- Wood Science and Engineering Department, College of Forestry, Oregon State University, Corvallis, United States

Carbon sequestration benefits of mass timber (MT) buildings are maximized when their lifespan is extended. Designing MT buildings that are durable and capable of future adaptation is recognized as a direct strategy for prolonging carbon storage before end-of-life interventions are undertaken. Previous studies have identified criteria for flexible design mostly through theoretical research and not specifically for MT. No research has examined whether, and how, adaptability-related decisions are made in real-world MT project workflows. This study builds on an earlier work by mapping these processes. It identifies who makes critical decisions, when in the project timeline it occurs, and which digital tools are used. We conducted a global questionnaire survey of MT stakeholders, analyzing 106 responses. Four criteria emerged as most important overall: structural grid configuration, standardization and compatibility, modularity and scalability, and the location of building cores and services. The schematic design and construction documentation phases were critical decision points, yet certain disciplines were not engaged when their input was required. A convergent design approach that brings all the key actors together is essential at key points, with particular emphasis on the role of MT manufacturers/fabricators. Parametric and simulation workflows, which support stakeholders in co-evaluating adaptability and other design objectives simultaneously, were rarely adopted. However, they can support rapid iteration, real-time feedback in design exploration, and when coupled with analysis and simulation tools, can accelerate progress from schematic design to fabrication drawings. The outcomes of this study can be used to inform future strategies for improving early-stage collaboration and tool interoperability in support of adaptable MT design.

1 Introduction

Carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere is the primary reason for global warming, making the reduction of carbon emissions a pressing environmental concern worldwide (Lippke et al., 2021). Forests are sinks for the emitted carbon, prompting discussion on whether their positive role in the carbon cycle can be increased by harvesting trees and sequestering the carbon in long-lived products such as buildings (Arehart et al., 2021). Nevertheless, this is effective only if sustainable forest management is practiced and harvested wood is regrown, allowing the carbon released from decomposition or combustion at the end of products’ life to be reabsorbed (Hudiburg et al., 2019). In this context, mass timber (MT) has received attention as an environmentally sustainable alternative to conventional building materials like steel and concrete (Puettmann et al., 2021), enhancing carbon sequestration through the high levels of wood used in prefabricated panels and linear members. While MT products offer lower cradle-to-gate embodied carbon, the overall impact of MT buildings can still vary by region due to differences in transportation distances and supply-chain logistics. These carbon benefits are maximized when the life of MT components and buildings is extended, thereby prolonging carbon storage (Foster and Kreinin, 2020). Designing for adaptability, also termed flexibility or upgradability (Bocken et al., 2016), extends functional life by enabling buildings to respond to changing human needs (Kamara et al., 2020), thereby delaying end-of-life interventions.

MT construction relies on prefabricated structural elements manufactured under controlled factory conditions. The prefabrication workflow shifts key decisions to earlier phases and necessitates close collaboration between designers and fabricators for successful project delivery in Mass Timber Construction (MTC) (Fallahi et al., 2016; Gosselin et al., 2018; Filion et al., 2024). Designing for adaptability reinforces this need, as provisions for future modifications must be integrated from the outset (Schmidt et al., 2010). Beyond architectural complexity, design for adaptability requires navigating various constraints and contradictions for different building systems, including space layout, structural design, and mechanical, electrical, and plumbing (MEP) systems integration (Serysheva, 2024). Coordinating different building systems can be achieved through a holistic and integrated approach (Mlote et al., 2024).

Seamless data transfer and interoperability between software platforms are especially important in this intricate multidisciplinary workflow. While engineers and designers typically use common Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) digital software packages, timber suppliers rely more on specialized timber design and fabrication tools for timber panel layout modeling (hsbcad, 2025), timber capacity analysis (Canadian Wood Council, 2025), or for generating direct Numerical Control (NC) code for various types of milling lines (Cadwork Informatique Inc, 2025). These specialized tools account for material orientation, product layup, manufacturing and fabrication constraints (Fallahi et al., 2016).

Because collaborative decision-making, coordinated workflows, and effective data sharing are central to successful implementation of MT projects and adaptable design, this study examines whether, and how, adaptability-related decisions are made in MTC. It maps the decision-making process by identifying who makes each decision, when in the project timeline it occurs, and the digital tools used. Outcomes inform strategies for improving early-stage collaboration and tool interoperability.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a background on circular economy (CE) and adaptability in MTC, decision flows, and digital tools. Section 3 outlines the objectives and Section 4 describes the methodology. Section 4.3 presents the findings of the survey, including stakeholder engagement timelines, ranked adaptability criteria, collaboration networks, and patterns of tool usage. In Section 5, we discuss how these findings can inform convergent design workflows, illustrate interoperability and timing gaps, and offer practical recommendations. Finally, Section 6 reflects on limitations and suggests future work directions.

2 Background

2.1 CE and adaptability in MTC

The concept of CE is multifaceted, evolving, and characterized by multiple interpretations (Pearlmutter et al., 2020), as opposed to the linear model of “make, use, dispose,” currently common all over the world (Bruel et al., 2019; Stahel, 2010). CE strategies reduce inputs and waste (Langergraber et al., 2020) via recycling, life-extension (repair/remanufacture/retrofit) (Stahel, 2010), and reduced raw material extraction (Bocken et al., 2016). One of the strategies to enhance buildings’ longevity is design for adaptability and flexibility (Bocken et al., 2016), which enables modification as users’ needs evolve (Pinder et al., 2017). Kronenburg (Kronenburg, 2007) defines adaptability as the capacity to accommodate change in use, or spatial or functional configuration without significant disruption.

Literature on adaptability in timber buildings has focused on structural adaptation (Öberg et al., 2024) and the economic implications (Brigante et al., 2022; Öberg et al., 2025). Findings indicate that combining multiple adaptability strategies in MT buildings raises construction costs (Brigante et al., 2022), while economic feasibility hinges on low initial investment cost (Öberg et al., 2025). Numerous studies have investigated Design for Disassembly (DfD) and reversible connections for MT adaptability (Bakker et al., 2014; Ottenhaus et al., 2023), as well as the effect of DfD factors (e.g., joint design, modularity, prefabrication) on sustainable design outcomes (David et al., 2024). Nonetheless, DfD is only one aspect of technological adaptability, and broader strategies addressing spatial and functional flexibility are also equally critical (Cellucci and Di Sivo, 2015).

Our previous study (Hasani and Riggio, 2025) synthesized design criteria for adaptability from literature and analyzed their implementation in built MT projects. The findings revealed that wider spans via optimized three-dimensional structural grid configuration (Cellucci and Di Sivo, 2015; De et al., 2022; Bettaieb and Alsabban, 2021; Magdziak, 2019; Zivkovic and Jovanovic, 2012) were critical in order to accommodate different layout plans and to increase ceiling-to-floor clearance for easier service integration. This criterion is especially important in MTC where, unlike steel and concrete systems that often follow standardized templates, each project employs a unique structural system (Lam, 2019). While larger grid spans support open layouts, they typically require deeper beams, which reduce ceiling-to-floor clearance and limit horizontal MEP routing. Although clearance was not identified as a standalone criterion, findings in (Hasani and Riggio, 2025) suggested it plays a particularly important role in MTC because MT members have larger cross sections and limitations for embedding services in panels (Hasani et al., 2025a). Grid configuration also directly enables two other highly applied criteria regarding space layout: geometry and dimensions that allow open plan layouts (De et al., 2022; Magdziak, 2019; Zivkovic and Jovanovic, 2012; Slaughter, 2001), and functionally neutral or multifunctional spaces (Cellucci and Di Sivo, 2015; De et al., 2022; Bettaieb and Alsabban, 2021; Magdziak, 2019; Zivkovic and Jovanovic, 2012; Slaughter, 2001; Till and Schneider, 2007; Geraedts, 2016; Israelsson, 2009; Dodd et al., 2020; Malakouti et al., 2019).

Another predominant criterion was the strategic zoning of building cores and service shafts. It can optimize the distribution of open spaces and unfixed usage areas, enable future subdivision of space, upgrades, and replacement of the building’s systems (Cellucci and Di Sivo, 2015; Geraedts, 2016; Dodd et al., 2020). Centralized cores support open floor plans, while distributed shafts shorten service runs and reduce clearance demand. The distributed service layout reduces the need for penetrations or concealed cavities in MT elements and improves accessibility for future changes (Hasani et al., 2025a). Moreover, unlike steel and concrete systems that have decades of standardized, codified solutions for routing utilities, MT relies on proprietary or project-specific details for penetration and service routing, making the integration of MEP more difficult and early coordination of cores and shafts particularly critical. Modularity and scalability, enabling easy assembly, disassembly, or replacement of components (De et al., 2022; Bettaieb and Alsabban, 2021; Magdziak, 2019; Geraedts, 2016), have also been frequently employed across MT projects due to the prefabricated nature of elements such as CLT panels (Hasani and Riggio, 2025). Despite the identified key criteria, there remains a gap in understanding stakeholders’ perspectives on the relative importance of these criteria and the specific roles responsible for their implementation and related decision-making.

2.2 Decision-making and workflow integration for MT adaptability

Conventional building systems such as light-frame wood construction typically favor sequential on-site assembly with field adjustments, for which the traditional Design-Bid-Build (DBB) model is common (Zhong et al., 2022). Under DBB, separate contracts and the lack of fabrication-ready digital handoffs require fabricators to develop their own shop data (Eastman et al., 2011; Almuhannadi and Ghareeb, 2024; Timberlake and Smith, 2010; The American Institute of Architects and Hayes, 2014). Prefabricated projects, such as those utilizing MT, are primarily realized through off-site fabrication and on-site assembly, and the extent of prefabrication is highly influenced by the collaborative structure of the project team (Timberlake and Smith, 2010). When traditional delivery methods are used for MT projects, lack of upfront coordination can extend overall project duration, increase costs, raise the risk of errors, lead to additional rework or change orders during construction, and require more on-site activities (Eastman et al., 2011; Kortenko et al., 2020).

Since prefabrication is inherently about process, its success can be enhanced by adopting an integrated delivery model (Timberlake and Smith, 2010). Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) integrates people and practices in a collaborative workflow (Owen, 2019) to enhance project value, reduce waste, and maximize efficiency (American Institute of Architects and AIA California Council, 2007). It is enabled by early goal definition, early involvement of participants (Ng et al., 2023), and collaborative decision-making, as conceptualized in the MacLeamy Curve (American Institute of Architects and AIA California Council, 2007; Ilozor and Kelly, 2012). Decisions on “what” to be designed, by “who” and “how” are jointly determined not only by the owner and architect, but also contractors, engineers, fabricators, and subcontractors (Timberlake and Smith, 2010). For example, CLT panel dimensions (what) must be finalized early with fabricator input (who) based on press bed capacity and transport logistics (how) (Brandt et al., 2019). Panel size and layup/thickness also affect span length and structural performance (how) that requires a structural engineer’s input (who) (FPInnovations, 2013). IPD facilitates early information sharing so that design information is more readily transitioned into shop data, particularly when supported by a platform for shared data exchange (Langston and Zhang, 2021; Rashidian et al., 2024). Early alignment and coordination shortens design delivery, creates an opportunity to merge fabrication and construction documentation, and allows faster off-site fabrication and on-site assembly (Timberlake and Smith, 2010).

Beyond the general need for early collaborative coordination in prefabricated MT projects, adaptability is shaped by a set of interrelated design and construction criteria. These criteria, ranging from structural grid configuration to service integration, require timely decisions from multiple disciplines. Here, using sequential, document-driven workflows limits MT adaptability opportunities because design parameters must be locked in before the fabrication of MT components begins (Coelho et al., 2023). In addition, design for adaptability in buildings is inherently a multi-layered process, as structural grids, building envelopes, and service systems each have different lifespans, performance requirements, and modification needs (Kamara et al., 2020; Brand, 1995; Hamida et al., 2022). To truly achieve adaptable buildings, these criteria should be integrated across different building systems and coordinated early. Without this alignment, decisions in one layer, such as structural span arrangements, may preclude or complicate adaptability in others, like façade modulation or service routing (Askar et al., 2021; Rinke, 2023; Hasani et al., 2024).

Different criteria for adaptability create trade-offs in the decision-making of MT projects. For example, structural grid configuration criterion seeks larger spans, which improves flexibility but increases MT member sizes and costs (Chaggaris et al., 2021). This can potentially conflict with architectural layout goals and the manufacturer’s maximum allowable sizes (WoodWorks, 2024). For the geometry and dimension of space, structural engineers designing load-bearing walls in panelized MT systems may restrict open-plan layouts, sought after by architects (Encina and de la Llera, 2013). Vertical service shaft placement and zoning must coordinate with lateral-force-resisting systems and spatial planning, requiring close coordination among structural and MEP engineers and the architect (Moehle et al., 2012). Horizontal service routing, determined by core zoning, should be planned for integration, such as through pre-drilled holes in glulam beams or cavities in CLT walls using CNC technology in the facility (WoodWorks, 2025). Once MT elements are cut and delivered to the site, changes for new or relocated paths can be costly or cause major delays (Koppelhuber et al., 2015). Lastly, designing with custom MT elements can improve initial design freedom, a goal for the architect, but may add cost for owners and limit future modification if the products become unavailable or face supply chain constraints. That is why modularity and scalability, i.e., designing with available standard MT products, is a key criterion in MT adaptability, aligning with Design for Manufacturing (DfM) principles.

Existing literature largely consists of reviews and practitioner perspectives, typically examining industry barriers in a broad, qualitative manner. Studies have explored stakeholder perspectives on the economic, social, and environmental incentives for designing timber buildings suitable for circular use (Brigante et al., 2022; Öberg et al., 2025; Jockwer et al., 2020; Kremer et al., 2025a). Others have examined the MTC supply chain as a co-evaluation of design–fabrication–installation trade-offs (Coelho et al., 2023), and as a value network (rather than a linear chain), where design-build early involvement enables collaboration and innovation (Gosselin et al., 2018). Research has recommended Translational Design and Construction and interdisciplinary collaboration as key levers (Kremer et al., 2025b), while social-network analysis illustrated a collaboration network dominated by upstream manufacturers and engineer/contractor hubs (Said et al., 2024). Other studies underscored the importance of engagement in multistory timber (Bruno et al., 2025), and identified fabricators as key innovators, while stressing collaboration with suppliers, contractors, and designers (Orozco et al., 2023). While this prior work has highlighted key aspects of the MT value chain, we identify a knowledge gap regarding how key criteria for adaptable design are addressed within implemented MT workflows, specifically concerning the roles of stakeholders (e.g., architects, manufacturers, contractors) and the decision-making phases they engage in (from pre-design to closeout).

2.3 Digital tools and data exchange for adaptable MT design

Technologies that support shared data exchange for a collaborative design workflow include Building Information Modeling (BIM) platforms, clash detection software, and parametric modeling tools (e.g., Grasshopper (Robert McNeel and Associates, 2023), Dynamo (Autodesk, 2025)). In MT projects, prefabrication decisions are typically finalized within a CAM workflow, which translates the coordinated design model into instructions for CNC fabrication. Early accurate geometry/material modeling reduces Requests for Information (RFIs), change orders, redesign loops, schedule/cost risks, and on-site rework (Ogundare and Tokunbo, 2025; Autodesk, 2022).

The MT industry does not follow the usual commodity pattern and uses custom components. Variations in grade, species of lumber, layup configuration, and equipment used in manufacturing plants, such as press bed capacities and the adhesive system, can significantly alter member size and thickness, as well as allowable design values (Atkins et al., 2023). These constraints directly impact adaptable design. Modularity and scalability (key criteria for adaptability) cannot rely on generic structural module sizes, such as the typical 9 × 9 m bay used in residential concrete flat-slab construction (Lam, 2019). Such modules must align with vendor capabilities and be incorporated into digital tools.

In conventional materials, such as steel, design values are standardized (Bartlett et al., 2003) with built-in libraries/databases (Computers and Structures Inc, 2022), and commodity light-frame wood is standardized by species/grade (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2021). However, most commercially available design software for MT incorporates generic design values, while only a few packages (Canadian Wood Council, 2025; CLT Toolbox Pty Ltd, 2024) include proprietary, manufacturer data. Because these variations affect design choices, manufacturer-specific data should be incorporated early to avoid major redesign after a supplier is engaged. Software must also allow anisotropic properties by layups (Dlubal Software GmbH, 2025), proprietary connectors (Chen et al., 2022), and additional parameters, such as availability, shipping, logistics, and cost.

Tool interoperability, i.e., the ability to exchange data across different software and platforms, is a persistent challenge in collaborative design workflows (Sacks et al., 2018). This challenge is amplified in the AEC sector due to diverse disciplines, which often use proprietary data schemas, resulting in file formats that are sometimes incompatible (e.g., .rvt, .ifc, .dwg, .step), stand-alone, domain-specific software (e.g., Revit, AutoCAD, ETABS, etc.), and different tools for wood design (e.g., hsbcad, Sizer, etc.). This hinders geometry/metadata/performance exchange (Jansson et al., 2018) between project teams and necessitates data translation or manual rework (Wang et al., 2023). Parametric design tools could facilitate collaboration, by automatically updating models to reflect changes made by different team members and support multiple design objectives simultaneously (Lombardi and Ruttico, 2023; Hasani et al., 2025b).

However, not all project stakeholders have the same level of digital maturity or access to digital platforms (Lavikka et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2025). There is therefore a need to investigate how current digital tools and data exchange workflows in MT projects address these limitations, or whether new tools should be developed to support the integration of multiple objectives from diverse stakeholders to streamline adaptability strategies in MTC.

2.4 Summary of literature and identified research gap

While MT’s potential to extend carbon storage by adaptability is recognized, adaptability-related decision-making in MTC is still unclear. Key criteria for flexible design (e.g., structural spans, clearances, service zoning, and modularity) have been identified in previous studies, but they are based mostly on theoretical research and not specifically on MT projects. The importance of integrated coordination for implementing flexibility has been discussed in broader building-design literature (Askar et al., 2021; Rinke, 2023). However, how MT stakeholders perceive, prioritize, and assume responsibility for these criteria in real projects has yet to be determined. Studies have highlighted interdisciplinary collaboration, supply-chain trade-offs, early involvement, and the central roles of manufacturers, fabricators, and suppliers in MTC broadly (Gosselin et al., 2018; Coelho et al., 2023; Kremer et al., 2025b; Said et al., 2024; Bruno et al., 2025; Orozco et al., 2023). Still, when designing for adaptability, there is little knowledge of responsible stakeholders and timing of decisions across project phases in actual MT workflows. Despite advancements in BIM, CAM, and parametric modeling, available tools still lack manufacturer-specific data or suffer from poor interoperability between disciplines. Such constraints have direct implications for MT adaptability yet remain underexplored in the literature. Bridging these gaps offers opportunities to provide insights to enhance decision-making, improve data exchange, and facilitate collaborative workflows for MT adaptability.

3 Objectives

To address the above-mentioned gaps, this paper aims to map how adaptability-related decisions are currently made in MT projects, by whom, at what stage of the project timeline, and using which digital tools. It also investigates barriers to implementing adaptable designs of MT buildings. The four objectives are described as follows.

a. To identify and prioritize key criteria for adaptable design perceived by MT stakeholders and examine how these vary across roles, revealing possible misalignments.

b. To map which stakeholders are engaged at different stages of MT design and construction, highlighting hand-offs (both between actors and between tool inputs), gaps, and re-work loops that can compromise flexibility.

c. To determine the key expertise required for implementing each key criterion for flexible MT design, and when paired with (b), assess misalignments between needed and present skills.

d. To identify digital tools adopted by each stakeholder in each phase of design and construction and evaluate their capacity to support integrated design and interoperable data flow required to deliver adaptable MT project.

4 Methodology

This study employed qualitative research methods to assess the current MTC industry. A questionnaire survey was designed and distributed among MT industry professionals, including “Architects”, “Structural Engineers”, “MEP Engineers”, “Contractors”, “MT Manufacturers”, and “MT Fabricators” globally. The aim was to gather and analyze input across diverse roles to determine the level of adoption of integrated design (by input exchange between different roles and tools), and to identify potential areas for enhancing multidisciplinary collaboration for greater adaptability in MT projects.

4.1 Development of questionnaire survey

The study employed a questionnaire survey to address four main objectives related to MTC on a global scale: a) to identify key design strategies for adaptability, b) to evaluate current expertise involvement in different project stages c) to determine roles and collaborations required to implement these strategies, and d) to map current tool adoption and their level of interoperability to support integrated design tasks during the design and construction phases. The research team designed a qualitative questionnaire with closed-ended and open-ended questions on the cloud-based platform Qualtrics. Qualtrics enables users to create and distribute surveys easily via a simple web link (Qualtrics International Inc, 2024). The survey comprised seven questions aligned with four objectives, as detailed in Figure 1. Q1 screened MT project experience and routed respondents accordingly. Q2 captured the primary role of the respondents. Q3 rated involvement across six project stages (Likert). Q4 ranked the top three adaptability criteria. Q5 mapped expert collaborations required for each selected criterion. Q6 listed tools/software used at the stages where respondents were involved. Q7 captured barriers/challenges with examples for implementing MT buildings that will be adaptable in the future (full description is detailed in Supplementary Appendix A).

4.2 Sample selection and survey distribution

This survey was specifically designed for distribution among a targeted sample of professionals with experience in MT projects. Distribution occurred in person and online globally, and targeted numerous stakeholder groups in order to have diverse outreach. The return rate of the survey could not be calculated due to its distribution on platforms like LinkedIn. In total, Qualtrics recorded 138 responses. Out of the 138 recorded responses (based on the answer to Question 1), 16 respondents were not within the target audience as they did not have experience in MT projects. Of the remaining responses, 9 lacked responses to further questions after Question 1 and were subsequently excluded from the analysis, resulting in 113 responses (82%) for further analyses. More details on sample selection and survey distribution are provided in the appendix.

4.3 Data analysis and results

This section summarizes the findings of the study, structured according to the four objectives outlined in Section 4.1. The analysis begins with respondent demographics, which include data cleaning. The final part of this analysis presents major recommendations derived from the last question. In this approach, it is possible to obtain a full overview of the current landscape and opportunities for the advancement of adaptability in MTC.

4.3.1 Respondents’ demographic and stages involvement (Objective b)

Figure 2 illustrates how 113 respondents were distributed across roles, as derived from responses to Question 2. Of these, 21 entries identified roles not listed among the given six, which required data cleaning. Therefore, some entries were merged with existing roles or categorized under others. The groups representing MT manufacturers and MT fabricators were collapsed into a single category to simplify reporting. This decision reflects the overlap of activities in many companies and the often-blurred roles within the industry. In addition, 7 responses from individuals in academia (researchers, teachers, instructors, or students) were excluded from further analysis, since the survey was exclusively designed for industry professionals in MTC, resulting in 106 responses. Specifically, 30 of the respondents (26%) were structural engineers, 26 (23%) were architects, 19 (17%) were MT manufacturers/fabricators, 14 (12%) were contractors, 12 (11%) were MEP engineers, and 5 (5%) fell into the “Others” category.

Figure 2. The distribution of roles (Question 2) among 113 respondents who provided complete responses to the questionnaire, of which 106 were selected for further analysis.

Next, quantitative statistical methods were employed to compare the involvement of different roles throughout the project lifecycle, as derived from responses to Question 3. Each respondent had only a single choice for each stage and could not skip any of the stages, thus ensuring complete data on all phases were collected. Answers on the 3-point Likert scale were quantified in equal intervals that corresponded to values of 0.0, 0.5, and 1.0 (Han et al., 2011). Further, measurements were normalized to a standard scale using the Normalized Fuzzy Score (Ragin, 2000), given the differences in the number of respondents within each group and differences in confidence when responding. Confidence levels (Jin et al., 2012) were assigned as percentages (i.e., 80% for “Moderately involved”) in order to capture the conditional or situational nature of “Moderate involvement,” which varies more than the clearly well-defined extremes of “Very involved” or “Not involved.” The resulting group-stage score was computed as the mean of each response multiplied by its confidence level:

Figure 3 shows the results corrected for the varying number of respondents per expertise group, where darker shading indicates greater engagement. Architects were most active from the initiation and planning stage up to the regulatory compliance and permits stage, with their role diminishing from the physical construction and assembly stage onwards. Structural engineers exhibited a similar pattern of involvement, although their peak participation occurred slightly later, during the schematic design and design development. MEP engineers joined the project at the construction documents stage and remained active through the end of the construction and assessment/inspection. Contractors were predominantly engaged in the later processes, with most activity during the physical construction and assembly phase. MT manufacturers/fabricators showed the greatest involvement during construction and assembly but also had noticeable activity at other stages, particularly during initiation and planning.

Figure 3. Normalized scores for each stakeholder group’s involvement across design and construction stages (Question 3), derived from 106 responses and calculated using the normalized fuzzy score method to quantify involvement.

4.3.2 Importance of adaptability characteristics by expertise (Objective a)

Question 4 applied a forced-choice format to identify key adaptability characteristics. Each respondent was required to select exactly three items from the list and rank them in order of importance or preference, and no repetition of ranking or multiple ranks per characteristic was permitted. This method guarantees that all criteria are ranked against one another rather than in isolation (De Chiusole and Stefanutti, 2011). The Modified Borda Count (MBC) method was used to assign weights to the three ranks (Kamwa, 2022). Specifically, we used an inverse rank weighting system (1/r for rank r) so that lower ranks contribute progressively less to the total score, and the distribution of scores approximates the true distribution of preferences (Cormack et al., 2009). Scores were obtained by taking the mean of the weighted ranks for each group.

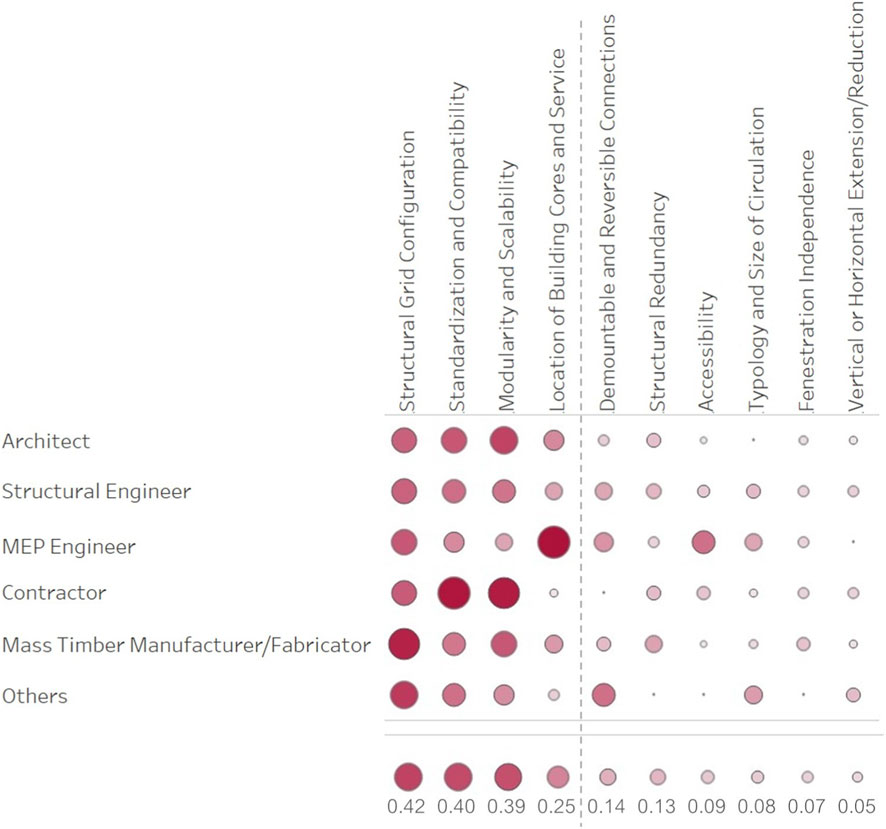

The resulting normalized scores are visualized in Figure 4, where the color and size of the dots indicate the level of importance assigned to each criterion within each group. Architects notably assigned priority to three criteria: structural grid configuration, standardization, and modularity. Structural engineers shared the same priorities but placed additional emphasis on demountable and reversible connections. Contractors similarly prioritized modularity and standardization but placed less emphasis on the location of building cores and service and demountable and reversible connections compared to architects and structural engineers. MEP engineers ranked the location of building cores as their highest priority, followed by structural grid configuration and accessibility. MT manufacturers/fabricators had similar preferences as architects, structural engineers, and contractors, with particular emphasis on structural grid configuration. The last row in Figure 4 totals the ratings among all respondents and ranks the combined importance of the criteria irrespective of specific roles. A statistically significant drop in scores from 0.25 to 0.14 serves as a natural cutoff point, distinguishing the four most important criteria overall: structural grid configuration, standardization and compatibility, modularity and scalability, and the location of building cores and services.

Figure 4. Importance of adaptability characteristics (Question 4) by expertise, derived from 93 responses.

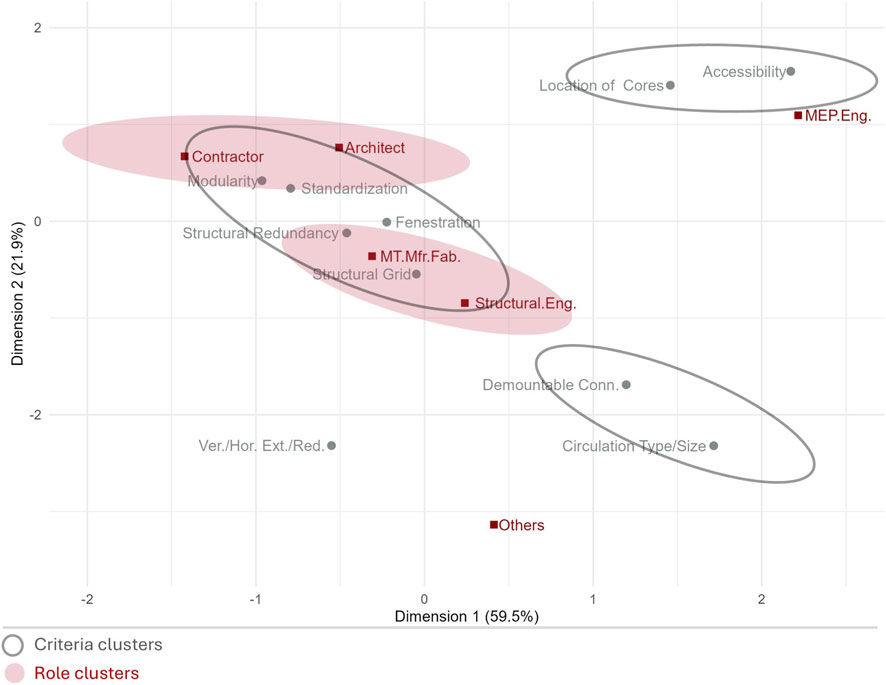

To map roles and criteria in a shared two-dimensional space, correspondence analysis (CA) (Simkin and Hastie, 1987) was conducted to examine associations between categorical variables (i.e., roles in AEC and criteria). Hierarchical clustering with complete linkage (Everitt et al., 2011) on pairwise Euclidean distances was then applied to the CA results to reveal patterns or clusters of experts with overlapping priorities. Random noise was introduced by adding moderate variations to the original coordinates of the data points to account for variability and enhance clustering robustness. Confidence ellipses were subsequently plotted around the mean coordinates of the clusters (i.e., cluster centroids).

The CA plot (Figure 5) depicts the clustering of roles (red) and criteria (grey) for the MT industry, where 59.5% of the variance is captured along Dimension 1 (horizontal axis) and 21.9% of the variance along Dimension 2 (vertical axis). Together, they explain 81.4% of the association between roles and criteria. One cluster of roles, consisting of contractors and architects, along with another cluster with structural engineers and MT manufacturers/fabricators, are positioned near a cluster of criteria that includes modularity and scalability, standardization and compatibility, structural redundancy, structural grid configuration, and fenestration independence. A second cluster of criteria, namely accessibility and location of building cores and services, was close to MEP engineers. Lastly, factors such as demountable and reversible connections and typology and size of circulation, although relatively isolated, showed alignment with structural engineers. All these clusters indicate how different professional roles prioritize specific criteria in order to enable flexible design of MT building projects.

Figure 5. Correspondence analysis plot showing the importance of adaptability characteristics (grey) by expertise (red) based on 93 responses. A total of 59.5% of the variance is captured along Dimension 1 (horizontal axis) and 21.9% along Dimension 2 (vertical axis). Together, they explain 81.4% of the association between roles and criteria.

4.3.3 Required roles for implementing key criteria for adaptability (Objective c)

In Question 5, participants were asked to specify the roles that must collaborate to implement their prioritized criteria. Unlike the respondents’ areas of expertise referenced in Question 2, the roles mentioned here refer to those deemed necessary for achieving each criterion, independent of respondents’ actual roles. Respondents were required to provide at least one role for each of the three criteria, ensuring complete responses across all items and allowing them to include as many roles as they considered relevant. Before delving into a detailed analysis of collaboration for each criterion, a network analysis was conducted to identify the intricate interrelationships among roles for implementing flexibility across all criteria. Role pairings were established and visualized in a chord diagram (Figure 6), with the thickness of arcs indicating the frequency of interactions. The results revealed that the most critical roles for enabling flexibility in MT buildings, ranked from highest to lowest, were structural engineers (cited 217 times), architects (215 times), MT manufacturers/fabricators (161 times), contractors (123 times), and MEP engineers (90 times).

Figure 6. Network analysis demonstrating the frequently of pairwise role collaboration and their distribution across the roles, derived from Question 5 and based on 93 responses.

The communication patterns showed that the collaborations perceived as most relevant to implementing adaptability occurred between architects and structural engineers, followed by MT manufacturers/fabricators with structural engineers and with architects. Results indicated that contractors were expected to maintain moderate collaborations with architects, structural engineers, and MT manufacturers/fabricators. MEP engineers were perceived to maintain relatively consistent and moderate pairwise interactions with all specified roles.

Figure 7 illustrates the roles identified by respondents for implementing each cluster of criteria, grouped based on the three clusters shown in Figure 5. Cluster A was further subdivided into two detailed groups, and the vertical or horizontal extension/reduction criterion was added to Cluster C. For each of these four groups, a radar chart is presented. The visualizations use absolute scales in the form of raw numbers of citations per selected role and not normalized by cluster or criterion. Therefore, larger shapes in the charts indicate greater citation rates for those criteria (derived from Question 4). In addition, shapes closer to a perfect circle indicate a balanced distribution, while skewed shapes with sharp edges indicate a stronger emphasis on the roles represented by those vertices. In all the clusters, the key roles identified were architects, structural engineers, and MT manufacturers/fabricators, except for Cluster B (location of building cores and services and accessibility), where MEP engineers were emphasized.

Figure 7. Raw citation counts per selected role on an absolute scale for four criteria groups (Question 5), based on 93 responses: A-1 (Modularity and Standardization); A-2 (Structural Grid, Structural Redundancy, and Fenestration); B (Location of Cores and Accessibility); C (Ver./Hor. Ext./Red., Demountable Connections, and Circulation Type/Size).

4.3.4 Tools and platforms used by expertise (Objective d)

This section analyzes the usage of software and tools by experts in MT projects, based on the responses provided for Question 6. Notably, out of the 106 participants, only 93 continued responding beyond Question 3 through Question 6; therefore, the results are presented for this subset.

The analysis began with a predetermined list of common AEC industry tools. The respondents were also encouraged to list any other tools they utilized in MT projects, which led to an accordingly expanded list. However, provided tools that did not receive any mentions were excluded from further analysis. Then all the mentioned tools were classified into six main functional groups as detailed in Table 1. This categorization was primarily on the basis of each tool’s main feature, despite some tools having multiple functions or features.

Table 1. Classification of software and tools used in MT design and construction stages into six groups based on their main features or functions.

The bee swarm diagram (top) in Figure 8 illustrates the dynamic utilization of various tool groups throughout the six stages of design and construction in MT projects. It shows the dominant tools and the fluctuating prominence of specific tool groups at different phases. The size of the circles, from the smallest at one mention to largest at 124 mentions, quantifies each group of tools’ frequency of reference by stage. Initially, tools categorized under CAD and collab oration dominate the early stages (from stages 1–3), specifically in initiation and planning, schematic design, and construction documents. Together with these, analysis and simulation, followed by design automation, were the second most frequently mentioned set of tools, though at a noticeably lower rate. As projects progress to the permits stage and then to construction and assembly, a transition is observed towards CM/PM and CAM tools.

Figure 8. Categories of software and tools (Question 6) used by professionals at six stages of design and construction of MT buildings, derived from 93 responses (top: quantified tool usage across all roles; bottom: normalized role-specific differences at each project phase).

The stacked bar chart in Figure 8 (bottom) details role-specific variation in tool preference (normalized) by project phases. Architects and MEP engineers consistently prioritized CAD and collaboration tools in nearly all phases of the project. Structural engineers also predominantly used these tools but showed slightly more preference for analysis and simulation tools. Design automation tools were primarily used by architects and structural engineers, respectively, in earlier project stages. Contractors, and particularly MT manufacturers/fabricators, exhibited a strong preference toward CAM and CM/PM tools in construction and inspection phases, which reflects a clear trend away from design-based tools (like CAD, design automation) towards production-oriented tools. An exception was observed among MT manufacturers/fabricators in the final stage, where they heavily relied on analysis and simulation tools.

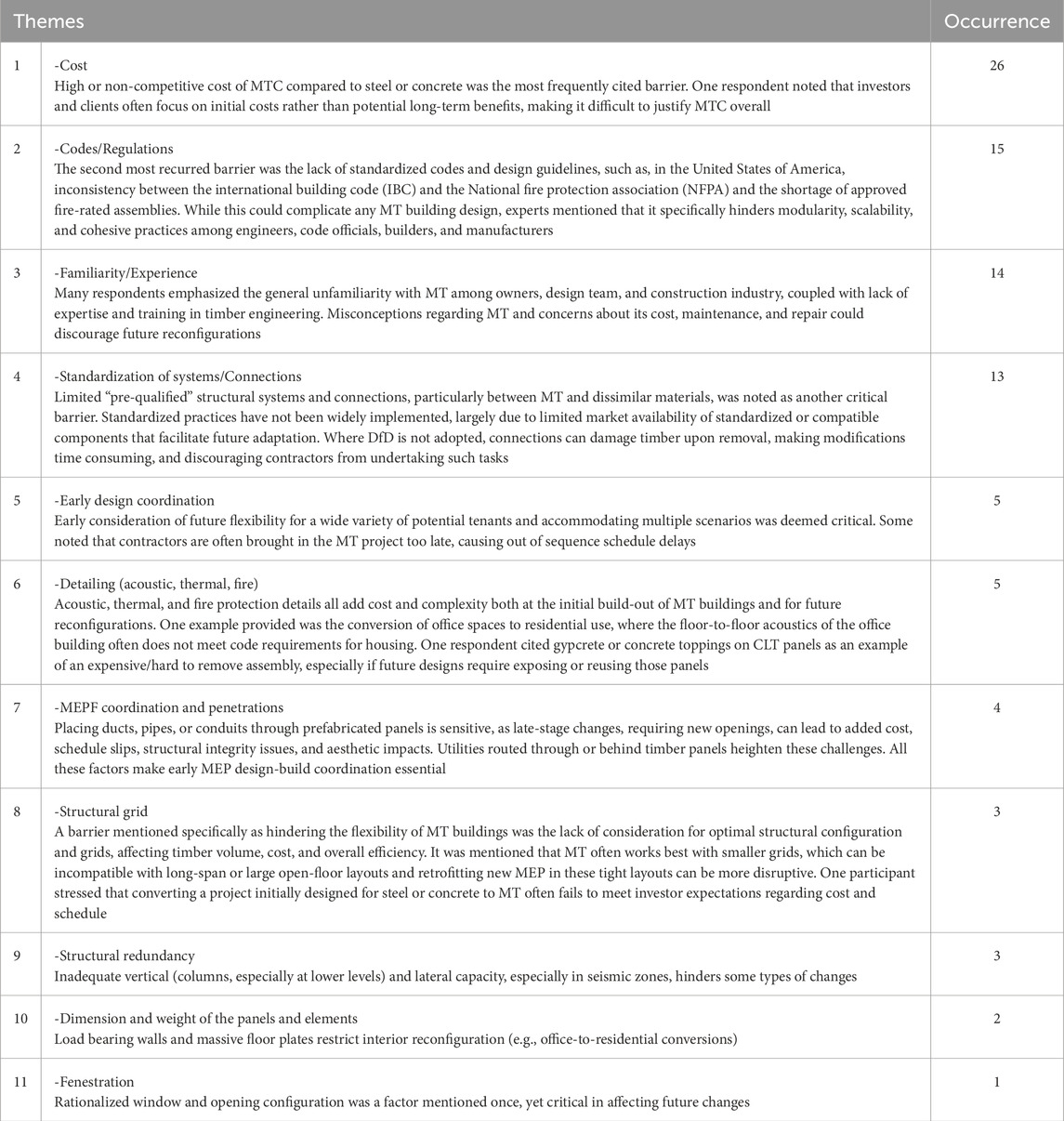

4.3.5 Barriers and challenges

In Question 7, an optional, open-ended prompt, 55 respondents provided qualitative answers. Thematic analysis of these responses produced 11 recurring categories. Some participants approached this question by highlighting barriers relevant to MTC broadly, such as cost, codes and regulations, industry familiarity, and standardization. Supply chain issues were also noted, but approached mainly around implementation of MTC rather than adaptability. These broader barriers are recognized as emerging factors that influence future decision-making flows. Table 2 summarizes only the barriers directly related to design for adaptability in MT, presented in order of occurrence. The results indicate that cost and codes/regulations were the two most frequently cited obstacles, followed by public familiarity/industry experience and standardization of systems/connections.

Table 2. Eleven themes identified as barriers and challenges in the design and construction of adaptable MT buildings.

In addition, some respondents provided opportunities or suggestions to overcome the mentioned barriers, but not consistent across all responses. In terms of cost challenges, one respondent highlighted that there is potential willingness to invest in MT if there is sufficient data on its long-term performance. Regarding the lack of coordination and early considerations for flexible design, one proposed solution was to involve MEPF design-build teams as early as the schematic design phase, even though it raises upfront coordination costs. This approach, however, can support practical and constructible MEPF design, streamline later phases, minimize preconstruction BIM coordination, and reduce change orders. Lastly, one respondent suggested the integration of digital technology as a solution for enabling design and construction of adaptable MT buildings, describing it as “the next frontier of time savings.”

5 Discussion

5.1 Stakeholder engagement timeline vs criteria implementation phases

Based on the results of the criteria ranking, the top four adaptability strategies identified by industry experts closely align with those most frequently applied in our earlier study analyzing adaptability in real-world MT projects (Hasani and Riggio, 2025). In both findings, the grid configuration for wider structural spans was the leading strategy. Table 3 summarizes these findings along with the required roles, decision flow, and primary tools employed, and also suggests tools for enhancing the implementation of the criteria and collaboration among experts.

Table 3. Key criteria for MT adaptability (col 1), required roles ranked by priority (col 2), timeline map highlighting each expert’s stage of high engagement and decision-making (col 3), primary tools used by each role at the decision-making stage (col 4), and recommended supporting tools for implementating each criterion (col 5).

In Table 3, for each key criterion, a list of key stakeholders whose input is essential is provided. Each actor’s primary involvement, derived from Figure 4, is mapped onto the project timeline. The timeline also highlights the decision-making phase for each criterion, i.e., the phase during which applying the strategy is most effective. For all four criteria, the schematic design and construction documentation phases are critical decision points. Yet, not all disciplines engage at those stages where their input is required. In particular, MT manufacturers/fabricators, MEP engineers, and contractors tend to join the project later than ideal, and their delayed input or late design revisions may omit parameters that inform flexible design. Our findings align with previous MTC collaboration studies (Gosselin et al., 2018; Coelho et al., 2023; Kremer et al., 2025b; Said et al., 2024; Bruno et al., 2025; Orozco et al., 2023) and research emphasizing early integrated coordination to support flexibility in buildings (Askar et al., 2021; Rinke, 2023). Without proactive assessment of trade-offs between multidisciplinary objectives and constraints, the design process is likely to face costly and time-consuming revisions downstream (Mostavi et al., 2017). In this context, although the integrated design approach is well established in architectural practice for early multidisciplinary collaboration among stakeholders, it does not necessarily incorporate computational methods or optimization strategies. In contrast, a convergent design approach employs parametric modeling and multi-criteria optimization to generate design alternatives and evaluate trade-offs among structural, architectural, and fabrication constraints simultaneously.

5.2 Tool inconsistencies and interoperability gaps

The primary tools employed by key actors at the decision-making stage for each criterion (Table 3) show that they are inconsistent among different roles, and certain effective tools are missing. In the same table, we recommend a list of supporting tools for all stakeholders that facilitate seamless implementation of each criterion. CAD platforms are fundamental for all criteria due to their precision and versatility in visual modeling across diverse engineering disciplines (Liu, 2024). Configuring the structural grid for wide spans specifically benefits from design automation and parametric modeling tools (e.g., Grasshopper, Dynamo) to treat span dimension as a variable, get input parameters from architects, structural engineers, and manufacturers, and explore optimized layouts (Liu, 2024) for higher flexibility. This can support rapid iteration and real-time feedback in design exploration (Ajtayné Károlyfi and Szép, 2023). Coupling these with analysis and simulation software enables early structural performance evaluation. It also accelerates progress from schematic design to fabrication drawing with fewer iterations (Hasani et al., 2025a). For both standardization and modularity, the use of parametric automation can support implementing standardized details and optimizing modular configurations. CAM tools ensure dimensions, connection details, and tolerances are consistent from model to CNC files to minimize on-site fitting issues (Brown, 2023). Collaboration and coordination platforms, such as Revizto, Microsoft 365, and Google Workspace, specifically apply to standardization by documenting standards for future replacements or alterations. Lastly, designing building cores and shafts for future adaptations requires coordination tools for clash detection (Akponeware and Adamu, 2017; Tommelein et al., 2012), and analysis/simulation tools for assessing performance implications of core positioning. In sum, despite the advantages of parametric and simulation workflows, our survey reveals relatively low adoption of these tools. Together with limited manufacturer-specific data upstream, the findings suggest that translational, interdisciplinary practices advocated in the literature (Kremer et al., 2025b) are not yet fully implemented. This could signal a knowledge gap or resistance to adopting new technological enablers.

6 Limitations and future research

One of the limitations of this study is related to the survey administration. Because of online distribution and snowball sampling, the response rate is incalculable; therefore, we cannot assess the representativeness of the sample, especially across regions or company sizes. Future research could focus on obtaining insights from different regions where MT manufacturing and adoption practices vary. Additionally, targeting participants during MT events or through timber networks could introduce bias by over-representing participants with strong MT opinions. Although we increased outreach to under-represented roles during data collection, the number of respondents in each group of professionals still varied. In our analysis from Section 4.3.2 to 4.3.4, the results were normalized for a fair comparison across groups of different sizes. It is worth noting that the higher counts of architects and structural engineers mirror their relative prevalence in actual practice compared to MT manufacturers/fabricators. While contractors and MEP firms are not a small group in the broader construction industry, relatively few identify themselves as MT specialists. We did not explicitly invite specialists in building physics, even though many respondents flagged acoustic, thermal, and fire-safety requirements as critical to MT adaptability. This may limit our understanding of how envelope performance and thermal, acoustic, and fire details constrain future modifications. In practice, however, acoustic or fire engineers often work within MEP or code-review teams, so their input might have been merged under the MEP engineer role rather than captured separately.

Among the tools cited by respondents, only four were designed for timber applications: Cadwork (Cadwork Informatique Inc, 2025) cited by 15 respondents, hsbcad (hsbcad, 2025) cited by 4, Calculatis (Stora Enso Oyj, 2025) cited by 2, and Sizer (Canadian Wood Council, 2025) cited by only 1 respondent. Although using dedicated MT tools can facilitate sharing data across CAD/CAM workflows and provide early input from structural design and fabrication teams, their low adoption cannot be readily attributed to a lack of software packages or training. These packages are highly specialized, and because many firms undertake different project types, not only MT, they default to mainstream platforms rather than timber-specific software. A related limitation is that our classification of tools by primary function may oversimplify multi-functional software. Future studies could analyze data exchange between leading CAD, parametric, and timber-specific platforms, without grouping them based on functionality, to reveal interoperability bottlenecks.

Finally, responses to the last question of the survey (Table 2) show that, although technical tools and role coordination are central to the paper, cost and code limitations, as well as practitioners experience and familiarity with MT, are perceived as even more important by respondents. This raises the question of whether digital tools and convergent design solutions alone can overcome systemic barriers like policy or insurance and suggests areas for future research.

7 Conclusion

While studies have identified adaptability as an important strategy to extend buildings lifespan and carbon storage of MT buildings, the decision-making process in implementing adaptability in actual MT design has been identified as a knowledge gap. This study addresses this gap by providing evidence of how stakeholder roles, decision timing, and digital tools shape adaptability in MT projects. By measuring the relative importance of key criteria and mapping their implementation across project phases, it moves beyond theoretical and project-based insights (Hasani and Riggio, 2025) to confirm and extend them with empirical data. The findings validate our previous key criteria for adaptable design and also clarify who makes the critical decisions and when they should engage (Section 5.1), as well as which tools could be integrated (Section 5.2) for a convergent design approach.

Four criteria were found to be most critical from the stakeholders’ perspective: (i) achieving wider spans by optimizing the three-dimensional structural grid configuration, (ii) standardization and compatibility, (iii) modularity and scalability, and (iv) the location of building cores and service shafts. This finding aligns with an earlier study that analyzed adaptability criteria implemented in real-world MT projects (Hasani and Riggio, 2025). The schematic design and construction documentation phases were key decision points for adaptability and MT prefabrication considerations. Nevertheless, in the MT industry, MEP engineers, MT manufacturers/fabricators, and contractors often engage later than when their input should be incorporated, which leads to redesigns, higher costs, and limited future flexibility. Early collaboration between these stakeholders during these stages can significantly enhance adaptability.

Digital tools used are currently dominated by CAD and coordination platforms, while design automation and parametric modeling tools offer significant benefits: they support structural and spatial optimization for greater adaptability, enable rapid iteration, and accelerate the path from design to fabrication drawings. Embedding manufacturer-specific data upstream also benefits design, while introducing additional coordination and liability considerations for the professionals responsible for the construction documents. Despite these advantages, the adoption of these tools remains relatively limited. Interoperability gaps across platforms further hinder seamless hand-offs.

In current MT practices, the traditional procurement process is still common and preferred by many investors (Atkins et al., 2023). The process follows a linear documentation and review workflow by stakeholders, where fabricators are not fully integrated into design decisions, and contractors are typically brought in after significant portions of the design are complete. Fully integrated workflows are uncommon, and when they do occur, they are often informal among a small network of established collaborators rather than as a formal IPD process. Beyond workflow issues, responses to the survey revealed cost, codes/regulations, and limited familiarity with MT practices as top barriers, and implementing adaptable MT design therefore requires pre-qualified systems/connection standards and clearer regulatory pathways. We recommend a convergent design practice at the schematic design phase that brings all actors together to co-evaluate structural spans, service routing, and fabrication limits in one loop. This workflow may benefit from parametric and simulation tools, incorporating manufacturing-specific constraints, and prioritizing standardization (using available, standardized MT products, details, and connections).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

NH: Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft, Resources, Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – review and editing, Data curation, Project administration, Validation, Formal Analysis, Methodology. MR: Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Validation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbuil.2025.1698068/full#supplementary-material

References

Almuhannadi, M. A., and Ghareeb, A. S. (2024). Enhancing design–bid–build project delivery: a comprehensive review and framework for contractor selection and project optimisation in the construction industry. Organ. Technol. Manag. Constr. an Int. J. 16, 63–80. doi:10.2478/otmcj-2024-0005

Ajtayné Károlyfi, K., and Szép, J. (2023). A parametric BIM framework to conceptual structural design for assessing the embodied environmental impact. Sustainability 15, 11990. doi:10.3390/su151511990

Akponeware, A., and Adamu, Z. (2017). Clash detection or clash avoidance? An investigation into coordination problems in 3D BIM. Buildings 7, 75. doi:10.3390/buildings7030075

American Institute of Architects, AIA California Council (2007). Integrated project delivery: a guide. Version 1, revised edition. Washington, DC. Available online at: https://www.aia.org/sites/default/files/2023-11/ipd_guide.pdf (Accessed August 24, 2025).

Arehart, J. H., Hart, J., Pomponi, F., and D’Amico, B. (2021). Carbon sequestration and storage in the built environment. Sustain Prod. Consum. 27, 1047–1063. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2021.02.028

Askar, R., Bragança, L., and Gervásio, H. (2021). Adaptability of buildings: a critical review on the concept evolution. Appl. Sci. 11, 4483. doi:10.3390/app11104483

Atkins, D., Anderson, R., Dawson, E., Moonen, P., and Muszynski, L. (2023). International mass timber report. Missoula, MT.

Autodesk (2022). Collaborative modular design, decarbonization, and mass timber for sustainable building. San Francisco, CA: Autodesk University. Available online at: https://www.autodesk.com/autodesk-university/de/article/Collaborative-Modular-Design-Decarbonization-and-Mass-Timber-Sustainable-Building-2022 (Accessed July 16, 2025).

Autodesk (2025). Dynamo BIM. Available online at: https://dynamobim.org/(Accessed August 24, 2025).

Bakker, C. A., den Hollander, M. C., van Hinte, E., and Zijlstra, Y. (2014). Products that last: product design for circular business models. Delft: TU Delft Library.

Bartlett, F. M., Dexter, R. J., Graeser, M. D., Jelinek, J. J., Schmidt, B. J., and Galambos, T. V. (2003). Updating standard shape material properties database for design and reliability. Eng. J. 40, 2–14. doi:10.62913/engj.v40i1.800

Bettaieb, D. M., and Alsabban, R. (2021). Emerging living styles Post-COVID-19: housing flexibility as a fundamental requirement for apartments in jeddah. Archnet-IJAR 15, 28–50. doi:10.1108/ARCH-07-2020-0144

Bocken, N. M. P., de Pauw, I., Bakker, C., and van der Grinten, B. (2016). Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Industrial Prod. Eng. 33, 308–320. doi:10.1080/21681015.2016.1172124

Brand, S. (1995). How buildings learn: what happens after they’re built. Penguin Publishing Group. Available online at: https://books.google.com/books?id=zkgRgdVN2GIC.

Brandt, K., Wilson, A., Bender, D., Dolan, J. D., and Wolcott, M. P. (2019). Techno-economic analysis for manufacturing cross-laminated timber. Bioresources 14, 7790–7804. doi:10.15376/biores.14.4.7790-7804

Brigante, J., Ross, B. E., and Bladow, M. (2022). Costs of implementing design for adaptability strategies in wood-framed multifamily housing. J. Archit. Eng. 29, 05022013. doi:10.1061/JAEIED.AEENG-1357

Brown, N. (2023). Mass timber joinery design for digital fabrication and De-constructability. Seattle, WA: University of Washington. Masters Thesis.

Bruel, A., Kronenberg, J., Troussier, N., and Guillaume, B. (2019). Linking industrial ecology and ecological economics: a theoretical and empirical foundation for the circular economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 23, 12–21. doi:10.1111/jiec.12745

Bruno, M., Zanchi, L., Patrizi, N., Neri, E., Rusen, M., Elisei, P., et al. (2025). Finding relevant stakeholders and related social topics for the implementation of social life cycle assessment in the multistorey timber construction sector. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 30, 1264–1280. doi:10.1007/s11367-025-02431-0

Cadwork Informatique Inc (2025). Cadwork - software solutions for wood construction. Available online at: https://cadwork.ca/en/ (Accessed August 22, 2025).

Canadian Wood Council (2025). WoodWorks sizer: software for wood design. Available online at: https://cwc.ca/sizer-can (Accessed August 24, 2025).

Cellucci, C., and Di Sivo, M. (2015). The flexible housing: criteria and strategies for implementation of the flexibility. J. Civ. Eng. Archit. 9, 845–852. doi:10.17265/1934-7359/2015.07.011

Chaggaris, R., Pei, S., Kingsley, G., and Feitel, A. (2021). Carbon impact and cost of mass timber beam–column gravity systems. Sustainability 13, 12966. doi:10.3390/su132312966

Chen, Z., Tung, D., and Karacabeyli, E. (2022). Modelling guide for timber structures. 1st ed. Pointe Claire, QC. Available online at: https://web.fpinnovations.ca/modelling/(Accessed August 24, 2025).

Chen, X., Chang-Richards, A., Ling, F. Y. Y., Yiu, T. W., Pelosi, A., and Yang, N. (2025). Digital technologies in the AEC sector: a comparative study of digital competence among industry practitioners. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 25, 63–76. doi:10.1080/15623599.2024.2304453

CLT Toolbox Pty Ltd (2024). CLT toolbox. Available online at: https://clttoolbox.com/(Accessed August 24, 2025).

Coelho, R. V., Anderson, A. K., and Tommelein, I. D. (2023). “Investigation of the supply chain of mass timber systems,” in 31st Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC31), Lille, France, 824–835. doi:10.24928/2023/0254

Computers and Structures Inc (2022). ETABS v20.2.0 release notes. Available online at: https://www.csiamerica.com/software/ETABS/20/ReleaseNotesETABSv2020.pdf (Accessed August 10, 2025).

Cormack, G. V., Clarke, C. L. A., and Buettcher, S. (2009). “Reciprocal rank fusion outperforms condorcet and individual rank learning methods,” in Proceedings of the 32nd international ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in information retrieval. Editors J. Allan, and J. A. Aslam (New York: Association for Computing Machinery), 758–759. doi:10.1145/1571941.1572114

De Chiusole, D., and Stefanutti, L. (2011). Rating, ranking, or both? A joint application of two probabilistic models for the measurement of values. Test. Psychometrics Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 18 (1), 49–60. doi:10.4473/TPM.18.1.4

David, M.-N., Miguel, R.-S., and Ignacio, P.-Z. (2024). Timber structures designed for disassembly: a cornerstone for sustainability in 21st century construction. J. Build. Eng. 96, 110619. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2024.110619

De, P. S., Lacerda Lopes, C. N., and Neuenfeldt Junior, A. (2022). The use of an analytic hierarchy process to evaluate the flexibility and adaptability in architecture. Archnet-IJAR 16, 26–45. doi:10.1108/ARCH-05-2021-0148

Dlubal Software GmbH (2025). Dlubal RFEM. Available online at: https://www.dlubal.com/en/products/rfem-fea-software/rfem/what-is-rfem?srsltid=AfmBOor94oBWOkWda45exkaOISW_vmFkP0Bf7jHNyKRRJEm57AU2SC5w (Accessed August 10, 2025).

Dodd, N., Donatello, S., and Cordella, M. (2020). Level(s) indicator 2.3: design for adaptability and renovation user manual: overview, instructions and guidance (publication version 1.0). Available online at: https://susproc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/product-bureau/sites/default/files/2020-10/20201013%20New%20Level(s)%20documentation_2.3%20Adaptability_Publication%20v1.0.pdf (Accessed July 4, 2025).

Eastman, C., Teicholz, P., Sacks, R., and Liston, K. (2011). BIM handbook: a guide to building information modeling for owners, managers, designers, engineers, and contractors. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons., 1–31.

Encina, J., and de la Llera, J. C. (2013). A simplified model for the analysis of free plan buildings using a wide-column model. Eng. Struct. 56, 738–748. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2013.05.016

Everitt, B. S., Landau, S., Leese, M., and Stahl, D. (2011). “Hierarchical clustering,” in Cluster analysis. Editors D. J. Balding, N. A. C. Cressie, G. M. Fitzmaurice, H. Goldstein, G. Molenberghs, and D. W. Scott (Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley), 71–110.

Fallahi, A., Poirier, E. A., Staub-French, S., Glatt, J., and Sills, N. (2016). “Designing for pre-fabrication and assembly in the construction of UBC’s tall wood building,” in Modular and Offsite Construction (2016 MOC Summit) Proceedings, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, September 29 - October 1, 2016. doi:10.29173/mocs26

Filion, M.-L., Ménard, S., Carbone, C., and Bader, E. M. (2024). Design analysis of mass timber and volumetric modular strategies as counterproposals for an existing reinforced concrete hotel. Buildings 14, 1151. doi:10.3390/buildings14041151

Foster, G., and Kreinin, H. (2020). A review of environmental impact indicators of cultural heritage buildings: a circular economy perspective. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 043003. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab751e

FPInnovations (2013). U.S. CLT handbook. U.S. edition. Point-Claire, QC, Leesburg, VA: American Wood Council. Available online at: https://www.fpl.fs.usda.gov/documnts/pdf2013/fpl_2013_gagnon001.pdf (Accessed August 24, 2025).

Geraedts, R. (2016). FLEX 4.0, A practical instrument to assess the adaptive capacity of buildings. Energy Procedia 96, 568–579. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2016.09.102

Gosselin, A., Blanchet, P., Lehoux, N., and Cimon, Y. (2018). Collaboration enables innovative timber structure adoption in construction. Buildings 8, 183. doi:10.3390/buildings8120183

Hamida, M. B., Jylhä, T., Remøy, H., and Gruis, V. (2022). Circular building adaptability and its Determinants–A literature review. Int. J. Build. Pathology Adapt. 41, 47–69. doi:10.1108/IJBPA-11-2021-0150

Han, J., Kamber, M., and Pei, J. (2011). “Data transformation and data discretization,” in Data mining. Concepts and techniques (the morgan kaufmann series in data management systems). Editors J. Han, M. Kamber, and J. Pei (Waltham, MA: Elsevier: Morgan Kaufmann), 83–120.

Hasani, N., and Riggio, M. (2025). Achieving circular economy through adaptable design: a comparative analysis of literature and practice using mass timber as a case scenario. J. Build. Eng. 100, 111802. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2025.111802

Hasani, N., and Riggio, M. (2024). “Achieving circular economy in mass timber construction through adaptable design,” in Conference: proceedings of the 67th international convention of society of wood science and technology (SWST 2024). Editor J. Morrell (Portorož, Slovenia: Society of Wood Science and Technology), 204–2011. Available online at: https://www.swst.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/SWST-2024-Final-Proceedings-Editor-copy.pdf (Accessed August 1, 2025).

Hasani, N., and Riggio, M. (2025a). “Optimizing mass timber structural grid for functional adaptability,” in World Conference on Timber Engineering (WCTE 2025), Brisbane, Australia, 55–63. doi:10.52202/080513-0007

Hasani, N., Hosseini, A., Ashjazadeh, Y., Diederichs, V., Ghotb, S., Riggio, M., et al. (2025b). Outlook on human-centred design in industry 5.0: towards mass customisation, personalisation, co-creation, and Co-Production. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 18, 2486343. doi:10.1080/19397038.2025.2486343

hsbcad (2025). Hsbcad: flexible offsite timber construction software. Available online at: https://www.hsbcad.com/(Accessed July 31, 2025).

Hudiburg, T. W., Law, B. E., Moomaw, W. R., Harmon, M. E., and Stenzel, J. E. (2019). Meeting GHG reduction targets requires accounting for all forest sector emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 095005. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab28bb

Ilozor, B. D., and Kelly, D. J. (2012). Building information modeling and integrated project delivery in the commercial construction industry: a conceptual study. J. Eng. Proj. Prod. Manag. 2, 23–36. doi:10.32738/JEPPM.201201.0004

Israelsson, N. (2009). Factors influencing flexibility in buildings. Struct. Surv. 27, 138–147. doi:10.1108/02630800910956461

Jansson, G., Mukkavaara, J., and Olofsson, T. (2018). “Interactive visualization for information flow in production chains: Case study industrialised house-building,” in Proceedings of the 35th international symposium on automation and robotics in construction (ISARC). Editor J. Teizer (Taipei, Taiwan: International Association for Automation and Robotics in Construction), 382–388. doi:10.22260/ISARC2018/0054

Jin, T., Mak, B., and Zhou, P. (2012). Confidence scoring of speaking performance: how does fuzziness become exact? Lang. Test. 29, 43–65. doi:10.1177/0265532211404383

Jockwer, R., Goto, Y., Scharn, E., and Crona, K. (2020). Design for adaption – making timber buildings ready for circular use and extended service life. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 588, 052025. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/588/5/052025

Kamara, J. M., Heidrich, O., Tafaro, V. E., Maltese, S., Dejaco, M. C., and Re Cecconi, F. (2020). Change factors and the adaptability of buildings. Sustainability 12, 12. doi:10.3390/su12166585

Kamwa, E. (2022). Scoring rules, ballot truncation, and the truncation paradox. Public Choice 192, 79–97. doi:10.1007/s11127-022-00972-8

Koppelhuber, J., Schlagbauer, D., and Heck, D. (2015). “Cost calculation in prefabricated timber construction: process analysis on site and applicability for future projects,” in Proceedings of international structural engineering and construction, 2. doi:10.14455/ISEC.res.2015.183

Kortenko, S., Koskela, L., Tzortzopoulos, P., and Haghsheno, S. (2020). “Negative effects of design-bid-build procurement on construction projects,” in 28th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC), Berkeley, CA, 733–744. doi:10.24928/2020/0141

Kremer, P. D., Wakefield, R., Ahankoob, A., and Abbasnejad, B. (2025a). Global stakeholder perceptions of circular building adaptability, open building methodology and mass timber construction: a qualitative study. CIB Conf. 1, 297. doi:10.7771/3067-4883.1762

Kremer, P. D., Abbasnejad, B., Ahankoob, A., and Wakefield, R. (2025b). Advancing global mass timber construction - a decade of progress, challenges and future directions: a systematic literature review. Build. Environ. 284, 113458. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2025.113458

Kronenburg, R. (2007). Flexible: architecture that responds to change. 1st ed. London: Laurence King Publishers.

Lam, E. (2019). Mass timber primer. Can. Archit. Available online at: https://www.canadianarchitect.com/mass-timber-primer/ (Accessed August 7, 2025).

Langergraber, G., Pucher, B., Simperler, L., Kisser, J., Katsou, E., Buehler, D., et al. (2020). Implementing nature-based solutions for creating a resourceful circular city. Blue-Green Syst. 2, 173–185. doi:10.2166/bgs.2020.933

Langston, C., and Zhang, W. (2021). DfMA: towards an integrated strategy for a more productive and sustainable construction industry in Australia. Sustainability 13, 9219. doi:10.3390/su13169219

Lavikka, R., Kallio, J., Casey, T., and Airaksinen, M. (2018). Digital disruption of the AEC industry: technology-oriented scenarios for possible future development paths. Constr. Manag. Econ. 36, 635–650. doi:10.1080/01446193.2018.1476729

Lippke, B., Puettmann, M., Oneil, E., and Dearing Oliver, C. (2021). The plant a trillion trees campaign to reduce global warming – fleshing out the concept. J. Sustain. For. 40, 1–31. doi:10.1080/10549811.2021.1894951

Liu, Z. (2024). Comparison and analysis of advantages and disadvantages between BIM and CAD in civil drafting software. Appl. Comput. Eng. 62, 192–197. doi:10.54254/2755-2721/62/20240426

Lombardi, A. (2023). “Interoperability challenges. Exploring trends, patterns, practices and possible futures for enhanced collaboration and efficiency in the AEC industry,” in Coding architecture. Editor P. Ruttico (Springer), 49–72. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-47913-7_3

Magdziak, M. (2019). Flexibility and adaptability of the living space to the changing needs of residents. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater Sci. Eng. 471, 07211. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/471/7/072011

Malakouti, M., Faizi, M., Hosseini, S. B., and Norouzian-Maleki, S. (2019). Evaluation of flexibility components for improving housing quality using fuzzy TOPSIS method. J. Build. Eng. 22, 154–160. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2018.11.019

Mlote, D. S., Budig, M., and Cheah, L. (2024). Adaptability of buildings: a systematic review of current research. Front. Built Environ. 10, 10. doi:10.3389/fbuil.2024.1376759

Moehle, J. P., Ghodsi, T., Hooper, J. D., Fields, D. C., and Gedhada, R. (2012). NEHRP seismic design technical brief no. 6: seismic design of cast-in-place concrete special structural walls and coupling beams – a guide for practicing engineers. Gaithersburg, MD, 32. Available online at: https://www.nehrp.gov/pdf/nistgcr11-917-11.pdf (Accessed August 8, 2025).

Mostavi, E., Asadi, S., and Boussaa, D. (2017). Development of a new methodology to optimize building life cycle cost, environmental impacts, and occupant satisfaction. Energy 121, 606–615. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2017.01.049

National Institute of Standards and Technology (2021). Voluntary product standard PS 20-20 revision 1: american softwood lumber standard.

Ng, M. S., Graser, K., and Hall, D. M. (2023). Digital fabrication, BIM and early contractor involvement in design in construction projects: a comparative case study. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 19, 39–55. doi:10.1080/17452007.2021.1956417

Öberg, V., Jockwer, R., and Goto, Y. (2024). Design for structural adaptation in timber buildings: industry perspectives and implementation roadmap for Sweden and Australia. J. Build. Eng. 98, 111413. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2024.111413

Öberg, V., Jockwer, R., Goto, Y., and Al-Emrani, M. (2025). Design for structural adaptation: economic feasibility of an implementation for Swedish timber buildings. Build. Res. and Inf. 23, 759–776. doi:10.1080/09613218.2025.2478063

Ogundare, E., and Tokunbo, T. (2025). Evaluating the role of integrated project delivery (IPD) in facilitating change management in construction projects. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 9. doi:10.5281/zenodo.14610423

Orozco, L., Svatoš-Ražnjević, H., Wagner, H. J., Abdelaal, M., Amtsberg, F., Weiskopf, D., et al. (2023). Advanced timber construction industry: a quantitative review of 646 global design and construction stakeholders. Buildings 13, 2287. doi:10.3390/buildings13092287

Ottenhaus, L. M., Yan, Z., Brandner, R., Leardini, P., Fink, G., and Jockwer, R. (2023). Design for adaptability, disassembly and reuse – a review of reversible timber connection systems. Constr. Build. Mater 400, 132823. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132823

Owen, R. (2019). CIB white paper on IDDS: integrated design and delivery solutions. Available online at: https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/el/IDDS_White_Paper-1owen2.pdf (Accessed August 24, 2025).

Pearlmutter, D., Theochari, D., Nehls, T., Pinho, P., Piro, P., Korolova, A., et al. (2020). Enhancing the circular economy with nature-based solutions in the built urban environment: green building materials, systems and sites. Blue-Green Syst. 2, 46–72. doi:10.2166/bgs.2019.928

Pinder, J. A., Schmidt, R., Austin, S. A., Gibb, A., and Saker, J. (2017). What is meant by adaptability in buildings? Facilities 35, 2–20. doi:10.1108/F-07-2015-0053

Puettmann, M., Pierobon, F., Ganguly, I., Gu, H., Chen, C., Liang, S., et al. (2021). Comparative LCAs of conventional and mass timber buildings in regions with potential for mass timber penetration. Sustainability 13, 13987. doi:10.3390/su132413987

Qualtrics International Inc (2024). Qualtrics survey platform. Available online at: https://www.qualtrics.com/ (Accessed August 24, 2025).

Rashidian, S., Drogemuller, R., and Omrani, S. (2024). An integrated building information modelling, integrated project delivery and lean construction maturity model. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 20, 1454–1470. doi:10.1080/17452007.2024.2383718