- WHO Collaborating Centre, Department of Primary Care and Public Health, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom

Background: The electronic health record (EHR) has been widely implemented internationally as a tool to improve health and healthcare delivery. However, EHR implementation has been comparatively slow amongst hospitals in the Arabian Gulf countries. This gradual uptake may be linked to prevailing opinions amongst medical practitioners. Until now, no systematic review has been conducted to identify the impact of EHRs on doctor-patient relationships and attitudes in the Arabian Gulf countries.

Objective: To understand the impact of EHR use on patient-doctor relationships and communication in the Arabian Gulf countries.

Design: A systematic review of English language publications was performed using PRISMA chart guidelines between 1990 and 2023.

Methods: Electronic database search (Ovid MEDLINE, Global Health, HMIC, EMRIM, and PsycINFO) and reference searching restricted to the six Arabian Gulf countries only. MeSH terms and keywords related to electronic health records, doctor-patient communication, and relationship were used. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) quality assessment was performed.

Results: 18 studies fulfilled the criteria to be included in the systematic review. They were published between 1992 and 2023. Overall, a positive impact of EHR uptake was reported within the Gulf countries studied. This included improvement in the quality and performance of physicians, as well as improved accuracy in monitoring patient health. On the other hand, a notable negative impact was a general perception of physician attention shifted away from the patients themselves and towards data entry tasks (e.g., details of the patients and their education at the time of the consultation).

Conclusion: The implementation of EHR systems is beneficial for effective care delivery by doctors in Gulf countries despite some patients' perception of decreased attention. The use of EHR assists doctors with recording patient details, including medication and treatment procedures, as well as their outcomes. Based on this study, the authors conclude that widespread EHR implementation is highly recommended, yet specific training should be provided, and the subsequent effect on adoption rates by all users must be evaluated (particularly physicians). The COVID-19 Pandemic showed the great value of EHR in accessing information and consulting patients remotely.

Background

Continuity of patient care and overall healthcare safety are strongly associated with reliable medical records. Traditionally, medical records have used paper-based systems to record relevant details such as treatment and outcomes. However, in recent years, medical organisations are increasingly turning to computerisation for managing the plethora of data surrounding each patient entering the health system. The electronic health record (EHR) is a promising tool for enhancing national and international healthcare, particularly primary care delivery (1). An EHR can be defined as an application environment that captures the individual clinical data of patients, is linked to a clinical decision support system, and allows computerised order entry and clinical documentation applications (2). Electronic health records were initially developed and used at academic medical facilities, but many leading providers in the health industry are implementing computerised clinical record systems to manage the huge volume of clinical, administrative, and regulatory information that occurs in contemporary health care (3). The COVID-19 Pandemic and the need for virtual care demonstrated how essential EHRs are in delivering effective care remotely in both primary and hospital care settings.

Introducing any new information technology system into an organisation leads to changes in processes and workflows, which can lead to user dissatisfaction as they encounter teething problems in the system, bugs, or even simple annoyance at the requirement to learn a new way of doing things (4). Although EHRs are gradually entering widespread use within the Arabian Gulf, their impact on physician attitudes and the patient-doctor relationship remains to be determined. A previous systematic review has examined the impact of EHRs on patient-physician communication, finding no significant change in patient satisfaction or patient-doctor communication (5). However, this work focused on Western (Europe, United States, Australia) medical facilities; thus, the relevance to the culturally differing healthcare systems of the Gulf countries is still to be seen.

To shed light on this field, this systematic literature review seeks to understand the impact of EHR use on patient-doctor relationships and communication in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standards.

It was performed based on the methods of Alkureishi et al. (5). This study conducted a systematic electronic search of the English literature in Ovid MEDLINE, HMIC (Health Management Information Consortium), Eastern Mediterranean Index Medicus (IMEMR), Global Health, and APA PsycINFO between December 2021 and Sep 2023, with no date limit. Moreover, cited references searching of prior reviews and a manual search were performed with Scopus, Google Scholar, PubMed and The Cochrane Library.

The search on all databases was ((“electronic w/1 record”) OR (“EMR system”) OR (“computer w/1 record”) OR (“Medical Records Systems, Computerized”)) AND ((“middle AND east”) OR (“gulf AND cooperation AND council”) OR (“GCC”) OR (“KSA”) OR (“UAE”) OR (“saudi AND arabia”) OR (“Oman”) OR (“Bahrain”) OR (“Qatar”) OR (“Kuwait”) OR (“united AND arab AND emirates”) OR (“arab AND states”)).

The systematic search included all relevant studies by exploring Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and keywords related to electronic health records and doctor-patient communication and relationship. The selection of search terms was performed in consultation with a biomedical librarian.

To explore publication bias and mirror Alkureishi et al. (5), unpublished studies were searched for in past meeting abstracts of the Society of General Internal Medicine, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the International Conference on Communication in Healthcare and the European Association of Communication in Healthcare.

Only studies related to EHR use, and face-to-face patient-doctor communication or relationship were included; editorials and commentaries were excluded. All study designs, and all patient populations were included, but the search was restricted to studies on the six Gulf countries (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates). Studies exclusively reported physician attitudes, perceptions, and other interactions, but face-to-face patient-doctor relations (i.e., remote online access) were discarded.

Study selection

After duplicate removal, title and abstract screening were performed by the author and an independent reviewer. When titles or abstracts were unclear, they were included in full-text screening, followed by a second independent review. Quality assessment of the final selection was performed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS).

Data synthesis and analysis

Studies were compared by the study population, design and outcomes and sorted according to the data collection method. They were then organised in a data extraction table. Initial codes relating to the research question were generated to capture the ideas from the studies. Themes were defined from recurring patterns that provided insights into the effects of EHR implementation on patient-doctor interactions.

The data collected did not allow for a meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity in interventions, methodology, and outcomes of the studies included. Thus, a narrative synthesis was conducted.

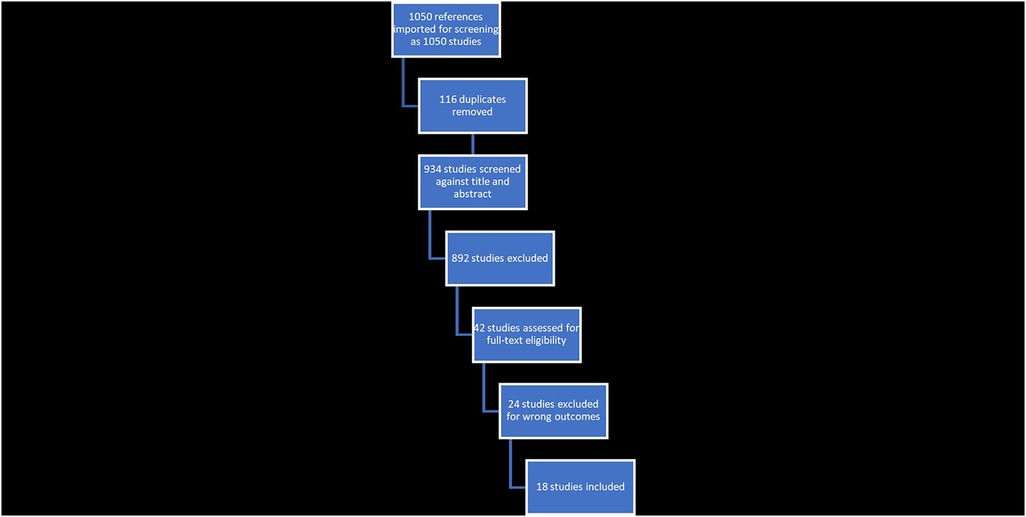

The initial search provided a total of 94 studies. From these, 93 studies remained for screening following the removal of duplicates. Manual search and backward reference screening produced a further 7 items. Seventy studies were excluded in an initial assessment (e.g., references lacking an abstract or unrelated to health). A detailed analysis of the remaining 30 studies was performed. As part of this detailed analysis, 15 studies were excluded as irrelevant to electronic health records or not presenting a doctor-patient relationship outcome. The 18 remaining studies were then included. An overview of this process is shown in Figure 1.

Data availability

The data supporting this systematic review are from previously reported studies and datasets. Details of the publications used in this systematic review are included in Table 1.

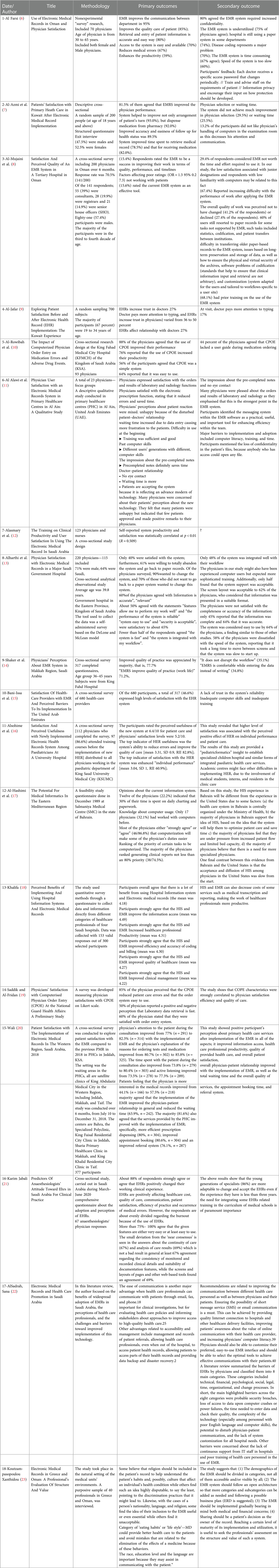

Table 1. Summary of the studies extracted that show the relationship between doctors and patients when using the EMRs.

Results

Figure 1 shows the number of studies identified, excluded (duplication, not EHR-focused), and selected with the criteria for the systematic review. This process generated 18 eligible articles.

Study characteristics

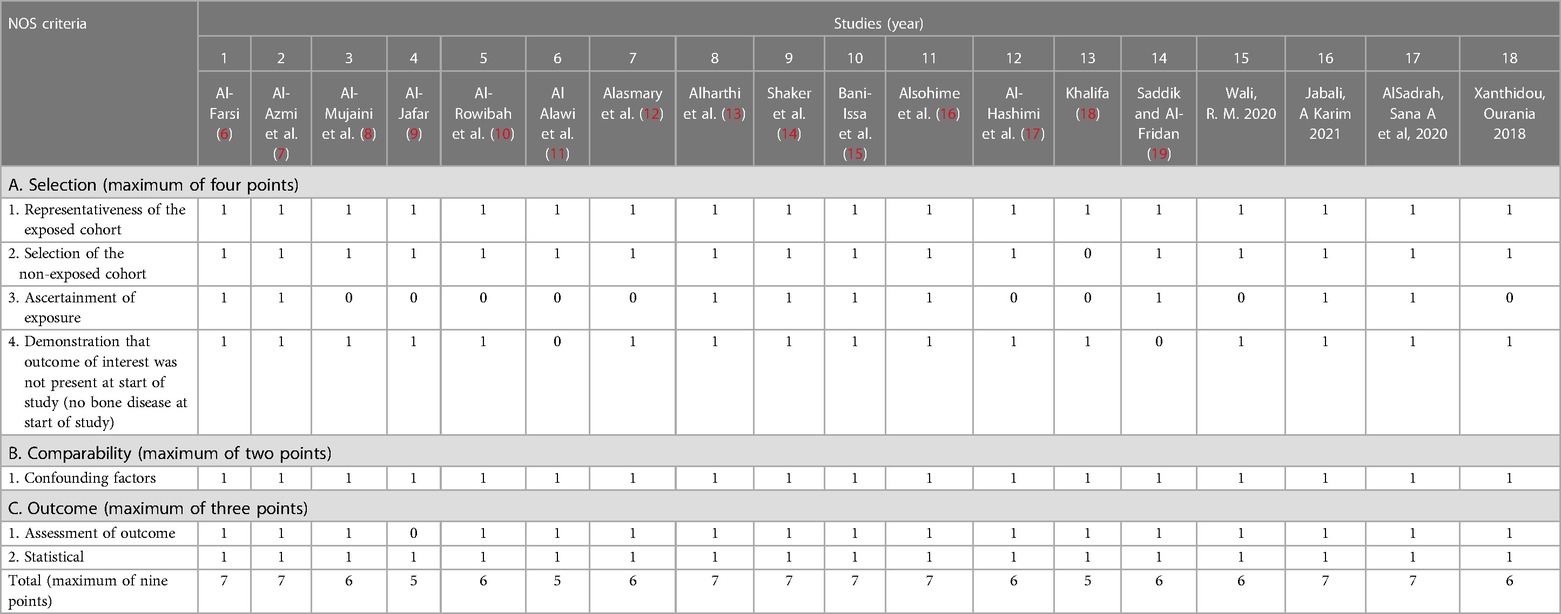

A summary of the results found for each of the 18 articles is provided in Table 1 (6–24). The articles that met the inclusion criteria were assessed to determine the characteristics and effect of EHR implementation in GCC countries, including a summary of the study features such as information on doctor communication, quality of care, medication error, data retrieval and waiting time. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was applied for quality assessment, as shown in Table 2. Publication dates ranged from 1992 to 2021. The number of participants in each study varied from 23 to 700, including male and female healthcare workers.

Effect of EMR on quality of care

Almost two-thirds of the studies (72%) found that EHR improves the quality of care for patients, noting that retrieval and entry of patient information is more straightforward and more accurate, access to the system is efficient, and the presence of an EHR reduces medical errors and enhances work productivity (6, 7, 10, 14, 16, 18–24) and comfort while entering the data through typing instead of writing (14). This general finding supports the previously shown positive impact of advanced technology in the healthcare sector and supports the desire of GCC healthcare providers to adopt paperless systems (10, 17). Nevertheless, lack of reliability or completeness of data (13, 15) and gaps in users' computer skills (15, 17) are also reported.

Effect of EHR on doctor-patient relations

The disadvantages of EHRs listed in the assessed publications included concerns about confidentiality (6, 11), general underutilisation of the system (6, 7), and a need for applicable or flexible disease coding (6). In Kuwait (7, 9), the participants disliked the requirement for physicians to work with the computer in the examination room. In Al Alawi's study in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), this behaviour was perceived as reduced attention and communication, lack of eye contact and added overall waiting time (11). Increasing difficulty with work performance after applying the EHR system has also been reported (8). For example, it has been mentioned that the system was inadequate (24), slow (6, 19) or lacked a user guide during medication ordering (10).

Discussion

This review investigates the impact of EHR systems on the relationship between doctors and patients in the Gulf countries. Our results showed that the EHR facilitates the development of an environment in which all relevant patient clinical data is captured, which in turn helps doctors to make decisions that directly influence patient outcomes. Furthermore, in agreement with other literature, it has been observed that EHR facilitates communication between patients and doctors (5, 25). The enhanced communication between patients and doctors improves the overall quality of care delivery in healthcare settings, especially in the physician-focused healthcare systems in Gulf countries.

However, it has been observed that some patients would like more satisfaction with respect to the implementation of EHR in the healthcare setting. There is a sense that doctors shift attention away from their patients and towards the recording of their entries. Therefore, patients feel dissatisfied, feeling doctors require more time for “data entry” than they do to assess the presenting patient.

Implementation of EHR was described as improving the transmission of accurate and reliable patient information, reducing chances of medication errors and “lost files”. Furthermore, it was observed that the use of EHR improves the ability of physicians to note relevant information at the time of consultation rapidly. This, in turn, allows them to invest more time in decisions relating to medication and treatment, thereby improving the quality of care delivered to the patients. Despite this, it should also be noted that the implementation of EHR leads to large changes in physician workflow and processes, which may lead to increased errors during this transition period and thus adversely affect patient outcomes. As revealed in this study, the introduction of EHR systems brings about significant changes in the daily routines of healthcare professionals. These transitional challenges may contribute to a temporary increase in errors during the initial stages of implementation, necessitating the need for comprehensive change management strategies. It is imperative that healthcare organisations pay close attention to mitigating these disruptions to maintain the quality of patient care.

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that while EHRs are demonstrated to enhance healthcare delivery in the Gulf countries overall, there exists a divergence in perspectives between healthcare providers and patients. Physicians often perceive the benefits of EHRs, such as improved data accuracy and efficiency. However, patients may feel that these systems lead to reduced attention from their doctors, lack of eye contact, and extended waiting times. Addressing this disparity in perceptions through comprehensive education and transparent communication is pivotal to ensuring that the full potential of EHR systems is realised while simultaneously upholding patient satisfaction and trust in the healthcare system.

These behavioural outcomes are generally consistent with those previously observed in systematic Western healthcare facility reviews (5, 25–29). Similarities to this study include that effective communication of the benefits of EHRs to patients needed to be improved, leading to a general impression that physicians were spending more time on their computers than with the patients themselves. But that, nonetheless, led to enhanced surveillance and monitoring and decreased medication errors. Hence, it may be generally agreed that the benefits of EHRs are not sufficiently communicated to all stakeholders. Even though all the studies were of good quality according to the NOS, limitations of this study included a lack of data and publications from all Gulf countries on this topic. Future studies should tackle the EHR and patient-healthcare provider relationship to further explore the impact of digital transformation in health systems.

Recommendations

Through this review, it has been noted that there needs to be more computer skills and trust in the EHR system, which leads to problems in effective implementation. This, in turn, hampers the potential relationship between doctors and patients in Gulf countries. The authors provide the following suggestions to ensure the effective implementation of EHR in healthcare settings of Gulf countries:

• Physicians should be provided with specific training on the EHR system being implemented, preferably paired with general computer training in medical school and during the early years of the residency programmes. This is essential considering the huge surge of artificial intelligence and efforts to digitalise health systems.

• Trust in the system itself should be built by openly communicating the objectives and advantages of an EHR system to physicians. In addition, the system implementation outcomes should also be communicated by doctors to patients. This will help to improve patient perspectives of the change and reduce overall dissatisfaction.

Conclusion

Implementing EHR systems is beneficial for effective care delivery by doctors in the Gulf countries. EHR assists doctors with recording patient details, including medication and treatment procedures, as well as their outcomes. Despite the patient's perception of decreased attention, EHR promotes and enhances healthcare delivery in the GCC. The EMR has the potential to be a key tool for improving continuity of care in the GCC by flagging up follow-up dates and tests, medications, and overall surveillance. Based on this study, the authors conclude that widespread EHR implementation is highly recommended. However, specific training should be provided, and all users' subsequent effects on adoption rates must be evaluated (particularly physicians). The COVID-19 pandemic showed the great value of EHR in accessing information and consulting patients remotely.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CT and MR collected data, performed the analysis, and wrote the paper. AA: wrote initial draft idea. SR reviewed the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This paper is not funded by any organisation. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mouhab Jamaladeen for helping in the initial screening process.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Denomme LB, Terry AL, Brown JB, Thind A, Stewart M. Primary health care teams’ experience of electronic medical record use after adoption. Fam Med. (2011) 43:638–42.22002775

2. HIMSS Dictionary of healthcare information technology terms, acronyms and organizations. 3rd edn. Chicago, IL: HIMSS Publishing (2013). p. 52

3. Evans RS Electronic health records: then, now, and in the future. Yearb Med Inform. (2016) (Suppl 1):S48–61. Published May 20, 2016. doi: 10.15265/IYS-2016-s006

4. Singh R, Singh A, Singh DR, Singh G. Improvement of workflow and processes to ease and enrich meaningful use of health information technology. Adv Med Educ Pract. (2013) 4:231–6. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S53307

5. Alkureishi MA, Lee WW, Lyons M, Press VG, Imam S, Nkansah-Amankra A, et al. Impact of electronic medical record use on the patient–doctor relationship and communication: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. (2016) 31(5):548–60. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3582-1

6. Al Farsi MA. Use of electronic records in Oman. West DJ Jr. (2006) 30(1):17–22. doi: 10.1007/s10916-006-7399-7

7. Al-Azmi SF, Mohammed AM, Hanafi MI. Patients’ satisfaction with primary health care in Kuwait after electronic medical record implementation. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. (2006) 81(5–6):277–300.18706302

8. Al-Mujaini A, Al-Farsi Y, Al-Maniri A, Ganesh A. Satisfaction and perceived quality of an electronic medical record system in a tertiary hospital in Oman. Oman Med J. (2011) 26(5):324–8. doi: 10.1177/183335830903800205

9. Al-Jafar E. Exploring patient satisfaction before and after electronic health record (EHR) implementation: the Kuwait experience. Perspectives in Health Information Management. (2013) 10:1c.23805063

10. Al-Rowibah FA, Younis MZ, Parkash J. The impact of computerized physician order entry on medication errors and adverse drug events. J Health Care Finance. (2013) 40(1):93–102.24199521

11. Al Alawi S, Al Dhaheri A, Al Baloushi D, Al Dhaheri M, Prinsloo EA. Physician user satisfaction with an electronic medical records system in primary healthcare centres in Al Ain: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. (2014) 4(11):e005569. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005569

12. Alasmary M, El Metwally A, Househ M. The association between computer literacy and training on clinical productivity and user satisfaction in using the electronic medical record in Saudi Arabia education & training. J Med Syst. (2014) 38(8):69. doi: 10.1007/s10916-014-0069-2

13. Alharthi H, Youssef A, Radwan S, Al-Muallim S, Zainab AT. Physician satisfaction with electronic medical records in a major Saudi government hospital. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. (2014) 9(3):213–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2014.01.004

14. Shaker HA, Farooq MU, Dhafar KO. Physicians’ perception about electronic medical record system in makkah region, Saudi Arabia. Avicenna J. (2015) 5(1):1–5. doi: 10.4103/2231-0770.148499

15. Bani-Issa W, Al Yateem N, Al Makhzoomy IK, Ibrahim A. Satisfaction of health-care providers with electronic health records and perceived barriers to its implementation in the United Arab Emirates. Int J Nurs Pract. (2016) 22(4):408–16. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12450

16. Alsohime F, Temsah MH, Al-Eyadhy A, Bashiri FA, Househ M, Jamal A, et al. Satisfaction and perceived usefulness with newly-implemented electronic health records system among pediatricians at a university hospital. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. (2019) 169:51–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2018.12.026

17. Al-Hashimi MS, Pryor TA. The potential for medical informatics in the eastern Mediterranean region. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (1992) 8(1):198–209. doi: 10.1017/S0266462300008047

18. Khalifa M. Perceived benefits of implementing and using hospital information systems and electronic medical records. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2017) 238:165–8.28679914

19. Saddik B, Al-Fridan MM. Physicians’ satisfaction with computerised physician order entry (CPOE) at the national guard health affairs: a preliminary study. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2012) 178:199–206.22797042

20. Wali RM, Alqahtani RM, Alharazi SK, Bukhari SA, Quqandi SM. Patient satisfaction with the implementation of electronic medical records in the Western Region, Saudi Arabia, 2018. BMC Fam Pract. (2020) 21:37. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-1099-0

21. Karim Jabali A. Predictors of Anesthesiologists' attitude toward EHRs in Saudi Arabia for clinical practice. Inform Med Unlocked. (2021) 23:100555. doi: 10.1016/j.imu.2021.100555

22. AlSadrah SA. Electronic medical records and health care promotion in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. (2020) 41(6):583–9. doi: 10.15537/smj.2020.6.25115

23. Koutzampasopoulou Xanthidou O, Shuib L, Xanthidis D, Nicholas D. Electronic medical records in Greece and Oman: a professional's evaluation of structure and value. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15(6):1137. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15061137

24. Al-Azmi SF, Al-Enezi N, Chowdhury RI. Users’ attitudes to an electronic medical record system and its correlates: a multivariate analysis. Health Inf Manage J. (2009) 38(2):33–40.

25. Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, Maglione M, Mojica W, Roth E, et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med. (2006) 144:E12–22. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00125

26. Kaushal R, Shojania KG, Bates DW. Effects of computerized physician order entry and clinical decision support systems on medication safety: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. (2003) 163:1409–16. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.12.1409

27. Bennett JW, Glasziou PP. Computerised reminders and feedback in medication management: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Med J Aust. (2003) 178:217–22. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05166.x

28. Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, Rosas-Arellano MP, Devereaux PJ, Beyene J, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. (2005) 293:1223–38. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1223

Keywords: electronic health records, electronic medical records, information systems, computer records, EHR systems, GCC

Citation: Tabche C, Raheem M, Alolaqi A and Rawaf S (2023) Effect of electronic health records on doctor-patient relationship in Arabian gulf countries: a systematic review. Front. Digit. Health 5:1252227. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2023.1252227

Received: 3 July 2023; Accepted: 22 September 2023;

Published: 6 October 2023.

Edited by:

Vijayakumar Varadarajan, University of New South Wales, AustraliaReviewed by:

Najeeb Mohammed Al-Shorbaji, eHealth Development Association, JordanHosna Salmani, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Iran

© 2023 Tabche, Raheem, Alolaqi and Rawaf. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Celine Tabche Yy50YWJjaGUyMEBpbXBlcmlhbC5hYy51aw==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Celine Tabche

Celine Tabche Mays Raheem

Mays Raheem Arwa Alolaqi

Arwa Alolaqi