- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Baylor Heart and Vascular Institute, Dallas, TX, United States

- 2Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States

- 3Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, MN, United States

- 4Division of Cardiology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS, United States

- 5Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 6Global Products and Services, Mayo Clinic Center for Innovation, Rochester, MN, United States

- 7Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of California, Irvine, CA, United States

- 8Center for Health Services and Outcomes Research, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 9Division of Cardiology, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 10Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Phoenix, AZ, United States

- 11Division of Clinical Trials and Biostatistics, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States

- 12Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Jacksonville, FL, United States

- 13Center for Clinical and Translational Science, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States

Background: Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is a widely underutilized secondary cardiovascular disease prevention strategy, due to a variety of barriers to participation that disproportionately impact women, minoritized racial and ethnic groups, and patients with low socioeconomic status. Destination Cardiac Rehab, a virtual world-based CR (VWCR) program designed by our team in collaboration with patients and community members to mitigate the barriers to CR participation, has demonstrated feasibility and acceptability. In anticipation of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to further validate the intervention, this qualitative descriptive analysis provides insights garnered from a patient/community/stakeholder-advisory board (PCS-AB, HEALERS) focus group series, convened to inform iterative refinements to a RCT protocol.

Methods and results: HEALERS participated in five 90-min virtual focus group sessions to provide feedback on various aspects of the VWCR intervention and the recruitment/retention strategies. Major themes were identified from participant feedback to inform revisions to the trial protocol. Illustrative quotes were selected to represent each theme. Twenty-two members were recruited with diverse sociodemographic and personal/professional backgrounds (mean age 59.3 ± 13 years, 50% female). Regarding trial recruitment, members recommended effective communication strategies, recruitment video suggestions, and expansion of recruitment settings. HEALERS emphasized the importance of feeling safe during exercise and social support in designing an effective VWCR intervention. Lastly, they identified reminder messages, tangible incentives, and fostering positive relationships with the CR staff as important retention tools.

Conclusions: A diverse PCS-AB was convened to better understand community needs to improve the patient-centric nature of Destination Cardiac Rehab in anticipation of an upcoming RCT. The HEALERS offered valuable insights that informed actionable changes to the RCT protocol.

Introduction

Community-engaged research (CER) approaches engage community members, patients and key stakeholders in collaboration with study teams to provide insight into community needs and promote healthcare equity (1). The literature demonstrates tremendous value in incorporating community members in the development and execution of novel digital health interventions in cultivating trusting relationships between patients and the health care team, to address health disparities, and ensure culturally sensitive interventions that better address patient needs (1–7). Patient advisory boards have been shown to optimize study design, increase diversity, and foster trust leading to more effective and impactful healthcare solutions (8–12). In collaboration with community members, our study team developed a virtual world-based cardiac rehabilitation (VWCR) program, Destination Cardiac Rehab, to address often overwhelming barriers to participation in traditional center-based cardiac rehabilitation (CBCR) of which <25% of eligible patients participate in despite extensive evidence demonstrating its benefits (13–19). These barriers are particularly burdensome for minoritized racial and ethnic groups, women, and patients with low socioeconomic status (SES) (20–22). Alternative platforms for cardiac rehabilitation (CR) delivery that provide more flexibility, such as home-based CR (HBCR) programs, have emerged in an effort to mitigate the barriers to CR participation but have not substantially improved CR participation (23–26). Incorporating mobile and internet technologies into these programs has shown promise in broadening CR engagement (27, 28).

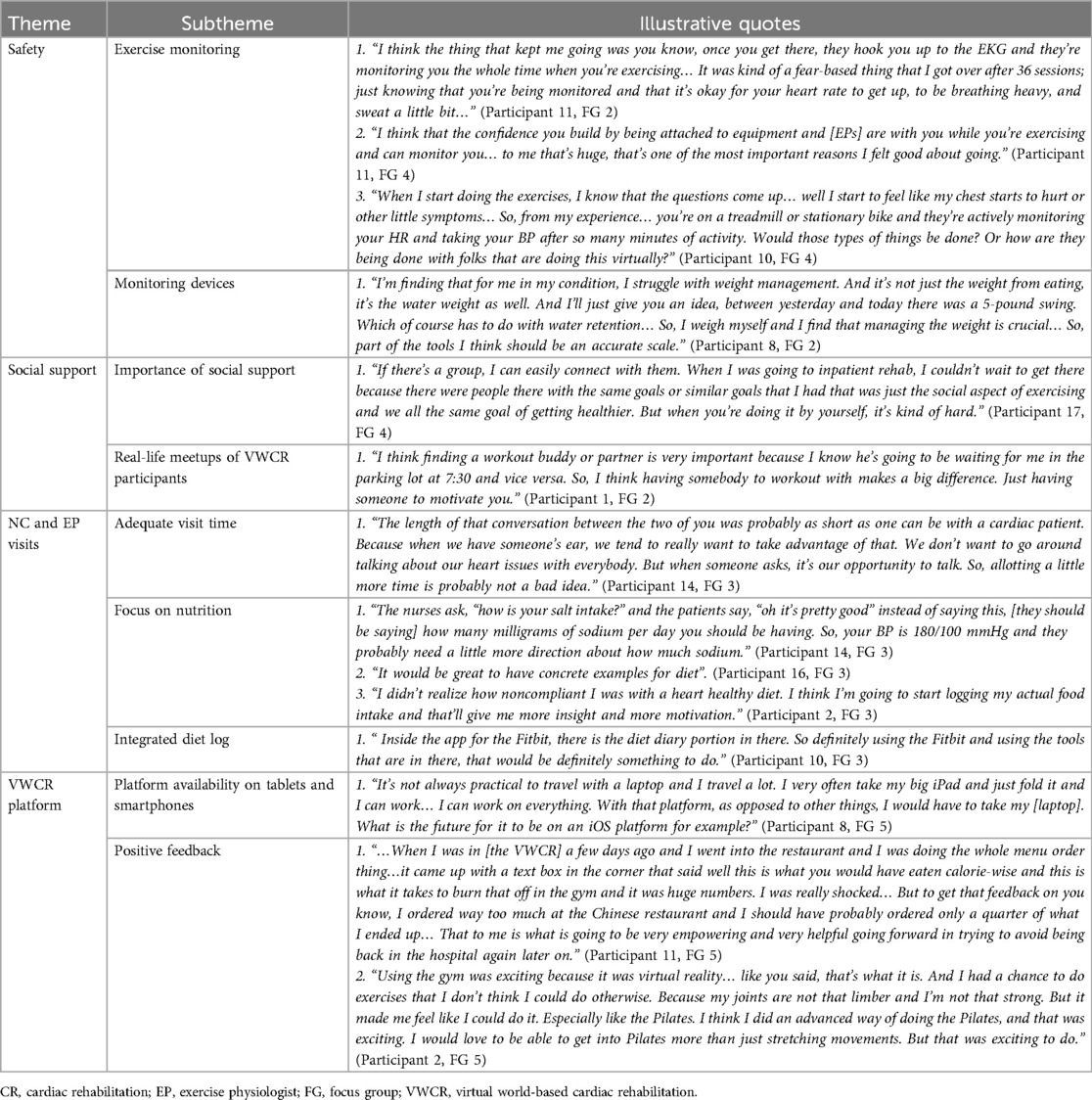

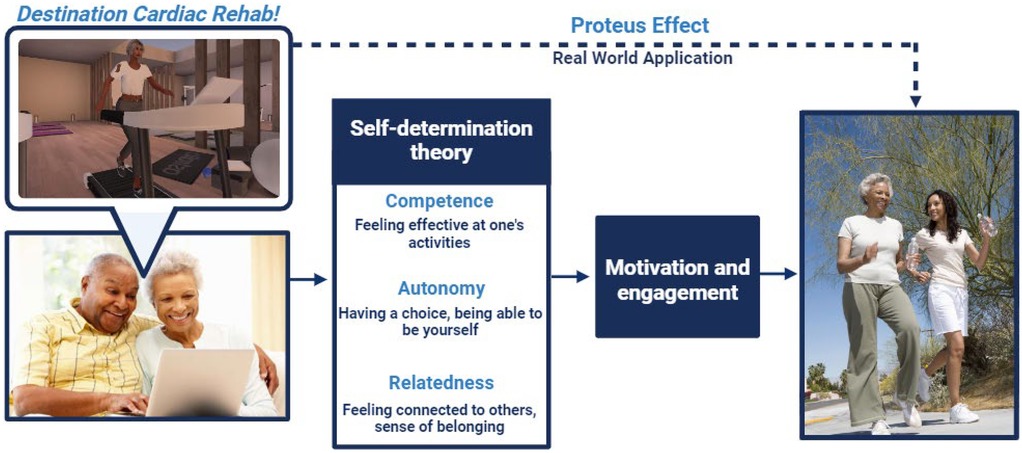

Destination Cardiac Rehab takes place in an immersive VW platform, Second Life®, and utilizes virtual avatars to simulate a real-world experience but from the convenience of any location (29). VW interventions capitalize on a phenomenon known as the “Proteus effect”, in which individuals integrate the behaviors and characteristics of their avatars in the VW into their own behaviors and self-perception in the real world (Figure 1) (30). The intervention was designed to employ the tenets of self-determination theory which posits that competence, autonomy, and relatedness motivate behavioral change (31). Prior proof-of-concept and pilot studies have demonstrated acceptability, feasibility, excellent participation and adherence rates, and high user satisfaction of the VWCR intervention (32, 33). The pilot study additionally demonstrated a trend toward improvements in cardiovascular health (CVH) behaviors (33). Participant feedback from the two prior studies have been used to refine the platform to better meet patients' needs. To validate Destination Cardiac Rehab as a viable alternative to traditional CBCR, our study team plans to conduct a randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing participation and adherence rates and clinical outcomes in patients participating in Destination Cardiac Rehab vs. traditional CBCR (34).

Figure 1. Theoretical framework for destination cardiac rehab. Created with BioRender.com. Bottom left image: Reproduced with permission from “Senior African American couple using laptop” by Monkey Business Images, licensed under Standard Image License. Right image: Reproduced with permission from “Motion blur shot of an African American mother and daughter jogging together in park” by sirtravelalot, licensed under Standard Image License.

Context

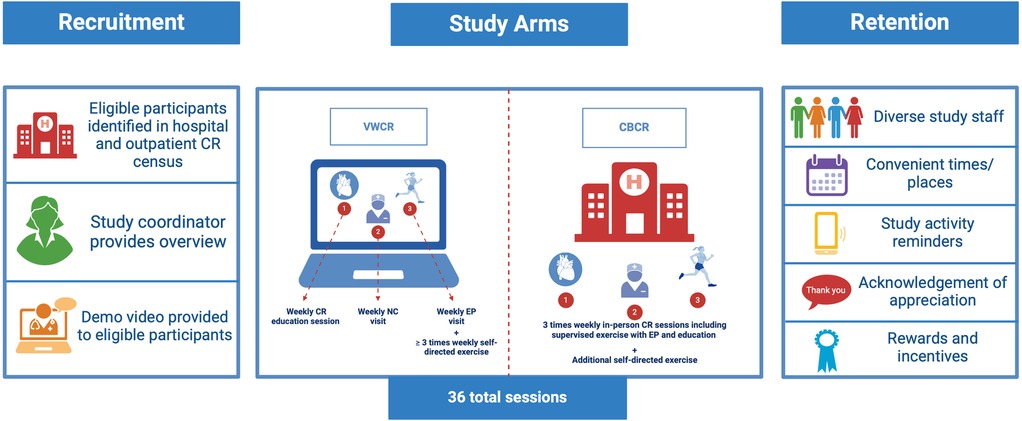

The upcoming RCT will recruit patients from six study sites (three Mayo Clinic sites: Rochester, MN, Phoenix, AZ, and Jacksonville, FL; Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD; University of California, Irvine, CA; and University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS). Figure 2 provides an overview of the intervention, recruitment/retention strategies and a side-by-side comparison of CBCR vs. VWCR. Eligible participants will be identified by the study coordinators both in the inpatient setting from the hospital service census and outpatient CR enrollment lists. Once eligibility is confirmed, potential participants will be approached and provided with an overview of the study and demo video. Participants who consent to enrollment will be randomized to either the CBCR (control group) or Destination Cardiac Rehab (intervention group). A detailed description of the RCT protocol was previously published (34).

Figure 2. Overview of trial protocol including overview of intervention and control arms. Created with BioRender.com.

Briefly, participants in both groups will undergo an initial health assessment (e.g., clinical measures, laboratory studies, etc.) and form an individualized treatment plan (ITP) which will include relevant clinical history, exercise program description, risk factor modification plan, and psychosocial assessment. Participants randomized to the control group will participate in a standard, in-person, 36-session CBCR program over 12 weeks (3 sessions/week). Participants in the VWCR group will also engage in 3 virtual CR sessions per week over 12 weeks (total 36 sessions) including education sessions within the VW platform. The education session topics were previously published in the RCT protocol (34). Virtual visits with a nurse coach (NC) to review key concepts from the education sessions, CV symptoms, vital signs, and medications, and virtual visits with an exercise physiologist (EP) to review physical activity (PA) patterns and to receive a personalized exercise prescription. They may also attend an optional weekly peer-support group designed to mimic the social support experienced in an in-person environment. Participants in both groups will be encouraged to exercise on their own outside of the 3 standard exercise sessions per week.

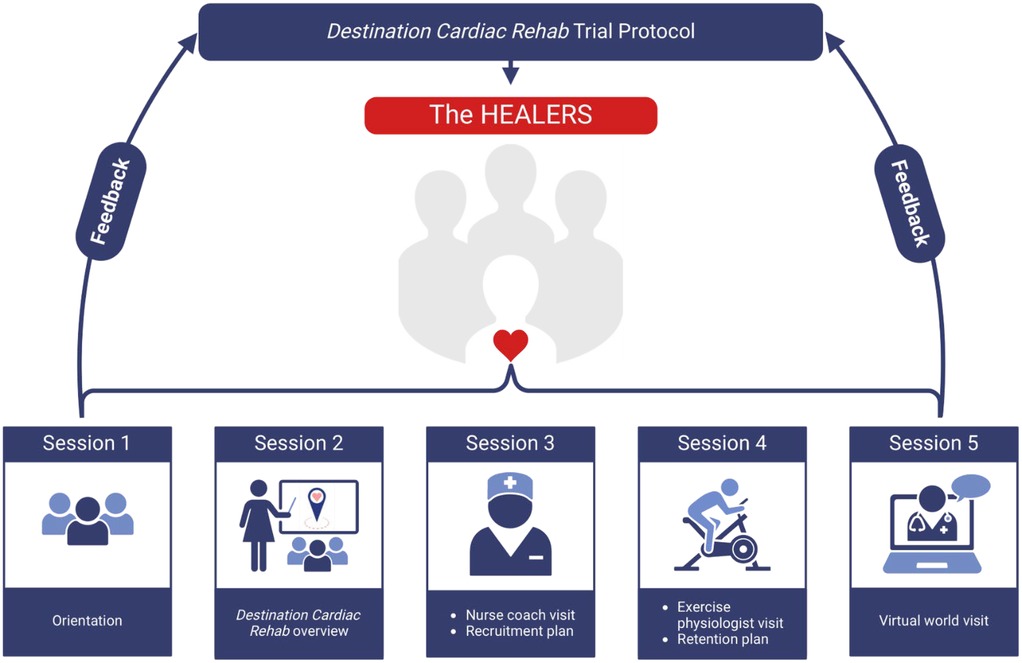

Prior to commencement of the RCT, a patient/community/stakeholder advisory board (PCS-AB), self-dubbed the HEALERS (Heart Empowerment and Advisory for Life Enhancement in Cardiac Rehab Settings), was convened to further develop and refine the RCT recruitment strategy, Destination Cardiac Rehab intervention/platform, and retention strategy to better meet the needs of patients. As a part of the theoretical framework for CER, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Engagement Rubric was utilized in the RCT planning phase. This rubric focuses on four principles: reciprocal relationships, partnerships, co-learning, and transparency to optimize meaningful patient and stakeholder involvement (35). The HEALERS will continue to meet quarterly throughout the 5-year trial to inform both the study conducting phase and disseminating the study results.

This qualitative descriptive analysis of a focus group (FG) series aims to: (1) describe the methods for recruiting the HEALERS, (2) outline the series structure, (3) and detail a pragmatic approach to the systemic analysis of feedback obtained during the series to inform iterative refinements and enhancements to Destination Cardiac Rehab and the forthcoming clinical trial recruitment and retention strategies (36).

Methods

Advisory board recruitment

The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved this study. The study team employed both purposeful and convenience sampling strategies to recruit patients from each of the six study sites who were previously eligible for or participated in CR programs in addition to caregivers and relevant administrators/stakeholders with expertise in CR administration to ensure a diverse group that represents the population of interest, in accordance with the PCORI Engagement Rubric. Eligibility criteria were the following: patients who were eligible for CR who completed CR, enrolled in but did not complete CR, and those who did not enroll in CR, caregivers of patients who were eligible for CR, and representatives from key stakeholder/advocacy groups (e.g., American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, American Heart Association, Mayo Clinic Information Technology, and CR payers), age ≥18 years old, basic internet navigation skills, and an active email address.

Recruitment flyers with study team contact information and a detailed description of the advisory board purpose and activities were distributed to all six participating sites to recruit representation from diverse geographic locations. The flyers were displayed at the CR center of each site and distributed by CR staff to interested past and current patients. Patients, caregivers and stakeholders interested in participating voluntarily reached out to the study team contact and were screened for eligibility. Additionally, Mayo Clinic patients who had been referred to CR were screened for eligibility and approached by study team members with whom they had no prior relationship via phone, secure patient portal message, or email. Coercion was prevented as the recruitment materials were shared with anyone at the CR site, rather than approaching specific individuals. To further minimize coercion, any interested individuals were required to contact the study team on their own. Interested CR patients, caregivers and stakeholders contacted the study team by phone or email to confirm their interest and ability to complete all expected advisory board activities. Following eligibility screening conducted by the study coordinator via phone call, informed consent and HIPAA authorization forms were sent electronically. A Mayo Clinic approved process for documenting informed consent and HIPAA authorization was completed and enrolled participants were provided copies of the signed forms.

Data collection

After advisory board recruitment was finalized, five 90-minute virtual FG sessions occurred monthly via videoconferencing (Zoom©). The FG moderator guides and agendas were informed by the PCORI Engagement Rubric to prioritize patient centeredness and facilitate actionable feedback from participants during the RCT planning phase (35). FG sessions included a short slide presentation in which study team members with training and experience in facilitation of focus groups (A.K. and L.B.) presented various aspects of the intervention and recruitment/retention plans. Topics presented during each FG are detailed below. Feedback was elicited from the HEALERS throughout and at the conclusion of each FG via open-ended questions. VW specialists were available for questions specific to the VW platform. FGs were audio and video-recorded and field notes were made by the facilitators during the FGs. See Figure 3 for an overview of the FGs. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist was utilized to ensure comprehensive reporting of the methodology and findings (37).

Figure 3. Study overview with a brief description of the FG session topics. Created with BioRender.com.

The HEALERS were provided with access to the Destination Cardiac Rehab platform within Second Life® and created individual avatars. They explored the VW platform individually and also met as a group on the platform during session 5 (detailed below).

Focus group session 1

The initial session oriented members to the study team and the VWCR intervention. The study team and the HEALERS participants introduced themselves and described their motivations for the research project and joining the advisory board respectively. Based on the PCORI engagement principles “reciprocal relationships” and “partnerships”, the group set ground rules for the meetings, proposed a meeting schedule, and discussed general expectations and goals. A commitment was made to open and honest communication. The study team described Destination Cardiac Rehab and the VW platform in detail.

Focus group session 2

The HEALERS were presented with an overview of the disparities in CR participation and aims of the VWCR RCT. The components of the VWCR intervention were reviewed again in detail including the planned education session topics. Lastly, the group was shown 20 Destination Cardiac Rehab logo designs and voted via an online poll to determine the final logo (previously published 32) which will be included on all study materials.

Focus group session 3

Members were provided with a glimpse into the patient experience of an NC visit. An NC presented the components of the NC visits including a detailed review of the ITP and physical and mental/emotional health screenings. One of the study team members (A.K.) and the NC performed a mock NC visit through role play. Additionally, the plan for recruiting participants was reviewed with the HEALERS. The group watched two CBCR program video recruitment examples from partnering sites and collaborators. The HEALERS provided feedback regarding the NC visits, recruitment strategy overview, and recruitment videos.

Focus group session 4

Guest EPs detailed the components of an EP visit including development/refinement of a home-based exercise prescription and review of the ITP, adherence to the exercise plan, new/concerning symptoms, and concepts from the VWCR curriculum. The two EPs demonstrated a typical EP visit. The study team also presented the retention strategy which includes assembling a diverse study staff, offering high-quality services such as convenient assessment times/places, sending study activity reminders via preferred contact method, acknowledging and appreciating participants, and providing motivational rewards and incentives as detailed in Figure 2.

Focus group session 5

The PCS-AB members provided final feedback regarding the trial plan via videoconferencing. The group then moved to the Destination Cardiac Rehab platform where the members provided real-time feedback on the VWCR features while navigating throughout the platform with the study team.

Data analysis

The study team reviewed the recordings and the participant feedback portions of the recordings were transcribed for data analysis. Participant identifiers were removed and replaced with a random number. Two study team members (H.A. and G.A.) independently read the transcripts multiple times for familiarization. A coding framework with predefined codes based on the research objectives – recruitment, intervention, and retention strategies – guided the initial analysis. Following this, an inductive approach, which involves gathering participants' insights and experiences, without predefined categories to allow themes to emerge naturally from discussion, was used to facilitate an open discussion probing participants' experiences (38, 39). The agenda evolved as insights arose from the discussion. Themes and subthemes were analyzed within each FG and compared across sessions to identify recurring patterns by content analysis (38–40). Illustrative quotes were selected to contextualize the major themes identified. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion with the study principal investigator (L.B.) until consensus was reached. Key themes and insights were analyzed to identify actionable insights to inform further refinement of the trial protocol.

Results

Participants

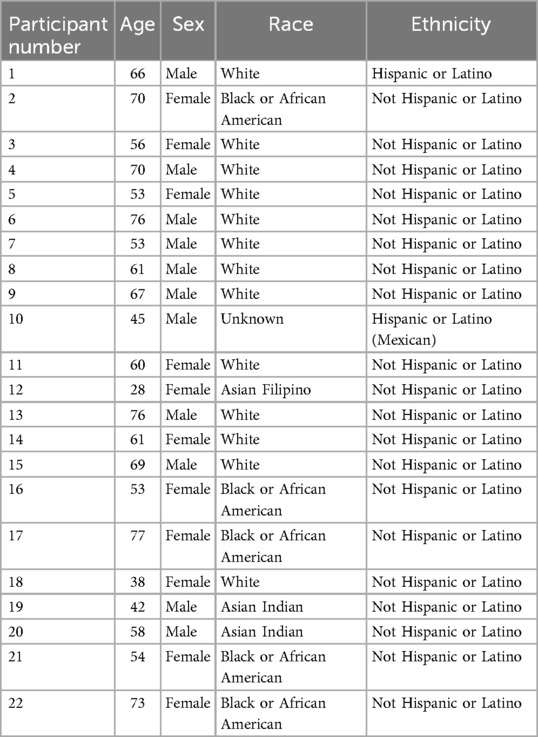

The HEALERS advisory board included 22 members with representatives from all six study-sites. There was 100% retention rate with no members dropping out. Members had a mean age of 59.3 ± 13 years (range 28–77 years) and 50% self-identified as women. The group includes members from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds with 59% of participants self-identifying as White, 23% Black or African American, 9% Asian Indian, 4% Asian Filipino, 9% Hispanic or Latino, and 4% did not report. Randomly assigned participant numbers and associated demographic information are listed in Table 1. The majority of members were patients who previously completed a CBCR program for a variety of indications including acute coronary syndrome (e.g., myocardial infarction) [n = 5], coronary artery bypass surgery [n = 1], heart failure [n = 1], heart transplant [n = 3], and percutaneous coronary intervention [n = 1]). Seven members were patients who did not disclose their CR indication. The remaining members in addition to some of the patients described diverse work and personal experiences including work in healthcare through direct patient care, CR administration, clinical research, information technology, hospital volunteering, and support organizations for patients with heart disease.

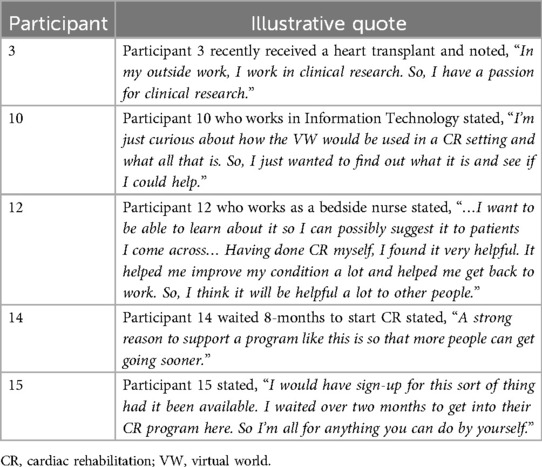

Motivations for joining the HEALERS

Members cited a variety of motivations for joining the HEALERS. Several members expressed a desire to help those undergoing similar experiences to their own and paving a smoother path for others. Several participants experienced a long waiting period for CR availability and hoped programs like Destination Cardiac Rehab can provide more expedient care. Others felt a need to give back to the healthcare community in appreciation for the care received after their cardiac event. Many members joined due to a personal curiosity and interest in the intervention. Lastly, participants who work in CR administration and work with support group organizations joined to share their unique perspectives simply to assist in the development of an alternative CR program. Illustrative quotes are listed by participant in Table 2.

Destination Cardiac Rehab logo

The HEALERS voted on a logo via online poll to represent Destination Cardiac Rehab. The logo depicted in Figure 4 was chosen by popular vote.

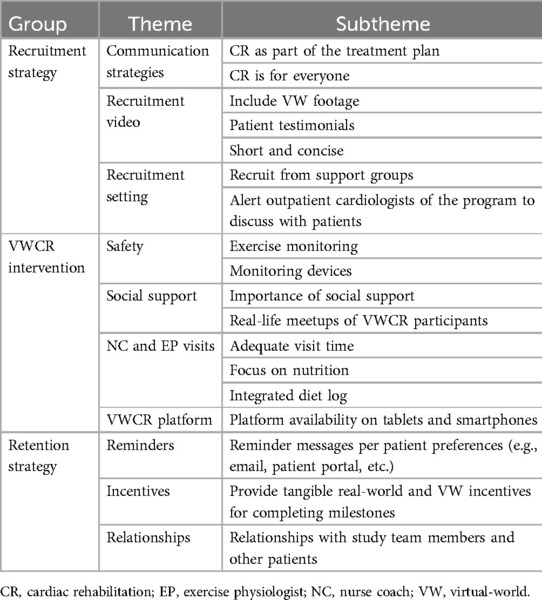

Findings

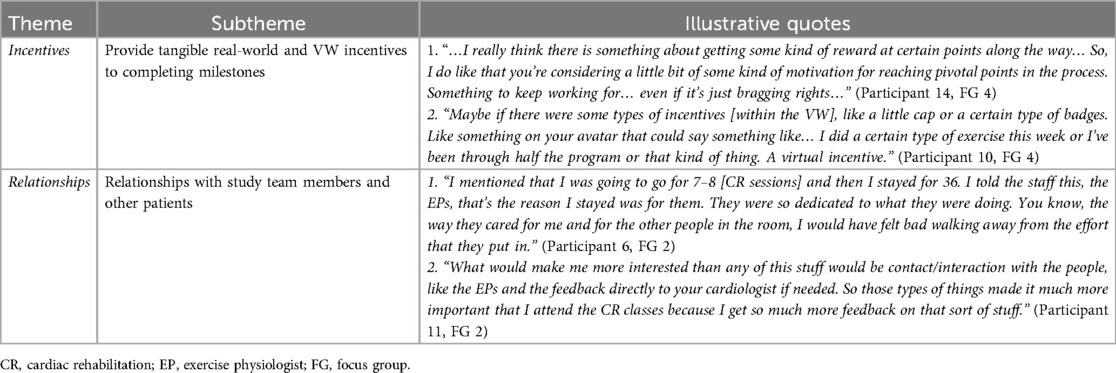

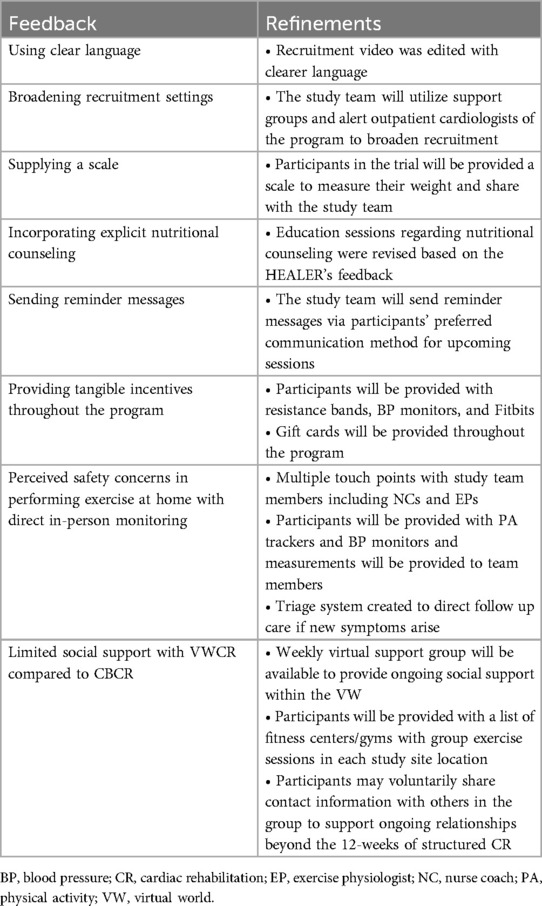

Major themes were identified and categorized into groups: recruitment strategy, VWCR intervention and platform, and retention strategy. Themes and subthemes are summarized in Table 3 and illustrative quotes for each subtheme in Tables 4–6.

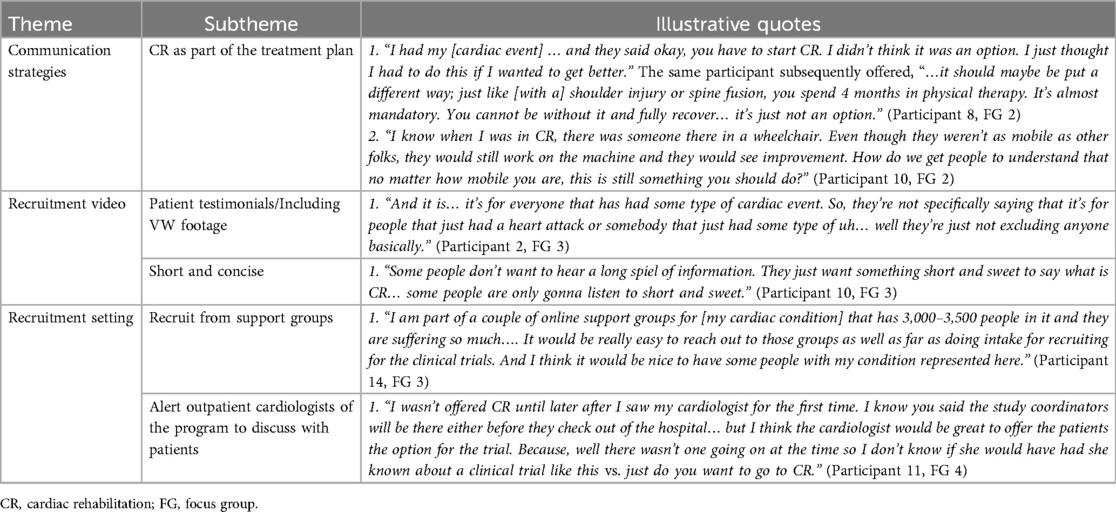

Recruitment strategy

Communication strategies

Participants discussed the impact of the communication strategies utilized in their CBCR recruitment experiences and how those strategies impacted their decisions to enroll. Participants noted that their care teams conveyed CR as a mandatory component of their care plan which motivated them to participate. They recommended conveying that CR is necessary regardless of baseline physical functioning. Based on these observations, the group agreed that the study overview and recruitment videos should (1) endorse CR as an essential part of the treatment plan and (2) emphasize its use in all patients regardless of physical functioning.

Recruitment video

Based on the two recruitment videos shown, participants preferred the shorter video. Participant 10 suggested using footage from the VWCR platform and including prior patient testimonials. Participant 10 also pointed out that one of the videos stated that CR is for everyone with cardiac diseases and not just those who had heart attacks and emphasized that the recruitment video should highlight this.

Recruitment setting

In addition to recruiting patients during their index hospitalization and from the outpatient CR census list, participants recommended additional recruitment settings. For example, Participant 14 recommended recruitment from support groups for patients with rare cardiac conditions. Additionally, Participant 11 recommended alerting outpatient cardiologists of the trial to expand recruitment.

VWCR intervention

Safety

Several participants across multiple FGs expressed low confidence in exercise capacity and exercise safety after their cardiac event and the need to be monitored during exercise to regain that confidence. The participants stressed the need for a similar mechanism for real-time symptom reporting to ensure exercise safety and rebuild confidence. In addition to the PA tracker and blood pressure (BP) monitor, Participant 8 suggested including an accurate scale so that participants can report daily weights to the study team to alert the team of early decompensated heart failure.

Social support

In addition to ensuring adequate real-time exercise monitoring, participants emphasized the importance of the social support garnered in CBCR. Participant 17 recommended that the study team compile a list of community resources that offer group exercise to simulate this experience. Other participants echoed this suggestion. Additionally, Participants 1 and 9 shared that they met during CBCR and continue to exercise together 3-times per week. Participant 1 highlighted the importance of this relationship for maintaining accountability. Based on this feedback, the participants suggested providing a mechanism for patients in the VWCR group to share their contact information to allow those in close proximity to establish similar relationships.

NC and EP visits

Participants emphasized the importance of allotting adequate visit time to ensure the patients are being heard. Additionally, multiple participants expressed that their CR programs provided vague nutrition recommendations and suggested that one of the NC visits focus on nutrition with clearer guidance. Participant 10 pointed out that there is a built-in diet log within the PA tracker that may be useful to review during NC visits. Other participants reported that their CBCR programs included a nutritionist and/or provided links to a video that provided specific nutrition recommendations, which they suggested may be viable alternatives to including detailed nutrition advice during NC visits.

VWCR platform

The advisory board members gave very positive feedback regarding the VWCR platform and had few recommendations for revision. Participant 8 asked whether the VWCR platform could be made available on tablets/smartphones.

Retention strategy

Reminders and incentives

Several participants endorsed receiving text messages and portal messages during CBCR, which they found helpful. They did not have any additional suggestions to add to the current plan. They did stress the importance of incentive materials in motivating participants. Participant 14 suggested commemorative rewards (such as T-shirts, coffee mugs, etc.) when reaching milestones. Participant 10 suggested including rewards within the VWCR platform such as caps or badges the avatars could wear.

Relationships

Multiple participants noted that the relationships formed during CR was the most important factor that motivated them to persevere. They mentioned a sense of accountability to the CR staff in addition to their peers in the CR program. This accountability not only motivated them to complete all 36 CR sessions but also continue healthy lifestyle changes beyond the CR program.

Discussion

Utilizing CER methods, we successfully recruited a diverse PCS-AB and conducted five FGs to inform iterative refinements to Destination Cardiac Rehab and the recruitment/retention strategies for an upcoming RCT which will compare adherence and efficacy of this novel intervention to traditional CBCR (41, 42). The HEALERS offered important actionable insights, recommendations, and concerns that the study team analyzed to inform changes to Destination Cardiac Rehab and the trial protocol to better meet patients' needs. In addition to a growing body of literature regarding CER, our findings highlight the immense value in including patients, community members, and key stakeholders in the design process of novel interventions to better understand what is important to patients and how to best meet their needs (2). Refinements to the Destination Cardiac Rehab RCT protocol made based on the HEALER's feedback are detailed in Table 7.

Many recommendations by the HEALERS can be readily implemented into the existing protocol including: using clear language, broadening recruitment settings, supplying a scale, incorporating explicit nutritional counseling, sending reminder messages, and providing tangible incentives throughout the program. Two major concerns raised throughout the sessions were (1) perceived safety concerns in performing exercise at home without direct in-person monitoring and (2) limited social support with VWCR compared to CBCR. These issues require multifaceted solutions, as discussed below, to best simulate the positive aspects of the CBCR experiences described by the HEALERS that are inherently absent in VWCR and mitigate any impact their absence may have on patient motivation/adherence.

HEALERS members that previously participated in CBCR reported that in-person exercise monitoring in their CBCR programs offered a sense of security that bolstered their confidence and motivated them to persevere. Despite sufficient literature to support the safety of alternative CR programs without direct exercise supervision in low- to moderate-risk patients, they worry that the absence of that perceived security may hinder progression of exercise goals (23, 43). While our prior proof-of-concept and pilot studies demonstrated excellent adherence, participants simultaneously participated in CBCR. Thus, the safety concerns highlighted by the HEALERS were not present in our prior studies (33). However, prior studies directly comparing HBCR and CBCR suggest that the absence of direct supervision during exercise in HBCR does not negatively impact participation rates or improvement in functional capacity (23, 44). According to Velez et al. within a systematic review of qualitative analyses of telerehabilitation programs, patients that participated in telerehabilitation programs reported a sense of empowerment to take ownership of their own rehabilitation journey which facilitated achievement of their health and lifestyle goals (45, 46). Nevertheless, we acknowledge the concern raised by the HEALERS and have included multiple mechanisms to alleviate potential feelings of unease. Although the nature of our intervention precludes direct supervision of exercise, our intervention includes multiple touch points with study staff in which patients can share new symptoms or other concerns they may have during exercise. Additionally, patients will be provided with PA trackers which will monitor heart rate during exercise. Patients will also be equipped with BP monitors and encouraged to take BP measurements prior to and following independent exercise for review with the EP and NC at weekly visits. The EPs will discuss in detail normal symptoms during exercise and symptoms that should raise an alarm and compel the patient to discontinue exercise and/or present to urgent medical attention. Lastly, there is a triage system in place to direct follow up-care if new symptoms arise. Based on prior studies and these planned safeguards, we expect that patients will persevere in the absence of direct exercise supervision.

The HEALERS also mentioned on several occasions that the social support/network and relationships they built during CBCR motivated them to maintain behavioral change during their structured CR programs and beyond. Several participants continue to exercise regularly with people they met in CR and expressed concern that this may not be possible for patients who participate in Destination Cardiac Rehab. This sentiment is supported by multiple studies which show that the absence of in-person social interactions negatively impacted patients' rehabilitation experiences (45, 47, 48). Destination Cardiac Rehab has many unique features designed to address the highly important social support aspect of CR that is often missing in HBCR programs. Most notably, Destination Cardiac Rehab capitalizes on simulating in-person experiences via a virtual platform. Additionally, the weekly virtual peer support group meetings which were specifically designed to foster relationships among patients have been shown in our prior studies to be very effective in garnering social support (32, 33, 49). The patients will also have very frequent touch points with the VWCR staff via videoconferencing (equivalent to those participating in CBCR) which we expect to cultivate similar relationships with CR staff as those described by members of the HEALERS. In response to feedback by the advisory board, we will compile a list of fitness centers/gyms with group exercise sessions in each study site location for those who seek in-person group exercise experiences. We will also offer a mechanism for patients to voluntarily share contact information with others in the group to support ongoing relationships beyond the 12-weeks of structured CR.

Overall, the group shared their personal experiences, viewpoints, and opinions to ensure that patients with similar perspectives who will ultimately benefit from Destination Cardiac Rehab are represented in its design and implementation. The HEALERS will continue to meet throughout the RCT to inform implementation and dissemination strategies.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, the PCS-AB members are relatively young (average age 59 years-old) and older individuals with more barriers to technological interventions may be underrepresented (50). An inherent limitation in focus groups is potential imbalances among the group in assertiveness and openness to share their experiences, some participants' perspectives may be disproportionately represented. While some participants were less assertive or open, all of the members participated in the discussion. Lastly, the study team was unable to recruit participants who have been candidates for CR but did not participate. Most of the members who had previously participated in CBCR participated in the majority of CBCR sessions and may not represent individuals with greater barriers to CR participation. Nevertheless, they offered valuable insight into their own CR experiences and the aspects of their programs that fostered motivation and perseverance.

Conclusion

The HEALERS, a community advisory board comprised of patients, community members, and key stakeholders was successfully convened and FG sessions were held to collaborate with the Destination Cardiac Rehab study team to offer insights to inform improvements to the intervention and implementation plans in anticipation of a patient and community-centric RCT. The HEALERS recommended using clear language, broadening recruitment settings, supplying a weight scale, incorporating explicit nutritional counseling, sending reminder messages, and providing tangible incentives throughout the program. They also noted two very important concerns: (1) perceived safety concerns in performing exercise at home without direct in-person monitoring and (2) limited social support with VWCR compared to CBCR and potential solutions to address these concerns. Our study highlights the value of CER approaches in garnering community member feedback to ensure representation of diverse perspectives in the design and implementation of a novel intervention.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Mayo Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

HA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation. GA-A: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation. AK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation. DC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. ME: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. MH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. KH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. BK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. SK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. SL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. SM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. JM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. LM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. RS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. PS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation. AS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. JB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. BT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. RT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. NW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. TO: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Investigation. LB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study is supported by the Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation and the American Heart Association Second Century Implementation Science Award (grant 23SCISA1144689). Dr. Brewer was also supported by the American Heart Association–Amos Medical Faculty Development Program (grant 19AMFDP35040005), the Robert A. Winn Career Development Award (Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation), the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (grant P50MD017342), the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (grant UL1 TR000135) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) to Mayo Clinic, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; grant CDC- DP18-1817) during the implementation of this work. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCATS, NIH, or CDC. The funding bodies had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Ms. Anyetei-Anum received funding from the American Heart Association through the Research Supplement to Promote Diversity in Science (grant 24DIVSUP1262541).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the members of the HEALERS for contributing to the refinement of the trial protocol and intervention.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

BP, blood pressure; CER, community-engaged research; CR, cardiac rehabilitation; CVH, cardiovascular health; EP, exercise physiologist; FG, focus group; HBCR, home-based cardiac rehabilitation; NC, nurse coach; PA, physical activity; PCORI, Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute; PCS-AB, patient, caregiver, stakeholder advisory board; SES, socioeconomic status; RCT, randomized controlled trial; VW, VIRTUAL world; VWCR, virtual world-based cardiac rehabilitation.

References

1. Haynes N, Kaur A, Swain J, Joseph JJ, Brewer LC. Community-based participatory research to improve cardiovascular health among us racial and ethnic minority groups. Curr Epidemiol Rep. (2022) 9(3):212–21. doi: 10.1007/s40471-022-00298-5

2. Wieland ML, Njeru JW, Alahdab F, Doubeni CA, Sia IG. Community-engaged approaches for minority recruitment into clinical research: a scoping review of the literature. Mayo Clin Proc. (2021) 96(3):733–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.03.028

3. Thomas VE, Metlock FE, Hines AL, Commodore-Mensah Y, Brewer LC. Community-based interventions to address disparities in cardiometabolic diseases among minoritized racial and ethnic groups. Curr Atheroscler Rep. (2023) 25(8):467–77. doi: 10.1007/s11883-023-01119-w

4. Brewer LC, Cyriac J, Kumbamu A, Burke LE, Jenkins S, Hayes SN, et al. Sign of the times: community engagement to refine a cardiovascular mHealth intervention through a virtual focus group series during the COVID-19 pandemic. Digit Health. (2022) 8:20552076221110537. doi: 10.1177/20552076221110537

5. Adedinsewo D, Eberly L, Sokumbi O, Rodriguez JA, Patten CA, Brewer LC. Health disparities, clinical trials, and the digital divide. Mayo Clin Proc. (2023) 98(12):1875–87. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.05.003

6. Knott CL, McCullers A, Woodard N, Aldana V, Williams BR, Clark EM, et al. Community engagement to inform multilevel analyses of the role of neighborhood factors in cancer control behaviors in African Americans. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2025) 34(4):500–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-24-1118

7. Adegboyega A, Francis DB, Ebikwo C, Ntego T, Ickes M. Engagement with a youth community advisory board to develop and refine a Facebook HPV vaccination promotion intervention (#HPVvaxtalks) for young black adults (18–26 years old). Health Promot Pract. (2025) 26(2):209–12. doi: 10.1177/15248399231216731

8. Smith MY, Janssens R, Jimenez-Moreno AC, Cleemput I, Muller M, Oliveri S, et al. Patients as research partners in preference studies: learnings from IMI-PREFER. Res Involv Engagem. (2023) 9(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s40900-023-00430-9

9. Carman KL, Workman TA. Engaging patients and consumers in research evidence: applying the conceptual model of patient and family engagement. Patient Educ Couns. (2017) 100(1):25–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.009

10. Forsythe LP, Carman KL, Szydlowski V, Fayish L, Davidson L, Hickam DH, et al. Patient engagement in research: early findings from the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Health Aff (Millwood). (2019) 38(3):359–67. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05067

11. Crocker JC, Ricci-Cabello I, Parker A, Hirst JA, Chant A, Petit-Zeman S, et al. Impact of patient and public involvement on enrolment and retention in clinical trials: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br Med J. (2018) 363:k4738. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4738

12. Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, Wang Z, Nabhan M, Shippee N, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. (2014) 14:89. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-89

13. Ritchey MD, Maresh S, McNeely J, Shaffer T, Jackson SL, Keteyian SJ, et al. Tracking cardiac rehabilitation participation and completion among medicare beneficiaries to inform the efforts of a national initiative. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. (2020) 13(1):e005902. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005902

14. Thomas RJ, Balady G, Banka G, Beckie TM, Chiu J, Gokak S, et al. 2018 ACC/AHA clinical performance and quality measures for cardiac rehabilitation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on performance measures. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2018) 71(16):1814–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.01.004

15. Bakhshayeh S, Sarbaz M, Kimiafar K, Vakilian F, Eslami S. Barriers to participation in center-based cardiac rehabilitation programs and patients’ attitude toward home-based cardiac rehabilitation programs. Physiother Theory Pract. (2021) 37(1):158–68. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2019.1620388

16. Foster EJ, Munoz SA, Crabtree D, Leslie SJ, Gorely T. Barriers and facilitators to participating in cardiac rehabilitation and physical activity in a remote and rural population: a cross-sectional survey. Cardiol J. (2021) 28(5):697–706. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2019.0091

17. Supervía M, Medina-Inojosa JR, Yeung C, Lopez-Jimenez F, Squires RW, Pérez-Terzic CM, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation for women: a systematic review of barriers and solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. (2017) S0025-6196(17):30026–5. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.01.002

18. Thomas RJ. Cardiac rehabilitation—challenges, advances, and the road ahead. N Engl J Med. (2024) 390(9):830–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2302291

19. Brown TM, Pack QR, Beregg EA, Brewer LC, Ford YR, Forman DE, et al. Core components of cardiac rehabilitation programs: 2024 update: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American association of cardiovascular and pulmonary rehabilitation: endorsed by the American College of Cardiology. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. (2025) 45(2):E6–E25. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000930

20. Castellanos LR, Viramontes O, Bains NK, Zepeda IA. Disparities in cardiac rehabilitation among individuals from racial and ethnic groups and rural communities-A systematic review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. (2019) 6(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s40615-018-0478-x

21. Mathews L, Brewer LC. A review of disparities in cardiac rehabilitation: EVIDENCE, DRIVERS, AND SOLUTIONS. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. (2021) 41(6):375–82. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000659

22. Khadanga S, Gaalema DE, Savage P, Ades PA. Underutilization of cardiac rehabilitation in women: BARRIERS AND SOLUTIONS. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. (2021) 41(4):207–13. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000629

23. Thomas RJ, Beatty AL, Beckie TM, Brewer LC, Brown TM, Forman DE, et al. Home-based cardiac rehabilitation: a scientific statement from the American association of cardiovascular and pulmonary rehabilitation, the American Heart Association, and the American College of Cardiology. Circulation. (2019) 140(1):e69–89. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000663

24. Beatty AL, Beckie TM, Dodson J, Goldstein CM, Hughes JW, Kraus WE, et al. A new era in cardiac rehabilitation delivery: research gaps, questions, strategies, and priorities. Circulation. (2023) 147(3):254–66. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.061046

25. Shanmugasegaram S, Oh P, Reid RD, McCumber T, Grace SL. A comparison of barriers to use of home- versus site-based cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. (2013) 33(5):297–302. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e31829b6e81

26. Thomas R, Scales R, Fernandes R. Alternative models to facilitate and improve delivery of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention. In: Rippe JM, editor. Lifestyle Medicine. 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press (2019). p. 833–7.

27. Widmer RJ, Collins NM, Collins CS, West CP, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Digital health interventions for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. (2015) 90(4):469–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.12.026

28. Lee KCS, Breznen B, Ukhova A, Koehler F, Martin SS. Virtual healthcare solutions for cardiac rehabilitation: a literature review. Eur Heart J Digit Health. (2023) 4(2):99–111. doi: 10.1093/ehjdh/ztad005

29. Brewer LC, Kaihoi B, Zarling KK, Squires RW, Thomas R, Kopecky S. The use of virtual world-based cardiac rehabilitation to encourage healthy lifestyle choices among cardiac patients: intervention development and pilot study protocol. JMIR Res Protoc. (2015) 4(2):e39. doi: 10.2196/resprot.4285

30. Liu J, Burkhardt JM, Lubart T. Boosting creativity through users’ avatars and contexts in virtual environments-a systematic review of recent research. J Intell. (2023) 11(7):144. doi: 10.3390/jintelligence11070144

31. Bandhu D, Mohan MM, Nittala NAP, Jadhav P, Bhadauria A, Saxena KK. Theories of motivation: a comprehensive analysis of human behavior drivers. Acta Psychol (Amst). (2024) 244:104177. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104177

32. Brewer LC, Kaihoi B, Schaepe K, Zarling K, Squires RW, Thomas RJ, et al. Patient-perceived acceptability of a virtual world-based cardiac rehabilitation program. Digit Health. (2017) 3:2055207617705548. doi: 10.1177/2055207617705548

33. Brewer LC, Abraham H, Kaihoi B, Leth S, Egginton J, Slusser J, et al. A community-informed virtual world-based cardiac rehabilitation program as an extension of center-based cardiac rehabilitation: MIXED-METHODS ANALYSIS OF A MULTICENTER PILOT STUDY. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. (2023) 43(1):22–30. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000705

34. Brewer LC, Abraham H, Clark D 3rd, Echols M, Hall M, Hodgman K, et al. Efficacy and adherence rates of a novel community-informed virtual world-based cardiac rehabilitation program: protocol for the destination cardiac rehab randomized controlled trial. J Am Heart Assoc. (2023) 12(23):e030883. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.123.030883

35. Sheridan S, Schrandt S, Forsythe L, Hilliard TS, Paez KA, Advisory Panel on Patient Engagement (2013 inaugural panel). The PCORI engagement rubric: promising practices for partnering in research. Ann Fam Med. (2017) 15(2):165–70. doi: 10.1370/afm.2042

36. Ramanadhan S, Revette AC, Lee RM, Aveling EL. Pragmatic approaches to analyzing qualitative data for implementation science: an introduction. Implement Sci Commun. (2021) 2(1):70. doi: 10.1186/s43058-021-00174-1

37. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. (2007) 19(6):349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

38. Neuendorf KA. The Content Analysis Guidebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc (2017).

39. Giacomini M, Dingwall R, De Vries R, Bourgeault I. Theory matters in qualitative health research. In: Bourgeault R, editor. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Methods in Health Research. London: SAGE Publications Ltd (2010). p. 125–56.

40. Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc (2019).

41. Wells K, Jones L. “Research” in community-partnered, participatory research. JAMA. (2009) 302(3):320–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1033

42. Newman SD, Andrews JO, Magwood GS, Jenkins C, Cox MJ, Williamson DC. Community advisory boards in community-based participatory research: a synthesis of best processes. Prev Chronic Dis. (2011) 8(3):A70.21477510

43. Stefanakis M, Batalik L, Antoniou V, Pepera G. Safety of home-based cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review. Heart Lung. (2022) 55:117–26. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2022.04.016

44. Taylor RS, Dalal H, Jolly K, Zawada A, Dean SG, Cowie A, et al. Home-based versus centre-based cardiac rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2015) 8:Cd007130. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007130.pub3

45. Velez M, Lugo-Agudelo LH, Patiño Lugo DF, Glenton C, Posada AM, Mesa Franco LF, et al. Factors that influence the provision of home-based rehabilitation services for people needing rehabilitation: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2023) 2(2):Cd014823. doi: 10.1002/14651858.Cd014823

46. Ranaldi H, Deighan C, Taylor L. Exploring patient-reported outcomes of home-based cardiac rehabilitation in relation to Scottish, UK and European guidelines: an audit using qualitative methods. BMJ Open. (2018) 8(12):e024499. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024499

47. O’Shea O, Woods C, McDermott L, Buys R, Cornelis N, Claes J, et al. A qualitative exploration of cardiovascular disease patients’ views and experiences with an eHealth cardiac rehabilitation intervention: the PATHway project. PLoS One. (2020) 15(7):e0235274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235274

48. Dinesen B, Spindler H. The use of telerehabilitation technologies for cardiac patients to improve rehabilitation activities and unify organizations: qualitative study. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol. (2018) 5(2):e10758. doi: 10.2196/10758

49. Content VG, Abraham HM, Kaihoi BH, Olson TP, Brewer LC. Novel virtual world-based cardiac rehabilitation program to broaden access to underserved populations: a patient perspective. JACC Case Rep. (2022) 4(14):911–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2022.05.027

Keywords: cardiac rehabilitation, telehealth, virtual world, community engaged research, healthcare equity patient, caregiver, stakeholder advisory board

Citation: Abraham H, Anyetei-Anum GP, Krogman A, Clark III D, Echols M, Hall ME, Hodgman K, Kaihoi B, Kopecky S, Leth S, Malik S, Marsteller J, Mathews L, Scales R, Schulte P, Shultz A, Becker J, Taylor B, Thomas R, Wong ND, Olson T and Brewer LC (2025) The HEALERS: a patient, community, and stakeholder advisory board focus group series to refine a novel virtual world-based cardiac rehabilitation intervention and clinical trial. Front. Digit. Health 7:1427539. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2025.1427539

Received: 21 June 2024; Accepted: 12 May 2025;

Published: 15 July 2025.

Edited by:

Mohamed-Amine Choukou, University of Manitoba, CanadaReviewed by:

Jennifer Sumner, Alexandra Hospital, SingaporeMayson Sousa, University of Manitoba, Canada

Copyright: © 2025 Abraham, Anyetei-Anum, Krogman, Clark, Echols, Hall, Hodgman, Kaihoi, Kopecky, Leth, Malik, Marsteller, Mathews, Scales, Schulte, Shultz, Becker, Taylor, Thomas, Wong, Olson and Brewer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: LaPrincess C. Brewer, YnJld2VyLmxhcHJpbmNlc3NAbWF5by5lZHU=

Helayna Abraham

Helayna Abraham Grace Patrice Anyetei-Anum2

Grace Patrice Anyetei-Anum2 Melvin Echols

Melvin Echols Shaista Malik

Shaista Malik Robert Scales

Robert Scales Phillip Schulte

Phillip Schulte Bryan Taylor

Bryan Taylor Randal Thomas

Randal Thomas Nathan D. Wong

Nathan D. Wong Thomas Olson

Thomas Olson LaPrincess C. Brewer

LaPrincess C. Brewer