- Weill Cornell Medicine, Cornell University, New York, NY, United States

Background: Medications, while essential therapeutic tools in modern healthcare, carry the inherent risk of causing adverse drug events (ADEs) that can result in significant morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs. Despite substantial research efforts in this domain, the majority of ADEs remain undetected due to reliance on voluntary reporting systems and inadequate surveillance mechanisms. Consequently, the true scope and impact of ADEs are likely far greater than currently recognized.

Objective: To examine the role of shared clinical decision support (SCDS) in reducing adverse drug events and enhancing patient safety outcomes through systematic integration of clinical decision support systems with shared decision-making frameworks.

Methods: We conducted a narrative review of literature published up to June 2025, utilizing validated patient safety frameworks to identify contextual factors, systemic challenges, and evidence-based strategies that influence adverse drug event occurrence and prevention.

Results: Multiple interconnected factors contribute to ADE susceptibility, including healthcare provider competencies (inadequate monitoring, symptom recognition failures), clinical environment characteristics (technology workarounds, equipment complexity), pharmacy system factors (high-risk medication storage, limited pharmacist involvement), and patient-specific variables (polypharmacy, multimorbidity, age-related physiological changes). Critical risk determinants include provider fatigue and burnout, inadequate monitoring protocols, medication administration errors, and systemic communication failures. Successful implementations require multifaceted approaches integrating health information technology components, stakeholder engagement, customized clinical decision rules, and continuous quality improvement processes.

Conclusions: Shared clinical decision support represents a paradigm shift toward patient empowerment, enabling active patient participation in healthcare decisions while leveraging technology-enhanced clinical guidance. The most promising approach to ADE elimination involves a comprehensive integration of educational initiatives, human factors engineering, robust shared clinical decision support systems, and multidisciplinary collaborative care models.

Introduction

Medications constitute indispensable therapeutic tools in contemporary healthcare, serving as primary interventions for treating diverse pathological conditions, managing symptomatic presentations, and optimizing patient outcomes across various clinical settings (1). However, the pharmaceutical landscape presents a complex duality, as these same therapeutic agents can precipitate adverse drug events (ADEs) ranging from minor discomfort to life-threatening complications (2). The intricate nature of modern drug therapy, particularly in patients with multiple comorbidities and complex medication regimens, exponentially increases ADE susceptibility. Addressing this critical safety challenge represents a fundamental priority in advancing patient safety standards and healthcare quality metrics.

Adverse drug events (ADEs) are broadly defined as injuries resulting from medical interventions related to drugs, encompassing medication errors, adverse drug reactions, allergic responses, and overdose incidents (3). This broad definition captures the multifaceted nature of drug-related harm and acknowledges both preventable and non-preventable adverse outcomes. ADEs impose a significant burden on healthcare systems worldwide, with wide-ranging implications for patient safety, clinical outcomes, and resource utilization. In the U.S., ADEs contribute to approximately 2 million hospital admissions annually, resulting in extended lengths of stay and substantially increased healthcare expenditures (4). Additionally, ADEs account for approximately 1 million emergency department visits and 3.5 million physician office consultations each year, representing a significant strain on healthcare resources and capacity (3, 5). Certain demographic groups demonstrate heightened susceptibility to ADEs, with elderly populations representing a particularly vulnerable cohort (6). Research indicates that ADE prevalence ranges from 4.8% to 37% among elderly patients with cognitive disorders, reflecting the complex interplay between aging physiology, polypharmacy, and comorbid conditions (7). A study evaluating ADEs through combined patient self-reporting and clinical review found that 78% of individuals over 70 years of age had experienced at least one ADE within a six-month period, highlighting the pervasive nature of this safety concern in geriatric populations (8).

Despite these alarming statistics, the true prevalence of ADEs likely represents a significant underestimation due to systematic underreporting and limitations in current detection methodologies. Healthcare systems predominantly rely on voluntary reporting mechanisms and error tracking systems, which capture only a fraction of actual events. Conservative estimates suggest that merely 10%–20% of medication errors are formally reported, indicating that the actual scope of ADEs may be five to ten times greater than currently documented (9). The consequences of ADEs extend far beyond immediate clinical presentations, encompassing significant morbidity and mortality outcomes. Beyond the direct health impacts, ADEs precipitate increased healthcare utilization patterns, elevated treatment costs, and diminished functional status for affected patients (7). The economic burden includes direct costs associated with additional treatments, extended hospitalizations, and emergency interventions, as well as indirect costs related to lost productivity and reduced quality of life.

The severity of harm associated with ADEs exists along a continuum, ranging from minimal or no detectable harm to severe morbidity and mortality. Research examining over 1,000 prescribing errors revealed that 11.5% were likely to have caused patient harm, while 19.3% required additional monitoring interventions (10). This spectrum includes “near miss” events that, while not causing immediate harm, possess the potential for significant adverse outcomes if left unaddressed. These near-miss events are estimated to occur in 5%–10% of hospitalized patients but remain substantially understudied in current literature (11).

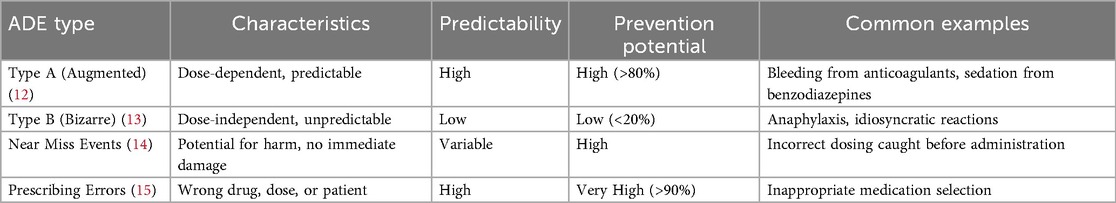

Table 1 demonstrates the classification and characteristics of adverse drug events. ADEs can be systematically classified into two primary categories: Type A (augmented) and Type B (bizarre) reactions (12). Type A reactions are dose-dependent and predictable, frequently resulting from medication errors such as incorrect dosing, inappropriate frequency, or excessive duration of therapy. These errors are largely preventable through implementation of proper prescribing protocols and enhanced monitoring systems (13). Type A reactions are commonly associated with frequently prescribed medications and often involve prescribing errors, making their reduction a critical clinical priority (14). Type B reactions are unpredictable and dose-independent, typically involving allergic or idiosyncratic responses. While these reactions are more challenging to prevent due to their unpredictable nature, proper patient history taking, allergy documentation, and genetic testing (where applicable) can reduce their incidence (15).

Prescribing errors represent a significant contributor to Type A ADEs, occurring at multiple stages of the medication-use process, including prescribing, transcription, dispensing, and administration phases. Common prescribing errors include inappropriate medication selection, incorrect dosing calculations, and failure to consider patient-specific factors such as renal or hepatic function, age-related physiological changes, and concurrent medications. A study found that nearly 94% of hospitalized patients experienced at least one prescribing error during their admission, underscoring the pervasive nature of this problem (16). Medication administration errors constitute another major cause of ADEs, occurring when incorrect medications are administered, correct medications are given in wrong doses or via inappropriate routes, or medications are administered at incorrect times (17). Contributing factors include clinical interruptions during medication preparation and administration, similar packaging or labeling of different pharmaceutical products, and increasingly complex medication regimens that challenge healthcare providers' cognitive capacity and attention to detail (18).

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted systematic searches of PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases for literature published up to June 2025. Search terms included combinations of: “adverse drug events,” “medication errors,” “clinical decision support,” “shared decision-making,” “health information technology,” “CPOE,” “patient safety,” “prescribing errors,” and “medication reconciliation.” Boolean operators (AND, OR) were used to combine search terms. We supplemented database searches with manual review of reference lists from key articles and citation tracking of seminal publications in the field.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included peer-reviewed research articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and clinical guidelines published in English that addressed: (1) epidemiology and risk factors for adverse drug events; (2) health information technology interventions for ADE prevention; (3) clinical decision support system implementation and effectiveness; (4) shared decision-making frameworks and patient engagement strategies; (5) geriatric-specific medication safety concerns; and (6) multidisciplinary approaches to medication safety. We excluded conference abstracts, editorials without original data, and studies focusing exclusively on specific therapeutic areas (e.g., oncology) without broader applicability to general ADE prevention.

Synthesis approach

We utilized the World Health Organization's Conceptual Framework for the International Classification for Patient Safety (19) as an organizing structure to categorize findings and identify key themes related to ADE occurrence and prevention. Data extraction focused on: (1) risk factors contributing to ADEs across patient, provider, and system levels; (2) types and characteristics of SCDS interventions; (3) implementation strategies and barriers; (4) reported clinical and safety outcomes; and (5) economic implications. We synthesized findings narratively, organizing evidence by thematic areas including risk assessment, intervention strategies, implementation frameworks, and outcomes evaluation. Conceptual frameworks were developed to integrate evidence across studies and illustrate relationships between risk factors, interventions, and outcomes.

Shared clinical decision support

Shared Clinical Decision Support (SCDS) represents an innovative healthcare delivery model that integrates clinical decision support systems (CDSS) with shared decision-making (SDM) frameworks to enhance patient care quality and safety outcomes. This approach embodies a collaborative paradigm where healthcare professionals and patients work synergistically to make clinical decisions that align with patient values, preferences, and lifestyle considerations while incorporating evidence-based clinical guidelines and best practices. The fusion of CDSS capabilities with SDM principles creates a powerful framework for addressing complex clinical scenarios, particularly in medication management where the risk of ADEs is substantial (20). This integration leverages health information technology to provide real-time, evidence-based recommendations while ensuring that patient perspectives and preferences remain central to the decision-making process.

The role of health information technology in SCDS

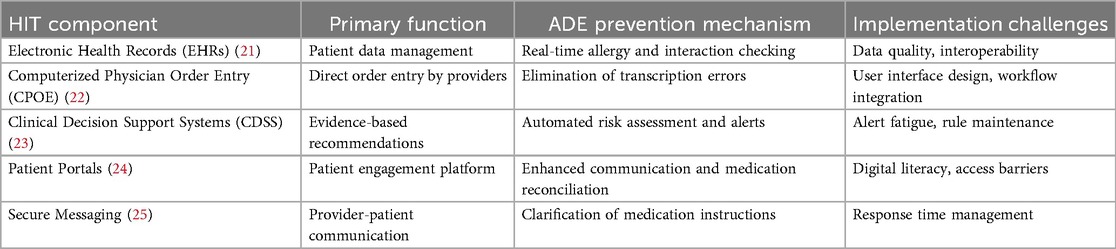

Health Information Technology (HIT) is a cornerstone of SCDS, providing the necessary tools and infrastructure to support both clinicians and patients in making informed decisions. Table 2 illustrates the key components of health information technology in SCDS.

Electronic health records (EHRs): the foundation of digital healthcare

EHRs serve as digital repositories containing complete patient information, including medical histories, current medications, documented allergies, laboratory results, imaging studies, and clinical notes (26). EHRs facilitate seamless information sharing among healthcare providers, ensuring continuity of care and reducing the risk of errors attributable to incomplete or inaccurate information (27, 28). The integration of EHRs with CDSS enables real-time alerts and clinical reminders about potential drug interactions, allergy contraindications, and other critical clinical considerations at the point of care (21).

Computerized physician order entry (CPOE): streamlining prescription processes

CPOE systems enable healthcare providers to enter medication orders and clinical instructions directly into computerized systems, significantly reducing prescribing errors by eliminating handwriting legibility issues, transcription errors, and incomplete order problems (29). When integrated with CDSS capabilities, CPOE systems provide immediate feedback regarding potential drug interactions, dosage errors, and clinical contraindications, creating a robust safety net that reduces ADE risk at the point of prescribing (30).

Clinical decision support systems (CDSS): intelligent clinical guidance

CDSS represent sophisticated software applications designed to assist healthcare providers in clinical decision-making processes. These systems analyze patient data from EHRs and other sources to generate evidence-based recommendations, alerts, and clinical reminders (31). Advanced CDSS capabilities include allergy alerts when contraindicated medications are ordered, drug interaction warnings when potentially harmful combinations are prescribed, and alternative medication suggestions based on patient-specific factors such as age, weight, renal function, and hepatic status (23).

Patient portals: empowering patient engagement

Patient portals are secure, web-based platforms that enable patients to access their health information, communicate with healthcare providers, and actively participate in their care management (24). Through these platforms, patients can review their medication lists, access laboratory results, review visit summaries, and receive educational materials and decision aids (32, 33). Patient portals facilitate shared decision-making by providing patients with relevant clinical information and enabling active participation in treatment discussions and decisions (33).

Secure messaging systems

Secure messaging platforms allow patients and healthcare providers to communicate electronically while maintaining privacy and security standards (25). These systems can be utilized to address medication-related questions, clarify treatment instructions, and provide follow-up care guidance (34). Secure messaging enhances SCDS implementation by ensuring that patients maintain direct communication access with their healthcare teams, helping prevent misunderstandings and medication-related errors (35).

Implementing shared clinical decision support in clinical practice

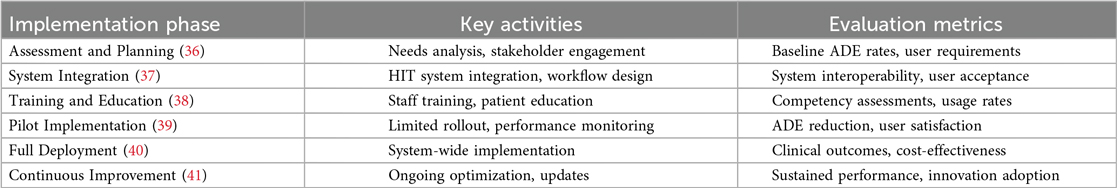

Successful SCDS implementation requires planning, multi-stakeholder collaboration, and continuous evaluation processes. The implementation framework should address technical requirements, workflow integration, user training, and performance monitoring to ensure optimal outcomes. Table 3 demonstrates the SCDS implementation framework.

Identifying priority clinical areas

The initial step in SCDS implementation involves identifying clinical areas where the intervention can achieve maximum impact (42). This process typically involves analyzing ADE surveillance data to identify high-risk medications, vulnerable patient populations, and clinical settings with elevated risk profiles. Implementing SCDS in chronic disease management, such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease, where medication regimens are complex and ADE risk is elevated, often provides substantial benefits.

Stakeholder engagement strategies

Successful SCDS implementation requires engagement of all stakeholders, including healthcare providers, patients, pharmacists, information technology professionals, and administrative leadership (36). Stakeholder engagement should begin early in the implementation process to ensure that diverse perspectives and requirements are incorporated into system design and deployment strategies (43). This engagement can be facilitated through focus groups, stakeholder surveys, and regular collaborative meetings (36).

System integration requirements

SCDS must be seamlessly integrated with existing health IT infrastructure, including EHRs and CPOE systems, to ensure that clinical decision support is readily available during routine clinical workflows. Integration involves ensuring smooth data flow between systems and making CDSS alerts and recommendations easily accessible to healthcare providers during patient care activities (37).

CDSS rule development and customization

The effectiveness of SCDS depends substantially on the quality and clinical relevance of CDSS rules and algorithms (44). These rules should be based on current clinical guidelines and evidence-based practices while being customized to meet the specific needs of the clinical environment and patient population (44). For example, CDSS rules for anticoagulation management should incorporate patient-specific factors such as age, renal function, and potential drug interactions to provide optimal safety and efficacy recommendations (45).

Education and training programs

Education and training programs are essential components of SCDS implementation (38). Healthcare providers require training on effective utilization of SCDS tools and integration of shared decision-making principles into clinical practice. Training curricula should address CDSS alert interpretation, patient portal utilization for shared decision-making, and effective patient engagement strategies in treatment discussions (46).

Performance evaluation and continuous improvement

Ongoing evaluation is crucial for ensuring that SCDS achieves its intended objectives and for identifying opportunities for system optimization. Evaluation methodologies include ADE rate analysis, healthcare provider and patient satisfaction surveys, and system usability assessments (47). Based on evaluation findings, SCDS can be continuously refined to address identified issues and optimize effectiveness.

Barriers and challenges

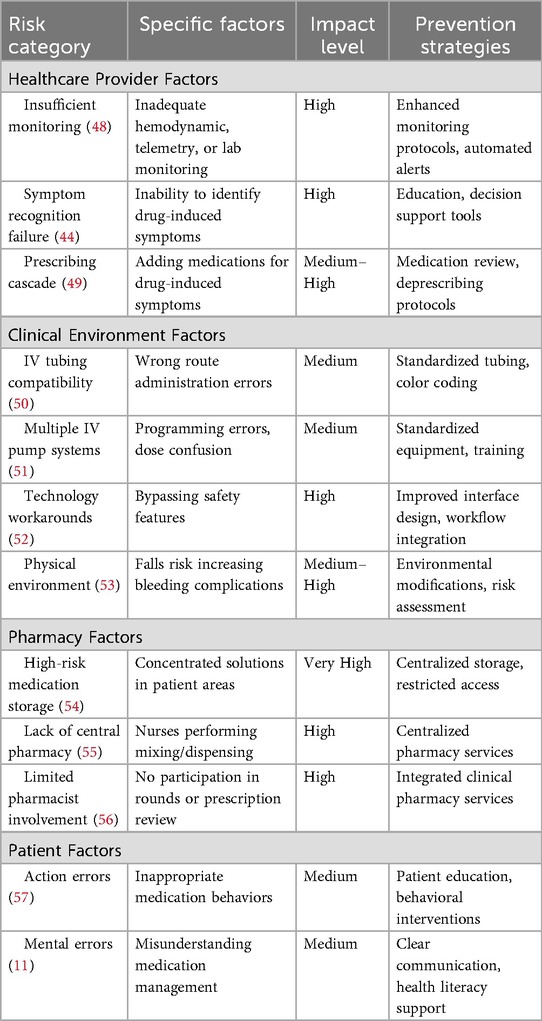

Systemic contributors to adverse drug events

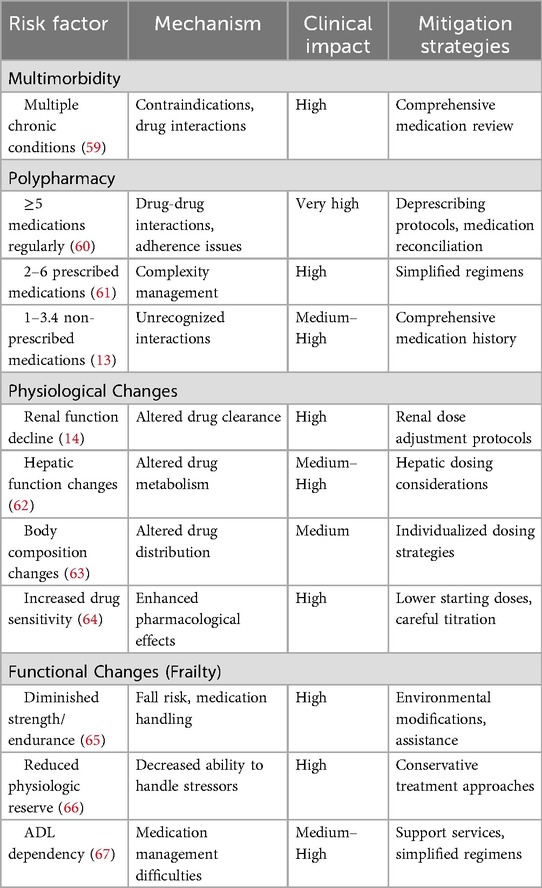

The healthcare environment contains numerous interconnected factors that contribute to ADE occurrence, many of which are not unique to specific patient populations. Understanding these systemic challenges is essential for developing effective prevention strategies. Table 4 presents the risk factors for adverse drug events.

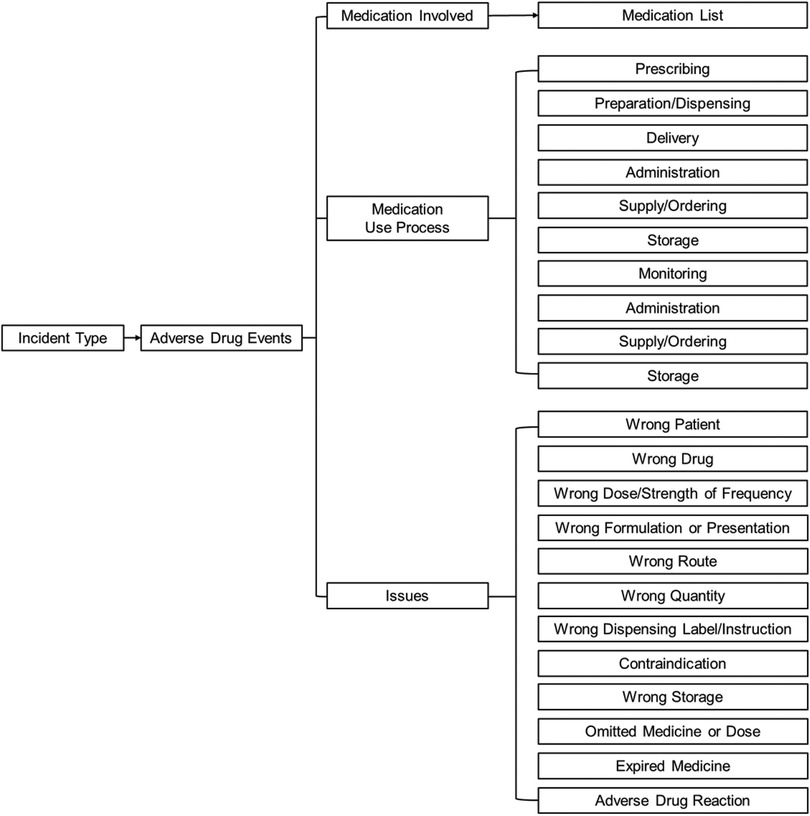

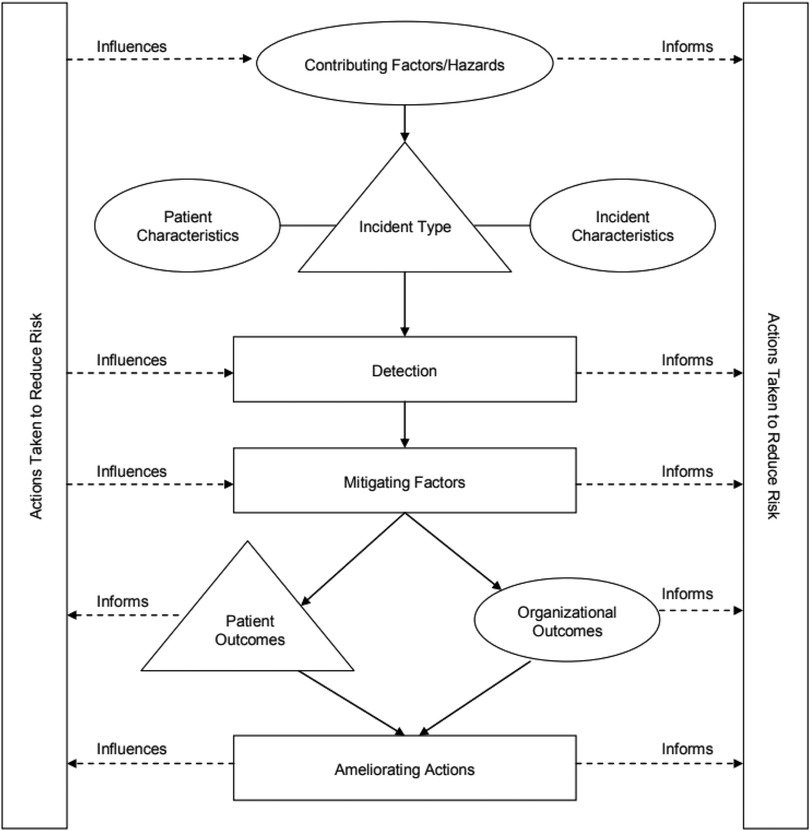

We applied the Conceptual Framework for the International Classification for Patient Safety (Figure 1) that was developed by the World Health Organization (19) to understand the risk factors of ADE. This framework was designed to enable categorization of patient safety information using standardized sets of concepts with agreed definitions, preferred terms and the relationships between them being based on an explicit domain ontology (e.g., ADE). The framework has been be a genuine convergence of international perceptions of the main issues related to patient safety and has facilitated the description, comparison, measurement, monitoring, analysis and interpretation of information to improve patient care (19).

Figure 1. The conceptual framework for the international classification of patient safety (19).

Healthcare provider-related factors

Healthcare provider factors primarily encompass insufficient clinical monitoring and inadequate recognition of medication-related symptoms. Insufficient monitoring—whether involving hemodynamic parameters, cardiac telemetry, or laboratory values—can affect both physicians and nursing staff, potentially leading to ADEs (58). Research indicates that inadequate monitoring contributes to 17.6% of preventable ADEs, highlighting the critical importance of systematic surveillance protocols (48). The inability to recognize symptoms potentially related to medication use represents another significant risk factor. When healthcare providers cannot identify symptoms that may indicate an ADE, this creates a dangerous cycle involving continued medication use, symptom progression, and increased patient harm. Often, the failure to distinguish drug-induced symptoms from underlying medical conditions leads to the addition of additional medications, a phenomenon known as the “prescribing cascade,” which increases the risk of drug-drug interactions and additional ADEs (49).

Clinical environment challenges

The clinical environment itself can significantly increase patient ADE risk. Universal compatibility of intravenous therapy tubing represents a common source of medication errors, typically involving wrong-route administration (50). The utilization of multiple different IV pump systems with varying programming requirements for different medications can also increase ADE risk through programming errors and dose confusion. Complex or cumbersome technology at the human-machine interface may lead providers or nurses to develop workarounds for frustrating obstacles, which can ultimately result in medication errors and ADEs (52). Additionally, the physical environment can place frail patients at increased risk for falls, which subsequently increases the risk of bleeding complications from anticoagulant medications or antiplatelet agents (53).

Pharmacy system factors

Certain pharmacy-related factors are recognized as significant ADE risk contributors. The storage of high-risk medications, such as concentrated potassium solutions, in patient care areas has demonstrated increased ADE risk (11). The absence of a centralized pharmacy capable of providing ready-to-use medication units increases ADE risk by requiring nursing staff to perform medication mixing and dispensing activities, introducing additional opportunities for errors.

Some clinical settings and units lack pharmacist participation in clinical rounds when medications are typically prescribed and when prescribing errors are most likely to occur. Some healthcare facilities utilize pharmacists only to review high-risk medication prescriptions rather than implementing prescription verification processes. While this approach may appear cost-effective, it creates the risk of missing critical errors with traditionally lower-risk but frequently prescribed medications.

Patient-Related factors

Patients themselves can contribute to increased ADE risk in both inpatient and outpatient settings. Research demonstrates that 25% of ADEs within a large health maintenance organization were attributed to patient errors. These patient errors can be categorized as action errors (inappropriate patient behaviors) or mental errors (errors involving patient thought processes) (57). Action errors might include patients consuming alcohol while taking contraindicated medications despite receiving appropriate counseling. Mental errors might involve patients continuing to take their home medications while hospitalized, mistakenly assuming they are responsible for their own medication management during hospitalization and that continuing all home medications is safe (11).

Geriatric-specific risk factors for adverse drug events

While the aforementioned risk factors affect all patient populations, geriatric patients face additional, population-specific risks that significantly increase their ADE susceptibility compared to younger adults (13). The association between advanced age and increased ADE rates stems from multiple interconnected factors, including increased comorbidity burden, polypharmacy, physiological changes, and functional decline or frailty. Table 5 demonstrates the geriatric-specific risk factors for adverse drug events.

Multimorbidity and comorbidity impact

As patients age, accumulating comorbidities significantly increase ADE risk. Geriatric patients represent a population with higher disease burden and more complex health conditions that may create relative or absolute contraindications to specific medications (68). The prevalence of this risk factor is remarkable: systematic reviews indicate that 95.1% of patients over 65 years in primary care settings have multimorbidity (69). Research by Jose et al. identified multiple disease states as one of the two most common predisposing factors for ADEs in hospital settings (70).

Polypharmacy complications

Polypharmacy, defined most commonly as the regular use of five or more medications, represents the other most common predisposing factor for ADEs in geriatric populations. Older adults face the greatest risk for polypharmacy, as medication lists typically expand with advancing age, leading to increased potential for medication interactions and adverse effects when new medications are prescribed. Research indicates that patients over 65 years use an average of two to six prescribed medications, in addition to one to 3.4 non-prescribed medications, which are often not identified or considered in clinical settings (13). Multiple studies have established links between polypharmacy and adverse events in geriatric patients (13). Kojima et al. demonstrated that geriatric patients taking five to eight medications had significantly increased risk for ADE-related hospitalizations and fall-related injuries (71).

Physiological changes and pharmacological implications

Age-related physiological changes represent critical factors in geriatric ADE risk when not appropriately considered in prescribing decisions. These changes include alterations in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, increased sensitivity to commonly used medications (particularly central nervous system and cardiovascular agents), and changes in organ function including renal, hepatic, and respiratory systems (13). Kidney function changes are particularly significant, as both kidney mass and renal blood flow decline with aging. By age 80, there is approximately a 40% reduction in functional nephrons. Failure to adjust medication doses based on renal function can result in drug accumulation, toxicity, and worsening kidney function (14). Age-related changes in body composition, including alterations in muscle mass and fat distribution, lead to increased inter-individual variability in drug distribution and consequently increased ADE risk. Water-soluble drugs often achieve higher serum concentrations due to relative decreases in total body water in geriatric patients. Conversely, the higher proportion of body fat in older adults can prolong the half-life of fat-soluble drugs such as benzodiazepines (14).

Functional changes and frailty impact

Functional changes related to aging, collectively termed frailty, represent another significant risk factor for ADEs. Frailty is characterized by diminished strength, endurance, and reduced physiologic function that increases vulnerability to dependency and adverse health outcomes. Frailty inherently increases with advancing age and is particularly prevalent among hospitalized and nursing home residents (14). Research has shown that the simultaneous presence of falls risk and dependency in activities of daily living—surrogate markers for frailty—is associated with increased ADE risk in hospitalized geriatric patients. Interestingly, reductions in drug metabolism have been observed in frail geriatric patients compared to more robust older adults, suggesting that frailty impacts not only physical vulnerability but also pharmacological processing (7).

Implementation failures and suboptimal outcomes

Despite the theoretical promise of SCDS, numerous implementation failures and suboptimal outcomes have been documented in the literature, providing important lessons for future deployments. A comprehensive analysis of these challenges reveals several recurring themes that healthcare organizations must proactively address.

Alert fatigue and override behavior

Alert fatigue represents the most extensively documented SCDS implementation challenge. A landmark study by Phansalkar et al. found that drug-drug interaction alerts had override rates ranging from 49% to 96% across different healthcare systems, with median override rates of 87% for drug-drug interaction alerts specifically (72). These high override rates effectively negate the safety benefits of alerting systems, as clinicians become desensitized to warnings and may miss clinically significant alerts embedded among numerous low-priority notifications. Research by Ancker et al. demonstrated that the number of alerts per patient encounter inversely correlated with provider attention to individual alerts, creating a dangerous cycle where increased alerting paradoxically decreases safety (73). Several failed implementations have been attributed to poorly designed alert systems that generated excessive false-positive alerts with insufficient clinical specificity. One large academic medical center reported that after implementing a comprehensive alerting system, providers received an average of 48 alerts per patient admission, with 92% classified as clinically insignificant upon retrospective review; this implementation was subsequently rolled back and redesigned with more selective alert criteria, resulting in 75% reduction in alert volume and improved provider acceptance (74).

Workflow disruption and workarounds

SCDS systems that fail to integrate seamlessly with clinical workflows often prompt providers to develop workarounds that compromise patient safety. Case studies have documented providers entering dummy data to bypass mandatory fields, ignoring alerts without reading them, or using shared login credentials to avoid authentication delays. A qualitative study by Koppel et al. identified 22 distinct types of workarounds used by providers to circumvent CPOE safety features, including entering orders under incorrect patient names and using copy-forward functions that propagated outdated medication lists (75). One particularly concerning failure mode involves forcing functions that are too restrictive, preventing appropriate clinical care in time-sensitive situations. Several emergency departments reported cases where mandatory pharmacist authorization requirements for specific medications caused dangerous delays in treatment, leading to adverse outcomes (76). These implementations were subsequently modified to allow emergency override provisions while maintaining pharmacist review for non-urgent situations.

Interoperability and data quality issues

Fragmented health information exchange represents a fundamental barrier to SCDS effectiveness. Patients receiving care across multiple healthcare systems using different EHR platforms often have incomplete medication histories, rendering drug interaction and duplicate therapy alerts unreliable. A study by Schiff et al. found that 22% of ambulatory patients had discrepancies between their EHR medication lists and actual medications taken, with 10% of discrepancies classified as potentially harmful (77). These data quality issues undermine clinician trust in SCDS recommendations and contribute to alert override behaviors. Several healthcare systems have documented failed attempts to implement comprehensive medication reconciliation processes due to time constraints, inadequate staffing, and technical limitations (78). One large integrated delivery network abandoned a mandated medication reconciliation program after finding that the time required per patient encounter increased by an average of 12 min, creating unacceptable bottlenecks in clinical workflows without demonstrable improvement in medication accuracy (79).

Resistance to change and training inadequacy

Provider resistance represents a significant barrier to SCDS adoption, particularly among clinicians who perceive decision support as questioning their clinical judgment or imposing unnecessary restrictions on prescribing autonomy (80). Several implementations have failed due to inadequate stakeholder engagement during planning phases, resulting in systems that did not meet clinical needs or align with established practice patterns. Training inadequacy has been implicated in multiple suboptimal implementations. One community hospital network reported that only 35% of providers felt competent using SCDS features six months after implementation despite completing required training, suggesting that initial training was insufficient for developing practical competency (81). Subsequent analysis revealed that training focused on technical navigation rather than clinical application and decision-making support, limiting provider ability to effectively utilize system capabilities.

Unintended consequences

Several studies have documented unintended negative consequences of CDSS implementation, including increased medication errors due to confusing interfaces, alert misinterpretation, and assumption that the computer would catch all errors (82). One systematic review by Ash et al. identified nine categories of unintended adverse consequences, including workflow disruption, system demands that alter clinical processes, and new types of errors related to technology use (83). A particularly concerning unintended consequence involves automation bias, where providers over-rely on CDSS recommendations without applying independent clinical judgment. Case reports have documented inappropriate medication continuation when CDSS failed to generate expected alerts due to system failures or data entry errors, with providers assuming that absence of alerts indicated appropriateness of therapy.

Evidence-based interventions

Intervention framework

Implementing effective interventions to reduce ADEs and improve patient safety requires a multifaceted approach that addresses the various risk factors and systemic challenges identified in healthcare delivery. We have developed a framework (Figure 2) based on the WHO Conceptual Framework for the International Classification for Patient Safety (19) to propose evidence-based recommendations for interventions utilizing SCDS. This framework illustrates how SCDS interventions can address multiple contributing factors simultaneously, including healthcare provider factors, system factors, and patient factors. Arrows indicate pathways through which interventions influence outcomes, with feedback loops demonstrating the iterative nature of continuous quality improvement in patient safety.

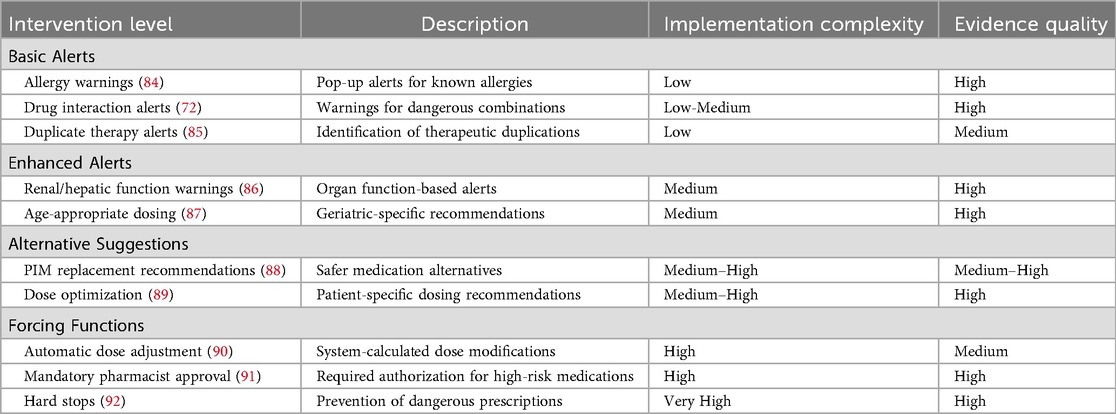

Table 6 illustrates SCDS intervention spectrum and effectiveness.

Spectrum of SCDS interventions

SCDS interventions exist along a continuum from basic alert systems to sophisticated forcing functions. At the foundational level, alert systems warn healthcare providers about patient allergies and medication interactions when prescribing new medications. These alerts serve as immediate clinical reminders, ensuring that providers consider potential adverse reactions before finalizing prescriptions (93). Basic allergy alerts notify providers when they attempt to prescribe medications to patients with documented allergies to those specific agents or drug classes. Drug interaction alerts warn about potentially dangerous combinations when providers prescribe medications that may interact with patients' current medications. These alerts can be expanded to remind providers about patients' abnormal kidney or liver function, which can significantly impact medication metabolism and safety (94).

Evidence-based interventions

However, the effectiveness of basic alert systems remains controversial in the literature. While some studies report significant reductions in prescribing errors with basic alerts, others document high override rates (49%–96% for drug interaction alerts) that substantially diminish their impact (85, 95). This discrepancy likely reflects differences in alert specificity, clinical relevance, and integration with clinical workflows. Studies with lower override rates typically employed more selective alerting strategies, limiting alerts to high-severity interactions and incorporating clinical context into alert triggering logic (85, 96).

Advanced SCDS capabilities

More sophisticated SCDS implementations suggest appropriate alternative medications or dosing adjustments when potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) or doses are entered by providers (37). For example, if a provider enters a prescription for a medication contraindicated due to patient renal insufficiency, the system could recommend an alternative drug or suggest a safer dose based on calculated creatinine clearance. Advanced SCDS systems can incorporate forcing functions that automatically adjust medication doses based on renal or hepatic function. In patients with impaired kidney function, the system could automatically calculate and recommend dose adjustments for renally-cleared medications, ensuring safer medication use without requiring manual calculations by providers (95).

Pharmacist integration and oversight

The most robust SCDS implementations may require providers to obtain pharmacist authorization before prescribing PIMs. This intervention involves pharmacist review of the prescription with either approval or alternative suggestions, adding a crucial layer of safety oversight. Pharmacists can identify less risky medications that still meet patients' therapeutic needs while minimizing ADE risk.

Evidence for intervention effectiveness

The effectiveness of these interventions in mitigating polypharmacy, comorbidity, and physiologic change-related risks depends on their implementation strength and workflow integration. Basic alerts may address some risks but may be insufficient for complex clinical scenarios. Stronger interventions, particularly those involving forcing functions, can significantly reduce ADE risk by ensuring more consistent adherence to clinical guidelines (85). Research by Raebel et al. demonstrated significant decreases in inappropriate medication orders when provider-pharmacist communication regarding inappropriate medication prescribing was required, underscoring the value of integrated, multidisciplinary approaches that combine technological tools with human expertise (97).

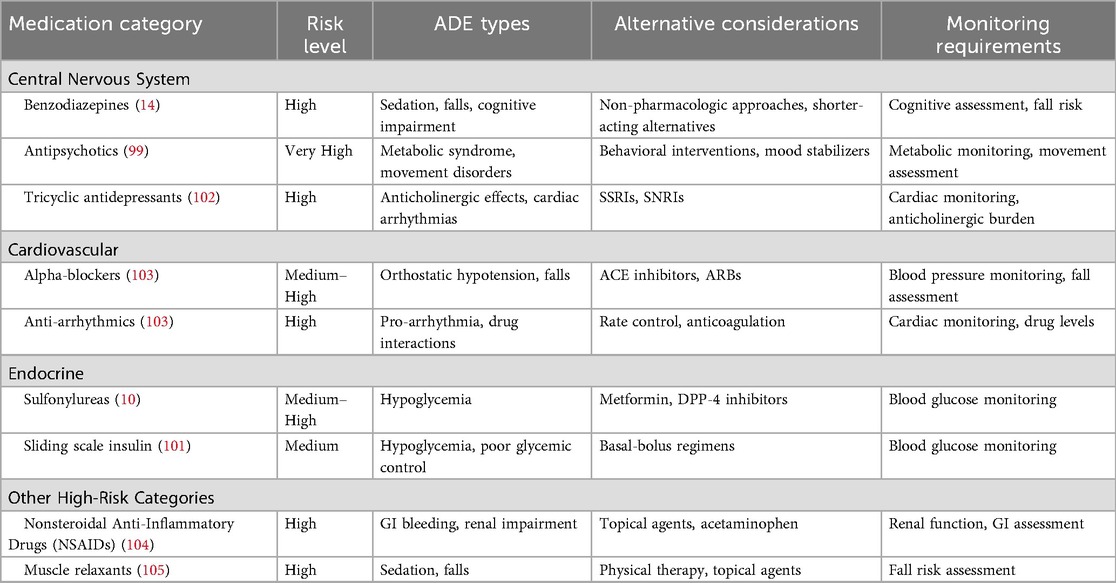

The beers criteria and educational interventions

The American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria is a widely recognized tool that specifies potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) for use in geriatric patients, aiming to reduce adverse clinical outcomes, hospitalizations, mortality, and health care costs associated with these medications (98). The Beers Criteria lists medications that are particularly risky for older adults due to their association with ADEs (99). This list helps mitigate risks related to the physiological and functional changes that occur with aging by identifying medications that are specifically linked to adverse events in geriatric patients. These changes include reduced organ function, altered pharmacokinetics, and increased vulnerability to drug side effects. However, the Beers Criteria also highlights a common knowledge gap among health care providers who are not geriatric specialists, as many medications deemed inappropriate for older adults may be safe for younger populations. While the Beers Criteria provides valuable guidance, it is primarily an educational tool and, as such, is inherently less effective than other interventions that actively enforce safer prescribing practices. Moreover, the Beers Criteria addresses only a fraction of the overall risk, as Beers Criteria medications are implicated in only 16.5% of geriatric ADEs (100). Despite its limitations, the Beers Criteria represents an important first step in addressing ADEs in geriatric patients by targeting providers' knowledge gaps. Table 7 demonstrates the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria for High-Risk Medication Categories (101).

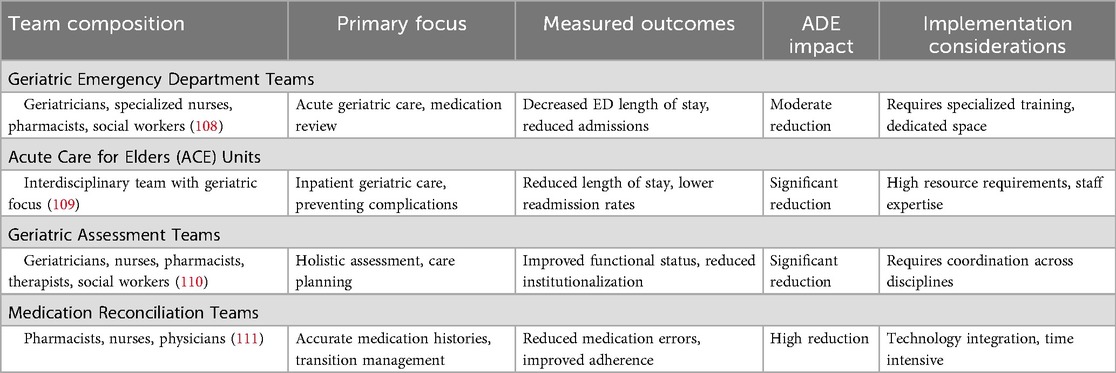

Specialist teams and multidisciplinary approaches

Specialist teams, historically used to manage patients with specific conditions such as HIV or Clostridioides difficile infections, offer promising approaches to ADE prevention (106). These multidisciplinary teams typically include specialized nurses, clinical pharmacists, social workers, specialist consultants, transitional care coordinators, and rehabilitation therapists (98). By addressing patients' functional status and coordinating comprehensive care, these teams can significantly reduce frailty and functional changes that heighten ADE risk (107). Specialist teams focus on medication review and management, identifying and mitigating risks associated with polypharmacy, comorbidities, and age-related physiologic changes. Table 8 illustrates the specialist team interventions and outcomes.

Research demonstrates that models incorporating specialist teams result in improved outcomes, including decreased hospital admission rates, reduced dependency levels, and lower mortality rates (112). Specialist units within hospitals and emergency departments provide targeted care with goals of reducing hospital length of stay and preventing unnecessary admissions. These units foster provider expertise and have demonstrated success in decreasing both length of stay and readmission rates (113, 114).

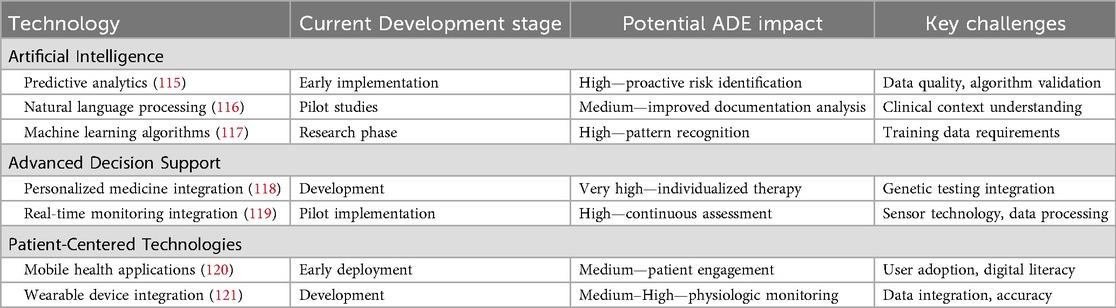

Future directions and innovation opportunities

Artificial intelligence integration

The future of SCDS lies in the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to enhance predictive capabilities and personalize interventions. AI-powered systems can analyze vast amounts of patient data to identify subtle patterns that may indicate increased ADE risk, enabling proactive interventions before adverse events occur. Table 9 shows the emerging technologies in SCDS.

Genomic medicine and pharmacogenomics

The integration of pharmacogenomic testing into SCDS represents a significant opportunity for personalizing medication therapy and reducing ADEs (122). Understanding individual genetic variations that affect drug metabolism can guide medication selection and dosing decisions, particularly for medications with narrow therapeutic windows or known genetic variations in metabolism.

Real-time physiological monitoring

Advanced monitoring technologies, including wearable devices and continuous physiological sensors, can provide real-time data about patient responses to medications. This information can be integrated into SCDS to provide immediate alerts about potential adverse reactions and enable rapid intervention (123).

Patient-generated health data integration

The incorporation of patient-generated health data from mobile applications, wearable devices, and patient-reported outcome measures can enhance SCDS by providing comprehensive pictures of patient responses to medications outside clinical settings (124). This information can identify ADEs that might otherwise go undetected in traditional healthcare encounters.

Healthcare economic impact of ADEs

The economic burden of ADEs extends far beyond immediate treatment costs, encompassing direct medical expenses, indirect costs associated with lost productivity, and long-term healthcare utilization increases. Understanding these economic implications is crucial for justifying investments in SCDS implementation. Economic analyses consistently demonstrate that investments in SCDS technology and implementation generate significant returns through ADE reduction (125).

Value-based care integration

SCDS aligns well with value-based care models that emphasize patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness rather than volume of services. Healthcare organizations participating in value-based contracts can leverage SCDS to improve quality metrics while reducing overall costs of care (126).

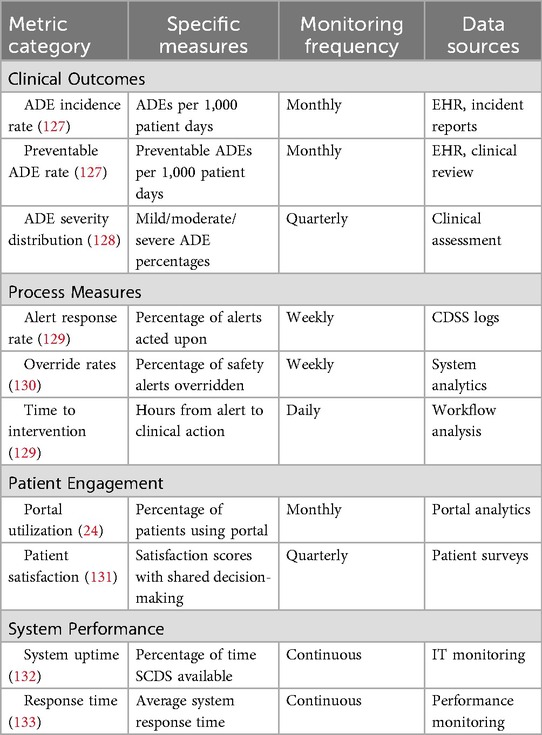

Quality metrics and performance measurement

Measuring the effectiveness of SCDS implementation requires monitoring of multiple performance indicators that reflect both process improvements and clinical outcomes. Table 10 presents the SCDS performance metrics.

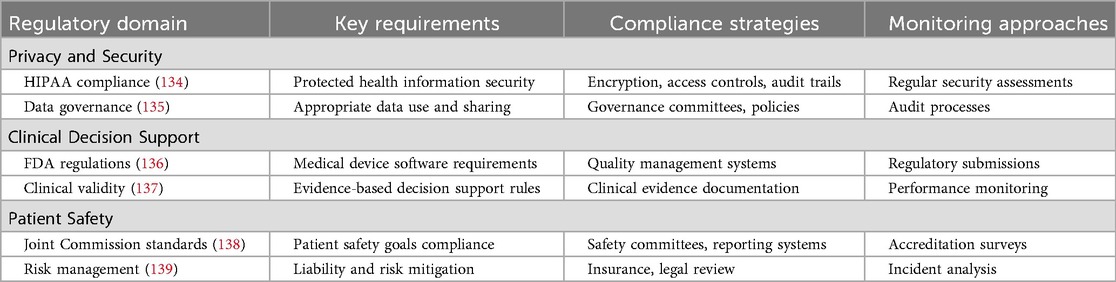

Regulatory and legal considerations

SCDS implementation must comply with various regulatory requirements, including HIPAA privacy and security regulations, FDA guidelines for medical device software, and Joint Commission patient safety standards. Table 11 demonstrates the regulatory compliance framework for SCDS.

Healthcare organizations implementing SCDS must carefully consider liability implications and develop risk management strategies. This includes ensuring appropriate clinical validation of decision support rules, maintaining adequate professional liability coverage, and establishing clear protocols for system failures or unexpected outcomes (140).

Discussion

Overview

The review of shared clinical decision support demonstrates significant potential for reducing adverse drug events and improving patient safety outcomes. SCDS represents a paradigm shift toward patient-centered care that leverages technology to enhance clinical decision-making while empowering patients to actively participate in their healthcare decisions. The evidence clearly supports a multifaceted approach to ADE prevention that combines educational initiatives, human factors engineering, robust shared clinical decision support systems, and multidisciplinary collaborative care models. The most effective implementations integrate strong technological capabilities with human expertise and continuous quality improvement methodologies.

Critical analysis of implementation challenges

While our review demonstrates the potential of SCDS to reduce ADEs, successful implementation faces substantial obstacles that warrant careful consideration. The gap between theoretical promise and practical implementation remains considerable across healthcare settings. Alert fatigue represents one of the most significant barriers to SCDS effectiveness, with studies indicating that clinicians override 49%–96% of drug interaction alerts, potentially missing critical safety warnings (141). This desensitization occurs when clinicians are overwhelmed by excessive, non-specific, or clinically irrelevant alerts, leading to dangerous override behaviors that undermine system effectiveness.

Interoperability challenges further complicate SCDS implementation, particularly in healthcare systems utilizing multiple electronic health record platforms or serving patients who receive care across different healthcare organizations. Incomplete medication histories due to fragmented health information exchange can result in missed drug interactions or duplicate therapy alerts, paradoxically increasing ADE risk despite SCDS deployment. The lack of standardization in clinical decision support rules across different systems creates inconsistencies in care delivery and may confuse providers practicing in multiple settings.

Comparative effectiveness of interventions

Our analysis reveals a spectrum of intervention effectiveness, with forcing functions and mandatory pharmacist review demonstrating superior outcomes compared to basic alert systems. However, these more robust interventions require greater implementation complexity, resource investment, and workflow integration. Healthcare organizations must balance intervention strength against feasibility and user acceptance, as overly restrictive systems may prompt workaround behaviors that compromise patient safety. Translating these models to community hospitals and rural healthcare settings presents significant challenges related to staffing, expertise availability, and financial sustainability (142). Further research is needed to develop scalable implementation models that maintain effectiveness while accommodating resource constraints in diverse healthcare settings.

Limitations

This narrative review has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, our search strategy was not exhaustive, and we may have missed relevant studies, particularly those published in non-English languages or in specialty journals outside our search parameters. Second, the included studies may limit generalizability to healthcare systems with different organizational structures, regulatory environments, and cultural approaches to clinical decision-making. Third, the heterogeneity of SCDS interventions described in the literature made direct comparisons challenging, and we were unable to conduct meta-analyses of intervention effectiveness.

Recommendations for future research

Future research should prioritize comparative effectiveness studies that rigorously evaluate different SCDS intervention strategies across diverse healthcare settings, patient populations, and geographic regions. Head-to-head comparisons of basic alerts vs. forcing functions, different pharmacist integration models, and various specialist team configurations would inform evidence-based implementation decisions and help healthcare organizations select optimal strategies for their specific contexts.

Implementation science research employing established frameworks should examine barriers and facilitators to SCDS adoption, strategies for overcoming alert fatigue, and methods for sustaining system effectiveness over time (143). Mixed-methods approaches combining quantitative outcomes with qualitative exploration of provider and patient experiences would provide valuable insights into the human factors influencing implementation success and identify modifiable factors that can be addressed through targeted interventions (144).

Comprehensive cost-effectiveness analyses comparing different SCDS implementation strategies would support resource allocation decisions and business case development (145). These economic evaluations should include long-term return on investment calculations, assessment of indirect benefits such as improved patient satisfaction and reduced liability exposure, and consideration of implementation and maintenance costs across diverse healthcare settings with varying resource availability (146).

As AI technologies mature, rigorous evaluation of AI-enhanced SCDS systems through randomized controlled trials and pragmatic clinical studies should assess both effectiveness and potential unintended consequences (147). Research should examine AI systems' ability to predict ADE risk, personalize interventions based on individual patient characteristics, and improve upon traditional rule-based decision support while carefully monitoring for algorithmic bias, inappropriate automation reliance, and other novel safety concerns (148).

Finally, longitudinal research examining sustained effects of SCDS implementation on clinical outcomes, healthcare costs, and patient satisfaction over extended time periods would demonstrate durability of benefits and identify factors associated with sustained effectiveness. These studies should investigate whether initial improvements are maintained over time, how systems adapt to changing clinical guidelines and technologies, and what organizational characteristics predict long-term implementation success.

Conclusion

The transformation of healthcare delivery through SCDS implementation represents both a significant opportunity and a substantial challenge. Success requires sustained commitment from healthcare organizations, continued investment in technology infrastructure, and ongoing dedication to patient safety improvement. The potential benefits—reduced patient harm, improved healthcare quality, decreased costs, and enhanced patient satisfaction—justify the substantial effort required for successful implementation. As healthcare continues to evolve toward value-based care models, SCDS will play an increasingly important role in achieving the triple aim of better patient experience, improved population health, and reduced per capita healthcare costs. The integration of emerging technologies, including AI, genomic medicine, and real-time physiological monitoring, will continue to enhance SCDS capabilities and expand its impact on patient safety. Healthcare organizations that invest in SCDS implementation today will be well-positioned to realize these future benefits and lead the transformation toward safer, more effective healthcare delivery. The ultimate goal of SCDS implementation extends beyond simply reducing adverse drug events to creating a healthcare system that consistently delivers the right care, to the right patient, at the right time, in the right setting, with optimal outcomes and minimal risk. This vision requires continued innovation, sustained commitment, and collaborative effort from all healthcare stakeholders, but the potential benefits for patients, providers, and healthcare systems justify this substantial undertaking.

Author contributions

JY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Ryan RE, Santesso N, Lowe D, Hill S, Grimshaw JM, Prictor M, et al. Interventions to improve safe and effective medicines use by consumers: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2014) 2014(4):CD007768. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007768.pub3

2. Bailey C, Peddie D, Wickham ME, Badke K, Small SS, Doyle-Waters MM, et al. Adverse drug event reporting systems: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. (2016) 82(1):17–29. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12944

3. US Department of Health and Human Services. National action plan for adverse drug event prevention (2014). Available online at: https://odphp.health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/ADE-Action-Plan-508c.pdf (Accessed September 30, 2014).

4. Budnitz DS, Shehab N, Kegler SR, Richards CL. Medication use leading to emergency department visits for adverse drug events in older adults. Ann Intern Med. (2007) 147(11):755–65. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-11-200712040-00006

5. Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, Green C, Scott AK, Walley TJ, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. Br Med J. (2004) 329(7456):15–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7456.15

6. Kanagaratnam L, Dramé M, Trenque T, Oubaya N, Nazeyrollas P, Novella J-L, et al. Adverse drug reactions in elderly patients with cognitive disorders: a systematic review. Maturitas. (2016) 85:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.12.013

7. Lattanzio F, Landi F, Bustacchini S, Abbatecola AM, Corica F, Pranno L, et al. Geriatric conditions and the risk of adverse drug reactions in older adults. Drug Saf. (2012) 35(1):55–61. doi: 10.1007/BF03319103

8. Cahir C, Bennett K, Teljeur C, Fahey T. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and adverse health outcomes in community dwelling older patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. (2014) 77(1):201–10. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12161

9. Institute for Healthcare. IHI trigger tool for measuring adverse drug events (2009). Available online at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Measures/HighAlertAdverseDrugEventsper1000Doses.aspx (Accessed January 01, 2009).

10. Bobb A, Gleason K, Husch M, Feinglass J, Yarnold PR, Noskin GA. The epidemiology of prescribing errors: the potential impact of computerized prescriber order entry. Arch Intern Med. (2004) 164(7):785–92. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.7.785

12. Rawlins MD, Thompson JW. Pathogenesis of adverse drug reactions. In: Davies DM, editor. Text Book of Adverse Drug Reactions. London: Oxford University Press (1977). p. 10.

13. Brahma DK, Wahlang JB, Marak MD, Sangma MC. Adverse drug reactions in the elderly. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. (2013) 4(2):91–4. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.110872

14. Davies E, O'mahony M. Adverse drug reactions in special populations–the elderly. Br J Clin Pharmacol. (2015) 80(4):796–807. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12596

15. Barton L, Futtermenger J, Gaddi Y, Kang A, Rivers J, Spriggs D, et al. Simple prescribing errors and allergy documentation in medical hospital admissions in Australia and New Zealand. Clin Med. (2012) 12(2):119–23. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.12-2-119

16. Lewis PJ, Dornan T, Taylor D, Tully MP, Wass V, Ashcroft DM. Prevalence, incidence and nature of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a systematic review. Drug Saf. (2009) 32(5):379–89. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200932050-00002

17. Ye J. Patient safety of perioperative medication through the lens of digital health and artificial intelligence. JMIR Periop Med. (2023) 6:e34453. doi: 10.2196/34453

18. Feinglass J, Wang JA, Ye J, Tessier R, Kim H. Hospital care for opioid use in Illinois, 2016–2019. J Behav Health Serv Res. (2021) 48(4):597–609. doi: 10.1007/s11414-020-09748-8

19. World Health Organization. The conceptual framework for the international classification for patient safety. Version 1.1. Final Technical Report (2009). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-PSP-2010.2 (Accessed January 15, 2009).

20. Shahmoradi L, Safdari R, Ahmadi H, Zahmatkeshan M. Clinical decision support systems-based interventions to improve medication outcomes: a systematic literature review on features and effects. Med J Islam Repub Iran. (2021) 35:27. doi: 10.47176/mjiri.35.27

21. Légat L, Van Laere S, Nyssen M, Steurbaut S, Dupont AG, Cornu P. Clinical decision support systems for drug allergy checking: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. (2018) 20(9):e258. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8206

22. Kaushal R, Bates DW. Computerized physician order entry (CPOE) with clinical decision support systems (CDSSs). In: Making Health Care Safer: a Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. (2001). p. 58. Available online at: http://www.aesculapseguridaddelpaciente.org.mx/docs/cultura-de-seguridad-del-paciente/An%C3%A1lisis_pr%C3%A1cticas_seguridad_%20pacientes_Julio%202001.pdf#page=68 (Accessed July 01, 2001).

23. Horsky J, Schiff GD, Johnston D, Mercincavage L, Bell D, Middleton B. Interface design principles for usable decision support: a targeted review of best practices for clinical prescribing interventions. J Biomed Inform. (2012) 45(6):1202–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2012.09.002

24. Irizarry T, DeVito Dabbs A, Curran CR. Patient portals and patient engagement: a state of the science review. J Med Internet Res. (2015) 17(6):e148. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4255

25. Hassol A, Walker JM, Kidder D, Rokita K, Young D, Pierdon S, et al. Patient experiences and attitudes about access to a patient electronic health care record and linked web messaging. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2004) 11:505–13. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1593

26. Ye J, Yao L, Shen J, Janarthanam R, Luo Y. Predicting mortality in critically ill patients with diabetes using machine learning and clinical notes. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2020) 20(11):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12911-020-01318-4

27. Ye J, Sanuade OA, Hirschhorn LR, Walunas TL, Smith JD, Birkett MA, et al. Interventions and contextual factors to improve retention in care for patients with hypertension in primary care: hermeneutic systematic review. Prev Med. (2024) 180:107880. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2024.107880

28. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. (2007) 297(8):831–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.831

29. Jungreithmayr V, Meid AD, Bittmann J, Fabian M, Klein U, Kugler S, et al. The impact of a computerized physician order entry system implementation on 20 different criteria of medication documentation—a before-and-after study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2021) 21(1):279. doi: 10.1186/s12911-021-01607-6

30. Ranji SR, Rennke S, Wachter RM. Computerised provider order entry combined with clinical decision support systems to improve medication safety: a narrative review. BMJ Qual Saf. (2014) 23(9):773–80. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002165

31. Ye J, Woods D, Jordan N, Starren J. The role of artificial intelligence for the application of integrating electronic health records and patient-generated data in clinical decision support. AMIA Summits Transl Sci Proc. (2024) 2024:459–67. PMID: 38827061.38827061

32. Ye J. Transforming and facilitating health care delivery through social networking platforms: evidences and implications from WeChat. JAMIA Open. (2024) 7(2):ooae047. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooae047

33. Kruse CS, Argueta DA, Lopez L, Nair A. Patient and provider attitudes toward the use of patient portals for the management of chronic disease: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. (2015) 17(2):e40. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3703

34. Lainer M, Mann E, Soennichsen A. Information technology interventions to improve medication safety in primary care: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. (2013) 25(5):590–8. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzt043

35. Greenwald JL, Halasyamani L, Greene J, LaCivita C, Stucky E, Benjamin B, et al. Making inpatient medication reconciliation patient centered, clinically relevant and implementable: a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps. J Hosp Med. (2010) 5(8):477–85. doi: 10.1002/jhm.849

36. Downing GJ, Boyle SN, Brinner KM, Osheroff JA. Information management to enable personalized medicine: stakeholder roles in building clinical decision support. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2009) 9:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-9-44

37. Ye J, Hai J, Song J, Wang Z, The role of artificial intelligence in the application of the integrated electronic health records and patient-generated health data. medRxiv, p. 2024.05. 01.24306690 (2024).

38. Ash JS, Sittig DF, Guappone KP, Dykstra RH, Richardson J, Wright A, et al. Recommended practices for computerized clinical decision support and knowledge management in community settings: a qualitative study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2012) 12:1–19. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-6

39. Volk RJ, Shokar NK, Leal VB, Bulik RJ, Linder SK, Mullen PD, et al. Development and pilot testing of an online case-based approach to shared decision making skills training for clinicians. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2014) 14(1):95. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-14-95

40. Osheroff J, Teich J, Levick D, Saldana L, Velasco F, Sittig D, et al. Improving Outcomes with Clinical Decision Support: An Implementer’s Guide. New York: Himss Publishing (2012).

41. Karsh B-T. Clinical Practice Improvement and Redesign: How Change in Workflow can be Supported by Clinical Decision Support. Madison: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2009).

42. Ye J. Design and development of an informatics-driven implementation research framework for primary care studies. In AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings, American Medical Informatics Association (2021).

43. Ye J, Orji IA, Birkett MA, Hirschhorn LR, Walunas TL, Smith JD, et al. Community-Based participatory research and system dynamics modeling for improving retention in hypertension care. JAMA Network Open. (2024) 7(8):e2430213. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.30213

44. Sutton RT, Pincock D, Baumgart DC, Sadowski DC, Fedorak RN, Kroeker KI. An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success. npj Digit Med. (2020) 3(1):17. doi: 10.1038/s41746-020-0221-y

45. Musen MA, Middleton B, Greenes RA. Clinical decision-support systems. In: Shortliffe EH, Cimino JJ, editors. Biomedical Informatics: Computer Applications in Health Care and Biomedicine. Cham: Springer (2021). p. 795–840.

46. Lomotan EA, Meadows G, Michaels M, Michel JJ, Miller K. To share is human! advancing evidence into practice through a national repository of interoperable clinical decision support. Appl Clin Inform. (2020) 11(01):112–21. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1701253

47. Horsky J, McColgan K, Pang JE, Melnikas AJ, Linder JA, Schnipper JL, et al. Complementary methods of system usability evaluation: surveys and observations during software design and development cycles. J Biomed Inform. (2010) 43(5):782–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2010.05.010

48. Al Damen L, Basheti I. Preventability analysis of adverse drug reactions in a Jordanian hospital: a prospective observational study. Int J Clin Pharm. (2019) 41(6):1599–610. doi: 10.1007/s11096-019-00925-0

49. Tangiisuran B, Wright J, Van der Cammen T, Rajkumar C. Adverse drug reactions in elderly: challenges in identification and improving preventative strategies. Age Ageing. (2009) 38(4):358–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp050

50. Kanji S, Lam J, Johanson C, Singh A, Goddard R, Fairbairn J, et al. Systematic review of physical and chemical compatibility of commonly used medications administered by continuous infusion in intensive care units. Crit Care Med. (2010) 38(9):1890–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e8adcc

51. Adachi W, Lodolce AE. Use of failure mode and effects analysis in improving the safety of iv drug administration. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. (2005) 62(9):917–20. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/62.9.917

52. Blijleven V, Koelemeijer K, Wetzels M, Jaspers M. Workarounds emerging from electronic health record system usage: consequences for patient safety, effectiveness of care, and efficiency of care. JMIR Hum Factors. (2017) 4(4):e7978. doi: 10.2196/humanfactors.7978

53. Mahmood A, Chaudhury H, Valente M. Nurses’ perceptions of how physical environment affects medication errors in acute care settings. Appl Nurs Res. (2011) 24(4):229–37. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2009.08.005

54. Gurwitz JH, Kapoor A, Garber L, Mazor KM, Wagner J, Cutrona SL, et al. Effect of a multifaceted clinical pharmacist intervention on medication safety after hospitalization in persons prescribed high-risk medications: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. (2021) 181(5):610–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.9285

55. Zazzara MB, Palmer K, Vetrano DL, Carfì A, Onder G. Adverse drug reactions in older adults: a narrative review of the literature. Eur Geriatr Med. (2021) 12(3):463–73. doi: 10.1007/s41999-021-00481-9

56. Zaij S, Pereira Maia K, Leguelinel-Blache G, Roux-Marson C, Kinowski JM, Richard H. Intervention of pharmacist included in multidisciplinary team to reduce adverse drug event: a qualitative systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. (2023) 23(1):927. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09512-6

57. Field TS, Mazor KM, Briesacher B, DeBellis KR, Gurwitz JH. Adverse drug events resulting from patient errors in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2007) 55(2):271–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01047.x

58. Ye J, Woods D, Bannon J, Bilaver L, Kricke G, McHugh M, et al. Identifying contextual factors and strategies for practice facilitation in primary care quality improvement using an informatics-driven model: framework development and mixed methods case study. JMIR Hum Factors. (2022) 9(2):e32174. doi: 10.2196/32174

59. Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. (2012) 380(9836):37–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2

60. Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, Naganathan V, Waite L, Seibel MJ, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. (2012) 65(9):989–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.02.018

61. Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. (2014) 13(1):57–65. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2013.827660

62. Mangoni AA, Jackson SH. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. (2004) 57(1):6–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.02007.x

63. Klotz U. Pharmacokinetics and drug metabolism in the elderly. Drug Metab Rev. (2009) 41(2):67–76. doi: 10.1080/03602530902722679

64. Cusack BJ. Pharmacokinetics in older persons. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. (2004) 2(4):274–302. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2004.12.005

65. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2001) 56(3):M146–57. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146

66. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. (2013) 381(9868):752–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9

67. Saum KU, Schöttker B, Meid AD, Holleczek B, Haefeli WE, Hauer K, et al. Is polypharmacy associated with frailty in older people? Results from the ESTHER cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2017) 65(2):e27–32. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14718

68. Chen H, Ye J. Digital health technology burden and frustration among patients with multimorbidity. medRxiv. 2025.10. 09.25337645. (2025). doi: 10.1101/202510.09.25337645

69. Abebe F, Schneider M, Asrat B, Ambaw F. Multimorbidity of chronic non-communicable diseases in low-and middle-income countries: a scoping review. J Comorb. (2020) 10:2235042X-20961919. doi: 10.1177/2235042X20961919

70. Jose J, Rao PG. Pattern of adverse drug reactions notified by spontaneous reporting in an Indian tertiary care teaching hospital. Pharmacol Res. (2006) 54(3):226–33. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2006.05.003

71. Kojima T, Akishita M, Kameyama Y, Yamaguchi K, Yamamoto H, Eto M, et al. High risk of adverse drug reactions in elderly patients taking six or more drugs: analysis of inpatient database. Geriatr Gerontol Int. (2012) 12(4):761–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00868.x

72. Phansalkar S, Desai AA, Bell D, Yoshida E, Doole J, Czochanski M, et al. High-priority drug–drug interactions for use in electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2012) 19(5):735–43. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000612

73. Ancker JS, Edwards A, Nosal S, Hauser D, Mauer E, Kaushal R. Effects of workload, work complexity, and repeated alerts on alert fatigue in a clinical decision support system. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2017) 17(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12911-017-0430-8

74. Syrowatka A, Motala A, Lawson E, Shekelle P. Computerized clinical decision support to prevent medication errors and adverse drug events: rapid review. In: Making Healthcare Safer IV: A Continuous Updating of Patient Safety Harms and Practices. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US) (2024). Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK600580/ (Accessed February 25, 2024).

75. Koppel R, Metlay JP, Cohen A, Abaluck B, Localio AR, Kimmel SE, et al. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. JAMA. (2005) 293(10):1197–203. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1197

76. Cohen V, Jellinek SP, Hatch A, Motov S. Effect of clinical pharmacists on care in the emergency department: a systematic review. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. (2009) 66(15):1353–61. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080304

77. Schiff G, Mirica MM, Dhavle AA, Galanter WL, Lambert B, Wright A. A prescription for enhancing electronic prescribing safety. Health Aff. (2018) 37(11):1877–83. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0725

78. Ye J. Health information system’s responses to COVID-19 pandemic in China: a national cross-sectional study. Appl Clin Inform. (2021) 12(02):399–406. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1728770

79. Briggs J, Kostakis I, Meredith P, Dall’ora C, Darbyshire J, Gerry S, et al. Safer and more efficient vital signs monitoring protocols to identify the deteriorating patients in the general hospital ward: an observational study. Health Soc Care Deliv Res. (2024) 12(6):1–143. doi: 10.3310/HYTR4612

80. Ye J. Advancing mental health and psychological support for health care workers using digital technologies and platforms. JMIR Form Res. (2021) 5(6):e22075. doi: 10.2196/22075

81. Légaré F, Adekpedjou R, Stacey D, Turcotte S, Kryworuchko J, Graham ID, et al. Interventions for increasing the use of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2018) 7(7):CD006732. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub4

82. Stone EG. Unintended adverse consequences of a clinical decision support system: two cases. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2018) 25(5):564–7. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx096

83. Ash JS, Berg M, Coiera E. Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: the nature of patient care information system-related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2004) 11(2):104–12. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1471

84. Riedmann D, Jung M, Hackl WO, Stühlinger W, van der Sijs H, Ammenwerth E. Development of a context model to prioritize drug safety alerts in CPOE systems. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2011) 11(1):35. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-11-35

85. Nanji KC, Slight SP, Seger DL, Cho I, Fiskio JM, Redden LM, et al. Overrides of medication-related clinical decision support alerts in outpatients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2014) 21(3):487–91. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001813

86. Chertow GM, Lee J, Kuperman GJ, Burdick E, Horsky J, Seger DL, et al. Guided medication dosing for inpatients with renal insufficiency. JAMA. (2001) 286(22):2839–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.22.2839

87. Galanter WL, Hier DB, Jao C, Sarne D. Computerized physician order entry of medications and clinical decision support can improve problem list documentation compliance. Int J Med Inf. (2010) 79(5):332–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2008.05.005

88. Terrell KM, Perkins AJ, Dexter PR, Hui SL, Callahan CM, Miller DK. Computerized decision support to reduce potentially inappropriate prescribing to older emergency department patients: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2009) 57(8):1388–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02352.x

89. Peterson JF, Kuperman GJ, Shek C, Patel M, Avorn J, Bates DW. Guided prescription of psychotropic medications for geriatric inpatients. Arch Intern Med. (2005) 165(7):802–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.7.802

90. Kaushal R, Shojania KG, Bates DW. Effects of computerized physician order entry and clinical decision support systems on medication safety: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. (2003) 163(12):1409–16. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.12.1409

91. Baysari MT, Westbrook JI, Richardson KL, Day RO. The influence of computerized decision support on prescribing during ward-rounds: are the decision-makers targeted? J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2011) 18(6):754–9. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000135

92. Tariq RA, Vashisht R, Sinha A, Scherbak Y. Medication dispensing errors and prevention. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing (2024). Available online at: https://europepmc.org/article/NBK/nbk519065 (Accessed February 12, 2024).

93. Motter FR, Fritzen JS, Hilmer SN, Paniz ÉV, Paniz VMV. Potentially inappropriate medication in the elderly: a systematic review of validated explicit criteria. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. (2018) 74:679–700. doi: 10.1007/s00228-018-2446-0

95. Slight SP, Seger DL, Nanji KC, Cho I, Maniam N, Dykes PC, et al. Are we heeding the warning signs? Examining providers’ overrides of computerized drug-drug interaction alerts in primary care. PLoS One. (2013) 8(12):e85071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085071

96. Wong A, Amato MG, Seger DL, Slight SP, Beeler PE, Dykes PC, et al. Evaluation of medication-related clinical decision support alert overrides in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. (2017) 39:156–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.02.027

97. Raebel MA, Charles J, Dugan J, Carroll NM, Korner EJ, Brand DW, et al. Randomized trial to improve prescribing safety in ambulatory elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2007) 55(7):977–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01202.x

98. Lindquist LA, Dresden SM. Geriatric Emergencies: A Case-based Approach to Improving Acute Care. Cham: Springer (2019).

99. 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel, Fick DM, Semla TP, Steinman M, Beizer J, Brandt N, Dombrowski R, et al. American Geriatrics society 2019 updated AGS beers criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2019) 67(4):674–94. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15767

100. Kanaan AO, Donovan JL, Duchin NP, Field TS, Tjia J, Cutrona SL, et al. Adverse drug events after hospital discharge in older adults: types, severity, and involvement of beers criteria medications. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2013) 61(11):1894–9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12504

101. Charles CV. 2023 AGS beers criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older people: a summary of the updates. Sr Care Pharm. (2023) 38(9):352–4. doi: 10.4140/TCP.n.2023.352

102. Markota M., Rummans TA, Bostwick JM, Lapid MI. Benzodiazepine use in older adults: dangers, management, and alternative therapies. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings, Elsevier. pp. 1632–9 (2016).

103. Rudolph JL, Salow MJ, Angelini MC, McGlinchey RE. The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch Intern Med. (2008) 168(5):508–13. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.106

104. Lanas A, Chan FK. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet. (2017) 390(10094):613–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32404-7

105. Wongrakpanich S, Melhado K, Rangaswami J. A comprehensive review of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in the elderly. Aging Dis. (2018) 9(1):143. doi: 10.14336/AD.2017.0306