- Institute of International Relations (IIR), China Foreign Affairs University, Beijing, China

In 2018, a bilateral memorandum of understanding (MoU) was signed by the state authorities of Nepal and Malaysia. Although stringent state regulations have affected the ability of intermediaries to facilitate the movement of migrant workers, this paper highlights the complex practices of various intermediaries along the corridor. A key point in the MoU was the commitment to eliminating migration costs—referred to as “zero cost migration”—and establishing a safe migration pathway that adheres to the International Labour Organisation (ILO) guidelines. However, this study demonstrated that while state policies designed to reflect global norms aimed at reducing exploitative practices in labor migration are well-intentioned, they have inadvertently led to new forms of inequality among migrant workers. This study employed a qualitative methodology, drawing on recent fieldwork conducted from September to December 2024, including semi-structured interviews and participation observations along the Nepal-Malaysia corridor. It analyses data from 40 stakeholder interviews, policy documents and previous migration research projects conducted between 2019 and 2023.

Introduction

Nepal has a large working population seeking migration for foreign employment, particularly to Gulf countries and Malaysia, as its economic lifeline relies heavily on remittances. However, Nepali migrant workers have historically faced exploitation, including debt bondage, contract breaches and hazardous working conditions. These outcomes are the results of the processes that regulate the recruitment and placement of Nepali migrant workers, which have come under scrutiny due to persistent issues of corruption, exploitation and poor governance.1 As a significant labor-receiving country, Malaysia was particularly urged to address issues such as forced labor, human trafficking and unfair recruitment practices. Furthermore, the core labor provisions of the multilateral trade agreement, of which Malaysia was also a part, required member countries to uphold and enforce safe, orderly and regular migration pathways and to reform recruitment practices in countries according to the International Labor Organization (ILO) standards.

In recent decades, national policy reforms, including Malaysia's 2017 amendment to the Private Employment Agencies Act (Act 246)2 and Nepal's 2019 revision of the Foreign Employment Act (Act 26),3 have aimed to align with the International Labor Organization (ILO) standards. Central to these legislative reforms was the adoption of principles such as the zero-cost migration model and employer-paid recruitment principle (EPP). For example, more than 200 outsourcing companies in Malaysia were investigated under the new act for elements of forced labor (Albert Kassim, 2014; Rahim et al., 2015). These policy shifts were further reinforced by the 2018 bilateral labor pact between the two countries (The Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal The Federation of Malaysia, 2018).4 After the government's decision in Nepal, it prohibited its citizens from being hired in Malaysia.

State policies in the corridor and diplomatic measures that align with the ILO conventions and principally aim to reduce exploitative practices are well-intentioned. Nonetheless, their actual implementation has produced mixed outcomes. This study examines the extent to which the ILO frameworks have shaped the development and reform of recruitment and employment legislation in both Nepal and Malaysia. In other words, it searches for answers to the following research questions:

• Whether and how the ILO standards have shaped the recruitment policies. Specifically, it focuses on the fact that Nepal has not fully adopted the Employment Service Convention 1948 (C88) compared to Malaysia, although both countries have not formally signed the Private Employment Agencies Convention 1997 (C181).

• The degree to which these compliances are reflected in the role of intermediaries or “middle space actors” in implementing responsible recruitment practices along the migration corridor.

• The rationale behind state actions and the factors encouraging or limiting the adoption of these standards.

It highlights the role of middle space actors—government bodies, private recruiters and non-state actors—in mediating compliance, enforcement and labor rights outcomes. This research aims to fill a gap in the existing literature by focusing not only on legal frameworks but also on the lived realities and informal mechanisms that shape the labor recruitment process from Nepal to Malaysia.

A brief overview of the recruitment sector in the Nepal–Malaysia corridor

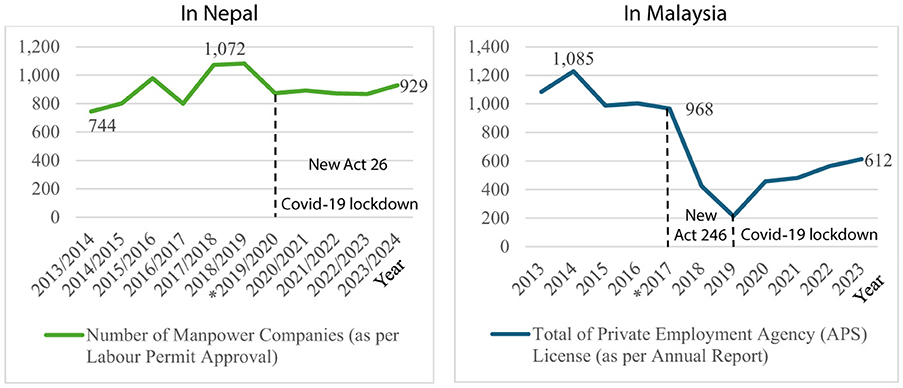

The private recruitment industry and associated recruitment sectors that connect Nepal and Malaysia mainly focus on providing Nepali workers with blue-collar jobs in factories and service sectors, as well as positions such as security guards (Kaur, 2012; Ahmad and Khor, 2024b). This corridor plays a significant role in providing employment opportunities to many Nepalese people and contributing to the economies of both countries. Figure 1 provides a clear overview of the trends in the number of Nepalese manpower companies and Malaysian private employment agencies (PEAs) from 2013 to 2023. This information is crucial as it sets the context for the subsequent discussion on the impact of regulatory changes on the recruitment sector and the post-pandemic situation in both countries. For example, in Japan, the placement service industry increased significantly after the state ratified C181 in 1999 (Seyedi and Darroudi, 2021).

Figure 1. Overview of Nepalese manpower companies and Malaysian private employment agencies. *After the amendment year and the post-pandemic period from 2020 to 2021. Source: Compiled by the author. Annual reports from Nepal's Department of Foreign Employment (Department of Foreign Employment (DoFE), 2020, 2022; Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security (MoLESS), 2015, 2016, 2018, 2021, 2024) and Malaysia's Department of Labour (Department of Labour (JTK) Peninsular Malaysia, 2018a, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017b, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024).

Before the amendment in 2017/2018 [Department of Foreign Employment (DoFE), 2018, 2019], 1,072 licensed manpower companies were operating in Nepal, sending approximately 27% of the 323,876 Nepali migrant workers to Malaysia alone. As of July 2023/2024 [Department of Foreign Employment (DoFE), 2025], the Department of Foreign Employment (DoFE) recorded 929 licensed companies conducting foreign employment operations and sending to Malaysia approximately 23% of the 353,163 Nepali migrant workers. In Malaysia, the number of licensed private placement agencies authorized by the Department of Labor (JTK) decreased to 612 in 2023 from 1,085 in 2013. In 2013, Nepali foreign laborers accounted for approximately 17% of the 2.3 million migrant population, and they remained the third largest group within the 2.3 million migrant workforce at 17% in 2024 (Ahmad and Khor, 2024a).

After the enforcement of Act 246 in July 2018, there was a trend of declining private placement agencies in Malaysia. In contrast, the number of manpower companies operating in Nepal remained high even after the revision of Act 26 in 2019. In addition to Malaysia, Nepal sends migrant workers to around 142 countries, with the highest number being sent to Gulf states such as Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and UAE. Economic development in Nepal is highly dependent on the money that Nepali workers remit back. This indirectly becomes the driving force behind the operation of manpower companies in Nepal.

During the COVID-19 lockdown from 2020 to 2021, the borders of both countries were closed, resulting in a halt to cross-border recruitment activities, with only domestic hiring campaigns allowed in Malaysia. To address the sudden rise in unemployment during the pandemic, the Ministry of Human Resources (MoHR) in Malaysia provided APS with job placement incentives. APS was entitled to RM600 per Malaysian candidate for each job matching with companies (SME Association of Malaysia, 2020; Lee, 2022). After the pandemic, the situation for Nepali migrant workers became increasingly desperate when the borders reopened from the end of 2022 until March 2023. However, on 18 March 2023 and again on 21 October 2024, the Malaysian government implemented a notice to freeze the quota for migrant workers to address the status of migrant workers in the country. This directive remains in effect as of the time of writing.

The discussion is divided into three parts, concluding with recommendations and further scope for similar research. The article begins by reviewing significant literature from several scholars in the field of international relations who have explored the role of IOs in promoting international standards among member states. This section outlines the liberal perspective as the theoretical framework for understanding IOs (Krasner, 1982), distinguishing it from other migration studies focusing on topics such as citizenship, integration, and diasporas. Next, the key findings from the corridor are examined to identify the similarities and differences in the policies of private recruitment agencies in Malaysia and Nepal. The selection of this corridor supports the discussion on whether international agencies such as the ILO are able or limited in influencing national legislation without legally binding conventions or treaties.

Literature review of the influence of international conventions on domestic labor recruitment frameworks

International conventions play a pivotal role in shaping the regulatory frameworks for domestic labor recruitment, even when they are not legally binding. These conventions often serve as guiding principles, setting norms and standards that influence national policies and practices. The process through which these conventions exert influence is multifaceted. This section explores how these conventions impact domestic labor recruitment frameworks, drawing on existing scholarly insights from various contexts and highlighting the remaining gaps.

International conventions often take the form of quasi-legal instruments or soft law, which include non-legal adoption agreements, declarations and guidelines. Despite their non-legal adoption, these instruments can have a profound impact on domestic policies. According to Jones (2022), for instance, the International Labor Organization's (ILO) Fair Recruitment Initiative (FRI) has been non-legally instrumental in promoting fair recruitment practices globally. Similarly, the ILO's Decent Work for Domestic Workers Convention, 2011 (No. 189), has influenced domestic laws and policies, even in countries that have not formally signed the convention (Boris and Undén, 2017; Fish and Shumpert, 2017; Jones, 2021).

Non-binding approaches are particularly effective because they provide flexibility and encourage gradual compliance. In Chetail's article on the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM) (Chetail, 2023), the GCM operates as a soft law instrument, offering a collaborative framework for migration governance. Similarly, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) guidelines (Parsa et al., 2023), the Recruitment Advisor (RA) platform (Recruitment Advisor, 2017), and the IRIS ethical recruitment certification (International Organization for Migration (IOM), 2016a) have influenced corporate reporting on labor rights, although they are informally binding.

The conventions discussed have provided a standardizing framework that shapes local laws and campaigns for safe, orderly and regular cross-border foreign recruitment. However, existing frameworks and soft law instruments often lack empirical research on how international labor standards are interpreted and applied in specific countries, particularly when examining migration corridors such as the Nepal–Malaysia route. This study offers a unique opportunity to investigate how non-ratifying states adopt and adapt international norms to shape real-world recruitment practices.

Private employment agencies and employers at the global level are key actors in translating international conventions into domestic policies and implementation forces. The World Association of Public Employment Services (WAPES) Asia-Pacific [Social Security Organisation (SOCSO) and World Association of Public Employment Services (WAPES), 2020], the World Employment Confederation (WEC) (2018), and the International Organization of Employers (IOE) [Malaysian Employers Federation (MEF), 2020], for instance, have lobbied international conventions, such as the drafting of the ILO's Private Employment Agencies Convention (C181). Subsequently, these organizations have deployed the convention as a tool for advocacy, even in countries that have not ratified it.

Additionally, Silva's article showed that international organizations such as the OECD, World Bank and IMF influence labor governance through their policy agendas and transfer mechanisms (Silva, 2023). These organizations often promote specific policy models, such as the flexicurity approach, which has been adopted by various countries (Piper and Foley, 2021).

Nonetheless, existing discussions have primarily focused on high-level actors, including governments, international organizations and regional bodies, while often overlooking the role of intermediary or “middle space” actors. These intermediaries, such as multinational employer federations, global recruitment agencies, brokers, outsourcing companies and even regulatory bodies, play a crucial role in mediating between global norms and local practices (Chen, 2023; Fletcher and Trautrims, 2023; Lee and Sivananthiran, 1996). Their influence in enforcing, reshaping, or resisting international standards remains understudied.

While international conventions have a significant influence on domestic labor recruitment frameworks, there are challenges to their effectiveness and consistency between standards and national laws. One major challenge is the non-binding nature of many conventions (Andrees et al., 2015), which limits their enforceability. For instance, the GCM's non-binding nature has led to disappointing implementation records, as states have not fully committed to its principles (Chetail, 2023). Murphy's article specifically revealed that the ILO's Domestic Workers Convention has faced challenges in implementation due to the precarious immigration status of many migrant domestic workers (Murphy, 2013). Additionally, non-binding bilateral agreements in labor migration have been criticized for their lack of transparency and accountability (Megiddo, 2022).

An in-depth analysis of why and how countries favor implementing certain aspects of international conventions without full ratification is needed. This research contributes by using case studies; the Nepal–Malaysia corridor effectively illustrates the management of recruitment practices. This selective compliance may reflect strategic interests, resource limitations, or political constraints, and the implications of this partial adoption have not been sufficiently studied.

Despite these challenges, some scholars have proposed that the mechanisms of naming and shaming (Greenhill and Reiter, 2022; Zhou et al., 2022), peer review (Jongen, 2021), and NGO's shadow reports (Matelski et al., 2022) play significant parts in encouraging compliance with the ILO international conventions. The first strategy involves publicly naming states for non-compliance, which can pressure them to adhere to international norms. These approaches have been shown to influence state behavior in two situations. When civil society organisations amplify the shaming approach, it has led to improvements in human rights practices, sometimes only temporarily, but it demonstrates the impact of grassroots pressure (Schoner, 2024; Martin and Simmons, 1998). However, the effectiveness of naming and shaming can be limited by government counter-narratives that may mitigate its impact on public opinion (Greenhill and Reiter, 2022; Zhou et al., 2022). In the context of the ILO, naming and shaming through ILS conference sessions and shortlisting has been found to enhance compliance across various issues, although governments may resist reporting on certain social conditions (Koliev and Lebovic, 2021).

On the other hand, peer review mechanisms involve systematic evaluations of one state by other states and are used to promote compliance with international standards. These reviews can foster transparency, apply pressure and facilitate learning among states, as seen in the OECD's anti-corruption efforts (Jongen, 2021). The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) shadow reports by NGOs/CSOs (Li-Ching et al., 2014) and the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of the UN Human Rights Council (Lane, 2022) exemplify how peer reviews can integrate international norms into national contexts. Despite this, their effectiveness can be hampered by political will and capacity issues (Lehne Cerrón, 2024). In the ILO context, peer reviews, naming and shaming and alternative progress reports are part of a broader strategy to uphold labor standards, with global benchmarking serving as a tool to reduce defection from core standards and promote compliance through learning and discursive multilateralism (Weisband, 2000). While these mechanisms have limitations, they remain crucial tools in the international community's efforts to enforce compliance with labor and human rights conventions.

Additionally, bilateral labor supply agreements somehow address globalization's challenges by harmonizing diverse legal frameworks and cross-border employment dynamics (Battistella, 2015; Eneh et al., 2024; Wickramasekara, 2018). This is particularly important in industries with international operations, where compliance with varying labor laws across jurisdictions is essential to avoid legal disputes. However, non-binding bilateral agreements in labor migration have been criticized for their lack of transparency and accountability. For example, there is a lack of effective inspection mechanisms for recruitment practices in Bangladesh (Abdul-Aziz, 2001; Syed, 2023). From the standpoint of the Nepal–Malaysia corridor, inadequate penalties for labor violations have led to widespread non-compliance with labor standards.

The Employment Service Convention 1948 (C88)

One of the landmark conventions discussed in this article is the Employment Service Convention 1948 (C88). In the aftermath of World War II, economies worldwide were rebuilding and employment issues were at the forefront of policy discussions. Therefore, C88 was adopted by the International Labor Conference (ILC) on 9 July 1948. This convention emphasizes the government's role as an intermediary in establishing and maintaining an employment service to assist workers in finding suitable jobs and help employers in securing qualified personnel. The primary purpose of the convention is to establish a national system of public employment services that are provided at no cost.5 Government agencies should provide employment services free of charge to all workers, ensuring accessibility for job seekers regardless of economic status and gender, including minority groups and vulnerable communities.

One important provision of C88 is Article 11.6 This article requires competent government agencies to take necessary measures to ensure effective cooperation between public employment services and private placement agencies that operate without profit motives. The ILO encourages cooperation in the provision of housing facilities, social amenities, and the use of technology within recruitment processes. The goal of this cooperation is to enhance the efficiency of hiring services in the labor market while ensuring that private employment industries complement rather than compete with public services. It is important to note that no section of C88 advocates for the removal of private hiring entities from the labor market. Consequently, C88 has always been promoted alongside C181.

Malaysia adopted C88 in June 1974 among 19 other conventions.7 Unlike Nepal, Malaysia currently enforces C88, which mandates improvements to its hiring system and job-matching processes. Malaysia has submitted six updates to the International Labor Conference (ILC) session, with the most recent being in 2020 regarding a free government hiring service supported by a well-developed network of employment centers.8

The Private Employment Agencies Convention 1997 (C181)

Compared to C88, neither Malaysia nor Nepal are signatories to the Private Employment Agencies Convention (C181). However, both countries have harmonized the principle of C181 into their national legislation, which will be discussed in the next section. The convention concerning hiring defines private recruitment agencies and manpower companies as private entities that act as labor intermediaries. These entities facilitate the connection between job seekers and employers by engaging in activities such as job placement and skills provision. According to Article 1(1) of C181,9 private placement industries include any third-party involvement in the recruitment process, ensuring that workers are matched with appropriate job opportunities while meeting the needs of employers. Under Article 3(1) of the convention,10 each government is required to establish formal conditions for the operation of recruitment agencies through a licensing or certification system. This ensures that private placement agencies function within a regulated framework, adhering to labor laws and national practices. By implementing such a system, the government can monitor and oversee the activities of private employment agencies, ensuring compliance with legal and ethical labor standards. Article 7(1)11 explicitly states that private employment agencies must not impose any fees or costs on workers, whether directly or indirectly, in whole or in part. This provision safeguards workers from financial exploitation and ensures access to employment opportunities without undue financial burden. However, Articles 7(2)12 and 7(3)13 outline certain exceptions, allowing certain fees to be charged under defined circumstances and providing flexibility in implementation.

The Guide to Private Employment Agencies: Regulation, Monitoring and Enforcement (2007) [International Labour Organization (ILO), Special Action Programme to Combat Forced Labour, and (International Labour Organization (ILO), 2007)] emphasizes that private employment agencies (PEAs) and foreign employment agencies (FEAs) are capable of demonstrating the existence of a labor market for the recruitment services they provide. This requirement ensures that agencies operate within a structured and demand-driven framework, preventing the proliferation of unnecessary or unregulated recruitment practices. By verifying market availability, governments and labor authorities can maintain a balanced labor market that aligns with national economic and employment goals. By adhering to these principles, C181 provides a comprehensive governing principle that enhances the functioning of private employment agencies while ensuring the protection of workers' rights and promoting fair labor market practices. The practical implementation of this convention requires continuous oversight, collaboration between the public and private sectors, and a commitment to upholding ethical employment standards on a global scale.

The labor pact between Nepal and Malaysia

In 2019, both governments signed a labor pact aimed at establishing orderly and regular recruitment channels and streamlining safe recruitment procedures in terms of cost (People Forum for Human Rights Nepal, 2021). The bilateral agreement aligns with the principle set forth in C181 (Hassan et al., 2018). The roles and responsibilities of Malaysian private recruitment agencies are defined under the Private Employment Agencies Act. These agencies must comply with the rules and regulations outlined in Act 246, which includes coordination with manpower companies as specified in the Nepalese Foreign Employment Act.

The agreement introduced two pathways for foreign employment (People Forum for Human Rights Nepal, 2021). First, Malaysian employers who also act as intermediaries in the recruitment process are permitted to use the channels of APS to connect with manpower companies to recruit Nepali migrant workers. The recruitment agencies' pathway is designed to ensure flexibility, allowing employers of different capacities to recruit workers for operation and production jobs. Alternatively, Malaysian employers can directly engage with licensed recruitment agencies in Nepal. This second option allows companies in sectors such as the security guard sector, as well as financially strong firms in Malaysia, to conduct the foreign hiring process in-house.

This agreement regulates the associated costs that are the employer's responsibility. At the same time, both countries agreed to charge Nepali migrant workers for other expenses, such as transportation within the home country, meals and accommodation while in Kathmandu. Under the bilateral agreement, Malaysian employers are responsible for paying recruitment fees to manpower companies in Nepal and recruitment costs to private employment agencies in Malaysia. However, the outline of migration costs in the bilateral agreement is viewed differently and often causes confusion among various actors involved in the recruitment process.

“50% of the one-month minimum wage (in Malaysia) of the Nepalis migrant worker to be paid to the manpower companies, e.g.: 50% of RM1,500 (~USD340) about RM750 (USD170)” (MC5 and MC6: owners of manpower companies in Nepal).

“for us (recruitment agencies in Malaysia), we are only allowed to charge one month of migrant workers (including Nepali laborers) of their minimum wages as fees” (all the interviewee agency owners in Malaysia)

“some of them (recruitment agencies in Malaysia or manpower from Nepal) charge us RM1,500, some of my friends had their recruiter bill them separately (RM750 in Malaysia, RM750 in Nepal), and some even charged us RM2,250 (~USD509)” (all the interviewee business owners in Malaysia)

“In total, agencies (Malaysia and Nepal) are allowed to collect RM2,250 (~USD509) as recruitment cost” (GR3: an officer in Malaysian government agencies).

In recent years, the Nepal government has also prioritized a “zero cost” (Low, 2020) or “free visa, free ticket” (Khadka, 2021; Upasana, 2025) hiring campaign for Nepali workers, which aims to reduce the risk of financial burden caused by recruitment fees and other expenses. Later in the agreement, the “employer pays” (Ghimire, 2018) model was established, in which the employers are responsible for all other fees and costs associated with hiring.

Methodology and scope of research

Research examining the role of international organizations (IOs) often employs quantitative methods to sum the number of conventions and treaties signed by countries, comparing these figures between the Asia-Pacific and European regions (Koliev, 2021). For example, according to the ratification data from the Information System on International Labor Standards (Normlex) [International Labour Organization (ILO), 2025], the estimated adoption rate was 21%. Europe has the highest adoption rate of the ILO conventions at 9%, while Arab countries have the lowest at 1%. This study contributes to the existing literature by analyzing domestic policies in relation to C88, which was signed by Malaysia, and C181, which was not signed by either Nepal or Malaysia.

This study adopted a qualitative case study approach. Primary data were collected through 40 semi-structured interviews (20 in Nepal and 20 in Malaysia) conducted between September and December 2024. Interviewees included manpower company owners, government officials, recruitment agency representatives, employers and civil society actors. Interviewees were selected through an existing network of grassroots organisations, recruiters, NGO staff, and government officials in both Nepal and Malaysia established during previous migration research projects conducted between 2019 and 2023 (Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations (CTPSR), 2019). Interviewees consented to provide basic personal information before the interview session. The one-to-one interview session lasted between one and one and a half hours and took place at the interviewee's organization premises, where the author was allowed to tour their facilities.

The interviews were thematically analyzed, and the interview questions included four important themes: recruitment fees and cost structures, licensing and capital requirements, perceptions of bilateral labor agreements and operational challenges and compliance with international norms. Coding categories were developed based on important themes and recurring narratives from stakeholders. The key insights were then compared with relevant policy documents, legal reports and ILO resources.

Regarding the term used in this study, the author defined “middle space” as referring to all types of actors who act as intermediaries or operate within the intermediaries' domain to implement, monitor and facilitate cross-border labor mobility (Jones and Sha, 2020; Jones, 2021). Clearly defining who qualifies as such actors, including government agencies or states, is challenging. If the recommendations from non-governmental and civil society organisations are adopted, suggesting that the government should assume responsibility for cross-border hiring, this could streamline migration processes, reduce reliance on private intermediaries, and transform the government's role from that of a middleman. In the Nepal–Malaysia case study, employers and labor mediators may interchange their roles.

Key findings of the corridor legislation and C88 and C181

Cooperation between states (sending and destination countries), businesses (private sector), and workers under a tripartite principle is essential to ensure that labor is not treated as a commodity due to worker's unfavorable situation (International Labour Conference, 1944). In the case of migrant labor hiring across state borders, private recruitment agencies and related placement industries are considered experts in the hiring process, helping businesses recruit migrant workers from source countries for companies or manufacturing operations in destination countries. This section discusses a few key findings to analyze the dynamics between national legislation (Department of Labour Peninsular Malaysia, 2018b; International Organizations for Migration (IOM), and Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security (MoLESS), 2019) and the ILO conventions (International Labour Organization (ILO), 2007). Both Nepal and Malaysia have employed a capital-based approach as a mechanism of control. The ceiling fee approach was similar in both countries, but its implementation varied. The differing labor markets in Nepal and Malaysia prompted both governments to respond differently in terms of addressing exploitation issues in the corridor and fostering the labor market.

Monetary approach

Article 3(1) of C181 states that government agencies should set up a mechanism for private sector entities that wish to operate a private recruitment business or any related placement industry. As interviewees from both sides expressed, private recruitment services in the corridor are highly regulated with a solid licensing regime and monetary requirements.

“we have to take out a loan with the bank to start our company (recruitment agency) more than other businesses setup, every month we need to repay our loan with interest” (MC1: owner of a manpower company in Nepal).

“I have to put my land, my house, everything (mortgage) with the bank for the loan to set up my manpower and training facilities that requested under the sector (security guards)” (MC2: owner of a manpower company with a security guard training center in Nepal).

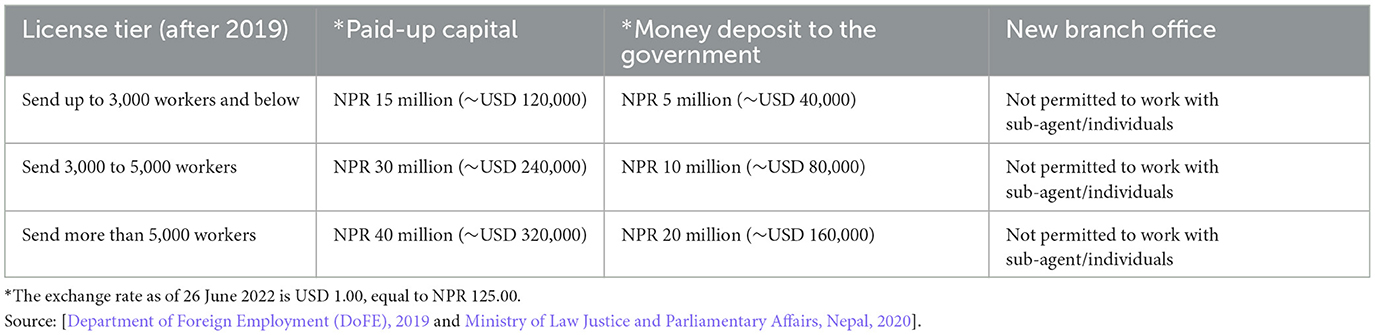

In the corridor, the new provisions include requirements such as a minimum paid-up capital and a money guarantee to be submitted to the related government agencies for establishing private recruitment businesses or any of the related recruitment sectors. In Nepal, prior to the 2019 amendment, private recruitment agencies were required to have a paid-up capital of USD 5,600 and a money guarantee of USD 18,400 (International Organization for Migration (IOM), 2016b; Kapoor, 2020; Kunwar, 2020). As a result, most of Nepal's recruitment agencies operate on a hybrid business model, which may include free visas, free tickets with service fees, zero-fee recruitment with unclear cost structures, or practices where all expenses are ultimately collected from workers. After the 2019 amendment, as shown in Table 1, the Nepalese government increased both requirements by ~54–93% (Five Corridors, 2021). This change has significantly impacted small or informal recruiters, making it more difficult for them to operate legally.

Table 1. The minimum paid-up capital and money guarantee requirements after the 2019 amendment of act 26 in Nepal.

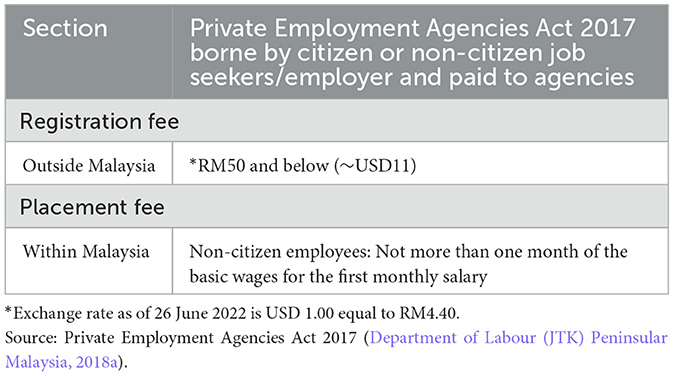

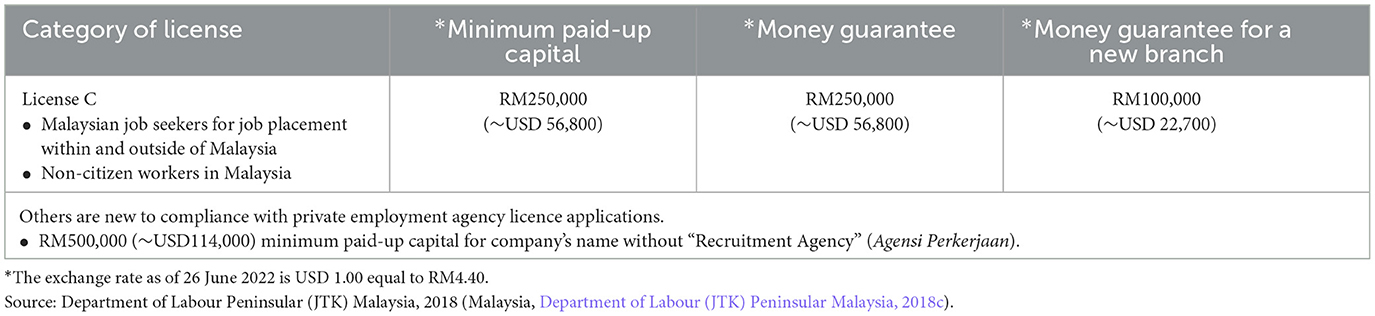

The government of Malaysia reshuffled the private employment industry into three new categories of licenses,14 with the revision of paid-up capital and money guaranteed required by the Ministry of Human Resources (MoHR) (House Representative, 2019b,c). As shown in Table 2, Malaysian private recruitment agencies handling migrant workers' placement fall under Category “C”. Before the 2017 amendment, companies operating recruitment businesses were not required to prove that they had paid-up capital and had deposited a cash guarantee into government coffers.

Table 2. The minimum paid-up capital and money guarantee requirements after the 2017 amendment of act 246 in Malaysia.

The goals of Act 26 and Act 246 amendments are to protect job seekers, including migrant workers, from being exploited (debt bondage) by such agencies and to better regulate recruitment activities within and outside the corridor. Specifically, in Malaysian agencies, these changes are meant to professionalize the sector, but some believe that these regulatory frameworks are difficult.

“our business requirement is very easy compared to others (security guards sector), all we need to do is to submit documents required by the government in Malaysia and manage official paperwork required by the source countries, then our business will not get barred. (APS1: owners of a recruitment agency in Malaysia).

“our industry is very difficult to operate not only money (paid-up capital and money guarantee) but in terms of laws too (labor laws, company regulations, trafficking legislation), visit by officer from time-to-time because our industry not like other business but a company sending someone who are a father, mother, daughter or son to work in other country, we have responsibility for them” (APS7: owners of a recruitment agency in Malaysia).

The money guarantee requirements in Nepal and Malaysia are designed to ensure that any misconduct or industrial complaints against recruitment agencies can result in the government deducting funds as a penalty, in addition to blacklisting the agencies.

Celling fee approach

One of the controversial issues was the charging of fees by manpower companies or private recruitment agencies. The specific article of C181 banned private employment services from charging workers any formal or informal job placement fees or recruitment costs. However, Articles 7 (2) and (3) of the convention provide flexibility for government agencies regarding this no-fee provision, allowing them to make exceptions in certain recruitment fee arrangements.

In 2015, the Nepal government promoted the “free visa, free ticket” policy. It permitted manpower companies to charge a maximum of NPR 10,000 (~USD80) to Nepalese workers migrating for work outside the country. While some migration experts claim that capping recruitment fees is expected to reduce worker exploitation, the reality proves to be the opposite.

“Some manpower claim how to do business under the ten thousand (Nepali rupees), so some agencies only issues a receipt to worker of ten thousand but charging other expenses such as meal and accommodation for staying in Kathmandu” (ON1: research institution in Nepal).

This was reviewed by comparing the money invested to set up the company against the recruitment fees associated with the compliance requirements permitted under the legislation. A manpower company in Nepal believes current standards do not reflect the comprehensive approach of the government's efforts in supporting ethical recruitment practices.

“The group is talking (lobbying) with the government to allow us (manpower companies) to charge the recruitment fees based on one month worker salary and removed the 100 workers standard, as long we send worker ethically we should be given a license” (MC4: owner of a manpower company in Nepal).

Before the amendment, placement fees were never clearly defined and were imposed on migrant workers in Malaysia. Table 3 below shows the new amendment's restricted ceiling fees for placement, which are to be charged to job seekers and migrant workers, in addition to employers. Private employment agencies are allowed to deduct no more than one month of the migrant worker's minimum salary for the first monthly wages under the Second Schedule of Act 246. Basic wages under the law in Malaysia are defined by the wages offered to workers. For Nepali migrant workers in Malaysia, recruitment charges are based on the minimum wage order. The fees increased as the minimum wage rose from RM1,500 (~USD340) to RM1,700 (~USD386). From an industry perspective, as the following interviewee explained, the recruitment costs are not controlled or capped, and the labor memorandum of understanding (MoU) emphasizes that employers bear the recruitment fees.

“these charges (recruitment fees) are expected to adjust every two years, besides taxes, electricity rates (for businesses) that might also increase but not reduce” (EA4: owner of a medium size business in Malaysia).

Both governments permit recruitment fees within the corridor, but they have set different limits on these costs. The Nepalese government has become aware of this situation and is now considering revising this standard. As a result, if the one-month salary standard established in the Nepal–Malaysia corridor is enforced, it could also be applied to other destination countries that demand Nepali workers. The issue of migration in Nepal has sparked a discussion regarding its effectiveness as a means of alleviating poverty for workers, particularly in light of these standards.

Market capabilities approach

The ILO international labor standards obligate governments to ensure clear employer and employee relations. However, the ILO acknowledges that labor intermediaries cannot be ignored in some states or regions due to the variations in labor markets or new markets for recruitment services. Under the 2007 ILO Guide to Private Employment Agencies, a private recruitment service license is meant to be temporary. Both under Act 26 in Nepal and Act 246 in Malaysia, for example, the governments have imposed stricter compliance requirements on the placement industry for license applications and license renewals. However, the monitoring systems in the corridor by both the Nepal and Malaysia governments are different.

In Nepal, manpower companies are required to match a threshold of 100 Nepalese workers with foreign employment annually or for two consecutive years; otherwise, their license will not be renewed (Ghimire, 2021; Kumar Mandal, 2020; Pandey, 2025). Manpower companies in Nepal and placement agencies in Malaysia believe that the government evaluates the practices and capabilities of recruitment services based on the number of workers rather than the quality of the services provided.

“In their opinion (the government of Nepal), if you cannot even send 100 people (for foreign employment), why should you even exist” (MC2: owner of a manpower company in Nepal).

“But if not based on this (100 workers standards or migrant workers headcount), what kind of other standards that can use to determine agency license (to measure agency quality)? (APS2: owner of a recruitment agency in Malaysia).

During the pandemic lockdown, as revealed by the manpower interviewee, recruitment activities stopped because travel between countries was not allowed. Manpower companies had to close temporarily due to the requirement of placing 100 workers, which threatened the revocation of almost all manpower company licenses and pressured agencies into unethical practices to meet quotas.

“the condition under the laws (Foreign Employment Rules) on manpower companies to send at least 100 workers was temporarily on hold now (during pandemic lockdown). However, after the economy or business opens up. The government expect the manpower companies in Kathmandu to fulfill this condition, including the number that accumulated during the Covid lockdown period. For example, if, within this year, I have to send out 100 workers, I have to also send with another 100 from last year (2022) and 100 from the previous year (2021) for foreign employment, or my agency license will be suspended. So, the government suggested the merger of two manpower companies for the industry to fulfill 100 workers condition” (MC5: owner of a manpower company in Nepal).

In contrast, the Merit Points System (MPS) (Five Corridors, 2021; Department of Labour (JTK) Peninsular Malaysia, 2017a) was introduced by the government to monitor the placement activities of local workers carried out by private employment agencies. According to the regulations under Act 246 in Malaysia, recruitment agencies were previously required to obtain a minimum of 120 merit points over a two-year period as part of the license renewal standards. These points included two main components. First, each APS license holder must attend courses or workshops organized by the Department of Labor. Each participation earns points, and a minimum of 20 points is required. The second component of the merit system is annual job matching. In this system, different job matching categories earn different points and also various merits according to Malaysian and non-Malaysian placement. As the following interviewees elaborated, integrated monitoring mechanisms should prioritize responsible practices and worker protections, rather than focusing solely on numbers.

“Our agency license is renewed based on documents such as audited company financial statement, annual placement report (number of Malaysian workers and foreign workers facilitated for companies) two months before the license expiry date” (APS2 and APS5: owners of recruitment agency in Malaysia).

“We will conduct go-to-see (often unannounced visits) to all these agencies or offices before approval given, we will also talk (randomly and assessment) to the workers who are working in the agencies about the operation of the companies. (GR3: an officer in Malaysian government agencies).

For instance, each migrant worker placement in a job category other than professionals, managers, executives, or technicians—as defined by the Malaysia Standard Classification of Occupations (MASCO)— earns 0.5 points, compared to 1 point for each Malaysian placement (Department of Labour Peninsular Malaysia, 2018b). Therefore, License “C” private employment agencies will be renewed if they manage to match Malaysian employers with 160 migrant workers for two consecutive years. However, placement agencies highlighted that the MPS is temporarily on hold to support the industry's operations, especially in the aftermath of the lockdown.

“In order to support business and the industry (private employment sector), the government stop on the merits requirement (without any specific period), but I think the government need to incentive the industry more if they want recruitment compliance to ethical standards (higher compliance than the regular national legislation)” (APS6: owners of recruitment agency in Malaysia).

Migrant worker levy and associated taxation approaches

Levies and associated taxes are other regulatory approaches used by many countries, including Malaysia and Nepal, to manage the employment of migrant workers while balancing economic growth and supporting social security contributions and local workforce priorities. Nepal is primarily a labor-exporting country. The government regulates outbound migration through fees and mandatory Foreign Employment Welfare Fund contributions. Under Rule No. 24 of the Foreign Employment Rules, Nepalese workers are obligated to contribute NPR 1,500 (~USD12) for three years of foreign employment deals or NPR 2,500 (USD20) for foreign employment contracts exceeding three years. This amount was also increased from the previous NPR 1,000 (USD10) before the amendment and does not require an employment contract period. In addition to remittances from the population, pre-departure charges help support social security and welfare programs for migrant families back home. Welfare funds have been allocated to support the families of migrant workers who have died abroad and to provide health assistance to returnee migrant workers who were injured or became ill while working abroad.

In contrast, the government of Malaysia imposes levies and security bonds to control heavy foreign labor reliance, which vary by industry and nationality. As of recent updates, the levy for manufacturing and construction workers and in the services sector is set at RM1,850 per year, while for plantation and agriculture workers, it is lower, at RM640 per year, due to labor shortages in that sector. The security bond for each Nepali migrant worker hired by a Malaysian employer is set at RM750. The levy method is expected to be replaced with a multi-tier levy rate based on dependency. However, this change has been postponed temporarily and several times after considering the impact of the pandemic on industries. In October 2024, the government of Malaysia reinstated foreign laborers back into the national social welfare, from which they had been exempted since April 1993. Later in October 2025, migrant workers and Malaysian employers are expected to contribute to the Malaysian retirement scheme, with each paying two per cent of their portions as per the proposal from the Malaysian Employer Association.15 This ruling will be enforced only on employers with RM5, while migrant workers will have the choice to opt in (Social Wellbeing Research Centre (SWRC), 2022).16 Although reinstating foreign employees working in Malaysia into the social security protection and retirement fund is not linked to the conventions discussed in this paper, the Malaysian government's decision to reinstate compliance is in line with other ILO conventions that Malaysia has signed and ratified (House Representative, 2019a).

Discussion: why the states did not fully enforce C88 and did not formally adopt C181

In this section, the author discusses the rationale behind the Nepal–Malaysia corridor's adoption of the ILO convention norms in its national legislation. However, the corridor has chosen not to become signatories to the conventions C88 and C181. First, as Baccini and Koenig-Archibugi (2010) argue, states calculate the risk and benefit factors when deciding to embrace, instead of formally adopting, the ILO conventions. Formally adopting any IOs or ILO conventions subjects states to demanding monitoring mechanisms and reporting systems. This fundamental assessment obligation puts governments at risk of public naming and shaming, as well as sanction by other countries. Therefore, the corridor governments decided to revise Act 26 in 2019, and the legislation changed in 2017 based on C181 and engagement with the respective ILO representative in the country.

States always prefer an open-door policy when adopting IOs or ILO conventions and treaties. For example, some states reserve specific clauses in the conventions and treaties. The justification for such reservations is typically associated with the practical realities on the ground, as state capabilities vary. This may work in one region but not in another due to differences in economic achievement and the social and cultural aspects of each state (Haworth et al., 2005; Geddes, 2021; Ruhs, 2015; Sakai, 2022). This is reflected in the formal adoption rate of C181, which is high among European countries but remains low in Southeast Asia. Furthermore, the drafting of C181 in 1997 was missing the representative voices of private recruitment agencies from South and Southeast Asia, as claimed by the recruiters in the corridor.

“We are not aware of it (in Malaysia or in Nepal); who did they (international organization representatives) talk to on the matter (fair or ethical recruitment adoption)?” (MC4: owner of a manpower company in Nepal).

“none of representatives from these organizations (ILO or IOM) come to us or want to speak with us, not even once (to understand the practical issues from the ground level), we think why will this even matter to us when we already followed the government rules (both Malaysia and source countries like Indonesia, the Philippines) and practice to recruit ethically” (APS5: owner of recruitment agency in Malaysia)

Next, Koliev et al. (Koliev and Lebovic, 2018; Koliev, 2019, 2021) stated that improving national legislation will always require answering the question of best practices and how they are recognized as standards to which law and practice can refer. Similar to other IOs, the ILO constantly works to provide states with best practices and guidance for improving policies, legislation and bilateral agreements between countries. Either Nepal or Malaysia would require political will to become signatories of C181 and resources, such as budget allocations, to fully implement C88 (Lehne Cerrón, 2024).

In the state power argument (Barnett and Finnemore, 1999; Koser, 2010), the state uses capital to control businesses, making it harder for specific individuals or organizations to enter the recruitment market and allowing the state to collect levies as part of its border management strategy (Devadason and Meng, 2013; Devadason, 2020). These approaches are seen as states responding and addressing issues of exploitation and abuse of migrant workers. There are two primary outcomes: First, the state allows labor markets to remain open and liberal while also seeking sectors to assist in addressing issues of unemployment in the country and labor shortage in industries. Second, capital and levies can act as a way to push out recruitment businesses that do not meet standards by increasing competition within the sector.

Conclusion

International conventions significantly influence the regulatory frameworks for domestic labor recruitment, even when they are not legally binding. These conventions operate through soft approaches such as law mechanisms, policy transfer and the mobilization of international private employment agencies and employers. While there are challenges to their effectiveness in the case of the Nepal–Malaysia corridor, such as the non-binding nature of many instruments and inconsistencies between international and national laws, there are also opportunities for enhancing their impact by linking labor standards to trade agreements and strengthening enforcement mechanisms. For example, Malaysia's review of domestic labor recruitment frameworks was influenced by a multilateral trade agreement led by the United States. This created substantial incentives for Malaysia to comply with international labor standards (Hassan et al., 2018).

Another approach is strengthening the enforcement mechanisms of soft law instruments, such as bilateral agreements on labor recruitment, to ensure greater accountability and transparency (Parsa et al., 2023). The labor pact in the corridor is an alternative to formal convention adoption measures in the corridor. Both governments in the corridor signed the labor pact to streamline recruitment procedures and establish legal recruitment channels. Next, both countries have regulated the fees that can be imposed on Nepali migrant workers. However, the interpretation and role of private recruitment agencies in the Nepal–Malaysia corridor remained open to debate, as they were still defined according to the Foreign Employment Act of 2019 and the Private Employment Agencies Act of 2017. More holistic criteria include complaint records, service feedback or evaluation and availability of an ethical code of conduct; these are some suggestions for license renewal instead of headcount targets.

Lastly, more robust implementation within the government agencies is required in Malaysia and Nepal. For example, transparency about the performance of private recruitment agencies operating within Malaysia and the offshore labor market. The statistics in Figure 1 show a declining number of private recruitment agencies since the act was amended, and the reason behind this remains unclear. Both authorities in the corridor did not conduct regularization of all private placement services before the acts were amended or during the transition period. Therefore, no investigations or prosecutions were conducted against private recruitment agencies that might have been involved in abuse cases and the exploitation of migrant workers (Paoletti et al., 2014).

To improve how states handle migration, it is essential to understand the actors who influence, change, or challenge policies from within. Recognizing the realities of these “middle spaces” is key to promoting fair recruitment across borders. This study specifically examines the migration corridor between Nepal and Malaysia, focusing mainly on private recruitment processes. Future research should consider broader regional comparisons and gender perspectives. At the same time, the perspectives of migrant workers and migration intermediaries are discussed in a different article published in 2024.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they contain sensitive personal information about the interviewees. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants for whom this was feasible; for individuals where written consent was not practical or appropriate (e.g., due to literacy barriers or cultural preferences etc), verbal informed consent was obtained, documented through detailed notes of the consent process (including confirmation of understanding, voluntariness, and agreement to publication of potentially identifiable data/image) and witnessed by a third party to ensure accountability. In all cases, participants were fully informed of the purpose of the research, how their data/image would be used in publication, their right to withdraw at any stage. Their autonomy and confidentiality have been prioritized throughout.

Author contributions

YK: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^In 2018, a news report titled “Kleptocrats of Kathmandu and Kuala Lumpur” revealed that high-ranking politicians and former officials were involved in embezzling over RM185.6 million (Rs5 billion) from more than 600,000 Nepali workers between September 2013 and April 2018. The scandal scam began when the former Home Affairs Minister in Malaysia awarded work visa applications to private recruitment services Ultra Kirana Sdn Bhd and Bestinet Sdn Bhd, which required Nepalese workers to apply for Malaysian work visas through a Kathmandu-based private recruitment agency, Malaysia VLN Nepal Pte Ltd. This scandal raises concerns about the transparency of operations conducted by private recruitment agencies in the labor recruitment process (Sapkota Lumpur, 2018).

2. ^In 2017, the Malaysia Private Employment Agencies Act 1981 (Act 246), which regulates employment agencies, underwent amendments to comply with the requirements set by a trade agreement. One of the core labor provisions in the trade agreement required member countries to uphold and enforce labor rights according to International Labour Organization (ILO) standards (Department of Labour (JTK) Peninsular Malaysia, 2018c).

3. ^Nepal's Foreign Employment Act 1985 (Act 26) was also amended to limit the number of manpower companies operating in the country during the pandemic lockdown in 2019. This decision aimed to curb fraudulent recruitment practices, improve the quality of services provided by employment agencies, and ensure better regulation of labor migration. Act 26 was initially introduced to regulate the placement of Nepalese workers for foreign employment (Kumar Mandal, 2020; Ministry of Law Justice and Parliamentary Affairs, Nepal, 2020).

4. ^In May 2018, the government of Nepal imposed a ban on its citizens being recruited in Malaysia after a preliminary investigation revealed the involvement of corrupt officials from both countries and private recruitment agencies charging excessive fees to Nepali workers. Following the 14th General Election in Malaysia, the former Human Resource Minister pledged to resolve these issues and conducted a series of diplomatic negotiations with the government of Nepal. As a result, in October 2018, both countries signed a labor pact related to the employment of Nepali migrant workers, which came into effect in September 2019. The Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal and The Federation of Malaysia, Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of Nepal and the Government of Malaysia on the Recruitment, Employment, and Repatriation of Workers (Unpublished, 2018).

5. ^Article 1 of the Employment Service Convention, 1948 (No. 88) [International Labour Organization (ILO), 1997a].

6. ^Article 11 of the Employment Service Convention, 1948 (No. 88).

The competent authorities shall take the necessary measures to secure effective co-operation between the public employment service and private employment agencies not conducted with a view to profit [International Labour Organization (ILO), 1997a].

7. ^Ratifications for Malaysia [International Labour Organization (ILO), 1997a].

8. ^Direct Request (CEACR) - adopted 2020, published 109th ILC session (2021), Employment Service Convention, 1948 (No. 88) - Malaysia (Ratification: 1974).

9. ^Article 1.

1. For the purpose of this Convention the term private employment agency means any natural or legal person, independent of the public authorities, which provides one or more of the following labor market services:

(a) services for matching offers of and applications for employment, without the private employment agency becoming a party to the employment relationships which may arise therefrom;

(b) services consisting of employing workers with a view to making them available to a third party, who may be a natural or legal person (referred to below as a “user enterprise”) which assigns their tasks and supervises the execution of these tasks;

(c) other services relating to job seeking, determined by the competent authority after consulting the most representative employers and workers organizations, such as the provision of information, that do not set out to match specific offers of and applications for employment [International Labour Organization (ILO), 1997b].

10. ^Article 3.

1. The legal status of private employment agencies shall be determined in accordance with national law and practice, and after consulting the most representative organizations of employers and workers.

2. A Member shall determine the conditions governing the operation of private employment agencies in accordance with a system of licensing or certification, except where they are otherwise regulated or determined by appropriate national law and practice. [International Labour Organization (ILO), 1997b].

11. ^Article 7.

1. Private employment agencies shall not charge directly or indirectly, in whole or in part, any fees or costs to workers [International Labour Organization (ILO), 1997b].

12. ^Article 7.

2. In the interest of the workers concerned, and after consulting the most representative organizations of employers and workers, the competent authority may authorize exceptions to the provisions of paragraph 1 above in respect of certain categories of workers, as well as specified types of services provided by private employment agencies [International Labour Organization (ILO), 1997b].

13. ^Article 7.

3. A Member which has authorized exceptions under paragraph 2 above shall, in its reports under article 22 of the Constitution of the International Labour Organization, provide information on such exceptions and give the reasons therefor.

14. ^The three types of categories. ‘A' category license requires a sum of money RM50,000; RM100,000 for Category ‘B' and RM250,000 for Category ‘C'.

15. ^Associated Chinese Chambers of Commerce and Industry of Malaysia (ACCCIM) (Associated Chinese Chambers of Commerce and Industry of Malaysia (ACCCIM), 2024; House of Representatives, 2025), “ACCCIM Press Statement on the Proposed Inclusion of All Non-Citizen Workers in the EPF Contribution,” ACCCIM Publication, Acccim.my (ACCCIM, October 21, 2024), https://www.acccim.my/press-releases/acccim-press-statement-on-the-proposed-inclusion-of-all-non-citizen-workers-in-the-epf-contribution/.

16. ^Social Wellbeing Research Centre (SWRC), “Spearheading Social Protection Initiatives for All,” Protect, Promote and Prevent, October 2022, https://swrc.um.edu.my/images/SWRC/DOKUMEN%20PDF/SWRC%20BULLETIN/SWRC%20Social%20Protection%20Bulletin%20Vol.%202%20No.%204%20October%202022.pdf.

References

Abdul-Aziz, A. R. (2001). Bangladeshi migrant workers in Malaysia's construction sector. Asia-Pacific Populat. J. 16, 3–22. doi: 10.18356/e085943a-en

Ahmad, N., and Khor, Y. (2024a). “Remittances as the practice of care: a case study on Nepali migrants in Malaysia,” in MIDEQ. Coventry: Coventry University. Available online at: https://southsouth.contentfiles.net/media/documents/FINAL_Remittances_as_the_Practice_of_Care-A_Case_Study_on_the_Nepali_Migrants__aMfXz8K.pdf (Accessed March 9, 2025).

Ahmad, N., and Khor, Y. (2024b). Transnational practices of care along the Nepal Malaysia remittance corridor. Migration Policy Pract. 8, 47–54. Available online at: https://publications.iom.int/books/migration-policy-practice-volume-xiii-number-3-december-2024

Albert Kassim, S. S. (2014). Isu Pengambilan Pekerja Asing: Tekam Minta Status Quo Dikembalikan. Available online at: https://www.mstar.com.my/lokal/semasa/2014/10/16/kuota-tekam (Accessed March 10, 2025).

Andrees, B., Nasri, A., and Swiniarski, P. (2015). Regulating Labour Recruitment to Prevent Human Trafficking and to Foster Fair Migration: Models, Challenges and Opportunities. Geneva: International Labour Office. Available online at: https://www.fairrecruitmenthub.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/wcms_377813.pdf (Accessed March 9, 2025).

Associated Chinese Chambers of Commerce and Industry of Malaysia (ACCCIM) (2024). ACCCIM Press Statement on the Proposed Inclusion of All Non-Citizen Workers in the EPF Contribution. Available online at: https://www.acccim.my/press-releases/acccim-press-statement-on-the-proposed-inclusion-of-all-non-citizen-workers-in-the-epf-contribution/ (Accessed March 10, 2025).

Baccini, L., and Koenig-Archibugi, M. (2010). Why do states commit to international labor standards? The importance of ‘rivalry' and ‘friendship.”' In SSRN Electronic Journal. London: London School of Economics. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2135054

Barnett, M. N., and Finnemore, M. (1999). The politics, power, and pathologies of international organizations. Int. Organiz. 53, 699–732. doi: 10.1162/002081899551048

Battistella, G. (2015). Labour Migration in Asia and the Role of Bilateral Migration Agreements. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9781137352217_12

Boris, E., and Undén, M. (2017). “The intimate knows no boundaries: global circuits of domestic worker organizing,” in Gender, Migration, and the Work of Care, eds. S. Michel and I. Peng (Cham: Springer Nature), 245–68. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-55086-2_11

Centre for Trust Peace and Social Relations (CTPSR). (2019). Nepal-Malaysia Corridor. Migration for Diversity and Equality (MIDEQ). Coventry: Coventry University. Available online at: https://www.mideq.org/en/migration-corridors/nepal-malaysia/ (Accessed March 10, 2025).

Chen, Y. (2023). The international regulatory framework for labor protection of multinational enterprises. Highlights Business Econ. Managem. 16, 492–99. doi: 10.54097/hbem.v16i.10618

Chetail, V. (2023). The politics of soft law: progress and pitfall of the global compact for safe, orderly, and regular migration. Front. Human Dynam. 5:1243774. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2023.1243774

Department of Foreign Employment (DoFE) Nepal. (2018). Annual Report Labour Approval Permit for 2016-2017. Kathmandu: Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security (MoLESS). Available online at: https://dofe.gov.np/yearly.aspx

Department of Foreign Employment (DoFE) Nepal. (2019). Annual Report Labour Approval Permit for 2017-2018. Kathmandu: Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security (MoLESS). Available online at: https://dofe.gov.np/yearly.aspx

Department of Foreign Employment (DoFE) Nepal. (2020). Annual Report Labour Approval Permit for 2018-2019. Kathmandu: Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security (MoLESS). Available online at: https://dofe.gov.np/yearly.aspx

Department of Foreign Employment (DoFE) Nepal. (2022). Annual Report Labour Approval Permit for 2021-2022. Kathmandu: Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security (MoLESS). Available online at: https://dofe.gov.np/yearly.aspx

Department of Foreign Employment (DoFE) Nepal. (2025). Annual Report Labour Approval Permit for 2023-2024. Kathmandu: Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security (MoLESS). Available online at: https://dofe.gov.np/yearly.aspx

Department of Labour (JTK) Peninsular Malaysia (2018a). A Directive of the Director General of the Department of Labour under Section 23, Private Employment Agencies Act 1981 [Act 246]. Available online at: https://jtksm.mohr.gov.my/sites/default/files/2023-06/Panduan%20Mengenai%20Peranan%20Agensi%20Pekerjaan%20Swasta.pdf

Department of Labour (JTK) Peninsular Malaysia (2014). Annual Report 2013. Putrajaya: Ministry of Human Resources (MoHR). Available online at: https://jtksm.mohr.gov.my/ms/penerbitan/laporan-tahunan

Department of Labour (JTK) Peninsular Malaysia (2015). Annual Report 2014. Putrajaya: Ministry of Human Resources (MoHR). Available online at: https://jtksm.mohr.gov.my/ms/penerbitan/laporan-tahunan

Department of Labour (JTK) Peninsular Malaysia (2016). Annual Report 2015. Putrajaya: Ministry of Human Resources (MoHR). Available online at: https://jtksm.mohr.gov.my/ms/penerbitan/laporan-tahunan

Department of Labour (JTK) Peninsular Malaysia (2017b). Annual Report 2016. Putrajaya: Ministry of Human Resources (MoHR). Available online at: https://jtksm.mohr.gov.my/ms/penerbitan/laporan-tahunan

Department of Labour (JTK) Peninsular Malaysia (2020). Annual Report 2019. Putrajaya: Ministry of Human Resources (MoHR). Available online at: https://jtksm.mohr.gov.my/ms/penerbitan/laporan-tahunan

Department of Labour (JTK) Peninsular Malaysia (2021). Annual Report 2020. Putrajaya: Ministry of Human Resources (MoHR). Available online at: https://jtksm.mohr.gov.my/ms/penerbitan/laporan-tahunan

Department of Labour (JTK) Peninsular Malaysia (2022). Annual Report 2021. Putrajaya: Ministry of Human Resources (MoHR). Available online at: https://jtksm.mohr.gov.my/ms/penerbitan/laporan-tahunan

Department of Labour (JTK) Peninsular Malaysia (2023). Annual Report 2022. Putrajaya: Ministry of Human Resources (MoHR). Available online at: https://jtksm.mohr.gov.my/ms/penerbitan/laporan-tahunan

Department of Labour (JTK) Peninsular Malaysia (2024). Annual Report 2023. Putrajaya: Ministry of Human Resources (MoHR). Available online at: shttps://jtksm.mohr.gov.my/ms/penerbitan/laporan-tahunan

Department of Labour (JTK) Peninsular Malaysia (2018c). Private Employment Agencies Act 1981 [Act 246]. Available online at: https://jtksm.mohr.gov.my/sites/default/files/2023-03/7.%20Private%20Employment%20Agencies%20Act%201981.pdf (Accessed March 7, 2025).

Department of Labour (JTK) Peninsular Malaysia (2017a). A Guidelines of the Role of Category C License Private Employment Agencies in the Employment Process of Local and Non -Citizen Workers (Including Foreign and Expatriate Domestic Services) (Pandauan Mengenai Perana Agensi Pekerjaan Swasta Kategori Lesen C Dalam Proses Penggajian Pekerja Tempatan Dan Pekerja Bukan Warganegara (Termasuk Perkhidmat Domestik Asing Dan Ekspatriat). Available online at: https://jtksm.mohr.gov.my/sites/default/files/2023-06/Panduan%20Mengenai%20Peranan%20Agensi%20Pekerjaan%20Swasta.pdf

Department of Labour Peninsular Malaysia (2018b). A Guidelines on Licensing Procedures under the Private Employment Agencies Act 1981 [Act 246]. (2018). Available online at: https://jtksm.mohr.gov.my/sites/default/files/2023-06/Garis%20Panduan%20Prosedur%20Perlesenan%20APS.pdf

Devadason, E. S. (2020). Foreign labour policy and employment in manufacturing: the case of Malaysia. J. Contemp. Asia 51, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/00472336.2020.1759675

Devadason, E. S., and Meng, C. W. (2013). Policies and laws regulating migrant workers in Malaysia: a critical appraisal. J. Contemp. Asia 44, 19–35. doi: 10.1080/00472336.2013.826420

Eneh, N. E., Bakare, S. S., Adeniyi, A. O., and Akpuokwe, C. U. (2024). Modern labor law: a review of current trends in employee rights and organizational duties. Int. J. Managem. Entrepreneurs. Res. 6, 540–53. doi: 10.51594/ijmer.v6i3.843

Fish, J. N., and Shumpert, M. (2017). “The grassroots-global dialectic: international policy as an anchor for domestic worker organizing,” in Gender, Migration, and the Work of Care, eds. S. Michel and I. Peng (Cham: Springer Nature), 245–68. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-55086-2_11

Five Corridors (2021). Five Corridors Project on Fair Recruitment–Launch Event–FairSquare. London: Fairsq.org. Available online at: https://fairsq.org/five-corridors-project-on-fair-recruitment-launch-event/ (Accessed March 7, 2025).

Fletcher, D., and Trautrims, A. (2023). Recruitment deception and the organization of labor for exploitation: a policy–theory synthesis. Acad. Managem. Perspect. 38, 43–76. doi: 10.5465/amp.2022.0043

Geddes, A. (2021). “Governing migration beyond the state,” in Governing Migration beyond the State: Europe, North America, South America, and Southeast Asia in a Global Context, eds. A. Geddes (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1–23.

Ghimire, R. (2021). Covid-19 Nepal Pushes Foreign Employment Agencies, Notorious for Cheating, to a Struggle for Existence - OnlineKhabar English News. Available online at: https://english.onlinekhabar.com/covid-19-nepal-pushes-foreign-employment-agencies-notorious-for-cheating-to-a-struggle-for-existence.html (Accessed July 23, 2021).

Ghimire, S. (2018). Malaysian Employers to Bear All Costs for Nepali Worker: MoU. Nepal Republic Media. Available online at: https://www.myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/malaysian-employers-to-bear-all-costs-for-nepali-worker-mou (Accessed March 10, 2025).

Greenhill, B., and Reiter, D. (2022). Naming and shaming, government messaging, and backlash effects: experimental evidence from the convention against torture. J. Human Rights 21, 399–418. doi: 10.1080/14754835.2021.2011710

Hassan, K. H., Razak, M. F. A., Nordin, R., and Abdul Rahim, R. (2018). Malaysia with the trans-pacific partnership agreement: aftermath of the united states withdrawal from the TPPA - WITA. Int. J. Asian Soc. Sci. 8:880. doi: 10.18488/journal.1.2018.810.868.880

Haworth, N., Hughes, S., and Wilkinson, R. (2005). The international labour standards regime: a case study in global regulation. Environm. Plann. 37, 1939–53. doi: 10.1068/a37195

House of Representatives Malaysia. (2019a). Hansard Special Chamber of Parliament (Members of Parliament Kota Kinabalu Constituency October 16, 2019). Kuala Lumpur: Parliament of Malaysia (Unpublished).

House of Representatives Malaysia.. (2025). Hansard of Parliament (Members of Parliament Miri Constituency March 4, 2025). Kuala Lumpur: Parliament of Malaysia. Available online at: https://www.parlimen.gov.my/files/hindex/pdf/DR-04032025.pdf (Accessed April 18, 2025).

House Representative, Malaysia. (2019b). Oral Answer. (Winding up by the Ministry of Human Resource on Policy Level Budget 2020 October 16, 2019). Kuala Lumpur: Parliament of Malaysia. Available online at: https://www.parlimen.gov.my/files/hindex/pdf/DR-18112019.pdf (Accessed November 12, 2024).

House Representative, Malaysia. (2019c). Oral Answer. (Winding up by the Ministry of Human Resource on Committee Level Budget 2020 November 18, 2019). Kuala Lumpur: Parliament of Malaysia. Available online at: https://www.parlimen.gov.my/hansard-dewan-rakyat.html?uweb=dr&arkib=yes (Accessed November 12, 2024).

International Labour Conference and International Labour Office. (1944). Declaration Concerning the Aims and Purposes of the International Labour Organisation. Montreal: ILO. Available online at: https://webapps.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ilo/1944/44B09_10_e_f.pdf (Accessed March 7, 2025).

International Labour Organization (ILO) (2025). Latest Ratifications and Declarations. Available online at: https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/nrmlx_en/f?p=1000:11400 (Accessed March 10, 2025).

International Labour Organization (ILO) (1997a). The Employment Service Convention, 1948 (No. 88). Geneva: ILO. Available online at: https://ilo.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/delivery/41ILO_INST:41ILO_V2/12118777040002676 (Accessed March 7, 2025).

International Labour Organization (ILO) (1997b). The Private Employment Agencies Convention, 1997 (No. 181). Available online at: https://webapps.ilo.org/public/libdoc/conventions/Technical_Conventions/Convention_no._181/181_English/C181_Private_Employment_Agencies_Convention.pdf (Accessed March 7, 2025).

International Labour Organization (ILO) Special Action Programme to Combat Forced Labour, and International Labour Organization. (2007). Skills and Employability Departmen. Guide to Private Employment Agencies: Regulation, Monitoring and Enforcement. Geneva: ILO. Available online at: https://webapps.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ilo/2007/107B09_296_engl.pdf (Accessed March 7, 2025).

International Organization for Migration (IOM) (2016a). International Recruitment Integrity System. Available online at: https://iris.iom.int/ (Accessed March 10, 2025).

International Organization for Migration (IOM) (2016b). Research on the Labour Recruitment Industry between United Arab Emirates, Kerala [India] and Nepal. Abu Dhabi: International Organization for Migration (IOM). Available online at: https://www.iom.int/resources/research-labour-recruitment-industry-between-united-arab-emirates-kerala-india-and-nepal

International Organizations for Migration (IOM) and Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security (MoLESS). (2019). MIgration in Nepal-A Country Profile 2019. Department of Foreign Employment (DoFE). Kathmandu: IOM Nepal. Available online at: https://dofe.gov.np/yearly.aspx

Jones, K. (2021). Brokered discrimination for a fee: the incompatibility of domestic work placement agencies with rights-based global governance of migration. Global Public Policy Governance 1, 300–320. doi: 10.1007/s43508-021-00017-8

Jones, K. (2022). A ‘north star' in governing global labour migration? The ILO and the Fair Recruitment Initiative. Global Social Policy 22:146801812210847. doi: 10.1177/14680181221084792

Jones, K., and Sha, H. (2020). “Mediated migration: a literature review of migration intermediaries,” in MIDEQ Working Paper. London: Coventry University. Available online at: https://southsouth.contentfiles.net/media/documents/MIDEQ_Jones_Sha_2020_Mediated_migration_v3_aXHTWJy.pdf (Accessed March 10, 2025).

Jongen, H. (2021). Peer Review and compliance with international anti-corruption norms: insights from the OECD working group on bribery. Rev. Int. Stud. 47, 1–22. doi: 10.1017/S0260210521000097

Kapoor, A. (2020). Embode Report Release: The Road to Worthy Work and Valuable Labour. Hong Kong: Embode. Available online at: https://www.embode.co/news/report-release-road-worthy-work-and-valuable-labour

Kaur, A. (2012). Labour brokers in migration: understanding historical and contemporary transnational migration regimes in Malaya/Malaysia. Int. Rev. Social History 57, 225–52. doi: 10.1017/S0020859012000478

Khadka, U. (2021). A Few Good Agents. Nepali Times. Available online at: https://nepalitimes.com/opinion/a-few-good-agents (Accessed March 9, 2025).

Koliev, F. (2019). Shaming and democracy: explaining inter-state shaming in International Organizations. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 41:019251211985866. doi: 10.1177/0192512119858660

Koliev, F. (2021). Promoting international labour standards: the ILO and national labour regulations. Br. J. Polit. Int. Relat. 24:136914812110275. doi: 10.1177/13691481211027513

Koliev, F., and Lebovic, J. (2021). Shaming into Compliance? Country reporting of convention adherence to the international labour organization. Int. Interact. 48, 258–229. doi: 10.1080/03050629.2021.1983567

Koliev, F., and Lebovic, J. H. (2018). Selecting for shame: the monitoring of workers' rights by the International Labour Organization, 1989 to 2011. Int. Stud. Quart. 62, 437–52. doi: 10.1093/isq/sqy005

Koser, K. (2010). Introduction: International migration and global governance. Global Governance 16, 301–315. doi: 10.1163/19426720-01603001