- 1Institute of Human Genetics, University of Leipzig Medical Center, Leipzig, Germany

- 2Department of Pediatrics, University of Leipzig Medical Center, Leipzig, Germany

Background: Cystic Fibrosis (CF) is primarily diagnosed in Germany through newborn screening (NS) using immunoreactive trypsinogen (IRT)/Pancreatitis-Associated Protein (PAP) measurements and genetic testing for common CFTR gene variants. While this method is effective in identifying the most frequent mutations, it may overlook complex alleles, which can impact phenotype and treatment efficacy.

Case Presentation: We report the case of a five-year-old girl diagnosed with CF through NS, initially identified as homozygous for the F508del variant. Despite early Orkambi therapy, her response was suboptimal, with high sweat chloride levels and recurrent respiratory infections. Re-sequencing with a next-generation sequencing (NGS) panel revealed an additional undetected heterozygous pathogenic variant. Upon switching to elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor (ETI), sweat chloride levels significantly improved.

Conclusion: Standard genetic screening methods may fail to detect complex alleles, leading to misinterpretation of genotype and suboptimal treatment choices. This case highlights the necessity of comprehensive genetic analysis in patients with unexpected therapy responses. When CFTR modulator therapy does not yield the expected improvements, re-sequencing should be considered to optimize precision medicine approaches for CF.

Introduction

In Germany, Cystic Fibrosis (CF) is diagnosed by Newborn Screening (NS) comprising immunoreactive trypsinogen (IRT)/Pancreatitis-Associated Protein (PAP) measurements, followed by targeted genetic testing for the most common CFTR variants (Heinemann et al., 2016). Nowadays, the majority of patients are diagnosed via NS within the first month of their lives (Nährlich et al., 2023).

CF has a strong genotype-phenotype correlation, with variants sorted into seven different classes depending on their pathomechanism (Boeck and Amaral, 2016). Therapy of CF was revolutionised with the implementation of CFTR modulators by directly addressing these molecular defects, showing particular efficacy for class II (misfolding) and III (chloride channel gating) variants (Ensinck and Carlon, 2022). Precise genotyping is therefore essential for selecting the most effective modulator therapy. When identifying the most common variant F508del in a homozygous state, the combination of lumacaftor and ivacaftor (trade name: Orkambi) is a possible option for treatment starting from 1 year of age. Another therapeutic option consisting of the three compounds elexacaftor (E), tezacaftor (T) and ivacaftor (I) (ETI, trade name: Kaftrio/Trikafta) is approved for people with CF (pwCF) 2 years and older carrying at least one F508del variant.

A complex allele arises when multiple variants are located in cis on the same CFTR allele. For CFTR, the presence of a second variant additionally to the in-cis-variant can have impact on the clinical phenotype (El-Seedy and Ladeveze, 2024). However, little is known about the general epidemiology and functional relevance of complex alleles. A systematic evaluation from Russia identified 8,2% of pwCF with the complex allele [L467F; F508del] in F508del homozygous patients (Kondratyeva et al., 2022), characterised by an additional missense substitution [p. (Leu467Phe)] in-cis to F508del. This complex allele in homozygous state showed reduced response to ETI in intestinal organoids (Efremova et al., 2024).

Using standard genetic screening methods, complex alleles such as [L467F; F508del] would be missed completely. Therefore, testing for only the most common variants can lead to false results followed by ineffective therapeutic recommendations.

Here we present a case of now five-year-old girl, initially diagnosed with CF by NS and DNA testing, identifying homozygosity for the most common F508del variant in CFTR, with no other variant detected. Using our previously described next-generation (NGS) sequencing panel for identification of variants in the entire CFTR locus (Ahting et al., 2024), we subsequently identified another heterozygous pathogenic variant that was previously missed (Paolis et al., 2023; Chevalier and Hinzpeter, 2020).

Clinical presentation

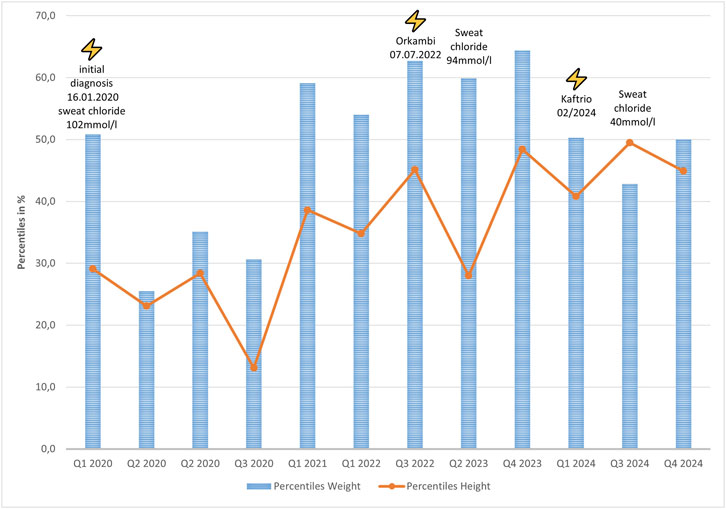

The girl was born in 2020 after uneventful pregnancy (born 38+2 weeks, weight: 3,34 ± 0,07 kg, height: 49 ± 0.93 cm, head circumference: 33,5 ± 0,7 cm). CF diagnosis was drawn at postnatal day 12, after positive IRT-PAP-DNA screening (F508del homozygous, Figure 1A) and confirmation by sweat chloride testing (102 mmol/L). Pancreatic elastase was below 50 μg/g faeces, so pancreatic insufficiency was diagnosed and treatment with enzyme substitution was started immediately. Treatment with Orkambi was initiated in July 2022. While she developed normally (Figure 1), sweat chloride levels were only reduced to 94 mmol/L, still in the highly pathological range. The patient suffered of recurrent airway infections. In 2024 at the age of four, modulator therapy was switched to ETI due to its approval. Weight and height development was still normal, while sweat chloride levels reduced to 40 mmol/L. Pancreatic insufficiency persisted in the presence of modulator therapy so far. Her FEV1 was measured at 122%, indicating an above-average pulmonary function.

Figure 1. Weight (blue) and height (orange) percentile development of the patient with starting points of modulator therapy and measured sweat chloride concentrations.

Genetic testing results

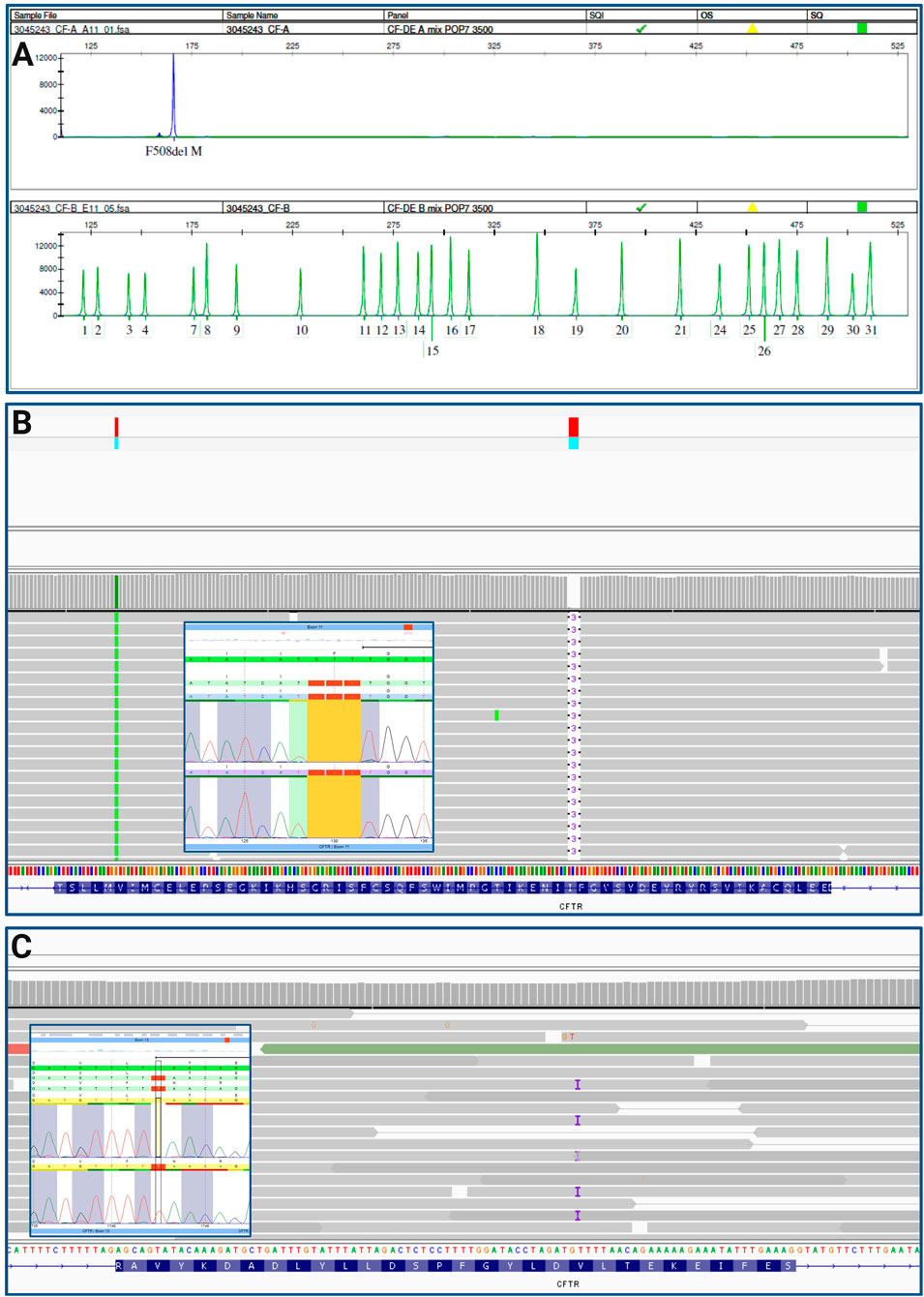

For diagnosis of CF, genetic testing was performed at the age of 19 days via CF Strip Assay® (ViennaLab, Vienna, Austria), according to manufacturer’s instructions. We identified the homozygous pathogenic variant NM_000492.4: c.1521_1523delCTT, p. (Phe508del) (legacy name F508del) and confirmed it using the Elucigene CF kit for the detection of the 31 most frequent variants in the European population (Elucigene®, Delta Diagnostics, Manchester, United Kingdom, according to manufacturer’s instructions) (Figure 2A, upper panel). The modulator Orkambi was prescribed to the individual on the assumption of the homozygous state of the F508del variant. Within a research project investigating frequency and relevance of complex alleles, we were looking into pwCF responding well to ETI treatment therapy and not carrying a complex allele (responder positive controls). When resequencing the individual using our NGS custom panel (Ahting et al., 2024), we detected an additional heterozygous variant NM_000492.4:c.1742dup, p. (Leu581Phefs*8) in exon 13 of CFTR (Figure 2B). To confirm these findings, Sanger sequencing was conducted (Figure 2C). The complex allele carrying the two variants [p. (Phe508del); p. (Leu581Phefs*8)] will most likely be degraded via nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD), due to the introduction of a premature stop codon, resulting in a class I variant. This type of variants cause the assembly of the CFTR protein to be stopped prematurely, so that no CFTR channel can be formed at all (Bell et al., 2020). Variants were classified according to the latest criteria of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (Richards et al., 2015), as well as ACGS Best Practice Guidelines for Variant Classification 2024 (Durkie et al., 2025) using Varvis software (Limbus, Rostock, Germany).

Figure 2. (A) CF Elucigene assay, 31 most common variants in CFTR were tested, detected F508del homozygous (blue peak, upper panel), green peaks indicate absence of a variant; (B) IGV trace of F508del variant homozygous and Sanger sequencing results; (C) IGV trace of variant (C) 1742dup, p. (Leu581Phefs*8) and according Sanger sequencing results.

Conclusion

Through the pathomechanism of the complex allele, the therapy with Orkambi led to fewer improvements as expected at the beginning of treatment. Screening for the most common variants is cost-effective and provides results within a few days. However, since this approach does not detect all variants, it may miss complex alleles, and ultimately result in ineffective therapy. Whenever patients do not respond to modulators as expected, a re-sequencing should be considered. Furthermore, discontinuation of modulator therapy should be discussed and standard CF therapy should be continued. Newborn genomic screening (NBGS) offers a promising expansion of conventional programs by enabling broader detection of pathogenic variants and accelerating diagnosis. While current NBGS technologies cannot yet fully replace traditional methods, integrating both approaches can substantially improve screening accuracy, efficiency, and equity across populations. Recent advances in cystic fibrosis screening illustrate this progress, as expanded CFTR variant panels and next-generation sequencing now support more inclusive and timely detection, moving toward primary genetic screening (Men et al., 2025; Tariq et al., 2025; Farrell, 2025).

Data availability statement

All relevant data is contained within the article: The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Geschäftsstelle der Ethik-Kommission an der Medizinischen Fakultät der Universität Leipzig c/o Zentrale Poststelle Liebigstraße 18 04103 Leipzig. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

MK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. SA: Writing – review and editing. SB: Writing – review and editing. MH: Writing – review and editing. JH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The study was supported by the Open Access Publishing Fund of Leipzig University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT in order to improve language and readability. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahting, S., Nährlich, L., Held, I., Henn, C., Krill, A., Landwehr, K., et al. (2024). Every CFTR variant counts - target-capture based next-generation-sequencing for molecular diagnosis in the German cf registry. J. Cystic Fibrosis Official Journal Eur. Cyst. Fibros. Soc. 23 (4), 774–781. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2023.10.009

Bell, S. C., Mall, M. A., Gutierrez, H., Macek, M., Madge, S., Davies, J. C., et al. (2020). The future of cystic fibrosis care: a global perspective. Lancet. Respir. Medicine 8 (1), 65–124. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30337-6

Boeck, K. de, and Amaral, M. D. (2016). Progress in therapies for cystic fibrosis. Lancet. Respir. Medicine 4 (8), 662–674. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(16)00023-0

Chevalier, B., and Hinzpeter, A. (2020). The influence of CFTR complex alleles on precision therapy of cystic fibrosis. J. Cystic Fibrosis Official Journal Eur. Cyst. Fibros. Soc. 19 (Suppl. 1), S15–S18. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2019.12.008

Durkie, M., Cassidy, E.-J., Berry, I., Owens, M., Turnbull, C., Scott, R. H., et al. (2025). “ACGS best practice guidelines for variant classification in rare disease,” in Association for clinical genomic science. Available online at: https://www.acgs.uk.com/quality/best-practice-guidelines/17 October, 2025).

Efremova, A., Melyanovskaya, Y., Krasnova, M., Voronkova, A., Mokrousova, D., Zhekaite, E., et al. (2024). Estimation of chloride channel residual function and assessment of targeted drugs efficiency in the presence of a complex allele L467F;F508del in the CFTR gene. Int. Journal Molecular Sciences 25 (19), 10424. doi:10.3390/ijms251910424

El-Seedy, A., and Ladeveze, V. (2024). CFTR complex alleles and phenotypic variability in cystic fibrosis disease. Cell. Molecular Biology (Noisy-le-Grand, France) 70 (8), 244–260. doi:10.14715/cmb/2024.70.8.33

Ensinck, M. M., and Carlon, M. S. (2022). One size does not fit all: the past, present and future of cystic fibrosis causal therapies. Cells 11 (12), 1868. doi:10.3390/cells11121868

Farrell, P. M. (2025). Reflections on 50 years of cystic fibrosis newborn screening experience with critical perspectives, assessment of current status, and predictions for future improvements. Int. Journal Neonatal Screening 11 (4), 88. doi:10.3390/ijns11040088

Heinemann, M. L., Hentschel, J., Becker, S., Prenzel, F., Henn, C., Kiess, W., et al. (2016). Einführung des deutschlandweiten Neugeborenenscreenings für Mukoviszidose. LaboratoriumsMedizin 40 (6), 373–384. doi:10.1515/labmed-2016-0062

Kondratyeva, E., Efremova, A., Melyanovskaya, Y., Voronkova, A., Polyakov, A., Bulatenko, N., et al. (2022). Evaluation of the complex p.Leu467Phe;Phe508del CFTR allele in the intestinal organoids model: implications for therapy. Int. Journal Molecular Sciences 23 (18), 10377. doi:10.3390/ijms231810377

Men, S., Wang, Z., Liu, S., Tang, X., Liu, S., Zhao, Y., et al. (2025). Integrating newborn genetic screening with traditional screening to improve newborn screening. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 38 (1), 2583588. doi:10.1080/14767058.2025.2583588

Nährlich, L., Burkhart, M., and Wosniok, J. (2023). German cystic fibrosis registry annual report 2023.

Paolis, E. de, Tilocca, B., Lombardi, C., Bonis, M. de, Concolino, P., Onori, M. E., et al. (2023). Next-generation sequencing for screening analysis of cystic fibrosis: spectrum and novel variants in a south-central Italian cohort. Genes 14 (8), 1608. doi:10.3390/genes14081608

Richards, S., Aziz, N., Bale, S., Bick, D., Das, S., Gastier-Foster, J., et al. (2015). Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet. Medicine Official Journal Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 17 (5), 405–424. doi:10.1038/gim.2015.30

Keywords: complex allele, newborn screening, next-generation sequencing, CFTR modulators, cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR)

Citation: Karnstedt M, Ahting S, Behrendt S, Hove Mv and Hentschel J (2025) Case Report: Pitfalls in CF screening – targeted variant analysis can cause misleading results and therapy recommendations. Front. Genet. 16:1693573. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2025.1693573

Received: 27 August 2025; Accepted: 19 November 2025;

Published: 01 December 2025.

Edited by:

Youssef Daali, University of Geneva, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Elisa De Paolis, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, ItalyDominik Funken, Hannover Medical School, Germany

Copyright © 2025 Karnstedt, Ahting, Behrendt, Hove and Hentschel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maike Karnstedt, bWFpa2Uua2FybnN0ZWR0QG1lZGl6aW4udW5pLWxlaXB6aWcuZGU=

Maike Karnstedt

Maike Karnstedt Simone Ahting1

Simone Ahting1