- 1School of Dentistry, The University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan

- 2School of Medicine, The University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan

Background: Artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots are increasingly consulted for dental aesthetics information. This study evaluated the performance of multiple large language models (LLMs) in answering patient questions about tooth whitening.

Methods: 109 patient-derived questions, categorized into five clinical domains, were submitted to four LLMs: ChatGPT-4o, Google Gemini, DeepSeek R1, and DentalGPT. Two calibrated specialists evaluated responses for usefulness, quality (Global Quality Scale), reliability (CLEAR tool), and readability (Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease, SMOG index).

Results: The models generated consistently high-quality information. Most responses (68%) were “very useful” (mean score: 1.24 ± 0.3). Quality (mean GQS: 3.9 ± 2.0) and reliability (mean CLEAR: 22.5 ± 2.4) were high, with no significant differences between models or domains (p > 0.05). However, readability was a major limitation, with a mean FRE score of 36.3 (“difficult” level) and a SMOG index of 11.0, requiring a high school reading level.

Conclusions: Contemporary LLMs provide useful and reliable information on tooth whitening but deliver it at a reading level incompatible with average patient health literacy. To be effective patient education adjuncts, future AI development must prioritize readability simplification alongside informational accuracy.

Introduction

Tooth whitening has become an increasingly popular cosmetic procedure globally, influenced by social media and celebrity notions of the “Hollywood smile”. Recent data indicate a rising demand among patients for whiter teeth; for instance, over one million Americans undergo whitening treatments annually, generating approximately $600 million in dental revenue (1, 2). Market analyses estimate that the global teeth whitening industry was worth nearly USD 6.9 billion in 2021, with projections toward USD 10.6 billion by 2030 (3).

Consumers now have access to a variety of whitening methods, including in-office bleaching, over-the-counter kits, and home remedies, reflecting a global trend toward improved dental aesthetics. Simultaneously, patients frequently turn to the internet to seek health-related information. In the United States, 58.5% of adults reported using the internet to search for health or medical information within a recent year (4). Notably, Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven chatbots (such as OpenAI's ChatGPT and Google's Gemini) provide patients with round-the-clock interactive guidance on medical topics via smartphones and web browsers (5–7). These advanced large language model (LLM) chatbots are trained on extensive text corpora, allowing them to generate coherent, human-like responses to user queries (8, 9). Consequently, AI chatbots have become a convenient source of dental information, effectively making critical oral health advice readily accessible to patients (7).

AI chatbots have experienced rapid development. OpenAI's ChatGPT (with GPT-3.5 introduced in 2022 and GPT-4 in 2023) and Google's Gemini (launched in 2023) are among the most advanced general-purpose conversational agents available. Furthermore, new models such as DeepSeek-R1 (debuted in January 2025) have emerged, claiming comparable performance to ChatGPT at a reduced cost (10). Domain-specific variants are also forthcoming; for example, OpenAI's “Dental GPT” (released in June 2024) addresses questions specific to dentistry (11). As these models continually refine their reasoning and training capabilities, their practical functionalities are progressively enhanced. In fact, large language models like ChatGPT-4 and Gemini have demonstrated the ability to comprehend context and deliver sophisticated responses within healthcare settings (12, 13). By providing on-demand medical guidance, AI chatbots can assist individuals in managing their health more effectively, particularly when access to human healthcare providers is limited (6, 14).

Despite their promise, questions persist regarding the accuracy and reliability of AI chatbots within healthcare environments. Several studies have reported commendable performance; for instance, Arpaci et al. (2025) observed that ChatGPT-4 and Gemini provided responses to common oral health inquiries that closely aligned with expert (Fédération Dentaire Internationale - FDI) answers, with ChatGPT-4 demonstrating marginally greater accuracy (15). Similarly, a particular study in the dental field reported that a specialized “Dental GPT” model achieved the highest accuracy for prosthodontics-related questions, whereas ChatGPT-4 scored lower, and DeepSeek generated more comprehensible text (11). Conversely, other research findings have been more critical. Molena et al. (2024) noted that ChatGPT-3.5 occasionally delivered inconsistent or incorrect responses to clinical inquiries, including errors in calculations and citations of non-existent literature (16). These mixed results highlight an ongoing debate: AI chatbots can provide comprehensive health advice, yet instances of errors or “hallucinations” can occur, and the information may not always be current or entirely dependable. Systematic reviews further indicate that evidence regarding the clinical efficacy of patient-facing chatbots remains limited (6, 17).

While comparative evaluations of LLMs in dentistry are emerging, they have largely focused on diagnostic, surgical, or prosthodontic topics (18, 19). A notable gap remains concerning the performance of AI chatbots, including both general-purpose and domain-specific models, in addressing patient inquiries within cosmetic dentistry, a high-demand area where patients frequently seek online information. To the best of our knowledge, no study has directly compared the performance of both leading general-purpose models (ChatGPT-4o, Gemini, DeepSeek) and a newly released domain-specific model (DentalGPT) on a comprehensive set of patient inquiries related to tooth whitening. Recognizing this gap is of considerable importance: tooth whitening remains a prevalent consumer trend, yet the safety and accuracy of online advice—particularly that generated by AI—regarding this procedure are uncertain. Consequently, this study seeks to bridge that gap by directly comparing four leading chatbots—OpenAI's ChatGPT-4o, Google's Gemini, DeepSeek R1, and DentalGPT—in their responses to comprehensive frequently asked patient questions about tooth whitening. This study will generate the most common questions related to tooth whitening using reputable search query tools, followed by a systematic assessment of each chatbot's responses in terms of readability, usefulness, accuracy, and reliability. Through this analysis, this study aims to identify the respective strengths and weaknesses of each AI tool within the context of this popular dental concern, thereby evaluating their capacity to adequately meet patient information needs regarding tooth whitening.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval and study protocol

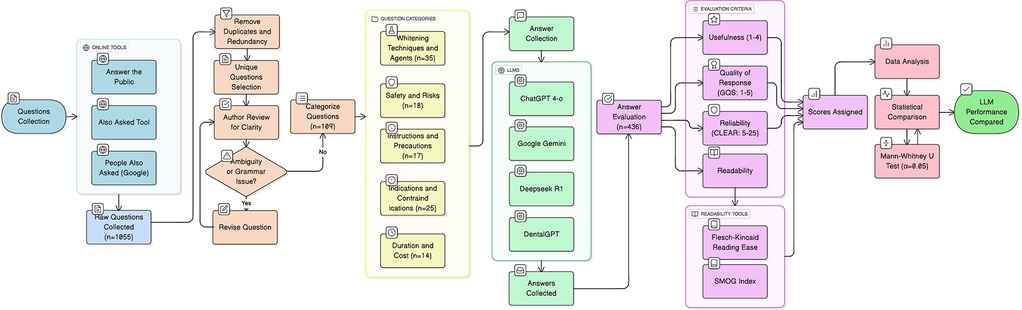

Ethical approval was not required for this study, as it did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any access to private patient data. The research was conducted exclusively through the analysis of publicly accessible artificial intelligence models, using a set of simulated patient questions. The study protocol, detailing the transparent process of question generation, selection, and analysis, is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart illustrating the process of question selection and analysis. An initial pool of 1,055 questions was generated from online tools. After removal of duplicates and irrelevant questions, 109 unique questions were retained, categorized into five domains, and submitted to four LLMs. Their responses were then evaluated for usefulness, quality, reliability, and readability.

Generation of simulated patient questions for LLMs

A total of 1,055 patient-like questions were generated using online query tools (“Also Asked,” “Answer the Public,” and Google's “People Also Ask”) with the keywords “tooth whitening” and “dental bleaching”. All questions were open-ended and formulated to simulate realistic patient scenarios. The initial list was compiled into a single Excel worksheet (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and independently reviewed by two authors (A.H., Y.H.). Duplicates, ambiguous queries, and questions lacking sufficient detail were removed, resulting in a final list of 109 questions. These questions were reviewed for grammatical accuracy and clarity prior to submission to the large language models (LLMs).

The questions were subsequently categorized into five subgroups (Whitening Techniques and Agents (n = 35), Safety and Risks (n = 18), Instructions and Precautions (n = 17), Indications and Contraindications (n = 25), Duration and Cost (n = 14)) to evaluate the key aspects relevant to patients interested in or undergoing tooth whitening, Table 1.

Collection and processing of LLMs responses

The 109 finalized questions were submitted to ChatGPT-4o, Gemini, DeepSeek R1, and Dental GPT within two consecutive days, using the same laptop connected to a wired internet connection to ensure consistency. Separate accounts were created for each platform, and the “New Chat” function was used for every question to minimize potential retention bias. The “regenerate response” option was disabled to ensure a single consistent answer from each model. Responses were independently collected by one author [O A] and stored in 4 separate, anonymized Word documents (A, B, C, and D) to maintain evaluation blindness.

A representative sample question, along with the corresponding full-length responses from all four LLMs, is provided in Supplementary Table S1 to illustrate the nature and variation of the data collected.

Assessment of LLMs' responses

The answers were independently assessed by 2 board-certified specialists trained in using standardized assessment tools to minimize bias. Prior to the main assessment, both evaluators underwent a calibration session using a pilot set of 20 questions and answers not included in the study to ensure a consistent understanding and application of the assessment tools. Any discrepancies in evaluations were resolved through discussion with a third expert to reach a consensus before assessing all AI chatbot responses. This consensus-based approach ensured a unified and reliable final score for each response. The assessment process was focused on the following four key aspects, outlined in Table 2:

1. Usefulness: To measure the usefulness of ChatGPT responses with regard to tooth whitening and dental bleaching, a modification of a previously used scale to grade ChatGPT responses was adopted in the present study (20). The scale was devised to grade the information generated by ChatGPT into 4 scores: (1) Very useful (provides a comprehensive and correct information that are similar to an answer that a specialist in the subject would give); (2) Useful (provides accurate information but missing some vital information); (3) Partially useful (provides some correct and some incorrect information); and (4) Not useful (provides incorrect or misleading information). evaluated on a four-point scale

2. Quality of answers: The quality of ChatGPT responses was assessed using the Global Quality Scale (GQS) (21).

3. Reliability of answers: The reliability of responses was evaluated using the CLEAR (Completeness; Lack of false information; Evidence support; Appropriateness; and Relevance) tool (22). This is a recently validated tool that was conceived to standardize the assessment of AI-based model output by giving each point a score on a scale from 1–5 (i.e., 1 = poor; 2 = fair; 3 = good; 4 = very good; 5 = excellent). The overall CLEAR score ranges from 5–25 and is divided into three categories: scores 5–11 are considered “poor content”; scores 12–18 are considered “average content”; and scores 19–25 are considered “very good” content.

4. Readability was assessed using the Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease (FRE) Score and the Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG) index, both calculated using an online tool (https://readable.com/readability).

Table 2. Assessment tools and scoring criteria for evaluating AI-generated responses on tooth whitening.

Statistical analysis

Data was compiled in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The mean values of assessment scores for each language model were compared across question categories. Given the nonnormal distribution of the data, nonparametric statistical tests were applied. The Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparisons. Given the exploratory nature of the analysis and the absence of primary significant findings, adjustments for multiple comparisons were not applied. Exact p-values are reported where applicable. P-values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Search output and question categorization

A total of 109 questions were subjected to further analysis (Figure 1). The questions were categorized into the following five subgroups: techniques and agents (32.1%, 35 questions), safety and risks (16.5%, 18 questions), instructions and precautions (15.6%, 17 questions), indications and contraindications (23%, 25 questions), duration and cost (12.8%, 14 questions).

Usefulness of AI chatbots responses

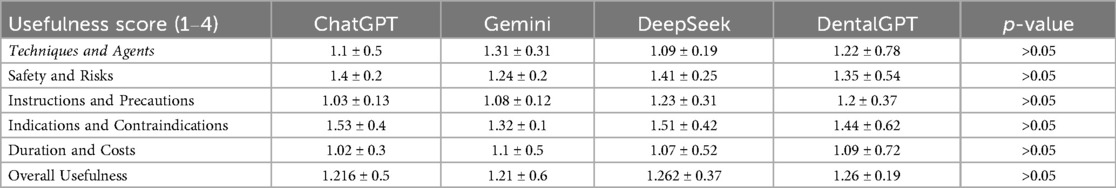

The majority of responses across all language models were rated as “very useful” (68%, n = 75). The mean usefulness score was 1.24 ± 0.3 on a scale where 1 represents “very useful” and 4 indicates “not useful”. No responses were classified as “not useful”. Usefulness scores remained consistently high across all language models, with no statistically significant differences observed between them (p > 0.05, Table 3), nor across the five question domains (p > 0.05, Table 3).

Readability

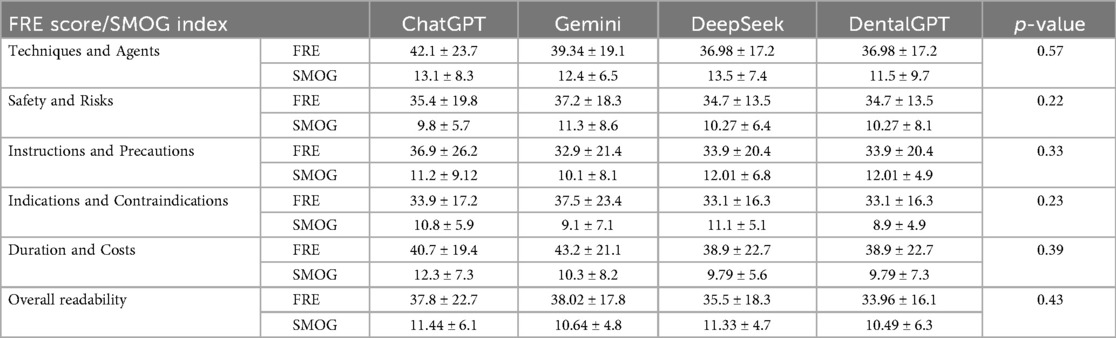

The overall mean Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease (FRE) score was 36.32% ± 21.9 (range: 8–79), which corresponds to a “difficult” reading level. The mean SMOG index was 10.97 ± 7.4 (range: 5.8–17.3), indicating a reading comprehension level equivalent to approximately the 11th grade. No statistically significant differences in readability scores were observed between different language models (p > 0.05, Table 4) or across topic domains (p > 0.05, Table 4).

Table 4. Readability (FRE scores and SMOG indices) of LLMs at answering patients' related questions about tooth whitening.

Quality and reliability

The overall mean Global Quality Scale (GQS) was 3.88 ± 1.96 (range from 1–5), with 42.3% (n = 46) of responses achieving the maximum score of 5. Reliability assessment using the CLEAR tool showed a high mean score of 22.5 ± 2.4 (range: 10–25), with 92.6% (n = 101) of responses classified as having “very good” content. No significant differences were observed in GQS or CLEAR scores between different question domains or language models (p > 0.05, Table 5).

Table 5. Quality (GQS) and reliability (CLEAR score) of LLMs at answering patients' related questions about tooth whitening.

Performance across question domains

Consistent with the overall findings, a sub-analysis comparing performance scores (usefulness, quality, reliability) across the five question domains also revealed no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05 for all inter-domain comparisons). This indicates that the LLMs performed consistently well regardless of whether the topic was clinical (e.g., Safety and Risks) or logistical (e.g., Duration and Cost).

Discussion

This study provides a systematic comparison of multiple large language models—ChatGPT-4o, Gemini, DeepSeek R1, and DentalGPT—in generating responses to patient-centered inquiries about tooth whitening. Overall, our findings indicate that these AI chatbots are capable of producing highly useful, reliable, and largely high-quality information for patients seeking guidance on this popular cosmetic dental procedure. Importantly, the vast majority of responses were rated as “very useful,” with no instances of misleading or “not useful” answers. These results underscore the potential of LLMs to support patient education and complement professional dental counseling in cosmetic dentistry.

The consistently high usefulness scores observed in this study align with prior evaluations of LLMs in oral health, where ChatGPT-4 and Gemini demonstrated strong accuracy in general dental and medical domains (23–29). Unlike earlier studies reporting occasional inaccuracies, hallucinations, or incomplete responses (6, 30–33), the responses generated across all four models in this study were generally accurate, coherent, and relevant. One possible explanation is the more standardized and well-documented nature of tooth whitening procedures compared to complex diagnostic or treatment scenarios in dentistry, which may reduce the likelihood of factual errors.

A primary finding, however, is that the readability of this high-quality information poses a significant barrier. Our results demonstrate that readability levels, were moderate to challenging for the average reader. A Flesch Reading Ease (FRE) score of 36 is classified as “difficult to read,” and a SMOG index of 11 corresponds to a reading grade level of a high school junior or senior. This is substantially higher than the recommended 6th to 8th-grade level for public health materials, which may severely limit accessibility for populations with lower health literacy and potentially exacerbate health disparities. This issue is not isolated to dentistry (18, 34–36); the finding that AI-generated health information is often pitched at an inappropriately high reading level is consistent with observations in other medical fields, including oncology, cardiology, and ophthalmology (30, 32, 37–39). This recurring theme across specialties highlights a systemic challenge for LLMs in healthcare communication. Future research should, therefore, test specific interventional prompts, such as “Explain this in plain language suitable for a 12-year-old,” to determine if LLMs can consistently generate accurate information at an appropriate readability level.

In terms of quality and reliability, the models performed strongly, with nearly half of all responses receiving the highest Global Quality Scale (GQS) rating and the majority classified as “very good” under the CLEAR tool. The high performance across all models suggests that advances in training strategies and reinforcement learning from human feedback have significantly enhanced the clinical reliability of chatbot outputs (40, 41).

Interestingly, despite its domain-specific training, DentalGPT did not significantly outperform the general-purpose models. This may be because tooth whitening is a well-documented, standardized procedure with a vast amount of high-quality information available in the general corpus used to train models like ChatGPT-4o and Gemini. Consequently, general-purpose LLMs can access and synthesize this information effectively. The advantages of a domain-specific model might be more pronounced in highly specialized, niche, or rapidly evolving areas of dentistry where the general corpus is sparse or less reliable. This finding suggests that for common cosmetic procedures, the development of specialized models may offer diminishing returns compared to continual improvement of general-purpose foundations. Furthermore, the consistent performance across all five domains—from technical clinical questions to those about cost and duration—is encouraging. It suggests that these LLMs are robust tools for providing a wide range of information relevant to a patient's decision-making journey, not just the biological or procedural aspects.

Although the results are promising, certain limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study evaluated responses generated in September 2025, and chatbot performance may evolve rapidly with future updates and retraining. Second, while the models produced accurate and reliable answers, they do not replace the nuanced, individualized guidance of a dental professional. For example, patient-specific factors such as pre-existing sensitivity, enamel defects, or expectations regarding whitening outcomes require clinical evaluation that chatbots cannot yet replicate. Third, the study focused exclusively on English-language queries and responses, which limits the generalizability of our findings to non-English speaking populations. Finally, we did not test the reproducibility of the responses, which can vary between sessions or with slight prompt modifications. The consistency of LLM outputs over time is an important area for future research.

Despite these limitations, the findings highlight the growing role of AI chatbots in supplementing patient education in cosmetic dentistry. Tooth whitening is a high-demand procedure where patients often seek information online prior to consulting a dentist. By providing readily accessible, evidence-informed, and generally reliable guidance, LLMs may help dispel misconceptions, promote safe practices, and enhance patient understanding of the risks and benefits of whitening treatments. However, to optimize their utility, future developments should focus on improving readability and tailoring responses to different health literacy levels.

Conclusions

In conclusion, ChatGPT-4o, Gemini, DeepSeek R1, and DentalGPT each demonstrated strong potential as patient education tools for tooth whitening. Their outputs were consistently useful, reliable, and of high quality, though often delivered at a reading level above that of the general population. While these AI tools should not replace professional dental advice, they represent valuable adjuncts for enhancing patient access to accurate and timely information in cosmetic dentistry. Future work should focus on improving readability and directly evaluating how AI-generated information influences patient understanding, decision-making, and clinical outcomes.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for this study in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements, as it did not involve human or animal subjects or any collection of personal data. The research was conducted solely through the analysis of publicly available AI models and simulated patient queries.

Author contributions

AA-H: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. OS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fdgth.2025.1710159/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Carey CM. Tooth whitening: what we now know. J Evid Based Dent Pract. (2014) 14:70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2014.02.006

2. Abidia RF, El-Hejazi AA, Azam A, Al-Qhatani S, Al-Mugbel K, AlSulami M, et al. In vitro comparison of natural tooth-whitening remedies and professional tooth-whitening systems. Saudi Dent J. (2023) 35(2):165–71. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2023.01.007

3. Grand View Research. Teeth Whitening Market Size, Value, Growth Report, 2030. Grand View Research (2023). Available online at: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/teeth-whitening-market-report (Accessed October 17, 2025).

4. Finney Rutten LJ, Blake KD, Greenberg-Worisek AJ, Allen SV, Moser RP, Hesse BW. Online health information seeking among US adults: measuring progress toward a healthy people 2020 objective. Public Health Rep. (2019) 134(6):617–25. doi: 10.1177/0033354919874074

5. Kung TH, Cheatham M, Medenilla A, Sillos C, Leon L, Elepaño C, et al. Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLoS Digit Health. (2023) 2(2):e0000198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pdig.0000198

6. Sallam M. ChatGPT utility in healthcare education, research, and practice: systematic review on the promising perspectives and valid concerns. Healthcare (Basel). (2023) 11(6):887. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11060887

7. Dermata A, Arhakis A, Makrygiannakis MA, Giannakopoulos K, Kaklamanos EG. Evaluating the evidence-based potential of six large language models in paediatric dentistry: a comparative study on generative artificial intelligence. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. (2025) 26(3):527–35. doi: 10.1007/s40368-025-00935-z

8. OpenAI. ChatGPT: Optimizing Language Models for Dialogue. San Francisco (CA): OpenAI (2022). Available online at: https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt (Accessed August 29, 2025).

9. Google DeepMind. Gemini: Our Largest and Most Capable AI Model (December 6, 2023). Mountain View (CA): Google DeepMind. Available online at: https://blog.google/technology/ai/google-gemini-ai/ (Accessed August 29, 2025).

10. Reuters. China’s DeepSeek Releases an Update to its R1 Reasoning Model (May 29, 2025). Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/technology/chinas-deepseek-releases-update-its-r1-reasoning-model-2025-05-29/ (Accessed August 29, 2025).

11. Özcivelek T, Özcan B. Comparative evaluation of responses from DeepSeek-R1, ChatGPT-o1, ChatGPT-4, and dental GPT chatbots to patient inquiries about dental and maxillofacial prostheses. BMC Oral Health. (2025) 25(1):871. doi: 10.1186/s12903-025-05263-9

12. Nori H, King N, McKinney SM, Carignan D, Horvitz E. Capabilities of GPT-4 on Medical Challenge Problems. arXiv (Preprint). 2303.13375. Available online at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.13375 (Accessed March 27, 2023).

13. Omar M, Nassar S, Hijazi K, Glicksberg BS, Nadkarni GN, Klang E. Generating credible referenced medical research: a comparative study of OpenAI’s GPT-4 and Google's Gemini. Comput Biol Med. (2025) 185:109545. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.109545

14. Pal A, Sankarasubbu M. Gemini Goes to Med School: Exploring the Capabilities of Multimodal Large Language Models on Medical Challenge Problems and Hallucinations. arXiv (Preprint). 2402.07023. Available online at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.07023 (Accessed February 11, 2024)

15. Arpaci A, Ozturk AU, Okur I, Sadry S. Evaluation of the accuracy of ChatGPT-4 and gemini’s responses to the world dental federation’s frequently asked questions on oral health. BMC Oral Health. (2025) 25(1):1293. doi: 10.1186/s12903-025-06624-9

16. Molena KF, Macedo AP, Ijaz A, Carvalho FK, Gallo MJD, Silva FWGP, et al. Assessing the accuracy, completeness, and reliability of artificial intelligence-generated responses in dentistry: a pilot study evaluating the ChatGPT model. Cureus. (2024) 16(7):e65658. doi: 10.7759/cureus.65658

17. Huo B, Boyle A, Marfo N, Tangamornsuksan W, Steen JP, McKechnie T, et al. Large language models for chatbot health advice studies: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. (2025) 8(2):e2457879. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.57879

18. Taymour N, Fouda SM, Abdelrahaman HH, Hassan MG. Performance of the ChatGPT-3.5, ChatGPT-4, and Google Gemini large language models in responding to dental implantology inquiries. J Prosthet Dent. (2025) (in press). doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2024.12.016

19. Tay JRH, Chow DY, Lim YRI, Ng E. Enhancing patient-centered information on implant dentistry through prompt engineering: a comparison of four large language models. Front Oral Health. (2025) 6:1566221. doi: 10.3389/froh.2025.1566221

20. Yeo YH, Samaan JS, Ng WH, Ting PS, Trivedi H, Vipani A, et al. Assessing the performance of ChatGPT in answering questions regarding cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol Hepatol. (2023) 29(3):721–32. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2023.0089

21. Bernard A, Langille M, Hughes S, Rose C, Leddin D, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S. A systematic review of patient inflammatory bowel disease information resources on the world wide web. Am J Gastroenterol. (2007) 102(9):2070–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01325.x

22. Sallam M, Al-Salahat K, Al-Ajlouni E. ChatGPT performance in diagnostic clinical microbiology laboratory-oriented case scenarios. Cureus. (2023) 15(12):e50629. doi: 10.7759/cureus.50629

23. Xu Y, Liu X, Cao X, Huang C, Liu E, Qian S, et al. Artificial intelligence: a powerful paradigm for scientific research. Innovation (Camb). (2021) 2(4):100179. doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100179

24. Hassona Y. Applications of artificial intelligence in special care dentistry. Spec Care Dentist. (2024) 44(3):952–3. doi: 10.1111/scd.12911

25. Alqahtani T, Badreldin HA, Alrashed M, Alshaya AI, Alghamdi SS, Saleh KB, et al. The emergent role of artificial intelligence, natural learning processing, and large language models in higher education and research. Res Social Adm Pharm. (2023) 19(8):1236–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2023.05.016

26. De Angelis L, Baglivo F, Arzilli G, Privitera GP, Ferragina P, Tozzi AE, et al. ChatGPT and the rise of large language models: the new AI-driven infodemic threat in public health. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1166120. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1166120

27. Meo SA, Al-Khlaiwi T, AbuKhalaf AA, Meo AS, Klonoff DC. The scientific knowledge of Bard and ChatGPT in endocrinology, diabetes, and diabetes technology: multiple-choice questions examination-based performance. J Diabetes Sci Technol. (2023) 17(5):705–10. doi: 10.1177/19322968231203987

28. Cheng K, Sun Z, He Y, Gu S, Wu H. The potential impact of ChatGPT/GPT-4 on surgery: will it topple the profession of surgeons? Int J Surg. (2023) 109(5):1545–7. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000388

29. Kluger N. Potential applications of ChatGPT in dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2023) 37(7):e941–2. doi: 10.1111/jdv.19152

30. Ting DSJ, Tan TF, Ting DSW. ChatGPT in ophthalmology: the dawn of a new era? Eye (Lond). (2024) 38(1):4–7. doi: 10.1038/s41433-023-02619-4

31. Alhaidry HM, Fatani B, Alrayes JO, Almana AM, Alfhaed NK. ChatGPT in dentistry: a comprehensive review. Cureus. (2023) 15(4):e38317. doi: 10.7759/cureus.38317

32. Blum J, Menta AK, Zhao X, Yang VB, Gouda MA, Subbiah V. Pearls and pitfalls of ChatGPT in medical oncology. Trends Cancer. (2023) 9(10):788–90. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2023.06.007

33. Munoz-Zuluaga C, Zhao Z, Wang F, Greenblatt MB, Yang HS. Assessing the accuracy and clinical utility of ChatGPT in laboratory medicine. Clin Chem. (2023) 69(8):939–40. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvad058

34. DeTemple DE, Meine TC. Comparison of the readability of ChatGPT and Bard in medical communication: a meta-analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2025) 25(1):325. doi: 10.1186/s12911-025-03035-2

35. Alnsour MM, Alenezi R, Barakat M, Al-omari M. Assessing ChatGPT’s suitability in responding to the public’s inquires on the effects of smoking on oral health. BMC Oral Health. (2025) 25(1):1207. doi: 10.1186/s12903-025-06377-5

36. Sivaramakrishnan G, Almuqahwi M, Ansari S, Lubbad M, Alagamawy E, Sridharan K. Assessing the power of AI: a comparative evaluation of large language models in generating patient education materials in dentistry. BDJ Open. (2025) 11:59. doi: 10.1038/s41405-025-00349-1

37. Elkarmi R, Abu-Ghazaleh S, Sonbol H, Haha O, Al-Haddad A, Hassona Y. ChatGPT for parents’ education about early childhood caries: a friend or foe? Int J Paediatr Dent. (2025) 35(4):717–24. doi: 10.1111/ipd.13283

38. Hassona Y, Alqaisi D, Al-Haddad A, Georgakopoulou EA, Malamos D, Alrashdan MS, et al. How good is ChatGPT at answering patients’ questions related to early detection of oral (mouth) cancer? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. (2024) 138(2):269–78. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2024.04.010

39. Kurapati SS, Barnett DJ, Yaghy A, Sabet CJ, Younessi DN, Nguyen D, et al. Eyes on the text: assessing readability of artificial intelligence and ophthalmologist responses to patient surgery queries. Ophthalmologica. (2025) 248(3):149–59. doi: 10.1159/000544917

40. Diniz-Freitas M, Rivas-Mundiña B, García-Iglesias JR, García-Mato E, Diz-Dios P. How ChatGPT performs in oral medicine: the case of oral potentially malignant disorders. Oral Dis. (2024) 30(4):1912–8. doi: 10.1111/odi.14750

Keywords: tooth whitening, dental bleaching, AI, large language models, patient education, cosmetic dentistry

Citation: Al-Haddad A, Alrabadi M, Saadeh O, Alrabadi G and Hassona Y (2025) The evaluation of tooth whitening from a perspective of artificial intelligence: a comparative analytical study. Front. Digit. Health 7:1710159. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2025.1710159

Received: 23 September 2025; Accepted: 7 November 2025;

Published: 24 November 2025.

Edited by:

Aikaterini Kassavou, University of Bedfordshire, United KingdomReviewed by:

Noha Taymour, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Saudi ArabiaKelly Fernanda Molena, Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil

Copyright: © 2025 Al-Haddad, Alrabadi, Saadeh, Alrabadi and Hassona. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yazan Hassona, eWF6YW5AanUuZWR1Lmpv

Alaa Al-Haddad

Alaa Al-Haddad Mikel Alrabadi1

Mikel Alrabadi1 Yazan Hassona

Yazan Hassona