Abstract

Objective:

To synthesize qualitative evidence, using the framework analysis method, on how participating in a digital storytelling workshop shapes the storytellers’ health attitudes, values, beliefs, or behaviors.

Methods:

We conducted a meta-synthesis using the framework analysis method to generate analytic themes. We searched Medline, CINHAL, SocIndex, Embase, PsycINFO, SciELO, Academic Search Ultimate, Scopus, the Directory of Open Access Journals, and LIVIVO. We used the GRADE-CERQual approach to assess the confidence in the review findings.

Results:

We included 25 qualitative studies from six countries representing the experiences of 629 storytellers. Confidence in most review findings was moderate. Storytellers experience digital storytelling workshops as a safe space where they reframe the narratives around their health experiences. This re-storying process extends storytellers’ understanding of their health experiences, affords them a sense of agency and control, and motivates them to use their stories to support others.

Conclusion:

We found evidence that digital storytelling enables storytellers to reflect and emotionally engage with the narratives shared in the co-construction of digital stories, resulting in a narrative shift that is likely to be experienced as health-promoting.

Systematic Review Registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42023478062, PROSPERO CRD42023478062.

Introduction

A growing body of evidence indicates that digital storytelling as a participatory and community-based approach can provide storytellers with potential health-promoting benefits (1–4). During the digital storytelling process, six to eight individuals who share a common experience work together over three consecutive eight-hour sessions to co-create unique digital stories by sharing and discussing their lived experiences, personal beliefs, and values in response to specific life events (5–7). A trained facilitator guides the storytellers to express and explore their personal experiences in relation to the stories and feedback of fellow participants (5–7). The goal is for storytellers to review their narratives and select and combine music, images, and text with their voiceover to portray compelling stories, engage with the audience, and evoke emotional responses (8). This process results in three to five-minute visual digital narratives eliciting rich, affective, and nuanced insights into the storytellers’ lived experiences (9). The assumption is that as storytellers articulate their lived experiences in a digital story, they gain new insights that could empower them to adopt health-promoting behaviors, values, attitudes, or beliefs (6, 10, 11).

Three phases in the digital storytelling process could explain the mechanisms that drive these potential health-promoting benefits. The story construction phase, which includes writing the script and integrating images, video, and sound, has been found to afford storytellers increased control over their health experiences (12). The collaborative construction approach used during the so-called “story circle” phase, in which the storytellers share their stories with other participants (9), also appears to promote positivity in the group by reducing feelings of social isolation and increasing empathy (2). The final screening phase, where participants screen their stories and discuss their narratives and core elements (9), can also positively affect recipients’ cognition, affect, and health behavior, increase self-efficacy and social support, and positively impact physical and mental health (6, 11, 13). Reports indicate that given these potential benefits, digital storytelling can be used as a learning and capacity-building tool to raise awareness about health issues or to inform and support public health initiatives through advocacy and community empowerment (5, 7, 14). For example, researchers have successfully implemented digital storytelling in youth sexual health promotion (15), to foster dialogue and reduce power imbalances between mental health patients and clinicians (11) or to promote a greater sense of health and well-being in refugee women (16). Digital storytelling has also played a role in youth empowerment in diabetes prevention (17) and has been integrated into participatory efforts for food security and policy development (18). However, it has been argued that any benefits the storytellers may obtain are, at most, anecdotal, coincidental, and a fortunate by-product of the research process because digital storytelling applied in a research setting often has facilitators not trained as therapists, who primarily intend to explore a phenomenon of interest and not how the process influences health attitudes or behaviors (19).

Digital storytelling has previously been subject to review in academic research. However, there is still limited information on the potential health-promoting effects on storytellers because the reviews available did not primarily focus on their experiences (2, 19, 20), narrowed their search to a pediatric (20) or older adult population (21), or did not critically appraise the literature or follow a fully systematic process (3, 22, 23). Therefore, a qualitative evidence synthesis of primary research using an interpretative methodology can add to the current body of knowledge by explaining the potential health-promoting experiences of storytellers. Further, because digital storytelling has been used in diverse contexts, applying a meta-synthesis methodology can enable the integration of contextual nuances that might shape storytellers’ experiences.

Methods

Qualitative synthesis methodology

We used the meta-synthesis methodology coined by Stern and Harris (24) and refined by Wals and Downe (22) as an approach rooted in a hermeneutic paradigm that goes beyond the meta-aggregation of the data (23). This approach facilitated an interpretative or meaning-making analysis in generating descriptive themes through an iterative data synthesis process using a framework developed a priori. We initially identified each component of this framework and organized and integrated these components into analytic themes, capturing the health-promoting experiences of storytellers (25–27). The ENTREQ checklist items (28) guided our reporting of this meta-synthesis. In addition, some items of the PRISMA statement (29) including the study selection chart or the study characteristics table were used to achieve full transparency in reporting. We registered this meta-synthesis at the inception stage, and there were no deviations from the review protocol (PROSPERO; registration number CRD42023478062).

Theoretical framework

Salutogenesis was deemed a fitting theoretical framework because it departs from the premise that even in a situation of “illness,” individuals still possess healthy attributes within a continuum between health breakdown and full health (30, 31). We assumed that the digital storytelling process could reveal these healthy attributes and enhance storytellers' sense of coherence (SOC) through the expression and exploration of their personal experiences, fostering health-promoting attitudes, values, beliefs, or behaviors (5–7). Health promotion is this context was defined as the process of empowering people to, individually and collectively, increase control over their health and improve it (32).

Reflexive note

It was acknowledged from the outset that the reviewers’ experiences, values, and orientations would influence how meaning was derived from the data (33, 34). The principal reviewer had previous experiences participating in digital storytelling workshops and continuously reflected, critiqued, and evaluated his prior beliefs when synthesizing and interpreting the textual data. We consciously and deliberately looked for evidence that challenged these beliefs to avoid overemphasizing data aligned with pre-existing viewpoints. In addition, discussions with the other reviewers questioned how much the principal reviewer could have imposed meaning on the data items. None of the other reviewers had previously participated in a digital storytelling workshop, and as midwives and academics, this was their first contact with digital storytelling. We aimed to minimize the over-influence of the principal reviewer through this member reflection process and ensure the credibility of the findings (35).

Inclusion criteria

We included studies exploring the health-promoting experiences of storytellers participating in a digital storytelling workshop. We defined digital storytelling as a collaborative, participative, and group-based approach to co-create three- to five-minute digital stories portraying participants’ experiences of health. We considered studies for inclusion if they employed qualitative methods and included the qualitative components of mixed-methods studies. The inclusion criteria and their rationale are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1

| SPIDER | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | All populations, including pediatric populations | N/Aa | Digital storytelling is accessible to all populations with the ability to write, read, and use a computer. This can include the majority of the pediatric population. Digital storytelling is a facilitated process that can be adapted to all populations. In addition, digital storytelling experiences are unique for the storytellers. Including a wider population can provide a more general understanding of various health-promoting experiences. |

| Phenomenon of interest | The health-promoting potential of digital storytelling on the storyteller in a health context | Digital storytelling outside the health context | Digital storytelling has been widely used as a pedagogical approach in education and as an instrument for persuasion in marketing. It was essential to differentiate these studies from those addressing health issues. |

| Design | Interviews, focus groups, observations, case studies or action research | Surveys, online surveys | Measuring lived experience with an instrument remains a challenge. Researchers who have employed standard instruments to measure experiences of digital storytelling participation have not found evidence of an effect (54). |

| Evaluation | Health attitudes, values, beliefs, behaviors | N/A | Research evidence indicates that digital storytelling can lead to storytellers replacing their health narratives with health-promoting attitudes, values, beliefs or behaviors (82). |

| Research type | Qualitative or the qualitative components of mixed-method studies | Observational (Cross-sectional, etc.) experimental and quasi-experimental studies | To ensure a comprehensive representation of the available qualitative evidence. In addition, it provides richer and more in-depth data on the storytellers’ experiences. |

| Language | The search strategy was developed in English, German, and Spanish, but no language restrictions were applied during the search or screening process. | N/A | Based on the principal reviewer's language competence. The titles and abstracts of articles in other languages were translated using artificial intelligence through DeepL (translator function). |

| Type of publication | Primary research, including published peer-reviewed and grey literature (such as dissertations or other type of reports of primary qualitative research) | Non-primary research such as editorials, letters to the editor, reviews, case reports, and case series | Primary qualitative research offers rich and in-depth data, and grey literature (such as dissertations and reports) can contribute to more diverse viewpoints and nuances. |

Inclusion criteria.

The health-promoting experiences of storytellers participating in group-based digital storytelling workshops (Meta-synthesis, Switzerland, 2024).

Not applicable.

Data sources

We searched Medline (Ovid), CINHAL (Ebsco), SocIndex (Ebsco), Embase (Ovid), and PsycINFO (Ebsco) in November 2023. Additionally, a search in the SciELO, Academic Search Ultimate (Ebsco), Scopus, the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), and LIVIVO databases expanded the search for potential articles, particularly in Spanish, German, and the global south. The global reach of digital storytelling demanded the inclusion of articles in other languages. We also reviewed the lists of references from the included studies and retrieved grey literature using the Bielefeld Academic Search Engine (BASE).

Search strategy

The search strategy included Boolean and proximity operators, subject headings (MeSH), word searching (free text), and the use of spelling (truncation), syntax, line numbers, and publication-type filters to retrieve qualitative and mixed methods articles. We applied free-text terms to cover unavailable subject headings (36). We initially developed the search strategy in Medline (via Ovid) using keywords such as “digital” and “stories,” “storytelling,” “narratives,” “interviews,” or “qualitative” and adapted the search to fit other databases (see Supplementary Appendix A1). Search terms in English were then translated into German and Spanish, although the German terms proved unhelpful in retrieving articles (37).

Study screening

Two reviewers screened the retrieved articles independently. A third independent reviewer resolved disagreements arising during the stages of the screening process (38), including an initial title and abstract review guided by a screening tool, illustrating the inclusion criteria and assisting the reviewers with inclusion decisions. An initial piloting phase of this tool with twenty-five articles assisted reviewers in ascertaining its applicability and ability to maximize inter-rater reliability (39). All retrieved studies were exported after deduplication from Endnote to Covidence (40). We used the same screening process to screen the full-text articles of included studies.

Quality of included studies

We used the critical appraisal skills program (CASP) tool to evaluate the methodological rigor of the included studies (41). The principal reviewer independently assessed the quality of all included studies, and three reviewers performed the second independent assessment, each evaluating one-third of the included studies. Conflicts were resolved through consensus (42). We did not exclude any articles based on quality rating, but as a form of sensitivity analysis, we explored how removing the findings from weaker studies would influence the analytic themes (43).

Data extraction

We extracted data items such as the philosophical position, theoretical assumptions, research methods, contextual nuances, and findings. Using an adapted version of the Joanna Briggs Institute's (JBI) instrument (44), two reviewers piloted the tool with a purposive sample of two articles (45). The goal was to limit interpretation and selection errors (46). The principal reviewer independently extracted all data items from all included studies, and three reviewers independently extracted the data from one-third of the included studies.

Data synthesis

A framework analysis approach was used to synthesize the data. Two index papers of the best quality were selected to develop the initial framework. Two reviewers independently open-coded the findings using NVivo and created a matrix containing the initial codes and descriptive themes. We discussed each coded section to determine its significance and how it could answer the research question. Conflicts were resolved by returning to the index studies to agree on the most suitable theme. We entered the final themes into a spreadsheet to organize and map the data against this framework (see Supplementary Appendix A2). The initial framework was refined iteratively as new themes emerged from other studies. We created or allocated new themes to existing categories using the constant comparative approach. If a new theme emerged, we assigned a name (a metaphor) and compared it with those included in the initial framework (47). The quality of the included studies assisted reviewers in determining the emphasis of new emerging themes in contrast with those within the framework and their closeness to the theoretical framework. For instance, new themes from high-quality studies replaced or modified existing ones (see Supplementary Appendix A2).

After coding and mapping the data, we began interpretation, ensuring the original themes’ meaning was preserved (22). We used the framework to cluster metaphors and reach a consensus on the descriptive themes. Participant quotations for each review finding illustrate the final themes. We assessed the level of confidence in the review findings using the GRADE-CERQual approach, considering methodological limitations, coherence, that is, how well the data supported the review findings, their adequacy or the degree of richness and quantity of the data, and the relevance of the data concerning the specified context of the meta-synthesis (48). The assessments of these four components collectively contributed to a level of confidence ranging from high to very low (49) (see Supplementary Appendix A3). We defined a review finding as an analytical result that describes a phenomenon or an aspect of a phenomenon based on data from primary studies (50).

Results

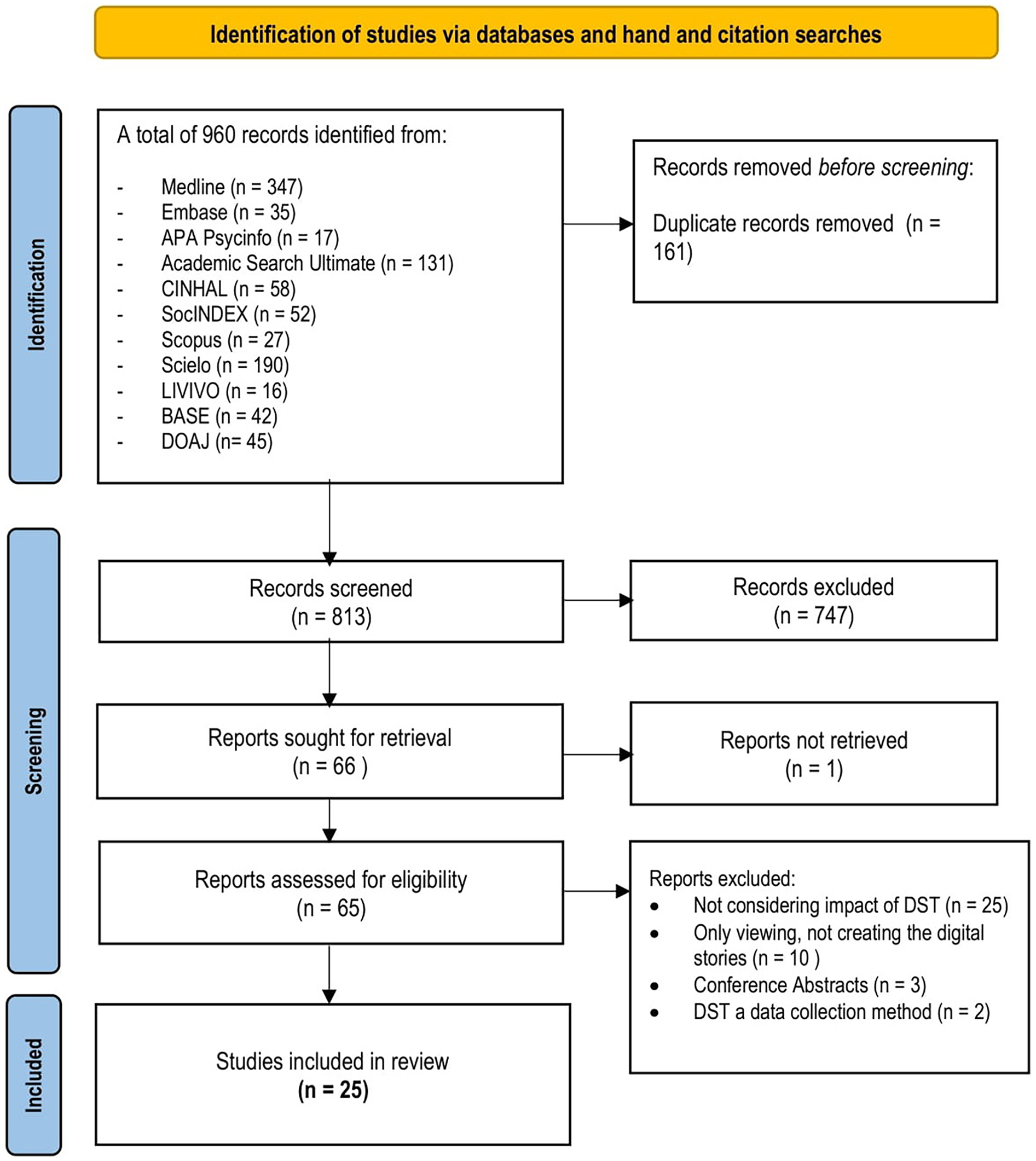

The review identified 974 records from electronic databases and hand and citation searching. After removing 161 duplicates, the reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of 813 articles. This led to the final inclusion of 25 peer-reviewed qualitative and mixed-methods articles exploring storytellers’ experiences (Figure 1).

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process (Switzerland, 2024).

Studies characteristics

The included studies were conducted in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Malawi and Zimbabwe. The sample sizes ranged from two participants to a sample of 342, making a total of 629 participants. Most studies used StoryCenter's (51) approach to digital storytelling or the approach of the Creative Narrations organization (52). A detailed description of the characteristics of the included studies can be found in Table 2.

Table 2

| Author(s), Year | Country | Population | Sample size | Context/Setting | Aim(s) or research question(s) | Philosophical/Theoretical underpinnings | Study design | Digital storytelling approach | Data collection | Analytic process | Reflexivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beltrán and Begun 2014 (5) | New Zealand | Māori community (20–45 years) | n = 6 | University Campus | To facilitate dialogue and use digital storytelling to interrupt contemporary challenges often faced by Indigenous communities | Historical trauma theory | Community-based participatory inquiry | StoryCenter | In-depth qualitative interviews | Thematic analysis | Yes |

| Boydell et al. 2018 (83) | Canada | Young people (16–23 years) with the first episode of psychosis | n = 9 | Early intervention clinic rural community | To produce individual digital stories describing how to manage psychosis in everyday life | The social world “does not consist of separate things. but of relationships.” | Community-based participatory inquiry | StoryCenter | Participant observation informal interviewing and reflexive field notes | Not described | No |

| Briant et al. 2016 (10) | USA | Working-class Hispanics of Mexican origin | n = 11 | Cancer Research Center | To explore if digital storytelling could be a culturally relevant tool for Hispanics/ Latinos of Mexican origin to share their experiences with cancer or other diseases. | Transportation theory | Community-based participatory action research and a narrative framework | Creative Narrations digital storytelling | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | Thematic analysis | No |

| De Vecchi et al. 2017 (11) | Australia | Mental health consumers and clinicians | n = 11 | Rural psychiatric service | To explore participation in digital storytelling and investigate the potential of digital storytelling as a research method. | Interpretative paradigm | Instrumental Case study and process evaluation | StoryCenter | Semi-structured Interviews | Not described | No |

| DiFulvio et al. 2016 (84) | USA | Puerto Rican Latinas (15–21 years) | n = 30 | New England City | To assess the effectiveness of the digital storytelling process in creating positive changes in participants’ sexual attitudes or values, self-esteem, social support, and empowerment (including self-efficacy, sense of hope for the future, and community activism). | Not reported | Mixed-methods | StoryCenter | Qualitative part: Open Ended questions | Not reported | No |

| Dixon and Isaac 2023 (85) | USA | Black African-American women, cisgender, queer, and middle-class, public health doctoral students | n = 2 | Weekly Zoom meetings | To explore how the intersection of racism, sexism, and socio-cultural expectations shape BFRB experiences. | Critical Narrative Archaeology of Self (AOS) | Autoethnography | StoryCenter | Digital storytelling process and online discussions | Content analysis | Yes |

| Ferrari et al. 2015 (7) | Canada | Persons of African, Caribbean, and European descent | n = 15 | Toronto, Ontario, | To examine how the process of making their digital stories can be “therapeutic” or “cathartic. | Not reported | Not reported | StoryCenter | workshop evaluation and 11 of them a survey | Thematic analysis | No |

| Fiddian-Green et al. 2017 (86) | USA | Puerto Rican Latinas (15–21 years) | n = 10 | New England City | To examine and delineate salient cultural paradigms of sexuality. | Constructivist grounded theory | Case-Study | StoryCenter | Semi structured interviews | Content, discourse analysis | No |

| Goodman 2019 (87) | Canada | Drug users (25–45 years) | n = 30 | Drug recovery clinic | To help transform widespread assumptions and prejudices about long-term heroin users | Not reported | Not described. | StoryCenter | Interviews | Descriptive, digital stories | Yes |

| Gubrium et al. 2016 (54) | USA | Puerto Rican Latinas (15–21 years) | n = 6 | New England City | To know if the digital storytelling process affected a participant's self-esteem, sense of empowerment, social support, or sexual attitudes or behaviors. | Constructivist grounded theory | Mixed-methods | StoryCenter | Story transcripts, Field notes, observation, follow-up semi-structured interviews | Using code matrix and three node structure | Yes |

| Gubrium et al. 2019 (53) | USA | Puerto Rican Latinas (15–21 years) | n = 30 | Offices of a community-based organization | To collaboratively interrogate and address experiences of interpersonal and structural violence and embodied trauma. | Critical Narrative | Digital storytelling as a research method | StoryCenter | Digital storytelling, field notes and follow-up interviews | Intertextual transcription method, content analysis, contextual analysis | Yes |

| Howard et al. 2023 (55) | Canada | People with endometriosis | n = 6 | Online workshops via Zoom. | To assess the feasibility of story co-creation and sharing. | Not reported. | Qualitative methods | StoryCenter | Reflective journals | Qualitative interpretive description | Yes |

| Jun et al. 2022 (88) | USA | Nurses from a not-for-profit public-health organization | n = 13 | Workshops offered within the nursing organization | To evaluate the first-person experiences of attending in-person digital storytelling workshops. | Not reported | Descriptive qualitative method | StoryCenter | Semi-structured phone interviews | Thematic analysis | Yes |

| Kim et al. 2021 (89) | USA | Adults (18 or older) who received a hematopoietic cell transplant | n = 4 | Not known | To explore experiences of participating in a 3-day digital storytelling workshop | Narrative theoretical model/social cognitive theory/constructivist grounded theory | Descriptive qualitative method | StoryCenter | Workshop evaluation questionnaire | Content analysis | No |

| Kim et al. 2023 (90) | USA | Vietnamese or Korean American women (18 or older) | n = 8 | Virtual digital storytelling via Zoom | To assess feasibility, acceptability and in-depth analysis of the mother's cultural experience of HPV | Constructivist grounded theory | Mixed methods | StoryCenter | Questionnaire, field notes, web-bsed workshop activtivities | Thematic analysis | No |

| Laing et al. 2017 (91) | Canada | Children and young adults cancer survivors (5–19 years) | n = 16 | Childreńs hospital | To determine how digital stories might be effective therapeutic tools | Hermeneutics | Not reported | StoryCenter | Semi-structured interviews | Hermeneutic | No |

| Laing et al. 2019 (92) | Canada | Adult (18 or older) patients with cancer | n = 10 | Outpatient cancer treatment center | To discover how the creation of a digital story affects adult patients with cancer | Hermeneutics | Qualitative, interpretive methodology | Two-hour sessions with assistant trained in digital storytelling | Semi structured interviews face to face and telephone | Hermeneutics | No |

| Lamarre & Rice 2016 (93) | Canada | Young Women with Eating Disorder Recovery | n = 10 | Not described | To illustrate the possibilities of a guided practice of digital storytelling for critical arts-informed research processes | Critical feminism/theoretical frame (post-structuralist) | Narrative | StoryCenter | Digital stories | Visual analysis | No |

| Lenette & Boddy 2013 (16) | Australia | Women with refugee backgrounds | n = 3 | Not reported | To explore women's experiences of being a refugee | Feminism | Visual ethnography | Not described. | Photovoice, Photo-eliciting and digital storytelling, in-depth interviews | Visual ethnography | No |

| Martin et al. 2019 (94) | Canada | Young women exposed to dating violence | n = 6 | University campus | To explore the impact of learning digital storytelling skills to promote change and interrupt the cycle of abuse. | Feminist, qualitative, and arts-based research | Digital storytelling as a research method | StoryCenter | Focus group | Not described | No |

| Njeru et al. 2015 (95) | USA | Somali and Spanish-speaking patients with type II diabetes | n = 8 | Healthy Community Partnership centre | To develop a diabetes digital storytelling intervention with and for immigrant and refugee populations. | Social Cognitive Theory, Narrative Theory, and social construction theory | Digital storytelling as a research method | StoryCenter | Digital Stories | Not described | No |

| Nyirenda et al. 2022 (96) | Malawi | Residents from Bangwe and Ndirande | n = 26 | Bangwe and Ndirande, Malawi | To assess if digital storytelling could be used to explore community perspectives on health concerns. | Gaventa's theories of power and participation | Digital storytelling as a research method | Similar to the StoryCenter approach | Digital Stories | Not described | No |

| Paterno et al. 2018 (97) | USA | Peer mentors in recovery from SUD | n = 5 | Community site in a rural county in New England | To assess the feasibility of using digital storytelling with peer mentors. | Not described | Digital storytelling as a research method | StoryCenter | In-depth, semi structured follow-up interviews | Thematic analysis | No |

| Wexler et al. 2013 (98) | USA | Young people from 12 rural villages in Northwest Alaska | n = 342 | Rural sparse populated areas of Alaska | To use digital storytelling as a health promotion strategy within a PYD approach. | Freirian Model | Mixed-methods | StoryCenter | Interviews after workshop | Coding but not further description | No |

| Willis et al. 2014 (99) | Zimbabwe | Young people with HIV (8-22 years) | n = 12 | Africaid's Zvandiri program | To evaluate the digital storytelling process as a therapeutic approach | Social constructionism | Qualitative methods | StoryCenter | Focus groups digital stories, field notes, | Thematic analysis | No |

Characteristics of the included studies.

The health-promoting experiences of storytellers participating in group-based digital storytelling workshops (Meta-synthesis, Switzerland, 2024).

Methodological rigor

There were some concerns with the overall methodological rigor of the included studies, with only three studies being rated as having no methodological weaknesses that would impact the transferability of the results (53–55). In this meta-synthesis, transferability refers to the extent to which study findings can be subjected to de-contextualization and abstraction to generalize the emerging themes to other situations (56). The biggest issue of concern was the lack of reflexivity, with 14 studies either poorly addressing or not reporting any aspects of personal, interpersonal, methodological, or contextual reflexivity. A detailed description of our assessments is presented in Table 3.

Table 3

| Author(s), Year | CASP tool questions | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | |

| Beltrán and Begun 2014 (5) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Can't tell | Yes |

| Boydell et al. 2018 (86) | No | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | No | No | Can't tell | No |

| Briant et al. 2016 (10) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| De Vecchi et al. 2017 (11) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Can't tell | Yes |

| DiFulvio et al. 2016 (88) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Dixon and Isaac 2023 (85) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Can't tell | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes |

| Ferrari et al. 2015 (7) | No | Can't tell | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | No | No | Cańt tell | Yes |

| Fiddian-Green et al. 2017 (86) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Goodman 2019 (87) | No | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Gubrium et al. 2016 (54) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gubrium et al. 2019 (53) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Howard et al. 2023 (55) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Jun et al. 2022 (88) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kim et al. 2021 (89) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kim et al. 2023 (90) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Laing et al. 2017 (91) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | No | Yes |

| Laing et al. 2019 (92) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Can't tell | Yes |

| Lamarre & Rice 2016 (93) | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | No | Can't tell | Yes |

| Lenette & Boddy 2013 (16) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Can't tell | Yes |

| Martin et al. 2019 (94) | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | No |

| Njeru et al. 2015 (95) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Can't tell | No | Can't tell | Yes |

| Nyirenda et al. 2022 (96) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Can't tell | Yes | Can't tell | No |

| Paterno et al. 2018 (97) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Can't tell | Yes |

| Wexler et al. 2013 (98) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | No | No |

| Willis et al. 2014 (99) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | No |

Methodological rigor of the included studies.

The health-promoting experiences of storytellers participating in group-based digital storytelling workshops (Meta-synthesis, Switzerland, 2024).

Synthesis output

This meta-synthesis generated 12 descriptive themes (review findings), of which nine were graded with moderate confidence, indicating that these review findings are likely a reasonable representation of the storytellers’ health-promoting experiences. Two themes were graded with high confidence and a single theme with low confidence, making them highly likely or possibly a reasonable representation of the storytellers’ experiences, respectively. From these descriptive themes, we derived four analytical themes:—“Re-Storying Lived Experience,” “The Ripple Effect Of Digital Storytelling,” “Investing And Processing Emotions,” And “Owning The Script.” The final framework and its associated CERQual gradings are presented in Table 4.

Table 4

| Descriptive themes (Review Findings) | Studies contributing to the review finding | GRADE-CERQual Assessment of confidence | Example of Supporting data | Analytical theme |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overcoming vulnerability—Entering the digital storytelling space often generates initial fears and apprehensions triggered by the prospect of sharing sensitive and intimate stories about health issues with strangers. Storytellers fear being judged or misunderstood and grapple with the uncertainty of how their stories unfold. Storytellers cautiously navigate the digital storytelling process, but this sense of vulnerability fades as they share their stories. Storytellers recognize their peerś bravery, inspiring them to share their truths and reinforcing the belief that their stories must be told. | 11 Studies (11, 53–55, 83, 84, 86, 88, 90, 91, 96) |

Moderate confidence | “In the beginning, I was really, really anxious about it, but even halfway through the first session, that anxiety definitely decreased just at how welcoming and accepting and just how common it felt our experience was. We had this like connection that was beyond just Endo, having Endo. It was really great” (55). “I think there might have been one person that wasn't quite ready, maybe being vulnerable. But it might be a little bit easier if they know that other people on their team are participating. Being around complete strangers for three days is kind of terrifying” (88). |

Re-storying lived experience |

| Deliberate sense-making—Storytellers make sense of their lived experiences of health, illness and trauma as they write their scripts, collect visual and auditory material to illustrate their stories and share them with fellow storytellers. This process provides a space for deliberate reflection, finding meaning from their experiences, and capturing their emotional state. Some storytellers find new meaning in their experiences and value the opportunity to learn more about themselves as individuals and community members through this deliberate process. | 14 Studies (5, 7, 10, 11, 54, 55, 83, 87, 88, 91, 92, 95, 97, 98) |

Moderate confidence | “It sort of forces you to reflect on things that maybe you don't sit down and do every day, right? It's not like you go, “Today I'm going to think about this.” This is kind of an opportunity that forces you into something like that. It made me think about things that maybe I didn't want to, or hadn't very much, you know?” (97). So it wasn't easy, to share my story, but I guess it's being able to step back from those immediate moments, and look at them a little more objectively. It really helps to make sense of things, make meaning, and see how your story is connected to other pieces of your life. we're looking for meaning, and I just wanted to find some meaning in what I'd been going through” (87). |

|

| Shaping or replacing existing narratives— Storytellers undergo a profound shift in perspective as they construct their stories, resulting in the altering, reshaping, or even replacing the narratives they initially brought into the digital storytelling process. Storytellers uncover previously unknown connections to other aspects of their lives by re-examining their own beliefs, perspectives, and lived experiences as they listen to the stories of others. Some storytellers view it as an opportunity to challenge and correct existing, socially accepted narratives and discourses and as an accomplishment. | 16 Studies (5, 7, 10, 11, 54, 55, 83–85, 87, 91–93, 96, 98, 99) |

Low confidence | “Life-changing stuff. You can see it. You can hear it in people's narratives. It's about talking through their story. You can hear the growth and the de-cluttering. Yeah, it's almost like watching a flower, like a peony rose… beautiful flowers…and it's just like watching them burst into life” (5). "I no longer want to put pressure on myself to live up to the definitions of those concepts [of Anorexia], whether externally or internally imposed. That's kind of the point” (93). |

|

| Sharing and connecting in a safe space—The digital storytelling process creates a safe and supportive space, an environment of mutual respect and understanding, where storytellers are empowered to speak freely about their experiences of health, even about their most guarded secrets, as they develop a sense of connection with other storytellers. | 7 Studies (5, 10, 11, 54, 55, 89, 97) |

Moderate confidence | “It was also nice to get so much support, because I don't know if I would've shared that story had I not had the environment being the way it was, because it was so safe, …it was kind of like a powwow, where we all came together and really understood where each other was coming from” (5). “I think it can allow someone to enter that space with you and someone might not have that lived experience, but that story you're telling might map onto some other experiences they've had..you can create a bit of shared space and shared understanding” (11). | The ripple effect of digital storytelling |

| From empathy to compassion: Listening to other storytellers' stories generates an empathetic response driven by learning about their shared experiences, motivating storytellers to act and mutually support each other. Some storytellers gain an awareness that they are part of something bigger and feel that their stories can help both fellow storytellers and those beyond the digital storytelling workshop. They feel compelled to tell their stories to help others. | 14 Studies (5, 10, 11, 54, 55, 83, 84, 87, 89–91, 97–99) |

Moderate confidence | “I think it was great when everyone talked and supported each other. Number one, if you heard their story, you understood where they were coming from because you can actually feel it and connect to those who experienced the same thing” (89). “A lot of people down here, they get in this rut, you know, and it just seems like there's no way out. I want to say that there is a way out and it can be very rewarding” (87). |

|

| Sharing stories brings comfort—During digital storytelling, storytellers learn that they are not alone, which brings them comfort. Knowing that others have similar experiences validates the storytellers' feelings and emotions, and storytellers find common ground in their experiences, generating a sense of group hope and togetherness. | 8 Studies (5, 7, 10, 53–55, 83, 88) |

Moderate confidence | “It reminded me that I wasn't alone. Not only are there others who share my experiences, but [they] share my view of the experiences.” (7). “I find myself relating to every single story. I have a story within that story … and then I think maybe I need to get to know someone else.” (91). “I find myself relating to every single story. I have a story within that story … and then I think maybe I need to get to know someone else” (91). |

|

| Increased Sense of Community Belonging—Learning that others go through similar situations generates a strong bond between the storytellers, inspiring a commitment beyond the workshops. Storytellers demonstrate a commitment to sustaining and growing their newly gained community. | 10 Studies (5, 10, 11, 54, 55, 88, 89, 94, 97, 98) |

High confidence | “I was very moved by [name] story as so much of my own is captured in her words. Again, I felt a sense of connection and of a deep understanding from my fellow participants, which was really beautiful and made me want to think about how to connect further with these women or others who have Endo” (55). “[The DST] allowed me to get to know my peers on a more intimate level. Even though we worked together, there was so much we didn't know about each other and, I mean, their videos brought me to tears, and I felt like I really got to know them” (97). |

|

| Experiencing emotional resonance—The digital stories portray emotions and feelings that resonate with the storytellers. As storytellers engage with the stories, they recognize and connect with these emotions as they realize they all share similar emotional experiences. | 8 Studies (5, 11, 54, 55, 88, 91, 92, 94) |

Moderate confidence | “…I found it challenging because some of the stories were.. emotionally resonating..you felt for what people go through, what's behind that outer shell that you show to the world” (11). “Maybe it's the shared emotions like sometimes the release of the emotions …. Being heard and being seen as a human, not just as a nurse … Our whole job is all about secondary trauma; hearing stories that are so challenging that you have to be able to put that somewhere ….” (88). |

Investing and processing emotions |

| Harnessing the amplified emotions—Triggered by the evoked emotional resonance, storytellers experience a heightened emotional awareness as they write and produce their digital stories and listen to the stories of others. This is experienced as an opportunity to work and process these emotional burdens and open up to sharing things that otherwise, in other contexts, they would not share. The emotions drive storytellers to construct stories that portray “the rawness of their experiences”. | 8 Studies (5, 55, 84, 87, 89, 91, 92, 94, 97) |

Moderate confidence | “I was surprised at how much emotional I was when I went over my real story. I never thought of once any of the feelings that I was having. This workshop opens me up to realize the value of talking and sharing emotions. Now I am sharing my emotions with my family” (89). “The making of the video was out of anger, like you know, I just wanted to get it out so bad. And yeah, it's a little hard to explain.…Like I just let it all spill out on the video, kind of thing…I was really angry when I was looking at those pictures” (89). “Like, your choice really is to let [the emotions] crush you or not. And when your choice is to not, then you have no choice but to stand up and make sure you are in the best frame of mind, which means you have to do something with those emotions” (92). |

|

| Coming to terms with experiences of health— Storytellers experience a sense of relief from their emotional burdens, feel liberated from memories of adverse experiences, and feel at peace, having shared their stories with fellow storytellers who understand their pain and suffering. Some storytellers refer to the process as therapeutic and cathartic because it helps them confront and process their emotions and feel healed, having achieved some form of personal growth. | 11 Studies (5, 7, 10, 54, 55, 83, 84, 87, 88, 91, 93) |

Moderate confidence | “I grew. I was liberated and at peace. I'm at peace with myself in a way that I've not been for…I don't know…probably forever…by getting [the story] out, because I harboured it for so long. That's not a healthy way to be. It really makes…well, talking about health and trauma… it is medicine. That's the best way I can say it” (5). “[I] feel no more guilt now that my story is right,” and others who spoke of the value of “open[ing] up” and “let[ting] go” of “things we've kept inside” (84). |

|

| Increased sense of control over their experiences— As storytellers construct their stories, they go through a process of self-discovery that appears to build their confidence. They feel they have some influence or power over their circumstances. This is amplified by the collaborative approach to story development, which moves them to co-create stories that either challenge existing narratives and discourses about their lived experiences or send a message to help others. | 13 Studies (5, 7, 10, 53–55, 83, 84, 87, 89, 91, 97, 99) |

High confidence | “…I just think that when you look at someone who's like you—looks like you—and they tell a story that is similar to yours, and they've come through it and they are now putting voice to it, and now they're not hurting, it gives you hope. It gives you hope that, ‘Well, what if I put a voice to my story?” (5). “…it is ‘brave of us to share our stories—it teaches us as mothers, parents—that these are the things we can teach our children—about domestic violence, birth control. They don't have to go through the same thing. This brought us together as mothers and people” (53). “I can now take control of my life, I have kissed away the fear and frustration” (99). “Through support, I feel confident and able to make informed choices. I am now confident, independent and most of all ever smiling” (99). |

Owning the Script |

| Gaining Agency—After completing the digital story, storytellers recognize that the stories can potentially resonate with others. They acquire a sense of purpose and express their desire to use their stories to improve the lives of those with similar experiences. | 8 Studies (5, 10, 54, 55, 89, 92, 97, 99) |

Moderate confidence | “I definitely want to take my story and show it to my iwi, my family, and I want to see if they would be interested in doing some work of this nature. I feel like I've been given something that will help me help someone in a very simple way…” (5). “…this digital recording it's very important because we're making it known…we are letting our community know that many things can be prevented.” (10). I was feeling so lost…and then now I just kind of feel filled with so much purpose. Just being able to share your story with someone who wants to listen is…well…I, I think we often don't realize that something simple and little like that can be so helpful” (89). |

Framework and associated CERQual gradings.

The health-promoting experiences of storytellers participating in group-based digital storytelling workshops (Meta-synthesis, Switzerland, 2024).

Re-storying lived experience

Participation in a digital storytelling workshop prompts storytellers to alter, reshape, or even replace their narratives concerning their lived experiences of health with new or more positive ones. We assumed the distinction between stories, the specific tales shared about their experiences, and narratives, the broader contextual or social resources storytellers draw upon to construct their stories (57). Storytellers reconsider their experiences as they listen to and share stories with fellow participants, triggering a deliberate sense-making process that helps storytellers make new connections to other aspects of their lives and gain new narratives. They use these new narratives to create their digital stories, often leading to telling a different story than initially intended. This re-storying becomes an accomplishment and reshapes their understanding of their experiences and broader discourses around their health. Initially, storytellers feel vulnerable sharing sensitive and intimate stories about their health with strangers, worrying about being judged or misunderstood and about how their stories will unfold. However, this apprehension fades as they listen to the stories of others, finding inspiration and reinforcing the belief that their stories must be told.

The ripple effect of digital storytelling

Despite their initial apprehension, storytellers experience digital storytelling as a safe, supportive, health-promoting space. As they listen to the stories, they learn that all share similar experiences, creating an environment of understanding where they feel empowered to share their health experiences openly. The stories resonate with the storytellers and make them feel connected, validated, and comforted by learning that they are not alone. It is a ripple effect, which begins with the storytellers becoming story recipients. Engaging with the stories provokes an empathic response from fellow storytellers, triggering emotional and physical responses such as expressing admiration, feeling inspired or moved, or even embracing the narrator to comfort them. These responses, in turn, foster a sense of community belonging, make participants feel hopeful, and inspire a commitment beyond the workshop. Storytellers realize they are part of something bigger and feel compelled to tell their stories to help others. This shift from empathy to compassion involves a deep connection with the storytellers’ experiences of health, which requires a personal knowing of those experiences, evoking caring actions that bring comfort (58). Compassion here is a deliberate process in which storytellers treat others as they wish to be treated themselves.

Investing and processing emotions

The storytellers share more than similar stories and experiences. They vividly recognize the emotions described and portrayed in the stories shared as some of their own. Learning about and experiencing the emotions of others heightens the storytellers’ awareness of their own emotional state. Storytellers harness this intensified emotional awareness and use it to work and process their emotional burdens into their digital stories. Their emotional responses drive storytellers to open up to sharing things they would not express elsewhere and co-construct compelling stories that portray the authenticity and rawness of their experiences. Some storytellers refer to this process as therapeutic and cathartic because they experience some relief from their emotional burdens by sharing their stories with empathetic listeners who understand what they are going through.

Owning the script

The digital storytelling process affords storytellers the confidence to steer the narratives around their experiences. They acquire a sense of control over their personal narratives by articulating them into a digital story. Some storytellers view the process as an opportunity to challenge existing narratives and discourses about living with a particular condition or trauma. They deliberately seek to convey a message, a counternarrative, a first-hand and accurate account of their experiences. They aim to share their truths with others, even if it means evoking uncomfortable responses from recipients. Upon completing their digital stories, storytellers often recognize the potential impact of their narratives on others. Through this process, storytellers gain agency and are motivated to transform their digital stories into powerful tools to support others.

Discussion

This meta-synthesis used the framework analysis method to synthesize the health-promoting experiences of storytellers participating in a group-based digital storytelling workshop. Our GRADE-CERQual assessment of the findings provided evidence of moderate confidence that co-constructing digital stories about health experiences can shape the storytellers’ attitudes, values, beliefs, or behaviors. This is evidenced by four analytic themes containing health-promoting attributes likely to reasonably represent the storytellers’ experiences.

To gain an insight into how these four analytic themes contain health-promoting attributes, we employed the salutogenic lens underpinning this meta-synthesis. The first analytic theme — Re-storying Lived Experience — illustrates a narrative shift that can strengthen the storytellers’ sense of coherence (SOC). The SOC expresses an individual’s ability to successfully respond to a stressful situation when it is deemed worth dealing with. It is essential for developing and maintaining health, as a stronger SOC generally correlates with better-perceived health (59–61). The SOC can be strengthened by reflecting on stressful situations and identifying appropriate resources (62). We explained that the narrative shift results from a reflection process triggered by the storytellers’ deep engagement with the shared narratives. Although the included studies do not always detail the narratives` characteristics shared between the storytellers, it is plausible that storytellers are exposed to various narrative structures and contents that can have health-promoting attributes during the storytelling process. For instance, research evidence has identified key often shared mental health recovery narrative forms, including narratives of escape, such as resisting stigma, or narratives of enlightenment, where the storyteller views the illness or trauma as ultimately positive (63). There is strong evidence suggesting that narratives of this kind can be health-promoting by reducing stigma, helping individuals better understand mental illness and how to recover, or validating their experiences (13). Exposure to the narratives of individuals who have faced or overcome real-life health challenges has also been found to help storytellers (64). Thus, the various narratives forming the basis of the shared digital stories can be considered resources storytellers draw upon to re-examine or revise their own narratives, steering them towards health-promoting forms, content, or structures. From a salutogenic perspective, the more resources (generalized or specific) storytellers possess to appraise or reflect on their experiences, the more likely they are to shift their narratives and perceive them as more manageable and meaningful, strengthening their SOC (65, 66). The conceptual model on the effects of digital storytelling confirms that storytellers undergo an internal self-reflection exercise and engage in a retrospective sense-making process moderated by the dominant narratives. This process helps storytellers identify their stories’ turning points and transitions, derive meaning from them, and formulate new, more meaningful, and positive narratives (12).

The second analytical theme — The Ripple Effect Of Digital Storytelling — describes storytellers’ collective or social experiences. In the digital storytelling environment, the storytellers find comfort and a safe space to connect and empower each other. The salutogenic model explains that the SOC can be collectively strengthened in a group setting if the group perceives itself as a cohesive unit (67). This is linked to the group´s duration together, size, consensus in their perceptions, and its members’ interwoven self- and social identity (67, 68). Most studies in this meta-synthesis conducted workshops with groups of 6–8 individuals suffering from similar health conditions during three 8-hour long workshops, a level of engagement and group size that makes it plausible for the storytellers to see themselves as a cohesive group. In addition, they appear to achieve a high degree of consensus about their health experiences. Reports confirm that during the group phases, storytellers develop a sense of connection, unity, and community belonging (12, 54). This justifies the assumption that the shared stories and their underlying narratives can also become group resources that storytellers can collectively mobilize and activate to relieve the tension caused by their shared experiences. Thus, it is likely that the digital storytelling process is capable of strengthening the storytellers’ SOC by creating a group setting where each member is empowered to draw on these collective resources (67, 68).

The third analytic theme — Investing And Processing Emotions — denotes that regardless of the narrative characteristics the storytellers are exposed to, creating a digital story evokes a series of affective and emotional responses that can further contribute to a sense of individual and group well-being. Some of these emotional responses reported by recipients of stories can include positive emotions, such as feelings of gratitude or comfort, admiration or being inspired, and negative emotions, such as sadness, distress, or heartbreak (13). Storytellers embrace the opportunity to portray their emotions in a digital story and harness and process them to develop new perspectives of their experiences and move forward (69). Reports indicate that crafting a narrative about health enables individuals to gain a new perspective on their emotional experiences (70) and express and process them through reflection, reframing, or replacement (71). Working on these emotions in this form has been found to have significant health-promoting effects (72), for instance, in people who have cancer by reducing fatigue and improving their general mood (73) or in women with body image and appearance concerns affecting their sleep and eating behaviors by increasing their resilience and reducing physical symptoms (74). It appears that the mechanism behind these benefits involves emotional acceptance, where the storytellers do not seek to suppress or avoid their emotions but accept them, both negative and positive, reducing their emotional distress and enhancing emotional well-being (12). This way, storytellers establish strong emotional bonds with fellow storytellers, fostering unity, cohesion, and belonging. The salutogenic model explains that this type of emotional closeness to a social group contributes to the individual's appraisal that it is worth investing energy and resources to address a particular stressor (30, 31, 75). This appraisal is one of the most critical components of the SOC, meaningfulness, as it refers to the motivational and emotional entity that determines whether an individual is willing to deal with a particular situation (76). Meaningfulness can be maintained or enhanced by investing in four crucial areas of life, including main activity, inner emotions, social connections, and existential concerns (76). The three-phase digital storytelling process acknowledges that people “understand and give meaning to their lives through the stories they tell” (77) and addresses these four crucial areas of life. Thus, whilst it deals with comprehensibility and manageability, it focuses strongly on meaningfulness through reflection.

The fourth analytical theme — Owning The Script — explains that the narrative shift is a deliberate act by the storytellers driven by a newly gained sense of control. The collaborative approach to story construction instills the belief in storytellers that they can steer the narrative in the direction of their choosing. It has been reported that this is a turning point that allows storytellers to re-story their experiences and support their efforts to confront and deal with illness or traumatic events and move on with their lives (78). The salutogenic model can explain this theme by digital storytelling fostering empowerment and reflection that facilitates the identification of the stories and their narratives as resistance resources that influence behavior (62). This is often referred to as gaining personal agency in storytelling, where storytellers actively resist being defined by a dominant discourse and become the active change agents of their own narratives (63, 79). The conceptual model on the effects of digital storytelling cites Bandurás construct of self-efficacy to explain this phenomenon (12). Bandura postulated that self-efficacy primarily emerges through past experiences, vicarious experiences, verbal appraisals from trusted individuals, and emotional arousal (80), all aspects addressed during the storytelling process. According to Fiddian-Green and others, Storytellers work on shared and individual emotional challenges, fostering self-renewal and empowerment while highlighting various experiences that can be acted upon (12). This sense of control also stems from participants’ acquisition of technical and emotional skills that culminate in a digital story (12).

Limitations

We employed a comprehensive and systematic search strategy but included studies with limited methodological quality. While the reviewers considered these limitations in interpreting the data, recent reports have questioned the rigor of the CASP tool to identify potential methodological strengths and limitations of qualitative evidence (81). Thus, it is uncertain whether using a more comprehensive tool such as the recently published CAMELOT would decrease confidence in the findings. In addition, some of the included studies did not seek to primarily address the experiences of the storytellers, limiting the richness of the data for synthesis. We could not uncover the extent to which each phase of the digital storytelling process provides storytellers with the highest health-promoting value. The data from the included studies treated the entire process as a compound intervention.

Conclusion

This meta-synthesis addressed exclusively the health-promoting experiences of the storytellers participating in a facilitated, collaborative, and participative group-based digital storytelling workshop. The data provided evidence of moderate confidence that any health-promoting benefits of digital storytelling stem primarily from the storyteller's ability to revise and re-examine their existing stories and the narratives underpinning their lived experiences of health. This process results in a narrative shift likely to contain health-promoting attributes that can shape the storytellers’ health attitudes, values, beliefs, or behaviors. It is clear from the evidence that there is a before and after the workshop. However, considering that both negative and positive narratives could contain health-promoting attributes, there is a need to explore further the types of narratives shared or that emerge in such workshops and provide the strongest health-promoting benefit. Thus, professionals and researchers considering digital storytelling as a strategy in health promotion should carefully monitor the types of narratives shared and the directions that these take. The salutogenic model can explain how the process can be health-promoting for the individual storytellers and them as a cohesive group. Finally, we acknowledge that the analytical themes are not isolated constructs but emerge in response to one another. While we present them sequentially, they do not necessarily represent a linear progression of the storytellers’ experiences. Instead, they interact dynamically, each theme enriching and amplifying the others. This interconnectedness underscores the complexity of the storytellers’ health-promoting experiences and provides a more holistic and nuanced understanding.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this meta-synthesis are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition. BB: Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Validation, Visualization. VL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing, Validation. AK: Data curation, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Validation. RE: Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. ML: Data curation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This meta-synthesis was partly funded by the Amaari Foundation, which funds and supports projects promoting natural birth. It is part of a PhD project in which the principal reviewer is investigating how digital storytelling can support pregnant women suffering from fear of childbirth. Open access funding by Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW).

Acknowledgments

The principal reviewer acknowledges the invaluable contributions of John Barbrook, a faculty librarian at Lancaster University, for his assistance in designing the search strategy.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Microsoft Copilot was used to find suggestions for structuring some sentences and wording in this manuscript to reduce the word count and meet the requirements of Frontiers.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fdgth.2025.1607897/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Evans BC Crogan NL Bendel R . Storytelling intervention for patients with cancer: part 1–development and implementation. Oncol Nurs Forum. (2008) 35(2):257–64. 10.1188/08.ONF.257-264

2.

McCall B Shallcross L Wilson M Fuller C Hayward A . Storytelling as a research tool used to explore insights and as an intervention in public health: a systematic narrative review. Int J Public Health. (2021) 66:10–2. 10.3389/ijph.2021.1604262

3.

West CH Rieger KL Kenny A Chooniedass R Mitchell KM Winther Klippenstein A et al Digital storytelling as a method in health research: a systematic review. Int J Qual Methods. (2022) 21:16094069221111118. 10.1177/16094069221111118

4.

Kim SS Lee SA Mejia J Cooley ME Demarco RF . Pilot randomized controlled trial of a digital storytelling intervention for smoking cessation in women living with HIV. Ann Behav Med. (2019) 54(6):447–54. 10.1093/abm/kaz062

5.

Beltrán R Begun S . ‘It is medicine’:narratives of healing from the aotearoa digital storytelling as indigenous media project (ADSIMP). Psychol Dev Soc J. (2014) 26(2):155–79. 10.1177/0971333614549137

6.

De Vecchi N Kenny A Dickson-Swift V Kidd S . How digital storytelling is used in mental health: a scoping review. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2016) 25(3):183–93. 10.1111/inm.12206

7.

Ferrari M Rice C McKenzie K . ACE pathways project: therapeutic catharsis in digital storytelling. Psychiatr Serv. (2015) 66(5):556. 10.1176/appi.ps.660505

8.

Davey NG Benjaminsen G . Telling tales: digital storytelling as a tool for qualitative data interpretation and communication. Int J Qual Methods. (2021) 20:16094069211022529. 10.1177/16094069211022529

9.

Gubrium A . Digital storytelling: an emergent method for health promotion research and practice. Health Promot Pract. (2009) 10(2):186–91. 10.1177/1524839909332600

10.

Briant KJ Halter A Marchello N Escareño M Thompson B . The power of digital storytelling as a culturally relevant health promotion tool. Health Promot Pract. (2016) 17(6):793–801. 10.1177/1524839916658023

11.

De Vecchi N Kenny A Dickson-Swift V Kidd S . Exploring the process of digital storytelling in mental health research:a process evaluation of consumer and clinician experiences. Int J Qual Methods. (2017) 16(1):1609406917729291. 10.1177/1609406917729291

12.

Fiddian-Green A Kim S Gubrium AC Larkey LK Peterson JC . Restor(y)ing health: a conceptual model of the effects of digital storytelling. Health Promot Pract. (2019) 20(4):502–12. 10.1177/1524839918825130

13.

Rennick-Egglestone S Morgan K Llewellyn-Beardsley J Ramsay A McGranahan R Gillard S et al Mental health recovery narratives and their impact on recipients: systematic review and narrative synthesis. The Canad J Psychiatry. (2019) 64(10):669–79. 10.1177/0706743719846108

14.

Gubrium AC Hill AL Flicker S . A situated practice of ethics for participatory visual and digital methods in public health research and practice: a focus on digital storytelling. Am J Public Health. (2014) 104(9):1606–14. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301310

15.

Guse K Spagat A Hill A Lira A Heathcock S Gilliam M . Digital storytelling: a novel methodology for sexual health promotion. Am J Sex Educ. (2013) 8(4):213–27. 10.1080/15546128.2013.838504

16.

Lenette C Boddy J . Visual ethnography and refugee women: nuanced understandings of lived experiences. Qual Res J. (2013) 13(1):72–89. 10.1108/14439881311314621

17.

Toussaint DW Villagrana M Mora-Torres H de Leon M Haughey MH . Personal stories: voices of latino youth health advocates in a diabetes prevention initiative. Prog Community Health Partnersh. (2011) 5(3):313–6. 10.1353/cpr.2011.0038

18.

Jernigan VB Salvatore AL Styne DM Winkleby M . Addressing food insecurity in a native American reservation using community-based participatory research. Health Educ Res. (2012) 27(4):645–55. 10.1093/her/cyr089

19.

de Jager A Fogarty A Tewson A Lenette C Boydell KM . Digital storytelling in research: a systematic review. Qual Rep. (2017) 22(10):2551–2. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol22/iss10/3/

20.

Wilson DK Hutson SP Wyatt TH . Exploring the role of digital storytelling in pediatric oncology patients’ perspectives regarding diagnosis: a literature review. Sage Open. (2015) 5(1):2158244015572099. 10.1177/2158244015572099

21.

Stargatt J Bhar S Bhowmik J Al Mahmud A . Digital storytelling for health-related outcomes in older adults: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. (2022) 24(1):e28113. 10.2196/28113

22.

Walsh D Downe S . Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. (2005) 50(2):204–11. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03380.x

23.

McCaffrey G Raffin-Bouchal S Moules NJ . Hermeneutics as research approach: a reappraisal. Int J Qual Methods. (2012) 11(3):214–29. 10.1177/160940691201100303

24.

Stern PN Harris CC . Women’s health and the self-care paradox: a model to guide self-care readiness. Health Care Women Int. (1985) 6(1-3):151–63. 10.1080/07399338509515689

25.

Aveyard H Payne S Preston N . Different methods for doing a literature review. In: A Postgraduate’s Guide to Doing a Literature Review in Health and Social Care. 2nd edLondon: McGraw-Hill Education Open University Press (2021). p. 22–6.

26.

Finlayson K Downe S . Why do women not use antenatal services in low- and middle-income countries? A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. PLoS Med. (2013) 10(1):e1001373. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001373

27.

Kutsyuruba B McWatters S . Hermeneutics. In: OkokoJMTunisonSWalkerKD, editors. Varieties of Qualitative Research Methods: Selected Contextual Perspectives. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2023). p. 217–23.

28.

Tong A Flemming K McInnes E Oliver S Craig J . Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2012) 12(1):181. 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181

29.

Page MJ Moher D Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al PRISMA 2020 Explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. (2021) 2021(372):n160. 10.1136/bmj.n160

30.

Mittelmark MB Bauer GF . The meanings of salutogenesis. In: MittelmarkMBSagySErikssonMBauerGFPelikanJMLindströmBet al editors. The Handbook of Salutogenesis [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2017). p. 7–13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435854/

31.

Vinje HF Langeland E Bull T . Aaron antonovsky’s development of salutogenesis, 1979 to 1994. In: MittelmarkMBSagySErikssonMBauerGFPelikanJMLindströmBet al editors. The Handbook of Salutogenesis [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2017). p. 25–40. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435854/

32.

Organization WH. Health Promotion Glossary of Terms 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021).

33.

Guba EG Lincoln YS . Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc (1994). p. 105–17.

34.

Moon K Blackman D . A guide to understanding social science research for natural scientists. Conserv Biol. (2014) 28(5):1167–77. 10.1111/cobi.12326

35.

Olmos-Vega FM Stalmeijer RE Varpio L Kahlke R . A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE guide no. 149. Med Teach. (2023) 45(3):241–51. 10.1080/0142159X.2022.2057287

36.

McGowan J Sampson M Salzwedel DM Cogo E Foerster V Lefebvre C . PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. (2016) 75:40–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021

37.

DeJean D Giacomini M Simeonov D Smith A . Finding qualitative research evidence for health technology assessment. Qual Health Res. (2016) 26(10):1307–17. 10.1177/1049732316644429

38.

Lefebvre C Glanville J Briscoe S Littlewood A Marshall C Metzendorf M et al Chapter 4: searching for and selecting studies. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 62. Chichester: Cochrane (2021).

39.

Polanin JR Pigott TD Espelage DL Grotpeter JK . Best practice guidelines for abstract screening large-evidence systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Res Synth Methods. (2019) 10(3):330–42. 10.1002/jrsm.1354

40.

Covidence Systematic Review Software. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation (2021). Available online at:www.covidence.org

41.

CASP. CASP qualitative studies checklist. (2018). Available online at: https://casp-uk.net/casp-checklists/CASP-checklist-qualitative-2024.pdf (Accessed December 22, 2023).

42.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. (2021) 372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71

43.

Carroll C Booth A . Quality assessment of qualitative evidence for systematic review and synthesis: is it meaningful, and if so, how should it be performed?Res Synth Methods. (2015) 6(2):149–54. 10.1002/jrsm.1128

44.

Aromataris E Lockwood C Porritt K Pilla B Jordan Z . JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute (2024). 10.46658/JBIMES-24-01

45.

Mathes T Klaßen P Pieper D . Frequency of data extraction errors and methods to increase data extraction quality: a methodological review. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2017) 17(1):152. 10.1186/s12874-017-0431-4

46.

Haywood KL Hargreaves J White R Lamb SE . Reviewing measures of outcome: reliability of data extraction. J Eval Clin Pract. (2004) 10(2):329–37. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2003.00411.x

47.

Aveyard H Payne S Preston N . How do I Analyse snd Synthesise my Literature Review. A Postgraduate’s Guide to Doing a Literature Review in Health and Social Care. 2nd EdNew York: McGraw-Hill Education (2021). p. 141–7.

48.

Lewin S Bohren M Rashidian A Munthe-Kaas H Glenton C Colvin CJ et al Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings—paper 2: how to make an overall CERQual assessment of confidence and create a summary of qualitative findings table. Implement Sci. (2018) 13(1):10. 10.1186/s13012-017-0689-2

49.

Lewin S Booth A Glenton C Munthe-Kaas H Rashidian A Wainwright M et al Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implement Sci. (2018) 13(1):2. 10.1186/s13012-017-0688-3

50.

Lewin S Glenton C Munthe-Kaas H Carlsen B Colvin CJ Gülmezoglu M et al Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: an approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLoS Med. (2015) 12(10):e1001895. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001895

51.

Lambert J . Seven Steps of Digital Storytelling. Digital Storytelling: Story Work for Urgent Times. 6th EdBerkeley, CA: Digital Diner Press (2020). p. 60–83.

52.

Clark JN, Porfirio L, “Shaneequa” Brokenleg I, Schachter J, Angulo A, Freidus N. Creative narrations. Tucson AZ. (2024). Available online at: Creative Narrations - Multimedia for Community Development (Accessed February, 17, 2024).

53.

Gubrium A Fiddian-Green A Lowe S DiFulvio G Peterson J . Digital storytelling as critical narrative intervention with adolescent women of Puerto Rican descent. Crit Public Health. (2019) 29(3):290–301. 10.1080/09581596.2018.1451622

54.

Gubrium AC Fiddian-Green A Lowe S DiFulvio G Del Toro-Mejías L . Measuring down: evaluating digital storytelling as a process for narrative health promotion. Qual Health Res. (2016) 26(13):1787–801. 10.1177/1049732316649353

55.

Howard AF Noga H Parmar G Kennedy L Aragones S Bassra R et al Web-based digital storytelling for endometriosis and pain: qualitative pilot study. JMIR Form Res. (2023) 7:e37549. 10.2196/37549

56.

Smith B . Generalizability in qualitative research: misunderstandings, opportunities and recommendations for the sport and exercise sciences. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. (2018) 10(1):137–49. 10.1080/2159676X.2017.1393221

57.

Wong G Breheny M . Narrative analysis in health psychology: a guide for analysis. Health Psychol Behav Med. (2018) 6(1):245–61. 10.1080/21642850.2018.1515017

58.

Peters MA . Compassion: an investigation into the experience of nursing faculty. Int J Hum Caring. (2006) 3:38–46. 10.20467/1091-5710.10.3.38

59.

Eriksson M Lindström B . Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and the relation with health: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2006) 60(5):376–81. 10.1136/jech.2005.041616

60.

Eriksson M . The sense of coherence in the salutogenic model of health. In: MittelmarkMBSagySErikssonMBauerGFPelikanJMLindströmBet al editors. The Handbook of Salutogenesis [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2017). p. 91–6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435854/

61.

Mittelmark MB Bauer GF . Salutogenesis as a theory, as an orientation and as the sense of coherence. In: MittelmarkMBBauerGFVaandragerLPelikanJMSagySErikssonMet al editors. The Handbook of Salutogenesis 2022. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2022). p. 11–7. 10.1007/978-3-030-79515-3_3

62.

Super S Wagemakers MAE Picavet HSJ Verkooijen KT Koelen MA . Strengthening sense of coherence: opportunities for theory building in health promotion. Health Promot Int. (2015) 31(4):869–78. 10.1093/heapro/dav071

63.