- 1School of Nursing and Midwifery, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia

- 2Center for Innovative Drug Development and Therapeutic Trials for Africa (CDT-Africa), College of Health Science, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

- 3School of Medical Laboratory Science, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia

- 4School of Nursing, College of Medicine and Health Science, Arba Minch University, Arba Minch, Ethiopia

- 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden, Netherlands

Background: Maternal mortality has remained a major public health issue globally. Although there has been substantial reduction in maternal mortality, Ethiopia is still one of the highest burden countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Person-centered maternity care plays a key role in ending preventable maternal mortality. Nevertheless, little is known about the status of person-centered maternity care during facility-based childbirth in eastern Ethiopia. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the status of person-centered maternity care and its associated factors during childbirth at selected public hospitals in eastern Ethiopia.

Methods: We had conducted a facility-based cross-sectional study at selected public hospitals in eastern Ethiopia from May 16 to June 17, 2022. A total of 420 postpartum women, selected by a systematic random sampling technique, were included in the study. We had collected our data by face-to-face interview using a pretested structured questionnaire. Then, the data were entered into EpiData 4.6 and exported to SPSS version 26 for cleaning and analysis. We applied linear regression analyses to determine the associations between dependent and independent variables. The association was reported using a β coefficient with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and a p-value ≤0.05.

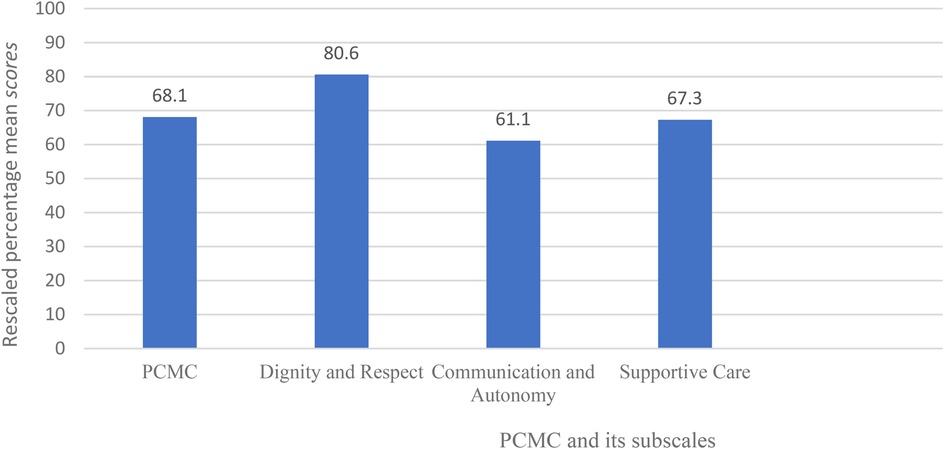

Results: The percentage mean score of person-centered maternity care was 68.1 (CI: 59.94, 62.66), SD (±14.1). From the subscales of person-centered maternity care, the percentage mean score of dignity and respect was 80.6%, communication and autonomy 61.1%, and 67.3% for supportive care. Women who'd had antenatal care (ANC) follow-up (β = 5.66, 95% CI: 2.79, 8.53) and women who gave birth to a live newborn (β = 7.59, 95% CI: 3.97, 11.20) had a positive association with person-centered maternity care. However, women who had experienced childbirth complications (β = −7.01, 95% CI: −9.88, −4.13) and those who had a hospital stay of more than two days (β = −4.08, 95% CI: −6.79, −1.38) were negatively associated with person-centered maternity care.

Conclusion: Our study revealed that the mean person-centered maternity care score of the participants was significantly higher than in previous studies. Women who had antenatal care follow-up, experienced complications during childbirth, gave birth to a live newborn, and had a hospital stay of more than two days were significantly associated with person-centered maternity care. Therefore, we strongly concluded that strengthening antenatal care utilization and early detection and appropriate management of childbirth and pregnancy complications would greatly improve person-centered maternity care.

Introduction

Despite a 38% reduction in the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) between 2000 and 2017, maternal deaths remained a global public health challenge (1). Every day in 2020, about 800 women had died from preventable causes, with 94% of these deaths having occurred in low and middle-income countries (2). In Ethiopia, although maternal mortality has been reduced by half since 2000, it is still estimated to be 412 deaths per 100,000 live births (3). Maternal deaths in Ethiopia have been attributed to preventable causes such as postpartum complications, home delivery, and abortion, among others (1). Poor quality of care is a major factor in maternal deaths and is a significant barrier for women who seek healthcare services. Person-centered maternity care is one aspect of quality care that needs to be addressed.

Person-centered care is when a person can be the driving force of their own healthcare decisions and receive healthcare that is tailored to their own values and preferences. It is a fundamental concept that guides the setting of care philosophy from a traditional biomedical model to a more humanistic approach (2). It is considered a gold standard dimension of quality care and a major theme in modern healthcare systems (3).

Person-centered maternity care (PCMC) is providing respectful and responsive care that is specifically tailored to an individual woman's preferences, values, and needs during childbirth (4). The World Health Organization has fully recognized PCMC as a key component of quality maternity care (5). Dignity and respect, communication and autonomy, and supportive care are identified as fundamental components of PCMC (5).

PCMC prioritizes the quality of a woman's birth experience by encouraging her to feel free, safe, and confident enough to express her feelings and needs to the healthcare provider (6). It is a strong health promotion approach that increases women's satisfaction, decreases anxiety, and improves healthcare utilization (7). According to existing evidence, there is a significant association between PCMC and women's positive childbirth experiences (8). PCMC has been associated with lower neonatal complications and a higher willingness of women to return to the health institution for their future childbirth (9, 10). Due to the evidence presented above, it is quite clear that PCMC is crucial for the improvement of both maternal and neonatal health. As a result, global movements have called for greater emphasis on PCMC (11).

Every woman deserves self-centered, dignified, and respectful maternal care during childbirth (12). However, thousands of women are facing various forms of mistreatments during childbirth in many parts of the world (13). According to a study conducted in East and Southern Africa, many women had poor interactions with providers, noting that the procedures or care they received were not adequately explained to them. Additionally, both physical and verbal abuses were also reported by the participants (14).

Poor quality care during childbirth significantly contributes to maternal deaths. The lack of PCMC has been associated with maternal complications such as obstructed labor and postpartum hemorrhage (15). When maternity care is not centered on the needs and preferences of the woman and she feels unheard, she may be less likely to report concerning symptoms or ask questions about her care. This lack of open dialogue can hinder the provider's ability to monitor and respond promptly to emerging complications including, obstructed labor, postpartum hemorrhage, birth canal lacerations, increased risk of cesarean section, and fetal distress (15–17). Therefore, PCMC plays a critical role in decreasing both maternal morbidity and mortality (6). It is also a significant strategy for achieving the Sustainable Development Goal of reducing maternal mortality to less than 70 deaths per 100,000 live births (18).

Furthermore, studies conducted in Ethiopia had revealed that two-thirds of women reported their healthcare providers had never introduced themselves and that they gave birth without a birth companion (19). Additionally, 34.5% of women had often been slapped by their healthcare provider during delivery (20). Nevertheless, there is limited research evidence regarding the status of PCMC in eastern Ethiopia, so the aim of this study was to assess the status of person-centered maternity care and its associated factors during childbirth at selected public hospitals in eastern Ethiopia.

Materials and methods

Study setting and design

We conducted a facility-based cross-sectional study from May 16 to June 17, 2022, at purposively selected three public hospitals in eastern Ethiopia, namely: Hiwot Fana Comprehensive Specialized University Hospital (HFCSUH), Haramaya General Hospital (HGH), and Dil Chora Referral Hospital (DCRH). HFSCUH is a comprehensive teaching hospital affiliated with Haramaya University College of Health and Medical Sciences, which is located in Harar town at a distance of 526 km to the east of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. It serves around 5.8 million people of the surrounding population (21). The Haramaya General Hospital is located in Haramaya town, at a distance of 507 km to the east of Addis Ababa. It serves about 1,143,909 Haramaya district residents and the neighboring population. DCRH is located in the Dire Dawa administration in eastern Ethiopia, located 515 km away from Addis Ababa and it annually serves around 193,485 people from nearby populations (1).

Study population

Women who gave birth at the selected public hospitals and were within the six-week postpartum period were eligible to participate in this study. However, we excluded those who were unable to provide information due to severe physical or mental health conditions.

Sample size determination

Since there had been no previous similar study that had used double population mean formula, the sample size was calculated by an online sample size calculator (https://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm). So, it was calculated using a double population mean formula with a (95%) confidence level, (2%) margin of error, (80%), power, (β = 4.69, 95% CI: 2.63, 6.76) confidence interval from a previous study (22), and an average of 1,190 women who gave birth each month in the selected public hospitals as a source population. Then 10% of the calculated sample size was added to account for potential non-responses. And the final calculated sample size was 420.

Sampling technique and procedure

We had proportionally allocated the calculated sample size (420) to each of the three selected hospitals based on their estimated number of monthly deliveries. The study participants were selected by a systematic random sampling technique. The sampling interval (k value) was calculated by dividing the total number of estimated monthly delivery reports by the required sample size, which is 1,190/420 ≈ 3. Finally, every third woman was recruited using her respective delivery registration number, and the first participant was selected by the lottery method.

Data collection tool

The data collection tool was adapted by reviewing different literature (19, 22–24). This tool comprised sociodemographic characteristics, obstetrical factors, facility-related factors, and PCMC experiences of the participants. The data on PCMC items were collected using a validated person-centered maternity care scale adopted from previous studies (19, 22–24). The study participants' obstetrical data were extracted from the participants' medical records. The questionnaire was prepared first in English language and translated into local languages (Afan Oromo, Amharic, and Af-Somali) and back into English language by different language experts to ensure consistency.

Data collection procedure

Six BSc Midwives, who do not work in the study area, collected the data under the supervision of the principal investigator and four MSc Midwives. They conducted interviewer-administered face-to-face exit interviews in the postnatal unit, using each participant's respective medical record.

Data quality control

The questionnaire was pretested on 5% of the total sample size outside the study area to identify any ambiguity, check for consistency and acceptability, as well as to make necessary corrections before the actual data collection period. The questionnaire had a Cronbach's alpha of 0.89, indicating good internal reliability. Data collectors and supervisors were trained for one day by the principal investigator regarding the objectives of the study, data collection procedures, and the maintenance of confidentiality. The data were checked daily for completeness and consistency and, corrective measures were taken in a timely manner.

Study variables

Person-centered maternity care (PCMC), which is composed of three domains, namely dignity and respect, communication and autonomy, and supportive care, was the outcome variable. Furthermore, sociodemographic characteristics (age, religion, marital status, residence, educational status, employment status, and average monthly family income), obstetrical factors (parity, ANC, number of institutional deliveries, mode of delivery, time of delivery, childbirth complications, and newborn outcome), and facility-related factors (sex of the main birth attendant and length of hospital stay) were the independent variables of this study.

Measurements of outcome

PCMC is measured by the PCMC scale. The PCMC scale is a validated scale that comprises three domains (i.e., dignity and respect, communication and autonomy, and supportive care) (23, 24). There are a total of 30 items with each item having four-response options: i.e., 0- no, never, 1- yes, a few times, 2- yes, most of the time, and 3- yes, all the time. Negative items such as verbal abuse, physical abuse, and crowdedness were reversely coded to reflect a scale of 0 as the lowest level and 3 as the highest level. The total PCMC score is a summative score from the responses to the individual items, which ranges from 0 to 90 (19, 24). To enable easy comparison across the PCMC domains, the scores were rescaled and standardized to range from 0 to 100. Furthermore, verbal abuse is when a woman feels that the health providers shouted, scolded, insulted, threatened, or have spoken to her rudely. Physical abuse is when a woman feels that she is being treated roughly, such as being pushed, beaten, slapped, pinched, or physically restrained (24).

Data management and analysis

Our data was entered into EpiData version 4.6 software and then exported to SPSS version 26 for further cleaning, coding, and analysis. Descriptive statistics was carried out to compute frequencies, proportions, means, and standard deviations. The normality assumption was assessed using a P-P plot and histogram. Linearity was checked using a scatter plot, and multicollinearity was checked using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). After creating dummy variables, simple and multiple linear regression analyses was used to determine the factors associated with PCMC. Those variables with p-value ≤0.25 in the simple linear regression were qualified to the final model. Unstandardized β coefficient, along with a 95% CI was used to report the strength of association and statistical significance was declared at a P-value of <0.05.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

Out of a total of 420 expected respondents, 412 provided complete responses, resulting in a response rate of 98.1%. More than half 242 (58.7%) of the study participants were from urban residences. The participants were in the age range of 16–42 years with a mean age of 25.83(±5.7) years. Nearly half 195 (47.3%) of these study participants had attended formal education (Table 1).

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the women who gave birth at selected public hospitals in eastern Ethiopia, 2022 (n = 412).

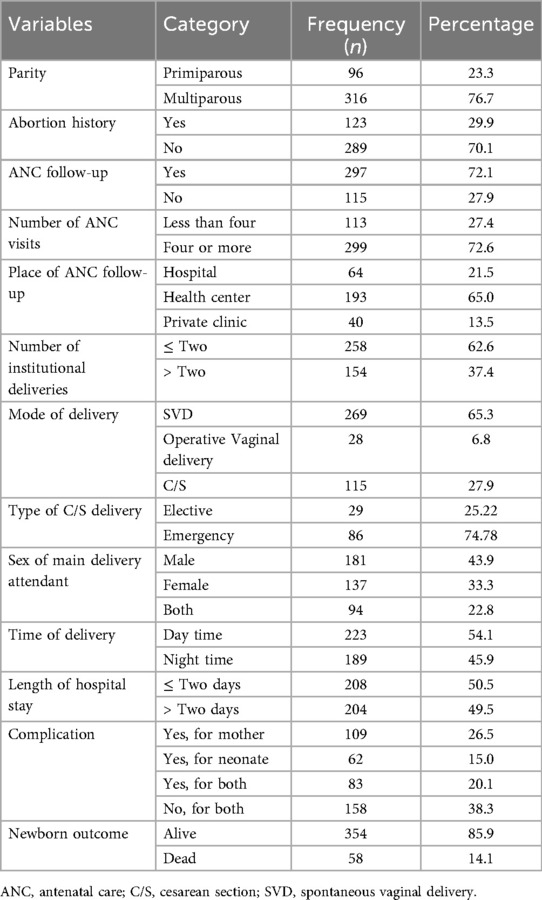

The obstetrics characteristics of the study participants

Above three-fourths 316 (76.7%) of the participants were multiparous. The average parity of the participants was three. More than a quarter 123 (29.9%) of them had a history of abortion. There were 297 (72.1%) vaginal deliveries among the 412 participants. Of these, 65.3% were spontaneous vaginal deliveries, and 6.8% were assisted by operative vaginal delivery methods. Almost six-in-ten 254 (61.7%) of the overall participants had faced childbirth complications (Table 2).

Table 2. Obstetric characteristics of the women who gave birth at selected public hospitals in eastern Ethiopia, 2022 (n = 412).

Person-centered maternity care scale and subscales

The participants mean percentage score of PCMC was 68.1 (CI: 59.94, 62.66) with a standard deviation of ±14.1. From the subscales, the rescaled mean score of dignity and respect was 80.6%, communication and autonomy 61.1%, and 67.3% for supportive care (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Rescaled percentage mean scores of person-centered maternity care and its subscales of women who gave birth at selected public hospitals in eastern Ethiopia, 2022 (n = 412).

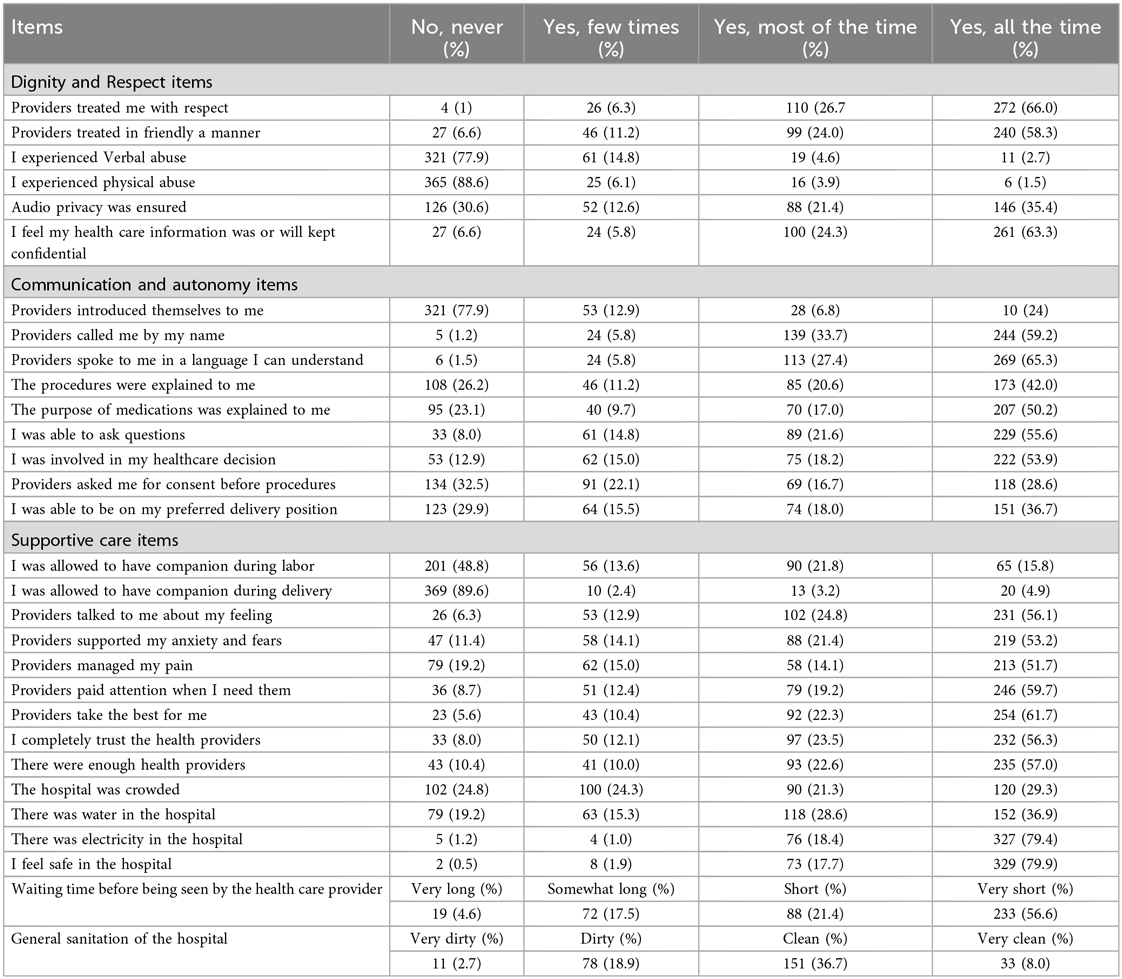

Dignity and respect

The percentage mean score of the study participants was 80.6 (±2.4). About two-thirds (66.6%, n = 272) of the total study participants felt that they were treated with respect all the time, and 240 (58.3%) of them reported that they were treated in a friendly manner all the time during their stay in the hospital. On the other hand, 61(14.8%) and 25 (6.1%) of women reported that they experienced verbal and physical abuse at least once during their stay at the hospital respectively (Table 3).

Table 3. Factors associated with PCMC of the women who gave birth at selected public hospitals of eastern, Ethiopia 2022 (n = 412).

Communication and autonomy

The percentage mean score of the participants was 61.1 (±6.2). More than three-fourths of the study participants 321 (77.9%) reported that providers never introduced themselves when they came to see them for the first time. More than half of the study participants 244 (59.2%) reported that providers called them by their names throughout their stay in the hospital. Slightly more than a quarter 108 (26.2%) women reported that providers had never explained the purpose of the examinations or procedures to them. Furthermore, one-third 134 (32.5%) of the participants reported that they were never asked for permission or consent during examinations (Appendix Table A1).

Supportive care

The percentage mean score of the supportive care subscale of the participants was 67.3 (±7.3). Nearly half of the participants, 201 (48.8%) reported that they were not allowed to be with someone they wanted during labor and the majority of them 369 (89.6%) were without a companion during delivery. In addition, 219 (53.2%) of the women reported that providers supported their anxiety and fears all the time during the childbirth process and 254 (61%) of them felt providers took the best care for them all the time (Table 3).

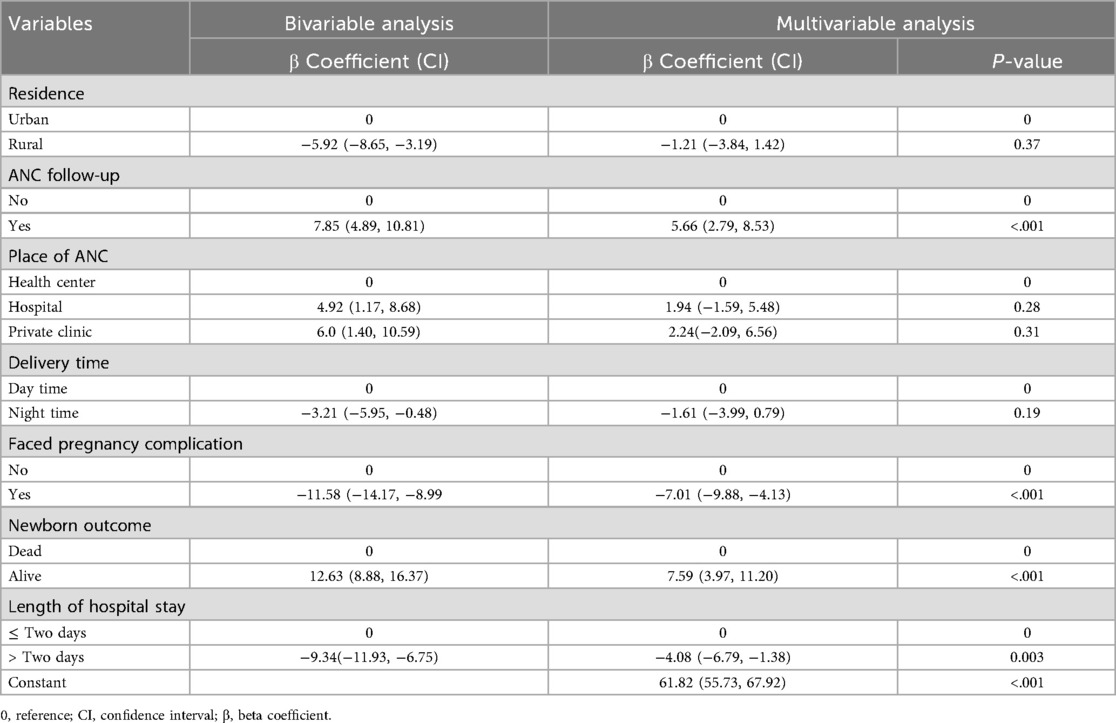

The factors that are associated with person-centered maternity care

From the overall variables entered into the simple linear regression analysis, residence, ANC follow-up, time of delivery, childbirth complications, newborn outcome, and length of hospital stay were eligible for the multiple linear regression analysis based on a P-value of less than 0.25. Ultimately, women who had ANC follow-up, faced childbirth complications, gave birth to a live newborn, and more than two days length of hospital stay remained significantly associated with person-centered maternity care (PCMC).

Women who'd had ANC follow-up had increased PCMC score by about 6 units compared women who had no ANC follow-up (β = 5.66, 95% CI: 2.79, 8.53). Women who faced childbirth complications had a lower PCMC score than those who didn`t face childbirth complication by 7 units (β = −7.01, 95% CI: −9.88, −4.13). Additionally, a live newborn outcome increased PCMC by about 8 units as compared to dead fetus newborn outcome (β = 7.59, 95% CI: 3.97, 11.20). By keeping all other variables constant, PCMC score was decreased by 4 units on those who had more than two days of hospital stay (β = −4.08, 95% CI: −6.79, −1.38) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study assessed the status of PCMC and its associated factors during childbirth at three selected public hospitals in eastern Ethiopia. The percentage mean score of the PCMC scale was 68.1% (CI: 66.75, 69.45). This finding is consistent with a study conducted in Kenya, 66.9% (25). Nevertheless, this finding is slightly higher than studies conducted in Ethiopia (64.5%) (19), 51.6% in Ghana (25), 62.0% in India (25), and 47.1% in Sri Lanka (9). This discrepancy may be attributed to variations in the availability of hospital resources and obstetric and sociodemographic profiles of the participants including ANC follow-up, childbirth complications, and educational status. For instance, the study conducted in India reported that 79% of the participants faced pregnancy complications, which was found to be a significant factor for the decrement of PCMC, as identified by this study and other previous studies (9, 20, 26, 27).

Women who'd had ANC follow-up had higher PCMC than those who had no ANC follow-up, which is consistent with a study conducted in Addis Ababa (28). The reason could be that, those who do have ANC follow-up are more likely to establish positive establish interactions with the healthcare providers and become familiar with the hospital environment. Furthermore, health providers counsel them on birth plan preparedness and any possible complications they may face during the childbirth process to help them prepare. And this results in a pleasant and cooperative intervention. In addition, ANC follow-up plays an essential role in health promotion, detection, and appropriate management of any pregnancy risk factors, which is a vital factor for a positive childbirth experience and PCMC.

Women who faced childbirth complications had lower PCMC score than those who did not face childbirth complications, which is consistent with the studies conducted in Addis Ababa, Bahir Dar, and Harar (20, 26, 28). The reason might be because women experiencing complications often require more medical interventions, which can shift the focus of care from a person-centered approach to a more clinical or procedure-oriented approach. This shift can lead to less attention being paid to the individual needs and preferences of the woman. Additionally, healthcare providers may be under increased time constraints when dealing with complications, which can limit their ability to provide emotional support (27, 29, 30). Furthermore, childbirth complications often induce functional limitations and anxiety, affecting the emotional well-being of the mother and potentially resulting in unpleasant client-provider interaction and a negative birth experience (31, 32).

Giving birth to a live newborn increased PCMC as compared to its counterpart. This finding is in line with the findings of studies conducted in Dessie and Kenya (10, 19). This could be because a positive birth experience is often associated with positive emotions such as joy, relief, and satisfaction. This positive emotional state can enhance the woman's perception of her care experience, making her more likely to report higher levels of engagement and person-centered maternity care. Positive outcomes can also foster an environment where providers are more attentive to the woman's preferences and needs. When outcomes are positive, healthcare providers may be more inclined to focus on the holistic needs of the woman, including emotional support and personalized care (33).

Conversely, women who had more than two days of hospital stay reported lower PCMC scores compared to their counterparts. This finding is supported by studies conducted in Dessie town, Ethiopia, and Kenya (19, 24). A possible explanation is that prolonged hospitalization may increase discomfort due to facility conditions, compromise privacy, and contribute to emotional stress. Moreover, extended stays are often related to maternal and/or neonatal complications, and all of these factors can decrease PCMC level.

The strengths and limitations of this study

As the first study conducted in this area, it uncovered the status of PCMC and its associated factors. However, a limitation of this study is that it was conducted only in public hospitals, which means it did not address the status of PCMC in private facilities within the study area. Moreover, the data related to PCMC were collected solely from participants' self-reports, making them prone to social desirability and recall bias. To help participants recall information, the time frame was limited to the six weeks postpartum period. Also, participants were informed and assured that their responses will remain anonymous and confidential, to encourage more honest responses. Furthermore, data collectors were trained to avoid leading questions in order to reduce the pressure to respond in socially desirable ways.

Conclusion

The study revealed that the mean person-centered maternity care score of the participants was higher than that in previous studies. Regarding the subscales, dignity and respect had the highest score, while the communication and autonomy subscale had the lowest score. Women who had ANC follow-up, faced childbirth complications, gave birth to a live newborn, and had a hospital stay of more than two days were significantly associated with PCMC. Therefore, we strongly suggest that strengthening of timely initiation and adherence to antenatal care follow-up, as well as early detection and appropriate management of childbirth complications, would greatly improve PCMC.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical clearance was obtained from Haramaya University, College of Health and Medical Sciences Institutional Health Research Ethics Review Committee (Ref. No. IHRERC/076/2022). The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Informed verbal and written consent was obtained from each study participant on a voluntary basis to be included in the study. On the other hand, an assent form was obtained for the study participants who are younger than 18 years old, in addition to the informed verbal and written consent of their legal guardians'.

Author contributions

AG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was financially supported by Haramaya University, Ethiopia. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, conclusion, or interpretation.

Acknowledgements

We are sincerely grateful to Haramaya University for the financial and administrative support. We would also like to thank the staff of the selected hospitals, the study participants, the data collectors, and the supervisors for their willingness and support throughout the data acquisition.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

ANC, antenatal care; CI, confidence interval; PCMC, person-centered maternity care.

References

1. CSA I. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016: Key Indicators Report. Ethiopia: Central statistics agency (CSA); Addis Ababa: ICF; Rockville: CSA and ICF (2016).

2. Li J, Porock D. Resident outcomes of person-centered care in long-term care: a narrative review of interventional research. Int J Nurs Stud. (2014) 51(10):1395–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.04.003

3. Care AGSEPoPC, Brummel-Smith K, Butler D, Frieder M, Gibbs N, Henry M, et al. Person-centered care: a definition and essential elements. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2016) 64(1):15–8. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13866

4. Plsek P, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Pr (2001).

5. Tunçalp Ö, Were W, MacLennan C, Oladapo O, Gülmezoglu A, Bahl R, et al. Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns—the WHO vision. BJOG. (2015) 122(8):1045. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13451

6. Ocansey K. Assessing Person-Centered Maternity Care at the LEKMA Hospital. Accra: University of Ghana (2019).

7. Bauman AE, Fardy HJ, Harris PG. Getting it right: why bother with patient-centred care? Med J Aust. (2003) 179(5):253–6. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05532.x

8. Hajizadeh K, Vaezi M, Meedya S, Mohammad Alizadeh Charandabi S, Mirghafourvand M. Respectful maternity care and its relationship with childbirth experience in Iranian women: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2020) 20(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03118-0

9. Rishard M, Fahmy FF, Senanayake H, Ranaweera AKP, Armocida B, Mariani I, et al. Correlation among experience of person-centered maternity care, provision of care and women’s satisfaction: cross sectional study in Colombo, Sri Lanka. PLoS One. (2021) 16(4):e0249265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249265

10. Sudhinaraset M, Landrian A, Afulani PA, Diamond-Smith N, Golub G. Association between person-centered maternity care and newborn complications in Kenya. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2020) 148(1):27–34. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12978

11. Ten Hoope-Bender P, de Bernis L, Campbell J, Downe S, Fauveau V, Fogstad H, et al. Improvement of maternal and newborn health through midwifery. Lancet. (2014) 384(9949):1226–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60930-2

12. Alliance WR. Respectful Maternity Care: The Universal Rights of Childbearing Women. Washington DC: White Ribbon Alliance (2011). p. 2017.

13. Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, Lutsiv O, Makh SK, Souza JP, et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Med. (2015) 12(6):e1001847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847

14. Rosen HE, Lynam PF, Carr C, Reis V, Ricca J, Bazant ES, et al. Direct observation of respectful maternity care in five countries: a cross-sectional study of health facilities in east and Southern Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2015) 15(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0728-4

15. Raj A, Dey A, Boyce S, Seth A, Bora S, Chandurkar D, et al. Associations between mistreatment by a provider during childbirth and maternal health complications in Uttar Pradesh, India. Matern Child Health J. (2017) 21:1821–33. doi: 10.1007/s10995-017-2298-8

16. Raine R, Cartwright M, Richens Y, Mahamed Z, Smith D. A qualitative study of women’s experiences of communication in antenatal care: identifying areas for action. Matern Child Health J. (2010) 14:590–9. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0489-7

17. Taghizadeh Z, Ebadi A, Jaafarpour M. Childbirth violence-based negative health consequences: a qualitative study in Iranian women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2021) 21(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03986-0

18. Callister LC, Edwards JE. Sustainable development goals and the ongoing process of reducing maternal mortality. J Obstetr Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. (2017) 46(3):e56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2016.10.009

19. Dagnaw FT, Tiruneh SA, Azanaw MM, Desale AT, Engdaw MT. Determinants of person-centered maternity care at the selected health facilities of Dessie town, northeastern, Ethiopia: community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2020) 20(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03221-2

20. Wassihun B, Zeleke S. Compassionate and respectful maternity care during facility based child birth and women’s intent to use maternity service in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2018) 18(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1909-8

21. Administrative H. Institutional Development Office. Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital report. (2017).

22. Afulani PA, Sayi TS, Montagu D. Predictors of person-centered maternity care: the role of socioeconomic status, empowerment, and facility type. BMC Health Serv Res. (2018) 18(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3183-x

23. Afulani PA, Diamond-Smith N, Golub G, Sudhinaraset M. Development of a tool to measure person-centered maternity care in developing settings: validation in a rural and urban Kenyan population. Reprod Health. (2017) 14(1):1–18. doi: 10.1186/s12978-017-0381-7

24. Afulani PA, Diamond-Smith N, Phillips B, Singhal S, Sudhinaraset M. Validation of the person-centered maternity care scale in India. Reprod Health. (2018) 15(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0591-7

25. Afulani PA, Phillips B, Aborigo RA, Moyer CA. Person-centred maternity care in low-income and middle-income countries: analysis of data from Kenya, Ghana, and India. Lancet Glob Health. (2019) 7(1):e96–109. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30403-0

26. Bante A, Teji K, Seyoum B, Mersha A. Respectful maternity care and associated factors among women who delivered at Harar hospitals, eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2020) 20(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-2757-x

27. Balde MD, Bangoura A, Sall O, Balde H, Niakate AS, Vogel JP, et al. A qualitative study of women’s and health providers’ attitudes and acceptability of mistreatment during childbirth in health facilities in Guinea. Reprod Health. (2017) 14(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0262-5

28. Tarekegne AA, Giru BW, Mekonnen B. Person-centered maternity care during childbirth and associated factors at selected public hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2021: a cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. (2022) 19(1):199. doi: 10.1186/s12978-022-01503-w

29. Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Tunçalp Ö, Fawole B, Titiloye MA, Olutayo AO, et al. By slapping their laps, the patient will know that you truly care for her’: a qualitative study on social norms and acceptability of the mistreatment of women during childbirth in Abuja, Nigeria. SSM Popul Health. (2016) 2:640–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.07.003

30. World Health Organization. New WHO Evidence on Mistreatment of Women During Childbirth. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO) (2020).

31. Fischbein RL, Nicholas L, Kingsbury DM, Falletta LM, Baughman KR, VanGeest J. State anxiety in pregnancies affected by obstetric complications: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. (2019) 257:214–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.07.007

32. Webb DA, Bloch JR, Coyne JC, Chung EK, Bennett IM, Culhane JF. Postpartum physical symptoms in new mothers: their relationship to functional limitations and emotional well-being. Birth. (2008) 35(3):179–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2008.00238.x

33. Dahlberg U, Aune I. The woman’s birth experience—the effect of interpersonal relationships and continuity of care. Midwifery. (2013) 29(4):407–15. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2012.09.006

Appendix

Keywords: person-centered maternity care, women, childbirth, public hospitals, Ethiopia

Citation: Gebreyesus A, Semahegn A, Tebeje F, Lonsako AA and Girma S (2025) Person-centered maternity care and its associated factors during childbirth at selected public hospitals in Eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Front. Glob. Women's Health 6:1513808. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2025.1513808

Received: 19 October 2024; Accepted: 26 August 2025;

Published: 11 September 2025.

Edited by:

Grant Murewanhema, University of Zimbabwe, ZimbabweReviewed by:

Enver Envi Roshi, University of Medicine, AlbaniaProjestine Selestine Muganyizi, University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Copyright: © 2025 Gebreyesus, Semahegn, Tebeje, Lonsako and Girma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Arsema Gebreyesus, YXJzZW1hbWFydGlAZ21haWwuY29t

Arsema Gebreyesus

Arsema Gebreyesus Agumasie Semahegn

Agumasie Semahegn Fikru Tebeje

Fikru Tebeje Arega Abebe Lonsako

Arega Abebe Lonsako Sagni Girma

Sagni Girma