- 1Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 2Department of Orthopedic Surgery, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

Universal, publicly funded healthcare has long been a point of pride for Canada, despite decades of data contradicting its universality and accessibility. Inequities in access to and provision of healthcare services are particularly evident in the direct comparison of health outcomes between Indigenous (First Nations, Inuit, and Métis) and non-Indigenous populations in Canada. Globally, there are data to support similar disparities in maternal-child health for Indigenous populations around the world. Here, we describe how these inequities uniquely impact people at the intersection of multiple vulnerabilities—Indigenous pregnant women and their children. Indigenous pregnant women in Canada are far more likely to have experienced harmful in utero exposures, inadequate antenatal care, and adverse birth outcomes than non-Indigenous pregnant women. These inequities in maternal-child health may be contributing to biological processes (e.g., epigenetic reprogramming) with intergenerational consequences for chronic disease risk in Indigenous populations. We highlight how the current state of maternal-child health for Indigenous women in Canada is likely perpetuating the multigenerational cycle of oppression triggered by the process of colonization. Finally, we outline current efforts to achieve reproductive justice, decolonize maternal-child health in Canada, and reclaim childbirth by Indigenous communities and their allies. We recognize the strength and resilience of Indigenous women in Canada to resist the persistence of colonial ideals in birthing rights and practices.

Introduction

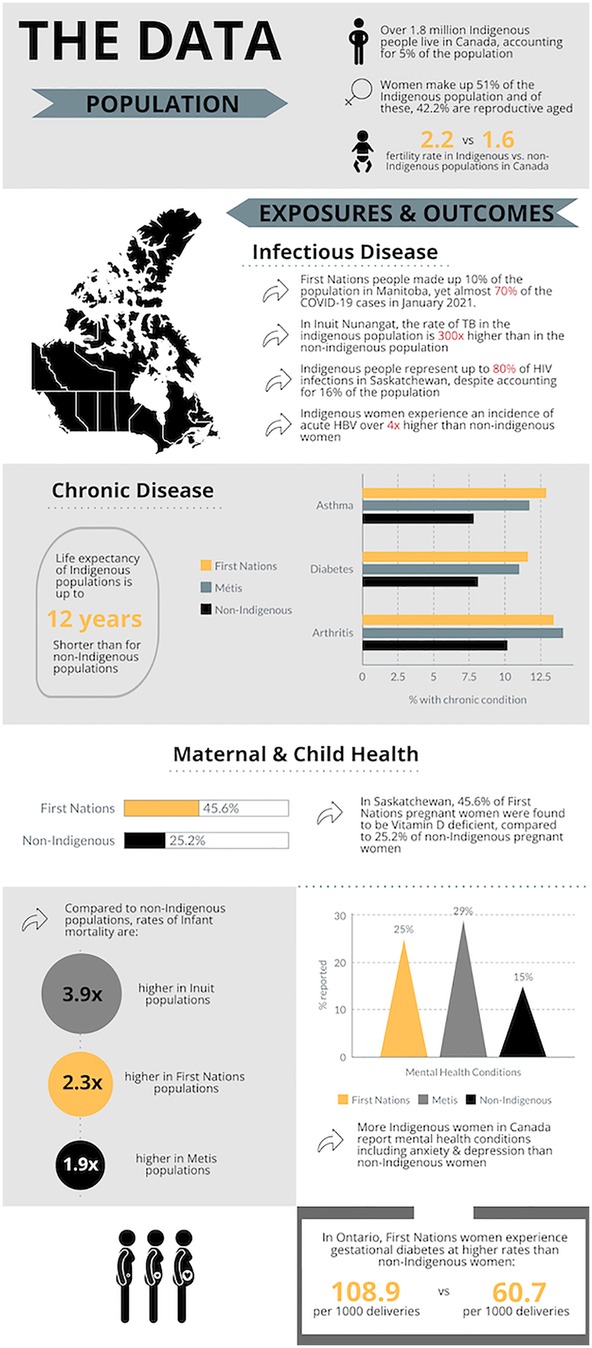

Universal, publicly funded healthcare has long been a point of pride for Canada, despite decades of data indicating its universality and accessibility as debatable, at best. The reality is that Canada's healthcare system does not and has not ever served all peoples equally. Inequities in access to and provision of healthcare services are particularly evident in the direct comparison of health outcomes between Indigenous (First Nations, Inuit, and Métis) and non-Indigenous populations in Canada. For example, within one year Indigenous populations were significantly less likely to have seen a physician and significantly more likely to have a chronic condition including arthritis, asthma, diabetes, and obesity (1). In Canada's emergency departments, Indigenous people receive lower acuity triage scores than non-Indigenous people with the same diagnoses and are more likely to leave the ED without being seen (2, 3). Moreover, the life expectancy of Indigenous peoples in Canada is up to 12 years shorter than for non-Indigenous populations (Figure 1) (4).

Figure 1. Infographic depicting demographics of the Indigenous population in Canada and exposures and outcomes disproportionately experienced by indigenous populations in Canada, including infectious disease, chronic disease, and maternal-child and women's health. Data Sources: (4, 45–48). Figure created using Piktochart.

The overall health of a population can be measured by the health of its most vulnerable—pregnant women and children. In Canada, Indigenous pregnant women experience higher rates of maternal mortality and, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), Indigenous children are two to four times less likely to survive infancy than non-Indigenous children (4). Cause-specific contributors to infant mortality include elevated rates of infection, congenital abnormalities, and conditions related to prematurity in Indigenous infants (5). Most starkly, rates of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) are seven times higher (2.0 vs. 0.3 per 1,000 livebirths) for Indigenous infants than non-Indigenous infants (5). Rates of maternal-fetal morbidity are similarly elevated—Indigenous mothers and babies are more likely to have experienced harmful in utero exposures (Box 1) (6), reduced access to reproductive age and antenatal healthcare (6, 7), and/or adverse birth outcomes (i.e., preterm birth and large-for-gestational age in Inuit and First Nations communities, respectively) (5) with lifelong consequences for health and development. Contributors to and consequences of these disparities in Indigenous maternal-fetal health are explored below.

Box 1. Key definitions, key points, and key resources relevant to this manuscript and Indigenous perinatal health in Canada are outlined here.

It is worth noting that this problem is not unique to Canada. Globally, Indigenous women experience higher rates of maternal morbidity and mortality, receive less antenatal care, and have worse birth outcomes (8–12). In the US, Indigenous women are almost twice as likely to experience severe maternal morbidity or mortality than white women (8). Indigenous mothers in Australia have a maternal mortality incidence more than three times that of non-Indigenous mothers (9). In Namibia, 33% of Indigenous women did not receive antenatal care and 62% had no skilled attendants at delivery, compared to 3% and 11%, nationally (11). In Australia, New Zealand, US, and Canada, the Indigenous to non-Indigenous infant mortality rate ratios are universally elevated, ranging from 1.6 to 4.0 (10). While global Indigenous populations are, of course, highly heterogeneous, many share common experiences of colonization, environmental and land dispossession, and ongoing systemic racism that contribute to worse maternal-child health (12). Neither is this problem unique to Indigenous populations—disparities in access to and outcomes of maternal-child health similarly affect Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations at the intersection of multiple forms of marginalization and oppression (e.g., race/ethnicity, language, newcomer status, education level, rurality, incarceration, socioeconomic status, gender, sex, and sexuality, etc.) (13).

In Canada, the intergenerational effects of complex trauma on Indigenous population health, in the context of residential schools and ongoing colonialist policies, have been well-documented (14, 15). However, the potential for compounding intergenerational, epigenetic effects of adverse in utero exposures and birth outcomes on Indigenous population health have not been emphasized. Here, we emphasize this potential and outline important efforts to break the cycle and achieve reproductive justice for Indigenous populations in Canada.

The link between prenatal health and lifelong health

An immense body of research supports the developmental origins of disease, whereby a child's prenatal and early life exposures directly impact their lifelong health trajectory (16). Many maternal-fetal exposures during pregnancy (e.g., stress, malnutrition, infection) have been associated with long-term cardiovascular, metabolic, immune, and neuropsychiatric morbidities for mother and child, emphasizing the need for comprehensive prenatal care and maternal disease prevention (Box 1) (16). Furthermore, harmful in utero exposures and adverse birth outcomes (e.g., preterm birth) have been shown to induce epigenetic reprogramming and shifted risk profiles in the developing baby with lasting, multigenerational consequences for neurodevelopment and chronic disease (17, 18). For example, a child born preterm is at higher risk for hypertension, cardiovascular, and renal disease later in life. Moreover, female children born preterm are at increased risk for preterm delivery of their own children, creating an intergenerational cycle that perpetuates and amplifies the sequelae of preterm birth (18). There is also clinical and preclinical evidence for the transgenerational transmission of metabolic (e.g., elevated adiposity, impaired glucose regulation, BMI) and behavioural traits (e.g., stress hyperreactivity, depressive behaviours) due to parental malnutrition, infection, stress, and toxin exposures (17). Similarly, the intergenerational transmission of complex trauma is hypothesized to have a physiological basis in epigenetic programming (15).

In Canada, all the maternal exposures and birth outcomes, as well as the long-term chronic diseases described above are disproportionately prevalent amongst Indigenous populations (Figure 1) (1). Indigenous women in Canada are more likely than non-Indigenous women to have gestational diabetes and nutritional deficiencies during pregnancy for multifactorial reasons including higher rates of pre-gestational diabetes, lack of culturally appropriate health and nutrition counselling, and food insecurity secondary to social, economic, and geographical inequities (6). Rates of acute and chronic infections including COVID-19, HIV, Hepatitis A and B, HPV, Chlamydia trachomatis, and tuberculosis, are higher in Indigenous populations than non-Indigenous populations across Canada (19). This is especially true for more isolated Indigenous communities in the prairies and Northern communities, where multiple socioeconomic determinants of health (e.g., underlying medical conditions, crowded housing, poverty, poor access to healthcare and treatment) intersect to underlie higher infection rates and worse outcomes (19). Resource extraction economies in many Indigenous lands are linked to higher rates of environmental toxin exposure [e.g., mercury, polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB), uranium, pesticides] and gender-based violence during pregnancy (6, 20). Elevated rates of stress, anxiety, and depression reported by Indigenous women during pregnancy are compounded by colonialist maternal health policies including legislatively enforced evacuation from their rural communities to deliver at faraway urban hospitals (6). The residential school and reservation systems created a cycle of economic isolation and reduced employment opportunities for Indigenous peoples, leading to higher unemployment rates, wage gaps, and lower socioeconomic status—well-established social determinants of health and pregnancy outcomes (1, 21). High rates of poor housing conditions and overcrowded households contribute to an increased risk for preterm birth amongst Indigenous peoples (22). The intersectional effects of high-risk determinants of substance use (i.e., history of sexual abuse and/or intergenerational trauma, childhood separation, low socioeconomic status, unstable housing, reproductive injustice, etc.) have also put Indigenous women at disproportionate risk for perinatal substance use (23).

Collectively, these data indicate the possibility for convergence of complex trauma and harmful in utero exposures on epigenetic pathways in Indigenous communities, with long-term population health consequences. As such, widespread disparities in maternal-child health faced by Indigenous communities in Canada may be exacerbating the health impacts caused by multigenerational cycles of oppression, trauma, and intersectional marginalization brought on by colonization.

Antenatal and postnatal care

Reproductive and antenatal healthcare are critical for preventing or mitigating in utero exposures and adverse pregnancy outcomes that have intergenerational impacts (16) and Indigenous women access and/or receive reproductive age and antenatal care at lower rates than non-Indigenous women (7). For example, a large population-based study in Canada showed that despite reporting worse health and more chronic diagnoses, 40.7% fewer Inuit women of child-bearing age had access to a regular health care provider and 21.5% more First Nations women of child-bearing age reported unmet mental healthcare needs, relative to non-Indigenous women (7). Amongst pregnant women or new mothers, PHAC reports that 71% of Indigenous vs. 89% of non-Indigenous women have a regular healthcare provider (24).

These disparities are due to a myriad of factors including geographic and economic barriers; the colonization of childbirth and a lack of culturally appropriate care (e.g., the Indian Act, legislative outlawing of Indigenous midwives, dismissal of Indigenous knowledge and agency surrounding maternity and childbirth, Health Canada enforced evacuation); and extraordinary levels of anti-Indigenous racism/stigmatization in the reproductive healthcare system including forced or coercive sterilization and child apprehension (6, 7, 25–27). Canada's long history of child apprehension—residential schools through to the Sixties Scoop and present-day overrepresentation of Indigenous children in child welfare systems—has had direct effects on maternal health, reducing access to antenatal care for subsequent pregnancies in women with a history of child apprehension (26). Beyond the antenatal period, the labor/delivery and neonatal periods including emergency obstetric care, attendance of a skilled provider, and postnatal care are also critical to optimize outcomes. Within the last few years, Pearl Gambler, Sarah Morrison, and Kristy White are three Indigenous women who have made Canadian headlines for speaking out about their abhorrent experiences within the Canadian maternal-child healthcare system (28–30). Each of these women reported mistreatment, neglect, and outright racism during childbirth, ending in the death or injury of their babies.

Indigenous women in Canada face inequities all along the continuum of reproductive care. Here, we have outlined how the repercussions of this do not stop at a single generation. Increasing evidence that perinatal health has lasting, intergenerational impacts for population health suggests that inequities in Canadian maternal-child healthcare are perpetuating the cycle of intergenerational oppression linked to colonization, land dispossession, intersectional marginalization, and systemic anti-Indigenous racism.

Discussion: where to go from here

The way forward must centre Indigenous voices and perspectives. Several systematic reviews have highlighted the perspectives of Indigenous women on general and perinatal health inequities in Canada, citing service availability, negative experiences with healthcare providers (i.e., racism, discrimination, marginalization), the negative impact of systemic social determinants of health including justice, education, and socioeconomic status, and the impact of deep-rooted colonial ideologies and practices (i.e., medical evacuation) as self-identified factors impacting the health and wellbeing of Indigenous women (31, 32). Steps to achieving reproductive justice and equity that have been suggested by Indigenous researchers, activists, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada include implementation of Indigenous community-led models of care, Indigenous representation in research and at decision-making tables, increased representation of Indigenous populations within the healthcare workforce (i.e., midwives, nurses, physicians, etc.), and a systemic shift in healthcare policy, education, and practice to cultural safety, respect for Indigenous knowledge and agency, anti-racism, trauma-informed care, and self-determination for Indigenous peoples (1, 6, 26, 33, 34).

Over the past decade, there has been persistent progress by Indigenous activists and allies in highlighting and addressing the inequities in Indigenous maternal health, mirrored by increasing support and momentum for the reclamation of childbirth by Indigenous communities. These efforts are grounded at the individual level, with increasing empowerment of Indigenous patient and provider voices and leadership in research and programming to inform self-determined strategies and interventions (32, 35–37). At the societal and infrastructural level, we have seen the growth and development of long-standing, sustainable models of Indigenous-owned maternal-child care (e.g., Inuulitsivik midwifery service and education program, Tsi Non:we Ionnakeratstha/Ona:grahsta' Maternal and Child Health Center on the Six Nations of the Grand River Territory) (38, 39); expansion of University- and community-based Indigenous midwifery training programs and resurgence of Indigenous doula training (35, 40, 41); the establishment of nationally recognized Indigenous-led societies (i.e., National Council of Indigenous Midwives); and the adoption of dedicated Indigenous maternal health initiatives by professional associations like the Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Canada (SOGC). These efforts have translated into increasing pressure for reform at the government and policy level, which has seen positive steps forward including legislative reforms to the Ontario Midwifery Act, federal Bill C-92 returning jurisdiction over child and family services to Indigenous communities, and the allocation of provincial and federal funding to support Indigenous midwifery training and birthing centers.

Despite this progress, the equity gap has not been closed (33). As outlined above, the data that exist to quantify in utero exposures, access to reproductive and antenatal care, and birth outcomes in Indigenous vs. non-Indigenous, Canadian-born populations suggest that there is work yet to be done. There are strong, evidence-based and scalable models for Indigenous-led community programs that work to improve maternal-child health and there are a plethora of frameworks and calls to action that clearly outline solution-oriented steps required to continue moving forward (33, 36, 38, 39, 42). The foundations for a more equitable system have been laid and it is our responsibility to continue building on them.

It is far past time to prioritize the decolonization of Indigenous maternal-child health. Canada's universal healthcare system is not universal, but it can become more equitable with cultural humility and institutional and policy reform informed by those who are affected. We are a new generation of healthcare practitioners who have been exposed and educated more than any generation before us to the realities of healthcare for Indigenous peoples in Canada. We know better and so we must do better.

Positionality

AMW is a white woman who lives and studies on the traditional territories of the Mississauga and Haudenosaunee nations, and within the lands protected by the “Dish with One Spoon” wampum agreement. She holds a PhD in global maternal-child health from the University of Toronto and is currently a medical student at McMaster University. This publication was a collaborative effort, guided by the insight and teachings of PF, as part of a self-reflective journey in the context of an elective course on Indigenous Health in Canada. It reflects her commitment to addressing maternal health disparities in under-served communities and advocating for culturally competent, equitable healthcare.

PF is an Annishinaabe Scholar from Saugeen-Ojibway territory in Ontario. As the Chair of Indigenous Health for McMaster Undergraduate Medical School Program, she provides education, teaching, and opportunities for all students at McMaster in Indigenous Ways of Knowing, to work towards cultural humility.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Garner R, Carrière G, Sanmartin C, Longitudinal Health and Administrative Data Research Team. The Health of First Nations Living Off-Reserve, Inuit, and Métis Adults in Canada: The Impact of Socio-economic Status on Inequalities in Health. Ottawa: Statistics Canada (2010). (Health Research Working Paper Series).

2. McLane P, Bill L, Healy B, Barnabe C, Plume TB, Bird A, et al. Leaving emergency departments without completing treatment among first nations and non-first nations patients in Alberta: a mixed-methods study. Can Med Assoc J. (2024) 196(15):E510–23. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.231019

3. McLane P, Barnabe C, Mackey L, Bill L, Rittenbach K, Holroyd BR, et al. First nations status and emergency department triage scores in Alberta: a retrospective cohort study. Can Med Assoc J. (2022) 194(2):E37–45. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.210779

4. Public Health Agency of Canada. Key Health Inequalities in Canada: A National Portrait. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada (2018).

5. Sheppard AJ, Shapiro GD, Bushnik T, Wilkins R, Perry S, Kaufman JS, et al. Birth outcomes among first nations, inuit and métis populations. Health Rep. (2017) 28(11):11–6.29140536

6. Bacciaglia M, Neufeld HT, Neiterman E, Krishnan A, Johnston S, Wright K. Indigenous maternal health and health services within Canada: a scoping review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2023) 23(1). doi: 10.1186/s12884-023-05645-y

7. Srugo SA, Ricci C, Leason J, Jiang Y, Luo W, Nelson C. Disparities in primary and emergency health care among “off-reserve” indigenous females compared with non-indigenous females aged 15–55 years in Canada. Can Med Assoc J. (2023) 195(33):E1097–111. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.221407

8. Kozhimannil KB, Interrante JD, Tofte AN, Admon LK, Kozhimannil KB. Severe maternal morbidity and mortality among indigenous women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. (2020) 135(2):294. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003647

9. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Maternal Deaths in Australia: 2015–2017. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2020). Vol. Cat. no. PER 106. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/maternal-deaths-in-australia-2015-2017/summary?utm_source=chatgpt.com (Accessed April 1, 2025).

10. Smylie J, Crengle S, Freemantle J, Taualii M. Indigenous birth outcomes in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States—an overview. Open Womens Health J. (2010) (4):7. doi: 10.2174/1874291201004020007

11. UNFPA. Indigenous Women’s Maternal Health and Maternal Mortality. (2016). Available at: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/factsheet_digital_Apr15.pdf (Accessed April 1, 2025).

12. Patterson K, Sargeant J, Yang S, McGuire-Adams T, Berrang-Ford L, Lwasa S, et al. Are indigenous research principles incorporated into maternal health research? A scoping review of the global literature. Soc Sci Med. (2022) 292, doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114629

13. Bohren MA, Iyer A, Barros AJD, Williams CR, Hazfiarini A, Arroyave L, et al. Towards a better tomorrow: addressing intersectional gender power relations to eradicate inequities in maternal health. EClinicalMedicine. (2023) 67:102180. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102180

14. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Canada’s Residential Schools: The Legacy. Winnipeg: McGill-Queen's University Press (2015). Available at: https://nctr.ca/records/reports/ (Accessed January 28, 2024).

15. O’Neill L, Fraser T, Kitchenham A, McDonald V. Hidden burdens: a review of intergenerational, historical and complex trauma, implications for indigenous families. J Child Adolesc Trauma. (2016) 11(2):173–86. doi: 10.1007/s40653-016-0117-9

16. McDonald CR, Weckman AM, Wright JK, Conroy AL, Kain KC. Developmental origins of disease highlight the immediate need for expanded access to comprehensive prenatal care. Front Public Health. (2022) 10, doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1021901

17. Bale TL. Epigenetic and transgenerational reprogramming of brain development. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2015) 16(6):332–44. doi: 10.1038/nrn3818

18. Luyckx VA. Preterm birth and its impact on renal health. Semin Nephrol. (2017) 37(4):311–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2017.05.002

19. Lee NR, King A, Vigil D, Mullaney D, Sanderson PR, Ametepee T, et al. Infectious diseases in indigenous populations in North America: learning from the past to create a more equitable future. Lancet Infect Dis. (2023) 23(10):e431–44. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00190-1

20. Jubinville D, Smylie J, Wolfe S, Bourgeois C, Berry NS, Rotondi M, et al. Relationships to land as a determinant of wellness for indigenous women, two-spirit, trans, and gender diverse people of reproductive age in Toronto, Canada. Can J Public Health. (2022) 115(Suppl 2):253–62. doi: 10.17269/s41997-022-00678-w

21. Kim PJ. Social determinants of health inequities in indigenous Canadians through a life course approach to colonialism and the residential school system. Health Equity. (2019) 3(1):378–81. doi: 10.1089/heq.2019.0041

22. Shapiro GD, Sheppard AJ, Mashford-Pringle A, Bushnik T, Kramer MS, Kaufman JS, et al. Housing conditions and adverse birth outcomes among indigenous people in Canada. Can J Public Health. (2021) 112(5):903–11. doi: 10.17269/s41997-021-00527-2

23. Shahram SZ, Bottorff JL, Oelke ND, Dahlgren L, Thomas V, Spittal PM. The cedar project: using indigenous-specific determinants of health to predict substance use among young pregnant-involved indigenous women in Canada. BMC Womens Health. (2017) 17(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0437-4

24. Public Health Agency of Canada. Healthcare for Indigenous women: A story of struggles to positive strides. (2024). Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/aboriginal-health/healthcare-indigenous-women.html (Accessed April 1, 2025).

25. Jasen P. Race, culture, and the colonization of childbirth in northern Canada. Soc Hist Med. (1997) 10(3):383–400. doi: 10.1093/shm/10.3.383

26. Smylie J, Phillips-Beck W. Truth, respect and recognition: addressing barriers to indigenous maternity care. CMAJ. (2019) 191(8):E207–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.190183

27. Government of Canada. 1876 Indian Act (1876). Available at: https://nctr.ca/records/reports/#legislation (Accessed May 27, 2025).

28. Orr D, Chaudhary K, Troian M. Analysis of anti-indigenous racism in hospitals reveals pattern of harm, no tracking mechanism. Canada's National Observer. (2023). Available at: https://www.nationalobserver.com/2023/04/11/investigations/anti-indigenous-racism-health-care (Accessed January 28, 2024).

29. Gomez M. Actions of racist nurse during childbirth contributed to son’s brain injuries, nisga’a woman says. CBC. (2021). Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/nisga-a-woman-childbirth-brain-injuries-1.6083784 (Accessed January 28, 2024).

30. The Canadian Press. Family of indigenous woman who says she was turned away from B.C. Hospital want review made public. The Globe and Mail. (2021). Available at: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/british-columbia/article-family-of-indigenous-woman-who-says-she-was-turned-away-from-bc (Accessed January 28, 2024).

31. Fournier C, Lafrenaye-Dugas AJ. Social inequalities in health: The perspective of Indigenous girls and women. (2024). Available at: http://www.inspq.qc.ca (Accessed April 1, 2025).

32. Sharma S, Kolahdooz F, Launier K, Nader F, June Yi K, Baker P, et al. Canadian Indigenous womens perspectives of maternal health and health care services: a systematic review. Divers Equal Health Care. (2016) 13(5). doi: 10.21767/2049-5471.100073

33. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. Winnipeg: McGill-Queen's University Press (2015). Available at: https://nctr.ca/records/reports/ (Accessed January 28, 2024).

34. Perinatal Services BC. Honouring Indigenous Women’s and Families’ Pregnancy Journeys: A Practice Resource to Support Improved Perinatal Care Created by Aunties, Mothers, Grandmothers, Sisters, and Daughters. Vancouver: Perinatal Services BC (2021).

35. Doenmez CFT, Cidro J, Sinclair S, Hayward A, Wodtke L, Nychuk A. Heart work: indigenous doulas responding to challenges of western systems and revitalizing indigenous birthing care in Canada. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2022) 22(1). doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-04333-z

36. Smylie J, Kirst M, McShane K, Firestone M, Wolfe S, O’Campo P. Understanding the role of indigenous community participation in indigenous prenatal and infant-toddler health promotion programs in Canada: a realist review. Soc Sci Med. (2016) 150:128–43. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.12.019

37. Churchill ME, Smylie JK, Wolfe SH, Bourgeois C, Moeller H, Firestone M. Conceptualising cultural safety at an indigenous-focused midwifery practice in Toronto, Canada: qualitative interviews with indigenous and non-indigenous clients. BMJ Open. (2020) 10(9):e038168. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038168

38. Van Wagner V, Epoo B, Nastapoka J, Harney E. Reclaiming birth, health, and community: midwifery in the inuit villages of nunavik, Canada. J Midwifery Womens Health. (2007) 52(4):384–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.03.025

39. Six Nations Health Services. Six Nations Health Services. Tsi Nón:we Ionnakerátstha (Birthing Centre). Available at: https://www.snhs.ca/child-youth-health/birthing-centre/ (Accessed January 28, 2024).

40. Lalonde AB, Butt C, Bucio A. Maternal health in Canadian aboriginal communities: challenges and opportunities. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. (2009) 31(10):956–62. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34325-0

41. National Council of Indigenous Midwives. National Council of Indigenous Midwives. Indigenous Midwifery Education. Available at: https://indigenousmidwifery.ca/become-a-midwife/ (Accessed January 28, 2024).

42. Hickey S, Roe Y, Ireland S, Kildea S, Haora P, Gao Y, et al. A call for action that cannot go to voicResearch activism to urgently improve indigenous perinatal health and wellbeing. Women Birth. (2021) 34(4):303–5. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.03.011

43. Lo JO, D’Mello RJ, Watch L, Schust DJ, Murphy SK. An epigenetic synopsis of parental substance use. Epigenomics. (2023) 15(7):453–73. doi: 10.2217/epi-2023-0064

44. Hoover E, Cook K, Plain R, Sanchez K, Waghiyi V, Miller P, et al. Indigenous peoples of North America: environmental exposures and reproductive justice. Environ Health Perspect. (2012) 120(12):1645–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205422

45. Public Health Agency of Canada. Indigenous population continues to grow and is much younger than the non-Indigenous population, although the pace of growth has slowed. (2022). Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220921/dq220921a-eng.htm (Accessed April 1, 2025).

46. Public Health Agency of Canada. Unmet health care needs during the pandemic and resulting impacts among First Nations people living off reserve, Métis and Inuit. (2022). Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2022001/article/00008-eng.htm (Accessed April 1, 2025).

47. Lehotay DC, Smith P, Krahn J, Etter M, Eichhorst J. Vitamin D levels and relative insufficiency in Saskatchewan. Clin Biochem. (2013) 46(15):1489–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2013.05.051

Keywords: indigenous, maternal-child health, decolonization, reproductive justice, intergenerational

Citation: Weckman AM and Farrugia P (2025) Inequities in Canadian maternal-child healthcare are perpetuating the intergenerational effects of colonization for indigenous women and children. Front. Glob. Women's Health 6:1513145. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2025.1513145

Received: 17 October 2024; Accepted: 20 May 2025;

Published: 4 June 2025.

Edited by:

Stephen Kennedy, University of Oxford, United KingdomReviewed by:

Esteban Ortiz-Prado, University of the Americas, EcuadorJorge Vasconez-Gonzalez, University of the Americas, Ecuador

Copyright: © 2025 Weckman and Farrugia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrea M. Weckman, YW5kcmVhLndlY2ttYW5AbWVkcG9ydGFsLmNh

Andrea M. Weckman

Andrea M. Weckman Patricia Farrugia

Patricia Farrugia