- 1Department of Neuropsychiatry, Oita University Faculty of Medicine, Yufu, Oita, Japan

- 2Oita Occupational Health Management Center, Nishinihon Occupational Health Center, Oita, Oita, Japan

- 3Department of Psychology, Oita University Faculty of Welfare and Health Sciences, Oita, Oita, Japan

Background: Educational level is an important aspect of one's life and is associated with biopsychosocial and economic factors. The present study aimed to investigate the association of educational level with intelligence, affective temperament, and parental bonding.

Methods: This is a cross-sectional study. The dataset included 130 individuals consisting of 20 with high school education level, 51 with college education level, and 59 with university or higher education level. First, demographic data, including intelligence, affective temperament, and parental bonding were compared among the three groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Second, multiple regression analysis using stepwise method was performed, with educational levels as dependent variable and significant variables in the ANOVA as independent variables.

Results: Intelligence, maternal care, and male sex were significantly and positively associated with educational level, whereas age was significantly and negatively associated with educational level.

Conclusion: The present findings suggest that maternal care as well as intelligence may be associated with higher educational level. Further prospective studies are required to determine any causal relationship and investigate other factors related to educational level.

1 Introduction

Educational level is an important aspect of one's life and is associated with biopsychosocial and economic factors. When high school students determine whether they enter college, university, or not, they may think by themselves and consult their teachers, friends, and parents. In the course of decision-making, their temperament and their relationship with parents may be crucial. Moreover, their intelligence may be one of the most important factors for educational level.

Liu et al. (1) indicated that, in China, when mothers hold dominant positions in their children's educational decisions, they are more likely to adopt a “tiger mom” approach. Recently, maternal dominance in household decision-making has increased due to social development and evolving gender roles. This shift is reflected in the emergence of various family models, such as the dynamics of “Tiger Mom and Cat Dad”, “Wife Dominant and Husband Accompanying”, and “Supermom.” Therefore, exploring the impact of maternal dominance in children's educational decision-making on the development of adolescents' human capital is essential (1).

As for parental bonding, Ling et al. (2) showed that parental antipathy and neglect and mother negative loving (a form of insecure attachment) sequentially mediated the association between maternal control and adulthood antisocial personality disorder features. Geng et al. (3) suggest that it is important to pay attention to medical students (especially women) with low maternal care and low empathy (cognitive empathy in particular), and that these students are more likely to have depressive symptoms during their medical studies and clinical work. In UK, Reyes et al. (4) showed that lower maternal attachment in early life predicted increased adolescent multiple risky behaviors, and that almost a third of the excess risk was attributable to child, maternal and socioeconomic factors, with over a quarter explained by maternal depression.

In USA, Wegemer and Vandell (5) investigated early childhood antecedents of adult political orientation using longitudinal data, and found that mothers' beliefs and parenting behaviors, children's temperament, and attachment security during early childhood were related to political ideology and party affiliation at age 26. Young children's fearful temperament and anxious attachment security, as well as mothers' authoritarian parenting beliefs in early childhood, predicted conservative political orientations at age 26. Children's abilities to focus attention and avoidant attachment security predicted liberal orientations (5).

These findings are not directly associated with educational level, but possibly indirectly associated with the level via decision-making, which may be affected by intelligence, affective temperament, and parental bonding. In the present study, we hypothesized that higher educational level may be associated with higher intelligence, hyperthymic temperament, and more maternal care. The aim of this study was to investigate this hypothesis.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Subjects

We used data from a previous study (6) which was a prospective longitudinal study on psychotherapy in apparently healthy participants. In the previous study, the inclusion criterion was individuals aged ≥20 years who provided written informed consent. Participants were recruited via electronic bulletin boards, physical bulletin boards, and flyers. Individuals with serious psychiatric disorders, as determined by the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.), were excluded. The Institutional Review Board of Oita University Faculty of Medicine approved the trial (number B16-023). All participants provided written informed consent.

Although the previous study (6) had 137 subjects, our previous opt-out study (7) excluded 7 subjects and created the dataset of 130 subjects because of missing data. In this study, we used the dataset of 130 subjects, which included 108 females and 22 males, with a mean age of 49.3 years (SD = 12.1). This opt-out study was approved by the ethics committee of the Oita University Faculty of Medicine on June 12, 2023 (approval number 2536).

It should be noted that the dataset was originally obtained from a prospective longitudinal study (6), but that our current analysis was a cross-sectional study.

2.2 Educational level

Educational level was categorized into HE (high school education level), CE (college education level), and UE (university or higher education level). There were 20 individuals (female 19: male 1) in category 1, 51 (49: 2) in category 2, and 59 (40: 19) in category 3. The sex distribution along with educational level was significantly deviated (χ2 = 18.0, p < 0.001). It should be noted that category UE included three medical students.

2.3 Intelligence

The National Adult Reading Test (NART) (8) is widely used as a measure of premorbid IQ of the English-speaking patients with dementia. There is a Japanese version of the NART (JART), using 50 Japanese irregular words, all of which are Kanji (ideographic script) compound words. The JART has been translated into Japanese, and the reliability and validity of the Japanese version have been established (9).

2.4 Affective temperament

The Japanese version of the Temperament Evaluation of Memphis, Pisa, Paris, and the San Diego-auto questionnaire (TEMPS-A), a 110-item true–false questionnaire that assesses five temperament dimensions: depressive, cyclothymic, hyperthymic, irritable, and anxious (10). TEMPS-A has been translated into Japanese, and the reliability and validity of the Japanese version have been established (11).

2.5 Bonding style

Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) is a retrospective self-assessment measure of parental rearing attitudes experienced in childhood (12). The PBI consists of two subscales of “care” and “overprotection.” A high score for “care” indicates more appropriate rearing (less rejection and indifference), whereas a high score for “overprotection” indicates inappropriate overprotection (less encouragement of self-reliance). The PBI consists of 25 items (12 items for care and 13 items for overprotection), and each item is assessed on a 4-point Likert scale. The PBI has been translated into Japanese, and the reliability and validity of the Japanese version have been established (13, 14).

2.6 Data analysis

First, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the demographic data (age, parental bonding style, affective temperament, intelligence) across educational level (three category groups). Second, multiple regression analyses using stepwise method were conducted with educational level as the dependent variable and sex and ANOVA results (P < 0.05) as independent variables.

3 Results

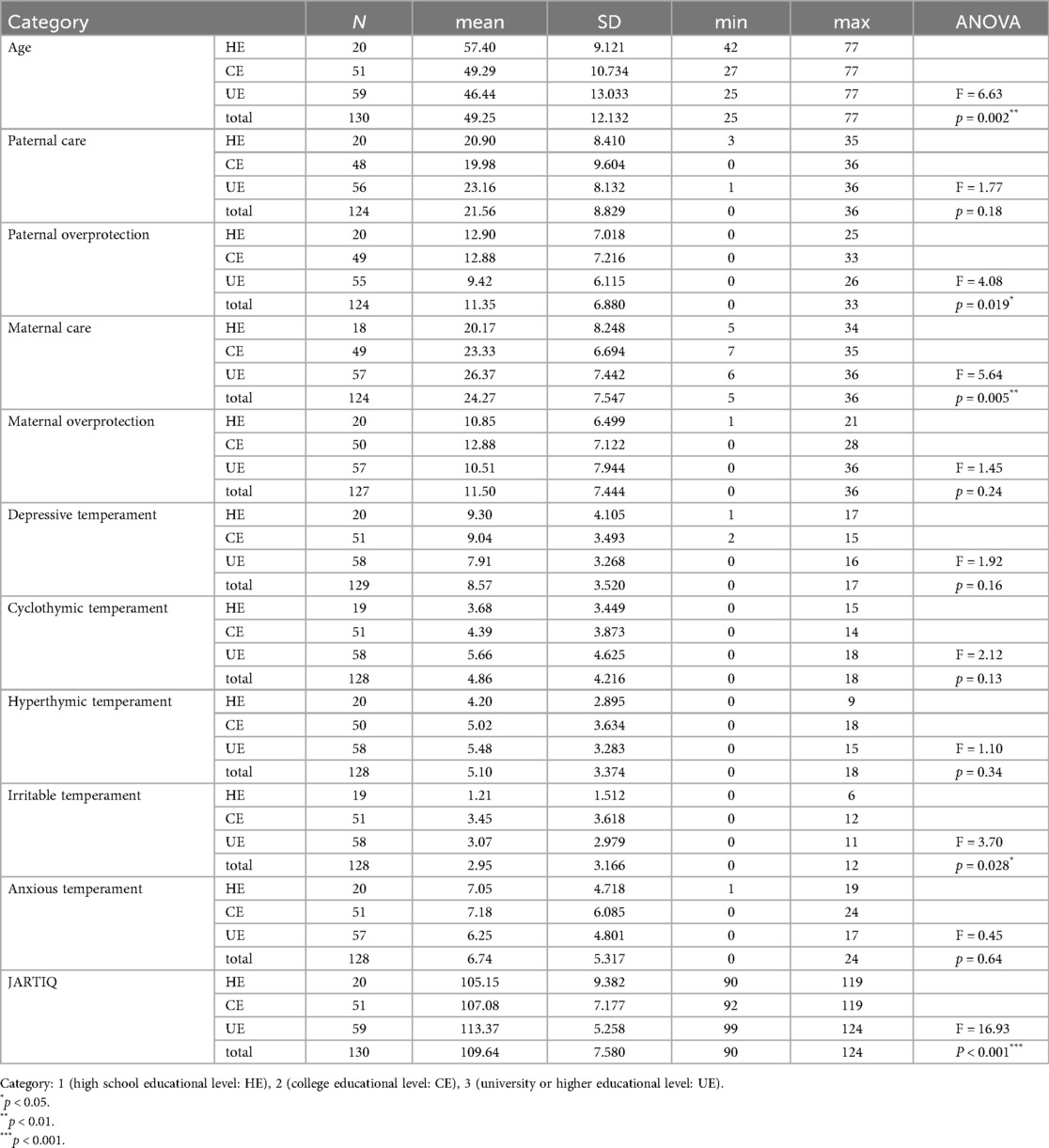

Table 1 shows the data of age, parental bonding style, affective temperament, intelligence across the three groups along with the results of ANOVA. Age, paternal overprotection, maternal care, irritable temperament, and intelligence were significantly different across the three groups.

Table 1. Demographic data, including age, parental bonding, affective temperament, and intelligence (JARTIQ) across educational level and results of ANOVA.

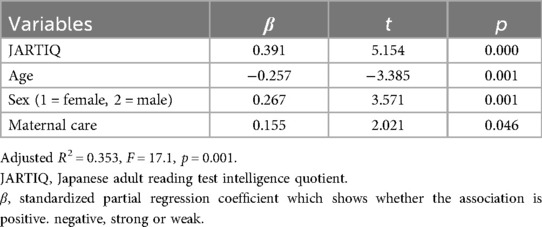

Table 2 shows the results of multiple regression analysis, where intelligence, maternal care, and male sex were significantly and positively associated with educational level, whereas age was significantly and negatively associated with educational level. On the other hand, paternal overprotection and irritable temperament were excluded from the model.

4 Discussion

The major findings of this study can be summarized as follows: (1) higher intelligence and more maternal care were significantly associated with higher educational level. (2) male sex and younger age were significantly associated with higher education level. To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating associations between intelligence, affective temperament, and parental bonding concurrently with educational level.

With regard to our hypothesis that higher educational level may be associated with higher intelligence, hyperthymic temperament, and more maternal care, the involvement of higher intelligence and more maternal care with higher education level is in agreement with the present results. Moreover, the importance of maternal care is in agreement with the previous reports (2–5). However, unexpectedly, hyperthymic temperament was not associated with educational level. Although the reason is uncertain, hyperthymic temperament may be independent from any educational level. As shown in Table 1, however, the scores of hyperthymic temperament and cyclothymic temperament increased along with the increase of educational level, although they were not significant. Possibly, this may suggest the modest involvement of common factor such as ambition between hyperthymic and cyclothymic temperament with educational level. Moreover, the “modest” involvement may be derived from the fact that majority of the subjects were females (108 females and 22 males). This is probably because hyperthymic male individuals can express themselves as they want, whereas hyperthymic female individuals can express themselves within the limited social culture where male dominance is still prevalent at least in Japan. Interestingly, this is contrast to “tiger mom” in China (1).

As for the involvement of male sex and younger age with higher education, in old Japan, male dominance was prevalent and female individuals were less likely to enter into higher education level. Since the present subjects had mainly females, the results may reflect such tendency in older individuals. Also, the fact that three medical students were included in the subjects may contribute to the negative association between age and educational level and the positive association between intelligence and educational level. In order to investigate this possibility, we excluded these medical students, but the results were almost unchanged (data not shown).

This study had some limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional study, and causal relationships could not be determined. Second, the sample size was relatively precluded to establish a definite conclusion. Third, JARTIQ could not measure total intelligence. Forth, the sample was heavily skewed towards females (108 females vs. 22 males), which limits generalizability. Because of small sample of males, however, we could not perform additional sex-stratified analysis. Fifth, recruitment through bulletin boards and flyers might have introduced selection bias. Sixth, the negative association between age and educational level could be due to cohort effects in access to education. Seventh, further studies are required to clarify why male sex and younger age were significantly associated with higher education level and conversely why female sex and older age were not associated with higher educational level. Finally, this study focused on only psychological aspects, and biological, social, economic, and cultural aspects should be considered as well. Particularly, important potential confounders such as socioeconomic status, parental occupation, and geographic location were not included. These factors could influence both maternal care and educational attainment.

In conclusion, the present findings suggest that maternal care as well as intelligence may be associated with higher educational level. Further prospective studies are required to determine any causal relationship and investigate other factors related to educational level stratified by sex.

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions. The data may be available upon request to the corresponding author. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to Takeshi Terao,dGVyYW9Ab2l0YS11LmFjLmpw.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Institutional Review Board of Oita University Faculty of Medicine. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in the studies. Moreover, this opt-out study was approved by The Ethics Committee of the Oita University Faculty of Medicine.

Author contributions

HH: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Formal analysis. TT: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. KK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AS: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. NK: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Liu C, Ren F, Yang L, Fan W, Huang X. Cognitive or non-cognitive? The effect of maternal dominance on adolescent human capital: evidence from adolescents’ educational decisions. Econ Hum Biol. (2025) 56:101463. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2024.101463

2. Ling H, Meng F, Yan Y, Feng H, Zhang J, Zhang L, et al. Why is maternal control harmful? The relation between maternal control, insecure attachment and antisocial personality disorder features in Chinese college students: a sequential mediation model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19(17):10900. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191710900

3. Geng Y, Fei W, Tang Z, Wang S, Yu J, Zhang M, et al. Parental care and depressive symptoms among Chinese medical students: roles of empathy and gender. BMC Med Educ. (2022) 22(1):451. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03524-2

4. Reyes BD, Hargreaves DS, Creese H. Early-life maternal attachment and risky health behaviours in adolescence: findings from the United Kingdom millennium cohort study. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21(1):2039. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12141-5

5. Wegemer CM, Vandell DL. Parenting, temperament, and attachment security as antecedents of political orientation: longitudinal evidence from early childhood to age 26. Dev Psychol. (2020) 56(7):1360–71. doi: 10.1037/dev0000965

6. Sakai A, Terao T, Kawano N, Akase M, Hatano K, Shirahama M, et al. Existential and mindfulness-based intervention to increase self-compassion in apparently healthy subjects (the EXMIND study): a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10: 538. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00538

7. Eto M, Terao T, Satoh M, Kawano N, Sakai A, Akase M, et al. The association of self-compassion with depressive temperament and Reading habit. Acad Ment Health Well-Being. (2024) 1. doi: 10.20935/MHealthWellB6176

9. Matsuoka K, Uno M, Kasai K, Koyama K, Kim Y. Estimation of premorbid IQ in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease using Japanese ideographic script (Kanji) compound words: Japanese version of national adult reading test. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2006) 60:332–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01510.x

10. Akiskal HS, Akiskal KK, Haykal RF, Manning JS, Connor PD. TEMPS-A: progress towards validation of a self-rated clinical version of the temperament evaluation of the Memphis, Pisa, Paris, and San Diego autoquestionnaire. J Affect Disord. (2005) 85:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.12.001

11. Matsumoto S, Akiyama T, Tsuda H, Miyake Y, Kawamura Y, Noda T, et al. Reliability and validity of TEMPS-A in a Japanese non-clinical population: application to unipolar and bipolar depressives. J Affect Disord. (2005) 85:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.10.001

12. Parker G, Tupling H, Brown LB. A parental bonding instrument. Br J Med Psychol. (1979) 52:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1979.tb02487.x

13. Ogawa M. A study of the reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the PBI (parental bonding instrument). Jpn J Psychiatri Treat. (1991) 6:1193–201.

Keywords: educational level, maternal care, intelligence, age, male

Citation: Hirakawa H, Terao T, Kohno K, Sakai A and Kawano N (2025) Associations between intelligence, affective temperament, and parental bonding with educational level. Front. Glob. Women's Health 6:1648474. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2025.1648474

Received: 20 June 2025; Accepted: 29 August 2025;

Published: 12 September 2025.

Edited by:

Ratih Wirapuspita Wisnuwardani, Mulawarman University, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Erri Larene Safika, Universitas Mulawarman, IndonesiaBasri Aramico, Universitas Muhammaiyah Aceh, Indonesia

Copyright: © 2025 Hirakawa, Terao, Kohno, Sakai and Kawano. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Takeshi Terao, dGVyYW9Ab2l0YS11LmFjLmpw

Hirofumi Hirakawa

Hirofumi Hirakawa Takeshi Terao

Takeshi Terao Kentaro Kohno

Kentaro Kohno Akari Sakai

Akari Sakai Nobuko Kawano

Nobuko Kawano