- 1Department of Community Health Sciences, Max Rady College of Medicine, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

- 2Faculty of Social Work, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Max Rady College of Medicine, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic had significant impacts on youth health and well-being. Youth with prior inequities, such as those exposed to child maltreatment, may have experienced greater psychosocial challenges and long-term difficulties than their peers, including sustained interpersonal relationships problems. Given the importance of healthy relationships during adolescence and early adulthood, the significant impact the pandemic had on youth, and the potential disproportionate challenges for youth with a child maltreatment history, the purpose of the present study was to better understand changes in relational conflict among youth with and without a child maltreatment history from the perspectives of youth themselves. Specifically, the aims were to examine if youth child maltreatment history was associated with an increased likelihood of reporting increased conflict with (a) parents, (b) siblings, or (c) intimate partners during the first three years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: Data were drawn from the Well-Being and Experiences (WE) Study; a longitudinal and intergenerational cohort study of 1,000 youth/parent dyads in Manitoba, Canada that began in 2017. WE study data were collected annually via self-reported youth surveys between 2017 and 2022 for a total of 5 waves of data collection, and COVID-19 questions were included in Waves 3 (2020), 4 (2021) and 5 (2022) (n = 586, 56.43% female, ages 18 to 21 at Wave 5). Multinomial regressions models were computed to examine whether a youth's child maltreatment history was associated with increased, decreased, or consistent levels of conflict with parents, siblings, and intimate partners in 2020, 2021, and 2022 compared to pre-pandemic levels.

Results: Results indicated that compared to youth with no child maltreatment history, youth with a child maltreatment history were more likely to report increased conflict across all three types of relationships during first three years of the pandemic.

Discussion: Findings contribute to our understanding of the association between the COVID-19 pandemic and interpersonal relationships among youth who have a child maltreatment history compared to their peers without child maltreatment histories, signal potential long-term challenges or inequities for youth and families with a history of maltreatment, and may inform policy, programming, intervention, and recovery efforts in the post-COVID-19 period, and for future global emergencies.

Introduction

Disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic impacted youth globally (1, 2). Several studies reported increased mental health challenges, academic difficulties, employment and financial issues, and isolation for young people around the world (3–7). Certain key populations were at an even higher risk of experiencing difficulties, inequities or harm during the pandemic; among these were youth with child maltreatment experiences (6, 8–11). Child maltreatment is defined as any abuse or neglect that occurs before the age of 18 years, and includes physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, and exposure to intimate partner violence (EIPV) (12, 13). It is a prevalent and harmful public health issue that affects health and well-being throughout the life course (14–19). Physical health challenges include chronic headaches and migraines, back pain, fatigue, high blood pressure, obesity, stroke, respiratory issues, bowel disease, and cancer (20, 21). Psychological challenges include anxiety and depression, post-traumatic stress disorders, risk-taking behaviours, substance use problems, poorer quality of life, lower self-perceived health and well-being, and suicide (16, 22–27). Furthermore, children and youth who experience maltreatment are frequently exposed to multiple forms of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) (e.g., abuse, poverty, parental mental health challenges, school bullying) (23, 28–32), and the cumulative effects of multiple maltreatment and adversity exposures pose a great risk on child and youth outcomes, particularly given the critical developmental period during which these occur (16, 17, 26, 27, 31, 33).

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated difficulties for youth with child maltreatment histories. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, international past-year prevalence studies estimated that one billion children between 2 and 17 years old experienced physical, sexual, and emotional violence from adults and peers (34, 35). In Canada, pre-pandemic studies indicated that 32% of adults reported experiences of physical abuse, sexual abuse and/or EIPV during childhood or adolescence, 26.1% reported physical abuse experiences, 10.1% reported sexual abuse experiences, 7.9% reported EIPV (27), and 59.7% reported any type of child maltreatment experience before the age of 16 years old (36). Following the onset of COVID-19, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that 11% of youth experienced physical abuse and 55% experienced emotional abuse by a parent within the first year of the pandemic (10, 37). Violence against women (38), intimate partner violence (8, 39, 40), and online dating violence among teens also increased during the pandemic (40, 41). Sibling relationships may also have been affected, although the literature is limited and mixed, with some reporting increased closeness and others reporting increased tension (42–45). While some studies assessing family dynamics during pandemic “lockdown” periods indicated increased family cohesion (46, 47), for young people who were already experiencing abuse, neglect, or violence in their home, closer contact with the abuser, increased isolation, limited contact with social networks, and reduced detection or reporting of abuse may have risked worsening dangerous and vulnerable situations (5, 10, 37, 48–50). Parental job loss, financial challenges or poverty, overcrowding, and concerns of disease-related death or illness heightened parental distress and may also have been contributing factors (6, 8, 9, 37, 46, 48, 49, 51). Examining differences of the impact of COVID-19 among youth with and without maltreatment histories is needed to better understand potential discrepancies in experiences and long-term implications.

Interpersonal relationships are critical components of youth health and development that can either act as protective factors that buffer against stressors and mitigate other negative outcomes (40, 46, 47, 52), or as risk factors that further perpetuate negative outcomes (45, 52–54). Pre-pandemic studies established that child maltreatment increases the risk of interpersonal difficulties in adolescence and adulthood (53, 55), including dating violence victimization or perpetration (40, 52), poorer parent-child relationships, and future parenting practices (56). To date, pandemic-based studies have indicated that maltreatment increased the odds of experiencing educational and financial difficulties (7), alcohol and cannabis use (6), and anxious or depressed feelings (5, 57). Child maltreatment also may have had a moderating role between pandemic-related distress and well-being outcomes, including more internalized and externalized behaviours, and lower self-esteem and life satisfaction for youth with a child maltreatment history (11). In addition, youth who experienced negative impacts of COVID-19 on family and peer relationships were more likely to report lower life satisfaction and higher physical and psychological health complaints than youth who reported a neutral impact from the pandemic (58). However, less is known about the immediate and intermediate impacts of COVID-19 on relational conflict from the perspectives of youth with maltreatment histories in particular; many maltreatment studies to date have focused on younger children rather than adolescents or emerging adults (46, 47), have included proxies (e.g., parents or teachers) rather than youth, and have been retrospective and cross-sectional—which are subject to recall bias (5)—and did not specifically consider pre-existing maltreatment experiences on relationship outcomes.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations (UN) have projected that abuse prevalence may remain at higher than pre-pandemic levels (8, 10), which risks to further widen the gap between youth with a child maltreatment history and their peers. As such, longitudinal research capturing the impact of the pandemic on relationships from the perspectives of youth themselves is critical to identify patterns, understand potential long-term issues, and inform areas for policy, programs and interventions that are founded on youth voices (1, 5, 49, 59, 60). The purpose of the present study was to examine the association between the COVID-19 pandemic and relational conflict among youth with a child maltreatment history using longitudinal self-reported youth surveys. Specific aims were to examine whether youth with a child maltreatment history (i.e., abuse, neglect, and EIPV), had a higher risk of reporting increased conflict with parents, siblings, and intimate partners during the first three years of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020, 2021, 2022) compared to youth without a child maltreatment history. It was hypothesized that youth with a child maltreatment history would be at greater risk of reporting increased relational conflict during the pandemic across all types of relationships compared to their peers without a child maltreatment history.

Materials and methods

Data and sample

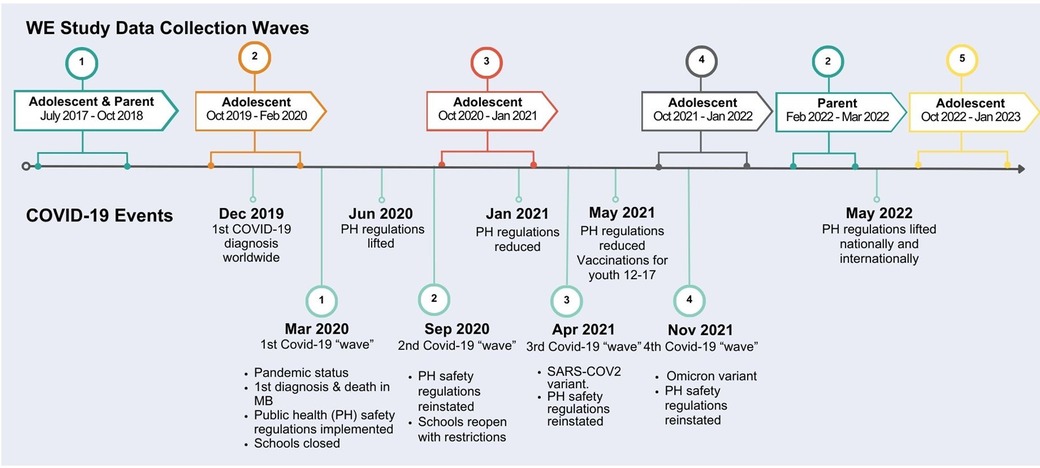

Data were drawn from the Well-being and Experiences (WE) study, a multi-wave community-based longitudinal, intergenerational cohort study of 1,000 youth-parent/caregiver dyads that began in 2017. Participants were recruited through random digit dialing and convenience sampling in Manitoba, Canada (15). At baseline (2017), youth participants were 14 to 17 years old (mean age = 15.3 years; 51.7% female), and closely approximated the population that lived in urban and rural areas of the province (i.e., Winnipeg and surrounding areas) based on sex, ethnicity, and household income. Youth completed these self-reported questionnaires annually between 2017 and 2022 for a total of 5 waves of data collection (Figure 1). Questionnaires were completed in person for Wave 1, then remotely for Waves 2 to 5. The WE study questionnaires included several questions on multiple aspects of physical and mental health, school, family and employment, intimate partner relationships, child maltreatment history, resilience, and protective factors. COVID-19 questions were included in Waves 3 (2020), 4 (2021) and 5 (2022). Due to reporting laws among minors, child maltreatment questions (childhood physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect) were included in surveys for youth 18 years and older (7, 61, 62). Responses from youth 18 years and older at Waves 3, 4, and 5 (n = 586) were therefore included in the present study analyses to examine COVID-specific responses. Participation in the study was voluntary; adolescents and parents provided informed consent and were aware that they could withdraw at any time. Individuals who participated in a survey were contacted via the email address that they had provided to participate in the next round of data collection. If they indicated that they were interested in participating, a link was emailed to them and the informed consent appeared when they first clicked on the link. If they provided informed consent, they proceeded to the online questionnaire, if they did not provide consent, the survey ended, and they were not contacted for future data collection waves. Ethics approval was provided from the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (15).

Figure 1. Timeline: well-being and experiences (WE) study data collection and COVID-19 events in Manitoba, Canada.

Measurement

Child maltreatment

Child maltreatment was assessed using the validated and reliable 28 item Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (61, 62). The CTQ is designed to assess childhood physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect, each of which are measured with five questions on a 5-point ordinal scale (never true to very often true) (61, 62). EIPV was assessed using the Childhood Experiences of Violence Questionnaire (CEVQ) which asks participants to report how many times they saw or heard any one of their parents, step-parents or guardians hit each other or another adult in their home before the age of 16 (63); response options included (1) Never, (2) 1 or 2 times, (3) 3 to 5 times, (4) 6 to 10 times, (5) 11 to 20 times, (6) More than 20 times, (7) I don't know, or (8) No response. Responses to the CTQ and CEVQ were coded as binary (yes/no) with different cut-off scores for each type of abuse (physical abuse cut-off score of eight or above; sexual abuse, six or above; emotional abuse, 13 or above; emotional neglect, 15 or above; physical neglect, eight or above; and EIPV, three or above); cut-off scores were determined based on guidelines provided by the original tool developers Bernstein et al. (61) and used in previous studies (61, 62, 64). Each type of abuse was then added together to create an overall child maltreatment composite variable of “yes” (exposure to one or more types of child maltreatment) vs. “no” (no child maltreatment exposure) (Table 1).

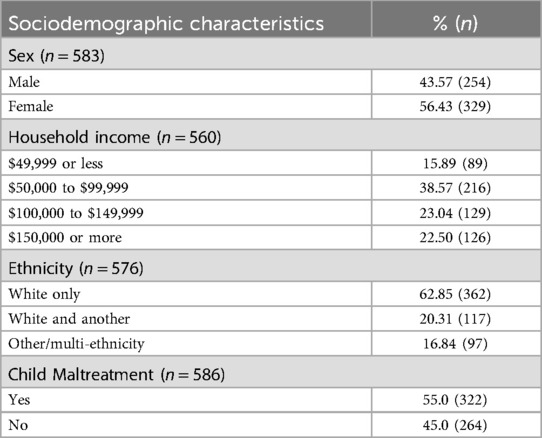

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics and child maltreatment responses among youth 18 to 21 years old at Waves 3, 4, and 5 of data collection.

Conflict with parents, siblings, and intimate partners during COVID-19

In the interest of time and in order to capture impacts of the pandemic as it progressed, the following three questions were developed by the research team and added to the WE questionnaires in 2020, 2021, and 2022: “Has conflict with your parents changed due to the COVID-19 pandemic?”, “Has conflict with your siblings changed due to the COVID-19 pandemic?”, “Has conflict with a partner in an intimate relationship changed due to the COVID-19 pandemic?”. Participant response options included (1) Increased, (2) Remained the same, (3) Decreased, (4) I don't know, (5) No response. These three repeated measure questions were used in the study analyses to assess changes in relational conflict with parents, siblings, and intimate partners.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic variables measured at baseline (Wave 1) were used as covariates in the adjusted models and included biological sex (male or female), household income and ethnicity. Sex and ethnicity were assessed at baseline on the youth questionnaire. Ethnicity included three categories: White only, white and other, and other/multi-ethnicity. Information on household income was provided by the parent respondent at baseline and included four options: $49,999 or less, $50,000 to $99,999, $100,000 to $149,999, and $150,000 or more.

Analyses

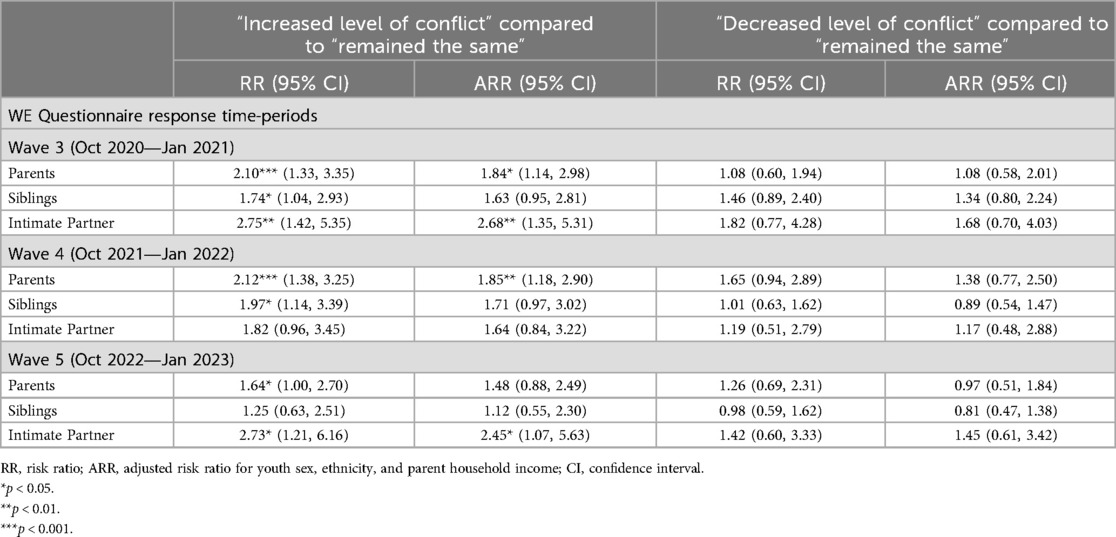

Descriptive analyses were conducted for youth sociodemographic factors including youth sex, ethnicity, household income, and child maltreatment history (Table 1). Multinomial regressions (Table 2) were conducted to examine whether there were associations between youth child maltreatment history (independent variable) and conflict with parents, siblings, intimate partners during the COVID-19 pandemic (dependent variables) in 2020, 2021, and 2022. Child maltreatment responses were dichotomized (no = no child maltreatment; yes = 1 or more types of child maltreatment exposure), and three levels were used to assess change in conflict with parents, siblings, and intimate partner relationships: increased conflict, decreased conflict, or remained the same (reference category). Participants who indicated that they did not have siblings or were not in a relationship at the time of the survey were not included in the analyses for that given Wave of data collection. Responses from youth with a child maltreatment history were compared to those without a child maltreatment history to determine whether responses among these two groups were significantly different from one another. Significance levels of 95% (p < 0.05), 99% (p < 0.01) and 99.99% (p < 0.001) were used to examine whether responses among youth with a child maltreatment history were significantly different from youth with no child maltreatment history. Each wave of data collection was examined independently from one another, in separate models. Regressions were first conducted unadjusted, then adjusted for youth sex, ethnicity, and household income. Study analyses were conducted using STATANow17 software (65).

Table 2. Multinomial regression results for conflict during COVID-19 among youth with a child maltreatment history, compared to youth with no child maltreatment history.

Results

A total of 586 participants 18 to 21 years old (at Wave 5) were included in the analyses. Among them, 56.43% were female, 15.89% had a family income of $49,999 or less, and over half (55%) reported having experienced maltreatment in their childhood or adolescence (Table 1). Multinomial regression models presented in Table 2 indicated whether youth reported changes to levels of conflict throughout the pandemic. In the first year of the pandemic (2020—Wave 3 of the WE study data collection), youth with a child maltreatment history compared to those without a child maltreatment history were significantly more likely to report increased conflict with parents (RR = 2.10; 95% CI 1.33 to 3.35), siblings (RR = 1.74; 95% CI: 1.04 to 2.93) and intimate partners (RR = 2.75; 95% CI 1.42 to 5.35) in the unadjusted model. Increased conflict with parents (ARR = 1.84; 95% CI 1.14 to 2.98) and intimate partners (ARR = 2.68; 95% CI 1.35 to 5.31) remained significant after adjusting for sex, ethnicity and household income, and conflict with siblings was on the margin of significance (ARR = 1.63; 95% CI 0.95 to 2.81). In the second year of the pandemic (2021—Wave 4 of the study), youth with a child maltreatment history compared to youth without a child maltreatment history were more likely to report increased levels of conflict with parents in the unadjusted (RR = 2.12; 95% CI 1.38 to 3.25) and adjusted models (ARR = 1.85; 95% CI 1.18 to 2.90) and with siblings (RR = 1.97; 95% CI 1.14 to 3.39) in the unadjusted model. Conflict with siblings was not significant in the adjusted model and intimate partners was not significant in either unadjusted or adjusted models. In the third year of the pandemic (2022—Wave 5 of the study), youth with a child maltreatment history continued to report significantly more conflict with parents in the unadjusted model (RR = 1.64; 95% CI 1.00 to 2.70) compared to youth without a child maltreatment history; this was no longer significant in the adjusted model. Increased conflict with intimate partners was significant in both the unadjusted (RR = 2.73; 95% CI 1.21 to 6.16) and adjusted models (ARR = 2.45; 95% CI 1.07 to 5.63) at Wave 5. Conflict with siblings was not significantly different from youth without a child maltreatment history in the third year of the pandemic in either unadjusted or adjusted models. Significantly decreased levels of conflict with parents, siblings, or intimate partners were not observed at any point in the data collection during the pandemic.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic had significant impacts on youth health and well-being (2, 6, 66). Youth with prior inequities, such as those with a child maltreatment history, may have experienced greater psychosocial challenges than their peers (6, 10, 50, 67), and such issues may contribute to long-term difficulties including sustained interpersonal relationships problems with family and intimate partners (1, 52, 56). Given the importance of healthy relationships during adolescence and early adulthood, and the significant disruption of the pandemic on youth lives, the purpose of this study was to better understand changes to levels of relational conflict with parents, siblings, and intimate partners from the perspectives of youth with and without a child maltreatment history.

Conflict by year of data collection

Year 2020

In the first year of the pandemic and following the onset of public health regulations, including lockdowns, school closures, and stay-at-home directives in Manitoba (Figure 1), youth participants with a child maltreatment history were significantly more likely than youth without a child maltreatment history to report increased conflict with their parents, siblings and intimate partners during the pandemic compared to prior to the pandemic. When adjusting for sex, ethnicity and household income, significant results remained for increased conflict with parents and intimate partners, and conflict with siblings was trending towards significance.

Year 2021

In 2021, public health regulations changed frequently, shifting from several, to few restrictions numerous times throughout the year. During this time, youth with a child maltreatment history—compared to youth without a child maltreatment history—continued to report significantly more conflict compared to pre-pandemic conflict with their siblings (unadjusted model) and their parents (unadjusted, and adjusted models), but not with intimate partners.

Year 2022

By April 2022, most restrictions were lifted in Manitoba; schools, workplaces, healthcare services and extracurricular activities had re-opened, and youth were once again able to socialize in person. At this time, despite an overall “return to normal”, youth with a child maltreatment history were still significantly more likely than youth who did not have a child maltreatment history to report increased conflict with parents (unadjusted) and with intimate partners (unadjusted and adjusted models) when compared to pre-pandemic levels, but not with siblings.

Conflict by type of relationship

Siblings

Results indicated that conflict with siblings was more pronounced at the beginning of the pandemic (2020) but was no longer significantly different for youth with and without a child maltreatment history by the end of the study period (2022). Given that this study included participants in later adolescence and early adulthood, it is possible that these individuals had moved out of their home or away from their siblings by 2022. This may explain some of the reduction in conflict between siblings, however, we do not have information on how living arrangement changed over the pandemic, so this is speculative. There are few studies specifically considering changes to sibling relationship quality during the pandemic, and the results are varied, with some indicating increased closeness during lockdown periods, and others indicating increased tension (42, 43). Sibling relationships are especially important during adolescence as these may be protective against other adversity, or may worsen outcomes depending on the quality of the relationship (42, 43, 45). The present study findings therefore highlight the importance of considering abuse histories within the examination of sibling relationships during and following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Parents

Conflict with parents remained significantly higher than pre-pandemic levels for youth with a child maltreatment history at each wave of data collection (2020, 2021, 2022) in the unadjusted models and was significant in 2020 and 2021 in the adjusted models. Youth who did not have a history of child maltreatment did not report significant increases in conflict with parents at any point of data collection. Adolescent conflict with parents is considered a normative part of individuation at this stage of development, however some COVID-19 studies had indicated potential benefits for family cohesion during the pandemic, such as closer bonds and more quality time spent together (45–47). The fact that the present study results found increased parent-youth conflict only within families with a child maltreatment history is therefore an important finding as this may be indicative of distinct and possibly persistent parent-child relationship problems for these families in particular.

Intimate partners

Conflict with intimate partners was significantly higher than pre-pandemic levels in 2020 and 2022 but was not significant in 2021. Participants were not asked to indicate the length of their intimate partner relationships nor whether they were with the same or different partner when participating in each wave of data collection. Study results may therefore reflect changes to intimate partner relationships from the onset of COVID-19 (e.g., youth relationships ending or having less contact after the first lock-down), may indicate momentary reduction of stressors or increased sense of hopefulness (e.g., several local restrictions lifted in 2021, vaccinations became increasingly available), or may be the result of a Type II error due to low statistical power as noted by moderate effect sizes and wider confidence intervals. Other studies examining adolescent dating relationships during COVID-19 had mixed results related to intimate partner relationships, with some reporting increased bonds or closeness, and others reporting increased violence (39–42). In the present study, relationships with intimate partners continued to be reported as more conflictual in 2022 than pre-pandemic levels among youth with a child maltreatment history, and not among those without a child maltreatment history, which may suggest ongoing or increasing issues, either in pre-existing relationships, or new relationships; this is of concern and worth further investigation given the increased rates of overall dating violence and intimate partner violence since the onset of COVID-19 (8, 38–41).

Overall, of prime importance is the fact that youth with a child maltreatment history had significantly different results (i.e., increased conflict) than youth without a child maltreatment history as this identifies disproportionate pandemic-related experiences or inequities for youth who have experienced maltreatment. Furthermore, conflict among youth with a child maltreatment history remained significantly higher in 2022 after most restrictions had been lifted, which suggests potential long-term challenges that may widen gaps in health and psychosocial outcomes and identifies a need for early and ongoing supports. Additionally, youth with a child maltreatment history continued to report increased conflict with intimate partners in 2022, whereas youth without child maltreatment did not report increased conflict with an intimate partner at any point of data collection; this may signify worsening cycles or patterns of conflict or abuse within close intimate relationships as these youth enter adulthood and flags a critical area for intervention.

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

Many child maltreatment and pandemic-related studies focused on younger children, rather than youth, included proxies (e.g., parents or teachers) rather than capturing self-reported youth-experiences, and have been cross-sectional (i.e., a single time point) or conducted retrospectively (e.g., after the height of pandemic had passed), which may be subject to recall bias (4, 5, 10, 46, 47). Notable strengths of the current study are the longitudinal study design, conducted directly with youth (rather than proxies), using validated child maltreatment measures, as the COVID-19 pandemic progressed. The assessment of youth's interpersonal relationships at yearly intervals prior-to and during the first three years of COVID-19 reduced the potential of recall bias and captured changes in relational conflict that occurred throughout the pandemic (5). The study design also included youth with and without child maltreatment histories which made it possible to compare responses from these distinct population vantage points, therefore providing valuable information of youth's self-reported experiences throughout this significant point in history. Furthermore, examining changes in relationships with parents, siblings, and intimate partners during adolescence and early adulthood yielded important information about this critical developmental period. The study sample included a cohort who closely represented the youth population in the urban (Winnipeg) and rural areas of Manitoba at baseline. However, due to attrition, the sample used for the analyses may not be representative of the population from which it was drawn. Limited power may have contributed to reduced significance in the adjusted models, possibly resulting in some Type II errors. Although sex and gender differences may exist in interpersonal relationship patterns amongst youth with a child maltreatment history, it was not possible to examine sex or gender differences due to limited power. Furthermore, COVID-19 questions were developed by the research team; this was done in the interest of time, rather than spending time developing a tool, questions were created and added to the surveys to capture the impact of the pandemic as it evolved. Also, although longitudinal, it was not possible to determine causal relationships due to the limitation on how child abuse was assessed. Finally, data collection ended in 2022; given the potential patterns of increased conflict identified in this study, and the risk of future pandemics, ongoing assessments of interpersonal relationships among children, youth and young adults with a child maltreatment history is needed to better understand the long-term impacts of such global emergencies.

Despite these limitations, knowledge generated through this study contributes to our understanding of the association between the COVID-19 pandemic for youth with and without a child maltreatment history, emphasizing the critical and ongoing need for support for families with histories of abuse, neglect, or violence (52, 68). Appropriate supports or interventions can buffer against risk factors and promote protective factors in the face of adversity (5, 16, 30, 69, 70); without these, interpersonal issues and relationship patterns experienced or established during childhood and adolescence may persist into adulthood, impacting health and well-being, quality of intimate relationships, future parenting styles, personal safety, and overall quality of life (5, 10, 50, 56, 67). Supports may include policies and programs implement at the individual level (e.g., adolescent intimate partner violence prevention programs) (58), at the family level (e.g., parent/caregiver supports and educational programs; policies that support families that are at economic disadvantages) (8, 46, 47), at the school level (e.g., safer school programs and policies, peer to peer supports, mental health services for students, school personnel training for signs and impacts of child maltreatment on student well-being) (5, 58), at the community level (e.g., community health workers trained to identify and support communities with high prevalence of violence) (1), and at the clinical level (e.g., enhanced clinician ability to recognize and enquire about child maltreatment and relational conflict in a safe environment, and respond appropriately if interventions are needed) (71). Given the inequities for youth with a child maltreatment history and potential ongoing challenges “post”-pandemic, it is timely and necessary to continue to progress our knowledge, address the long-term impacts of the pandemic, prevent worsening inequities, and strengthen youths' relationships with others to promote health and well-being now and into the future.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic had significant impacts on youth health and well-being. Results from the present study contribute to our knowledge of the association between the COVID-19 pandemic and relational conflict among youth with a child maltreatment history. Youth with a child maltreatment history reported a greater likelihood of conflict with their parents, siblings, and intimate partners compared to youth without a child maltreatment history at the onset of the pandemic, and increased conflict remained significant in 2022 after most public health restrictions had ceased. The pandemic-related interpersonal challenges experienced by youth during a critical developmental life period may affect long-term biopsychosocial outcomes, leading to greater inequities for this population across the life course. Study results illustrated potential long-term challenges for youth with a child maltreatment history, compared to youth without child maltreatment experiences, and contribute to the knowledge of early and ongoing pandemic-related issues for this population. Ongoing research and supports for youth and families with maltreatment experiences is necessary at this point in history to prevent worsening outcomes and promote well-being for all.

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: Data sharing is not permitted by the study ethics agreement. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to Tracie Afifi,dHJhY2llLmFmaWZpQHVtYW5pdG9iYS5jYQ==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

JM: Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AO: Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. TT: Writing – review & editing. AS-T: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Methodology. TA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. TA is supported by a Tier I Canada Research Chair in Childhood Adversity and Resilience. This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Operating Grant: Understanding and mitigating the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children, youth, and families in Canada.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the parents and adolescents who participated in the Well-being and Experiences Study and took the time to share their experiences for this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. United Nations Children’s Fund. The State of the World’s Children 2021: On My Mind—promoting, Protecting and Caring for Children’s Mental health. New York, United States: UNICEF (2021).

2. World Health Organization (WHO). Mental Health and COVID-19: Early Evidence of the Pandemic’s Impact. Geneva: World Health Organization (2022).

3. Statistics Canada. The Social and Economic Impacts of COVID-19: A six Month Update. Presentation Series from Statistics Canada About the Economy, Environment and Society. October 20 ed. Canada: Data for a better Canada (2020). p. 8.

4. Magson NR, Freeman JYA, Rapee RM, Richardson CE, Oar EL, Fardouly J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Youth Adolesc. (2021) 50:44–57. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9

5. Vaillancourt T, Szatmari P, Georgiades K, Krygsman A. The impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of Canadian children and youth. Facets. (2021) 6:1628–48. doi: 10.1139/facets-2021-0078

6. Salmon S, Taillieu TL, Fortier J, Stewart-Tufescu A, Afifi TO. Pandemic-related experiences, mental health symptoms, substance use, and relationship conflict among older adolescents and young adults from Manitoba, Canada. Psychiatry Res. (2022) 311:114495. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114495

7. Afifi TO, Salmon S, Taillieu T, Pappas KV, McCarthy J-A, Stewart-Tufescu A. Education-Related COVID-19 difficulties and stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic among a community sample of older adolescents and young adults in Canada. Educ Sci. (2022) 12:500. doi: 10.3390/educsci12070500

8. World Health Organization (WHO). Global status Report on Preventing Violence Against Children 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization (2020).

9. World Health Organization (WHO). Joint Leader’s Statement—violence Against Children: A Hidden Crisis of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Geneva: World Health Organization (2020). p. 2.

10. Park WJ, Walsh KA. COVID-19 and the unseen pandemic of child abuse. BMJ Paediatr Open. (2022) 6:e001553. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2022-001553

11. Dion J, Hamel C, Clermont C, et al. Changes in Canadian adolescent well-being since the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of prior child maltreatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:10172. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191610172

13. UNICEF. Violence: Children from al walks of life endure violence, and millions more at risk. (2023). Available online at: https://data.unicef.org/topic/violence/ (accessed November 20, 2023).

14. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med. (1998) 14:245–58. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

15. Afifi TO, Taillieu T, Salmon S, et al. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), peer victimization, and substance use among adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. (2020) 106:104504. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104504

16. Asmundson GJG, Afifi TO. Adverse Childhood Experiences: Using Evidence to Advance Research, Practice, Policy, and Prevention. London: Academic Press (2020).

17. Masten AS, Wright MOD. Cumulative risk and protection models of child maltreatment. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. (1998) 2:7–30. doi: 10.1300/J146v02n01_02

18. Afifi TO, Taillieu TL, Salmon S, Stewart-Tufescu A, Struck S, Fortier J, et al. Protective factors for decreasing nicotine, alcohol, and cannabis use among adolescents with a history of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Int J Mental Health Addict. (2023) 21(4):2255–73. doi: 10.1007/s11469-021-00720-x

19. Merrick MT, Ports KA, Ford DC, Afifi TO, Gershoff ET, Grogan-Kaylor A. Unpacking the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult mental health. Child Abuse Negl. (2017) 69:10–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.016

20. Afifi TO, MacMillan HL, Boyle M, Cheung K, Taillieu T, Turner S, et al. Child abuse and physical health in adulthood. Health Rep. (2016) 27:10–8.26983007

21. Mehta D, Kelly AB, Laurens KR, Haslam D, Williams KE, Walsh K, et al. Child maltreatment and long-term physical and mental health outcomes: an exploration of biopsychosocial determinants and implications for prevention. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. (2023) 54:421–35. doi: 10.1007/s10578-021-01258-8

22. Herrman H, Stewart DE, Diaz-Granados N, Berger EL, Jackson B, Yuen T. What is resilience? Can J Psychiatry. (2011) 56:258–65. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600504

23. Sabri B, Hong JS, Campbell JC, Cho H. Understanding children and Adolescents’ victimizations at multiple levels: an ecological review of the literature. J Soc Serv Res. (2013) 39:322–34. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2013.769835

24. Chartier M, Brownell M, MacWilliam L, Valdivia J, Nie Y, Ekuma O, et al. The Mental Health of Manitoba’s Children. Winnipeg, MB: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (2016).

25. Virgo Planning and Evaluation Consultants Inc. Improving Acces and Coordination of Mental Health and Addictions Services: A Provincial Strategy for all Manitobans. Manitoba, Canada: Government of Manitoba (2018).

26. Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO world mental health surveys. Br J Psychiatry. (2010) 197:378–85. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499

27. Afifi TO, MacMillan HL, Boyle M, Taillieu T, Cheung K, Sareen J. Child abuse and mental disorders in Canada. CMAJ. (2014) 186:E324–332. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131792

28. Salmon S, Chartier M, Roos LE, Afifi TO. Typologies of child maltreatment and peer victimization and the associations with adolescent substance use: a latent class analysis. Child Abuse Negl. (2023) 140:106177. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106177

29. Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA, Hamby SL. Measuring poly-victimization using the juvenile victimization questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. (2005) 29:1297–312. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.06.005

30. Masten AS. Global perspectives on resilience in children and youth. Child Dev. (2014) 85:6–20. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12205

31. Hogye SI, Lucassen N, PW Jansen, Schuurmans IK, Keizer R. Cumulative risk and internalizing and externalizing problems in early childhood: compensatory and buffering roles of family functioning and family regularity. Adv Resilience Sci. (2022) 3:149–67. doi: 10.1007/s42844-022-00056-y

32. Stoddard SA, Whiteside L, Zimmerman MA, Cunningham RM, Chermack ST, Walton MA. The relationship between cumulative risk and promotive factors and violent behavior among urban adolescents. Am J Community Psychol. (2013) 51:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9541-7

33. Yongping Z, Yufang Z, Yueh-Ting L, Li C. Cumulative interpersonal relationship risk and resilience models for bullying victimization and depression in adolescents. Pers Individ Dif. (2020) 155:109706. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.109706

34. Hillis S, Mercy J, Amobi A, Kress H. Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: a systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics. (2016) 137:e20154079. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4079

35. World Health Organization (WHO). Violence against children. Epub ahead of print November 29, 2022.

36. Bader D, Frank K. What do we know about physical and non-physical childhood maltreatment in Canada? Special Issue: Economic and Social Reports. Statistics Canada (2023). Available online at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/36-28-0001/2023001/article/00001-eng.htm (accessed December 11, 2023).

37. Krause KH, Verlenden JV, Szucs LE, Swedo EA, Merlo CL, Niolon PH, et al. Disruptions to school and home life among high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic—adolescent behaviors and experiences survey, United States, January–June 2021. MMWR Suppl. (2022) 71:28–34. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su7103a5

38. UN Women. Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women. New York: UN Women Headquarters (2020). https://www.unwomen.org/en/where-we-are

39. Moffitt P, Aujla W, Giesbrecht CJ, Grant I, Straatman A-L. Intimate partner violence and COVID-19 in rural, remote, and northern Canada: relationship, vulnerability and risk. J Fam Violence. (2022) 37:775–86. doi: 10.1007/s10896-020-00212-x

40. Krause KH, DeGue S, Kilmer G, Niolon PH. Prevalence and correlates of non-dating sexual violence, sexual dating violence, and physical dating violence victimization among U.S. High school students during the COVID-19 pandemic: adolescent behaviors and experiences survey, United States, 2021. J Interpers Violence. (2023) 38:6961–6984. doi: 10.1177/08862605221140038

41. Sutton D, Burczycka M. Dating Violence Against Teens Aged 15 to 17 in Canada, 2009 to 2022. Canada: Statistics Canada (2024).

42. Murphy L, Bush KR. A systematic review of adolescents’ relationships with siblings, peers, and romantic partners during the COVID-19 lockdown. Curr Psychol (New Brunswick, N.J.). (2024) 43(27):23387–403. doi: 10.1007/s12144-024-05842-8

43. Cassinat JR, Whiteman SD, Serang S, Dotterer AM, Mustillo SA, Maggs JL, et al. Changes in family chaos and family relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from a longitudinal study. Dev Psychol. (2021) 57:1597–610. doi: 10.1037/dev0001217

44. Hughes C, Ronchi L, Foley S, Dempsey C, Lecce S, I-Fam Covid Consortium. Siblings in lockdown: international evidence for birth order effects on child adjustment in the Covid19 pandemic. Soc Devel. (2023) 32:849–67. doi: 10.1111/sode.12668

45. Martin-Storey A, Dirks M, Holfeld B, Dryburgh NSJ, Craig W. Family relationship quality during the COVID-19 pandemic: the value of adolescent perceptions of change. J Adolesc. (2021) 93:190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.11.005

46. Harms MB, Record J. Maltreatment, harsh parenting, and parent–adolescent relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Opin Psychol. (2023) 52:101637. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101637

47. Skinner AT, Godwin J, Alampay LP, Lansford JE, Bacchini D, Bornstein MH, et al. Parent-adolescent relationship quality as a moderator of links between COVID-19 disruption and reported changes in Mothers’ and young Adults’ adjustment in five countries. Dev Psychol. (2021) 57:1648–66. doi: 10.1037/dev0001236

48. The Globe and Mail and McGinn D. Experts seeing rise in family conflict during the pandemic. Epub ahead of print March 22, 2021.

49. United Nations. UN leads Call to Protect Most Vulnerable from Mental Health Crisis During and After COVID-19. New York: United Nations Department of Global Communications (DGC) News and Media Division (NMD) (2020). https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/05/1063882

50. Sinko L, He Y, Kishton R, Ortiz R, Jacobs L, Fingerman M. “The stay at home order is causing things to get heated up”: family conflict dynamics during COVID-19 from the perspectives of youth calling a national child abuse hotline. J Fam Violence. (2022) 37:837–46. doi: 10.1007/s10896-021-00290-5

51. Gadermann AC, Thomson KC, Richardson CG, Gagné M, McAuliffe C, Hirani S, et al. Examining the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on family mental health in Canada: findings from a national cross-sectional study. BMJ open. (2021) 11:e042871–e042871. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042871

52. Park S, Kim S-H. The power of family and community factors in predicting dating violence: a meta-analysis. Aggress Violent Behav. (2018) 40:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2018.03.002

53. Bland VJ, Lambie I, Best C. Does childhood neglect contribute to violent behavior in adulthood? A review of possible links. Clin Psychol Rev. (2018) 60:126–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.02.001

54. Weymouth BB, Fosco GM, Mak HW, Mayfield K, LoBraico EJ, Feinberg ME. Implications of interparental conflict for adolescents’ peer relationships: a longitudinal pathway through threat appraisals and social anxiety symptoms. Dev Psychol. (2019) 55:1509–22; 20190509. doi: 10.1037/dev0000731

55. Redd M. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Couple Relationships: Impacts on Relationship Quality and Partner Selection. Akron, OH: University of Akron (2017).

56. Greene CA, Haisley L, Wallace C, Ford JD. Intergenerational effects of childhood maltreatment: a systematic review of the parenting practices of adult survivors of childhood abuse, neglect, and violence. Clin Psychol Rev. (2020) 80:101891; 20200723. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101891

57. Salmon S, Taillieu TL, Stewart-Tufescu A, MacMillan HL, Tonmyr L, Gonzalez A, et al. Stressors and symptoms associated with a history of adverse childhood experiences among older adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic in Manitoba, Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. (2023) 43:27–39. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.43.1.03

58. Cosma A, Bersia M, Abdrakhmanova S, Badura P, Gobina I. Coping Through Crisis: COVID-19 Pandemic Experiences and Adolescent Mental Health and Well-being in the wHO European Region. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Young People’s Health and Well-being from the Findings of the HBSC Survey Round 2021/2022. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe (2023).

59. World Health Organization. Considerations for COVID-19 Surveillance for Vulnerable Populations. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021).

60. Slutkin G, Ransford C, Zvetina D. How the health sector can reduce violence by treating it as a contagion. AMA J Ethics. (2018) 20(1):47–55. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2018.20.1.nlit1-1801

61. Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the childhood trauma questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1997) 36:340–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012

62. Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. (2003) 27:169–90. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

63. Walsh CA, MacMillan HL, Trocmé N, et al. Measurement of victimization in adolescence: development and validation of the childhood experiences of violence questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. (2008) 32:1037–57. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.05.003

64. Afifi TO, Salmon S, Garcés I, Struck S, Fortier J, Taillieu T, et al. Confirmatory factor analysis of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among a community-based sample of parents and adolescents. BMC Pediatr. (2020) 20:178–178. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-02063-3

65. StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, Texas: StataCorp LLC (2021).

66. Mohanty J, Chokkanathan S, Alberton AM. COVID-19–related stressors, family functioning and mental health in Canada: test of indirect effects. Fam Relat. (2022) 71:445–62. doi: 10.1111/fare.12635

67. Trucco EM, Fava NM, Villar MG, Kumar M, Sutherland MT. Social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic impacts the link between child abuse and adolescent internalizing problems. J Youth Adolesc. (2023) 52:1313–24. doi: 10.1007/s10964-023-01775-w

68. United Nations Children’s Fund. The State of the World’s Children 2021: On My Mind—promoting, Protecting and Caring for Children’s Mental Health. New York, United States: UNICEF (2021).

69. Masten AS, Motti-Stefanidi F. Multisystem resilience for children and youth in disaster: reflections in the context of COVID-19. Advers Resil Sci. (2020) 1:95–106; 20200625. doi: 10.1007/s42844-020-00010-w

70. Afifi TO, Macmillan HL. Resilience following child maltreatment: a review of protective factors. Can J Psychiatry. (2011) 56:266–72. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600505

Keywords: child maltreatment (CM), adverse childhood experiences (ACES), COVID-19 pandemic, conflict, parent-youth relationships, sibling relationships, intimate partner relationships, youth & emerging adult well-being

Citation: McCarthy J-A, Osorio AM, Taillieu TL, Stewart-Tufescu A and Afifi TO (2024) The association between the COVID-19 pandemic and interpersonal relationships among youth with a child maltreatment history. Front. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 3:1434496. doi: 10.3389/frcha.2024.1434496

Received: 17 May 2024; Accepted: 14 November 2024;

Published: 29 November 2024.

Edited by:

Tracy Vaillancourt, University of Ottawa, CanadaReviewed by:

Rüdiger Christoph Pryss, Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg, GermanySawa Kurata, University of Fukui, Japan

Copyright: © 2024 McCarthy, Osorio, Taillieu, Stewart-Tufescu and Afifi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tracie O. Afifi, dHJhY2llLmFmaWZpQHVtYW5pdG9iYS5jYQ==

Julie-Anne McCarthy

Julie-Anne McCarthy Ana M. Osorio

Ana M. Osorio Tamara L. Taillieu1

Tamara L. Taillieu1 Tracie O. Afifi

Tracie O. Afifi