Abstract

Introduction:

Digital mental health interventions (DMHIs) are increasingly used to support child and youth mental health, yet the scope and characteristics of universal (Tier 1) DMHIs remain poorly defined.

Methods:

This scoping review synthesized peer- reviewed studies of universal DMHIs delivered to children and youth aged 0–18 years.

Results:

Use of online programs and hybrid delivery were prevalent. Many programs used an independent structure, while facilitation varied across self- led, facilitator-led, and both-led models. Outcomes were commonly assessed across multiple domains, including emotional, behavioural, social, and cognitive outcomes. When single domains were examined, these most often focused on emotional outcomes such as anxiety and depression. Interventions frequently employed therapeutic approaches such as cognitive behavioural therapy and psychoeducation, with content emphasizing emotion regulation, coping and problem-solving skills, and mental health literacy. Structural features varied in length and number of sessions, and many included scaffolded self-managed elements such as messaging or check-ins. Early childhood was underrepresented, with limited reporting of child outcomes for ages 0–4. Equity considerations were also limited, as many studies did not report race or ethnicity and sex and gender reporting was often binary or unspecified. Youth involvement in intervention design or consultation was uncommon.

Discussion:

This review provides an overview of the current landscape and identifies key gaps, including limited equity considerations, the underrepresentation of early childhood development, and minimal youth involvement. Clearer reporting of delivery structure and facilitation, stronger demographic reporting, and component-focused evaluation can support equitable, developmentally responsive scale-up.

Systematic Review Registration:

https://inplasy.com/inplasy-2024-9-0026/, INPLASY202490026.

1 Introduction

1.1 Children and youth mental health needs

Mental health conditions typically emerge early in life: two-thirds to three-quarters develop before the age of 24 (1), with a median onset at 18 years and a peak at 14.5 years (2). Early-onset conditions frequently persist into adulthood, emphasizing the importance of prevention and early intervention to equip children and youth with effective coping strategies and reduce the likelihood of long-term challenges (3). The global decline in youth mental health during and after the COVID-19 pandemic further highlights the urgent need for population-level supports (3). The pandemic also exposed critical limitations of traditional service systems and accelerated the adoption of digital approaches (4).

1.2 Digital mental health interventions (DMHIs)

Digital mental health interventions (DMHIs) use technologies such as apps, web-based platforms, and online programs to deliver prevention, treatment, and mental health support, depending on their intended purpose and design (5, 6). They include self-guided or facilitated programs, asynchronous and synchronous formats, blended models combining online and offline components, and tools such as serious games (digital games designed for therapeutic or educational purposes) and virtual reality. DMHIs are particularly appealing for young people, who are highly digitally connected (7, 8), and they can reduce barriers such as stigma, geography, and wait times (9, 10). However, these benefits are not equitably distributed: gaps in access to devices, reliable internet, and digital literacy mean that youth from low-income, rural, or historically marginalized communities remain underserved (9, 11). Without equity-focused design, DMHIs risk reinforcing rather than reducing disparities (12).

1.3 Equity and marginalization

In this review, digital marginalization refers to the social, economic, and structural conditions that constrain access to digital mental health resources and opportunities. These conditions are shaped by factors such as race, ethnicity, sex, gender, socioeconomic status (SES), geography, and culture (13). Children and youth who experience marginalization often face barriers to participation in digital interventions, including limited access to devices or reliable internet, lower levels of digital literacy, and programs that lack culturally responsive design and content (14, 15). Such inequities have significant implication for the reach and effectiveness of universal DMHIs. Greater systematic attention to equity is therefore needed to assess whether universal DMHIs are achieving population-level impact.

1.4 Tiers of service delivery and universal approaches

DMHIs can be situated within a tiered model of mental health service delivery (

16):

Tier 1 (Universal): Interventions offered to all children and youth, regardless of circumstances, with the goal of promoting health, strengthening resilience, and preventing the onset of mental health difficulties.

Tier 2 (Selective): Targeted supports for children and youth with elevated vulnerability or showing early signs of distress.

Tier 3 (Indicated/Clinical): Intensive, individualized interventions for young people with identifiable or diagnosable mental health conditions.

This review focuses on Tier 1 DMHIs. While universal approaches are designed to strengthen health and resilience, many studies nonetheless evaluate outcomes such as anxiety and depression symptoms. This reflects a conceptual tension between the promotion/prevention goals of universal interventions and the symptom-focused measures used in much of the existing evidence base.

1.5 Theoretical grounding

Universal DMHIs can be conceptually anchored in several complementary frameworks. Prevention science emphasizes early, population-wide strategies to reduce incidence of mental health challenges (

17). Developmental psychopathology highlights how mental health trajectories unfold across stages of growth (

18). Ecological systems theory situates child development within multiple interacting contexts (family, school, community, and culture) (

19). From this perspective, universal DMHIs have the potential to reduce emerging symptoms while simultaneously strengthening protective factors across development. For example, appropriate targets for Tier 1 DMHI would be:

1.6 Existing reviews and gaps

Prior reviews of school-based or digital mental health programs report mixed effects, with some interventions demonstrating modest benefits and others limited or no impact (24). However, most of the literature has focused on Tier 2 (selective) or Tier 3 (clinical) interventions for children and youth with elevated symptoms or diagnosed conditions (10, 25, 26).

Reviews that include universal interventions often analyze them alongside targeted or clinical programs, making it difficult to isolate Tier 1 effects. For example, Bergin et al. (27) synthesized preventive digital interventions but grouped universal and selective programs together, limiting conclusions about population-level delivery. Similarly, Liverpool et al. (28) reviewed digital health interventions broadly, without distinguishing universal from clinical tiers, and equity considerations were minimally addressed. More recently, Piers et al. (13) focused on socioeconomically and digitally marginalized youth, highlighting critical access gaps, but did not provide a systematic overview of the broader universal DMHI landscape.

Consequently, the scope, content, and delivery of universal (Tier 1) DMHIs remain poorly defined. Key questions about developmental coverage, outcome domains, and equity, including representation of younger children and marginalized populations, have not been systematically addressed. This scoping review extends prior work by (1) focusing exclusively on universal interventions, (2) situating them within developmental and theoretical frameworks, and (3) foregrounding equity and inclusion as central dimensions of the evidence base.

1.7 Aim of this review

This scoping review addresses limitations in prior work by systematically characterizing the peer-reviewed literature on universal (Tier 1) DMHIs for children and youth aged 0–18. The review examines five key domains:

Populations studied: Which developmental stages and demographic groups are represented?

Objectives and outcomes: What outcomes are targeted and how are they measured?

Intervention parameters: What are the key design and implementation features?

Content and approaches: Which therapeutic and conceptual foundations are used?

Delivery models: How are interventions facilitated and by whom?

By synthesizing evidence across these domains, this review clarifies the current landscape of universal DMHIs, identifies gaps in developmental and equity coverage, and provides a foundation for the design, implementation, and evaluation of future Tier 1 programs.

2 Methods

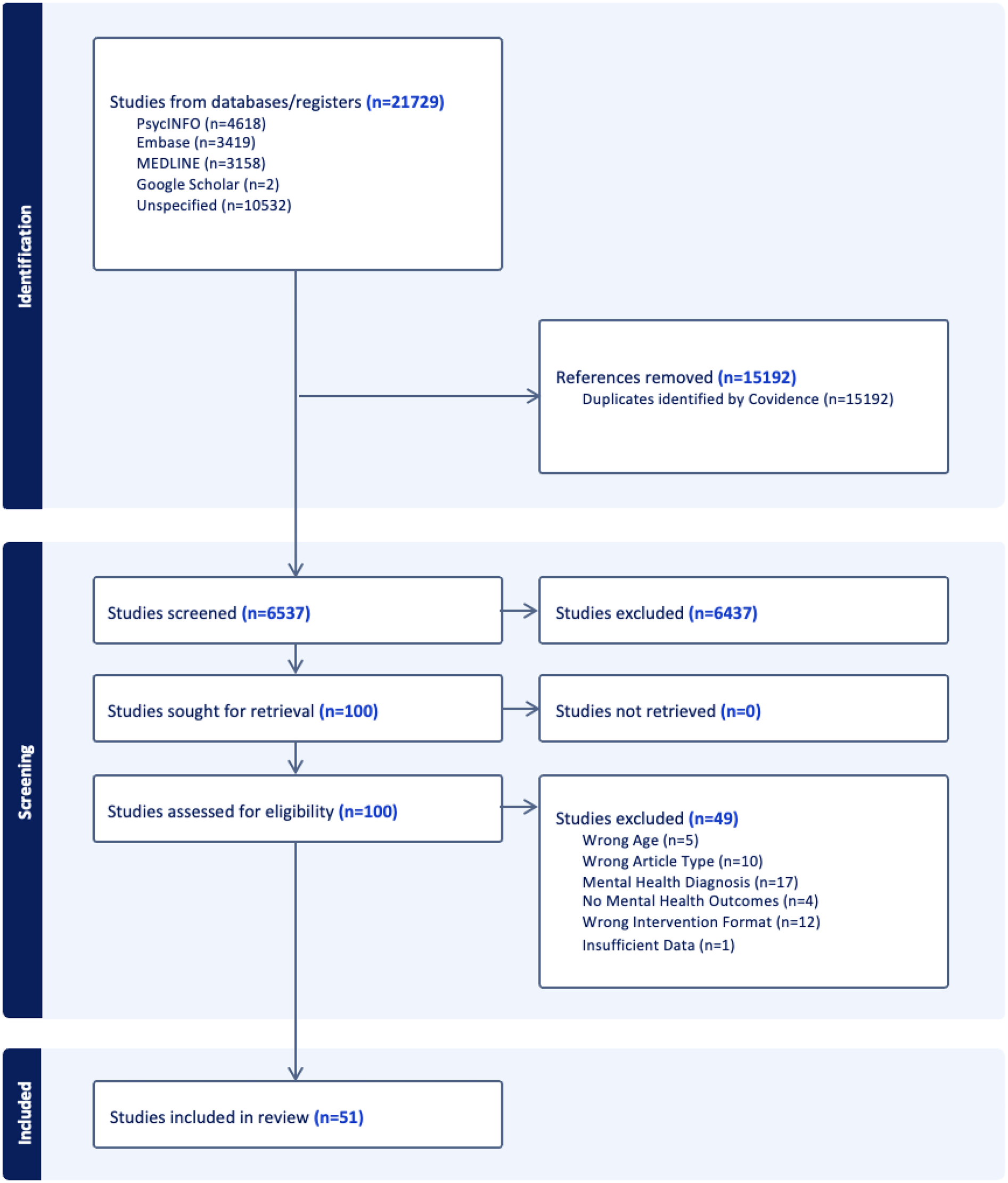

This review was prospectively registered on the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (INPLASY Protocol 6765). The conduct and reporting of the review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines (29). The completed PRISMA-ScR checklist is available in the Supplementary Materials, and a PRISMA flowchart summarizing the study selection is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1

PRISMA flowchart.

2.1 eligibility criteria

2.1.1 Types of sources

This review included full-text, peer-reviewed original research articles, as these represent the highest standard for evidence-based practice in health and social care. Non-peer-reviewed sources (e.g., book chapters, case studies, conference abstracts, and dissertations) were excluded.

2.1.2 Participants

Studies were eligible if the minimum or mean age of participants was between 0 and 18 years. Studies that included participants over 18 were still considered if the average age of the sample was approximately 18 years or younger. Studies were excluded if they focused exclusively on adults or did not specify participant age.

2.1.3 Mental health Status

Only studies involving non-clinical populations were included. Studies were excluded if they focused on participants who had been hospitalized for acute medical or psychiatric conditions (e.g., suicide attempt or cancer treatment) or had recently been discharged from such care.

2.1.4 Intervention format

Studies had to include a digital intervention. Eligible interventions were either virtual (delivered entirely online, without in-person components) or hybrid (integrating digital tools with in-person elements, such as school-based implementation). Studies that relied solely on in-person interventions without a digital component were excluded.

2.1.5 Measured outcomes

Studies were included if they measured at least one mental health outcome within the domains of emotional, behavioural, social, or cognitive. Studies that assessed only physiological measures without a corresponding mental health outcome were excluded. In this review, psychological outcomes were defined broadly to include:

Emotional (e.g., mood, affect, anxiety, depression)

Behavioural (e.g., conduct, coping actions)

Social (e.g., peer relationships, connectedness)

Cognitive (e.g., attention, executive function, problem-solving)

For each study, one outcome measure per domain (emotional, behavioural, social, cognitive) was selected for synthesis to support parsimony and future effect size synthesis. The decision was made to reduce heterogeneity between trials being synthesized, increase confidence in future syntheses, and prepare the dataset for subsequent meta-analysis. When more than one outcome per domain was reported, authors prioritized the most psychometrically valid measure. If multiple high-quality outcomes were reported, frequency of use amongst other included studies was examined. This approach also reduced redundancy, as studies that included several measures of the same construct (e.g., multiple anxiety scales) were represented only once per domain, preventing overweighting of particular outcomes or studies in the synthesis. Importantly, for each intervention, all outcome domains that were assessed were documented, even though only one measure per domain was carried forward into the synthesis.

2.1.6 Search strategy and data sources

A systematic search for DMHIs targeting psychological outcomes was created with a highly experienced academic librarian. The search process began with a preliminary scan of Google Scholar to identify key articles relevant to the three main components of the research question: universal scope, DMHIs, and children and youth. These initial articles informed the development of a comprehensive list of keywords, which were refined to ensure compatibility across databases.

The final search strategy was implemented in three major databases: MEDLINE, PsycInfo, and Embase. An example of the search terms used across these databases is provided in Supplementary Table S2. The initial search was conducted between June 26, 2024, and July 5, 2024. To capture newly published literature, an updated search using the same strategy was performed on January 6, 2025, covering studies published between July 3, 2024, and January 6, 2025.

2.1.7 Study selection

All search results were imported into Covidence, a reference management and screening tool, to facilitate de-duplication, title and abstract screening, full-text review, and data extraction. While many records were automatically categorized as database sources based on indexed journal information, a large proportion (n = 10,532) were labeled as “unspecified sources” due to missing metadata. This included manually uploaded references and records lacking identifiable source information.

Title and abstract screening was conducted by a four-person review team, with all records independently screened by two reviewers. Reliability screening was performed on a subset of studies (25% of the total sample) to assess consistency in screening decisions. Full-text articles deemed potentially relevant were uploaded to Covidence for further screening by two independent reviewers. Discrepancies in inclusion or exclusion decisions were resolved through weekly consensus meetings among the authorship team. Full-text data extraction was conducted using both Covidence and Excel, and always performed by two independent reviewers.

We also manually searched the reference lists of relevant excluded systematic reviews and conducted targeted handsearching of key journals and other sources likely to contain relevant studies. Inter-rater agreement for title and abstract screening ranged from 0.84 to 0.98, while agreement for full-text review ranged from 0.90 to 0.96, indicating an almost perfect agreement between reviewers (30).

2.1.8 Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted using Microsoft Excel, with categories initially adapted from the PICO framework: Population, Intervention, Comparators, and Outcomes (31). Variables selected for extraction (as reported above) were part of an iterative process as familiarity with the scope of literature deepened. Data extraction templates were piloted and revised to improve clarity and consistency between co-authors. Each article was independently extracted by two reviewers to improve accuracy and reliability.

2.1.9 Data synthesis

Descriptive statistics (e.g., frequencies, medians, and ranges) were used to summarize study characteristics. Data were presented in both tabular and graphical formats. Key variables synthesized included publication year, country of origin, study design, population demographics (e.g., age, marginalized status), DMHI characteristics (e.g., format, setting, facilitation), and mental health outcomes (e.g., domains, tools, reporting methods).

3 Results

3.1 Study selection and characteristics

A total of 21,729 studies were identified through the search strategy. After de-duplication and screening, 51 peer-reviewed studies on universal DMHIs for children and youth were included in the scoping review (Figure 1).

Across the 51 included articles, we identified 45 unique interventions (88%). Several programs were evaluated in more than one study and were therefore grouped together as intervention “families.” Specifically, SPARX/SPARX-R (32, 33), MoodGYM (34, 35), Hero (36, 37), Life-Fit-Learning/RISE (38, 39), Bite Back (40, 41), and OKmind (42, 43) were each evaluated in two separate articles. All other interventions were unique to a single article. Most studies were conducted in middle- to high-income countries (n = 49, 96%), primarily in North America (n = 12, 24%) and Australia (n = 12, 24%). Only two studies were conducted in low-income countries (44, 45). See Supplementary Table S1 for a summary of Study Characteristics of Universal DMHIs For Children and Youth.

All included studies were published since 2002, with the highest number published in 2024 (n = 10, 20%). The majority were published between 2021 and 2024 (n = 27, 53%). Study sample sizes ranged from 24 to 1,767 participants.

Most studies employed between-group designs while a notable minority used within group (i.e., repeated measures) designs to track changes within participants over time (n = 12, 24%). Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were the most common study design (n = 35, 69%), followed by non-randomized interventional studies (n = 17, 33%). Many studies also included follow-up assessments after the initial intervention period to examine long-term effects (n = 23, 45%), but the number and duration of follow-ups varied notably. Follow-up time periods included: immediate (within 1 month post-intervention, n = 2), 1–3 months post-intervention (n = 14), 4–6 months post-intervention (n = 7), and 12-months or beyond (n = 5).

Study quality was assessed for all included studies using appropriate tools based on study design. The Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) (46) tool was applied to RCTs, and the ROBINS-I tool (47) was used for non-RCTs. Among the 35 RCTs (69% of included studies), risk of bias was variable: 8 studies (22.9%) were rated as having low overall risk; 11 studies (31.4%) had some concerns; 16 studies (45.7%) had a high overall risk of bias. Common sources of bias included lack of participant and personnel blinding (performance bias), inadequate blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias), and issues related to attrition. Among the 16 non-RCTs (31%), most were pre-post single-group designs, with a smaller number using quasi-experimental comparisons. The ROBINS-I assessments indicated that: 14 studies (87.5%) had a serious overall risk of bias; 2 studies (12.5%) had a moderate risk. The most frequent concerns involved confounding, participant selection, and measurement of outcomes. Overall, the findings reflect a high degree of methodological variability and a substantial proportion of studies with notable sources of bias, particularly among non-randomized designs. This pattern reduces confidence in individual study findings and limits the certainty of conclusions that can be drawn from the current evidence base.

3.2 Results according to Key domains and research questions

-

Populations studied: which developmental stages and demographic groups are represented?

The features of target populations are summarized in Table 1. Of the 51 included studies, 45 (90%) targeted school-aged children and adolescents (5–18 years), while only four studies (8%) addressed preschool-aged children (0–4 years). These groupings were not predetermined based on developmental theory (e.g., 0–5, 6–12, 13–18) but instead reflected how populations were reported within the studies themselves. One study (2%) focused on children aged 4–7 years, which did not align neatly with either grouping (43).

Table 1

| Population features | No. of studies (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 5–18 | 46 (90) | |

| 0–4 | 4 (8) | |

| Mixed (4–7) | 1 (2) | |

| Participant Focus | ||

| Child-Youth Involved Only | 39 (76) | |

| Caregiver-Mediated | 9 (18) | |

| All Female | 5 (56) | |

| Predominantly Female | 3 (33) | |

| All Male | 1 (11) | |

| Caregiver-Involved | 3 (6) | |

| Unclear/Not-Reported | 2 (67) | |

| Predominantly Female | 1 (33) | |

| Sex | ||

| Sex Balance | ||

| Predominantly Female | 16 (31) | |

| Balanced | 15 (29) | |

| Predominantly Male | 9 (18) | |

| Unclear/Not-Reported | 6 (12) | |

| Exclusively Female | 3 (6) | |

| Exclusively Male | 2 (4) | |

| Sexual Orientation Reporting | ||

| Not-Reported | 48 (94) | |

| Reported | 3 (6) | |

| Gender | ||

| Gender Identity Reporting | ||

| Unclear/Not-Reported | 28 (55) | |

| Binary | 19 (37) | |

| Acknowledged Non-Binary Categories | 4 (8) | |

| Proportion of Racialized Participants | ||

| No racial data provided | 32 (63) | |

| 0%–24% | 10 (19) | |

| 75%–100% | 6 (12) | |

| 25%–49% | 3 (6) | |

| Most Prevalent Racialized Group | 14 (27) | |

| Latin American | 7 (50) | |

| Indigenous | 3 (22) | |

| Black | 2 (14) | |

| East Asian | 2 (14) | |

| Lived Experience with Marginalization | ||

| Non-Marginalized Communities | 45 (88) | |

| Historically Marginalized Communities | 6 (12) | |

Key features of target populations.

Across the included studies, 39 (76%) involved children and youth directly as participants, while a smaller proportion incorporated their caregivers, either through caregiver-mediated or caregiver-involved interventions. Caregiver-mediated interventions were delivered directly to parents or caregivers with the intention of influencing child outcomes (42, 45, 48–54). All interventions targeting children aged 0–4 years fell into this category (42, 45, 49, 50). Within the subset of caregiver-mediated interventions (n = 9, 18%), caregiver biological sex was reported as exclusively female in 5 studies (56%), predominantly female in 3 (33%), and exclusively male in 1 (11%). Caregiver-involved interventions (n = 3, 6%) included structured parent-child interaction components alongside child-focused programming (55–57). In these studies, caregiver biological sex was most often unclear or not reported (n = 2, 67%), with one study (33%) identifying caregivers as predominantly female (57).

Reporting on the biological sex of child and youth participants was also extracted. Sixteen studies (31%) reported predominantly female participants, 15 (29%) reported a balanced sex distribution, and 9 (18%) reported predominantly male participants. Six studies (12%) did not report or were unclear, 3 (6%) included only female participants, and 2 (4%) included only male participants. In terms of gender identity: 19 studies (37%) used binary categories (male/female), often conflating gender identity with biological sex; 4 (8%) acknowledged gender diversity beyond the binary (e.g., non-binary or transgender identities); and 28 (55%) did not specify how gender was defined or did not report it. Sexual orientation was rarely reported among caregivers or children/youth: 3 studies (6%) reported it, whereas 48 (94%) did not report.

To assess diversity within study samples, participants were also categorized according to the proportion of racialized individuals reported from a local perspective (i.e., populations considered racialized within the country where the study was conducted). Racial and cultural demographics were inconsistently reported overall: 32 studies (63%) provided no racial data. Among the 19 studies (37%) that did, most reported samples with 0%–24% racialized participants (n = 10, 19%), followed by 75%–100% (n = 6, 12%), and 25%–49% (n = 3, 6%). Of these 19, only 14 specified the most prevalent racialized group. Within this subset, the most commonly reported populations were Latin American (n = 7, 50%), Indigenous (n = 3, 22%), Black (n = 2, 14%), and East Asian (n = 2, 14%), together representing 100% of the 14 studies that reported such details.

Representation from historically marginalized communities was further assessed based on whether studies explicitly targeted these populations (e.g., interventions designed for participants with low SES status or specific racial or cultural identities). Most studies did not explicitly focus on marginalized populations (

n= 45, 88%). A smaller proportion (

n= 6, 12%) reported including participants who experience systemic barriers. Within this subset, areas of marginalization included racialized and ethnically diverse youth (

n= 3), low-income populations (

n= 3), caregivers in low-resource settings (

n= 2), and Indigenous communities (

n= 1). Several interventions addressed overlapping forms of disadvantage, such as race and economic status. For example, studies included Latinx sexual minority youth (

56), Black and biracial adolescent girls from low-income urban schools (

58), and low-income Latino and African American adolescents (

59). Other studies targeted economically disadvantaged adolescents more broadly (

60), caregivers of young children in Zambia and Tanzania (

45), and Inuit youth in remote Nunavut communities (

32).

Objectives and outcomes: what outcomes are targeted and how are they measured?

summarizes the target objectives and outcomes of the included studies. Nineteen studies (37%) were primarily prevention-focused, 18 (35%) were promotion-focused, and 14 (28%) addressed both aims. Prevention interventions were defined as those designed to reduce the onset or escalation of symptoms (e.g., teaching thought challenging to decrease worry). Promotion interventions were defined as those aiming to enhance positive functioning (e.g., improving social skills or help-seeking). Some interventions explicitly combined promotion and prevention aims, such as programs that taught skills for making friends while also including distortion identification strategies to prevent fear of negative evaluation (

61).

Table 2

| Outcome features | No. of studies (%) |

|---|---|

| Objective | |

| Prevention | 19 (37) |

| Promotion | 18 (35) |

| Both (Promotion & Prevention) | 14 (28) |

| Outcomes | |

| Multiple | 29 (57) |

| Emotional | 14 (27) |

| Behavioural | 4 (8) |

| Social | 3 (6) |

| Cognitive | 1 (2) |

| Reporting | |

| Self-report | 35 (69) |

| Caregiver-report or teacher-report | 9 (17) |

| Combination of self- and caregiver-/school- reports | 7 (14) |

Key features of target objectives and outcomes.

Interventions targeted a range of psychological outcomes, including emotional (e.g., how participants feel), behavioural (e.g., how participants act), social (e.g., how participants connect with others), and cognitive (e.g., how participants think or solve problems). Most studies assessed multiple outcome domains (n = 29, 57%). Fourteen studies (27%) focused solely on emotional outcomes, four (8%) on behavioural outcomes, three (6%) on social outcomes, and one (2%) exclusively on cognitive outcomes (44).

All but two studies employed validated measures, defined as standardized tools that have undergone psychometric testing for reliability and validity, such as the Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) (62) or the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) (63). Two studies also included additional unvalidated, study-specific instruments, developed for the intervention and not independently validated. Examples include Chillemi et al.'s (64) questionnaire on coping strategies for cyberbullying and Lang et al.'s (59) Computeen Computer Skills Inventory for assessing digital skills.

Self-report was the most common reporting method (

n= 35, 69%), where participants provided their own feedback after the intervention. Caregiver or teacher report was less common (

n= 9, 17%), though notably, all four interventions delivered to children aged 0–4 relied exclusively on caregiver reports. A smaller number of studies used a combination of self- and caregiver/teacher reporting (

n= 7, 14%).

Intervention parameters: what are the key design and implementation features?

The characteristics of intervention parameters, including format, design, and structure, are summarized in

Table 3. The majority of studies utilized hybrid formats (

n= 27, 53%), where a digital intervention was supplemented by an in-person component (e.g., students accessing an online program with teacher facilitation at school). This was followed by fully virtual interventions (

n= 20, 39%) and a small number of studies that included both hybrid and virtual intervention arms (

n= 4, 8%). Among hybrid DMHIs, the in-person component most frequently took place in school settings (

n= 28, 90%).

Table 3

| Parameter features | No. of studies (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Format | ||

| Hybrid | 27 (53) | |

| Virtual | 20 (39) | |

| Mixed (Hybrid + Virtual Arms) | 4 (8) | |

| Design | ||

| Online Program | 24 (47) | |

| App | 9 (17) | |

| Virtual Communication | 6 (12) | |

| Virtual Communication + Website | 6 (12) | |

| Video Game | 3 (6) | |

| Website | 2 (4) | |

| Virtual Reality | 1 (2) | |

| Structure | ||

| Independent Work | 23 (45) | |

| Group-Based & Independent Work | 15 (29) | |

| Group-Based & Independent Work & One-to-One | 6 (12) | |

| Independent Work & One-to-One | 5 (10) | |

| Group-Based | 2 (4) | |

| Youth Involvement in Intervention Design | ||

| Youth Involvement | 8 (16) | |

| Youth-Consulted/User-Informed | 5 (10) | |

| Youth Co-Design | 3 (6) | |

Key features of intervention parameters.

Most interventions were online programs (n = 24, 47%), typically delivered through platforms or portals. This was followed by apps (n = 9, 17%), standalone software applications designed for mobile devices or computers (e.g., meditation apps). Some interventions used virtual communication tools (n = 6, 12%), such as video conferencing or chat platforms for real-time interaction, while others combined virtual communication with websites (n = 6, 12%) to provide additional resources, modules, or educational content. Fewer interventions relied solely on websites (n = 2, 4%) or incorporated video game elements (n = 3, 6%). Only one study implemented virtual reality as the primary intervention format (65).

Intervention structure varied across studies. Structure refers to the format through which participants engaged with intervention content, independent of who facilitated delivery. Nearly half of the studies (n = 23, 45%) used independent work, where participants completed modules or activities on their own, sometimes supplemented with asynchronous check-ins. Fifteen studies (29%) used a combined format of independent work plus group-based sessions, allowing participants to complete self-directed activities alongside scheduled group discussions. Six studies (12%) implemented a multi-modal structure, integrating independent, group-based, and one-to-one sessions. In five studies (10%), the structure was independent work plus one-to-one sessions, where participants engaged in self-directed tasks and also attended individualized sessions with a facilitator. The least common structure was group-based only (n = 2, 4%), consisting of structured discussions or activities without a self-directed component.

In contrast to structure, facilitation was also examined. Facilitation (self-led, facilitator-led, or both-led) indicates who provided guidance or oversight. For example, an intervention may have an independent structure yet be “both-led” if participants complete modules independently after receiving facilitator instruction or check-ins.

Eight studies (16%) reported involving youth in the design of interventions. In five studies (10%), young people were consulted or informed through activities such as surveys, focus groups, or usability testing, where their input contributed to refining the interventions. Three studies (6%) reported youth co-design, in which young people partnered more directly in creating elements of the content, structure, or delivery features. Overall, the small number of studies involving youth highlights a substantial gap in participatory design within universal DMHIs.

Content and approaches: what therapeutic and conceptual foundations are used?

The characteristics of the interventions varied across studies, as summarized in

Table 4. Regarding the number of sessions, most interventions without scaffolding included 6–9 sessions (

n= 15, 29%) or 10 or more sessions (

n= 12, 23%). Shorter interventions with 1–5 sessions and no scaffolding appeared less frequently (

n= 8, 16%). Several studies used a

scaffolded self-managedformat, which involved a defined number of structured sessions or modules, along with supplementary support elements. These supports often included asynchronous check-ins, WhatsApp or SMS messages, discussion groups, or app-based nudges designed to maintain engagement, answer questions, or reinforce learning. For example, six studies (12%) included scaffolded self-management alongside 6–10 structured sessions, three studies (6%) combined 2–5 sessions with ongoing support, and two studies (4%) paired a single core session with additional communication. In contrast, fully self-managed programs (

n= 5, 10%) allowed participants to access the intervention entirely on their own, at their preferred time and pace, without any additional support.

Table 4

| Intervention features | No. of studies (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of Sessions | |

| 6–9 No Scaffolding | 15 (29) |

| 10+ No Scaffolding | 12 (23) |

| 1–5 No Scaffolding | 8 (16) |

| Scaffolded Self-Managed + 6–10 sessions | 6 (12) |

| Fully Self-Managed | 5 (10) |

| Scaffolded Self-Managed + 2–5 sessions | 3 (6) |

| Scaffolded Self-Managed + 1 session | 2 (4) |

| Duration of Intervention in Hours | |

| Scaffolded Self-Managed (7–14 h) | 10 (20) |

| 7–14 No Scaffolding | 10 (20) |

| 1–6 No Scaffolding | 9 (18) |

| Fully Self-Managed | 9 (18) |

| 15+ No Scaffolding | 6 (12) |

| Scaffolded Self-Managed (1–6 h) | 5 (10) |

| 0–1 No Scaffolding | 2 (4) |

| Therapeutic Approach | |

| Cognitive Behavioural Therapies | 27 (53) |

| Psychoeducation | 14 (27) |

| Other (Peer Support & Storytelling) | 4 (8) |

| Behavioural Therapies | 4 (8) |

| Mindfulness | 2 (4) |

| Intervention Content *studies featured a range of intervention content |

|

| Emotion Regulation | 44 (86) |

| Coping & Problem Solving Skills | 38 (75) |

| Mental Health Literacy | 23 (45) |

| Social Skills | 12 (24) |

| Parenting Skills | 6 (12) |

| Attention/Focus/Executive Functioning | 2 (4) |

Key features of intervention examined.

Each study may have employed multiple types of content.

Program duration also varied. Many interventions were estimated to last between 7 and 14 h, whether through structured content delivery (n = 10, 20%) or scaffolded self-managed formats (n = 10, 20%), where added features such as messaging or peer chat contributed to total engagement time. Nine studies (18%) reported durations of 1–6 h, including scaffolded formats (n = 5, 10%), while fully self-managed programs also commonly fell within this range (n = 9, 18%). Fewer programs were longer (15 + h; n = 6, 12%) or very brief (under 1 h; n = 2, 4%) without scaffolding.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapies (CBT) were the most widely used therapeutic approach (n = 27, 53%), typically combining cognitive strategies (e.g., thought restructuring) with behavioural techniques (e.g., goal-setting, exposure). Psychoeducational approaches (n = 14, 27%) focused on increasing awareness of mental health and self-care strategies. A smaller number of studies used behavioural therapies alone (n = 4, 8%), while others employed mindfulness-based approaches (n = 2, 4%) or peer-support and storytelling methods (n = 4, 8%), including digital storytelling and peer-led discussions.

Intervention content addressed a broad range of skill areas. Emotion regulation was the most frequently targeted area (

n= 44, 86%), with strategies designed to help participants understand, express, and manage emotions. Coping and problem-solving skills (

n= 38, 75%) were also prominent, supporting youth in handling stress and navigating challenges. Mental health literacy was addressed in nearly half of the studies (

n= 23, 45%), aiming to build understanding, reduce stigma, and encourage help-seeking. Fewer interventions emphasized social skills (

n= 12, 24%), with content focused on promoting prosocial behaviours. Parenting skills (

n= 6, 12%) were also included in some programs to support caregivers in fostering positive relationships and responsive caregiving. Only two interventions (

n= 2, 4%) explicitly targeted attention, focus, or executive functioning through attention regulation practices and task initiation strategies.

Delivery models: how are interventions facilitated and by whom?

summarizes the key features of who facilitated the intervention. Interventions were categorized as self-led, facilitator-led, or both-led. Self-led interventions allowed participants to independently access on-demand content, such as mobile apps or video games. Facilitator-led interventions involved real-time guidance from a trained mental health professional, such as in virtual therapy sessions or structured group programs. Both-led interventions included an initial facilitator-guided phase before transitioning to independent engagement. The majority of interventions were both-led (

n= 35, 69%), while fewer were fully self-led (

n= 12, 23%) or solely facilitator-led (

n= 4, 8%).

Table 5

| Delivery features | No. of studies (%) |

|---|---|

| Delivery | |

| Both-led (self- and facilitator-led) | 35 (69) |

| Self-led | 12 (23) |

| Facilitator-led | 4 (8) |

| Facilitator Type | |

| Research Personnel | 11 (29) |

| Registered Mental Health Professional | 7 (18) |

| Teachers | 6 (16) |

| Registered Mental Health Professionals & Child & Youth Workers & Counselors | 5 (13) |

| Non-Registered Mental Health Professional | 4 (11) |

| Not Described | 2 (5) |

| Child & Youth Workers & Counselors | 2 (5) |

| Mixed | 1 (3) |

| Facilitator Involvement | |

| Teaching/Counseling | 26 (67) |

| Non-Involved Resource | 13 (33) |

Key features of intervention delivery.

Of the 51 studies included in this review, 39 (76%) involved a facilitator in some fashion. Research personnel were the most frequently involved facilitators (n = 11, 29%), consisting of researchers or academic staff without clinical qualifications. Registered mental health professionals (n = 7, 18%), including licensed psychologists, psychiatrists, and clinical social workers, were also commonly involved. Teachers (n = 6, 16%) played a significant role in several studies, often integrating mental health interventions into their school curriculum. Some studies used multidisciplinary teams (n = 5, 13%), where licensed mental health professionals worked alongside child and youth workers or counselors. Other studies relied on non-registered mental health professionals (n = 4, 11%), such as peer supporters, wellness coaches, or unlicensed counselors. A small number of studies (n = 2, 5%) did not specify who facilitated the intervention, while another small number of studies (n = 2, 5%) were exclusively facilitated by child and youth workers and counselors. In addition, one study involved a mix of teachers and non-registered mental health professionals (66).

The level of facilitator involvement varied across studies. In most cases, facilitators were engaged in teaching or counseling (n = 26, 67%). This included providing direct instruction, delivering therapeutic guidance, or offering structured support through both group and one-on-one sessions. Their roles often involved leading psychoeducational sessions, conducting mental health counseling, and facilitating discussions and interactive activities. In contrast, some facilitators served as non-involved resources (n = 13, 33%). In these cases, facilitators did not actively guide the intervention but instead provided Supplementary Materials or background support. Their involvement included being available to answer questions, overseeing access to digital resources, or offering general guidance without directly interacting with participants.

4 Discussion

This scoping review describes the current state of the evidence base on universal (Tier 1) digital mental health interventions (DMHIs) for children and youth aged 0–18 years. While prior reviews have explored DMHIs for young people aged 10–24 years (67) or combined universal, selective/at-risk, and clinical samples (27), most existing scoping reviews focus either on adults (68) or on children and youth within clinical populations (69). By focusing exclusively on universal DMHIs for children and youth, this review identifies patterns in target populations, outcomes, intervention design/structure, and delivery, and highlights developmental and equity gaps that warrant attention, especially given the rapid expansion of DMHI research following the pandemic.

Across included studies, 90% focused on participants aged 5–18 years, with comparatively limited attention to early childhood (0–4 years). All 0–4 interventions were caregiver-mediated, with caregivers as the primary users and reporters of child outcomes. The gap identified here concerns the scarcity of evaluated universal DMHIs that report child outcomes for ages 0–4, rather than the absence of caregiver-facing tools. Several features constrain inference in this subset: outcomes were exclusively caregiver-reported (introducing reporter/expectancy bias), child measures were heterogeneous and not always developmentally sensitive to the 0–4 period, and studies rarely specified caregiver role parameters (training, intensity, fidelity), limiting reproducibility and scale estimates. Virtual platforms are not merely convenient alternatives but can serve as lifelines for caregivers who face barriers to attending in-person services (e.g., travel, scheduling, childcare). Although broader literature links early family supports and responsive caregiving to socioemotional development (42, 45, 49, 50) and highlights the plasticity and vulnerability of early development (70), the current Tier 1 evidence base for digitally delivered, caregiver-mediated programs with child outcomes remains thin and inconsistently described.

Most interventions paired a digital tool (e.g., app or online module) with some in-person support (e.g., teacher or facilitator activities), indicating that a hybrid delivery format was most studied. Interventions typically comprised six or more sessions (∼7–14 h) and often incorporated scaffolded self-management (e.g., asynchronous check-ins, prompts, SMS/WhatsApp reminders). Few studies isolated the effects of scaffolding, session intensity, or duration, so the optimal dose and format for universal programs remain unclear. To interpret and implement Tier 1 DMHIs, two orthogonal dimensions require clear reporting: structure and facilitation. This distinction explains why independent work was the most common structure (45%) even though self-led was less frequent as a facilitation mode (23%). For example, a hybrid program may have an independent structure (participants complete modules on their own) while facilitation is both-led (self-directed use paired with in-person sessions and support available during online use). Accordingly, future studies should clearly report both dimensions and, where possible, evaluate variations in facilitation and scaffolding to inform practical guidance on time-on-task and delivery formats for Tier 1 interventions.

Most studies assessed multiple psychological domains (emotional, behavioural, social, cognitive), whereas single-domain studies most often emphasized emotional symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depression). A further issue is measurement fit. Many studies used symptom-oriented clinical scales that are well validated for treatment samples but can be insensitive in universal populations (e.g., floor effects, low variance) and do not capture promotion targets (skills, functioning, literacy). Promotion outcomes are typically assessed with capability- or performance-focused tools (e.g., coping or emotion-regulation skills, social competence, executive function, mental health literacy), which differ conceptually and psychometrically from symptom scales. In the synthesis, all domains assessed were recorded; when multiple tools indexed the same domain within a study, one validated measure per domain per study was selected to enhance comparability and reduce redundancy, an approach that may nevertheless privilege symptom measures over asset-focused constructs. It is recommended to pair symptom scales with developmentally appropriate, population-referenced measures and to report simple distributional checks (e.g., proportion at minimum scores, variance).

Only 12% of studies explicitly targeted marginalized populations, and 63% did not report racial/ethnic demographics. Sex and gender reporting showed similar limitations: 37% used binary gender categories, 55% did not specify their approach or did not report gender, and only 8% acknowledged non-binary gender identities. Sex balance was typically reported for child/youth participants, but often within binary frames; sexual orientation was rarely reported (6%). These gaps extended to caregiver data in the few caregiver-focused studies. These gaps constrain inferences about who is reached and who benefits, and hinder cultural adaptation. To support equitable implementation at scale, the field needs standardized demographic reporting (race/ethnicity, gender identity, sex where appropriate, sexual orientation, socioeconomic indicators, geography). Programs must be culturally and linguistically adapted, include strategies to address digital divides (e.g., low-bandwidth modes, offline functionality, device access supports), and attend to gender identity and sexual orientation diversity. Few studies documented such adaptations, highlighting a missed opportunity to design DMHIs that are both inclusive and scalable. Attention to cultural barriers, such as mistrust of mental health systems, stigma, and lack of content in users' first languages, remains particularly underdeveloped.

Youth perspectives were rarely incorporated into intervention development, with only 16% of studies involving young people through consultation or co-design. This limited engagement raises concerns about whether interventions adequately reflect the realities, preferences, and digital practices of their intended users. Co-design with youth is critical, given the central role of trust and relevance in sustaining use of DMHIs (71, 72). Similarly, participatory and peer components were used infrequently. Here, peer refers to adolescents who share salient characteristics with the target users (e.g., age, school context, community) and who take structured roles within the intervention — for example, peer mentors, moderators, or coaches who facilitate discussions, model skills, or provide support. Expanding these participatory and peer-support elements represents an opportunity to improve acceptability, especially for groups historically underserved and underrepresented by traditional designs.

Interventions most commonly drew on CBT, followed by basic psychoeducation, with content frequently emphasizing emotion regulation, coping/problem-solving, and mental health literacy. Fewer interventions targeted social skills, parenting practices, or attention/executive functioning domains relevant to social learning and self-regulation. This matters in light of evidence that pandemic-related isolation disrupted early social-cognitive development, particularly in lower-SES groups (73), and that rising digital engagement may reduce opportunities to practice interpersonal skills (74). Despite widespread youth engagement with interactive media, video games (8%) and virtual reality (2%) were rarely used as standalone Tier 1 interventions. Testing these modalities, especially when combined with participatory and peer-based elements, may improve engagement and relevance.

Within a tiered service model, universal Tier 1 DMHIs are low-intensity, high-reach supports designed for non-clinical populations. By strengthening foundational skills across developmental stages, they can reduce emerging symptoms while promoting protective factors, and create low-friction pathways to selective and indicated supports (Tier 2/3) through education, screening, and referral prompts (16). Importantly, children and youth are not a homogeneous group, and not all will have the access, readiness, or interest needed to benefit from digital tools. DMHIs should therefore be seen as one component of a broader, layered system of promotion and prevention rather than a one-size-fits-all solution.

Although many studies employed randomized designs, methodological variability and persistent risk-of-bias concerns, particularly in non-randomized trials, temper confidence in individual findings. Clearer outcome specification, developmentally appropriate measurement, full demographic reporting, and rigorous implementation descriptions will improve interpretability and the practical utility of future universal DMHI evidence.

5 Conclusion

This scoping review synthesizes evidence on universal Tier 1 digital mental health interventions for children and youth aged 0–18. Hybrid models are common, but therapeutic approaches, delivery structures, and target outcomes remain heterogeneous. Three cross-cutting gaps warrant action. Developmental coverage is uneven, especially for ages 0–4 where caregiver-mediated delivery is appropriate but child-reported outcomes are rarely collected. Equity and inclusion are under addressed, with inconsistent demographic reporting, limited cultural or linguistic adaptation, and infrequent youth participation. Reporting and evaluation practices also constrain interpretability and planning for scale, including unclear separation of delivery structure and facilitation in many papers and limited testing of format, dose, scaffolding, or immersive and interactive modalities.

Next steps align with these gaps. Expand early-childhood work using developmentally sensitive child measures within caregiver-mediated models. Advance digital health equity by increasing representation, standardizing demographic reporting, and addressing access barriers. Compare hybrid and fully virtual formats to isolate the active components of in-person support. Broaden therapeutic approaches beyond CBT to include peer support, storytelling, and other youth-aligned modalities. Target promotion outcomes such as social skills and attention regulation alongside symptoms. Invest in the development and rigorous testing of immersive and interactive tools, for example gamified programs and virtual reality, to assess feasibility, engagement, and impact.

These findings also have practical implications. Educators can integrate independent-structure programs into classroom routines with brief facilitator touchpoints and provisions for digital inclusion. Clinicians and school mental health teams can position universal DMHIs as a first step in stepped care, linking brief digital engagement to simple screening and timely referral. Policymakers and funders can set minimum expectations for demographic and implementation reporting, support trials that pinpoint the delivery components most responsible for engagement and outcomes, and resource co-design and cultural and linguistic adaptation. Implemented in this way, universal DMHIs can be developmentally responsive, inclusive, and scalable within a layered system of promotion and prevention.

5.1 Limitations

This review has several limitations. We restricted inclusion to peer-reviewed publications, which excludes grey literature and ongoing or unpublished programs. Classifying interventions as “universal” was constrained by variable reporting of participant characteristics and scope. The age criterion (mean age 0–18) excluded transitional-age youth 18–25 who are often included in broader youth mental health frameworks. Comparability was further limited by heterogeneity in measures and outcomes, frequent reliance on caregiver-reported outcomes in 0–4 studies, incomplete demographic reporting, and inconsistent descriptions of implementation details, including facilitator training, delivery schedule, and intervention fidelity/adherence.

Despite these constraints, the review provides a systematic overview of how universal DMHIs are being conceptualized and implemented for children and youth. Closing gaps in early-childhood evidence and digital health equity remains essential for scalable and equitable uptake.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

KD: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. OB: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. HH: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. ArL: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. AnL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. RC: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. RP: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. We would like to thank the Jackman Foundation and York University (funding dedicated to DIVERT Mental Health collaboration, a CIHR funded Health Research Training Platform) for funding that supported this research project. This project was also supported by funds through a York Research Chair to the senior author (RPR).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fdgth.2025.1665975/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Kessler RC Berglund P Demler O Jin R Merikangas KR Walters EE . Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2005) 62(6):593–602. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

2.

Solmi M Radua J Olivola M Croce E Soardo L Salazar de Pablo G et al Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry. (2022) 27(1):281–95. 10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7

3.

Mental Health Research Canada. A generation at risk: The state of youth mental health in Canada (2024). Available online at:https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f31a311d93d0f2e28aaf04a/t/6733a10075f9613ae5a2c5c2/1731436803015/Report+-+A+Generation+at+Risk+The+State+of+Youth+Mental+Health+in+Canada.pdf(Accessed September 25, 2025).

4.

Moreno MA D’Angelo J . Digital media interventions for adolescent mental health. In: NesiJTelzerEHPrinsteinMJ, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Digital Media Use and Mental Health. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2022). p. 291–312.

5.

Pineda BS Mejia R Qin Y Castro J Delgadillo LG Muñoz RF . Updated taxonomy of digital mental health interventions: a conceptual framework. mHealth. (2023) 9:28. 10.21037/mhealth-23-6

6.

Gan DZ McGillivray L Han J Christensen H Torok M . Effect of engagement with digital interventions on mental health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Digit Health. (2021) 3:764079. 10.3389/fdgth.2021.764079

7.

Rideout V Robb MB . Social Media, Social Life: Teens Reveal Their Experiences. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense Media (2018).

8.

Radovic A Gmelin T Stein BD Miller E . Depressed adolescents’ positive and negative use of social media. J Adolesc. (2017) 55:5–15. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.002

9.

Torous J Myrick KJ Rauseo-Ricupero N Firth J . Digital mental health and COVID-19: using technology today to accelerate the curve on access and quality tomorrow. JMIR Ment Health. (2020) 7(3):e18848. 10.2196/18848

10.

Hollis C Falconer CJ Martin JL Whittington C Stockton S Glazebrook C et al Annual research review: digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems—a systematic and meta-review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2017) 58(4):474–503. 10.1111/jcpp.12663

11.

Kohli K Jain B Patel TA Eken HN Dee EC Torous J et al The digital divide in access to broadband internet and mental healthcare. Nat Ment Health. (2024) 2(1):88–95. 10.1038/s44220-023-00176-z

12.

van Dijk JAGM . The Deepening Divide: Inequality in the Information Society. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications (2005).

13.

Piers R Williams JM Sharpe H . Can digital mental health interventions bridge the ‘digital divide’ for socioeconomically and digitally marginalised youth? A systematic review. Child Adolesc Ment Health. (2023) 28:90–104. 10.1111/camh.12620

14.

Katz VS . What it means to be “under-connected” in lower-income families. J Child Media. (2017) 11(2):241–4. 10.1080/17482798.2017.1305602

15.

Ellis DM Draheim AA Anderson PL . Culturally adapted digital mental health interventions for ethnic/racial minorities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2022) 90(10):717–33. 10.1037/ccp0000759

16.

School Mental Health Ontario. Think in tiers about student mental health (2024). Available online at:https://smho-smso.ca/school-administrators/think-in-tiers-about-student-mental-health/(Accessed September 18, 2025).

17.

Biglan A Flay BR Embry DD Sandler IN . The critical role of nurturing environments for promoting human well-being. Am Psychol. (2012) 67:257–71. 10.1037/a0026796

18.

Cicchetti D . Socioemotional, personality, and biological development: illustrations from a multilevel developmental psychopathology perspective on child maltreatment. Annu Rev Psychol. (2016) 67:187–211. 10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033259

19.

Bronfenbrenner U Morris PA . The bioecological model of human development. In: DamonWLernerRM, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology. Vol. 1, Theoretical Models of Human Development. 6th ed.Hoboken (NJ): Wiley (2007). p. 793–828.

20.

Morris AS Silk JS Steinberg L Myers SS Robinson LR . The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Soc Dev. (2007) 16:361–88. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x

21.

Masten AS Coatsworth JD . The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments: lessons from research on successful children. Am Psychol. (1998) 53:205–20. 10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.205

22.

Eccles JS . The development of children ages 6 to 14. Future Child. (1999) 9:30–44. 10.2307/1602703

23.

Steinberg L . Age of Opportunity: Lessons from the New Science of Adolescence. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (2014).

24.

Das JK Salam RA Lassi ZS Khan MN Mahmood W Patel V et al Interventions for adolescent mental health: an overview of systematic reviews. J Adolesc Health. (2016) 59:S49–60. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.020

25.

Grist R Porter J Stallard P . Mental health Mobile apps for preadolescents and adolescents: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. (2017) 19:e176. 10.2196/jmir.7332

26.

Garrido S Millington C Cheers D Boydell K Schubert E Meade T et al What works and what doesn't work? : a systematic review of digital mental health interventions for depression and anxiety in young people. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:759. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00759

27.

Bergin AD Vallejos EP Davies EB Daley D Ford T Harold G et al Preventive digital mental health interventions for children and young people: a review of the design and reporting of research. NPJ Digit Med. (2020) 3:133. 10.1038/s41746-020-00339-7

28.

Liverpool S Mota CP Sales CMD Čuš A Carletto S Hancheva C et al Digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems: a systematic and meta-review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2020) 29:1559–79. 10.1007/s00787-019-01327-4

29.

Tricco AC Lillie E Zarin W O’Brien KK Colquhoun H Levac D et al PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850

30.

McHugh ML . Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). (2012) 22:276–82. 10.11613/BM.2012.031

31.

Joanna Briggs Institute. JBI Reviewer’s Manual: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. Adelaide: The Joanna Briggs Institute (2014).

32.

Bohr Y Rawana JS McGregor T Bayoumi AM Wilansky P Domene JF et al Evaluating the utility of a psychoeducational serious game (SPARX) in protecting inuit youth from depression: pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Serious Games. (2023) 11:e38493. 10.2196/38493

33.

Perry Y Werner-Seidler A Calear AL Mackinnon A King C Scott J et al Preventing depression in final year secondary students: school-based randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. (2017) 19:e369. 10.2196/jmir.8241

34.

Calear AL Christensen H Mackinnon A Griffiths KM O’Kearney R . The YouthMood project: a cluster randomized controlled trial of an online cognitive behavioral program with adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2009) 77(6):1021–32. 10.1037/a0017391

35.

Lillevoll KR Vangberg HC Griffiths KM Waterloo K Eisemann MR . Uptake and adherence of a self-directed internet-based mental health intervention with tailored e-mail reminders in senior high schools in Norway. BMC Psychiatry. (2014) 14:14. 10.1186/1471-244X-14-14

36.

Mesurado B Distefano MJ Robiolo G Richaud MC . The Hero program: development and initial validation of an intervention program to promote prosocial behavior in adolescents. J Soc Pers Relatsh. (2019) 36:2566–84. 10.1177/0265407518793224

37.

Mesurado B Resett S Oñate ME Vanney C . Hero: a virtual program for promoting prosocial behaviors toward strangers and empathy among adolescents: a cluster randomized trial. J Soc Pers Relatsh. (2022) 39:2641–57. 10.1177/02654075221083227

38.

Waters AM Sluis RA Ryan KM Usher W Farrell LJ Donovan CL et al Evaluating the implementation of a multi-technology delivery of a mental health and wellbeing system of care within a youth sports development program during the COVID-19 pandemic. Behav Change. (2023) 40:199–210. 10.1017/bec.2022.17

39.

Waters AM Sluis RA Usher W Farrell LJ Donovan CL Modecki KL et al Reaching young people in urban and rural communities with mental health and wellbeing support within a youth sports development program: integrating in-person and remote modes of service delivery. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. (2024) 56:1446–56. 10.1007/s10578-023-01647-1

40.

Manicavasagar V Horswood D Burckhardt R Lum A Hadzi-Pavlovic D Parker G . Feasibility and effectiveness of a web-based positive psychology program for youth mental health: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. (2014) 16:e140. 10.2196/jmir.3176

41.

Subotic-Kerry M Braund TA Gallen D Li SH Parker BL Achilles MR et al Examining the impact of a universal positive psychology program on mental health outcomes among Australian secondary students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. (2023) 17:70. 10.1186/s13034-023-00623-w

42.

Zhang X Li Y Wang J Mao F Wu L Huang Y et al Effectiveness of digital guided self-help mindfulness training during pregnancy on maternal psychological distress and infant neuropsychological development: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. (2023) 25:e41298. 10.2196/41298

43.

Liu S Fang H Zou L Li Q Wang H Han ZR . Online mindfulness-based group intervention for young Chinese children: effectiveness of the OKmind program in attention and emotion regulation. Mindfulness (NY). (2024) 15:3095–106. 10.1007/s12671-024-02416-4

44.

Hassen HM Tusa BS Mekonen EG Alemayehu DG Azanaw MM Chanie MG et al Effectiveness and implementation outcome measures of mental health curriculum intervention using social media to improve the mental health literacy of adolescents. J Multidiscip Healthc. (2022) 15:979–97. 10.2147/JMDH.S361212

45.

Skeen S Laurenzi CA Gordon S du Toit S Tomlinson M Dua T et al Using WhatsApp support groups to promote responsive caregiving, caregiver mental health and child development in the COVID-19 era: a randomised controlled trial of a fully digital parenting intervention. Digit Health. (2023) 9:20552076231203893. 10.1177/20552076231203893

46.

Sterne JAC Savović J Page MJ Elbers RG Blencowe NS Boutron I et al Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J. (2019) 366:l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898

47.

Sterne JAC Hernán MA Reeves BC Savović J Berkman ND Viswanathan M et al ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Br Med J. (2016) 355:i4919. 10.1136/bmj.i4919

48.

DeGarmo DS Jones JA . Fathering through change (FTC) intervention for single fathers: preventing coercive parenting and child problem behaviors. Dev Psychopathol. (2019) 31:1801–11. 10.1017/S0954579419001019

49.

McRury JM Zolotor AJ . A randomized, controlled trial of a behavioral intervention to reduce crying among infants. J Am Board Fam Med. (2010) 23:315–22. 10.3122/jabfm.2010.03.090142

50.

Morawska A Sanders MR . Self-administered behavioural family intervention for parents of toddlers: effectiveness and dissemination. Behav Res Ther. (2006) 44:1839–48. 10.1016/j.brat.2005.11.015

51.

Sim WH Fernando LMN Jorm AF Rapee RM Lawrence KA Mackinnon AJ et al A tailored online intervention to improve parenting risk and protective factors for child anxiety and depression: medium-term findings from a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. (2020) 277:814–24. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.019

52.

Wolchik SA Sandler IN Winslow EB Porter MM Tein JY . Effects of an asynchronous, fully web-based parenting-after-divorce program to reduce interparental conflict, increase quality of parenting and reduce children’s post-divorce behavior problems. Fam Court Rev. (2022) 60:474–91. 10.1111/fcre.12620

53.

Wong RS Yu EY Wong TW Fung CS Choi CS Or CK et al Development and pilot evaluation of a mobile app on parent-child exercises to improve physical activity and psychosocial outcomes of Hong Kong Chinese children. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:1544. 10.1186/s12889-020-09655-9

54.

Zulkefly NS Dzeidee Schaff AR Zaini NA Mukhtar F Dahlan R . A pilot randomized control trial on the feasibility, acceptability, and initial effects of a digital-assisted parenting intervention for promoting mental health in Malaysian adolescents. Digit Health. (2024) 10:20552076241249572. 10.1177/20552076241249572

55.

Sun Y Wang MP Ho SY Chan CS Man PK Kwok T et al A smartphone app for promoting mental well-being and awareness of anxious symptoms in adolescents: a pilot cluster randomized controlled trial. Games Health J. (2022) 11:393–402. 10.1089/g4h.2021.0215

56.

Estrada Y Lozano A Tapia MI Fernández A Harkness A Scott D et al Familias con orgullo: pilot study of a family intervention for latinx sexual minority youth to prevent drug use, sexual risk behavior, and depressive symptoms. Prev Sci. (2024) 25:1079–90. 10.1007/s11121-024-01724-4

57.

Ohashi S Urao Y Fujiwara K Koshiba T Ishikawa SI Shimizu E . Feasibility study of the e-learning version of the “journey of the brave:” a universal anxiety-prevention program based on cognitive behavioral therapy. BMC Psychiatry. (2024) 24:806. 10.1186/s12888-024-06264-3

58.

Neal-Barnett A Stadulis R Payne N Thomas AJ Ritchwood T Hill S . Evaluation of the effectiveness of a musical cognitive restructuring app for black inner-city girls: survey, usage, and focus group evaluation. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2019) 7:e11310. 10.2196/11310

59.

Lang JM Waterman J Baker BL . Computeen: a randomized trial of a preventive computer and psychosocial skills curriculum for at-risk adolescents. J Prim Prev. (2009) 30:587–603. 10.1007/s10935-009-0186-8

60.

Gefter L Piatt J Kuwabara SA Zazueta C Cavanagh J Saw A et al Assessing health behaviour change and comparing remote, hybrid and in-person implementation of a school-based health promotion and coaching program for adolescents from low-income communities. Health Educ Res. (2024) 39:2971–312. 10.1093/her/cyae015

61.

DeSmet A Bastiaensens S Van Cleemput K Poels K Vandebosch H Malliet S et al The efficacy of the friendly attac serious digital game to promote prosocial bystander behavior in cyberbullying among young adolescents: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Comput Hum Behav. (2018) 78:336–47. 10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.011

62.

Reynolds CR Richmond BO . Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) Manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services (1985).

63.

Achenbach TM . Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington (VT): University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry (1991).

64.

Chillemi K Abbott JAM Austin DW Knowles AA . A pilot study of an online psychoeducational program on cyberbullying that aims to increase confidence and help-seeking behaviors among adolescents. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2020) 23:253–6. 10.1089/cyber.2019.0081

65.

Hadley W Houck CD Barker D Senocak N Wyman C Brown LK . Moving beyond role-play: evaluating the use of virtual reality to teach emotion regulation for the prevention of adolescent risk behavior within a randomized pilot trial. J Pediatr Psychol. (2019) 44:425–35. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsy092

66.

Ron Nelson J Marchand-Martella N Martella RM . Maximizing student learning: the effects of a comprehensive school-based program for preventing problem behaviors. J Emot Behav Disord. (2002) 10:136–48. 10.1177/10634266020100030201

67.

Baka E Tan YR Wong BL Xing Z Yap P. Scoping review of digital interventions for the promotion of mental health and prevention of mental health conditions for young people. Oxf Open Digit Health. (2025) 3:oqaf005. 10.1093/oodh/oqaf005

68.

Lipschitz JM et al Digital mental health interventions for depression: scoping review of user engagement. J Med Internet Res. (2022) 24:e39204. 10.2196/39204

69.

Danese A Martsenkovskyi D Remberk B Khalil MY Diggins E Keiller E et al Scoping review: digital mental health interventions for children and adolescents affected by war. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2025) 64:226–48. 10.1016/j.jaac.2024.02.017

70.

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Excessive Stress Disrupts the Architecture of the Developing Brain = Working Paper 3. Cambridge, MA: Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2005). Available online at:https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/working-paper/wp3/(Accessed September 25, 2025).

71.

Torous J Nicholas J Larsen ME Firth J Christensen H . Clinical review of user engagement with mental health smartphone apps: evidence, theory and improvements. Evid Based Ment Health. (2018) 21:116–9. 10.1136/eb-2018-102891

72.

Hagen P Collin P Metcalf A Nicholas M Rahilly K Swainston N . Participatory Design of Evidence-based Online Youth Mental Health Promotion, Intervention and Treatment. Melbourne (AUS): Young and Well Cooperative Research Centre (2012).

73.

Scott RM Nguyentran G Sullivan JZ . The COVID-19 pandemic and social cognitive outcomes in early childhood. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:28939. 10.1038/s41598-024-80532-w

74.

Effective School Solutions. The decline of teenage social skills (2024). Available online at:https://effectiveschoolsolutions.com/teenage-social-skills/(Accessed September 26, 2025).

Summary

Keywords

universal, Tier 1, digital mental health intervention (DMHI), child and youth, e-mental health, equity

Citation

Di Pierdomenico K, Bucsea O, Hashemi H, Leguia A, Lovegrove A, Cribbie R and Pillai Riddell R (2025) Universal digital mental health interventions for children and youth: a scoping review. Front. Digit. Health 7:1665975. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2025.1665975

Received

14 July 2025

Accepted

28 October 2025

Published

17 November 2025

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Andreas Balaskas, University College Dublin, Ireland

Reviewed by

Markus Boeckle, University Hospital Tulln, Austria

Amanda Fitzgerald, University College Dublin (UCD), Ireland

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Di Pierdomenico, Bucsea, Hashemi, Leguia, Lovegrove, Cribbie and Pillai Riddell.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Kaitlin Di Pierdomenico katiemdp@yorku.ca Rebecca Pillai Riddell rpr@yorku.ca

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.