- 1Cardiovascular Research Center, Health Institute, Imam-Ali Hospital, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

- 2Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health, Health Sciences Research Center, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

- 3Department of Public Health, Asadabad School of Medical Sciences, Asadabad, Iran

- 4Department of Psychology, Faculty of Science and Letters, Agri Ibrahim Cecen University, Ağrı, Turkey

- 5Department of Social and Educational Sciences, Lebanese American University, Beirut, Lebanon

- 6Student Research Committee, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

- 7Department of Public Health, School of Health, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran

Background: The term infodemic refers to the proliferation of both accurate and inaccurate information that creates a challenge in identifying trustworthy and credible sources. Among the strategies employed to mitigate the impact of the infodemic, social media literacy has emerged as a significant and effective approach. This systematic review examines the role of social media literacy in the management of the infodemic.

Methods: Six databases, including SID, Magiran, Scopus, PubMed, Google Scholar and Web of Science were systematically searched using relevant keywords. We included the relevant publications between 2012 and 2023 in our analysis. To ensure a qualitative assessment of the studies, we used the STROBE and AMSTAR checklists as evaluation tools. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guideline was used for the design of this review study. Finally, we organized the studies into groups based on similarities and retrieved and analyzed evidence pertaining to the challenges and opportunities identified.

Results: Eleven papers were included in this study after reviewing the retrieved studies. Five of them examined the effect of social media literacy and health literacy on acceptance of health behaviors. Four studies investigated the role of media literacy in managing misinformation and fake news related to health. Two studies focused on infodemic management and promoting citizen engagement during health crises. Results showed that health-related infodemics are derived from the users' lack of media knowledge, distrust of government service systems, local influencers and peers, rapid circulation of information through mass media messages, weakness of solutions proposed by health care providers, failure to pay attention to the needs of the audience, vertical management, and inconsistency of published messages.

Conclusion: The findings of this study highlight the importance of increasing social media literacy among the general public as a recognized strategy for managing the infodemic. Consequently, it is recommended that relevant organizations and institutions, such as the Ministry of Health, develop targeted training programs to effectively address this need.

1 Introduction

The term “infodemic” (1, 2) indicates an extreme volume of information that is typically unreliable and spreads rapidly, especially during the management of a viral epidemic (3, 4). Also, the term infodemic refers to information overload during an epidemic in both digital and physical environments (5, 6). This issue is of particular importance in health-related matters, because the dissemination of misinformation and rumors, particularly through virtual platforms, hinders the effectiveness of public health efforts (6).

The effectiveness of health solutions can be undermined by the creation of confusion and uncertainty among audiences (7, 8) During a pandemic or other health threat, it becomes more important than ever for people to have access to accurate information and they often search for information from multiple sources to increase their awareness (4). However, in the absence of a reliable and transparent source there is a risk that rumors and false information will influence people's understanding of the situation. This risk increases especially through virtual platforms (9).

COVID-19 misinformation and fake news have spread rapidly through social media channels (9). Unfortunately, this increase was accompanied by the dissemination of numerous false and incorrect pieces of information and data. Consequently, it became challenging for audiences to differentiate between reliable information and misleading content, hindering their ability to effectively diagnose and adopt the practical solutions provided by healthcare providers (10). In some cases, this issue prevented people from receiving vaccines or health care and led to a lack of trust in government and public health processes (11).

The Internet is a resource that can be used to access health information. However, it is important to acknowledge that in this context, the spread of fake news and false information tends to outpace the dissemination of fact-based information, contributing to the challenges faced in promoting accurate health information Fake news and false information spread faster and more widely than factual information (12).

Several studies have examined the effects of the infodemic, especially how social behaviors are influenced by such misinformation. In particular, the evaluation of information-related concepts, such as the impact on human lives and societies, the frequency and the most common sources of widespread unreliable data, using comprehensive and evidence-based criteria, has attracted more attention (13–16). In certain countries with a health system centered around family doctors, these doctors serve as the primary gatekeepers of health. In the face of an information epidemic pertaining to health and well-being, they play a crucial role as guides and leaders, actively working to persuade and guide individuals in their societies. In contrast, countries like the United States have a healthcare system that operates on a free market basis, where individuals have the freedom to choose their desired healthcare services (17).

Iran's healthcare system is a combination of these two systems. In Iran, health services (e.g., vaccinations) are the responsibility of the government, and medical services are largely provided in the free market. In such systems, the flow of fake news is much smoother than real news in various fields (18). However, the advent of social media has opened up vast communication platforms where news and information, irrespective of their veracity, have the potential to impact human societies at an unprecedented speed (19).

According to Dutta et al. misinformation has been disseminated through social media (6). The emergence of social media has changed the models of collective action that were based on assumptions about human communication styles. The spread of false information on social networks seems inevitable in times of health and social crises (20).

Social media literacy (SML) is widely regarded as the capacity to critically assess the information that audiences consume or produce, thereby safeguarding them against the dissemination of false information. SML resembles a dietary regimen that astutely attends to the suitability of its constituents, distinguishing between those that are beneficial and those that are detrimental, and determining what ought to be ingested and what ought to be avoided, as well as establishing the foundation for the consumption of each substance. It furnishes individuals with the aptitude to effectively discern and navigate media content, thereby facilitating well-informed decision-making and favorable outcomes (21).

People who have higher SML take a critical stance toward the barrage of media messages. Such individuals act as active elements in society and not only face critical situations against fake news and misinformation but also the expansion of this chain (22). During the health crisis, people with lower SML, tend to use fewer health services and preventive solutions provided by the health system. Consequently, they ended up requiring more emergency services and specialized care during the COVID-19 pandemic (21).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a strong need for reliable sources to address citizens' questions and alleviate their doubts. The initial shock caused by the widespread outbreak of the virus created fertile ground for the emergence of rumors (6, 7, 21).

Improving the SML (which refers to «all media», including television and film, radio and recorded music, print media, the internet and other new digital communication technologies) of media audiences and users of social networks is the most important way to protect people from the spread of misinformation in health crises because SML is a skill that is nurtured by the users' access to reliable and accurate sources that support timely and necessary information (7, 21). Although the field of research on the effectiveness of SML is in its infancy, several studies have tested the role of SML in analyzing media messages and improving one's choices on various health topics (21–23).

Despite the number of studies conducted, the findings have yielded mixed results, leaving several unanswered questions in this field. On the other hand, to date, no comprehensive review of the available research has been conducted in the area of SML interventions with the aim of infodemics management. Furthermore, there has been a lack of systematic analysis to identify the key components that render interventions effective in promoting the accuracy and reliability of information. The understanding of how best to use information in a trustworthy manner remains limited. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to conduct a systematic review that examines the role of SML in effectively addressing the challenges posed by the infodemic. In fact, the researchers want to answer this question with a systematic review, “Is social media literacy effective in managing the infodemic?”

2 Materials and methods

This study reviews the evidence on the role of SML in the management of infodemics: The present study is a systematic review performed following the principles of PRISMA. This is a recognized standard for reporting evidence in systematic reviews. It consists of a 27-item checklist to assist reviewers in reporting key characteristics of a systematic review (24). In order to reduce publication bias, all steps of searching, evaluating and selecting articles in addition to data extraction were performed independently by two researchers. Any discrepancies or disagreements were thoroughly discussed until a consensus was reached.

2.1 Search strategy

To retrieve English articles, various search strategies were used, including databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Additionally, Persian national databases, including the Scientific Information Database (SID) and the Magiran database were searched to include relevant articles in the Persian language. The search did not include any time or language restrictions to ensure that all potentially relevant studies were retrieved. We included the relevant publications up to May 2023. The search for the resources in the mentioned scientific databases was independently conducted by two researchers utilizing the search strategy presented.

2.1.1 Infodemic-related terms [MEDLINE]

Infodemic[keyword] misinformation [keyword] OR disinformation [keyword] OR hoax [keyword] OR deception [Mesh] OR rumor [keyword] OR superstition [keyword, Mesh] OR misconception [keyword] OR misperception [keyword] OR fake news [keyword] OR false news [keyword] OR misleading information [keyword], OR Truthfulness information [keyword] OR SPAM information[keyword] Social advertising [keyword] social messages[keyword]

2.1.2 SML-related terms [MEDLINE]

All studies included SML [keyword] OR electronic skills [Mesh] OR mass media literacy[keyword], information literacy [Mesh] OR internet literacy [Mesh].

Searched using (All “A” terms) AND (All “B” terms)

All studies obtained from the various databases were entered into EndNote X8 software. Initially, duplicate studies were removed. Then, the title and abstract of the studies were reviewed. Following a rigorous assessment based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, unrelated studies were excluded from further analysis. In the eligibility stage, the full text of the studies was reviewed and studies that were not relevant to the purpose of the research were excluded. Finally, articles that met all inclusion criteria were considered for the qualitative assessment.

2.2 Study inclusion and evaluation

The search terms were oriented according to the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Results and Study Design (PICOS) approach, the methodology used to select studies for inclusion in the systematic search (24). All English-language studies focusing on the role of SML in the health information epidemic adhered to the following PICOS criteria:

• Population: adult women and men

• Intervention: Not applied

• Comparison: Not applied

• Outcome: Role of SML in the health information epidemic

• Type of study: Cross-sectional studies, Brief overview, Experimental

2.3 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were original research articles, availability of the full text of the article, and qualitative studies, while intervention studies, conference abstracts, and letters to the editor were excluded from the study.

2.4 Quality assessment

Two different researchers independently assessed the methodological quality of the studies using the cross-sectional studies evaluated with the STROBE checklist (25). The STROBE Statement is a checklist of 22 items relating to the article's title and abstract (item 1), the introduction (items 2 and 3), methods (items 4–12), results (items 13–17), discussion sections (items 18–21), and other information. A higher percentage of items conforming to the guidelines indicates higher methodological quality.

2.5 Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted based on a pre-prepared electronic checklist. The checklist consisted of various items, including the first author, year, country, sample size, questionnaire, and study population.

2.6 Risk of bias assessment

We followed the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook to develop risk criteria based on the following: (a) study design (b) participation rate and (c) adjustment for confounding. Therefore, we categorized the risk of bias according to the third criterion only.

2.7 Statistical analysis

Two independent researchers extracted the general characteristics of each study and classified them into four distinct categories: (1) reviews evaluating the negative effect of infodemia on health behaviors'; (2) reviews assessing the sources of infodemia; (3) reviews evaluating social media in the spread of fake news, rumors and the emergence of infodemia; and (4) reviews evaluating the relationship of media literacy in controlling invalid news.

We clustered papers based on similar properties related to the stated objective and reported outcomes. We summarized the challenges and opportunities associated with infodemics and misinformation. A third author verified the retrieved data, with another researcher resolving any disagreement between reviewers.

3 Results

3.1 Study characteristics

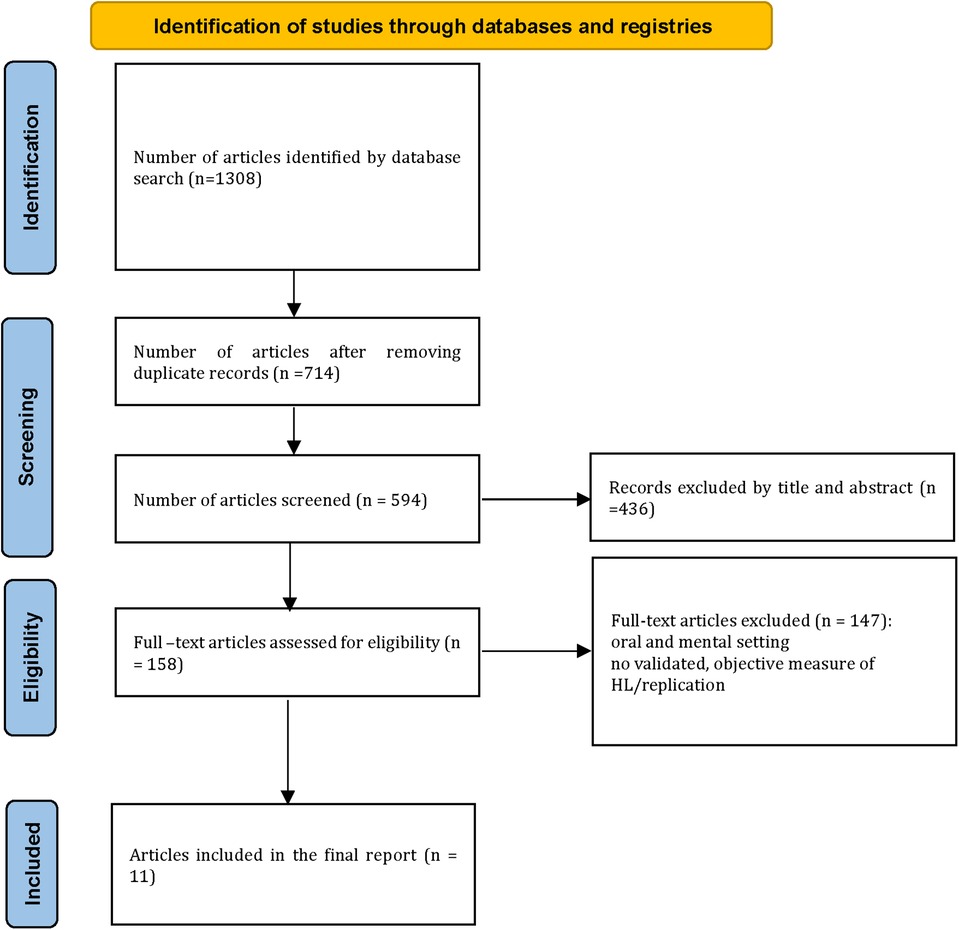

After the systematic search, a total of 1,308 potentially relevant articles were initially identified from selected databases. After removing 714 duplicate studies, the titles and abstracts of the remaining 594 studies were assessed. Based on this evaluation, 436 studies were excluded, leaving 158 papers for full-text assessment. Out of these, 147 studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, a total of 11 related articles were included in this study. The study selection process is visually depicted in the PRISMA flowchart, as shown in Figure 1.

3.2 Methodological quality

Upon appraisal using the AMSTAR critical domains for systematic reviews, it was observed that 12 out of the 15 reviews (85.7%) obtained critically low-quality scores across several major domains Only two reviews showed a moderate risk of bias in most domains. For cross-sectional studies satisfactory compliance was set at 52%, as has been done elsewhere.

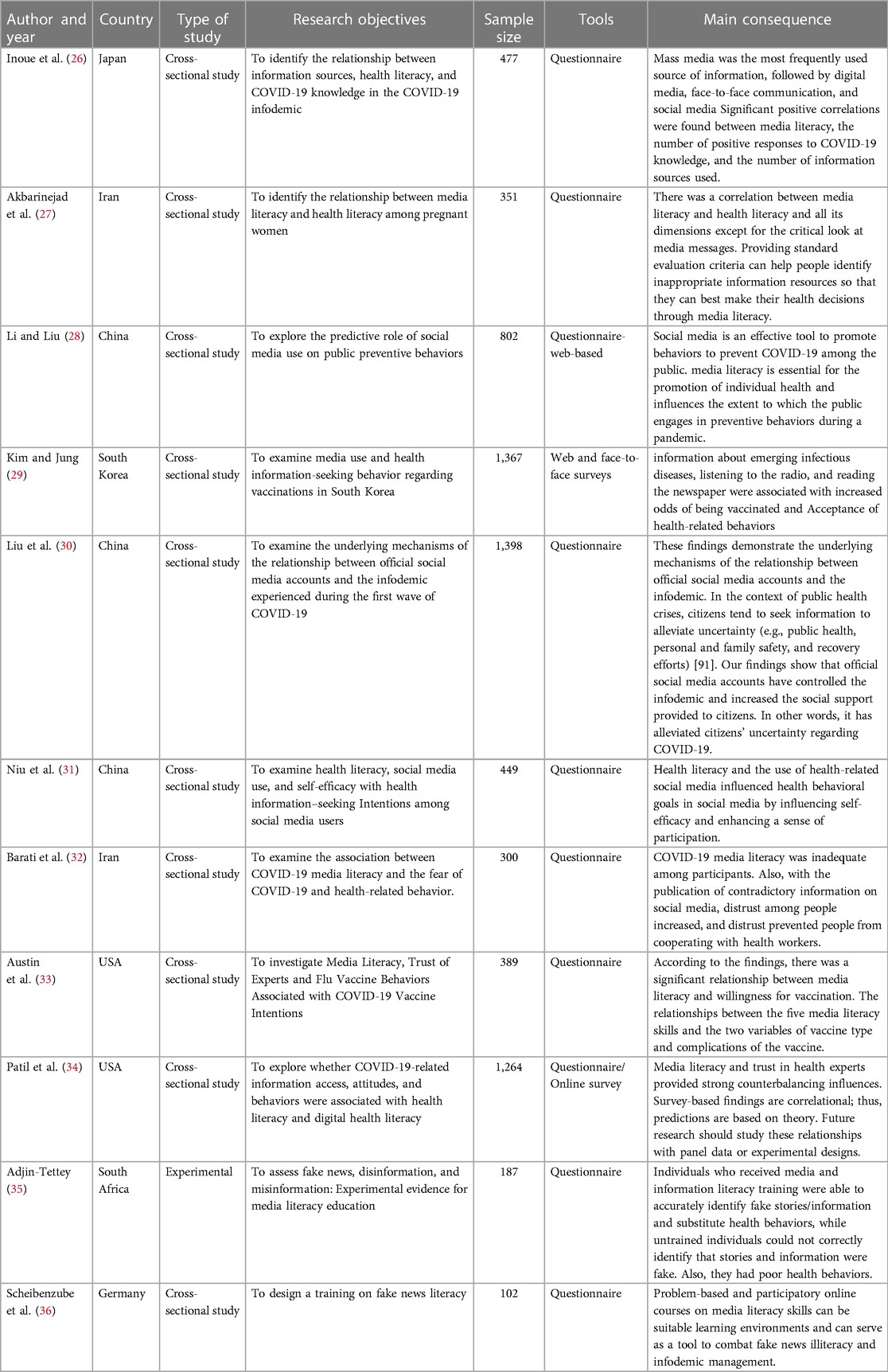

3.3 Study characteristics

We included the relevant publications between 2012 and 2023 in our analysis, without restrictions on publication time. The highest publication (3 articles = 27%) was related to China. The largest and smallest sample sizes were related to the study by Liu (2022) with 1,398% and 73% of them being cross-sectional studies. Table 1 shows the overall characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review.

The results showed that health-related infodemics are derived from the users' lack of media knowledge, distrust in government service systems, local influencers and peers, rapid circulation of misinformation through mass media messages, the inadequacy of solutions proposed by health care providers, failure to pay attention to the needs of the audience, vertical management, and contradiction of published messages.

On the other hand, during public health emergencies, mass media can propagate poor-quality information. It is evident that social media has emerged as an ideal channel for the dissemination of rumors, fake news, and general misinformation. Warning, threatening, misleading, shorter messages, the mix of written text and visual images and anecdotal evidence similar to popular culture also have a stronger effect on the dissemination of disinformation and audience acceptance.

In the majority of studies, training and improving skills in using social media and media literacy as a critical method and control strategy is recommended because media literacy plays an important role in reducing the amount of misinformation by limiting false information and directing people to evidence-based websites. For example, the most important cause of vaccine hesitancy messages, fake news, have been published in mass media.

The effect of fake news reduces the participation rate of different age groups in following health behaviors. The next proposed approach to managing the infodemic was community involvement. The findings of the studies highlighted that different age groups interact with the infodemic and the spread of fake news through social media.

4 Discussion

This systematic review is the first to evaluate the role of SML in the management of infodemics. Six studies examined the effect of SML on health literacy and acceptance of health behaviors. Among the included studies, four reviewed the role of media literacy in managing misinformation and fake news related to health.

The results of the studies showed that 63.23% of people were able to identify whether the information they received from social media about health-related behaviors was fake news. The findings from our study indicated that a substantial majority of individuals, specifically 71%, particularly in the young and middle-aged age groups, tend to seek information from social media rather than traditional media sources such as TV, radio, or newspapers. Furthermore, the majority of studies that assessed the consequences associated with misinformation on social media pointed to a negative effect on the increased dissemination of poor-quality health-related information during pandemics and diseases.

The publication of unreliable evidence on health issues during a health emergency contributes to the promotion of unscientific and ineffective solutions. The results obtained from the current review showed that SML is an important component of health literacy in promoting preventive strategies related to adherence to health behaviors.

The World Health Organization (23) recommends the implementation of programs aimed at strengthening critical thinking skills. Perazzo et al. (22) reported that higher levels of e-health literacy have led to greater adherence by healthcare workers to those measures designed to prevent and control occupational infections (23). Huhman et al. showed how a mass media campaign increased physical activity, produced positive changes, and prevented negative changes in health-related behaviors (9). Yoğurtcu and Ozturk Haney (10) showed that the development of strategies to improve media literacy among nurses can contribute to the maintenance of health-promoting behaviors among both nurses and their patients (37).

Health information-seeking behavior and media use significantly influence healthy lifestyles, early diagnosis, and sensible disease management (38). Alcott and Gentzkow, indicated that media literacy and e-health literacy are essential for improving people's health and influencing people's preventive behaviors during the pandemic (39). These skills provide the basis for people's participation and cooperation and break the dissemination of this information to other members of the society (38).

When fake news and/or misinformation become part of mainstream news consumption, they can lead to a decrease in trust, and an increase in misinformation (38, 40). Therefore, it is imperative that all information and communication actors are concerned about fake news and misinformation, and contribute to making more people aware of media literacy through proper education (41). For example, during a disease outbreak, the quality of information disseminated by the mass media is critical, as misinformation can also cause panic and lead people to trust harmful or ineffective treatments (42, 43).

According to the results of this study, People with low media literacy pay more attention to news headlines and their emotions in mass media, while technical methods of detecting fake news are more useful for determining the accuracy of information (9).

Infodemic management recognizes the importance of listening to individuals and engaging communities (8). When health authorities and policy-makers understand what issues are capturing people's attention and where there are information gaps, they can respond in real time with high-quality, evidence-based information and recommend interventions.

4.1 Limitations and future studies

Regarding the limitations, further cohort investigations might recognize the effects of social media literacy in the management of infodemics among different age and gender groups. The review studies in the past literature have not mentioned the relationship of social media literacy to the role of infodemics in the change and formation of behavior. This current review is noted as a torch because studies related to infodemics are relatively new and require further analysis and review. Researchers can examine the importance of the topic from other angles or may design qualitative studies to minimize the possibility of biased results.

5 Conclusion

This study provides evidence that media literacy creates awareness of the consequences of inaccurate information channels and enables information consumers to make informed judgments about information quality. This study highlights the importance of media and information literacy in promoting responsible information sharing. The findings indicate that individuals who possess media literacy skills are more inclined to verify the accuracy of information before sharing it with others. This emphasizes the significance of empowering information consumers with the necessary tools to critically evaluate and assess the reliability of the information they encounter. By partnering with the fields of behavioral science and impact evaluation, in addition to researchers, technical specialists, and social media experts, we can maximize these initiatives' effectiveness and inclusiveness, and get a better sense of their impact during a pandemic.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval for the study was obtained and approved by the Ethics Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. The ethics code assigned to this study is IR.KUMS.REC.1402.215.

Author contributions

AZ: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. RM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing – original draft. FD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MY: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. NM: Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft. NK: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. NN: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all the authors of the articles. This study is the result of research project No. 4020473 approved by the Student Research Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Zarocostas J. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet. (2020) 395(10225):676. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30461-X

2. Baines D, Elliott RJ. Defining misinformation, disinformation and malinformation: an urgent need for clarity during the COVID-19 infodemic. Discuss Pap. (2020) 20(06):20–06.

3. Cinelli M, Quattrociocchi W, Galeazzi A, Valensise CM, Brugnoli E, Schmidt AL, et al. The COVID-19 social media infodemic. Sci Rep. (2020) 10(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73510-5

4. Eysenbach G. How to fight an infodemic: the four pillars of infodemic management. J Med Int Res. (2020) 22(6):E21820. doi: 10.2196/21820

5. Kim L, Fast SM, Markuzon N. Incorporating media data into a model of infectious disease transmission. PLoS One. (2019) 14(2):e0197646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197646

6. Dutta B, Peng M-H, Chen C-C, Sun S-L. Role of infodemics on social media in the development of people’s readiness to follow COVID-19 preventive measures. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19(3):1347. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031347

7. Nejaddadgar N, Jafarzadeh M, Ziapour A, Rezaei F. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in ardabil: a web-based survey. Health Educ Health Promot. (2022) 10(2):221–5.

8. Nejhaddadgar N, Darabi F. Media literacy and health information epidemic. J Iran Health Sci Res. (2023) 22(3):355–8. doi: 10.61186/payesh.22.3.355

9. Huhman M, Potter LD, Wong FL, Banspach SW, Duke JC, Heitzler CD. Effects of a mass media campaign to increase physical activity among children: year-1 results of the VERB campaign. Pediatrics. (2005) 116(2):e277–e84. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0043

10. Yoğurtcu H, Ozturk Haney M. The relationship between e-health literacy and health-promoting behaviors of turkish hospital nurses. Glob Health Promot. (2022) 29(4):54–62. doi: 10.1177/17579759221093389

11. Perrone C, Fiabane E, Maffoni M, Pierobon A, Setti I, Sommovigo V, et al. Vaccination hesitancy: to be vaccinated, or not to be vaccinated, that is the question in the era of COVID-19. Public Health Nurs. (2023) 40(1):90–6. doi: 10.1111/phn.13134

12. Hurford B, Rana A, Sachan R. Narrative-based misinformation in India about protection against COVID-19: not just another “moo-point”. Indian J Med Ethics. (2022) 7(1):1–10. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2021.050

13. Gisondi MA, Chambers D, La TM, Ryan A, Shankar A, Xue A, et al. A stanford conference on social media, ethics, and COVID-19 misinformation (INFODEMIC): qualitative thematic analysis. J Med Int Res. (2022) 24(2):e35707. doi: 10.2196/35707

14. Gisondi MA, Barber R, Faust JS, Raja A, Strehlow MC, Westafer LM, et al. A Deadly Infodemic: Social Media and the Power of COVID-19 Misinformation. Canada: JMIR Publications Toronto (2022). p. e35552.

15. Pool J, Fatehi F, Akhlaghpour S. Infodemic, misinformation and disinformation in pandemics: scientific landscape and the road ahead for public health informatics research. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2021) 281:764–8. doi: 10.3233/SHTI210278

16. Shiraly R, Mahdaviazad H, Pakdin A. Doctor-patient communication skills: a survey on knowledge and practice of Iranian family physicians. BMC Family Pract. (2021) 22(1):130. doi: 10.1186/s12875-021-01491-z

17. Himelein-Wachowiak M, Giorgi S, Devoto A, Rahman M, Ungar L, Schwartz HA, et al. Bots and misinformation spread on social media: implications for COVID-19. J Med Int Res. (2021) 23(5):E26933. doi: 10.2196/26933

18. Cuan-Baltazar JY, Muñoz-Perez MJ, Robledo-Vega C, Pérez-Zepeda MF, Soto-Vega E. Misinformation of COVID-19 on the internet: infodemiology study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. (2020) 6(2):E18444. doi: 10.2196/18444

19. Starbird K, Maddock J, Orand M, Achterman P, Mason RM. Rumors, false flags, and digital vigilantes: misinformation on twitter after the 2013 Boston marathon bombing. IConference 2014 Proceedings (2014).

20. Malik A, Bashir F, Mahmood K. Antecedents and consequences of misinformation sharing behavior among adults on social media during COVID-19. SAGE Open. (2023) 13(1):21582440221147022. doi: 10.1177/21582440221147022

21. Izadi L, Taghdisi MH, Ghadami M, Delavar A, Sarokhani B. Identification of effective factors decision making in crisis in media rganization: a systematic review with emphasis on media literacy in health crisis (CORONA PANDEMIC. Iran J Health Educ Health Promot. (2021) 8(4):390–406. doi: 10.29252/ijhehp.8.4.390

22. Perazzo J, Reyes D, Webel A. A systematic review of health literacy interventions for people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. (2017) 21:812–21. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1329-6

23. Word Health Organization. Clinical Management of Severe acute Respiratory Infection When Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Infection is Suspected: Interim Guidance. World Health Organization (2020). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/10665-332299 (accessed January 28, 2020).

24. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J Clin Epidemiol. (2021) 134:103–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003

25. Adams AD, Benner RS, Riggs TW, Chescheir NC. Use of the STROBE checklist to evaluate the reporting quality of observational research in obstetrics. Obstetrics Gynecol. (2018) 132(2):507–12. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002689

26. Inoue M, Shimoura K, Nagai-Tanima M, Aoyama T. The relationship between information sources, health literacy, and COVID-19 knowledge in the COVID-19 infodemic: cross-sectional online study in Japan. J Med Int Res. (2022) 24(7):e38332. doi: 10.2196/38332

27. Akbarinejad F, Soleymani MR, Shahrzadi L. The relationship between media literacy and health literacy among pregnant women in health centers of isfahan. J Educ Health Promot. (2017) 6(17). doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.204749

28. Li X, Liu Q. Social media use, eHealth literacy, disease knowledge, and preventive behaviors in the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional study on Chinese netizens. J Med Int Res. (2020) 22(10):E19684. doi: 10.2196/19684

29. Kim J, Jung M. Associations between media use and health information-seeking behavior on vaccinations in South Korea. BMC Public Health. (2017) 17(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3954-4

30. Liu H, Chen Q, Evans R. How official social media affected the infodemic among adults during the first wave of COVID-19 in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19(11):6751. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19116751

31. Niu Z, Willoughby J, Zhou R. Associations of health literacy, social media use, and self-efficacy with health information–seeking intentions among social media users in China: cross-sectional survey. J Med Int Res. (2021) 23(2):e19134. doi: 10.2196/19134

32. Barati M, Bashirian S, Jormand H, Khazaei S, Jenabi E, Zareian S. The association between COVID-19 Media literacy and the fear of COVID-19 among students during coronavirus pandemic: a cross-sectional study. J Health Literacy. (2022) 7(2):46–58. doi: 10.22038/JHL.2022.61047.1228

33. Austin EW, Austin BW, Borah P, Domgaard S, McPherson SM. How media literacy, trust of experts and flu vaccine behaviors associated with COVID-19 vaccine intentions. Am J Health Promot. (2023) 37(4):464–70. doi: 10.1177/08901171221132750

34. Patil U, Kostareva U, Hadley M, Manganello JA, Okan O, Dadaczynski K, et al. Health literacy, digital health literacy, and COVID-19 pandemic attitudes and behaviors in US college students: implications for interventions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18(6):3301. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063301

35. Adjin-Tettey T. Combating fake news, disinformation, and misinformation: experimental evidence for media literacy education. Cogent Arts Human. (2022):2037229. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2022.2037229

36. Scheibenzuber C, Hofer S, Nistor N. Designing for fake news literacy training: a problem-based undergraduate online-course. Comput Hum Behav. (2021) 121:106796. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106796

37. Hong KJ, Park NL, Heo SY, Jung SH, Lee YB, Hwang JH, editors. Effect of e-health literacy on COVID-19 infection-preventive behaviors of undergraduate students majoring in healthcare. Healthcare. (2021) 9(5):573. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9050573

38. Scherer LD, McPhetres J, Pennycook G, Kempe A, Allen LA, Knoepke CE, et al. Who is susceptible to online health misinformation? A test of four psychosocial hypotheses. Health Psychol. (2021) 40(4):274. doi: 10.1037/hea0000978

39. Allcott H, Gentzkow M. Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. J Economic Perspect. (2017) 31(2):211–36. doi: 10.1257/jep.31.2.211

40. Mu Y, Niu P, Aletras N, editors. Identifying and characterizing active citizens who refute misinformation in social media. 14th ACM Web Science Conference 2022 (2022).

41. Knuutila A, Neudert L-M, Howard PN. Who is afraid of fake news? Modeling risk perceptions of misinformation in 142 countries. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinform Rev. (2022) 3(3). doi: 10.37016/mr-2020-97

42. Bodaghi A, Oliveira J. The theater of fake news spreading, who plays which role? A study on real graphs of spreading on twitter. Expert Syst Appl. (2022) 189:116110. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2021.116110

Keywords: social media literacy, infodemic, misinformation, health crisis, public health, systematic review

Citation: Ziapour A, Malekzadeh R, Darabi F, Yıldırım M, Montazeri N, Kianipour N and Nejhaddadgar N (2024) The role of social media literacy in infodemic management: a systematic review. Front. Digit. Health 6:1277499. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2024.1277499

Received: 14 August 2023; Accepted: 19 January 2024;

Published: 14 February 2024.

Edited by:

Muhammad Azeem Ashraf, Hunan University, ChinaReviewed by:

Lin Song, University of California, San Francisco, United StatesFatemeh Mohamadkhah, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Terri Elizabeth Workman, George Washington University, United States

© 2024 Ziapour, Malekzadeh, Darabi, Yıldırım, Montazeri, Kianipour and Nejhaddadgar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nazila Nejhaddadgar bmF6aWxhZGFkZ2FyNjBAZ21haWwuY29t

†ORCID Arash Ziapour orcid.org/0000-0001-8687-7484 Roya Malekzadeh orcid.org/0000-0001-9117-9592 Fatemeh Darabi orcid.org/0000-0002-4399-1460 Murat Yıldırım orcid.org/0000-0003-1089-1380 Nafiseh Montazeri orcid.org/0000-0002-7770-1660 Nazila Nejhaddadgar orcid.org/0000-0002-5594-0118

Arash Ziapour

Arash Ziapour Roya Malekzadeh

Roya Malekzadeh Fatemeh Darabi3,†

Fatemeh Darabi3,† Murat Yıldırım

Murat Yıldırım