- 1Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, United States

- 2University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Psychology, Madison, WI, United States

- 3Department of Psychology, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, United States

Introduction: During the preschool years, children begin to distinguish fantasy and reality. In the United States, this is often the time parents encourage belief in certain fantasy figures (e.g., Santa Claus) while discouraging belief in others (e.g., witches). Although prior research primarily focusing on Santa Claus provided why parents support that belief, less is known about their support of childhood fantasy beliefs more broadly. Moreover, the role of child and parental factors in shaping parents' decisions to support such beliefs has not been investigated in detail. To address these gaps, we conducted two studies. We also examined whether parental support, as well as parents' own and their children's beliefs in fantasy figures, have changed over the past 30 years.

Methods: We recruited parents of children aged 3–8 years living in the United States for both studies. Study 1 (n = 39) was an in-person interview study in which parents reported their own and their child's fantasy beliefs, their views on childhood fantasy beliefs, and their motivations for supporting fantasy beliefs. Study 2 (n = 486) was an online survey adapted from Study 1, designed to examine how individual factors relate to parental support of fantasy beliefs.

Results: Overall, the results suggest that parents support childhood fantasy beliefs to promote their child's wellbeing by creating an exciting childhood, fostering cultural understanding, and protecting children from negative emotions (e.g., fear). These findings were consistent across the two studies, although some variations were observed in parental reports of their own and their child's beliefs and their support when compared with a study from the 1990s. Parents' decisions to support fantasy beliefs were associated with their attitudes toward fantasy beliefs, their religiosity, and their child's age.

Discussion: Parents viewed fantasy beliefs as a normal part of childhood and promoted them for their perceived benefits to the child. However, the current findings suggest that parents navigate supporting these beliefs in complex and adaptive ways, balancing cultural norms, personal experiences, children's developmental considerations, and religious values, to determine which beliefs they encourage or discourage in their children's imaginative lives. Differences observed over the past 30 years in children's beliefs and parental support are discussed in relation to broader cultural changes.

Introduction

By the preschool years, children begin to distinguish between fantasy and reality (Woolley and Cox, 2007) and often show skepticism toward surprising claims or events that seem to be out of the ordinary (Hermansen et al., 2021; Ronfard et al., 2021; Shtulman and Carey, 2007). Yet, this period of childhood is also associated with magical beliefs, including the belief that certain fantasy figures might be real (Rosengren and French, 2013; Rosengren and Hickling, 1994). For example, children between the ages of 4 and 6 years in the United States are often reported by their parents to believe in the reality of fantasy figures such as Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny (e.g., Rosengren et al., 1994; Rosengren and Hickling, 1994). Prior research suggests that parental endorsement plays a role in the development of these beliefs (e.g., Anderson and Prentice, 1994; Goldstein and Woolley, 2016; Woolley et al., 2004). However, it remains unclear why parents actively promote such beliefs, especially during a developmental period when children are forming a more advanced ontological understanding of reality (e.g., distinguishing what is real from what is not real). The current studies aimed to explore parents' reasoning for encouraging and discouraging fantasy beliefs in their children and to examine how individual factors relate to these decisions. We also examined whether parental encouragement and reports of children's fantasy beliefs have changed over time by comparing our findings with those from earlier research conducted over 30 years ago (Rosengren et al., 1994).

Children's fantasy beliefs and parental influence

Around the ages 4 or 5, children can distinguish between real and fantastical events (e.g., Samuels and Taylor, 1994; Woolley and Cox, 2007), real and fantastical characters (e.g., Corriveau and Harris, 2009; Skolnick and Bloom, 2006), and even between different fantastical worlds (Martarelli et al., 2015; Skolnick and Bloom, 2006). They can also apply this understanding to narrative contexts, recognizing that a fantastical ending is more appropriate for a story involving a familiar fantastical character, and that realistic endings are more appropriate for stores with a real character (Ho et al., 2024). They also become skeptical and consider an event or figure as unrealistic when it contradicts their existing knowledge (Woolley and Ghossainy, 2013). For instance, when presented with claims that conflict with their intuition or experiences, children may seek additional information to assess the credibility of those claims (Hermansen et al., 2021; Ronfard et al., 2021). Older children (ages 6–7) are generally more skilled at detecting such inconsistencies than younger children (ages 4–5), as these evaluative skills improve with age (Hermansen et al., 2021; Ronfard et al., 2021). Nonetheless, many children continue to believe in fantasy figures like Santa Claus even while acknowledging that these figures possess extraordinary or impossible properties (Boerger, 2011; Shtulman and Yoo, 2015). In fact, parents in the United States often report that preschool-aged children believe in fantasy figures capable of performing supernatural acts (e.g., Santa Claus who rides on a sleigh led by flying reindeers; Anderson and Prentice, 1994; Clark, 1995; Goldstein and Woolley, 2016; Mills et al., 2024; Prentice et al., 1978; Rosengren et al., 1994; Rosengren and Hickling, 1994). This persistence in fantasy beliefs is likely supported by strong social reinforcement from adults.

Research has shown that children often rely on the testimony of others, particularly when learning about phenomena and events that are not directly observable (e.g., germs, what happens after death, the existence of God; Harris and Koenig, 2006). Since the existence of fantasy figures cannot be verified through direct observation, adult testimony, especially that of parents, can play an important role in shaping children's fantasy beliefs (Boerger et al., 2009; Woolley et al., 2004). To better understand how parents support such beliefs, prior research has examined parental encouragement of belief in Santa Claus. Studies have found that parents often provide extensive verbal testimony (e.g., Santa Claus lives at North Pole) and promote specific behaviors (e.g., leaving cookies and milk for Santa Claus, visiting Santa Claus at malls) to convince their children of Santa Claus' existence (Anderson and Prentice, 1994; Goldstein and Woolley, 2016; Mills et al., 2024). Research shows that this parental affirmation of fantasy figures parallels the way parents convey information about unobservable phenomena (e.g., germs, viruses, electricity) and historical figures (e.g., Columbus, Mother Teresa; Canfield and Ganea, 2014). These findings suggest that parents often present fantasy figures as real, and that this support may contribute to children's belief in these figures. Indeed, parents in the United States report that children between the ages of 4 and 6 are more likely to believe in culturally endorsed fantasy figures that they actively encourage (e.g., Santa Claus, the Tooth Fairy, the Easter Bunny) and less likely to believe in culturally non-endorsed figures that parents discourage (e.g., ghosts, witches; Rosengren et al., 1994; Rosengren and Hickling, 1994).

Why might parents encourage belief in something they know is not real? Research on Santa Claus suggests that parents do so to share a cultural tradition and foster a magical childhood experience (Anderson and Prentice, 1994; Clark, 1995; Goldstein and Woolley, 2016). Additionally, parents' own desires may also play a role. For instance, some parents continue to support belief in Santa Claus even for older children (Goldstein and Woolley, 2016), despite the fact that children generally stop believing around age of 7–8 (Anderson and Prentice, 1994; Mills et al., 2024). As children grow older, parents may continue to promote activities that reinforce their child's fantasy beliefs (e.g., visiting a live Santa at a mall; Goldstein and Woolley, 2016). This ongoing support may reflect a parental desire to prolong the magic of childhood for as long as possible (Clark, 1995; Goldstein and Woolley, 2016). At the same time, some parents are reluctant to encourage culturally endorsed beliefs. Their hesitation may stem from concerns that such beliefs distract children from the true meaning of related cultural events (e.g., Santa Claus for Christmas) and/or from the belief that promoting such beliefs involves lying to children (Anderson and Prentice, 1994).

Taken together, prior research suggests that parents often actively encourage certain fantasy beliefs, but there are individual differences in how they approach this encouragement. While some studies have explored parental encouragement and discouragement of belief in Santa Claus, it remains unclear why parents choose to encourage or discourage belief in fantasy figures more broadly and how individual parent and child factors relate to these decisions.

Debate on whether to encourage childhood fantasy beliefs

Although parents often encourage belief in certain fantasy figures, the value of fostering such beliefs has been debated. One argument against encouraging childhood fantasy beliefs is that it involves promoting a lie, which may undermine children's rational thinking and, potentially, their moral reasoning (Johnson, 2010). Encouraging these beliefs often requires deceiving the child, and parent's systematic lying behavior has been shown to relate to negative consequences for children (e.g., children lying, psychological adjustment problems; Hays and Carver, 2014; Santos et al., 2017; Setoh et al., 2020). So, parental deception in promoting fantasy beliefs throughout childhood could lead to a negative impact on children's development.

Johnson (2010) has also argued that parents' deceitful actions (e.g., encouraging false beliefs) could negatively affect children's trust in their parents and potentially undermine their religious beliefs. When children discover that their parents deceived them into believing in fantasy figures, they may go through a period where they may lash out against their parents and question the entire notion of Christmas (Kowitz and Tigner, 1961). This may not only negatively impact the parent-child relationship but also the credibility of parent's testimony about God. Because children rely on others' testimony to understand the existence of God (Harris and Koenig, 2006), the mistrust created by encouraging false beliefs could hinder their willingness to believe their parents' testimony about God. This argument aligns with the view of Fundamentalist Christian parents, who believe the Santa Claus myth undermines children's belief in God (Clark, 1995) and who generally hold negative attitudes toward fantasy (Taylor and Carlson, 2000).

Contrary to arguments about the negative impact of parental support for fantasy beliefs, research has shown that although some children and adults reported experienced negative emotions (e.g., betrayal, anger) after discovering the truth about their childhood fantasy beliefs, these reactions are typically short-lived and have little lasting consequences (Anderson and Prentice, 1994; Mills et al., 2024). Furthermore, most adults reported that discovering the truth about Santa Claus did not negatively affect their trust in their parents or their attitude toward God (Mills et al., 2024). So, while promoting fantasy beliefs involves deception, it does not appear to have a lasting negative impact on children, at least as reflected in their retrospective reports in adulthood.

Prior research provides initial evidence that fantasy beliefs, specifically belief in Santa Claus, may not have negative long-term effects on children. However, it remains unclear how parents' own childhood experiences with fantasy beliefs influence their decisions to support such beliefs in their own children. Since parents ultimately decide whether to encourage or discourage these beliefs (though cultural influences also play a role), their personal views and experiences are likely to be important factors. In particular, parents' beliefs about the developmental impact of fantasy beliefs, including its potential effects on religious belief, may shape their willingness to support certain fantasy beliefs. Therefore, it is important to explore the motivations behind parental support for both culturally endorsed and non-endorsed beliefs and how individual factors (e.g., parent's own experiences with fantasy beliefs, their views of fantasy beliefs, the child's age) influence these decisions. Such an exploration could offer a more comprehensive understanding of how parents perceive childhood fantasy beliefs and how their own experiences shape the support they provide for these beliefs in their children.

Current study

The primary purpose of the current studies was to explore why parents encourage or discourage common fantasy beliefs (e.g., Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny, ghosts, monsters). A secondary purpose was to examine how parental encouragement and discouragement for fantasy beliefs relate to child (i.e., age) and parental (i.e., parents' own experience with fantasy beliefs, parents' religiosity) factors. Given that most prior research on parental support of fantasy beliefs was conducted in the early 1990s (e.g., Anderson and Prentice, 1994; Rosengren et al., 1994), we also sought out to examine the stability of these practices over the past 30 years. This comparison is particularly important in light of significant cultural shifts during that time. Today's children are exposed to digital technology at earlier ages (often before age 2; Mann et al., 2025) and fantastical content in children's media in recent years has become increasingly prevalent (Goldstein and Alperson, 2020; Taggart et al., 2019). These changes may influence both children's engagement with fantasy and parents' attitude toward it, prompting our investigation into whether parental practices have changed over the past 30 years.

In Study 1, parents were interviewed in person about their reasons for encouraging or discouraging their children's fantasy beliefs. We also explored parents' broader perceptions of fantasy beliefs, including their views on the impact of such beliefs in adulthood and their potential influence on the development of religious belief in children. Based on the findings of Study 1, Study 2 employed a larger-scale parent survey to further examine how individual factors (i.e., child age and parent's attitude toward fantasy beliefs) relate to parental support. Additionally, we compared findings from the two studies [Study 1 (2012), Study 2 (2024)] with earlier work by Rosengren et al. (1994) to assess potential changes in parental support for fantasy beliefs over time. Although more recent studies (Goldstein and Woolley, 2016; Mills et al., 2024) have examined children's beliefs, they have primarily focused on belief in Santa Claus rather than on fantasy beliefs more broadly. This focus, whether through directly asking children about their belief or asking parents how they encourage belief in Santa Claus, limits the comparability of those studies to the current study. Therefore, we used Rosengren et al. (1994) as a primary point of comparison.

Study 1

Prior work by Rosengren et al. (1994) and Rosengren and Hickling (1994) demonstrated that parents encourage some fantasy beliefs while discouraging others. Although previous research has shown that parents often promote beliefs in culturally endorsed fantasy figures, particularly Santa Claus, as a way to share cultural traditions and foster a sense of magic in childhood (Anderson and Prentice, 1994; Clark, 1995; Goldstein and Woolley, 2016), it remains unclear why they choose to encourage or discourage fantasy beliefs more broadly. The current exploratory study aimed to investigate the reasons behind parents' encouragements and discouragements of their children's beliefs in common fantasy figures through in-person interviews. We also examined parents' broader perspectives on childhood fantasy beliefs by asking about their own childhood experiences, their reflections on how those beliefs may have impacted their adulthood, and their views on how fantasy beliefs might relate to the development of religious belief in children.

Method

Participants

A total of 39 parents with a child between the ages of 3–8 years were recruited from a lab-based participant database (MParent = 37.41 years, SD = 4.05, range = 31–46 years, 36 mothers; MChild = 5.15 years, SD = 1.61). This age range was chosen based on past research showing that children of this age hold beliefs in the reality of fantasy figures (Phelps and Woolley, 1994; Rosengren and Hickling, 2000). Since this study was exploratory in nature, we did not conduct a power analysis. Instead, we aimed to recruit about 40 parents following a prior study that examined parents' encouragement of children's fantasy beliefs (Rosengren and Hickling, 1994). Most parents (85%, n = 33) identified their race as Caucasian/White and reported being affiliated with Christianity (59%, n = 23). Additionally, the majority were highly educated, with 95% (n = 37) holding at least a bachelor's degree. See Supplementary file S1 for detailed demographic information.

Procedure and measures

Each parent was invited to a university laboratory located in a Midwestern city in the United States for an in-person interview. Parents were first asked to provide demographic information on their gender, age, race and ethnicity, and level of education, and their child's gender and age. They were then asked about: (1) their child's fantasy beliefs (i.e., the child's belief in fantasy figures, the parents' support for fantasy beliefs and their reasons, and how the child should discover the truth about fantasy beliefs), (2) their own past beliefs and present views on encouraging fantasy beliefs (i.e., their childhood beliefs and current opinions); and (3) their specific views on the influence of fantasy belief on the development of religious belief in children. The interview consisted of 17 questions, some of which included follow-up questions. All interviews were conducted by an experimenter and audio recorded for later transcription and coding. On average, interviews took about 20 minutes, and each parent received $10. Interviews were conducted between July and November of 2012.

Questions related to child's fantasy beliefs

Parents were asked whether their child currently believes in the following fantasy figures: Santa Claus, the Tooth Fairy, the Easter Bunny, Ghosts, Monsters, Witches, Imaginary friend(s), and Other. For Other, they were asked to specify the other fantasy figure(s). They were then asked “which of the fantasy beliefs [they] encourage/discourage” and to explain their reasons. To better understand why parents encourage fantasy beliefs, they were asked whether they believed “there are benefits to encouraging or discouraging these beliefs” and “if so, what these benefits [are]”. Additionally, they were asked whether “[they] plan to end encouragement in these beliefs,” and “if so, at what age.” Finally, parents were asked “how [they think] children should discover the truth,” with response options including: “parents should be the ones to tell them,” “they should find out on their own,” “they should never discover the truth,” and “other (please specify).”

Questions on parents' past beliefs

Parents were asked about their own childhood beliefs in the same format as for their child's beliefs. Then, they were asked two open-ended questions: “[at] what age did you stop believing?” and “how did you react when you discovered the truth?” Finally, parents rated how their childhood fantasy beliefs affected their adult life using a 5-point Likert scale (“How do you think having these fantasy beliefs as a child affected you in your adult life?”; 1 = “very negatively” and 5 = “very positively”).

Questions on religion

Parents were asked “how important religion [is] in [their] life” using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “not at all important” and 7 = “extremely important”) and how frequently they attend religious services on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “never” and 5 = “once a week”). Finally, parents responded to an open-ended question about the influence of fantasy beliefs on the development of religious belief in children: “In general, how do you feel having fantasy beliefs as a child affects that child in terms of developing religious beliefs?”

Demographic questions

Parents were asked to report on their age, gender, race/ethnicity, education level, and religious affiliation. They were also asked to report their child's age and gender.

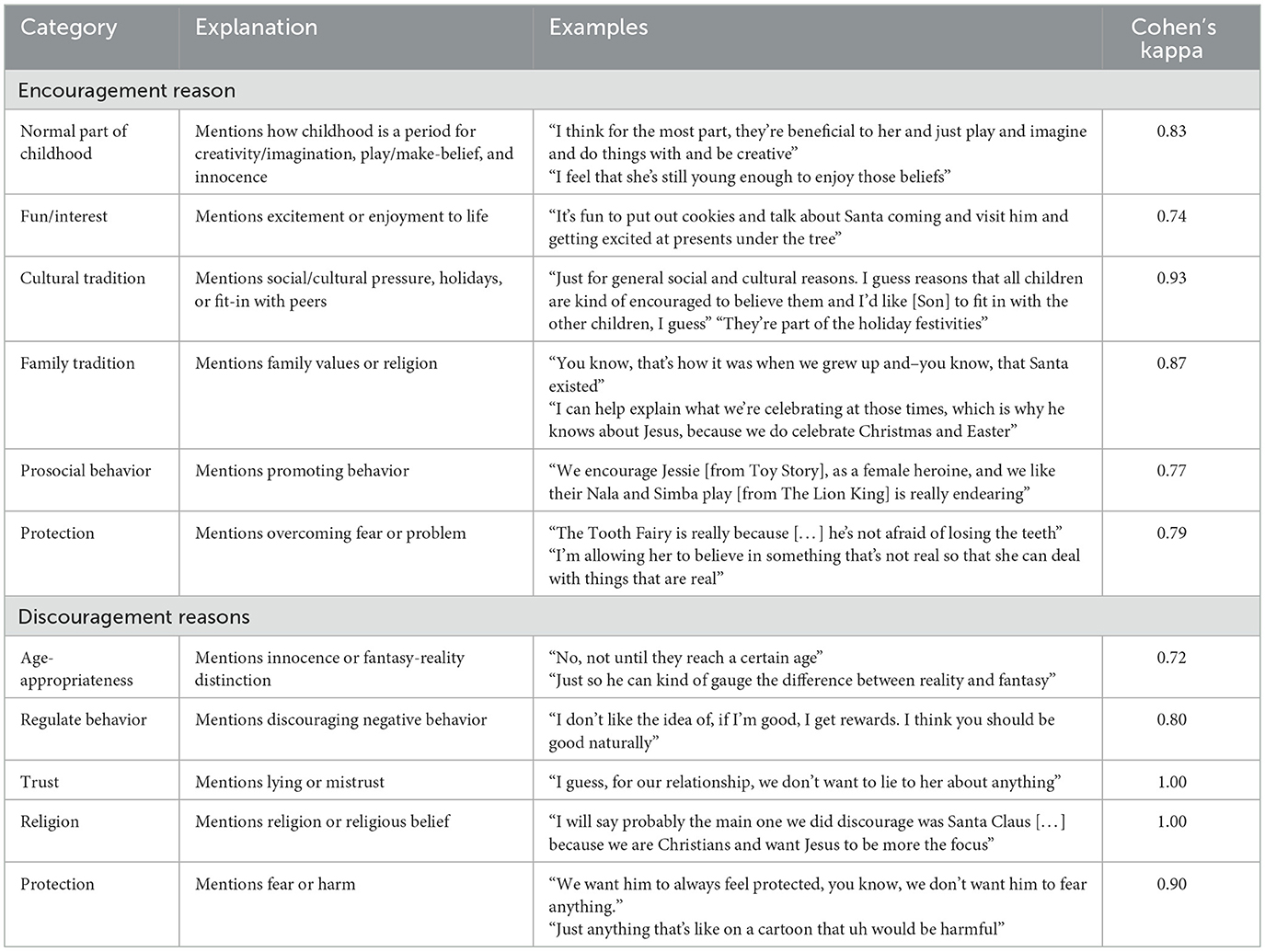

Response coding

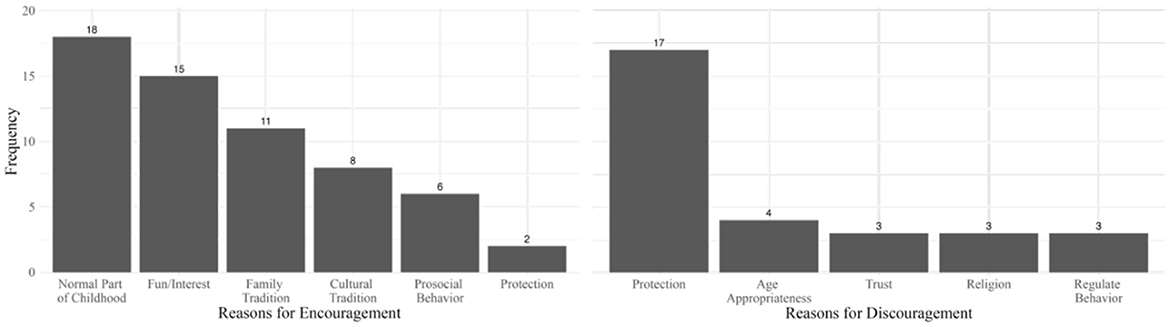

Coding for parents' responses to questions about why they encourage and discourage fantasy beliefs was adapted from Anderson and Prentice (1994). While Anderson and Prentice (1994) focused specifically on parents' attitudes toward Santa Claus, the current study asked parents to provide reasons for both culturally endorsed and non-endorsed beliefs. As a result, we modified the original categories to better reflect our data. Specifically, we combined some categories (e.g., “Fantasy is good” and “Children should be allowed to believe as long as they wish to” were combined into “Normal part of childhood”), broadened others (e.g., “Draws attention away from other reasons for Christmas” was broadened to “Religion”), and added new categories (e.g., Protection) based on themes that emerged in the current dataset. Parental responses related to encouragement were coded into the following categories: normal part of childhood, fun/interest, cultural tradition, family tradition, prosocial behavior, and protection. Parental responses related to discouragement were coded into the following categories: age-appropriateness, regulate behavior, trust, religion, and protection. Two independent coders, who were not involved in conducting the interviews, coded the responses to assess interrater reliability. Cohen's kappa values for all coding categories were 0.72 or higher (kappa values above 0.61 are considered substantial; Landis and Koch, 1977). Any disagreements between the coders were resolved through discussion. See Table 1 for category explanations, examples, and kappa values.

Results

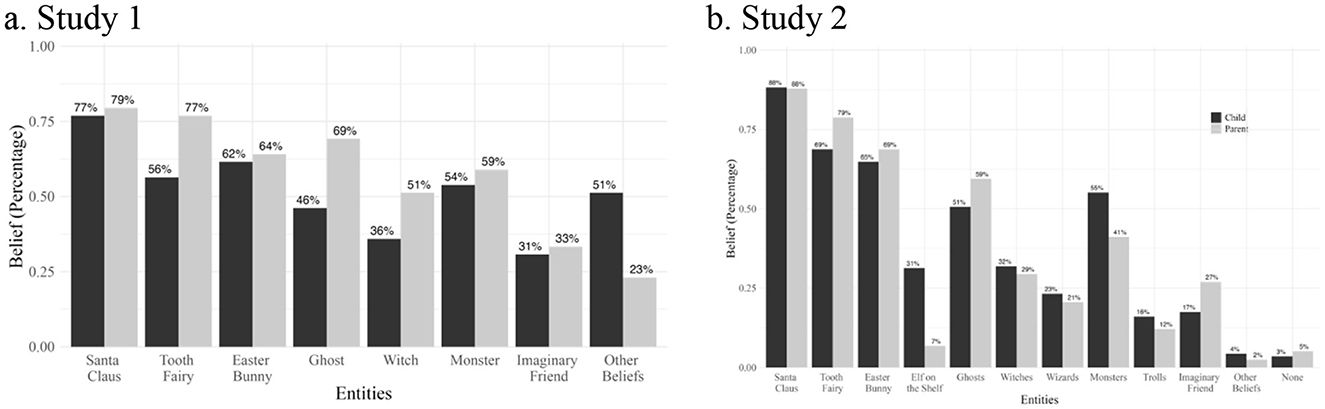

On average, parents reported that their child currently believed in about four fantasy figures (MChild = 4.13, SD = 2.32), and that they themselves had believed in about five during their childhood (MParent = 4.56; SD = 1.93). Most children and parents reported to believe in Santa Claus, the Tooth Fairy, and the Easter Bunny, with Santa Claus being the most believed figure (child: 77%, n = 30; parent: 79%, n = 31; see Figure 1a). Interestingly, more than half of parents reported that their child (54%, n = 21), as well as they themselves (59%, n = 23), believed in monsters. Parents were more likely to report having believed in ghosts and witches during their own childhood than to report such beliefs for their child, although these differences were not significant after correcting for multiple comparisons (all ps > 0.05). Belief in imaginary friends received the lowest ratings for both children and parents. About half of parents also reported that their child held other beliefs, which were mostly related to media characters (e.g., Disney princesses, superheroes).

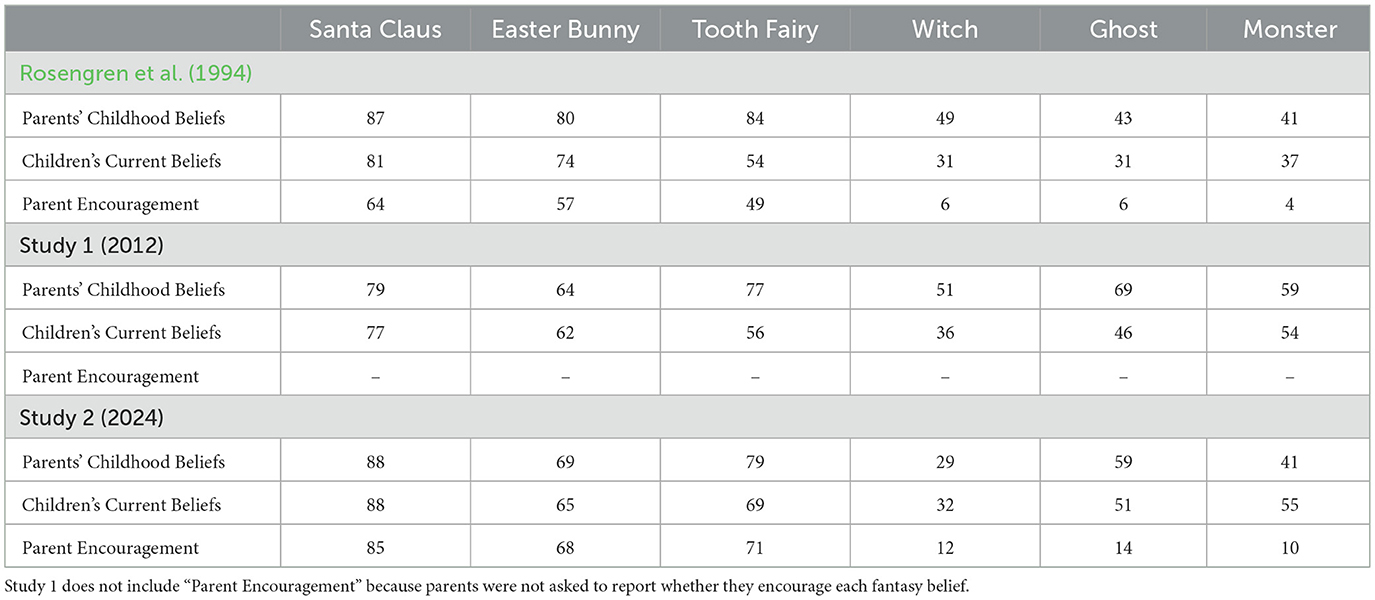

Figure 1. Percentage of children's and parents' fantasy beliefs across two studies. Percentages reflect children's current beliefs and parents' childhood beliefs for Study 1 (a) and Study 2 (b). Elf on the Shelf, Wizard, and Troll were added in Study 2.

Next, we examined parents' encouragement of fantasy beliefs. Most parents (82%, n = 32) reported encouraging fantasy beliefs, primarily for figures that are culturally endorsed (i.e., Santa Claus, the Tooth Fairy, the Easter Bunny; n = 27). No parent exclusively encouraged belief in culturally non-endorsed figures (i.e., ghosts, monsters, witches), but seven parents encouraged belief for both non-endorsed and endorsed figures. The top three reasons for encouraging fantasy beliefs were that they were viewed as a normal part of childhood (56%, n = 18), bring excitement (47%, n = 15), and that they were part of family tradition (31%, n = 10; see Figure 2). When asked whether they believe fantasy beliefs have any benefits, most parents (82%, n = 32) indicated that they do, citing advantages such as promoting excitement, imagination, creativity, and sharing cultural and family traditions. In contrast, five parents mentioned potential benefits of discouraging fantasy beliefs, which included maintaining trust between parent and child (whether for personal or religious reasons), limiting imagination (e.g., fantasy reality distinction), and protecting children from negative emotions (e.g., fear) associated with some beliefs.

Figure 2. Reasons parents encourage and discourage children's fantasy beliefs. The Y-axis represents the number of parents who provided reasons for encouraging (left) and discouraging (right) fantasy beliefs in children.

When examining parents' discouragement, about half (59%, n = 23) reported discouraging belief in certain figures, mostly culturally non-endorsed figures (74%, n = 17). However, three parents reported discouraging belief in culturally endorsed figures. The most common reason for discouraging fantasy beliefs was to protect their child from harm (74%, n = 17; see Figure 2). Among those who discouraged belief in endorsed figures, reasons included conflicts with religious belief (e.g., “we believe Jesus is everything for the season, for Christmas”) or a desire to avoid lying to their child (e.g., “we don't want to lie to her […] tell her that Santa is real, and then later tell her that no, Santa's not real”).

Even though most parents encouraged fantasy beliefs, their views on how children should come to learn the truth varied. About half of the parents (46%, n = 18) reported that children should discover the truth on their own, while 39% (n = 15) reported that parents should be the ones who help children to discover the truth. A smaller group (13%, n = 5) reported that both the parent and child should work together to uncover the truth. When asked whether they planned to stop their encouragement at some point, about half of parents (46%, n = 18) said they would. However, only ten parents provided a specific age at which they planned to stop (MAge = 7.3 years, range = 5–10). This age was similar to the age at which parents reported ending their own fantasy beliefs (MAge = 7.5 years, range = 4–13). Among those who said they would eventually stop, five parents noted that their child would likely figure it out before they needed to intervene, and three said it would depend on when their child stopped believing on their own.

Among the parents who remembered how they felt after discovering the truth about their childhood fantasy beliefs (n = 27), just over half (56%, n = 15) reported feeling fine upon learning the truth. About a third (33%; n = 9) said they felt sad or disappointed, while three parents reported feeling mad or annoyed at their own parents. When asked to rate the impact of these childhood beliefs on their adult life, parents generally reported positive influence (M = 3.92, SD = 0.84). Although parents rated religion as important in their lives (M = 5.13, SD = 1.69), most (69%) believed that childhood fantasy beliefs have either a positive (n = 15) or no impact (n = 12) on children's later religious belief. Eight parents, however, reported that such beliefs could negatively influence the development of religious belief.

Discussion

Consistent with prior research (Rosengren et al., 1994; Rosengren and Hickling, 1994), the present findings indicate that most parents and children believed in culturally endorsed fantasy figures such as Santa Claus. Parents generally supported these beliefs while discouraging belief in culturally non-endorsed figures. Encouragement was often motivated by a desire to foster excitement, maintain a sense of childhood magic, and support cultural connections. In contrast, discouragement was primarily driven by efforts to protect children from fear or negative emotional experiences.

Religious values also influenced parental behavior. Some parents discouraged belief in culturally endorsed figures (e.g., Santa Claus) to preserve the spiritual meaning of religious holidays, while others selectively supported such beliefs to help their children fit in socially. Interestingly, about half of the parents reported that they and their children believed in culturally non-endorsed figures like monsters or ghosts, suggesting that children sometimes believe in figures that are more likely to be discouraged by parents within the culture. This implies that factors other than parental encouragement, such as children's media, may contribute to children's beliefs. Anecdotal evidence for this comes from a parent who reported encouraging monsters because their child enjoys characters from Sesame Street.

These results highlight the nuanced ways in which cultural norms and personal values may shape parental support for fantasy beliefs. Additionally, most parents reported little distress upon learning the truth about fantasy figures in their own childhoods, consistent with findings by Mills et al. (2024). However, many viewed these beliefs as having a positive developmental impact. While some parents believed that early fantasy experiences could support later belief in unseen religious entities, others saw no connection. Overall, the findings suggest that parents generally view fantasy beliefs as beneficial, and their decisions to support such beliefs may be shaped by a complex interplay of cultural and individual factors (see Supplementary file S1 for details of a replication study that produced similar findings). However, it is important to note that these findings are based on a small, homogeneous sample. Since cultural and socioeconomic factors can shape how parents perceive and support children's fantasy beliefs, the results may not generalize to families from more diverse backgrounds. Future research should explore how parental support varies across cultural contexts.

Study 2

The two main aims of Study 2 were: (1) to investigate how individual factors relate to parental support for childhood fantasy beliefs, and (2) to explore whether parental encouragement of fantasy beliefs has changed over time. First, we wanted to examine how individual factors were related to parental support for childhood fantasy beliefs. Specifically, although prior research, including Study 1, has shown that various factors could influence parental support, there has not been a systematic analysis of how individual factors affect both encouragement and discouragement of children's fantasy beliefs. So, we examined whether parents' encouragement or discouragement of such beliefs could be predicted by child's age and parents' views on fantasy beliefs. Specifically, we hypothesized that parental support for culturally endorsed figures would increase with child age, consistent with prior findings (Goldstein and Woolley, 2016). We also expected greater support from parents who had more childhood fantasy beliefs and who viewed fantasy beliefs as having a positive influence on adulthood. However, we did not expect parental support to be related to negative reactions (e.g., feeling angry or betrayed after discovering the truth), as these tend to be short-lived (Mills et al., 2024). Although a few parents in Study 1 reported discouraging fantasy beliefs for religious reasons, we did not expect parents' religiosity to predict parental support, given prior research suggesting no relation when parents are not Fundamental Christians (Braswell et al., 2012). However, we did expect lower support from parents who believed fantasy beliefs negatively impact children's religious development.

For the second aim, we examined whether there was a change in parental support over time. As discussed in Study 1, cultural context may influence both individual beliefs and parental encouragement. Since the 2000s, culturally non-endorsed figures have increasingly been portrayed as lovable characters in children's media (e.g., Monsters, Inc.), potentially increasing both parents' encouragement and their report of children's beliefs compared to earlier studies from the 1990s (Rosengren et al., 1994; Rosengren and Hickling, 1994). Conversely, levels of encouragement and belief may have declined over the 30 years, consistent with the secularization hypothesis. This hypothesis proposes that technological advances and an increase in knowledge and education at the sociocultural level shift reliance away from religious and magical beliefs toward scientific reasoning (Hernández and Rosengren, 2024). Today's children have earlier and greater exposure to digital technology (often before age 2; Mann et al., 2025), possibly providing them with more knowledge and experience to negotiate the boundaries between reality and fantasy at younger ages. If this is true, parents today may be more reluctant to encourage fantasy beliefs and may report lower levels of belief in their children compared to parents in earlier decades. To explore this, we compared data from Studies 1 and 2 with findings from the 1990s.

Methods

Participants

A total of 501 parents were recruited from Prolific. All parents were over the age of 18, lived in the United States, and had at least one child between the ages of 3–8 years. A priori power analysis was conducted using SIMR package (Green and Macleod, 2016) in R. This package allows for simulation-based power analysis for generalized linear mixed-effects models. We used the data collected in our replication study to simulate a dataset with 400 and 500 parents. The analysis indicated that a target sample of 400 would provide 82% power and 500 would provide 88% power when fitted to the generalized linear mixed-effects model we used in the analysis. So, we recruited 500 parents with the expectation that some of the parents would be removed for completing the survey unconscientiously as was observed in our replication study.

Fifteen parents were excluded for reporting on a child outside the target age range. All parents passed the attention checks. The final sample included 486 parents (MParent = 34.47, SD = 5.81; 316 mothers; MChild = 4.74, SD = 1.52). The survey was conducted between September 18 and 19, 2024 and took about 13 min to complete. Parents were compensated $4 for their participation.

Most of parents (58%, n = 283; 44 did not report their race/ethnicity) identified as Caucasian/White and reported being affiliated with Christianity (55%, n = 265). A majority also reported having earned a bachelor's degree or higher (58%, n = 283). See Supplementary file S1 for detailed information. Parents' religiosity was measured using the Duke University Religion Index (Koenig and Büssing, 2010). On average, parents were unsure whether their religion motivates their life (M = 3.04, SD = 1.42) and reported attending religious service a few times per year (M = 2.68, SD = 1.68). As a proxy for socioeconomic status, parents reported their perceived social status (Adler et al., 2000). The mean score was 5.40 (SD = 1.70) where 1 represents individuals who are worst off and 10 represents those who are best off.

Procedure and measures

Parents completed a 69-question survey administered via the Qualtrics platform. The survey included five types of questions, adapted from Study 1. Additionally, five attention check questions were included to filter out parents who were not completing the survey conscientiously. Parents were first asked about their child's current beliefs, their encouragement and discouragement for each belief, and how they think their child will react when they discover the truth. Then, parents were asked about their overall childhood beliefs and how they reacted when they discovered the truth about their childhood beliefs. The survey can be found at: https://osf.io/kymex/?view_only=9cdc1bf52ef642559b74bbc453a1dd9c

Belief in fantasy figures

Parents were asked “Does your child currently believe in any of the following fantasy beliefs?” and were asked to select all beliefs that their child has from the following list: Santa Claus, Tooth fairy, Easter Bunny, Ghosts, Monsters, Witches, Wizards, Trolls, Elf on the Shelf, Imaginary Friend(s), and Other. For Other choice, parents were asked to specify what other belief(s) their child has. Similarly, parents were asked for their own childhood beliefs: “Did you believe in any of these fantasy beliefs when you were a child?,” and they were given the same choice options as the child's fantasy belief question.

Encouragement and discouragement of fantasy beliefs

Parents were asked “Do you encourage your child to believe in any of the following fantasy figures?” and responded with Yes or No for each figure listed in Belief in Fantasy Figures section. For each figure they encouraged, parents were then asked to indicate their reason: “Why do you encourage belief in […]?” The response options included: “Normal part of childhood,” “For fun/Interest,” “It is a cultural practice or tradition,” “Family values or tradition,” “To protect the child,” “Prosocial behavior,” and “Other.” Parents could select multiple reasons.

A similar format was used to assess discouragement of belief in fantasy figures. Parents who indicated discouragement were asked to select their reasons from the following options: “My child is too old/young for them,” “They promote things that are not real,” “They promote bribery for good behavior,” “It's lying,” “It's harmful,” “Due to religious reasons,” “It may reduce my child's religious faith,” and “Other.” Multiple responses could be selected. For analysis purposes, “Due to religious reasons” and “It may reduce my child's religious faith” were combined into a single Religion category as both relate to religious concerns.

Impact of childhood fantasy beliefs

Parents were asked to report how they felt when they found out the truth about their childhood fantasy belief(s), as well as how they think their child would feel in the same situation: “How did you react when you found out the truth?” and “How do you think your child will react when they discover the truth about their fantasy beliefs?.” They were provided with the following options: “Feel angry,” “Feel sad or disappointed,” “Feel lied to or betrayed,” “Feel relieved or happy,” “Feel surprised,” “Feel proud for figuring out,” “Feel indifferent,” and “Other,” with parents allowed to select multiple options and specify their reaction for “Other.” Parents were also asked how long their reaction lasted (1= A day, 5= Over a year) and whether their childhood fantasy beliefs affected their relationship with their parents as a “Yes” or “No” question. Additionally, parents rated how they believed their childhood fantasy beliefs impacted their adult life using a 5-point-Likert scale (1 = Very Negatively, 5= Very Positively).

Religiosity

Parents' religiosity was measured using the Duke University Religion Index (Koenig and Büssing, 2010), which included two types of questions. The first type assessed religious behavior through two questions: “How often do you attend church or other religious meetings?” (1 = Never, 6 = More than once per week) and “How often do you spend time in private religious activities, such as prayer, meditation or Bible study?” (1 = Rarely or never, 6 = More than once a day). The average of these two questions was used as the religious behavior score. The second type assessed religious motivation through three statements rated on a 5-point-Likert scale (1 = Definitely not true, 5 = Definitely true for me): “In my life, I experience the presence of the Divine (i.e., God),” “My religious beliefs are what really lie behind my whole approach to life,” and “I try hard to carry my religion over into all other dealings in life.” The average of the three statements was used as the religious motivation score. Finally, parents were asked to report how fantasy beliefs might impact children's developing religious belief (“How do you feel fantasy beliefs will affect a child in terms of developing religious beliefs?”) in a 5-point-Likert scale (1 = Very negatively, 5 = Very positively).

Demographic information

Parents reported their child's gender, age, and race/ethnicity, as well as their own gender, race/ethnicity, education level, and perceived SES.

Analytical approach

We examined descriptive statistics of parents' reports on their own and their child's fantasy beliefs, parents' reasons for encouragements and discouragements, parents' views of fantasy beliefs (i.e., impact on adulthood and children's development of religious beliefs), and parents' and children's reactions to discovering the truth. Next, we explored how child (i.e., age) and parental (i.e., childhood fantasy beliefs, impact of beliefs on adulthood and children's development of religious belief, negative reactions, religiosity) factors related to parents' support for fantasy beliefs. Generalized linear mixed models were used in R to predict parents' encouragements and discouragements based on the individual factors. All factors were mean centered, and by-participant random intercept was included to account for multiple responses from the same parent. Additionally, a variable for type of figure (culturally endorsed figures coded as 1 and non-endorsed figures coded as 0) was included and allowed to interact with child age to test whether the relation between parent's encouragement or discouragement and child age was moderated by the type of fantasy figure. Lastly, we investigated whether children's and parents' beliefs, as well as parents' encouragement, changed over time. We conducted a test of proportions to determine whether the differences in beliefs and encouragements between the current study and that of the 1990s were statistically significant. Data and analysis script can be found at: https://osf.io/kymex/?view_only=9cdc1bf52ef642559b74bbc453a1dd9c

Results

On average, parents reported that both their children and they themselves in childhood held about four fantasy beliefs (MChild = 4.34, SD = 2.27; MParent = 4.07, SD = 2.15). Consistent with Study 1, both groups were most likely to believe in culturally endorsed figures: Santa Claus [nParent = 427 (88%), nChild = 429 (88%)], the Tooth Fairy [nParent = 383 (79%), nChild = 334 (69%)], and the Easter Bunny [nParent = 334 (69%), nChild = 315 (65%); see Figure 1b]. Regarding culturally non-endorsed figures, some differences emerged between parents and children. Although parents reported believing in ghosts during their childhood more than their children currently do [nParent = 289 (59%), nChild = 246 (51%); χ2 (1, N = 972) = 7.69, p = 0.017], more parents reported that their children believed in witches and monsters than they did during childhood, a pattern that differed from Study 1. However, only the difference for monster reached statistical significance [nParent = 200 (41%), nChild = 268 (55%); χ2 (1, N = 972) = 19.06, p < 0.001]. All p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction.

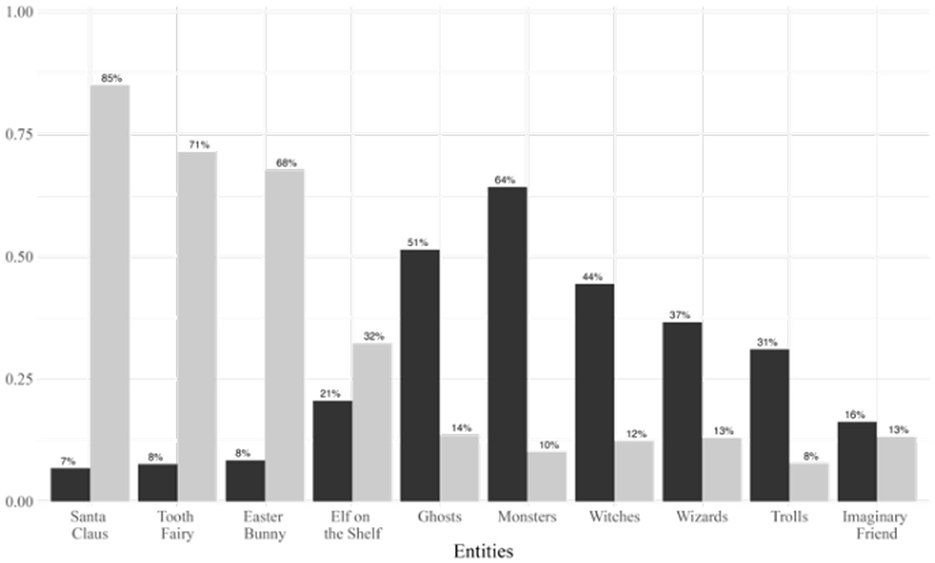

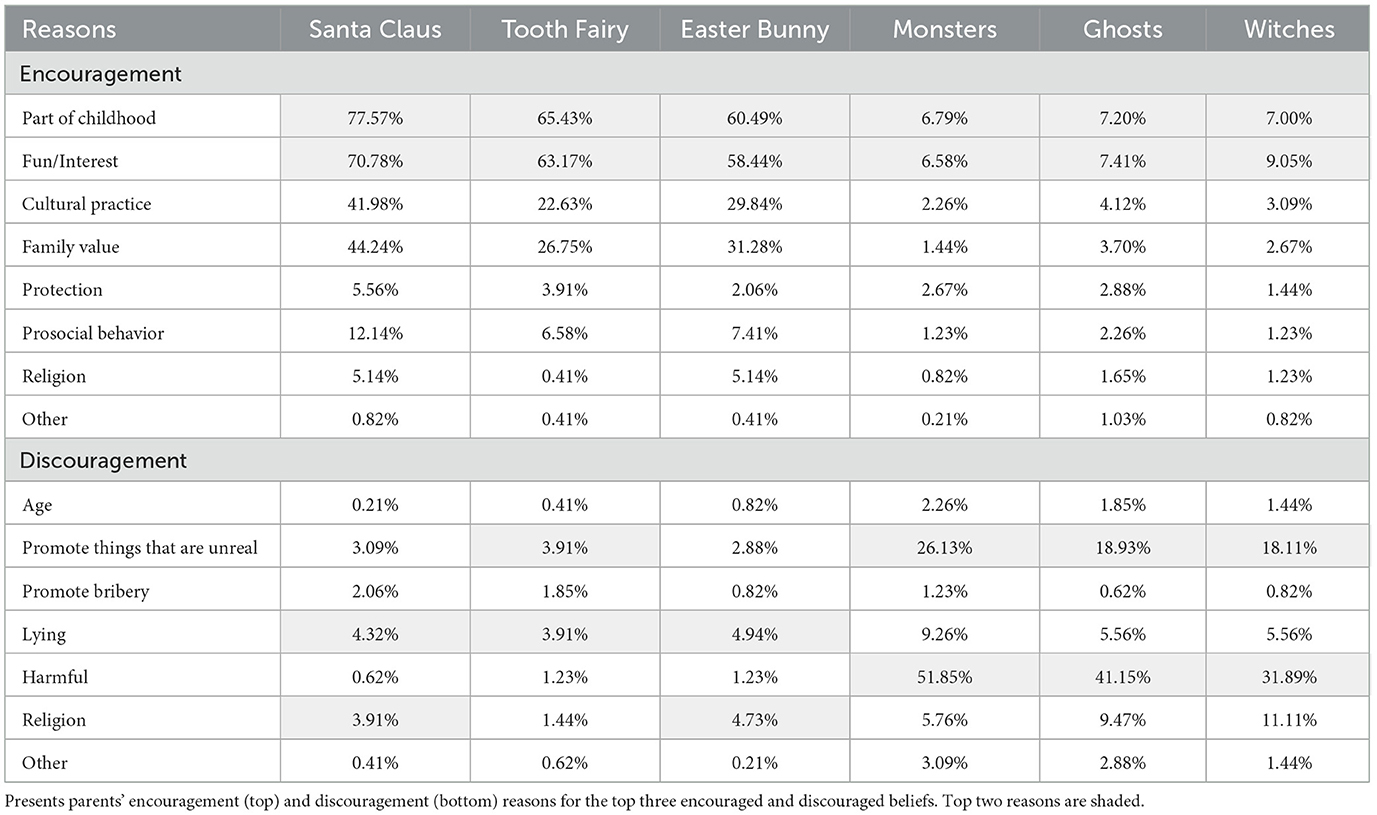

Parents encouraged and discouraged three beliefs on average (MEncourage = 3.26, SD = 2.01; MDiscourage = 2.87, SD = 2.67; see Figure 3). Consistent with Study 1, most parents supported culturally endorsed beliefs while discouraging non-endorsed ones. The top three encouraged beliefs were Santa Claus (85%, n = 413), the Tooth fairy (71%, n = 347), and the Easter Bunny (68%, n = 329). The top three discouraged beliefs were monsters (64%, n = 312), ghosts (51%, n = 250), and witches (44%, n = 216). The most common reasons parents gave for encouragement were that these beliefs were a normal part of childhood (83%, n = 402) and that they create fun/interest (82%, n = 397). About half of the parents also reported encouraging beliefs to maintain cultural (50%, n = 241) and family (52%, n = 251) traditions. This pattern held true across the different types of fantasy beliefs (see Table 2 for details).

When examining the reasons for discouragement, the two most commonly reported were to protect the child (61%, n = 297) and to clarify the distinction between fantasy and reality (37%, n = 181). Only a few parents reported discouraging beliefs because they viewed encouragement of fantasy beliefs as a form of lying (17%, n = 84) or for religious reasons (19%, n = 90). Parents mainly indicated protection from negative emotions and clarifying the fantasy/reality distinction as reasons for discouraging culturally non-endorsed beliefs. In contrast, lying and religious reasons were more often reported for discouraging culturally endorsed beliefs, specifically Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny (see Table 2). Overall, parents' reasoning for encouraging beliefs were consistent with those in Study1, suggesting that parents promote childhood fantasy beliefs primarily for the wellbeing of the child.

Similar to Study 1, parents did not have a negative view of childhood fantasy beliefs. They reported that their own childhood fantasy beliefs had neither a positive nor negative impact on their adult lives (M = 3.36, SD = 0.77). Likewise, parents generally believed that fantasy beliefs have no real impact on children's development of religious beliefs (M = 3.07, SD = 0.75). Additionally, parents' religiosity, specifically their religious motivation, was not related to their view on whether fantasy beliefs impact children's religious development [rs(484) = −0.06, p = 0.213].

When parents recalled their reaction to discovering the truth about their childhood fantasy beliefs, half (50%, n = 203) of those who remembered (n = 405) reported at least one negative emotion (i.e., felt angry, felt sad or disappointed, felt lied to or betrayed). Of those, 150 reported only negative reactions. In contrast, about a quarter (n = 103) recalled at least one positive reaction (i.e., felt relieved or happy, felt proud for figuring out), with roughly half of these parents (n =56) experiencing only positive reactions. Additionally, 92 parents (19%) reported feeling only indifferent, and 35 reported feeling only surprised without specifying whether the surprise was positive or negative. Although many parents experienced negative emotions, most (78%, n = 260) of those who remembered how long their reaction lasted (n = 335) reported their feelings only lasted less than a few days. Importantly, 90% (n = 436) reported that childhood fantasy beliefs did not impact their relationship with their parents.

When asked how parents thought their child would react, 57% (n = 277) anticipated at least one negative response. Of those, about half (n = 145) believed their child would feel only negative emotions. Around 40% (n = 195) predicted at least one positive reaction from their child, with 66 expecting only positive emotions. Additionally, 44 parents (9%) expected their child to feel only indifferent, and 40 predicted only surprise. When comparing parents' own reactions to their expectations for their child, parents were significantly more likely to believe that their child would experience positive emotions than they themselves did [χ2(1, N = 891) = 21.42, p < 0.001], though differences in negative reactions were not statistically significant [χ2(1, N = 891) = 4.20, p = 0.081]. The p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction.

Relation between parental support of fantasy beliefs and individual factors

When examining parents' encouragement of fantasy beliefs in relation to individual factors, the child's age did not significantly predict parents' encouragement [OR = 0.89, χ2 (1, N = 486) = 3.51, p = 0.061]. However, there was a significant interaction between age and type of figure [OR = 1.29, χ2(1, N = 486) = 15.44, p < 0.001]. Parents were generally more likely to encourage culturally endorsed figures than non-endorsed ones [OR = 32.13, χ2(1, N = 486) = 1,060.12, p < 0.001], and this tendency was stronger for older children. Parental factors also predicted their encouragement. Parents who held more childhood fantasy beliefs themselves [OR = 1.18, χ2(1, N = 486) = 24.26, p < 0.001] and perceived childhood fantasy beliefs to have a positive impact on their adult life [OR = 1.78, χ2(1, N = 486) = 36.22, p < 0.001] were more likely to encourage fantasy beliefs. Additionally, parents who viewed fantasy beliefs to have a positive impact on children's developing religious belief were more likely to encourage fantasy beliefs [OR = 1.50, χ2(1, N = 486) = 17.80, p < 0.001]. However, parent's religiosity and negative reaction did not significantly predict parents' encouragement (ps > 0.05).

For discouragement, the child's age did not significantly predict parents' discouragement [OR = 1.06, χ2(1, N = 486) = 0.64, p = 0.422], suggesting that parents are equally likely to discourage fantasy beliefs regardless of age. However, parents were more likely to discourage fantasy beliefs if they rated themselves as more religious [OR = 1.20, χ2(1, N = 486) = 6.06, p = 0.014) or if they perceived fantasy beliefs as having a negative impact on children's development of religious belief [OR = 0.50, χ2(1, N = 486) = 22.38, p < 0.001]. Other factors did not significantly predict parents' discouragements (all ps > 0.05).

Change in beliefs and encouragement over 30-year time period

Next, we examined whether there was a change in the beliefs and encouragement over the 30-year period. We compared the results of Study 1 and 2, and prior studies Rosengren et al., (1994) that reported child's beliefs, parent's childhood beliefs, and parents' encouragement (see Table 3). Parents' report of their child's and their own beliefs of culturally endorsed figures remained consistent across this time period. Most parents reported that their child and they, themselves, believed in these figures. The reported beliefs of non-endorsed beliefs also remained somewhat consistent over time. Parents were less likely to report that their child or they, themselves, had beliefs related to culturally non-endorsed beliefs compared to culturally endorsed beliefs. However, parents' report of their child's beliefs of ghosts and monsters significantly increased over time [ghost: χ2(1, N = 556) = 9.02, p = 0.019; monster: χ2(1, N = 556) = 7.96, p = 0.033]. Also, their report of their belief in witches decreased [χ2(1, N = 556) = 10.34, p = 0.009]. Parents' reports of encouragement for both types of beliefs increased slightly over the 30-year period, but their encouragement for Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy significantly increased [Santa: χ2(1, N = 556) = 18.05, p < 0.001; Tooth Fairy: χ2(1, N = 556) = 14.78, p < 0.001]. All p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction.

Table 3. Percentage of reported children's and parents' childhood fantasy beliefs and parent's encouragement of fantasy beliefs across time.

General discussion

Parental reports of both their own and their children's fantasy beliefs have remained relatively consistent over the past 30 years. Parents and their children (as reported by parents) were more likely to believe in culturally endorsed figures than in non-endorsed ones. While children's belief in culturally endorsed figures has remained stable over time, parental encouragement for beliefs in Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy has increased. The reason for this increase is unclear, but one possibility is that parents are making greater efforts to preserve the “magic” of childhood (Clark, 1995; Goldstein and Woolley, 2016) at a time when children have easier access to information that could challenge these beliefs. Compared to the 1990s, today's children can effortlessly access information through the internet and even via voice-activated conversational agents like Alexa or Siri. As a result, some parents may worry that their child could discover the truth about these figures, even though children's belief in them has remained stable. This concern may motivate parents to encourage these beliefs more actively than in the past. Another possibility is that parents' own internet use, particularly social media, may play a role. Seeing posts from other parents who actively encourage fantasy beliefs may create social or cultural pressure to do the same. Therefore, future research should examine how both in-home technology use and parents' engagement with social media influence their encouragement of culturally endorsed beliefs in children.

Interestingly, an increase in parental reports of children's belief in ghosts and monsters was also observed, despite relatively stable levels of parental encouragement for these figures. In Study 2, parents were more likely to report that their child believes in monsters than they themselves did during childhood. One possible explanation for this trend is the prevalence of fantastical content in children's media in recent years (Goldstein and Alperson, 2020; Taggart et al., 2019). For example, Goldstein and Alperson (2020) found that media for children aged 3–6 often features magical creatures portrayed in a positive light, including friendly depictions of monsters and ghosts. Given the unchanged parental encouragement for these figures, media may have played a significant role in shaping children's beliefs. Taken together, these findings suggest that media, in addition to parental support, contributes to the development of children's fantasy beliefs which contradict the secularization hypothesis. Further research is needed to explore how media depictions influence both children's and parents' attitudes toward culturally non-endorsed beliefs.

Parental support for childhood fantasy beliefs has also remained relatively consistent over the past 30 years, with parents generally encouraging culturally endorsed beliefs while discouraging those that are not. Their reasoning for this support remained stable over the 12-year span between Study 1 and Study 2. Parents typically encouraged fantasy beliefs to foster excitement, support normal childhood, and promote a shared cultural experience. At the same time, they discouraged certain beliefs, particularly culturally non-endorsed ones, to protect their child from emotional harm (e.g., fear, anxiety) and to help them distinguish between fantasy and reality. These findings suggest that parents adopt different strategies depending on the type of fantasy belief, despite all such beliefs being unrealistic. However, some parents reported encouraging belief in non-endorsed figures as well, viewing them as a meaningful part of childhood that brings excitement. Conversely, some parents discouraged belief in culturally endorsed figures, citing concerns about lying or conflicts with religious values.

Despite actively supporting their children's fantasy beliefs, parents did not always view it as their responsibility to disclose the truth about fantasy beliefs as shown in Study 1. This suggests that parents may think that their child should gradually discover the truth on their own. A gradual process of discovering the truth may help children to cope more effectively when they realize these beliefs are not real. Supporting this idea, Mills et al. (2024) found that adults who discovered the truth about their childhood beliefs abruptly or through their parents were more likely to experience negative reactions such as betrayal and anger. These findings suggest that allowing children to take an active role in uncovering the truth about their fantasy beliefs may help mitigate negative reactions, and most parents appear to favor this approach.

Parents generally did not hold negative views of childhood fantasy beliefs. Most reported that their own childhood beliefs had no negative impact on their adult lives and did not view fantasy beliefs as harmful to the development of religious belief in children. About half recalled experiencing a negative reaction upon discovering the truth about their childhood beliefs, and a similar proportion of parents expected their own child to have a negative reaction as well. While negative emotions were common, they were typically reported as brief, consistent with findings with Mills et al. (2024). Parents also indicated that learning the truth did not harm their relationship with their own parent. Interestingly, however, more parents anticipated that their child would react positively than they recalled doing so themselves. This belief may help to explain the increase in parental encouragement for culturally endorsed beliefs over the past 30 years. If parents expect their children to respond more positively than they did to learning the truth, they may feel more comfortable actively encouraging such beliefs.

When examining the relation between individual factors and parents' decisions to support fantasy beliefs, these factors played different roles in parents' encouragement and discouragement. Parents were more likely to encourage fantasy beliefs, particularly culturally endorsed ones, for older children. This increased support with age may reflect the fact that some figures (i.e., the Tooth Fairy) are closely tied to developmental stage, as well as parents' desire to reinforce these beliefs as their child grows (Goldstein and Woolley, 2016). Since older children are more likely to question surprising claims (Hermansen et al., 2021; Ronfard et al., 2021) and to doubt the reality status of fantasy figures (Goldstein and Woolley, 2016), parents may actively promote such beliefs to prolong the “magic” of childhood (Clark, 1995; Goldstein and Woolley, 2016). This increased encouragement of culturally endorsed beliefs for older children may also explain why they tend to believe in more fantasy figures than younger children (Sharon and Woolley, 2004).

Another factor that was related to parental support for fantasy belief was their views of childhood fantasy beliefs. Parents who had more childhood beliefs and who viewed these beliefs as having a positive impact on adulthood were more likely to encourage their children's fantasy beliefs. Contrary to critics of childhood fantasy beliefs, parents' negative experiences with fantasy beliefs (e.g., being angry or feeling betrayed when discovering the truth) were not related to parental support. This aligns with prior research showing that negative reactions are short-lived (Mills et al., 2024), and that most children and adults report they intend to encourage fantasy belief, specifically about Santa Claus, when they become parents (Anderson and Prentice, 1994; Mills et al., 2024). The current study also found that parents were more likely to predict their child will have a positive reaction upon discovering the truth than they themselves remembered having. This suggests that parents may hold optimistic expectations that their child will view their fantasy belief experiences positively. So, parents tend to believe that the benefits of childhood fantasy beliefs outweigh the negative emotions associated with discovering the truth. These results also imply that examining parents' own childhood fantasy experiences may be helpful for understanding children's fantastical and imaginary thinking, as parents' positive experiences may encourage children to explore a broader fantasy realm through fantasy beliefs.

Lastly, parents' religiosity played a role in their decisions to support fantasy beliefs. While religiosity was not related to parents' encouragement of fantasy beliefs, parents who perceived themselves as religious were more likely to discourage them. Additionally, parents who believed that fantasy beliefs negatively influence children's religious development tended to discourage such beliefs. These findings align with prior research with Fundamental Christian parents (Clark, 1995). However, the current study also found that some parents encouraged fantasy beliefs when they perceived them to have a positive impact on children's development of religious belief. Overall, these results suggest that religious parents are generally more likely to discourage fantasy beliefs, but some encourage them if they see potential benefits for their child's religious growth.

In sum, parents viewed fantasy beliefs as a normal part of childhood and promoted them for their perceived benefits to the child. However, the current findings suggest that parents navigate supporting these beliefs in complex and adaptive ways, balancing cultural norms, personal experiences, children's developmental considerations, and religious values, to determine which beliefs they encourage or discourage in their children's imaginative lives.

Limitations

One limitation of the studies is the reliance on parental reports, which may be subject to bias in parents' report of children's fantasy beliefs. However, because the primary aim of the current studies was to understand why parents support these beliefs, parental self-report was considered an appropriate method. Furthermore, prior research that aimed at understanding parental support for fantasy beliefs has also used similar methods (Goldstein and Woolley, 2016). Further, given that similar results were obtained over multiple studies, some occurring 30 years prior to the current study, the results appear to be highly reliable.

Another limitation concerns the generalizability of the findings. Parents who participated were mostly White Christians who were well-educated and all lived in the United States. Since cultural and religious backgrounds can shape parents' decisions toward fantasy beliefs, the current findings may not be generalizable to all parents in the United States, particularly those from non-Christian or minority cultural backgrounds, and to those parents who live in other cultures. That said, given that about 62% of the U.S. population identifies as White (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020) and 63% as Christians (Pew Research Center, 2022), the current findings offer a general understanding of how a majority of parents in the United States perceive fantasy beliefs and how individual factors impact their decision. Future research with more diverse samples is needed to better understand how cultural and religious differences influence parental reasoning and decision regarding fantasy belief support.

Conclusion

The studies demonstrated that parents generally viewed childhood fantasy beliefs as meaningful and beneficial to child development, supporting them for their role in fostering enjoyment and social belonging. However, parents also regulated these beliefs by encouraging culturally endorsed figures while discouraging non-endorsed ones. Still, children's fantasy beliefs were not solely determined by parental support, as some children held beliefs discouraged by parents. Parental support was related to individual factors such as the child's age, parents' own childhood experiences, and religious values, suggesting that children's engagement with fantasy is shaped by parental attitudes rooted in cultural norms, personal beliefs, and religious values. The findings imply that children's window into the fantasy realm is partly shaped by how parents interpret their child's cultural context and wellbeing, as well as their own views of fantasy. Differences in children's fantasy beliefs, and potentially in their broader imaginative thinking, should therefore be examined in light of the extent to which parents support fantasy exploration. Finally, childhood fantasy beliefs have remained a stable part of U.S. childhood culture over the past 30 years, though the growing influence of media and technology may be gradually shifting the source of these beliefs from parental to external influences and also affecting degree to which parents encourage fantasy engagement.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://osf.io/kymex/?view_only=9cdc1bf52ef642559b74bbc453a1dd9c.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Northwestern University and the University of Rochester. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Participants in Study 1 provided written informed consent. For Study 2, the institutional review board waived the requirement for written informed consent because it was an online survey. Participants were informed that continuing with the survey indicated their consent, and all relevant study information was provided in an information sheet at the beginning of the survey. The study reported in the Supplementary material was approved by the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and the requirement for written informed consent was also waived because it was an online survey.

Author contributions

SY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. MJ: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Data curation. KR: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fdpys.2025.1703073/full#supplementary-material

References

Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., and Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychol. 19, 586–592. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.6.586

Anderson, C. J., and Prentice, N. M. (1994). Encounter with reality: children's reactions on discovering the Santa Claus myth. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 25, 67–84. doi: 10.1007/BF02253287

Boerger, E. A. (2011). “In fairy tales fairies can disappear”: children's reasoning about the characteristics of humans and fantasy figures. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 29, 635–655. doi: 10.1348/026151010X528298

Boerger, E. A., Tullos, A., and Woolley, J. D. (2009). Return of the candy witch: individual differences in acceptance and stability of belief in a novel fantastical being. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 27, 953–970. doi: 10.1348/026151008X398557

Braswell, G. S., Rosengren, K. S., and Berenbaum, H. (2012). Gravity, god and ghosts? Parents' beliefs in science, religion, and the paranormal and the encouragement of beliefs in their children. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 36, 99–106. doi: 10.1177/0165025411424088

Canfield, C. F., and Ganea, P. A. (2014). “You could call it magic”: what parents and siblings tell preschoolers about unobservable entities. J. Cogn. Dev. 15, 269–286. doi: 10.1080/15248372.2013.777841

Clark, C. D. (1995). Flights of Fancy, Leaps of faith: Children's Myths in contemporary America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Corriveau, K. H., and Harris, P. L. (2009). Preschoolers continue to trust a more accurate informant 1 week after exposure to accuracy information. Dev. Sci. 12, 188–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00763.x

Goldstein, T. R., and Alperson, K. (2020). Dancing bears and talking toasters: a content analysis of supernatural elements in children's media. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 9, 214–223. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000222

Goldstein, T. R., and Woolley, J. (2016). Ho! Ho! Who? Parent promotion of belief in and live encounters with Santa Claus. Cogn. Dev. 39, 113–127. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2016.04.002

Green, P., and Macleod, C. J. (2016). SIMR: an R package for power analysis of generalized linear mixed models by simulation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 493–498. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12504

Harris, P. L., and Koenig, M. A. (2006). Trust in testimony: how children learn about science and religion. Child Dev. 77, 505–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00886.x

Hays, C., and Carver, L. J. (2014). Follow the liar: the effects of adult lies on children's honesty. Dev. Sci. 17, 977–983. doi: 10.1111/desc.12171

Hermansen, T. K., Ronfard, S., Harris, P. L., Pons, F., and Zambrana, I. M. (2021). Young children update their trust in an informant's claim when experience tells them otherwise. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 205:105063. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2020.105063

Hernández, G. T., and Rosengren, K. S. (2024). “Change in religiosity,” in The Routledge International Handbook of Changes in Human Perceptions and Behaviors, eds. K. Taku and T. K. Shackelford (New York, NY: Routledge), 472–488. doi: 10.4324/9781003316602-34

Ho, V., Stonehouse, E., and Friedman, O. (2024). When children choose fantastical events in fiction. Dev. Psychol. 60:1474–1481. doi: 10.1037/dev0001674

Johnson, D. K. (2010). “Against the Santa Claus lie,” in Christmas - Philosophy for Everyone: Better Than a Lump of Coal, ed S. C. Lowe (Blackwell Publishing Ltd.), 137–150. doi: 10.1002/9781444325386.ch12

Koenig, H. G., and Büssing, A. (2010). The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): a five-item measure for use in epidemological studies. Religions, 1, 78–85. doi: 10.3390/rel1010078

Kowitz, G. T., and Tigner, E. J. (1961). Tell me about Santa Claus: a study of concept change. Elem. Sch. J. 62, 130–133. doi: 10.1086/459946

Landis, J. R., and Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33, 159. doi: 10.2307/2529310

Mann, S., Calvin, A., Lenhart, A., and Robb, M. (2025). The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Kids Zero to Eight, 2025. Common Sense Media. Available online at: https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/the-2025-common-sense-census-media-use-by-kids-zero-to-eight (Accessed August 4, 2025).

Martarelli, C. S., Mast, F. W., Lage, D., and Roebers, C. M. (2015). The distinction between real and fictional worlds: investigating individual differences in fantasy understanding. Cogn. Dev. 36, 111–126. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2015.10.001

Mills, C. M., Goldstein, T. R., Kanumuru, P., Monroe, A. J., and Quintero, N. B. (2024). Debunking the Santa myth: the process and aftermath of becoming skeptical about Santa. Dev. Psychol. 60, 1–16. doi: 10.1037/dev0001662

Pew Research Center. (2022). How the U.S. Religious Landscape Could Change Over the Next 50 Years. Pew Research Center.

Phelps, K. E., and Woolley, J. D. (1994). The form and function of young children's magical beliefs. Dev. Psychol. 30, 385–394. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.30.3.385

Prentice, N. M., Manosevitz, M., and Hubbs, L. (1978). Imaginary figures of early childhood: Santa Claus, Easter Bunny, and the Tooth Fairy. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 48, 618–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1978.tb02566.x

Ronfard, S., Chen, E. E., and Harris, P. L. (2021). Testing what you're told: young children's empirical investigation of a surprising claim. J. Cogn. Dev. 22, 426–447. doi: 10.1080/15248372.2021.1891902

Rosengren, K. S., and French, J. A. (2013). “Magical thinking,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Development of Imagination, ed M. Taylor (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 43–60. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195395761.013.0004

Rosengren, K. S., and Hickling, A. K. (1994). Seeing is believing: children's explanations of commonplace, magical, and extraordinary transformations. Child Dev. 65, 1605–1626. doi: 10.2307/1131283

Rosengren, K. S., and Hickling, A. K. (2000). “Metamorphosis and magic,” in Imagining the Impossible: Magic, Scientific, and Religious Thinking in Children, eds K. S. Rosengren, C. N. Johnson, and P. L. Harris (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 75–98. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511571381.004

Rosengren, K. S., Kalish, C. W., Hickling, A. K., and Gelman, S. A. (1994). Exploring the relation between preschool children's magical beliefs and causal thinking. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 12, 69–82. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-835X.1994.tb00619.x

Samuels, A., and Taylor, M. (1994). Children's ability to distinguish fantasy events from real-life events. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 12, 417–427. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-835X.1994.tb00644.x

Santos, R. M., Zanette, S., Kwok, S. M., Heyman, G. D., and Lee, K. (2017). Exposure to parenting by lying in childhood: associations with negative outcomes in adulthood. Front. Psychol. 8:260549. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01240

Setoh, P., Zhao, S., Santos, R., Heyman, G. D., and Lee, K. (2020). Parenting by lying in childhood is associated with negative developmental outcomes in adulthood. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 189:104680. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2019.104680

Sharon, T., and Woolley, J. D. (2004). Do monsters dream? Young children's understanding of the fantasy/reality distinction. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 22, 293–310. doi: 10.1348/026151004323044627

Shtulman, A., and Carey, S. (2007). Improbable or impossible? How children reason about the possibility of extraordinary events. Child Dev. 78, 1015–1032. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01047.x

Shtulman, A., and Yoo, R. I. K. (2015). Children's understanding of physical possibility constrains their belief in Santa Claus. Cogn. Dev. 34, 51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2014.12.006

Skolnick, D., and Bloom, P. (2006). What does Batman think about SpongeBob? Children's understanding of the fantasy/fantasy distinction. Cognition 101, 9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2005.10.001

Taggart, J., Eisen, S., and Lillard, A. S. (2019). The current landscape of US children's television: violent, prosocial, educational, and fantastical content. J. Child. Media 13, 276–294. doi: 10.1080/17482798.2019.1605916

Taylor, M., and Carlson, S. M. (2000). “The influence of religious beliefs on parental attitudes about children's fantasy behavior,” in Imagining the Impossible: Magic, Scientific, and Religious Thinking in Children, eds K. S. Rosengren, C. N. Johnson, and P. L. Harris (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 247–268. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511571381.010

Woolley, J. D., Boerger, E. A., and Markman, A. B. (2004). A visit from the Candy Witch: factors influencing young children's belief in a novel fantastical being. Dev. Sci. 7, 456–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00366.x

Woolley, J. D., and Cox, V. (2007). Development of beliefs about storybook reality. Dev. Sci. 10, 681–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00612.x

Keywords: children, fantasy beliefs, parental support, religious beliefs, Santa Claus

Citation: Yoo SH, Jiang MJ and Rosengren KS (2025) “Why Santa but not witches?”: Parents' reasoning behind encouraging and discouraging fantasy beliefs in children. Front. Dev. Psychol. 3:1703073. doi: 10.3389/fdpys.2025.1703073

Received: 10 September 2025; Revised: 27 October 2025;

Accepted: 06 November 2025; Published: 02 December 2025.

Edited by:

Igor Bascandziev, Harvard University, United StatesReviewed by:

Carolyn Palmquist, Amherst College, United StatesBeth Boerger, Slippery Rock University of Pennsylvania, United States

Copyright © 2025 Yoo, Jiang and Rosengren. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Seung Heon Yoo, c3lvbzIyQHVyLnJvY2hlc3Rlci5lZHU=

Seung Heon Yoo

Seung Heon Yoo Matthew J. Jiang2

Matthew J. Jiang2 Karl S. Rosengren

Karl S. Rosengren