- Department of Psychological, Health & Learning Sciences, University of Houston, Houston, TX, United States

Beliefs about emotion may guide parents' socialization behaviors and shape the overall family environment. Research specifically addressing parental beliefs about children's emotions has expanded in the past 3 decades. Much of this research addresses variations in emotion-related parental beliefs within and across sociocultural contexts, demonstrating how these beliefs may represent a confluence of the macrosystem and microsystem, or m (ai)crosystem. In this paper, we review the body of research on parental beliefs about emotions. We describe the array of emotion-related parental beliefs that have been studied and discuss associations of these beliefs with parenting behaviors and child outcomes that are linked to positive youth development. We extend the field's consideration of sociocultural contexts for parental beliefs by addressing how cultural socialization, racial socialization, and gender socialization may influence and be influenced by parents' beliefs about children's emotions. We identify areas of strength in the literature and gaps in knowledge that are important areas for growth. We conclude by suggesting future directions for theory and research on the role of parental beliefs in family processes and positive youth development.

1 Introduction

Parental emotion socialization plays an important role in children's development of socio-emotional skills and their adaptive outcomes, including outcomes that are indicators of positive youth development (Eisenberg et al., 1998; Eisenberg, 2020; Lerner et al., 2006; Spinrad et al., 2020). Parental beliefs about children's emotions have been recognized as influences on parental emotion socialization behaviors and contributors to the overall family emotional climate (Dunsmore and Halberstadt, 1997; Eisenberg et al., 1998; Morris et al., 2007). Across the past 3 decades, empirical research on parental beliefs about children's emotions has increased. Given sociocultural variability in emotion display rules and meanings ascribed to emotions, it is noteworthy that a substantial part of this body of research considers emotion-related parental beliefs within and across sociocultural contexts (Raval and Walker, 2019). Furthermore, recent theoretical advances in developmental and family sciences spotlight ways that sociocultural contexts are inextricably interwoven with parent-child socialization processes (Rogers et al., 2021; Vélez-Agosto et al., 2017). Parental beliefs about children's emotions are shaped by sociocultural contexts and may provide an avenue through which sociocultural contexts inform parental emotion socialization practices (Dunsmore and Halberstadt, 2009). Thus, the time is ripe for a review synthesizing research on parental beliefs about children's emotions with approaches to domains of sociocultural socialization.

The purpose of this review is to summarize the range of parental beliefs about children's emotions that have been studied, discuss their associations with parent emotion socialization behaviors and child outcomes, and describe how cultural socialization, racial socialization, and gender socialization may connect to parents' beliefs about children's emotions. We evaluate the literature and identify growth edges and future directions for theory and research.

2 Constructs and approaches

Parental beliefs about children's emotions may be defined as their conceptual understanding of children's emotions that may influence evaluations of children's emotions (attitudes), meaning-making about children's emotions (attributions), and emotion socialization behaviors with children (Parker et al., 2012). Attitudes and attributions may be considered as downstream aspects of beliefs (Fiske and Taylor, 1991; McGillicuddy-DeLisi, 1992; McGillicuddy-De Lisi and Sigel, 1995), and research does not always cleanly differentiate attitudes, attributions, and beliefs. Thus, we included research using all these terms in the current review. Similarly, although scientific discourse may distinguish emotions (i.e., sadness, anger, happiness, pride) from affect (feeling states more broadly conceptualized and often considered in regard to two dimensions, positive vs negative valence and low vs high activation or arousal; Schiller et al., 2024), use of these terms is not always precise and we therefore included research on parental beliefs about children's emotions, affect, and/or feelings in the current review.

In the mid-1990s, multiple developmental science research groups considered the role of parental beliefs about children's emotions in emotion socialization processes in conceptual work that sparked continuing research in the field. (Gottman et al. 1996) developed the construct of parental meta-emotion philosophy based on Ginott's (1965) work on communication in parent-child relationships, perusal of lay parenting books, and semi-structured interviews with predominantly White parents in mostly white collar families in the mid-western United States (US). The construct of parental meta-emotion philosophy combines parents' affirming, indifferent, or disapproving beliefs about their own and their children's negative emotions (anger, sadness), parents' skill (or lack thereof) at recognizing their own and their child's emotions, and parents' emotion socialization behaviors that encourage or discourage children's emotional expression and developing emotion regulation skill. An emotion coaching meta-emotion philosophy involves beliefs that children's negative emotions are valuable and provide a teaching opportunity, along with behaviors showing empathy and guidance of children's emotions. An emotion dismissing meta-emotion philosophy involves beliefs that children's negative emotions are unimportant or threatening, along with behaviors ignoring, minimizing, or punishing children's emotions.

Research supports benefits of an emotion coaching meta-emotion philosophy and disadvantages of an emotion dismissing meta-emotion philosophy for children's emotion regulation, behavioral adjustment, and peer relations (see Katz et al., 2012 for a review). Furthermore, research on the Tuning in to Kids suite of parenting programs demonstrates practical utility of the meta-emotion philosophy construct. These evidence-based parent education programs teach parents how to take an emotion coaching approach with their child and consequently improve child emotion understanding and reduce child internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (Havighurst et al., 2010, 2013, 2015; Kehoe et al., 2014, 2020). In the current review, we include research on parents' meta-emotion philosophies when measurement allows differentiation of parental beliefs separate from parental skills and behaviors.

Dunsmore and Halberstadt (1997) discussed family attributions about emotions in their theoretical article addressing how family emotional expressiveness influences children's understanding of emotions and the social world. They proposed that families vary in beliefs regarding the value of emotional experience and expression, capacity for and value of controlling emotional expression, whether absence of emotion is a possible base state, and the extent to which emotions in the family are expressed to manipulate or exert power over other family members. They addressed both positive emotions and negative emotions. Their formulation emphasized that children's meaning-making about emotions will depend on interconnections among family expressiveness, family attributions about emotions, culture, and child characteristics, as well as matches or mismatches in messages conveyed about emotions.

Led by Halberstadt, this research team foregrounded sociocultural contexts in their further work addressing parental beliefs about children's emotions. They took the stance that many different types of parental beliefs about children's emotions may exist, some of which are seen across many sociocultural contexts and some of which are context-specific, and both types and structures of parental beliefs about children's emotions may vary across sociocultural contexts. Parker et al. (2012) used a qualitative, parent-centered, multi-racial approach to identify beliefs about children's emotions that were salient among socioeconomically diverse African American, European American, and Lumbee American Indian parents in the southeastern U.S. Halberstadt et al. (2013) then developed the Parents' Beliefs about Children's Emotions (PBACE) questionnaire to assess the belief categories that had been identified. This questionnaire showed measurement invariance across African American, European American, and Lumbee American Indian parents and across mothers and fathers (Halberstadt et al., 2013). It has since been translated into Chinese, Farsi, Portuguese, Spanish, and Turkish (Azimi et al., 2025; Caiado et al., 2023; Kilic and Kumandas, 2017; Perez Rivera and Dunsmore, 2011; Riquelme et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2023).

(Eisenberg et al. 1998) well-known heuristic model of emotion socialization incorporated both meta-emotion philosophy and family attributions about emotions as constructs supporting parents' emotion-related beliefs as influences on parents' emotion socialization practices, or emotion-related socialization behaviors. Like Dunsmore and Halberstadt (1997), Eisenberg and colleagues acknowledged cultural beliefs about emotions as aspects of culture as well as individual parents' belief systems. A 2020 special issue of Developmental Psychology on the heuristic model showcased the robust body of research demonstrating effects of emotion-related socialization behaviors on children's outcomes (Eisenberg, 2020; Spinrad et al., 2020; see also Brown et al., 2025, for a recent review). Although parents' emotion-related beliefs were not focused on as a growth edge in the special issue, they continue to be included in the heuristic model, both as an influence on parental emotion socialization behaviors and as a direct influence on child outcomes (Eisenberg, 2020). Raval and Walker's (2019) review of cultural influences on emotion socialization processes likewise recognizes the role of parents' emotion-related beliefs in their emotion socialization behaviors and calls for further exploration of cultural variation in parents' beliefs about children's emotions.

Raval and Walker's (2019) discussion of how emotion socialization is embedded within cultures is consistent with two recent extensions of Bronfenbrenner's framework (1977; Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2007). Integrating multiple cultural developmental theories, Vélez-Agosto et al. (2017) describe how culture, which is part of Bronfenbrenner's (1977) macrosystem, structures the everyday interactions that children have with socializers, with whom they have microsystems. Similarly, Rogers et al. (2021) proposed the term m (ai)crosystem to emphasize how the macrosystem, or broader societal or cultural influences, shapes children's microsystems, or their immediate environments. The microsystem includes parental emotion socialization, and the macrosystem includes emotion-related cultural values and expectations. Thus, consideration of parental beliefs about children's emotions within and across sociocultural contexts may be thought of as studying the m (ai)crosystem that influences children's emotional development. Furthermore, Rogers et al. (2021) explain the importance of foregrounding examination of how societal power differentials manifest in developmental processes, which is pertinent to consideration of how gender and racial socialization may be associated with parental beliefs about children's emotions.

3 Types of parental beliefs about children's emotions

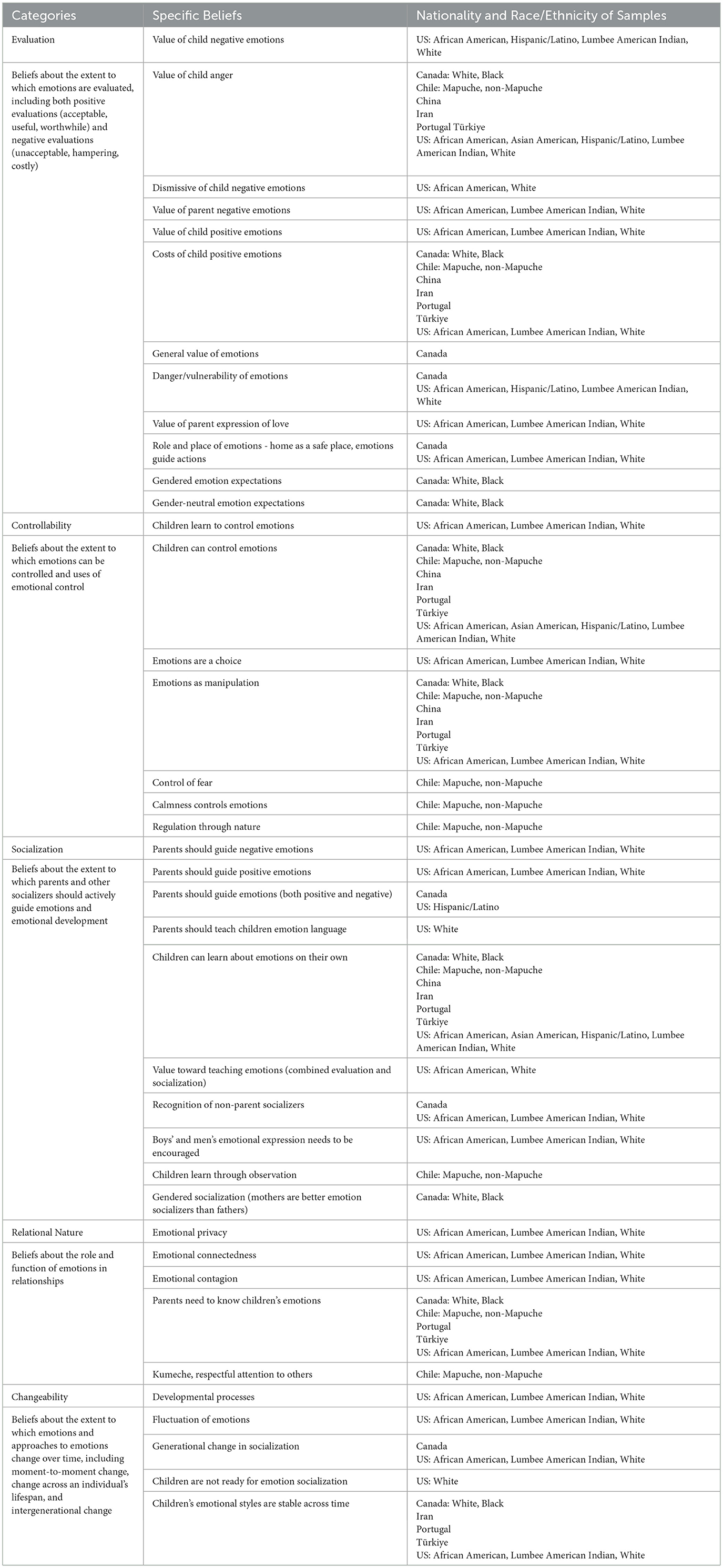

The five belief categories that emerged in Parker et al. (2012) study encompass the range of parental beliefs about children's emotions that have been studied to date and will be used to organize our review of the literature in this article. These categories are: (a) evaluation of emotions, (b) controllability of emotions, (c) socialization of emotions, (d) relational nature of emotions, and (e) changeability of emotions. Evaluation of emotion encompasses the value, danger, or utility of emotions. Examples of specific beliefs within this category are acceptability and costs of children's positive and negative emotions and differences in acceptability of emotions in public vs. private places (Halberstadt et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2012). Controllability of emotions refers to children's capacity to control their emotional experience and expression. Examples of specific beliefs within this category are the extent to which children can control their emotions and spending time in nature to manage emotions (Halberstadt et al., 2013, 2020; Parker et al., 2012). A recent systematic review of emotion belief measures for children, adolescents, and adults showed that evaluation and controllability beliefs are the most commonly measured belief categories (Peter et al., 2025).

Socialization of emotions addresses the role of parents and other socializers in children's emotional development. Examples of specific beliefs within this category are the extent to which parents should guide children's positive and negative emotions and the extent to which parents should expose children to emotion-eliciting situations (Chan, 2011; Halberstadt et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2012). Parental meta-emotion philosophies include both evaluation and socialization beliefs as well as parental emotion-related skills and socialization behaviors. Relational nature of emotions considers the role of emotions in relationships. Examples of specific beliefs in this category are the extent to which children should have emotional privacy and empathic emotional solidarity as a contribution to community harmony (Halberstadt et al., 2020; Parker et al., 2012). Finally, changeability of emotions includes stability or fluidity of emotions. Examples of specific beliefs in this category are how rapidly children's emotions change from moment to moment and the extent to which there has been generational change in approaches to parenting children's emotions (Halberstadt et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2012). Please see Table 1 for a reference guide to these belief categories.

Table 1. Types of parental beliefs about emotions organized within the five Parker et al. (2012) belief categories.

4 Parental beliefs about emotions and emotion socialization behaviors

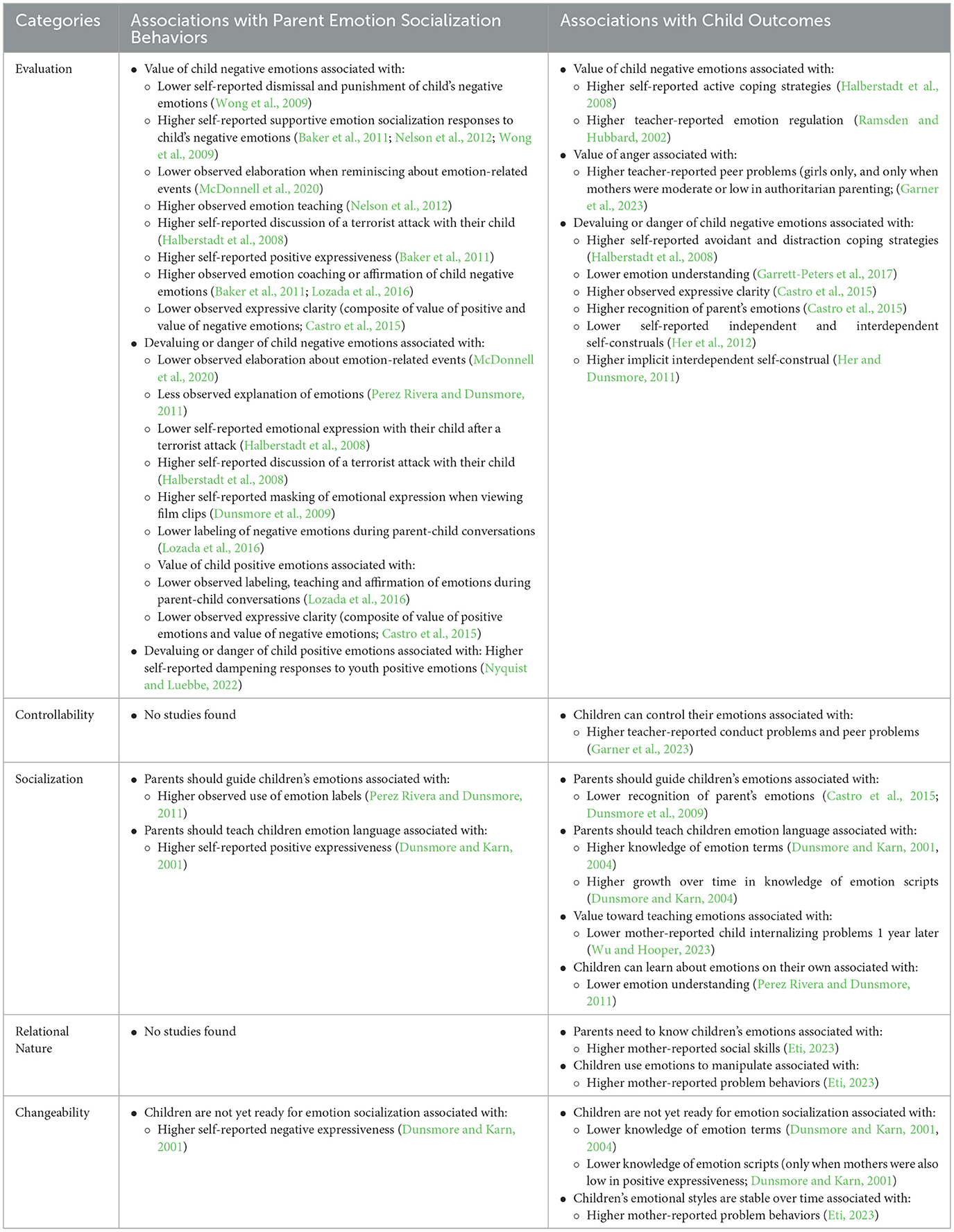

In this section, we describe research examining associations of parental beliefs about emotions with parental emotion socialization behaviors. Parental beliefs about emotions have been characterized as correlates and precursors of parental emotion socialization behaviors. Three common modes of emotion socialization behaviors are parents' modeling of emotion expression, parents' responses to children's emotions that either encourage (supportive responses) or discourage (non-supportive or suppression responses) children's further emotion displays, and parent-child emotion discussion (Castro et al., 2015; Dunbar et al., 2017; Lozada et al., 2016). We first discuss research on evaluation beliefs, then research on the other belief categories. Table 2 provides a summary list of the associations that have been found.

Table 2. Associations of Parental Beliefs about Emotions with Parent Emotion Socialization Behaviors and Child Outcomes.

4.1 Evaluation of emotion

The evaluation category can include multiple specific beliefs or dimensions, such as the value of positive emotions, the value of negative emotions, and the extent to which emotions may be detrimental or harmful for children (Lozada et al., 2016). These dimensions of evaluation beliefs are not bipolar and are not necessarily associated. For example, it is possible for parents to simultaneously believe that positive emotions are valuable and that an excess of positive emotions can be harmful. Theory and research suggest that parents who believe emotions are valuable will engage in behaviors aligned with an emotion coaching meta-emotion philosophy (e.g., encouragement of children's emotional experience and expression). Similarly, parents who believe emotions are dangerous are more likely to engage in behaviors that discourage children's emotional expression and experience, which aligns with an emotion dismissing meta-emotion philosophy (Gottman et al., 1996; Parker et al., 2012; Stelter and Halberstadt, 2011). Below, we present detailed study findings linking parental evaluation beliefs to various emotion socialization behaviors according to children's developmental period.

4.1.1 Early childhood

Study samples included African American and European American mothers and children (Nelson et al., 2012), Latina mothers and children (Perez Rivera and Dunsmore, 2011), mostly White U.S. two-parent families (Wong et al., 2009), and an ethnoracially diverse sample of African American, Hispanic, and White mothers and children, with about 65% of mothers who had maltreated the child (McDonnell et al., 2020). Parental emotion socialization behaviors were self-reported (Nelson et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2009) and observed during mother-child conversation tasks (McDonnell et al., 2020; Nelson et al., 2012; Perez Rivera and Dunsmore, 2011). McDonnell et al. (2020) did not report analyses of associations between mothers' emotion-related beliefs and socialization behaviors accounting for maltreatment status, which raises caution about interpreting findings. However, maltreatment status was not associated with mothers' emotion coaching and emotion dismissing attitudes, so we include the findings McDonnell et al. (2020) reported for their full sample.

Overall, parents who endorse more accepting beliefs about children's negative emotions report lower dismissal and punishment of their child's negative emotion displays (Wong et al., 2009) and more supportive emotion socialization responses (Nelson et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2009). Associations of parental accepting beliefs with observational measures of parental emotion socialization behaviors yielded mixed results, with one study showing a negative association with maternal elaboration during emotion-related mother-child reminiscing, one showing no association with maternal emotion labels and explanations, and one showing a positive association with maternal emotion teaching (McDonnell et al., 2020; Nelson et al., 2012; Perez Rivera and Dunsmore, 2011). Regarding beliefs devaluing negative emotions or finding emotions dangerous, mothers endorsing such beliefs engaged in less elaboration about emotion-related events and less explanation of emotions, though there was no association with maternal emotion teaching (McDonnell et al., 2020; Nelson et al., 2012; Perez Rivera and Dunsmore, 2011). Findings are largely consistent with the heuristic model of emotion socialization and meta-emotion theory (Eisenberg et al., 1998; Gottman et al., 1996), which propose that parental beliefs about emotions shape emotion-related parenting practices.

4.1.2 Middle childhood

Turning to studies with middle childhood samples, study samples included mostly White U.S. two-parent families (Baker et al., 2011), mostly White U.S. parents and children (Dunsmore et al., 2009; Halberstadt et al., 2008), and a racially diverse sample of African American, European American, and Lumbee American Indian families (Lozada et al., 2016; also, Castro et al., 2015 included a subset of the Lozada et al. sample comprised of mostly African American and Lumbee American Indian families). Parental emotion socialization behaviors were self-reported (Baker et al., 2011; Dunsmore et al., 2009; Halberstadt et al., 2008), assessed through nonverbal communication tasks (Castro et al., 2015; Dunsmore et al., 2009) and observed during parent-child conversation tasks (Baker et al., 2011; Lozada et al., 2016).

We provide an extended summary of Halberstadt et al. (2008) study due to its unique focus on parents' emotional expression and discussions with their children following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in the U.S. Parents' belief that negative emotions are valuable was positively associated with discussion of the attacks with their children. Parents' belief that emotions can be dangerous was negatively associated with their emotional expression with their child after the terrorist attack and positively associated with discussion of the attacks with their children (Halberstadt et al., 2008). Because the terrorist attack had widespread media coverage, parents who believe emotions can be dangerous may have thought it was not possible to avoid their child becoming aware of it and that discussion was necessary to minimize detrimental emotions, while also minimizing their own emotional expression to avoid overwhelming their child (Halberstadt et al., 2008). These findings highlight the importance of the situational context for emotion socialization.

Across studies, findings with these middle childhood samples suggest that parental beliefs about emotion do not always translate to effective socialization behaviors. Parents who endorse more accepting beliefs about children's emotions (both positive and negative) showed less effective facial communication of emotions, and those who endorse more accepting beliefs about children's positive emotions engaged in less labeling, teaching, and affirmation of emotions (Castro et al., 2015; Lozada et al., 2016). This pattern of findings differs from what might be expected based on influential approaches that originally addressed children's negative emotions exclusively (Eisenberg et al., 1998; Gottman et al., 1996). Because positive emotions may be considered less potentially problematic than negative emotions, parents' accepting beliefs about child positive emotions may be less connected to active emotion socialization behaviors.

Furthermore, emotion socialization behaviors are less studied for positive than negative emotions. Cross-cultural research with Romanian, Turkish, and White U.S. mothers of toddlers identified three responses: up-regulation (enhancing the child's positive emotions), mirroring (joining or validating the child's positive emotions), and problem-focused (structuring the situation; Corapci et al., 2018). With U.S. adolescent samples, two types of responses to youth positive emotions have been studied: dampening responses that discourage children's further emotion displays, such as ignoring or making fun of children's happiness or pride, and enhancing responses such as giving positive attention to or joining children's excitement or joy (Katz et al., 2014; Lozada et al., 2022; McKee et al., 2015; Nyquist and Luebbe, 2022).

Regarding accepting beliefs specifically about children's negative emotions, the pattern of findings was generally consistent with theory (Eisenberg et al., 1998; Gottman et al., 1996). Parents who endorsed these beliefs reported more positive expressiveness, more supportive emotion socialization responses, and more discussion of a terrorist attack with their child (Baker et al., 2011; Halberstadt et al., 2008). They were also observed engaging in more emotion coaching (Baker et al., 2011).

On the other hand, parents endorsing the belief that emotions can be dangerous reported limiting their emotional expression with their child and engaged in less labeling of negative emotions, though they also reported more discussion with their child about a terrorist attack (Dunsmore et al., 2009; Halberstadt et al., 2008; Lozada et al., 2016). For example, a parent who believes that fear is overwhelming for children might mask their facial expression when watching a scary movie clip and name fearfulness less when discussing everyday family events yet engage in more discussion with their child about a frightening national event to help their child avoid being overwhelmed in an unavoidable situation. Type of parental belief, type of parental emotion socialization behavior, and contextual emotional intensity appear to be important in the connection between parental beliefs about emotion and emotion socialization behaviors.

4.1.3 Adolescence

We found one relevant study with an adolescent sample. With a mostly White sample of U.S. families of 10-17 year olds, parents who more strongly endorsed the belief that positive emotions may have negative consequences reported engaging in more dampening responses to their child's positive emotions (Nyquist and Luebbe, 2022). Further research on parental beliefs about emotions in association with parents' emotion socialization behaviors in response to children's positive emotion will be instrumental in further advancing knowledge of emotion socialization processes.

4.1.4 Summary

Taken together, there is good evidence that parental evaluation beliefs and emotion socialization behaviors are associated, though further research is needed to illuminate findings for parental emotional expression. Across all these studies, results suggest the importance of precision in measurement and consideration of multiple parental beliefs about emotions and emotion socialization behaviors.

4.2 Other belief categories: controllability, socialization, relational nature, changeability

We found few studies addressing associations with parental emotion socialization behaviors for other belief categories. Regarding the socialization of emotions category, two studies included early childhood samples. Latina mothers of preschool-age children who reported stronger beliefs about the importance of guiding children's emotions used more emotion labels when conversing with their children (Perez Rivera and Dunsmore, 2011). Another study with a mostly White U.S. sample showed that mothers with stronger belief in teaching their child emotion language were also higher in positive emotional expressiveness (Dunsmore and Karn, 2001). One study with a middle childhood sample also included parents' belief about guiding children's emotions. Dunsmore et al. (2009) found no association of this belief with parents' masking or expressive clarity in a mostly White sample. Taken together, findings for these studies speak to the salience of verbal and non-verbal modes of emotion socialization and developmental differences between early childhood and middle childhood in regard to children's emotional skills and emotion socialization needs.

Dunsmore and Karn (2001) also addressed changeability beliefs. Mothers who more strongly believed that preschool-age children are not yet ready to learn about emotions were higher in negative emotional expressiveness. This finding suggested that maternal emotion beliefs are conceptually distinct from maternal expressive styles.

Overall, studies addressing the socialization and changeability belief categories provide some evidence for associations of these parental beliefs about emotions with parental emotion socialization behaviors, at least for young children. Future research is needed to strengthen the evidence base, including longitudinal research examining directionality of associations between parental emotion-related beliefs and emotion socialization behaviors and stability or change in parental beliefs about emotions over time. We found no research addressing connections of the controllability and relational nature categories of parental beliefs about emotions with emotion socialization behaviors, suggesting that these categories are ripe for future study.

5 Associations of parental beliefs about emotions with children's outcomes

In this section, we summarize research examining associations of parental beliefs about emotions with child outcomes. As above, we first discuss research on evaluation beliefs, then research on the other belief categories. We conclude this section by describing how this research connects to positive youth development. Table 2 provides a summary list of findings.

5.1 Evaluation of emotions

Most research examining associations of parental beliefs about children's emotions with children's outcomes has focused on the evaluation category. We organize this section by developmental period.

5.1.1 Toddlerhood and early childhood

One study included families with toddlers and used a one-year longitudinal design. With a sample of approximately 75% White and 25% Black U.S. families with 2 year old children, Wu and Hooper (2023) examined maternal and paternal beliefs about the value of emotions and importance of parental guidance of children's emotions (combined evaluation and socialization). For mothers only, higher scores on this belief when children were 2 years old were associated with lower child internalizing problems 1 year later, which is broadly consistent with past literature (Gottman et al., 1996).

5.1.2 Middle childhood

Study samples included mostly White U.S. parents and children (Halberstadt et al., 2008), racially diverse samples of White and Black U.S. families (Garrett-Peters et al., 2017; Ramsden and Hubbard, 2002), and a racially diverse sample of African American, European American, and Lumbee American Indian families (Her et al., 2012; this is the same sample as Lozada et al., 2016, and Castro et al., 2015 included a subset of this sample). Child outcomes were self-reported (Halberstadt et al., 2008; Her et al., 2012), mother- or teacher-reported (Garrett-Peters et al., 2017; Ramsden and Hubbard, 2002), and assessed through established tasks (Castro et al., 2015; Garrett-Peters et al., 2017).

When mothers more strongly endorsed accepting beliefs about negative emotions, children had better emotion regulation, which was associated with lower aggression (Ramsden and Hubbard, 2002). Parents' accepting beliefs about negative emotions were also associated with children's greater likelihood of reporting active coping strategies such as problem-solving and support-seeking following a terrorist attack (Halberstadt et al., 2008).

Findings were mixed for parents' belief that emotions can be dangerous. When parents more strongly endorsed the danger of emotions, children were more likely to report avoidance or distraction coping strategies following a terrorist attack (Halberstadt et al., 2008). Mothers' stronger endorsement of the danger of emotions was also associated with children's lower emotion understanding and was indirectly associated with children's lower classroom adjustment via child emotion understanding (Garrett-Peters et al., 2017). Conversely, parents' stronger endorsement of the danger of emotions was associated with children's better expressive clarity and better recognition of their parent's emotions (Castro et al., 2015).

Another study on parents' belief about the danger of emotions examined children's independent and interdependent self-construals (Her et al., 2012). Whereas independent self-construals describe the self as unique and distinguish the self as an individual, interdependent self-construals describe the self in connection with others and emphasize relationships. Independent and interdependent self-construals co-exist; it is possible for children to be high on both. When parents more strongly believed that emotions can be dangerous, children were lower in both independent and interdependent self-construals, suggesting less age-appropriate focus on traits in their self-descriptions (Her et al., 2012). In general, with the exception of Castro et al. (2015) study addressing non-verbal sending and receiving, findings with middle childhood samples suggest associations of parents' accepting beliefs with beneficial child outcomes and associations of parents' devaluing or danger beliefs with detrimental child outcomes.

5.1.3 Adolescence

Moving to early adolescence, Her and Dunsmore (2011) studied independent and interdependent self-construals with a sample of mostly White U.S. families with a seventh or eighth grade child. Parents' stronger endorsement of the belief that emotions are dangerous was associated with stronger implicit interdependent self-construals for both girls and boys. This differs from Her et al. (2012) results with an explicit measure in a middle childhood sample reported above, suggesting the possibility of developmental change in meaning-making regarding the danger of emotions as youth enter adolescence, a developmental period of growth in emotion regulation (Booker and Dunsmore, 2017).

5.1.4 Summary

Overall, this set of studies suggests benefits of parental beliefs valuing children's emotions for child emotion regulation, coping strategies, and internalizing problems (Halberstadt et al., 2008; Ramsden and Hubbard, 2002; Wu and Hooper, 2023). Findings are mixed for parental beliefs devaluing children's emotions. One study shows associations with better child outcomes (expressive clarity, recognition of parents' emotions; Castro et al., 2015) and another shows associations with worse child outcomes (direct association with lower emotion understanding and indirect association with lower classroom adjustment; Garrett-Peters et al., 2017).

Three studies show associations with outcomes that may be neither beneficial nor detrimental, one addressing coping strategies and two addressing independent and interdependent self-construals. Avoidance and distraction as coping strategies are generally considered less effective than more active coping strategies but may be adaptive in response to a terrorist attack (Halberstadt et al., 2008). Regarding self-construals, although being low in both independent and interdependent self-construal is associated with poor adjustment, relative emphasis on either does not distinguish adaptive functioning (Lam, 2006).

Finally, we note moderation findings in two studies. Mothers' endorsement of the value of anger was associated with peer problems for preschool-age girls depending on mothers' authoritarian parenting (Garner et al., 2023), and parents' endorsement of the danger of emotions was associated with explicit self-construals for early adolescent girls depending on parents' belief about guiding children's emotions (Her and Dunsmore, 2011). These findings suggest the importance of considering multiple aspects of parental belief systems simultaneously.

5.2 Other belief categories: controllability, socialization, relational nature, changeability

Regarding the controllability category, Garner et al. (2023) found that preschool-age children were higher in conduct problems and peer problems when mothers more strongly believed that children can control their emotions. Strong endorsement of this belief may not be developmentally appropriate for early childhood and may be associated with maternal emotion socialization behaviors that suppress emotions without scaffolding emotion regulation development.

Research addressing the belief category of socialization of emotions includes general beliefs about parents' guiding role or children's autonomy as well as specific beliefs about teaching emotion language. When Latina mothers of preschool-age children in the U.S. more strongly believe that children can learn about emotions on their own, their children show lower emotion understanding (Perez Rivera and Dunsmore, 2011). Maternal belief in teaching emotion language was associated with children's better knowledge of emotion terms and greater growth over time in knowledge of emotion scripts in two mostly White U.S. samples of families with children in early childhood (Dunsmore and Karn, 2001, 2004). This specific belief about teaching emotion language may be especially well-suited to foster emotional development in early childhood, when children's skill at verbally identifying emotions and other internal states is rapidly developing (Denham et al., 2007).

Two studies with middle childhood samples showed that parents' stronger belief in guiding children's emotions was associated with children's lower recognition of their parent's emotions (Castro et al., 2015; Dunsmore et al., 2009). Perhaps parental beliefs endorsing their role as emotion socializers fit better with children's developmental readiness in early childhood, whereas parental beliefs allowing children to learn about emotions on their own fit better with the growing salience of autonomy in middle childhood. Alternatively, when children in middle childhood struggle with emotion recognition, parents may increase in their belief that they need to guide their child's emotions.

We turn now to studies examining associations of child outcomes with the relational nature of emotion and changeability of emotions. Regarding relational nature of emotion, Eti (2023) found that mothers' belief that they need to know their child's emotions was associated with better child social skills, whereas mothers' belief that children use emotions to manipulate others was associated with more child problem behaviors in a sample of Turkish families with 3 to 6 year-old children. Regarding changeability of emotions, (Eti 2023) also found that mothers' belief that children's emotional styles are stable over time was associated with more child problem behaviors. With mostly White U.S. samples of families with children in early childhood, mothers' stronger belief that young children are not developmentally ready to learn about emotions was associated with lower child knowledge of emotion terms and moderated the association of maternal positive expressiveness with children's knowledge of emotion scripts, such that children showed the least emotion script knowledge when mothers were low in positive expressiveness and high in the belief that young children are not ready to learn about emotions (Dunsmore and Karn, 2001, 2004). Conversely, with a sample of White U.S. families with a toddler or preschool-age child, King and Legette (2025) found no significant associations of any belief about children's emotions with child social competence, though the study was underpowered for these analyses.

In summary, research addressing the belief categories of controllability, socialization, relational nature and changeability of emotions suggests the importance of considering developmental appropriateness of parents' beliefs. Future longitudinal research will be important to examine directionality of associations and pathways linking parental beliefs about emotions, parent emotion socialization behaviors, and child outcomes.

5.3 Relations to positive youth development

Positive youth development encompasses five characteristics that help youth to thrive and contribute to their communities. These characteristics include (a) competence, or domain-specific skills that promote effectiveness in important life areas, (b) confidence, or overall sense of self-worth, (c) connection, or mutually satisfying relationships, (d) character, or a value system that respects community and cultural standards, and (e) caring, or empathy (Buckingham et al., 2025; Lerner et al., 2006). The outcomes that parental beliefs about emotions are associated with span these characteristics. The ability to clearly express emotions verbally and non-verbally, understanding of emotions in general and accurate recognition of emotions in important relationships in particular, emotion regulation skill, coping strategies, and social skills all contribute to competence and connection. Accurate identification of others' emotions and emotion regulation skill to avoid becoming overwhelmed by others' distress also provides a vital foundation for caring. Independent and interdependent self-construals are different than self-worth yet may inform youths' perspective on their overall self-efficacy and self-esteem. Self-construals may also influence salience of values and behavioral standards that form the basis for character. Thus, the literature on parental emotion-related beliefs and child outcomes suggests that parents' beliefs about children's emotions may contribute to positive youth development.

6 Cultural socialization and parental beliefs about emotions

Researchers have long acknowledged the importance of culture for parental emotion socialization, including parents' beliefs about children's emotions (Dunsmore and Halberstadt, 1997; Eisenberg et al., 1998). In this section, we first define cultural socialization in association with ethnic-racial and gender socialization and discuss pertinent frameworks. We then address within-culture research on parental beliefs about children's emotions with non-Western samples and cross-cultural research in sub-sections focusing on the evaluation category and the other belief categories. We include scholarship with ethnoracially minoritized U.S. samples that specifically focuses on cultural constructs in this section and address other scholarship on ethnic-racial socialization in the next section.

6.1 Cultural socialization processes and associations with ethnic-racial and gender socialization

Cultural socialization refers to intergenerational transmission of cultural values, beliefs, and traditions, as well as positive attitudes toward the culture (Wang and Benner, 2016). Families may participate in multiple cultures, for example when they or their ancestors have emigrated from one society to another, were brought from one society to another through slavery or human trafficking, or experienced occupation and exploitation of their society by another society. When families participate in multiple cultures, cultural socialization includes enculturation processes, or maintenance of heritage culture, as well as acculturation processes, or adoption of strategies to function effectively within the broader or dominant culture (Berry, 2009; Hughes et al., 2006).

Racially-ethnically minoritized families within White-dominated cultures such as the U.S. develop an “adaptive culture” that accounts for both history and current context in association with cultural practices and social position, includes values and norms specific to their group, and directly influences overall familial and parental socialization agendas, which likely encompass parental beliefs about emotion (Coll et al., 1996). Thus, parental beliefs about children's emotion are situated within broader parenting practices and other types of socialization practices including cultural, ethnic-racial, and gender socialization.

6.2 Cultural socialization frameworks

Halberstadt and Lozada (2011) identified multiple frameworks to guide understanding of culture and emotion socialization in infancy. Two of these frameworks are especially pertinent for this paper. First, collectivism/individualism may have implications for parental emotion socialization approaches emphasizing children's development of relational skills relative to self-assertive skills (Halberstadt and Lozada, 2011; see also Friedlmeier et al., 2011). Collectivism and individualism may co-exist and may have many variants cross-culturally (Friedlmeier et al., 2011; Halberstadt and Lozada, 2011; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2008). Furthermore, relational emotional skills (such as sympathy for others' distress) and self-assertive or individualistic emotional skills (such as expression of emotions when goals are thwarted) may each serve communal or individual purposes (Friedlmeier et al., 2011). Parental beliefs about children's emotions may provide insight into parents' views of the functions and meanings of children's emotions and emotional skills.

Second, the value of emotional experience and expression cultural frame directly maps onto the evaluation category of parental emotion-related beliefs and is related to but separable from collectivism/individualism (Halberstadt and Lozada, 2011). Halberstadt and Lozada (2011) focus on variation in the value of positive emotional arousal and expression, which can be inferred from cultural differences in parental responsiveness to infant positive affect and cultural messages about positive affect through children's books. Consistent with Rogers et al. (2021) m (ai)crosystem, larger cultural frames such as collectivism/individualism and value of emotional experience and expression are situated within families' cultural context and may shape parental beliefs about emotion.

Furthermore, Lozada's (2024) theoretical conceptualization describes how Afrocultural ethos, derived largely from Western African traditions, may shape emotional development of Black American youth. Boykin (1983, 1986) hypothesized that much of the emotion-related behavior of African Americans is shaped by their negotiation of the triple quandary of experience, which includes the mainstream American realm, the Black cultural realm, and the racial minority realm. Afrocultural ethos is part of the Black cultural realm, which is historically collectivistic, whereas the mainstream American realm is individualistic. The interplay between historical factors and current context within adaptive culture may adjust to yield a changing range of parental beliefs about children's emotions and emotion socialization behaviors that promote children's development (Coll et al., 1996). Thus, macro-level factors that may influence African American parents' beliefs about emotion are complex.

6.3 Evaluation of emotion

In this section we first discuss research on parental beliefs about children's emotions in non-Western cultures. We then turn to research and theory addressing associations of parental beliefs about emotions with cultural processes for ethnoracially minoritized families within the US.

Several studies have extended PBACE questionnaire (Halberstadt et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2012), testing whether the scales found with U.S. parents also hold with Chilean (Mapuche and non-Mapuche), Chinese, Iranian, Portuguese, and Turkish parents (Azimi et al., 2025; Caiado et al., 2023; Kilic and Kumandas, 2017; Riquelme et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2023). The scales for evaluation beliefs (cost of positive emotions, value of anger) have shown adequate psychometric properties across all these cultures. In addition to translating the PBACE questionnaire into Chinese and testing measurement invariance of the scales, Tan et al. (2023) compared the measurement invariant subscales between Chinese and US. mothers (mostly White) of 6 to 8 year old children. Chinese mothers more strongly endorsed the belief that positive emotions can be costly, whereas US. mothers more strongly endorsed the value of anger belief. This pattern of findings is consistent with previous literature that speaks to Chinese cultural values of harmony and devaluation of anger and intense positive emotions because of perceptions that they disrupt personal relationships and US. mothers' encouragement of emotion expression in social contexts regardless of the potential to disrupt harmony.

Regarding cultural processes and parental emotion-related beliefs for ethnoracially minoritized families within the US., Perez Rivera and Dunsmore (2011) considered maternal beliefs about children's emotions in association with Anglo acculturation and Latino enculturation among Latina mothers of preschool-age children in the U.S. Mothers who were lower in Anglo acculturation held stronger belief that emotions can be dangerous. This finding may reflect the higher individualism that characterizes Anglo US. culture, with more Anglo-acculturated mothers deemphasizing the danger of children's emotions due to perceptions that emotion expression has safe outcomes. Turning to Afrocultural ethos, elements pertinent to the evaluation category include value placed on emotional experience and expression, particularly fostering of Black joy; value placed on authentic self-expression, or expressive individualism; and verve, or preference for high energy and variability in expression (Brown et al., 2025; Lozada, 2024; Lozada et al., 2022). In combination, these works highlight the importance of considering the dynamic role of adaptive culture in parental beliefs about children's emotion among racially-ethnically marginalized groups.

6.4 Other belief categories: controllability, socialization, relational nature, changeability

We begin this section by focusing on a sequence of qualitative and quantitative research with Mapuche and non-Mapuche adults in Chile (Halberstadt et al., 2020; Oertwig et al., 2019; Riquelme et al., 2019). The Mapuche are indigenous to Southern Chile and Argentina. Colonization led to dominant Chilean culture based on Spanish cultural values, and the region where this research took place also includes a substantive population of German descent (Halberstadt et al., 2020). Respect, which fits with the relational nature of emotion category, emerged as a key theme in their qualitative research and quantitative questionnaire development (Oertwig et al., 2019; Riquelme et al., 2019). For example, Kumeche captures emotion ideals that reflect the ‘goodness' of a person within the context of community, such as showing empathic solidarity with others. The controllability category was well-elaborated, including importance of controlling fear, importance of children being calm, and regulating emotions through nature. There was also a new variant in the socialization category, the extent to which children learn about emotions through observation (Riquelme et al., 2019). Mapuche parents and teachers endorsed all five of these beliefs more strongly than non-Mapuche parents and teachers. This series of studies provides a good model of culturally-sensitive research to extend understanding of the range of parental beliefs about children's emotions.

Turning to research addressing versions of the PBACE for Chinese, Iranian, Portuguese, and Turkish parents, the controllability scale (the extent to which children can control their emotions) held across all these cultural groups (Azimi et al., 2025; Caiado et al., 2023; Kilic and Kumandas, 2017; Tan et al., 2023). Tan et al. (2023) found no difference between Chinese and U.S. mothers' endorsement of this belief. The socialization category (autonomy, or the extent to which children can manage emotions on their own) likewise held across all these cultural groups, and Chinese mothers endorsed this belief more strongly than U.S. mothers (Azimi et al., 2025; Caiado et al., 2023; Kilic and Kumandas, 2017; Tan et al., 2023). Thus, measurement of controllability and socialization belief categories was consistent across these cultural groups.

In contrast, there were mixed findings for the relational nature category. Scales in the relational nature of emotions category were manipulation (extent to which children use emotions to manipulate others) and parental knowledge (extent to which parents need to know all of children's emotions). The manipulation scale held for all these groups, and Chinese mothers endorsed this belief more strongly than U.S. mothers. However, the parental knowledge scale held only for Turkish parents, and did not hold for Chinese, Iranian, and Portuguese parents (Azimi et al., 2025; Caiado et al., 2023; Kilic and Kumandas, 2017; Tan et al., 2023). The parental knowledge scale may be culturally-specific, as the idea that children's emotions can only be known if they are outwardly expressed is consistent with individualism (Friedlmeier et al., 2011).

The changeability of emotions category includes a scale assessing belief that children's emotions are stable across time. This scale held only for the Iranian and Turkish parents and did not hold for Chinese and Portuguese parents (Azimi et al., 2025; Caiado et al., 2023; Kilic and Kumandas, 2017; Tan et al., 2023). The construction and experience of time is culturally-bound and understudied; identifying cultural conceptualizations of time in relation to emotion socialization processes is an exciting future direction for the field (Dunsmore and Halberstadt, 2009; Lozada, 2024). Further research is also needed to assess other parental beliefs about children's emotions, identify culture-specific and cross-cultural beliefs, and understand similarities and differences in beliefs within and across cultures.

We conclude this section by addressing these belief categories in association with cultural processes for ethnoracially minoritized families within the U.S. Regarding the socialization category, Perez Rivera and Dunsmore (2011) found a positive association between Latino enculturation and mothers' stronger belief in guiding children's emotions. Authors proposed that the uncertainty avoidance, or discomfort in new situations, that tends to characterize Latino culture may have influenced mothers who were higher in Latino enculturation to foster children's interdependence and more strongly endorse the guidance belief. Furthermore, guidance of children's emotions may include respectful expression and teaching social roles, consistent with the Latino cultural value of respeto or proper demeanor (Harwood et al., 1995). Respeto connects to the relational nature of emotions category, which is also evident in Afrocultural ethos. Beliefs in the relational nature of emotions category may connect to communalism, or consideration of social interconnectedness, and to spirituality, recognizing ancestral connections. Regarding the changeability category, social time perspective, which prioritizes social roles and customs over chronological time, may be relevant. Finally, the controllability category may be evident in the skill in multiple modalities of communication, including emotional expression, that is implicit in the elements of orality, or emphasis on spoken language; and movement, or attention to rhythmic patterns in Afrocultural ethos (Lozada, 2024).

6.5 Summary and future directions

Taken together, studies of the role of culture in parental beliefs about emotion suggest that larger cultural frames may shape parents' individual beliefs about children's emotions, but are not necessarily prescriptive, as there still may be variation in parents' endorsement of macro-level cultural values at the family level and in the connections of their emotion-related beliefs to their emotion socialization practices. While there are some cross-cultural differences in parental beliefs about children's emotion, within-group variation is apparent, and it is important not to overemphasize between-group differences. Researchers can expand the literature by conducting within-culture qualitative research to identify a broader range of beliefs from insider perspectives and considering how larger cultural frames may inform cross-cultural patterns of similarities and differences. Adaptive culture among racially-ethnically minoritized groups and the extent to which parents socialize their children to maintain their culture of heritage and/or adopt mainstream American cultural values are pivotal for beliefs about emotion, which speaks to the importance of assessing cultural socialization along with parental beliefs about emotion and emotion socialization behaviors. Thus, we see the interaction of culture at the macro level and m (ai)cro level as parental beliefs about emotion appear to be grounded in larger cultural frames.

7 Ethnic-racial socialization and parental beliefs about emotions

Ethnic-racial socialization is defined as intergenerational transmission of messages about race and ethnicity and may include cultural socialization as well as socialization values and practices that directly address societal power differentials, such as preparing children for the experience of discrimination, mistrustful attitudes toward other groups, and egalitarian attitudes (Hughes et al., 2006). The rich history of research on ethnic-racial socialization practices is beyond the scope of the current paper (i.e., Anderson and Stevenson, 2019; Hughes et al., 2006; Lesane-Brown, 2006). In this section we first present theory relevant to the interconnection of ethnic-racial socialization and emotion socialization among ethnoracially minoritized U.S. samples, particularly African Americans, then review research on ethnoracial differences in parental beliefs about children's emotions within U.S. samples, organized in a sub-section on the evaluation belief category and a sub-section on the other belief categories.

7.1 Ethnic-racial socialization frameworks and recent theoretical advances

We return to the triple quandary framework of experience for African Americans to further discuss how parental socialization processes among this group reflect the negotiation of the mainstream American realm, the Black cultural realm, and the racial minority realm (Boykin, 1983, 1986). The Black cultural realm was addressed in the cultural socialization section above. The racial minority realm is distinct in addressing how marginalization affects the lives of African Americans. Effects of marginalization lead elders to exercise caution toward negative emotion displays, particularly, and to socialize emotional control or suppression. Thus, parental beliefs about emotion among African American families are shaped by goals to equip children with the tools to navigate multiple contexts by protecting children from oppressive reactions to their negative emotion displays although they believe in the value of their children's negative emotions.

This nuanced dynamic is pertinent to the recent reframing of African American parents' employment of “nonsupportive” responses to children's negative emotions as “suppression” responses (Dunbar et al., 2017). Dunbar et al. (2017) propose that the processes of parental emotion socialization and ethnic-racial socialization are integrated within African American families. In other words, African American parents may engage in emotion socialization behaviors (e.g., suppression responses, higher levels of discussion of negative emotions) that double as race-related strategies, particularly preparing children to be aware of and cope with ethnic-racial bias. Taken together, these practices make up the construct of adaptive racial/ethnic and emotion socialization among African American families. Additionally, African American parents may engage in racialized emotion socialization practices and hold racialized meta-emotion philosophies and beliefs about emotion (Brown et al., 2025; Lozada et al., 2022), which is partially reflected in the review of study findings below.

7.2 Evaluation of emotion

We organized this section according to developmental period. Wu and Hooper (2023) examined associations of parental emotion coaching beliefs (evaluation and socialization categories) with children's later behavior problems among Black and White parents of toddlers. Maternal beliefs at age 2 years were associated with lower child internalizing problems at age 3 years for both Black and White families. A moderation effect was found for Black fathers only, such that children low in baseline respiratory sinus arrythmia (RSA) were lower in later internalizing problems when fathers were high in emotion coaching beliefs whereas children high in baseline RSA were higher in later internalizing problems when fathers were high in emotion coaching beliefs. Authors argue that expressive encouragement accompanied by behavioral control is inherent to culturally specific parenting styles for Black families and contrast Black mothers' roles in emotion socialization processes as expressive encouragers with Black fathers' roles of setting limits for children's emotion expression. These findings speak to the importance of the ethnic-racial context in family emotional climate and emotion socialization processes.

Turning to early childhood, Nelson et al. (2012) found that African American mothers of 5 year old children reported less acceptability of child negative emotions compared with European American mothers. African American mothers (and not European American mothers) also reported more detrimental consequences for their sons' expression of negative emotion compared with their daughters' expression of negative emotion. These beliefs mediated or partially mediated racial differences in responses to children's negative emotions, with African American mothers reporting lower supportive responses to both dominant (anger) and submissive (sadness and fear) emotions and higher suppression responses to anger compared to European American mothers. Authors interpreted findings as reflecting African American families' socialization of behavioral and emotional control as a safety measure for their children who may face discrimination in the mainstream U.S. context and the associated emphasis on obedience in African American family contexts (Kelley et al., 1992).

(Parker et al. 2012) qualitatively explored parental beliefs about emotions among African American (AA), European American (EA), and Lumbee American (LA) Indian parents. Similarities in parental evaluation beliefs across racial-ethnic groups included acceptability of positive and negative emotions in the family home and open expression of positive emotion. AA parents also described overt and covert daily expressions of love, suggesting value placed on positive emotions and confidence in a warm family climate, consistent with the Afrocultural ethos (Lozada, 2024).

Beliefs devaluing emotions showed interesting differences across racial-ethnic groups. Only EA parents emphasized limiting the impact of emotions on decision-making. Perhaps this reflects an individualistic orientation that assumes opposition rather than compatibility of emotions and rational thinking. LA parents expressed preferences against modeling negative emotions. Authors attributed this finding to LA community concern about youth mental health vulnerability. AA parents expressed a desire to limit children's expression of pride. Authors suggested this finding might reflect interdependent cultural values that devalue pride as an ego-focused emotion. At the same time, African American parents employ cultural pride as part of ethnic-racial socialization to encourage children to acknowledge their achievements within the historical context of racism and oppression in the U.S. The nuanced encouragement of both open expression and expressive control that African American families deploy so children can effectively navigate multiple social contexts may apply to positive as well as negative emotions.

7.3 Other belief categories: controllability, socialization, relational nature, changeability

We begin this section by continuing discussion of Parker et al. (2012). For controllability, socialization, and changeability belief categories, Parker et al. (2012) largely found similarities in AA, EA, and LA parents' beliefs. Ethnic-racial differences were found in the relational nature category regarding the belief that children have a right to emotional privacy. EA parents expressed the belief in emotional privacy, LA parents emphasized the importance of knowing their child's feelings, and AA focus groups showed variation, with some communicating belief in emotional privacy and some communicating belief in emotional sharing. EA parents may be able to prioritize children's autonomous decisions about communicating emotions because their racial-ethnic privilege within a U.S. context places children at less risk. For LA and AA parents, who share racially-ethnically minoritized status within a U.S. context, environmental factors such as neighborhoods may influence parental beliefs about emotions as they enact protective socialization goals and practice parental monitoring. Thus, race and ethnicity may be associated with unique manifestations of parental beliefs about children's emotion while at the same time within-group variability is evident.

Lastly, King and Legette (2025) investigated parents' beliefs about racial inequity and their gendered beliefs about children's emotions among White U.S. parents of toddlers and preschoolers. The racial inequity beliefs involved the extent to which parents recognized systemic racial inequities in the U.S. In general, parents' lower endorsement that systemic racial inequities exist was associated with higher devaluing beliefs about anger and positive emotions, manipulation, and autonomy and lower controllability beliefs, suggesting that lack of recognition of systemic racial inequities is linked with wariness about emotions. Authors attributed findings to alignment between White supremacist and patriarchal views among parents. Future exploration of connections of parental beliefs about emotions to broader belief systems may spark more nuanced theory development.

7.4 Summary and future directions

Taken together, ethnic-racial socialization practices are vital among racially-ethnically minoritized families and there is evidence of both similarities and differences in parental beliefs about emotion across racial-ethnic groups. These racial-ethnic differences in parental beliefs about emotion appear to be more associated with the valence of emotion than type of belief. Furthermore, there is variation in parental beliefs about emotion within racial-ethnic groups. Research and theory provide intriguing glimpses of the potential role of parental beliefs about children's emotions in combination with ethnic-racial socialization. At the same time, parental beliefs about children's emotions do not determine parents' ethnic-racial and emotion socialization behaviors.

Focusing on the example of African American families, we propose two factors for future research. First, valence of emotions may impact how parental beliefs about emotion translate to parental emotion socialization behaviors. Research demonstrates the realistic fear among African American mothers of potentially negative or adverse social consequences for their children expressing negative emotion, which is associated with greater engagement in suppression responses (Dunbar et al., 2022a,b; Nelson et al., 2012). Although negative emotions are more likely than positive emotions to receive disapproving attention, Parker et al. (2012) found that some African American parents were proponents of restricting their children's positive emotion displays, suggesting that suppression responses may generalize to positive emotions in some circumstances.

Second, developmental considerations may influence how parental beliefs about emotions translate to parental emotion socialization behaviors. Early childhood may be especially salient for African American emotion socialization processes because children begin to interface with public contexts such as classroom settings that are racialized (Dunbar et al., 2022a). African American parents believe it is important to equip their children with the socioemotional tools to adapt to different contexts (Dunbar et al., 2017), which may originally manifest during children's transition into school and become more salient in adolescence (Lozada et al., 2022). Thus, researchers may consider studying the evolution of parental emotion-related beliefs and behaviors across different developmental periods.

8 Gender socialization and parental beliefs about emotions

The influence of gender role norms on parents' beliefs about children's emotions has long been acknowledged (Dunsmore and Halberstadt, 1997; Eisenberg et al., 1998). In this section we address the confluence of gender socialization and parental beliefs about children's emotions in regard to differences in maternal and paternal beliefs about children's emotions, differences in parental beliefs about emotions according to child gender, and research directly addressing gender-typed beliefs about emotions.

8.1 Evaluation of emotion

Regarding the evaluation category of beliefs, there is mixed evidence regarding differences in maternal and paternal beliefs about children's emotions. Early childhood study samples included mostly Mexican American two-parent families (Gamble et al., 2007) and mostly White U.S. two-parent families (Wong et al., 2009). Gamble et al. (2007) found no differences in maternal and paternal accepting or dismissing beliefs about children's negative emotions, whereas Wong et al. (2009) found that mothers endorsed more accepting beliefs about children's negative emotions compared with fathers.

One study with mostly White two-parent families included a middle childhood sample (Baker et al., 2011). Baker et al. (2011) found that mothers more strongly endorsed accepting beliefs about negative emotions compared with fathers, and that mothers and fathers did not differ in their dismissing beliefs about negative emotions. For both mothers and fathers, only dismissing attitudes were correlated with child social competence, though in different directions. Mothers' dismissing beliefs were associated with children's lower social competence, whereas fathers' dismissing beliefs were associated with children's higher social competence (Baker et al., 2011). Additionally, fathers showed more cohesion among emotion beliefs, supportive responses, and emotion discussion than mothers did. Baker et al. (2011) interpreted this finding in light of evolving notions surrounding manhood and fatherhood and acknowledged fathers' historically limited involvement with their children, which may allow for greater latitude to choose how they will engage with their children emotionally compared with mothers. Future research examining profiles of maternal and paternal emotion-related beliefs within families may illuminate whether the emotion socialization behaviors that stem from dismissing beliefs are different for mothers and fathers or are perceived differently from mothers compared with fathers.

There is likewise mixed evidence regarding differences in parental beliefs evaluating children's emotions according to child gender. Wong et al. (2009) report no differences in parents' accepting beliefs according to child gender or the interaction of child and parent gender. Baker et al. (2011) report more accepting beliefs for fathers of sons compared with fathers of daughters, and no differences between mothers of sons compared with mothers of daughters.

Taking a qualitative approach with a mostly White Canadian sample of parents with children in middle childhood, Thomassin et al. (2019) found that both mother and father focus groups tended to emphasize similarities in girls' and boys' emotional experiences while acknowledging gendered societal expectations that inhibit boys' emotional expression relative to girls' emotional expression, especially for vulnerable emotions. In their subsequent questionnaire development research, Thomassin et al. (2020) identified separate factors for both gendered acceptability of negative emotions and gender-neutral acceptability of emotions. For both girls and boys, when parents less strongly endorsed gendered beliefs about emotion expression and more strongly endorsed gender-neutral beliefs about expression children had better emotion regulation and fewer behavior problems (Thomassin et al., 2020). Interestingly, using an implicit measure of parents' gendered beliefs with this sample, Thomassin et al. (2020) found that mothers showed more favorable responses toward girls' compared with boys' expressions of sadness and anger, whereas no effect was found for fathers. These responses may reflect mothers' implicit endorsement of stereotypes, or same-gender identification. Future research will be needed to investigate correlates of implicit and explicit gendered beliefs about children's emotions for mothers and fathers.

We also note two studies showing that associations of parental evaluation beliefs about children's emotions with child outcomes were moderated by child gender. One study included an ethnoracially diverse sample of Asian, Black, Latinx and White U.S. families with a preschool-age child (Garner et al., 2023). Detrimental effects of mothers' belief about the value of anger on peer problems were found only for girls and only when mothers were moderate or low in authoritarian parenting. Authors suggest that gender-typed norms accepting anger for boys and deprecating anger for girls may influence teachers' perceptions of peer problems, and that the impact of high authoritarianism may overwhelm emotion socialization effects. Another study addressed independent and interdependent self-construals with a sample of mostly White U.S. families with a seventh or eighth grade child (Her and Dunsmore, 2011). When parents were low in both belief about the danger of emotions and belief about guiding emotions, girls were low in the explicit measure of both independent and interdependent self-construals. There was no effect for boys. Perhaps girls may benefit when parents hold at least one type of belief that would lead them to attend to their daughters' emotions (Her and Dunsmore, 2011). Across these studies, moderation findings showing effects of parental evaluation beliefs on outcomes for girls but not boys may reflect gendered stereotypes in the U.S. that make emotions more salient for girls and women, both in regard to their own perspectives and in regard to others' perspectives about them (Shields et al., 2018).

8.2 Other belief categories: controllability, socialization, relational nature, changeability

Regarding the socialization category, stronger maternal belief in children's autonomy in learning about emotions was associated with preschool-age girls' (but not boys') higher peer problems (Garner et al., 2023). Perhaps the tendency for girls to show earlier development of self-regulation than boys misleads parents with stronger child autonomy beliefs about emotions, resulting in girls receiving less support for peer relations than they need (Montroy et al., 2016). (Thomassin et al. 2019, 2020) identified a parental belief that mothers are better at emotion socialization than fathers. For both mothers and fathers, stronger endorsement of this belief was associated with lower supportive reactions to negative emotions and higher unsupportive reactions to both positive and negative emotions as well as lower child emotion regulation and higher child behavior problems (Thomassin et al., 2020).

On a different note, both Parker et al. (2012), with a multiracial U.S. sample, and Thomassin et al. (2019), with a mostly White Canadian sample, found themes emphasizing generational change in men's expressiveness and recognizing the importance of encouraging boys to express their vulnerable emotions. Because this belief has to do with generational change as well as socialization of emotions, it also fits with the changeability category of parental beliefs about children's emotions. Also in the changeability category, King and Legette (2025) found that mothers more strongly endorsed the belief that boys' emotions endure for long periods compared with fathers. There was a non-significant trend in the same direction for girls' emotions (King and Legette, 2025). This may be a variant of the belief that children should move on quickly from negative emotions, which was expressed only by fathers previously Parker et al. (2012).

Regarding the relational nature category, in qualitative work some parents expressed a belief that girls are more likely than boys to express emotions as a way of connecting with others (Thomassin et al., 2019). Perhaps this may suggest gendered expectations about the functions that emotions can serve, regardless of whether there are gendered expectations about acceptability of emotions. Finally, there was no evidence of gender-typed beliefs in the controllability category in the literature reviewed. Because such beliefs have to do with children's capacity to control their emotional experience and expression, future research examining gender-typed controllability beliefs in toddlerhood and adolescence may be useful, as these developmental periods are particularly associated with emotion regulation challenges.

8.3 Summary and future directions

Although much of this section has focused on parent and child gender differences in parental beliefs about children's emotions and their correlates, we recognize that such group comparisons may not only obscure widespread similarities across gender but also risk reinforcing essentialist approaches to research on gender and emotions (Shields, 2020). Essentialist views of gender assume a male/female binary with contrasting characteristics that are biologically determined, undervaluing environmental demands that promote conformity to gender norms. Constructivist and intersectional approaches to gender consider those environment demands in association with contextual variation and individuals' multiple social identities (such as gender, race, and social class), illuminating the social construction of gender and emotion and the association of gendering emotions with social power and inequality (Shields et al., 2018; Shields, 2020).

Overall, the body of research reviewed in this section provides evidence with mostly White samples for a parental belief that vulnerable emotions such as sadness and fear are more acceptable for girls compared with boys and hints at intriguing nuances in parents' views about gender and emotional duration and about how relationships feature in girls' and boys' emotional experience. Future research with more ethnoracially, culturally, and socioeconomically diverse samples is needed to better understand contextual bounds of gendered beliefs about children's emotions and how parents' emotion-related beliefs may be associated with other aspects of emotion socialization and gender socialization. Thomassin et al. (2020) questionnaire will be a useful foundation for these future research directions. As the field learns more about transgender children's gender identity development (deMayo et al., 2025), another key future direction will be examining links of parental beliefs about emotions with parents' gender affirming socialization attitudes and practices. It will also be important for future research to examine parents' beliefs about children's emotions in association with other beliefs regarding gender. When parents hold stronger essentialist beliefs about gender, they are higher in overprotection and controlling parenting (Eira Nunes et al., 2025). Essentialist gender beliefs and traditional masculinity beliefs may also be associated with parents' emotion-related beliefs and socialization behaviors (Cherry and Gerstein, 2021).

9 Evaluation of the literature

9.1 Well-studied areas