- 1Departamento de Desporto e Saúde, Escola de Saúde e Desenvolvimento Humano, Universidade de Évora, Évora, Portugal

- 2Comprehensive Health Research Centre (CHRC), Universidade de Évora, Évora, Portugal

- 3Departamento de Pedagogia e Educação, Escola de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Évora, Évora, Portugal

- 4Centro de Investigação em Educação e Psicologia, Universidade de Évora, Évora, Portugal

Despite the well-established benefits of play, a specific type of play, known as play fighting, remains controversial. This study aims to understand children's perspectives about play fighting through semi-structured interviews of 56 preschoolers (aged 4–6 years). A thematic inductive content analysis examined children's views on the characteristics of play fighting, the differences between play fighting and serious fighting, the factors influencing their engagement and enjoyment, and the strategies they use when difficulties arise during play fighting. The findings reveal that preschoolers have a clear understanding of play fighting. They describe it as non-harmful fighting behaviors performed with minimal force in a playful atmosphere, characterized by positive facial expressions, vocalizations, props, and fantasy themes. Children enjoy play fighting because it is fun, physically active, and involves fantasy themes that allow them to feel empowered. Preschoolers also recognize that play fighting differs from serious fighting. While they identify similar behaviors, serious fighting involves less restraint, greater force, and harm. When play fighting escalates, children use self-regulation strategies to manage the situation and return to a playful state. These findings suggest that play fighting is a valuable context for social-emotional learning and development in young children and should not be disregarded as inappropriate or undesirable behavior. Adults should trust that children know how to take the best of play fighting and ensure that they have the right to participate in this critical form of play.

1 Introduction

Play is so essential to children's health and wellbeing that Article 31 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Assembly, 1989) recognizes it as a fundamental right. Several academies of pediatricians, teachers and policymakers advocate for ensuring that children have ample time and opportunities to play, given its significant role in their motor, emotional and social development (Neto, 2020; Ginsburg, 2007; Pellegrini, 2009; United Nations, 2013). Despite the well-established consensus on the value of play, there is a specific type of play, particularly play fighting, that remains controversial. Play fighting is a fun, boisterous, and socially interactive form of play involving reciprocal physically active behaviors, such as chasing and fleeing, grappling, kicking, wrestling, and open palm tagging. Although it may appear aggressive, play fighting lacks harmful intent and occurs within a warm and cooperative atmosphere (Carlson, 2011). Play fighting involves a harmonious balance between competition and cooperation and has been described using various terms in the literature, such as playful aggression (Hart, 2016), superhero play (Bauer and Dettore, 1997), “bad guy” play (Logue and Detour, 2011), active pretend play (Logue and Harvey, 2009), big body play (Carlson, 2011), war play (Hellendoorn and Harinck, 1997; Levin and Carlsson-Paige, 2006), and gun play (Watson and Peng, 1992).

Many children, especially boys, enjoy play fighting because it is fun, promotes positive emotions, and provides an opportunity to “show what you can do and how skilled you are” (Smith et al., 1992, p. 217). As children engage in play fighting, excitement, pleasure, and sometimes frustration rise. Managing these emotions requires children to skillfully express their own emotions, decode others' emotions and intentions, and regulate their intense emotions and behaviors (Veiga et al., 2022a). Peer play fighting increases during the preschool years, a period when children's cognitive, emotional, and motor skills have developed sufficiently for them to interpret and adaptively respond to their play partner's emotions and behaviors (MacDonald and Parke, 1986). Play fighting takes about 5–9% of girls' and boys' recess time, respectively (Lindsey, 2014), although these percentages may increase in preschools that explicitly allow and support this form of play (Veiga et al., 2014). Although most research on children's play fighting suggests adaptive or beneficial outcomes for children's motor and social-emotional development (Smith and StGeorge, 2023; StGeorge and Freeman, 2017), because of the apparent similarity to real fighting (Smith and StGeorge, 2023), play fighting is often perceived with ambivalence, especially by preschool teachers.

Among teachers, play fighting is one of the least permitted types of play (Logue and Harvey, 2009). Indeed, a study on perspectives about play fighting in the preschool found that both preschoolers and teachers do not see play fighting as appropriate in this context (Tannock, 2008). Teachers report discouraging play fighting primarily to prevent injuries (Tannock, 2008) and children also recognize the potential to escalate to a serious fight, mainly because of accidental injuries (Smith et al., 1992). However, research seems to contradict teachers' and children's perceptions. Although real aggression and play-related aggression may sometimes appear similar, only a very small proportion (~0.3%) of play fighting escalates into actual aggression (Pellegrini, 1989; Pellegrini and Perlmutter, 1988; Scott and Panksepp, 2003). Play fighting could resemble aggression if not displayed in a playful atmosphere, characterized by positive affect, reciprocating roles, and sustained social interaction. This form of play is engaged in between friends or relatives, with no harmful intent such that when play ends, most play partners remain together (Fry, 1990; Humphreys and Smith, 1987; Storli, 2013).

Indeed, there is a well-established consensus on the criteria distinguishing play fighting from real fighting: positive facial and vocal expressions, restraint, role reversal, invitation as initiation and a sense of togetherness afterwards (Fry, 2005; Tannock, 2019; Smith, 2010). While most primary school children (90–94%) assume they can differentiate between a play fight and a serious fight (Costabile et al., 1991), this percentage is lower for preschool children (69%). Besides, when asked to specify the ways to tell a play fight from a serious fight only a small percentage of preschoolers refer to qualitative aspects of physical actions (16%) and non-verbal expressions (16%; Smith et al., 1992). Although this previous research provided valuable insights by incorporating children's perspectives on this ambivalent form of play, much of it is now over 20 years old, highlighting the need for updated studies that reflect contemporary educational practices and children's current experiences. Indeed, over the past decades, early childhood education curricula have evolved to emphasize children's active participation, encouraging them to reflect on their experiences and express their perspectives. This study aims to explore children's perspectives on play fighting, examining how they experience and interpret this form of play and the strategies they use to manage its intensity. Specifically, this study aimed to explore children's perceptions regarding: (1) the key characteristics of play fighting, (2) distinctions between play fighting and serious fighting; (3) reasons influencing their participation and enjoyment (or lack thereof) in play fighting, and (4) strategies employed to manage challenges encountered during play fighting. By emphasizing children's perspectives, this study aims to inform educators and caregivers about how preschool children experience and understand play fighting, thus providing insights to better support their developmental needs.

2 Methods

2.1 Ethics statement

The study was approved by the research ethics board at the University of Évora (#22247), Portugal, and was carried out under the standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki (General Assembly of the World Medical Association, 2014). After the Ethics approval, the project was presented to the director and the preschool teachers of the preschool who consented to participate. Next, caregivers were informed about the goals and procedures of the study, the handling and storage of data to ensure participants' privacy, and the voluntary nature of participation. Caregivers were asked to give their written informed consent. The children were also informed about the purpose of the study and gave verbal consent for their own participation.

2.2 Procedures

The participants in this study involved 56 children (29 boys), aged between 4 and 6 years (Mean age = 4,92 years), recruited from a preschool in Évora, Portugal.

Considering guidelines recommending the use of small groups interviews to help children feel at ease among peers, thus promoting richer discussions (Goodwin and Goodwin, 1996; Walsh et al., 1993), semi-structured interviews were conducted in small groups of four children from the same classroom. Considering the gender differences in engagement with play fighting, 14 groups were formed: eight same-sex groups (four groups of boys, four groups of girls) and six mixed-sex groups. Interviews were carried out in a quiet room at the preschool and were ~20 min long, with a maximum duration of 30 min.

Each focus group was conducted by the same researcher, with participants seated in a circle or semicircle to ensure visual contact among all participants. First, two short videos (52 seconds) of children play fighting at the playground were shown as a basis for starting the conversation. Second, questions were directed to the group, encouraging contributions from all children. The moderator facilitated group discussions by encouraging all children's contributions, maintaining neutrality without expressing judgments, managing the interaction, and monitoring time effectively. Although there was a predetermined order of questions, it could change depending on how the discussion unfolded. The time distribution of the interview was as follows: (1) Introduction and information about the objectives and functioning of the focus group (~ 3 minutes); (2) Video presentation (52 seconds); (3) Discussion of specific questions (~20 minutes): 1. With whom do you play fight? 2. How do you play fight? 3. How do you distinguish a play fight from a real fight? 4. Why do or don't you like play fighting? 5. How could you enjoy play fighting more? 6. How do you resume playing after something has gone wrong?; and (4) Conclusion and acknowledgments (2 minutes).

The interviews with the children were video recorded to facilitate accurate transcription. Participants were assigned a unique code indicating the interview number, gender, and participant number within the group. For example, “3B2” refers to the second boy in the third interview.

2.3 Data analysis

The semi-structured interviews were transcribed and systematically analyzed following the principles of thematic categorical inductive content analysis (Bardin, 2013; Esteves, 2006). Units of meaning—phrases, words, or expressions providing information relevant to the defined categories—were identified, recorded, and assigned to corresponding categories. Within each category, subcategories and specific indicators were established to systematically organize these units of meaning. For example, a category such as “no physical contact” could include a subcategory like “no touch in specific areas” with specific indicators such as “face”. Frequencies for each indicator were calculated, with higher frequencies indicating greater importance from the children's perspectives.

3 Results

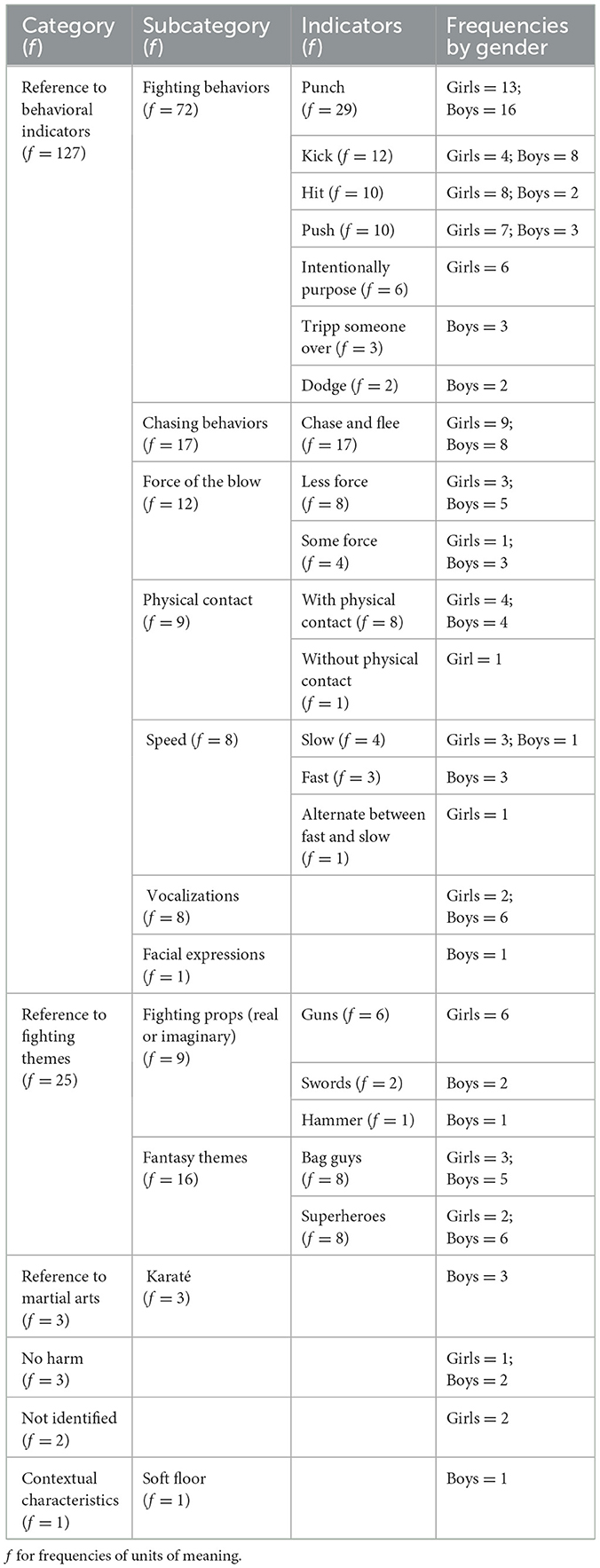

Table 1 shows preschoolers' characterization of play fighting. Children identified several behavioral indicators of play fighting, including fighting behaviors (f = 72; e.g., hitting, punching, kicking, tripping over, pushing, dodging, intentionally falling) and chasing (f = 17). Children also mentioned some characteristics of play fighting behaviors such as physical contact (f = 9), the force of the blow (f = 12), the speed of movements (f = 8), the use of vocalizations during these behaviors (f = 8), and facial expression (f = 1). Regarding the force used, some children indicated that play fighting involves less force (f = 8), while others noted using moderate force (f = 4). Children also characterized play fighting by referring to specific fighting props (e.g., guns f = 6; swords f = 2; hammer, f = 1), and make-believe fighting themes, such as bad guys (f = 8), and superheroes (f = 8). Some children (f = 3) also referred to the similarity with martial arts. Moreover, children noted that play fighting does not result in negative consequences, such as getting hurt (f = 3) and that it occurs in a space where children can safely fall (f = 1).

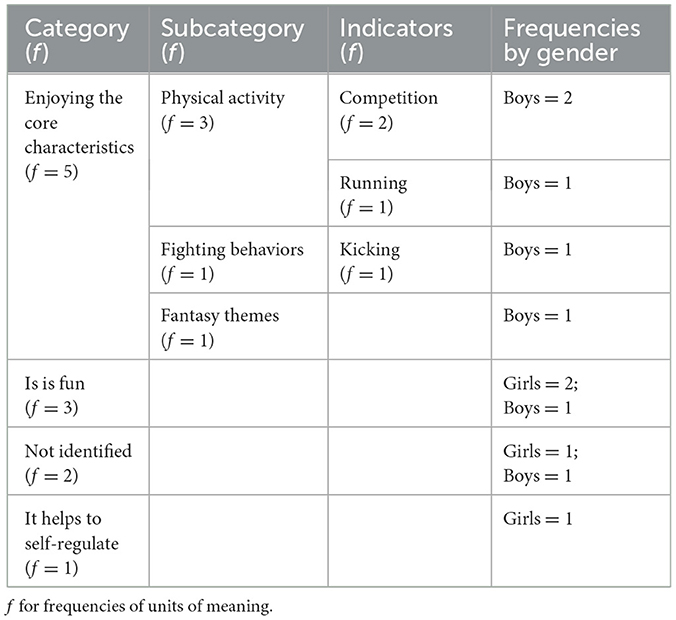

Table 2 shows the reasons for children enjoying play fighting. The most predominant reasons were the fun of it (f = 3), and the enjoyment of the core characteristics of play fighting, such as the fighting behaviors (f = 1), the fantasy themes (f = 1) and the physical activity (f = 3). A girl also mentioned that play fighting is a way for other children to self-regulate (f = 1) and two children (1 girl, 1 boy) were unable to explain why they like play fighting.

Concerning the reasons for not enjoying play fighting (Table 3), the majority (f = 31) focused on the negative outcomes, either physical (i.e., getting hurt or hurt others) or social (i.e., getting grounded). Only girls mentioned the high intensity (f = 2) and the perception that it is not an adequate type of play for girls (f = 2). Two children (1 girl, 1 boy) mentioned that they could not identify the reasons for enjoying play fighting.

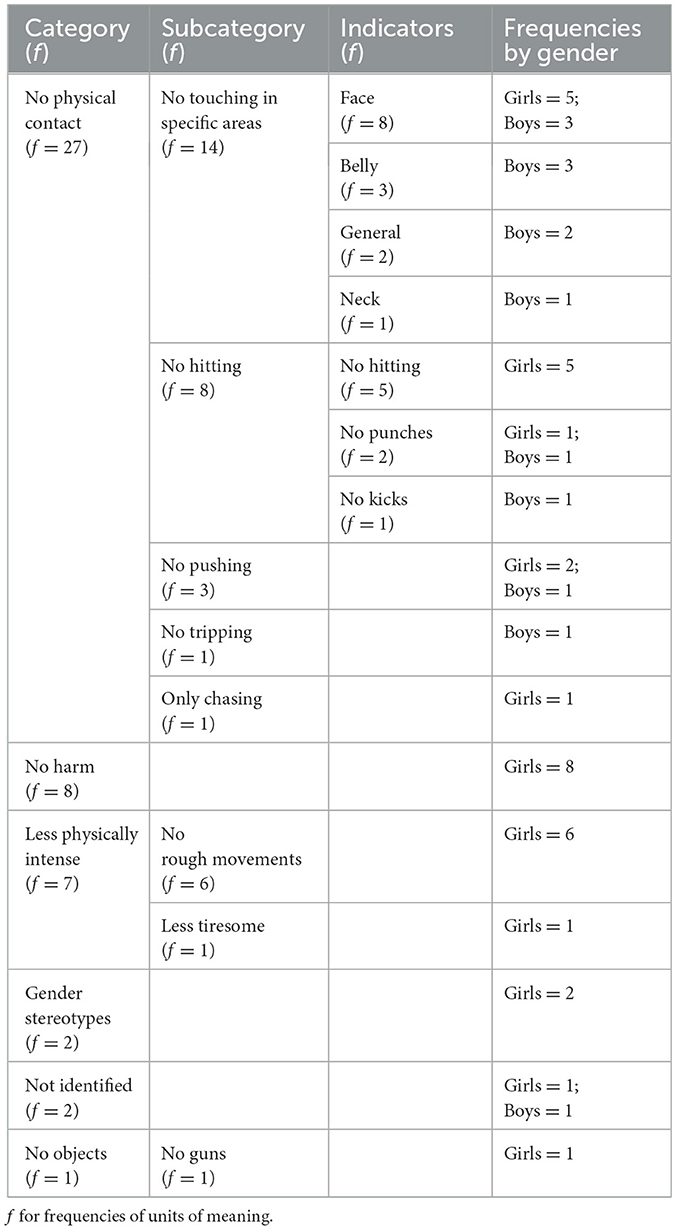

When asked about how their enjoyment in play fighting could be increased (Table 4), most answers focused on the absence of physical contact (f = 27), especially in specific areas (e.g., face, belly, neck). Some children also referred that they would enjoy more play fighting if it did not involve fighting behaviors, such as hitting or punching. Also, some children (f = 7) mentioned wanting less physically intense interactions, with no rough movements (f = 6). Girls also mentioned gender stereotypes (f = 2), stating that if they were boys, they would enjoy play fighting. Two children (1 girl) mentioned they did not know how their enjoyment of play fighting could be increased.

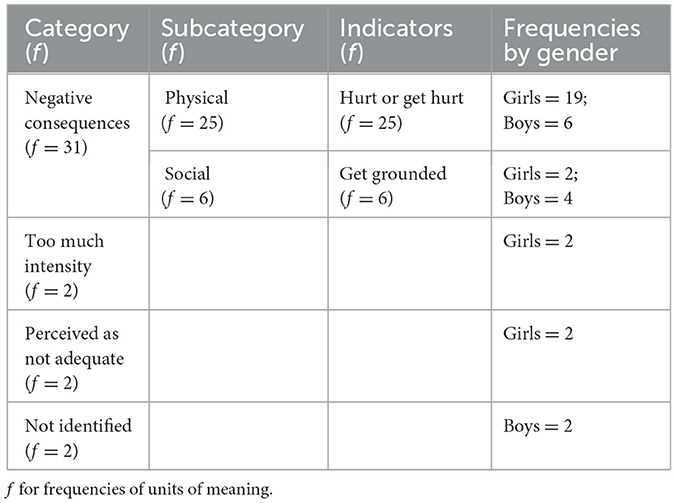

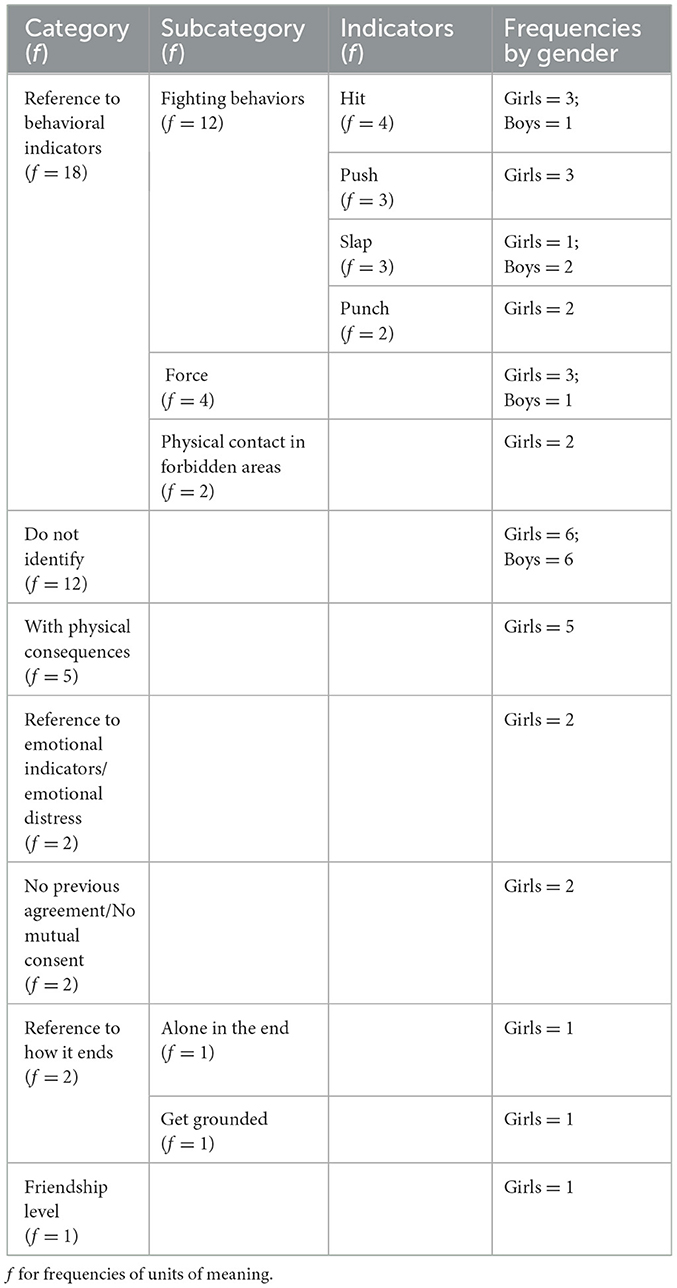

Regarding the acknowledgment of the characteristics of a real fight (Table 5), children identified behavioral indicators such as pushing hard (f = 3), hitting hard (f = 4), slapping (f = 3), and punching (f = 2), performed without restraint (f = 4) and in forbidden areas (f = 2; e.g., stomach, mouth). Children also associated real fights with negative emotional states. The way the interaction starts and ends was also an indicator used to distinguish a play fight from a real fight. In a real fight, there is no previous agreement (f = 2), the interaction ends (f = 2) or is stopped by adults, who may punish or ground the children (f = 1), and children do not stay together afterwards (f = 1). The relationship and the contextual features were also mentioned. One child noted that real fights tend to happen between children who are not best friends. Twelve children (6 girls) mentioned that they could not identify the differences between play fighting and real fighting.

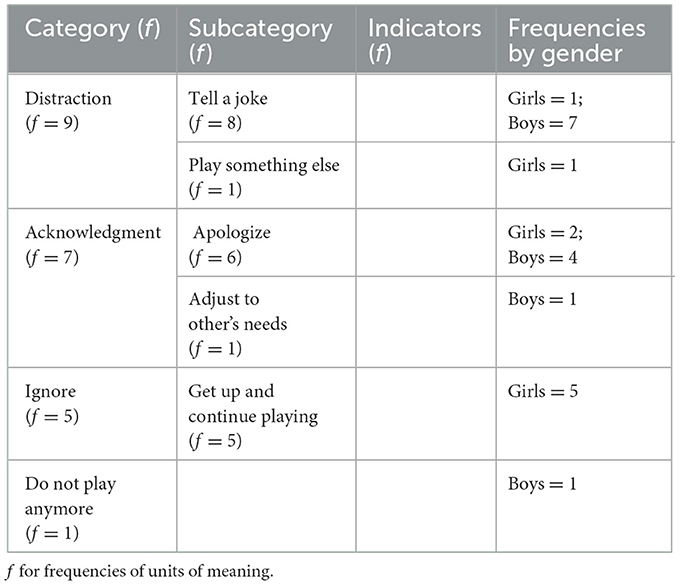

Concerning strategies used by children to resume play fighting after a conflict (Table 6), some children mentioned ignoring the conflict, by getting up and continuing to play (f = 5) while others described distraction strategies, such as telling a joke (f = 8) or playing something else (f = 1), before engaging again in play fighting. Moreover, some children mentioned that when the play fight goes wrong, they apologize (f = 6) or adjust their behavior to the other's needs. One boy said that he would not play anymore.

4 Discussion

During the preschool years, children already exhibit a clear understanding of play fighting. In line with standard definitions (Carlson, 2011; Smith et al., 2004; Schåfer and Smith, 1996), preschoolers describe it as involving minimal force fighting behaviors such as punching, kicking, pushing, tripping, intentionally falling and dodging. They emphasized that these actions remain non-harmful and occur in a playful atmosphere characterized by positive facial expressions (e.g., play face), vocalizations, props (e.g., toy guns, swords), and fantasy themes. However, there was no consensus on the speed of movements, with some children describing them as fast, others as slow, or as alternating between both. Additionally, children highlighted the importance of contextual features (e.g., soft floor) where these playful interactions occur.

Notably, preschoolers did not recognize role reversals as a feature of play fighting, despite its conceptual relevance in the definitions of this form of play (Pellegrini, 1989; Smith et al., 2004; Pellegrini and Smith, 1998). Given that observational studies show play fighting is common in early childhood (Lindsey and Colwell, 2013; Veiga et al., 2017, 2022b), it is possible that preschoolers are still developing an understanding of dominance swapping within these interactions. Similarly, only one child mentioned the play face, suggesting that its subtle blend of positive yet combative elements may be difficult for children at this young age to interpret. While most 4- to 5-year-olds can accurately and reliably recognize facial expressions of the six basic emotions (Parker et al., 2013), the dynamic and fast-paced nature of play fighting may lead them to rely more on movement patterns and vocal cues to differentiate play fighting from real aggression.

Fantasy themes emerged as central to children's conception of play fighting. Playing as “bad guys” or “superheroes” was particularly meaningful, reinforcing research suggesting that assuming such roles allow children to experience feelings of power and control in ways they may not in daily life (Bauer and Dettore, 1997). This form of play may foster self-confidence and resilience by enabling children to engage in scenarios where they can overcome obstacles and “save the world.” Moreover, role-playing as superheroes or villains may provide opportunities to explore important emotions such as fear, anger, and pride (Pellegrini, 2009), as well as themes of justice, fairness, and empathy (Singer and Singer, 2005).

Although children did not mention some expected characteristics like role reversal when describing play fighting, they identified their opposites in real fights. For instance, children mentioned similar behaviors (e.g., pushing, hitting, slapping, punching) but noted that real fights lacked restraint and resulted in harm. Like findings from rodent studies (Pellis et al., 2022), children recognized that targets of attack differ in real fights, often involving restricted areas such as the stomach and mouth. Few children mentioned emotional distress, the absence of mutual consent, or the negative consequences of a real fight (e.g., being left alone or getting grounded), suggesting that these aspects may be too nuanced for young children to recognize.

Far fewer children could describe a real fight than a play fight. Given that the construction of meaning and knowledge derives from children's experiences and interactions within their sociocultural environment (Piaget, 1952; Vygotsky, 1978), this suggests that preschoolers are more familiar with play fighting than with serious fighting.

Although children generally enjoy play fighting, most could not articulate why, possibly due to their young age. This finding is in line with a previous study in which 40% of 5-year-olds struggled to explain their preference for play fighting (Smith et al., 1992). However, factors such as fun, active behaviors, fantasy themes, and physical activity were identified as reasons for enjoyment. Notably, two preschool boys mentioned enjoying play fighting for its competitive nature, which, as Storli (2013, p. 3) observed, may help prevent play fighting from becoming “excessively predictable and losing its pleasurable quality.”

One girl mentioned that play fighting helps their peers self-regulate, aligning with Tremblay's (2006) view that play fighting serves as a “traditional means by which most children learn to regulate physical aggression” (p. 485). Empirical studies have supported this, demonstrating a positive association between play fighting and preschoolers' emotion regulation, both concurrently and longitudinally (Lindsey and Colwell, 2013).

However, some children, mostly girls, expressed dislike for play fighting, because of the risk of injury. This aligns with a prior study where 80% of young children cited accidental injury as the main reason for disliking play fighting (Smith et al., 1992). Fewer children mentioned fear of being grounded, reinforcing findings suggesting that some adults prohibit this form of play in kindergartens. Indeed, research across various countries have shown that play fighting is the least tolerated and most often prohibited type of play type among teachers (Logue and Harvey, 2009; Koustourakis et al., 2015; Storli and Hansen Sandseter, 2017; Storli and Sandseter, 2018).

Two girls explicitly stated that play fighting is not appropriate, suggesting that certain types of play are perceived as more suitable for boys than for girls. This reflects traditional gender norms that have historically linked play fighting to boys, positioning it as a means of constructing male identity (Thorne, 1993). These findings align with gender stereotypes associating play fighting with traditionally male traits such as strength, speed, endurance, physical contact, and competition. In contrast, female gender roles have been linked to less intensity, less physical contact, cooperative and aesthetically expressive activities (Pomar and Neto, 1997). Gender stereotypes thus significantly shape children's preferences and choices regarding play types and playmates (Thorne, 1993; King et al., 2021).

Nonetheless, contemporary research emphasizes the fluidity of gender roles in play, highlighting the influence of social contexts rather than biological determinants (Paechter, 2007). Although play fighting has been traditionally associated with masculinity, children of all genders choose to engage in or avoid this type of play for various reasons, underscoring the significant influence of social contexts on children's play behaviors (Messner, 2015). These findings challenge rigid gender distinctions and highlight the importance of supporting children's freedom to make individual play choices without pressure to conform to traditional expectations.

For some preschoolers, the intensity of play fighting can be overwhelming. When asked how their enjoyment in play fighting could be increased, some children—mostly girls—expressed a preference for less physical contact and less intense interactions. This aligns with observational studies (Lindsey and Colwell, 2013; Veiga et al., 2017, 2022b; Storli, 2021), which report lower engagement in play fighting among girls than boys. These differences may stem from a combination of biological tendencies (Auyeung et al., 2009), socialization practices (Lindsey and Mize, 2001), and broader societal expectations (Blakemore et al., 2008). While boys may have a biological predisposition toward physically active play, societal norms and expectations reinforce and magnify these differences. Notably, two girls stated that play fighting is not suitable for girls and suggested that if they were boys, they would enjoy it (e.g., “If I were a boy, I would play fight”), reflecting early gender identity development and the early internalization of gender roles (Brannon, 2016). Encouraging all children, regardless of gender, to explore diverse play types can help deconstruct gender stereotypes and promote balanced developmental experiences.

Although rare, play fighting can sometimes escalate into aggression. When this occurs, children employ self-regulation strategies typical of their developmental stage, such as ignoring, distracting, or acknowledging. The most common strategies included actively disengaging from a negative stimulus (e.g., “we get up, shake it off and continue”) and redirecting focus to something neutral (e.g., “first they stop, then they play with Legos and then they start play fighting again”) or positive (e.g., “we make a joke, they start laughing and then we continue”), aligning with previous findings (Smith et al., 1992). Possibly due to their young age, only a few children mentioned acknowledging the other's emotions and needs and adjusting their behavior accordingly.

5 Conclusion

Preschool aged children already demonstrate a clear understanding of play fighting, recognizing it as a non-harmful, physically active form of social interaction. They describe it as involving minimal-force fighting behaviors (e.g., punching, kicking, tripping someone over, intentional falling), that occur in a playful atmosphere, characterized by positive facial expressions, vocalizations, props, and fantasy themes. While most children could not explicitly articulate why they enjoy play fighting, they identified fun, physical activity and fantasy themes as key reasons for their enjoyment. Preschoolers already distinguish play fighting from serious fighting, recognizing that real fights involve similar behaviors but with no restraint, different body targets, and a harmful intent. When play fighting escalates into aggression, children employ well-known self-regulation strategies to maintain the playful nature of the interaction. These findings highlight the crucial role of play fighting in children's social-emotional learning and development. Therefore, children should not be deprived of this type of play. As emphasized in the United Nations General Comment on children's rights, adults should trust that children know how to take the best from play fighting, recognize its essential contribution to their development, and therefore ensure that children have the right to engage in play fighting.

Preschoolers' perspectives and attitudes toward play fighting seem to reflect traditional gender stereotypes. However, research supports a more flexible view on play preferences. Rather than being biologically determined, children's engagement in play fighting is shaped by social context and cultural norms. Encouraging children to engage in diverse play experiences, free from rigid gender expectations, can foster a more inclusive and balanced approach to social, emotional, and physical development.

Some limitations should be acknowledged. The school environment often imposes specific behavioral expectations, which may have influenced how children described play fighting. As a result, their responses might reflect what they perceived as “school-appropriate” answers rather than their full perspectives. Future research could explore children's views about play fighting in diverse schools and settings (e.g., homes, after school clubs) and combine interviews with systematic observations of spontaneous play. This multimethod approach would provide a richer and more comprehensive understanding of how children experience and conceptualize play fighting across different contexts.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

GV: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CR: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) under the project RIGHT PLAY: a primary prevention mental health program for preschoolers (2023.00119.RESTART).

Acknowledgments

We thank the children who gave their valuable insights for this study. We also thank the school, the preschool teachers, and the parents who approved and facilitated their participation. The authors would also like to express their deep gratitude to Professor Carlos Neto, a tireless advocate for children's right to play in Portugal. His lifelong dedication to the wonder of play has inspired the heart of this work and the spirit of this research team.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Assembly, U. G. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. United Nations, Treaty Series. 1577, 1–23.

Auyeung, B., Baron-Cohen, S., Ashwin, E., Knickmeyer, R., Taylor, K., Hackett, G., et al. (2009). Fetal testosterone predicts sexually differentiated childhood behavior in girls and in boys. Psychol Sci. 20, 144–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02279.x

Bauer, K. L., and Dettore, E. (1997). Superhero play: what's a teacher to do? Early Child Educ. J. 25, 17–21. doi: 10.1023/A:1025677730004

Blakemore, J. E., Berenbaum, S. A., and Liben, L. S. (2008). Gender Development. 1st ed. New York: Psychology Press.

Brannon, L. (2016). Gender: Psychological Perspectives (7th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315621821

Costabile, A., Smith, P. K., Matheson, L., Aston, J., Hunter, T., Boulton, M., et al. (1991). Cross-national comparison of how children distinguish serious and playful fighting. Dev. Psychol. 27:881. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.27.5.881

Esteves, M. (2006). Análise de conteúdo. Fazer investigação: Contributos para a elaboração de dissertações e teses, 105–126.

Fry, D. P. (1990). Play aggression among Zapotec children: Implications for the practice hypothesis. Aggress. Behav. 16, 321–340.

Fry, D. P. (2005). “Rough-and-tumble social play in humans,” in The Nature of Play: Great Apes and Humans, eds. A. D. Pellegrini and P. K. Smith (New York: Guilford Press), 54–85.

General Assembly of the World Medical Association (2014). World medical association declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. J. Am. Coll. Dent. 81, 14–18. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053

Ginsburg, K. R. (2007). Committee on psychosocial aspects of child and family health. the importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bonds. Pediatrics. 119, 182–191. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2697

Goodwin, W. L., and Goodwin, L. D. (1996). Understanding Quantitative and Qualitative Research in Early Childhood Education. New York: Teachers College Press.

Hart, J. L. (2016). Early childhood educators' attitudes towards playful aggression among boys: exploring the importance of situational context. Early Child Dev. Care 186, 1983–1993. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2016.1146262

Hellendoorn, J., and Harinck, F. J. (1997). War toy play and aggression in dutch kindergarten children. Soc. Dev. 6, 345–357. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00042

Humphreys, A. P., and Smith, P. K. (1987). Rough and tumble, friendship, and dominance in schoolchildren: evidence for continuity and change with age. Child Dev. 58, 201–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb03500.x

King, T. L., Scovelle, A. J., Meehl, A., Milner, A. J., and Priest, N. (2021). Gender stereotypes and biases in early childhood: a systematic review. Australas. J. Early Child. 46, 112–125. doi: 10.1177/1836939121999849

Koustourakis, G. S., Rompola, C., and Asimaki, A. (2015). Rough and tumble play and gender in kindergarten: perceptions of kindergarten teachers. Int. Res. Educ. 3, 93–109. doi: 10.5296/ire.v3i2.7570

Lindsey, E. W. (2014). Physical activity play and preschool children's peer acceptance: Distinctions between rough-and-tumble and exercise play. Early Educ. Dev. 25, 277–294. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2014.890854

Lindsey, E. W., and Colwell, M. J. (2013). Pretend and physical play: links to preschoolers' affective social competence. Merrill-Palmer Q. 59, 330–360. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2013.0015

Lindsey, E. W., and Mize, J. (2001). Contextual differences in parent–child play: implications for children's gender role development. Sex Roles. 44, 155–176. doi: 10.1023/A:1010950919451

Logue, M. E., and Detour, A. (2011). “You be the bad guy”: a new role for teachers in supporting children's dramatic play. Early Child Res. Pract. 13. [Epub ahead of print].

Logue, M. E., and Harvey, H. (2009). Preschool teachers' views of active play. J. Res. Child Educ. 24, 32–49. doi: 10.1080/02568540903439375

MacDonald, K., and Parke, R. D. (1986). Parent-child physical play: the effects of sex and age of children and parents. Sex Roles. 15, 367–378. doi: 10.1007/BF00287978

Messner, M. A. (2015). Some Men: Feminist Allies and the Movement to End Violence Against Women. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Neto, C. (2020). Libertem as Crianças: A Urgência de Brincar e Ser Ativo. Lisboa: Contraponto Editores.

Paechter, C. (2007). Being Boys; Being Girls: Learning Masculinities and Femininities: Learning Masculinities and Femininities. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

Parker, A. E., Mathis, E. T., and Kupersmidt, J. B. (2013). How is this child feeling? Preschool-aged children's ability to recognize emotion in faces and body poses. Early Educ. Dev. 24, 188–211. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2012.657536

Pellegrini, A. D. (1989). Elementary school children's rough-and-tumble play. Early Child Res. Q. 4, 245–260. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(89)80006-7

Pellegrini, A. D. (2009). The Role of Play in Human Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195367324.001.0001

Pellegrini, A. D., and Perlmutter, J. C. (1988). Rough-and-tumble play on the elementary school playground. Young Child. 43, 14–17.

Pellegrini, A. D., and Smith, P. K. (1998). Physical activity play: the nature and function of a neglected aspect of play. Child Dev. 69, 577–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.00577.x

Pellis, S. M., Pellis, V. C., Burke, C. J., Stark, R. A., Ham, J. R., Euston, D. R., et al. (2022). Measuring play fighting in rats: a multilayered approach. Curr. Protoc. 2:e337. doi: 10.1002/cpz1.337

Piaget, J. (1952). The Origins of Intelligence in Children. New York: International University. doi: 10.1037/11494-000

Pomar, C., and Neto, C. (1997). “Percepção da Apropriação e do Desempenho Motor de Género em Actividades Lúdico-motoras,” in Jogo e desenvolvimento da criança, ed. C. Neto (Lisboa: Edições FMH), 178–205.

Schåfer, M., and Smith, P. K. (1996). Teachers' perceptions of play fighting and real fighting in primary school. Educ. Res. 38, 173–181. doi: 10.1080/0013188960380205

Scott, E., and Panksepp, J. (2003). Rough-and-tumble play in human children. Aggress. Behav. 29, 539–551. doi: 10.1002/ab.10062

Singer, J. L., and Singer, D. G. (2005). Preschoolers' imaginative play as precursor of narrative consciousness. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 25, 97–117. doi: 10.2190/0KQU-9A2V-YAM2-XD8J

Smith, P. K., Hunter, T., Carvalho, A. M., and Costabile, A. (1992). Children's perceptions of playfighting, playchasing and real fighting: a cross-national interview study. Soc. Dev. 1, 211–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.1992.tb00125.x

Smith, P. K., Smees, R., and Pellegrini, A. D. (2004). Play fighting and real fighting: using video playback methodology with young children. Agress. Beh. 30, 164–173. doi: 10.1002/ab.20013

Smith, P. K., and StGeorge, J. M. (2023). Play fighting (rough-and-tumble play) in children: developmental and evolutionary perspectives. Int. J. Play. 12, 113–126. doi: 10.1080/21594937.2022.2152185

StGeorge, J., and Freeman, E. (2017). Measurement of father–child rough-and-tumble play and its relations to child behavior. Infant Ment. Health J. 38, 709–725. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21676

Storli, R. (2013). Characteristics of indoor rough-and-tumble play (RandT) with physical contact between players in preschool. Nordisk barnehageforskning. 6. doi: 10.7577/nbf.342

Storli, R. (2021). Children's rough-and-tumble play in a supportive early childhood education and care environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18:10469. doi: 10.3390/ijerph181910469

Storli, R., and Hansen Sandseter, E. B. (2017). Gender matters: male and female ECEC practitioners' perceptions and practices regarding children's rough-and-tumble play (R&T). Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 25, 838–853. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2017.1380881

Storli, R., and Sandseter, E. B. (2018). “Preschool teachers' perceptions of children's rough-and-tumble play in indoor and outdoor environments,” in Early Childhood Pedagogies (London: Routledge), 281–95. doi: 10.4324/9781315473536-18

Tannock, M. (2019). “Rough play: past, present and potential,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Play: Developmental and Disciplinary Perspectives, eds. P. K. Smith and J. L. Roopnarine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 200–221.

Tannock, M. T. (2008). Rough and tumble play: an investigation of the perceptions of educators and young children. Early Child Educ. J. 35, 357–361. doi: 10.1007/s10643-007-0196-1

Tremblay, R. E. (2006). Prevention of youth violence: why not start at the beginning? J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 34, 480–486. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9038-7

Veiga, G., da Silva, B., Gibson, J., and Rieffe, C. (2022a). “Emotions in play: the role of physical play in children's social well-being,” in OUP Handbook of Emotion Development, eds. D. Dukes, A. C. Samson, and R. Walle (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 339–353. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198855903.013.28

Veiga, G., De Leng, W., Cachucho, R., Ketelaar, L., Kok, J. N., Knobbe, A., et al. (2017). Social competence at the playground: Preschoolers during recess. Infant Child Dev. 26:e1957. doi: 10.1002/icd.1957

Veiga, G., Neto, C., and Rieffe, C. (2014). “Jogo de atividade física, competência motora e competência social na idade pré-escolar,” in Estudos em Desenvolvimento Motor da Criança VII, eds. C. Neto, J. Barreiros, R. Cordovil, F. Melo (Cruz Quebrada: Edições FMH), 239–246.

Veiga, G., O'Connor, R., Neto, C., and Rieffe, C. (2022b). Rough-and-tumble play and the regulation of aggression in preschoolers. Early Child Dev. Care. 192, 980–992. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2020.1828396

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). “The role of play in development,” in Mind in Society (Cambridge: Harvard University Press).

Walsh, D. J., Tobin, J. J., and Graue, M. E. (1993). “The interpretive voice: qualitative research in early childhood education,” in Handbook of Research on the Education of Young Children, ed. B. Spodek (New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company), 464–474.

Keywords: physical play, kindergarten, qualitative analysis, children participation, social emotional competence, rights of the child, rough and tumble play

Citation: Veiga G, Rebocho C and Pomar C (2025) Play fighting at the playground: understanding preschoolers' experiences and perceptions. Front. Dev. Psychol. 3:1545063. doi: 10.3389/fdpys.2025.1545063

Received: 13 December 2024; Accepted: 31 March 2025;

Published: 28 April 2025.

Edited by:

Laura Franchin, University of Trento, ItalyReviewed by:

Andre Pombo, Instituto Politécnico de Lisboa, PortugalDenise Soares, American University of the Middle East, Kuwait

Copyright © 2025 Veiga, Rebocho and Pomar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guida Veiga, Z3ZlaWdhQHVldm9yYS5wdA==

Guida Veiga

Guida Veiga Carolina Rebocho

Carolina Rebocho Clarinda Pomar

Clarinda Pomar