- Department of Civil, Environmental, Land, Building Engineering and Chemistry, Polytechnic University of Bari, Bari, Italy

Heritage assets constitute a fundamental resource within territorial development strategies for their architectural, historical, and artistic value, serving as key drivers of sustainable and resilient planning. Their relevance in current urban governance stems from the wide range of interventions that involves this type of assets, such as adaptive reuse, which allow to obtain resource efficiency implementation, waste reduction and support the realization of projects that are more adaptable. These approaches not only contribute safeguard cultural identity but also create new revenues, strengthening the financial self-sufficiency of heritage sites. Considering the growing interest in these financial tool’s mechanisms, there is a clear need to better understand the investment dynamics associated with these assets. In response to this requirement, the present article conducts a systematic analysis of academic literature on the topic, following consolidated methodology, with the aim of collecting and organizing a set of components representative of the most critical aspects related to interventions on the built heritage. The resulting factor abacus is intended as a decision-support tool for financial developers, enabling more informed and strategic choices through a clearer understanding of key components. Based on a review of 30 academic contributions, the study identifies 14 factors grouped into 5 categories to highlight both their relative significance and their primary areas of influence. Additionally, the analysis distinguishes between discouraging and incentive factors, offering immediate insight into the risks and opportunities associated with a project and thereby supporting the private actors involved.

1 Introduction

Heritage assets represent fundamental and non-renewable aesthetic, economic and cultural resources (Shipley et al., 2006), whose preservation is crucial to ensure the transmission of their intrinsic significance to future generations. Among the various assets known for their essential role, heritage buildings constitute a fundamental part of a country’s identity (Othman and Mahmoud, 2022) conveying a meaningful combination of values relevant from both a public and private point of view. Despite the recognition of their importance and the growing attention paid to cultural heritage and its enhancement, cases of severe degradation, abandonment and demolition are still frequent, leading to significant losses not only from a financial perspective but also from cultural, social and historical-artistic standpoints. One of the main causes of this phenomenon lies in the insufficiency of human and financial resources available to state administrations, traditionally responsible for managing this type of asset (Lupacchini and Gravagnuolo, 2019). Over time, the described inability of institutional governments to meet the high costs required for maintenance, restoration and public use of architectural heritage has determined the need for institutional authorities to promote new strategies aimed at involving the private sector, to ensure greater economic stability and resilience. These policies are based on achieving a balance between the exploitation of the “cultural capital” of assets—meaning their cultural value (Rizzo and Throsby, 2006) — and the long-term safeguarding of their historical-artistic features. Specifically, the goal of these initiatives is to achieve both financial sustainability and the preservation of heritage properties, guaranteeing that future generations continue to benefit from them. To encourage greater private investors’ participation, adaptive reuse interventions, i.e., projects aimed at changing the use of existing buildings, often of historical-artistic or cultural value, thereby avoiding their demolition (Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025) and abandonment, can be promoted. In fact, the monetary returns generated from new intended uses implementation can allow to reach higher financial self-sufficiency and reduce the risk of failure.

In light of this context, cultural heritage projects, such as those involving reuse and re-functionalization, represent a key component of the circular economy and sustainability. By focusing on the enhancement of existing assets, these operations avoid demolition and new construction, helping to slow down the extraction of natural resources and to reduce energy consumption, the construction and demolition waste production and the greenhouse gas emissions (Foster and Saleh, 2021). These types of interventions, therefore, support the ecological transition by promoting resource savings and fostering the regeneration of core values such as inclusion, solidarity, responsibility, and the capacity to care for both people and the environment (Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025). Given this scenario, the management of historic-architectural heritage, through innovative planning and design approaches, fits within a broader system of financial investments oriented towards meeting environmental, social, economic and cultural sustainability requirements. In particular, these operations are included within government policies aimed at supporting sustainable and resilient interventions through economic incentives and various international declarations and conventions promoted by the United Nations (Barral, 2012), at both the European and national levels. Among the different ways of achieving these international goals, ethical investments and social bonds are detected. The former - which may take the form of socially responsible, green, environmental, or sustainable mutual funds - are rapidly growing in both size and variety (Arfa et al., 2022). Similarly, the social bonds are an essential part of the sustainable finance system, enabling governments, companies or local authorities to pursue resilient projects for local areas capable of adapting to current challenges (Locurcio et al., 2025). These tools are not only relevant for public administrations, but are increasingly attractive to private investors too, as they offer an efficient market mechanism with both positive social impacts and financial returns (International Platform on Sustainable Finance, 2023). In this sense, a general increase in the spread of resilient and sustainable investments, such as ethical and social ones, is currently attested. Their growing appeal derives from the need for tools - different from traditional ones - capable of responding to critical events and environmental transformations. The investment in architectural heritage is part of this initiatives category: due to the key role that the heritage assets play in urban governance plans, they are part of sustainable territorial policies and the conscious management of resources.

However, it is important to underline the considerable complexity of these intervention strategies, that should involve wider objectives, the potential impacts in various areas (environmental, social, economic, financial, etc.) and the many specific characteristics of cultural assets. Generally, these distinctive aspects—such as the presence of restrictive regulatory codes, the high recovery and the maintenance costs and the need for specialized labor—significantly influence the investment dynamics. Moreover, characteristics such as non-excludability, the non-rivalry in consumption and the generation of positive effects for which beneficiaries incur no cost, represent externalities for which no explicit market compensation is required (Moreschini, 2003) and determine a misalignment with investors’ interests, particularly in the private sector. These features (which are often mainly relevant from a public perspective), together with the high complexity of the strategic political framework in which architectural heritage investments are included, highlight the necessity to identify and classify the most relevant impact factors to provide guidelines for private actors when assessing investments in cultural heritage to address the choices processes. To this end, the present work aims to examine the aspects covered in the existing literature on financial operations involving cultural buildings. These components have been filtered and collected into a set of key elements, proposed as a decisions support tool for private interventions in heritage field.

2 Aims

Taking into account the essential role recognized for heritage assets in social, aesthetic (Romão et al., 2016), symbolic, historical (Rizzo and Throsby, 2006; Della Spina, 2021) and artistic terms, the need to ensure their long-term protection is attested, with the aim of guaranteeing their accessibility for future generations. To this end, as noted by Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo (2025), the consistency with the principles of authenticity and integrity, which are fundamental for the genuine transmission of values, represents a crucial issue. This means avoiding decisions driven solely by financial convenience or, conversely, by a purely acritical conservative approach. The so described necessity to identify innovative approach strategies has been also driven, during the last decades, by the insufficiency of available funds by government bodies has led to increasing cases of degradation, abandonment and underuse of cultural assets. In addition, initiatives capable of involving private resources are always increasingly growing, as these are indispensable for the conservation and safeguarding of heritage on the basis of articulated integrated funding policies. In this context, the financial sustainability of this kind of intervention becomes significant, as it represents the achievement of a balance between the conservation of assets and the exploitation of their instrumental value (Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025). Indeed, the ability to autonomously cover the costs of maintenance, restoration and management through investment returns allows the satisfaction of both public and private expectations and targets. The depicted issue of the financial feasibility of the interventions to be carried out on these assets’ category falls within a specific framework of redirection of strategies toward the achievement of sustainability and resilience goals. In recent times, a growing attractiveness of this type of investment, especially due to the inability of traditional tools to adaptively respond to the occurrence of climatic and environmental emergencies, has been detected.

The need to consider different objectives and the involvement of various sectors in financial operations related to heritage assets generally determine a high level of complexity in investors’ decision-making processes. In particular, these operations are characterized by several factors that distinguish them from more common real estate market initiatives, and their investigation and understanding is an important step in the choice processes and in the development of intervention plans.

Among the different sustainable investment approaches, the adaptive reuse represents one possible solution: in fact, the functional reconversion of cultural properties allows, on one hand, the generation of returns from the different uses of the asset, and on the other, it ensures the preservation of the asset’s cultural value.

The present academic literature review is part of this framework with the aim of identifying the most influential factors for the development of private investment projects in heritage assets. The definition of the most relevant aspects set pursues to provide a support operative tool for investors in their decision-making processes, guiding toward more informed choices regarding the different implications and specific characteristics of cultural assets. To this end, the present study proposes an systematized analysis and a structured articulation of the main components of cultural heritage assets operations from the investors’ perspective following the classifications proposed in some studies named PESTEL-CA model (which categorizes influential aspects across Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental, Legal, Cultural, and Administrative domains) (Ikiz Kaya et al., 2021). The adoption of a private point of view is instrumental in excluding issues that are key only when observed in public terms (e.g., social, environmental, etc.).

The work is organized as follows: Section 3 presents the methodological approach implemented for the literature review, Section 4 provides a critical analysis of the specific factors of heritage investments aimed at defining the set of crucial components to be considered by the private operators. Section 5 outlines the conclusions and potential future developments.

3 Methodological approach

The present work intends to define a set of factors that represent the key aspects that must be considered when developing private investment projects in heritage assets; to this aim a systematic literature review has been conducted on the basis of the application of a consolidated methodology. In particular, the investigation has been developed following a series of steps borrowed from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) model (Moher et al., 2015). In fact, as outlined in this model, eligibility criteria were first established to filter the articles to be included in the study sample. The criteria adopted have been i) the full access to the entire text of the publication, ii) the comprehensibility based on the language of the paper, and iii) the consistence of the topic dealt with within the research with the investigated focus.

Subsequently, the information sources and the search strategy have been defined. At this stage, the selection of databases, keywords and their combinations has been carried out. In specific terms, two electronic databases (Google Scholar and Scopus) have been used and consulted. This choice has been connected to these databases characteristics: Google Scholar is an open-access academic search engine that indexes scholarly articles, theses, books, conference papers and patents across a wide range of disciplines and languages, making it a valuable resource for global research discovery. On the other hand, Scopus is a subscription-based, predominantly English-language abstract and citation database maintained by Elsevier, which offers comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed literature and requires institutional access, often used for in-depth citation analysis and research performance evaluation. With reference to the keywords used for both databases, these have been selected for obtaining a wide range of articles focused on the analyzed topic: they are heritage, assets, investment, factors, barriers and cultural. Moreover, some combinations of the listed keywords have been identified to broaden potential coherent contributions. In addition to the results directly retrieved through these search engines, academic references cited in the initially selected studies have been also included to expand the analysis sample and to gain a wider understanding of issues that have been mentioned but not deeply explored in the original documents. As a result of applying this search strategy (selection criteria, databases, keywords) and of the inclusion of cited studies in other contributes, 30 articles were selected from an initial pool of 1,202 results.

Therefore, following the PRISMA model, the definition of study records, i.e., the documents data processing and treatment modalities, has been carried out. This has involved the determination of the data management approaches, the selection process for filtering articles and the data collection phase to extract relevant information. Specifically, the information extracted from each article have included: the title, the year of publication, the abstract, the subject of the research, the geographical context investigated, and the factors explained with regards to the aims of the present review, i.e., the variables to be considered in the private investments in cultural heritage assets. For data management purposes, a record retrieval form has been created: for this end, dedicated spreadsheets have been designed to organize the information in a structured way, enabling easier comparison across studies. The use of this approach draws on consolidated methodologies such as grounded theory coding, which encompasses the open coding procedure, commonly applied in qualitative content analysis. Indeed, as with the open coding use, the process implemented in the present work, through the use of the described data management systems, enabled the collected information to be broken down into discrete parts in order to identify and label key concepts. Furthermore, the adopted methods, well established within the grounded theory framework, base the obtained results on the direct analysis of data rather than on any ex-ante hypothesis.

The selection of the articles has been based on screening the titles and the abstracts. In particular, the carried-out selection process entailed a manual screening of research results, rather than an automated one, in order to verify that the topics addressed were aligned with the objectives of this review. In some cases, it has been necessary to read the full study or its most relevant sections in order to understand the consistency with the theme and the specific point of view of the wider topic covered in each paper. This process has led to the exclusion of documents that investigated exclusively the heritage evaluation methods without addressing the specific features of heritage investments, or that did not explore how the attributes of cultural heritage buildings affect investment outcomes and decision-making processes.

Moreover, contributions centered solely on energy, social or climate-related risk factors have been excluded, as they are not specific to heritage investment dynamics, i.e., those initiatives carried out by private subjects or by them in cooperation with Public Administrations. In this sense, it should be recalled that the private sector involved in this typology of initiatives is exclusively interested to the verification of the financial feasibility of the operation, that is the obtainment of an extra-profit in monetary terms, by assuming the intervention risks.

Finally, the data collection has been performed with the manual extraction of the main information and the insertion of the relevant ones into the previously designed Excel form. As mentioned above, the obtained items have included: the title, the year of publication, the abstract and the specific factors identified in each document as influential in cultural heritage investments (e.g., government incentives, legislative restrictions, etc.).

The main difficulties faced during the literature analysis are derived from the tendency of many studies to focus on issues not exclusively connected to cultural heritage investments, but rather common to the adaptive reuse of standard/ordinary buildings - such as high energy efficiency costs, zoning limitations on land use and risks related to catastrophic events. The specific perspective of the cultural properties has represented a significant discriminating element for identifying the sample of studies to be analyzed. In the final phase of data synthesis, a graphical representation of the results obtained has been developed in terms of the factors analysed and recognized as fundamental, explaining the relationships between them and the categories to which they belong. Specifically, these categories have been taken from the literature following a defined and consolidated approach.

The described steps of the methodological approach implemented for the aims of the present research (i.e., to build a set of the main factors to be taken into account into in the cultural heritage assets investment from the private point of view), which have guided the development of this literature review, are summarized in the diagram shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Steps of the methodological approach applied for carrying out the academic literature analysis.

By examining the results obtained from the systematization of the extracted data, it has been observed that a substantial portion of the analyzed contributions (19) focuses on a well-defined geographical area, addressing the research topic through the examination of specific case studies. Among these, Othman and Mahmoud (2022) deal with the issue of reuse of historic buildings in Egypt by comparing study cases in Cairo or in Alexandria with European examples of adaptive reuse. Likewise, Rossitti et al. (2021) analyse a project for a historical rural landscape in Pantelleria island in Italy while Yung and Chan (2012) examine the Asia-Pacific area focusing on seven specific buildings publicly recognised as part of cultural heritage (Allen and Bradley, 2000; Rossitti et al., 2021; Della Spina et al., 2023; Ashworth, 2002; Othman and Mahmoud, 2022; Stas, 2007; Dell’Anna, 2022; Shipley et al., 2006; Forbes, 2021; Savoie et al., 2025; Zeadat, 2024; Yung and Chan, 2012; Pintossi et al., 2021; Bullen and Love, 2011; Aigwi et al., 2018; Conejos et al., 2019; Bedate et al., 2004; Djebbour and Biara, 2020; Ferretti et al., 2014). A smaller portion of the literature (7 contributions) explores the topics of the built heritage and adaptive reuse by examining the international context through examples located in different countries (Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025; AL-Shimmery & Al-Ali, 2022; Barral, 2012; Ikiz Kaya et al., 2021; Pintossi et al., 2023; Colenbrander, 2019; Wilkinson et al., 2014). Conversely, some studies (4) adopt a more general perspective without focusing on specific contexts (Arfa et al., 2022; Rizzo and Throsby, 2006; De Silva and Perera, 2016; Pedersen, 2002).

Although the analysed sample comprises contributions focusing on the study and analysis of cultural heritage, as well as on the factors that most significantly influence decision-making processes related to investments in the built heritage, it is nevertheless possible to identify additional themes explored within each work. Part of these contributes addresses the social dimension of adaptive reuse projects for heritage assets, examining their impact on the quality of life of local communities and the crucial role played by the involvement of various stakeholders (Arfa et al., 2022; Dell’Anna, 2022; Djebbour and Biara, 2020; Bullen and Love, 2011; Aigwi et al., 2018; Ikiz Kaya et al., 2021; Pintossi et al., 2023; Colenbrander, 2019). Another issue covered in a small quote of the sample is the relationship between functional reuse of built heritage and environmental sustainability; in this sense is observed how these projects drive the circular economy by extending building lifespans, reducing waste, minimizing material and energy consumption (Pintossi et al., 2021; Wilkinson et al., 2014; De Silva and Perera, 2016; Ikiz Kaya et al., 2021; Conejos et al., 2019). In different studies, investments related to cultural heritage are considered comparable to new construction in terms of economic return and therefore analysed with the same evaluation approaches (Rizzo and Throsby, 2006; Allen and Bradley, 2000; AL-Shimmery & Al-Ali, 2022; Stas, 2007; Shipley et al., 2006; Ferretti et al., 2014; Savoie et al., 2025).

4 The proposed set of key factors for heritage assets investments

In the light of i) the growing role of private actors within the initiatives on cultural assets, ii) the widespread objectives of sustainability and financial resilience and iii) the high complexity of heritage investments, the need to thoroughly identify and analyze the factors underlying decision-making processes and the development of these operations is increasingly central. Indeed, the effective definition of a set of factors on which the investor should be paid attention is essential for the creation of efficient and informed resource allocation strategies. To this end, by considering the diversity and number of these influencing factors on investments choices, along with the extent of the relationships between them, the implementation of a critical and structured exam of the aspects addressed in the relevant literature, aimed at systematizing and understanding them, represents a fundamental step.

In this regard, several academic studies have explored the factors influencing the decision-making, design and execution phases related to heritage investments (Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025). As previously mentioned, in various contributions, the main components studied have been classified and grouped according to their relevance in the social, economic, legislative, administrative and technical-technological fields (Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025; Othman and Mahmoud, 2022; Ikiz Kaya et al., 2021; Colenbrander, 2019). Among the articles that have categorized factors into areas of interest, in the work by Ikiz Kaya et al. (2021) an integrated evaluation framework, derived from the PESTEL classification, is used (Ikiz Kaya et al., 2021). This articulation has been then expanded by the Authors, in order to include all sectors relevant to the analysis of driving or obstructive factors connected to investments in cultural heritage regeneration and adaptive reuse. In this context, the PESTEL-CA model (Political-Economic-Social-Technical-Environmental-Legislative-Cultural-Administrative) able to provide a wider and comprehensive framework of the categories of key aspects to analyze has been developed. With reference to this classification, Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo (2025) in a semi-systematic analysis of the literature, have highlighted the importance and usefulness to propose a shift towards a more integrated approach that also includes social dimensions as crucial nodes (Colenbrander, 2019).

Given the trends regarding private actors’ preference for sustainable projects in light of recent critical events and territorial transformation processes, the present study develops a grouping of factors different from those observed in the analyzed papers. In particular, in this work a set of aspects that includes only those components specific to heritage investments has been elaborated, focusing on elements that are relevant from a private perspective and that distinguish the cultural assets from traditional real estate operations. Therefore, the environmental sphere, which includes items related to i) natural context protection, ii) changes due to geological, climatic or other factors, iii) pollution, iv) energy efficiency and v) improvement of natural resources (Guzman et al., 2017) as not been included. The decision to exclude this domain is connected to its low relevance within the perspective of individual investors who are not sensitive and interested in environmental issues such as ecosystem preservation or the ecological compatibility of interventions. These elements, in fact, are not associated with direct financial outcomes (in terms of revenues and monetary profit) and do not represent immediate opportunities for improving the sustainability and resilience of investments. Moreover, these aspects are not specific to investments in cultural assets and, thus, do not distinguish them from traditional ones. However, the components within the environmental dimension that directly and strictly influence the returns and costs have been considered in the set of factors, bringing them into the financial sphere. Among these, the costs of decontamination activities necessary after the discovery of toxic or polluting materials, which are more likely near ancient and/or abandoned structures, are taken into account (Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025; Colenbrander, 2019; Wilkinson et al., 2014). Additionally, the reduction of energy consumption due to the reuse of existing properties and materials already present represents an advantage for private operators, as they can incur lower costs (Zhang et al., 2019; Aigwi et al., 2018). These aspects, being indicative of reductions or additions to overall expenses, have been included in the category of the factor called “the maintenance and restoration costs” which is part of the financial domain.

Following a similar logic, the aspects related to the cultural and social scopes, such as “sense of place and identity” (Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025), “sense of community and belonging, collaboration, citizen engagement” (Ikiz Kaya et al., 2021) and social wellbeing, which are not typically of interest to the private investors, have been excluded from the developed factors set. Likewise, the evidential value considered by Romão et al. (2016) and defined as the value derived from the heritage unit’s ability to provide evidence of past human activity (physical remains, written documents, archaeological deposits, etc.) (Romão et al., 2016), has been omitted. In fact, while this aspect is highly relevant from a community perspective, it is considered negligible from the standpoint of private developers who aim to achieve specific levels of financial return.

On the other hand, factors related to the regulatory/legislative, administrative, technical, technological, cultural and architectural issues have been considered significant and, consequently, included in the proposed collection.

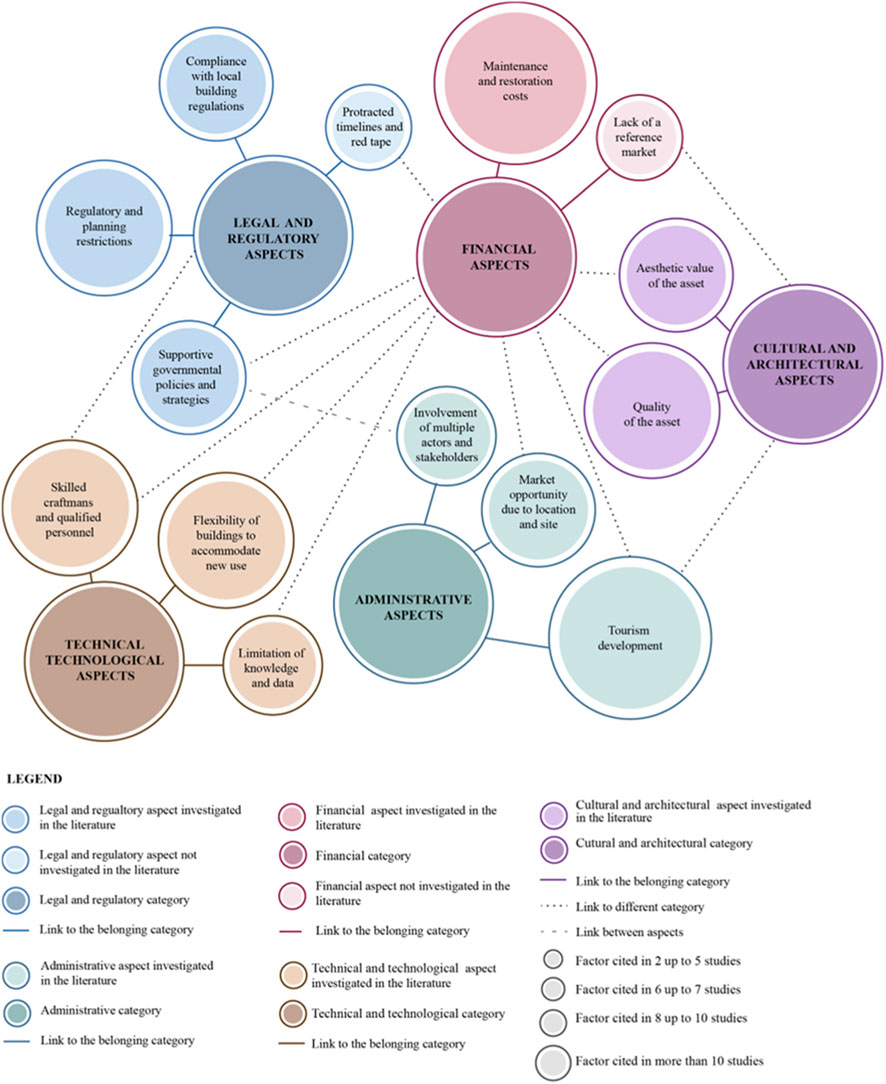

As a result of the illustrated observations, a set of 14 factors has been defined. The key aspects identified as the most influencing within the decision-making processes of private investors on cultural heritage assets operations are: i) the restrictions imposed by normative codes, ii) the need to comply with building codes and legislations, iii) the government policies supporting interventions, iv) the long times required to obtain authorizations and permits, v) the presence of numerous heterogeneous actors and the involvement of a wide range of stakeholders interests, vi) the market opportunities related to the site and location in which the property is included, vii) the tourism development, viii) the quality of heritage assets, ix) the aesthetic value, x) the functional flexibility, xi) the absence or lack of data and information, xii) the use of highly skilled labor and the professional figures, xiii) the maintenance and restoration costs, and xiv) the lack of a reference market useful in the traditional evaluation processes for the assessment of market value.

Figure 2 shows the 14 factors articulated according to the domain to which they are linked, represented by thick segments. The dotted lines indicate connections to spheres from other categories, but still significant, while the dashed lines specify relationships between factors belonging to different groups. These relationships have been identified based on insights from the literature reviewed in the examined sample, as well as through a critical interpretation of the links which has led to the recognition, in some cases, of possibly different relations. The smaller and lighter circles cover factors that are recognized as highly important by the Authors of this work, but which have not been extensively discussed in the existing literature. In addition, a ranking of factor importance is provided based on the frequency of occurrence in the examined sample.

Figure 2. Representation of the set of 14 factors, divided into the 5 corresponding categories, showing the relevant connections and the order of importance.

A more detailed description of the 14 collected factors, their categories, the identified connections, and the reasons behind the choices made in developing the set, is provided below.

4.1 Legal and regulatory aspects category

Among the analyzed key factors included in the legal and regulatory aspects category, the restrictions imposed by normative codes for heritage protection are encompassed. In numerous studies of the reference literature, such constraints are considered particularly relevant as they significantly limit the use and exploitation of assets (Della Spina et al., 2023; Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025; Othman and Mahmoud, 2022; Colenbrander, 2019; Ashworth, 2002; Savoie et al., 2025; Pintossi et al., 2021; Conejos et al., 2019; De Silva and Perera, 2016; Pintossi et al., 2023). In addition to this aspect, it is important to consider the impact of the long times required to obtain authorizations and permits in accordance with the procedures established by current laws. Although this factor is not deeply explored in the literature, it should be included in the set proposed in this study, as it increases the complexity of investments in cultural assets, representing a potential disincentive for private investors. Furthermore, the time required to follow current bureaucratic procedures entails additional costs, making this factor not only part of the legislative and regulatory sphere but also the financial one.

Within the same domain, several Authors (Rizzo and Throsby, 2006; Aigwi et al., 2018; Conejos et al., 2019; De Silva and Perera, 2016; Pintossi et al., 2023; Shipley et al., 2006; Al-shimmery and Al-Ali, 2022; Stas, 2007) attribute a significant role to the need to comply with building codes and legislations for the proper use of real estate assets, as well as the obligation to observe fire safety, seismic security (Pintossi et al., 2023), accessibility barrier, sound control and health protocols (Aigwi et al., 2018).

Another aspect within the normative sphere, explored in various studies (Ikiz Kaya et al., 2021; Colenbrander, 2019; Shipley et al., 2006; Al-shimmery and Al-Ali, 2022; Forbes, 2021; Djebbour and Biara, 2020), concerns the government policies supporting interventions on cultural heritage; these strategies represent a fundamental element for investments in these assets as they provide tools such as funding, grants and tax deductions (Al-shimmery and Al-Ali, 2022) that are particularly effective and incentivizing for investors.

Fiscal contributions and incentives are also considered in the set developed in the present work as closely linked to another factor studied in the literature, namely, the presence of numerous heterogeneous actors and the involvement of a wide range of stakeholders’ interests. Indeed, despite the insufficiency of public funds for cultural heritage management and the consequent need to integrate private resources, the government administrations maintain a decisive role by actively participating in decision-making processes and influencing investment dynamics through the creation of boost tools. Moreover, this issue, often translating into lower intervention costs or monetary aid, is also strictly associated with the financial context.

4.2 Administrative aspects category

This factor related to the presence of multiple actors with diverse objectives represents a significant item also in the administrative aspects category (Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025; Othman and Mahmoud, 2022; Pintossi et al., 2021; Dell’Anna, 2022; Ferretti et al., 2014), as it increases the investment complexity, which, by slowing down intervention timelines, can compromise the success of the entire initiative (Dell’Anna, 2022). Following similar logic, some studies (Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025; Pintossi et al., 2021; Dell’Anna, 2022) consider the greater community involvement as decisive since it promotes the alignment between population needs, preservation goals and private interests. Despite the relevance of this topic, the aspect associated with collective participation has been not included in the developed set as it is non-priority for investors according to their main goals and targets.

A further administrative aspect deemed of high concern to private investors is the reference territorial context, which encompasses the market opportunities related to the site and location in which the property is included (Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025; Colenbrander, 2019; Aigwi et al., 2018; Pintossi et al., 2021; Shipley et al., 2006; Bullen and Love, 2011; Wilkinson et al., 2014). Although the factor of market opportunities related to the asset site is not exclusive to cultural heritage ones, it has been considered important for this study purpose, because specific characteristics can be identified as associated with heritage sites. Indeed, the cultural assets often are situated in prestigious areas such as historic centers or places with high landscape quality and this element can influence the choice processes of potential investors.

The tourism development factor is investigated in various articles of the relevant literature (Allen and Bradley, 2000; Rossitti et al., 2021; Yung and Chan, 2012; Arfa et al., 2022; Barral, 2012; Aigwi et al., 2018; Ikiz Kaya et al., 2021; Colenbrander, 2019; Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025; Moreschini, 2003; Bedate et al., 2004; Pedersen, 2002) aimed at exploring its impacts on the population perceptions (Arfa et al., 2022) and surrounding areas livability (Aigwi et al., 2018). The inclusion of this aspect into the administrative sphere derives from the recognized close relationship between the tourism phenomena and land use and management. However, this choice differs from the literature, where this component is primarily associated with the social domain; in fact, several studies point out the creation of new jobs and opportunities for urban and social redevelopment as the main outcomes of tourism. But these effects are always neglected by private subjects potentially interested in transformation operations of these assets, in accordance with the investor’s goals related to the higher returns obtainable from the use of heritage properties for hospitality or tourism activities (Aigwi et al., 2018). Additionally, the described two factors i) market opportunities related to the site and location in which the property is included and ii) tourism development fall not only within the administrative sphere but also the financial one, as they generate positive effects, such as a favorable market position or the presence of numerous potential buyers or customers, which can be translated into monetary terms. Moreover, in some researches (Bedate et al., 2004; Pedersen, 2002) the heritage buildings are explicitly deemed as crucial properties for local tourism development due to their strong historical and aesthetic value, highlighting a clear connection with the cultural and architectural scope.

4.3 Cultural and architectural aspects category

The quality of heritage assets and the aesthetic value emerge as the most significant factors within the cultural and architectural aspects category, as identified in the literature (Rizzo and Throsby, 2006; Ikiz Kaya et al., 2021; Colenbrander, 2019; Aigwi et al., 2018; Savoie et al., 2025; Shipley et al., 2006; Bullen and Love, 2011; Zeadat, 2024; Ashworth, 2002). In particular, the quality component is represented by the excellence of used materials, the specialization of labor (Savoie et al., 2025) and the durability of elements (Zeadat, 2024) and finishes (Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025). The aesthetic value factor, on the other hand, reflects the influence of historical-artistic features (Rizzo and Throsby, 2006; Ikiz Kaya et al., 2021; Colenbrander, 2019; Aigwi et al., 2018; Shipley et al., 2006; Bullen and Love, 2011; Ashworth, 2002) and cultural weight on financial operators’ decisions. Indeed, the investors are generally attracted by historical, artistic and cultural attributes as they recognize them as a fundamental part of the property market value (Shipley et al., 2006). Moreover, these qualities make heritage properties distinguishable from “ordinary” ones, increasing their appeal (Rizzo and Throsby, 2006). In this sense, the heritage assets commonly constitute “trophy assets” or “iconic assets,” i.e., properties perceived as “trophies” because they are characterized by distinctive peculiarities that encourage investors to operate on “landmark” properties that are highly recognizable. Although these aspects are widely appreciated on the market, it should be underlined that the difficulty to quantify is attested (Ott and Hahn, 2018). In this work, despite their challenging translation into monetary terms, the quality of heritage assets and the aesthetic value are recognized as financial factors since they contribute to the growth of the market value of heritage assets.

4.4 Technical and technological aspects category

With reference to the analyzed studies sample, the most recurring factors included in the technical and technological aspects category concern the absence or lack of data and information, the use of highly skilled labor and the professional figures and the functional flexibility of historic-artistic buildings spaces. Regarding this element (functional flexibility of the spaces), it represents the ability of heritage properties to accommodate uses different from the original ones (Della Spina et al., 2023; Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025; Ikiz Kaya et al., 2021; Colenbrander, 2019; Shipley et al., 2006; Dell’Anna, 2022; Ferretti et al., 2014; Bottero et al., 2019). This factor is considered positive by some Authors, providing big open flexible spaces that can be used in a variety of ways (Shipley et al., 2006). Therefore, minimal interventions compared to those necessary for the repurpose of more recent buildings (less adaptable as they are designed ad hoc for specific function) are required. The reduced costs arising from adaptability to new uses make the functional flexibility component financially relevant. However, other studies (Colenbrander, 2019) consider this factor as a barrier mainly for the fixed structural layout (mon-modular load-bearing structure with thick, continuous and not masonry walls) and the inclusion of large monolithic elements (such as arches, vaults, columns or wooden/stone beams, etc.) that often characterize historical buildings.

Another technical and technological component considered in the proposed set of factors for heritage assets investments to support private operators in the decision-making process is the absence or lack of data and information about the building and its structural and architectural attributes (Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025; Othman and Mahmoud, 2022; Colenbrander, 2019; Pintossi et al., 2021). In particular, the work by Othman and Mahmoud (2022) highlights the importance of in-depth knowledge of the materials, construction techniques and degraded parts. The lack of such information can lead to the failure to identify latent issues that may compromise structural safety (Othman and Mahmoud, 2022), negatively impacting the project’s success by, for example, increasing estimated costs with unforeseen additions (Bullen and Love, 2011). Due to this factor’s influence on costs, it has been linked to the financial sphere as well as the technical and technological one.

Furthermore, several contributions among the selected sample (Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025; Othman and Mahmoud, 2022; Colenbrander, 2019; Savoie et al., 2025; Pintossi et al., 2021; Conejos et al., 2019; De Silva and Perera, 2016; Pintossi et al., 2023; Shipley et al., 2006; Zeadat, 2024) recognize the decisive need, within the technical domain, to employ highly qualified labor and professionals. Specifically, the obligation to use targeted and specific techniques when intervening on heritage properties stems from regulatory constraints that require investors to hire only expert professionals and technicians. In this sense, the high cost of specialized labor in many contexts, compounded by the shortage of highly skilled professionals in the labor market, represents a significant disincentive for developers. In light of the above, this factor has been considered in the present work as belonging to the legal-regulatory and financial domains, as well as the technical-technological one.

4.5 Financial aspects category

In the financial aspects category, considerable attention is given to the maintenance and restoration costs (Fusco Girard and Gravagnuolo, 2025; Othman and Mahmoud, 2022; Aigwi et al., 2018; Ashworth, 2002; Pintossi et al., 2021; Conejos et al., 2019; Della Spina et al., 2023; De Silva and Perera, 2016; Zeadat, 2024; Wilkinson et al., 2014). In this framework, numerous studies highlight the specific and high-quality nature of the original building elements and materials, the need to apply appropriate processing and integration techniques, the scarcity of materials compatible with those of the asset and the costs associated with potential remediation activities.

In addition, in the set of key factors developed in this research, the lack of a reference market useful in the traditional evaluation processes for the assessment of market value (Wilkinson et al., 2014) is a major issue within this context. Specifically, this condition indicates the absence or limited existence of a comparable market to support asset evaluations. In this regard, the study by Moreschini (2003) introduces the concept of “market failure,” referring to the situation in which cultural heritage represents a category of goods for which the market fails to ensure efficient supply.

Although individuals tend to assign utility to these goods, their value assessment is hindered by the inherent difficulty - or impossibility - of determining a specific price through traditional estimative methods.

Even if the lack of a reference market is a factor rarely recognized in the literature, it is given particular relevance in this study: the distinctiveness of heritage assets - characterized by unique features that differentiate them significantly from other assets - creates considerable challenges in identifying a comparable market for buying and selling. The identification of properties analogous in quantitative and qualitative terms to serve as an evaluation benchmark represents a major unresolved issue in this context. Furthermore, the lack of a reference market is closely tied to the cultural and architectural domain, as it stems from the specific artistic and historical nature of heritage buildings, as previously described.

4.6 Discouraging and incentive factors

The 14 factors identified as fundamental in evaluating investments in heritage assets can be then distinguished between factors that incentivize the financial operators to invest in cultural properties, and factors that represent deterrents for the scarce interest in these initiatives from the private point of view. This distinction is shown in the diagram in Figure 3.

Specifically, barriers (i.e., discouraging factors) include the maintenance and restoration costs and the use of highly skilled labor and the professional figures. Moreover, the lack of a reference market useful in the traditional evaluation processes for the assessment of market value, the restrictions imposed by normative codes and the need to comply with building codes and legislations constitute key aspects to be taken into account by potential private operators. In this context, the long times required to obtain authorizations and permits, the absence or lack of data and information and the presence of numerous heterogeneous actors and the involvement of a wide range of stakeholders’ interests are negative aspects focused by investors within the decision-making on heritage assets investments. Specifically, while the inclusion of different figures may be important for public administrations, as it guarantees the approval of the intervention population, adopting a private point of view, this factor has other implications. For instance, it may result in longer times to identify compromises between diverse objectives, causing financial losses. Moreover, support from the local population for the intervention does not constitute a general benefit for private investors.

Conversely, the key aspects considered attractive to investors (incentive factors) include: i) the government policies supporting interventions, ii) the market opportunities related to the site and location in which the property is included, iii) the tourism development, iv) the quality of heritage assets, v) the aesthetic value. With reference to the flexibility of historical spaces to accommodate new functions, according to the different outcomes obtained from the literature analysis on the adaptability of these assets to be reconverted, this factor can be seen both as an incentive factor and a discouraging one and, therefore, in Figure 3 is positioned between the two identified groups. Although the number of attractive factors may be lower compared to the discouraging ones, it should be pointed out that the components identified do not all have the same weight or influence regarding the development of projects involving heritage assets. Given this overview, and in order to provide more structured support to financial operators in decision-making processes, it is advisable to consider the implementation of the present study with an assessment of the degree and manner in which each identified factor influences investment choices. In this sense, the contribution provided by each factor within the intervention decisions is strictly connected to the specificities of the property and the legal, geographical and technical context in which it is located.

5 Conclusions and further insights

Investments related to heritage properties represent a complex and highly relevant topic. Indeed, the growing attention over time given to cultural heritage not only in the historical-artistic field but also in environmental, social, and financial contexts has highlighted the need to preserve these assets while ensuring the transmission of their value to future generations. However, the widespread state of decay and abandonment affecting many historic buildings has attested the ineffectiveness of current management and protection strategies for such assets and the insufficiency of the economic and human resources available to the public entities to whom their preservation and safeguarding are entrusted.

By highlighting the need to implement intervention approaches capable of involving private funds on these assets, it is fundamental to assess the financial sustainability of the initiatives (i.e., to verify the feasibility of the investment from the private point of view). In theoretical terms, the definition of sustainable and resilient programs has a strong appeal for the investors, who are increasingly oriented to develop projects on public asset adopting effective public-private partnerships due to the inability of traditional tools to respond to ever-changing urban contexts.

The sustainability (economic, social and environmental) for investments in the heritage sector can be achieved through the use of assets that simultaneously ensure the conservation of their fundamental historical and artistic characteristics. By considering the relevance of these interventions implications and the urge to carry out operations on cultural assets, the need to identify the most influential factors to be taken into account by private operators for the development of heritage-type investments is detected.

In the present research, a literature review has been conducted aimed at identifying and gathering the factors recognized as fundamental to guide private operators in the decision-making process. In this sense, the analysis and selection of key aspects have been carried out in order to define a support tool for investors by providing an abacus of factors to carefully consider for an appropriate project evaluation. To this end, the elements reported in the investigated literature contributions have been distinguished according to their significance from both private and public perspectives. Specifically, the reduced relevance of certain components with respect to achieving investors’ mainly financial objectives has been considered. In fact, factors primarily noteworthy from a public perspective, such as the possibility of creating more jobs, reducing greenhouse gas emissions through reuse of existing structures and preserving identity value, have been neglected and, thus, excluded from the developed collection.

The systematization of the key factors set has led to proposing a useful operative tool for private stakeholders to be used in choice processes for addressing decisions that are more focused on the implications in various sectors (i.e., the listed categories of aspects) and better informed regarding the specificities of cultural assets.

The main limitations of the present work concern the limited number of contributions reviewed. In this sense, an integration of the review through the inclusion of a larger number of studies to further validate the identified set of factors should be carried out. Furthermore, future insights could assume the collected aspects abacus as basis for developing a heritage investment evaluation model through approaches targeted to quantify the impact of the individual components on investment outcomes. In this sense, the analysis developed in this research represents a valid starting point for the definition of innovative assessment methodologies as it systematizes the factors for their application in financial analyses related to interventions on cultural heritage.

Author contributions

FDL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. ML: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. PM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. LT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The research has been carried put within the PRIN research project entitled “Digitalized life-cycle management of historic bridges by an integrated monitoring and modelling CDE platform – HBridgeIM (Historic Bridge Information Modelling)” (Grant number 2022744YM9).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aigwi, I. E., Egbelakin, T., and Ingham, J. (2018). Efficacy of adaptive reuse for the redevelopment of underutilised historical buildings: towards the regeneration of New Zealand’s provincial town centres. Int. Journal Building Pathology Adaptation 36 (4), 385–407. doi:10.1108/ijbpa-01-2018-0007

AL-shimmery, B. M., and Al-Ali, S. S. (2022). Potentials of built Heritage as opportunities for sustainable investments. ISVS E-Journal 9 (4), 202–219.

Arfa, F. H., Lubelli, B., Zijlstra, H., and Quist, W. (2022). Criteria of “effectiveness” and related aspects in adaptive reuse projects of heritage buildings. Sustainability 14 (3), 1251. doi:10.3390/su14031251

Ashworth, G. J. (2002). Conservation designation and the revaluation of property: the risk of heritage innovation. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 8 (1), 9–23. doi:10.1080/13527250220119901

Barral, V. (2012). Sustainable development in international law: nature and operation of an evolutive legal norm. Eur. J. Int. Law 23 (2), 377–400. doi:10.1093/ejil/chs016

Bedate, A., Herrero, L. C., and Sanz, J. Á. (2004). Economic valuation of the cultural heritage: application to four case studies in Spain. J. Cult. Herit. 5 (1), 101–111. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2003.04.002

Bottero, M., D’Alpaos, C., and Oppio, A. (2019). Ranking of adaptive reuse strategies for abandoned industrial heritage in vulnerable contexts: a multiple criteria decision aiding approach. Sustainability 11 (3), 785. doi:10.3390/su11030785

Bullen, P. A., and Love, P. E. (2011). Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings. Struct. Survey 29 (5), 411–421. doi:10.1108/02630801111182439

Conejos, S., Langston, C., Chan, E. H., and Chew, M. Y. (2019). “Governance of heritage buildings: australian regulatory barriers to adaptive reuse,” in Building governance and climate change (London: Routledge), 160–171.

De Silva, D., and Perera, K. (2016). Barriers and challenges of adaptive reuse of buildings. Inst. Quantity Surv. Sri Lanka Annual Technical Sessions, 3–4.

Della Spina, L. (2021). Cultural heritage: a hybrid framework for ranking adaptive reuse strategies. Buildings 11 (3), 132. doi:10.3390/buildings11030132

Della Spina, L., Carbonara, S., Stefano, D., and Viglianisi, A. (2023). Circular evaluation for ranking adaptive reuse strategies for abandoned industrial heritage in vulnerable contexts. Buildings 13 (2), 458. doi:10.3390/buildings13020458

Dell’Anna, F. (2022). What advantages do adaptive industrial heritage reuse processes provide? An econometric model for estimating the impact on the surrounding residential housing market. Heritage 5 (3), 1572–1592. doi:10.3390/heritage5030082

Djebbour, I., and Biara, R. W. (2020). The challenge of adaptive reuse towards the sustainability of heritage buildings. Int. J. Conservation Sci. 11 (2), 519–530.

Ferretti, V., Bottero, M., and Mondini, G. (2014). Decision making and cultural heritage: an application of the multi-attribute value Theory for the reuse of historical buildings. J. Cultural Heritage 15 (6), 644–655. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2013.12.007

Forbes, S. (2021). Towards a new valuation model for heritage building assets. Doctoral dissertation, PhD thesis. University of Portsmouth.

Foster, G., and Saleh, R. (2021). The circular city and adaptive reuse of cultural heritage index: measuring the investment opportunity in Europe. Resour. Conservation Recycl. 175, 105880. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105880

Fusco Girard, L., and Gravagnuolo, A. (2025). Adaptive reuse of cultural heritage: circular business, financial and governance models. Springer Nature, 588.

Guzman, P. C., Pereira Roders, A., and Colenbrander, B. J. F. (2017). Measuring links between cultural heritage management and sustainable urban development: an overview of global monitoring tools. Cities 60, 192–201. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2016.09.005

Ikiz Kaya, D., Pintossi, N., and Dane, G. (2021). An empirical analysis of driving factors and policy enablers of heritage adaptive reuse within the circular economy framework. Sustainability 13 (5), 2479. doi:10.3390/su13052479

International Platform on Sustainable Finance (2023). Strengthening clarity in social finance: scaling up social bonds.

Locurcio, M., Di Liddo, F., Morano, P., Tajani, F., and Tatulli, L. (2025). A methodological proposal for determining environmental risk within territorial transformation processes. Real Estate 2 (2), 5. doi:10.3390/realestate2020005

Lupacchini, R., and Gravagnuolo, A. (2019). Cultural heritage adaptive reuse: learning from success and failure stories in the city of Salerno, Italy. BDC. Boll. Del Cent. Calza Bini 19 (2), 353–377. doi:10.6092/2284-4732/7273

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., et al. (2015). Prisma-P group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Reviews 4, 1–9. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Moreschini, L. (2003). Metodi di valutazione economica di beni pubblici culturali Department of economics S. Cognetti De Martiis Working Paper Series. University of Turin.

Othman, A. A. E., and Mahmoud, N. A. (2022). Public-private partnerships as an approach for alleviating risks associated with adaptive reuse of heritage buildings in Egypt. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 22 (9), 1713–1735. doi:10.1080/15623599.2020.1742626

Ott, C., and Hahn, J. (2018). Green pay off in commercial real estate in Germany: assessing the role of super trophy status. J. Prop. Invest. & Finance 36 (1), 104–124. doi:10.1108/jpif-03-2017-0019

Pedersen, A. (2002). Managing tourism at world heritage sites: a practical manual for world Heritage site managers. Paris: UNESCO.

Pintossi, N., Ikiz Kaya, D., and Pereira Roders, A. (2021). Assessing cultural heritage adaptive reuse practices: multi-scale challenges and solutions in Rijeka. Sustainability 13 (7), 3603. doi:10.3390/su13073603

Pintossi, N., Kaya, D. I., Van Wesemael, P., and Roders, A. P. (2023). Challenges of cultural heritage adaptive reuse: a stakeholders-based comparative study in three European cities. Habitat Int. 136, 102807. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2023.102807

Rizzo, I., and Throsby, D. (2006). Cultural heritage: economic analysis and public policy. Handb. Econ. Art Cult. 1, 983–1016. doi:10.1016/S1574-0676(06)01028-3

Romão, X., Paupério, E., and Pereira, N. (2016). A framework for the simplified risk analysis of cultural heritage assets. J. Cult. Herit. 20, 696–708. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2016.05.007

Rossitti, M., Oppio, A., and Torrieri, F. (2021). The financial sustainability of cultural heritage reuse projects: an integrated approach for the historical rural landscape. Sustainability 13 (23), 13130. doi:10.3390/su132313130

Savoie, É., Sapinski, J. P., and Laroche, A. M. (2025). Key factors for revitalising heritage buildings through adaptive reuse. Build. & Cities 6 (1). doi:10.5334/bc.495

Shipley, R., Utz, S., and Parsons, M. (2006). Does adaptive reuse pay? A study of the business of building renovation in Ontario, Canada. Int. Journal Heritage Studies 12 (6), 505–520. doi:10.1080/13527250600940181

Stas, N. (2007). The economics of adaptive reuse of old buildings: a financial feasibility study & analysis. Waterloo: University of Waterloo.

Wilkinson, S. J., Remøy, H., and Langston, C. (2014). Sustainable building adaptation: innovations in decision-making. John Wiley & Sons.

Yung, E. H., and Chan, E. H. (2012). Implementation challenges to the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings: towards the goals of sustainable, low carbon cities. Habitat International 36 (3), 352–361. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2011.11.001

Zeadat, Z. F. (2024). Adaptive reuse challenges of Jordan’s heritage buildings: a critical review. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 16 (1), 95–107. doi:10.1080/19463138.2024.2329661

Keywords: heritage, asset, investment, factors, barriers, cultural, private operators, decision-making

Citation: Di Liddo F, Locurcio M, Morano P and Tatulli L (2025) Identification of a set of key aspects for heritage assets investments to support private operators in the decision-making processes. Front. Built Environ. 11:1717195. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2025.1717195

Received: 01 October 2025; Accepted: 01 December 2025;

Published: 18 December 2025.

Edited by:

Assed N. Haddad, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, BrazilReviewed by:

Xiaoyong Yin, Tsinghua University, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Di Liddo, Locurcio, Morano and Tatulli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marco Locurcio, bWFyY28ubG9jdXJjaW9AcG9saWJhLml0

Felicia Di Liddo

Felicia Di Liddo Marco Locurcio

Marco Locurcio Pierluigi Morano

Pierluigi Morano Laura Tatulli

Laura Tatulli