- 1Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- 2Department of Geography and GIS, Faculty of Arts, Assiut University, Old University Building, Assiut, Egypt

Introduction: Cyberbullying has emerged as a pressing concern among adolescents with the increased use of the internet and social media. This study aims to investigate the prevalence and impact of cyberbullying among adolescents in Assiut Governorate, Egypt, focusing on its relationship with various demographic and psychological factors.

Methods: A total of 3,361 adolescents (580 males and 2,777 females), aged 16 to 21 years, participated in the study. Data were collected using three validated instruments: the Adolescent Cyberbullying Scale, the Bully/Victim Questionnaire, and the Six-Item State Self-esteem Scale. Variables examined included age, gender, professional status, marital status, and self-esteem.

Results: The highest prevalence of cyberbullying was observed among adolescents aged 18–19. There were no statistically significant gender differences. Professional and marital statuses showed a positive correlation with cyberbullying, suggesting increased vulnerability among socially visible individuals. Conversely, self-esteem had a negative correlation with cyberbullying but did not significantly correlate with victimization.

Discussion: The findings emphasize the urgent need for targeted interventions to mitigate cyberbullying. Promoting digital literacy, emotional resilience, and supportive environments in schools and families is crucial. The study provides practical recommendations, including integrating digital literacy programs into school curricula. Future research should further explore psychological mechanisms contributing to cyberbullying.

Introduction

Geographical scope and contextual rationale: Assiut Governorate as a case study

The selection of Assiut Governorate as the study area is driven by its unique socio-cultural and demographic characteristics, offering a critical lens to examine the dynamics of cyberbullying in transitioning societies. Located in Upper Egypt, Assiut serves as a microcosm of the broader challenges faced by adolescents in rural and semi-urban regions of Egypt. The governorate combines rural conservatism with rapid technological adoption, creating a distinctive context for understanding how offline identity negotiations shape online aggression patterns—a gap underexplored in Middle Eastern contexts. With a population density of 1,854 individuals/km2 (CAPMAS, 2022) and an internet penetration rate of 68% among youth aged 15–35 (Ministry of Communications and Information Technology (MCIT), 2023), Assiut exemplifies Egypt’s digital transformation challenges while highlighting the complexities of balancing traditional cultural norms with modern technological influences.

Assiut’s socio-economic disparities, coupled with limited digital literacy and heightened exposure to socio-economic inequalities, contribute to a context where cyberbullying can have particularly acute effects. According to CAPMAS (Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics), the governorate has a youthful population, with a significant proportion aged between 15 and 24 years actively using social media platforms. This demographic aligns with global trends showing that adolescents are the most vulnerable group to cyberbullying. Additionally, the region’s distinct cultural norms—such as strong communal ties and genderrole expectations—interact uniquely with rising internet usage rates, influencing online behaviors and interactions.

The socio-economic context of Assiut plays a critical role in shaping online interactions.

Studies indicate that areas with limited economic resources often experience higher rates of cyberbullying due to factors such as parental neglect, lack of supervision, and restricted access to mental health support (Tippett and Wolke, 2015). Marital and professional statuses are significant demographic factors that can influence an individual’s exposure to cyberbullying. Married individuals, particularly those with higher professional statuses, may experience increased visibility on social media platforms due to their active engagement in professional networks and community activities. This heightened visibility can make them more susceptible to online harassment, as their online presence becomes a target for malicious behavior (Smith A. et al., 2022). Additionally, professionals with higher social status often face higher expectations and scrutiny, which can exacerbate the psychological impact of cyberbullying (Jones, 2001). On the other hand, unmarried individuals or those with lower professional statuses may experience less exposure to cyberbullying due to their limited online presence and social interactions. However, this does not imply immunity, as individuals with lower professional statuses may still face cyberbullying in the form of workplace harassment or social exclusion (Tippett and Wolke, 2015). Previous studies have shown mixed results regarding the relationship between marital/professional status and cyberbullying. For instance, Smith A. et al. (2022) found that married professionals are more likely to experience cyberbullying due to their active online presence, while unmarried individuals with lower professional statuses are less likely to be targeted. However, our study reveals that even individuals with lower professional statuses can be victims of cyberbullying, particularly in the form of workplace harassment or social exclusion. This discrepancy may be attributed to the unique socio-cultural context of Assiut Governorate, where traditional norms and rapid technological adoption intersect, creating a distinct environment for online aggression (Sayed et al., 2020). To further explore the impact of demographic factors on cyberbullying, it is essential to consider how marital and professional statuses interact with other variables, such as self-esteem and social support. For example, individuals with higher self-esteem may be better equipped to cope with cyberbullying, regardless of their marital or professional status (Patchin and Hinduja, 2010). This highlights the need for a holistic approach to understanding cyberbullying, one that considers both individual and contextual factors.

While cultural norms in Assiut emphasize family cohesion and community ties, these same norms can sometimes lead to increased social pressure and isolation for victims of cyberbullying, making them less likely to report their experiences (Sayed et al., 2020). Furthermore, the rapid increase in internet penetration over the past decade has outpaced efforts to educate young people about safe online practices, creating an environment conducive to cyberbullying, especially among adolescents still developing their cognitive and emotional capacities (Kao, 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically reshaped digital interactions, leading to increased reliance on online communication among adolescents. Studies indicate that this shift was accompanied by a significant rise in cyberbullying incidents, as social isolation, prolonged screen time, and heightened emotional distress created an environment conducive to online harassment (Aboujaoude et al., 2021). Research suggests that during remote learning, students were more likely to experience cyber aggression due to the lack of direct social regulation typically present in school settings (Kowalski et al., 2022). This period also highlighted disparities in digital literacy, where individuals with lower technological proficiency faced higher risks of cyber victimization. Addressing these challenges requires integrating digital literacy education into post-pandemic recovery programs to equip adolescents with strategies for safer online engagement (Besenyi et al., 2023).

By focusing on Assiut, this study aims to provide insights into how local socio-cultural factors interact with digital behaviors, contributing to a deeper understanding of the cyberbullying phenomenon within an Egyptian context. This localized perspective not only addresses gaps in the literature but also offers practical implications for designing targeted interventions to mitigate the negative impacts of cyberbullying in similar socio-cultural settings.

Similar to face-to-face communication, where individuals may feel inhibited in interacting with peers, on social media, the same individuals can freely express their views. Moreover, since users can remain anonymous or create fake profiles, they rarely fear of their identities being discovered. Even for those who may have the courage to stand up to bullies in person, the online platform forces adolescents to endure bullying at any time of the day or night. Even when students are browsing the internet for academic purposes, they can become unwilling recipients of harassment in the form of threatening or demeaning emails or negative comments on social media.

The economic status of parents and families has a strong effect on the psychology of children. One reason is that when there is a lack of financial resources in the family, parents find it challenging to bear the expenses of their children’s needs, and this may lead to aggressive behavior from parents may surface (Calvete et al., 2010). This leads to low self-esteem and a high level of aggression in children. Recent studies during the COVID-19 pandemic further highlight the exacerbation of mental health issues like depression and anxiety among adolescents due to socioeconomic stressors (Chen et al., 2020). Thus, a common scenario is that children from a negative family environment, with factors such as low financial status, lack of parental care and warmth, or parental negligence, may become either perpetrators of online harassment or victims of cyberbullying.

In general, cyberbullying is primarily associated with adolescents. One in every four younger teenagers experiences cyberbullying (Pichel et al., 2021a,b). Kowalski et al. (2014) assert that cyberbullying is most common between 12 and 15 years of age and the rate of victimization tends to rise during late adolescence. However, Pichel et al. (2021a,b) state that cyberbullying peaks at ages 14 and 15 before decreasing in the latter years of adolescence.

In general, cyberbullying is a recent concern compared to traditional bullying. Hence, although most researchers have focused on the psychological and demographic factors associated with online bullying, there is still a dearth of literature concerning remedial policies.

It is not always possible to deny online access to today’s young population considering the academic benefits that may be derived from the internet. Hence, it becomes the responsibility of parents to monitor the online behavior of their children.

Unlike traditional bullying that takes place in schools and among peers, cyberbullying takes place in the digital realm. As stated by UNICEF, “cyberbullying can take place on social media, messaging platforms, gaming platforms and mobile phones. It is repeated behavior, aimed at intended to scare, anger, or shame those who are targeted” (UNICEF, 2021). The widespread availability of the internet and easy access to social media sites has given young people a platform to express their ideas and share views. For students, social media and the internet in general can be convenient sources of educational information. However, this modern form of communication can also foster harmful behavior in the form of cyberbullying. Cyberbullying manifests in various forms, including threats, spreading rumors about a person, verbal attacks and mocking, posting indecent or embarrassing photos and hacking accounts or creating fake profiles in another person’s name and sending negative, abusive, or threatening messages or emails on that person’s behalf. It can also involve excluding someone from online groups. Although adolescents may engage in traditional bullying in schools and among peers, they increasingly utilize online platforms, particularly social media, to harass others (Li, 2007). Traditional bullying and cyberbullying often coexist, but research indicates that traditional bullies are more likely to engage in cyberbullying than vice versa (Müller et al., 2018).

The issue of cyberbullying has increasingly become a matter of global concern, particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the global lockdown, people, especially younger populations, spent an average of 20 percent more time online compared to pre-pandemic levels (Statista, 2020). According to Security Organization (2022), 21 percent of adolescents aged 10 to 18 reported experiencing cyberbullying, with 56 percent of these incidents occurring between January and July 2020, during the peak lockdown period worldwide. Increased screen time on mobile devices and computers was associated with a rise in cyberbullying cases. Cyberbullying has become increasingly prevalent in the United States, as evidenced by a Pew Research Center survey revealing that 59 percent of U.S. teens have personally experienced at least one type of abusive online behavior (Anderson, 2018). A phenomenon known as “happy slapping” has gained popularity in European countries. This involves recording individuals, often from marginalized groups, using cell phones and subsequently harassing them by sharing the recordings on social media platforms (Mann, 2009). The current study examines several variables that lead young people to engage in abusive behavior online, particularly on social media platforms. A fundamental distinction exists between traditional bullying in schools or among peers and cyberbullying. In the case of cyberbullying, perpetrators can evade negative consequences or punishment due to the anonymity afforded by digital environments. Consequently, the psychological profiles of adolescents who engage in traditional bullying may differ from those of cyberbullies (Calvete et al., 2010). Indirect forms of violence, such as cyberbullying, are frequently directed at individuals perceived as different from the perpetrator. Many young people who engage in cyberbullying exhibit signs of low self-esteem and depression (Calvete et al., 2010). Such psychological issues often stem from their domestic environment. Children who witness parental conflict or experience neglect at home may channel their frustration toward weaker peers, either in school settings or online.

Any form of bullying, whether traditional or online, can lead to psychological issues in children, resulting in poor academic performance. Therefore, preventive measures must consider that children subjected to any form of bullying may, in a way, be deprived of their fundamental right to education. Additionally, there are some key differences between face-to-face bullying and cyberbullying. In the case of traditional bullying, the physical presence or aggressive demeanor of the perpetrator plays a significant role. On the other hand, as previously mentioned, cyberbullying perpetrators can continue their harmful actions without fear of being caught due to the anonymity provided online. Lastly, a critical distinction lies in accessibility: individuals cannot engage in online bullying if they are denied internet access, whereas face-to-face bullying often involves greater levels of humiliation and deprivation (Barlett et al., 2021).

This study seeks to address significant gaps in understanding the dynamics of cyberbullying within the Egyptian context, with a particular focus on Assiut Governorate. Previous research has often neglected key factors, including age-specific vulnerabilities, the influence of professional and marital status on exposure to online harassment, and regional variations in gender-based victimization rates. Furthermore, the moderating role of self-esteem in reducing the adverse effects of cyberbullying has not been sufficiently examined. To address these gaps, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: Younger adolescents, both males and females, are more susceptible to cyberbullying compared to older adolescents.

H2: There is a negative correlation between professional status, marital status, and involvement in cyberbullying.

H3: In most governorates across Egypt, males and females experience bullying at similar rates.

H4: Higher self-esteem is negatively associated with both perpetrating cyberbullying and being a victim of it.

Literature review

Research gaps in the literature

Despite the increasing volume of research on cyberbullying, significant gaps persist in understanding its dynamics within Middle Eastern and Egyptian contexts. Existing literature predominantly focuses on Western settings, leaving socio-cultural factors specific to Egypt largely underexplored. In particular, limited attention has been given to how rural and semi-urban settings, such as Assiut Governorate, influence patterns of online aggression. This gap is particularly critical given the distinct socio-cultural and demographic characteristics of Assiut, where differences in rural and urban behaviors, digital access, and educational infrastructure are pronounced.

Additionally, the intersection of professional and marital status with cyberbullying behaviors has been largely overlooked, creating a critical gap in understanding how these variables interact within conservative communities. For instance, professionals and married individuals may possess unique vulnerabilities or coping mechanisms related to cyberbullying that remain unexamined in current literature.

By addressing these gaps, this study contributes to the broader discourse on digital aggression in transitioning societies and underscores the need for further research to explore these understudied areas. This approach ensures a more comprehensive understanding of the socio-cultural factors that shape cyberbullying dynamics in Egypt.

While cyberbullying can be perpetrated by anyone with access to social media, studies have primarily associated young adults with this behavior, as well as its impact on victims. Cho and Yoo (2017) conducted a comparative study of cyberbullying among adolescents, university students, and working adults. They found a positive relationship between cyberbullying acts, victimization, and the number of online friends, with both cyberbullying and victimization increasing as the number of online friends grew. Jones (2001) explained that adolescents tend to emulate the behavior and social attitudes of their peers, both online and offline. Consequently, if their actions—whether positive or negative—receive support from online friends, these adolescent users may become more prone to engaging in cyberbullying. This tendency is further exacerbated by a lack of awareness regarding the negative impacts of such actions, which can lead to the perpetration of cyberbullying without a sense of guilt. While low levels of social support increase the likelihood of cyberbullying among adolescents, high levels of social support from friends can help alleviate stress, a common side effect of cyberbullying (Cho and Yoo, 2017; Olenik-Shemesh and Heiman, 2017). Pichel et al. (2021a,b) studied the prevalence of cyberbullying in a sample of adolescents aged 10 to 17 in Spain. They found that the younger group (12–13 years) primarily reported rumors spread about them online, while the middle age group (14–15 years) experienced verbal attacks or online threats. Older adolescents (16–17 years) were more likely to become perpetrators rather than victims.

Recent studies emphasize the growing global focus on cyberbullying in educational settings, analyzing both the scale of the problem and emerging trends. Bibliometric analyses have highlighted gaps in the literature, particularly in understanding the socio-cultural factors influencing cyberbullying behaviors (González-Moreno et al., 2020).

One interesting finding is that there has been an increase in incidents of cyberbullying during the current phase of the COVID-19 pandemic (Barlett et al., 2021). These authors attributed several reasons to this rise in cyberbullying, such as forced school closures and reduced opportunities for socializing with peers. Additionally, psychological factors contribute to bullying behavior in adolescents. Based on 1,871 responses to an online survey, it was found that psychological disorders such as anxiety, depression, and stress have become more prevalent during the pandemic (Grover et al., 2020). This is further supported by Barlett et al. (2021), who found that stress and anxiety increased during the pandemic, and these psychological factors are strong predictors of bullying behavior in adolescents. Studies have shown that individuals who engage in cyberbullying often suffer from depression and heightened levels of anxiety (Kowalski and Limber, 2013). Substance abuse is another factor that increases the likelihood of cyberbullying (Ybarra et al., 2007). Furthermore, bullying tendencies—whether traditional or online—are exacerbated when there is a financial crisis at home (Tippett and Wolke, 2015).

The findings of this study align with emerging research highlighting the impact of the COVID19 pandemic on cyberbullying trends. As adolescents’ online engagement increased, the opportunities for digital harassment also expanded, mirroring global patterns reported in post-pandemic studies (Smith P. K. et al., 2022). The emotional toll of pandemic-related stressors, including isolation and anxiety, may have exacerbated aggressive online behaviors, reinforcing the importance of addressing cyberbullying in the broader context of adolescent mental health. These findings suggest that interventions targeting digital resilience and psychological support should be integrated into educational and policy frameworks to mitigate the long-term effects of pandemic-induced cyber aggression (Lim and Chng, 2023).

The rise in cyberbullying among adolescents is a growing concern because increased access to social media sites has often replaced traditional bullying and other forms of offline aggression. A study involving 1,431 participants aged 12–17 revealed an association between cyberbullying and other forms of violence (Calvete et al., 2010). Unnever (2005) linked cyberbullying to proactive aggression. Hinduja and Patchin (2008) explored the convenience for perpetrators, noting that acts of cyberbullying—such as excluding someone from online groups or sending harassing emails—can be conducted anonymously, enabling harassers to act without fear of being caught. Safaria (2016) addressed this issue and suggested that bullying prevention programs should focus on teaching internet users skills to address online harassers, as anonymity cannot be easily addressed. One significant finding by the authors was that, unlike traditional bullying (e.g., in-person school or peer bullying), cyberbullying is not primarily caused by rejection or non-acceptance by peers. However, Williams and Guerra (2007) presented a contradictory view, arguing that adolescents who perceive peer rejection are more likely to engage in bullying behavior, including cyberbullying on social media, suggesting that social isolation can be a predictive factor.

Given the increasing popularity of social media, today’s young generation spends hours on these platforms. The widespread use of social networking sites has extended bullying from classrooms to the internet. Abaido (2020) studied 200 students in the UAE, of whom 91% confirmed experiencing cyberbullying on platforms like Instagram and Facebook. The impact of cyberbullying deserves greater attention, as Arab youth are particularly vulnerable due to their tendency to endure silently, influenced by social and cultural constraints. Young people subjected to cyberbullying often resort to drastic measures, such as suicide, as seen in many cases in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Abaido (2020) explained that such outcomes arise because youth are overexposed to social media platforms, where victims can be harassed around the clock, leaving them no place to hide. This forces victims to suffer in silence, especially since harassers often remain anonymous, making it difficult to fight back. In Arab societies, this issue is more pronounced, as victims hesitate to share their experiences due to prevailing social and cultural norms. Therefore, the author recommends more proactive measures to support cyberbullying victims.

Being victims of constant bullying on the internet can reduce the victim’s positive perception of social interactions. A cyberbullying victim can begin to believe that same behavior can exist in peer relationships in classrooms. Aizenkot and Kashy-Rosenbaum (2021) have studied a sample of Israeli students to confirm that young people who are harassed in WhatsApp groups begin to cultivate negative perceptions of school environment and a reduced feeling of belonging in the classroom. The outcomes of cyberbullying can be dependent on the degree of response by the cyber victims. Research has shown that college students often respond by blocking or confronting the harasser or else remaining offline to prevent becoming further subjected to harassment (Gahagan et al., 2016). The negative consequences can also be reflective of the level of cyberbullying like the number of harasser online, repetition of harassment or contact with the harasser (Mitchell et al., 2016).

The use of social media and associated online activities has been related with wellbeing of both perpetrators and victims. A study based on adolescents aged between 11 and 18 years revealed that social media can be threat to wellbeing as well as platform for cyberbullying. Here, wellbeing is defined as absence of physical or mental problems as well as experience of satisfaction (Giumetti and Kowalski, 2022). Peluchette et al. (2015) have studied the kinds of posts in the social media that lead to cyberbullying victimization. Negative postings like using abusive language and making negative comments can increase experience of cyberbullying. The time spent on social media and the number of friends on Facebook has also been associated with cyberbullying (Kokkinos and Saripanidis, 2017). A study conducted in Korea by Park et al. (2014) has found that adolescents who spend longer hours in social media sites are more inclined to become both perpetrators and victims of cyberbullying. Social media acts as platform where anonymity can be maintained while hurling abuses or threats to other social media users through comments and emails. According to Amanda Giordano who is associate professor in the UGA Mary Frances Early College of Education, “You have these adolescents who are still in the midst of cognitive development, but we are giving them technology that has a worldwide audience and then expecting them to make good choices” (Kao, 2021). The association of social media addiction and cyberbullying has also been confirmed by Giordano et al. (2021). This study was conducted on 428 adolescents between the age 13 and 19 years among whom 214 were female participants and 210 were male participants. However, some studies defy the idea that increased use of social media can cause cyberbullying (Müller et al., 2018). Consequently, a significant point has been noted by the authors. Traditional bullying, i.e., bullying on school grounds is more predictable than online bullying and the assumed reason is that behavioral pattern is more stable online. Further, it is indicated there is more probability of traditional bullies resorting to cyberbullying than vice versa. Hence, cyberbullying is a more situational phenomenon instead of a stable behavioral pattern.

While the use of social media can increase acts of cyberbullying, it is also seen that young users who experience bullying can turn into perpetrators. There is a positive association between perpetrators and victims, for instance cyber victims can develop tendencies to become cyberbullies and vice versa (Balakrishnan, 2015). There is a major difference that lies between victims of traditional bullying like school or peer bullying. In traditional bullying, victims often do not have the courage to fight back but this is not the case for victims of cyberbullying. When these victims receive threatening or abusive emails or comments on social media, they can do the same with the perpetrators or with others. Hence, Balakrishnan (2015) have stated that such outcome is important to consider when implementing prevention programs in dealing with cyberbullying issues. The author has also found that females are more prone to become cyber victims and also they are more inclined to engage in cyberbullying activities than their male counterparts. However, this finding has been contradicted by Wang et al. (2009) and Li (2017) who have found that male social media users are more perpetrators of cyberbullying than female users. On the other hand, Balakrishnan’s finding has been supported by a study conducted in Sweden by Beckman et al. (2013) which reveals that female adolescent cyberbully more than their male counterparts. Studies have also considered age as a predictive factor for both cyberbullying and cyber victims. Didden et al. (2009) and Patchin and Hinduja (2010) have found that older students are less prone to cyberbullying and less cyber victims compared to younger students.

Major studies have also been conducted to study the mechanisms behind cyberbullying activities. Loneliness stemming from social isolation is a strong predictive factor for both cyberbullying and cyber victim. Here, loneliness is often a perception than real as is studied by Cacioppo and Hawkley (2009) who have found that adolescents often suffer from loneliness as a result of perceived social isolation that real physical rejection by peers. Low self-esteem which is a strong predictive factor for victimization of traditional bullying in schools (Ang et al., 2018) has also been studied in the context of cyberbullying. Patchin and Hinduja (2010) have studied 1963 students of mean age 12.6 years from 30 schools to examine the association between low self-esteem and cyberbullying. The study revealed that adolescents who experience cyberbullying both as perpetrators and victims suffer from low self-esteem compared to those adolescents who have never experienced cyberbullying. This is one important factor among the youth since adolescence is a time of identity development. During this phase of life, people look for positive comments that will make them value themselves and avoid negative comments that will make them feel bad. Such attitude helps build the person’s perception of self and guides them toward self-acceptance. Ostrowsky (2010) has observed that adolescents suffering from low self-esteem are more aggressive in nature than their counterparts to gain a sense of superiority over their peers and achieve a higher level of self-esteem. Such aggression pours into their bullying behavior both in schools and in social media sites. Patchin and Hinduja (2010) have suggested that intervention methods should encompass all kinds of bullying both in schools and in cyber space for overall wellbeing of the youth.

The relationship between traditional bullying in schools and cyberbullying has been confirmed by Buelga et al. (2020). The authors have studied two independent samples – 1,318 adolescents comprising 52.6% females and 1,188 adolescents comprising 48.5% males to prove overlapping of traditional bullying and cyberbullying. The study revealed that adolescents who bully others in school or are victims of peer bullying play the same role online. This result was previously affirmed by Lee and Shin (2017) who have established school or peer bullying offline as a strong predictor of cyberbullying. Other studies (Buelga et al., 2015; Garaigordobil et al., 2020) that have supported the same have further corroborated that cyber perpetrators are also involved in antisocial activities. The severity of cyberbullying was studied by Gaete et al. (2021). The authors have considered different forms of bullying both offline and online to conclude that the most severe parameter in victimization is cyberbullying while in perpetration it is sexual bullying. The severe impact of cyberbullying on victims is confirmed as such victims can end up making suicidal attempts (Peng et al., 2019). This is further substantiated by Tan et al. (2018) who have conducted a study in China to reveal that adolescents who are cyber victims or other traditional victims have higher risk of suicidal attempts if they are from rural households compared to their counterparts from urban households. A gender-based finding by Gaete et al. (2021) states that males respond with lower severity both as perpetrator and victim compared to females. Some exceptions have been observed which are that rumors and racial bullying have less impact on females than males.

Nixon (2014) has studied the health and wellbeing of adolescents in the context of cyberbullying. With the popularity of social media, there has been a shift from face-to-face communication to online communication which provides a platform for internet harassment or cyberbullying. It is already seen that mental problems like depression and anxiety can be predictive factor for bullying nature in adolescents (Kowalski and Limber, 2013). The reverse has been established by Nixon (2014). It is seen that adolescents who are victims of cyberbullying exhibit signs of depression, anxiety, loneliness and suicidal tendencies while cyber perpetrators are more inclined to substance use, aggression and delinquent behaviors. The relationship between depression and suicidal ideation with cyberbullying has been further corroborated by using school students as samples by Klomek et al. (2008) and Schneider et al. (2012). The fact that cyber victims can suffer from psychological distress has been established by Safaria (2016). The study was conducted on 102 Indonesian students of seventh grade of which 72 were males and 30 were females. It is learnt that rather than frequency of use of social media it is the online behavioral pattern that decides cyber victimization. This is further affirmed by Kwan and Skoric (2013) and Snell and Englander (2010) who have found that students who use the internet for academic purposes are less vulnerable to cyberbullying than students who use the social media or visit chatrooms. It has so been suggested that parents need to monitor the online activities of students to reduce the risk of the negative impacts of staying online. Contrary to negative impact on wellbeing of cyber victims, it is also seen that there are several positive impacts (Šléglová and Cerna, 2011). Young internet users who have experienced online harassment develop skills of identifying aggressive people. Victims of cyberbullying develop coping strategies like dealing with harassers, avoidance and low social support.

The role of parent–child relationship is important in the context of helping social media users to cope with bullying. Previous studies have revealed the negative psychological effects of cyberbullying both as perpetrator and victim. Zhu et al. (2021) have made a cross-sectional study on 3,000 Chinese high school students of 15 to 17 years to find that parental intervention can reduce the adverse effect of cyberbullying with relation to PTSD and depressive symptoms. These symptoms can further lead to social isolation, low interpersonal skills and low coping capacity resulting in remaining vulnerable to further cyberbullying. Based on attachment theory, Zhu et al. (2021) have found that cyber victims who are closely attached to their parents are less likely to exhibit depressive and PTSD symptoms as compared to those victims who are less attached to their parents. This finding also plays a part in extending the finding that parental intervention can protect adolescents against initial victimization and hence reduce negative effects of victimization. Further, Evans and Cotter (2014) have previously established that trauma from past bullying experiences can fade over time thus ascertaining that attachment between parent and child is not significantly different between lifetime cyberbullying victims and non-victims (Zhu et al., 2021). An additional finding (Lam et al., 2013) states that while social media acts as an ideal platform for online bullying, it is also seen that there are many popular online video games which are programmed to present aggressive and violent environment that increases the risk of cyberbullying victimization. The influence of family on children’s attitude toward their peers is very strong. Parental education is one such factor. One study (Von Marées and Petermann, 2010) has shown that low level of parental education increases the risk of a child becoming a bully or a victim of indirect violence. This risk is higher in males compared to females. One reason behind this can be that parental education affects the standard of life. For instance, low level of parental education is associated with low standard of life while high level of parental education indicates better physical and mental health. Children from families with better standard of life are less prone to become a bully or victim than children from families with low standard of life. It is assumed that low parental education can give rise to other negative factors like family stress and parental conflicts, and these are positively related to indirect violence (Von Rueden et al., 2006). In a similar context, Baldry (2003) have studied 1,059 Italian students to confirm that almost 50 percent of the students were either involved in indirect violence or were victims of indirect violence, and it was seen that the participants (especially females) were more affected by witnessing violence between parents at home than their non-victim counterparts. It was further concluded that parental violence is a more influencing factor on indirect violence than direct child abuse. Since a major factor of parental conflict is low educational level of the parents, therefore it can be said that low parental education is strong indicator of greater risk of child indirect violence such as cyberbullying. In another study, Trickett and McBride-Chang (1995) have found that any kind of maltreatment of children by their parents or other members of their families can have severe negative impact on the development and adjustment in children and this can continue till adulthood. Since maltreatment of children can be both sexual and physical, the authors have observed that children suffering from sexual maltreatment are more likely to remain socially aloof while it is physical maltreatment that can be a causative factor for a child to display signs of aggression that can disturb normal relationship both offline (schools, parks etc.) and online. Any kind of bullying can be emotionally damaging for people of any age, especially adolescents since this particular age group is most conscious about self-value.

Coping strategies play a crucial role in determining how adolescents respond to cyberbullying. Studies have shown that active coping mechanisms, such as seeking social support and reporting incidents, are associated with lower psychological distress (Lim and Chng, 2023). In contrast, avoidance strategies, such as ignoring cyberbullying or withdrawing from online spaces, may increase feelings of isolation and vulnerability. Cultural norms and family dynamics significantly influence which coping strategies adolescents adopt. Future studies should explore how these factors shape coping mechanisms in different socio-cultural contexts.

The role of digital hygiene skills in mitigating the effects of cyberbullying

Digital hygiene skills play a critical role in protecting adolescents from the adverse effects of cyberbullying, yet their importance remains underexplored in existing literature. These skills encompass behaviors and practices that enable individuals to manage their online presence safely and responsibly, such as securing personal information, recognizing malicious content, and utilizing privacy settings effectively (Kao, 2021). Studies have shown that adolescents with higher levels of digital hygiene skills are less likely to become victims or perpetrators of cyberbullying (Giordano et al., 2021). For instance, Giordano et al. (2021) conducted a study on 428 adolescents aged 13–19 years and found a significant association between social media addiction and cyberbullying, emphasizing the need for interventions that promote healthy online habits. Furthermore, research indicates that digital literacy programs can empower young users by enhancing their ability to critically evaluate online interactions and respond appropriately to harmful behavior (González-Moreno et al., 2020). In the context of Assiut Governorate, where rapid technological adoption has outpaced efforts to educate youth about safe online practices (Kao, 2021), fostering digital hygiene skills could serve as an effective preventive strategy against cyberbullying. This aligns with calls for integrating digital literacy into school curricula to equip students with the tools needed to navigate the complexities of the digital age (Rusillo-Magdaleno et al., 2024).

Methodology

Research design

This study employed a cross-sectional design to investigate the impact of cyberbullying on adolescents in Assiut Governorate, Egypt. The research aimed to explore the relationships between demographic, socio-economic, and psychological factors influencing cyberbullying prevalence among adolescents. Cross-sectional studies provide valuable insights into associations between variables, but causality cannot be established due to their observational nature. The relationships observed reflect correlations rather than direct cause-and-effect relationships.

Population and sample

The sample consisted of 3,361 participants (580 males, 2,781 females) aged 16–21 years. Participants were recruited using a snowball sampling method, facilitated through digital questionnaires distributed via Google Forms. This non-probability sampling technique allowed for efficient participant recruitment by leveraging existing social networks. The online survey ensured accessibility to a broad demographic while maintaining anonymity.

Inclusion criteria required participants to be residents of Assiut Governorate, Egypt, and active internet users.

Justification of sample size

The sample size of 3,361 participants was determined based on several factors. First, the population of adolescents aged 16–21 in Assiut Governorate was estimated using data from the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS, 2022). Given the population density and the need for a representative sample, a sample size of over 3,000 was deemed appropriate to ensure statistical power and generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the snowball sampling method was employed to reach a diverse demographic, ensuring that the sample included participants from various socio-economic backgrounds and geographic areas within the governorate. This approach aligns with previous studies on cyberbullying, which have demonstrated that larger samples provide more reliable insights into the prevalence and impact of cyberbullying (Kowalski et al., 2014; Pichel et al., 2021a,b). The sample size was also justified by the need to conduct robust statistical analyses, including structural equation modeling (SEM) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which require larger datasets to ensure model fit and reliability.

Research instruments

Three validated tools were used in this study:

1. Cyberbullying Scale: A comprehensive tool designed to measure both victimization and perpetration of cyberbullying.

2. Bully/Victim Questionnaire: A widely used tool to classify individuals as bullies, victims, or both based on their experiences.

3. Six-Item State Self-Esteem Scale (SSES-6): This scale assessed the participants’ psychological resilience and self-esteem levels.

Validity and reliability of the tools

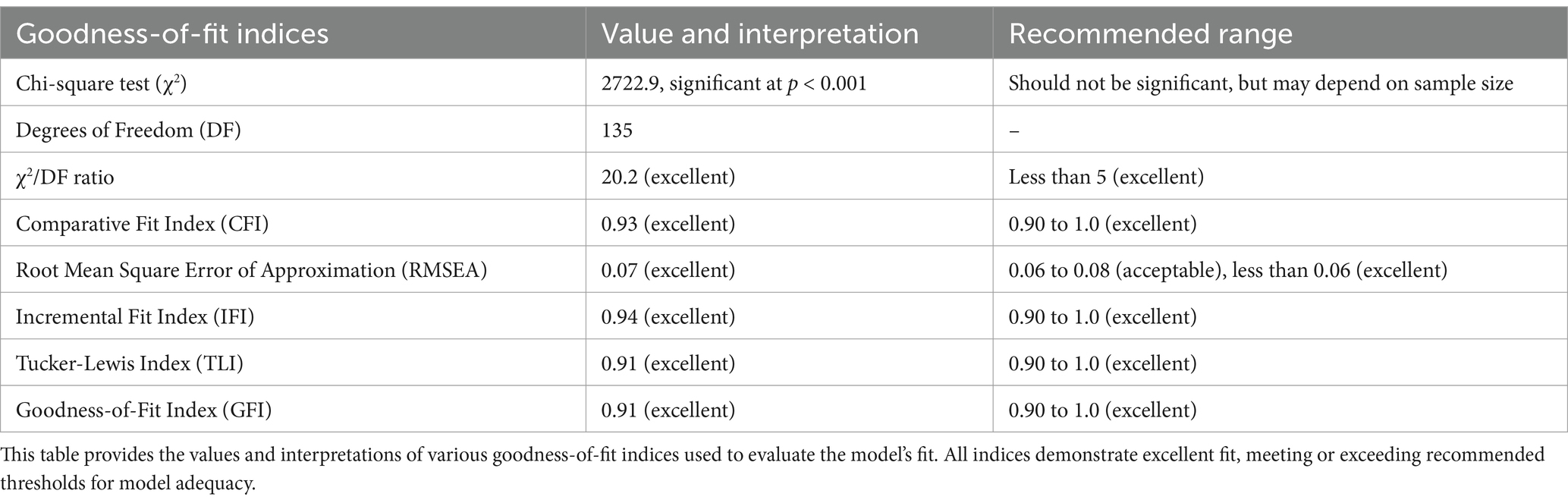

The validity and reliability of the cyberbullying measurement scale were rigorously tested. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) indicated a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value of 0.97, confirming sample adequacy, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was statistically significant (p < 0.001). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) demonstrated strong model fit indices (CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.07). Reliability was established using McDonald’s Omega (ω = 0.94) and split-half reliability (Spearman-Brown corrected value = 0.92), verifying high internal consistency.

Data collection procedure

Data were collected using Google Forms, which allowed for efficient and anonymous participation. The survey was distributed through social networks, schools, and universities in Assiut Governorate. Data collection took place over a period of 2 months, ensuring a sufficient response rate. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study and provided their consent before participating.

Data analysis techniques

Data were analyzed using a combination of software tools:

• SPSS: For descriptive and inferential statistics.

• AMOS: For structural equation modeling (SEM) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

• ArcGIS 10: For spatial data analysis and visualization.

Interpolation techniques, including Kriging, Natural Neighbor, and Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW), were employed to analyze the geographical distribution of cyberbullying incidents.

AI usage in research as documented

Generative AI, specifically ChatGPT (version GPT-4, model GPT-4-turbo by OpenAI), was utilized to assist in refining the manuscript’s title, keywords, and generating discussion points. The AI did not contribute to the substantive research content, data analysis, or interpretation of results. Its role was limited to providing suggestions for improving the clarity and relevance of the manuscript’s structure and content.

Input Prompts Provided to the AI:

1. Summarize the impact of cyberbullying on adolescent mental health.

2. Generate discussion points on resilience and identity formation in youth.

3. Suggest title options for a study on the impact of cyberbullying on adolescents.

4. Suggest keywords relevant to cyberbullying, self-esteem, and adolescents.

AI-Generated Outputs:

1. Summary of Cyberbullying Impact: “Cyberbullying has been shown to affect adolescents’ mental health by increasing levels of anxiety, depression, and social isolation.

2. Discussion Points on Resilience: “Youth resilience is influenced by factors such as strong social support, positive self-esteem, and effective coping mechanisms.

3. Proposed Title: “The Impact of Cyberbullying on Adolescents: Social and Psychological Consequences from a Population Demography Perspective.

4. Suggested Keywords: “Cyberbullying, Adolescents, Psychological Impact, Demography, Social Media.

5. These AI-generated outputs were carefully reviewed and refined by the authors to ensure alignment with the study’s objectives and scope. The final title, keywords, and discussion points used in the manuscript were determined by the authors based on their expertise and the study’s findings.

Ethical considerations

The study adhered to ethical research guidelines. Participants were fully informed about the purpose and significance of the study before providing their consent. They were assured that their participation was voluntary, and they had the right to withdraw at any time without consequences. Their anonymity was strictly maintained, ensuring that personal data would not appear in the study’s results. The research protocol complied with the ethical standards set forth by the Helsinki Declaration regarding informed consent and participant protection. Ethical approval was obtained from the [Institutional Review Board], ensuring that the study met all ethical and procedural standards.

Results

Validity and reliability analysis of the cyberbullying scale

The validity and reliability of the cyberbullying measurement scale were thoroughly evaluated using a combination of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). These analyses ensured the robustness of the instrument used to measure cyberbullying in this study.

Exploratory factor analysis

EFA was conducted to identify the underlying structure of the scale. The results, presented in Appendix 1, reveal factor loadings ranging between 0.60 and 0.83, with a total explained variance of 51.60%. These values indicate a strong construct validity of the scale.

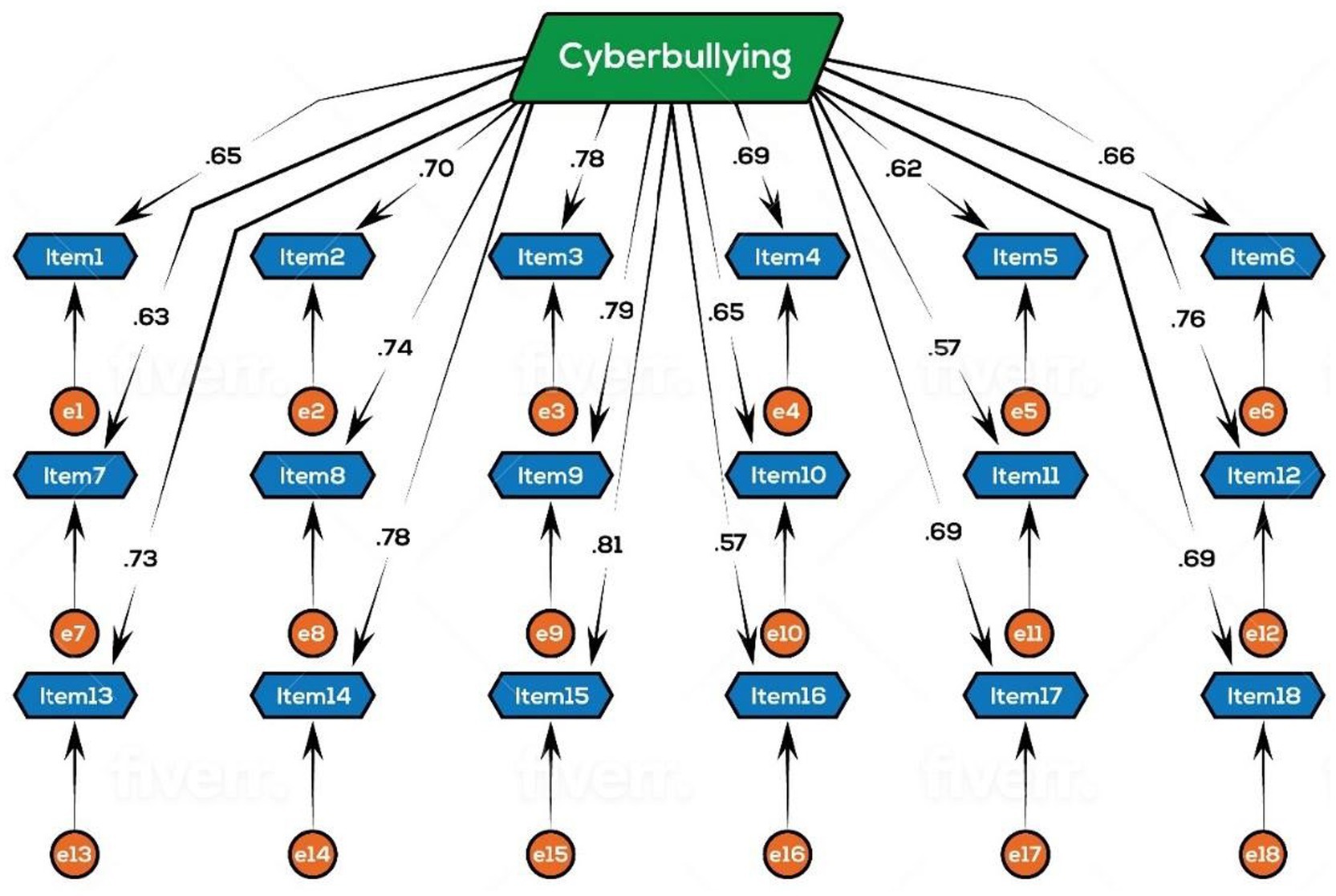

Confirmatory factor analysis

CFA further tested the scale’s structural validity and provided model fit indices that demonstrate the adequacy of the instrument. The results are displayed in Table 1 and are visually summarized in Figure 1 model fit indices (GFI = 0.92, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.07) confirm that the scale meets acceptable standards of model fit.

Figure 1. Path diagram of the cyberbullying scale via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). This diagram illustrates the standardized factor loadings for the cyberbullying scale items, showcasing the relationships between the latent variable (Cyberbullying) and its observed indicators (items 1–18). The loadings represent the strength of associations.

There are no differences in the age groups on the scale of victims of bullying and aggression since the value of P is statistically significant at the significance level (0.001) in cases where p-values are not statistically significant.

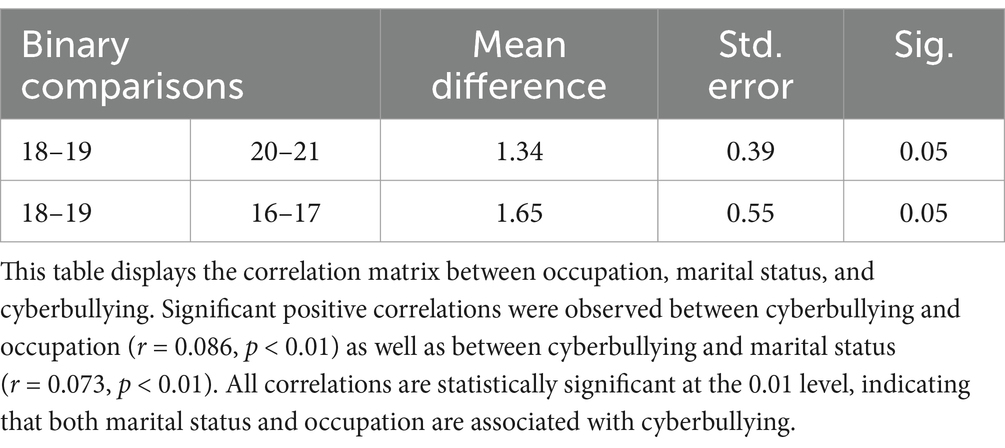

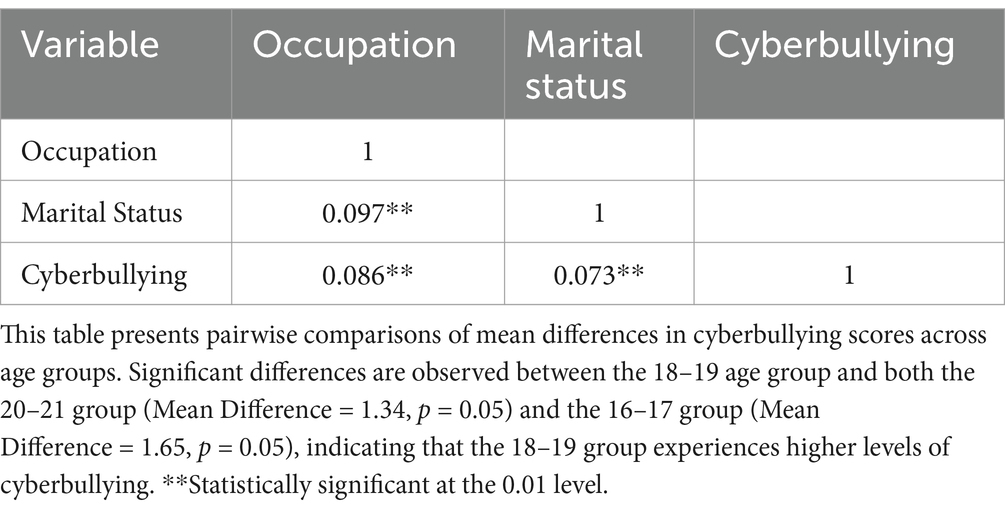

Using the post-hoc test method and the LSD test, it was possible to identify how disparities in cyberbullying among different age groups differed in direction. As a result, the age group 18 to 19 is one of the age groups that is most susceptible to cyberbullying. There are disparities between the age group 18 to 19 and each of the age groups 20 to 21 and 16 to 17 in terms of cyberbullying toward the age group 18 to 19 (Tables 2, 3).

H2: Cyberbullying is related to marital and professional status. This hypothesis was tested with the Pearson correlation coefficient to ensure its accuracy. The correlation coefficients between professional and marital status and cyberbullying were, respectively, 0.097, 0.086, and 0.073. These values are statistically significant at the significance level, indicating that there is a positive correlation between these two factors and cyberbullying (0.01). On the electronic bullying scale, where the value of P was statistically significant at the significance level (0.001), there are differences between age groups (Smith et al., 2006); however, on the bullying and aggressiveness scale, where p-values are not statistically significant, there are no differences between age groups.

The post-hoc analysis and LSD tests were utilized to evaluate the direction of differences in cyberbullying between age groups. As a result, the age group 18 to 19 is one of the age groups that is most susceptible to cyberbullying. There are disparities between the age group 18 to 19 and each of the age groups 20 to 21 and 16 to 17 in terms of cyberbullying toward the age group 18 to 19. Which governorate Marakiz both males and females experienced bullying.

Using a one-way analysis of variance (Vijayvargiya, 2009), it was possible to determine that, while retaining the magnitude of bullying victims, there are disparities between the Marakiz. Additionally, variations between Marakiz were discovered by retaining the aggression scale in cases where the value of P was statistically significant at the significance level (0.01).

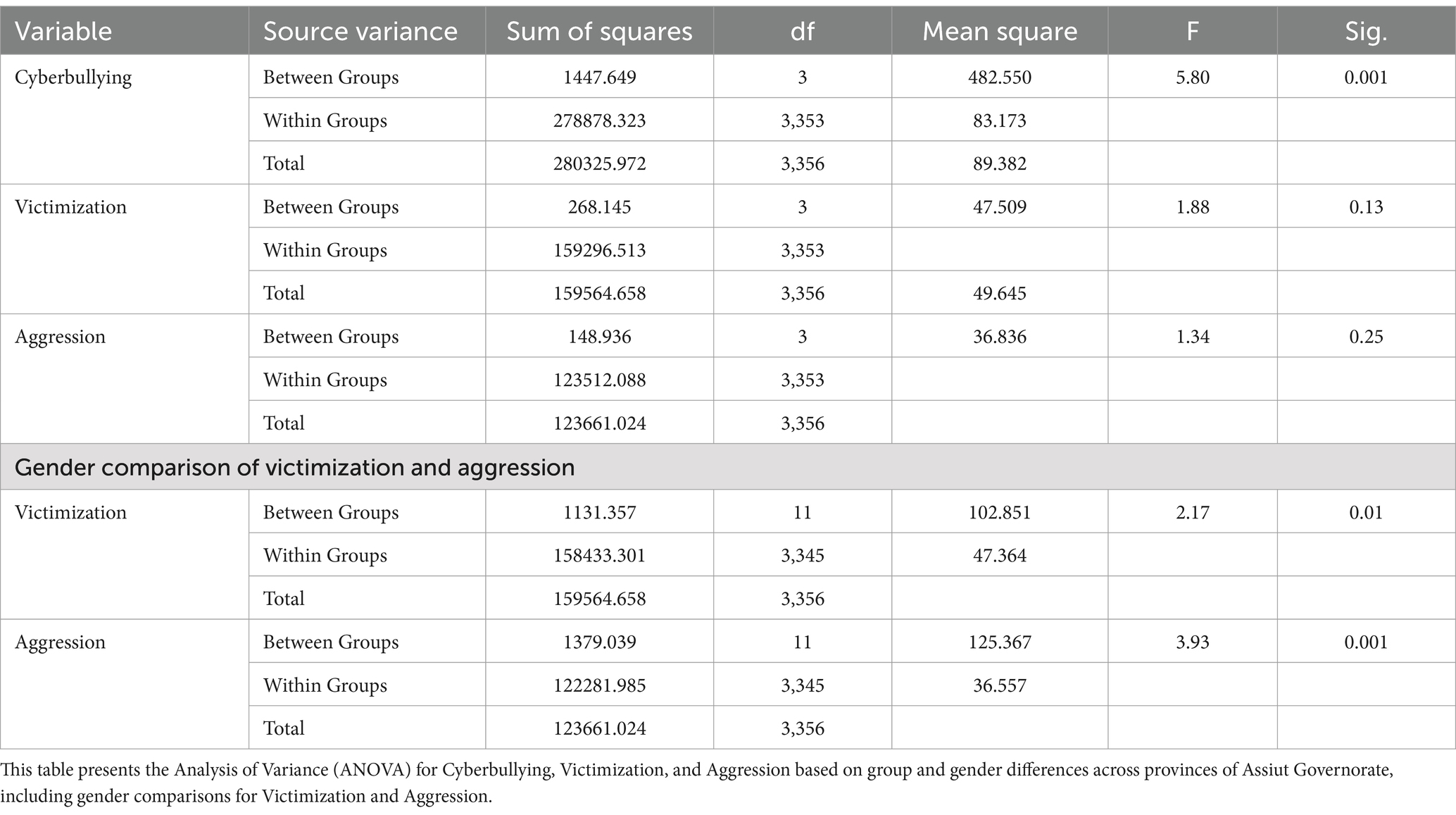

The ANOVA results indicate significant differences in cyberbullying levels across different groups (F = 5.80, p = 0.001), suggesting that certain demographic factors, such as age and gender, influence cyberbullying prevalence. However, victimization (F = 1.88, p = 0.13) and aggression (F = 1.34, p = 0.25) did not show statistically significant differences, implying that these behaviors are more evenly distributed across different demographic subgroups.

The post-hoc analysis using Least Significant Difference (LSD) tests revealed that adolescents aged 18–19 years reported significantly higher cyberbullying exposure compared to both the 16–17 years and 20–21 years age groups (p < 0.05). This suggests that older adolescents may be at increased risk of cyberbullying due to greater online engagement.

The correlation analysis further supports these findings. Cyberbullying was positively correlated with marital status (r = 0.073, p < 0.01) and professional status (r = 0.086, p < 0.01), indicating that individuals with higher social exposure are more likely to be targeted for cyber harassment.

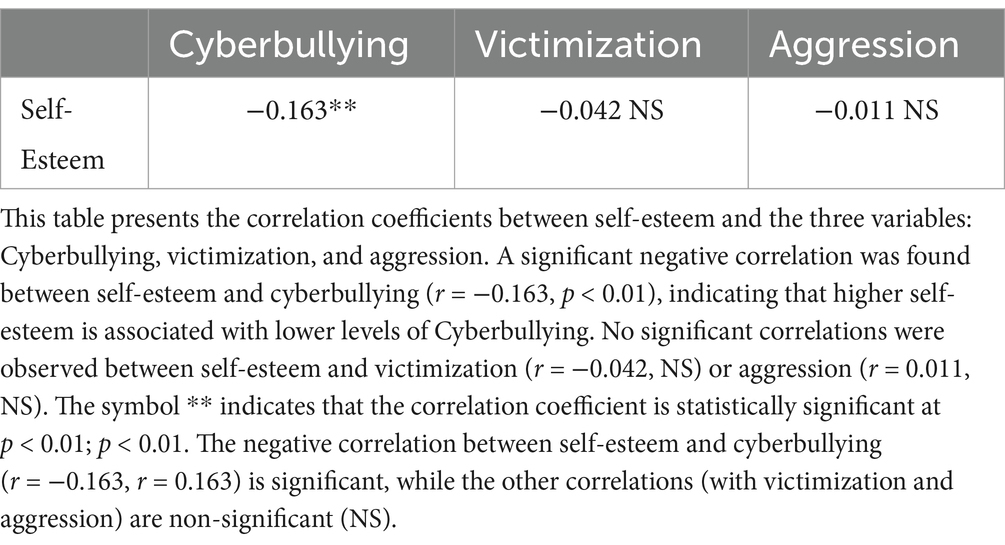

Interestingly, self-esteem showed a significant negative correlation with cyberbullying (r = −0.163, p < 0.01), reinforcing its protective role against online aggression. However, no significant relationship was found between self-esteem and victimization (r = −0.042, NS) or aggression (r = −0.011, NS), suggesting that other psychological factors may influence these experiences.

Table 4 indicates significant differences among the Governorate’s Marakiz on the Bullying Victimization Scale, as the F-value was statistically significant at the 0.01 level. Similarly, significant differences were observed among the districts on the Aggression Scale, with the F-value reaching statistical significance at the 0.001 level. To determine the direction of these differences across districts concerning bullying victimization and aggression, a Post-hoc analysis was conducted using the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test (Table 5). For detailed results, refer to Appendix A Table 6.

Table 4. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for cyberbullying, victimization, and aggression based on group and gender differences across provinces of Assiut Governorate.

Table 5. Correlation coefficients between self-esteem and cyberbullying, victimization, and aggression.

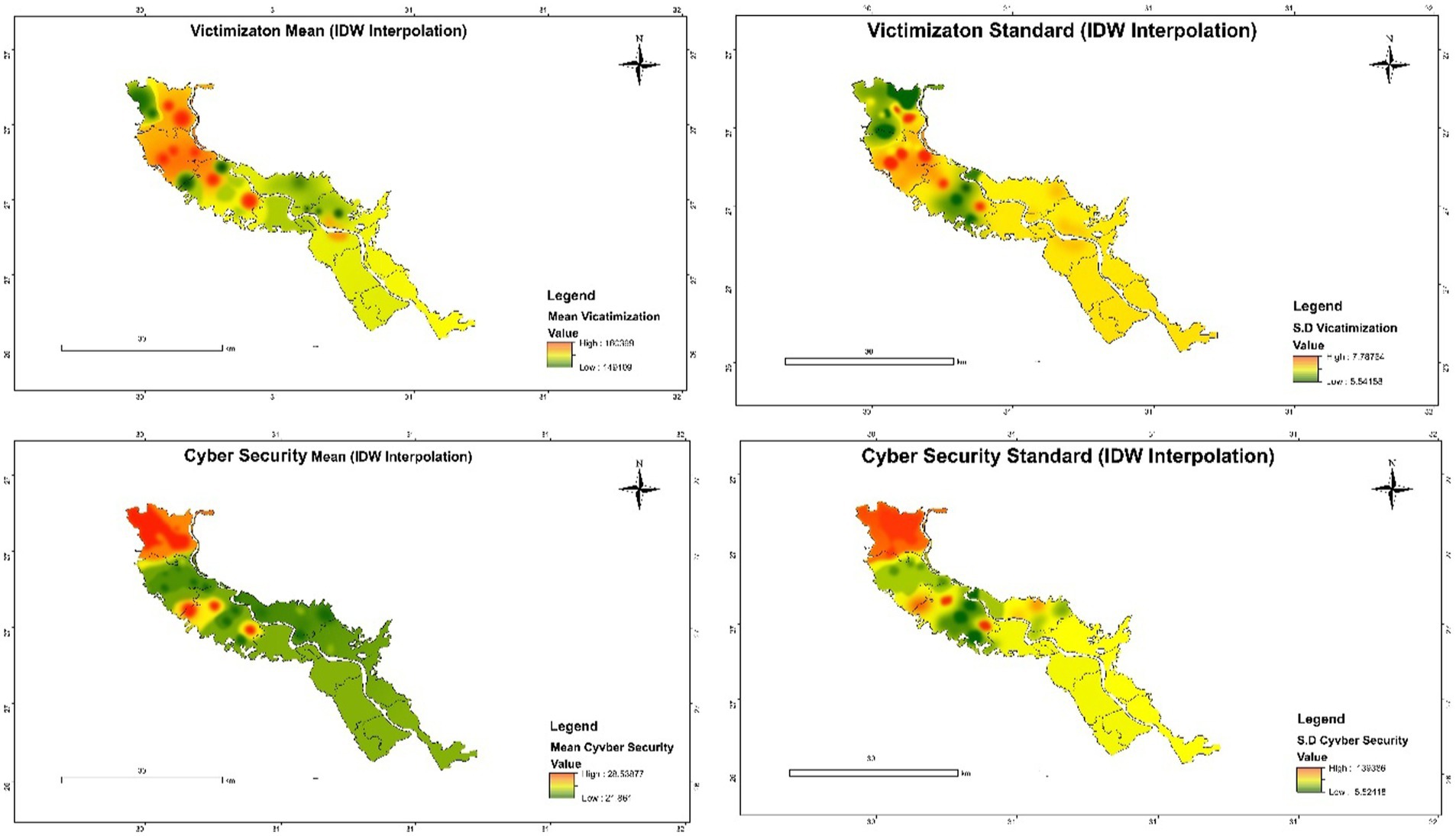

Geographical distributions of cyberbullying across the governorate

There is evidence that Assiut City tends to show higher levels of self-esteem compared to other Marakiz, which can be attributed to several social and cultural factors. Studies suggest that individuals in larger urban areas like Assiut have greater access to positive social interactions, educational resources, and mental health support. These factors collectively contribute to higher self-esteem (Sayed et al., 2020).

In particular, urban environments such as Assiut City often offer more opportunities for socialization, personal achievement, and educational advancement, all of which play key roles in enhancing self-worth. The availability of psychological and social support networks in cities provides individuals with the necessary tools to build a positive self-image, as noted by Mustafa and his colleagues in their 2020 study on self-esteem among university students (Sayed et al., 2020).

There is substantial evidence indicating a clear relationship between lower levels of cyberbullying and higher self-esteem, as demonstrated by various psychological studies. Generally, individuals with higher self-esteem are less likely to become victims of cyberbullying, while those with lower self-esteem are more vulnerable. According to Patchin and Hinduja (2010), victims of cyberbullying often report lower self-esteem, as the experience can lead to feelings of worthlessness. However, individuals with higher self-esteem tend to be more resilient and better equipped to handle online harassment. This may explain why regions like Assiut City, which have lower rates of cyberbullying, also report higher self-esteem levels among residents.

Research by Garaigordobil (2011) further underscores the buffering effect of self-esteem against the psychological harm caused by cyberbullying. Individuals with high self-esteem are less likely to internalize the negative impacts of online bullying, making them less frequent targets. In contrast, findings from areas like Sedfa reveal higher levels of cyberbullying and lower self-esteem, supporting the notion that vulnerability to cyberbullying increases with low self-esteem (Ortega et al., 2012). Therefore, promoting self-esteem may serve as an effective strategy for reducing the prevalence of cyberbullying.

Moreover, cultural norms in cities like Assiut often place a higher emphasis on individual success and social participation, leading to more frequent validation and encouragement, which are critical for maintaining a high sense of self-esteem (Psychology Doc, 2021; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Spatial distribution of cyber security and victimization (IDW interpolation). This figure illustrates the spatial distribution of key variables across Assiut Governorate using Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) interpolation. The first map (left) shows the standard deviation of cyber security values, highlighting variability across the region. The second map (center) represents the mean victimization scores, with higher values concentrated in the northern regions. The third map (right) displays the standard deviation of victimization scores, identifying areas with greater dispersion in victimization experiences. These maps provide insights into the spatial dynamics of cyber security and victimization across the studied region.

According to Appendix B Table 7, Markaz Dayrout displayed statistically significant differences in bullying victimization compared to Markaz Sahel Seleem, Markaz Alquseyah, and Markaz El-Ghanayem, with positive mean differences favoring Markaz Dayrout. Similarly, Markaz Assiut showed significant differences compared to Markaz Sahel Seleem and Markaz El-Ghanayem, favoring Markaz Assiut. Markaz Abu Tig revealed significant differences compared to Markaz Sahel Seleem and Markaz El-Ghanayem, indicating higher mean values for Markaz Abu Tig. Markaz Sedfa exhibited significant differences across various Marakiz, including Markaz Abnoub, Markaz El-Fath, Markaz Sahel Seleem, Markaz Alquseyah, Markaz El Badary, Markaz El-Ghanayem, Markaz Assiut City, Markaz Manfalout, and Markaz Abu Tig. All differences were statistically significant (p < 0.05, 0.01), highlighting Sedfa as the Markaz with the highest frequency of bullying victimization among both males and females.

There is no statistically significant positive relationship between high self-esteem and either bullying victimization or aggression. The correlation coefficient between high self-esteem and cyberbullying was −0.163, which is statistically significant at the 0.01 level. Interestingly, both groups of bullying victims exhibited high self-esteem, with correlation coefficients of −0.163 and 0.01, respectively.

Descriptive statistics for key variables across provinces are provided in Appendix B Table 8. Markaz Sedfa ranked first with an average score of 28.54 and a standard deviation of 3.94. Markaz Dayrout followed in second place with an arithmetic mean of 27.62 and a standard deviation of 3.18. Markaz Sahel Seleem came in third with a mean score of 26.06 and a standard deviation of 3.74. In fourth place, Markaz Manfalout recorded a mean score of 26.00. The fifth position for cyberbullying was reported as “middle of the pack,” with a mean score of 26.23 and a standard deviation of 1.20. This data also highlights variables such as cyberbullying, victimization, aggression, and self-esteem, with their respective means and standard deviations. Rankings were determined based on these measures.

Discussion

Despite cyberbullying becoming a major concern, the primary challenge lies in implementing preventive measures because internet access cannot be restricted due to its numerous benefits. The current research aims to examine the impact of age, gender, marital status, profession, and self-esteem on cyberbullying. Previous studies have shown that cyberbullying is most prevalent among adolescents aged 12 to 18. In this study, it was found that adolescents between the ages of 16 and 21 experience cyberbullying both as victims and perpetrators, with the highest prevalence occurring in the 18–19 age group. However, past studies (Pichel et al., 2021a,b) have indicated that younger adolescents are more vulnerable as victims, while older adolescents are more likely to act as perpetrators. Thus, while the current study supports Hypothesis 1 (H1), previous findings also align with these results.

Although the present study provides valuable insights into cyberbullying among adolescents in Assiut Governorate, it did not incorporate assessments of psychological and social factors such as mental health vulnerabilities or digital hygiene levels, which could influence cyberbullying behaviors. This limitation should be considered when interpreting the findings, highlighting the necessity for future research to include these variables to ensure a more comprehensive analysis of the contributing factors to cyberbullying prevalence.

Recent research on cyberbullying suggests that adolescents can be grouped into distinct clusters based on their experiences and responses to online aggression. For example, studies have identified subgroups such as passive victims, retaliatory victims, and resilient adolescents who effectively counter cyberbullying (Smith and Jones, 2023). Understanding these clusters can help tailor interventions that address the specific needs of each group. Future research should explore whether such classification patterns are applicable to adolescents in Egypt and how cultural factors influence these groupings.

Household composition is another significant factor influencing bullying behavior in children. This study revealed a positive correlation between marital status and cyberbullying, suggesting that married individuals are more susceptible to cyberbullying. This may be attributed to the fact that cyberbullies are often unknown to their victims, leading to heightened concerns about family safety. Professional status was also found to have a positive relationship with cyberbullying, indicating that individuals with higher professional status are more likely to experience cyberbullying compared to those without such status. Consequently, the current study does not support Hypothesis 2 (H2), as it can be assumed that individuals who are conscious of their professional image are more prone to cyberbullying due to their visibility on social media platforms.

Similar to traditional bullying in schools, cyberbullying affects males and females differently. This study revealed that both genders were equally victimized by bullying, suggesting that indirect violence like cyberbullying is not influenced by gender. This supports Hypothesis 3 (H3), which posits that victimization is not gender-based, as indirect violence tends to have a tormenting effect on children regardless of gender. Therefore, this study does not identify gender as a predictive factor for cyberbullying. However, prior research presents mixed findings. While some studies (Balakrishnan, 2015; Beckman et al., 2013) suggest that female social media users are more likely to engage in cyberbullying, others (Wang et al., 2009; Li, 2017) indicate that male users are more inclined toward such activities.

Digital literacy serves as a critical protective factor against cyberbullying. Adolescents with higher digital literacy skills are more likely to recognize online risks, employ protective measures, and engage in responsible digital behavior (Aizenkot and Kashy-Rosenbaum, 2021). In contrast, those with limited digital literacy may struggle to identify cyberbullying situations and respond effectively. Incorporating digital literacy education into school curricula and awareness campaigns can significantly reduce cyber victimization rates. Future research should investigate the effectiveness of such interventions in mitigating cyberbullying among adolescents in Egypt.

The role of family environment in cyberbullying experiences is well-documented. Parental monitoring and open communication between parents and adolescents have been linked to lower cyberbullying victimization rates (Bussu et al., 2024). Conversely, family conflicts, lack of supervision, or excessive digital restrictions may increase vulnerability to online aggression. Understanding the balance between digital supervision and adolescent autonomy is crucial in developing family-based prevention programs. Future research should examine how different parenting styles influence adolescents’ online behaviors in the Egyptian context.

Furthermore, appearance-related cyberbullying has been associated with an increased desire among adolescent females to alter their physical appearance, negatively affecting their self-esteem and psychological wellbeing (Prince et al., 2024). These findings highlight the need for targeted interventions addressing self-image issues in affected adolescents.

The results of this study align with previous research highlighting the complex relationship between cyberbullying and demographic factors. Consistent with Patchin and Hinduja (2010), this study found a negative correlation between self-esteem and cyberbullying, reinforcing the idea that individuals with higher self-worth are less likely to be cyberbullied. However, contrary to previous findings by Pichel et al. (2021a,b), which suggested that younger adolescents (12–15 years) are more susceptible to cyber victimization, this study found that older adolescents (18–19 years) reported the highest rates of cyberbullying. This discrepancy may be due to increased internet exposure and digital engagement among older teens in Egypt compared to younger adolescents who may have more parental supervision.

In contrast to studies by Wang et al. (2009) and Li (2017), which indicated that males are more likely to engage in cyberbullying behaviors, our study did not find significant gender-based differences in cyberbullying victimization. This suggests that in certain cultural contexts, such as Assiut Governorate, both males and females may be equally vulnerable to cyber harassment due to traditional societal norms restricting public discussions of victimization.

Another interesting contrast with the literature is related to the role of professional and marital status in cyberbullying exposure. Prior research (Smith A. et al., 2022) suggested that higher professional status individuals are less likely to be cyberbullied, as they may have better social support mechanisms. However, this study found a positive correlation between professional status and cyberbullying (r = 0.086, p < 0.01), indicating that individuals with greater social visibility face increased risks of online harassment. One possible explanation is that professionals and married individuals are more active on social media for networking purposes, making them more exposed to potential online threats.

These findings highlight the importance of digital literacy and psychological resilience programs tailored to different demographic groups. While self-esteem-building interventions could help reduce cyberbullying rates, future research should investigate how cultural and contextual factors moderate the relationship between demographic characteristics and cyberbullying behaviors.

Another common predictive factor identified is self-esteem among young people. Numerous researchers have established a relationship between low self-esteem and bullying behavior in adolescents. This study suggests a negative relationship between high self-esteem and cyberbullying, thus confirming Hypothesis H4. This finding aligns with prior research by Patchin and Hinduja (2010) and Ostrowsky (2010), which indicates that low self-esteem leads to higher tendencies of cyberbullying. Additionally, these authors have established a connection between self-esteem and victimization. However, the present study found no statistically significant positive relationship between high self-esteem and either bullying victims or aggression, thus failing to support the victim aspect of H4.

The size of victims of harassment and coercive behavior does not significantly vary by age. Post-hoc tests, conducted alongside Least Significant Difference (LSD) tests, identified significant differences between older groups regarding cyberbullying. This is because, in instances where p-values are not statistically significant, the value of P may still be significant at a practical level of importance. There is also evidence of a link between marital and professional status and cyberbullying.

To further explore age ranges of young people vulnerable to cyberbullying and aggression, it was observed that age distinctions did not significantly affect the size of bullying victims or aggressiveness. However, differences in victimization were statistically significant across several Marakiz. Specifically, Abu Tig, Sahel Seleem, and El-Ghanayem exhibited considerable differences in the number of bullying victims, while Markaz of Assiut, Sahel Seleem, and El-Ghanayem also showed notable differences in aggression. Positive mean differences were observed between Markaz of Sahel Seleem, Alquseyah, and El-Ghanayem, indicating statistical significance in these variations. Similarly, Markaz of Sedfa, Abnoub, and Al-Fath demonstrated statistically significant differences.

The findings of this study can be interpreted through the lens of General Strain Theory (GST; Agnew, 1992), which suggests that individuals experience psychological strain due to negative life events, leading them to engage in coping mechanisms that may include aggression or victimization. In the context of cyberbullying, exposure to online harassment can serve as a significant strain, particularly for adolescents with lower self-esteem. This aligns with the study’s findings, which indicate that self-esteem is negatively correlated with cyberbullying experiences (r = −0.163, p < 0.01). Adolescents with lower self-esteem may be more vulnerable to cyber harassment due to reduced emotional resilience and weaker social coping mechanisms. Furthermore, consistent with GST, the study found that older adolescents (18–19 years) reported higher cyberbullying exposure than younger adolescents (16–17 years, p < 0.05). This could be attributed to their greater digital engagement, higher social expectations, and exposure to online stressors, which contribute to the strain-induced risk of cyber victimization. Future research should explore how psychosocial support mechanisms can mitigate these stressors and strengthen adolescents’ ability to cope with online aggression.

The findings further indicate that experiences of violence, cyberbullying, and online bullying can negatively impact self-esteem. This study supports the conclusion that cyberbullying has a negative correlation with high self-esteem, as evidenced by the analysis of factors contributing to confidence.

While previous studies (e.g., Pichel et al., 2021a,b) have suggested that younger adolescents (12–15 years) are more vulnerable to cyber victimization, our findings indicate that older adolescents (18–19 years) are at higher risk. This contradiction may be influenced by shifting digital behaviors, where older teenagers engage in higher-risk online activities, such as public social media engagement, digital networking, and exposure to online conflicts (Wang et al., 2009). Additionally, the socio-cultural dynamics in Assiut Governorate may shape cyberbullying experiences differently than in Western contexts. Parental monitoring tends to be stricter for younger adolescents, limiting their unsupervised online activity, while older adolescents gain more autonomy, increasing exposure to cyber risks.

Similarly, the lack of significant gender differences in cyber victimization contradicts several studies (e.g., Li, 2017) that found males are more likely to engage in cyber aggression. This may be explained by cultural norms in Assiut, where both males and females may experience cyber harassment but report it differently. In conservative societies, female cyberbullying victims may avoid disclosing their experiences due to social stigma, whereas male victims may underreport cyber harassment to avoid perceptions of weakness. These cultural factors suggest the need for context-sensitive cyberbullying prevention programs that account for gendered reporting biases and digital literacy gaps.

A key limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which does not allow for causal inferences. While significant associations were identified between cyberbullying, demographic factors, and self-esteem, these relationships should not be interpreted as direct causal effects. Future research should employ longitudinal designs to track changes over time and establish clearer causal relationships between cyberbullying behaviors and psychological or sociodemographic factors.

Policy implications and recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, several targeted policy recommendations can be made to address cyberbullying among adolescents in Assiut Governorate:

1. Strengthening digital literacy programs

• Schools should implement cyber safety education focusing on identifyingcyberbullying, reporting mechanisms, and digital self-protection strategies.

• Incorporate cyber ethics and online behavior awareness in the national education curriculum.

2. Gender-Sensitive Support Systems

• Establish anonymous cyberbullying reporting platforms that address gendered reporting biases in conservative communities.

• Develop safe spaces for female victims to seek psychological and legal support without stigma.

3. Parental and Community Engagement

• Launch awareness campaigns for parents on monitoring adolescents’ online activities while respecting privacy.

• Promote family-based interventions that encourage open discussions on cyber risks and coping strategies.

4. Integrating Cyberbullying Prevention in Mental Health Services

• Train school counselors and psychologists to identify and intervene in cyberbullying cases early.

• Offer self-esteem and resilience-building workshops for high-risk adolescents.

5. Policy and Law Enforcement Strengthening

• Enforce cyberbullying laws by ensuring legal protection for victims and penalties for perpetrators.

• Improve collaboration between schools, law enforcement, and social media platforms to monitor and control online harassment.

• Peer-Led Cyberbullying Prevention Programs:

Research has shown that peer-led intervention programs can be an effective approach to cyberbullying prevention (Sahabat, 2023). Schools can implement structured peer mentoring programs where trained students help their peers recognize and report cyberbullying incidents. This approach fosters a supportive school culture and encourages victims to seek help without fear of stigma.

• Additionally, incorporating cyber safety awareness sessions into the national school curriculum can improve adolescents’ digital resilience and equip them with the skills needed to navigate online risks safely (Sahabat, 2023). These programs should be tailored to cultural and regional contexts, ensuring that they address the specific challenges faced by students in Assiut Governorate.

Conclusion

This study offers critical insights into the growing issue of cyberbullying among adolescents, with a specific focus on Assiut Governorate, Egypt. The results indicate that adolescents aged 18–19 are the most vulnerable group, revealing significant correlations between cyberbullying and demographic factors such as marital and professional status. These findings emphasize the need to address the broader social and psychological contexts that contribute to cyberbullying.

The study highlights the protective role of self-esteem, suggesting its potential as a focal point for intervention strategies. However, the lack of a significant relationship between self-esteem and victimization implies that additional factors may influence how individuals experience and respond to cyberbullying.

Given the psychological and social consequences of cyberbullying, a multi-stakeholder approach is essential. Schools should integrate digital literacy and anti-bullying programs into their curricula to equip students with the skills needed to navigate online spaces safely. Parents must foster open communication with their children and actively monitor their online activities to prevent and address incidents of cyberbullying effectively. Policymakers should develop regulations aimed at promoting safer online environments and ensuring accountability for perpetrators.

Future research should investigate the interplay between cultural, economic, and psychological variables that exacerbate cyberbullying across different contexts. Longitudinal studies could provide valuable insights into the long-term effects of cyberbullying on adolescents’ mental health, academic performance, and social relationships. Furthermore, interventions targeting at-risk groups, such as those with low self-esteem or high social visibility, should be developed and evaluated for effectiveness. Encouraging physical activity among adolescents has been identified as a protective strategy against both cyberbullying and victimization. Systematic reviews suggest that integrating physical activity during and after school hours can significantly reduce risks associated with bullying behaviors (Rusillo-Magdaleno et al., 2024). Such initiatives could be adapted to the Egyptian context, leveraging the roles of schools and community centers in fostering inclusive and supportive environments.

To better understand the causal mechanisms underlying cyberbullying behaviors, future research should consider employing longitudinal or experimental study designs. These approaches would allow for a more precise examination of temporal changes and potential causal pathways between cyberbullying, digital behaviors, and psychological wellbeing. Given the increasing complexity of the digital environment, future research should explore the impact of digital hygiene levels and mental health vulnerabilities as confounding factors in the dynamics of cyberbullying. Advanced statistical models, such as multiple regression analysis or structural equation modeling (SEM), could help assess the extent to which these factors influence both victims and perpetrators across different cultural contexts.

Moreover, AI-driven detection tools have gained traction as a promising avenue for mitigating cyberbullying incidents. These tools utilize machine learning algorithms to analyze online interactions, detect harmful content, and provide early warning signals for potential cyberbullying cases. Future research should assess the effectiveness of AI-based interventions in real-time monitoring and response strategies, ensuring a safer digital environment for adolescents.