- 1Educational and Development Psychology, University of Paderborn, Paderborn, Germany

- 2Department of Educational Science, University of Paderborn, Paderborn, Germany

Support is a vital resource at every stage of development throughout the lifespan. In the mother-child relationship, the exchange of support is subject to change in relation to the tasks and framework conditions of the current phase of life. While values and norms typically include social expectations, attitudes summarize individual thoughts or feelings. During young adulthood and midlife, attitudes are particularly important for the mutual support between mothers and their adult children when there are no practical framework conditions, such as care needs, that necessitate support. This study uses social exchange theory to examine the mediating role of felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity as important attitudes in the well-known relation between mothers and their adult children receiving and giving support. The sample consisted of 598 German adults (aged 20–49, 55.2% female) and 577 mothers (aged 40–87) of these adults; both perspectives were taken into account. The results from the parallel mediation analyses, in which instrumental and emotional support were considered separately, showed a mediating effect of felt obligation on the instrumental support of adult children for their mothers. The emotional support received and given by the adults to their mothers was mediated by felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity. The received and given instrumental and emotional support of the mothers to their adult children was mediated by perceived mutual reciprocity. The relevance of the adults' and mothers' different attitudes regarding support later in life is discussed.

Introduction

Mothers and their offspring share a unique bond that is meaningful for both parties throughout life and is likely the longest one marked by support for one another (Szydlik, 2016). It has long been understood that formative social structures develop from this relationship, which are important for maintaining a psychological balance and shaping relationships with others over the entire lifespan (Freud, 1928). Balance in the exchange of support is relevant to the relationship dynamics between mothers and their children in different phases of life. During young adulthood and midlife, when both generations are practically independent of one another and no practical framework determines support (Baltes and Silverberg, 1994), attitudes are particularly important for eliciting reciprocating help. Attitudes are founded on personal experiences, beliefs, and feelings (Eaton et al., 2008), whereas internalized norms and values are founded on social rules firmly rooted in the society's value system and contain social expectations (Iommi, 2019). However, agreeing with social norms does not necessarily mean that these norms are applied to one's own behavior (Stein, 1992). Individual experiences or feelings may conflict with providing support to one's parents, even though the norm that one must assist aging parents may be ingrained in one's value system.

An attitude describes an internal relationship in the form of a mental representation, summarizes the evaluation of an object, and has a regulative effect on interactions (Eaton et al., 2008). Felt obligation (Stein, 1992) and perceived mutual reciprocity (Wintre et al., 1995) are important for mutual support in mother–child relationships. We describe perceived mutual reciprocity (Wintre et al., 1995) as an attitude, an internal relationship with an attachment figure who is perceived as a relative equal, and a balance between subjective autonomy and a lasting feeling of connection. As an attitude, felt obligation can be defined as a summarized evaluation of behavioral expectations arising from the mother–child relationship, such as the provision of support. However, when examining mutual support, prior research has frequently taken only one perspective into account, with only a few studies considering the relevant parties' perspectives (Sechrist et al., 2014). Therefore, we take both into account here.

In order to better understand the mechanisms that mediate the support between young to middle-aged adult children and their mothers, this study uses social exchange theory to examine the importance of attitudes for receiving and giving support in the mother–child relationship when no practical restrictions determine the support. Both the adult children's and mothers' perspectives are taken into account. The theoretical assumptions and relevant constructs are presented in the following discussion.

Social exchange theory includes considerations for the development of reciprocal relationships in cross-disciplinary contexts (Mitchell et al., 2012). Social relationships are described as an action–reaction system of exchange, applicable to social relationships in general and family relationships (Ahmad et al., 2023). A first-initiated action, such as a supportive behavior, of an individual toward a target person represents the beginning of a reciprocal exchange. The target person's attitude toward the action shapes the future development of the relationship. Consequently, a corresponding relationship results in a reciprocal reaction by the target person, such as giving support to the individual (Cropanzano et al., 2017). The exchange process, or the resources that are exchanged, influences the nature of the relationship between individuals (Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005).

The relationship between mothers and their children is characterized by a lifelong exchange of support, and support is embedded in the relationship's history. The most frequently exchanged forms of support are emotional and instrumental. While emotional support includes, for example, conversations, comfort, or help in times of emotional distress (Sommer and Buhl, 2018), instrumental support includes practical and material assistance, such as help with household chores (Swartz, 2009). As a result, social exchange relationships evolve based on the attitudes and reciprocity of the corresponding parties (Cropanzano et al., 2017). Perceived reciprocity is relevant to the stability of the social exchange relationship. Social relationships are fundamentally characterized by mutual dependence and reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960), as well as obligations (Blau, 1964).

The relationship between mothers and their adult children is unique. Mothers receive more support from their children compared to their fathers (Klaus, 2009). Adult children feel strongly obligated to their parents (Del Corso and Lanz, 2013); again, feelings of obligation are stronger toward mothers than toward fathers (Freeberg and Stein, 1996; Stein, 1992; Stein et al., 1998) and are particularly relevant in predicting support for mothers, but not for fathers (Buhl, 2008a,b). Therefore, the focus here is specifically on the mother–child relationship.

Our attitudes have a powerful impact on how we perceive and experience the world. They motivate and guide our behavior in a direction consistent with our attitudes. As a result, attitudes have an impact on how we interact with our environment (Eaton et al., 2008; Petty et al., 2023). It has long been known that attitudes contain evaluative, cognitive, affective, and behavioral components regarding an object (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1977) and are persistent over time (Eaton et al., 2008). Since attitudes are global and summarize an evaluation of an object, similar to norm perceptions (Stein, 1992), a certain attitude can exist without actually having to be applied to one's own behavior (Rucker, 2021). In contrast, an attitude toward a behavior can be understood as an evaluative reaction (Fishman et al., 2021). In predicting behavior, attitudes play a mediating role (Fishbein and Ajzen, 2009; Fishman et al., 2021). Thus, a person's attitude toward an object might affect how they react to it (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1977). The following sections discuss perceived mutual reciprocity (Wintre et al., 1995) and felt obligation (Stein, 1992) as attitudes in the context of social exchange theory.

Reciprocity, in general, refers to a mutual exchange of support. This requires the provision of support and an appropriate return (Brandt et al., 2008). The perception of reciprocity within family relationships has an impact on the exchange of support between generations (Schwarz et al., 2005). Regardless of whether the support was perceived or actually provided, it plays an important role in life satisfaction at every stage of adulthood (e.g., Siedlecki et al., 2013).

The exchange of support is initially asymmetrical in the mother–child relationship. During early childhood, the child is emotionally and instrumentally dependent on their caregiver. To develop autonomous functioning, individuals navigate the balance between independence and dependency throughout their lives within the framework of developmental tasks of the current phase of life. Forming an attachment relationship with the mother creates the basis for the development and experience of autonomy. Accordingly, autonomy develops through the connection in the mother–child bond (Baltes and Silverberg, 1994). In adolescence, the unilateral authority of parents is increasingly transformed into reciprocal structures, and aiming for a more symmetrical relationship model, this phase is characterized by equality, respect, and reciprocity (Wintre et al., 1995). According to the principle of the “support bank” (Antonucci, 1985), the growing child tries to approach symmetry in the mutual exchange of support by later reciprocating the support they received during childhood. The mother–child relationship is then perceived as relatively symmetrical in early adulthood (Buhl, 2008a). However, mothers provide unconditional support to their children well into old age (Fingerman et al., 2013), making it unlikely that actual symmetry is ever fully established. This has an impact on the dynamics of mother–child relationships, as well as on the experience of dependency and perception of reciprocity in the social exchange relationship. One could describe an “adult relationship” in which a symmetrical relationship model characterized by a deep bond is sought.

Accordingly, perceived mutual reciprocity describes a perceived balance between the subjective experience of autonomy and a lasting feeling of connectedness with an attachment figure as an inner relationship in terms of attitude. It is experienced in social exchange relationships in which individuals feel relatively equal and show mutual respect and acceptance (Wintre et al., 1995). When parents perceive their relationship with their growing children to be balanced, they are more satisfied with the relationship (Vogl-Bauer et al., 1999). The perception of equity is more important than an actual balanced supportive exchange for the way mothers perceive the relationship quality with their children (Sechrist et al., 2014). Adolescent children, by comparison, readily accept the support of their parents and experience satisfaction in the relationship, regardless of the experience of equity (Vogl-Bauer et al., 1999).

Middle-aged adults perceive reciprocity differently depending on the type of support they receive. Middle-aged daughters tend to perceive receiving more than giving in terms of instrumental support. However, when it comes to emotional support, they feel that they give more to their parents than they receive from them (Schwarz et al., 2005). Middle-aged adults emphasize that in their relationships with parents, reciprocity is based on a perceived balance and a sense of connectedness (Funk, 2011), so perceived mutual reciprocity (Wintre et al., 1995) also appears to play an important role in middle adulthood. To better understand the relevance of this construct in young to middle adulthood, testing the extent to which perceived mutual reciprocity (Wintre et al., 1995) influences parents' and adult children's willingness to support each other later in life is important.

Feelings of obligation are negotiated over the entire duration of family relationships and, therefore, in the mother–child relationship (Stein, 1992). Conditions, expectations, rules, and obligations are arranged in the context of social exchanges (Ahmad et al., 2023). Felt obligation refers to the negotiated expectations of appropriate behavior that are defined by the characteristics of the individual mother–child relationship (Stein, 1992). These include strong social expectations to provide support and maintain contact (Stein, 1992, 1993). Felt obligation is thus an attitude in the form of a summarized evaluation of behavioral expectations arising from the mother–child relationship. Felt obligation mediates support services (Sommer and Buhl, under review)1 and influences the relationship dynamics between mothers and their children. During childhood, parents feel obligated to care for and support their children who are still in need (Brandt and Szydlik, 2008). Later in life, when their parents require care, children report a strong sense of obligation to care for and support them (Luichies et al., 2019). In young adulthood and midlife, when both parties can pursue their own life goals independently, feelings of obligation are equally important for support between young to middle-aged adults and their parents, helping maintain a balance in this social exchange process. Adult children experience a stronger felt obligation when they receive support from their parents (Schoenert et al., under review)2. As a result, adults who feel strongly obligated to their parents are more supportive of them (Stein et al., 1998; Whitbeck et al., 1994) and provide more instrumental support to their parents (Stein et al., 1998). However, little is known about parents' felt obligation to their adult children (Stein, 2009). Theorizing and testing the extent to which felt obligation influences parents' willingness to support their children in adulthood is necessary.

Previous research has shown that attitudes are decisive for support in the mother–child relationship. Felt obligation (Stein, 1992) and perceived mutual reciprocity (Wintre et al., 1995) were found to be important for shaping relationships and guiding the exchange of support between mothers and their adult children. We define both as attitudes because they contain evaluative, cognitive, affective, and behavioral components toward an object. In the context of social exchange theory, attitudes toward a behavior are relevant (Cropanzano et al., 2017) as an evaluative reaction (Fishman et al., 2021). The mediating role of felt obligation (Stein, 1992) and perceived mutual reciprocity (Wintre et al., 1995) is tested when it comes to support in the mother–child relationship later in life.

Furthermore, the type of resource that is exchanged has important implications for social exchange relationships. As the most common resource in the mother–child relationship, emotional and instrumental support are exchanged. Previous studies (e.g., Schwarz et al., 2005) suggest differences between these two forms of support.

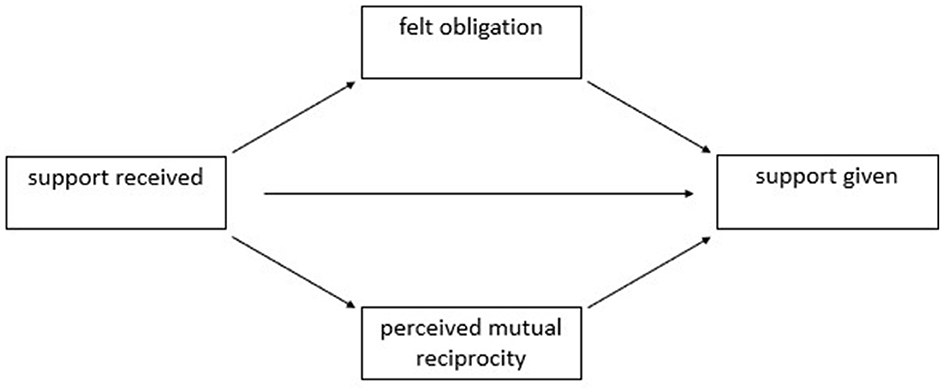

According to social exchange theory, a reciprocal exchange between mothers and their adult children begins with the support received. As guiding attitudes, felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity are important for further relationship formation. Consequently, as a reciprocal reaction, support is given to the corresponding party. Thus, we assumed a mediating effect of felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity as important attitudes regarding the association between receiving and giving support (Figure 1). The perspectives of mothers and adult children were considered separately, as were instrumental and emotional support. To investigate the assumed connection, four separate analyses were calculated to test the four following hypotheses:

H1. Felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity mediate the relationship between the instrumental support received and given by adult children to their mothers.

H2. Felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity mediate the relationship between the emotional support received and given by adult children to their mothers.

H3. Felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity mediate the relationship between the instrumental support received and given by mothers to their adult children.

H4. Felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity mediate the relationship between the emotional support received and given by mothers to their adult children.

Figure 1. Parallel mediation model. Note Assumed mediating effect of felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity on the relationship between receiving and giving support.

Materials and methods

Sample

Cross-sectional survey data from the “Interdependence in the Relationship between Adults and their Parents” project conducted in 2016/2017 and financed by the German Research Foundation were used for this study. The sample consisted of 598 adult children (55.2% female, 20–49 years, M = 33.69, SD = 6.16) and 577 mothers (40–87 years, M = 61.01, SD = 7.99) of these adult children. Social media, online portals, newspaper ads, and notices were used for recruitment. Participants who did not require care and lived in self-sufficient households were recruited. Participants came from throughout Germany. Data were collected anonymously, and participation was voluntary. The allowance was 10 € per participant; 40 € were awarded if both the parents and the adult child took part. This study only used data from mothers and adult children. The samples were dependent, as they were mother–child dyads. In the paper–pencil survey, the respondents were asked to self-report. All participants were included. The majority of the children were single (26.6%), in a relationship but not married (33.7%), or married (36.5%). At least once a week, 89.3% of the adults reported having contact with their mothers. Less than half (39.1 %) of the adults already had children of their own. In contrast, only 2.8% of mothers were single, 82.6% married, 10% divorced, and 4.6% widowed. The majority of mothers (89.7%) stated that they had contact with their children at least once a week.

Measurements

The study included self-reports from adult children and mothers. They responded to the items individually about each other.

Felt obligation

The felt obligation of young to middle-aged adults and their mothers was measured using the Felt Obligation Measure (Stein, 1992) adapted in German by Rieger and Buhl (2004). This measurement instrument included 5 scales mapped with 21 items. Participants were asked how often they felt they “should” or “must” do something (e.g., have regular contact, give as much as receive, talk about personal things, offer help and advice) in their mother–child relationship (αmother = 0.94, αchildren = 0.95). The options were ranked from 1 (never) to 5 (all the time) on a 5-point Likert scale.

Perceived mutual reciprocity

The Perception of Parental Reciprocity Scale (Wintre et al., 1995), in a German adaptation (Rieger and Buhl, 2004), was used to assess perceived mutual reciprocity (αchildren = 0.88, αmother = 0.85). It was to be answered on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (completely true). Items were, for example, “There is mutual respect between me and my mother/child, even in the areas where we disagree” and “My mother/child is comfortable expressing her doubts and fears with me.”

Instrumental support received

The instrumental support that adult children (αchildren = 0.85) received from their mothers and the instrumental support that mothers (αmother = 0.88) received from their adult children were measured using the same nine-item scale (Thönnissen et al., 2015; Winter, 2001). A 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always) was used to ask participants to rate the amount of assistance they had received in the previous 12 months.

Instrumental support given

The same scale with nine items was used to measure the instrumental support given by adult children (αchildren = 0.88) to their mothers and the instrumental support given by mothers (αmother = 0.86) to their adult children (Thönnissen et al., 2015; Winter, 2001). On a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (all the time), participants were asked to indicate what help they had given in the previous 12 months.

Emotional support received

The emotional support that adult children received from their mothers (αchildren = 0.92) and the emotional support that mothers (αmother = 0.92) received from their adult children were measured using an eight-item scale (Sommer and Buhl, 2018; Thönnissen et al., 2015). A 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always) was used to ask participants to rate the amount of help they had received in the previous 12 months.

Emotional support given

The same scale with eight items was used to measure the emotional support given by adult children (αchildren = 0.89) to their mothers and the emotional support given by mothers (αmother = 0.90) to their adult children (Sommer and Buhl, 2018; Thönnissen et al., 2015). On a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (all the time), participants were asked to indicate what help they had given in the previous 12 months.

Data analysis

A descriptive analysis of the data was conducted. Means, standard deviations, and correlations were calculated using IBM SPSS Statistics 29 for Windows. To test the hypothesized models for mothers and adult children, four parallel mediation analyses were performed using the PROCESS macro (version 4.3.1) for SPSS (Hayes, 2022). Sum scores were computed using the items for each measurement instrument. The parallel mediation analyses were based on a linear regression using the method of least squares and enabled the total and indirect effects to be examined, as well as the indirect effects of the two mediators to be compared. Model 4 was used to estimate the mediating effects of felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity on the association between received and given instrumental and emotional support for the adult children and the mother sample. Based on 5,000 bootstrap samples, 95% confidence intervals were estimated. The statistical significance of the indirect effects was assumed if the 95% confidence intervals did not contain the value of 0.

Results

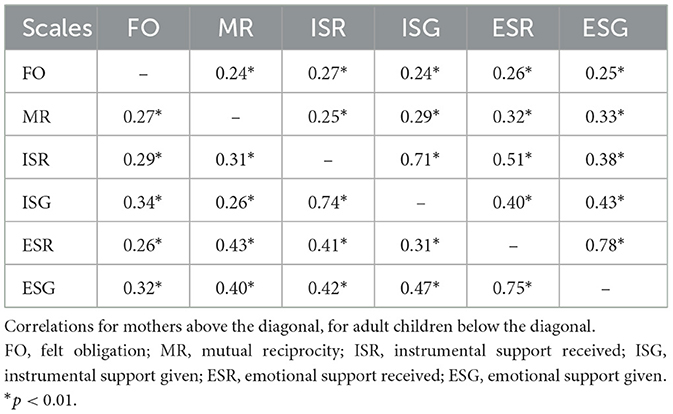

The means and standard deviations of the variables (Table 1) indicate a relatively high level of felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity in both the mother and adult children samples. The giving and receiving of emotional support were also rated as relatively high, whereas giving and receiving instrumental support tended to be rated as moderate by the participants in both samples.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations of all scales separately for mothers and their adult children.

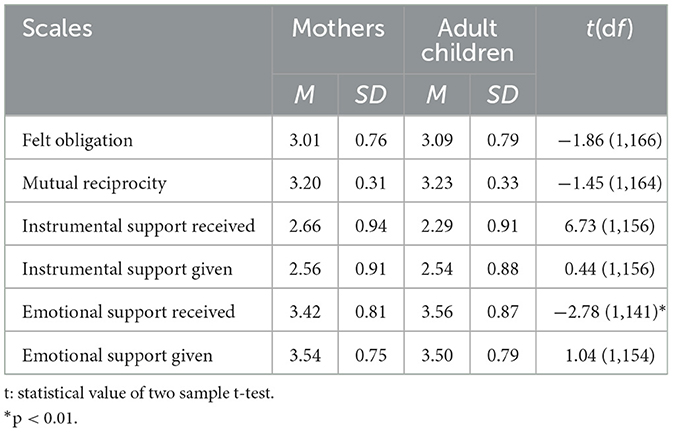

The correlations of the scales are shown in Table 2. All correlations were statistically significant. However, according to Cohen (1988), almost all correlations in both the mother (r = 0.24, p < 0.01, to r = 0.43, p = 0.01) and adult children's samples (r = 0.26, p<0.01, to r = 0.47, p = 0.01) can be interpreted as small to moderate. In both samples, the correlations between giving and receiving instrumental (mothers: r = 0.71, p < 0.01; children: r = 0.74, p = 0.01) and emotional support (mothers: r = 0.78, p < 0.01; children: r = 0.75, p = 0.01) are high. The correlation between receiving instrumental and emotional support in the mothers' sample is high (r = 0.51, p < 0.01) while in the adult children's sample, it can be interpreted as moderate to high (r = 0.41, p < 0.01). Both parties assessed the same facts, indicating a high level of agreement.

Parallel mediation analyses

To address the research questions, four parallel mediation models were established. The mediating effects of felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity on the association between the instrumental and emotional support received and given were investigated for young to middle-aged adult children and their mothers. The parallel mediation models 1 and 2 were estimated using data from adult children. The parallel mediation models 3 and 4 were constructed using the mothers' data.

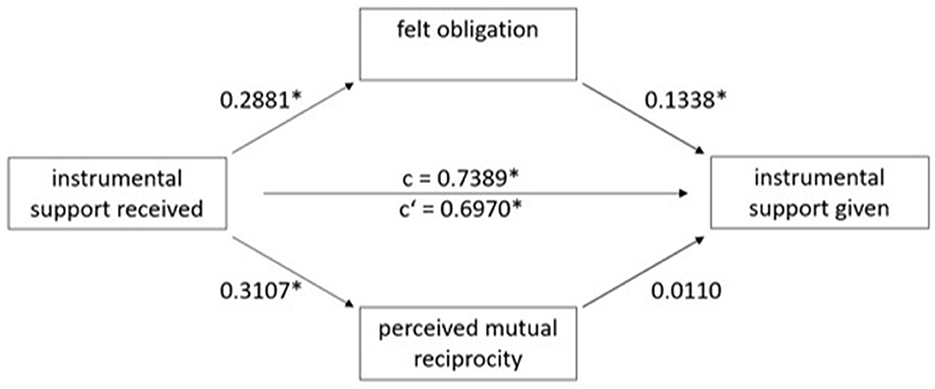

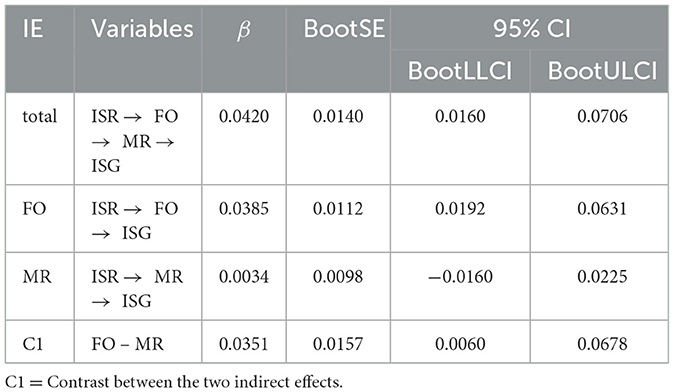

Hypothesis 1: The impact of felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity on the instrumental support received and given by adult children

Parallel mediation model 1 (Figure 2) examines the mediating effects of felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity on the association between the instrumental support received and given by adult children to their mother. The received instrumental support predicted the given instrumental support of adult children (βtotal = 0.7389, p < 0.01). When the mediators of felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity were included in the model, the received instrumental support of adult children from their mother predicted both felt obligation (β = 0.2881, p = 0.01) and perceived mutual reciprocity (β = 0.3107, p < 0.01). However, only felt obligation (β = 0.1338, p < 0.01) predicted the given instrumental support of adult children to their mother; perceived mutual reciprocity does not make a significant contribution here. The relationship between the instrumental support received and given is still significant after the mediators were added to the model (βdirect = 0.6970, p < 0.01). The standardized indirect effects are shown in Table 3. The total indirect effect showed a partial mediation (β = 0.0420, 95% CI [0.0160, 0.0706]). The indirect effect through felt obligation was statistically significant (β = 0.0112, 95% CI [0.0192, 0.0631]) but not through perceived mutual reciprocity. Accordingly, the effect (Table 3, C1) was significantly stronger through felt obligation than through perceived mutual reciprocity (β = 0.0351, 95% CI [0.0060, 0.0678]). Hypothesis 1, that both felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity mediate the relationship between the instrumental support received and given by adult children to their mothers, can be disconfirmed. Only felt obligation had a mediating effect. When adult children felt more obligated, they were more likely to express instrumental support.

Hypothesis 2: Impact of felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity on the emotional support received and given by adult children

Figure 2. Parallel mediation model 1 of received and given instrumental support through felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity of adult children. Note Data from adult children. Standardized effects are presented. c = total effect of received on given instrumental support; c' = direct effect of received on given instrumental support. *p < 0.01.

Table 3. Model 1: Standardized indirect effects (IE) of received (ISR) on given instrumental support (ISG) through felt obligation (FO) and perceived mutual reciprocity (MR) of adult children.

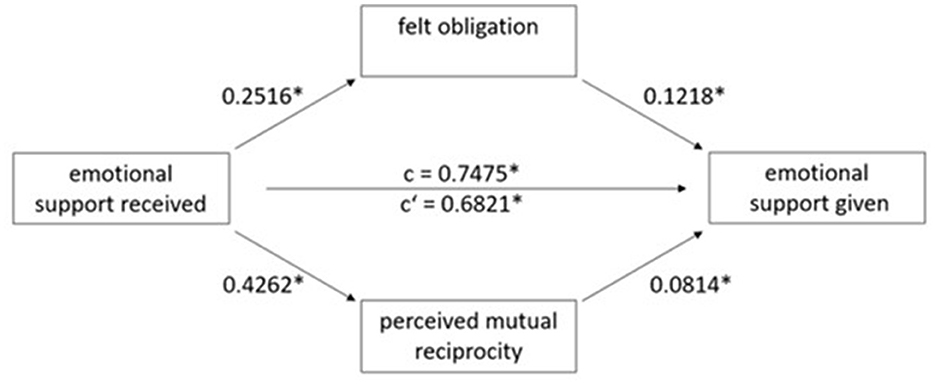

Parallel mediation model 2 (Figure 3) examines the mediating effects of felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity on the association between the emotional support received and given by the adult children to their mother. The received emotional support predicted the given emotional support of adult children (βtotal = 0.7475, p < 0.01). After the mediators felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity were included in the model, the received emotional support of adult children from their mother predicted both felt obligation (β = 0.2516, p = 0.01) and perceived mutual reciprocity (β = 0.4262, p < 0.01). Felt obligation (β = 0.1218, p < 0.01) and perceived reciprocity (β = 0.0814, p < 0.01), in turn, predicted the given emotional support of adult children to their mother. The relationship between the emotional support received and given is still significant after the mediators were added to the model (βdirect = 0.6821, p < 0.01).

Figure 3. Parallel mediation model 2 of received and given emotional support through felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity of adult children. Note Data from adult children. Standardized effects are presented. c = total effect of received on given instrumental support; c' = direct effect of received on given instrumental support. *p < 0.01.

The standardized indirect effects are shown in Table 4. The two mediators, felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity, partially mediated the relationship between the emotional support received and given by young to middle-aged adult children to their mothers, as the total indirect effect showed (β = 0.0653, 95% CI [0.0332, 0.0988]). There was a statistically significant indirect effect through felt obligation (β = 0.0306, 95% CI [0.0142, 0.0517]) and through perceived mutual reciprocity (β = 0.0347, 95% CI [0.0064, 0.0632]). The difference between the two mediation paths (Table 4, C1) was not significant (β = −0.0041, 95% CI [−0.0388, 0.0315]. Hypothesis 2, that felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity mediate the relationship between emotional support received and given by adult children to their mothers, can be confirmed. When adult children felt more obligated and perceived more mutual reciprocity in their relationship with their mothers, they were more likely to offer emotional support.

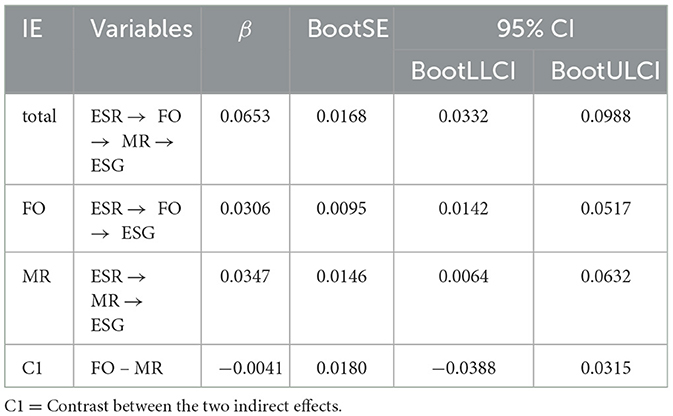

Hypothesis 3: The impact of felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity on the instrumental support received and given by mothers

Table 4. Model 2: Standardized indirect effects (IE) of received (ESR) on given emotional support (ESG) through felt obligation (FO) and perceived mutual reciprocity (MR) of adult children.

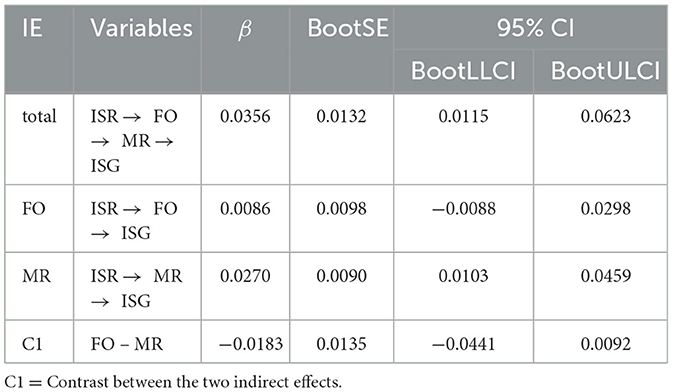

Parallel mediation model 3 (Figure 4) examines the mediating effects of felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity on the association between the instrumental support received and given by mothers to their adult children. The received instrumental support predicted the given instrumental support of the mothers (βtotal = 0.7090, p < 0.01). After the mediators felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity were included in the model the received instrumental support of the mothers from their adult children predicted both felt obligation (β = 0.2756, p < 0.01) and perceived mutual reciprocity (β = 0.2507, p < 0.01). However, only perceived mutual reciprocity (β = 0.1076, p < 0.01) predicted the given instrumental support of the mothers to their adult children; felt obligation did not make a significant contribution here. The relationship between the instrumental support received and given is still significant after the mediators were added to the model (βdirect = 0.6734, p < 0.01). The standardized indirect effects are shown in Table 5. The total indirect effect showed a partial mediation (β = 0.0356, 95% CI [0.0115, 0.0623]). The indirect effect through perceived mutual reciprocity was statistically significant (β = 0.0270, 95% CI [0.0103, 0.0459]) but not through felt obligation. The difference between the two mediation paths (Table 5, C1) was not significant (β = −0.0183, 95% CI [−0.0441, 0.0092]). Hypothesis 3, that both felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity mediate the relationship between the instrumental support received and given by mothers to their adult children, can be disconfirmed. Only perceived mutual reciprocity had a mediating effect. When mothers perceived more mutual reciprocity in their relationship with their adult children, they were more likely to express instrumental support.

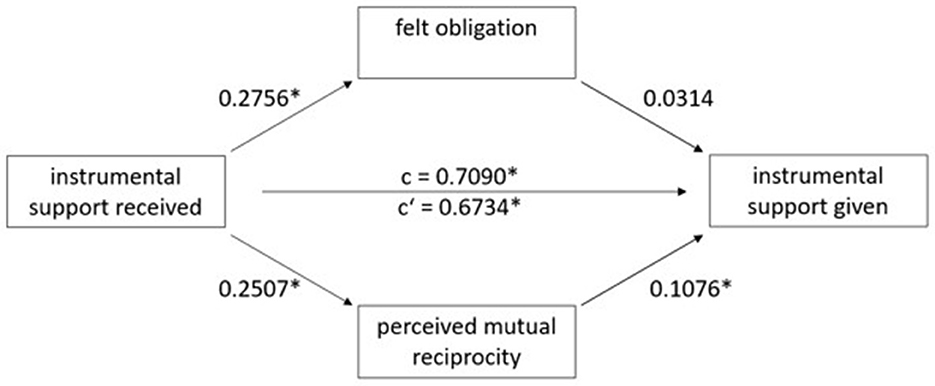

Hypothesis 4: The impact of felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity on the emotional support received and given by mothers

Figure 4. Parallel mediation model 3 of received and given instrumental support through felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity of mothers. Note Data from mothers. Standardized effects are presented. c = total effect of received on given instrumental support; c' = direct effect of received on given instrumental support. *p < 0.01.

Table 5. Model 3: Standardized indirect effects (IE) of received (ISR) on given instrumental support (ISG) through felt obligation (FO) and perceived mutual reciprocity (MR) of mothers.

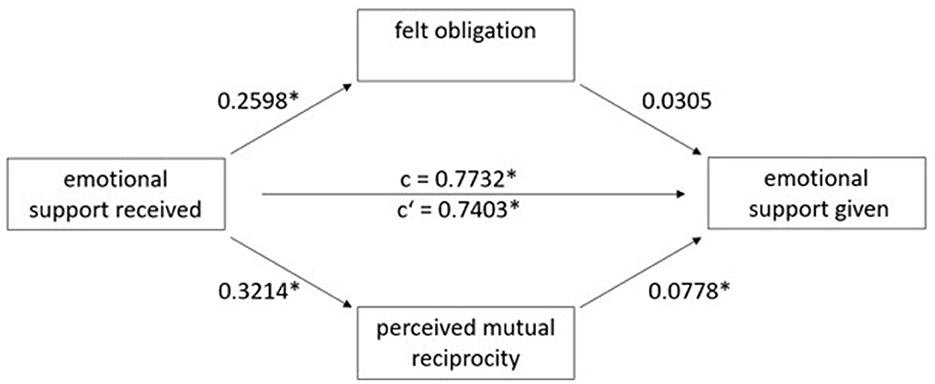

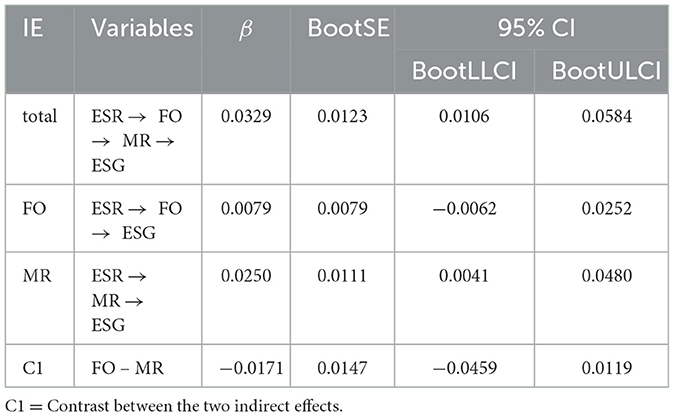

Parallel mediation model 4 (Figure 5) examines the mediating effects of felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity on the association between the emotional support received and given by mothers to their adult children. The received emotional support predicted the given emotional support of mothers (βtotal = 0.7732, p < 0.01). After the mediators felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity were included in the model the received emotional support of mothers from their adult children predicted both felt obligation (β = 0.2598, p = 0.01) and perceived mutual reciprocity (β = 0.3214, p < 0.01). However, only perceived mutual reciprocity (β = 0.0778, p < 0.01) predicted the given emotional support of mothers to their adult children; felt obligation did not make a significant contribution here. The relationship between emotional support received and given is still significant after the mediators were added to the model (βdirect = 0.7403, p < 0.01). The standardized indirect effects are shown in Table 6. The total indirect effect showed a partial mediation (β = 0.0329, 95% CI [0.0106, 0.0584]). There was a statistically significant indirect effect through perceived mutual reciprocity (β = 0.0250, 95% CI [0.0041, 0.0480]) but not through felt obligation. The difference between the two mediation paths (Table 6, C1) was not significant (β = −0.0171, 95% CI [−0.0459, 0.0119]). Hypothesis 4, that both felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity mediate the relationship between received and given emotional support by mothers to their adult children, can be disconfirmed. Only perceived mutual reciprocity had a mediating effect. When mothers perceived more mutual reciprocity in their relationship with their adult children, they were more likely to offer emotional support.

Figure 5. Parallel mediation model 4 of received and given emotional support through felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity of mothers. Note Data from mothers. Standardized effects are presented. c = total effect of received on given instrumental support; c' = direct effect of received on given instrumental support. *p < 0.01.

Table 6. Model 4: Standardized indirect effects (IE) of received (ESR) on given emotional support (ESG) through felt obligation (FO) and perceived mutual reciprocity (MR) of mothers.

Discussion

Support is an important resource that is exchanged during the social exchange process. It is well known that people's willingness to provide support is influenced by the support they receive (e.g., Sommer and Buhl, 2018). A crucial relationship of exchange is that between a mother and her child, in which support is one of the most valuable given resources. This is especially relevant when there are corresponding needs, such as those for care (e.g., Luichies et al., 2019). However, there is a period of life when both parties can pursue their life goals independently and without relying on each other in young and middle adulthood. This raises the question of what mechanisms mediate the giving and receiving of support by aging mothers and their adult children when there are no practical framework conditions, such as care needs, necessitating support.

The present study examined the mediating role of felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity as important attitudes regarding the association between receiving and giving support by mothers and their young to middle-aged adult children. Four parallel mediation models were tested for this purpose. The perspectives of mothers and adult children were considered separately, as well as instrumental and emotional support. Felt obligation mediated the instrumental support of young to middle-aged adult children to their mothers. Emotional support was mediated by both felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity. Perceived mutual reciprocity mediated the instrumental and emotional support given by mothers to their adult children. The correlational results are discussed next.

Mother–child dyads composed the sample. Interestingly, the descriptive results for both groups were similar, except for received support. Here, the mothers stated that they had received more instrumental support from their adult children. In contrast, the adult children stated that they had received more emotional support from their mothers. Both adult children and mothers reported relatively high levels of perceived mutual reciprocity and support. Adult children reported having experienced a strong obligation to their mothers, as previously shown in the literature (e.g., Del Corso and Lanz, 2013). Mothers also reported feeling a strong obligation to their offspring. Mutual behavioral expectations in this relationship, such as keeping in touch and providing help, were important to both sides. However, this expectation of appropriate behavior also appears to be a motive for children, but not for their mothers, to provide help. When young to middle-aged adult children received instrumental support from their mothers, they felt obligated to provide support. Perceived mutual reciprocity had no influence on the provision of instrumental support. Instrumental support services are perhaps less relevant to creating a reciprocal experience. Adolescent children readily accept the support of their parents and experience satisfaction in the relationship, regardless of the experience of equity (Vogl-Bauer et al., 1999). This seems to persist into middle adulthood in terms of instrumental support.

When receiving emotional support, adult children also have feelings of obligation that mediate assistance. In addition to felt obligation, perceived mutual reciprocity becomes important when it comes to forming the emotional bond between adult children and their mothers through the provision and receipt of emotional support. When it comes to emotional support, adult children appear to feel on an equal level with their mothers. The attitude toward the subjective experience of autonomy as an independent individual able to comfort and advise the mother proved to be important, as did the experience of emotional attachment, in terms of perceived mutual reciprocity. Accordingly, perceived mutual reciprocity could also be an indicator of relationship quality and the experience of emotional connectedness as a basis for the exchange of emotional support. Young to middle-aged adults perceive reciprocity differently depending on the type of support they receive (Schwarz et al., 2005), implying that different attitudes may be important when providing different types of support.

Receiving and giving support from mothers was mediated by perceived mutual reciprocity, not by felt obligation. This applied to both emotional and instrumental support; there were no differences in the types of support in contrast to their children. Mothers appear to help their children out of a desire for a relationship that includes respect and equality rather than an obligation. This suggests a unique bond between mothers and their children that is far more complex than the reciprocity norm. Similar descriptive values also illustrate this unique commitment. One could say that mothers always help. Perhaps this is also a behavioral expectation of adult children toward their mothers.

Distinguishing between perceived mutual reciprocity and the actual balance of support provided by actions is important. The actual support in the mother–child relationship is unbalanced; mothers provide unreciprocated support to their children until they reach their 70s (Fingerman et al., 2013). In the perception of reciprocity, the expectation of receiving support and the mental representation of the attachment figure shape the experience of being supported in the relationship. The perception of equity is more important than an actual balanced supportive exchange for how mothers perceive the quality of their relationships with their children (Sechrist et al., 2014). Throughout their lives, mothers generally express high levels of satisfaction with their relationships with their adult children (Suitor et al., 2011). Mothers' evaluations of their relationships with their children might not represent how evenly they support each other. Accordingly, the meaning of reciprocity might be different for adult children than for their mothers. Children do not have to do much to compensate for the rewards they receive from their parents (Vogl-Bauer et al., 1999). Family relationships are unique in that reciprocity between family members is negotiated throughout an individual's lifetime, and the value of consideration does not need to be the same as in other types of relationships to maintain a mutual relationship (e.g., Antonucci, 1985; Schwarz et al., 2005). In family contexts, reciprocity may be more of an indicator of relationship quality rather than the actual balance of support.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

The current study used cross-sectional data to gather preliminary information about potential relationships. However, no causality can be proven due to the correlational nature of the research design. Longitudinal data are better suited for testing causal relationships. The analysis included data obtained from adult children (20–49 years) and their mothers (40–87 years) within a specific age range. As this age range is relatively wide, age-related effects may also exist in young and middle adulthood. Future research should also consider attitudes as mediators of support for other age groups. The study also included mother–child dyads, the majority of whom had positive relationships. This may have introduced a bias in subject selection. Mother–child dyads who did not have a positive relationship with each other and who did not share a sense of obligation, reciprocity, or support may have chosen not to participate. This selection bias limits the conclusions and the generalizability of the findings. If there is a lack of positive relationship quality, further research should focus on the related attitudes in the mother–child relationship. Additionally, since this is a German sample, the findings may have limited applicability to individualistic Western contexts (Kagitcibasi, 2005). Differences in mediating attitudes between collectivist and individualist cultures should be researched in the future. The study relied solely on mothers' and children's self-reports, which included the biased perceptions (e.g., Schwarz et al., 2005) of both groups. Family relationships are complex and evolve throughout the lifespan. However, the validity of findings may be limited in intricate contexts. Including fathers in research could be provide valuable insights into differences in attitudes and the dynamics of the triad and their interrelationships in terms of support. In addition, there may be differences in experiences between sons and daughters.

In the current state of knowledge, this study makes an important contribution to understanding the attitudes that young and middle-aged adults and mothers have toward their relationships, which are important for mutual support when no practical restrictions determine this support. Given the increasing life expectancy and the duration of the relationship between mothers and their children, it is important to explore further mechanisms that mediate support in mother–child relationships.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethik-Kommission der Universität Paderborn. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

KS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SS: Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. HB: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Project “Interdependence in the Relationship between Adults and their Parents”. This work was funded by the German Research Foundation/Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG)—BU 1145/7-2.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Sommer, S., and Buhl, H. M. (under review). The role of norms, received support and felt obligation for intergenerational support to parents.

2. ^Schoenert, K., Sommer, S., and Buhl, H. M. (under review). Feelings of obligation: Predicting felt obligation of middle-aged adult children to their parents.

References

Ahmad, R., Nawaz, M. R., Ishaq, M. I., Khan, M. M., and Ashraf, H. A. (2023). Social exchange theory: systematic review and future directions. Front. Psychol. 13:1015921. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1015921

Ajzen, I., and Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude-behavior relations: a theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 84, 888–918. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.84.5.888

Antonucci, T. C. (1985). “Personal characteristics, social support, and social behavior,” in Handbook of Aging and Social Sciences, eds. R. H. Binstock and E. Shanas (Eds.) (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold), 94–128.

Baltes, M. M., and Silverberg, S. B. (1994). “The dynamics between dependency and autonomy: illustrations across the life span,” in Life-Span Development and Behavior, vol. 12, eds. D. L. Featherman, R. M. Lerner, and M. Perlmutter (Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc), 41–90.

Brandt, M., Deindl, C., Haberkern, K., and Szydlik, M. (2008). Reziprozität zwischen erwachsenen generationen: familiale transfers im lebenslauf/reciprocity between adult generations: family transfers across the life course. Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie 41, 374–381. doi: 10.1007/s00391-008-0003-7

Brandt, M., and Szydlik, M. (2008). Soziale Dienste und Hilfe zwischen Generationen in Europa/Social Services and Help between Generations in Europe. Zeitschrift für Soziologie 37, 301–320. doi: 10.1515/zfsoz-2008-0402

Buhl, H. M. (2008a). Development of a model describing individuated adult child-parent relationships. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 32, 381–389. doi: 10.1177/0165025408093656

Buhl, H. M. (2008b). “Ein erweitertes individuationstheoretisches Modell zur Vorhersage der aktuellen und geplanten Unterstützung Erwachsener für ihre Eltern/An extended model of individuation theory to predict adults' current and planned support for their parents,” in Intergenerationelle Transferleistungen in Familien, ed. E. J. Brunner (Georgia: Paideia), 79–99.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd Edn.). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cropanzano, R., Anthony, E. L., Daniels, S. R., and Hall, A. (2017). Social exchange theory: a critical review with theoretical remedies. Acad. Manage. Annals 11, 479–516. doi: 10.5465/annals.2015.0099

Cropanzano, R., and Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review. J. Manage. 31, 874–900. doi: 10.1177/0149206305279602

Del Corso, A. R., and Lanz, M. (2013). Felt obligation and the family life cycle: a study on intergenerational relationships. Int. J. Psychol. 48, 1196–1200. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.725131

Eaton, A. A., Majka, E. A., and Visser, P. S. (2008). Emerging perspectives on the structure and function of attitude strength. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 19, 165–201. doi: 10.1080/10463280802383791

Fingerman, K. L., Sechrist, J., and Birditt, K. (2013). Changing views on intergenerational ties. Gerontology 59, 64–70. doi: 10.1159/000342211

Fishbein, M., and Ajzen, I. (2009). Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach. East Sussex: Psychology Press.

Fishman, J., Yang, C., and Mandell, D. (2021). Attitude theory and measurement in implementation science: a secondary review of empirical studies and opportunities for advancement. Implement. Sci. 16, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01153-9

Freeberg, A. L., and Stein, C. H. (1996). Felt obligations towards parents in Mexican-American and Anglo-American young adults. J. Soc. Person. Relationsh. 13, 457–471. doi: 10.1177/0265407596133009

Funk, L. (2011). ‘Returning the love', not ‘balancing the books': Talk about delayed reciprocity in supporting ageing parents. Ageing Soc. 32, 634–654. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X11000523

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: a preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 25, 161–178. doi: 10.2307/2092623

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York City: Guilford Publications.

Iommi, L. G. (2019). Norm internalisation revisited: norm contestation and the life of norms at the extreme of the norm cascade. Global Constitutional. 9, 76–116. doi: 10.1017/S2045381719000285

Kagitcibasi, C. (2005). Autonomy and relatedness in cultural context—Implications for self and family. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 36, 3–422. doi: 10.1177/0022022105275959

Klaus, D. (2009). Why do adult children support their parents? J. Compar. Family Stud. 40, 227–241. doi: 10.3138/jcfs.40.2.227

Luichies, I., Goossensen, A., and van der Meide, H. (2019). Caregiving for ageing parents: a literature review on the experience of adult children. Nurs. Ethics 28, 844–863. doi: 10.1177/0969733019881713

Mitchell, M. S., Cropanzano, R., and Quisenberry, D. M. (2012). “Social exchange theory, exchange resources, and interpersonal relationships: a modest resolution of theoretical difficulties,” in Critical Issues in Social Justice, ed. M. Lerner, 99–118

Petty, R. E., Siev, J. J., and Briñol, P. (2023). Attitude strength: What's new? Span. J. Psychol. 26, 1–13. doi: 10.1017/SJP.2023.7

Rieger, D., and Buhl, H. M. (2004). Dokumentation des Fragebogens der zweiten Projektphase “Erwachsene und ihre Eltern”/Documentation of the questionnaire of the second phase of the project “Adults and their parents”, unpublished report. Jena: Friedrich-Schiller-University.

Rucker, D. D. (2021). Attitudes and attitude strength as precursors to object attachment. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 39, 38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.07.009

Schwarz, B., Trommsdorff, G., Albert, I., and Mayer, B. (2005). Adult parent–child relationships: relationship quality, support, and reciprocity. Appl. Psychol. 54, 396–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00217.x

Sechrist, J., Suitor, J. J., Howard, A., and Pillemer, K. (2014). Perceptions of equity, balance of support exchange, and mother–adult child relations. J. Marriage Family 76, 285–299. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12102

Siedlecki, K. L., Salthouse, T. A., Oishi, S., and Jeswani, S. (2013). The relationship between social support and subjective well-being across age. Soc. Indicat. Res. 117, 561–576. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0361-4

Sommer, S., and Buhl, H. M. (2018). Intergenerational transfers: associations with adult children's emotional support of their parents. J. Adult Dev. 25, 286–296. doi: 10.1007/s10804-018-9296-y

Stein, C. H. (1992). Ties that bind: Three studies of obligations in adult relationships with family. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 9, 525–547. doi: 10.1177/0265407592094004

Stein, C. H. (1993). “Felt obligation in adult family relationships,” in Social Context and Relationships, ed. S. Duck (Thousand Oaks: Sage), 78–99.

Stein, C. H. (2009). “‘I owe it to them': Understanding felt obligation towards parents in adulthood,” in How Caregiving Affects Development: Psychological Implications for Child, Adolescent, and Adult Caregivers, ed. K. Shifren (Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association), 119–145.

Stein, C. H., Wemmerus, V. A., Ward, M., Gaines, M. E., Freeberg, A. L., Jewell, T. C., et al. (1998). “Because they're my parents”: an intergenerational study of felt obligation and parental caregiving. J. Marriage Family 60, 611–622. doi: 10.2307/353532

Suitor, J. J., Sechrist, J., Gilligan, M., and Pillemer, K. (2011). “Intergenerational relations in later-life families,” in Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research, ed. R. T. Serpe, 161–178.

Swartz, T. T. (2009). Intergenerational family relations in adulthood: patterns, variations, and implications in the contemporary United States. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 35, 191–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134615

Thönnissen, C., Wilhelm, B., Fiedrich, S., Alt, P., and Walper, S. (2015). Pairfam Scales Manual. Wave 1 to 6. Unpublished document. https://www.pairfam.de/fileadmin/user_upload/redakteur/publis/Dokumentation/Manuals/Scales_Manual_pairfam_Release_14.2.pdf (accessed March 17, 2024).

Vogl-Bauer, S., Kalbfleisch, P. J., and Beatty, M. J. (1999). Perceived equity, satisfaction, and relational maintenance strategies in Parent–Adolescent dyads. J. Youth Adolesc. 28, 27–49. doi: 10.1023/A:1021668424027

Whitbeck, L. B., Hoyt, D. R., and Huck, S. M. (1994). Early family relationships, intergenerational solidarity, and support provided to parents by their adult children. J. Gerontol. 49, S85–S94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.S85

Winter, Y. (2001). Instrumentelle Unterstützung in erwachsenen Eltern-Kind-Beziehungen und die subjektive Beurteilung der Beziehung, Unveröffentlichtes Manuskript, Jena.

Keywords: felt obligation, reciprocity, support, mother–child relationship, lifespan development, social exchange theory

Citation: Schoenert K, Sommer S and Buhl HM (2025) Impact of felt obligation and perceived mutual reciprocity on support between mothers and their adult children. Front. Dev. Psychol. 3:1508469. doi: 10.3389/fdpys.2025.1508469

Received: 09 October 2024; Accepted: 27 May 2025;

Published: 18 June 2025.

Edited by:

Simon Kai Ciranka, Max Planck Institute for Human Development, GermanyReviewed by:

Isabelle Albert, University of Luxembourg, LuxembourgClaudia Martinez, Federal University of São Carlos, Brazil

Beata Szluz, University of Rzeszow, Poland

Geraldine Alves Dos Santos, Feevale University, Brazil

Copyright © 2025 Schoenert, Sommer and Buhl. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kathrin Schoenert, a2FzY2gxNzBAbWFpbC51bmktcGFkZXJib3JuLmRl

Kathrin Schoenert

Kathrin Schoenert Sabrina Sommer

Sabrina Sommer Heike M. Buhl

Heike M. Buhl