- 1Department of Architecture and Building Sciences, College of Architecture and Planning, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 2Department of Architectural Engineering, College of Engineering, University of Hail, Hail, Saudi Arabia

Introduction: Riyadh’s modern architecture from the 1970s–1980s, produced during the post-oil transformation, remains critically underrepresented within Saudi heritage narratives, which primarily emphasize either pre-modern vernacular structures or contemporary iconic developments. This study addresses a conceptual and methodological gap in heritage documentation by proposing a framework that interprets modern architecture as an evolving narrative of cultural memory and urban identity rather than a stylistic category.

Methods: The research develops and applies a hybrid documentation model integrating urban morphology analysis, semantic mapping, and participatory narrative documentation. This interpretive system draws on community workshops, semi-structured interviews (n = 12), on-site observations, and archival materials to examine four case studies in Riyadh: two governmental, one institutional, and one hospitality. Data were analyzed through open and axial coding, forming semantic clusters that linked spatial form with cultural meaning.

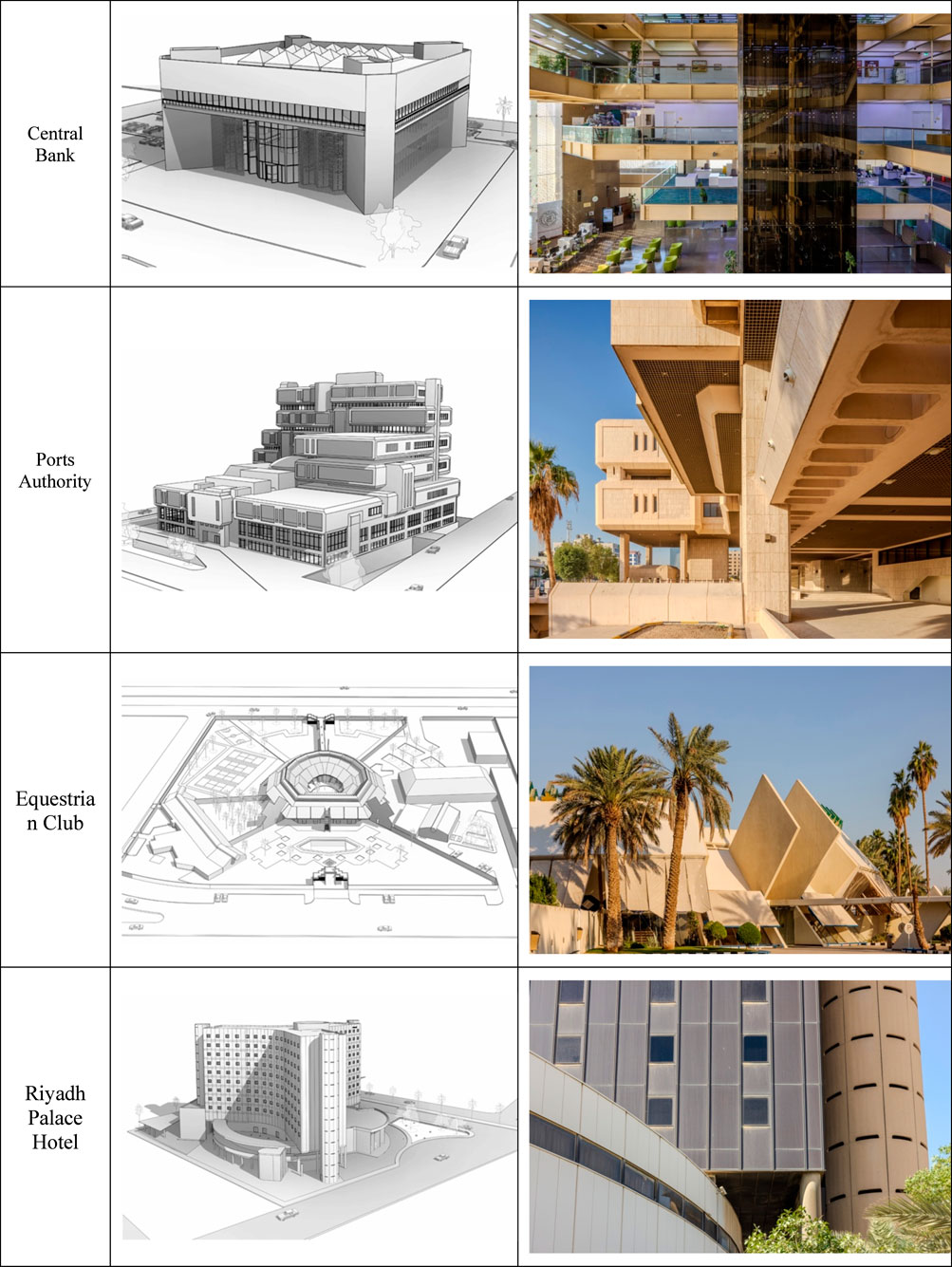

Results: The findings reveal that Riyadh’s modern architecture embodies negotiated identities that mediate between localized tradition and global modernity. The Saudi Central Bank and Ports Authority express institutional power and bureaucratic control; the Equestrian Club and the Riyadh Palace Hotel illustrate civic participation, openness, and aspirational modernity. Semantic mapping and narrative inquiry exposed how users’ memories and symbolic associations transform these buildings from static artifacts into cultural texts embedded within the collective urban consciousness.

Discussion: The hybrid documentation model extends existing integrative frameworks by operationalizing them through participatory and interpretive tools that connect lived experience with spatial analysis. It demonstrates that documentation can function as both method and theory, an act of cultural mediation that merges the tangible and the intangible. The model offers a replicable, low-cost, and contextually sensitive framework adaptable to other rapidly urbanizing, non-Western settings.

1 Introduction

Riyadh’s urban landscape has undergone rapid transformation over the last half century, leaving the city’s modernist architectural layer emerging during the post-oil boom decades of the 1970s and 1980s largely overlooked within national heritage narratives. These structures, which embody the ambitions of modernization, state-building, and cultural negotiation, represent a critical yet fragile dimension of Saudi identity (Moscatelli and Nankov, 2022). Their neglect is not merely material but conceptual, reflecting a gap in how heritage is defined, valued, and remembered. Conventional preservation frameworks in Saudi Arabia have traditionally privileged pre-modern vernacular or monumental heritage, while contemporary urban policy has tended to celebrate futuristic landmarks (Alnaim, 2024). As a result, modernist buildings that once symbolized progress now occupy an ambiguous space between relevance and obsolescence, at risk of physical erasure and cultural forgetting. Addressing this gap requires a documentation paradigm that can capture not only the architectural form but also the cultural meanings, narratives, and memories that sustain these spaces as living components of urban identity.

This research responds to a methodological gap in architectural heritage documentation, particularly within non-Western contexts, where conventional emphasis on tangible features often overlooks embodied meanings, lived experiences, and community memory (Alsheliby, 2015). Traditional approaches tend to prioritize formal and stylistic attributes, detaching buildings from their socio-cultural settings and failing to capture the dynamic interplay between people and place (Al-Zaidi and Khalil, 2023). This study contends that meaningful documentation must account for how architecture is perceived, used, and remembered, an effort requiring integrative and narrative-sensitive methods.

In the Saudi context, where modern architecture occupies an ambiguous position between cultural pride and perceived transience, narrative and semantic mapping offer a theoretically grounded means to reconnect built form with lived experience. Narrative inquiry foregrounds how architectural spaces mediate collective memory, allowing modernist structures to be interpreted not solely through style or function but through the stories that sustain their cultural relevance. Semantic mapping complements this by translating intangible associations such as symbolism, hierarchy, and affect into spatially legible formats. Together, these approaches enable an understanding of modern heritage as an evolving construct of cultural memory and identity, bridging the disjunction between material preservation and social meaning. This conceptual orientation situates the study within broader theoretical debates on memory studies, identity formation, and participatory heritage documentation.

Building on this conceptual foundation, the study proposes a participatory framework that integrates semantic mapping, narrative theory, and digital storytelling. Rather than treating these as procedural tools, the model positions them as interpretive lenses through which architectural identity is understood as a function of cultural memory. This theoretical grounding provides the basis for the study’s three guiding questions: (1) How can narrative and participatory methods reinterpret modern architectural heritage as cultural memory rather than stylistic record? (2) In what ways do existing documentation models fail to capture the socio-symbolic dimensions of non-Western modernism? (3) How can a hybrid documentation model translate these insights into responsive heritage policy and architectural pedagogy?

By positioning documentation within the discourse of cultural memory and urban identity, this study aims to advance a more nuanced, inclusive, and living understanding of modern heritage, one that transcends physical preservation to embrace the continually evolving stories embedded in Riyadh’s urban landscape. Thus, the originality of this study lies in conceptualizing documentation as both a methodological process and a theoretical lens. The hybrid model departs from conventional integrative frameworks by synthesizing narrative inquiry and semantic mapping within an interpretive framework of cultural memory. Rather than treating storytelling as supplementary to technical documentation, the model positions narrative as the analytical bridge linking spatial form, social meaning, and urban identity. This approach not only contributes a novel theoretical articulation of modern heritage in Saudi Arabia but also establishes structural coherence across the paper, as each section from literature review to discussion tracing how narrative, memory, and spatial documentation converge within a unified analytical framework.

2 Literature review

To understand the key issues related to modern architectural heritage, this literature review explores a topic that has historically been underrepresented in heritage studies. The discussion is organized around three main themes. First, it considers the current context of modern heritage. With rapid urban transformations worldwide, particularly in postcolonial cities - understanding how modern architecture is preserved and valued is increasingly essential. This section examines existing documentation approaches, their challenges, and emerging frameworks, with a focus on contexts like Saudi Arabia, where modern heritage faces unique recognition barriers.

Second, the review addresses recent global shifts toward more inclusive documentation practices that emphasize the integration of social, cultural, and intangible values. Despite this progress, modern architecture often remains marginalized within heritage studies. Narrative theory is introduced as a valuable perspective for understanding architecture as a vessel of collective memory and cultural identity. Theories in this area highlight how buildings embody lived experiences and historical continuity, and how neglecting modern structures risks disrupting cultural memory.

Third, building on this, the review explores global trends in incorporating innovative digital and participatory methods into heritage documentation. While these approaches are advancing internationally, they remain limited in the Arab world, particularly in Saudi Arabia.

2.1 Rethinking the documentation of modern heritage: gaps and shifts

The documentation of modern architectural heritage has historically occupied a contested space in both academic and policy domains. While heritage frameworks have long focused on pre-modern, monumental, or stylistically “complete” structures, the modernist legacy - particularly in postcolonial and rapidly transforming urban contexts remains underrepresented and conceptually ambiguous (Chen et al., 2023). Riyadh’s modern heritage, emerging from the accelerated development following the oil boom of the 1970s and 1980s, is emblematic of this dilemma: it is historically significant, yet largely undocumented or unrecognized by formal heritage systems (Al-Naim, 2008).

Globally, documentation practices have gradually shifted from object-based inventory systems toward more inclusive models that consider social value, setting, and meaning. The Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach by UNESCO (2011) and Rey-Pérez and Pereira Roders (2020) is a prime example, advocating for integrated, multilayered urban documentation that considers tangible and intangible dimensions alike. Yet, the operationalization of such frameworks often remains partial, especially in the context of modern architecture. As observed modernist structures are often overlooked due to their perceived aesthetic ambiguity, unresolved stylistic evolution, or association with contested political ideologies (Aas et al., 2005; Avrami et al., 2019).

In Saudi Arabia, documentation efforts have traditionally focused on vernacular or Islamic heritage, often sidelining modernist architecture as temporally “too recent” or ideologically “too foreign.” Despite growing initiatives such as the Saudi Heritage Commission’s pilot inventory projects and the urban revitalization of Diriyah and Jeddah - there remains no established methodology for documenting modern architectural layers that integrate both technical accuracy and cultural meaning. This lacuna underscores the need for a hybrid documentation model that situates modern buildings within the wider narrative of urban identity and collective memory.

2.2 From structure to story: narrative theory and cultural memory in the built environment

Narrative theory offers a powerful lens through which architecture can be understood not merely as form, but as a medium of cultural expression and historical continuity. As Ricoeur and Ricoeur (1984) asserts, narrative structures human experience in time, shaping how events—and by extension, environments are remembered and interpreted. In architecture, this implies that buildings and urban spaces are not static artifacts, but repositories of collective stories, identity, and transformation.

Kevin Lynch’s seminal work The Image of the City (1960) (Lynch, 2020) introduced the concept of mental mapping, emphasizing how users interpret and internalize urban form. Later theorists, such as Hayden (1995), expanded this idea by foregrounding gender, memory, and socio-spatial justice in urban documentation. Hayden’s notion of the “power of place” exemplifies how memory-based documentation can make visible the cultural narratives embedded in everyday urban environments.

Assmann (2010) differentiation between communicative and cultural memory also offers valuable insight. While communicative memory exists within living generations, cultural memory is institutionalized through media, symbols, and monuments - of which architecture is a prime medium. Therefore, when modern buildings are demolished or left undocumented, a rupture occurs not only in the physical landscape, but also in the cultural continuum of memory transmission (Apaydin, 2020).

Applied to Riyadh, this theoretical framework reveals a critical blind spot. While older heritage sites are increasingly being preserved and curated, the modernist architectural layers that shaped Riyadh’s institutional, civic, and hospitality sectors during its state-building era remain largely absent from both academic research and public discourse (Alghamdi et al., 2024). This absence contributes to a collective forgetting - undermining the potential of modern heritage to serve as a cultural bridge between tradition and modernity.

Yet, this notion of a “bridge” warrants critical unpacking. In the Saudi context, both “tradition” and “modernity” are not fixed or monolithic categories but negotiated constructs shaped by state narratives, professional discourse, and global architectural exchange. Tradition often functions as a symbolic framework selectively mobilized to assert cultural authenticity, while modernity is framed through the lens of development, institutional expansion, and international visibility. The modern buildings examined here thus do not reconcile two stable poles; rather, they materialize an evolving dialogue in which cultural identity is continuously redefined through design practice and political aspiration.

2.3 Comparative documentation practices: global case studies and digital innovation

Internationally, various cities have attempted to confront the challenges of documenting modern heritage through innovative frameworks and digital platforms. In Singapore, the Living Archive of Modern Urbanism integrates GIS-based urban data with citizen-submitted narratives, allowing for a layered interpretation of modernist housing estates (Putra and Yang, 2005). The archive merges the technical with the experiential, acknowledging that architectural value cannot be reduced to material attributes alone (Phillips, 2005).

In Latin America, Brazil’s Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi (Camacho, 2022) has preserved modernist works through a combination of archival curation and oral history, particularly highlighting the interplay between architecture, politics, and social aspiration in post-war São Paulo. In parallel, Johannesburg’s Re-Mapping Soweto project uses digital mapping and story annotation to capture how apartheid-era infrastructure continues to shape memory and identity in the city’s contemporary fabric (Mkhabela, 2023).

In the Arab world, efforts remain fragmented but are gaining momentum. Docomomo Morocco has launched a series of initiatives to catalog Casablanca’s post-independence architecture (van den Heuvel et al., 2008), while Lebanon’s Beirut Urban Lab integrates conflict, memory, and reconstruction narratives into urban documentation (Sadler and Sadler, 2025). In Dubai, the Modern Heritage Initiative (launched by Dubai Culture in 2020) has started to identify, tag, and assess mid-20th-century structures using stylistic and locational criteria (Alsuwaidi et al., 2021). However, such programs still rarely integrate end-user perspectives or employ participatory storytelling tools in a systematic way.

Saudi Arabia has yet to see a national-level effort that systematically documents modern architecture using digital, narrative, or user-based tools. Most existing documentation remains institutional (e.g., architectural records in government ministries) (Alghamdi et al., 2023) or aesthetic (photographic surveys), lacking semantic or experiential depth. This contrasts with the availability of high-potential digital tools such as 3D scanning, VR-based walkthroughs, and oral history mapping platforms, which remain underutilized in the heritage sector.

Recent scholarship further underscores the relevance of integrating technological, aesthetic, and socio-cultural perspectives into modern heritage documentation. Studies such as Nia and Rahbarianyazd (2020) provide analytical grounding for understanding how form and meaning operate as intertwined systems of architectural communication, resonating with the semantic dimension of this study. Likewise, the review Song and Selim (2022) highlights the potential of digital integration and participatory data environments to enhance heritage accessibility and sustainability, principles echoed in the proposed hybrid model. Regionally, adopting GIS to enhance the urban cultural heritage in Alexandrian, Egypt (Othman et al., 2025) demonstrates how geospatial tools can contextualize cultural memory in urban documentation, offering methodological parallels for Saudi Arabia. Finally, the dynamics of heritagization in urban regeneration (Hanif and Riza, 2025) situates heritage within broader geopolitical and cultural frameworks, reinforcing this study’s argument that modern architecture must be interpreted as a dynamic negotiation between global and local narratives. Despite these advances, contemporary participatory frameworks continue to face challenges of representation, as the narratives incorporated into heritage records often reflect existing hierarchies of expertise, gender, and institutional authority.

2.4 Toward a hybrid documentation model: theoretical integration and research contribution

The reviewed literature and case studies highlight four principal shortcomings in prevailing documentation models: (1) An overemphasis on the tangible: Existing practices focus predominantly on physical attributes ignoring how architecture is experienced, remembered, and interpreted. (2) A limited integration of user narrative: Stakeholder and public perspectives are often absent, despite their centrality to meaning-making and cultural continuity. (3) Insufficient application of digital storytelling: While digital tools have advanced significantly, their integration with participatory frameworks remains underdeveloped, especially in the Arab region. (4) Inflexibility across spatial typologies: Documentation systems often fail to adapt across governmental, institutional, and commercial/hospitality contexts, limiting their transferability.

This study addresses these gaps by proposing a hybrid, narrative-based, and technologically enabled model of documentation. The model is tested through three typologically diverse zones in Riyadh, selected for their historical value and spatial complexity. Each zone becomes a lens through which semantic mapping, stakeholder memory, and spatial morphology are integrated into a cohesive documentation framework. The resulting methodology is not only contextually grounded, but also scalable and transferable contributing a new approach to how modern heritage can be preserved, interpreted, and leveraged as a resource for cultural identity and planning.

While integrative documentation frameworks such as UNESCO’s Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach (Ginzarly et al., 2019; Avrami et al., 2019) values-based management, and (Guven Ulusoy, 2023) integrated tangible–intangible models emphasize the coexistence of physical and cultural layers, the hybrid model introduced here advances the discussion by operationalizing these principles through a participatory, narrative-centered methodology. Its theoretical novelty lies in repositioning documentation not merely as an analytical record but as a dialogic process that foregrounds community memory, spatial semantics, and experiential storytelling as coequal to material evidence. This shift from integration to interpretation transforms the role of documentation from passive inventory to active cultural mediation. Furthermore, unlike HUL and comparable global frameworks that rely heavily on institutional implementation, the proposed model is designed for adaptability in low-resource contexts, prioritizing accessibility, inclusivity, and cultural specificity within non-Western urban environments.

3 Methodology

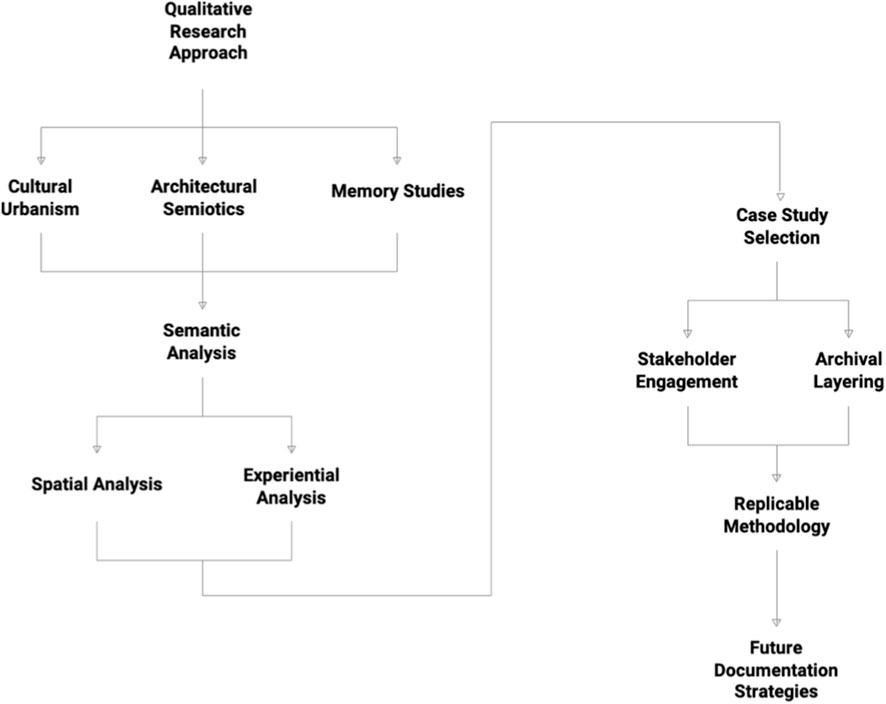

This study adopts a qualitative and interpretive research approach grounded in the belief that architecture should be understood not only as a physical artifact, but also as a carrier of meaning, memory, and cultural identity. The aim is to create a documentation framework that can be applied in resource-limited contexts without dependence on advanced technology or specialist software, making it accessible to heritage professionals, students, and community members alike (Figure 1).

The research design is comparative and multi-scalar, examining four selected buildings in Riyadh that differ in function, typology, and symbolic role: two governmental, one institutional, and one hospitality. Each case is treated as an entry point into a larger narrative of Riyadh’s post-1970s urban transformation. Key principles of comprehensive modern heritage documentation include the following:

• Integration of Tangible and Intangible Dimensions: Documentation goes beyond recording architectural form; it includes the stories, perceptions, and meanings that give spaces cultural significance (Guven Ulusoy, 2023).

• Accessibility of Methods: All documentation processes use readily available tools printed plans, hand sketches, notebooks, cameras, and community workshops, ensuring replicability without costly technology.

• Participatory Engagement: The approach values the contributions of those who know the buildings best former and current users, local residents, and professionals involved in their design or management.

• Comparative Perspective: Findings are not treated in isolation. Instead, the study cross-references similarities and contrasts between the four cases to identify broader patterns in Riyadh’s modern heritage (Harrison et al., 2020).

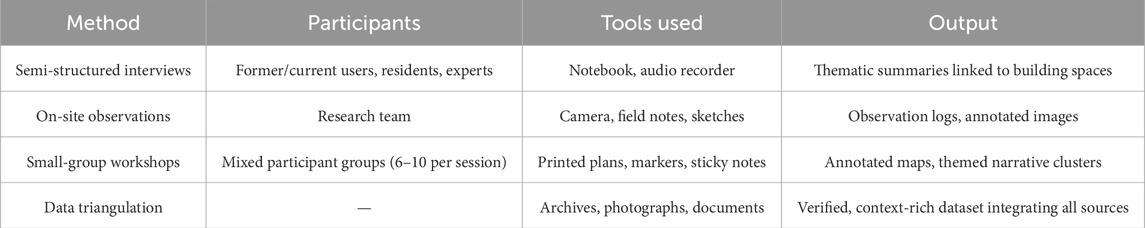

This design ensures that each case study is explored from multiple angles: physical, cultural, and experiential so that the outputs can directly support conservation, policy-making, and public engagement (Table 1). To enhance methodological transparency, the study explicitly details the interrelation among its three applied tools urban morphology analysis, semantic mapping, and narrative documentation, by presenting clear operational steps and triangulated outputs. Each method contributes distinct yet complementary data layers that collectively shape the hybrid documentation framework. Furthermore, analytical synthesis across the four case studies was achieved through iterative comparison, ensuring that the semantic, spatial, and cultural findings were cross-referenced rather than treated as isolated case observations. In parallel, the research critically situates its model within global discourses on inclusive and digital heritage documentation by acknowledging current debates around participatory mapping, data democratization, and the ethics of digital storytelling. This positioning highlights the study’s dual commitment to methodological clarity and global scholarly engagement. The result is a practical, inclusive, and adaptable documentation model that responds to the study’s overarching aim: preserving modern heritage as both a physical record and a living narrative.

3.1 Tools, frameworks, and analytical methods

The hybrid documentation model developed in this study is designed to be accessible, replicable, and adaptable to different urban contexts without requiring advanced or proprietary software. The approach integrates three interrelated methods urban morphology analysis, semantic mapping, and narrative documentation, to capture both the tangible and intangible dimensions of modern architectural heritage.

Thus, to consolidate the methodological logic and demonstrate the continuity between analytical processes and applied outcomes, a schematic conceptual framework was developed. Figure 2 visualizes the hybrid documentation model as a three-tier system linking methods, data types, and resulting applications. At the first tier, the model integrates three primary methods, urban morphology analysis, semantic mapping, and narrative documentation—each producing corresponding data layers (spatial, semantic, and narrative). The second tier illustrates the synthesis process, in which these layers interact to generate interpretive insights on cultural meaning, identity, and spatial behavior. The final tier connects these insights to practical outcomes: policy formulation (heritage classification, participatory governance), educational integration (curriculum reform, digital literacy), and design adaptation (adaptive reuse, inclusive urban planning). This schematic encapsulates the hybrid model’s capacity to translate documentation into strategic cultural and educational action.

Figure 2. Conceptual framework illustrating the hybrid documentation model linking methods, data types, and outcome applications.

3.1.1 Urban morphology analysis

Urban morphology analysis in this study focuses on understanding the physical structure, form, and spatial relationships of each case study (Pinho and Oliveira, 2009). Instead of relying on advanced GIS systems, the process draws on:

• On-site observation to record building footprints, height, orientation, and relationship to streets and open spaces.

• Rivet drawings and scaled tracing overlays Annotated digital plans and images using illustrative platforms to identify building form, massing, and urban grain.

• Archival material review (old photographs, planning documents, or newspaper images).

The qualitative and participatory orientation of this study is grounded in interpretivist theory, which assumes that architectural meaning is co-constructed through lived experience rather than objectively measurable form. Accordingly, the selected tools, urban morphology analysis, semantic mapping, and narrative documentation, serve not as procedural conveniences but as epistemological instruments that translate social memory and perception into analyzable spatial data. This approach aligns with hermeneutic and phenomenological traditions in architecture, where meaning emerges through human interaction with the built environment. By situating data collection within this interpretive paradigm, the methodology explicitly prioritizes understanding over quantification, aligning the research process with its cultural and narrative objectives. Thus, the study aim to create a morphological baseline for each case, providing the physical framework on which narratives and meanings can be layered.

3.1.2 Semantic mapping

Semantic mapping here is simplified into a manual, workshop-friendly process that records how spaces are perceived, used, and remembered by their communities (Costamagna et al., 2012). The process involves:

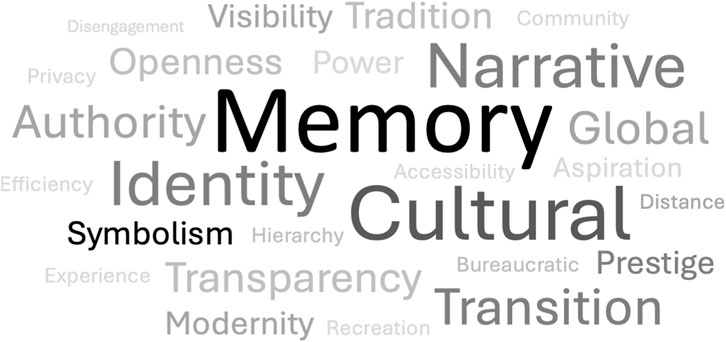

• Keyword collection from interviews and group discussions (e.g., “authority,” “openness,” “prestige,” “tradition”).

• Paper-based mapping exercises where participants annotate printed plans or photographs, marking locations linked to specific memories or meanings.

• Thematic grouping of terms and stories to identify dominant spatial meanings and recurring cultural associations.

These mappings help visualize non-physical attributes such as symbolic roles, emotional connections, and social hierarchies that are otherwise invisible in traditional architectural surveys.

3.1.3 Narrative documentation

Narrative documentation captures personal and collective stories connected to each building. This method does not require video production or complex archiving platforms (Patias, 2006); instead, it focuses on recording and organizing testimonies in a structured way (Table 2).

• Semi-structured interviews with former and current users, designers, and local residents.

• Short written accounts that summarize each participant’s key memories and perceptions, linked to specific building spaces.

• Simple image-caption pairing: combining photographs with short narratives to create a visually accessible record.

The goal is to produce a human-centered architectural record, integrating the lived experience into the formal documentation.

These three methods are applied in sequence, but remain interconnected:

1. Morphological analysis establishes the physical framework.

2. Semantic mapping overlays intangible meanings onto this framework.

3. Narrative documentation enriches both layers with detailed human experiences.

Each method directly corresponds to one of the study’s three overarching objectives: urban morphology analysis addresses the documentation of physical form and typological transformation; semantic mapping captures the social and symbolic dimensions of architectural space; and narrative documentation engages with memory and identity formation. The integration of these layers through comparative synthesis fulfills the study’s central aim, to demonstrate how hybrid documentation can reveal the multidimensional character of modern heritage.

3.2 Participatory engagement and data collection

Engaging directly with people connected to each building is central to the hybrid documentation model. This approach values the perspectives of those who have worked in, visited, or lived near the sites, as their memories and observations provide a vital layer of meaning that purely physical surveys cannot capture. The participatory process is designed to be low-cost, low-technology, and easy to replicate, making it applicable in varied heritage contexts.

As a result, participant selection followed a purposive sampling strategy aimed at capturing a balanced spectrum of perspectives across user, professional, and community categories. The final sample included architects and planners involved in the buildings’ original design or management, former and current users representing different institutional hierarchies, and local resident’s familiar with the sites’ social roles. Selection prioritized knowledge relevance over representational quantity to ensure depth of insight within a manageable dataset. Nevertheless, the process was constrained by institutional accessibility and gender representation, female participants, for example, were fewer due to restricted access to certain government facilities. These limitations are acknowledged as factors influencing the breadth of perspectives but not the interpretive validity of the findings, as triangulation and iterative verification were employed to maintain analytical reliability.

3.2.1 Semi-structured interviews (n = 12)

Interviews are a core source of narrative and interpretive material. They are designed to be flexible, allowing participants to speak freely while ensuring that key topics are covered.

• Participants include former employees, current users, local residents, architects, planners, and heritage officers.

• Format: Conducted in-person or remotely, typically lasting 30–45 min.

• Core questions explore:

○ Personal memories of the building and surrounding area.

○ Perceived symbolic meaning of the building.

○ Changes in appearance, use, and reputation over time.

• Recording: Audio or written notes, depending on participant comfort.

• Output: Short thematic summaries linked to specific locations or features of the building.

3.2.2 Small-group workshops (n = 4)

Workshops allow for collaborative mapping and storytelling. They are held in a neutral or familiar setting (community hall, café, or small meeting space) to encourage open discussion.

• Format:

○ Display printed floor plans and photographs.

○ Ask participants to mark locations associated with memories, meanings, or significant events.

○ Use colored markers or sticky notes to differentiate themes (e.g., social events, institutional routines, spatial changes).

• Value:

○ Encourages shared recollection, as one person’s memory often prompts another’s.

○ Produces a visual record that merges personal narrative with spatial representation.

• Output:

○ Annotated maps, thematic clusters of stories, and participant feedback on how the building should be remembered.

3.2.3 On-site observations

Observation sessions help record how spaces are currently used and how people interact with the buildings and their surroundings.

• Frequency: Multiple visits at different times of day and week to capture variations in use.

• Focus Areas:

○ Movement patterns (entry, circulation, congregation).

○ Public-private boundaries and how they are negotiated.

○ Environmental conditions (light, shade, noise, temperature).

○ Maintenance levels and visible alterations over time.

• Recording Tools: Field notebooks, simple cameras, and hand sketches.

• Output: Observation logs, annotated photographs, and descriptive site notes.

Participants were selected through purposive sampling to ensure representation across user categories—former employees, residents, architects, planners, and heritage officials, each possessing distinct experiential relationships to the buildings studied. This sampling approach enhances validity by incorporating multiple vantage points that collectively reconstruct a more balanced cultural narrative. To mitigate interpretive bias, data collection and analysis were guided by reflexivity: the researcher maintained a field diary documenting assumptions and evolving interpretations, allowing critical self-assessment throughout the process. Reliability was further reinforced through triangulation, where interview, observation, and workshop data were cross verified to confirm thematic consistency across sources.

3.2.4 Data triangulation

To ensure accuracy and depth, the study cross-checks findings from interviews, observations, and workshops with archival materials (photographs, news articles, planning documents) (Table 3). This triangulation helps verify dates, confirm spatial changes, and contextualize personal narratives within a broader historical framework.

To ensure analytic rigor and interpretive transparency, the qualitative data were examined through a three-step coding and synthesis process. First, all interview transcripts and workshop notes were subjected to open coding to extract recurrent terms, spatial references, and emotional descriptors. These initial codes were then grouped into higher-order categories or “semantic clusters” reflecting shared cultural or spatial meanings (e.g., authority, openness, prestige, memory). Second, axial coding was used to link these clusters to specific spatial features identified during morphology analysis, thereby forming a cross-referenced semantic map that visually integrates narrative and spatial data (Williams and Moser, 2019). Third, intersubjectivity in mapping workshops was addressed through consensus validation: participants reviewed the emerging thematic maps collectively to refine or correct interpretations. This iterative feedback loop ensured that meanings were not imposed by the researcher but co-constructed among participants, enhancing the credibility and cultural authenticity of the final semantic outputs.

This participatory engagement strategy ensures that documentation moves beyond surface-level recording, capturing the emotional and cultural dimensions of architectural heritage in parallel with its physical attributes. It also reinforces the study’s broader aim: making heritage documentation a shared cultural activity rather than a purely technical exercise.

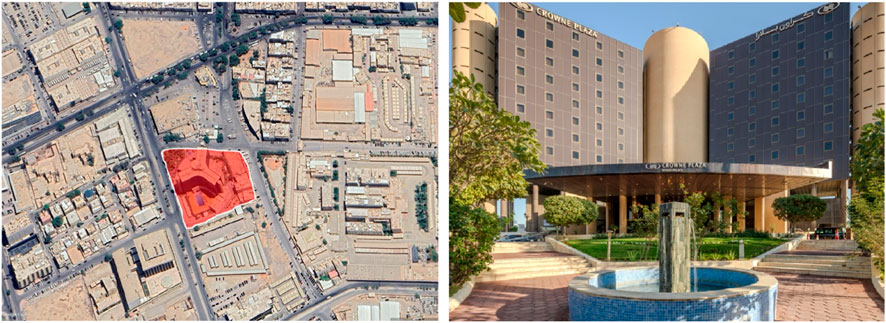

3.3 Case study selection

To assess the adaptability, cultural relevance, and methodological robustness of the proposed hybrid documentation model, this study applies it to four distinct architectural zones within Riyadh (Figure 3). These zones were selected based on three primary criteria:

1. Typological Diversity: covering governmental, institutional, and hospitality functions.

2. Historical Significance: all built during the critical post-oil boom decades (1970s–1980s) that shaped Riyadh’s modern urban identity.

3. Architectural Variety: representing a spectrum of stylistic expressions, structural systems, and spatial-semantic configurations.

Each case offers a distinct socio-spatial context in which to test the model’s ability to integrate semantic mapping, user memory, and digital documentation. The following summarizes the four case studies:

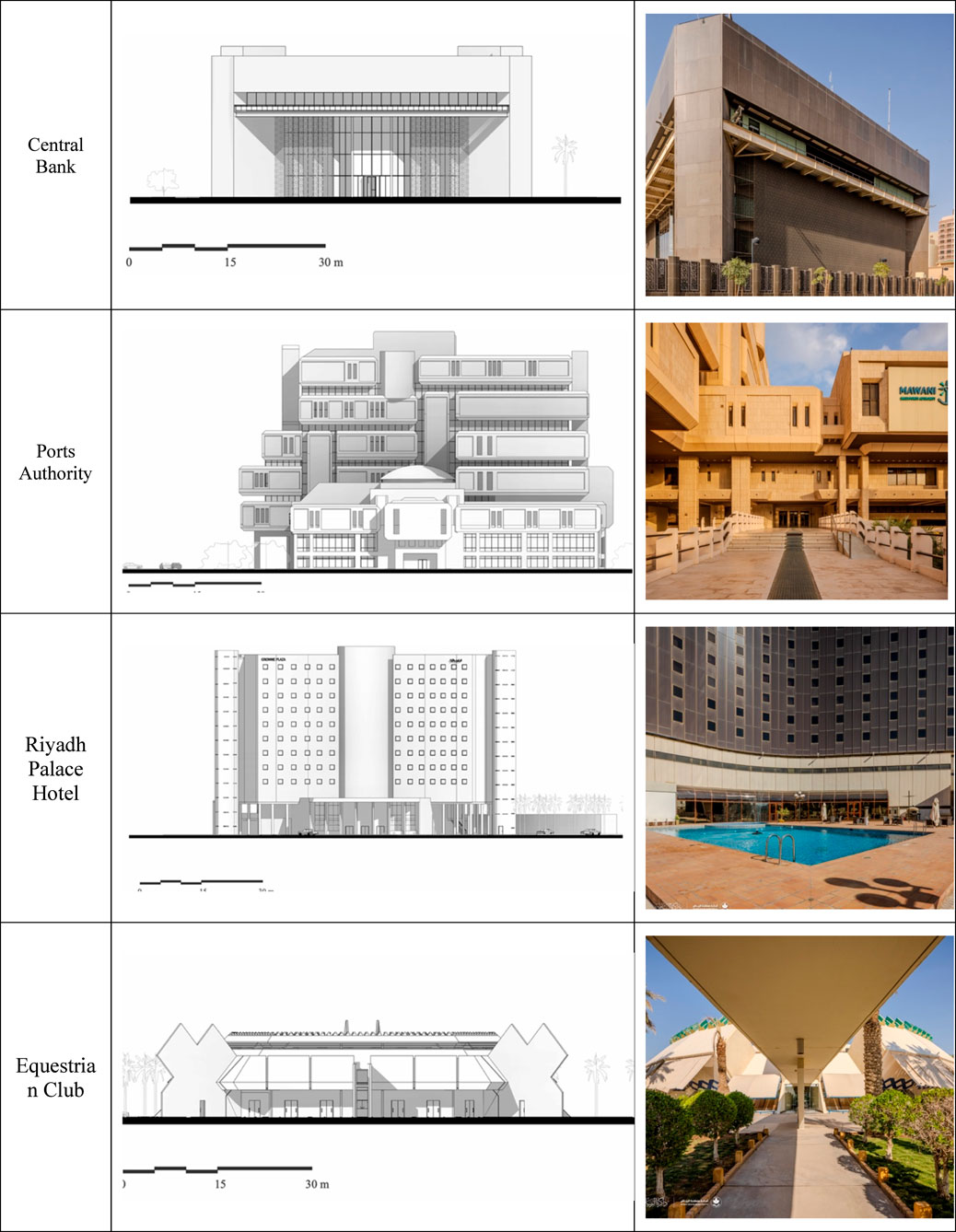

Case 1: Saudi Central Bank–Riyadh Office (Governmental)

• Architects: Brown Daltas & Associates

• Completed: 1986

• Location: King Faisal Road, Al-Fouta

• Design Highlights: High-tech Islamic modernism, chamfered-square geometry, suspended floors via steel cables, external metal rawashin.

• Relevance: A landmark of functional innovation and cultural symbolism, this building reflects the state’s institutional modernization and design ambition in the 1980s. The semantic richness lies in its reinterpretation of Islamic motifs through structural expressionism (Figure 4).

Case 2: Saudi Ports Authority (Governmental)

• Architect: Abdulrahman Al-Juniedi

• Completed: 1987

• Location: Prince Abdulrahman Bin Abdulaziz Street, Al-Murabba

• Design Highlights: Brutalist-inspired concrete massing, container-like modularity, absence of ornamentation, vertical emphasis via narrow fenestration.

• Relevance: This case reflects the bureaucratic infrastructure of the post-oil Saudi state, symbolizing stability, regulation, and functionality. It offers a semantic narrative around visual strength, abstraction, and institutional anonymity (Figure 5).

Case 3: Equestrian Club (Institutional)

• Architects: Frank Basil with Rader Mileto Associates

• Completed: 1978

• Location: Salah Ad Din Al-Ayyubi Road, Al-Malaz

• Design Highlights: Horseshoe geometry, tensioned canopies, integrated recreational zones, intersecting concrete planes, natural-light-driven central courtyard.

• Relevance: A unique civic-recreational institution rooted in cultural tradition, the building encodes royal patronage, local sports heritage, and innovative structural articulation. Its layered spatial organization supports semantic reading of hierarchy, openness, and symbolic form (Figure 6).

Case 4: Riyadh Palace Hotel–Now Crowne Plaza (Hospitality)

• Architect: Madame Guihot

• Completed: 1979

• Location: Prince Abdulrahman Bin Abdulaziz Street, Al-Murabba

• Design Highlights: Triadic armature, cylindrical staircase volumes, full glass façades, steel structure; early example of international hotel typology in Riyadh.

• Relevance: As the city’s first glass-and-steel high-rise, it signals the integration of global hospitality standards with local socio-political prestige. It also embodies a moment of cultural friction and aspiration, making it ripe for narrative and memory mapping (Figure 7).

4 Discussion

This section presents a comparative analysis of four modern architectural sites in Riyadh, each examined through the application of a hybrid documentation model that integrates semantic mapping, spatial analysis, and memory-based interpretation. To guide the interpretation of findings, the discussion is structured around three interrelated analytical dimensions derived from the study’s theoretical foundations: (1) semantic form, which examines how architectural expression conveys cultural meaning through morphology and symbolism; (2) experiential narrative, which considers how users and communities construct shared memory through interaction with space; and (3) cultural resonance, which evaluates how buildings mediate the dialogue between institutional identity and collective remembrance. These dimensions operationalize key concepts from narrative theory and cultural memory studies, particularly Ricoeur’s notion of temporal interpretation (Nankov, 2014) and Assmann’s differentiation between communicative and cultural memory (Assmann, 2011), allowing each case to be read not merely as an architectural artifact but as a narrative construct embedded in social experience. This framing establishes an interpretive hierarchy for the discussion: empirical description supports, rather than substitutes, theoretical argumentation.

The sites, two governmental, one institutional, and one hospitality serve as nodes for examining how modern architecture in Saudi Arabia performs as a medium for identity, memory, function, and urban negotiation. The analysis is structured thematically, emphasizing the synthesis of architectural form and narrative, spatial logic, symbolic language, and cultural relevance, without isolating each case study.

4.1 Semantic form and typological logic

The selected buildings illustrate divergent strategies in expressing institutional identity through architectural form. The Saudi Central Bank’s chamfered-square geometry, suspended floor slabs, and abstracted Islamic motifs offer a high-tech architectural response anchored in cultural symbolism. Its formal composition square core, peripheral concrete cores, and metal rawashin—reinterprets regional aesthetics through structural innovation, situating it within the global discourse of culturally informed modernism.

In contrast, the Saudi Ports Authority building employs an architectural vocabulary rooted in late-modern brutalism. Its modular repetition, concrete heaviness, and vertical slit windows express bureaucratic solidity and institutional opacity. The absence of ornamentation and reliance on raw materiality produce a visual language of functional authority and spatial disengagement. Unlike the Central Bank’s expressive formalism, these building renders itself nearly mute, a reflection of state authority materialized in mass and repetition (Figure 8).

From a semantic perspective, these formal distinctions reveal how architectural expression encodes social hierarchies and institutional ideologies. The contrast between the Central Bank’s articulated symbolism and the Ports Authority’s mute massing exemplifies what Umberto Eco describes as the semiological range of architecture, where form functions as a communicative system rather than a mere aesthetic choice. Within this framework, morphology becomes a language through which power, transparency, and civic identity are negotiated in space.

Meanwhile, the Equestrian Club adopts a formal language that abstracts movement, rhythm, and openness. The horseshoe-shaped plan, sloped concrete surfaces, and tensioned structural elements produce an architecture of continuity and transparency. Rather than articulating hierarchy through form, the club promotes accessibility and experiential flow, suggesting a civic architecture that accommodates both tradition and recreation.

The Riyadh Palace Hotel contrasts all previous cases by embracing international hospitality typologies. Its triadic, radial plan; cylindrical stair towers; and full-glass façades situate it in the lineage of global modernism (Figure 9). The building borrows from corporate modern architecture yet situates itself in Riyadh’s skyline as a symbol of aspiration and openness to global standards, serving as a physical testament to the city’s transformation into a regional capital.

4.2 Spatial organization and experiential architecture

The internal spatial structures of the case studies offer critical insights into the lived dimension of modern architecture (Figure 10). The Equestrian Club’s spatial sequencing from formal entrance to courtyard, sports facilities, and garden areas, demonstrates an environment built around interaction, layered privacy, and spatial fluidity. Its internal zones support both leisure and ritual, and the architecture fosters dynamic visual and physical relationships between indoor and outdoor elements.

In contrast, the Ports Authority’s interior is rigidly structured, offering minimal flexibility or intuitive circulation. Its vertical stratification, repetitive corridors, and uniform spatial modules produce a disorienting interior landscape. Despite the clarity of its structural grid, the building’s internal logic appears disengaged from its users’ sensory and emotional needs.

The Central Bank achieves a careful balance between openness and control. Its atrium-centered layout offers visual permeability while maintaining physical separation between public and administrative zones. The building creates a sense of hierarchical transparency, expressing access without granting it; thus aligning spatial logic with the institutional nature of its function.

The Riyadh Palace Hotel adopts a centralized vertical circulation core, from which guest room wings radiate. This layout facilitates user segmentation and programmatic zoning. Public areas such as restaurants, conference rooms, and lounges are clearly distinguished from private zones. The spatial logic emphasizes comfort, discretion, and spatial scripting, revealing how hospitality architecture curates’ movement and experience.

4.3 Cultural resonance and memory

Each building embeds and expresses different layers of cultural memory and social association. The Equestrian Club holds the richest repository of social narratives. As a space of both public ceremony and private memory, it encapsulates the transition of equestrian traditions into modern civic life. Its architecture is remembered not only for its form but for the events, rituals, and seasonal rhythms it hosted, transforming it into a living monument of cultural continuity.

The Riyadh Palace Hotel, while less culturally rooted, is perceived as a symbol of national prestige and global ambition. As one of the first high-rise glass buildings in Riyadh, it generated both admiration and debate. Its visual transparency and openness contrasted sharply with the architectural conservatism of the time. It served as an interface between domestic governance and international diplomacy, hosting dignitaries and events that shaped Riyadh’s public image.

The Central Bank, despite its reserved exterior and regulated spatial flow, evokes strong institutional memory. The building was associated with discipline, formality, and administrative efficiency. Its users recall it less as a physical environment and more as a system - a spatial matrix in which routines and hierarchies were both manifested and reinforced. The building thus becomes a vessel of organizational identity and procedural continuity.

By contrast, the Ports Authority, while visually striking from a distance, registers weak mnemonic engagement. Its architectural form monolithic and uninviting, offers limited narrative hooks or spatial character. As a result, it fails to embed itself in collective memory, functioning more as an infrastructural shell than a cultural entity.

Across the four case studies, the findings collectively demonstrate how architectural form becomes meaningful through narrative inscription rather than visual presence alone. The process by which users recall, reinterpret, and emotionally invest in these buildings substantiates the theoretical proposition that modern heritage operates as a living archive of cultural memory. The Saudi Central Bank’s disciplined spatial order, for instance, manifests not only institutional authority but also what Ricoeur terms the “narrative emplotment” of collective purpose. Similarly, the Equestrian Club’s openness and ceremonial character extend Hayden’s argument on the “power of place,” where every day spatial practices sustain public memory (Hayden, 1995). This interpretive synthesis moves the analysis beyond formal typology toward understanding architecture as a mnemonic and social text through which identity is continually rewritten.

Thus, Riyadh’s buildings vary in cultural resonance: the Equestrian Club and Riyadh Palace Hotel hold strong social and symbolic significance, the Central Bank reinforces institutional identity, while the Ports Authority exhibits limited cultural engagement. As illustrates in Figure 11, an excerpt of the semantic mapping, highlighting recurring keywords from stakeholder narratives across all four cases.

Figure 11. Semantic map excerpt highlighting recurring keywords from stakeholder narratives across all four cases.

When examined comparatively, these memory narratives illustrate Assmann’s distinction between communicative and cultural memory. The Equestrian Club’s recollections remain within living generational memory, while the Central Bank and Riyadh Palace Hotel already function as institutionalized cultural memory mediated through media and archives. Recognizing this temporal layering reveals how modern heritage operates simultaneously as lived experience and curated history, blurring boundaries between remembering and historicizing.

4.4 Visual strategy and identity negotiation

The visual and material strategies employed across the four buildings illustrate varying degrees of engagement with local identity and global modernism (Figure 12). The Central Bank’s reimagined rawashin serve as a culturally resonant screen, merging functional shading with aesthetic coding. This detail, paired with the expressive structural system, aligns with broader efforts in Middle Eastern architecture to reconcile modernism with regional identity similar to projects by Kamal El-Kafrawi (Kultermann, 2001) in Cairo or Rasem Badran (WEILAND, 2018) in Amman.

Figure 12. Side-by-side geometries snippets showing materiality, fenestration logic, shading elements, and surface articulation of the four cases.

The Ports Authority takes a diametrically opposite approach, eschewing all decorative or referential elements in favor of brutalist expression. This recalls global precedents such as Paul Rudolph’s Yale Art and Architecture Building (Rohan, 2000) or the Albanian Party Headquarters buildings (Ricci, 2023) that reject visual mediation in favor of raw ideological clarity. In doing so, it signals a bureaucratic paradigm where visibility is neither aesthetic nor strategic.

The Equestrian Club’s visual language is simultaneously abstract and evocative. Its sloped roofs, recessed courtyards, and glass intersections recall regional desert architecture reimagined through structural clarity and formal dynamism. The club achieves what few public buildings in Riyadh do: the synthesis of symbolic depth with recreational utility.

The Riyadh Palace Hotel, with its mirrored surfaces and triadic geometry, exemplifies the architectural globalization of the late 20th century. It incorporates symbols of international hospitality design - monumentality, verticality, and transparency, while loosely referencing local motifs through color and form. Its architectural identity is performative, constructed for external perception rather than internal tradition.

This tension between global performativity and local referentiality exemplifies what Bhabha terms the “third space” of cultural production, a hybrid zone where imported modernist aesthetics are re-signified through local symbolism. The Riyadh Palace Hotel thus materializes a visual discourse of negotiated modernity, demonstrating how architecture mediates between aspiration and belonging within post-oil Saudi urbanism.

Thus, by connecting spatial form, semantic mapping, and narrative recollection within a single interpretive frame, the analysis underscores how modern architecture functions as both evidence and expression of collective identity. This integration demonstrates that the hybrid documentation model is not only methodological but also conceptual, translating narrative theory and memory studies into a spatially grounded analytical practice.

4.5 Implications for documentation practice

The application of the hybrid documentation model demonstrated its efficacy in capturing architecture as both physical object and cultural text. By layering spatial observation with narrative recollection and semantic mapping, the documentation process revealed the latent meanings embedded in architectural form and function. The model enabled not only the recovery of physical data but the illumination of symbolic and emotional geographies, making visible the unseen dimensions of Riyadh’s modern heritage.

Notably, the documentation process itself became participatory and interpretive. Users reengaged with forgotten buildings; their spatial stories were drawn onto plans, annotated into diagrams, and layered over archival imagery. This approach transformed documentation from a technical record into a platform for re-activation, reframing these buildings as narrative anchors in the urban memory of Riyadh.

However, the process of documenting memory is never neutral. Heritage narratives are shaped by power relations that determine which voices are amplified and which remain marginal. Within the participatory workshops, for example, variations in professional authority, gender, and social class influenced whose recollections guided collective interpretation. Recognizing these asymmetries is essential for ensuring that participatory documentation does not reproduce institutional hierarchies under the guise of inclusivity. The hybrid documentation model therefore adopts a reflexive stance, acknowledging that institutional access and socio-cultural privilege affect both data collection and interpretation. By explicitly addressing these dynamics, the model aligns with current decolonial and inclusive heritage discourses that call for shared authorship, equitable representation, and transparency in curatorial decision-making.

Taken together, the comparative findings reveal that modern architecture in Riyadh cannot be understood through typological or chronological description alone. Its significance emerges through the interplay of narrative, memory, and spatial meaning, each operating as a semiotic layer within the city’s evolving identity. The hybrid documentation model demonstrates that the act of mapping and narrating buildings transforms them from static artifacts into dynamic cultural texts. This analytical synthesis moves beyond descriptive comparison by showing how semantic and experiential data collectively articulate a theory of modern heritage as an interpretive, participatory process rather than a stylistic category.

The four case studies, when read comparatively, offer a rich cross-section of Riyadh’s architectural transformation in the late 20th century. They reveal modernism not as a singular style but as a site of negotiation, between function and expression, authority and community, global models and local meaning. The hybrid documentation model introduced in this study has proven effective in rendering these complexities visible, offering a methodological framework that is both analytically rigorous and culturally attuned. In revealing how space, memory, and meaning intersect across sectors, the study redefines architectural documentation not as passive preservation, but as an active tool for interpreting and curating urban identity (Table 4).

5 Recommendation

The findings of this research confirm that Riyadh’s modern architectural heritage is a multidimensional asset, functioning as a record of late 20th-century urban transformation, a vessel for cultural memory, and a platform for negotiating identity between local traditions and global modernism. By applying a hybrid documentation model that merges semantic mapping, narrative theory, and digital storytelling, this study has demonstrated the capacity to capture both the tangible and intangible values of modern heritage. The analysis of four typologically diverse case studies has revealed persistent gaps in recognition, documentation, and public engagement, but it has also identified clear pathways for preserving these structures as living components of the city’s identity. The following recommendations aim to translate these insights into actionable strategies for heritage professionals, policymakers, and educators.

The formulation of these recommendations was directly shaped by the narratives and participatory insights collected during the study. Participants’ reflections revealed recurring concerns about the absence of accessible heritage documentation tools, the limited recognition of modern buildings in official inventories, and the disconnect between academic training and on-site heritage practices. These narratives informed the proposed policy shifts toward inclusivity and adaptability, emphasizing heritage frameworks that respond to lived experience rather than solely to institutional mandates. Similarly, feedback from architecture and planning students highlighted the need for curricula that integrate storytelling, community engagement, and digital literacy. The recommendations thus emerge not as abstract propositions but as extensions of empirical findings grounded in users’ and practitioners’ experiences with Riyadh’s modern heritage.

Institutionalize Hybrid Documentation in Heritage Policy.

• Embed semantic mapping and narrative-based documentation into national and municipal heritage protocols to safeguard both physical form and cultural meaning.

• Establish official classification criteria for modern heritage in Saudi Arabia, reflecting typological diversity, socio-cultural significance, and architectural innovation.

Enhance Public Participation in Heritage Documentation.

• Launch community-driven documentation initiatives that empower residents, users, and local historians to contribute spatial memories, archival material, and oral histories.

• Use participatory workshops and interactive digital platforms to ensure plurality of perspectives in heritage narratives.

Leverage Advanced Digital Technologies.

• Integrate GIS mapping, 3D scanning, VR walkthroughs, and semantic archiving platforms to represent the spatial, temporal, and narrative dimensions of heritage assets.

• Create an open-access national modern heritage database that consolidates plans, imagery, narratives, and semantic layers for research, policy, and public engagement.

Bridge Documentation and Design Education.

• Introduce hybrid documentation methods into architecture, planning, and conservation curricula in Saudi universities, fostering skills that combine cultural interpretation with advanced digital tools.

• Encourage joint projects between academia and heritage institutions to ensure research outputs directly inform policy and conservation strategies.

Develop Typology-Specific Conservation Strategies.

• Recognize the distinct needs of governmental, institutional, and hospitality heritage by tailoring documentation and preservation approaches to their functional, symbolic, and spatial roles.

• Employ remote sensing and archival analysis for high-security sites, and prioritize public engagement and interpretation for civic or cultural venues.

Shift from Static Preservation to Adaptive Stewardship.

• Adopt an evolving approach to preservation that incorporates ongoing narratives, spatial adaptations, and shifting user experiences.

• Promote adaptive reuse projects that preserve architectural integrity while enabling contemporary use, ensuring heritage remains relevant to urban life.

6 Conclusion

This study has addressed a critical gap in Saudi Arabia’s heritage discourse by proposing and testing a comprehensive, narrative-driven, and technologically adaptable model for documenting modern architectural heritage. Riyadh’s post-oil boom architecture of the 1970s and 1980s represents a pivotal layer of the city’s identity, yet it has been marginalized in conventional heritage frameworks. By applying a hybrid approach that integrates semantic mapping, narrative theory, and digital storytelling, the research demonstrated how documentation can move beyond static description to encompass the cultural meanings, lived experiences, and symbolic associations that shape architectural identity.

The case studies revealed that modern heritage in Riyadh is neither uniform nor peripheral; rather, it embodies diverse strategies of negotiation between local traditions, institutional authority, civic life, and global aspiration. These findings highlight both the shortcomings of conventional documentation - rooted in selective preservation and a narrow focus on form - and the potential of hybrid strategies to render visible the multiple layers of memory, identity, and function embedded within modern architecture. In doing so, the study underscores the importance of reframing documentation as a cultural practice capable of reflecting complexity and diversity in non-Western contexts.

The conceptual contribution of this study lies in demonstrating that heritage documentation can operate as a theory of interpretation rather than solely a method of record. The hybrid model reframes documentation as a narrative act that translates cultural memory into spatial representation, merging tangible and intangible evidence through participatory and semantic processes. This theoretical stance extends the principles of integrative heritage frameworks by embedding meaning-making within the act of documentation itself. In doing so, it establishes a transferable analytical approach applicable to other rapidly modernizing, non-Western contexts where cultural identity is in flux.

The study also exposes a series of practical and epistemological limitations. While the participatory workshops and interviews captured diverse perspectives, institutional and accessibility constraints limited the inclusion of certain social groups, particularly women and maintenance staff, whose lived experiences could further enrich the interpretive depth. Future studies could employ longitudinal engagement or digital participatory platforms to enhance inclusivity and temporal continuity. Moreover, the integration of advanced semantic technologies such as AI-driven text mapping or geospatial storytelling, offers promising extensions of the hybrid model’s analytical potential.

By drawing these conceptual and empirical strands together, the study underscores that documentation is not the end point of preservation but the medium through which cultural meaning evolves. Linking theoretical reflection, field-based narrative, and applied policy design, the research advances a coherent framework that connects interpretation, participation, and urban heritage management. The proposed model thus contributes to rethinking how cultural identity is spatially articulated and continuously renegotiated within the urban modernities of Saudi Arabia and beyond.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Committee, University of Hail, Ministry of Education, Kingdom of Saudia Arabia (No. H-2025-906). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. MA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aas, C., Ladkin, A., and Fletcher, J. (2005). Stakeholder collaboration and heritage management. Ann. Tourism Res. 32 (1), 28–48. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2004.04.005

Al-Naim, M. A. (2008). “Riyadh: a city of ‘institutional’ architecture,” in The evolving Arab City (Routledge), 132–165.

Al-Zaidi, B. M., and Khalil, S. M. (2023). Globalization and its impact on the local identity of architecture. Periodicals Eng. Nat. Sci. 11 (5), 106–116. doi:10.21533/pen.v11.i5.188

Alghamdi, N., Alnaim, M. M., Alotaibi, F., Alzahrani, A., Alosaimi, F., Ajlan, A., et al. (2023). Documenting Riyadh City’s significant modern heritage: a methodological approach. Buildings 13 (11), 2818. doi:10.3390/buildings13112818

Alghamdi, N., Alzahrani, A., Alotaibi, F., Alosaimi, F., Ajlan, A., Alkudaywi, M., et al. (2024). Fusion and transformation: the 1950s architectural metamorphosis of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J. Archit. Plan. 36 (4).

Alnaim, M. M. (2024). Cultural imprints on physical forms: an exploration of architectural heritage and identity. Adv. Appl. Sociol. 14 (3), 141–160.

Alsheliby, M. (2015). Crisis of traditional identity in the built environment of the Saudi cities. Newcastle University.

Alsuwaidi, F., Sabri, R., and Belpoliti, V. (2021). Investigating the values of modern architectural heritage in Dubai, UAE. IOP conference series: materials science and engineering.

Apaydin, V. (2020). “The interlinkage of cultural memory, heritage and discourses of construction, transformation and destruction,” in Critical perspectives on cultural memory and heritage: construction, transformation and destruction, 13–30.

Assmann, J. (2010). “Globalization, universalism, and the erosion of cultural memory,” in Memory in a global age: discourses, practices and trajectories (Springer), 121–137.

Assmann, J. (2011). “Communicative and cultural memory,” in Cultural memories: the geographical point of view (Springer), 15–27.

Avrami, E., Macdonald, S., Mason, R., and Myers, D. (2019). Values in heritage management: emerging approaches and research directions.

Camacho, S. (2022). “Brazilian Architectural Archives and Contemporary Challenges 1: the Archives of Paulo Mendes da Rocha, Gregori Warchavchik, Lina Bo Bardi, Roberto Burle Marx, Lúcio Costa, and Oscar Niemeyer,” in The routledge companion to architectural drawings and models (Routledge), 62–79.

Chen, Y., Wu, Y., Sun, X., Ali, N., and Zhou, Q. (2023). Digital documentation and conservation of architectural heritage information: an application in modern Chinese architecture. Sustainability 15 (9), 7276. doi:10.3390/su15097276

Costamagna, E., and Spanò, A. (2012). Semantic models for architectural heritage documentation. Euro-mediterranean conference.

Ginzarly, M., Houbart, C., and Teller, J. (2019). The historic urban landscape approach to urban management: a systematic review. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 25 (10), 999–1019. doi:10.1080/13527258.2018.1552615

Guven Ulusoy, F. (2023). Integrated documentation of tangible and intangible cultural heritage in urban historical sites. Int. Archives Photogrammetry Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 48, 701–707. doi:10.5194/isprs-archives-xlviii-m-2-2023-701-2023

Hanif, S., and Riza, M. (2025). The dynamics of heritagization in urban regeneration: East-West dichotomy. J. Contemp. Urban Aff. 9 (1), 164–186. doi:10.25034/ijcua.2025.v9n1-9

Harrison, R., DeSilvey, C., Holtorf, C., Macdonald, S., Bartolini, N., Breithoff, E., et al. (2020). Heritage futures: comparative approaches to natural and cultural heritage practices. UCL Press.

Kultermann, U. (2001). Education and Arab identity kamal El-Kafrawi: University of Qatar, Doha. Prost. Znanstveni Časopis Za Arhitekturu I Urbanizam 9 (21), 79–83.

Lynch, K. (2020). “The City image and its elements: from the image of the City (1960),” in The City Reader (Routledge), 570–580.

Mkhabela, S. (2023). Urban scripting audio-visual forms of storytelling in urban design and planning: the case of two activity streets in. Johannesburg: Johannesburg University of the Witwatersrand.

Moscatelli, M. (2022). Cultural identity of places through a sustainable design approach of cultural buildings. The case of Riyadh. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1026, 012049. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/1026/1/012049

Nankov, N. (2014). The narrative of Ricoeur's time and narrative. Comparatist 38 (1), 227–249. doi:10.1353/com.2014.0034

Nia, H. A., and Rahbarianyazd, R. (2020). Aesthetics of modern architecture: a semiological survey on the aesthetic contribution of modern architecture. Civ. Eng. Archit. 8 (2), 66–76. doi:10.13189/cea.2020.080204

Othman, E., Abdelghany, S., and Farghaly, T. (2025). Adopting GIS to enhance alexandrian urban cultural heritage: the case of Alexandria, Egypt. J. Contemp. Urban Aff. 9 (1), 227–255. doi:10.25034/ijcua.2025.v9n1-12

Patias, P. (2006). Cultural heritage documentation. Int. Summer Sch. Digital Rec. 3D Model. Aghios Nikolaos, Creta, Grecia, Abril, 24–29.

Phillips, J. (2005). “The future of the past: archiving Singapore,” in Urban memory (Routledge), 171–194.

Pinho, P., and Oliveira, V. (2009). Cartographic analysis in urban morphology. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 36 (1), 107–127. doi:10.1068/b34035

Putra, S. Y., and Yang, P.-J. (2005). Analysing mental geography of residential environment in Singapore using GIS-based 3D visibility analysis.

Rey-Pérez, J., and Pereira Roders, A. (2020). Historic urban landscape: a systematic review, eight years after the adoption of the HUL approach. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 10 (3), 233–258. doi:10.1108/JCHMSD-05-2018-0036

Ricci, M. (2023). “Albanian architecture introduction,” in Albanian architecture and design (Printing House FLESH), 19–21.

Rohan, T. M. (2000). Rendering the surface: Paul Rudolph's art and architecture building at Yale. Grey Room (1), 85–107. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1262552.

Sadler, S., and Sadler, S. (2025). Beirut urban lab. Des. Cult. 17 (2), 237–240. doi:10.1080/17547075.2022.2038980

Song, H., and Selim, G. (2022). Smart heritage for urban sustainability: a review of current definitions and future developments. J. Contemp. Urban Aff. 6 (2), 175–192. doi:10.25034/ijcua.2022.v6n2-5

UNESCO (2011). Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. Paris, 10 November 2011. Available online at: https://whc.unesco.org/document/160163 (Accessed on November 24, 2025).

van den Heuvel, D., Mesman, M., Quist, W., and Lemmens, B. (2008). Moroccan modernism revamped. Chall. Change Deal. Leg. Mod. Mov., 213.

Weiland, A. (2018). Chapter eight rasem badran’s reflections. Contemp. Arab Contribution World Cult. Arab-Western Dialogue, 153.

Keywords: modern architectural heritage, narrative documentation, cultural memory, participatory methods, semantic mapping, Riyadh

Citation: Alghamdi N and Alnaim MM (2025) From structure to story: semantic mapping and narrative documentation of Riyadh’s modern architecture. Front. Built Environ. 11:1710185. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2025.1710185

Received: 21 September 2025; Accepted: 17 November 2025;

Published: 03 December 2025.

Edited by:

Praveen Kumar Maghelal, Rabdan Academy, United Arab EmiratesReviewed by:

Hourakhsh Ahmad Nia, Alanya University, TürkiyeMadhavi P. Patil, Northumbria University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Alghamdi and Alnaim. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Naif Alghamdi, bmFhZ0Brc3UuZWR1LnNh

Naif Alghamdi

Naif Alghamdi Mohammed Mashary Alnaim

Mohammed Mashary Alnaim