipulusu P, Aruna M and Jayasri P (2026) Blockchain-enabled real-time personalized nutrition recommendation framework using IoT and AI. Front. Blockchain 9:1765645. doi: 10.3389/fbloc.2026.1765645

Received: 11 December 2025; Accepted: 13 January 2026;

Published: 06 February 2026.

Edited by:

Yang Lu, Beijing Technology and Business University, ChinaReviewed by:

Lei Yang, Shenyang University of Technology, ChinaJiaLin Liu, Beijing Technology and Business University, China

Copyright © 2026 Venkata Krishna, Saritha, Pachipulusu, Aruna and Jayasri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: P. Venkata Krishna, cGFyaW1hbGF2a0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

P. Venkata Krishna

P. Venkata Krishna V. Saritha

V. Saritha Pratap Pachipulusu

Pratap Pachipulusu M. Aruna4

M. Aruna4 P. Jayasri

P. Jayasri