- 1Amref Health Africa in Ethiopia, Gambella Field Office, Gambela, Ethiopia

- 2Department of Maternal and Child Health, Melk Oda G/Hospital, Shashemene, Ethiopia

- 3Department of Public Health, College of Health Science, Salale University, Fiche, Ethiopia

Background: The early termination of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) raises issues for the healthcare system and has the potential to affect public health. Long-acting reversible contraception has now become more widely available and used, although a sizable percentage of women still do not use it. Therefore, this study aims to assess the factors associated with the discontinuation of the LARC method among female users of health facilities in Shashemene town in Oromia, Ethiopia.

Methods: A facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted in Shashemene town involving 410 study participants from nine facilities. The study participants were selected by using a systematic sampling method. The data were collected by using structured interviewer-administered questionnaires, entered into EpiData version 4.6.0.2, and exported to SPSS version 25 for analysis. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regressions were used to examine the association between independent variables and LARC discontinuation. The results were presented using the odds ratio at 95% CI. p < 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

Result: The overall prevalence of women who discontinued the LARC method before the due date was 57.2%. Having an occupation as a housewife, desire for pregnancy, unwarned side effects, effectiveness, and dissatisfaction with the service provided were the factors positively associated with the discontinuation of the contraception.

Conclusion: The prevalence of the discontinuation of LARCs was high. Pre-insertion, effective counseling about the benefits, follow-up care, management of side effects, and client reassurance are recommended.

Introduction

An unintended pregnancy is defined as a pregnancy that occurs when no children or no additional children are desired (unwanted) or earlier than desired (mistimed) (1). It is associated with an increased risk of problems for the mother and the baby. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 74 million women in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) experience unintended pregnancies each year. This results in 47,000 maternal fatalities and 25 million unsafe abortions each year, leading to 25 million unsafe abortions and 47,000 maternal deaths every year (2).

One of the most affordable health promotions to lower mother and child mortality by approximately 30% and 10%, respectively, is the use of modern contraceptive techniques (3). Therefore, ensuring that every pregnancy is intended and every birth is safe can prevent the vast majority of maternal and infant deaths (4). Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) are a type of modern birth control method that prevents unintended conception for an extended period without requiring additional effort from the client for at least 3 years of continuous use (5). Intrauterine copper devices (IUCDs), levonorgestrel (LNG)-releasing intrauterine system, and LNG-releasing and etonogestrel (ENG)-releasing subdermal implants are categorized as LARC methods (6–8). LARC discontinuation refers to the removal of the device used, ceasing its usage, or switching to other methods for any reason before completion of the duration (1).

Despite the improvement in the availability and utilization of long-acting reversible contraception, early discontinuation has become a major problem (9). In low-income countries (LICs), a systematic review reported a 20% discontinuation rate of LARCs within 1 year of insertion (10). In a study conducted on 21 LICs, LARCs comprised only 10% or less, of which 9% of implant users and 15% of IUCD users discontinued the method within the first year of use (11). In addition, 13.1, 26.3, and 36.7% of IUD users discontinued at the first 12, 24, and 36 months, respectively (12). The Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey (EDHS) revealed that the overall discontinuation rate of contraceptives at 12 months was 35%, of which 13% were IUD users and 11% were implant users (13). Other studies conducted in Ethiopia reported discontinuation rates of LARC use at 20% (14), 36.94% (15), 50% (16), and 66.3% (17).

Contraceptive discontinuation may be associated with external factors and individual and/or partner factors (18–20). Studies suggest that the quality of family planning services and obstetric factors such as past abortion history, number of living children, desire for more children, preferred family size, sex preference, irregular vaginal bleeding, lower abdominal pain, and abnormal vaginal discharge were linked to LARC discontinuation (14, 21–26). Sociodemographic variables, such as age, marital status, educational status, and religious concern, were found to influence LARC discontinuation. Regarding method-related variables, studies revealed that side effects (11, 14), counseling, satisfaction with the service given, and information about family planning were also identified as factors associated with LARC discontinuation (17, 21–23).

In Ethiopia, providing LARCs is a free and highly effective method for preventing unintended pregnancies (27). A woman who discontinues LARCs after 3 months faces an increased risk of unintended pregnancy by 11.6–42.3% (11). LARC discontinuation can lead to an increased fertility rate, unintended pregnancy, and associated complications (11, 28). The high LARC discontinuation rate coupled with low uptake results in a significant challenge to achieving the targeted contraceptive prevalence in Ethiopia (29).

Depending on cultural differences and time elapse, the causes for LARC discontinuation may be extremely contextual. Additionally, reducing the discontinuance of LARCs is a great way to prevent or at least minimize unintended pregnancies (30). In countries like Ethiopia, where there is high fertility and an unmet need for family planning (13), it is important to understand how long women continue to use LARCs and what factors associated with its discontinuation help improve the reproductive health of women. However, there is limited information regarding the methods of discontinuing LARCs and associated factors in the study area. Therefore, the main aim of this study was to determine the discontinuation of LARCs and its associated factors among reproductive-age women in Shashemene town, Oromia, Ethiopia.

Method and materials

Study area and period

The study was conducted in Shashemene town involving women aged 15–49 years. Shashemene town is the capital city of the West Arsi zone in the Oromia Region, which is 250 km far from Addis Ababa. The total town population is estimated to be 286,447, of which 49.5% are females and 34.7% are reproductive-age women. Currently, the town has two public hospitals, five health centers, two non-governmental organization (NGO) clinics, one private hospital, more than 50 private clinics, and pharmacies providing health services. Among these health facilities, all hospitals, health centers, private hospitals, NGO clinics, and nine private clinics provide LARC services. The study was conducted from May 16 to June 16, 2022.

Study design

An institution-based cross-sectional study design was applied.

Populations

Source population

All reproductive-age women who were using LARCs in the health facilities of Shashemene town.

Study population

All women who were current users of LARCs and visited selected health facilities of Shashemene town for contraceptive-related issues during the study period.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria comprise all reproductive-age women who have been using LARCs for at least 12 months and visited the selected health facilities for any issues concerning the method before completion of the duration (e.g., removal, side effects, and follow-up during the actual data collection period). In addition. women who lived in the study area for at least 6 months were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria comprise all women who have used LARCs outside of Shashemene town and come to the study area for the removal service. Women who visited to replace Implanon with Jadelles, Jadelles with Implanon, and implants with IUCD, or vice versa, were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination

The required sample size was calculated by using the following population proportion formula:

where n is the minimum sample size; p = 39% prevalence of Implanon discontinuation in Ambo town (31); z = 1.96 (95% CI); and d = 0.05 margin of error. Applying the formula by substituting these values into the equation gives 373. Accordingly, 10% was added for the non-response rate, bringing the final sample size to 410.

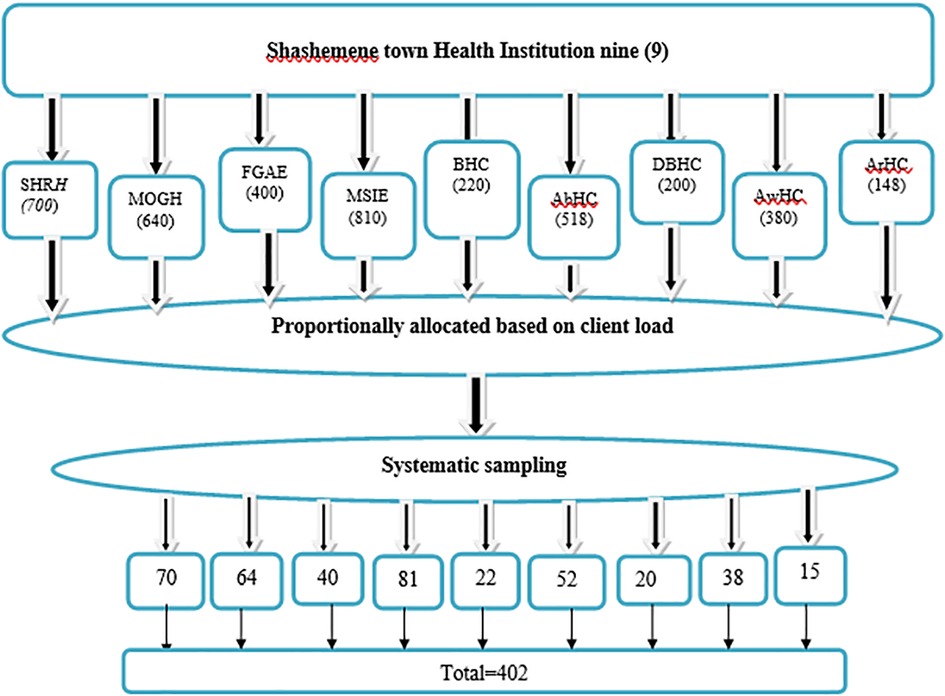

Sampling technique

All public health facilities and non-governmental specialty clinics in Shashemene town, namely, the two public hospitals of Referral Hospital and Melk Oda General Hospital; five public health centers of Abosto, Awasho, Bulchana, Dida Boke, and Arada; and two non-governmental specialty clinics of Family Guidance Association and Marie Stopes International-Shashemene, which provide LARC services, were included in the study. Private health facilities were not included in this study because they were not providing full LARC services (i.e., insertion and removal). To proportionally allocate the calculated sample size, the average client flow for 6 months (i.e., from December 2021 to May 2022) at each health institution was considered before data collection. The information obtained from the 6-month enrolment record of the family planning registration book indicated that a total of 4,016 women booked for LARCs at public and non-governmental specialty clinics. The average 6-month client flow identified from the family planning registration book at Referral Hospital, Melk Oda General Hospital, Abosto HC, Awasho HC, Bulchana HC, Dida Boke HC, Arada HC, Family Guidance Association, and Marie Stopes International-Shashemene were 452, 419, 403, 410, 354, 349, 322, 618, and 689, respectively. The calculated sample size of 410 was proportionally allocated to each facility as 46, 43, 41, 42, 36, 36, 33, 63, and 70. The sampling interval “K” was calculated for each facility as N/n, where “N” stands for the number of women booked and “n” stands for the proportionally allocated sample. The study participants were then identified by a systematic sampling method. The data collectors approached and recruited LARC users who had come to the selected clinics for contraceptive-related reasons. The procedure was continued throughout the data collection period until the required sample size was achieved (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Six months’ enrolment in health institutions of Shashemene town administration in two public hospitals, five HCs, and two NGO clinics from family planning registration book for sample selection.

Data collection tool and procedure

The data were collected using structured questionnaires through a face-to-face interview, which was developed based on a comprehensive review of different literature related to the topic under study. They were prepared in English and translated to Afan Oromo and Amharic for data collection. The questionnaire contains four parts: sociodemographic characteristics, contraceptive and counseling-related characteristics, health system characteristics, and obstetric-related characteristics. Two days were given to train the data collectors and the supervisor about the study objective, procedure, and research ethical rules. Informed consent was taken from the selected women, and obtaining permission for the data collection took 15–20 min.

Study variables

The dependent variable was the discontinuation of LARCs, while the independent variables were the sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, marital status, religion, occupation, education, and family income; health system-related characteristics, such as availability of health extension workers and time taken to reach health facilities; obstetrics-related characteristics, such as parity, number of living children, history of abortion, desire for pregnancy, and time to get pregnant; contraceptive- and counseling-related characteristics; and information about contraceptive (e.g., history of family planning before use, type of contraceptive used before LARCs, responsible body for choosing LARCs, counseling, and satisfaction with service given).

Data quality assurance

To assure the quality of data, we pre-tested the questionnaire from May 9 to 11, 2022 at 01 Kebele (Hage) Health Center found outside of the actual study area. Five percent of the calculated sample of women was enrolled to check the validity and reliability of the questionnaire. After pre-testing the questionnaire, revisions and amendments were made accordingly. Training on how to interview and check the questionnaire for completeness was given to the data collectors. The supervisors and the principal investigator checked and revised the completeness of the questionnaire and offered necessary feedback to the data collectors.

Data management and analysis

The collected data were entered using EpiData version 4.6 and exported to SPSS 23 software for cleaning, recoding, categorizing, and analyzing. A bivariate analysis was done to see the association between independent and outcome variables. Variables with a p-value of 0.2 during the bivariate analysis were included in the multiple logistic regression analysis to assess the relative effect of confounding variables. The outcome variable is categorical; hence, the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) was calculated using a multiple logistic regression model. After the multivariate analysis had been done, the AOR was used to measure the strength of the association between the dependent and independent variables, while the 95% CI and p-value were used to assess whether the association was significant.

Ethical consideration

An ethical assurance letter was received from SLU College of Health Sciences, Department of Public Health. It was presented to the health office of Shashemene town to ask for official permission to undertake research activities in the selected health facility. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant after the investigator had explained the nature, purpose, and procedure of the study. The signature of each participant was used on the willingness confirmation. The entire study's participants were informed that data would be kept private and confidential and used only for research purposes. The participants were also assured that they had the right to refuse or withdraw if they were not comfortable at any time.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

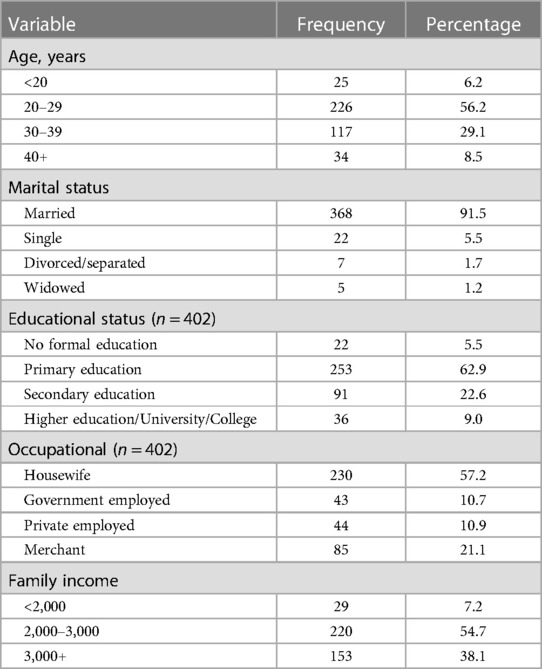

A total of 402 women responded to the questionnaire, forming a response rate of 98%. The mean age of the respondents was 26 years (±4.6). Approximately 241 (60.0%) were Oromo by ethnicity, and 150 (37.3%) were Muslims by religion. Most of the respondents, 268 (91.5%), were married. Two hundred fifty-three (62.9%) respondents attended secondary education. Regarding occupation, the majority of the respondents, 230 (57.2%), were housewives. More of the respondents have a monthly income of 2,000–3,000 ETB per month (Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of long-acting reversible contraceptive users in the health facilities of Shashemene town, Southern Ethiopia, 2022 (n = 402).

Health system-related characteristics

The majority of women, 342 (85.1%), had access to health extension workers in their catchment, and more than half of the women, 252 (62.7%), were living within 30–60 min walking distance from the health facilities.

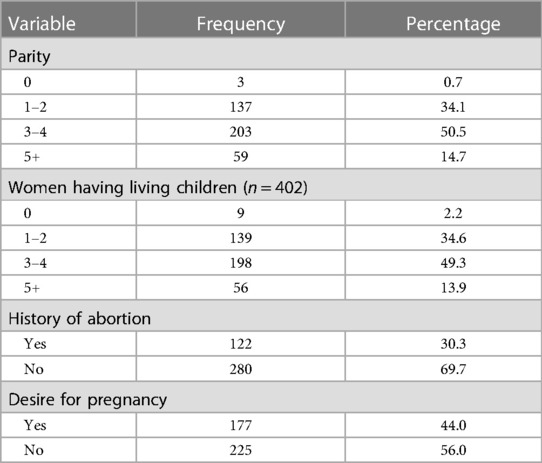

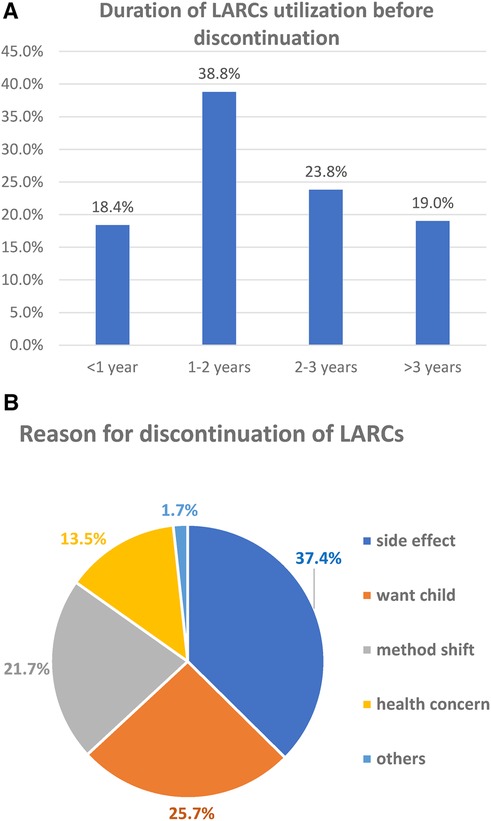

Obstetric-related characteristics

Among the women who ever used LARCs, only three (1%) had no history of live birth. Nine (2.2%) had no child; 122 (30.3%) had a history of abortion; and 177 (44%) desired to become pregnant (Table 2).

Table 2. Obstetric history of women who used LARC in 2021/2022 in Shashemene town, Oromia, South Ethiopia, 2022 (n = 402).

Contraceptive and counseling-related characteristics

From the total number of women interviewed, approximately three-fourths (74.4%) used other contraceptive methods before LARCs. For instance, of these women, approximately 150 (50.3%) had been using injectables. Regarding method selection, nearly 2/3 (64.7%) of the women decided to use LARCs by their own choice. Among the types of LARCs, 220 (54.7%) women used Implanon. Among the total study participants, the number of women who were counseled about the benefits, side effects, and effectiveness of LARCs was 199 (49.5%), 203 (50.5%), and 227 (56.5%), respectively. One hundred ninety-five (48.5%) of the respondents mentioned having been satisfied with the service given before the insertion (Table 3).

Table 3. Contraceptive and counseling-related characteristics of women who used LARCs in 2021/2022 in Shashemene town, Oromia, Southern Ethiopia, 2022 (n = 402).

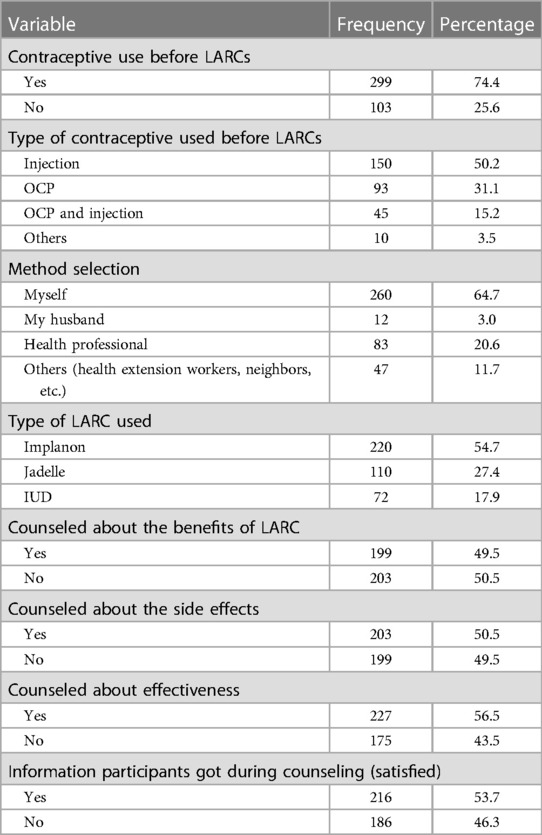

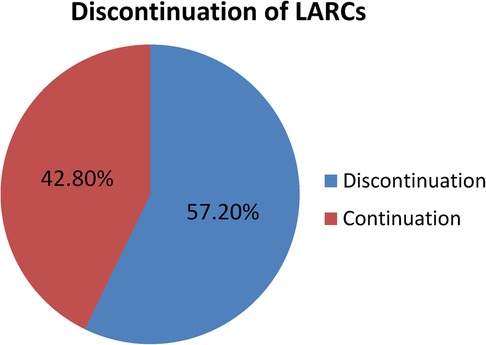

Magnitude of long-acting reversible contraceptive discontinuation

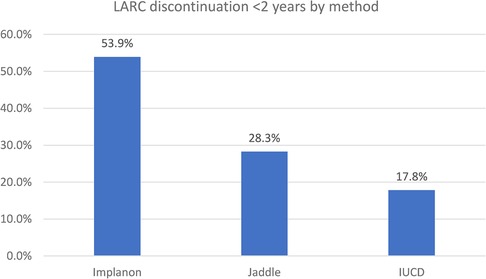

The study revealed that, among the study participants who ever used LARCs, 18.4%, 57.2%, and 81% of women discontinued the service at 12, 24, and 36 months, respectively. Moreover, 38.8% and 23.8% of women discontinued it at 12–24 and 24–36 months, respectively. Among the study participants, only 76 (19%) of women used LARCs for at least 36 months. Women who removed LARCs at the due date comprised 7.5%. Regarding the types of LARCs discontinued at 12 months, the proportion of women who discontinued Implanon, Jadelle, and IUCD was 51.4%, 31.1%, and 17.6%, respectively (Figures 2–4).

Figure 2. Proportion of the LARC discontinuation rate among LARC users in Shashemene town, Southern Ethiopia in 2022.

Figure 4. (A) Duration of LARC utilization before discontinuation. (B) Reason for discontinuation among women who ever used LARC in 2021/2022 in Shashemene town, Southern Ethiopia (n = 230).

Reasons for discontinuation of LARCs

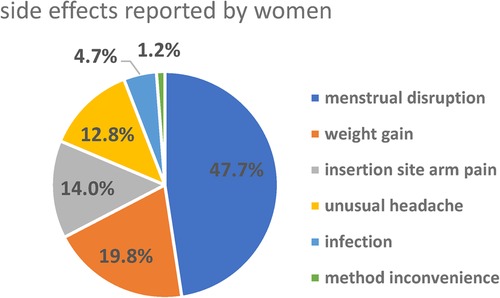

More than one-third (37.4%) of women discontinued LARCs within 3 years of utilization mainly due to emerging side effects. This was followed by 84 (25.7%) who desired to have a child (Figure 5). The most common complaints among women who developed side effects were menstrual disruption (58, 47.7%), weight gain (24, 19.8%), insertion site arm pain (17, 14.0%), unusual headache (16, 12.8%), infection (6, 4.7%), and method inconvenience (1, 1.2%) (Figure 5).

Factors associated with discontinuation of reversible long-acting contraceptives

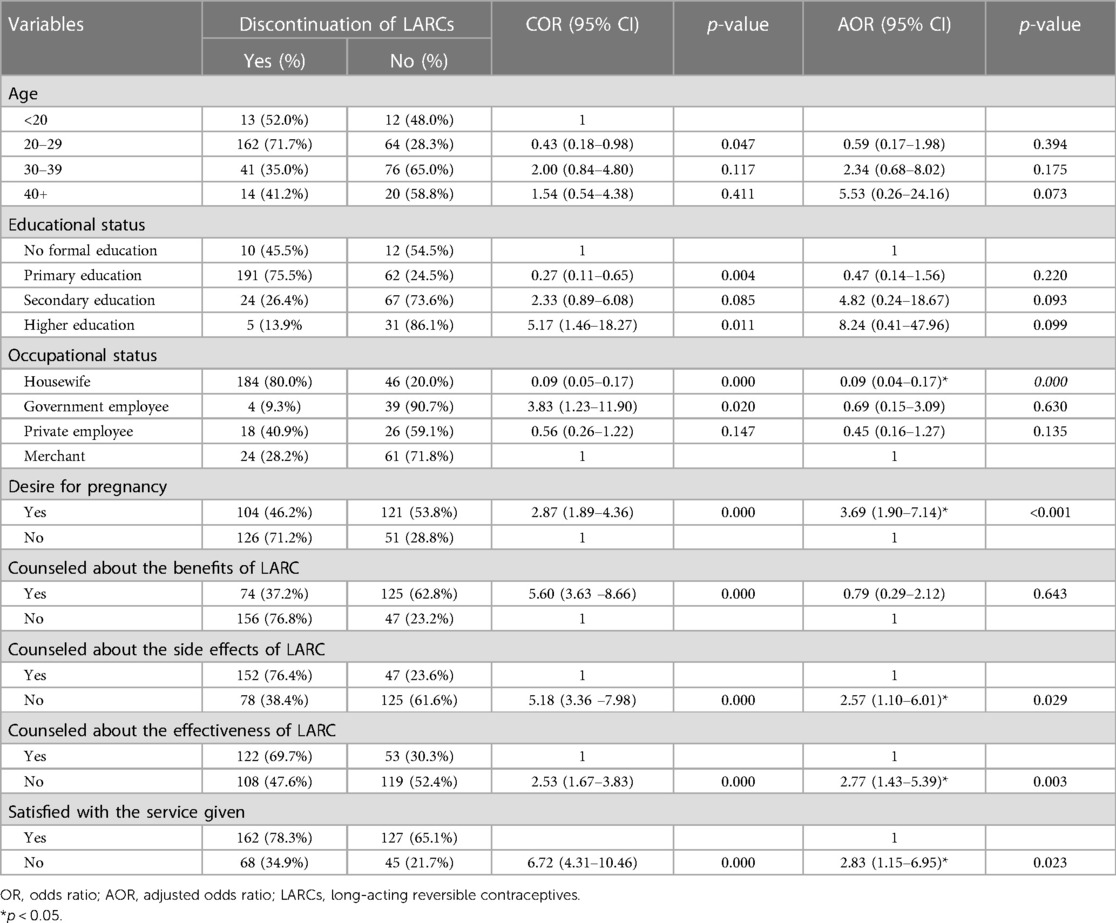

From the bivariate logistic regression analysis, factors such as age, educational status, occupational status, desire for pregnancy, counseling about the benefit of LARCs, counseling on the effectiveness of LARCs, and satisfaction with the service given have a p-value of ≤0.2 and are considered for multivariable logistic regression.

Factors from the bivariate logistic regression analysis with a p-value of ≤0.2 were entered into the multivariable logistic regression analysis. With the multivariable logistic regression analysis, considering a p-value of ≤0.05, the independent predictors of LARC discontinuation were maternal occupation, desire for pregnancy shortly, lack of counseling about the side effects of LARCs, no counseling on the effectiveness of LARCs, and not being satisfied with LARC service provision (Table 4).

Table 4. Bivariate and multivariate analysis of the factors associated with the discontinuation of long-acting reversible contraceptives in Shashemene town Southern Ethiopia, 2022 (n = 402).

Among the sociodemographic variables, the occupational status of women was found to be associated with the discontinuation of LARCs. Women having the occupation of housewives were approximately 90% less likely to discontinue LARCs compared to their merchant counterparts (AOR = 0.09; 95% CI: 0.04, 0.17). The odds of discontinuing LARCs among women who desire to be pregnant were 3.7 times higher than those of their counterparts (AOR = 3.7; 95% CI: 1.90, 7.14). Regarding the counseling status of women as regards the side effects of LARCs, those who did not obtain counseling were 2.6 times more likely to discontinue LARCs compared to their counterparts (AOR = 2.6; 95% CI: 1.10, 6.01). Women who were not counseled about the effectiveness of LARCs were 2.8 times more likely to discontinue LARCs compared to their counterparts (AOR = 2.8; 95% CI: 1.43, 5.39). Women who were not satisfied with the service given were 2.8 times more likely to discontinue LARCs compared to their counterparts (AOR = 2.8; 95% CI: 1.15, 6.95) (Table 4).

Discussions

Nevertheless, 30% of maternal deaths and 10% of infant deaths were reduced by LARCs, which is one of the most practical and cost-effective methods, by ensuring that every pregnancy is desired, and every birth is safe (3, 4). The overall prevalence of LARCs was found to be 18.4%. The current study finding was consistent with the studies conducted at Hawassa City in Southern Ethiopia at 17.7% (29), Bahir Dar City in Northwest Ethiopia at 17.2% (32), and slightly less than the urban public health facilities of Ethiopia (32).

The current study's percentage of LARC discontinuation at 36 months was lower than the 65% found in a study conducted in Debre Tabor, Northwest Ethiopia. This variation could be a result of the subjects or the design of the study. The participants from Debre Tabor, in contrast to the current study, included both urban and rural populations. Urban inhabitants might be more aware of the consequences of contraception. Additionally, efforts may have been taken to enhance counseling, particularly for the women in the current study who had issues with weight gain and menstruation disruption. The result in the current study was also lower than those in studies conducted in Ambo (38.2%) (26) and Arsi zone (25%) (19). This discrepancy might be caused by differences in the study design, sample size, study duration, lack of pre-insertion counseling, satisfaction with the given service, and sociocultural differences of respondents across the study areas.

Among the types of LARCs discontinued in this study, the prevalence of Implanon (41.8%) and IUCD (15.2%) was found to be less than the secondary data analyzed from the EDHS of 61 and 45% by 36 months, respectively (12). This might be caused by the discrepancy in the population structure of the national pattern and variation in the duration of utilization before discontinuation.

The study revealed that the main reasons for the discontinuation of LARCs were the emerging side effects (37.4%), desire to have a child (25.7%), method shift from LARCs to short-acting reversible contraceptive methods (21.7%), and health concern (13.5%). Menstrual disruption (47.7%) was the main side effect faced by discontinuers. Menstrual irregularity may not cause serious health problems but interferes with daily activity, especially sexual activity with their husband. Discontinuation due to side effects was a result of inadequate counseling and information on the possible side effects before and following the insertion of LARCs. Giving adequate counseling and information on the side effects and effectiveness of LARCs likely improves service satisfaction and ensures the continuation of LARCs (13, 16, 29).

Among the independent predictors, the occupational status of women was found to be associated with the discontinuation of LARCs. Women who were housewives were approximately 90% less likely to discontinue LARCs compared to their merchant counterparts. This may be because women having the occupation of merchant might be more likely to be educated and have access to information about modern family planning from different sources.

The current study also revealed that the odds of discontinuing LARC among women who desired to be pregnant shortly were 3.6 times higher than their counterparts. This is consistent with studies conducted in Kenya (33), Bahir Dar City (34), Debre Markos town (35), and Hawassa City (29). This might be because the culture of the community influences married women to bring a child to ensure the ability of the women to bear a child. In addition to this, 62.4% of women in the present study were aged 18–29 years. The majority of the study participants were young; hence, they might intend to have more children and discontinue the contraceptives.

The present study showed that women who were not counseled about the side effects of the LARCs were 2.6 times more likely to discontinue LARCs compared to their counterparts, which is consistent with the study done in Ethiopia through a systematic review (13) of the Hawassa (29) and Kersa districts (36). The current study also revealed that counseling women about the effectiveness of LARCs was negatively associated with LARC discontinuation. The most cited reason for this effect was that effective counseling at the insertion time on the possible side effects of the contraceptive will help the mother accept its possible side effects and minimize its early removal. In addition to this, the use of an appropriate counseling type and timing might also help women cope with minor side effects and strengthen the continuation of the method.

According to the study, women who were unsatisfied were 2.8 times more likely to stop using LARCs than those who were satisfied. This might be the result of incorrect pre-insertion counseling and a lack of seclusion, which led to frustration and quitting. This finding is consistent with that of the study conducted in Makelle City, Dale district, Kambata zone in Southern Ethiopia, and Vietnam (18, 21, 27, 36). This might be due to women's lack of interest in the method chosen. Furthermore, the confidentiality of the service, elucidation of the service supplier, communication skills, and other service provisions during the insertion of LARCs may contribute to LARC discontinuation. Therefore, providing quality reproductive health services to clients can lead to better satisfaction and use of the services.

Limitation

The study's cross-sectional design prevented it from determining the cause-and-effect link. In addition, the possibility of recall bias could not be ruled out, and to study determinant factors, a cross-sectional design study has limitations.

Conclusion

In this study, the overall discontinuation of LARCs among women was high (57.2%). The independent predictors of LARC discontinuation among women were maternal occupation as a housewife, desire for pregnancy, not counseling on side effects, not counseling on the effectiveness of LARCs, and not being satisfied with the service given.

Addressing low community awareness through community-level awareness creation programs and health education ensures long-acting reversible contraceptive use. Providing pre-insertion counseling on side effects, effectiveness, and benefits is also beneficial. Early management and reassurance can decrease discontinuation and enhance retention. A further comprehensive study of this area that includes health professionals and is community-based is recommended.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

This study involving humans was approved by Salale University's Ethical Review Committee. It was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

FL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AT: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The funding source for per diem of data collectors and supervisors of this research was Salale University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/unintendedpregnancy/index.htm (Accessed March 21, 2023).

2. World Health Organization. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news/item/25-10-2019-high-rates-of-unintended-pregnancies-linked-to-gaps-in-family-planning-services-new-who-study (Accessed March 21, 2023).

3. Cleland J, Conde-Agudelo A, Peterson H, Ross J, Tsui A. Contraception and health. Lancet. (2012) 380(9837):56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60609-6

4. USAID. Holistic Approach Enhances Family Planning Programs: Respond’s Experience with the SEED Programming Model. New York: The RESPOND Project (2014). Vol. 27, p. 1–8.

5. Kolman KB, Hadley SK, Jordahliafrato MA. Long-acting reversible contraception: who, what, when, and how. J Fam Pract. (2015) 64(479):84.25671535

6. Peterson HB, Curtis KM. Clinical practice. Long-acting methods of contraception. N Engl J Med. (2005) 353:75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcps050117

7. Long-Acting Reversible Contraception: Implants and Intrauterine Devices. November 2017 2021. (cited March 26, 2023).

8. Wolters Kluwer Health Inc. ACOG Committee opinion no. 450: increasing use of contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices to reduce unintended pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. (2018) 114(6):1434–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c6f965

9. Blane A, Curtis S, Croft T. Does contraceptive discontinuation matter? Quality of care and fertility consequences. In: MEASURE Evaluation Technical Report1999. Chapel Hill: Carolina Population Center: University of North Carolina. (1999).

10. Staveteig S, Mallick L, Winter R. Uptake and discontinuation of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) in low-income countries. In: Stoy D, editor. DHS Analytical Studies 54. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF International (2015).

11. Ali MM, Sadler RK, Cleland J, Ngo TD, Shah IH. Long-term Contraceptive Protection, Discontinuation, and Switching Behavior: Intrauterine Device (IUD) use Dynamics in 14 Developing Countries. London: World Health Organization and Marie Stopes International (2011).

12. Central Statistical Agency. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: CSA and ICF (2017).

13. Gebeyehu NA, Tegegne KD, Biset G, Sewuyew DA, Alemu BW, Yitayew AM. Discontinuation of long-acting reversible contraceptive use and its determinants among women in Ethiopia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. (2022):10. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.979231

14. Ezegwui H, Ikeako L, Ishiekwene C, Oguanua TC. The discontinuation rate and reasons for discontinuation of Implanon at the family planning clinic of University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital (UNTH) Enugu, Nigeria. Niger J Med. (2011) 20:448–50.22288321

15. Weldekidan HA, Lemlem SB, Sinishaw Abebe W, Sori SA. Discontinuation rate of long-acting reversible contraceptives and associated factors among reproductive-age women in Butajira town, Central Ethiopia. Womens Health. (2022) 18:1–11. doi: 10.1177/17455057221104656

16. Adal TG. Early discontinuation of long-acting reversible contraceptives among married and in union women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med Health Sci Res. (2017) 7:113–8.

17. Grunloh DS, Casner T, Secura GM, Peipert JF, Madden T. Characteristics associated with discontinuation of long-acting reversible contraception within the first 6 months of use. Obstet Gynecol. (2013) 122:1214–21. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000435452.86108.59

18. Cohen R, Sheeder J, Teal SB, Cohen R, Sheeder J, Teal SB. Predictors of discontinuation of long-acting reversible contraception before 30 months of use by adolescents and young women. J Adolesc Health. (2019) 65:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.02.020

19. Tesfaye K. Early discontinuation of implant and its associated factors among women who ever used implant in 2017/2018 in Hawassa health centers, Southern Ethiopia, 2019. J Med Case Rep Rev. (2019) 2(7):320–30.

20. Asari VG. Determinants of contraceptive use in Kerala: the case of son/daughter preference. J Fam Welf. (1994) 40:19–25.

21. Bhat PN, Halli SS. Factors influencing continuation of IUD use in South India: evidence from a multivariate analysis. J Biosoc Sci. (1998) 30:297–319. doi: 10.1017/S0021932098002971

22. Nageso A, Gebretsadik A. Discontinuation rate of Implanon and its associated factors among women who ever used Implanon in Dale district, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health. (2018) 18(1):189. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0678-x

23. Park MH, Nguyen TH, Ngo TD. Dynamics of IUD use in Vietnam: implications for family planning services at primary health care level. Int J Womens Health. (2011) 3:429–34. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S26620

24. Youssef RM, Youssef RM. Contraception use and probability of continuation: a community-based survey of women in Southern Jordan. East Mediterr Health J. (2005) 11:545–58.16700369

25. Federal Democratic Republic Ethiopia. National Guideline for Family Planning Services in Ethiopia 2018: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

26. Jain AK, Winfrey W. Contribution of contraceptive discontinuation to unintended births in 36 developing countries. Stud Fam Plann. (2017) 48:269–78. doi: 10.1111/sifp.12023

27. Fekadu GA, Omigbodun AO, Roberts OA, Yalew AW. Factors associated with early long-acting reversible contraceptives discontinuation in Ethiopia: evidence from the 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey. Arch Public Health. (2020) 78(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13690-020-00419-w

28. Bahamondes L, Fernandes A, Monteiro I, Bahamondes MV. Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARCs) methods. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. (2020) 66:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.12.002

29. Abebe BA, Assefa N, Mengistie B. Discontinuation of reversible long-acting contraceptive and associated factors among female users in health facilities of Hawassa City, Southern Ethiopia: cross-sectional study. Open Access J Contracept. (2020) 11:113–23. doi: 10.2147/OAJC.S259978

30. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news/item/25-10-2019-high-rates-of-unintended-pregnancies-linked-to-gaps-in-family-planning-services-new-who-study (Accessed March 24, 2023).

31. Mamo K, Siyoum M. Premature Implanon discontinuation and associated factors among Implanon user women in Ambo town, Central Ethiopia. J Health Med Nurs. (2019) 58:39–46. doi: 10.7176/jhmn/58-05

32. Mihretie GS, Abebe SM, Abebaw Y, Gedefa L, Gure T, Alemayehu BA, et al. Factors associated with discontinuation among long-acting reversible contraceptive users: a multisite prospective cohort study in urban public health facilities in Ethiopia. BMJ Open. (2022) 12. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059372

33. Kungu W, Agwanda A, Khasakhala A. Prevalence of and factors associated with contraceptive discontinuation in Kenya. Afr J Prm Health Care Fam Med. (2022) 14(1). doi: 10.1177/17455057221109222

34. Melesse YD, Zegeye AM, Kebede GD, Tarik YD, Fenta SL, Getu AA, et al. Discontinuation of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods and associated factors among women in health facilities of Bahir Dar City, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Reprod Syst Sex Disord. (2022) 11(319). doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.979231

35. Siyoum M, Mulaw Z, Abuhay M, Kebebe H. Implanon discontinuation rate and associated factors among women who ever used Implanon in the last three years in Debre Markos town, Northwest Ethiopia, 2016, cross-sectional study. ARC Journal of Public Health and Community Medicine. (2017) 2(1):8–16. doi: 10.20431/2456-0596.0201003

Keywords: discontinuation, long-acting contraceptives, contraceptive, reproductive-age women, Shashemene town

Citation: Letose F, Tusa A, Sahlu D and Miherite Y (2024) Discontinuation of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods and associated factors among reproductive-age women in Shashemene town, Oromia, Ethiopia. Front. Glob. Womens Health 5:1269302. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2024.1269302

Received: 1 August 2023; Accepted: 11 April 2024;

Published: 7 May 2024.

Edited by:

Emmanuel Senanu Morhe, University of Health and Allied Sciences, GhanaReviewed by:

Edward Dassah, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, GhanaMichael Amoh, University of Health and Allied Sciences, Ghana

© 2024 Letose, Tusa, Sahlu and Miherite. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fikru Letose ZmlrcnVsZXRvc2U2QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Fikru Letose

Fikru Letose Alemtsehay Tusa2

Alemtsehay Tusa2 Degemu Sahlu

Degemu Sahlu Yohannis Miherite

Yohannis Miherite