- Montana State University-Northern, College of Arts, Science, and Education, Department of English, Havre, MT, United States

Posthuman “borderlands” are represented in literature as diverse repetitions of similar dynamics of power. The postcolonial literature of Haiti presents a unique situation in comparison to the networks of power observed in political economic theory. Colonized people are the central actors in Haiti: they create posthuman entities such as the zombies to reclaim a political agency. Employing network theory to new genres of narrative such as non-fiction accounts and even social science texts, one can begin to map networks of power and counter-power in literature using digital humanities methods that demonstrate the conflicts between colonized communities and the analytical frameworks of mobilized Western anthropology. Moreover, the undead corpse provides a powerful medium for violent social commentary on postcolonial societies’ cultural capital that resists social structures created to ignore or suppress historical counter-narratives. In this case, Caribbean voudoun societies retain a genealogy of traditional African American understandings of the zombie to resist cultural appropriation in Anglo American literature. Ethnographic and sociological approaches have yielded substantial documentation of the religious underpinnings of the Haitian zombie; however Wade Davis’s The Serpent and the Rainbow (1985) was the most scientifically successful and popular narrative. Using methods of network theory applied to literature, an approach to The Serpent and the Rainbow that maps Davis’s relations to academic networks in the United States and local acquaintances in Haiti reveals a religious network powered through brokerage, closure, switching, and programming that perpetuates the mysticism of the zombie as a unique form of social resistance capital.

Introduction

The undead corpse provides a powerful medium for violent social commentary on postcolonial societies’ cultural capital that resists social structures created to ignore or suppress historical counter-narratives. The folkloric and anthropological phenomena of Caribbean voodoo (vodu, vodun, voudoun, vodoun) societies, traces its genealogy to traditional African American zombification practices as they were absorbed into Anglo American cultural works. Ethnographic and sociological approaches have yielded substantial literature on the religious underpinnings of the Haitian zombie societies since at least the end of the 19th century with St. John’s Hayti (1889), but especially since the American occupation, including Seabrook (1929), Leyburn (1941), Deren (1953), Huxley (1966), and Metreaux (1975); however Wade Davis’s The Serpent and the Rainbow (1985) was the most recent and popular narrative, and still generates scientific discourse over the Haitian cultural practice of zombification, i.e., the “zombie hypothesis.” Davis’s social analyses of the secret societies within Haitian voodoo revealed more detailed methods of zombie production, which had remained mysterious to Western academia. The techniques of counter-power his work identified for Western scholarship demonstrate that the zombie societies conceal themselves within a highly de-centralized network of social rebellion against Western cultural imperialism present in Haiti since the colonial period. Using methods of network theory applied to literature, an approach to The Serpent and the Rainbow that maps Davis’s relations to academic networks in the United States and local acquaintances in Haiti reveals a religious network powered through brokerage, closure, switching, and programming that perpetuates the mysticism of the zombie as a unique form of social resistance capital. Additionally, this network theory approach to creative nonfiction demonstrates a novel method for analyzing postcolonial narratives in general.

The Serpent and the Rainbow is difficult to place in the genres of creative nonfiction. The book operates much like a cognitive network of information and relationships contained in three trips between Haiti and Harvard, collections of songs and dances, rituals and recipes, historic accounts and quoted publications—all of which is tied together in Davis’s pursuit of zombification methods and techniques. Its inability to be classified often means that the book is considered too scientifically radical for pharmacologists, strikes as too idealistic to anthropologists, and goes unnoticed by literary critics; but locating Davis in the interstitial space between genres should not exclude it from analysis as a postcolonial travel narrative. To label Davis as a simple enthusiast of pseudo-science ignores the social networks and rituals that he examines and participates in, while merely regarding his work as a tourist’s travel writing falls short of considering the implications of the potential interplay between rural networks of Haitian secret societies and the material analysis of the substances they use to augment their mystical regulation of the countryside. Therefore, Davis’s experience as an ethnographer contracted to broker relations between Haitian officials and New York pharmaceutical reps is best understood when read as a process of social and cognitive network mapping. Davis’s book, albeit nonfiction, still manages to formulate a plot around his research aims and method of investigation—that is, following new and established leads, forming informational nodes within Haiti to learn the truth about zombification, and connect with the secret societies that create them. Reading Davis as he attempts to map a historically closed and exclusive organization through network concepts such as brokerage, closure, switching, and programming helps us to understand how secret societies function in general, as well as identify the mechanisms generating and consolidating power within a subaltern network.

Theoretical framework

Deleuze and Guattari (1987) (early in the development of network theory) assert that the rhizomatic nature of de-centralizing power relations presents the radical opportunity for novel forms of differentiated resistance and “lines of flight” (Massumi, 1987). The rhizome, however, depends on the critical axiom that networks are inherently egalitarian, democratic, and become more resistant to unilateral exercises of power as they decentralize and proliferate along new multiplicities of nodes. Jameson (1988) further contends that “Cognitive Mapping” is a material visualization of modern networks that is consistent with these assumptions in Wade Davis’s method of analysis, which makes use of an aesthetic modality emphasizing the connections between literary and empirical evidence, historical and present artifacts, and a multiplicity of contacts from every Haitian socioeconomic group. Jameson makes a distinction between mapping power and resistance to postindustrial society and the networks that exist outside the reach of multinational capitalism or socialist states: “with one single exception (capitalism itself, which is organized around an economic mechanism), there has never existed a cohesive form of human society that was not based on some form of transcendence or religion.” (p. 351). This classification frames rural Haiti as an agrarian peasantry that is home to 80% of the Haitian population directly in the interstitial space between capitalist and socialist states, where voudoun is the basic unit of societal regulation and religion. Thus, while the secret societies of Haiti clearly form tangible networks in Davis’s experience and research, they operate on an axis of power/knowledge relations generated from ontologies and epistemologies disconnected from capitalistic understandings of society.

Not all of Davis’s contacts in Haiti originate in the voudoun community. It is important to consider that he may not have penetrated the secret societies of the voudoun priests and priestesses (houngan and mambos, respectively) at all, if not for his partnership with scientists in Cambridge and New York, or the exchange of knowledge and the facilitation of introductions via government officials in Port-au-Prince, i.e., the “national face” of Haiti. Galloway and Thacker (2007) begin their assay with the Deleuzian phrase “we are tired of trees”—an obvious comment on modern skepticism with Deleuzian theory—to demonstrate that networks in the Digital Age are not necessarily the democratizing constructs we assume them to be. Sovereignty still plays a role in creating and controlling networks, especially in the modern state of emergency that characterizes global policy shifts from an emphasis on reactionary defense to an emphasis on preemptive security. Sovereign power to make unilateral decisions can actually be augmented by anatomico-political means of discipline, biopolitical power-knowledge, and other bottom-up forms of totalizing regulation (i.e., the “Foucauldian argument”) utilizing “a veiled, cryptic sort of multilateralism.” (p. 9). Mechanisms of network power between the state and the peasantry in Haiti need to be considered as a partnership between institutions, especially since the reign of a voudoun pseudo-theocrat in “Papa Doc” Duvalier and his Tonton Macoute. In “A Network Theory of Power,” Manuel Castells defines four theoretical forms of power latent in the network that resemble what Davis found in Haiti:

1. Networking Power: the power of the actors and organizations included in the networks that constitute the core of the global network society over human collectives and individuals who are not included in these global networks.

2. Network Power: the power resulting from the standards required to coordinate social interaction in the networks. In this case, power is exercised not by exclusion from the networks but by the imposition of the rules of inclusion.

3. Networked Power: the power of social actors over other social actors in the network. The forms and processes of networked power are specific to each network.

4. Network-making Power: the power to program specific networks according to the interests and values of the programmers, and the power to switch different networks following the strategic alliances between the dominant actors of various networks (773).

The Serpent and the Rainbow demonstrates these four themes through unique Haitian forms of power and counterpower exercised by the network actors.

Identifying the four modes of network power in practice requires an operationalization of the sociological phenomena that are quantified in the social network’s structure. Barabasi (2016) demonstrates the methods of network analysis in application to modern military strategy, epidemiology, information technology, and social media, among other examples. “Indeed, behind each complex system, there is an intricate network that encodes the interactions between the system’s components.” (p. 6). In Davis’s sociological context, these interactions might be qualified as types of network switching, programming, brokerage and closure. Ronald Burt applies this terminology in Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital (Burt, 2005) to analyze the exchange of knowledge at key nodes in the organizational network of a large American electronics company, discovering that those who filled structural holes in the corporation between different departments or locations were often rewarded to a significantly higher degree with job promotion and pay increases than their partners who engaged in closure—forming strong ties in a highly clustered sub-network, but limiting access to the entire social body. Moretti (2011) has translated these methods of interpreting brokerage into literature, analyzing Hamlet, Macbeth, and King Lear in terms of their clustering, questions of central characters, and brokerage. He proposes “this is exactly what network theory tempts us to do: take the Hamlet-network and remove Hamlet, to see what happens” (p. 86). His multiple figures demonstrate the character mapping method and the crucial place of social brokers between different groups. He removes those brokers from the network to highlight the structural functions they fill; namely, he emphasizes the brokerage of Hamlet and Horatio, as opposed to the centrality of the sovereign Claudius.

To establish a coherent theory of networked borderlands, one must begin to identify the repetitions and variations of power dynamics at work in the literature of these colonizing/colonized settings. Some of these power dynamics reach beyond Western scientific understandings of the body and humanity. Therefore a “posthuman” method of network analysis is warranted. In Haiti, attempting to penetrate the social networks of the rural peasants has been a subject of intense scholarly interest for several centuries. However, direct contact with Haitian culture was renewed in the American context with the occupation leading into WWI. While the marines inflicted over 15,000 casualties among the Haitian rebels threatening the Haitian American Sugar Company (HASCO) and supporting German interests in the Carribean, social anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston was in the process of conducting her initiation into voudoun, the experience of which she documents in Tell My Horse (Hurston, 1990). The Roman Catholic Church and the Haitian government sought to cleanse the island of voudoun worship and zombification practices: Article 249 of the Haitian Penal Code prohibits the use of any powder or other substance that induced a lethargic coma indistinguishable from death. At the same time, the secret societies known by such names as the Bizango, Zobop, San Poel, and Macandal kept up business in the rural towns and villages as normal, working either in the local government itself, or else hand-in-glove with the local authority. This officer is known as the chef de section, who draws his resources from the locals, rather than the federals, meaning that his loyalties are closer to the village houngan than the Presidency. Hurston was unable to fully penetrate the nocturnal gatherings of the Bizango (the chief society that Davis and Hurston have contact with in the region of Saint Marc and Gonaives), yet she came across several zombified individuals poisoned with a coup poudre supplied by a bokor (a houngan trained as a sorcerer/necromancer) that possibly contained toxic levels of tetrodotoxin (TTX). TTX would paralyze the victim until they were pronounced dead. In theory, bokors return to the grave to unearth the body, revive it with a hallucinogenic paste derived from the species of datura growing on the island, and rechristen the corpse with a new identity as a laborer in an undisclosed location.

Laguerre (1980), another Haitian anthropologist in the 1970s and 80s that Wade Davis cites as instrumental to his argument, “managed to begin to answer some of the questions raised by Hurston’s fieldwork,” verifying “the existence of passports, ritual handshakes, and secret passwords, banners, flags, and brilliant red-and-black uniforms” in the mystical hierarchy of the Bizango (Davis, 2010, p. 298). “In fact, so ubiquitous are these societies that Leguerre described them as nodes in a vast network that, if and when linked together, would represent a powerful underground movement capable of competing head-on with the central regime in Port-au-Prince” (p. 212). Davis demonstrates both in his fieldwork and the body of prior evidence that he believes voudoun was born in a unique colonial context, with close ties and closure to external networks, maintaining its secret existence through periods of changing religio-political landscapes.

Davis’s method of mapping follows the commodity circulation in a network, much as Beal (2012) traces sugar cane as “a material networking agent that links the people, places, and practices of the text by its very circulation” in Toomer’s Cane (p. 670). The powders, poisons, and magic of the houngan are the material commodities fetishized by Davis and his backers, Nathan S. Kline and David Merrick. Magical powders provide the quantifiable link between him and the social connections he establishes. The economic and pharmaceutical interests of those in the New York support network is important to consider, as it provides Davis with a form of Castell’s “networked power.” Davis’s fetish for the truth behind these materials is not economic commodification in the Marxist sense, but rather an anthropological of Jean Claude Levi-Strauss: Davis is drawn to the ways that the powders are employed, the techniques and rituals of social production that make the powders function as a source of religious and secular power in rural Haiti. Using Gephi network quantification software, I plan to map the connections between the individuals with whom Davis associates throughout his research narrative, quantifying the network connections, the degree of centrality for each person in his narrative, and thus the kinds of power that each actor exerts through and over the network.

Methodology

This study employs network theory as a framework for analyzing The Serpent and the Rainbow. Following Deleuze and Guattari’s rhizomatic model of decentralized power, and Manuel Castells’ network forms of power, this paper maps the relationships between Davis and key actors in the Haitian religious network. Utilizing digital humanities methods, Gephi software quantifies and visualizes connections between individuals in the text, highlighting degrees of brokerage, closure, switching, and programming. By integrating ethnographic research with network mapping, this study contextualizes Davis’s findings within broader power structures, demonstrating how Haitian secret societies resist colonial and neocolonial forces.

Results

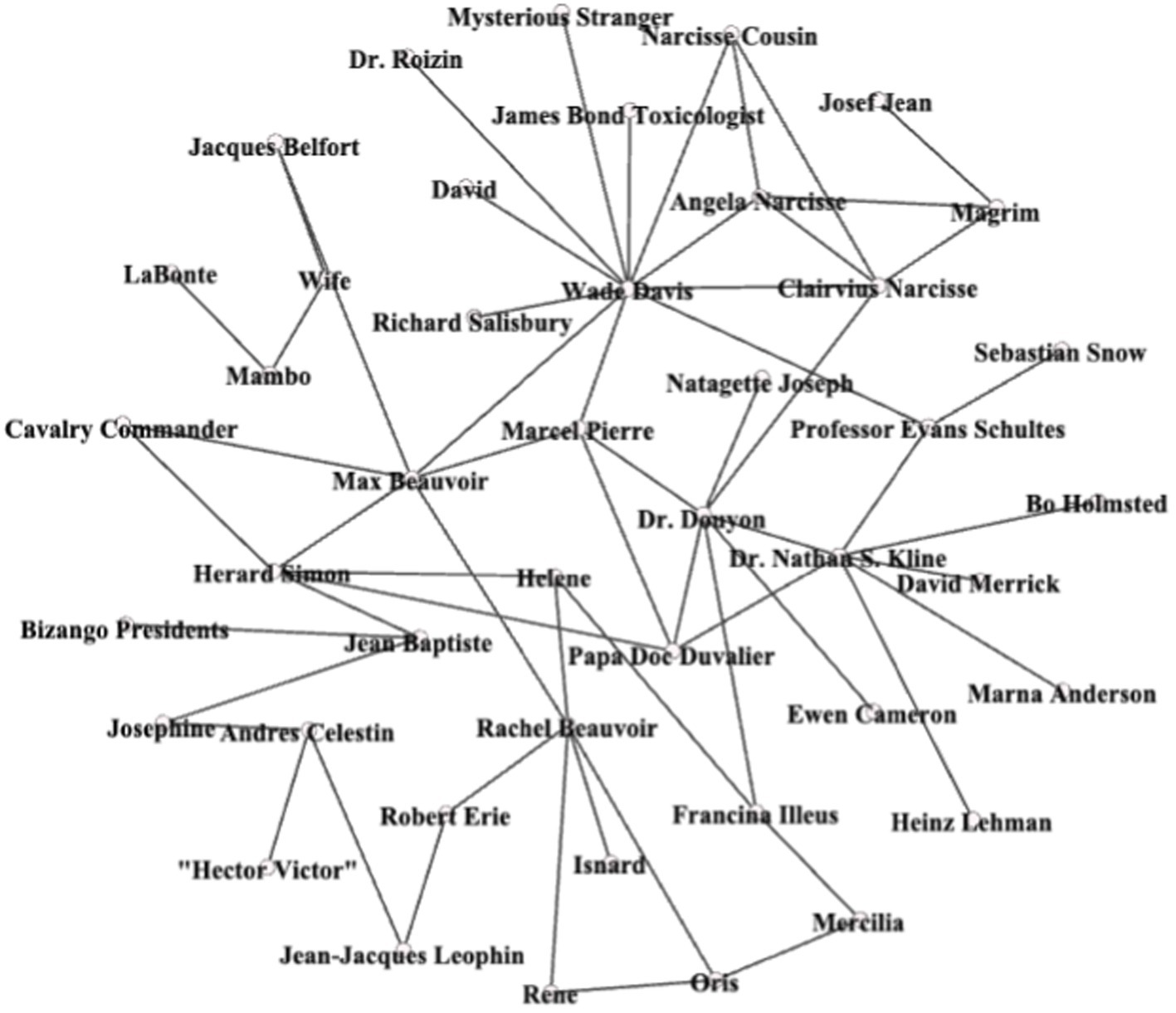

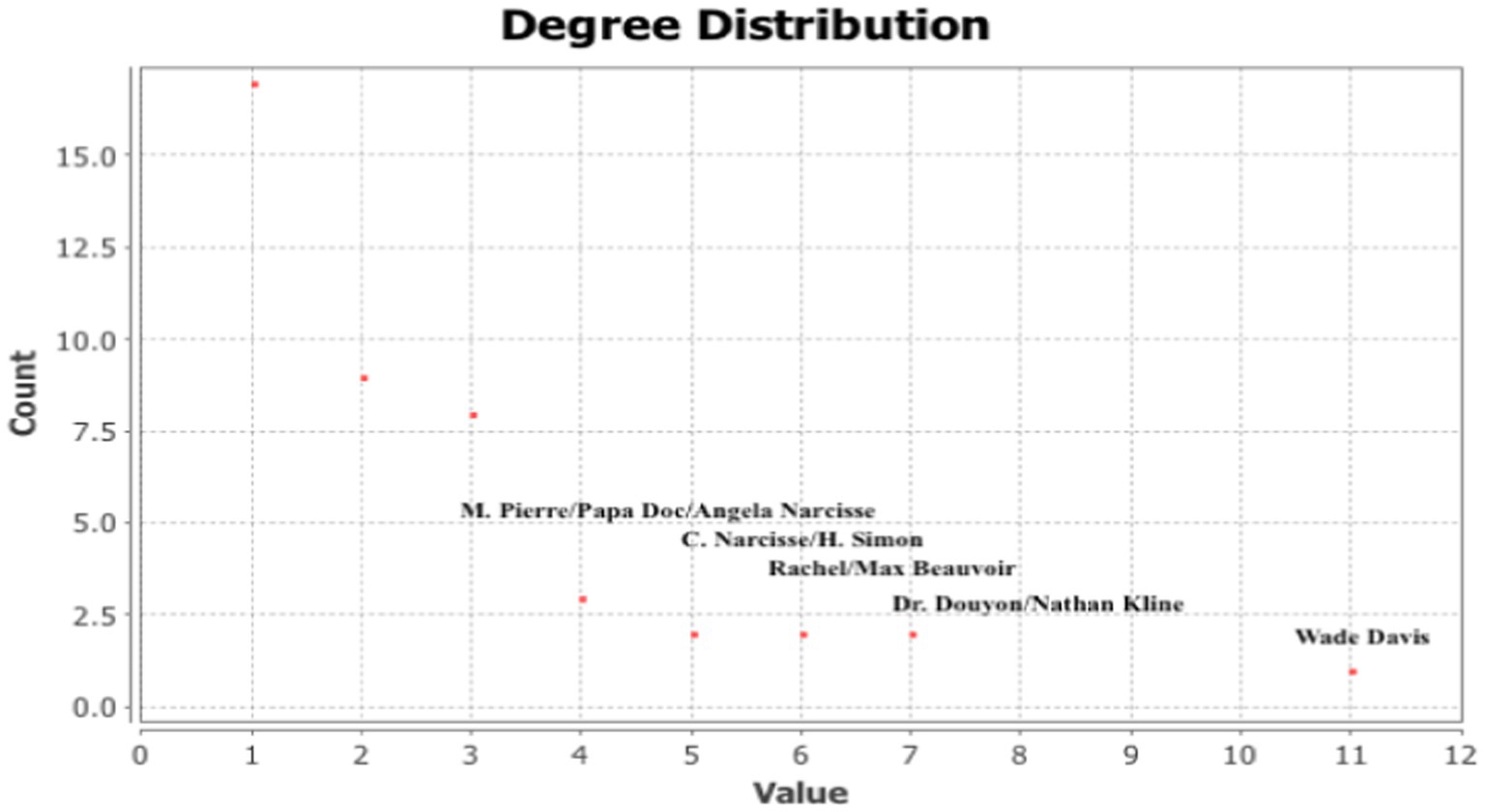

Davis’s network is transnational. As the author of the network map reproduced using Gephi network quantification software, he is shown to be a highly central character (for ranked harmonic measures of centrality, see Supplementary Appendix 1). At the same time, he also a broker for many others (see Figure 1). His ability to network with highly specialized sources across medical communities in Cambridge and New York is crucial to determining which leads to follow in Haiti, the composition of the sample powders that he brings back from Marcel Pierre, and his ability to connect with local houngan and prominent Haitian physicians. Aside from his chief Haitian brokers—Marcel Pierre, Dr. Douyon, and Max Beauvoir—Davis’s contractor, Dr. Nathan S. Kline, occupies a key position in bringing together medical experts to rethink the zombie hypothesis. Kline is additionally linked to important Haitians through his time working as a mentor to Dr. Douyon, and his past relationship with dictator Papa Doc Duvalier. Using these relationships, Davis is able to establish a network of Douyon’s zombified patients, documenting the first case of zombification recorded by Western physicians with the patient Clairvius Narcisse.

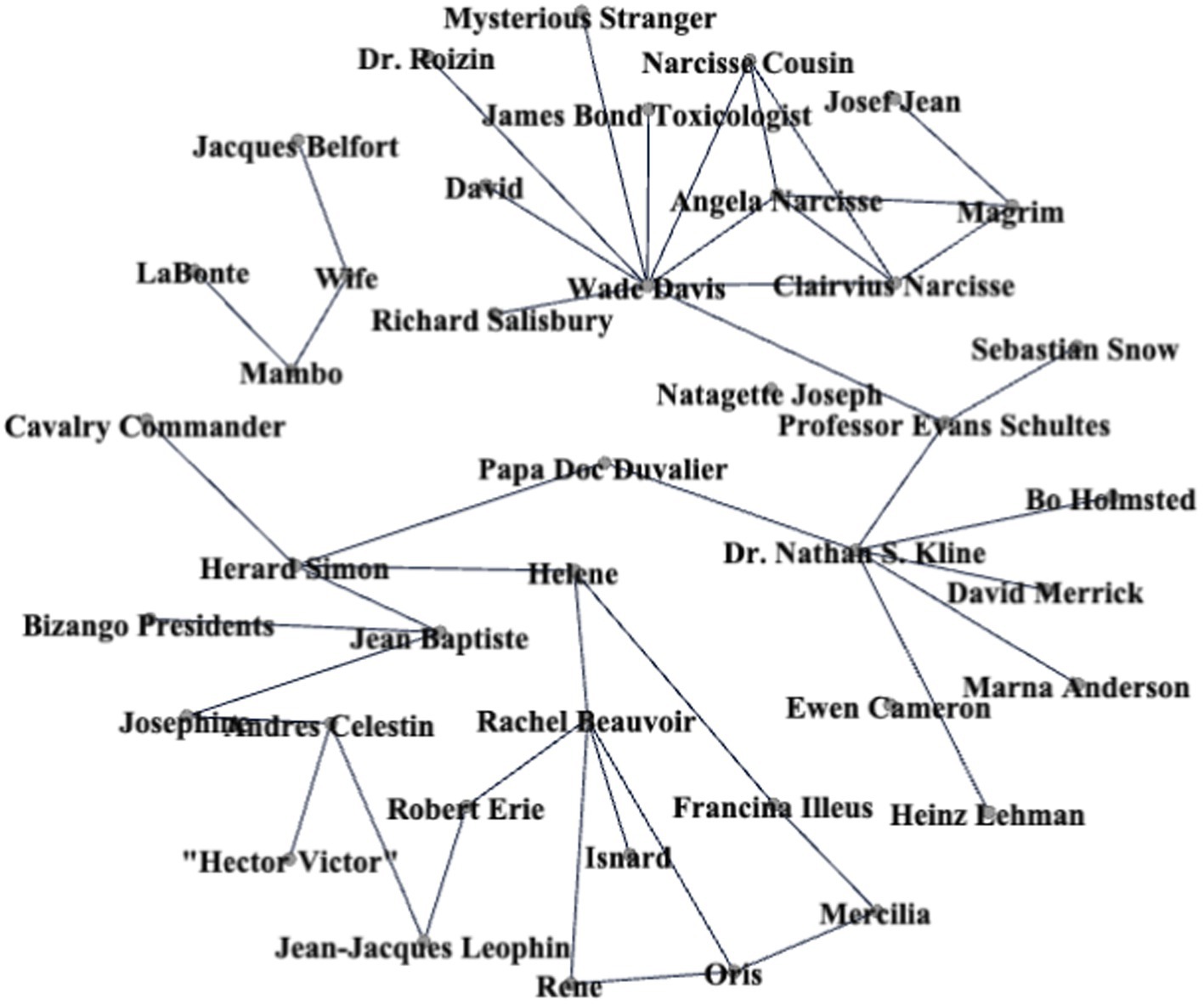

In contrast, the Haitian social network perpetuates itself through regulated closure to the secret societies. Nathan Kline and Davis’s American contacts aside, Marcel Pierre, Max Beauvoir (both houngan) and Dr. Lamarque Douyon represent Davis’s primary contacts in Haiti (the next three highest ranks in harmonic centrality, see Supplementary Appendix 1). It is through these men of prominent social standing that Davis meets all other houngan and bokors, secret society presidents, and ex-leaders of the Tonton Macoute, i.e., Papa Doc Duvalier’s paramilitary organization meant to protect him from the regular military and political opponents through the combined use of violent force and voudoun magic. Many Tonton Macoutes were indeed already sorcerers and necromancers, if not learning the trades through houngan that supported Duvalier. In popular mythology, Duvalier himself was also a sorcerer, and his Tonton Macoutes could potentially recruit zombies to swell their ranks with loyal, mindless followers. Therefore, with Davis’s three primary contacts in Haiti removed from the network, their importance as brokers is highlighted in their absence. The connections of a deceased Papa Doc Duvalier are the only link between Davis and the network of houngan who might have met Nathan Kline through the ex- dictator (see Figure 2).

Davis recognizes that Duvalier “was the first national president to take a direct personal interest in the appointment of each chef de section” (Davis, 2010, p. 364). While these local prefects were primarily peasants and worshippers of the loa (voudoun spirits and gods), if not simply houngan themselves, they had demonstrated nearly autonomous rule over rural villages during times of political upheaval in the capitol, drawing most of their resources from grassroots networks rather than the inconsistent governmental salary. Duvalier recognized their importance in reaching the capillary institutions of government in rural Haiti, thus extending his reach to individuals within the secret societies in terms of decentralized regulation. Reading Davis for networks has the historical advantage over Hurston in that his analysis of the secret societies and their networks come after the reign of the Duvaliers, when voudoun reached national recognition and respect.

Davis demonstrates Castell’s “network-making power” in Papa Doc’s self-fashioning as the head of a theoretically national secret society via close ties with the chef de sections, who allowed him to become the very embodiment of the “Guardian of the Cemetary,” Baron Samedi (p. 364). The organizational structure of his deposed Macoutes continues in Davis’s experience through a love/hate relationship with local secret societies. Duvalier essentially functioned as a programmer for the modern social network of voudoun in Haiti, and Davis capitalizes on the remnants of his militia’s structural brokerage. Herard Simon (fifth in centrality, see Supplementary Appendix 1) introduces himself through Max Beauvoir (whom is ranked highest of all characters in measures of “Betweenness Centrality,” a graph theory metric that measures how nodes act as bridges between other nodes, and are therefore critical to the flow of information or resources) as the first secret society president willing to talk with Davis. Albeit, he is a society of one, being shunned by local societies as a former commander in the Macoute, who once administrated “a full fifth of the country.” (p. 363). He “did not kill any people” however, “only enemies.” (p. 363). Herard’s reputation as a powerful sorcerer keeps him involved in Max Beauvoir’s circle of houngan, and introduces Davis to the network of secret society presidents through the powerful Jean Baptiste at a nocturnal, invite-only ceremony.

Marcel Pierre (fourth in centrality, see Supplementary Appendix 1), as another Macoute and thus network-making agent, becomes a primary resource for Davis and his financial backers by supplying the zombification powder and initiating Davis into the basic rituals and formulas of a bokor. As a part-time sorcerer-for-hire, part-time barkeep and pimp, Pierre has clearly fallen from his place of authority and prestige in the Macoutes. Every time Davis describes the chemical facial burn that Marcel received from the zombie poison that almost killed him, readers are reminded that Marcel himself was the victim of a rival houngan who punished him for his intrusions into the dealings of the Bizango on his quest for their magical power/knowledge. Brokerage for Marcel, as with the other mercenary houngan, becomes a form of resistance capital both against “networked power” exercised by the government hierarchy in Port-au-Prince (and the French colonial authorities before them) over rural Haiti, as well as the “network power” that the secret societies hold over all members. Marcel profits from a relationship with Westerners that allows him to use his knowledge of voudoun and break the vows of secrecy that are exacted by all society leadership. He also recognizes the power that voudoun has to undermine and overthrow conventional forms of governmental regulatory power. Maneuvering between both worlds as Marcel Pierre does can cost anyone associated with the secret societies their life, and Davis decided to “curtail his work” with the mercenary Andres Celestin, rather than risk initiation and thus legally becoming subject to the types of punishments that a Bizango tribunal visited on Marcel for his meddling in their affairs (p. 376). It is no coincidence that the advice to break off Davis’s initiation comes from Herard Simon, a Macoute who has experienced the rejection of other houngan for living in the liminal space between liminal spaces.

When Marcel Pierre’s (favorite) wife begins to die from a mysterious case of uterine hemorrhage, the fearsome necromancer reveals another side of his personality and another aspect of Castells’ “network power”: a houngan’s treatment of another sorcerer down on his luck. The bokor LaBonte, whom Davis contracts to create a lethal powder after Pierre, reminds the author “You best remember one thing. We can be sweet as honey, or as bitter as bile.” (p. 207). When Marcel Pierre appeals to Max Beauvoir, a fellow voudoun priest, for a place to stay in the city and financial aid to buy blood for his wife, Beauvoir helps him without question. Pierre’s actual standing in the hierarchy of the Bizango’s network becomes clear to Davis: “Marcel was an outcast, a pimp, a malfacteur, a powderer, and now more than ever I sensed his isolation. Haitian men do not cry, tears slipped from Marcel’s eyes. My hand held his, but there was nothing more I could do.” (p. 340). Even in his lowly position, Marcel could depend on other houngan to incorporate him into their support network during moments of need. Jean-Jacques Leophin, a senior Bizango president (i.e., an “emperor”) emphasizes the scale and versatility of his network, and the power “exercised not by exclusion from the networks but by the imposition of the rules of inclusion” (Castells, 2011, p. 773). This power is not altogether destructive, as seen in the treatment of Marcel Pierre. “You see, we are stars,” Leophin asserts in his metaphor describing the scope of the secret society network. “We work at night but we touch everything. If you are poor, I will call an assembly to cover your needs. If you are hungry, I will give you food. If you need work, the society will give you enough to start a trade. That is the Bizango. It is hand in hand” (Davis, 2010, p. 360). Marcel and others, such as Clairvius Narcisse, can be judged and punished by the magic of the society, but clearly they also benefit from a system that invests in protecting the health and legal rights of the people.

To properly care for society members, Davis’s houngan regulate closure to the secret societies’ networks, and include Max Beauvoir, Marcell Pierre, Jean-Baptiste, Jean-Jacques Leophin, LaBonte, Josef Jean, Andre Celestin, and “Hector Victor”—the spirit who possesses and rides Celestin’s body during rituals, and “tells his horse” what to do after he dismounts (p. 370). These religious leaders are not all as central to the network that Davis attempts to map, nor vitally connected by as many degrees as Davis, Kline or Dr. Douyon (see Figure 3 for degree frequencies). However, Davis recognizes Castell’s final form of “networking power” in the houngan and their secret societies, which draw their mysticism from their secrecy, or the creation of structural holes between rural Haiti and the rest of the world. Networking power is measured by the influence of exclusion, by the social network that utilizes its knowledge to exert influence “over human collectives and individuals who are not included in these global networks.” (Castells, 2011, p. 773). In the case of “Hector Victor,” only Andres Celestin is able to establish a relationship with the spirit, and operates in mystical rituals as an extreme example of closure: he can only appear at certain times, and supposedly only through one broker in the priest he possesses. Davis’s ethnographic method takes this mysticism as a technique of power, identifying scientific success not in “the inherent status of information” but rather “the relationship one managed to establish with a knowledgeable informant,” since “The purpose of secrets is to protect a society’s interests from threatening outsiders. If a relationship can be established that renders one no longer a threat, the need for the protective veil vanishes.” (p. 121).

As Davis approaches his initiation into the Bizango, he comes to understand what the mysterious stranger at his hotel meant when he told the author “Perhaps you shall know the other Haiti, if you can bear it. We are a nation of three—the rich, the poor, and myself. We have all forgotten how to weep. Our wretched past is forgotten as a foul dream, an awkward interlude.” (p. 68). The “other Haiti” is the secret societies, the uncharted villages run by the ubiquitous chef de sections and the houngan, who mediate between the rich and the poor, albeit forgetting their purpose at times, as is the case of sorcerers who turned to the Ton Ton Macoute. This “wretched past” is both a reference to recent history and the heritage of the slave trade, which moved many of the secret societies of the Slave Coast to the plantations of Saint Domingue, including the “Egbo, or Leopard Society,” whose traditions carry over into modern Bizango practice (p. 54). Many voudoun leaders became prominent generals in the Maroon cause over the course of the 18th Century. Early houngan like Dutty Boukman organized networks of followers into tormenting plantations with guerrilla tactics resembling a “clandestine network that maintained the flow of goods and information between the plantations and the Maroons.” (p. 271). Yet this historical context provides a paradox for Davis, who seeks recognition among the Bizango, but also to study them.

The Bizango network is threatened by outsiders because of what they have done and can still do to their system. A society president puts the question to Davis’s research purpose bluntly: “Why is it that a blanc is here to listen to our words?” (p. 349). Davis establishes network mapping as a key scientific activity that could lead to a deeper appreciation of diverse cultures and identify technologies of power within those societies for medical appropriation; but does his liberalism and scientific innocence give him justification for his documentation of the network when it operates primarily through secrecy? Invoking the historicism of Dutty Boukman, the houngan who performed the voudoun blood ritual at Bwa Caiman in 1804 and initiated many of the early slave revolts through their religious network, a Bizango member demands that the ceremonies halt in Davis’s presence: “Wait a minute! The ceremony at Bwa Caiman was a purely African affair. There should be no blanc assisting with this ceremony of ours tonight! No blanc should see what we do in the night” (p. 350). A clear minority develops among the Bizango that recognizes a threat in Davis because they claim a colonial narrative is integral to the identity of voudoun. Protecting the historical ties between the secret societies and their orchestrations of rebellion against the French, Spanish, and British in the colonial era, and resistance to the Americans and the Ton Ton Macoute in postcolonial times is important for the power of a subaltern rural Haitian network, which operates on principles of governmentality that enforce network hierarchies and circulation of goods, people, and information through a religio-social penal code that equally applies to all members. One is judged and sentenced for committing one of “the seven actions,” according to Jean-Jacques Leophin:

1 Ambition—excessive material advancement at the obvious expense of family and dependents.

2 Displaying lack of respect for one’s fellows.

3 Denigrating the Bizango society.

4 Stealing another man’s woman.

5 Spreading loose talk that slanders and affects the well-being of others.

6 Harming members of one’s family.

7 Land Issues—any action that unjustly keeps another from working the land (356).

Davis investigates the case of Clairvius Narcisse, the first medically documented zombie pronounced dead by Western physicians, precisely because Narcisse committed all the actions on the list, and was promptly sold by his family to the society for execution and resurrection. Zombification emerges as a punishment for transgression against a network, and a method of preserving the network’s closure.

Davis’s scientific gaze is simultaneously innocent and invasive, classifying Bizango powders and customs for analysis, the results of which are published in the text itself. His experience with native informants is well informed by his disciplinary knowledge of anthropology, recognizing immediately when locals’ posturing was an attempt to hide actual network material agents—powders and spells—from the ethnographer. “Though Marcel and his followers had a reputation for selling the powders, it had been immediately apparent to me that the preparation he had made me was fraudulent.” (p. 120). On another level, Davis also considers that the mystique of the religion is not simply a tourist front designed to capitalize on the expectations of foreigners; Davis “thanked him [Marcel] profusely and paid him the substantial sum I had promised, plus a sizeable bonus. I left his honfour certain that he knew how to make the zombie poison. I was equally convinced that what he had made me was worthless.” (p. 74). The anthropologist considers that Marcel’s posturing actually hides material technologies of resistance capital used as counterpower from the “medical gaze” of the Western scientist. Conrad (1992) reveals the medical gaze’s power-knowledge-effects on the medicalization of society and its regulators in relation to Foucault (1977). Modern forms of documenting the information gleaned from the natural subject—medical surveillance, as it were—becomes a “form of medical social control” wherein “certain conditions or behaviors become perceived through a ‘medical gaze’ and that physician may legitimately lay claim to all activities concerning the condition.” (p. 216). Conrad (1975) has also identified “medical technologies” as one of three key fields of mapping and controlling medical deviance through processes of medicalization and de-medicalization. These disciplinary discourses also function in the neoliberal moment as the medical scientist’s equivalent of Deleuzian territorialization and de-territorialization of medical knowledge (i.e., “medicalization” and “de-medicalization” of a practice). In pursuit of the zombification powders and recipes, Davis’s disciplined observations and interpretations de-territorialize the zombie’s function as a cultural mechanism and a technology of rural Haitian counterpower, and re-territorialize the knowledge of these substances and their social circulation as pharmaceutical instruments serving the established medical disciplinary body of knowledge.

Discussion

For centuries, American culture has represented Haiti as a failed state, corrupted from within the Afro-Caribbean government, even without foreign intervention. American artists drawing upon the sensibilities of the occupation period were less kind in their portrayals than Davis; White Zombie (1932) and The Black Republic (1884) represent just two examples of the American films and texts about voudoun sorcerers, their automaton armies of spellbound zombies and the cannibalistic rituals (mentioned 97 times in The Black Republic) transplanted from Africa to Haiti via the Maroon movement and secret societies. Max Beauvoir, an intellectual and houngan, disputes these perceptions with one of the most summative assessments of Haiti contained in The Serpent and the Rainbow:

From the outside Haiti may appear to be like any other forlorn child of the Third World struggling hopelessly to become a modern Western nation. But, as you have seen, this is just a veneer. In the belly of the nation there is something else going on. Clairvius Narcisse was not made a zombie by some random, criminal act. He told you he was judged. He spoke about the masters of the land. Here he did not lie. They exist, and they are the ones you must seek, for your answers will only be found in the councils of the secret society (116).

Davis also dispels the Western myths about Haiti, but attempts in doing so to replace cultural and racial mysticism with a kind of scientific certainty, tied up neatly with the data from his notes and his tape recorder. The Bizango at one point in a ceremony notice the piece of incriminating technology as a threat to the de-centrality of their network. “Now my tape became the center of concern,” Davis writes, as a Bizango president asks the rhetorical question: “Are our words meant to pass beyond the walls of this room?” (p. 347). To retain its rhizomatic structure as a resistance network, the Bizango presidents maintain closure through their confiscation of the tape, which would have functioned as a technology of power over the network, as a packaging device for information that could prove fruitful for Western disciplines.

Davis detracts from the secrecy of the Bizango’s network as representative of a multinational biomedical economy. He cannot escape his associations with the tape and the centralization of knowledge that it represents. Networks themselves do not have agency, but rather contain pretext (often in a form of power) for agency to utilize. Advantageous nodal structures and assemblages in a network garner the highest amount of power. Similarly, the Foucauldian panoptic model of Discipline and Punish (1977) demonstrates power through distributed control over subjects through evaluation, incorporation, and centralized observation. This power is not concentrated in any administrator, executioner, or sovereign; rather, it is inherent to the physical and psychological architecture of the prison, the hospital, the factory, etc. Via centralization of networks of knowledge, such as industrial production management or psychiatric evaluation (which bring observational bits together under a “central gaze”), the professional of a “discipline” can capitalize on the potential energy of an organization through the node/s of a network deemed most crucial. These critical systemic points of understanding in a given specialty—i.e., the observation tower of the prison, evidence-based medical experimentation, school grading hierarchies—can be identified and utilized by the disciplined eye to partition, integrate, territorialize, or de-territorialize components of a knowledge schema, organizing it in such a way that it can be acted upon to the agent’s benefit. Architectural power-knowledge is the relation between Foucault’s panopticism and the modern threat to the Haitian network of secret resistance represented in Davis and the tape recorder: the codification of generative connections, the packaging and cataloging of variations at nodes of power under a central gaze. The Bizango president is not fooled by the claim that the tape belongs to Jean Baptiste, recognizing the threat in Davis’s technology. “If the blanc comes to my place, he is welcome to record the voudoun part, and he may learn the songs of the Cannibal, but the words must remain ours. The songs are public, but the words are private” (Davis, 2010, p. 351).

While mapping the society for understanding is useful, if not ethically precarious, for Western understanding of Haitian resistance, Davis is also careful in helping to rethink top-down portrayal of decolonized societies, using networks to illustrate elements of power operating for the benefit of African American cultures, rather than denouncing their issues stemming from a colonial subjugation, an American occupation, and a series of mythical dictators. Davis’s use of networking theory has become a key component of ethnographic methodology in the modern social sciences and literary analysis, but his work also presents a shift toward a more thoughtful appreciation of the ways in which societies are able to maintain, protect, and improve upon themselves without the paternal guidance of cultural imperialism.

In sum, three distinct themes emerge from the findings in relation to the methods and framework presented in the literature:

Theme 1: the role of brokerage in Haitian religious networks

Davis’s network is transnational, bridging American academic circles and Haitian religious communities. His ability to connect with highly specialized sources in medical and anthropological fields influences his trajectory in Haiti. Key brokers include Dr. Nathan S. Kline, Marcel Pierre, and Max Beauvoir, who facilitate Davis’s access to secret societies. As an outsider, Davis relies on these intermediaries to navigate the clandestine world of voudoun.

Brokerage plays a dual role in maintaining secrecy and enabling knowledge exchange. While Haitian religious leaders exercise caution, Davis leverages his Western institutional connections to acquire valuable ethnographic data. The tension between network inclusion and exclusion underscores the protective mechanisms employed by secret societies to guard their traditions.

Theme 2: closure and the protection of secret societies

The Bizango and other secret societies in Haiti function through strategic closure. Membership is tightly regulated, and outsiders are rarely permitted full access. Marcel Pierre and Jean Baptiste exemplify figures who mediate between secrecy and exposure, operating within and against the societal boundaries that voudoun leaders establish.

Davis’s presence disrupts these networks, raising concerns about cultural appropriation and exploitation. The confiscation of his tape recorder during a Bizango ceremony symbolizes resistance to Western surveillance and the scientific gaze. Closure, in this context, serves as a method of cultural preservation, ensuring that sacred knowledge remains protected from external commodification.

Theme 3: programming and switching as forms of network resistance

Manuel Castells identifies network-making power as the ability to program and switch networks based on dominant actors’ interests. In The Serpent and the Rainbow, Papa Doc Duvalier exemplifies a network programmer who integrates voudoun into his authoritarian regime. By aligning himself with secret societies, he consolidates power through fear and mystical authority.

Conversely, subaltern groups utilize switching to resist centralized control. The Bizango network, despite its secrecy, adapts to shifting political landscapes, maintaining influence through grassroots governance. Davis’s research reveals how secret societies function as alternative structures of power, challenging both local and foreign interventions in Haiti.

Conclusion

Davis’s The Serpent and the Rainbow offers a compelling case study in networked resistance, illustrating how Haitian religious societies navigate and subvert structures of power. By restructuring the study of voudoun through network theory, this paper highlights the interplay between brokerage, closure, switching, and programming in maintaining cultural sovereignty. The tensions between inclusion and exclusion, visibility and secrecy, reflect broader postcolonial struggles for autonomy. Davis’s work, while innovative, raises ethical questions about the role of Western scholars in documenting and interpreting indigenous networks. Understanding these dynamics through network theory provides a framework for analyzing resistance in other postcolonial contexts, reinforcing the significance of decentralized power structures in shaping historical and contemporary societies.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MR: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fhumd.2025.1394002/full#supplementary-material

References

Beal, W. (2012). The form and politics of networks in Jean Toomer's cane. Am. Lit. Hist. 24, 658–679. doi: 10.1093/alh/ajs043

Conrad, P. (1975). The Discovery of Hyperkinesis: Notes on the Medicalization of Deviant Behavior. Social Problems, 23, 12–21. doi: 10.2307/799624

Deleuze, G., and Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Galloway, A. R., and Thacker, E. (2007). The exploit: a theory of networks. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Hurston, Z. N. (1990). Tell my horse: voodoo and life in Haiti and Jamaica. New York: Harper Collins.

Huxley, J. (1966). A discussion on ritualization of behaviour in animals and man. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 251, 249–271.

Jameson, F. (1988). “Cognitive Mapping.” in Marxism & the Interpretation of Culture, eds. C. Nelson and L. Grossberg. Urbana: U. of Illinois Press, 347–60.

Leyburn, J. G. (1941). The Haitian people. Lawrence, KA: Institute of Haitian Studies, University of Kansas.

Massumi, B. (1987). “Notes on the translation and acknowledgments” in Deleuze and Guattari, a thousand plateaus, xvii–xx.

Keywords: network graph analysis, digital humanities, postcolonial (theory), Haiti, anthropology, literary analysis

Citation: Rischard M (2025) Magical pow(d)ers: the resistance capital of subaltern networks in Wade Davis’s the Serpent and the Rainbow. Front. Hum. Dyn. 7:1394002. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2025.1394002

Edited by:

Nirmala Menon, Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), IndiaReviewed by:

T. Shanmugapriya, Indian Institute of Technology Dhanbad, IndiaTerrence Musanga, Midlands State University, Zimbabwe

Copyright © 2025 Rischard. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mattius Rischard, bWF0dGl1cy5yaXNjaGFyZEBtc3VuLmVkdQ==

Mattius Rischard

Mattius Rischard